Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo, Manyanga or Mambo Hills

- This battle broke up the unity and organisation of the amaNdebele forces in the north-east who had threatened Bulawayo since the outbreak of the Matabele rebellion or Umvukela. After the battle the main body of fighters managed to escape from Ntaba zika Mambo to the Matobo hills. Ranger argues that after the death of King Lobengula in 1894 the leadership of the amaNdebele was disorganized, however the Mwari cult shrines at Matonjeni, Njelele, Mangwe and Ntaba zika Mambo managed to unite the amaNdebele and elements of Shona and Rozvi in an attack on the Europeans.

- Stent the Times correspondent says that the sight of the dead soldiers being buried after the battle persuaded Rhodes to seize the first chance of starting peace negotiations as he realised the Matobo hills presented a much tougher nut to crack and were held by amaNdebele forces still fresh and confident. However because the military and the local Europeans were hostile to any negotiations his initial attempts to make contact had to be done in some secrecy.

- Plumer used his flanking forces effectively at Ntaba zika Mambo, initiating the fighting with the night march commencing Saturday 4 July which caught the amaNdebele completely by surprise and Plumer’s deployment of cavalry and infantry was sound – the fact that they were not as effective as planned is testimony to the good fighting qualities of the amaNdebele who managed to delay and hold them back. Plumer would find that this tactic was not available in the Matobo…each kopje would need to be stormed one by one to force the amaNdebele into a stand-up fight.

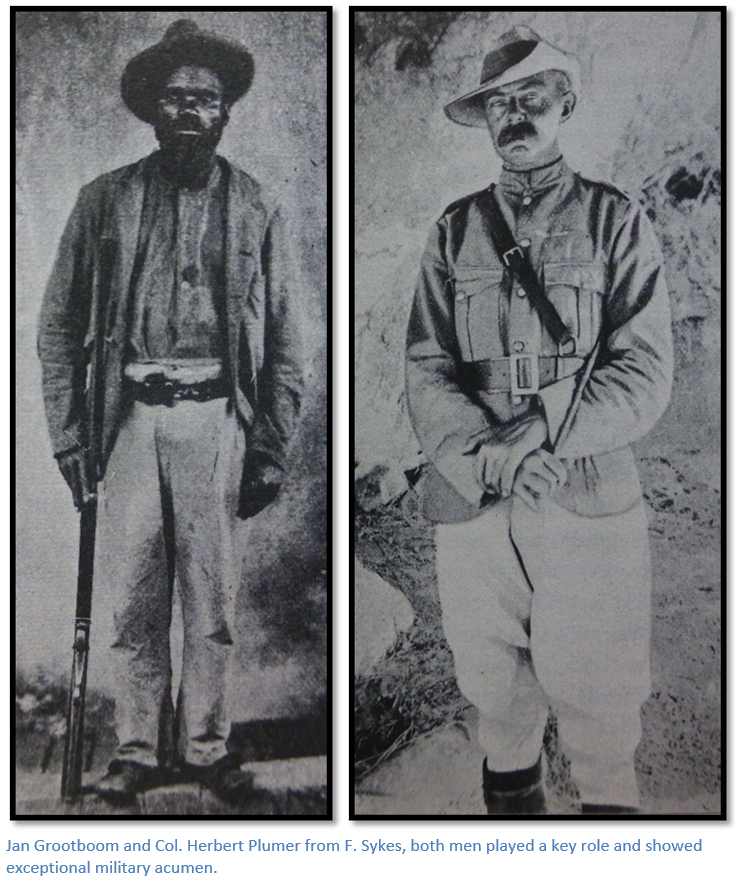

- Colonel Plumer who directed operations at Ntaba zika Mambo had an illustrious military career. He was assistant military assistant in the Cape in 1895 before being sent to command the Matabeleland Relief Force in 1896 before General Frederick Carrington arrived to take overall command along with his Chief of Staff, Colonel Baden-Powell. Plumer returned to Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1899 where he raised a force of mounted infantry and led them at the Siege of Mafeking during the Second Boer War. His extraordinary military ability led to his promotion by WWI to Field-Marshall and he distinguished himself at Ypres and in June 1917 won an overwhelming victory over the German Army at the Battle of Messines, which started with the simultaneous explosion of a series of mines containing 455 tonnes of ammonal explosives placed by the Royal Engineer's tunnelling companies beneath German lines, which created nineteen large craters and killed ten thousand German soldiers.

- Plumer’s tactics and organisational abilities and military discipline were key to the battle. Amongst the first orders were that clemency was to be shown to the wounded and that anyone surrendering should be taken prisoner. At morning assembly the positions and duties of each unit for the current day were carefully explained. His only real mistake was to assume, based on his local informants, that the amaNdebele would break north towards the Shangani River; in fact the bulk of the warriors moved south after the battle to the Matobo hills.

See directions under the separate articles on Manyanga (formerly Ntaba zika Mambo) Monument ruins and the Mambo Rebellion Memorial on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

I am advised by a prominent local historian that any potential visitors need to be VERY aware of local sensitivities when visiting the area which is a highly politicised place with competing groups fighting for control with even a visiting NMMZ inspection team being stoned by local people.

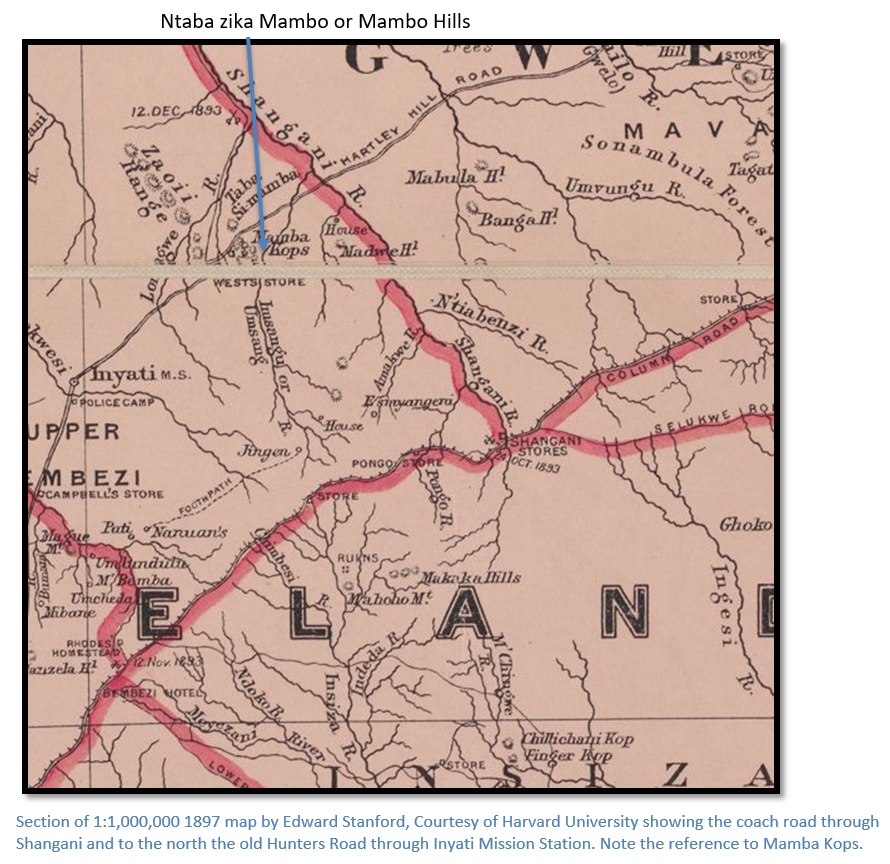

West’s Store GPS location: 19°31´34"S 29°01´56"E

In addition to the above names, the battle is also called Thabas Amamba, or Thabas a Mambo, Thaba-zaka-Mambo and by Plumer Thabas-i-Mhamba

Background to Ntaba zika Mambo

This article considers the sacred shrine site to the north-east of Bulawayo that is also known as Ntaba zika Mambo, or Manyanga and occupies an area about seven kilometres east to west and five kilometres north to south. It does not consider the causes of the Matabele Rebellion, or Umvukela or any of the other political and amaNdebele state issues which were important to its outcome.

Following the decline of the Great Zimbabwe State the site at Ntaba zika Mambo developed as a religious and spiritual centre of the Mwali cult in the period of the Torwa State and continued under Rozvi Changamire rule until finally defeated by Mzilikazi’s amaNdebele armies in the late 1830s. However the religious importance of the local oracular shrines at Njelele, Matonjeni, Mangwe and Ntaba zika Mambo was not reduced as both Mzilikazi and later Lobengula insisted that Mwali, the bringer of rain, be respected for their rain making powers with the iwosana praying and dancing for rain and being allowed to collect gifts from the people in return. Mwali was manifested in the human form as the Mlimo, or M'limo, or Umlimo

In 1890, the Mwali shrines in the Matobo and at Ntaba zika Mambo had advised Lobengula to avoid bloodshed with the Europeans, but after Lobengula’s death as their social and political importance grew, their feelings seem to have changed. Many reasons for the amaNdebele grievances have been put forward including the loss of land and cattle, the demand for labour reinforced through the native commissioners and native police, the rinderpest, swarms of locusts and failing crops through drought and this may have persuaded Mwali to change their attitude toward the Europeans.

Marieke Clarke in her booklet Mambo Hills: Historical and Religious Significance provides a refreshing insight into the religious and spiritual significance of Mkwati Ncube and his wife Tenkela. Clarke points out that Tenkela was probably of ‘higher birth’ and greater significance at the time than her husband and that relatively little is known of Mkwati in comparison with the Shona spirit mediums Nehanda and Kaguvi. She says Mkwati was not local, being born in the Zambezi Valley and caught in his youth by amaNdebele raiders who rose to importance through his marriage to Tenkela, the all-important iwosana, messenger of Mwali. From Ntaba zika Mambo he acted as the local voice and transmitter of information for the Mlimo Cult and in time developed as a regional instigator of the March 1896 rebellion or Umvukela in Matabeleland.

Mkwati and Tenkela made Ntaba zika Mambo into the dominant Mwari shrine and worked closely with other spirit mediums, in particular, Siginyamatshe, a prominent Mwari messenger who lived close to Bulawayo and with the amaNdebele military forces including Mpotshwana and his Nyamandhlovu regiment, Mtini and his Ngnoba regiment, Nkomo and his Jingeni forces.

Soon after the Umvukela began Mkwati advised the appointment of a male spirit medium in Mashonaland to supplement the female spirit medium Nehanda, to liaise with the Mwali shrine cult in Matabeleland. In Mashonaland there was a system of spirit mediums dominated by Chaminuka and Nehanda, but the Chaminuka spirit medium Pasipamire had been killed by the amaNdebele in 1883 and there had been no replacement. In north-east and central Mashonaland Nehanda provided the religious lead; but on Mkwati’s appeal for a male spirit medium Chief Mashayamombe appointed Gumboreshumba, who came from the Hartley and Charter District and was related to the national spirit medium Chaminuka, as Kaguvi’s spirit medium. Here on the Mupfure River near Mashayamombe’s kraal, the spirit medium of Kaguvi through Gumboreshumba received the messengers of all the Chief’s in Mashonaland and co-ordinated plans for the First Chimurenga in Mashonaland.

Terrence Ranger informs in Revolt in Southern Rhodesia, 1896-7: a study in African resistance that there was no active Mashona uprising in Mashonaland until June 1896 upon the return of a mission to Mlimo Mkwati at Ntaba zika Mambo comprising Chief Mashayamombe’s representatives, Bonda, a descendant of the last Rozvi Mambo and Tshiwa, a Rozvi spirit medium. They were accompanied back to Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal by a small party of amaNdebele fighters; whereupon plans for a coordinated uprising took place with the trusted headman, or sons, of many of the central Shona Chiefs.

Clarke shows how the Mwali shrines in the Mambo hills encouraged revolt with several of its key characters actively involved, and after the Imperial Forces captured the oracular caves of the Mambo hills on 5th July 1896, from which the Mwali voice had spoken, they discovered large quantities of loot taken from killed settlers which had been brought as tribute to the Mlimo.

Preliminary skirmishes in Matabeleland

Shortly after Sir Frederick Carrington arrived to take command of the Matabele Relief Force on 2 June 1896, Col. Herbert Plumer was asked to clear the amaNdebele from around the Umguza and Khami Rivers. Plumer’s force moved out of Bulawayo on the 24th April and parallel to them moved a column from the Bulawayo Field Force (BFF) together with Gifford’s Horse and Colenbrander’s men under the command of Major Watts. At 2:30am they rode into a large amaNdebele force concealed in a well-concealed ambush that made a brave and determined stand but were silenced under the withering of the Maxim gun. A further encounter at 8am on a series of thickly wooded ridges took place until the amaNdebele broke off the action.

On the 5th June a patrol under Col. Spreckley was preparing to leave Bulawayo to build forts at Shiloh and Inyati when Sir Charles Metcalfe and the Scout Burnham reported seeing a large amaNdebele force on the Umguza River at the ford where it was crossed by the Salisbury road, just 10 kilometres from town. Colonel Spreckley was ordered to attack with 200 mounted men including Grey’s Scouts, Capt. Van Niekerk’s Afrikaners, Brand’s men, some of Selous troop and 3 guns. Near the Umguza they met up with Beal’s Salisbury contingent and soon after at the Umguza River met 1,000 amaNdebele in fairly open country. The mounted men spread out into open line formation and charged; the amaNdebele fired a volley and fled, but many, especially the older and less fleet warriors, were chased down and shot in considerable numbers. This regiment then retreated to the Mambo Hills very much disillusioned in the abilities of the Mlimo who had promised that once the white men crossed the Umguza River: “the Mlimo will strike them all blind, and you will then be able to kill them without trouble. And then go and murder all the women and children in Bulawayo.”

During the first week of June a number of patrols scoured the countryside surrounding Bulawayo to ensure there were no opposition forces. Col. Plumer with 600 men went down the Khami River as far as its junction with the Gwaai, Captain Macfarlane with 400 men accompanied by Rhodes and Sir Charles Metcalfe down the Umguza River. Neither patrol encountered any opposition with Plumer’s forces returning to Bulawayo on 24th June and Macfarlane returning in early July.

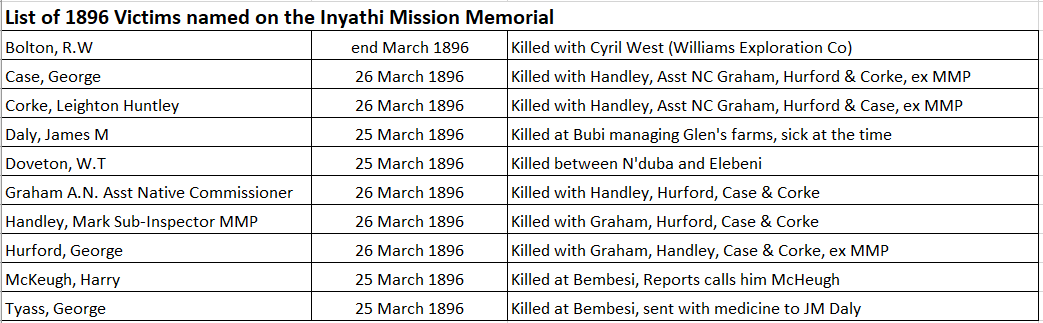

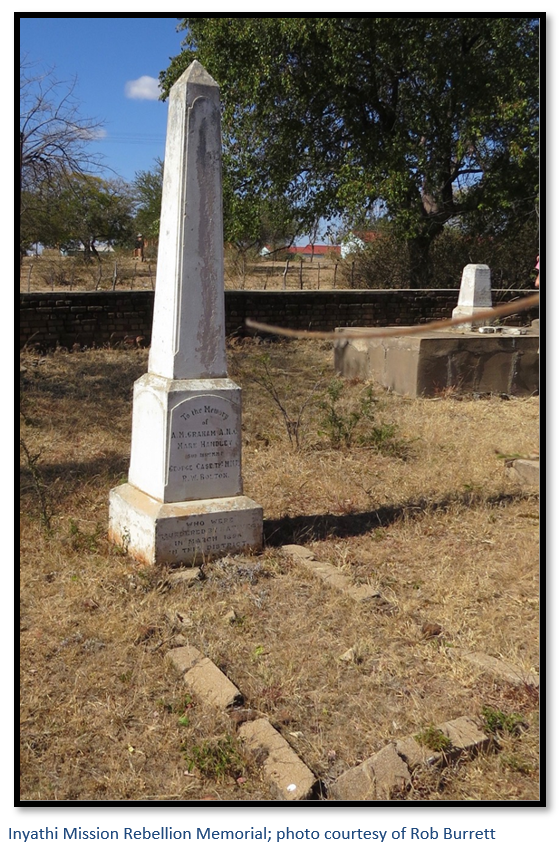

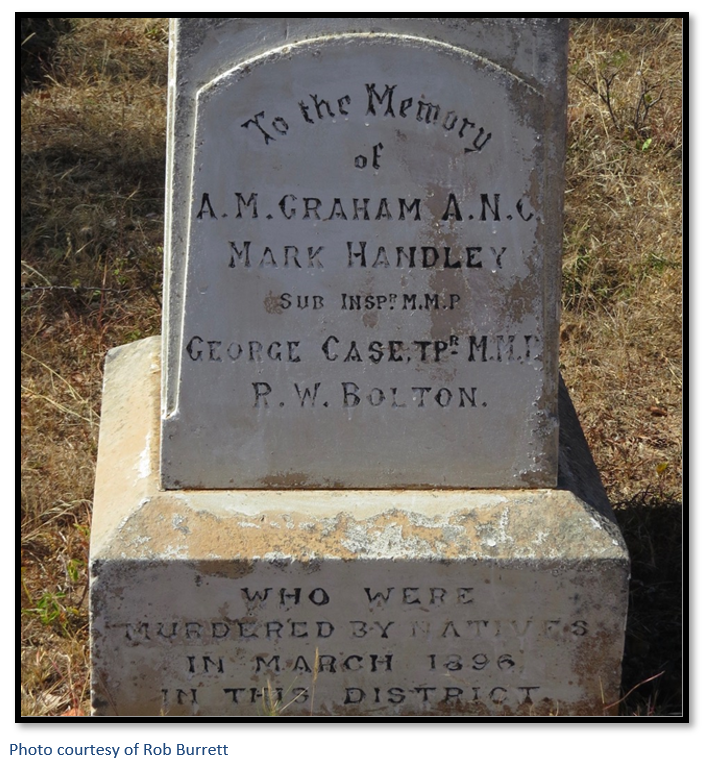

Casualties at Inyati Mission

One of the early patrols from Bulawayo made up of Captain Pittendrigh with ten members of the Afrikander Corps had left Bulawayo on Saturday 28 March to reinforce a small party at Jenkin’s store and then to relieve Assistant Native Commissioner Graham and Sub-Inspector Hanley and five other men at Inyati Mission. The small patrol fought a series of running battles with the amaNdebele who numbered in their hundreds and only escaped on a number of occasions because they were mounted on horseback. At Campbell’s Store they learnt from a miner named Patrick Madden that those at Inyati had been attacked on the Friday night and all killed, except for Madden and another miner named Tim Donovan and a colonial native; although Donovan was killed during the escape.

News of amaNdebele forces concentrated at Ntaba zika Mambo

News was received from Mr Gilgund, the Native Commissioner at Inyati that the amaNdebele Impis had retreated onto the Ntaba zika Mambo or Mambo Hills area about 80 kilometres north east from Bulawayo and beyond Inyati Mission with large numbers of cattle and supplies. The fighters were heavily armed with smooth-bore black-powder elephant guns and Tower-muskets, Winchester repeater rifles and Lee-Metfords. Ranger tells us that also gathered there were the spiritual leaders of the revolt; Mkwati, Tenkela, Siginyamatshe and many other minor officials and messengers of the Mwali cult as well as the military commanders and Nyamanda, one of the claimants for King.

Major-General Carrington gave Colonel Herbert Plumber orders to take a column through Inyati to clear the area of the amaNdebele. Plumer says their boots needed replacement and their clothing looked tattered; and there were questions about the Armour canned beef supplied by Lieut-Col. Bridge, responsible for transport and supplies, as it had been rescued from Fort Tuli where it been since 1890 and had been used to revet the interior parapets of the fort. However, it was found that although the tins were covered in mud and discoloured their contents were still fit for eating.

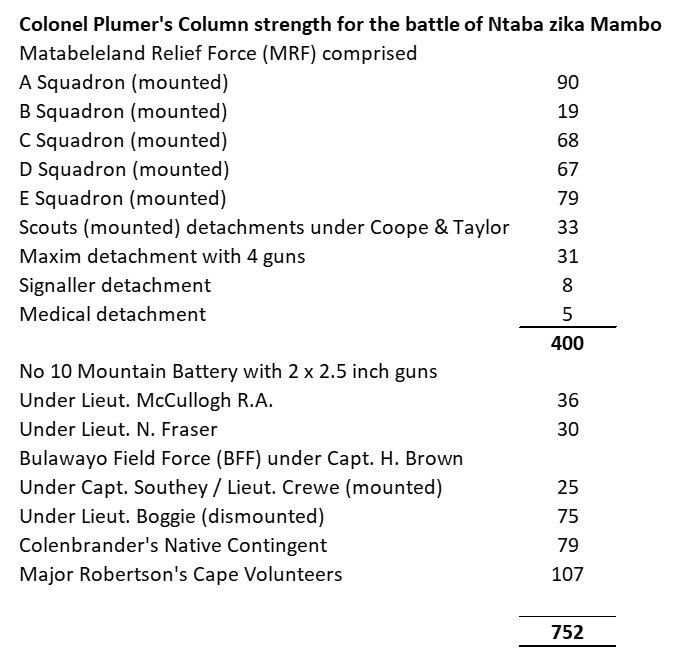

The entire Matabeleland Relief Force (MRF) were assigned this task, except about 50 men who were left at Khami Fort and 100 under Major Watts who were sent to Mashonaland. This was a considerable force of men and equipment, by far the largest seen so far in Rhodesia. Significantly this action meant that for the amaNdebele forces the uprising had shifted from an offensive into a defensive action and their fight was now one of survival that would be conducted from the rugged hills of the Matobo and Mambo hills.

They had 480 horses, 280 mules and 22 wagons to transport kit, provisions and ammunition. Twenty days rations were taken with 200 rounds per man and a large ammunition reserve. Plumer writes that the Cape Volunteers were well drilled but had no scabbards or belts and so always marched with their bayonets fixed to their rifles.

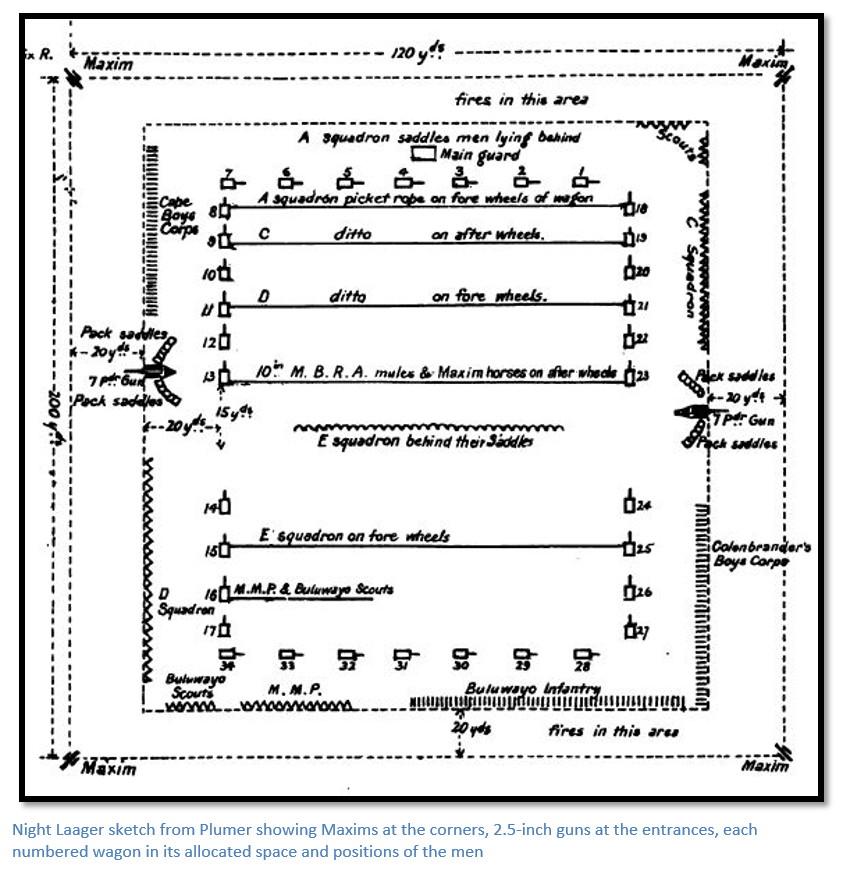

Frank Sykes says this large force brought Plumer’s great organizing abilities into full play. Practices for the formation and breaking up of the night-time laagers were carried out regularly and confusion became impossible. Every wagon had its own number and came into laager and left in strict succession and orders were issued which were followed to the letter. No off-saddling of falling out of troops was permitted until the laager was formed and the pickets were in position.

Rhodes and his brother Col. Frank Rhodes accompanied the column in a private wagon. Sykes tells the following story of a Trooper who thought Rhodes mule-wagon belonged to an itinerant hawker following the column to sell tobacco and mess extras. The Trooper hailed the wagon: “hi there, pull up” and Rhodes head appeared with the inquiry: “well, what do you want? The Trooper replied: “what have you got?” “Who is this man?” said Rhodes. The Trooper replied: “look here, have you any soap, matches, tobacco, candles?” “No” came the reply, at the same time telling the driver to go ahead. The disappointed Trooper replied: “well, a nice sort you are, I don’t think. No tobacco, no soap; what the so-and-so did you come out here for?” and with a varied assortment of curses returned to the lines.

The column left Bulawayo on 30 June taking two days to travel from Welsh Harp Farm on the Umguza River and reaching Inyati Mission on 3 July. The amaNdebele were aware of the column’s presence at Inyati and prepared to despatch the women and children and herds of cattle and sheep and property taken from killed Europeans northwards on 5 July. Plumer decided that surprise was needed for a military success and prepared his forces for a 25-kilometre night march on the Mambo Hills to be followed by a dawn surprise attack on 5 July.

Description of Ntaba zika Mambo or Mambo Hills

The Mambo Hills, or Thabas zika Mambo, is a mini version of the Matobo Hills that rises out of the Matabeleland thornveld and formed a natural fortification for its defenders with many deeply cut gorges that made any attack difficult, was a superb defensive site, and made the use of horses and artillery ineffective. Major Robertson who led the Cape Volunteers on Sunday 5 July 1896 described it as follows: “Thabas Amamba [SIC] consists of a range of hills running north and south and arising abruptly from the plain which is seen gradually ascending in an easterly direction. The range is about five miles in length. Along the western slope the face of the hills is almost precipitous, with numerous clefts and gorges’ opening to the country beyond – that is to say, to the east. The top of the range maybe described as a series of peaks, somewhat elongated in a northerly and southerly direction, having for their summits gigantic granite boulders piled on the top of each other, frequently to a height of 400 or 500 feet. Large openings between the boulders form hundreds of natural caves. The bush known as the ‘wach-een-bitje’ (wait-a-bit) thorn, and multitudes of different kinds of creepers, also of a thorny nature, grow in abundance in every nook and corner where it is possible for roots to get a holding. This description is of the western portion of the Thabas Amamba, so far as the boulders, caves, trees and shrubs are concerned, applies equally to the eastern or interior of the group of hills. Shooting out from the eastern slope of the range are numerous spurs, now descending, now ascending, and finally culminating in other hills; so that a series of minor ranges run from west to east from the main range, about seven of which extend in an easterly direction for a distance of about four and a half miles, that on the northern extremity being nearly as lofty as the main range. Towards the eastern extremity of the Thabas Amamba, the Insungu [Nsangu] River intersects the hills in a northerly and southerly direction, from which hills numerous rivulets and tributaries flow into it. Between the spurs above described there are numerous valleys, some not more than one hundred yards, others nearly a mile in width, all of them intersected with watercourses and overgrown with dense bush, with but few clearings. Towards the eastern extremity of the hills may be seen what is known as the rebel stronghold. This consists of a conical-shaped hill rising abruptly to a height of about 400 feet, and divided from the main stronghold, still further east, by a broad sandy-bedded watercourse. The stronghold itself rises out of this watercourse, with an almost precipitous face to a height of 500 to 600 feet, formed of gigantic boulders, with innumerable caves of great dimensions, and a perfect maze of thorns and shrubbery. Along the eastern base of this fastness the Insungu River is seen, enclosed by another range of lofty hills, almost as precipitous and equally as high as the stronghold itself. The whole group covers an area of some 25 square miles.”

Preliminary reconnaissance by Jan (John) Grootboom

A key military tactic used by Plumer was to use Grootboom’s talents as a spy on the positions and movements of the amaNdebele prior to making his assault. Grootboom carried out a brave and solitary reconnaissance leaving Bulawayo six days before the attack and travelling on foot to Thaba zika Mambo. During the day he laid low, only approaching the amaNdebele at night so he could listen in on their conversations and learn their locations. He told Sykes in 1897 from his home alongside Hope Fountain Mission that: “at night I went into the mountains and saw every place where the enemy was. I saw the Matabele cattle in the kraal and went up close to their scherms where they were busy cooking. At one place I could plainly hear them talking.” The amaNdebele fighting men had been “doctored” and told by the Mlimo Mkwati that the white man’s bullets would glide off them like water and the 2.5-inch gun shells would become eggs and were very surprised when so many of their number were killed on the 5 June at the Umguza River outside Bulawayo. From their conversation Grootboom heard they were back at Ntaba zika Mambo much aggrieved; their belief in the infallibility of the Mlimo now in question.

Indeed, Grey wrote to his son on 16th June saying: “the other day a strong force suddenly appeared within six miles of Bulawayo on te other side of a little stream called the Umgusa; they were told by their prophet (Mlimo) that the white man’s horses would not be able to cross the river but would fall down dead if they attempted to cross over to the other side. We thoroughly cured them of that little superstition and I only wish the other impis – of which there are several – would be similarly advised by their spiritual guides and give us an opportunity of knocking them out.”

Plumer’s Column march by night to Ntaba zika Mambo

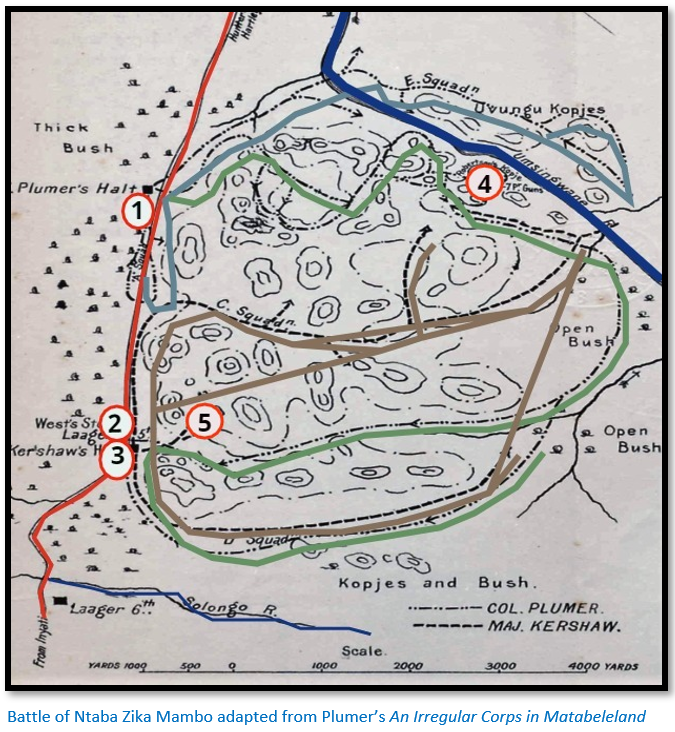

Based on Grootboom’s verbal intelligence report, which described the bulk of the amaNdebele forces as being in the north east of Ntaba zika Mambo where good water was present, the plan of attack was outlined to the officers by Col. Plumer prior to the night march of Saturday 4 July. The general plan after the initial attack was to prevent the escape of the amaNdebele into the thick bush of the north and northeast and the mounted troops would pursue any amaNdebele that broke out of the kopjes into the more open country to the south or east. However, the mounted troops did not effectively implement this manoeuvre, and this is where the great bulk of amaNdebele escaped in the aftermath of the battle.

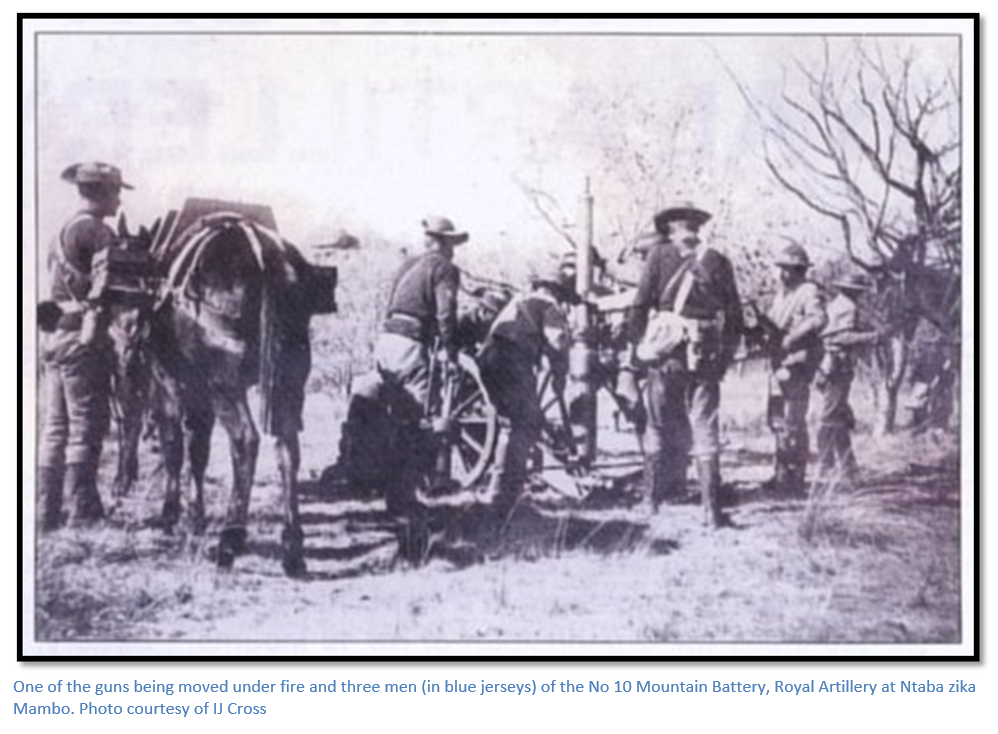

The whole column, plus thirty men from the Inyati Fort, would make a night march on Ntaba zika Mambo and attack the amaNdebele in their stronghold at dawn on Sunday 5 July 1896. All the dismounted men with one Maxim under Major Kershaw (numbering 334) would start in advance; C Squadron the dismounted Troop, the Cape Volunteers and the Mountain Battery left first at 3:30pm from Inyati Mission and at 5:30pm the remainder of the detachments and squadrons (numbering 398) with one Maxim followed behind. The ambulance and five transport wagons left at 2:00am and everyone marched in strictest silence with smoking and talking forbidden.

At the Longwe River, 20 kilometres from Inyati Mission the dismounted troops halted until the mounted troops had caught up and they left together with the Maxim guns in front and the rear, the mountain batteries in the centre and strong detachments of mounted troopers in advance and at the rear. Stent, the Times war correspondent who was with Kershaw’s flanking cavalry wrote: “all through the night we rode – a stealthy band of khaki grey intruders…the only sound which broke an otherwise dead stillness was the tramp of men and horses, the rumbling of the Maxim gun carriages, and the occasional yelp of a jackal in the distance…on toward the mountain looming indistinct before us. Then the picket fires of the rebels lifted through the cumber of the night. Men gripped their rifles, loosened a round or two in the bandoliers, and peered grimly out into the murk. Now the column broke, some to outflank the position, others to move into the heart of the enemy’s fastness. Grey dawn found us standing to our horses. In front of us a crop of isolated granite kopjes which formed the object of Plumer’s attack. Clear upon the cool wind of the morning, the wind that wakes, came the crack! Crack! of the martini’s, answering the dull heavy explosions of the old elephant guns which the Matabili carried…Out of the hills the retreating Mashonas – Mashonas inevitably lead the retreat – came streaming across our front. The machine-guns spat viciously at them as they ran. Among the hills the musketry began to babble incessantly. The dawn glowed red. The Matabili were making a stand in a central kopje – a nasty one to tackle. Suddenly just in front of us a few men that looked like a picket fired on us and bolted. The squadron trailed after them in pursuit. ”

The Tactical Plan and implementation

The plan was for the whole force to move together to the West brothers’ ransacked store a further eight kilometres on from the Longwe River, where the southern column comprising Squadrons C and D with 26 MRF dismounted men under Major Kershaw and Colenbrander’s Cape Volunteers would halt; whilst the northern column under Col. Plumer continued onto the northeast. Having cut off the amaNdebele retreat north, the plan was to use the infantry of the northern column to drive them through the kopjes to the more open south and east. The southern column would clear the southern section of the Mambo hills and drive north to meet up with the infantry. The northern column would attack at daylight at 5:30am; the southern column at 6:00am.

The march went as planned; Major Kershaw arrived at Longwe River at 8:30pm, the mounted troops at 10:15pm. At 10:45 the combined force moved on and West’s store was reached at 2:00am; the north-east end of the Mambo hills being reached at 3:15am. The columns at times passed within 150 metres of the lighted fires of the amaNdebele without the alarm being raised; a great testimony to the silence of the troops and enforcement of the ban on smoking and talking.

Battle of Ntaba zika Mambo 4 - 6 July 1896

The account of one of Alfred ‘Bulala’ Taylor’s Scouts – the first shot of the day

Before daybreak horses were saddled, and riding ahead of the column, we followed the line of hills eastward until we came to an opening in the bush to the kopje immediately in front of us. Here Captain Coope took his scouts to the left whilst Lieutenant ‘Bulala’ Taylor went away with us to the right. After watering the horses, we came across some cattle spoor, and shortly afterwards Lieut. Taylor spied a native running up the side of a kopje. He had been surprised in one of the scherms and was heading off. Taylor at once put up his rifle and fired the first shot of the day, but without drawing first blood…

From there we made straight towards the centre of the hills. Beyond seeing a number of the enemy’s scherm, which it was evident, from the lighted fires and articles lying about, they had recently deserted, we failed to discover their whereabouts, and after riding in and out amongst the kopjes, a detour was made to the open country north of the place where we had first met the enemy. On the way out, we noticed a few cattle in a scherm built of stones under a small kopje. When we got on the flats we met Captain Bowden and ‘A’ Squadron who had a large number of cattle captured from the rebels. Taylor expressed his intention of going back for the cattle seen in the scherm.

Instead of returning by the route we had just traversed, Taylor decided to take a short cut through a narrow defile between two kopjes. Bowden suggested it was not a suitable place to be in with a body of mounted men, but Taylor pooh-poohed the idea and we rode on, Bowden meanwhile going to the left with his men. There were about a dozen of us, and the nature of the place necessitated our riding in single file. When about half our number had entered the gorge, the rebels opened fire at short range, and almost immediately the word was passed that Langton was hit. Taylor, seeing the pass was impracticable, at once gave the order to retire, which however was no easy matter. Most of us dismounted, some running to assist Langton, while the rest had their hands full leading the horses and carrying the spare rifles.

Langton, who was shot through both legs, died as he was being carried out the pass...Du Preez, while in the act of carrying the wounded man, was himself shot through the leg, and had in turn to be carried away. All this was under heavy fire. Captain Bowden, on hearing the shots, returned at a gallop, and lining his men up in the open, covered the retreat of the Scouts with his rifles.”

During the engagement Trooper Hill was shot twice through the body. He lived to be taken into camp but died the same night. Corporal Bedford and Troopers Mayor and Steel were slightly wounded about the same time.

Col. Plumer says of Taylor: “Here too [at Mangwe] we were joined by Lieutenant Taylor, who owned a farm [Avoca Farm] and some property, and who offered his services. He was an excellent rifle shot, had a wonderful knowledge of the country and of the natives, and proved a most efficient leader of scouts in all our subsequent operation.”

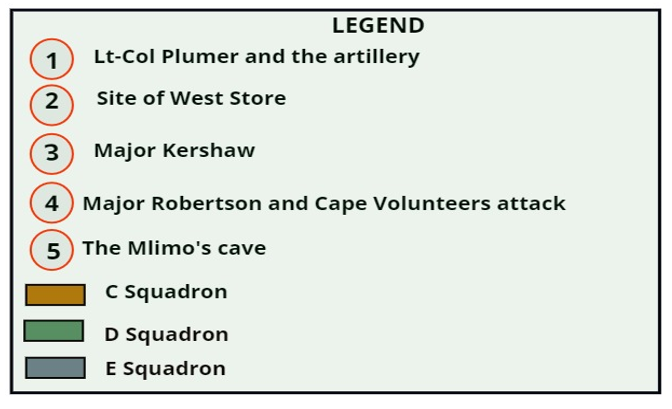

Plumer’s view of Captain Alfred James Taylor’s competence is completely contradicted by the account written above by one of Taylor’s scouts of the action at Ntaba zika Mambo on Sunday 5 July 1896 and Taylor became notorious for his actions in the second Boer War.

While serving as a captain in the War Offices's Intelligence Department, Taylor was handpicked by Lord Kitchener as liaison to the Bushveldt Carbineers (BVC) at Fort Edward in the foothills of the Zoutpansberg mountain range in Limpopo Province. South African historian Dr C.A.R. Schulenburg has described "The Irishman Taylor" as "a notorious sadist", who was "ruthless" toward white and black South Africans alike. Other accounts name him as a mass murderer, cattle rustler, war profiteer and war criminal.

In October 1901, a letter accusing Taylor and other officers of crimes against the laws and customs of war was signed by fifteen enlisted members of the Bushveldt Carbineers and mailed to the Officer Commanding at Pietersburg. In response, Taylor was arrested by Royal Military Police and put on trial at Pietersburg.

In one of the first war crimes prosecutions in British military history, Taylor stood accused of ordering the massacre of six unarmed Boer men and boys at Valdezia on 2 July 1901 and the theft of their money and livestock. Defended by Australian Army Major J.F. Thomas; Taylor was acquitted only on a technicality, whilst Lieuts. Harry “Breaker” Morant and Peter Handcock were convicted of murder and executed by firing squad on 27 February 1902. Lieut. George Witton was sentenced to life imprisonment and Lieut. Harry Picton was sentenced to be cashiered.

According to Dr C.A.R. Schulenburg, everyone involved in the Valdezia Massacre, "from Taylor right down to the Troopers who did the actual killing were exonerated, while Australians who were involved in similar episodes were court-martialled and executed. This was the first in a series of episodes which upset the Australian Government and its people; it led to a deep dissatisfaction and distrust, to say the least, of Kitchener and the British Army, which has not been fully erased to this day.”

Taylor left the British armed forces, returned to Rhodesia, served in France during WWI and died at Bulawayo on 24 October 1941. In the 1980 award-winning Australian film Breaker Morant, Taylor is portrayed onscreen by John Waters. In a review of the film, Graham Daeseler wrote; "The actual Taylor was a ruthless murderer, using the war as an excuse to plunder Boer property and line his own pockets. In the film, he is the defendants’ only ostensible ally besides their attorney. Take one look at Waters, [who played Taylor’s part] though, with that pencil-thin scar on his cheek and that haughty, dead-eyed stare, and you’ll see a glimpse of the monster lurking beneath the gentleman’s façade.”

Frank Sykes account of the battle

Frank Sykes, who was with the ambulance detachment, says they crossed the Inkwinkwisi River drift at Inyati Mission and slept until they were roused after midnight and set off with their troop of 35 men under Lieutenant Abbott maintaining an advance guard, rear guard and flanking patrols around the mule wagons. After nearly four hours of travel, it was a relief to see the dawn breaking and suddenly several rifle shots followed by the boom of the guns told them the engagement had commenced. They crossed the last drift and within 20 minutes were at West’s store. Nothing could be seen but firing in all directions told them the various detachments were hotly engaged; the wagons were drawn into laager, the horses off-saddled and tied up inside, the tripod maxim set-up and sentry posts established.

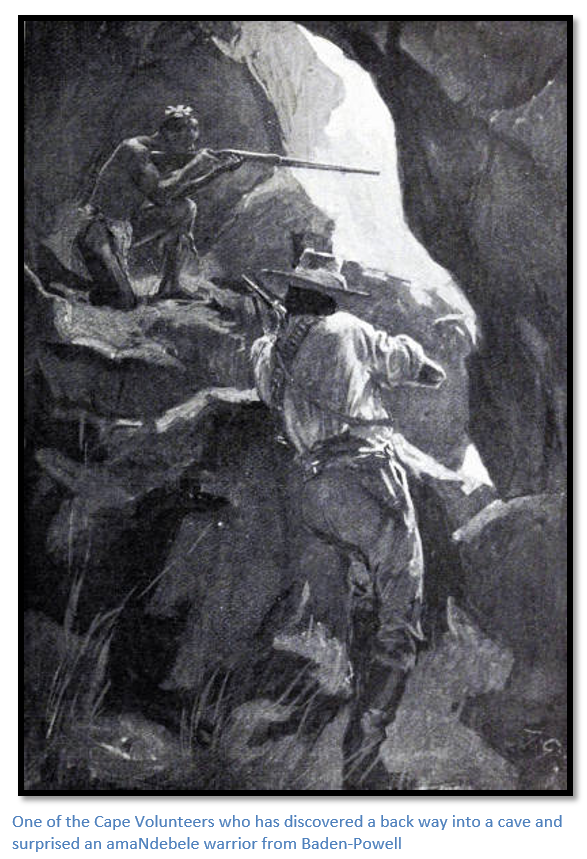

Two of the sentry posts were on rocks overlooking the laager and one of the sentries recounted: “I was detailed, with two others, to keep watch from the heights on the right front of the laager. As we followed the steep track, winding upwards amongst the boulders and bushes, a shot close behind me and ‘that’s got him’ from Sgt-Major Mallett, called our attention to the writhing figure of a native under a rock to the left. Lieutenant Oakley administered the coup de grace with a revolver bullet and on we went towards the top. In a few minutes the summit was reached. There we were posted for the day, with instructions to hold the position in case of attack as long as possible and then retire upon the laager. With this the Officer and Sgt-Major left us to our own devices...As the rifle shots rang out from the valleys and slopes, now far away in the distance, now close at hand, one was strongly reminded of a day amongst the ‘birds’ at home; but in this case the beaters were the Cape Boys and the game, human beings. Every now and then the weird howl or war-cry of the hunted resounding amongst the rocks would be borne down the wind, and white puffs of smoke would be seen issuing here and there from the rocky crevices or from behind the boulders. Further away the heavy reports of the big guns came booming and reverberating through the kopjes, followed on by a continuous rattle of musketry, telling of some hot corner where the rebels were making a stand.

As the day wore on the firing got further away, and we decided to have a prowl round amongst the rocks in our neighbourhood. Leaving one man at a post, we clambered down, and before we had gone thirty yards I noticed the colours of a blanket, deep down in a crevice in the rocks. A little further on was an opening, with a sort of cave between the boulders. I followed it to the end and there was the blanket tightly jammed tightly in. On the ledge above were an assegai, battle-axe and sandals. These I annexed, and was turning to go out, when a man behind me said, ‘I’ll have the blanket’ and started to pull at it. As he did so, up popped the head of a native, but before the latter could spring out Grant had shot him through the head. About a hundred yards further on, beyond some large boulders, we came upon a number of boxes, travelling trunks and tool-chests, all of which had been smashed upon, and most of the contents taken. Lying around were a number of letters, Christmas cards and New Year cards (one of these had on it ‘To dear mother, from Ethel’) work-boxes, axe-heads, picks and shovels. The Cape Boys had evidently been through this lot of effects, which no doubt had originally been looted by the Matabele from stores and houses in the vicinity. Taking with us a few mementoes of the place, we returned to our post, where we remained til after dark.”

An incident which might have had disastrous consequences occurred at the laager. About 1pm some figures were seen approaching through the bush and the officer in charge told the Maxim crew to standby. On came the figures, further delay might be dangerous, and the order to fire was about to be given; only then was it noticed that they were only women and children with a detachment of troopers behind them. Had the order to fire been given, the result may have been a tragedy.

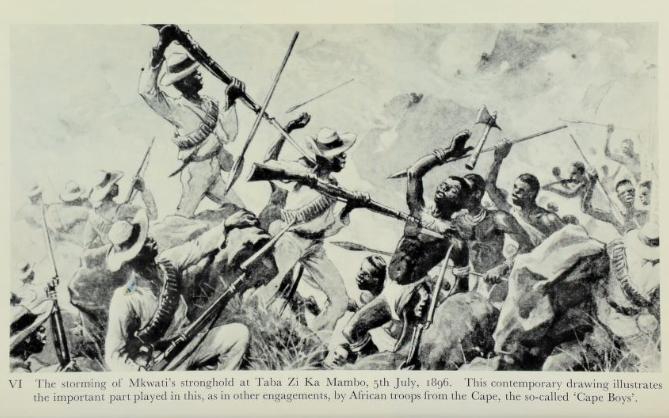

Major Robertson’s account

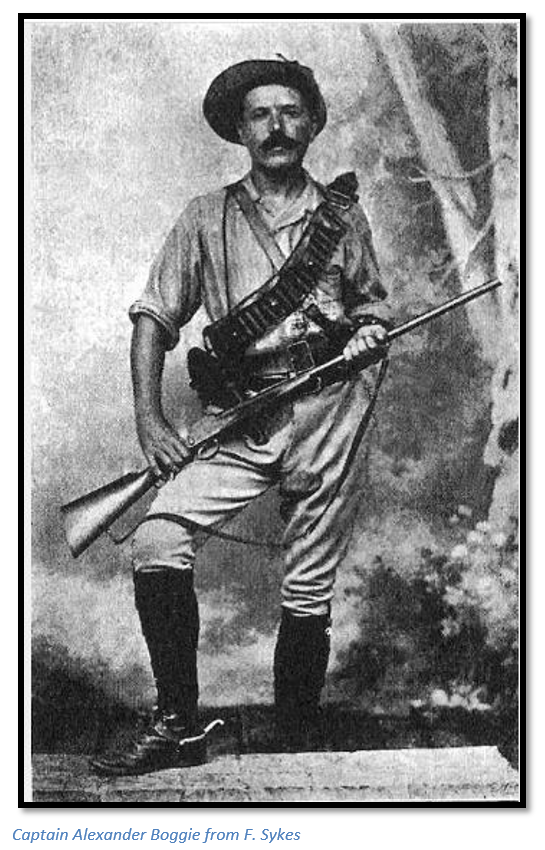

The bulk of the fighting was done by the Cape Volunteers under Major Robertson and Captain Nash; they won great respect from Plumer’s forces for their success in the bitter hand to hand fighting and forcing the amaNdebele from one stronghold after another, often at the point of a bayonet and the following is Robertson’s account: “At Thabas Amamba my corps was detailed for escort to the guns. Early in the morning, seeing the enemy on the left flank of Plumer’s march, on a few low kopjes, fifty men were directed to dislodge them.

Before this was accomplished, an additional party was sent to some kopjes on the right flank, and as Captain Boggie’s dismounted men were already engaged further to the front, Plumer directed the left wing of the Cape Boys to return. This they did, but somewhat reluctantly, as they were well in touch with the enemy. Here I sent Sergeant Blows and eight men to drive a few natives out of a small isolated kopje, which he managed to do in a most gallant manner, not only driving them out, but following them up and returning about two hours later from another direction with four hundred cattle, forty sheep and goats, and twenty-five prisoners, men and women.

Meanwhile, the guns having been in action some time on the stronghold, and a kopje on the right front of the guns having been stormed and taken by Boggie’s dismounted men, the remainder were ordered to attack the main stronghold and if possible, to carry it by storm. Captain Ross was then directed to go around the northern base of the conical hill held by Boggie’s men, with orders to rush across the open and endeavour to affect a lodgement on the stronghold. With Captain Nash and the remainder of the men I proceeded round the right of the hill, and under a very heavy fire we crossed an open sandy space, taking cover under some large boulders lying at the base of the stronghold. This was carried out simultaneously with Ross’s rush across the same waste ground under cover of the guns and the fire from the conical hill.

As soon as the storming party made its appearance, a terrific fire was opened upon it, the enemy now firing in volleys, and though the bullets were seen plunging in the sand in hundreds between the men’s feet, and in front and rear of them, strange to say not a single man was shot, and the desired shelter was reached without a casualty.

Ross’s party subsequently got about half-way up the stronghold, when they were taken in the rear as well as the front and compelled to retire.

Meanwhile the right attack was more fortunate. Foot by foot we ascended the dangerous heights, taking advantage of every cover, nook and crevice, now creeping along, now rushing across some opening between the rocks. The ascent was slowly, but surely progressing. Arrived at an opening near the summit, we made a rush into it and took the enemy by surprise. Here hand-to-hand struggles took place both in the open and in the caves where my men pursued the rebels.

One of the sergeants – Abrams – was wounded three times during the attack, but continued fighting on, whilst Trumpeter Krul received quite a score of wounds, having had a very severe time of it amongst the caves. At one time we could see him and one of the rebels locked together and rolling over and over each other. Krul’s fighting abilities however were greater than those of his opponent, who was finally run through with a bayonet. During this four and half hours fighting, there were several instances of bayonet versus assegai, the former in each case proving the superior weapon.

Captain Nash assisted me most gallantly. I personally saw him shoot four rebels, one of them a Chief, in quick succession with his revolver. It was not until the enemy had been cleared from the opening, and had taken shelter in the surrounding kopjes, that my men began to be picked off. Shots came from every conceivable direction, and I then had to select temporary shelter.

At the entrance of each of the caves I posted two men with instructions to fire at anyone approaching or attempting to escape. With the few men at my disposal I had the grass and dry reeds, of which the huts were composed, carried in armfuls, set alight, and dropped from above into the mouths of the caves. As the suffocating smoke penetrated into the recesses, there was a general rush of concealed rebels to escape, and no sooner did they appear, amidst the flames and the smoke, then they were shot down. About six hundred women and children were made prisoners; they were lodged in a place of safety during the night and were brought off at the finish. Before the smoking out of the caves was started, I sent one women into each cave to tell the women and children who might be there to come out. This they did at once.

At 2:20pm we vacated the place, with the exception of Sergeant Blows and four men, who were left to guard the entrance of the main cave, whilst we made good our return. After we had gone, it turned out that these five missed their way back, and instead of following us, went into a narrow valley, running parallel with the one we had taken. They were followed by about 150 rebels, who several times got within assegai throw, but were again and again driven off by the fire of Blows and his small party, who eventually arrived safely at laager.

Colonel Plumer assembled the force under the western slope of the conical hill on the eastern side of the range and marched homewards to laager with about 1,000 head of oxen, 2,200 goats and sheep, 400 women and a multitude of children.”

Captain W.J. Boggie’s account

“About 2am we observed the lights of the rebel advanced posts, and shortly afterwards we passed within two hundred yards of what appeared to be a long line of bivouac fires stretching about a mile along the outer face of the hills.

Every moment as we continued to advance, passing below the fires on our right, we expected to hear the whistling of bullets amongst us; but the enemy made no move, and it was indeed doubtful if they were aware of our proximity, although the noise of the gun carriages must have disturbed a few of them in their slumbers. In about an hour we passed along from south-west to north of the outposts and were soon well on the north centre of the kopjes. About four miles further back, and towards the south, near to the place where we first saw the rebel outposts, we had left a strong force of mounted and dismounted men and a Maxim, the whole under command of Major Kershaw, with instructions that he was to attack from the south as soon as dawn appeared. We now all lay down in the form of a hollow square, the mounted men tying their horses to the trees, and quietly awaited the approach of dawn, as the signal for the attack.

At dawn all stood to arms…coats and jackets were discarded, sleeves were rolled up, belts tightened, rifles, revolvers and ammunition examined. In a few minutes all was in readiness and the storming party silently advanced to the attack. Half an hour later, it was light enough to see all around, and immediately afterwards, as we entered a gorge in the hills, we became aware that the enemy had observed us, for the report of a rifle and the ping of a bullet over our heads, fired from the heights on our right, warned us that we were likely to meet with a warm reception. The shot, I think, was fired as a signal from one of the enemy’s outlooks, to let the main body know that we had entered the defile, for immediately we could hear shouting on all sides, quickly followed by a dropping fire from about 400 yards range on our right and left fronts.

We contrived, however, to go forward steadily until we could see the enemy retreating before us, and independent firing from our men now commenced. The advance was steadily continued, and as the enemy’s first lines were now within a hundred yards, we broke into a run and charged; the supporting line under Major Robertson joining forces with the first line under myself, together we rushed forward.

The enemy turned and fled, wheeling to the left, and through a beautiful shady grove, covered with fine tropical trees, pursued and pursuers dashed pell-mell in open order, our men loading and firing as they ran, the enemy endeavouring to stop the rush by occasionally turning around and firing, then dashing off faster than before. We could see the Matabele leaders urging their men to stand and shouting to them to turn and charge us with their assegais, but without effect, for I suppose the appearance of a white impi was too terrible, and no persuasion would induce even the bravest of the Matabele warriors to stand more than a second or two and face that avenging line bearing swiftly down in pursuit.

Smoke and flame and a continuous rattle of rifles heralded its approach. My men were now warming to their work and dashed on in eager haste. Dogs barked and howled, and sped madly in all directions, often biting the dust in the agony of a bullet intended for their masters. Women shrieked and clapped their hands while calling loudly on ‘Mlimo’ for protection and victory. Children yelled as mothers jostled them in hasty flight. The cattle in their kraals kept up a continuous low moaning, even the goats and sheep joined in with shrill, plaintive cries in the general medley of sounds. Heard above all the commotion was the booming of the mountain batteries, the hissing flight of projectiles overheard, followed by loud reports, echoing again and again, as the shrapnel bullets sped to their destined marks. Still the chase went on.

The enemy at last gained the shelter of their caves and rocky crevices, and as we approached saluted us with a withering fire from almost invisible cracks or apertures, thus compelling my men to take instant cover. At this stage of the engagement, the firing line, owing to the configuration of the ground, was split up into sections, resulting in a series of independent fights more or less severe as chance happened to direct. For about half an hour our northern flank continued to fight on the principle adopted by the enemy, i.e. firing from behind cover, and shooting whenever a chance opportunity occurred.

The enemy, who had suffered severely through the well-directed fire of the mountain batteries, now directed their attention to the guns, and a number of well-aimed shots came dropping among the gunners, who however taking advantage as much as possible of the cover afforded by the wheels, continued to ply their guns.

Colonel Plumer, now seeing that the supreme moment for attack had arrived, ordered the north wing of the firing line to support the guns preparatory to storming the enemy’s first position, from which place the rebels were concentrating a heavier fire than ever on the guns. To reach the mountain battery, which was occupying an elevated position on our right rear, a retrograde movement had to be made by part of the firing line, and in execution of the manoeuvre every man was for a few seconds exposed to the enemy’s fire; for whenever we came out of our shelter, a terrific volley tore through our ranks. Nevertheless, strange to relate, not a man was hit, although the bullets whistled past our ears, and embedded themselves in the earth at our feet.

By successive rushes, every man moving independently, and dodging from cover to cover, the fire-swept zone was crossed, and the attacking party reached the guns. A few minutes’ breathing time, a brief command, a rapid formation and the stormers dashed for the first position – a conical shaped rocky kopje about 200 yards distant.

Ordered to lead the storming party, I placed myself in the centre at the front of the line, giving the ‘right wing’ to Lieutenant Hunt and the left to Sergeant-Major Brooker. At a distance of about fifty yards from the kopje, I gave a signal for the usual cheer, which was at once responded to by all the line. Whether it could be called an English cheer, I did not know, but the loud rolling and hearty cheer heard on the football and cricket fields appeared to have given place to a sort of war whoop, and for a second or so a deep, revengeful yell echoed from the granite rocks on our front.

A moment later and we were in hand-to-hand conflict with our foes. The engagement was brief and decisive. A succession of rapid reports, a pattering and singing of bullets, a cracking of revolvers, a brief impression of blood-spattered rocks, wounded, dying and dead warriors, and the position was carried. We were on the top, with the enemy speeding down the far side and running across the intervening gorge or valley in order to gain the shelter of the second position. As they were clearing the open ground, we lined the ridge, and by independent firing avenged tenfold the death of our comrades, who were now lying grey and stiff on the crimson slopes.

As we were recovering our wind after the assault, the second stronghold was attacked by the Johannesburg men under Major Robertson, and I was able from my position to cover his advance by heavy fire until his men were about twenty yards off the rocks, when of course I had to sound ‘cease-fire’ lest by chance we should hit friends instead of foes. Immediately my men ceased firing, I heard the charging cheer, and saw the Cape Volunteers with their orange-coloured pugarees and swarthy faces clear the intervening space with leaps and bounds, and in a briefer space than it takes to tell, they throw themselves upon the Matabele. The intrepid Matabele warriors met the rush with superb bravery, while the Cape Volunteers dashed forward with reckless indifference to the storm of bullets, assegais and battle-axes which they encountered.

The enemy here made a long and desperate stand, fighting to the last with stubborn determination; but gradually and surely, they were driven backwards, losing position after position until the gallant Cape Volunteers gained the summit. A good many, however, never descended from out of the shade of these bullet-riddled rocks, caves and trees.

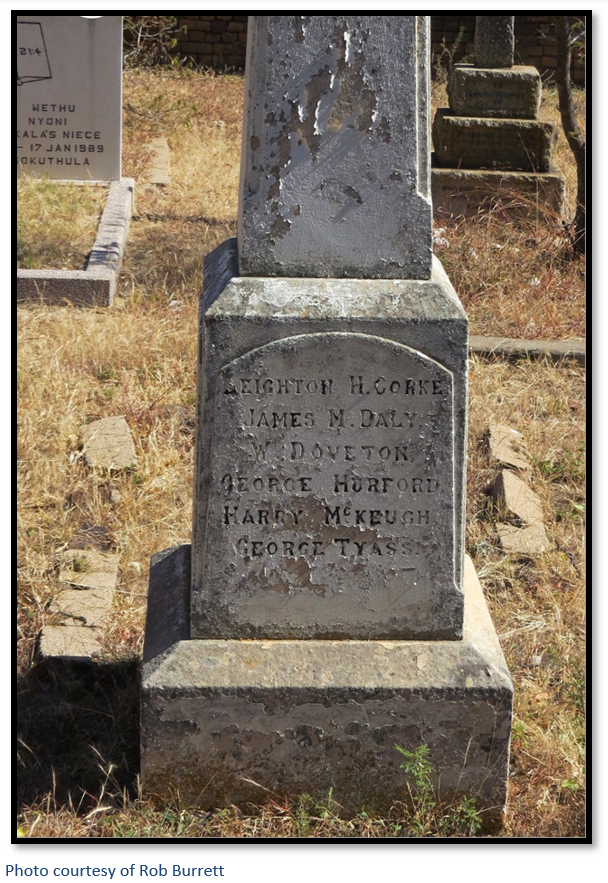

By 2pm in the afternoon, the enemy had been forced out of their strongest positions, and as it was impossible for the tired-out men to continue searching for the hiding-places of the now thoroughly demoralised rebels, the ‘assembly’ was sounded, and after a brief halt we gave the ‘soldier’s burial’ to those of our comrades who had fallen. We buried the remains of brave Trooper O’Reilly almost on the spot where he had received his death wound. Rough stretchers for the wounded were made, and they were carefully borne away from the field where they had fought so well.

As nearly all the fighting bin this engagement fell to the lot of the dismounted men, there were only about 250 men in the actual engagement. We returned to camp with a loss of twenty-five men killed and wounded, rather a heavy percentage when compared with other battles in this country. The actual number killed on the enemy’s side was probably slightly under two hundred, but quite another two hundred were most likely wounded. I consider that the enemy numbered between 1,500 and 2,000 armed men.”

RSS Baden-Powell’s account of the fight

Robert Baden-Powell “B-P” reached Bulawayo shortly after midnight on 3 June 1896 with General Sir Frederick Carrington; the 890 kilometers journey from Mafeking to Bulawayo taking twelve days in a Zeederberg coach which normally held twelve passengers internally, but because it had been contracted by the military, only held four persons.

B-P did not accompany Plumer’s column to Ntaba zika Mambo but has much praise for the Cape Volunteers who he says showed particularly pluck in storming the kopjes, and credited Major Robertson, their commandant, an old Royal Dragoon, as a wonderfully cool, keen, and fearless leader under fire.

Despite the heavy casualties of 10 killed and 13 wounded B-P considered the battle a success as the rebels lost 150 killed, and some 600 prisoners were taken, mostly women and children, 800 head of cattle, and a very large amount of goods which had been looted from stores and collected at this place as the property of the Mlimo Mkwati.

Herbert Plumer’s analysis of the battle

Plumer described the scene that greeted them as: “as a confused mass of kopjes with grassy hollows scattered among them; all the kopjes are full of caves and shelters formed among the interstices of the boulders and capable of containing many thousand people…The whole position is one of vast natural strength and capable of protracted defence.”

The northern column advanced into the kopjes at 5:30am on 5 July 1896; whilst Plumer’s mounted men moved down the east side of the Nsangu River, but the first fighting began with the scouts at 6:45am. The amaNdebele retired into high kopjes honeycombed with caves overlooking the Nsangu River from where they kept up a continuous and accurate fire. The two 2.5-inch guns opened fire but made little impression amongst the rocks. One kopje was taken by the BFF about 9:00am, with the main kopje stormed by the Cape Volunteers under Major Robertson supported by the BFF an hour later. A lot of indiscriminate firing took place until the kopjes were finally cleared about 12:00am.

Plumer wrote: “The fighting resolved itself into a series of independent actions among the kopjes and these lasted from 6am until 12 noon. The rebels fought determinedly in the kopjes but were finally driven out. Their loss is estimated at about 100.”

The mounted troops moved around the edges of the kopjes fighting skirmishes [see the Taylor account above] until Captains’ Bowden and Drury’s squadrons met on the north east and joined Col. Plumer.

The southern column under Major Kershaw advanced at 6:00am and cleared the southern kopjes without much resistance, whilst the mounted troops cut off some stragglers and they joined Col. Plumer about 11:45am.

Captain Coope’s scouts moved around to the open ground east of the Nsangu River, but their horses were too tired to follow-up the amaNdebele fighters who had retreated in this direction.

Generally, the fighting consisted of a series of independent actions by small units; most of the fighting being done by the dismounted troops in the kopjes, with the Cape Volunteers particularly distinguishing themselves in hand to hand combats within the caves.

The amaNdebele had fought determinedly and their shooting was now much more accurate. Plumer estimates their losses at around 100; in addition, they lost nearly 1,000 cattle, 2,000 sheep and goats and 5 -600 women and children were captured. AmaNdebele scouts had reported the arrival of the force at Inyati Mission; but the Induna’s had reckoned the battle would be on the 6 July; by which time the women and cattle would have been removed; but the night march and attack on the 5 July had upset their plans. Most of the surviving warriors left Ntaba zika Mambo overnight; some abandoning the war and moving northwards towards the Shangani Reserve, with the larger body making their way southwest toward their comrades in the Matobo where the focus of the war now shifted.

Eleven horses were killed and four wounded.

This was a significant loss for the Imperial forces, but the amaNdebele had used the rugged terrain and their knowledge of the Mambo hills to their great tactical advantage and forced Plumer to attack them in prepared positions.

Although Plumer had succeeded in breaking up the force that had been together since the skirmishes on the Umguza River, many of the amaNdebele forces had managed to escape. “The tracks leading from Tabas I Mamba show that a considerable number of rebels fled in a south-easterly direction towards the Matopos.”

Loot discovered

Much of the loot was discovered in a kopje opposite West’s store, including six wagons and carts, and a buggy belonging to Pascoe Grenfell from Ngwenya, which had been used to carry plunder from ransacked homes and stores. Stored away in caves were found bales of blankets, clothing, mining and provisions of all kinds. Some clothing belonging to Dr and Mrs Langford, killed near Fort Rixon, a theodolite belonging to Fitzpatrick or Edwards from Ngwenya, clothes belonging to H.E. Barnard. One man found a bundle of half-notes for £1,500 but being incomplete, they were worthless. Another found £28 in notes and gold; another found silver, but personal items included a wedding dress, a tennis racquet, a pair of dancing pumps, a Wanderers Club medal, medallions from different religious societies, clasp and carving knives, an officer’s sword, and many rifles.

The Cape Volunteers ran a high risk by going into caves looking for items of value and ignoring the possibility that the amaNdebele with their rifles were still hidden inside the caves and a number of them became casualties.

Shortly after 2pm, the ‘Assembly’ was sounded by bugle and the Troops, with the wounded and the captured cattle and the women and children started back for the overnight camp at West’s store. The wounded were carried on improvised stretchers, but there were plenty of willing hands prepared to act as bearers, Officers and men alike cheerfully volunteered to take their turn carrying the wounded. Many of the troops had to guard the women and children and cattle overnight at West’s store before being sent back next morning to Inyati mission guarded by A Squadron of the MRF and Major Robertson’s Cape Volunteers.

The bodies of Hill and Pringle were buried with military honours on Monday 6 July wrapped in the hides of some of the captured cattle that had been shot for food; Father Barthelemy reading the burial service and shortly afterwards, Colonel Plumer addressed the troops congratulating them on their success and referred to many individual acts of bravery, particularly singling out Major Robertson’s Cape Volunteers for praise. All the remaining men then searched the area for guns, grain and cattle and as the water at West’s store was insufficient, the laager moved west 1.6 kilometres away to the east bank of the Longwe Stream the same day.

Stent the Times correspondent says of Rhodes reaction to the deaths: “They were the price of victory and the price was heavy…This rough and hurried burial of the men who had given their lives for Rhodesia brought home to him, as nothing else could have done, the meaning of war – the cruel bloodiness of war.” That night as Rhodes brooded over the camp fires, “there came to him the idea of meeting the Matabili themselves, learning what they fought for and trying to bring about peace.”

Mlimo Mkwati’s cave

Capt. Vyvyan in Plumer’s book states one of the caves in the gorge behind the West’s store was believed to be where the Mlimo resided and from here he was supposed to speak through a crevice in the rock to the Induna’s gathered in an adjoining cave; it was in this adjoining cave that most of the loot was located.

B-P says: “the Mlimo’s cave was found, a most curious place, which I visited later on: a sort of anteroom in which suppliants had to wait while the priest went away to invoke the M’limo’s attention; then a narrow cleft by which they would walk deep into the rock, and which narrowed till it looked like a split just before the end of the cave. And through this crevice they made their requests and got their answer from the Mlimo. In reality, another cave entered the hill from the opposite side and led up to this same crevice, and it was by this back entrance that the priest re–entered, and, sitting in the dark corner just behind the crevice, he was able to personate an invisible deity with full effect. It was a final smash to the enemy in the north, though M’qwati [Mkwati] the local priest of the Mlimo, and M’tini, his induna, both escaped. Of such caves there are three or four about the country, where the rebels just now get their orders as to their course of action.”

This was a moment of truth for the Mlimo, the Ntaba zika Mambo shrine had been the most dominant and the most active in promoting the amaNdebele uprising and Mkwati and Mpotshwana, Mtini and Nkomo as well as minor officers of the shrine and members of the royal family left for the Somabhula forest on 4 July as Plumer’s forces marched through the night and then moved to Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal determined to carry on the struggle, Siginyamatshe stayed behind. Terrence Ranger argues that Mkwati and Kaguvi persuaded the Mashona Chiefs to fight on, but by December they moved north-east, despite Chief Mashayamombe’s protests, as part of a plan to restore the Rozvi State. Ironically, Mkwati Ncube was killed by his own followers at Umvukwes, allegedly as they did not wish for further fighting.

Return to Inyati Mission

The column started back to Inyati Mission on Tuesday 7 July; numerous horses died from their poor condition and many of the mounted men were forced to ‘foot slog’ all the way back to Bulawayo with Colonel Plumer setting a fine example by leading on foot.

Stent describes the return as completely different from the stealthy approach: “An extraordinary spectacle. First the screen of scouts, riding in a careless mood…then a great mob of cattle – ten thousand head they said; they seemed to cover the veld for miles. They suggested gigantic locusts and they were not in a hurry…Then, tramping in rough formation, the prisoners and the women and children…then our ambulances, such as they were, and the main body.”

Thanks

Rob Burrett and Rodney Tourle made useful corrections to my earlier drafts and provided photographs and helpfully marked locations as I have not yet visited the battle site.

Acknowledgements

M. Clarke. Mambo Hills: Historical and Religious Significance. Amabooks, Bulawayo, 2008

T.O. Ranger. Revolt in Southern Rhodesia. Heinemann, London, 1967

R.S. Baden-Powell. The Matabele Campaign being a Narrative of the Campaign in Suppressing the Native Rising in Matabeleland and Mashonaland 1896. Methuen & Co, London, 1901

F. Sykes. With Plumer in Matabeleland. Books of Rhodesia, Byo. 1972

O. Ransford. Bulawayo: Historic battleground of Rhodesia. A.A. Balkema Cape Town 1968

H.C.O. Plumer. An irregular Corps in Matabeleland. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Ltd, 1897

I.J. Cross. No 10 Mountain Battery, Royal Artillery in Southern Africa, 1889-1899 in the South African Military History Journal Vol 14 No 4 – December 2008

Captain Alfred James Taylor/Wikipedia

The ’96 Rebellions; BSA Company reports. Books of Rhodesia, 1975