Home >

Matabeleland North >

The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880

The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880

The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880

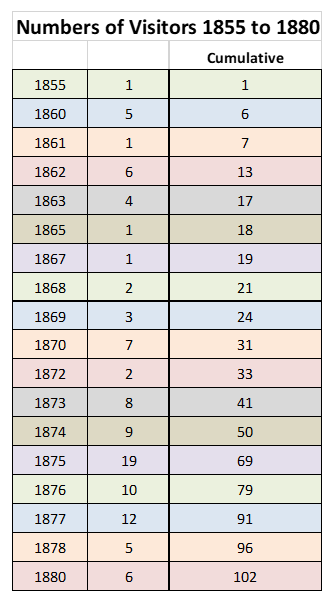

The list below contains the names of those that visited the Victoria Falls before the end of the 1880 cut-off date, the last six names are the party of Jesuit Fathers who attempted to establish a missionary base in Barotseland and were largely frustrated by the efforts of George Westbeech. They managed to establish a foothold with St Joseph’s Mission at Pandamatenga that lasted only five years. There was an even briefer Residence of the Holy Cross downstream from Wankie’s kraal on the Zambesi river by the same Jesuit Fathers that lasted just from August to September 1880 and resulted in the death of Father Terörde and serious illness of Father Vervenne from fever before it was abandoned.

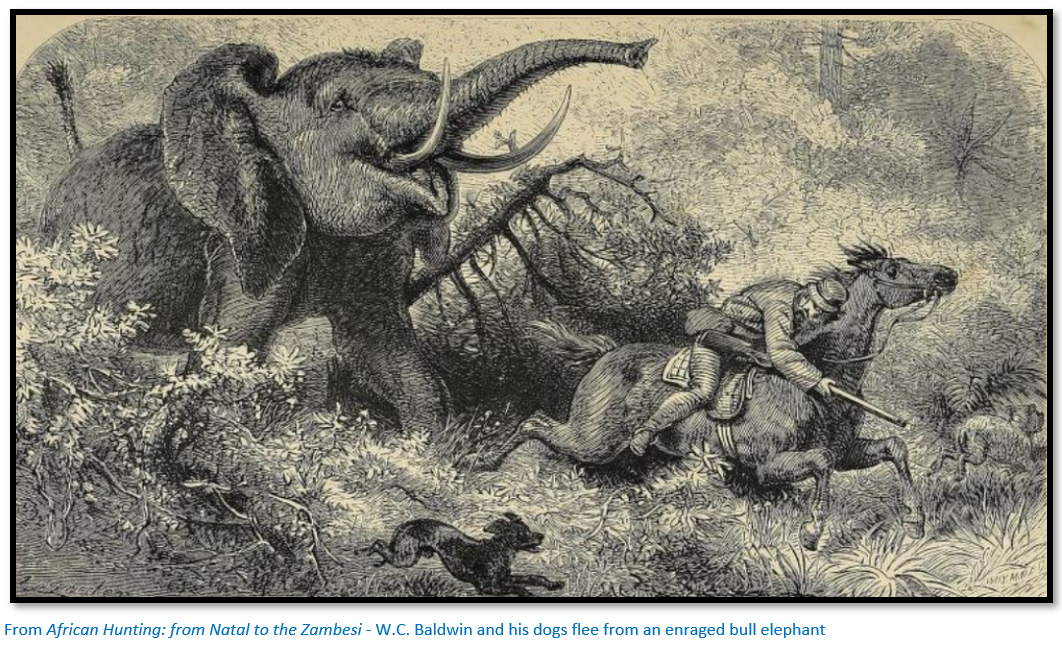

The year 1880 is not so arbitrary as prior to this date those who managed to make their way into the Far Interior were primarily hunters, traders, explorers, prospectors and missionaries. For many of the hunters and traders 1880 marked the end of an era as the elephant retreated into the tsetse-fly belts away from the Highveld that comprises roughly the region lying on either side of the central Matabeleland and Mashonaland watershed. Hunters could no longer shoot from horseback as horses are susceptible to the bite of the tsetse-fly which results in their death from nagana and hunting elephant on foot was a far more dangerous enterprise. Ivory was the most valuable commodity of the Far Interior and as the supply dwindled many of the Shoshong traders went out of business.

Those that followed post-1880 in the footsteps of these true pioneers were in broad terms concession hunters and political agents and then those adventurers of the 1890 Pioneer Column who saw personal opportunities for both adventure and wealth, although the new desired commodities were gold and land. Some of course, such as Fred Selous, James Gifford and Frank Mandy were active both before and after 1880.

There will be names I have left off inadvertently; please send me as much details on any additional visitors you believe should be added ensuring that they visited the Falls before the end of 1880.

Discovery of the Victoria Falls

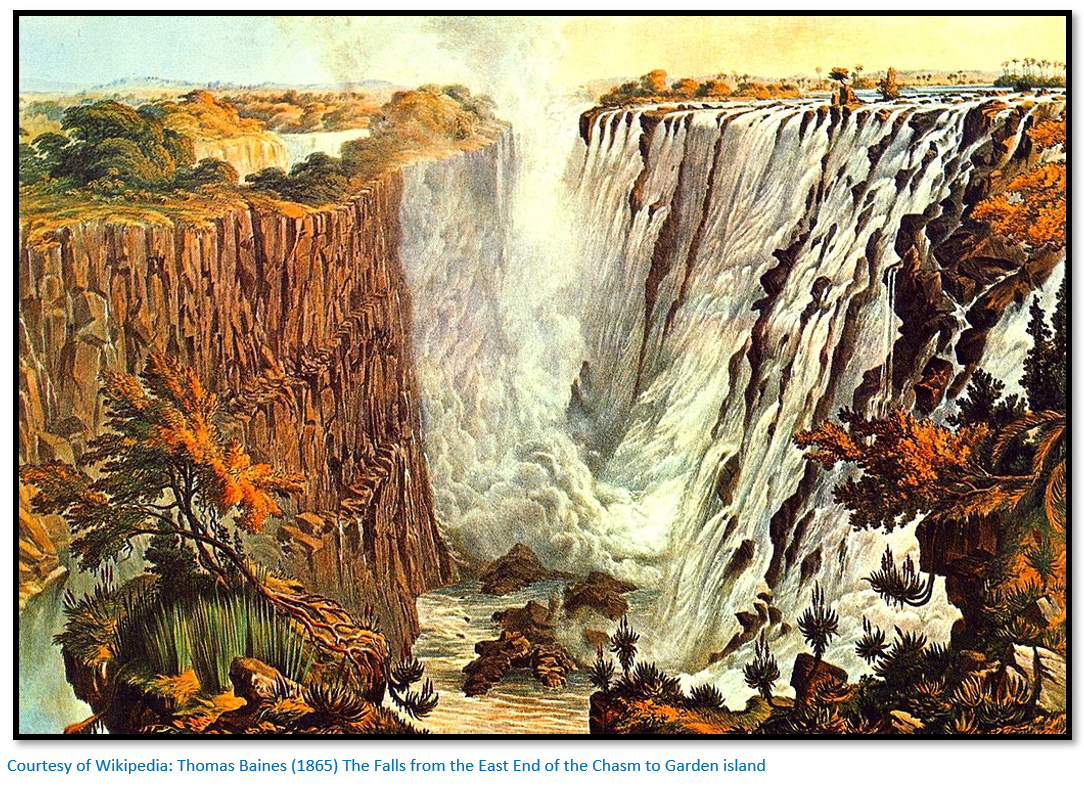

Most sources attribute David Livingstone as the first European to reach Victoria Falls on the present-day border between Zambia and Zimbabwe on 16 November 1855. However local people knew of the existence of the Falls long before. The actual date when Livingstone first saw the Falls was only established in 1955 when a Mr PCG Adams found an entry in one of the small notebooks used by Livingstone for making daily notes and from which he wrote up his journal once or twice a week that read: “Musioatunya bears SSE from Sekota islet after 20 minutes sail thence on 16th November 1855, saw three or five columns of vapour rising 100 or more feet.”[i]

William Baldwin was the second visitor on 2 August 1860 and records in his book African Hunting from Natal to the Zambesi that: “The discovery of the Falls was made in 1855 and from that time to this (1860) with the exception of Livingstone’s party no European but myself has found his way thither.” Baldwin used a pocket compass to find his way from the Shua river and the Chobe and returned to Natal and England in 1861 through Shoshong. He caused great offence to the local chief by jumping into the Zambesi from the canoe and swimming ashore to the north bank. The chief said he would have to remain until as Baldwin writes: “I had paid him for the water I drank and washed in, the wood that I had burned, the grass that my horses ate and it was a great offence that I had taken a plunge into the river on coming out of one of his punts; if I had been drowned or devoured by a crocodile or sea-cow, Sekeletu would have blamed him and had I lost my footing and fallen down the Falls, my nation would have said the Makololo had killed me; and altogether I had given him great uneasiness!”

Livingstone, his brother Charles and Dr John Kirk arrived the following week and persuaded the local chief to let Baldwin leave, which he did on 10 August 1860 with Livingstone and his party leaving for Linyati on 12 August.

Pre-European Visitors to the Victoria Falls

Early and Middle Stone Age

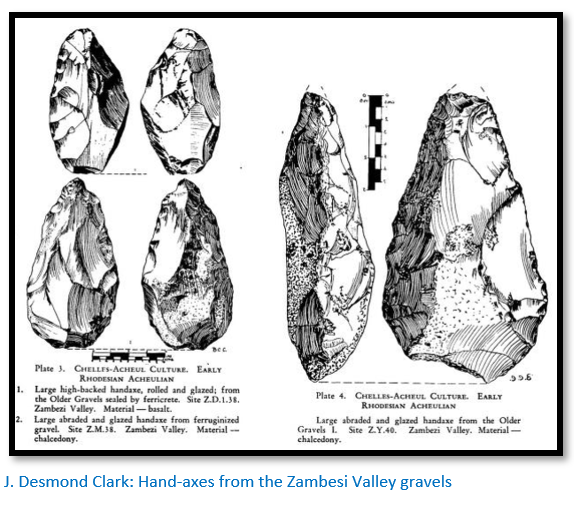

Both Early (500,000 to 50,000 years Before Present) and Middle (35,000 to 10,000 years Before Present) Stone Age tools such as hand-axes, choppers, bored stones, picks and scrapers have been excavated from river gravels at sites on both sides of the Zambesi and also within the boundary of Victoria Falls National Park. The best assemblages of tools were found on the north bank in the vicinity of Livingstone town[ii] and are often manufactured from quartz, agate and chalcedony pebbles which were available locally and did not need to be imported over long distances.

Clark states: “…it becomes apparent that Acheulian man was in complete control of his raw materials. He could produce a hand-axe in quartz, quartzite or lava which was just as beautiful and efficient as that he could make from chert or chalcedony. His cleavers in the Zambesi Valley are just as well made as his hand-axes.”[iii]

San Khoisan hunter-gatherers

The San Khoisan people inhabited much of Southern and South-Eastern Africa prior to the arrival of the Bantu people approximately 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. Among the artefacts excavated from this largely transient society that hunted small antelope, insects and grubs and gathered honey, edible fruits and roots are microlithic stone tools, ostrich beads and bored stones which were used for digging up underground roots and tubers. Many of their stone tools are quite small and were hafted together to form arrows, a knife or adze. It is unlikely that the San occupied permanent sites as they probably mirrored the seasonal movement of animals through the region. They made no pottery and used ostrich eggshells and calabashes for carrying water.[iv] Catching fish in reed baskets and weirs or with wooden spears in the Zambesi river may have formed a useful food supplement to their diet.

Their chief hunting weapon was the bow and arrow with the points often poisoned and a natural mastic used to keep the points in position. Thumb-nail scrapers were used as adze blades for shaping wood and bark vessels and for trimming bows and arrows. These were the people in possession of the Zambesi Valley when the first agricultural people with cattle and goats came down from the north.

Iron Age

People who made iron-age pottery first entered the Victoria Falls region around 2,000 to 1,500 years Before Present and the pottery found on surface collections as well as excavations resembles much of what is typically found in the region including Malawi, Botswana, Zimbabwe and the Limpopo province of South Africa; commonly called ‘Gokomere’ culture.[v] Their culture was much more complex than that of the San Khoisan hunter-gatherers which preceded it although they may have existed side-by-side for some period of time. There is evidence of both agriculture and cattle and goat herding within a settled village-life and an extended tribal and social community. There is also evidence of smelting and working of both iron and copper.

By 1,000 years Before Present the village population of the Victoria Falls region had grown quite substantially particularly on the northern side of the Zambesi which lends itself better to agriculture and where large assemblages of pottery have been found at excavated sites. Both the basic technologies and the material cultures practiced were much the same over the local area with wider regional differences. Iron tools manufactured included hoes, knives, spears and arrowheads were produced in open-bowl smelter sites. Bones were worked into awls, points and hair ornaments. Ivory was worked into bracelets. Copper was worked into bracelets and currency bars made by pouring copper into sand moulds; they were traded over much wider distances and cowrie shells were clearly obtained from the east coast.

Larger communities were required to both look after herds of cattle and carry out crop farming which relied upon the summer rains. Dambos are a natural feature particularly prevalent in Zambia and very often take the form of wetlands on flat plateau which form the headwaters of streams and rivers.[vi] In Mashonaland they are called matoro and Wikipedia lists them as providing the following vital resources to local people:

- as a dry-season water source

- for rushes used as thatching

- for clay used for building and pottery

- for hunting (especially birds and small antelope)

- for growing vegetables (pumpkin, groundnuts, leafy vegetables) and other food crops such as groundnuts, sorghum and millet which can be vital in drought years since dambo soils usually retain enough moisture to produce a harvest when the rains fail

- for fshing (generally using fish traps) in those dambos with streams and rivers

It was women's work to tend the fields. Men helped them to clear the ground using tools like the hoe. Later Europeans would introduce the ox-plough, which made the work easier, but as the plough had to be pulled by oxen and women were not allowed to handle cattle this meant men would take over that job.

Their huts were pole and dhaka often built on a mound with a central cattle kraal and a thorn fence to keep out lions from their domestic stock. Grain was stored in bins built on circles of stones. The arrival of waves of immigrants pushing down from the north-west seem to have disturbed the Tonga people who had lived here in peace for a considerable period and before the Europeans arrived they had been subjected to raids from the Makololo, the Lozi and then the amaNdebele.

The Makololo seem to have been the first to impose a loose sovereignty over the Tonga who paid them tribute. The Makololo were then deposed by the Lozi in 1864 – 6 and the Tonga were left to restore their cattle herds until warfare resumed in 1880 in the form of Lozi cattle raids. These were followed by amaNdebele raids in 1882, 1888 and 1889-90 when: “they overran the [Tonga] villages, taking what they would, burning huts and galleries, killing whoever resisted and moving on with their spoils of cattle and slaves – usually women and small children.” [vii]

These Iron Age people left lasting legacies in their names for the Victoria Falls. The southern Tonga people known as the Batoka called the Falls ‘Shungu na mutitima.’ The Batswana and Makololo whose language is used by the Lozi people who call the Falls ‘Mosi-o-Tunya.’ The amaNdebele, who came later as raiders making short, violent and transient visits named them ‘aManz' aThunqayo.’ All these names portray essentially the same linguistic image: "the smoke that thunders."

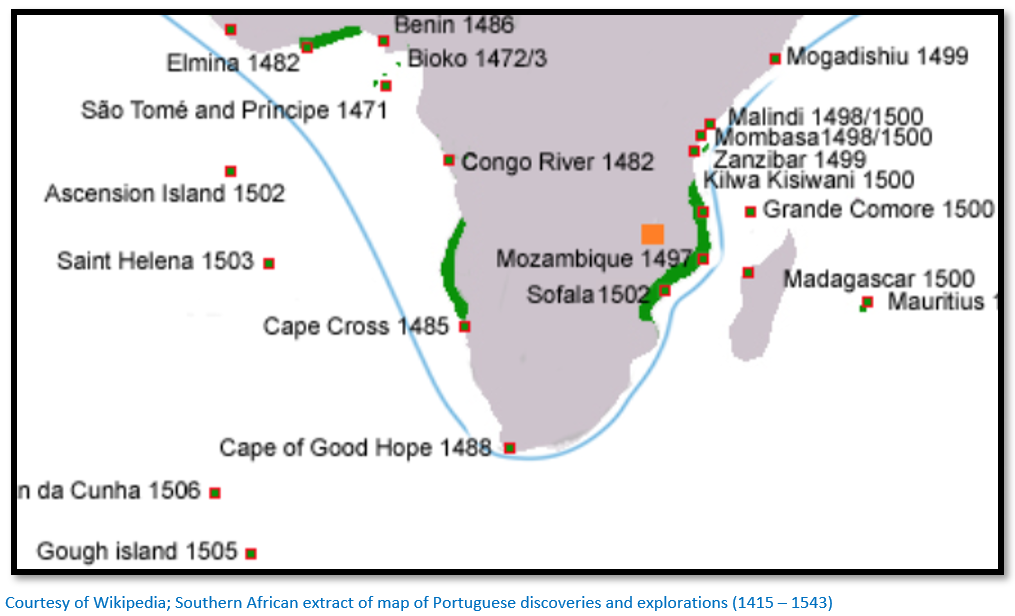

Early Portuguese exploration in Africa

To the early Portuguese explorers who were sent in fleets each year after 1500 for a route to the spices of the East Indies, Africa was just an obstacle in their quest for the riches of Asia and their main goal was to circumnavigate around the continent.[viii]

Initial Portuguese interest concentrated on the West coast of Africa which could supply the labour needs of the Sao Tome sugar planters and the transatlantic slave trade and their influence was much more dramatic and destructive than on the east coast. Throughout much of the 16th century, for example, over 15,000 Africans from the Kongo Kingdom were enslaved and engulfed in the brutal trade every year. In 1526, King Afonso of the Kongo, converted to Christianity by Portuguese missionaries, wrote to the King of Portugal, to protest the trade: “Each day the traders are kidnapping our people—children of this country, sons of our nobles and vassals, even people of our own family . . . This corruption and depravity are so widespread that our land is entirely depopulated . . . .We need in this kingdom only priests and schoolteachers, and no merchandise, unless it is wine and flour for Mass . . . It is our wish that this kingdom is not a place for the trade or transport of slaves”[ix]

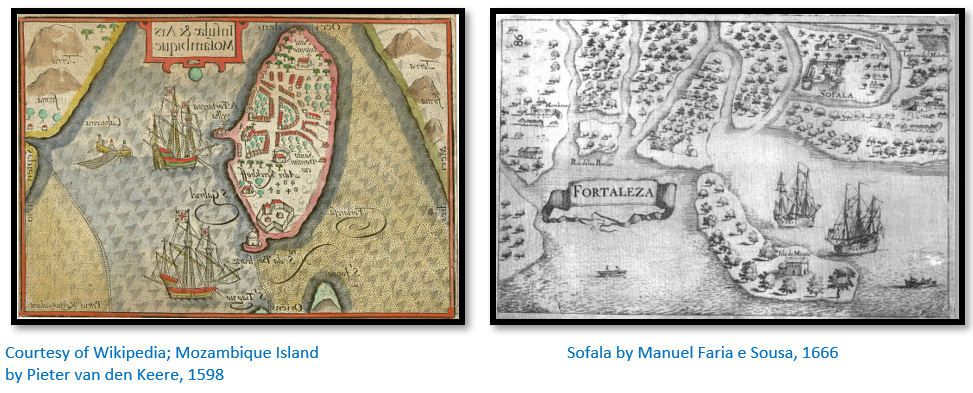

The Portuguese established forts and trading posts between 1497 - 1510 along the east coast of Africa at former African, Arab and Muslim trading posts where Swahili was the lingua franca including Mozambique Island, Kilwa, Mombasa, Malindi and Barawa which were destroyed, or became either subjects, or allies of Portugal. The Portuguese needed bases for their ships to resupply, land the sick and fresh crew before crossing the Indian Ocean. The ships bound for India would ‘winter’ in these ports, sometimes for a long as six months, waiting for the monsoon winds to start blowing to the east.

Portuguese exploration from Mozambique up the Zambezi river

Although the initial reason for bases at Mozambique and Sofala had been as key ports of call for ships on the way to India they also knew that gold mined in the interior was brought to these coastal ports by Swahili merchants and hoped that by controlling the gold trade the precious commodity could be used to buy spices in the east. Although the situation further up the coast was always fractious between the Portuguese and the Muslim population, in Mozambique the two communities were able to rub along apart from one violent period in 1575 explained below.

At first the fortress captains were salaried royal officials, but gradually the system changed so that the captaincy of Mozambique was purchased from the Portuguese Crown for a substantial amount in return for being granted a three year commercial monopoly. The captain took responsibility for maintaining the forts at Mocambique Island and Sofala and appointed captains who regulated the gold and ivory trade through the regional centres at Sena, Tete, Zumbo and Quelimane, all Swahili trade centres before the Portuguese colonial era.

Once the Portuguese were established at the coast they gradually began to travel inland to trade concentrating their efforts on the Zambesi valley. Sena had been a Muslim village along the Zambesi until Vicente Pegado founded a fair in 1531 and grew gradually to become a major trading post, missionary centre, colonial era garrison and market town. Tete is 420 kms up the Zambesi from the sea and the Portuguese hoped it would provide access through feiras, or marketplaces, to the gold and ivory of the Mutapa State. Zumbo, the most westerly of the trading posts became prosperous in the eighteenth century as it traded along the middle Zambezi and up the lower Luangwa Valley, mostly for ivory, but also gold from the Mutapa State.

The first Portuguese made their way into the interior as sertanejos (backwoodsmen) and lived alongside the existing Swahili merchants. One sertanejo, António Fernandes was the first European who managed to travel extensively throughout the region and in two journeys between 1512 and 1516 he visited the Mwene Mutapa, the ruler of the Mutapa State in the Mavuradonha wilderness area and the Msengezi river, then turned south to the Hunyani, now Manyame river and the site of Hartley, now Chegutu and returned to Sofala. On his second journey he reached Kwekwe before heading back across the Tokwe, Lundi, now Runde and Save rivers and followed the Busi river almost to Sofala. He found much evidence of gold-mining by local people during the winter season when they were not engaged in agricultural activities.

Despite his success, no immediate use of his knowledge was used by the Portuguese who preferred to use the unhealthy Zambesi valley for inland journeys.

Fernandes was followed by Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. (1522 – 1561) a Portuguese Jesuit missionary who made his way up the Zambesi river arriving at the Mwene Mutapa’s court on 26 December 1560 and managed to convert and baptise the ruler and a number of his subjects to Christianity. The Swahili merchants at court were fearful of his influence and agitated against him before he was strangled in his hut by order of the ruler and his body thrown into the Msengezi river.

This action demanded retaliation from the Portuguese who planned to penetrate the interior by force and take control of the gold mines in the hope that they would find gold in quantity such as the Spanish had found in the America’s. After lengthy preparations an expedition of 1,000 men under Francisco Barreto was launched in 1568 and sailed up the Zambesi armed with weapons and mining tools and arrived at Sena in December 1571. They fought several battles against the Mongas whose territory lay between the Portuguese and the mines of Manica; their muskets winning them initial victories despite being faced by much larger numbers.

But before the expedition could progress further Barreto had to return to Mozambique Island to deal with the commander, António Pereira Brandão, who was spreading false information about Barreto. After removing him from his post as commander of the São Sebastião fort, Barreto returned to Sena where many of his men had become sick with malaria and where Barreto himself became ill and died on 9 July 1573.

Barreto's deputy governor, Vasco Fernandes Homem, succeeded him and returned with the remaining army to the coast and the expedition to Manica was resumed via the Sofala route. The Manica mines were found to be producing only very small quantities of gold and Homem abandoned the expedition with the Portuguese returning to their base in 1575 and taking their frustrations out on the Swahili merchants at Mozambique Island who were massacred.

Portuguese rule on the Zambesi

Malyn Newitt[x] writes that local kingdoms established themselves north of the Zambesi – the Lundi, Undi and Kalonga; the Portuguese grouped them together as the Maravi and they controlled the whole region from the Luangwa Valley to the coast opposite Mozambique Island. Trade here in the seventeenth century was conducted directly through the rulers or at central markets, but by the eighteenth century their power had weakened allowing Portuguese traders from the Zambesi valley to circumvent the old customs as the old rulers were replaced by local warlords.

To the south of the Zambesi on the Zimbabwean plateau a series of separate Karanga states existed including:

- Mutapa State – on the plateau adjacent to the Zambesi

- Sedanda – between Sofala and the mouth of the Save river

- Quiteve – inland of Sofala

- Manica – the mountainous border area of today’s Zimbabwe and Mozambique

- Barue – a district in present-day Mozambique adjacent to Nyanga

- Butua – in the southwest of Zimbabwe centred at Khami

The former Swahili traders were partially replaced by the Portuguese who married local women and with their half-African progeny became prazeiros (estate holders) of the lower Zambezi often adopting local life-styles and using local trade networks. Feiras were established inland within the Karanga states close to the known gold-producing areas and trade caravans took textiles, beads, metalwork and porcelain which were exchanged for gold.

In the seventeenth century the Portuguese became increasingly active in local politics establishing permanent bases with fortified storehouses and churches at the feiras. They exploited dynastic succession disputes between the Karanga rulers to weaken their control, but towards the end of the seventeenth century a new force arose in the state of Butua called the Rozvi who defeated both the Portuguese, expelling them from the plateau, and the Mwene Mutapa whose land was reduced to Dande and Chedimu north of the plateau and south of the Zambesi. This established the current boundary between Zimbabwe and Mozambique.

From this most historians conclude that it is unlikely that the Swahili merchants who traded down the coast and up the Zambesi and with the Mutapa State ever visited the Falls; however their trade goods in all probability found their way to the area through local middlemen, although it’s possible that slave traders might have penetrated up into the middle Zambesi. No written accounts survive of such journeys though.

Although the Portuguese established forts in Mozambique by the 17th century and explored large areas of the lower Zambezi, there is no record of Victoria Falls being known to the outside world until the middle of the 19th century. There are falls are marked on a number of maps of the seventeenth century, but these were used to fill in the blank spaces and not based on actual knowledge.

European Explorers of the region

Livingstone might have been challenged for the prize of being first by other explorers if the fickle finger of fate had not played its part.

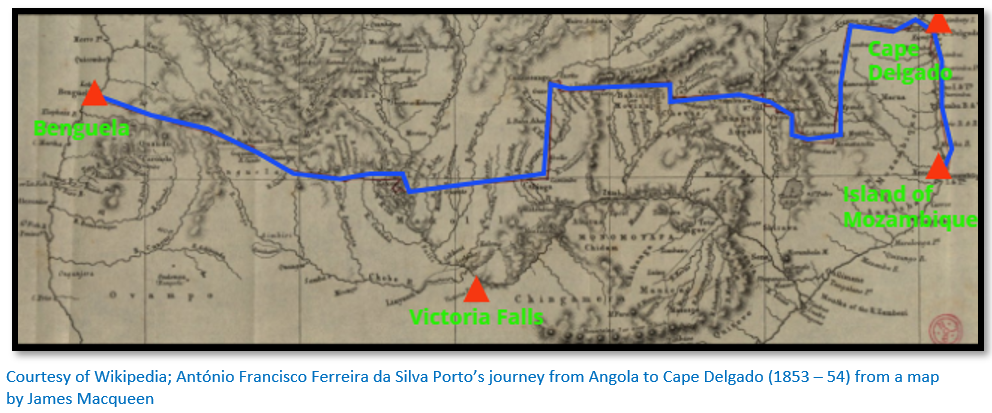

António Francisco Ferreira da Silva Porto (1817 – 1890) a Portuguese merchant and explorer made an epic journey from west to east across the continent from Benguela in Angola to Cape Delgado and Mozambique Island in 1853 – 54 when Portuguese interest in the interior revived. The detailed content of his wanderings were lost when his diaries were burned in the great fire of Lisbon, however the map of his journey below shows that he walked north of the Victoria Falls a year or two before David Livingstone but did not visit the Falls themselves.

James Chapman (1831–72) was another who might have been the first to discover the Victoria Falls. In 1849 he established a store in Potchefstroom and by 1852 was trading across the Limpopo river in BamaNgwato territory. Khama III (1837–1923) son of Sekgoma the Kgosi (Chief) of the Bangwato people, became a friend and gave Chapman permission to trade in the Chobe river region. In 1853 he had explored and hunted elephant with Francis Thompson and Donald Campbell down the Chobe river and 23 August they were camped on the Chobe at Mimili’s kraal. They did not see David Livingstone although they delivered supplies sent by Robert Moffat from Kuruman and Chapman and Livingstone exchanged letters. Chapman had heard of the Falls and tried to recruit boatmen to take him down the river, but they refused to go because the amaNdebele were raiding to the south along the Zambesi and they were afraid. Thus James Chapman failed to discover the Victoria Falls although it is only 75 kms from the confluence of the Chobe river at Impalera Island with the Zambesi river to the Victoria Falls. Chapman himself wrote: “Could I but have known of the magnificent sight I lost in August 1853 after being very near it and how nearly I had forestalled Dr Livingstone’s discovery, I should certainly have made another effort at that time to accomplish the object.”[xi]

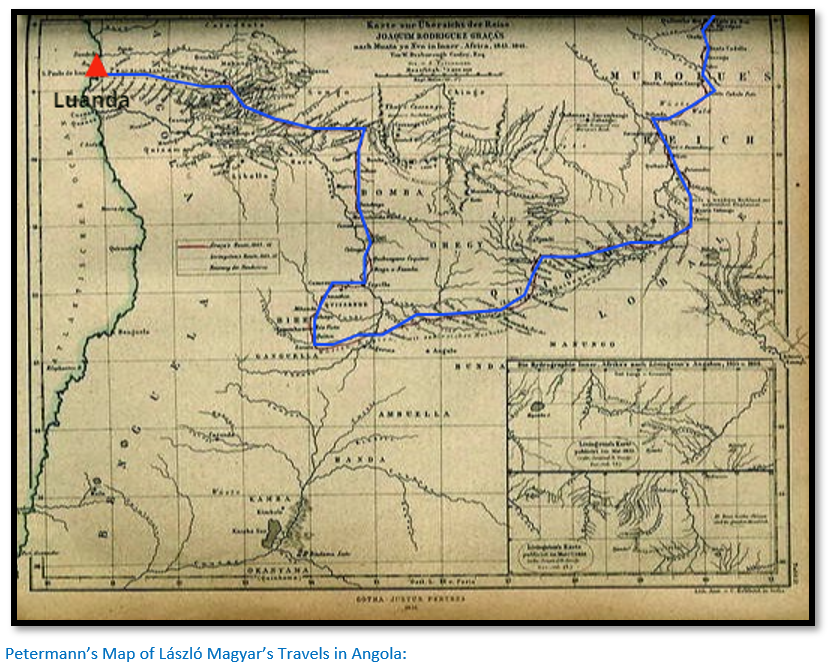

László Magyar (1814-64) was a Hungarian explorer and naval officer who lived for 17 years in Angola and made his first African expedition a voyage up the Congo River in 1846. He married a daughter of the King of Bié and used his family connections to gain access to the interior making in all six voyages to the sources of the Congo and Zambezi rivers, regions at that time still very difficult for Europeans to visit. He wrote three volumes of geographical and ethnographic observations, with a focus on the Kimbundu people of present-day Angola. One volume was published in Hungary, but the manuscripts of the other two volumes, along with Magyar’s journals, were lost in a warehouse fire after his death.

Magyar would remain at one location for a long time and studied African societies recording local ethnographical details. The African people called him "Mister What-Is-This" because he was always putting questions to them. His main interest was the local people, their habits and their societies and he was an excellent observer with very good drawing skills. He lived in Bié for several years, stayed in the kingdom of Mwata Yamwo over a year and spent nine months travelling along and between the Cunene and the Rio Cubango, the Portuguese name for the Okavango and on the headwaters of the Zambesi river.

Unfortunately Magyar lacked experience in using a sextant and so his position determinations were faulty and he tended to overestimate distances. At the time most geographers made estimates of distances based on the time spent marching. However unlike Livingstone, who travelled with just a few men, Magyar had several hundred men on his expeditions so they tended to move slowly and at an unsteady pace and were delayed by natural obstacles as well as by its ill-disciplined members and therefore he had to stop for days which made the estimation of the daily average distance very difficult if not impossible to calculate accurately.

Consequently his maps are distorted and August Petermann, the German cartographer, had to redraw Magyar's maps before they could be published. Although he traced the headwaters of the Okavango and Zambesi his exploration tended to the north of Angola rather than to the south and therefore it is unlikely that he heard about the Victoria Falls.

William Cotton Oswell (1818–1893) was an English sportsmen and explorer and great friend and supporter of David Livingstone. Educated at Rugby School, he joined the East India Company and after passing out head of his year started for Madras in 1837 and during his ten years' residence in Madras studied surgery and medicine and won fame as an elephant-catcher and for his talent with languages including Tamil and several native Indian dialects whilst serving as head assistant collector at the Madras Presidency.[xii]

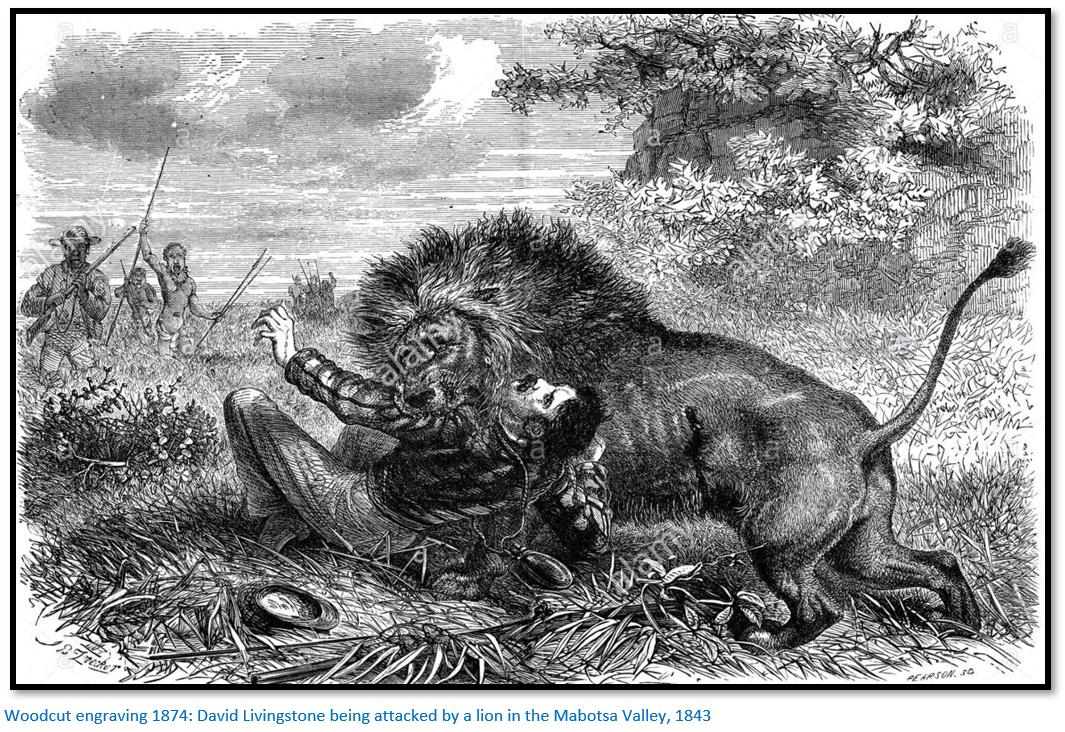

Several bad attacks of fever resulted in his transfer to South Africa in September 1844. He made his first hunting trip into the interior with Mungo Murray and at Kuruman was directed by Robert Moffat to the London Missionary Society (LMS) mission at Ga-Mabotsa, near current day Polokwane, which was the beginning of Oswell’s lifelong friendship with Livingstone.

Oswell and Murray hunted as far as the Limpopo and BamaNgwato country returning to Cape Town in December 1845 to outfit for another inland journey. He took two ox-wagons from Grahamstown and was at the Marico river by June 1846 where he hunted with Captain Frank Vardon. He was injured by a black rhino on this trip before returning on the missionaries road to Cape Town and went to India and England.

In 1849 Livingstone decided to investigate rumours of a great lake in the Kalahari; Oswell and his friend Mungo Murray returned to South Africa to take part in the exploration with Oswell undertaking to pay the guides’ expenses. Five wagons set off avoiding Shoshong and Sekhomi and with Kwena guides they reached the Botletle river on 4 July and Lake Ngami on 1 August 1849. Although Lechulatebe refused guides to the Makololo and onwards the expedition resulted in the discovery of Lake Ngami, and the important practical demonstration that the Kalahari could be crossed by oxen and wagons. Livingstone acknowledged his debt to Oswell who looked after the wagons and supplied the party with food. The kuabaoba, or straight-horned rhinoceros, was named Oswellii after Oswell, who also received the Paris Geographical Society's medal.

Oswell and Livingstone hoped to go to Lake Ngami and Makololand in 1850 and they arranged to meet at Kolobeng, Livingstone’s third and final mission. But a drought started in 1849 and the Bakwena people blamed it on Livingstone’s presence which prompted him to leave and when Oswell arrived he found that Livingstone and Sechele I, the kgosi (chief) had left for the interior. So Oswell travelled to the Botletle where he shot over 30 bull elephants and met Livingstone’s party on their return.

Livingstone was determined to reach the Makololo and Oswell gave him supplies, oxen and a new wagon at Kolobeng mission to enable Livingstone to make the journey. Oswell started ahead in April 1851 to clear the waterholes and the parties joined up and were at Shoshong on 8 May. At Chapo’s on the Ngami road they obtained guides crossing the Ntwetwe Pan and reaching the Chobe river near Linyati on 19 June where they remained for two months. Chief Sebitwane died on 7 July and Oswell and Livingstone rode over 160 kms to Old Sesheke and reached the upper Zambesi river at Mwandi on 4 August 1851.

Local BamaNgwato hunting elephant in these northern regions and returning to their homes in the 1840’s had told tales from river boatmen of a mighty Falls with ravines that gave off smoke.[xiii] These oral accounts were confirmed by Oswell and Livingstone when local natives talked about the Falls which lay downstream and Oswell marked the approximate position on a manuscript map which was not seen again for 50 years: “waterfall, spray seen ten miles off.”[xiv]

They left the Chobe on 12 August 1851 and reached Kolobeng mission by 27 November where Oswell stayed before leaving for England in February 1852. Although he never returned to Africa he served and gave good service in the Crimean War both in the trenches and in the hospitals and later travelled through North and South America.

Livingstone wrote that Oswell had more hairbreadth escapes than any man living, although he never wrote an account of his hunting; it is known that he was twice tossed by rhinoceros. A fine rider and shot he always got as close to elephant as he could on foot and without dogs.

David Livingstone – journey to Makololo country and Barotseland

Much of Livingstone’s earlier trips are described under the William Oswell entry above and the story picks up on Livingstone’s trip from Kolobeng in 1850 when Oswell arrived to find Livingstone had already left in April with Samuel Edwards (1827–1922) and J.H. Wilson, Livingstone’s long-suffering wife, Mary, their three children and chief Sechele who wished to visit Chief Sebitwane of the Makololo. The party travelled through Shoshong and went on to Lake Ngami by the usual route on the south bank of the Botletle river. Livingstone planned to cross the Botletle and follow its north bank to its confluence with the Thamalakane and then follow that river north toward Makololo country.

But local people told Livingstone of a tsetse-fly belt which would kill his oxen so he re-crossed to the south bank of the Botletle and went to Lechulatebe’s kraal at Lake Ngami where he planned to leave his family before going on to the Makololo country. At the lake he found three Englishmen very ill with fever; Harris, Stephenson and Ryder, the last of whom subsequently died. Edwards and Wilson also caught fever as well as his children and as his wife was pregnant so Livingstone abandoned his journey to the Makololo and returned to Kolobeng meeting Oswell on the trip home.

The trip to the Makololo in 1851 is described under Oswell when they reached Makololo country and heard first-hand accounts of the Falls on the Zambesi.

Livingstone realised that the Chobe river was too feverish to take his family and in March 1852 took his family to Cape Town and sent them to England to improve his wife’s health and for the children to begin school. He would go alone to the Makololo country and look for a higher and more healthy site for a mission and cut a road to the east or west coast as the roads from the south were too long and costly.

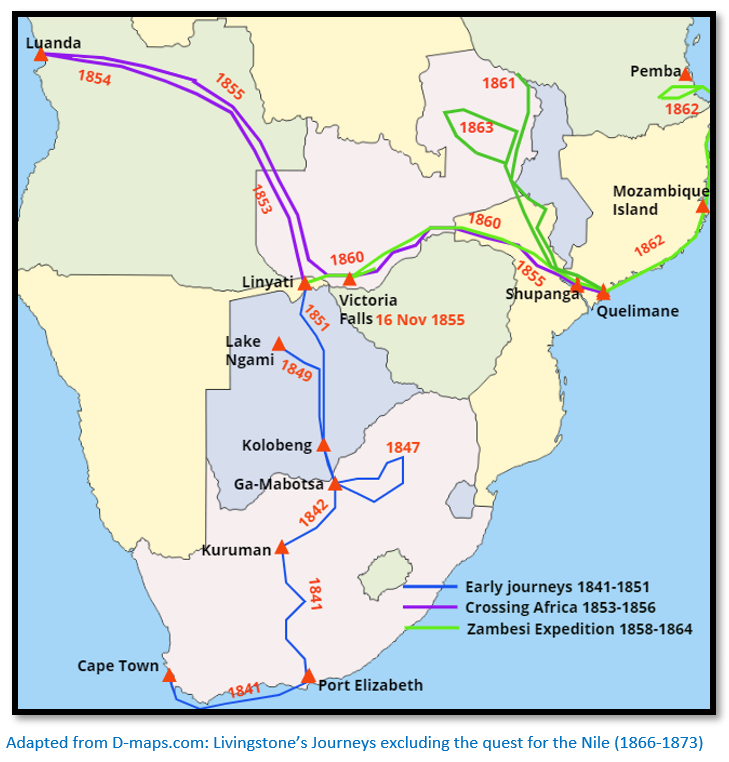

Livingstone and George Fleming, a former slave from the West Indies who had been Oswell’s cook, left Cape Town on 8 June 1852 reaching Kuruman in early August where they were detained by Boer raids on Sechele and Kolobeng until mid-December. They detoured around Kolobeng to avoid the Boers and reached Sechele’s town on 31 December 1852. They trekked through Shoshong and had reached the Makgadikgadi salt pans in February and Linyati on 23 May. Livingstone was exploring Barotseland in today’s north-western Zambia from May to mid-September 1853.

Livingstone’s major journeys until his return to England were

Linyati to Luanda – 11 November 1853 to 31 May 1854

Luanda to Linyati – 24 September 1854 to 11 September 1855

Linyati to Quelimane – 3 November 1855 to 26 May 1856 during which journey he discovered the Victoria Falls on 16 November 1855 and the Kafue river the next month.

David Livingstone – discovery of the Victoria Falls in 1855

Once again on the upper Zambezi, as before, Livingstone heard tales of the great waterfall of Mosi-oa-Tunya, that natives called "smoke that thunders" and on November 3, 1855, he set out to visit them along with Chief Sekeletu of the Makololo and 200 of his tribe. After leaving Old Shesheke they were forced to portage around the Katambora rapids and two days later reached Kalai Island where he saw where Chief Sekute was buried in a grave surrounded by a fence of 70 large elephant tusks.

They stayed the night on the island; Sekeletu had intended to accompany Livingstone, but as only one canoe could be found he stayed behind and soon after from the canoe they could see the columns of spray and hear the thunderous roar of water miles away at the Falls. About one kilometre upstream of the Falls Livingstone transferred to a smaller, lighter canoe and proceeded in this to the island between the Main and Rainbow Falls[xv] which is today called Livingstone Island. Landing there he obtained his first view of the Falls from what is surely the most impressive of all viewpoints. The following description is in Livingstone’s own words:[xvi]

"After twenty minutes' sail from Kalai we came in sight, for the first time, of the columns of vapor appropriately called 'smoke,' rising at a distance of five or six miles, exactly as when large tracts of grass are burned in Africa. Five columns now arose, and, bending in the direction of the wind, they seemed placed against a low ridge covered with trees; the tops of the columns at this distance appeared to mingle with the clouds. They were white below, and higher up became dark, so as to simulate smoke very closely. The whole scene was extremely beautiful; the banks and islands dotted over the river are adorned with sylvan vegetation of great variety of colour and form…no one can imagine the beauty of the view from anything witnessed in England. It had never been seen before by European eyes; but scenes so lovely must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight. The only want felt is that of mountains in the background. The falls are bounded on three sides by ridges 300 or 400 feet in height, which are covered with forest, with the red soil appearing among the trees.

When about half a mile from the falls, I left the canoe by which we had come down thus far, and embarked in a lighter one, with men well acquainted with the rapids, who, by passing down the centre of the stream in the eddies and still places caused by many jutting rocks, brought me to an island situated in the middle of the river, and on the edge of the lip over which the water rolls. In coming hither there was danger of being swept down by the streams which rushed along on each side of the island; but the river was now low, and we sailed where it is totally impossible to go when the water is high. But, though we had reached the island, and were within a few yards of the spot, a view from which would solve the whole problem, I believe that no one could perceive where the vast body of water went; it seemed to lose itself in the earth, the opposite lip of the fissure into which it disappeared being only 80 feet distant.

At least I did not comprehend it until, creeping with awe to the verge, I peered down into a large rent which had been made from bank to bank of the broad Zambesi, and saw that a stream of a thousand yards broad leaped down a hundred feet, and then became suddenly compressed into a space of fifteen or twenty yards.[xvii] The entire falls are simply a crack made in a hard basaltic rock from the right to the left bank of the Zambesi, and then prolonged from the left bank away through thirty or forty miles of hills. If one imagines the Thames filled with low, tree-covered hills immediately beyond the tunnel, extending as far as Gravesend, the bed of black basaltic rock instead of London mud, and a fissure made therein from one end of the tunnel to the other down through the keystones of the arch, and prolonged from the left end of the tunnel through thirty miles of hills, the pathway being 100 feet down from the bed of the river instead of what it is, with the lips of the fissure from 80 to 100 feet apart, then fancy the Thames leaping bodily into the gulf, and forced there to change its direction, and flow from the right to the left bank, and then rush boiling and roaring through the hills, he may have some idea of what takes place at this, the most wonderful sight I had witnessed in Africa.

In looking down into the fissure on the right of the island, one sees nothing but a dense white cloud, which, at the time we visited the spot, bad two bright rainbows on it. From this cloud rushed up a great jet of vapor exactly like steam, and it mounted 200 or 300 feet high; there condensing, it changed its hue to that of dark smoke, and came back in a constant shower, which soon wetted us to the skin…On the left of the island we see the water at the bottom, a white rolling mass moving away to the prolongation of the fissure, which branches off near the left bank of the river… The walls of this gigantic crack are perpendicular and composed of one homogeneous mass of rock. The edge of that side over which the water falls is worn off two or three feet, and pieces have fallen away, so as to give it some- what of a serrated appearance. That over which the water does not fall is quite straight, except at the left corner, where a rent appears, and a piece seems inclined to fall off upon the whole, it is nearly in the state in which it was left at the period of its formation…On the left side of the island we have a good view of the mass of water which causes one of the columns of vapor to ascend, as it leaps quite clear of the rock, and forms a thick unbroken fleece all the way to the bottom. Its whiteness gave the idea of snow, a sight I had not seen for many a day. As it broke into (if I may use the term) pieces of water, all rushing on in the same direction, each gave off several rays of foam, exactly as bits of steel, when burned in oxygen gas, give off rays of sparks. The snow-white sheet seemed like myriads of small comets rushing on in one direction, each of which left behind its nucleus rays of foam."

In the evening Livingstone went back upstream by canoe to Kalai Island and returned the following day with Chief Sekeletu when he planted peach and apricot stones on Garden island, now Livingstone island and carved his name on a tree…clearly he was so full of wonder at the spectacle that for once he indulged “in this piece of vanity.” He lay over the edge of the chasm – the waters were low in mid-November before the onset of the rains – and lowered a string weighted with some lead bullets in a handkerchief to establish the depth. It stuck on a ledge some way off the bottom when the string measured 295 feet (90 metres)

Livingstone’s journey continued down the Zambesi river, this journey will be the subject of another article, until he finally reached Quelimane on the Indian Ocean in May 1856.

William Baldwin and George Polson visit the Victoria Falls in 1860

Following Livingstone's first visit there was a gap of almost five years before any Europeans arrived to visit the Falls. They were William Baldwin and George Polson who arrived together on 3 August 1860 just before the arrival on 8 - 9 August of the Livingstone brothers, David and Charles and Dr John Kirk. Baldwin and Polson were both hunters and traders (i.e. they hunted elephant and sold the ivory) and whilst this was Polson’s first trip into the interior, Baldwin had spent much of the decade from 1851 wandering widely between Natal and the Zambezi and he found their way to the Falls, via the Chobe River, by pocket compass. Baldwin made the first reasonably accurate estimate of the size of the Falls; he considered them to be two thousand yards wide (1,800 metres) and three hundred feet high (91 metres) For eye-estimates these are remarkably close to the true figures and a great improvement on the gross underestimate made by Livingstone in 1855.

Livingstone’s second visit to the Victoria Falls

When Livingstone reached Quelimane he was congratulated on his journey across Africa but told that the LMS directors were "restricted in their power of aiding plans connected only remotely with the spread of the Gospel."[xviii]

From Quelimane he went to England, but returned two years later, having resigned from the LMS and been appointed H. M. Consul for the East Coast of Africa to the south of Zanzibar and for the unexplored Interior. It was on this occasion that Livingstone paid his second and last visit to the Victoria Falls which has been covered in the website article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambesi Expedition with David Livingstone.

The British government agreed to fund Livingstone's idea to examine the natural resources of south-eastern Africa and open up the Zambezi River to “Christianity, Commerce and Civilisation”[xix] and he returned to Africa as head of the Second Zambesi Expedition. However, the Zambesi river turned out to be completely impassable to boats past the Cahora Bassa rapids, a series of cataracts and rapids that Livingstone had by-passed on his first journey.

During the course of extensive explorations by the Zambesi Expedition David and his brother Charles Livingstone with John Kirk visited the Falls arriving on 8-9 August 1860. They explored the rain forest on the southern side of the Zambesi where Kirk took botanical specimens and tried to make more accurate measurements of the height and width of the Falls.

Subsequent Visitors

George Lacy wrote: “A trader, H. Polson was at the same time within 50 miles but didn’t trouble to see them.[xx] The following year (1861) three or four Boer hunters made their way there, but except Martinus Swartz, they all died of fever. The year 1862 was marked by Chapman’s arrival there on his great journey from Walvisch Bay on which he was accompanied by T. Baines, E, Barry, H. Bell and J. Laing. A trader, H. Reader was there the same year.”[xxi]

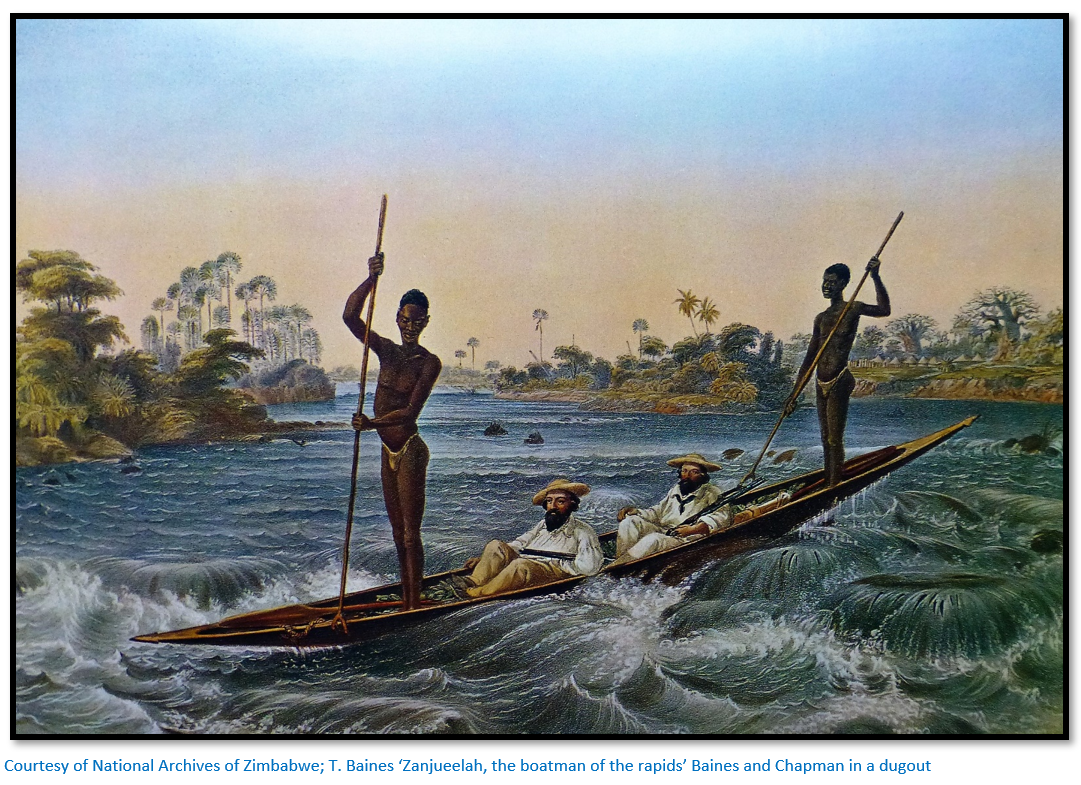

Thomas Baines and James Chapman camped close to the spot where the present-day statue of Livingstone has been erected. The same boatman who had ferried Livingstone in 1855 took them to Garden Island. The peach and coffee seeds planted by Livingstone had been trampled by hippo but they saw the initials D.L. 1855 and C.L. 1860 for his brother, Charles cut into a tree. Sir Richard Glyn and his party in 1863 found the initials of the two Livingstones and Baldwin nearly grown out, so they re-cut them and added ‘Glynn 1863.’

Gradually a steadily increasing number of Europeans found their way to the Victoria Falls although there are some years, such as 1864 and 1866 when there were none.

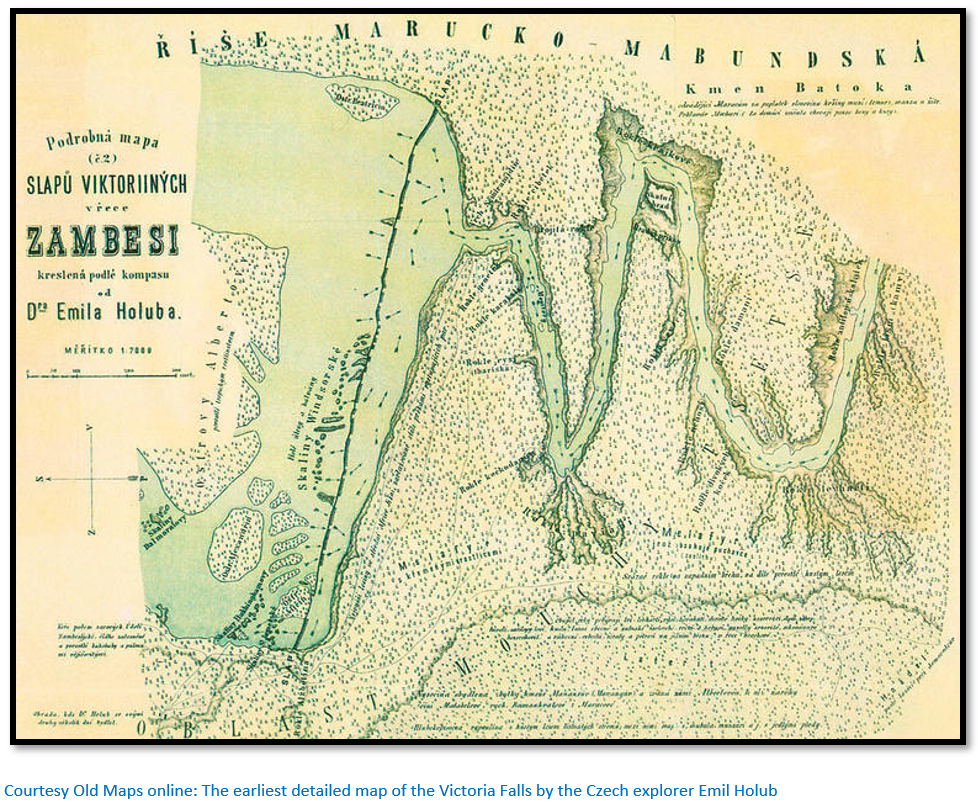

Dr Emil Holub (1847-1902) a Czech doctor was much influenced by Livingstone’s writing and gained permission with George Westbeech’s help from Chief Sipopa to enter Barotseland and visited the Victoria Falls in September 1875 in a party which included Mr and Mrs Westbeech and Mr and Mrs Francis and again in October 1885.

On his first trip he travelled up the Zambesi from Sesheke but lost much of his supplies from a canoe upset and caught fever which made him ill throughout December 1875 after which he returned to Impalera island in January with Westbeech’s cargo of ivory. On his return Holub practised medicine at Kimberley to recoup the expense of hauling his large collection to Europe which only arrived in 1880. In Vienna he held a large and very successful exhibition from May to October 1880 before distributing the many specimens to various Austrian museums. For this he was awarded a medal by the Geographical Society of Vienna.

Three years later Holub led a large expedition with six servants from the Austrian ambulance corps to South Africa and had a difficult journey to Pandamatenga arriving on 26 September 1883 after losing many oxen to poisonous plants. Westbeech advised against travelling into the Zambesi Valley in the rainy season but was overruled by Holub who insisted in visiting the Victoria Falls in October. Two of Holub’s European servants died of fever.

Holub made a further expedition in 1886 after Westbeech obtained Chief Lewanika’s permission for Holub to cross the Zambesi at Impalera Island which he did in March 1886. However he could not get porters and was still at Kazungula in June when Westbeech came to his rescue. Holub managed to travel 260 kms north-east to the Kafue river where he was attacked and robbed by local tribes. A servant named Oswald Zoldner was killed and Holub lost everything but his notebooks and struggled back to Kazungula where once again Westbeech came to his rescue.

In 1878 the Portuguese Major A da Rocha de Serpa Pinto measured the Victoria Falls with a sextant assisted by two local assistants who held him over the edge of the gorge with a cloth so that he could get his readings. Serpa Pinto was the fourth explorer to cross Africa from west to east, and the first to lay down a reasonably accurate route between Bié (in present-day Angola) and Lealui in Barotseland. In 1881 the Royal Geographical Society awarded him their Founder's Medal, "for his journey across Africa ... during which he explored five hundred miles of new country."

He clearly was not as impressed as the British visitors: “All else at Mozi-oa-Tunia is sublimely horrible. That enormous gulf, black as is the basalt which forms it, dark and dense as is the cloud which enwraps it, would have been chosen, if known in biblical times, as an image of the infernal regions, a hell of water and darkness, more terrible perhaps than the hell of fire and light…At times, when peering into the depths, through that eternal mist, one may perceive a mass of confused shapes like unto vast and frightful ruins.”[xxii]

Henry Reader’s wife may have been the first European woman to visit the Falls with her husband and child in August 1862. Cornelia Carolina Westbeech, George Westbeech’s wife on her honeymoon may have been the joint second female visitor with Mrs Francis, the wife of William Curle Francis, when they visited from 13–24 September 1875.

Detailed table of the first 100 European Visitors between 1885 - 1880

A few Boer hunters are said to have been in the Zambesi Valley prior to Livingstone’s arrival, but were stranded as in the case of the Pretorius party who endured a two-year stay after their oxen died from tsetse-fly and had to be rescued by Chief Sechele who sent replacement oxen. Pretorius died at Deka about 16 December 1862. Other parties were supposed to have been almost wiped out; Martinus Swartz is sometimes cited as the sole survivor. Swartz farmed in the Marico district, but hunted in the Limpopo Valley in 1853-4 and on the Shashe river in 1855 when he was punished by Mzilikazi for poaching elephant in amaNdebele territory. He hunted almost every year on the borders of their territory killing 294 elephants over a career of 21 years, but I can find no evidence that he hunted in the Zambesi Valley prior to 1861 and he died of fever with ten members of his family east of the Mababe Flat in 1877.

| The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880 | ||||

| Year | Date | Name | Details | |

| 1855 | November | Livingstone, David | Missionary, explorer | Travelled from Luanda to Linyati river 1854 - 1855 and first saw the Falls on 16 November 1855. Visited again during the Zambesi Expedition with Dr John Kirk and Charles Livingstone in August 1860 |

| 1860 | August | Polson, George | Hunter, trader | Met W.C. Baldwin near Tamasanka and both walked from the Matetsi river and reached the Falls on 2 August where met David and Charles Livingstone and John Kirk on 8-9 August, stayed until 6 September. The country was unsuited to hunting on horseback because of tsetse-fly and he left for Shoshong which he reached after much hardship on 24 November. Baldwin and Polson were probably the joint second Europeans at the Falls. |

| 1860 | August | W.C. Baldwin | Hunter, trader | Met George Polson near Tamasanka and both walked from the Matetsi river and reached the Falls on 3 August where met David and Charles Livingstone and John Kirk on 8-9 August, stayed until 6 September. The country was unsuited to hunting on horseback because of tsetse-fly and he left for Shoshong which he reached after much hardship on 24 November. Baldwin and Polson were probably the joint second Europeans at the Falls. |

| 1860 | August | Arend, Joseph | Hunter, trader | Griqua hunter, a fugitive from the Cape. At the Zambesi and the Falls in August 1860. |

| 1860 | August | Kirk, John | Explorer, botanist, photographer, physician | Joined the Zambesi Expedition visiting the Falls with David and Charles Livingstone for 3 days and met W.C. Baldwin there |

| 1860 | August | Livingstone, Charles | Expedition assistant | Joined the Zambesi Expedition visiting the Falls with David and Charles Livingstone for 3 days and met W.C. Baldwin there |

| 1861 | August | Swartz, Lucas Marthinus | Hunter, trader | Hunted in the Zambezi Valley in 1861-2 and was in the Barotse Valley during 1864 returning to Shoshong in 1865. Hunting at Lake Ngami in 1868-9. Died with ten members of his family of fever east of Mababe Flats in 1877. |

| 1861 | Pretorius | Hunter | Stranded at the Zambezi for almost two years by loss of their oxen to tsetse-fly. He died of fever at Deka about 16 June 1862. No confirmation they saw the Falls but likely. | |

| 1862 | July / Aug | Baines, Thomas | Artist, explorer, cartographer, concessionaire | Travelled extensively throughout Southern Africa in Eastern Cape, Lake Ngami, on the Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone, Namibia, the Zambezi Valley. James Chapman, Barry walked to the Falls from Deka and stayed 22 July - 16 August and met Reader. Travelled extensively in Matabeleland and Mashonaland and improved the Hunter's Road from Tati to Hartley Hill. Southern Africa's greatest artist and the first to paint the Victoria Falls. |

| 1862 | July / Aug | Barry, Edward | Wagon driver, manager | Visited the Falls from 22 July to 16 August with Baines and Chapman and met Reader |

| 1862 | July / Aug | Chapman, James | Hunter, trader, explorer, naturalist | Began trading in 1849 and hunted widely around the Botletle river; Zambesi boatmen refused to take him to the Falls because the Matabele were raiding in October 1853. If they had done so he would have earlier than David Livingstone. Visited the Falls from 22 July to 16 August 1862 with Baines and Barry and met Reader. One of the greatest explorers of the period who opened the Western Old Lake Route to east of the Makarikari salt pans. |

| 1862 | August | Snyman, Jan | Hunter, trader | Griqua who spoke good English and walked with Oswell to Lake Ngami in 1849. Met Chapman and Baines at the Zambesi and remained from September 1861 to August 1862; probably visited the Falls |

| 1862 | August | Reader, Henry & wife & child | Hunter, trader | Camped at the Matetsi river July - September 1862 with his wife and child; his wife may have been the first white woman to see the Falls. Met Baines, Chapman and Barry |

| 1863 | July / Aug | Gifford, James | Hunter, trader, trek manager | Wagon manager to Sir R. Glyn, his brother and Osborne on their journey to the Falls in 1863 and only stopped hunting after 1870 because hunting on horseback was more difficult as the elephants retreated into the tsetse-fly belt |

| 1863 | July / Aug | Glyn, Robert C. (brother of Richard) | Sportsman | Journeyed to the Falls in 1863 with his brother, Osborne and James Gifford |

| 1863 | July / Aug | Glyn, Sir Richard G. | Sportsman | Journeyed to the Falls in 1863 with his brother, Osborne and James Gifford |

| 1863 | July / Aug | Osborne, Henry St George | Sportsman | Journeyed to the Falls in 1863 with Sir Richard Glyn, his brother and James Gifford |

| 1865 | August | Zietsman, Paul | Hunter, trader | Hunted in Zambezia in 1860's and visited the Falls in 1865. Hunting with Mohr and K. Lee in 1869 |

| 1867 | August | Gordon, George | Trader, bookkeeper | Based in Shoshong he was secretary to Chief Macheng for a time; travelled to the Falls before 1868 and visited Logier Hill and Wankie's kraal. Again at the Zambesi in 1877 reaching Tati from Pandamatenga on 14 December with Fry, Palmer, Bray and others |

| 1868 | June | Horn, William | Hunter, trader | Accompanied Leask and Van der Berg to the Zambesi in 1868. Visited the Falls on 22 June and then Wankie's kraal in July. Traded in Matabeleland and died at Hope Fountain on 5 October 1875 leaving his wife and child. |

| 1868 | December | Lacy, George | Hunter, trader | With unnamed companion (Fred) walked from Deka to the Falls, hunted down the Matetsi river to Logier Hill |

| 1869 | July | Coverley, Dr | Physician | Reached the Falls and Wankie's kraal with Thomas Leask |

| 1869 | July | Leask, Thomas | Hunter, trader, concessionaire | Reached Pandamatenga in 1868, but not the Falls as he had fever. Next year he and Dr Coverley spent 22-25 July at the Falls. See the article Thomas Leask's two journeys to the Zambesi in 1868 and 1869 |

| 1869 | Mahure, Jan | Griqua hunter, trader | Hunted with James Chapman, lived on the north bank of the Zambesi river from 1869 at Wankie's kraal for total of eight years | |

| 1870 | June | Mohr, Eduard | Sportsman, prospector, explorer | Visited the Falls from 15 - 20 June, leaving William Cluley who was sick at Logier Hill, near Wankie's kraal |

| 1870 | June/July | Ellis, Hon Charles | Hunter, trader | No other details or who accompanied him |

| 1870 | June/July | Anderson, O | Trader, prospector | With Kirton, Martin, Broderson, Knuttel, Colville |

| 1870 | June/July | Broderson | Trader, prospector | With Kirton, Martin, Anderson, Knuttel, Colville |

| 1870 | June/July | Colville, Henry | Trader | With Kirton, Martin, Anderson, Broderson, Knuttel |

| 1870 | June/July | Knuttel, George | Trader, prospector | With Kirton, Martin, Anderson, Broderson, Colville |

| 1870 | June/July | Martin, George F. | Trader | With Kirton, Anderson, Broderson, Knuttel, Colville. Later traded from a store at the Inkwekwesi river near Inyathi Mission. |

| 1870 | September | Kirton, George | Hunter, trader | With Martin, Anderson, Broderson, Knuttel, Colville at the Zambesi with only a cart and suffered from fever in 1870; hunted at Pandamatenga in 1875 with his brother and visited the Falls again; brought his wife in August 1877 to Pandamatenga and hunted at Tamasetsi vlei |

| 1872 | Blockley, George | Trader, storekeeper, hunter | Employed by Westbeech at Pandamatenga for 16 years from 1871; his was the longest residence of anyone in the Zambesi Valley and was often at Pandamatenga when Westbeech was buying trade goods. He assisted the Jesuits and they relied upon him as a guide. In 1882 he planned to walk to Zumbo, but only made it to the Kafue confluence. He helped most of the well-known travellers and was known as 'little George' to differentiate from Westbeech; good natured and helpful and friendly with all the chiefs. | |

| 1873 | August | Dawnay, Hon. Guy Cuthbert | Sportsman | Dawnay and Moore left Mangwe on Lee's Road on 2 June and met Piet Jacobs at the Nata river and were guided to the Westbeech Road and were at Pandamatenga on 5 August. Visited the Falls 10 - 12 August before hunting around 'The Berg' and reached Tati on 18 October 1873 |

| 1873 | August | Moore | Sportsman | Dawnay and Moore left Mangwe on Lee's Road on 2 June and met Piet Jacobs at the Nata river and were guided to the Westbeech Road and were at Pandamatenga on 5 August. Visited the Falls 10 - 12 August before hunting around 'The Berg' and reached Tati on 18 October 1873 |

| 1873 | August | Garland | Hunter, trader | Accompanied Schinderhutte and Byles to the Zambesi in 1873-4; they killed 150 elephants |

| 1873 | August | Schinderhutte, Christoffel | Trader, hunter, transport rider | Employed by Phillips and Westbeech, went to the Falls with Garland and Byles in 1873. Back in the Zambesi Valley in 1874 when he lost servants to fever. Had delirium tremens in July 1875 from heavy drinking and died in the bush or was killed. |

| 1873 | August | Byles or Biles, Henry | Hunter, trader | Hunted with George Wood, Zietsman and Wood when Firmin was killed by an elephant on the Ramaquabane; hunted widely in northern Matabeleland and Mashonaland; was at Pandamatenga, August / September 1877, went to the Falls with Garland and Schinderhutte |

| 1873 | August | Truscott, James | Hunter, trader | He and his partner Wilmore arrived at Pandamatenga from the Zambezi on 24 December 1874, both with fever. Known to have traded from Shoshong until 1881 |

| 1873 | September | Humphrey | Sportsman | visited the Falls with Westbeech where he was refused permission to cross the river. Left with Schinderhutte, Garland and Byles when the rainy season began. |

| 1874 | June | Garden, Francis A | Sportsmen | The Garden brothers hunted in the Semokwe river area with Piet Jacobs, Oates and Wall and in May left Tati with George Wood and Selous for the Zambesi. From their stand place at the Deka river they all walked to the Falls by 27 June 1874 and went on to hunt elephant in the Chobe river area. |

| 1874 | June | Garden, John L. | Sportsmen | The Garden brothers hunted in the Semokwe river area with Piet Jacobs, Oates and Wall and in May left Tati with George Wood and Selous for the Zambesi. From their stand place at the Deka river they all walked to the Falls by 27 June 1874 and went on to hunt elephant in the Chobe river area. |

| 1874 | June | Tofts | Gardens English servant | Accompanied the Garden brothers to the Falls |

| 1874 | June | Selous, Frederick C. | Hunter, naturalist, explorer | Hunted in Matabeleland from September 1872 and spent four months in Mashonaland in 1872 with George Wood. Later in the year they followed Lee's Road to the Linkwasha Valley hunting elephant. From their stand place at the Deka river he walked with George Wood and the Garden brothers to the Falls by 27 June |

| 1874 | June | Wood, George | Hunter, trader, explorer | Explored and hunted in Northern Matabeleland and the south east of Zimbabwe. and Mashonaland. From their stand place at the Deka river walked with Selous to the Falls by 27 June 1874. Hunted at Lake Ngami in 1879 and visited the Falls again in 1881. Hunted in the Barotse Valley where they caught fever; Wood, his wife and child died in early 1882 |

| 1874 | July | Robertson | Hunter, wagon manager | Camped with Bond at Deka in May 1874 and hunted elephants at the Deka river. Revisited with Frewin and stayed at Deka before visiting Wankie's kraal with Brockley and Mackenna in August 1877. |

| 1874 | July | Bond | Hunter | Camped with Robertson at Deka in May 1874 and hunted elephants at the Deka river. Bond sketched the Falls |

| 1874 | September | Schuch, Harry | Trader | Accompanied Stabb and George Wood to the Falls |

| 1874 | September | Stabb, Charles H.S. | Sportsman | Walked to the Falls via Inyati with Schuch and George Wood from 18 August to 7 September via the Bembesi and Gwaai rivers and left the Falls on 9 September |

| 1874 | December | MacKenna, Jan or John | Hunter, wagon manager | In 1874 was hunting for Selous and George Wood in western Matabeleland. At end November was hired by Frank Oates to be his conductor to the Zambesi. Visited the Falls with Bradshaw and Mackenna from 31 December to 14 January. Travelled with Oates until his death below the Bakalanga kraals on 5 February 1875. Worked with Richard Frewen until discharged at Deka on 19 September 1875 |

| 1874 | December | Bradshaw, Dr Benjamin | Trader, physician, naturalist | employed by Westbeech at Pandamatenga from 1873, guided Frank Oates to the Falls 27 December to 13 January 1875. He collected zoological specimens and Walsh prepared them and left the Zambezi Valley in August 1879 |

| 1874 | December | Oates, Frank | Naturalist, cartographer, artist | Persuaded by Schinderhutte and Dorehill to leave Tati on 3 November. P. Jacobs, Van Rooyen and later Selous and G. Wood tried to persuade him to turn back. Schinderhutte stayed at Tamasetsi pan, Dorehill turned back with Selous; Oates visited the Falls with Jan McKenna and Bradshaw on 31 December 1874 returning to Pandamatenga by 13 January 1875. Oates died of fever near Wankee's kraal on 5 February 1875 |

| 1875 | August | Anderson, O. 'Sandy' | Hunter, trader | Travelled with Webster to Pandamatenga and visited the Falls with Barber, Frank, Wilkinson, Browne and Cross |

| 1875 | August | Barber, Frederick Hugh | Hunter, trader, artist | Hunted and visited the Falls with Anderson, Frank, Wilkinson, Browne and Cross. See the article Frederick 'Freddy' Hugh Barber, hunter, trader, artist - visited the Victoria Falls in 1875 and Matabeleland in 1877 under Bulawayo |

| 1875 | August | Cross, Alfred | Hunter, trader | Hunted and visited the Falls with Anderson, Browne, Wilkinson, Barber and Frank. |

| 1875 | August | Frank, Levitt | Sportsman | Hunted and visited the Falls with Anderson, Browne, Wilkinson, Barber and Cross. |

| 1875 | August | Wilkinson, Patrick | Hunter | Hunted and visited the Falls with Anderson, Browne, Cross, Barber and Frank. |

| 1875 | August | Browne, W.A. | Hunter, trader | Hunted and visited the Falls with Anderson, Frank, Wilkinson, Barber and Cross. |

| 1875 | August | Clarkson, Matthew | Hunter, trader | Walked to the Falls with Deans from Inyati via the Gwaai Valley and met Cross, Browne, Anderson, Barber, Frank and Wilkinson |

| 1875 | August | Deans | Hunter, trader | Walked to the Falls with Deans from Inyati via the Gwaai Valley and met Cross, Browne, Anderson, Barber, Frank and Wilkinson |

| 1875 | September | Afrika, Jan | Hunter | Hunted at Pandamatenga with his son in 1875; Khama forbid him from hunting in BamaNgwato territory because he poached; from September 1877 hunted elephant for George Westbeech and was still there in 1884 whilst recovering from a lioness mauling which he killed with his knife. Was at Gazuma pan north of Pandamatenga but was not molested because he was Westbeech's man; the San Khoisan there were killed or fled to safety. |

| 1875 | September | Afrika, Klaas - son of Jan | Hunter | Started hunting at 14 years with his father |

| 1875 | September | Bairn, Robert | Store manager | Visited the Falls with the Westbeech party 13 - 24 September; died at Pandamatenga, Dec 1875 |

| 1875 | September | Oppenshaw, G | Wagon manager | W.C. Francis transport manager from June 1875; went to the Falls, later at Shoshong |

| 1875 | September | Francis, William Curle | Trader | Resident trader at Shoshong by 1870; the firm of Francis and Clarke was the most important business there in the 1870's. Joined Mr & Mrs Westbeech & Holub on a trip to the Falls returning to Shoshong in October with a good load of ivory and was still trading in Shoshong in 1887 |

| 1875 | September | Francis, Mrs | wife of William Curle Francis | Visited the Falls 13 - 24 September; joint second European woman to visit with Cornelia Westbeech |

| 1875 | September | Walsh, Alexander | Hunter, trader, naturalist | Visited the Falls 13 - 24 September with Mr & Mrs Westbeech, his employer Mr & Mrs Francis, Bairn and Holub. In 1876 entered Westbeech's employ as a trader and collected bird skins. Travelled with Bradshaw to Impalera many times, escorted the Jesuit Mission from Kimberley and worked at the Pandamatenga store until 1881. |

| 1875 | July | Westbeech, George | Hunter, trader, concessionaire | Westbeech and Blockley went to Zambezia in 1871; thereafter held a monopoly of trade with the Barotse. Cut the Westbeech Road from Tati in 1872 and established his trading station at Pandamatenga. Friend of Sipopa, Lewanika, Mzilikazi and Lobengula who befriended and helped many travellers to the Zambesi until his death in July 1888 |

| 1875 | September | Westbeech, Cornelia Carolina | wife of George | On her honeymoon accompanied George Westbeech to the Falls from 13 - 24 September, joint second European woman to visit the Falls |

| 1875 | September | Holub, Dr Emil | Traveller, physician, museum collector | Wanted to trace Livingstone's footsteps; visited the Falls from 13 - 24 September with Mr & Mrs Westbeech, Mr & Mrs Francis, Bairn, Walsh and again in 1883 October 1885 |

| 1875 | September | Gosling, John | Cook | Lived at Pandamatenga as Westbeech's cook in 1875-6 |

| 1875 | September | Vean | Trader | A Swede at Pandamatenga trading August - September 1875 |

| 1875 | September | Kirton, Argent | Hunter, trader, soldier | Visited the Falls with his brother George, killed with Wilson at Shangani on 4 December 1893 |

| 1876 | January | Dorehill, George | Hunter, trader | Traded in Matabeleland from 1872 and was travelling to the Zambesi in November 1874 with Oates and Schinderhutte when Selous and George Wood persuaded Dorehill to turn back. Joined Macleod, Fairlie and Coley to Pandamatenga although only Macleod and Dorehill visited the Falls in January 1876 |

| 1876 | January | Macleod, Norman | Sportsman | His friend William Fairlie was left at Pandamatenga with fever and Richard Cowley died at Pandamatenga. Reached the Falls with George Dorehill, both caught fever. |

| 1876 | June | Hewitt, G.H. | Hunter, trader | In Matabeleland in 1865 and after a period in England returned and was poisoned by Sipopa and died at Sesheke in July 1876. Buried at the Chobe / Zambesi junction. |

| 1876 | June | Wall, Henry | Hunter, wagon manager | A Griqua at Pandamatenga in September 1875, hunted elephant for Westbeech until his employer's death in 1888 and was still in Zambezia in 1889 |

| 1876 | August | Baldwin | Hunter, trader | Brother of W.C. Baldwin, died at Pandamatenga, Nov 1878 |

| 1876 | August | Lowe, Walter Carey | Traveller | Visited the Falls with Musson, Ware, Meyer and Webster, died of fever at Pandamatenga |

| 1876 | August | Meyers, Karl | Hunter, trader, blacksmith | Visited the Falls with Lowe, Musson, Ware and Webster. He seems to have stayed in the Zambesi Valley as in July 1877 he was at Hendrik's Vlei with Weyers and met Pinto at Pandamatenga in in November 1878 |

| 1876 | August | Musson, Alfred | Trader, forwarding agent | Visited the Falls with Lowe, Meyer, Ware and Webster; traded at Shoshong with his brother George |

| 1876 | August | Ware, Harry | Trader, tourist conductor | Visited the Falls with Lowe, Meyer, Musson and Webster and by 1885 had made at least 3 trips to the Zambesi |

| 1876 | August | Webster | Hunter, trader | Visited the Falls with Lowe, Meyer, Musson and Ware |

| 1877 | Jan | Grandy, William J. | Hunter, trader | Travelled with Westbeech, Dorehill and Horner in December 1876; they were ill with fever in rainy season of 1876-7 at Pandamatenga. Grandy was better in April when buying supplies at Tati for himself and friends but died at Bakalanga towns in May 1877 on the way back to Pandamatenga. |

| 1877 | Jan | Horner, Lewis | Hunter, trader | Horner, Grandy and Dorehill went to the Zambesi with Westbeech. The three were ill with fever in rainy season of 1876-7 at Pandamatenga and Horner was still ill at Pandamatenga in June 1877. |

| 1877 | July | Scott | Sportsman | Went to the Falls with S. Anderson and Webster in 1877 leaving his wagon at Hendrick's Pan leaving by December |

| 1877 | August | Bagger, Oswald | Trader | A Swede and flamboyant character known as 'Count' and 'Uncle;' died at Lesuma, Barotseland |

| 1877 | August | Frewen, Richard | Traveller | Left Kimberley in April 1877 intending to cross the Zambesi river. Walked from Pandamatenga with Kingsley and Mackenna to the Falls by 14 August and found Palmer, Fry and McCall camping there. Frewen and Kingsley walked to Wankie's town, but quarrelled with the chief. Hunted in 'The Berg' with Selous, Owen and Dorehill and left for koBulawayo. |

| 1877 | August | Kingsley | Hunter, trader | Left Kimberley in April 1877 intending to cross the Zambesi river. Walked from Pandamatenga with Kingsley and Mackenna to the Falls by 14 August and found Palmer, Fry and McCall camping there. Frewen and Kingsley walked to Wankie's town, but quarrelled with the chief. Hunted in 'The Berg' with Selous, Owen and Dorehill and left for koBulawayo. |

| 1877 | August | Fry, Thomas | Hunter, trader | Travelled with Palmer to Pandamatenga and left for the Falls on 10 August. Met Frewen, Kingsley, McKenna and McCall |

| 1877 | August | McCall | Hunter, trader | Surname may be confused with Henry Hall; met Fry, Palmer, Frewen and Kingsley at the Falls. |

| 1877 | August | Palmer, Grey | Hunter, trader | Left Pandamatenga on 10 August with Thomas Fry for the Falls and arrived at Tati on 14 December with Fry, Wiltshire, Gordon and Bray |

| 1877 | August | Sadlier, Tom | Hunter | Hunted in Matabeleland before working for Westbeech at Pandamatenga in 1877; probably visited the Falls |

| 1877 | September | Owen. L.M. | Hunter, trader | Shot with Selous, Dorehill and Frewen at 'The Berg' - the hilly country east of Deka. Hunted with Selous north of the Zambesi in 1877-8 but they caught fever and forced to retreat to Inyati. |

| 1877 | October | Phillips, George A. | Hunter, trader, concessionaire | Formed a partnership with Westbeech that lasted from 1867 to 1888. Took Mrs Westbeech to Pandamatenga in October 1877 and in 1878 and took Mr & Mrs Williams to Pandamatenga in 1883. Resided in Matabeleland for 25 years. |

| 1878 | July | Weyers, Jan | Hunter | Hunting with Meyer at Hendrik's pan in 1877; hunted in Zambezia in 1878-9. Hunted elephant for Westbeech until 1888 from Pandamatenga |

| 1878 | August | Coillard, Rev Francis & Mrs & Elise | Missionaries | Deported from Matabeleland by Lobengula in 1878 and decided to start a mission in Barotseland and visited the Falls on 7 August; very much helped by Westbeech |

| 1878 | August | Taylor, Robert | Trader | Trading at Sechele's in 1876; in 1878 at Shoshong with a large trade in ivory with his wife. Visited the Zambesi before 1879. |

| 1878 | September | Anderson, Andrew Arthur | Trader, surveyor, artist | Refused entry to Matabeleland in January 1878; met Westbeech at the Zambesi |

| 1878 | November | Pinto, Alexandre Alberto da Rocha de Serpa | Portuguese Traveller, cartographer | Sent on an exploratory mission by the Portuguese and left from Benguela in September 1877 and arrived at Lealui, Barotseland in August 1878. Met Bradshaw and Walsh at Impalera. Visited the Falls from Lesuma on 16 November and went to Pandamatenga and left for Tati with Rev Coillard and Phillips. |

| 1880 | July | Depelchin, Henri | Jesuit Father | Depelchin, Terode, Weisskopf, Nigg, Simonis and Vervenne with Walsh as conductor left Tati on 17 May 1880 for Barotseland and the Tonga region below the Falls. Blockley took the Jesuits to the Falls 10-17 July and a mission was begun at Pandamatenga with Simonis as carpenter. Terode and Vervenne started a mission on the north bank of the Zambesi about 80 kms below Wankie's kraal. Terode died of fever about 16 September and Vervenne was seriously ill and returned to St Joseph's at Pandamatenga. The Jesuits were prevented from entering the Barotse Valley partly due to Westbeech not supporting their mission and the Jesuit Mission was abandoned about 1885. |

| 1880 | July | Nigg | Jesuit Father | as above |

| 1880 | July | Simonis | Jesuit Father | as above |

| 1880 | July | Terörde, Anton | Jesuit Father | as above |

| 1880 | July | Vervenne | Jesuit Father | as above |

| 1880 | July | Weisskopf | Jesuit Father | as above |

The real author of this article is Edward C. Tabler who over 24 years of study and research compiled all the details and particulars about the persons listed in the table above. His book The Far Interior contains the names and itineraries of over 400 persons who criss-crossed the region during this period. A typical entry has each individual’s full name, years of birth and death, parents, education and early life, their career which highlights the period they were in the region of central Southern Africa and an assessment of their achievements. All of them whether hunter, trader, prospectors or missionaries were “Pioneers” of the region and all shared the hardships and dangers of life at that time. This article includes only those who made the arduous trek to the Victoria Falls before 1880.

Photographs of Edward Tabler at Mangwe Pass through which every one of these individuals passed at one time or another are shown below as a tribute to his great contribution and achievement.

References

J. Desmond Clark. The Stone Age Cultures of Northern Rhodesia. The South African Archaeological Society, Goodwin Series

B.M. Fagan (Editor) The Victoria Falls, A Handbook (second edition) Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments and Relics; Northern Rhodesia, 1964

T. Jeal. Livingstone. Heinemann, London 1973

D. Livingstone. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa. John Murray, 1899

Zsombor Nemerkényi. László Magyar - a Hungarian explorer and map-maker of Southwest Africa.

M. Newitt. A Short History of Mozambique. Hurst & Company, London 2017

Edward C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1966

Edward C. Tabler. The Far Interior. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town 1955

J.O. Vogel. The Early Iron Age (A.D. 500–1100) in the Victoria Falls Region, Zambia. Current Anthropology Volume 17, No 4, Dec 1976

Wikipedia

Notes

[i] Fagan, P22

[ii] Desmond Clark, P7

[iii] Fagan, P58

[iv] Ibid, P62

[v] J.O. Vogel

[vi] Wikipedia - Dambo

[vii] Fagan, P70

[viii] http://webs.bcp.org/sites/vcleary/ModernWorldHistoryTextbook/Imperialism/section_6/beforescramble.html

[ix] Ibid

[x] Newitt, P32

[xi] Fagan, P27

[xii] Dictionary of National Biography, 1885 – 1900, Volume 42

[xiii] George Lacy, an early visitor, confirmed these reports in the 1904 South African Handbook No 33 – The Victoria Falls

[xv] Today called Livingstone Island

[xvi] Livingstone

[xvii] These figures are of course understated

[xviii] Jeal, P

[xix] This is inscribed on the Livingstone statue facing the Devil’s Cataract.

[xx] Nor correct; Tabler states G. Polson may well have been the second European to see the Falls with W.C. Baldwin.

[xxi] Partially correct; see the correct names in the table.

[xxii] Serpa Pinto. How I crossed Africa. Sampson, Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington. London, 1881. Vol II, P159

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

Entrance fee for visitors to the Victoria Falls

Category:

Province: