Drought and then flood at Victoria Falls

In January and February 2020 Zambia and Angola both received heavy seasonal rainfall which has resulted in in many of the rivers such as the Luangwa, Kafue and Zambesi bursting their banks and flooding the surrounding areas. Last year’s drought has been succeeded by extensive and widespread rainfall as far west as Namibia where the Etosha Pan has received good rainfall apart from the far west which is still dry. Satellite pictures of the huge Angolan swamps show that they are experiencing record water levels which will feed into the Zambesi river system. Similarly the waters in the Barotse flood plains have pushed into the Caprivi flood plain and the Okavango swamps and vastly increased levels of water are now going over Victoria Falls.

At Luhonono (formerly Shuckmannsburg) on the eastern end of the Caprivi Strip and about one kilometre south of the Zambesi river water levels that were recorded at 1.84 metres in March last year are being recorded at 5.70 metres this year.[i] (Courtesy of The Livingstone biWeekly of 23 March 2020)

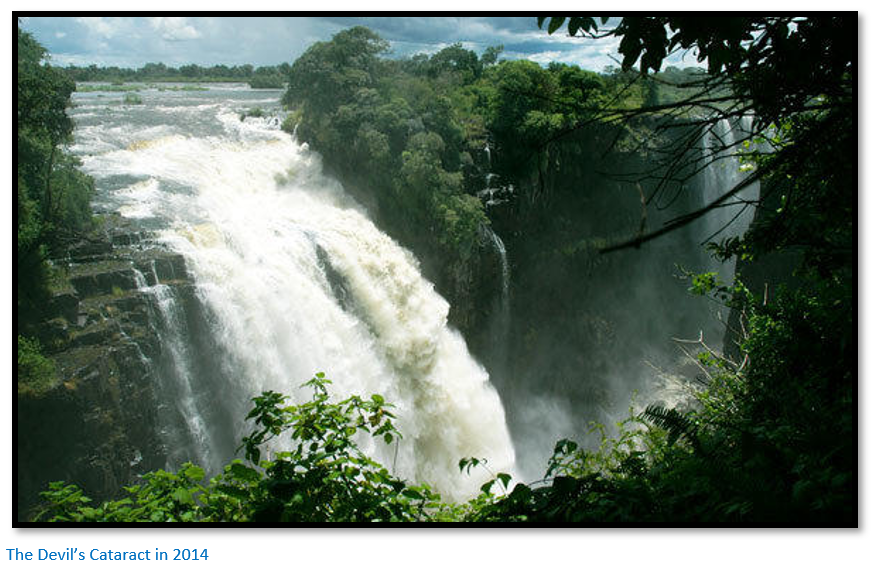

The flood waters have now hit the Victoria Falls with the volumes of water reported to be verging on those of 1977/78 which are the highest recorded since records began. This view was supported by the Zambesi River Authority which said this year’s river flows were way above average.[ii]

A Zambezi Rivers Authority spokesperson said official data shows that up to four times more water is now flowing over the world's largest waterfall than at this time in 2019. On 20 April, 3,922 cubic metres per second was recorded compared to 1,007 cubic metres per second on the same date in 2019.

The official said the first wave of floodwater was recorded on 31 March 2020 with a peak flow of 4,289 cubic metres per second. The flow at the Victoria Falls from the second flood is expected to peak by end of April at more than 4,300 cubic metres per second.

The flows at the Victoria Falls have not been this high since 2010, when they were slightly higher; they were also higher in 2009 and 1978, but the highest flows ever recorded were in 1958 when the peak flow reached an incredible 9 436 cubic metres per second.

In the coming weeks the water flows at the Victoria Falls will continue to rise and peak at the end of May this year and then fall as the rainfall in the upper Zambesi system subsides.

These increased volumes of water give hope for the recovery of the tourism sector in Zimbabwe once the Covid-19 pandemic has passed and hopes that Kariba dam will soon fill up again alleviating the current electricity crisis in the country.

Are low water volumes at Victoria Falls now a permanent feature?

The first European to view what local Lozi people called Mosi-oa-Tunya; ‘the smoke that thunders’ was David Livingstone who named the natural phenomena the Victoria Falls which he called: “a view for the angels.” Today it is considered to be one of the seven natural wonders of the world.[iii]

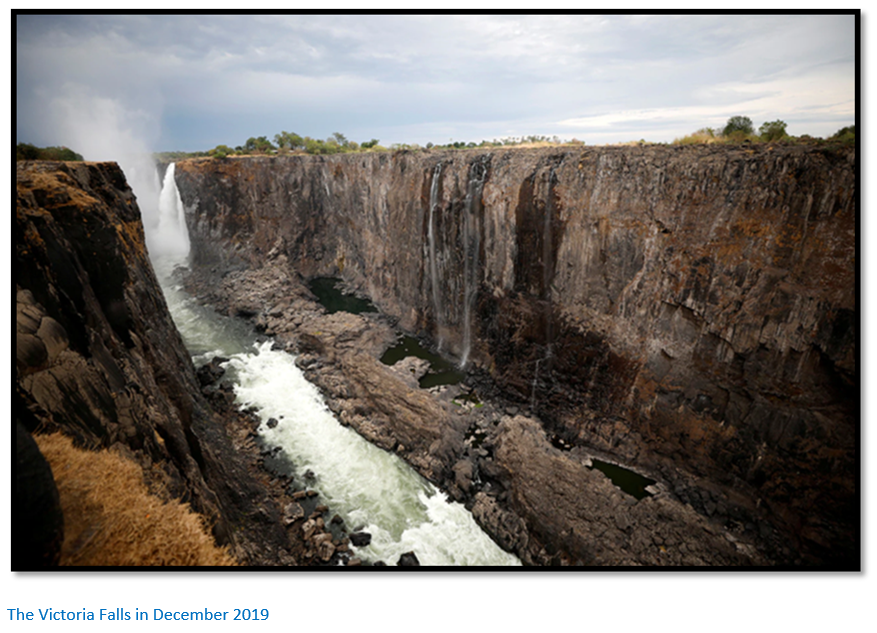

During the annual floods of the Zambezi river the 1,708 meter length of the Victoria Falls makes it the world’s largest sheet of falling water, but with Southern Africa’s prolonged drought the volume of water going over the Victoria Falls is currently (December 2019) reduced by two-thirds from the normal dry-season flow.

During the dry-season (August to December / January) the flow of water is considerably reduced as part of the normal seasonal change, but in a recent interview the BBC’s Stephen Sackur spoke with Elisha Moyo, Principal Climate Change Researcher at Zimbabwe’s Ministry of Environment, Climate and Tourism and asked if the current situation went beyond normal seasonal change.

Moyo replied that peak seasonal flow was normally from December / January to April / May; records showed that in a normal year about 2,000 cubic metres of water per second (cm/s) passed over the Victoria Falls but in 2019 the flow has dropped to around 1,200 cm/s, i.e. a 40% reduction. The Zambezi Water Authority states that the water flow is at its lowest since 1995 and well under the long-term average.[iv]

At Horseshoe falls viewpoint during a normal dry season, the water often dries up from this point eastwards to the Zambian bank and during the interview between Stephen Sackur and Elisha Moyo there was no water flowing over the edge.[v] Volcanic eruptions in the past created a relatively level layer of basalt and the Zambezi river has been cutting back along cracks in the basalt forming the deep and narrow zig-zag gorges into which the river exits after it passes through the boiling pot. The eastern cataract on the Zimbabwean side is the lowest of the five falls where the river has eroded a deep incision into the basalt and so most of the water spills here.

Moyo stated that there was a recent trend for low water levels over the Victoria Falls with a dry falls becoming an increasing possibility. In November 2019 there was 87 cm/s flowing over the falls when the climate models indicate that normal flow at this time is 300 cm/s, i.e. 30% of normal flow.

The consequences of the drought are now afflicting Southern Africa

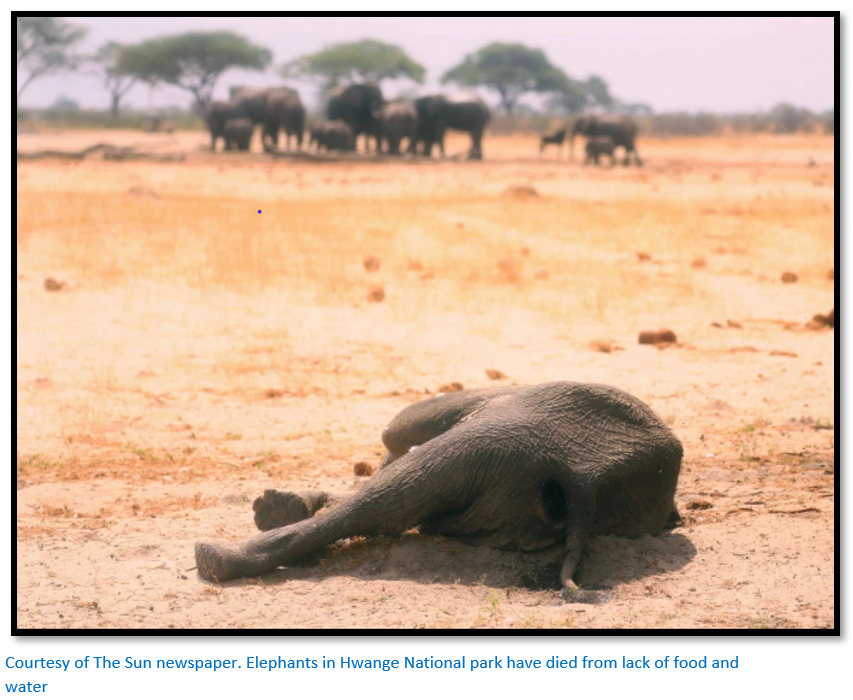

Two hours south of Victoria Falls is Hwange National Park which has the largest concentration of elephants in all of Africa and is in the grip of the worst drought in four decades. Two hundred elephants starved to death here in October / November 2019 as natural vegetation withered in the heat. Donations of solar pumps from individuals, NGO’s and charitable organizations that replaced the old diesel engines have kept the waterholes from drying out, but the numbers of elephants in these drought conditions is unsustainable.

Throughout Zimbabwe subsistence farmers are also unable to cope as cyclone Idai in March 2019 destroyed matured maize crops and this has been followed by this prolonged drought. Food insecurity has increased across the region and in Zimbabwe 7.7 million people – half the population - are dependent on food handouts from the United Nations World Food Program.[vi]

The water problem extends to the urban centres which do not have the infrastructure or resources to cope with the environmental crisis. Piped water has been spasmodic or absent for years now in Harare and Bulawayo and there is always the expectation of typhoid and cholera outbreaks which the country’s hospitals and health service will be unable to cope with.

The poor in the urban centres suffer disproportionately and form long lines of buckets and water containers in the early hours of the morning at community boreholes. Most city water comes from dams which have been severely impacted by the drought; but lack of chemicals for water treatment plants and aging pipe infrastructure have contributed to the problem as the economic demise of the country has led to the City of Harare being unable to raise funding.[vii]

The impact of the drought on electricity generation from Lake Kariba

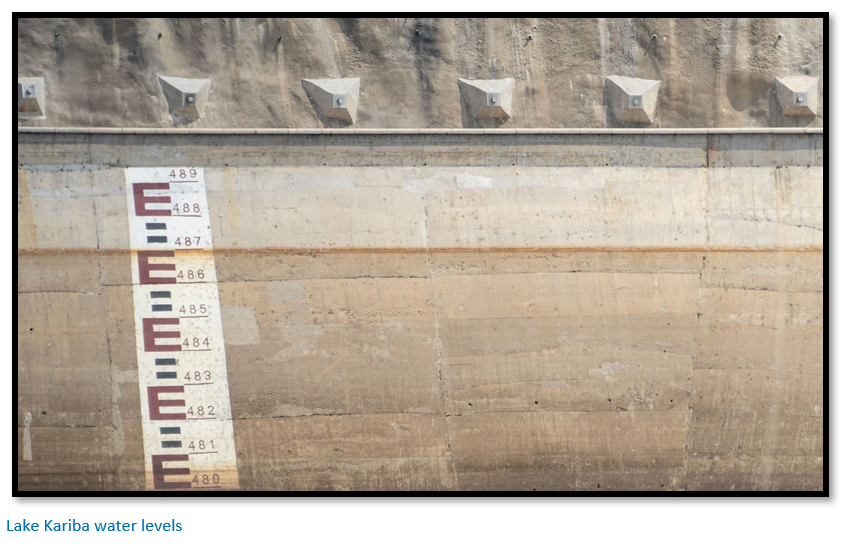

Much of the country’s electricity is supplied by hydropower from Lake Kariba since the country’s coal-fired power stations are producing little electricity due to coal shortages and maintenance neglect.[viii] But since the water flows from the Zambezi river are so low Lake Kariba’s water stocks have not been replenished and this is affecting hydropower generation for both Zambia and Zimbabwe. Zambia relies 99% on hydropower and 60% of Zimbabwe’s electricity generation is from Kariba hydropower - residents in both countries have been suffering prolonged power cuts throughout 2019 with a knock-on effect for business and industry; with no respite in sight.

In generating hydropower, flow and head are the vital components. The flow is the volume of water that can be captured and redirected to turn the turbines and the head is the distance the water will fall on its way to the turbines. The larger the flow and the higher the head, the more energy is available for conversion to electricity. Where Kariba scores is that it can produce a decent amount of energy from low dam levels as gravity (head) provides the energy boost.

The completion of the 300 megawatts Kariba South Hydropower Extension Project was expected to ease power shortages in Zimbabwe but the dropping water levels has hampered the potential project gains.[ix] Only the water above the turbine water intakes pipes, known as live water, is accessible for power generation. Water levels below the water intake pipes, known as dead water, is unusable for power generation.

The minimum water level that the turbines can operate at Lake Kariba is 475.5 meters and according to the ZINWA[x] website, the water level at 27 December 2019 was 476.71 meters or 8.36% full (2018 - 482.5 meters or 51.8% full)[xi]

Drought is one of the causes of food insecurity

The UN lists widespread poverty, HIV/AIDS, limited employment opportunities, liquidity challenges, recurrent climate-induced shocks and economic instability, low-productivity agricultural practices and lack of access to markets as contributing to the food insecurity problem in Zimbabwe.

However underlying these factors are the decades of misrule and poor economic policies brought about by the ruling political party - ZANU-PF. The current drought throughout Southern Africa makes the situation even worse, although better-managed economies such as Botswana, Zambia and Mozambique are managing the crisis better.

The impact of climate change

Zambia’s President Edgar Lungu recently tweeted that “These pictures of the Victoria Falls are a stark reminder of what climate change is doing to our environment and our livelihood.”

However Harald Kling, a hydrologist at engineering firm Poyry and a Zambezi river expert, said that climate science dealt in decades, not particular years: “so it’s sometimes difficult to say this is because of climate change because droughts have always occurred.”[xii]

Drought expert Niko Wanders of Utrecht University said the most important cause of the lack of rain is thought to be the strong El Niño of recent years and the stronger the El Niño signal, the less water is available in the region. This is first manifest in the form of less rain, soon followed by lower discharges in the rivers.

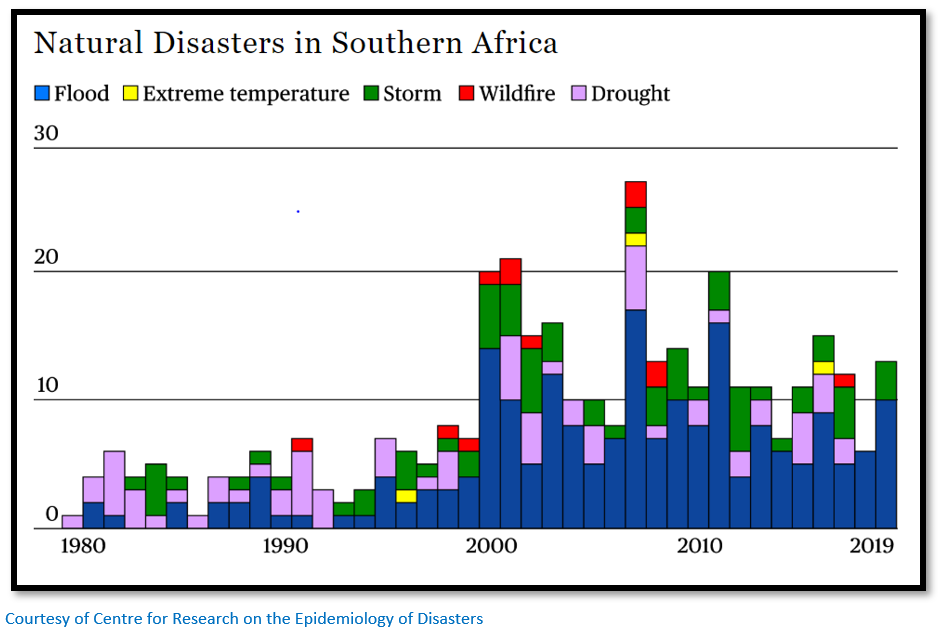

Climate change is already a reality in Africa. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Africa is among the most vulnerable continents to climate change and Southern and Central Africa have been severely affected by increased natural disasters.

Other impacts of the drought

With so little electricity available, people are turning to charcoal which they use for cooking. Trees are cut down and the wood is covered in sand to make charcoal which is bagged and sold in the town. But the accelerating deforestation in many areas will contribute to global warming and further climate change.

Tobacco growing also contributes to deforestation. In Zimbabwe tobacco is usually flue-cured and commercial farmers in the past used coal which burns hotter than firewood, but the unreliability of coal supplies from Hwange and the inability of NRZ[xiii] to transport coal has forced farmers to cut trees to provide fuel to cure their tobacco crops. According to Global Forest Watch Zimbabwe lost 13% of its indigenous tree cover between 2000 – 2017, a significant proportion of which is related to tobacco growing.[xiv]

Back to the Victoria Falls

Historically the Zambezi river is at its lowest levels in mid-November and by mid-December is starting to rise as the rains which have fallen upstream in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and the Angola highlands and local rainfall in the Barotse floodplains (or Bulozi plain) all combine to raise water levels so that by April the floods are at their peak.

Many citizens in Zimbabwe and Zambia as well as tourists to the region will be hoping that the current drought is just a temporary aberration.

[i] The Livingstone biWeekly of 23 March 2020

[ii] https://www.zimeye.net/2020/04/01/zambezi-river-flooding-upstream-vic-falls-and-kariba-kariba-dam-might-fill-up/

[iii] WorldAtlas.com considers the seven natural wonders of the World to include the Northern Lights, Victoria Falls, the harbour of Rio de Janeiro, Paricutin, the Great Barrier Reef, Mount Everest and the Grand Canyon.

[iv] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/07/victoria-falls-dries-to-a-trickle-after-worst-drought-in-a-century

[v] BBC’s Hardtalk on the Road in Zimbabwe posted on 25 November 2019

[vi] Wfp.org/countries/Zimbabwe

[vii] CNN. 24.09.2019. Zimbabwe's water woes worsen as capital shuts down treatment plant.. By Columbus S. Mavhunga and Bukola Adebayo

[viii] Wikipedia. Zimbabwe Electricity Supply Authority

[ix] www.pmworldlibrary.net by Tasiyana Siavhundu September 2019

[x] Zimbabwe National Water Authority

[xii] https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/07/victoria-falls-dries-to-a-trickle-after-worst-drought-in-a-century

[xiii] National Railways of Zimbabwe