Home >

Matabeleland North >

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa in 1891-2 (Part 1 of 5 - Benguela, Angola to the Barotse Valley)

Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa in 1891-2 (Part 1 of 5 - Benguela, Angola to the Barotse Valley)

Introduction

James (Jas) Johnston funded the expedition himself, he believed this was the only way he could be objective and free to tell his experiences as he saw them, he is one of the few African explorers who were not reliant on funding from some benefactor and therefore indebted to them in some respect.

His expedition from the West African coast at Benguela, now one of Angola’s most populous cities and from 1617 a colony of Portugal’s and important port for the transhipment of slaves to Brazil and Cuba and from 1903 Lobito 30 km north along the coast became the terminus of the Benguela Railway Company. He travelled with African servants mostly on foot, partly by canoe, about 7 250 km (4 500 miles) “passing through numerous hostile and savage tribes, traversing areas hitherto reported too pestilential for exploration, surmounting natural obstacles which have been represented as insurmountable and penetrating regions where no white man had gone before.” He writes that in all his long journey he never fired a shot in anger, or in self-defence and did not lose any of his native carriers with him.

His photographs show that what interested him was the culture and habits of those African tribes that he encountered on his journey and they responded to his interest with peace and goodwill confirming his belief that many earlier explorers had shown no interest in the cultural beliefs of African tribes or had been “too meagre in essential details and too restricted in their field of exploration to be accepted as information.”

As a boy Johnston was inspired by the writings of Robert Moffat and David Livingstone, whose funeral he witnessed in 1874. From 1874 to 1890 he worked as a doctor in Jamaica, before deciding to travel in Africa for a year or two. “Accounts were frequently being received from Central Africa of the privations, hardships and sufferings of those who were endeavouring to lead the van of light and knowledge into the dark interior - obtaining little or no aid or sympathy from the natives, for whose benefit they had risked so much. Treading the clay, cutting the sticks and grass and with their own hands, building the humble abodes that are to be their homes - white men cannot, in the tropics, do this with impunity and live. The painful fact is all too conclusive from the fearful death rate amongst those who have attempted it on the Congo, the West Coast and elsewhere.”

He chose six young Jamaicans to accompany him and on 11 February 1891 sailed for England where he kitted the expedition out for camp life. He states: “A good rule to follow is to take nothing that one can possibly do without as the carrier difficulty increases year by year and the progress of a caravan is often in inverse ratio to the amount of its baggage.”

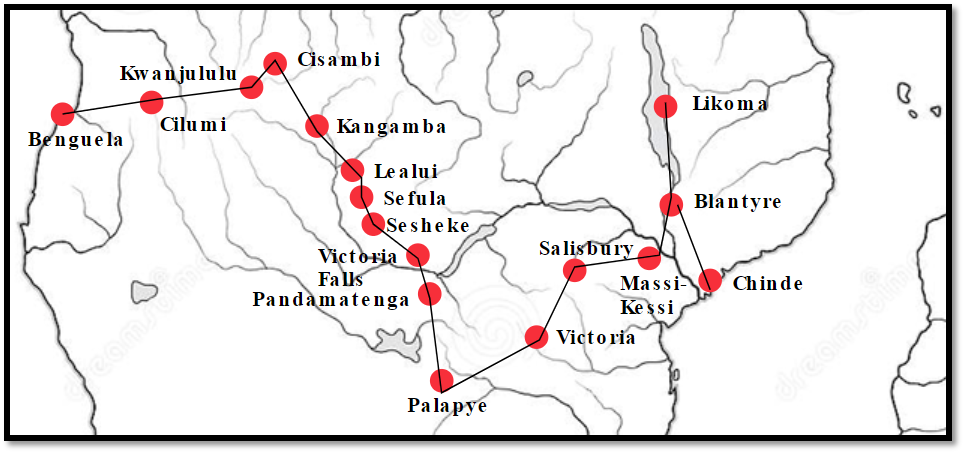

Map of Dr James Johnston’s journey from Angola to Mozambique in 1891-2

The expedition sails to Benguela, Angola

On the 17 April 1891 they left for Southampton and boarded the Trojan for passage to Benguela. “And why Benguela? Chiefly because it has the reputation of affording facilities for obtaining carriers, slave routes for the interior starting from that point.” At Lisbon they changed ships to the steamer Cazengo[i] and travelled on visiting the islands of St Thyago, St Thomé and then Cabinda, the small enclave above Angola on the 11 May.

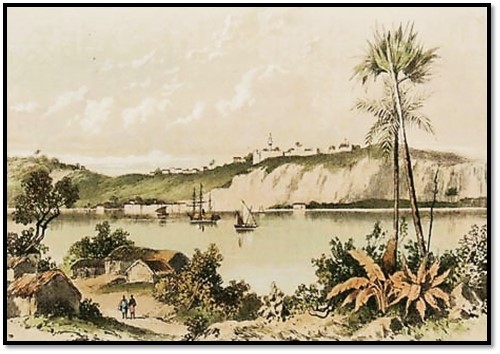

St Paul de Loanda: 1880 lithograph from The Life and Explorations of Dr Livingstone

The following day they reached St Paul de Loanda, at the time the chief Portuguese settlement on the west coast. “The last five or six days on board the Cazengo were anything but agreeable. By some bungling arrangement 500 tonnes of coal stowed in the after-hold had to be hoisted on deck and removed in wheelbarrows by the Kabindas to the bunkers for’ard, resulting in our being kept in an atmosphere of coal dust which permeated and blackened everything. But on the morning of 18th of May, Benguela was sighted and here ended our ocean voyage.”

“On landing, I began to realise how terrible was the heat on seeing a Fox terrier belonging to one of the newly arrived passengers being led along the street, when suddenly it wheeled round two or three times, gave a yelp and rolled over on its back, dead. Fearing a like fatality befalling my bulldog Gyp, I got her under shade and poured water for her as soon as possible.

The climate of Angola has an evil reputation and the odds are very much against the probability of its improving chiefly because of the low-lying situation of the town, preventing proper drainage and favouring malarial exhalations. Within the past few weeks seven European traders have been cut off by haematuric fever. Few white men can live here for any length of time without frequent visits to their mother country.”

Catambella (present day Catumbela) waiting to start for the interior

Carriers were waiting to take their personal possessions to Catumbela, at the mouth of the river with the same name, 26 km (16 miles) north of Benguela from where they planned to travel into the interior. But they were delayed for days by Customs and the fact that most of their goods were taken onto the next port at Moçâmedes, before being returned.

During their enforced stay in Catumbela they saw how goods from the African interior were traded for the most “cheap and trashy goods it is possible to manufacture - some of the calico resembling cheesecloth, though not so strong, shoddy blankets, long flintlock guns with gas pipe barrels, white pine stocks painted red and bound with numerous rings of tinsel, white rum, etc. The headmen of caravans received much-appreciated presents in the shape of discarded military clothing, helmets, tunics and overcoats by way of encouragement to come again. It is no unusual sight to see those lucky individuals strutting behind their little company as they leave for the journey homeward—one rigged out in an old pair of ’42 Tartan trousers and a helmet of the London police; another with a dismantled busby and a footman’s swallow-tailed coat ;next a silk tie and the scarlet tunic of a Highland soldier. Of course, in each case you must add Africa’s national garment—the loin cloth!”

Catambella (present day Catumbela)

“Every morning, without exception, caravans varying in size up to hundreds of natives come trudging into the town in long straggling lines, each carrier bearing a load on his or her shoulder or head of from forty to eighty pounds weight. The most pitiable sight it is possible to witness is the long procession, chiefly women, boys, and girls, limping along, footsore, with swollen ankles and shoulders chafed by burdens all too heavy for their emaciated bodies. A large percentage of these are slaves, bought in the interior by half-breed traders for a few yards of cloth and return to their homes no more, being sold on putting down their loads at the trader’s door. I saw a band of sixty such, each with a tin tag round the neck, being marched off to be shipped at Benguela for one of the Portuguese islands. ‘Were they slaves? Oh no, only contracted labour. Just so. Or suppose we call them apprentices for life! What’s in a name — so long as the letter of the law is evaded! Only this I know: that they were sold to their present owners at from three pounds sterling to six pounds per caput.[ii]

Long open sheds are provided in the yards of the houses at which the natives have come to trade and after a few days these become loathsome in the extreme, from their crowded and unsanitary condition. The death-rate at best on the coast is very high, but add the filthy, state of the kintouls, as these enclosures are called, and the mortality is fearful. Not a day passed that we did not see dead bodies, each wrapped in a bit of dirty cloth, tied to a pole and borne on the shoulders of two men to the top of the adjacent hill, where they are thrown over the other side, to be devoured by jackals and hyenas during the night, which is made dismal by their weird howls as they fight over their ghastly quarry. Deceased natives who have friends are carried out of town and buried by the way side, so that for over a mile of the path to the interior there is scarcely a yard to right or left of the track that has not a grave.”

From Catumbela to Kwanjululu

Several days were spent making up loads – 27 kgs (60 lbs) per man and on 29 May 1891 Johnston’s expedition set off for the African interior. “I take the lead myself, with two of the Jamaicans, the other four bringing up the rear; all of us feeling very fit and delighted to escape from the pestilential and fever-stricken coast.”

They take the usual caravan route to Bihe[iii] and by 6pm are setting up camp for the night, a short march, but a start. “By the time the tent is pitched the food boxes have arrived and we set about preparing supper, gypsy fashion, but with a keen relish for our frugal repast. By 8pm, all is quiet, a score of camp fires blazing and around each the prostrate figures of several men with a little grass for a bed and no covering, but the canopy of heaven and their meagre loincloths, there being neither sufficient wood, nor grass to build huts. The dew is heavy and the night cold, so that the poor fellows have but a comfortless bivouac. By daybreak all are astir. There is time only for a hasty cup of coffee with a few biscuits or the remains of last night's supper wherewith to fortify the inner man for the road. The carriers eat nothing in the morning, each man seizing his load, cold and shivering, breaks into a half trot and follows the lead along the narrow track that winds and twists, now up the rugged side of a hill and anon through the long grass of the valley. These tracks are mere footpaths, seldom over 12 to 14 inches in width, but in many places worn into deep ruts by the rains and generations of native travellers and woe betide the ankles of the pedestrian if he wears low shoes with sharp heels. The general direction is as straight as the configuration of the country does permit; but in detail they turn and bend in the most torturous fashion, without any apparent reason. A stone or stump is sufficient to switch the African out of his course and on no account will he step over a fallen tree, be it ever so small, if by making a detour he can get round it; in a short time, the white ants eat the tree, but the new path has been made, grass grows on the old and so it remains for all time.”

He describes the coastal plain between Catumbela and the Esupwa Pass as most uninteresting and devoid of water, but on the 30 May they camped at the Esupwa river and enjoyed a swim in its clear waters. “Numerous long-tailed black monkeys grinned at us from the trees as we performed our ablutions. This is a charming spot. I wonder if we shall come across many more like it.”

Next day they climbed Esupwa Pass, a stiff climb over immense boulders and reached their camp for the night about 4pm having passed no signs of habitation. In a day or two they expect to reach an altitude of 1 525 metres (5 000 feet) above sea- level. “..by the time dinner is over, it is getting dark, and after a chat round the camp-fire, rehearsing the experiences of the day and the prospects for tomorrow, we are glad to roll ourselves in our blankets and go to sleep.”

The following day they arrived in Cisangi country and at the end of the day as they prepare their camp Johnston hears shouts and loud shrieks behind his tent. His carriers are robbing a small native caravan on its way to the coast. He grabs a heavy stick and beats his own carriers until they return the plundered items. “The small defenceless party come from the far interior and belong to a powerful tribe lying right in our route. I am persuaded that many of the disasters that have befallen large expeditions through various parts of Central Africa might have been averted had the explorer in charge rigorously punished the natural pre disposition of the African to steal from the tribe through whose country he is passing.”

2 June. I find it difficult to start the carriers in the morning before the sun is up, the cold is so severe . They huddle together round the fires, and when at last they are roused to make a move, with one hand they steady their load and with the other grab a firebrand and trot off blowing upon it to keep up the glow and so supply a little warmth to their fingers.

There is a great shortage of water and of the little they find even boiling it does not stop Johnston getting dysentery and by the 5 June he is so weak that four men have to carry him in a hammock.

Then he goes out hunting for meat alone, shoots a few pigeons, but becomes hopelessly lost in the forest. He climbs trees in the hope of sighting camp and soon night falls. “I set out once more but had not gone far when I entered a deep ravine and encountered a swamp with long reedy grass towering high above my head. I pushed on, holding my gun horizontally, to keep the spear-grass from cutting my face. Suddenly my feet went from under me and I was precipitated into a deep game-pit. The branches over with which its mouth had been covered broke the fall considerably; but an angry snarl from below announced that I was not alone in the trap. I felt for my sheath knife in prospect of an encounter, but a coarse fur brushing past my face intimated that the animal, whatever it was, had no such pugnacious intent, but being equally scared, took advantage of my shoulder to effect its escape. The hole was narrow and I managed to scramble out by butting my feet against the opposite side. The struggle in the pit, however, took away the last vestige of strength I possessed and to go farther was impossible.”

He fired the last of his cartridges and to his relief heard answering shots and soon the shouts of his men getting closer told him he would be sleeping in his tent that night and not in the forest.

Next day they camped at the base of the Olonbingo range of mountains. His aneroid barometer here indicated an altitude of 2 195 metres (7 200 feet) “I noticed by the pathway a great many blocks of wood, from a foot to eighteen inches long and about five inches wide with an oblong hole cut in each. These, I was informed by the natives, were the articles used by slave-traders with which to fetter their captive carriers during the night. The feet are passed through the hole and a wooden peg driven between the ankles.”

Olonbingo rock mountains

“Numerous bleaching skulls a little way from the track tell how the slaves whom death has set free are disposed of. But the headman of an ordinary caravan is generally buried in a very respectful manner, his hat, umbrella, cooking-pot and powder-barrel being invariably placed on the grave. Over all a rude hut is built, open at the sides, while near by a rough seat is erected, lest the spirit of the departed should get tired wandering up and down—as they suppose it does—and, returning to the spot, it might be gratified by this mark of consideration for its comfort on the part of the relatives or friends and so refrain from haunting or troubling them.”

8 June. Soon after starting their march they came across four Portuguese soldiers with Snider rifles and bayonets who said that an officer and his wife were on their way to Bihe, but their native carriers had deserted, leaving their loads in the bush. Clearly they believed Johnston’s porters would make good substitutes, but he pointed at his Winchester and Webley and said that if any of his porters were taken it would bring about the funeral of a soldier before the sun had set. The quartet left, but they heard that twelve porters were seized and bound from a following caravan and marched off at the point of bayonets.

“Two days more bring us to the Bailundu country. The ground being white with hoar-frost in the early morning, it is very difficult for the first hour or two to urge the men along; they want to stop every few minutes to make a fire , while some sit down to cry over and hug their cold feet.”

“On the 10 June we reached the Keve River. Some of us were ferried across in a native bark canoe, others waded over. It is said by some travellers that this stream is likely in the future to prove a great water way into the interior from Novo Rodondo.[iv] The wisdom or otherwise of the suggestion may be judged from the fact that the body of water is comparatively small, navigable for most of the year only by canoes and its elevation five thousand feet above the sea—a pretty steep climb for steamers in that short distance. But what would they come here for, anyhow!

Another few miles and we reach Utalama, the village where poor Morris and Gall died and lie buried a stone’s throw from the path, the graves enclosed by a palisade of sticks.” Morris was a merchant from Walthamstow who with his wife came to Angola as missionaries and although carefully nursed by his wife, died of fever with Gall dying of the same fever four hours later.[v]

On 11 June some of Johnston’s carriers refused to carry their loads, but by coaxing and threats he managed to persuade six of them to accompany him the 30 km (18 miles) to Cilumi, an American missionary station where he was welcomed by the Revs. Stover, Woodside, and Cotton, their wives, and Miss Clark, a young Canadian lady who assists in school-teaching. He writes: “The marked improvement in the social condition of the natives in the neighbourhood, as compared with those we have met hitherto, testify that, if slowly, yet surely, the power ‘for good of a mission such as this, conducted on practical common sense as well as Christian principles, must in due course become manifest both in the lives and homes of the people among whom it is established.”

“…I accompanied Mr Woodside on a visit to Ekwikwi, king of Bailundu, at his ‘ombala’ or capital. The royal village is situated on the top of the hill, commanding a good view of the surrounding country. A hole in the palisades, about 20 inches wide and five feet high forms the grand entrance to the courtyard, which at night is used as a cattle pen. Here we found his majesty, seated on a stone placed against the fence. At a distance of some 30 feet and in a semi-circle, squatted a large number of minor chiefs, counsellors and headmen. In the centre, sat a man who was being tried for his life under indictment for witchcraft and by his side an aged chief, who had espoused the culprit’s cause, was, at the time we entered, eloquently pleading the innocence of his client. The speaker stopped short as we appeared and waited until the ceremony of being ‘presented at court’ had ended. The king greeted us cheerfully, graciously accepting a present of cloth, a bit of soap and a box of matches and we took seats, by his request and favour, on stones close to ‘the bench.’ The advocate then proceeded with the case, while Ekwikwi kept up a running fire of interrogations at Mr Woodside concerning the stranger. Who is he? Where from? Wither bound? etc.

The King has a shrewd and intelligent face. He is probably about 60 years of age and rejoices in a harem of over 50 wives, most of them being captives from distant tribes, brought home as booty during his periodical raids on districts which he thinks ought to pay him tribute and don't! Only a short time ago, he returned from one of these campaigns bringing back some 60 slaves and large herds of cattle.”

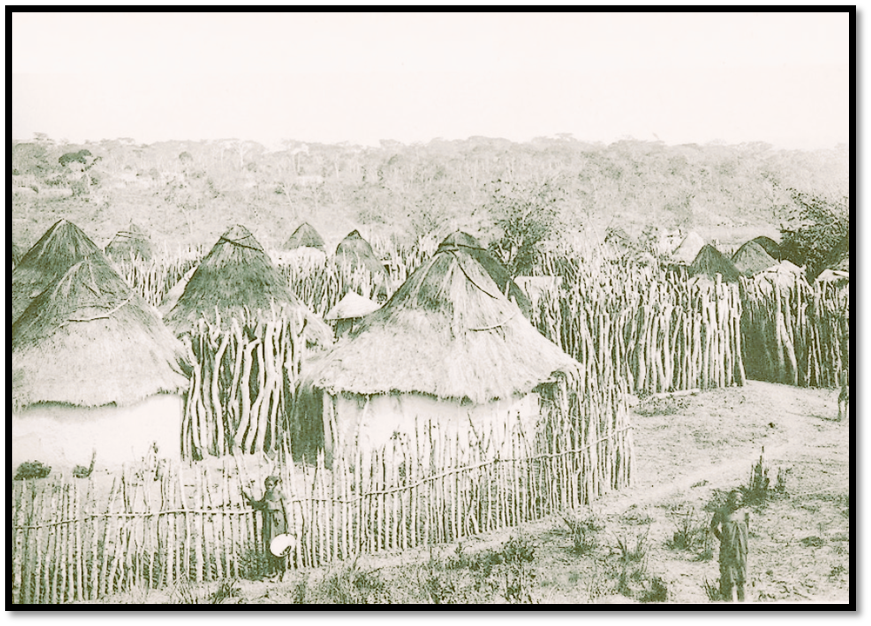

Stockaded village of Ekwikwi, king of Bailundu

On 13 June they left Cilumi Mission knowing that their caravan would be far ahead and needed to be caught up. “Here, as all through the forests of Angola, are to be found many artificial beehives, made from the stout bark of a tree 4 or 5 feet long and from 12 to 15 inches in diameter…The edges are then drawn together by means of pegs and withes and the ends closed in by weaving grass over them, leaving a small hole for the entrance and exit of the bees. These hives are then placed in a horizontal position high up among the branches of the trees, and from them is obtained most of the wax exported from Benguela and Loanda.”

“A sharp 5 hours march brings us to a stream, where we find the loads are all laid down while the carriers fill their water gourds and rest a bit. At our approach, Frater reports all correct, and each man shouldering his load, falls in Indian file, as usual, along the track, which in this part of the country must be very old, for it is worn in some places 14 inches deep and about 9 wide, causing many a hard knock from the heel of the opposite shoe, as hour by hour we thread the narrow ditch.

Four more marches. Today, a counterpart of yesterday, nothing of important occurring, except that on the fourth day we travelled 25 miles and reached Kwanjululu at about 3 pm. Here we must pay off the men who have brought us thus far - 312 miles from Benguela - and remain for some time to collect a new set of carriers for our next stage inland.”

Kwanjululu

“Kwanjululu is the headquarters of the English Brethren mission and is situated in the territory of Bihe, within a day's march of the American mission stations, Komondonga and Cisamba. This entering a district already occupied by the American mission has been unfortunate and the cause of no little friction. Surely there is room enough in Africa for different societies to organise mission centres without treading on one another's toes.

The Kwanjululu mission is superintended by a Mr F.S. Arnot.[vi] The supporters of this enterprise have been led to contribute large sums of money toward what may be truthfully designated a huge farce, and, when the manner in which they have been hoodwinked is brought to light, disastrous reflections will be cast upon the noblest enterprise of the Church of God at the present day - foreign missions.”

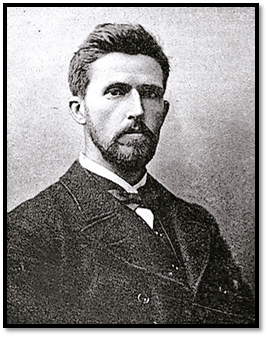

Photo Wikipedia: Frederick Stanley Arnot

“Whatever Kwanjululu may be as a transport depot, its influence as a Christian mission is almost nil. But few natives attend the meetings and next to no evangelistic work is being done. Not a single gospel meeting was held for three successive Sundays in last month, nor came there a solitary hearer from outside the compound.”

One of the staff at the Garanganze mission told Johnston: “little spiritual work has been accomplished there, the time being occupied chiefly in making gardens, hunting for food, waiting on king Msidi, and personally conducting the transit of supplies from Kwanjululu.”

Another from the same mission said: “It is now nearly three years since we came here and how very little seems to have been done! If we add the two years that Brother Arnot was here, it makes five years. What a length of time to have been living in the country and yet many of the natives scarcely know our object in living among them!”

On the 22 June they set out to visit the American mission at Komondongo. “About half-way stands the Portuguese fort, Silva Porto. I called on the captain in command to present my compliments and show my passport and found him very polite and agreeable. He conducted me round the premises, where everything was neat, trim and ship-shape. The fort is garrisoned by a force of some two hundred slave soldiers armed with Snider rifles. In the armoury stand four field pieces including a Krupp and a Nordenfeldt.”[vii]

A recent native rebellion led by the king of Bihe had left every village on the journey burned to the ground, leaving nothing but charred palisades and ruined huts. Boers were hired at one pound sterling per day to put down the rebellion – sufficient to say that the native with their flint-locks and belief in the magic spells were soon subdued.

At Komondongo the travellers received a warm welcome from Rev Saunders and his wife. Eleven years previously in May 1884 this mission and the one at Bailundu had been expelled by king Ekwikwi whose mind had been poisoned by the jealousy of mixed race traders. The missionaries were all forced to leave for the coast with only what they could carry and suffered great hardships and dangers on the way.

Here Johnston states: “that twice on Sunday the large meeting house was well filled with attentive hearers, both men and women, besides a well-attended Sunday- school between the services.” However he despairs of some of the cultural traditions, writing: “it would be a great achievement if the young men and boys could be induced to work in the fields, for at present manual labour - indeed, every form of hard work, falls to the lot of the women alone, while the men try to amuse themselves and kill time hunting, visiting their friends, making a mat, a basket or doing a little sewing; but as a rule they are chronic bummers and inveterate idlers, not even caring to mind the babies.”

From Cisamba to Kutunda – a change of plan

1 August 1891. It has been six weeks since Johnston wrote up his journal as he waits to get carriers. In desperation he sends some of his packages back to the coast for shipping to England, but still needs bearers for fifty loads of trade cloth, beads, provisions, etc. to enable him to continue the journey.

The expedition’s camp at Cisamba

The 3 August finds him at Cisamba, 30 miles northeast of Kwanjululu, camped in the forest near one of the mission stations of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, run by the Rev. W.T. Currie of Canada. He originally intended going through Katanga country and striking east to the Great Lakes, but on the advice of the missionaries decides to go farther south, in the direction of the Barotse Valley and visit the French Evangelical Mission on the Zambesi, from there going onto Lake Nyasa. In the meantime, he delays several weeks to learn the basics of the Umbundu language through an interpreter. During this pause, his Jamaican servants help Rev Currie construct a building as Rev. W. Lee is coming to join him accompanied by his wife.

Johnston assists by visiting nearby villages and aiding with medicine the many sick people who came every day to the mission at Cisamba for relief.

Johnston’s Jamaicans assist in building a mission house at Cisamba

One day he sees hundreds of women and children in stooping postures among the young grass that has sprung up after the annual fires. They are harvesting caterpillars which are stored in calabashes and baskets and dried in the sun, before being stewed and eaten as a relish with their maize porridge.

Strangers from another tribe who die are placed in trees so relatives coming to inquire after the departed can be directed to this elevated resting-place, where they may identify the body for themselves. For a funeral the village where the death took place will be filled with people, an ox killed with a big feast. Some of the meat is laid aside for the spirits and the horns of the animal stuck on a pole by the grave, together with the earthly belongings of the dead person. For several days there will be much beer-drinking, with the nights spent dancing, singing and drumming.

Bihean pombeiros (headmen) near Cisamba

At the cross paths near villages and in the vicinity of native huts there was often a miniature grass hut about 60 cm (2 feet) high with a small door erected by the local spirit mediums. Sometimes they contained carved wooden images or broken pottery egg shells or hair. Their function was to scare hostile neighbours, insure the safe return of warriors on plundering expeditions and to protect their families during their absence.

Native women at Cisamba

8 September. The expedition leaves Cisamba although four of the Jamaicans and some of the carriers remain to assist with the building. They camp at the edge of the forest outside Kopoko, 13 km (8 miles) from Cisamba from where they attract all the residents. Johnston eats his dinner which attracts great attention with mothers lifting their children to see the strange performance of him eating with a knife and fork with every movement watched with unabated interest! He then takes out his cornet, but at the first shrill blast there is a stampede as everyone except a few old men tries to escape the sound none of them has ever heard. Peering from behind trees at a safe distance, they see the sekulos are unhurt and even laughing, so they return and resume squatting and to quiet their nerves pass around the snuff-boxes as they all take snuff, both men and women. First time the experience is amusing, but when it is repeated day after day, he says he feels faint at the sight of approaching visitors!

In order to get carriers he visits the chief of Kopoko. Johnston must not walk but is carried in a tipoia[viii] although the distance is just a mile. His spokesman with the cornet takes the lead, behind is carried a camp-chair and another carries cloth as a present and they are followed by the favoured individuals who have been invited to the meeting. They are seated amid a great clapping of hands from the courtiers who squat in a circle around them. It is not considered correct for two chiefs to talk directly so it is conducted through the interpreter Sanambello who tells the chief that Johnston has come to see the country and has shown kindness to the people by paying them well, giving medicine to the sick and needs carriers to continue into the interior.

Then chief Kopoko’s prime minister takes his turn. His face, like several others they see, has been disfigured by the bursting of a trade flintlock gun bought from a trader at the coast. He talks at great length saying we have been long enough at Cisamba for them to hear good things and they know their carriers will be dealt with fairly and protected on our travels. In the end he has to endure fourteen frustrating days before he gets some carriers. The excuses for delay were many and varied. They were to have started on 17 September, but the child of one of the headmen fell sick and the cause had to be established by a spirit-medium. Another headman said his men refused to go because news had reached them of war in Ganguella territory through which they would have to pass, about four or five days’ march from Cisamba. Eventually they leave on 23 September for Ciyuka arriving the next day.

Here the chief Ohosi was sick but recovered quickly once given medicine and in return sent a fine black goat and basket of maize meal. At an altitude of 1 200 metres (4 000 feet) the climate is better than at Bihe. Sugar cane, mealies, pumpkins, yams and sweet potatoes grow well, but attempts by missionaries to grow bananas and plantain have not succeeded; this may be because of black frosts in July – August.

Every article has to be moved daily or placed well above the floor as the white ants will destroy everything. The wood bottom of the camera case has been eaten as well as the tarpaulin that serves as a ground-sheet for the tent. Fortunately, there are no grass lice or ticks, as found in the West Indies.

Many of the carriers who were previously recruited have returned their loads and deserted. When chief Ohosi is told, he turns around and orders each of the young men standing around to take a load to Katunda 15 km (9 miles) away. In a few hours they are on the road, escorted part of the way by the chief himself. At Katunda more carriers are engaged, but there is a delay of a day or two so the women can pound maize meal to take with them.

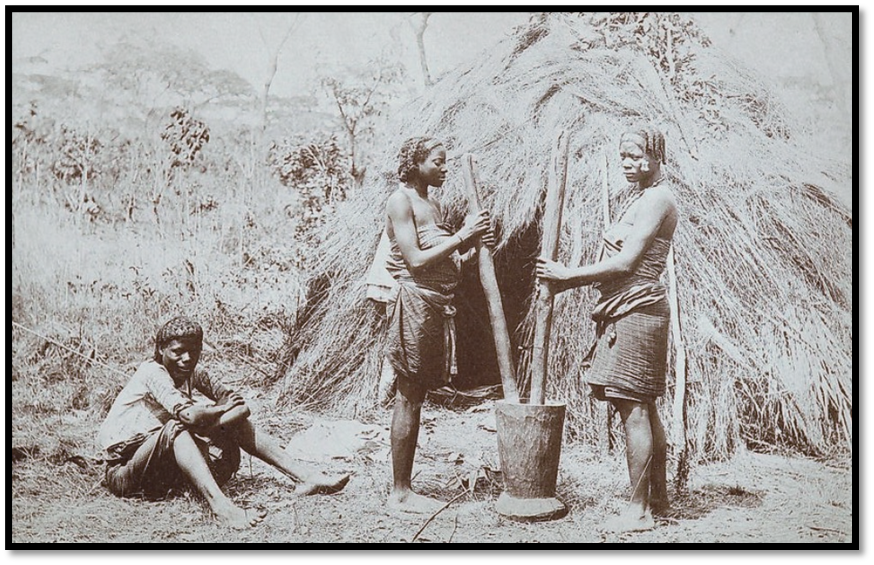

Women pounding maize with pestles and mortars at Katunda

The man above appeared with two of his wives and said he would get his wives to pound a heap of maize for half a yard of calico cloth each.

Among the Ganguellians

On 1 October the caravan leaves Kutunda at daybreak…fifty carriers with 27 – 36 kg (60 – 80 lbs) loads, eight pombieros (headmen) and thirty-six youths carrying meal, salt and dried fish for the men. Everyone was in high spirits, the men singing in noisy chorus.

After half an hours march in the forest Johnston’s thoughts were rudely interrupted by the sight of a full-grown male lion on the path fifty yards ahead. By the time his gun-bearer brought the “express” the beast had vanished, but the sight of it kept all the carriers together with no stragglers!

At Kondole they found ready-made huts that had been occupied the night before by a caravn taking ivory and rubber to the coast. However during the night a heavy thunderstorm broke out sweeping the grass off the huts and leaving everyone drenched to the skin.

Next day everyone was up early and marching to dry off their garments. There was nothing remarkable about the country except the giant ant-hills, well-known in the Cisamba district, that can be upto 5.5 metres (18 feet) high and 9 metres (30 feet) wide. They took several hours crossing the Kukema river and decided to camp the night at the nearby village where chief Cipopa promised huts for Johnston’s men. He decided to try and get some meat for his men and taking two local guides after a walk of 5 miles came across four Oryx and two Lechwe grazing in a valley, but was unable to stalk close enough to get a decent shot.

On their return to the village he found a large pig tied to his tent that had been provided by the chief. While the pig was cooking Johnston entertained the villagers with “Way down the Swanee river” on his cornet, but there was such a rush of visitors that he thought his tent would be torn down and closed the entertainment with the national anthem bringing the concert to a close.

Next morning as they prepared to set off chief Cipopa came to ask if Johnston would help free his son who was a captive of a king whose ecountry they would be passing through. Johnston promised to do his best to set the boy free and they parted good friends.

Here Johnston found it necessary to comment on the characteristics necessary to be a missionary: “A special fitness or adaptability is required of the man who would be a pioneer of missions in Africa; he must possess indomitable zeal, strong, unwavering faith, good education, sound judgment, practical common sense, ready wit, and tact in dealing with the natives—in a word, every inch “a man.” We have already met too many namby-pamby, useless volunteers posing as missionaries in this country; wasting time and money, accomplishing nothing…We cannot see eye to eye with those who advocate the sending out of young unmarried ladies to Central Africa, except to well-established stations, their position being so misunderstood by the natives.” He has similar views on the subject of sending out young, trained nurses: “They soon discover, however, that the domestic arrangements of the native hut offer no facilities for the services of a trained nurse.”

Soon they arrived at Okambokoakwe village and “in the afternoon Cipi himself put in an appearance, his face and body streaked all over with the fetish white clay, as a protection against the evil spells he feared might possess him in our camp. My pombeiros could not coax him to come nearer than twenty yards of where I was seated; and having occasion to rise from my chair, he jumped up, dropped his blanket, and would have escaped, but that the crowd around him was too dense. He kept looking about in the most uneasy and suspicious manner, as if dreading some impending danger.” However before the meeting ended: “Cipi joined his people in a great hand-clapping, with shouts of ewa, ewa (”yes, yes”) and forthwith about a hundred and fifty of his soldiers executed a war-dance for my special benefit and before we parted Cipi and I were the best of friends.”

A group of Ganguellian natives; note the elaborate hair-style of the woman in the centre

Having crossed the Kukema river they were now in the Ganguella country with an entirely new language. Johnston writes: “As they are too independent a people to engage as carriers, and seldom cross the Kukema on the west or the Kwanza on the east, their supply of cloth is very scanty, their clothing being confined to a bit of leopard or antelope skin. Few amulets, anklets, or other adornments are worn, but their heads displayed the prevailing fashion and there the skill of the native tonsorial artist is exhibited.”

So intricate and fanciful are some of the patterns that they must be seen to readily understand what they are like. In some cases, the decorations are all on one side of the head where the hair is allowed to grow long for the barber’s manipulations; the other side is shaved…there are dudes who spent an hour or two everyday in the hands of the hairdresser…The head arrangements of the women are not a whit behind the men in grotesqueness of style or design, but they spend less time over it, one great dressing sufficing for months and even years; plaits with three or four white or red beads strung on the end of each, rolls, horns, screws large and small, according to taste, with cowry shells woven in, as fancy may suggest.”

“Almost every one of my carriers and head men have their favourite charm suspended by a string around the neck or waist, in the form of sundry bits of wood, points of horns, shells, or an assortment of such knick-knacks as have passed through the hands of the fetish-doctor, with the assurance that they will ward off every ill that might otherwise befall them… All come under the name of ‘Ombanda’ - patent medicine, a panacea for every ill…When twitted about it they only laugh and say, “Ah no, we don’t expect you to believe in this; it is something beyond the intellect of a white man.”

Another march of 21 km (13 miles) brought the expedition to the Kwanza river. “Nothing remarkable by the way; in fact, so far as each day’s journey is concerned, it is only the monotonous tramp, tramp, over a rolling country, with an occasional lift in the tipoia when tired or feverish, and when there are men to spare. Now an open plain; then a small forest; anon a rivulet; rarely a river; no plants or trees that by their appearance would suggest our being in the tropics; no fruit of any kind except a nauseous sort of wild berry.”

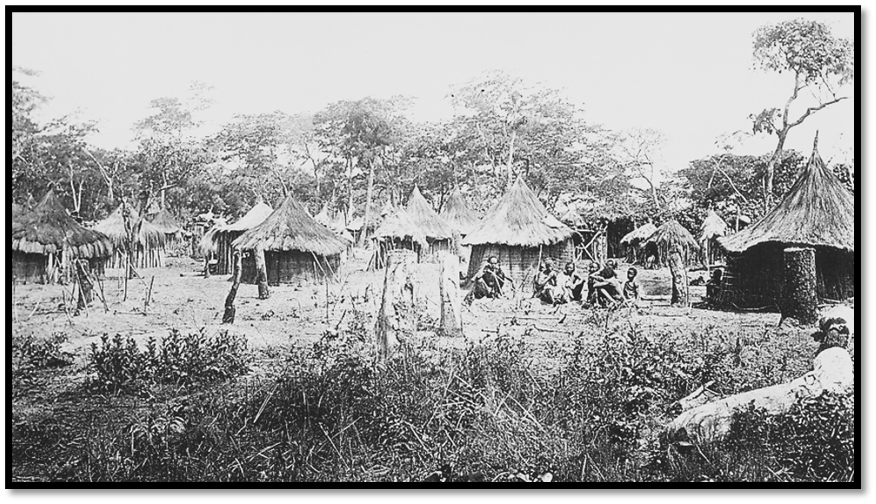

A Ganguellian village

Iron-smelting

“This district is noted for the excellence of its iron. During the coldest months of the year the miners and blacksmiths turn out and camp near the pits, working night and day until they have manufactured a supply of hoes, spear and arrow heads, axes, hatchets, knives, snuff- spoons, etc. sufficient to meet the demand. I examined several holes from which ore had been dug. They were about ten feet in diameter and eight feet deep. Close by were the small sheds, with broken clay furnaces and crucibles scattered around among the coke and slag, where the ore had been smelted and the metal transformed into implements of labour or weapons of war . The bellows or blast employed is a simple contrivance, but it serves the purpose. Those I have seen consist of two hollowed-out disks of wood, ten inches in diameter, resembling a large wooden ladle, with a tubular cylindrical handle a foot long; round the edge of the disks goatskins are bound with rawhide, forming a sack about fifteen inches long; this is gathered at the top and tied tightly round sticks, that serve as handles. The two wooden tubes are made to converge into a clay muzzle, which is connected with the fire; and by the alternate and rapid movement of the sticks a strong current of air is produced. The metal is said to be tempered by means of ox grease and salt.”

The next camp was on the bank of the river near Kongovia, the capital. Within two hours thirty huts had been built for Johnston's men. In the afternoon the chief Liwika came up with a large retinue of men who approached warily as if in doubt of their reception. A pig, three large calabashes of beer that made the eyes of his men twinkle and a basket of meal were pesented. The speeches lasted an hour and a half and by this time had made such an impression on the chief that he ordered the pig to be taken away and replaced with an ox the next day!

Next morning chief Liwika called around to say he was fetching the ox, but that as big thunder clouds were gathering would Johnston be so kind as to keep off the rain until they returned? I asked Sanambello my interpreter what they meant, but in the mean time he assured the chief the matter would have my immediate attention!

It was not until 7 October the expedition was ready to move again. Liwika’s kindness had unfortunately delayed them for three days as the beer and abundance of meat meant threats and coaxing had failed to get his men to move. By 6am they were all at the Kwanza’s banks, ready to be ferried across. The river is about 82 metres (90 yards) wide and 4.3 metres (14 feet) deep in the centre. Five dugout canoes manned by the chief’s men took the expedition across. Many of our men had not crossed a big river before and lay flat at the bottom of the canoe, their hands covering their faces.

Johnston watched fishermen busy with nets and lines catching some good sized fish that they killed by biting behind the head with teeth that are well adapted as they have both the upper and lower incisors filed to a V shape that fit into each other.

We soon reached Mowanda village led by chief Likalula, but on entering the village learned that he had been told some days before that a caravan led by a white man was approaching and had fled. In about an hour he appeared literally covered from head to foot with white clay, but the interview was short as he was trembling with fear. He was given a present of cloth and invited to visit the camp. The expedition had to remain for two or three days to pound maize meal for the next eight or ten marches, as there was no maize meal to be had.

A hailstorm surprise

At midday there was a strange occurrence. The temperature was 100° in the shade when suddenly it went dark and a strong wind arose followed by a shower of hail-stones, each as big as a marble, began to fall, and continued for fifteen minutes, until the ground was well covered. “Some of the carriers happened to be returning from the villages and fairly yelled as the hail peppered their naked bodies; but they did not seem much surprised, so I concluded that it was no rare occurrence here.”

11 October. They got off to a good start by daybreak with the path winding through forest before crossing an improvised bridge over the river Varia, about forty feet wide, flowing to join the Kwanza and later another stream, the Hondo, flowing in the same direction. Only one village was passed.

They stayed the night at Kwangu village. The chief had died the month before and they saw his hat, calabashes and pots piled on the grave. None of his belongings were left inside the ombala, thus removing the necessity for nocturnal visits of his spirit to claim them.

16 October. In the last five days not one village has been passed as they walked on a hot dry plain crossing the Quito stream on the 14th. Sand made it heavy going.

Crossing the Quito stream – Johnston in the foreground

17 October. Rain prevented an early start, but they soon entered forest and followed the ridge-line of a hill called Coia about 240 metres (800 feet) above the surrounding forest which stretches unbroken for as far as the eye can see. Rubber and wild honey is plentiful in these parts.

They encountered the honey-bird which on spotting humans: “hops from branch to branch, making repeated flights toward the traveller and then flying off in the direction in which it appears to wish attention attracted, with a sustained ‘chic-en, chic-en, chic-churr, churr,’ returning again and again, until its importunity is rewarded by someone accepting its invitation to follow…” An opening in the tree needs to be made and a fire to drive off the bees, then the tiny guide collects its share of the honey.

The roots of the rubber plant run along for many metres about 15 cm (6 inches) below the ground and are dug out by hoe before being beaten with wood mallets and boiled in water, when the rubber dissolves out and can be collected and formed into balls.

They camp the night at a small village called Vowelutwi-Onjamba in the midst of a sandy plain devoid of trees. There is no mud, only sand, so the style of the huts is completely different to the rest of Ganguella. Grass is tied into tight bundles and woven together in a vertical way with the eaves of the grass roofs coming down to within four feet of the ground.

18 October. As it is Sunday they rest all day, but Johnston writes: “From daylight to dark there has been nothing but noise and carousal, drinking fermented honey to excess.”

Vowelutwi-Onjamba to the hunter’s paradise

19 October. After walking for 30 minutes they came across three native caravans going inland for rubber. The headmen said they had been waiting two days to travel with them as there were rumours of war inland. Their numbers were now 500 persons, the route very hilly and with few villages. The hard marches beginning to tell on Johnston. The scarcity of carriers had meant he had left many supplies behind, such as condensed milk and flour. Breakfast was a cup of coffee, lunch comprised a cup of hot cocoa with a couple of crackers, dinner was porridge with wild honey and tea.

Although still in Ganguella country with the same language, the men are smaller with wispy beards and long hair in plaits, much greased, but not cut or carved as is the general custom.

They are now in the Kwangu district and mealie meal is getting scarce. They cross the Kwangu river that rises in a nearby swamp and flows south-east to the Chobe river.

24 October. For two days they follow the north bank of the Kwangu and spot several herds of buffalo, but as there is little vegetation, they are also spotted and the animals move away. The temperature is 105° at midday; several carriers sunk up to their waists in black, foul-smelling mud wading through a swamp.

26 October. “We were unceremoniously driven out of camp this morning, long before daybreak, by an army of soldier or driver ants . They swarmed into every hut in millions—no mean foe to the naked carriers, and from which there is no escape but in flight…We see them frequently in the path hurrying along in close phalanx, flanked by their generals and officers on either side, attacking viciously everything animate or inanimate that comes in their way. They are dreaded and given a wide berth by both man and beast.” Monsieur Coillard, who studied these ants in the Barotse Valley says: “To coat a man with grease, tie him hand and foot, and throw him as a prey to these implacable carnivora, is a favourite form of execution resorted to by the Marotsi when they desire to specially torture their victim.”

They are now travelling southeast, the Kwangu on our left. “We met a party of natives, several of whom had received spear and arrow wounds while defending their ivory from an attack made by the tribe among whom we intend to camp to-night, at Cinjinji. They warned us to go no farther as the savages were gathered in great force and were getting ready for us; that our little band would only be a mouthful for them and so on. The Biheans were terribly scared, but we pressed on, and by noon got into the dreaded camp, so lately vacated by the unfortunate native traders.”

No sooner have they camped then a crowd of men approach: “These men are of the regular Ganguellian type, but evidently in a very bad humour, and, being elated by success in their last fight, seem eager for another. Taking precaution to repair the temporary stockade around the camp, I served out cartridges, gunpowder and lead and ordered every man who carried a gun to have it by him in case of an attack.

Mean time the natives were disappearing in twos and threes until we were alone. Now we feared the worst. ‘They have gone for their weapons’ said Sanambello. His surmise was correct, for in less than an hour, over 200 men, armed with bows and arrows, spears and hatchets, came dancing inside the stockade and halted at my tent door, where I was sitting mending my shoes. Their gesticulations and bawling beggar description, but I went on with my work, until several spears came so uncomfortably near my face that I jumped up, drew my revolver (a regulation 450) While Sanambello remarked, ‘now see how the white man's guns shoot!’ I fired several shots at the tree a few yards off and as the bullets made the bark fly they were silent and drew back a little. Then, taking a Winchester, I fired half a dozen rounds as quickly as I could over their heads and paused, telling Sanambello to let them know that I was not halfway through yet and that they should have the remaining shots unless they cleared out of my camp forthwith. The words were scarcely uttered before they made off, tumbling over one another in their haste to get at a safe distance from such infernal machines. My men, fairly yelled and roared with laughter when the bloodless battle was ended and the warriors had fled.” They were now in danger of a night attack, so Sanambello was given a piece of coloured calico and a jack-knife for the chief with a message to say that nobody would be hurt if they came in a respectful and proper manner to the camp for peace talks. This was accepted by the chief who sent presents of rubber, mealie meal and chickens and said he wished for peace.

They next arrived at Kangamba where the natives were also in sulky mood but did not seem so keen for a fight as the Cinjinjis, but just in case fresh thorn bush was added to the skerm and sentries mounted against surprise attack. They are expert basket-makers and some beautiful specimens were seen, perfectly water-tight, the smaller sizes being used as drinking-vessels. Trade goods in demand here include iron and copper wire for anklets and armlets, red white-eye beads, gunpowder, salt and tobacco which is mostly used as snuff by both men and women.

The expedition at Kangamba

Smoking in Africa

Johnston says smoking assumes many forms in Africa. A few carry their own individual pipe, but usually they share one, each tribe having its own peculiar style. The San twist a tobacco leaf into a cone and fill it with crushed tobacco which they light with a fire coal and suck from the small end, passing it to their neighbour after two or three whiffs.

Others mix some earth with saliva and mould it into a bowl with an opening at one side which is then dried by the fire and smoked by passing a long hollow reed through the hole. All natives take the smoke right into their lungs and seem to enjoy the fits of coughing that follow.

The most common form is an eland or kudu horn with a hole cut halfway between the base and the point. A reed is inserted through the hole with a clay bowl at the end into which tobacco or cannabis is filled. Water is then poured in until it rises above the node and the mouth placed over the open base of the horn.

29 October. The chief appeared dressed in leopard skins with a large band of followers armed with assegais. Johnston buckled on his revolver and ordered them to leave their weapons outside if they wished to talk. The chief became much more civil and after a blanket and some cloth were exchanged for a goat, mealie meal and beer, they parted friends.

Their route along the Kwangu river now turns more south and the countryside has more vegetation and game is more plentiful, mostly herds of buffalo and antelope, but always in the open, where the lack of cover means they cannot be stalked.

They arrive at Metua district, but now build a skerm of thorn bushes around each camp, not only as a protection against wild animals, but also from hostile tribes.

2 November. Johnston has his first attack of African fever. “I got into camp very exhausted, and sat by the fire for some time, feeling chilly, then sought warmth in my tent, wrapping myself in several blankets; but the ague took hold of me in earnest and continued until near midnight, while my mind was harassed by the saddest thoughts and most melancholy forebodings. This was followed by the hot stage, finding relief only in the next stage, when perspiration began to flow copiously and continued until daybreak.”

At breakfast he has coffee before sounding the bugle and rousing the camp and feeling very weak and shaky. Gyp, his dog refuses her food and looks like she will go no further. He is very upset, she has been good company, running along at his heels all day and watching the loads at night.

They meet a caravan of mixed-race Portuguese coming from Barotse laden with rubber and over 100 ivory tusks and 240 cattle. It has been 24 days since they crossed the Zambezi river as they had to follow the windings of the stream to allow the cattle to feed.

By 7am they enter jungle, the path is hardly visible and the foliage wet from rain the night before, so all are soon drenched. At midday they are halted by a swamp from where the Kusivi river rises.

4 November. The expedition reaches Kalumbwi and stops for two days to prepare meal as only jungle lies ahead. The men have managed to borrow only one wooden mortar, so several of them cut down a tree with a thick, soft yielding bark 20 – 25 cm (8 – 10 inches) in diameter. A log about 106 cm (3½ feet) is cut and they fold back the bark as in rolling up a sleeve. The wood is carefully squared off, leaving a smooth surface and the bark returned to its original position. Next a stick 122 – 150 (4 - 5 feet) in length is peeled and the ends rounded and a very serviceable mortar and pestle is ready for use.

Cloth is in little demand among them. But an empty jam or sardine tin, or better still, a brass cartridge shell, which they use as snuff boxes, will buy a basket of manioc meal.

The chief of Kalumbwi paid a visit with a tremendous crowd of followers and said that as Johnston was the first white man he had met he would send his people that night to honour him. About 11am over two hundred men and women arrived with five big drums and danced until 8am and came and said they would repeat it the next night if given a little salt!

9 November. The carriers are saying they require additional pay before they will move and are promised additional cloth as well as beads. They leave skirting the swamps along the Kusivi river, his two Jamaicans are struggling with fever.

The rain becomes heavy and orders are given for the men to build huts. The swamps stretch for half a mile either side of the river and maize is grown in the reddish soil. Villages are built in their centre to protect their crops from raiders. The huts are built on piles 180 – 240 cm (6 – 8 feet) high with the threat of flooding and a ladder to reach the platform that can be drawn up at night.

14 November. It has rained heavily the past four days and this morning two headmen came to say that the men had said unless Johnston can stop the rain they will stay in camp. In a few minutes it stopped – the men lifted their loads and said he had done well, but within an hour it was coming down in torrents! For the rest of the day, he was in the whole caravan’s bad books! For three days they have seen no natives or villages.

Next day they marched about 21 km (13 miles) until they reached the Cikulwi river. Being 11 metres (35 feet) wide and 2.4 metres (8 feet) deep they had to camp for the night and next day built a rough trestle bridge, which although shaky, served its purpose. Two tree trunks with forked ends were placed on each bank and where they met over the bed of the river lashed together with bark. A few poles were forced into the mud to act a supports and short pieces of wood, ladder fashion, fixed as footholds.

Although the caravan crossed the river, the swampy ground made the going difficult with the carriers often sinking to their waists in the mud with some needing rescuing. The Kambuli river was crossed, 11 metres (20 yards) wide, but only knee deep, before they reached Kalongo.

16 November. On the march today they “passed the grave of a French man, enclosed by a palisade. He had been killed by an onyani (wild ox) He had fired on the animal, but only wounded it and before he could reload, it charged and gored him.” They are now out of Ganguella country and on the southern border of Lovale. “The landscape is beautiful, rich green grass covering the plains. Still no sign of natives or villages, for which I am rather thankful, as the men make longer marches and travel better when there are no attractions by the way and they know there is no chance of replenishing their meal bags.”

Johnston keeps a sharp lookout for a shot at an antelope or a buffalo, as it is now nearly two weeks that he has eaten oatmeal; even the wild honey is finished. Still, he is thankful to be in very fair health, with the exception of a peculiar vertigo that troubles him every morning, but which passes away after walking a few miles.

He writes: “I was informed by those who are supposed to know, that five weeks at most would see us at the Barotse. Had we made the journey in that time, there would have been no lack of food; but nine weeks have passed since we left Cisamba and we are still, I believe , two weeks from the Zambesi. One cannot calculate upon time while having to depend for the conveyance of loads on such fellows as the Biheans.”

November 19th. They are seeing much more wildlife now, several herds of antelope, eland, hartebeest, onyani and the fresh spoor of elephants and where they have torn up a number of young trees and strewn the ground with broken branches. “A buffalo that was gambolling about on the plain as we passed charged the rear of the straggling caravan and although most of the men were armed they threw down their guns and loads and hid in the bush.”

“While threading my way through the thicket I almost stepped on a huge iguana[ix] that was lying right across the path; it made off and scrambled up a tree, when I brought it down with my rifle. It measured 130 cm (four feet three inches) from tip to tip. I preserved the skin and the carriers begged the flesh, considering it a great delicacy.”

23 November. They spent three days in camp at Kalungalunga village and then only 10 km (6 miles) to Wanambuka where the carriers said they must stop because there was plenty of dried fish.

24 November. Heavy rain, but the carriers no longer believe Johnston can control the weather. “We have a carrier in our company named Cirula, who the Ovimbundu believe possesses wonderful power over the elements and by 6am he was out shouting to the clouds and whistling to the rain, while he burned a fetish powder which he carried with him. After a great effort and much hard work he succeeded in stopping the rain at the hour named so we struck camp.”

25 November. With game abundant, he decides to start out half an hour ahead of his noisy carriers. Accompanied by two headmen, they have just entered the forest when he saw two cows and a bull hartebeest grazing about 450 metres (500 yards) away. Creeping on all fours, he was within 270 metres (300 yards) when the bull got his scent. He fired his express and hit the bull in the chest. By the time they had skinned and cut up the carcass, the carriers had arrived. The meat was tender and delicious, a great windfall. He kept a small portion for himself and distributed the rest amongst the carriers, but there was no expression of thanks, “only a growl that I had not shot two instead of one.”

Johnston is clearly weary by now as he states: “Anyone coming to this country to labour in Christian work must be content to look for his own encouragement or reward from some other source than from the people he comes to benefit for the white man, to them, is only a present-giving animal, or an object to be plundered. Respect being gauged by the amount of stuff he distributes, if he has none to give he is despised, and becomes the subject of their sneers and contempt.”

Notes

[i] The Cazengo was sunk by the German U-boat, U91, under the command of Captain Von Glasenapp between 15th September and the end of October 1918. U91 sailed from Heligoland to the Hebrides then down the coasts of France and Spain and returned to Germany through the Pentland Firth. During this mission, it hunted down and sank twelve vessels; some of which were from neutral countries. They included the small French sailing vessels Therese et Marth, Ave Maris Stella, Maria Emmanuel, Maja and the Pierre, as well as Spanish steamer Mercedes, the Portuguese steamer Cazengo, the Norwegian steamer Luksefjell, and the 1,963 ton S.S. Heathpark, which was carrying iron ore from Bilbao to Maryport in Cumbria.

[ii] per capita

[iii] now Bié Province in central Angola

[iv] Novo Rodondo is now named Sumbe, a coastal port 200 km north of Benguela

[v] The account published in Echoes of Service, a magazine produced to publish letters from independent missionaries working in the field.

[vi] Frederick Stanley Arnot (1854 – 1914) a Scottish missionary, author of Missionary Travels in Central Africa published by Echoes of Service in 1914

[vii] The Nordenfelt gun was a multiple-barrel gun that had a row of up to twelve barrels.

[viii] A sling, sometimes called a machilla, with bearers carrying a pole that supports a hammock

[ix] Probably a Nile monitor (Varanus niloticus) or leguaan

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: