Home >

Matabeleland North >

Extracts from Frank Oates’ ox-wagon journey in 1873 from Tati to Gubulawayo

Extracts from Frank Oates’ ox-wagon journey in 1873 from Tati to Gubulawayo

Extracts from Frank Oates’ ox-wagon journey in 1873 from Tati to Gubulawayo

Frank Oates (1840 – 1875) Who was he?

Oates was lucky enough to be born in a long established and prosperous family of Leeds merchants, landowners and lawyers. His father Edward Oates (1792-1865) a London lawyer who returned to Leeds and married Susan (d. 1889) and they had three sons (two other children died): Frank, born in 1840, William Edward (1841) and Charles George (1844).

Frank[1] was fascinated by natural history from an early age. In 1860 he enrolled at Christ Church College, Oxford to study Natural Science, but failed to complete his studies due to a chest infection and suffered poor health throughout his life. However, he was an accomplished artist, a useful talent on his expeditions, and he made detailed and accurate observations of the wildlife in his sketchbooks.

To restore his health in a warmer, drier climate in 1871 – 2 he visited Central America and North America with most of his time spent in Guatemala collecting bird and insect specimens, sending many boxes of specimens he collected, or traded, back to England. For this work, he was elected a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

In 1873 he set off to explore the Zambesi River region. His travel from Tati to Gubulawayo[2], King Lobengula’s capital, is the subject of this article. His trip to the Victoria Falls was delayed three times through rinderpest,[3] lack of porters, a broken wagon and lack of approval from the King. However, during this trip to Matabeleland he recorded and collected some previously unknown species of trees and wildlife, remembered in the scientific name of “oatesii ”including the Vine Snake (Thelotornis capensis oatesii), a beautiful bright heather Dryiophis oatesii, and Dromica Oatesii, a beetle.

He reached the Victoria Falls on 31 December 1874, one of the earliest Europeans since David Livingstone on 17 November 1855, although not the second visitor as some authors state. See the list in the article The first European Visitors to view the Victoria Falls before the end of 1880 under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com where Oates is recorded as the fifty-second European to visit the Victoria Falls.

It was, he recorded in his diary on New Year’s Day, “After breakfast I visited the Falls - a day never to be forgotten.” The warnings he was given not to travel during the rains because of the threat of malaria were ignored and journeying back on the Westbeech Road,[4] he fell ill and died of fever[5] on 5th February 1875, aged 35 years.[6]

Frank Oates; from the frontispiece of Matabele Land Cover of 1889 Edition

and the Victoria Falls

Frank Oates’ death and burial was after some Makalaka kraals as they travelled south on the Westbeech Road, the present day Botswana / Zimbabwe border approximately follows the road. The ground was hard and they did not have the necessary digging tools. Dr Bradshaw sought the help of the Boer hunter Piet Jacobs, who knew the area well, and Frank was buried in an old game pit on the banks of the Tjwigwetjane River, his grave marked with a cairn of stones.[7]

In 1934, the Oates family asked the Pioneers and Early Settlers Society in Bulawayo for help locating the grave. James Haskins,[8] who had a trading store nearby, located the cairn of stones, but the headstone was gone and the following year, an iron cross with a circular plaque was cast by H.G. Issels of Bulawayo and railings to protect the grave from elephants.

The grave location was lost again until 1955 when an old Kalanga man, Leburu, guided Native Commissioner R. Tapson to the site. Tapson later took Sir Robert Tredgold[9] who told them he had erected the cross and railings under instruction from the Francistown Police. However, he also told them that Frank Oates’ corpse lay under a mound of rocks about fifty yards from the railing enclosure. A few years later, floodwaters from a heavy storm washed away parts of the mound, exposing bones and Frank Oates was re-interred within the railing enclosure.

Photo courtesy of the website www.ice-tracks.com>frank-oates-victoria-falls

Frank Oates’ diaries and journals were posthumously written up by his brother Charles George Oates and published in 1881. Some of the sketches were by Frank Oates; however, the majority are by his brother, W. E. Oates, who accompanied him as far as Tati.

In 2018 a new gallery to tell the story of Frank Oates was opened at the Gilbert White and Oates Collection Museum.[10] See the website https://gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk/category/the-oates-collection/

Frank was accompanied from Durban by his brother William,[11] and Thomas Bell (William’s servant) and they were joined at Maritzburg by T.E. Buckley and Gilchrist, who were on a shooting trip, and Gray, who was going trading to Lake Ngami.[12] The Oates brothers’ plan was to go by the usual trade route through the Transvaal via Pretoria, and then on to Shoshong, the town of Sekhomi, chief of the Bamangwato; from here either taking the direct route towards the Zambesi by the Tati River, or making a circuit in a north-westerly direction by way of Lake Ngami..

Courtesy of The Oates Collection, Gilbert White’s House and Garden Museum

1873-5 Expedition, (Back L-R): William E. Oates, Gray, Buckley

(Front L-R) Thomas Bell (William’s servant) Frank Oates with Rail

They arrived at Shoshong on 29 July 1873. It was a very dry year; the crops had failed and local people were living on locusts. As Lake Ngami was 100 miles away (160 km) through heavy sand and without water, they decided the three wagons would travel together as far as Tati from where Frank Oates would go on alone towards Gubulawayo to seek permission from King Lobengula to visit the Victoria Falls.

Frank left Shoshong on 7 August, having met the missionaries Reverends Mackenzie[13] and Hepburn,[14] soon catching up with the others and trekking together and reaching the Palatswe river[15] on 12 August. Long sections of the track had heavy sand and the oxen were beginning to tire. On the 20 August at the Seruli river[16] Frank writes, “We have been living, whilst at the Seruli, on ostrich-eggs. Fried with a little meal is the best way we have had them or made into a pudding with maizena. They are strong, unless nicely cooked.”[17]

W.E. Oates: Shoshong Mission (Gilbert White’s House Museum, Selborne)

At the Gokwe river, he writes, “The people at the Gokwe are a sort of outcast race under the Basutos, called Bushmen. Men, women, and children came to the waggon. They have fine pack-oxen. They live in the bush, Hendrik[18] says, having a sort of temporary abode near the bed of the river to the left of the road. They were ornamented with beads and had on necklaces of blue cut ones and skins. They always ask for tobacco, making signs that they want snuff. They are hunting here. They brought ostrich-eggs, exchanging them for a cheap knife, mirror, or handkerchief. I had great difficulty in buying an ostrich-feather for about three or four pounds of lead. They wanted a whole bar, and on no other terms would bring more feathers.”

Having crossed the Seribi and Motlautsie [Motloutse] rivers they reached the Shashi [Shashe] on the 24 August, “We had come extremely slow; sun hot, sand heavy, road bad, bullocks tired… There is an old Bushman [San Khoisan] here, destitute and alone. He says the Mungwato men took his gun. The other side of the river, he says, is under Lobengula, this under Sekhomi, and Hendrik says the Makalakas are not independent, all here belonging to the Matabele and Mungwato sovereignties. These Bushmen are, I suppose, the original inhabitants. Hendrik says they are slaves to the others. They certainly are outcasts. This man does not beg, takes what is given him, and lies naked with his head on a stone by the fire at night. He has no blanket...watched the Bushman make his fire with two sticks. He took off his sandals, placed a stick on one of them, and holding it firm with his foot, twisted the other stick rapidly between both hands, working it in a little hollow of the first stick, till black dust began to form. This soon turned red-hot, and there was fire like that in a pipe.”

Here at the Shashe, Frank and Hendrik watered the oxen leaving them by the river. At the wagon, they heard the cries of their lead ox in distress and ran back, Frank with his rifle. A lion had seized the ox but retreated as soon as the two men approached. Frank fired; the lion rolled over before retreating into the reeds. The dead lion was found by natives a few days later; they took the skin to Tati. The ox was so severely mauled it had to be shot next morning.

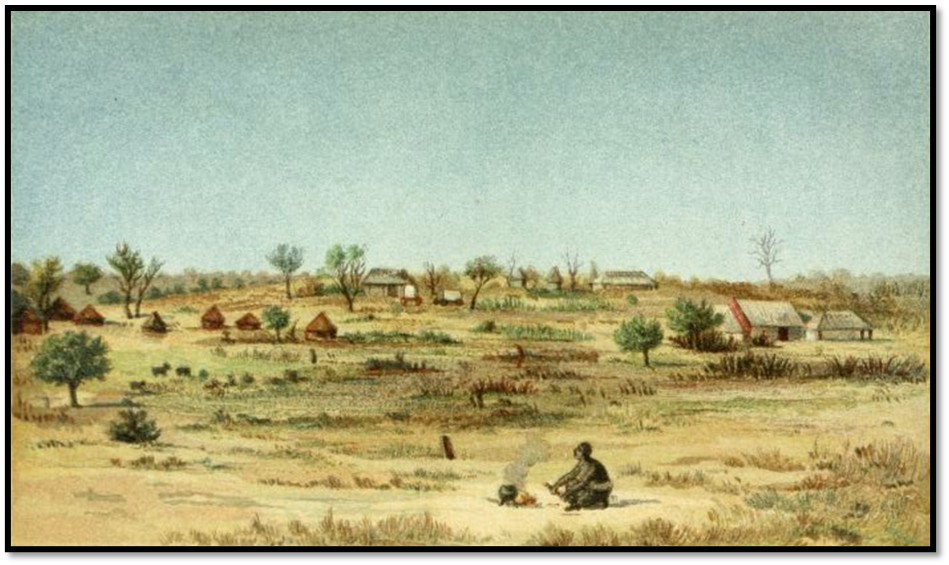

That evening they reached the tiny settlement at Tati. Frank wrote, “There is nothing remarkable in the scenery here, a few kopjes only, with low scrub and trees. Everything is very much dried up. The river is broad, with deep sand in its bed. Yesterday Nelsson[19] gave me a live fish, four or five inches long, something like a perch. He says they live in the sand now. Water is got by digging in the river's bed…The veldt where we are outspanned is quite ploughed up with the spoor of elephants which used to come here five years ago and have been found quite near here since.”

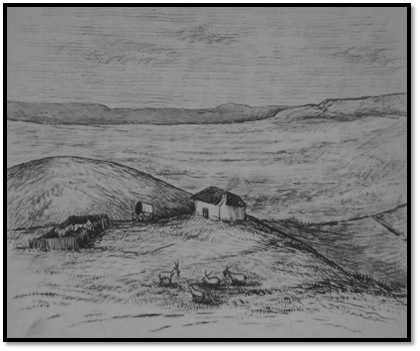

W.E. Oates. The Tati Settlement

Frank notes that there were seven Europeans resident at Tati with Nelson and Alexander Brown,[20] the mine storekeeper. For a fuller description of the Tati settlement in 1871 see the article Thomas Baines journey to Matabeleland in 1871 to obtain a written mineral concession from Lobengula and his return through the Limpopo Valley - Part 3 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com. Oates left Tati, on the 31 August, and trekking slowly, he crossed the Ramakwebani [Ramokgwebana] Impakwe, and Inkwesi Rivers, and reached John Lee’s farm on 6 September.

August 31: left Tati in the evening. About midnight, whilst trekking, Hendrick calls me, saying that the bullocks which are being driven can't be got on, but keep going into the bush. ‘Donker’ and ‘Wilderman,’ too (the little red wild ox) are getting tired. This is miserable work, and I wish I had brought more bullocks from Mungwato, as I could so well have done, and a far lighter waggon. It is a mild, breezy night, and as we outspan, and ‘Rail’ and ‘Rock’ come up, I am reminded of our first trekking on the high veldt, when we were together in force, starting with good equipment and high hopes. This is an open space where we outspan, with long grass.

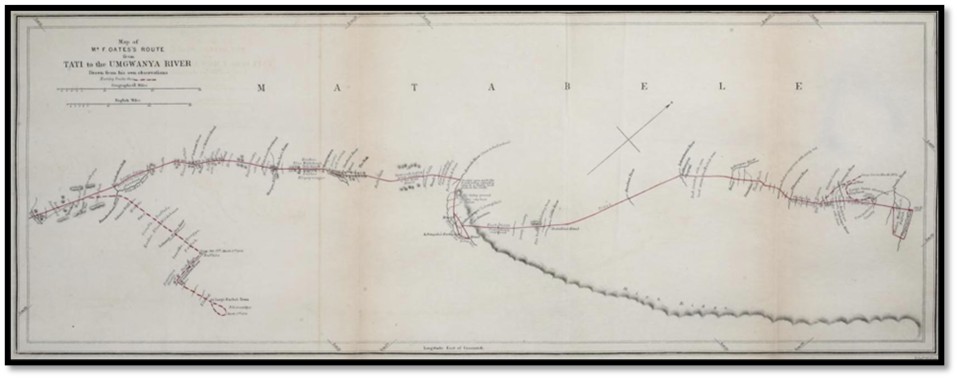

Frank Oates Map of the route from Tati to the Ingwenya river

September 1st: mild, cloudy morning…I had been much discouraged by the oxen being so tired last night, and this morning was pleased to find ourselves arrive at the Ramaqueban River at least an hour sooner than I had hoped. Petersen’s waggon was on the opposite side.[21] However, we stuck in the drift. Poor ‘Weiman,’ with his blind eye, was in front, and proved awkward, and little ‘Vinal’ lay down. Petersen, however, sent his driver and two good oxen, and and we came out easily and had breakfast. Here some Dutchmen squatted last year to hunt, and took the fever – men, women, and children. Petersen says about half-a-dozen of them died. He thinks it was in January. The trees along the river’s bed show a faint budding of green, as I have now seen for some time. The girl who came with us to Tati was travelling on with Petersen, and her brother had come on with us last night to join her. The cool breeze today was very pleasant. Petersen's boys had dug for water. Petersen went on, as he usually makes one short trek during the day. I followed in the evening, and shortly after midnight crossed the drift of the Impakwe and outspanned. There seems plenty of water in the river. Barking of dogs; encampment of Dutch hunters. Peterson had turned in. Part of this trek was through somewhat sandy country, but on the whole we are on much firmer road than we were before reaching Tati. Pitched into marmalade; it is wonderful how much one enjoys such things here, where coffee is without milk, the bread without butter, the meat dry as chips.

September 2nd: Pleasant breeze. Petersen called me. I find I am likely to have great luck. Here lives the Dutchman whose family suffered so from fever on the Ramaqueban. He has a straw hut, cool, roomy, and snug, with a higher entrance than the native huts, but shaped like them. His wife and family are with him, his eldest married daughter, and members of the next generation. He has cattle and goats, does his own smith’s work, and hunts. They go as soon as the unhealthy season begins to John Lee’s. They intend, in four years I think, to return to their farm on the Meriko. Petersen acted as interpreter, and it is arranged that I wait for the Dutchman, who intends going tomorrow in my direction to get wood and hunt. He will lend me some oxen. I believe it is nothing but the brackish water, especially the Seruli water, that has made such a mess of my oxen. The Dutchman says there is plenty of game along the road…noticed when we went out in the afternoon and we crossed the riverbed, how easily the water rose, when one of the boys scooped out a hole with his hands, very different from the dry riverbeds the other side of Tati.

September 3rd: Morning felt very chilly. Breakfast on biltong and butter; the fresh butter excellent. We branded and left ‘Rondeberg,’ ‘Engeland’ and ‘Vinal.’ The Boer put twelve of his bullocks into my waggon, eight of mine in his, and ‘Donker,’ ‘Wikieman,’ and ‘Spot’ were driven…trekked about twelve miles from the Impakwe to the Inkwesi River and outspanned about 6pm.

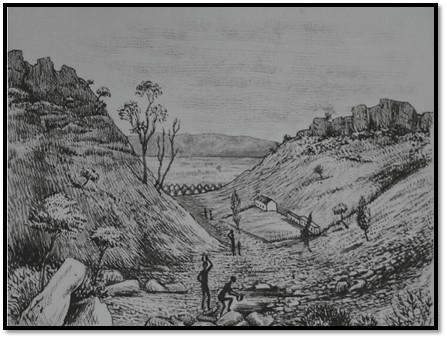

W.E. Oates: the dry bed of the Inkwesi river

September 4th: Cup of coffee, and we went out about 8am, I and the old man riding, his son walking ahead, and two of their men (Makalakas) accompanying us. I do not admire the Matabele particularly. They are independent-looking and well-made, but I do not like their countenances. The day following there were a great many about the waggons, attracted by the flesh. They eat like dogs, greedily. Beyond this river, which the Dutchman calls Makobi's, there was a tribe of Mungwato people massacred some thirty or forty years ago by the Matabele; Makobi, the chief, being amongst the slain. They were killed – men, women, and children - to obtain possession of their land. A few only escaped.[22]

The scenery about our camp is picturesque. The kopjes rise abruptly, and the river has steep craggy banks. There is an approach here to American scenery. What a wonderful difference is made in one's feelings by the constant impression caused by fine scenery! South Africa is sadly dull and monotonous, and I believe that influence is a bad one, and the loss of scenery has a depressing effect on the spirits; one's imagination is never called into play…I still admire the scenery, as we ride along home amongst the kopjes by the river. Here and there the large fleshy-leaved shrub, standing boldly out amongst the bare crags, is very striking. There is something here which might remind me a little of Central America, but somehow the charm is wanting.

September 5th: Inspanned at 7pm and crossed the river. Stony and deep descent and ascent, with very deep sand; very hard work. I am deeply indebted to the Dutchmen, who not only helped us through it - the young fellow driving and the old one helping - but, having lent us four oxen for the journey, sent for some more, to help us through this drift, after which they say all is right. Lovely moon as we trekked, but after all it is South Africa, and one cannot feel poetical. Picturesque kopjes on either side of the road; the scenery, however, not so striking as it was almost beginning to be at Makobi's. Outspanned at 10:30pm, having gone about six miles. Excellent supper on wildebeest steak, fried.

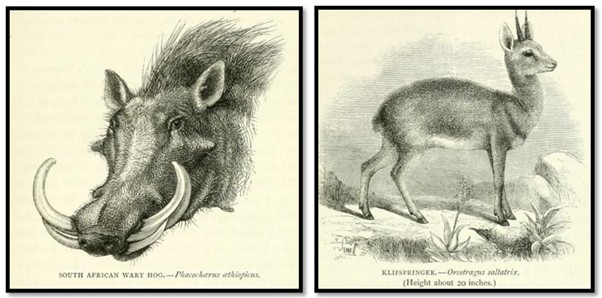

W.E. Oates. South African Warthog F. Oates: Klipspringer

September 6th: Dark cloudy morning, with a little rain. Started at 7am and trekked six miles. The country where we stopped had been much burnt, and looked very desolate, with bare ground and bare trees, but there was a fine cool wind and a cloudy sky. I could fancy it a sea breeze. They say at the King’s place you get the sea breeze. Started again at 12:30pm. Here one enters on a bit of really fine rugged country. Out of the level, scantily covered with dry brown grass and with a thick growth of leafless trees (small for the most part), rise huge boulders, so piled on one another, with here and there a huge stone so nicely balanced on the top, that one wonders how they ever got there. We are in a populous country, strings of people carrying things on the road. Outspanned at 2:30pm. Here the Dutchman, Smith, had been located, as there is a straw house, and water, the road crossing a spruit. Here, too, is John Lee's first kraal. People come round the waggon to beg meat. One is a warrior, handsomely adorned with black ostrich feathers and white oxtails. Went on again at 5pm, the ground rising a little. Then as we descend a range of kopjes appears in front. In about an hour a pretty white farmhouse is seen to the right, towards which the road winds, and the wild view makes the farm seem to welcome one.

Lee came to meet me, and asked me in.[23] He is a fat, red-faced man, His wife very young. His house had an air of comfort, and some luxury about it, owing to some handsome leopard karosses on couch and chairs. There was a picture, too, by Baines, of Lee shooting three elephants. The horse here represented, which I think cost him £100, was the making of him, he tells me. Lee was a Transvaal Boer but speaks English. He was about five years hunting. I had supper with him, and chat afterwards. Garland, he says, lost seven unsalted horses, and had to send for two salted ones. A good salted horse costs £100. Lee describes how his favourite used to sniff when game was near, and when it was elephant his manner was unmistakable. He has tried donkeys in the tsetse-fly country, but the fly has always killed them. He says all horses, with scarcely an exception, must have the sickness, but he has known an exception. This, however, does not apply to stock bred of salted parents, which often live and never have the sickness. This is better, as sickness breaks a horse down.

W.E. Oates:[24] sketch of John Lees home at the Mangwe river (Gilbert White’s House Museum, Selborne)

Lee has just sold twelve red oxen - African with white faces - for £100, unwillingly. His other oxen are all in the hunting veldt. He has however, let me have Smith’s[25] as far as Manyami’s, with a boy to bring them back. I think he calls it ten miles to Manyami’s, and from his (Lee’s) house to the King’s fifty odd miles. He says he saw some eland today but game is not plentiful just here. However, it is worse along the road to the King’s, as kraals abound. Lee does not wish to have kraals near him, and the King does not permit any to be made in his neighbourhood. Most of the hunters, he says, make a great deal of money, but spend their money as fast as they get it, saying, ‘There is more ivory where this came from.’ Lee himself was careful. His place he says, is very healthy, and it has got so good a name that in unhealthy times people stay about here, and it has been like a town, so that he opened a store. He is trying peaches, apricots, and pomegranates. Potatoes grow well here, and he is seldom without vegetables. He is trying several wild fruits. He has always water in the spruit close by, and waters by hand. He showed me a small wild grape.

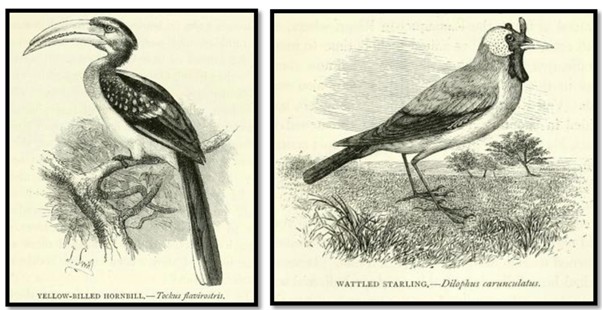

W.E. Oates: Yellow-Billed Hornbill W.E. Oates: Wattled Starling

Lee tells me that a lion may often be stopped by throwing your hat at him, when you may have time to shoot. He says an elephant gun should never be longer than 27 inches (25 is better) nor weigh over 9 lbs. He shoots 8 drams of powder, and an 8 to the lb. ball. The recoil is avoided by the barrel being strong, and nearly as thick at the muzzle as at the breech. His clothing in hunting is as light as possible; veldschoen, and he says not even a shirt if he could help it. He carries needles and thread in his hat.

For trading with the Matabele he recommends white, blue, and I think, red beads. Selampore is much liked, or strips of coloured calico. Beads, he says, seem to be going out and printed calico being preferred. The Matabele country, he says, was formerly under a queen. There were, I think, other queens before. An old man has told him the traditions, which he possesses. A famine caused the people to break up; the natives came and conquered the country. Mosilikatze came next and conquered these first natives. Makobi’s were Mangwato people, but the old inhabitants of the Matabele country were a distinct race with a distinct language. The Bushman have nothing to do with either. They seem an altogether different race, speaking a different language, and seem, Lee says, to be scattered all over the country of South Africa, a race apart from the regular inhabitants, and having no connection with them.

Lee has a young sable antelope, which goes with the cattle, about a year old. It has a rich deep chestnut colour. Lee says they get darker every year, till they become black. He once had a young elephant for some days; perhaps nine months old. He describes it as having been a most sensible and amusing pet. When first taken he made it put its trunk under his arm, and after smelling him, it was satisfied and became friendly. It always first smelt at strangers before making friends, and if once repulsed would not be friendly afterwards. It would climb in at the back of the waggon, and out of the front by the wheels, and was accompanying the waggon when it died from diarrhoea, caused by improper food. It would pick up a pin or a needle, placing it first with its foot at the right angle for its trunk to grasp, and then hold it up and examine it with a wonderful sagacity. It was excessively mischievous and would upset everything. It could not bear to be left alone for a moment and would cry like a child in such a case. The company even of a little child would content it.

September 7th: Breakfast with Lee; dinner also. One of his boys caught some barbel and a curious looking fish in the river. Talked with Lee and afterwards saw his garden. Inspanned about 8pm, and soon crossed the river with sand and reeds, and a good deal of water in its bed. It was a fine moonlight night, the road winding through picturesque kopjes. Went about six miles and then halted for the night.

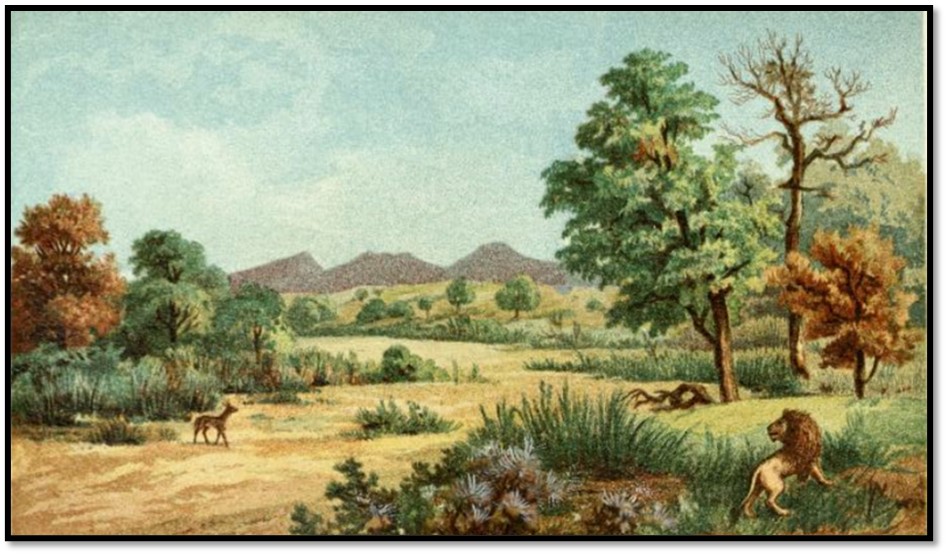

September 8th: Started at 7am and went four miles through flat land, with but few trees, and hemmed in by craggy, bush-covered kopjes. Came in sight of cultivated land and natives and reached Manyami’s kraal at 9am.[26] The country here is really pretty and presents a pleasing variety to the eye. The ground is open mostly and covered with long yellow grass; here and there groups of trees, some of a very fair size, some bare, some brown, and a few green or in blossom. Large stones crop up from the ground, and everywhere rugged kopjes rise round us.

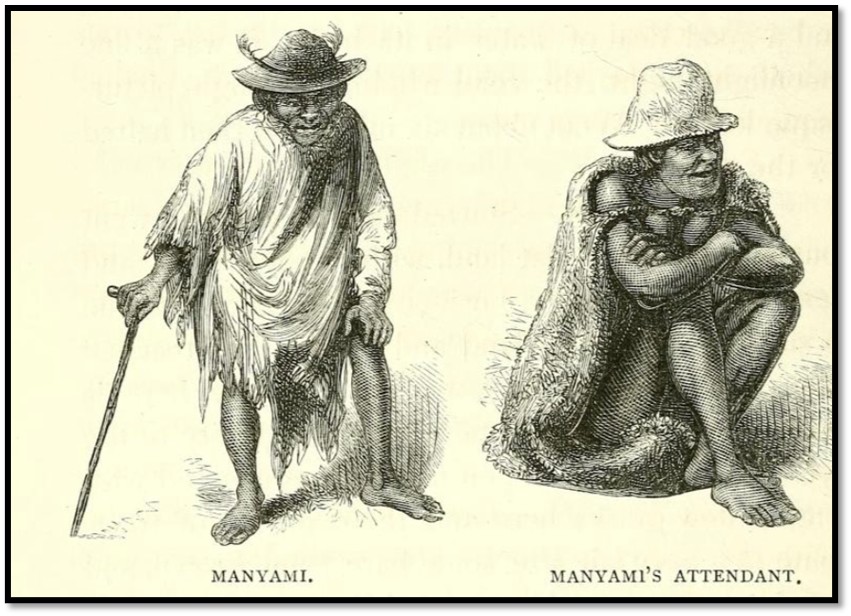

F. Oates: Manyani and his attendant

Soon after our arrival Manyami came, attended by another old fellow, each in a shabby old hat, and vying with each other in squalor and dirt. He refused firmly to send to the King till tomorrow, saying the King had not sent for me, but I had come of my own accord, and must not be in a hurry; the oxen could feed and rest. I gave him a bar of lead. Two messengers were to be sent and I wrote a note to Fairbairn for oxen, and the boy was directed to bring them back. Manyami insisted on their being paid beforehand, and intimated that they might not carry out their message properly unless I paid them. I was angry at their exorbitance, one demanding two coils of wire; to the other I gave half a bar of lead. The old fellow hung about begging. Women brought mealies and native corn. Milk and beer were also brought, and I told them to bring native corn meal next day, which they did, but were very fanciful in their demands, one wanting beads, another must have brass wire, another a handkerchief, and so on. I find they don't care for mirrors; look at themselves, and are highly amused, but refuse them as payment. Common knives are likewise refused, but gun caps taken eagerly. They like printed calico better than white, which they affect to despise. The outcry was for long strips of coloured stuff, and they preferred the quarter of two handkerchiefs (i.e. half a handkerchief in quantity) cut lengthwise, to one whole one. Stayed about waggon all day. Pitched tent and got things out.

September 9th: The night had been very mild, old Manyami came bothering early. In the course of the day he kept on coming, and I gave him twenty gun caps. Wonder of wonders, he afterwards presented me with a pumpkin, and I felt less hostile to the old creature. He is really a miserable-looking, ugly and filthy creature. Stayed about the waggon again today.

September 10th: Early breakfast, and then out with the natives to shoot. One carried my ten-bore, one led the dogs, which I am taking out to help to hunt. Went in a north-easterly direction, through very fine picturesque kopjes, with blue distant ranges; the grass long and yellow, and the trees grouped prettily; some kopjes with craggy tops, and partially covered with evergreens, others showing more of their stony formation. A good many trees are covered with bunches of cream-coloured blossoms something like ‘may’ but have no leaves.

They remind me a little of ‘snowballs.’ Here and there we see a tree whose leaves are brown or scarlet with decay. In places where the grass has been burnt, fresh green blades are springing. There are numbers of little burns here with moist oozy banks, and in many places with water in them, that I suppose find their way to the Shashani. We had to go through a burning patch of country. The flames appeared orange-red, and presented a rather formidable phalanx, writhing in the wind, and with wreaths of dun-coloured smoke rising from them, which indeed filled the air with lighter clouds of the same colour, here and there the wreaths appearing blueish, whilst a dusky haze hung over the horizon. As the flames devoured the yellow grass, they left a blackened track behind. The trees, however, seemed to escape; some in blossom, some in autumnal tints, but the greatest portion leafless.

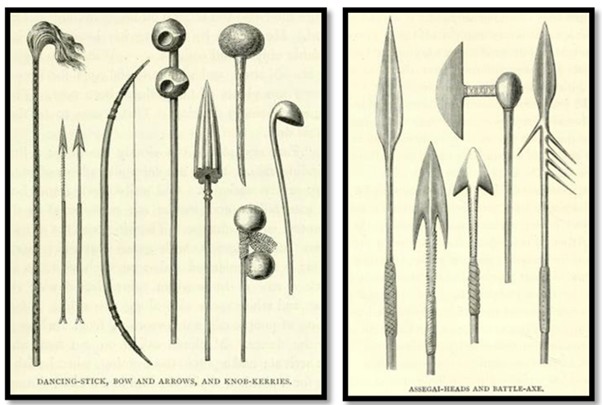

W.E. Oates: Dancing stick, bow and arrows, knobkerries W.E. Oates: Assegai heads and battle-axe

One of the boys who came to the waggon had a charm of bone suspended from his breast. It consisted of four pieces of bone, carved and strung together. By them he professes to foretell what luck will befall a hunter or anyone else. They are unstrung and shaken in the hand and then thrown on the ground. The person going to hunt must spit on the ground, and as he throws he must say, ‘My gun! May I shoot something.’ The bones, as they are hung, appear about the size and shape of a swallow-tail butterfly. I like the Matabele better than I did. They are good-natured and jovial, and seemed to understand a joke. There were great firings and noises at the kraal in the afternoon, in honour, it appears, of a man returned from the diamond fields.

September 11th: Fair, pleasant, windy day. Eight oxen and a note from Fairbairn,[27] who says I have missed a dance at Gubuleweyo.[28] The King says I am to come and make haste. A letter from Gubuleweyo to forward to the Tati excites more exorbitant demands for payment. Two boys must take it and each have a pannikin of powder. Manyami said he must see the powder before he would send the boys. Great noises at the kraal again tonight.

September 12th: Manyami brought a small elephant tusk for sale, weighing a little over a pound, and asked five coils of wire for it. I offered him two, which he accepted. He is an extremely ugly little old man, and simply filthy. Packed the waggon and started at 11am, the road winding amongst kopjes. We crossed several spruits and stopped at the Shashani river about 1pm. Beans and Guinea fowl for dinner. Dick went back to look for a screw-jack, and we lost a trek in consequence.

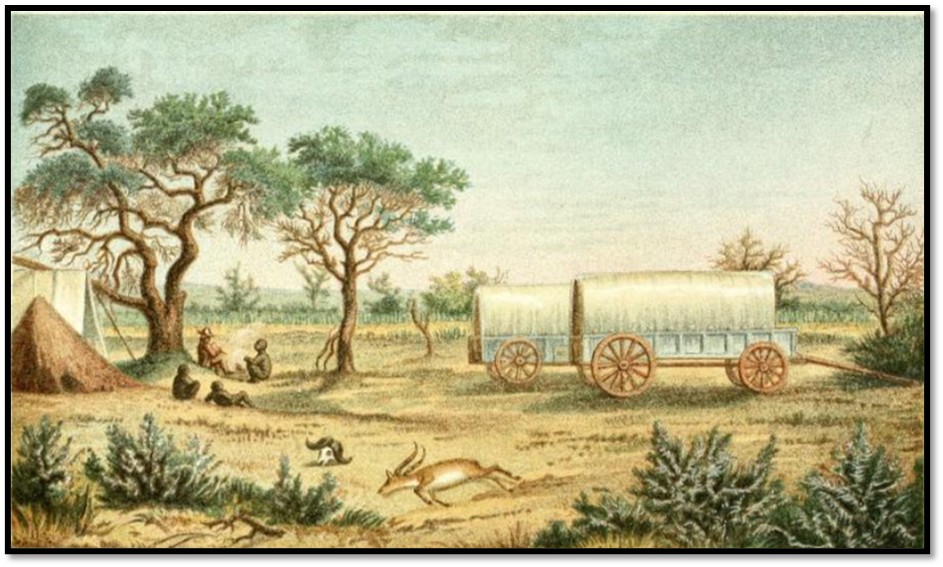

W.E. Oates: Hunters camp on the Semokwe [Simukwe] river

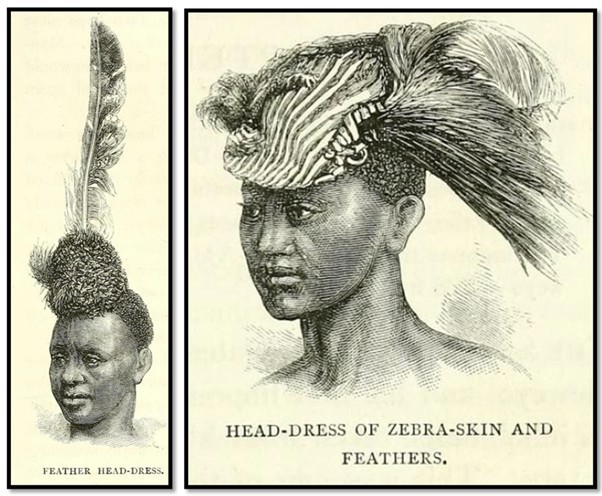

September 13th: Inspanned at 3am; most villainous jolting. Really fine country here; kopjes on every side, rising into fine crags, with huge stones strewed on the ground. In the distance more ranges of kopjes are to be seen, becoming blue against the horizon; and though the kopjes themselves are too stony to give growth to many trees, trees intervene. One could make a picture here. Country a good deal burnt in places, and fresh grass springing up green. Later in the day, after a long rest, we went through ordinary flat bush veldt, and then through an open undulating country, covered with yellow grass, a few trees and detached kopjes in the distance. Passed several kraals, and went through mealie stubble fields, fenced from the waggon track by branches rudely stuck in the ground. A crowd of natives, making a fearful noise, appeared, and accompanied the waggon to where we were going to outspan, so we went on a little further past the kraal. There was a perfect Babel. A few men came after us when we had halted - swarthy fellows, with splendid teeth. One had a fine leopard skin he was anxious to sell, others a wooden dish, beans, corn, tobacco, and beer. The men's head dresses were various and becoming. One man we passed had on a skull cap of spotted tiger-cat skin, with feathers sticking out behind like eagles or Pauw’s.[29] Others wore round masses of feathers (one was of guinea fowls) nearly as big as their heads, and one had a jackal's tail sticking straight up over his forehead. They were not at all an unpleasant looking or unfriendly set, though noisy and forward.

W.E. Oates: sketches of headdresses

September 14th: Fine bright morning, clear sky. Two hours trekking brought us to Kumala River[30], now dry, which we crossed, outspanning a mile or two further on. The country here is open, park-like and ambulating, extending away in a nearly level plain to the right. After we had stopped, a number of impudent natives crowded round the waggon. One made a fearful row, at last coming to entreaties, saying we had set the veldt on fire. Starting again at 4pm, we next went over rising ground, the country getting very clear of timber, and at 6.30pm stopped at a small spruit with water in it, having crossed two previously. A long, dry, treeless plain here stretched before us, with kopjes rising into ranges against the horizon. It seems the spruit we are now outspanned at is the head waters of a river flowing into the Limpopo, and where we were outspanned this morning is the head waters of the Kumala River, which flows into the Zambezi.

Fourteen days after leaving Tati, Oates arrives at King Lobengula’s kraal at Gubulawayo

September 15th: Another trek of about an hour and a half brought us, about 9am to Gubuleweyo. There is not much timber as the kraal is approached. The scene is picturesque but desolate, the road winding and steep. Some of the peculiar-looking trees[31] are here of great size. Strings of women were carrying vessels of water on their heads as we arrived. It was bitterly cold, and there was both wind and rain. Fairbairn and a number of others were standing about the kraal. Petersen was there and introduced me. They asked me in, and I drew up my waggon to Fairbairn's scherm[32] and had breakfast with them. Fairbairn[33] and Petersen took me to the King, whom I called on out of compliment, telling him that I had not yet unpacked my waggon - a hint that I should have a present for him. He was very gracious, and placed meat and plates before me, and inquired what sport I had had coming up, noticing the dilapidated state of my dress. I was going out of the hut legs first when he pulled me back and made me go head first. He sent me to look at his new house, of which he is very proud. It is being built of brick by an Englishman.[34]

In the afternoon Fairbairn and I rode over to see Mr Thomson, the missionary.[35] He will act as interpreter if I wish but does not think it necessary. As we returned at sundown, we met a party of natives. They were Umtegan’s[36] troop, returning from an impey [impi] or raid, with cattle taken from the Mashonas, a tribe not altogether subject to the King, though a part of them are. Umtegan was in European clothes and on horseback. They stopped to go through the exercise of certain rites before entering the town. They had only a few hundred bullocks with them. Lately some thousands were brought in by an impey[37] of a similar kind. At supper I had a young lion to pet; it belongs to the King, and roams about amongst the traders. There is a waggon at Fairbairn’s made at Beverley, in Yorkshire, which was brought out here in separate pieces, and fitted together afterwards. Fairbairn says it is a capital one. The poor man who brought it from England died before landing.

September 16th: Took the King my present - a central[38] fire shotgun with ammunition. As I approached, with men carrying it, he took me by the hand and led me to a waggon and sat on the ‘dissel-boom.’[39] We all sat on the ground. He was much pleased with the gun and thanked me. The men with me would ask for beer, and he sent us to his sister for it. She was lying on a rug at her hut door, and I was introduced.

Oates was informed it was not too late to make a dash to the Victoria Falls by taking a direct route through Inyati (Inyathi) rather than on the Westbeech Road via Tati. The next few days were spent gathering information and supplies.

September 24th: Oates spent the night with Reverend Thomson at Hope Fountain Mission close to Gubulawayo. It felt humid and the following day they could see and hear heavy thunderstorms to the north. This was the first attempt that Oates made to reach the Victoria Falls, only on his fourth and last attempt did he succeed in reaching the Falls on the last day of 1874.

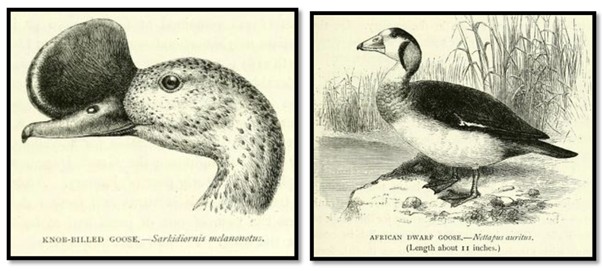

W.E. Oates: Knob-Billed Duck W.E. Oates: African Dwarf Goose

September 25th: This is the letter he wrote home to his mother:

At the home of missionary Mr Thomson, Nr Gubulawayo:

…I cannot give you a detailed account of my stay of nine days at the King’s Town. It is really to a stranger a most curious place. The king, Lobengula, lives in royal state. He is absolute monarch and feared and obeyed far and wide. The people inhabiting the country we have passed through in coming here are altogether of an inferior race. At Bamangwato there is a king, but he is thought nothing of. I called on ‘Bengula, accompanied by Fairbairn, the day I arrived here, and found him the picture of a savage king, just as one might have imagined, and coming quite up to the standard. The day I first saw him he was nearly naked, and lying on a skin inside his hut, to enter which you have to crawl in on your hands and knees through a little aperture in the front; in fact, it is like a beehive entrance. He took me by the hand, and placed meat before me, and asked a few questions about my journey. I told him I should come again next day. Of course I had to make him a present, and I knew he would expect it next day, after which I should ask his leave and assistance to go through his country to the Victoria Falls if possible. I gave him a gun and ammunition, which pleased him very much, and he has done everything he could for me.

It appeared that I was still in time to reach the Falls by going on foot, after leaving my waggon at the place marked on the map as Inyati. The king said it was possible to get to the Falls in ten days, and I suppose at my rate of travelling it ought to be done in a fortnight or three weeks at most, and the king says I have still two months of favourable weather, but so anxious is he that no white man should come to grief in his country, that he has been urging on me all possible haste from the moment the subject was first mentioned. He has given me two excellent men as guides; these two, having the king’s authority, will carry all before them.

I left Gubulawayo last night, and came on as far as here, the house of Mr Thomson the missionary, for my first trek. Mr Thomson has kindly interested himself in me and done all he could to assist me. He has a nice wife and children, and this morning I have had the luxury of a civilized breakfast, including tablecloth, bread and butter and eggs, and milk to one’s coffee – things that I don’t often see now. I am now availing myself of one of his rooms to write to you.

One of the men appointed by the king to guide me—himself a man of high character and good family, as Mr. Thomson tells me—left Gubuluwayo with me, and this morning hurried on to get bearers for me at the kraals ahead. I shall want from twenty to thirty, and as it will take some time to collect them and my oxen want rest, I shall follow slowly, making a three or four days’ journey of what is usually done in two days. At Inyati, where I am to leave my waggon, are two white men trading. These are the last outposts of civilization, but up to that point there is regular communication all the way—that is to say, all the way my waggon takes me. If I find that I am delayed and cannot reach the Falls as quickly as I had hoped, I shall very likely turn back without accomplishing my object, as I am desirous not to run any foolish risks and have been at great pains in collecting all possible information.

The men who carry my things will be most of them of the conquered population, and the two guides appointed by the king (one of whom, as I have mentioned, left me this morning to go on in advance, the other being now at Inyati) are able to do what they like. No one dare oppose the king, and the Matabele men he gives me render any fear of desertion or disobedience superfluous. Besides, these two men know that they must carry out the king’s orders to the letter. I have also got an interpreter, a man who speaks English perfectly, my own servant Hendrik, and my driver and his boy.! I shall take my tent if possible, plenty of ground-sheets and bedding, meal, tins of biscuits, and coffee. For meat we have to rely on the guns carried by the party, but there seems not the slightest fear of scarcity; in fact, the bearers are expected to live entirely on meat, having guns and ammunition allowed them for the purpose. No beast of burden or dog can accompany us, as it is the tsetse fly country.

Had it been earlier in the season, I should have gone from the Tati, by which route you can take your waggon to within a few miles of the Falls, but as I should have had to see the king first, to get his permission, by the time I could have returned to the Tati it would have been too late. I have not a map before me now but suppose it may be 200 miles or thereabouts from Inyati, my starting-point, to the Victoria Falls. I shall hurry on to the Zambesi, so as to leave the river as soon as possible. I can then take my time in returning, as when I leave the river the worst is over, and I soon get into a healthy country again; but, as of course everyone knows, the Zambesi at certain seasons of the year is unhealthy. All this I have carefully studied and have been guided by what I consider reliable evidence. I shall be further guided by circumstances that may occur and shall exercise my judgment as to how far I carry out my original project.

F. Oates: sketch of the Victoria Falls (Gilbert White’s House Museum, Selborne)

References

Editor: C.G. Oates. Matabele Land and the Victoria Falls, A Naturalist’s Wanderings in the Interior of South Africa from the letters and journals of the late Frank Oates. Kegan Paul & Co, London, 1881. Reproduced with editing, arrangement, notes and introduction by David Saffrey. Jeppestown, 2007

Dr J. Grant Repshire. Frank Oates: A life spent pushing boundaries. 6 Feb 2018. https://gilbertwhiteshouse.org.uk/category/the-oates-collection/

Christopher Prior and Joseph Higgins. The Ndebele, Frank Oates, and Knowledge Production in the 1870’s: Encounters at the Edge of Empire. Cambridge Imperial and Post-Colonial Studies. Palgrave MacMillan.

Notes

[1] Frank Oates was the uncle, although they never met, of Captain Lawrence Oates who died on 17 March 1912 on the Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica during Scott’s doomed Terra Nova expedition

[2] Gubulawayo spelt as Gubuleweyo throughout by Oates

[3] Rinderpest or cattle plague was the most devasting disease in the 19 – 20th centuries and was only declared officially eradicated in 2011

[4] For details of the Westbeech road see the article George Westbeech and the road to Pandamatenga under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[5] His death and burial was soon after some Makalaka kraals were passed. They were travelling on the Westbeech Road, that the present day Botswana / Zimbabwe border approximately follows. The ground was hard and they did not have the necessary digging tools. Dr Bradshaw sought the help of the Boer hunter Piet Jacobs, who knew the area well, and Frank was buried in an old game pit on the banks of the Tjwigwetjane River, his grave marked with a cairn of stones.

[6] Frank journeyed with his two Pointer dogs, Rail and Rock, and when Frank died, Rail went missing. Dr Bradshaw, who was travelling with Oates, searched for Rail who was found sitting at his master’s grave. Both dogs came back with Bradshaw to England, and in 1880, five years to the day that Frank Oates died Rail passed away followed soon by Rock three weeks later.

[7] Frank Oates grave is situated within Botswana, approximately 80 km north of Francistown and north of the Kalakamati

[8] Haskins Company still supplies construction and hardware supplies throughout Botswana

[9] Sir Robert Clarkson Tredgold, KCMG, PC, Chief Justice of Rhodesia, acting Governor-General of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

[10] Gilbert White’s House & Garden and The Oates Collection is located at The Wakes, High Street, Selborne, Hampshire

[11] The brothers each bought an ox-wagon and span of oxen

[12] Gray, the trader, left earlier than planned at Newcastle. They arranged to meet at Shoshong but Gray has already left for Lake Ngami. Gray having traded in the lake Ngami region previously, probably wished to leave before the rains started. They were travelling slowly; it took six weeks from Maritzburg to Pretoria

[13] Reverend John and Ellen Mackenzie – The Mackenzie’s missed the fated Makololo Mission because Ellen was pregnant and they stayed at the London Missionary Station at Kuruman in Robert Moffat’s absence. In May 1862 Mackenzie and his wife were appointed by the LMS to Shoshong. They had hoped with John Moffat and Roger Price to reopen the Makololo Mission, but Shoshong was attacked by the amaNdebele in March 1863 when only the Mackenzie family were present.

Two months later the Mackenzie’s and John Moffat’s with Hand Hai left for Matabeleland. They passed the ruins of many BamaNgwato kraals burnt by the amaNdebele and were held up at Manyami’s kraal because Mzilikazi suspected they had assisted the BamaNgwato against his men. The Mackenzie’s stayed six months in Matabeleland and Mzilikazi offered Mackenzie a choice of mission site, but he felt he could work more usefully amongst the BamaNgwato and returned to Shoshong where he was resident for the next twelve years and was well-known by all the European traders and hunters as he acted a postmaster.

[14] James Davidson Hepburn (1840-1893) was converted in his mid-twenties and volunteered to serve the London Missionary Service which trained him and sent him to South Africa in 1870 immediately after his marriage and ordination. Initially he worked at the Ngwato capital, Shoshong, assisting John Mackenzie until the latter went to Kuruman, Griqualand, in 1876. Hepburn stayed on with his growing family, becoming a close friend of the Ngwato chief Khama III, who had come to power in 1875. Hepburn moved with Khama to the new capital of Palachwe (now Palapye) in 1889, but by this time relations between them were breaking down. Khama saw his role as that of leader of his people and of the church among his people. Angry at having his authority as church leader challenged, Hepburn left for London in 1891.

[15] Palatswe river is between the Lotsani and Seruli rivers

[16] Buckley and Gilchrist left here to go hunting and rejoined Frank and William at Tati before hunting on the Semokwe river and then all three, Buckley, Gilchrist and William Oates returned to England

[17] Matabele land and the Victoria Falls, P24

[18] Hendrik was Frank Oates, Cape Malay manservant; he also had a ox-wagon driver and a voorlooper, a young boy who led the oxen

[19] C.J. Nelson, a Swedish mineralogist and mining engineer, had come to Tati as geologist of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company. However all efforts to float the company had failed as the directors were mistrusted on the financial markets after some dishonest and unreliable directors reports. The company was in debt and could not pay the salaries of Baines and Jewell, Watson and Nelson, or for any more fieldwork in the northern goldfields. Nelson left with Hübner in January 1870 to request better support from the London directors for the exploration efforts, but it was clear there were no funds and he was hired by Sir John Swinburne to work for the London and Limpopo Mining Company at Tati.

[20] Alexander ‘Sandy’ Brown – a Scot who arrived at Tati in 1869 and managed the store for the Glasgow and Limpopo Company which later also became the post office. He collected bird skins which he sold to museums and collectors. He married the daughter of the hunter Piet Jacobs in 1876 at Hope Fountain by Rev Thomson and left for Klerksdorp in July 1879. Described by all ‘as a gentleman by birth and education.’

[21] T. Petersen – either German or Danish, he worked for George Phillips and assisted Frank Oates in his 1873 journey to Gubulawayo. By 1875 he was in partnership with Meyer and on his birthday gave a dinner for the other Europeans including Cross, Elstob, Grant and Hudson in Gubulawayo. He is recorded as being at Gubulawayo in 1875 – 7, but he had a store at Hope Fountain in September 1877.

[22] The massacre took place in 1863; Makobi’s son, Mahuku, being killed

[23] John Lee, hunter and trader, first hunted elephant in Matabeleland in 1862 and in 1866 settled at Mangwe on land granted to him by Mzilikazi. In the early days of the gold rush at Tati he marked off claims and interviewed diggers. He became trusted by Mzilikazi who appointed him as agent and adviser in his dealings with Europeans. Lobengula continued with this arrangement.

[24] William Oates turned back before John Lees home was reached and the sketch was based on descriptions from Frank Oates diaries

[25] Smit

[26] Oates waited four days at Manyami’s kraal before the messengers came back from King Lobengula with permission for Oates to travel onto Gubulawayo

[27] James Fairbairn, initially an agent for Cruikshank at koBulawayo; after 1875 he traded on his own account and obtained a mineral concession from Lobengula in 1884 with his partners Phillips, Leask and Westbeech. This was subsequently sold to the British South Africa Company and Fairbairn was at ‘White Mans Camp’ with W.F. Usher adjacent to Umvutcha kraal in 1893 when the BSAC’s force invaded Matabeleland.

[28] See the article The Great Dance or Inxwala Festival under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[29] A Paauw, or kori bustard (Ardeotis kori)

[30] Khami river, flowing adjacent to the Khami river and west of Bulawayo

[31] These peculiar-looking trees are probably Euphorbia. According to Anthon F.N. Ellert at least eighteen species of succulent euphorbias are known to occur in Matabeleland. (Article – Euphorbias of Matabeleland. Desert Plants. University of Arizona. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/554347)

[32] A scherm is an enclosure or fence made with cut tree branches

[33] James Fairbairn (1853 – 1894) after losing money on the diamond fields, Fairbairn moved to Bulawayo as agent and then partner for Cruickshank at Shoshong before becoming James Dawson’s trading partner between 1881 – 1890. He entertained and helped all the early explorers; Leask, Oates, Phillips and Westbeech and assisted the Jesuits to settle in Bulawayo. Recognised by all throughout Matabeleland, he enjoyed the respect and trust of Mzilikazi and then Lobengula and was resident in Matabeleland from 1872 until his death in 1894

[34] The builder was an old English sailor who may have deserted ship named Halyet

[35] For details of Reverend Thomson see the article Hope Fountain Mission under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[36] Umtigan was one of Lobengula’s regimental commanders

[37] An amaNdebele impi would generally be a regiment of warriors on a raid ready for combat

[38] Meaning the firing pin strikes the centre of the cartridge rather than the rim

[39] The disselboom in Afrikaans means the pole to which horses are oxen are tied to and pulls a wagon

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: