Major Stabb’s hunting trip in 1875 to the Zambesi Valley via Gubulawayo

Introduction

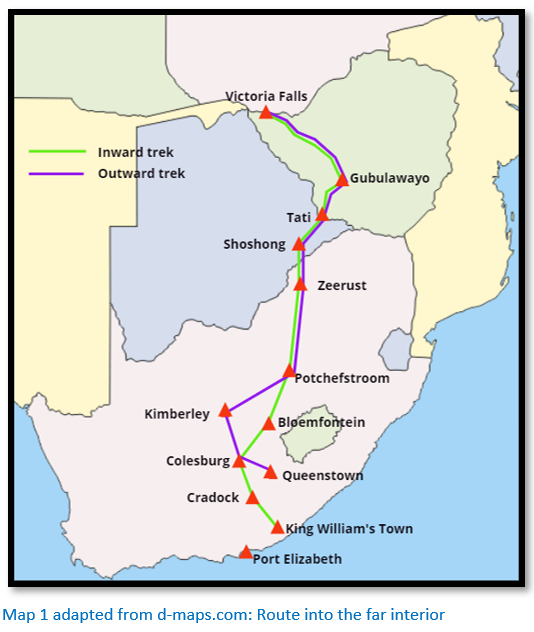

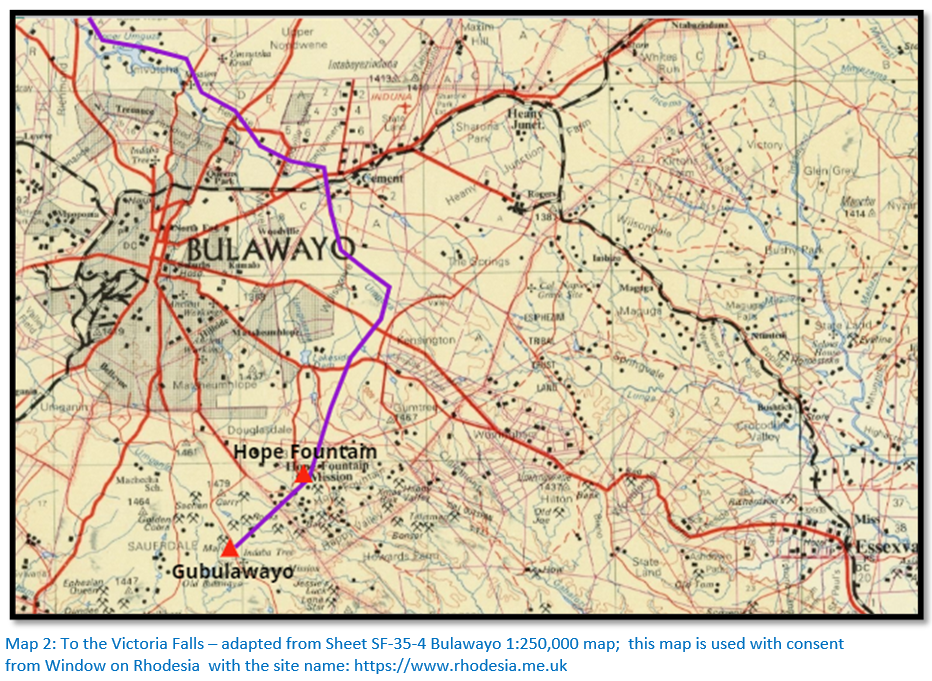

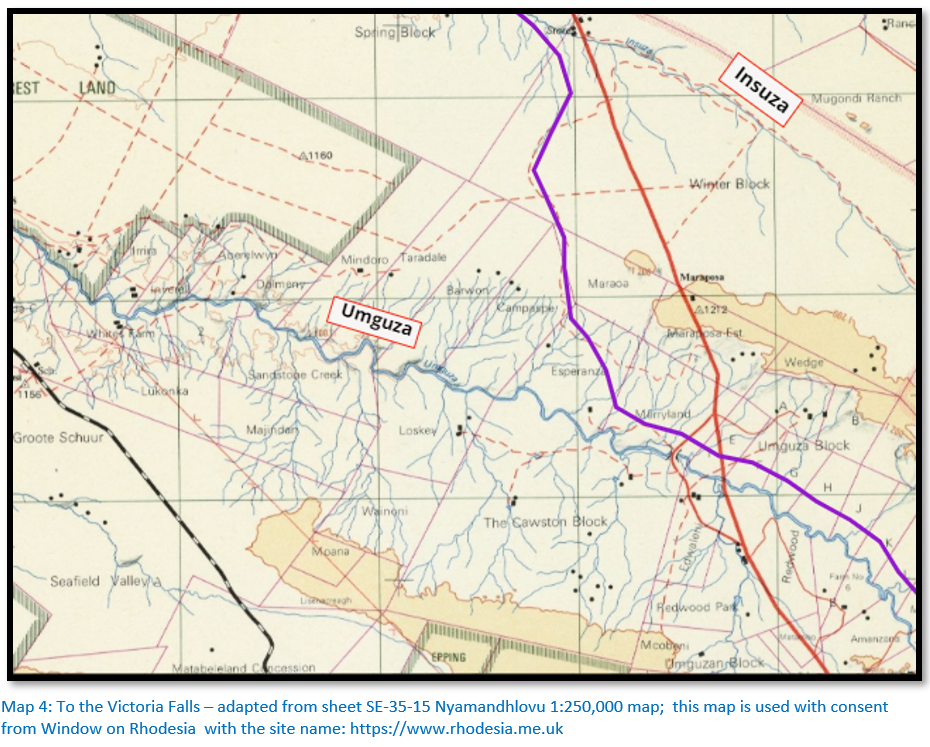

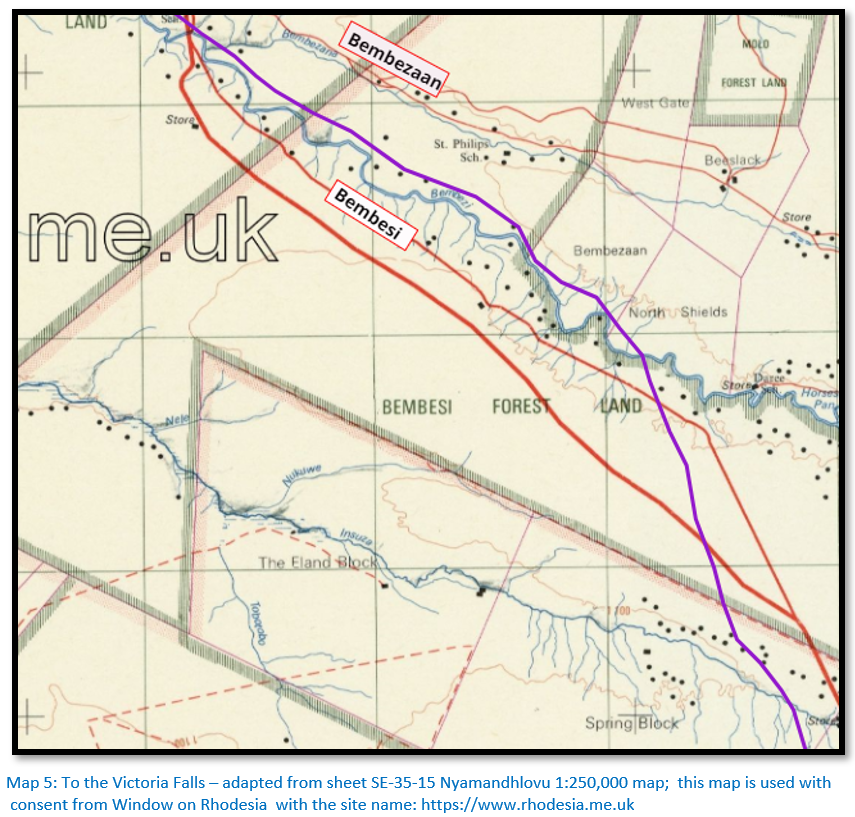

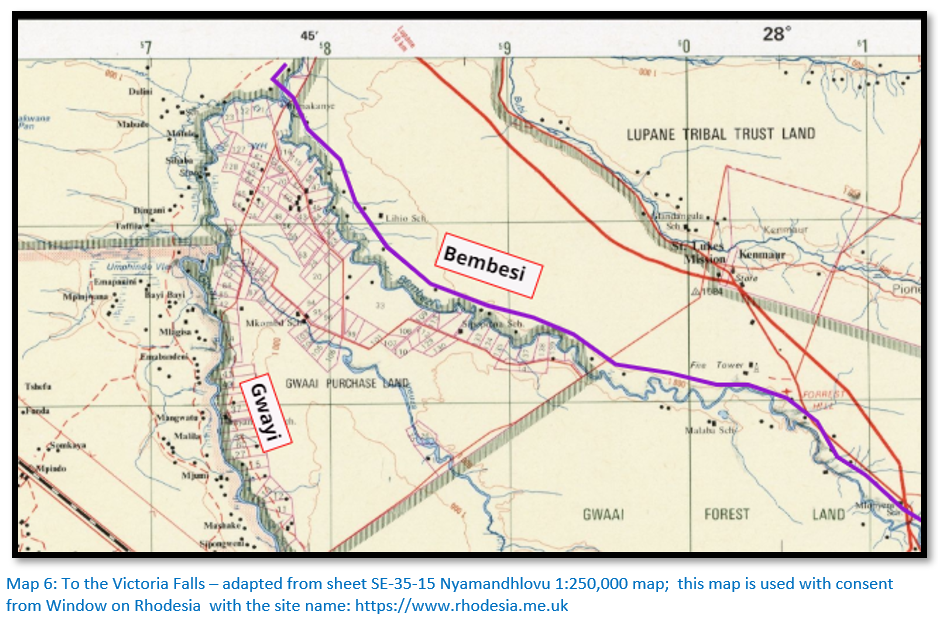

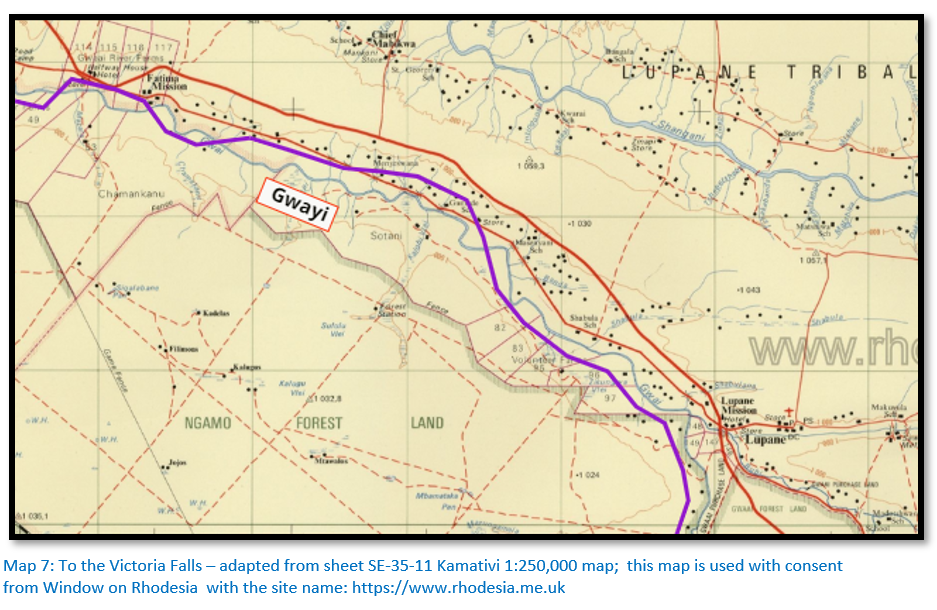

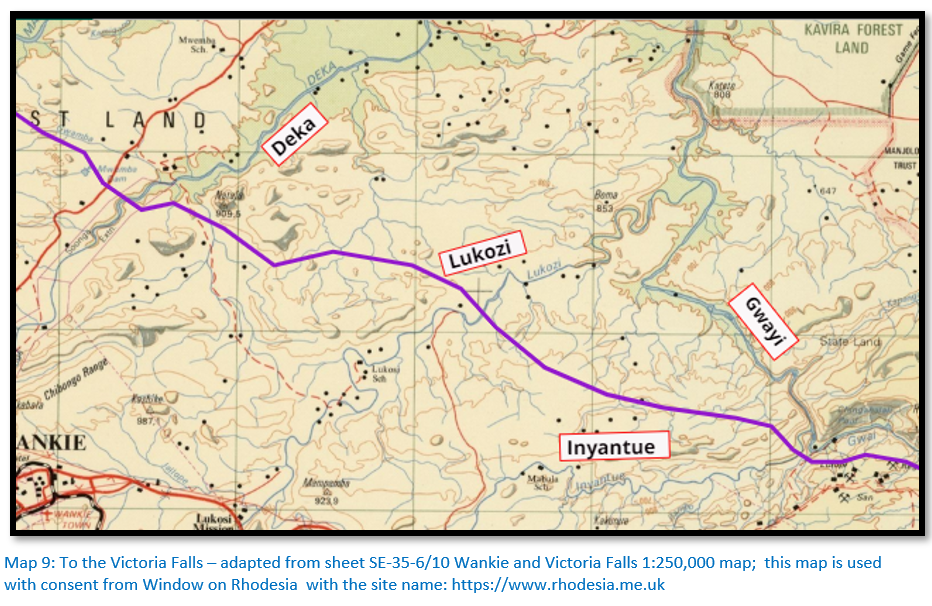

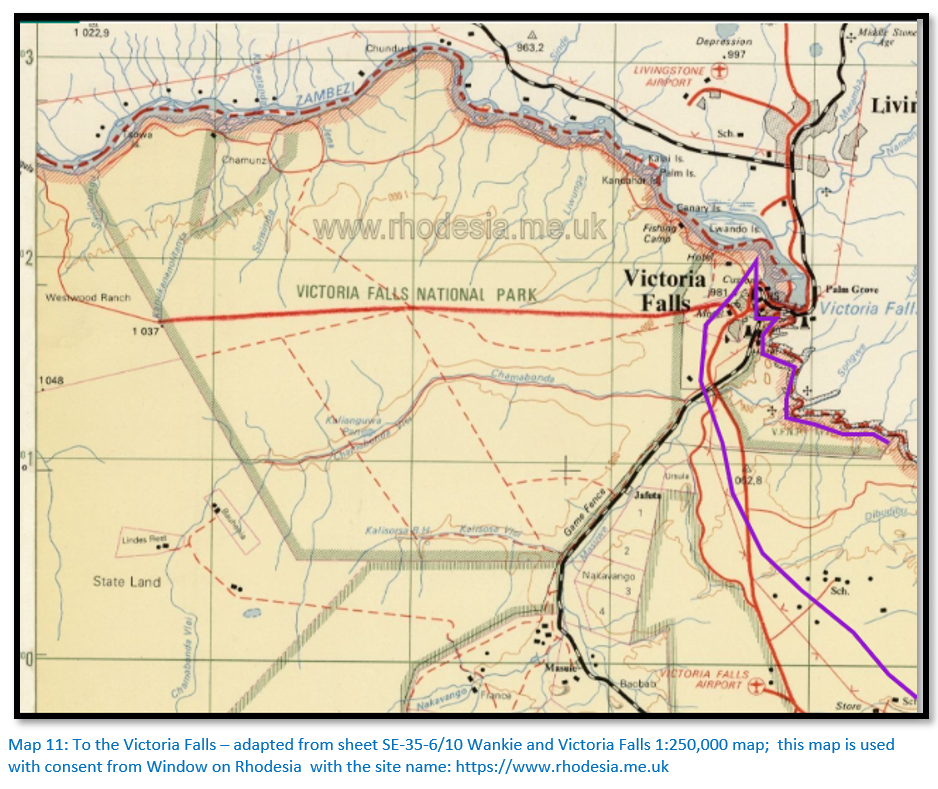

Henry Stabb’s meticulously kept diary provides a wealth of information on the events of the trip to Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls. Their route from Gubulawayo to the Falls via the Umguza, Insuza, Bembesi river valleys to the Gwayi river was in contrast to most travellers who took the Westbeech road from Tati to Pandamatenga and then walked to the Falls. Stabb was the first European I believe to take this route and amongst the first fifty European visitors to the Falls. [See the article The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] His diary records the daily travel experiences of trekking, their luck at hunting, the kraals and places they passed through and the people they met. His observations of Lobengula, the amaNdebele, the missionaries and traders and the San Khoisan people all have a useful historical importance.

They left King William’s Town on 27 March 1875 and arrived at Gubulawayo on 19 July. Walking from Gubulawayo to the Victoria Falls took 21 days (18 August – 7 September) and the return journey took 18 days (9 September – 26 September) Stabb was back in Queenstown with his regiment by 22 December 1875.

The diary is written on twenty numbered folios of differing sizes and is 490 pages long with some of the pages relating to drinking and to the faults and habits of people he met marked ‘Leave out,’ so presumably he thought of publishing at some time. Diary extracts are in Italics.

Early journey to Shoshong

Major Charles Henry Sparke Stabb took a sabbatical from his regiment based at King William’s Town in British Kaffraria to go hunting and exploring in the far interior. He left with a fellow officer, Captain James Jocelyn Glascott on 27 March 1875 in an ox-wagon drawn by twelve oxen in the charge of a wagon driver named Scheeper[i] and voorloper named McLean with Wood and Harrison, two soldier-servants of the 32nd (Duke of Cornwall’s) Light Infantry.

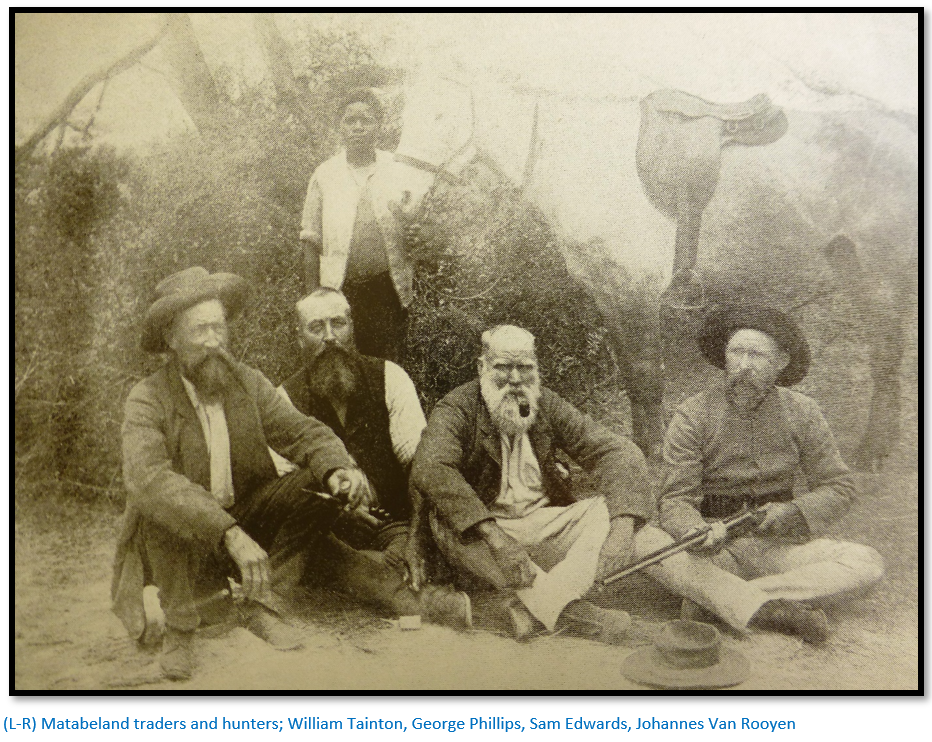

They trekked via Aliwal North and Bloemfontein (where they met President Brand) and to Potchefstroom by 10 May where they attended the wedding of the daughter of Forssman, a Swedish trader and Stabb received notice of his promotion to Major. Scheeper quit his job and McLean replaced him, although Glascott had learned to drive the waggon and helped out. They were at Zeerust on 24 May. Here they met up with George Westbeech, Dr Benjamin Bradshaw, George Phillips and James Fairbairn and were present at Westbeech’s wedding to Cornelia Kroning as they made final preparations to continue the journey.

25 May: “Zeerust is a queer little place…It is one of the most primitive places in the world, but as the frontier town in the Transvaal we see here the last traces of the civilisation we leave behind us.” Their guns (all breech-loaders) comprised: “1 No. 8 single-barrel rifle by Holland, 2 express single-barrels carrying 5 drams powder by Holland, 1 No. 12 double-barrel rifle by Rigby, 1 No. 10 smoothbore, 2 Snider rifles for our servants. And our own two shotguns, besides 6 muzzle-loading rifles for stilling purposes[ii] and also to trade.”

1 June: “Hurrah! Westbeech’s happiness to be completed today!...We had by this time cultivated our companions acquaintances a good deal and found them all genial and really good fellows, gentlemen by birth and education, bon vivants by nature and Bohemians from circumstances…The conclusion of the [Wedding] ceremony was announced by another salvo from the guns of Westbeech’s friends, not to be behind with whom we answered with a royal salute from our outspan, the effect of which was rather spoiled by some of the muzzle-loaders refusing to go off.”

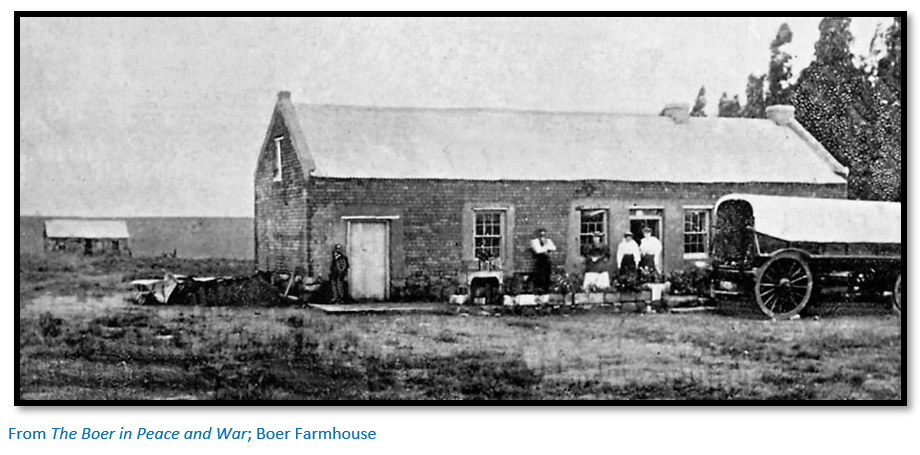

“Breakfast which was prepared by Old John,[iii] a French cook formerly in the P. & O. service whom Westbeech was taking upcountry with him, was of the most substantial and abundant style and laid in the waggon-house, but before it commenced brandy and soda water and bottled beer were so freely handed round as to raise the already excited spirits of the guests to the highest state of enjoyment. The house, like all Dutch farmhouses, was small and infinitely inferior to a fourth-rate Devonshire homestead.”

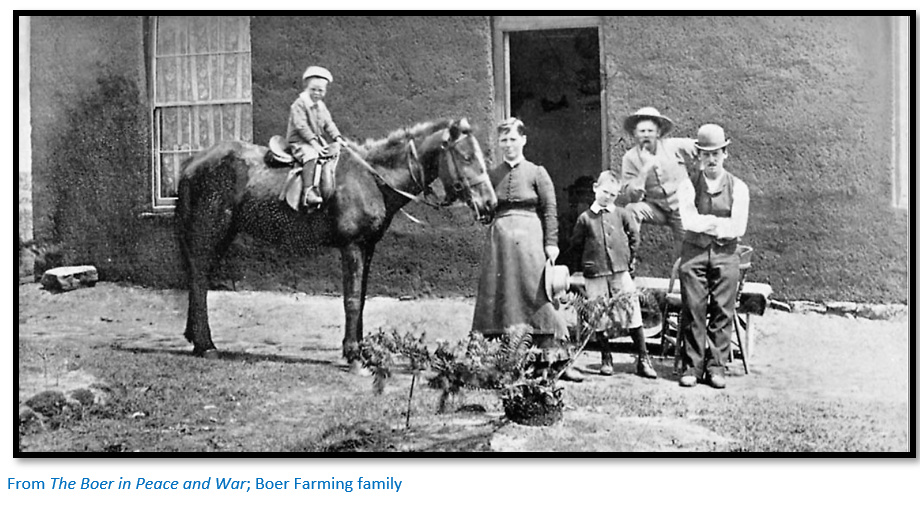

“Luncheon discussed and oceans of fizz consumed, to say nothing of brandy and soda, beer and such like beverages, an attempt at dancing was made, but the only music being a concertina, the only dance a mazurka and the only floor a mud one, it soon degenerated into a romp, the great aim and object of which appeared that each gentleman should kiss as many ladies as he could, to which proceedings I must say, though occasionally after a little playful coyness, the ladies showed not the least objection. Indeed one good old dame of over 50 would insist in the exuberance of her feelings upon embracing me most tenderly, upon which as she was usually in the habit of taking snuff profusely caused me to leave the revels and seek sobriety and consolation in a pipe. Glascott, less lucky however, continued in the merrymaking and attempting to get up a little mild flirtation with a buxom young Boer lady, received just in the way of playful coyness such a backhander from the hands of the fair one as to send him reeling onto his back, to her intense amusement. He declares he never received such a thorough knock-me-down in his life or one delivered with such goodwill; but it was merely in play, kiss and make friends and everything goes as merry as a church bell.”

3 June: The party comprised of Stabb and Glascott, Wood and Harrison, Phillips, White, Fairbairn, John Bushell, Dr Bradshaw,[iv] Old John, Robert Bairn[v] and their native servants left Zeerust travelling through the Dwarsberg where they met Alexander Brown on the Marico River and reached the Wegdraai on 16 June. Stabb and Fairbairn left the others to wait for Westbeech, who had been delayed by his honeymoon and a bout of fever and rode the (sixty miles) to Shoshong which was reached two days later. The remaining party and Westbeech reached Shoshong on 27 June.

Stabb describes George Phillips’ pet goat: “He has a wonderful tame goat, the largest I have ever seen (by name Billy) who always treks in front of the front oxen of his waggon. He is a great favourite, eats out of everybody’s hand, is very fond of tobacco, any quantity of which he will eat, hates milk and other goats and is altogether a character in his way. He has travelled regularly with Phillips for several years and is in remarkable good condition.”

8 June: “Off at daylight and in 1½ hours reached Brackfontein (Mr Fourie’s) the last farm in the Transvaal, where we got a cup of coffee on arrival. Phillips[vi] and Fairbairn[vii] being so well-known on the road, everybody is civil to them…Trekked ‘till 3pm through rather fine country and outspanned for 1 hour after passing through a poort in the Dwarsberg[viii] on the top of a steep stony hill.”

“Judy, Fairbairn’s bull-bitch, took the opportunity immediately after our tent was pitched this evening of being confined of a litter of pups on my bed.”

10 June: at the Marico river they met Alexander Brown[ix] from Tati going to Zeerust who was taking down karosses, ivory, ostrich feathers and a little gold. “Showed us a piece of Tati gold he had, about 5 ounces worth about £4 per ounce. At one time the Tati diggings yielded about 5 ounces to every two tons of quartz; in Australia 4 dwts per ton pays the working. Both Brown and Phillips blamed Sir John Swinburne[x] for the failure of the Tati diggings. He does not seem to have been able to retain the confidence of shareholders nor to get rid of his old man-of-war habits even on shore. They tell rather a good tale of his wanting to enforce discipline on the journey up and making his party take turns in doing beat of sentry-go duty each night with the waggons.”

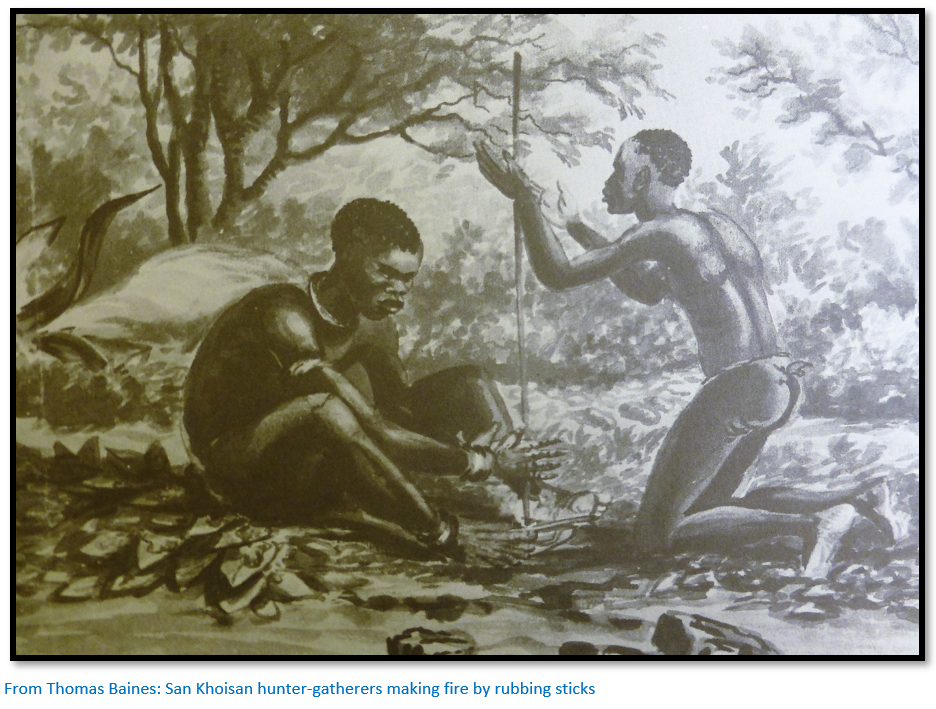

11 June: They leave the Marico for the Crocodile river. “Phillips told us an anecdote of a little Dutch girl (5 years old) who was lost some time ago on the Crocodile for 3 days. She was eventually discovered by some Bushmen [San Khoisan hunter-gatherers] seated on the banks of the river and on being restored to her parents and questioned as to what she had been doing answered that she had met with nothing except some large dogs which had come and smelt her and which on her patting had gone away.” Phillips thought these were probably lions rather than brown spotted hyena.

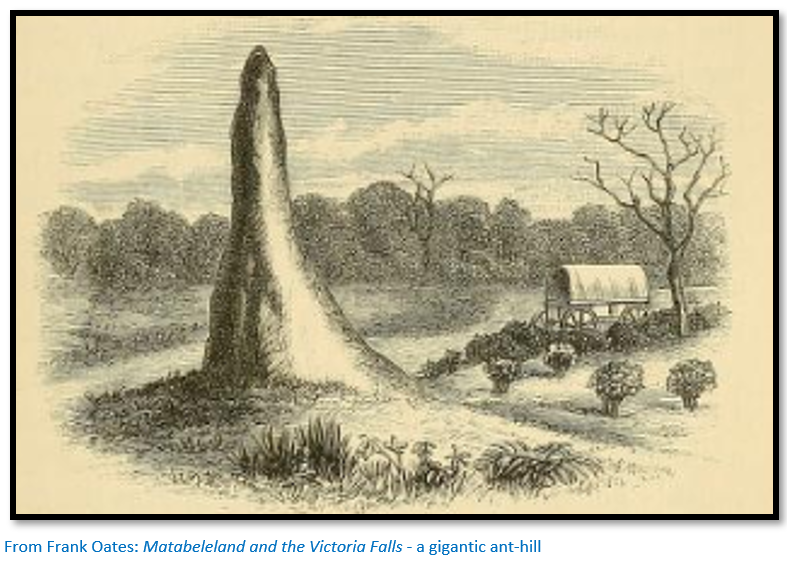

12 June: On the Crocodile river: “Our evening journey was through a shockingly dried-up parched country, full of holes and covered with bush, principally thorns, hack thorns, doublejees, white thorns and waft-jen-betges[xi] which lame your dogs, tear your skin and reduce your clothes to shreds…Passed numbers of huge antheaps, some 20 feet in height with an enormous girth at the bottom but growing up pyramidically; fancy the industry and perseverance of these mites through ages to have constructed such monuments!”

16 June: on the Notwane river: Stabb describes “two most absurd but not less annoying incidents occurred today. Glascott in the morning, being in a hurry to get off, took some flour and made a few scones himself. Whilst the servants attended to the rest of the cooking, which so enraged Wood’s jealous sensitiveness that in the afternoon he came to me saying he was always being interfered with, that he did not want to be humbugged anymore and that he would give up the keys of the boxes and do no more cooking. I shut him up as I best could and he retired growling but not pacified.[xii]

Then later: “whilst riding on our waggon during today’s inspan, Phillips, who is an experienced hand, found some fault with the places our oxen occupied in the yoke and with my consent sent for his driver, Solomon, to suggest a rearrangement. This so hurt the dignity of McLean, our driver (though a very young hand at the work) that he began to blubber and cry and declare that he would leave our service on arrival at Bamangwato [Shoshong]”

17 June: “On the other side of the river [Notwane] we found a regular encampment of 11 waggons with tents and a colony of Doppers who were on the trek to Damaraland;[xiii] 40 waggons had already gone on in front of them, they told us, but as they had heard that they had suffered severely on the lake [Ngami] road from scarcity of water, they had settled here where both water and grass were plenty and intended remaining until the next rains fell…”

The next day Stabb and Fairbairn rode on about sixty miles to Shoshong stopping first at Ogden’s store[xiv] but without dismounting and going on to Francis and Clarke’s store. Shortly after arriving there: “we heard a confused hubbub of voices mixed with the strains of music approaching and immediately in tumbled what I suppose was nearly the whole of the white population of the place headed by Mrs Francis playing on a violin. They had all come to see the new arrivals for the advent of a couple of white men is no insignificant item in the routine of life in this place.”

19 June: “The town [Shoshong] which is the capital of the Bamangwato country and in which we now find ourselves is called in the map Shoshong and to me, being the first of the kind that I have seen, was interesting enough. It is however merely composed of a large collection of huts, apparently at first glance huddled closely together without any regard to arrangement and order and containing a population of perhaps 20,000. The whole town is surrounded by a thick hedge of thorns, erected at considerable labour as a bulwark of defence both against surprises by a hostile tribe and against depredations of wild animals…The situation of the town has been chosen with a view of defence. It is built at the base of a range of hills and runs back up a deep gorge which leads to the only fountain of water known in the neighbourhood.”

A long description of the Bamangwato follows including a history of the people told to him by Fairbairn before they call on the Reverends McKenzie, the senior resident missionary and Hepburn. “Mr McKenzie was full of information and I learned a good deal from him about the country. He acts as postmaster[xv] here.”

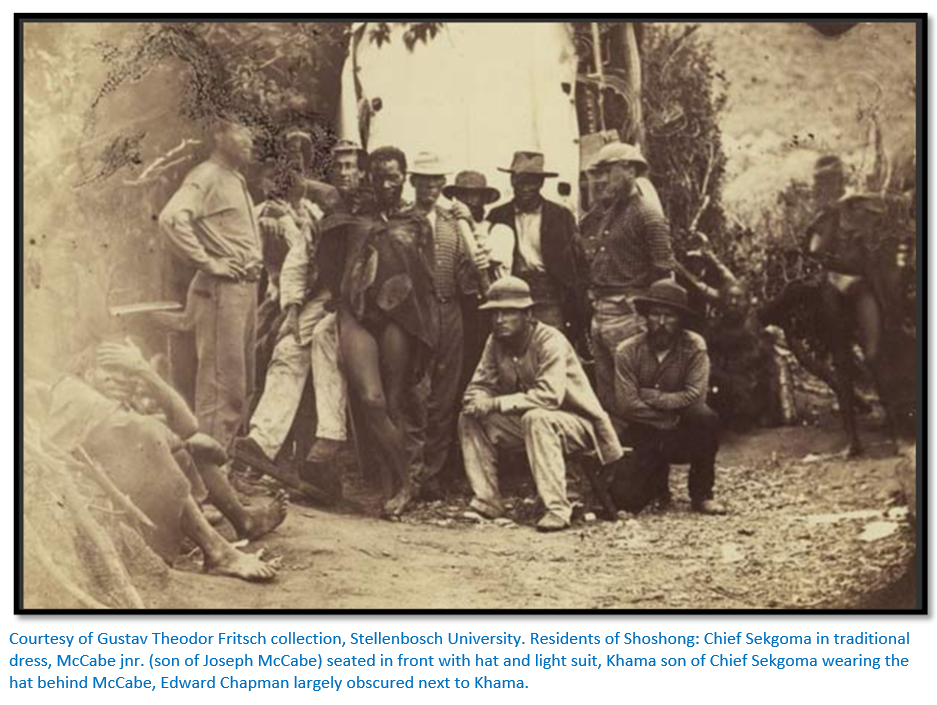

On their return from McKenzie’s they met Chief Khama III at Francis’ store: “he is a particularly intelligent good-looking man, tall and gentlemanly and even courteous in manner, well-dressed entirely in European clothing and of good carriage. He has been educated by McKenzie, is a Christian and a sworn enemy to liquor which he resolutely refuses to admit to his country. We shook hands with him and told him we were coming to pay our respects to him when he said he was very glad to see us and would do anything he could for us whilst in his country.”

22 June: Stabb lists the European residents of Shoshong: “Reverends McKenzie and Hepburn with their wives and children, Mr Francis and his wife and employees Gordon, Musson, Oppenshaw and Walsh. Other traders and storekeepers Messrs. Dawson, Ogden, Fry, McArthur, Bennion, Grey, Korner (a German) Hopkirk and Sprainger, also Inglis a blacksmith and waggon-maker and his wife, Thomas by trade a bricklayer and mason, Howse a watchmaker who now mends guns.”

“…A traders life in a station like this is a very rough and peculiar one. Stores consist for the most part of but one or two rooms according to the size filled with muskets, blankets, lead, beads, skins, clothing, preserved meats and every conceivable thing for barter among the natives or trade with the white people, each store comprising an ironmongery, a grocer’s shop and ready-made clothing establishment rolled into one. A counter for trade and a rough table in the centre with seats of old brandy cases compose their sole furniture, while some blankets and skins in the corner, or if luxurious, a karteel supported on four stones or blocks of wood serve as a bed.”[xvi]

Of society in general Stabb says: “Jack is as good as his master, colour being the sole social [xvii]distinction, so one can fancy that society amongst the traders contains a funny mixture. I have known amongst them a double first-class man from Oxford (Phil Smith) now a market gardener and growing vegetables for the gold diggers; a high wrangler from Cambridge, now drinking himself to death (Baldwin[xviii]) bankrupts from the Cape and others whom the judicial atmosphere of the Old Colony could not agree with (Kish, Lee,[xix] Finaughty[xx]) discharged soldiers and deserters from the army and navy (Walsh, Ogden, Escourt, Meyers) ruined gamesters from the diamond fields (Fairbairn, Horn) gentlemen by birth and education but Bohemians by nature (Fairbairn, Phillips, Westbeech, Brown, French) ne’er-do-wells who do no better here than anywhere else, yet always sanguine and amusing (Rens) drunkards who for months together are obliged to be sober because they are unable to indulge in their favourite vice, yet who never miss an opportunity when liquor is to be had (Korner) and the occasional odd fish known to be a scoundrel and suspected of the worst of crimes (Adshade)”

27 June: the rest of the party with George Westbeech arrived: “Of course a general liquor-up and much gossip followed.” Their servants Wood and Harrison were not getting on well together and five of their dogs had been maimed from their habit of getting into the shade under the waggons and failing to get out of the way when the waggons moved.

28 June: they paid Khama a visit with Westbeech interpreting where they learned that Matabeleland was closed because of the threat of redwater disease being imported with their oxen.[xxi]

The Hunter’s Road

4 July: seventeen Europeans with nine waggons left Shoshong comprising the Westbeech party including Dr Bradshaw, Gosling and Bairn, Phillips, Fairbairn, W.C. Francis and his wife, Alexander Walsh and G. Oppenshaw (Francis’ storekeeper and waggon manager) Stabb, Glascott, Harrison and Wood. “We also have 164 head of cattle, 14 horses, 5 donkeys, about 48 native servants, and dogs more than can be numbered.” Tati was reached ten days later, most of the resident men were away hunting; “but Mrs van Rooyen entertained us and gave us the usual Boer welcome of a cup of coffee on arrival. The coffee appeared very good, but Heavens above had we only known of what it had been made!! Mrs Francis would take none and she afterwards told us why and explained that she had not had the opportunity of warning any beforehand, but on arrival she had observed our hostess wash the very dirty faces of two extremely dirty little urchins with still dirtier noses in a wash basin, the contents of which she assured us were afterwards transferred to the kettle, boiled and manufactured into the coffee we had enjoyed so much…Still, what the eye did not see, the heart did not feel.”

Stabb and Glascott were shown around the Bluejacket mine[xxii] by Hugh Dobbie, an Australian miner working for the London and Limpopo Company. A very detailed account of the workings are given; “very old workings extending for a considerable distance underground were long known to have existed here and it was on the site of them that the London and Limpopo Company made their excavations…the old tunnels and passages appear to have been very low and contracted, though chambers were in some places excavated to a very considerable size. The recent workings have in many places obliterated the old, but they always seem to have followed them…If they are the work of the early Portuguese discoverers,[xxiii] it is strange that no iron implements of any kind have ever been found here; large round stone hammers are frequently to be met with and everywhere are traces that fire was the agent used to crack the quartz in the reefs before it could be worked out with the stone hammers.[xxiv]

…The fields are not being worked now, they are indeed practically abandoned, as the London and Limpopo Company has been wound up and are in liquidation and even a new steam quartz-crushing machine is standing without protection of any kind, exposed to all weathers and going rapidly with what other plant remains here, to ruin, no one being left to guard or look after it.”[xxv]

One of the reasons that Tati became so useful to travellers was that Dobbie had tools and a small forge so that repairs could be effected on waggons; indeed, Stabb writes that Phillips and Oppenshaw stayed at Tati to repair Westbeech’s buck waggon the wheels of which were pulling to pieces.

Meat was short; they shot an ox and Glascott brought back the head of a hartebeest (Alcelaphus buselaphus) but the servants failed to find the carcase and Harrison shot a young warthog, but the remainder of the troop hearing its’ cries, charged him, and he was forced to climb a tree. Stabb and Dr Bradshaw shot a zebra, but because they were far from camp had to cover it up with branches and fetch it next morning.

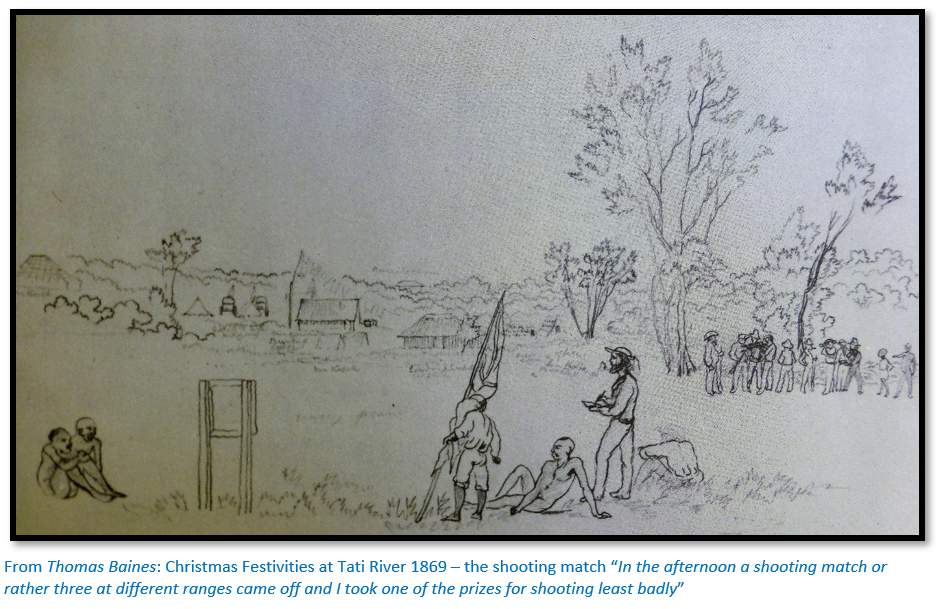

16 July: “As this was Mrs Francis’s birthday we all dined with her in honour of it. Old John Gosling cooked us a capital dinner of all sorts of luxuries and having made an oven in an antheap, baked fresh bread and a capital pie. I found that we had some raisins in our waggon, so he gave us a first-rate plum-pudding and also manufactured some capital jam tarts. Altogether the dinner was a great success and Francis made us happy by producing some beer which he had packed for the occasion. A rubber of whist and a merry evening followed until bedtime.”

Because of amaNdebele fear of redwater disease (transmitted by ticks) being imported into Matabeleland, all the waggons were stopped at the Ramaquabane river and Westbeech, Fairbairn, Francis and Stabb continued on by horse reaching Gubulawayo by 19 July. Lobengula arranged for his own men to look after the party’s oxen and sent his own trek oxen down to the Ramaquabane to bring up Stabb and Phillips waggons. T. Petersen lent oxen to haul Fairbairn’s waggons; Henry Byles took the oxen down and the remainder of the party were at Gubulawayo on 6 August. [For details of the journey from Tati to Gubulawayo see the article The Hunter’s Road – followed on maps under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

On the way up they stopped at John Lees farm, but he was away hunting, so they sheltered from the cold and wet on his verandah…Stabb noticed the vegetation has also changed from mimosa [Acacia] and thorn scrub to matchiobell [Itshabela in Ndebele or Mfuti in Shona] (Brachystegia boehmii) and gogonda [mountain acacia] (Brachystegia glaucescens]

Stabb meets Lobengula

“As it was bitterly cold and wet we accepted hospitality of her house [an inDuna’s wife] a circular hut about 14 feet in circumference of mud walls and circular wickerwork roof resembling in appearance a large beehive, with a small door not above 18 inches high, through which one had to creep on hands and knees as the only mode of ingress and egress. Now as many visitors crowded into the hut to stare at the strangers as it could accommodate and a large fire of wood was lighted in our honour in the centre, the only exit for the smoke being by the door which also afforded the only ventilation, our situation can be better imagined than described. The smoke got into our eyes and made them smart to that degree that it together with the heat continually drove us out for respiration into the open air, but there only to meet with rain and cold which in its turn drove us back again…we composed ourselves to sleep as best we might with 4 Europeans, Westbeech’s servant, 4 women, one of whom had a villainous cough and 5 children…”

19 July: from Mabukutwane “We passed on our way the kraals of Magowain [Magokweni, the Emgokweni regiment kraal] Myandin [Umganen kraal] and Umhlahlanhlela [Mhlahlandhlela] and reached Gubulawayo 18 miles without off-saddling at about 10:30am. Everywhere since we left the waggons at the Ramaquabane the veldt has been magnificent and the crops round the various kraals forward and plentiful. There has not so far appeared to us in this country any of those distressing signs of poverty which were frequently visible in the Bechuana country.”

Stabb had a letter of introduction from Sir Henry Barkly, Governor of Cape Colony (1870-1877) which John Boden Thomson translated for LoBengula, who pleased with the respect shown, subsequently did what he could for Stabb.

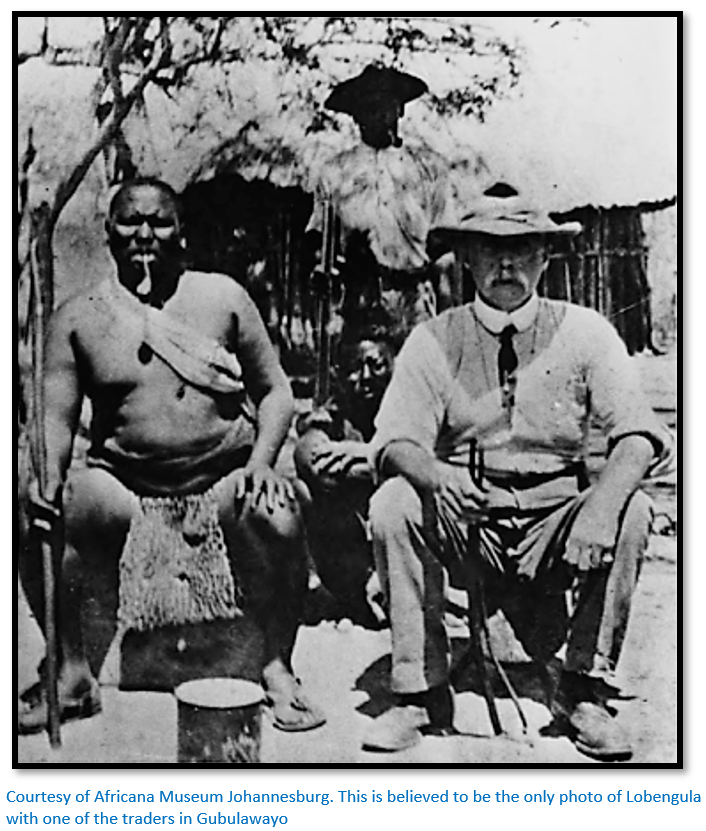

“The king’s kraal is situated nearly in the centre of the town and consists of a long low thatched house of one storey high with a verandah running the length of the building in front, built after the European style by an English trader called Grant[xxvi] and a few huts of the same pattern as but larger and more elaborately finished than the one we had slept in at Mabukutwane, occupied by some of the King’s wives, to each of whom a separate one is appropriated by his favourite sister[xxvii] who never leaves him and whom we are told he consults in all his affairs…”

“…We found the King a handsome specimen of a man with an intelligent yet kindly countenance reclining on a pile of karosses in his sister’s hut. He was dressed in European clothes consisting of a pair of cord trousers rather the worse for wear, a dirty flannel shirt ornamented with various figures of foxes heads and dogs, a tweed cot and a pair of lace-up boots with a billycock hat in which was stuck a feather…The King expressed great delight at seeing us and Nini (his sister) who appeared to be almost literally bursting with good nature had at once set before us a large wooden dish of cooked beef and a calabash of beer. Before any was touched however the slave girls who brought the viands in on their knees were made to partake of each portion to show that it had not been trifled with.”

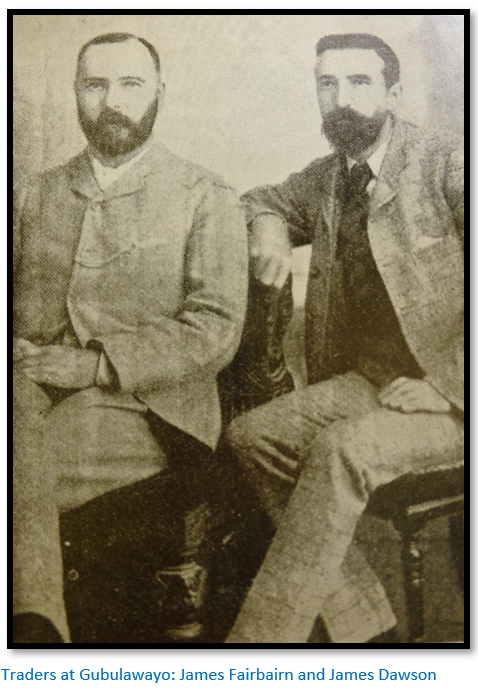

“In the evening we roamed amongst the traders stores and formed the acquaintance of the white people here, whom we found to consist of Harry Schuch, a young German and Fairbairn’s employee, Bill Horn, a trader and his wife and Golden employed in his store, Petersen, a German and trader formerly a servant of Phillips, Greite, also a German and a trader and his wife, Clarkson a partner of Horn’s, Deans, French, McKay, Tainton, Byles and Grant, all trading for themselves or for Taylor at Sechele’s, whilst the Revd. J.B. Thomson, the resident missionary, whom I also met in Dean’s store lives with his wife and family at Hope Fountain about 3 miles off, where is also another white man, by name John Halyet, employed at present in finishing Mr Thomson’s house.”

Amongst the traders the conversation was about the threat of redwater disease and how some traders may have exaggerated its threat to keep others out of Matabeleland. “Mutual recriminations, innuendoes and indignant denials were pretty generally bandied about but nothing came of them beyond a consumption of various wets of brandy, several bottles of which appear to have been reserved for our arrival…” Stabb thought life here was much harder that at Shoshong as servants were difficult to get, goats and sheep were scarce and beef only obtained from Lobengula, so most meals were of porridge or sadza. “For this the traders have to thank themselves in a great measure, they are as a rule a thriftless lot and trade creates a great jealousy amongst them; did they only work together they could without difficulty provide themselves with milk, eggs, poultry and many luxuries which they now rarely get.”

23 July: “…A most absurd scene occurred this morning, Fairbairn had brought up some common masks and a wooden snake, such as children play with, with which he frightened nearly to death all the native girls in the neighbourhood of the stores. The King however was much amused and insisted upon putting on one of the masks himself, much to his sister’s (Nini’s) horror, who being very superstitious berated her brother well, telling him that he would now have no good luck since he had been playing with dead men’s faces. He however did not care but kept on asking Fairbairn to put one on and go out to frighten the IzinDuna’s, which gave him much amusement.”

Fairbairn had business at Inyati from 27 – 31 July and Stabb accompanied him while his fellow officer Glascott was given permission to go hunting in Mashonaland; he left on 14 August with Phillips and Harrison. Glascott shot twelve elephants, but Harrison became ill and had to be sent back to Inyati where Robert McMenemy, a young Irish trader and blacksmith, cared for him. Stabb is very complimentary of McMenemy saying: “McMenemy is an Irishman and before coming out to this part of the world had been a gardener. He can turn his hand to anything, has a capital poultry yard, plenty of cows giving milk, grows vegetables for himself and is a capital baker and cook, consequently the fare here is very different to what we have been in the habit of finding at other traders…” Glascott arrived back at Lobengula’s kraal on 2 October and did not visit the Victoria Falls.

1 August: “…Found him [Lobengula] just on the point of starting with his waggons for Matsheumhlope[xxviii] about 8 miles off and most of the traders accompanying him as nearly all trade in the country is done either with the king himself or where he happens to be. He looks upon all the ivory of the country as his property and no one is allowed to retain or barter any except by his special permission.”

2 August: fever was an ever-present danger. “Horn is very seedy he sent a waggon under Golden to Matsheumhlope but could not go himself. Went down to see him in the afternoon and found him better, but he looks as yellow as a guinea and I am afraid his liver is very bad.”[xxix]

3 August: “It appears now, from what Raybuck[xxx] tells me that Thompson (his friend) has obtained some shooting veldt in that direction [Mashonaland] and that he himself is going in a waggon trading with the King’s consent among the Mashona kraals, but that the object of both is rather to prospect and that if there is gold equal to their expectations there, there are plenty of white people in the country, [South Africa] many old Australians, only waiting their report to rush it and work it in defiance of the Matabele people.”

5 August: Horse-sickness was also a very real threat: “Borrowed Horn’s horse, a very good grey and one of two only that he succeeded in saving out of 12 that he brought into the country but a few months ago. All died of horse sickness[xxxi] except these two which recovered and are now salted.”

6 August: the waggons arrive from the Ramaquabane drawn by Lobengula’s oxen. Glascott tells Stabb he had good hunting and had rather a narrow escape himself “whilst galloping after a herd of blue wildebeest, his horse Pumpkin put his foot into a hole and coming heavily down nearly rolled over him, whilst in the scramble his rifle by some means went off and the bullet passing through the sleeve of his coat cut the skin of his arm and grazed his neck in which a great portion of the powder composing the charge was also lodged. Luckily no further damage was done and he was alright again after his accident.”

Fairbairn had brought up a waggonette for the King and after drinking some of the champagne which Phillips and Westbeech had presented to the King: ”…we sallied out en masse to inspect the waggonette, the King savage-like exhibiting the impatience and pleasure of a child in anticipation of a new toy…It is a really substantially built good carriage and the King was delighted with his new toy especially when it was explained to him that it is a better one than his rival Sechele has, of whom he has always been jealous and he readily agreed to give Fairbairn the 20 large bull elephant teeth that he said it would cost.”

9 August: “Thomson rides over in the morning and has breakfast with us after which we go to the King with him and have a long interview. Thomson explains to him that we have brought a letter from the English Governor at the Cape commending us to his protection and that he must consider us as his children whilst in his country, to which the King replied that his country is quite open to us and that we can both go whither we decide upon and that he will provide servants and guides for us during our sojourn. He discouraged our idea that we might start in company for the river Gwayi from which I might branch off for the Victoria Falls…as he declared that the road was excessively bad…he strongly advised my going direct to the Falls, which he says I could reach in about 10 days and then returning” here before going on to rejoin Glascott where he might be shooting.

Lobengula also promised to lend Glascott a span of bullocks to pull the waggon which will accompany him. “Thus our arrangements are satisfactorily made and we decide that as soon as all preliminaries are complete, Glascott with the waggon will start towards the Mashona country where we hear good reports of the probability of elephants, but from time to time he will communicate his whereabouts to Robert McMenemy at Emhlangeni[xxxii] so that on my return I may be able to pick him up.”

10 August: “on arrival at Gubulawayo we at once set to work rearranging the waggon load and leave in Fairbairn’s store all articles we shall not require to take with us.”

12 August: “Whilst here he [Lobengula] was immensely amused with some rough tattooing of a mermaid and other devices he noticed on Harrison’s chest and arms and with which savage (or child) like he was highly delighted…The nights and early mornings are so bitterly cold that we rarely take a bath ‘till sometime after the sun has been up and this morning whilst on the bank of the stream I managed to slip in and got an unintended one with my clothes on.”

13 August: “We (Wood and I) merely take a blanket each, two flannel shirts, 3 pairs of worsted socks, a complete change of clothes and one pair of boots, besides what we wear. I also carry a pair of veldskoens, one tea kettle and a gridiron between us, a tin mug, a tin dish and a fork and spoon each. A supply of coffee, tea, sugar, salt, pepper, flour, rice, a bag of biscuits, a small piece of bacon, a few pickles, some soap and a small box of selected and useful medicines with a couple of hatchets and our ammunition, lead ladle, bullet moulds, etc. completed our kit which I do not think we could have made smaller. I decide upon taking my double No. 12 rifle, one express and my double shotgun, also Wood’s Snider and I shall probably also have to get a muzzle-loading rifle from Fairbairn for the headman who goes with me and to whom I shall have to present it afterwards if all goes well.”

Fairbairn says he can spare Harry Schuch to go with Stabb: “This would be the very thing; he can speak quite enough of the language to be useful and moreover would also be a companion.”

16 August: “After dark Fairbairn had several of the Matabele come to him to trade in ivory and feathers; this is quite an illicit traffic and carried on under the cloak of night so that none may see them. All the ivory killed in the country is claimed of right by the King and he is very strict in enforcing it; the ostrich feathers also nominally belong to him, but he does not look half so sharply after them as he does after the ivory; but both are at times smuggled quietly in to the traders.”

Stabb walks to the Victoria Falls

Stabb, his soldier-Servant Wood and Harry Schuch, a young German who works for James Fairbairn at Gubulawayo with an inDuna Gleite and carriers supplied by Lobengula left on 18 August following the approximate path of the A8 national road north west from Bulawayo, then north between the Umguza and Xoce rivers, crossing the Insuza to the Bembesi river which was followed to its confluence with the Gwayi and descending the Gwayi to Dett Valley. He then crossed the Inyantue, Lukosi, Deka and Matetsi rivers to reach the Falls on 7 September 1875.

18 August: After much wrangling and difficulties over payment and allocation of the carriers loads, Stabb is nearly at the end of his tether: “Another difficulty. Will they never end? I have almost begun to despair of ever getting away!. One man snatching a small axe and kettle and trying to make off with that alone, whilst they put all the lead and heavy ammunition onto the smallest and weakest of the party.”

In about 2 hours and 40 minutes after starting they passed Umhlatusa’s kraal. In 1 hour and 20 minutes beyond came to Muntu’s kraal, a half-brother of Lobengula and 10 minutes later crossed the Umguza river and 25 minutes beyond reached Umdwebe’s kraal where they halted for the night.

19 August: “Still all day among the Matabele kraals. Soon after starting we passed a large one on our right which we were told belonged to the Imbizo regiment[xxxiii] They followed roughly the path of the Umguza until its confluence with the Tegwani just after Likunya’s kraal and stayed the night at Mahlaumpondo kraal.

20 August: Gleite the inDuna in charge annoys Stabb with his persistent quest for gifts, but finally accepts a cotton shirt from Schuch after persuading Stabb to increase his carriers from 15 to 20. The carriers feast all day on an ox given by Lobengula.

21 August: Gleite and the carriers only turn up at 10 am. “Threats and imprecations were of no avail, so I lose patience and walk on…After some time I halted to see what would happen and soon after hearing the hum of voices, at least 60 men, women and children hove in sight, half carrying nothing, but I espied quantities of calabashes of beer on the women’s heads.” Gleite assures Stabb that the loads have been properly distributed and the remainder were simply friends who came to see them off and the beer had been brought by the women as a parting gift for refreshment! They cross the Tegwani river and halt the night at Tichola kraal.

“The country we had passed through is for the most part flat. But intersected with ravines, which made portions hard walking. It is everywhere thickly covered with wood, much of it large timber and all the kraals we passed had large gardens well cultivated around them.

All our beds were arranged in the same way, i.e. everyone slept with his head towards the hedge[xxxiv] and his feet towards the fires; in the centre were we three Europeans and directly beside us Gleite and his own servants and then again on either side the rest of our followers. Immediately behind our heads were piled rifles and guns, whilst the natives had assegais and shields, for of course all were armed, but only two of them, besides Gleite, had anything in the shape of a gun and those only wretchedly old muskets, were hung all round on the inside of the hedge. I however always keep one rifle ready to hand at night under my blanket and also take the precaution of having my revolver under the spare suit of clothes which answers for my pillow.

…And far into the night groups sat around the different fires smoking dagga, a kind of wild hemp I believe, which they inhale into their lungs ‘till a violent fit of coughing ensues, when the smoker passes the pipe (one only being among each group) to his neighbour and putting a straw in his mouth lets the saliva, in his intervals between coughing, drip down along it onto the ground. This goes on sometimes for hours.”

22 August: “The women and children return to their kraal and a few of the men, but after they had left I found I still had 40 left who professed their intention of accompanying me the whole way. I called upon Gleite for an explanation and he says some are his own slaves whom he wants to attend on himself and the others some Matabele gentlemen who wish to accompany me for their own pleasure and whom he says the King gave permission to go as long as they were back in time for the next crop sowing. I have learnt by experience that argument avails nothing, so I submit, but tell Gleite that I do not consider that any beyond the 20 belong to me and that if the others go they will have to find food for themselves…

…In 5½ hours after starting we came upon a Makalaka [Makalanga] kraal, Guzuan’s and ½ hour beyond it upon the Insuza river where we found plenty of water and had a most refreshing wash. Continued again ‘till about 5pm when being assured by our boys we halted and made our scarum [scherm] for the night in the wood…We were both tired and thirsty…intense disgust we discovered on arrival of the natives that one of our calabashes had been left behind at Gleite’s kraal and that another had been carelessly broken against a tree on the journey, so instead of having one each we were now reduced to one between the three and that one not nearly full…I insisted [in spite of Wood’s protests] therefore we should be sparing as possible of what we had and keep some for breakfast in the morning; but fancy my disgust when preparing supper to find one of Harry’s boys using our precious water to wash dirty plates. Did I not rush at him and make him pour back into the calabash what he had on the plates…

…Our entire route today was through a fine forest with magnificent timber, but the road for the most part was very sandy which made walking tiring. Walked very fast and exclusive of stoppages 6½ hours, about I think 22 or 23 miles.”

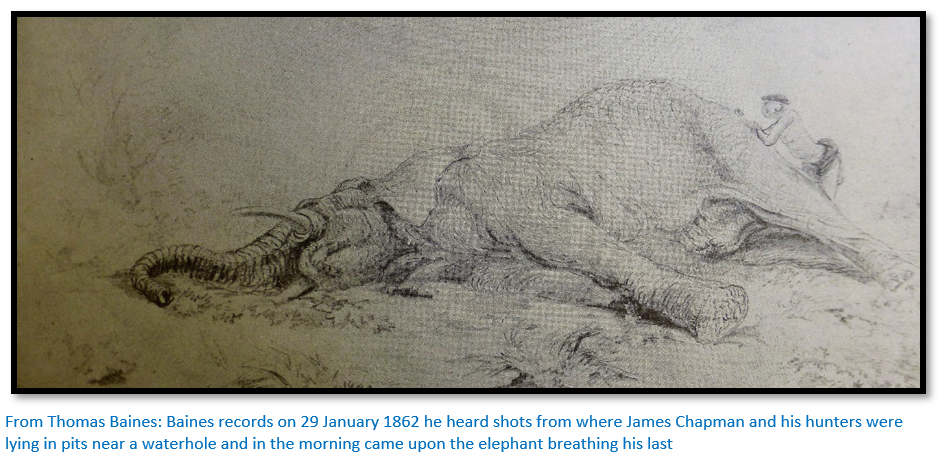

23 August: “About 5:30am we had a visit from some hunters who were returning to the King with the ivory they had collected and I was awakened from my sleep by the apparition of two men standing at the foot of my blanket each with an elephant’s tooth over each shoulder…my first impression was that they were buffaloes grazing at me and my first impulse to snatch my rifle, but on stirring up I soon discovered and heartedly laughed at my mistake…

…Started at 6:30am and after 3 hours and 10 minutes walking reached the Bembesi river where water was to be got in plenty and where at length we drowned our thirst.

…An hour and ten minutes’ walk from the river brought us to some Bushmen’s hut [San Khoisan hunter-gatherers] about 3 or 4 in number, where we found merely a man and a woman, the rest were away and as they were Lobengula’s subjects and hunted with his hunters, they were known to our people. They had some water stored in earthenware jars but were very irate if any of us ventured to take a drink from them. Here we first came across the tsetse fly and an innocent enough looking thing it is to work so much ill, but little larger than a common housefly and with its body striped black and brown…[xxxv]

…After leaving these huts in which the inhabitants seemed to live entirely on roots, wild fruit and the dried meat of such game as they can catch in game pits, for there was not a sign of cultivation in their neighbourhood, we came upon a small river called the Bembezaan, a tributary of the Bembesi, which latter we crossed in the afternoon and about 3:30pm encamped on its bank and luxuriated in a glorious bathe and wash…”

In the evening after dark some of the carriers went down to the river and accidently set the bush alight with their firebrands. At first they thought of moving to a new camp but the flames advanced so quickly there was no time and they back-burnt a space around the camp: “we set to work and ourselves fired a space immediately to windward of our scarum and beating that down with such implements as we had managed to clear a belt before the advancing flames had reached us, roaring and scorching, without however doing any damage beyond making us hot and anxious…

…Our road today was wooded throughout, a portion through fine large bush, but a portion through scrub and much varied in character, sometimes through deep sand and again over flinty and rocky ground. We walked exclusive of halts a little over 6 hours, I imagine about 21 miles.”

24 August: “Off about 6:30 am and about 11 am reached a small hunting post belonging to Matabele Bushmen [San Khoisan hunter-gathers] where we saw a few wretched specimens of men, women and children engaged in drying strips of elephants and other animal’s flesh in the sun…

…They live in a miserable state, wretched huts, no kind of clothing beyond a strip of hide, no cultivation of any kind, their food roots, wild fruit and beltongue.[xxxvi] They look diminutive and wretched and though these are subjects to the Matabele nation and so as it were have some sort of status, yet they appear as outcasts and to have that cunning furtive look that seems to belong to hunted races…

…Their mode of procuring game is mostly by traps, large holes being dug in the tracks used by game to go to water at night, or a thick heavy beam with a poisoned assegai head stuck in the centre being slung between two poles or trees over such path and ingeniously held there by means of a rope of hide…A very few have old rusty guns, but nearly all bows and poisoned arrows which although small are so virulent in their effects that a very small wound will produce certain death and the stricken animal is patiently followed ‘till he rolls over in his death agony…”

…Our usual plan of walking now is to start as soon as daylight having had previously a cup of coffee and a biscuit or cookie[xxxvii] and perhaps a bit of cold or broiled meat, walk ‘till about 11 am, halt for a couple of hours and have some broiled meat and a cup of tea and then on again ‘till such time as will enable us to construct our scarum before dark [preferably near water]

At our noonday’s rest we tried some of the elephant beltongue and dried trunk, both of which are as nasty as man could wish, but the carriers seemed to enjoy it, first hammering it with sticks to endeavour to make it a little soft and broiling it…We had not walked again more than an hour in the afternoon when my boys insisted that we must stop for the night near a pond in the river as they declared we should meet with no more water ‘till it joined the Gwayi. Walked exclusive of stoppages rather over 5 hours, about 17 or 18 miles.

25 August: Start at first streak of dawn as I am now very anxious to get meat…at length sighted some kudu feeding on the banks of the river…one of the boys with me who is a very keen and sharp lad did good service and amused me much by picking up a handful of dust and letting it fall gently from his hand to see exactly from which direction the wind blew. At least however I got a chance and knocked over a fine young bull in the bed of the river…I soon made their hearts happy by the prospect of meat and sent some down to the river to cut up and bring in the beast…In a few minutes fires were blazing in every direction and in a very short time not only the flesh but the entrails, paunch and interior generally had disappeared within their voracious maws. A dog would have found nothing beyond a most cleanly picked bone with which to amuse himself...”

…Our route today commenced down the east bank of the Bembesi ‘till it becomes the Gwayi, where we crossed to the west bank and in the afternoon passed opposite to where the Bubi forms a junction with the Gwayi on the eastern side and encamped about sundown just above where a small river runs into the Gwayi from the west…

…I was very tired from my two long stalks [the second being fruitless as being too blown after running after the Matabele he missed the buffalo] so tried the Matabele remedy which I saw Gleite doing, viz. procure a good-sized bunch of leaves, damp them thoroughly, then set them on fire until thoroughly warm, rub your legs well over with them, repeat this two or three times and afterwards smear the same limbs with fat (that of rhinoceros if you can get it) It was most successful, every sign of stiffness soon disappeared and I slept as refreshed as possible, the only drawback being the rather strong smell of fat. Walked today exclusive of stoppages over 6 hours, about 21 or 22 miles.”

26 August: “Our journey today has been entirely through fine forest land, beautifully watered, but in many places terribly swampy which in the rains would be almost impassable. Four and ½ hours after starting we passed a small river [N’Kaboli?] which flows into the Gwayi and in 45 minutes beyond a beautiful rivulet of clear water [Umsemaka?] also running into the Gwayi and halted for the night on the side of a hill near a spring about 4:45 pm…Very long faces and empty stomachs in camp tonight and indeed I am myself getting anxious on the score of food…Walked today exclusive of stoppages rather over 6 hours, about 21 or 22 miles.”

27 August: “Soon after starting we saw some roan antelope feeding on a distant hill and tried a very long stalk after them…I tried a snap shot but missed, so our labour was all in vain. Never mind, better luck next time, and so it proved for we presently fell in with some roybuck [Southern Reedbuck (Redunca arundinum)] one of which I managed to bag though I rather stupidly missed a second chance. We soon cut up the carcass and divided it into 3 parts for my men to carry, who being refreshed by their savoury luncheon [the guts and entrails] set off at a good pace to seek our party.”

They met up with some of the party searching for them who told them the rest had crossed the Gwayi by a drift as the country on the east side was easier travelling and found Schuch and Wood and the rest waiting on the bank. “A cup of tea, a venison chop and a noonday rest were luxuries one felt one could now thoroughly enjoy...

…Joy in camp tonight, plenty of meat, no more hunger and did not our boys revel in the luxury. At least 12 or 13 fires blazed in front of our scarum and for half the night they were busy roasting, broiling, eating and gossiping…we walked today exclusive of stoppages about 7 hours, 24 miles I should say, as the pace is always fast.”

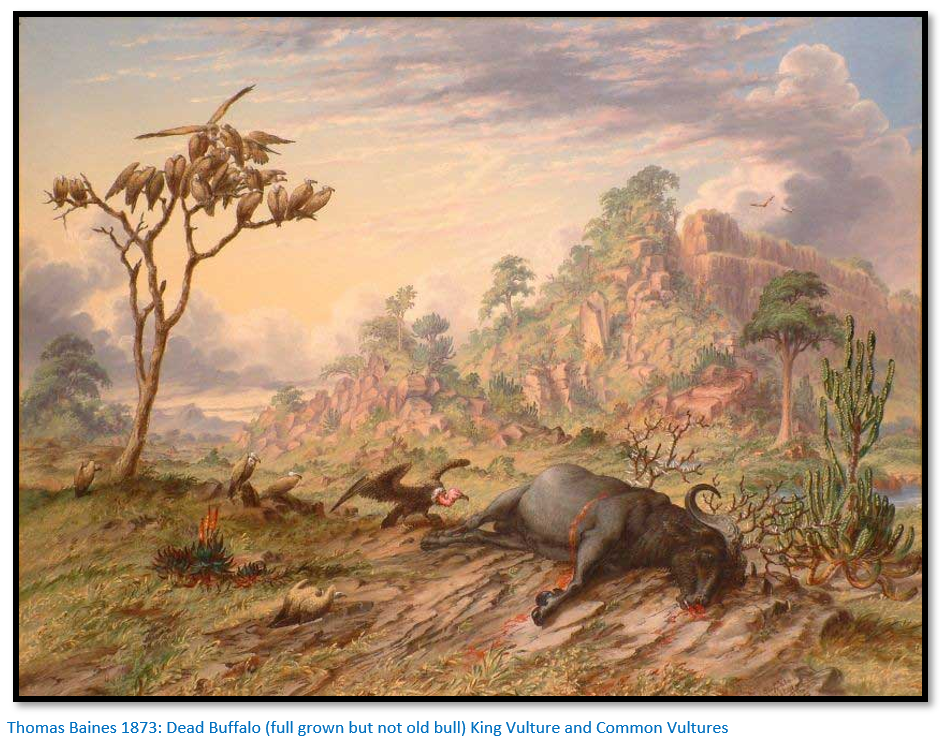

28 August: “Off about 6 am and intended to have done a good journey today…but after walking about 3 hours Gleite and I…came across a large troop of buffalo. We had a long and difficult stalk to get them…when I got a capital shot at a magnificent bull who was evidently on sentry for the troop as he was standing with his head up…The indispensable fire was now made…of course now all idea of further progress for the day was at an end.

Our route commenced today by crossing to the west bank of the Gwayi, but on account of the winding nature of the river we are following we had again to cross twice and eventually made our scarum on the west bank. Exclusive of stoppages our journey today was only about 3 hours or 10 miles.”

29 August: “Did not affect a start ‘till about 6:30 am as it took the boys some time to arrange their packages of meat…on starting we left the Gwayi for a more westerly route and in about 50 minutes came upon the Sandala rivulet, 20 minutes beyond which we crossed another rivulet called Dett and in another 1½ hour reached some old and deserted kraals…an hour and a half beyond these kraals brought us to the Inyantue stream where our carriers came to a halt and protested that they could not proceed as the next water was too far off to be reached before nightfall.”

They refused to go on and refused to fill their calabashes with water. Gleite tried to make them alter their determination, but he has little power over them. The real leaders are the 10 old men the King originally selected to accompany me and they are the most intractable of the lot…so we have to give up the whole afternoon and about 1 am form our scarum on the banks of the stream after about only 15 miles walk.

In the afternoon they saw a buffalo on a small hillock but as Stabb was creeping up it took alarm; when he ran to the hillock with the others he saw that it had been the sentinel for a large herd of 200. Stabb made a run to cut them off and met Schuch running as hard as he could and assumed he was also running for a shot. But the only answer I could get out of him was: “Run, run, they are charging us, man. Gleite has had his rifle knocked out of his hand and is up a tree. They are smelling the ground with their noses and are scenting us out.” It seems they thought the herd was galloping towards them, Gleite dropped his rifle and climbed up a tree whilst Harry [Schuch] had turned tail and bolted as fast as his little legs would carry him without either firing a shot.

One of their native hunters had joined the chase with his musket: “but in reloading his gun he somehow jammed the charge in the barrel, in endeavouring to extract which he somehow exploded the piece and was badly burnt by the gunpowder in both his legs and one of his feet, though luckily he escaped injury from the bullet.”

In the afternoon Stabb and Schuch went for a walk and gathered mkuna or mobola plums, a yellow fruit the size of a small plum. “From the top of the hulls behind our scarum we could see to the due east where the Shangani joins the Gwayi just below where they branched off from the latter river…Our journey today excluding stoppages was not more than about 4½ hours or 15 miles.”

30 August: “Trekked at first daybreak light and had not gone far before we saw a large white rhinoceros but failed to get a shot at him. However soon after espied a troop of 5 elephants…I took my double-barrel No. 12 leaving the express with my bearer to bring; a short run brought us within distance, when I badly wounded just behind the shoulder a cow which seemed to have the longest tusks in the troop, but also having hit a young bull which immediately turned out of the troop…They followed up the blood spoor very rapidly, too much so for me as the pace soon told upon my wind and got several shots at him again before I could get up, but at last they succeeded in bringing him to bay and just as I came up he was lashing himself with his trunk, violently trumpeting and in a great rage, ready to charge anything or body before him; as he was now right in my line and facing me only a few yards off I thought it better to give him a forehead shot to stop mischief, as I heard that that would almost invariably turn a charge, so I let him have one fair in the forehead and another into his shoulder, upon which he sunk down stone dead.

…On examination we found that the poor beast had been repeatedly hit, as many I should think as 10 or 12 times (though in no vital parts) which wounds had much added to his rage.

After walking for a considerable distance, for nearly 5 hours, our guides (which the 9 old men I originally got from the King professed to be) suddenly drew up on the bank of the dry bed of a river and professed they did not know the way, nor where the next water was. These 9 old scoundrels have been giving all sorts of trouble and have lately been as sulky as bears…They now sat sulkily down and savage-like would do nothing nor suggest anything.

Some of the younger now proposed that we should return to the Gwayi, follow it ‘till we came to its junction with the Zambesi and then so on to the Falls; this however I was unwilling to do…We decided therefore to continue due west…I told Gleite to say that as I could trust them no longer I preferred to follow my own devices and should put some of the younger ones to the front to find the way…After about an hour’s very fast walking we reached the dry bed of another and larger river and to our delight saw some people among the rocks at no great distance from us. They turned out to be a Matabele hunting party from Emhlangeni…The hunters were very communicative, but we found could really give us no information about the country in front, which was terra incognita to them.

We try for luncheon some baked elephant’s foot which we got from the hunters and which I find capital. It is gelatinous and resembles brawn, but nothing will persuade Wood to touch it. We walked exclusively of stoppages today about 5¾ hours and very quickly, so we must have come I calculate 19 miles through a densely wooded country.”

31 August: “Our road today has been through a very mountainous and densely wooded country, broken up with deep ravines all thickly wooded, so the walking was bad and arduous.

We were astonished this morning by the appearance right in front of us of a large rhinoceros who without any provocation came direct for us…His little pig eyes gleamed with the utmost astonishment and he came on tossing his head about in great wonderment evidently thinking to himself, who and what on earth are you to come disturbing me in my domains? Most of my fellows dropped their burdens and nimbly hopped into the bush, I waited ‘till he was within 20 to 15 yards from me, when I gave him both barrels of my No. 12…Master rhino was considerably astonished at this rough reception…and turned badly wounded into the bush…but in the terribly thick bush we failed to get up to him.”

They crossed a number of dry streams before coming across a larger river with good water in several pools and one of a number of search parties sent out managed to find a San Khoisan hunter-gatherer and his wife. These people lived in mortal terror of the Matabele, but they managed to persuade them they meant no harm.

1 September: They leave for the San huts that are reached in about 50 minutes. The male: “was actually shivering with fright, looking around with an expression exactly similar to that seen in a beaten hound…Bushmen are looked upon as mere vermin, destroyers of game and are in a general way hunted out and themselves destroyed whenever found.”

“We soon put both more at their ease by assuring them that we would do them no harm and presenting them with a few strings of beads to show that our hearts were white towards them” and explained they needed guides for the Falls. The man said he did not know the way and if he left their hut would be robbed and he and his wife left to die, but that he could take them to a larger kraal and so he did. Stabb says it was so cleverly hidden in the rocks that they would probably have passed it without noticing it, but when they arrived everyone had fled except three men with assegais.

Gleite explained his men would not rob them or take them off in slavery; we were just looking for guides to take us on our way tomorrow. “These people are not likely to be very favourably disposed towards us as they only know the Matabele as their destroyers and enslavers.” But persuaded they were peaceably inclined, they summoned some of their companions from their hiding places including two who had been in Westbeech’s employment as hunters and were on their way to Pandamatenga at his trading station in the hopes of further employment. Stabb said he will employ them as guides to take some of his men to Pandamatenga for supplies. [See the article George Westbeech and the road to Pandamatenga under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Stabb went out hunting and missed a kudu, but they saw vultures circling and came across a buffalo in a game pit: “His neck was broken and he had evidently been dead for several days for he was much swollen and stinking vilely. In a moment they were in the pit and in another he was laid open by their assegais and though the stench was too great for me to stand near, nothing would induce them to leave ‘till they had cut off a leg and other pieces of meat…”

2 September: “Before starting Gleite obtained a guide to show us the way to the next kraal which we found was not far distant, but here as at the last we could gain no information regarding the direct route to the Falls. No one seemed to know anything about that part of the country though a lad here offered to take us to Pandamatenga which he said was not more than 4 days distant and to which he had often been to dispose of ivory and feathers to Westbeech in exchange for powder, etc…

Just before starting the guide was nowhere to be found and Schuch discovers that our friends [the 9 old men from the King] had privately got hold of him and threatened him in the same way as they had the Zambesi boys and caused the fellow to bolt in very terror. I am in rather a fix”

However Stabb persuades a villager to accompany them from kraal to kraal which are either perched on high rocks or hidden away in the forest: “The Matabele name is a very terror in the country and on our approach the kraals are for the most part deserted or nearly so, their goats driven off to the woods and their corn hidden.” The 3 white men go ahead and parley with whoever they can find before the amaNdebele reveal themselves and this generally calms the fears of the villagers enough to give information.

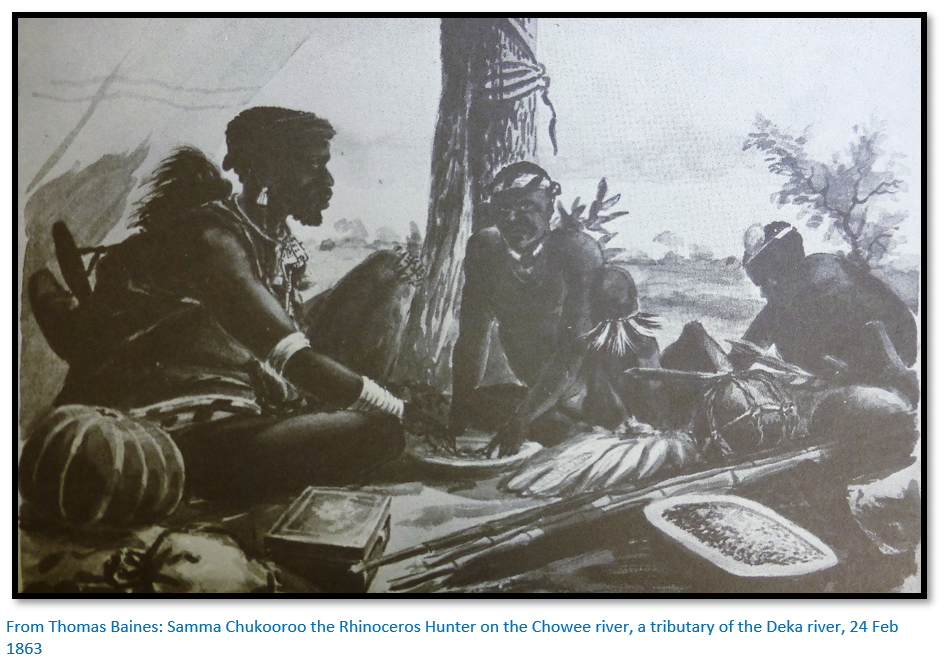

“Our journey today has been through a rugged, broken and mountainous country everywhere very thickly wooded[xxxviii]…We reached in the evening a river called the Deka and at a nearby kraal traded two ivory tusks of 15 lbs each (7 kgs each) for a bag of powder, a box of caps, 65 bullets, 1½ lbs of lead, a knife, and 5 yards of calico; not a bad buy!”

3 September: “Find that our flour, rice and sugar are nearly finished” and Stabb decides that with the villagers’ help they may be able to reach the Falls direct, but decide to send 3 carriers with a letter to George Westbeech to Pandamatenga and get supplies and meet them at the same kraal on their return from the Falls.[xxxix]

“…We start about 7 am on our outward journey in a north-westerly direction. I still stuck to my plan of always having a villager with me, so we accordingly carried off a couple of men from this kraal as guides with us and in 1 hour 10 minutes reached the Machinge river where we found water…The natives appeared to be here well off and to have plenty of European cloth, beads and guns in their possession, mostly however of Portuguese manufacture and we find that we are now in the part of the country which is occasionally visited by Portuguese traders from the north and east.”

At each kraal they pass there are endless delays where the Matabele try to extort gifts from the villagers “to show that the natives hearts were white towards the Matabele nation.” At one kraal they learn that 2 white men, whom they supposed to be Clarkson and Deans, have been in the neighbourhood recently.

Makalanga Kraals become quite numerous, so that wildlife is scarce and the countryside is mountainous, broken with steep ravines and thickly wooded.

4 September: They pass through a kraal which has dogs, an indication that there are no tsetse flies in the area. They cross the Dendelinde river and 1 hour and 20 minutes later come to the Lobangwe river. “Our boys are greatly amused at Harry’s and my swimming about, at which they expressed great surprise, calling us fishes and saying we evidently could live in water as well as on land.”

Half an hour from this river brought us to the Matetsi where also we found plenty of water.[xl]

15 minutes from the river we came upon a large kraal (Toulouse’s) “We invariably find the villagers civilly disposed but in dreadful fear of our Matabele conductors and we always have to approach the kraals carefully, the white men going on in front lest so large a party should alarm them.”

5 September: “We start again about 8:30 am with what we have got. As usual we take on a couple of men with us as guides. About 1½ hours after starting they come upon some deserted huts where the inhabitants were evidently smelting iron. There was wood ready collected for their fires, small furnaces made of clay to hold the ore and trenches cut from them to lead off the molten metal as it becomes separated from the stone…My people were soon appropriating to their own use whatever they could discover in the huts and would, had they been left alone, have carried off every cooking utensil and article they could lay hands on. This however I made Gleite stop their doing but as they had found some buffalo meat Gleite argued that they were quite entitled to that as the country belonged to the Matabele…”

Supplies of rice and flour are short and Stabb decides it needs to be rationed daily. Schuch sees the necessity of this, but Wood the soldier-servant: “declared that unless he could get flour, rice or vegetables he would never live to reach the Falls and that it would be impossible for him to live on meat alone.” Stabb quietens him but remembers that Livingstone remarked that one of the first symptoms of fever is a person being dissatisfied with every arrangement.

6 September: “Our rice and flour which we have been husbanding with such care for the last few days are now at an end and our sugar gave out a day or two ago…Luckily we have coffee and salt in abundance, a small quantity of tea and plenty of tobacco, though of that only native-grown.”[xli]

“We started this morning about sunrise and after a little over 2 hours walking distinctly heard from the top of the hill a sound like that of a distant roar which my guide assured me was that of the Falls, though he had never been there himself.

We here came upon a Bushmen’s scarum…at this scarum we procured a Bushmen who had been as far as the Falls and sent back the two guides we had taken on from Toulouse’s kraal…While resting we were surprised at seeing a number of men approaching, amongst whom was a white man. I immediately went forward to meet them, but no sooner did they perceive the dreaded Matabele dress among my followers than nearly the whole dropped their loads and fled into the bush. The newcomer turned out to be a Mr Vean (a Swede I think) an employee of a trader standing at Pandamatenga which he described as being 3 days journey from this.”

Vean[xlii] had been sent to buy grain from the Makalanga in the Matetsi river valley.

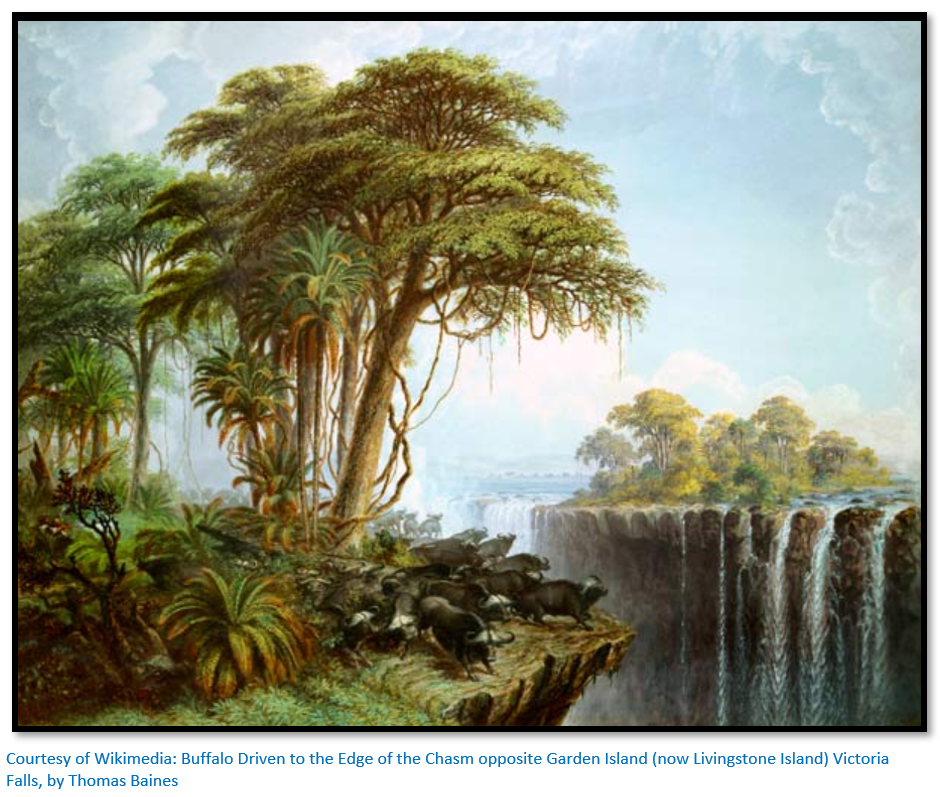

“After bidding our friend adieu we resumed our journey in great spirits and in about ½ hour after starting on coming to an opening in the forest we looked from an eminence over a vast and beautiful valley across which we could see plainly in the distance the great spray cloud arising from the Falls hanging over the horizon whilst the rumbling of their distant thunder became more audible to our ears…I could scarcely realise that here I stood in Central Africa, gazing upon the place where existed those wondrous falls in a country which had from childhood strongly excited my intense interest and imagination. I fully expected to awake and find that what I was looking upon was nothing but the chimerical fancy of my brain.”

“After again resuming our journey 1½ hours walk brought us to a small stream where, as it would appear we were yet 5 miles distant from the Falls and it was getting late, we decided to make our scarum for the night.”

7 September: “1½ hours walk, about 5 miles brought us to the Zambesi, so it must be fully 20 miles off that I yesterday heard the sound of the Falls. The total distance that we have come from Gubulawayo I calculate at about 334 miles (538 kms)

We made the river about 1½ miles above the Falls, being taken here by our guide as the point to which any Makalanga, who would be willing to trade with us, would come to. Not to alarm the Makalanga by sight of our numbers I left all my Matabele followers except 3 carefully concealed in the bush about a mile from the banks of the river and the 3 I proposed taking on I made conceal the ring on their head (the distinguishing mark of a Matabele soldier) by tying around it a strip of calico in the shape of a turban.

Thus prepared, Schuch, Wood and I with the guide and the 3 men mentioned above went on to the banks of the river which however we had to pursue for a considerable distance ‘till we could discover an opening in the thick bush which would admit of communication with a boat…At last however after a diligent search we discovered an opening in the shape of a leafy archway in the tangled bush which gave access to a most beautiful tiny cove with a strip of silver sand and which our guide pointed out as the usual landing place.

Here then we came to a halt, lighted a fire and fired off several shots to indicate our presence…we thought we heard dogs barking and were rather surprised however at no further notice being taken of us, so fired again and again repeatedly…we eventually discovered [the sound of barking] to proceed not from a dog, but from a bird, but so exactly were the notes similar that it had at first deceived us all and even in the end Wood would not be convinced and he and Schuch had quite an angry altercation about it, Wood asking him in his usual obstinacy whether he took him for a fool that he thought he was unable to distinguish between the bark of a dog and the call of a bird.”

For a long time, about two hours I should say we continued firing, shouting and making signals from the top of a high tree…when to our delight we at last saw a canoe with 3 men in it make its appearance from behind one of the islands in front of us; they were soon opposite to where we were but would not approach nearer than about 30 yards from the shore ‘till they were persuaded that we had no hostile intention.

…Seeing that we were Europeans and not recognising my followers their fears were allayed and they brought their boat ashore at the little cove where they moored her. I first as an earnest of goodwill made a present of a bunch of beads each and a knife and strip of calico to take over to their chief and then explained that we had originally started from the Matabele country and that I had some carriers still behind who would presently be here with my things.

They were thus quite prepared and were not at all surprised at seeing shortly after, the arrival of the rest of my party who having observed the boat coming across had left their hiding place and come on to join us. Being now fully persuaded that we were not bent on mischief they remained in friendly conversation with some of our people for a considerable time and left evidently pleased with their presents promising to return in the morning with both corn and goats.

In the afternoon, Schuch, Wood and I with Gleite and a few other of our people visited the Falls, the roar from which, strange to say, is not nearly so perceptible in our scarum on the banks of the river as it was many miles back before we struck the Zambesi. We returned in the evening thoroughly drenched for the spray sent up from the falling water returns in the shape of a fine rain for a long distance all round its neighbourhood and prevents your being able to gaze at this wonderful phenomena except at the price of a complete soaking.

The Falls themselves are wonderful, beautiful and grand beyond description and any preconceived idea must fall short of the reality…I wish Glascott was here; how I have missed him on my journey up! I want somebody to talk them over with, to sympathize one with the other. I am sure neither Wood nor Schuch recognise either their beauty or grandeur. Wood merely sees a lot of water falling down…and as for Harry he would be far happier drinking beer and bargaining for a tusk of ivory in a store at Gubulawayo…

Standing at the brink of the chasm, the roar of the falling water is so tremendous that it is simply impossible to make one another hear except by shouting as loud as possible close into each other’s ears. Garden Island[xliii] we cannot reach from this side without boats, but on the promontory opposite to it grows magnificent fruit trees, which we readily availed ourselves of and among them many huge baobabs stretched their gaunt branches, but at this season they were not bearing.”

8 September: “Leaving Schuch and Wood to do the trading with our friends across the river…I started off immediately after breakfast determined to spend the day in exploring the neighbourhood of the Falls and now that I have returned I can understand them better. They are marvellously grand, but it would be impossible to convey any description of them in words…but the impression left by the magnificence of the panorama which has been before and around me all day can never be effaced. Once beheld it must forever be a cause of wonder, even to the least impressionable man, if nature has not unkindly or he himself wilfully closed his eyes to all external influences which the wonders of nature and the beauties of scenery always have on healthy minds…

To convey any just idea of these Falls is hopeless; but try to form some conception of them and their surroundings, let one imagine a vast river of perhaps 1½ miles in breadth flowing peacefully, shiningly on, through a broad and beautiful valley between banks thickly clothed with rich tropical vegetation in wildest profusion and beneath a faultlessly blue vault imparting its own colour to the water below, whose sun-dappled bosom is everywhere studded with numberless beautiful islands, overflowing with all the prodigal luxuriance of the tropics and seemingly almost bursting from very richness as the foliage stretches out far over the water where it is again mirrored so as to ender it almost impossible for the eye to determine where reality ceases and reflection commences.

Suddenly and without a moment’s warning, right athwart the entire bed of this hitherto peaceful river occurs a mighty rift, the walls of which on either side go sheer down for nearly 400 feet[xliv] forming a frightful chasm into which the waters of the river disappear. The original bed of the river on both sides of this huge rent remains as it used to be before the earth yawned and this vast fissure appeared; the bed has been simply rent asunder,[xlv] but on the far side now grow trees and grass and ferns where formerly the river flowed. Into this chasm nearly 1,900 yards in length[xlvi] the entire river rolls with a deafening roar. Imagine more than a mile of water suddenly precipitated over a sharp ledge into a black and yawning gulf. It does not however roll over in one huge mass; here and there an island or a pile of huge rocks along the edge of the chasm interpose obstacles which it cannot overcome and round which it must creep and thus it is separated into various cascades before the final mighty plunge is made.

At this season of the year the water is comparatively low and probably a greater amount of water in a given space may be discharged over the Falls of the St Laurence, but what these must be after the rains have fallen imagination alone can picture for as far as I know the eye of white man have never as yet then looked upon them. The deadly malaria of this valley at that season is too powerful an enemy to be coped with.

…On the side on which we stand facing Garden Island [now Livingstone Island] is a deep grove of rich evergreen trees, a grove of perpetual showers on which this fine rain is forever falling.[xlvii]…The ground is a standing marsh, the leaves are forever dripping, whilst ferns and mosses grow in the wildest profusion and magnificence; the deep gloom and perpetual rain of this evergreen grove, full of dank luxuriance but shunned by animal life render it an awesome and dread place to contemplate.

Emerging from this grove and creeping through the ever falling blinding rain, one gains the edge of the cleft and faces the river as it rolls into the fearful abyss yawning between you and it, perhaps 100 yards across.[xlviii] Looking down, one here sees this mile of water nearly 400 feet below, rushing, foaming, surging, and beating in its mad efforts to escape from the narrow chasm in which it is now confined and from which there is but one still narrower outlet; this outlet is not more than perhaps 20 or 30 yards wide is situated about ⅔ of the way up from the western end of the crack and towards it the waters of the Zambesi, precipitated over the chasm, roaring and rushing tumultuously from the east to the west, meet in fearful conflict, causing a boiling hissing whirlpool forever to surge round its only gate of outlet.

Escaping wildly through this outlet the river still finds itself confined in an equally narrow crack, but at right angles to the chasm in which it has fallen, down which it madly, blindly rushes, seeking room and rest but finding none. The channel however in which it is now compressed, formed by the same convulsion of nature as originally turned the river from its broad bed, has been cleft through the bowels of the earth in the form of a gigantic zigzag, so this boiling raging torrent has to follow its torturous path between huge basaltic wall of nearly 400 feet high, round promontory after promontory for many miles, ‘till grim nature relenting, it again expands into the fair and placid stream as it was before making its final leap into the awful chasm higher up.

I followed for some considerable distance the various windings of the river and everywhere the land retained about the same level, the river gushing or gliding far down below, the banks being always precipitous, though varying in degree, here rising abrupt as a wall, there relenting in a degree towards a slope…The walking however was broken and difficult and moreover I suffered considerable pain from my boils, so I could not go as far as I wished, but as far as the eye could reach from different vantage points the same narrow torturous zigzag still confined the river in its grasp.

The journey back

Stabb, Wood and Schuch left the Falls on 9 September 1875 and did not cross to the northern side of the Zambesi: “I should have much liked to have stayed a fortnight and thoroughly explored the neighbourhood, but the season is late and we must hurry back lest the rains should come upon us, when we might be in a serious fix, as the two large rivers which we crossed on our way up, the Gwayi and the Bembesi, would then be impassable and to be caught in such a trap with failing ammunition and between 40 and 50 mouths to be filled is rather a serious consideration, to say nothing of the dangerous malaria we should also be exposed to.”

In passing through the villages towards Toulouse’s kraal and prior to crossing the Matetsi river Stabb says about the people: “They seemed to live entirely off the natural productions of the earth and have no knowledge of agriculture or farming and move about from place to place where berries, fruit and roots were to be found. Among nearly every party there were dogs, so I suppose we are now again out of the reach of that pest, the tsetse fly.”

10 September: Stabb says that one of Lobengula’s titles is “Inwalan Giralo” (literally letter writer) because he is the first to use writing as a means of communication, although of course he always used missionaries and traders to write on his behalf. Stabb’s carriers say that Lobengula is so impressed with this wonderful method of conveying his wishes and thoughts that he has issued most stringent orders protecting the letter carriers as they bear letters through his country and threatening serious penalties on anybody who interferes with them.

11 September: at Toulouse’s kraal he notices a headman who shows signs of leprosy: “They have I fancy, to thank the Portuguese for this introduction from civilization, as their traders come as far south as this…We saw several dogs here again, so I conclude we are still out of the tsetse-fly belt.”

13 September: They meet the 3 carriers that went to Pandamatenga: “They arrived the day before us and had brought a note from Bradshaw. Westbeech and Francis were away at Sesheke[xlix] and he wrote that he had no meal to send us, but had forwarded some tea, sugar, tobacco and pickles, also some Boer biscuits which Mrs Westbeech has made us and a box of biscuits from Mrs Francis, which the two latter articles were most acceptable as we have been some time without any farinaceous food and a diet of meat alone with coffee without sugar is getting slightly monotonous.”

15 September: “We passed a number of game pits during today’s march, indeed in some places we had to look out sharply for them as they are dangerous traps to fall into. The country must be full of Bushmen, but they never by any chance come across our path.”

By the 26 September they were back at Gubulawayo.

Stabb and Glascott with French, a hunter and trader hunted lions together for a week in early October. Then they sold all their horses except one each together with their guns and extra supplies to Fairbairn in exchange for ivory. Lobengula gave them a letter for Sir Henry Barkly requesting that the British Government either give or sell him a cannon and they took an ivory tusk each for Barkley and Sir Richard Southey, Colonial Secretary (1864-72) and then Lieutenant-Governor of Griqualand-West (1873-5)

They left Gubulawayo on 22 October using royal oxen which were exchanged when their own were brought up to the Umpakwe river they were at Tati by the 28 October. Here they bought more ivory from Alexander Brown and at the Shashe river met Henry Ogden and Cunningham. Ogden had built Thomson’s house at Hope Fountain in 1870; now they were taking two waggon loads of goods to Gubulawayo and Ogden had a gold ring for Lobengula from Thomas Baines who had died on 8 May 1875.

Journey back to Queenstown