Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings; an article on their extent and meaning

This article on Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings (often referred to in older writings as ‘ruins’) is intended to give the general reader and tourist an overview of their variety and an indication of their purpose. There are some excellent articles on recent archaeological work carried out in Zimbabwe with the authority of National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe which are based on detailed excavations and research which the interested reader should refer to.

Much of the tables and statistics below are from Roger Summers’ book Ancient Ruins and Civilisations of Southern Africa which was published in 1971. Although now 50 years old and perhaps over-preoccupied with classifications of ‘ruin-types’ it does provide a good introduction and overview of the existence, extent and complexity of the dry-stone buildings within Zimbabwe.

National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) have a much improved website (www.nmmz.co.zw) with links to many of the national monuments, regional specialist and site museums and historic buildings throughout the country. It’s well worth a visit for getting information on Zimbabwe’s dry-stone monuments and buildings.

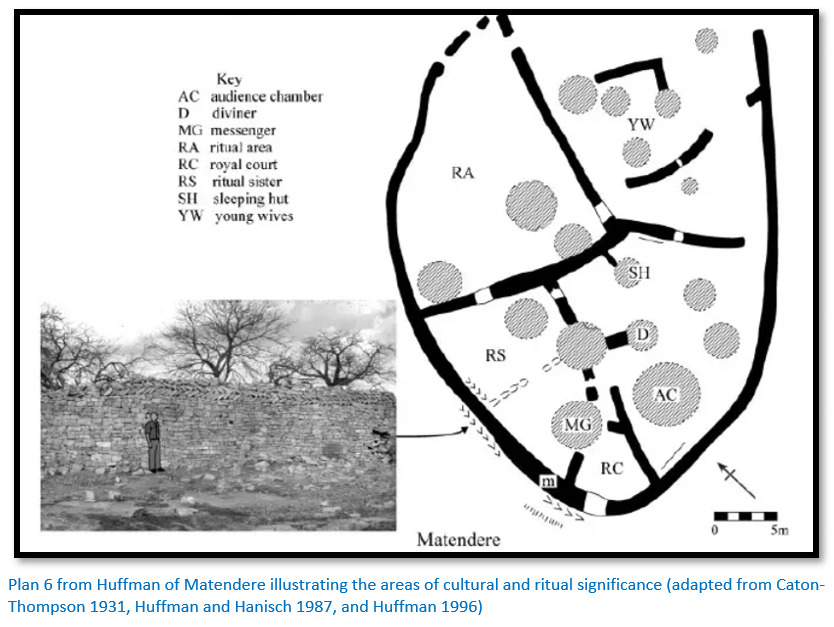

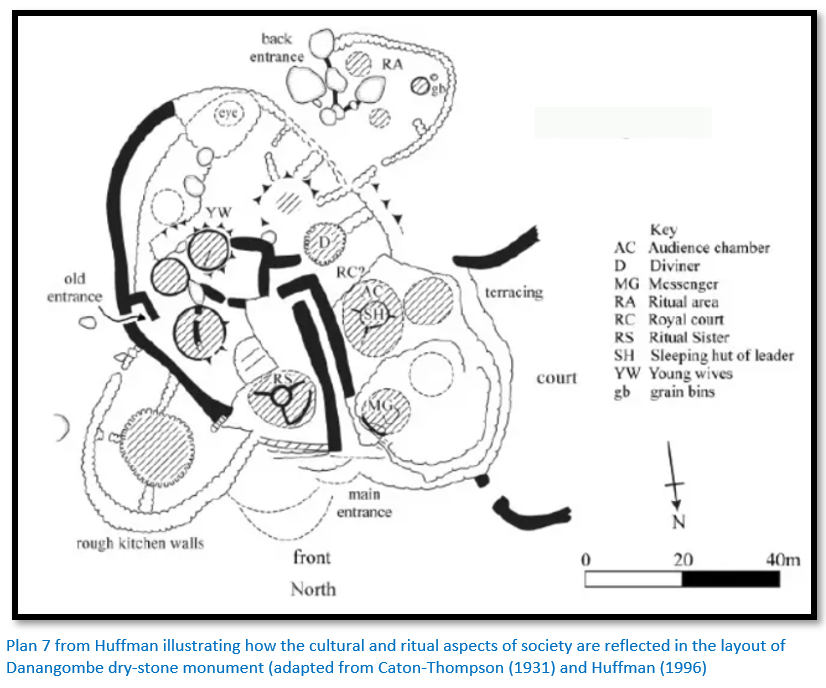

The cultural and ritual aspect of Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings is not considered in any detail, although there is an introductory section below based on Tom Huffman’s article Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture and readers who wish to explore this important aspect are advised to read this article and those by Shadreck Chirikure, Innocent Pikirayi, Gerald Mazarire, Munyaradzi Manyanga and other prominent Zimbabwean historians.

The term Zimbabwe

Dzimbahwe in the Shona language indicates the residence, court and grave of a leader. Huffman states: “An important characteristic of the new pattern was a stone-walled palace reserved for the sacred leader. Historical documents and other ethnographic evidence shows that, among associated changes in worldview, the leader became the rainmaker, and from this time on, most sacred leaders placed their palaces on top of old rainmaking hills. The most famous is Great Zimbabwe.”[i]

The name was first recorded in 1531 by Vicente Pegado, Captain of the Portuguese Garrison of Sofala who noted that: "The natives of the country call these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies 'court'". The name contains dzimba, the Shona term for "houses." Wikipedia suggests two theories for the etymology of the name. The first is that the word is derived from Dzimba-dza-mabwe, translated from the Karanga dialect of Shona as "large houses of stone," the second suggests that Zimbabwe is a contracted form of dzimba-hwe which means "venerated houses" in the Zezuru dialect of Shona, as usually applied to the houses or graves of chiefs.[ii]

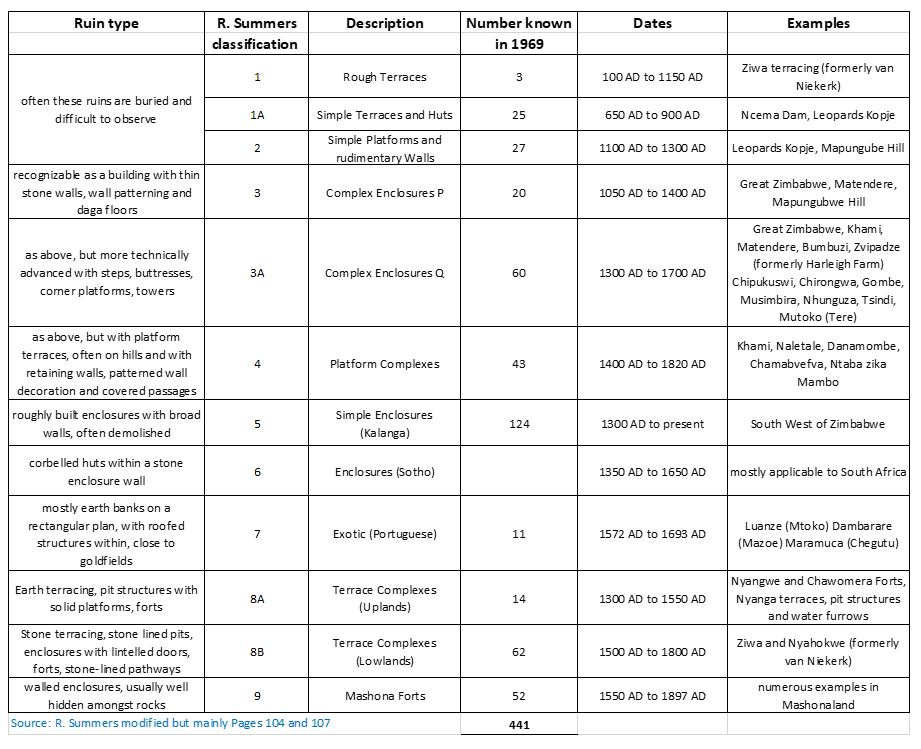

There are a large number of dry-stone buildings known as "Zimbabwe’s" in the country which are listed by broad type in the table below.

Building Types and number known in Zimbabwe in 1969

Roger Summers produced all the following information which I have incorporated into a table giving an overview of the number and classification of dry-stone buildings distributed within Zimbabwe. Of course when the builders constructed their buildings they were not constrained by current-day national boundaries and all our neighbours including Botswana, South Africa and Mozambique have hundreds if not thousands of similar dry-stone buildings.

Different types / classifications were produced by Hall (1901) Schofield (1941) Whitty (1959) Garlake (1970) and no doubt others have been produced since as archaeological work has continued. The purpose of the above is to give indicative dates, not precise ones as new information becomes known through archaeological excavation being carried out in Zimbabwe and the adjoining territories of Botswana, South Africa and Mozambique.

As Roger Summers points out, the important fact is that these dates demolish the theories about the Queen of Sheba, or King Solomon, or the Sabaeans or Phoenicians ever being the possible builders or inhabitants of any ruins within Zimbabwe.

Early Portuguese descriptions of Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings

Antonio Fernandes accounts of his journey’s from Sofala in Mozambique through Manicaland and into northern Mashonaland are amongst the earliest descriptions of present-day Zimbabwe. He was a sertanejos[iii] (backwoodsmen) and probably made two journeys into the interior between 1509 and 1512 with his reports dictated to a Sofala clerk, Gaspar Veloso consisting of lists of ‘Kings’ with the distance between them measured in days’ journey and details of whether their ‘kingdoms’ produced gold or could supply food. The Portuguese were primarily interested in the sources of gold being brought to Sofala and so his journeys concentrated on those areas with goldfields – Manica, Makaha and Mazowe. A primary object of his journey was to establish the capital of the Mutapa State which Fernandes said was in the country of Embire and that there was a fortress of “dry-stone walling.”

Soon after, Swahili traders resident in the Mutapa State began to re-direct the gold trade away from Sofala formerly part of the Kilwa Sultanate and now Portuguese-controlled and toward the northern ports of the Kilwa Sultanate.[iv] Thus, Portugal became interested in directly controlling the interior and in 1531, posts were established inland at Sena and Tete on the Zambezi, and in 1544 a station was founded at Quelimane.

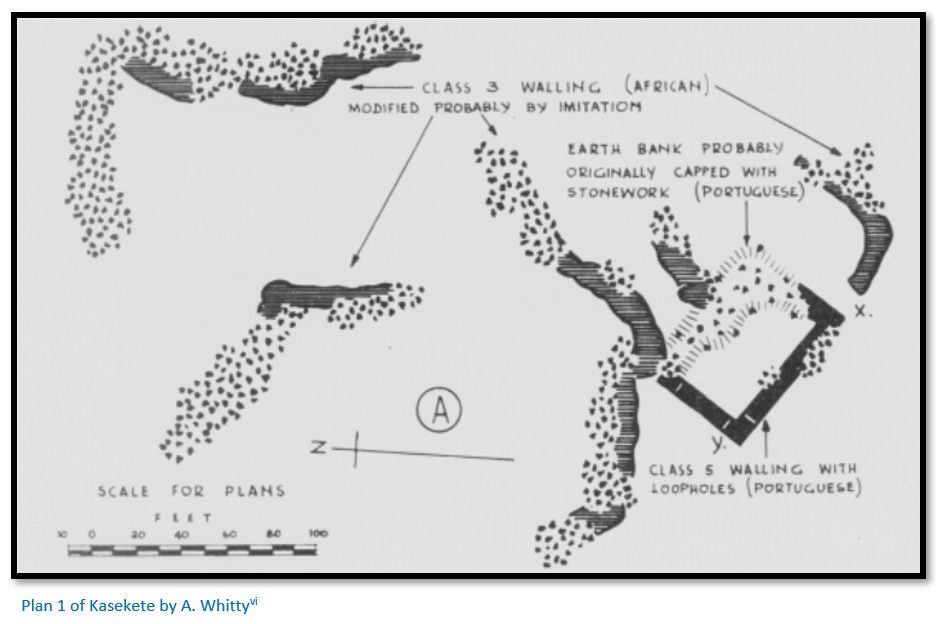

Donald Abraham[v] identified the largest dry-stone building (ruswingo in the local dialect) ruswingo we Kasekete (National Monument No 80) as Antonio Fernandes’ fortress, although there are other possible candidates such as Utete and Mutanda e Chiwawa identified by K.R. Robinson.

Within the Mutapa state, there are a number of other known ruins such as Mutota, Nowedza, Matope and others which have been associated with former Mutapa kings. However because power shifts followed succession disputes and civil wars the capital may have shifted from time to time.

João de Barros took charge of the Indian Department at Lisbon after a spell of service at a Portuguese port in present-day Ghana and had access to all the reports from India and Africa from which he compiled Da Asia. The first volume describing south-east Africa appeared in 1552 from which this famous passage is translated:[vii]

…in the midst of the plain there is a square fortress, of masonry within and without, built of stones of marvellous size, and there appears to be no mortar joining them. The wall is more than twenty-five spans in width, and the height is not so great considering the width. Above the door of this edifice is an inscription, which some Moorish merchants, learned men, who went thither, could not read, neither could they tell what the characters might be. This edifice is almost surrounded by hills, upon which are others resembling it in the fashioning of the stone and the absence of mortar and one of them is a tower more than twelve fathoms high.

The natives called all of these edifices Symbaoe, which according to their language signifies court, for every place where Benemotapa may be is so called and they say that being royal property all the king’s other dwellings have this name.

Further on, Barros writes:

When, and by whom, these edifices were raised, as the people of the land are ignorant of the art of writing, there is no record, but they say they are the work of the devil, for in comparison with their power and knowledge it does not seem possible that they should be the work of man. Some Moors who saw it, to whom Vicente Pegado (who was captain at Sofala) showed our fortress there and the work of the windows and arches, said they could not be compared with it for smoothness and perfection. The distance of this edifice from Sofala in a direct Line to the West is 170 leagues, or thereabouts, and it is between 20° and 21° south latitude. There are no ancient or modern buildings in those parts, the people being barbarians and all their houses of wood.

In the opinion of the Moors who saw it, it is very ancient and was built there to keep possession of the mines, which are very old and no gold has been extracted from them for years, because of the wars.[viii]

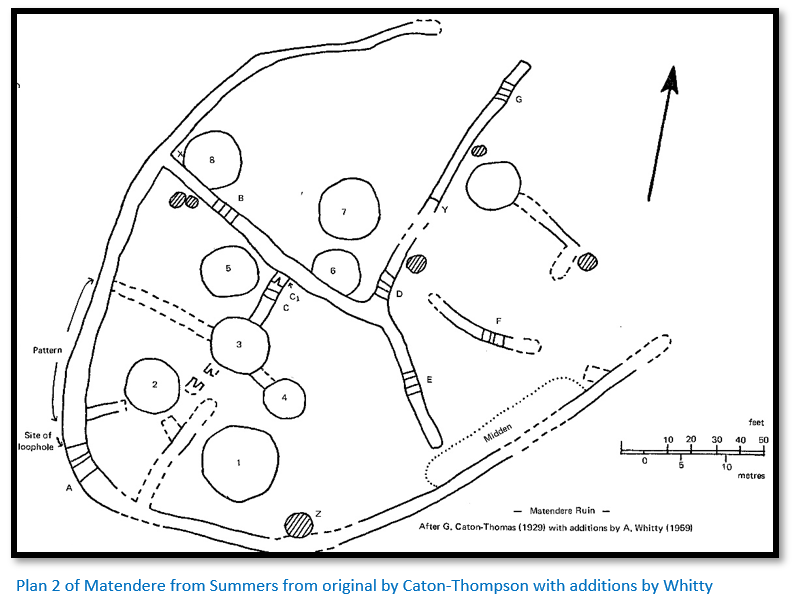

Summers believed that the most likely dry-stone building contender for the above description is Matendere [See the article Matendere Monument under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Dry-stone building types and locations

These notes are based on Summers’ descriptions from Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations of Southern Africa:

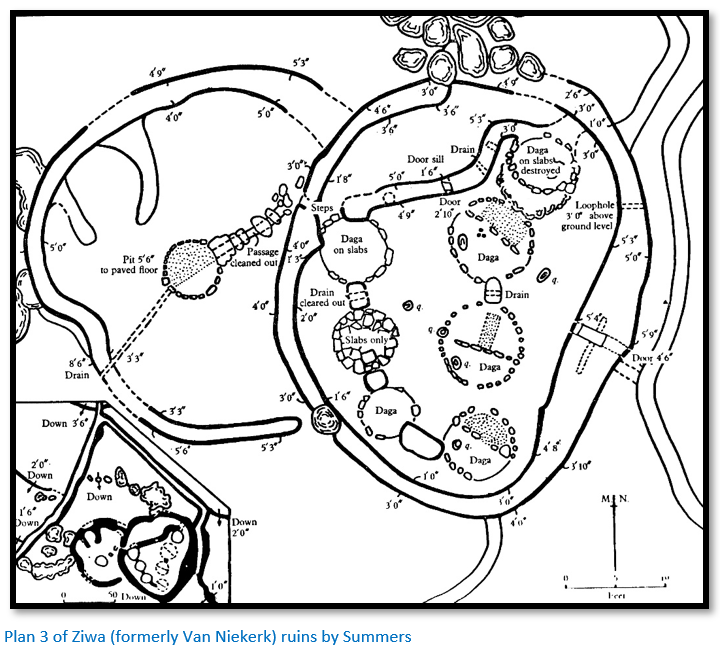

Types 1 and 1a

The walls are always built on the level with the base being broader and the top narrower, heights varying with the slope of the hillside, but the stones were not laid in any sort of course with soil being heaped up on the inside. Concentrations of type 1 are seen in Nyanga particularly around Ziwa (formerly Van Niekerk ruins) and are hard to often see as they are usually covered in thick undergrowth and Mountain Acacia (Brachystegia tamarindoides)

Type 1a is represented in Matabeleland and can be seen when the grass is short on the hill slopes near the Ncema dam, Esigodini (formerly Essexvale) and Robinson recorded examples north of Khame, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Summers states this type includes terraces, barriers for cattle enclosures and field walls.

Type 2

These comprise simple platforms with neat retaining walls and are designed to mould a hilltop into an artificial shape instead of following the natural shape of the hill. Walls are usually quite low, 50 – 80 cm but can be as high as 2 metres. The stones show an attempt to lay in courses and the artificial fill behind them may be made up of rubble, gravel, veld soil or even midden rubbish. The tops will have been smoothed off, sometimes with a dhaka clay pavement which have been compacted and smoothed flat.

The smallest platforms might be from 20 – 30 square metres but can be ten times this size and they formed the bases upon which pole and dhaka huts were built. They are found around Bulawayo but occur into Botswana and south west to the Limpopo and beyond with at least one example at Mapungubwe Hill.

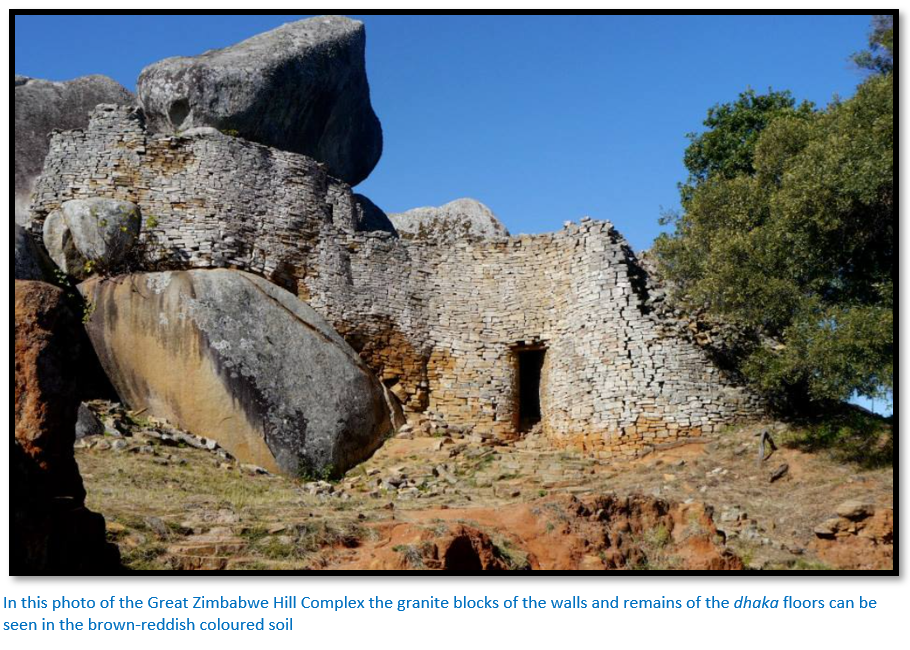

Type 3 – Style P

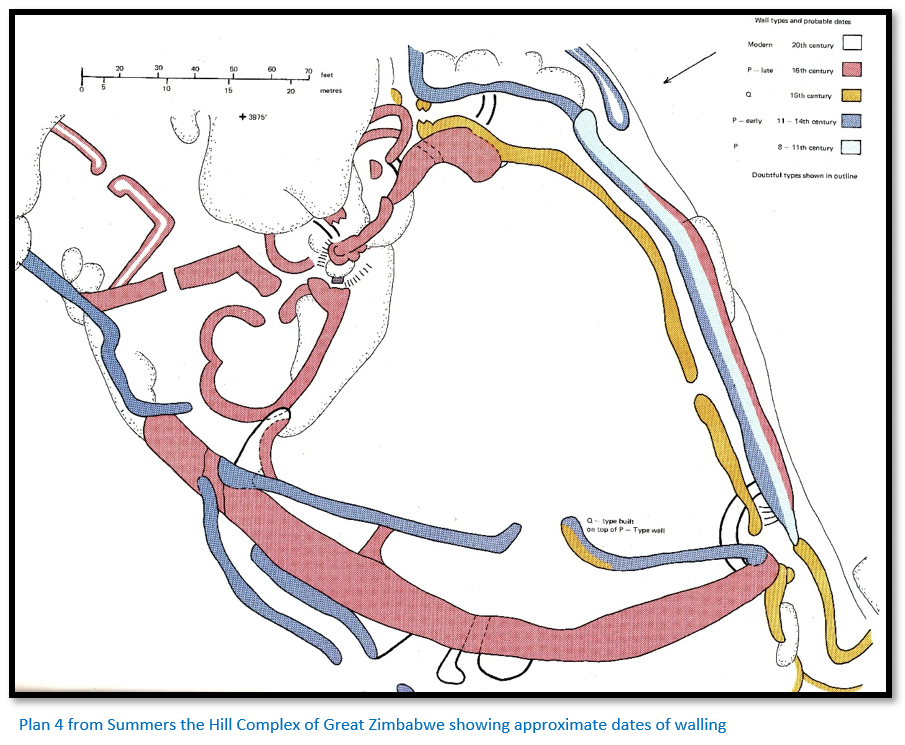

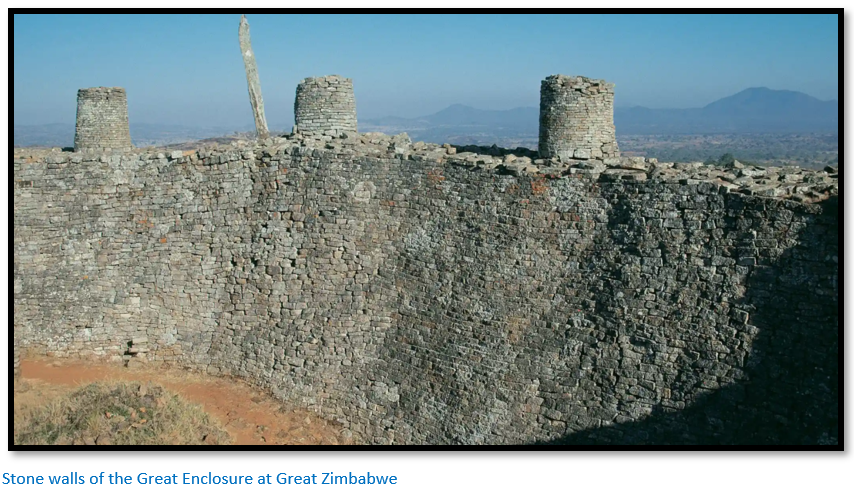

Summers states these are recognizable as buildings with free-standing walls, entrances and steps. There are examples at Great Zimbabwe (No 1 Ruin) where the stone walling blocks have been laid directly onto bare granite with the stone courses following the physical undulations of the base. In places the builders tried to correct the undulations by adding ‘false courses’ to ensure the tops of the wall were reasonably level.

The walls are neatly faced and perpendicular and quite thin in relation to their height – usually between a quarter to a third of the height and make good use of any natural boulders to save the labour of building and to buttress and strengthen the wall as in the Western Enclosure. Wall ends at doorways and entrances tend to be square in shape and un-mortared solid walls of this type easily absorb movement without collapsing. Summers gives as another example the walls on the edge of the cliff on the south side of the Hill Complex at Zimbabwe which have stood for 900 years. [See the article Great Zimbabwe, a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural site under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The walls supported the more important living quarters and storage huts which have now disappeared – Summers says they are like fossils and the hard skeletons which remain long after the soft tissue has decayed. The walls were never roofed, although clearly the pole and dhaka huts within the enclosure were roofed – Robinson thought with a dhaka dome because of the risk of fire.

Examples of this walling are found at Great Zimbabwe and Matendere.

Type 3a - Style Q

In addition to having the elements of Style P, these buildings have additional features including steps, buttresses, corner platforms, towers, standing stones on walls with high-quality dhaka filling in the interior structures. Technically more advanced than Style P, they often co-exist at the same site with many examples side-by-side as at Great Zimbabwe.

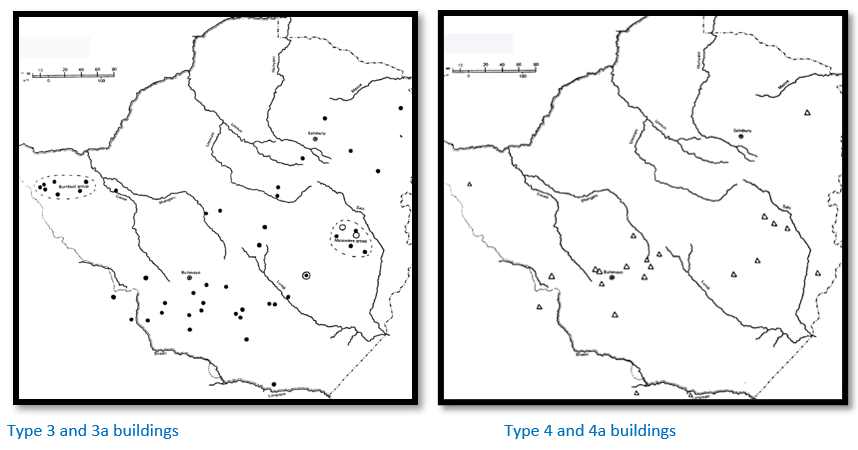

Summers agrees that many of Hall’s ‘First period’ buildings which equate with type 3 and 3a are often placed on low knolls but states further that type 3 are found on bare granite bases, whereas type 3a are usually found on veld soil. Apart from being distributed at Great Zimbabwe, Bumbusi and Matendere the distribution of these buildings is widespread in south-western Zimbabwe extending into Limpopo province.

Because of the quality of the build they have attracted more attention than any other type.

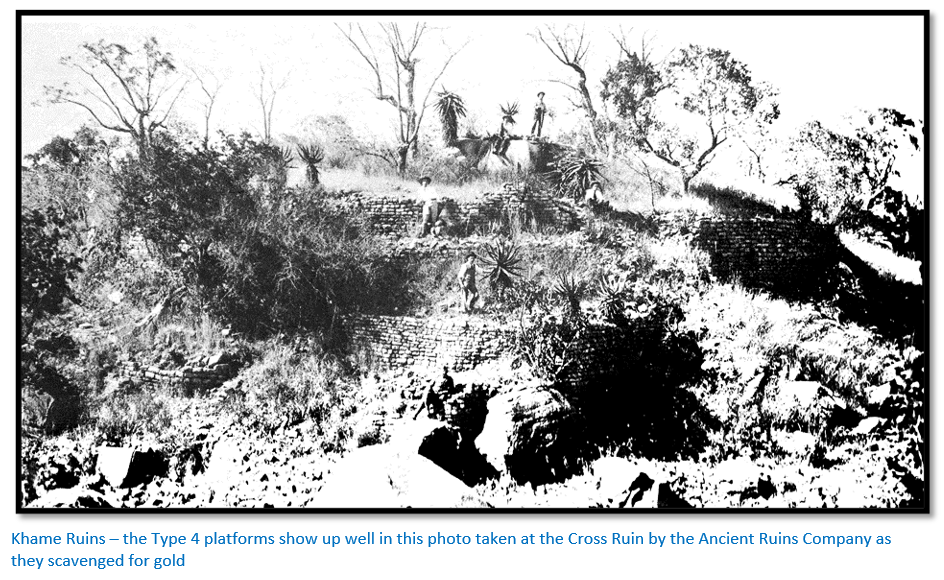

Type 4 – platform complexes

Superficially they are many similarities with Type 3 and 3a with the fundamental difference being in their construction.

They consist of large and high platforms usually built on small kopjes and often amongst large boulders. The platforms are supported by retaining walls that may be as high as 9 to 10 metres, usually built in stages about 2 metres high and stepped back giving a ‘wedding-cake’ appearance. The platform fill normally is comprised of rough rubble covered with a thick layer of gravel and dhaka. On the platforms pole and dhaka huts were constructed surrounded by low free-standing walls.

The retaining walls are built with level courses and although those with trimmed stone do not reach the standard of the best Q walls, they and the walls with untrimmed stones are superior to P style walls. There is often some wall decoration with the most common being a check pattern, but at Naletale the walls are decorated in check, dentelle, cord, herringbone and chevron using granite alternated with reddish-brown banded ironstone.

Quite long covered passages are featured often running between two platforms and some of the huts appear to have been constructed of stone covered in dhaka.

These Type 4 buildings are concentrated in the south-west of Zimbabwe, Botswana and Limpopo province with few examples in Mashonaland.

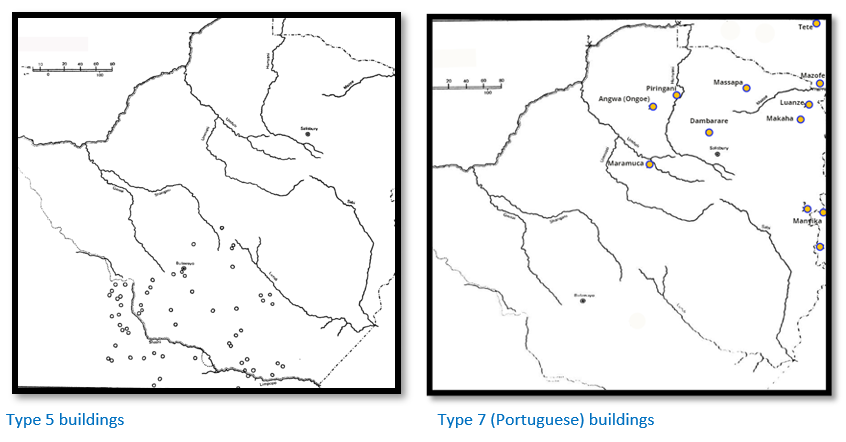

Type 5 – Kalanga and Venda buildings

Usually constructed as roughly built enclosures with generally low walls around 2 metres high and nearly as broad as they are high. The walls are often found demolished in the form of enclosures subdivided by one or more walls with the foundations of pole and dhaka huts found within the enclosures.

Again these buildings are mostly in the southwest of Zimbabwe, around Tati in Botswana and in the north of Limpopo province. Usually found on minor hillocks overlooking the surrounding country and often near water which seems to be a major factor in their sites.

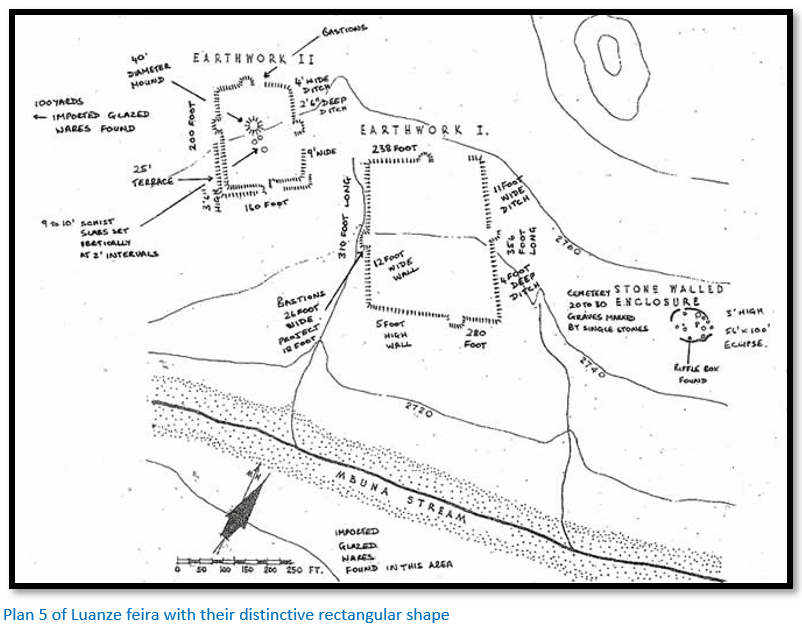

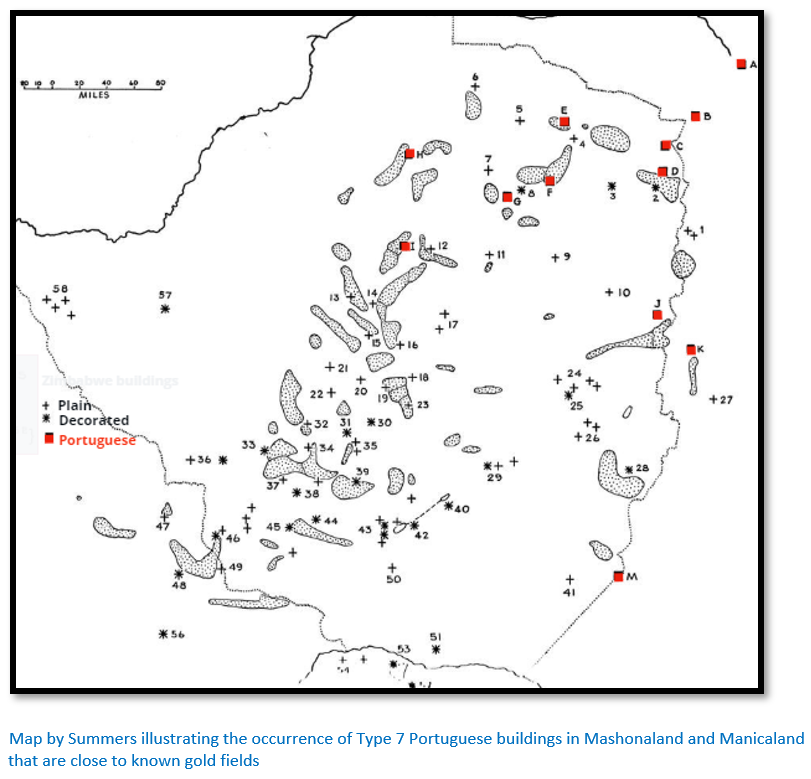

Type 7 – Portuguese buildings

The earliest Portuguese settlement was at Sofala, south of present-day Beira in 1505 on the edge of a wide estuary of the Buzi river which connected to the internal market town of Manyica and from there to the gold fields of Zimbabwe. Sofala had emerged in the tenth century as a small trading post and was gradually incorporated into the Somali trade network and Kilwa Sultanate.

Fort São Caetano was the first Portuguese fort in Mozambique and was constructed shortly after Kilwa fort. Within Zimbabwe the remains of the Portuguese settlements or feiras consist of earth banks with relics of brick or dhaka buildings except at Kasekete [See Plan 1 above] where there is a small section of walling.

Some of the feiras including the important site at Dambarare have disappeared altogether under cultivated fields, others such as Maramuca [See the article Maramuca, a Portuguese feira dating from 1660 – 1680 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

have been destroyed by artisanal gold miners. The outline of the banks at Luanze [See the article Luanze Earthworks and Church under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] are however still visible.

They are all characterised by rectangular layouts with straight earth banks and square corners which are completely different from all other indigenous building types. Local stone was quarried or collected and laid uncoursed in plain dhaka mortar with larger stones at the corners of buildings and the widths of the buildings indicate that they were all roofed with local timbers.

The feiras are all easily accessible in open ground and in the vicinity of known goldfields as trading for gold was their primary purpose. They are all, with the exception of Maramuca near the Mupfure river in the Chegutu district, sited in northern Mashonaland or Manicaland. They include the feiras of Dambarare, Luanze, Maramuca, Angwa (Ongoe) Piringani, Massapa, Bocuto, Mazofe, Makaha and Manyika.

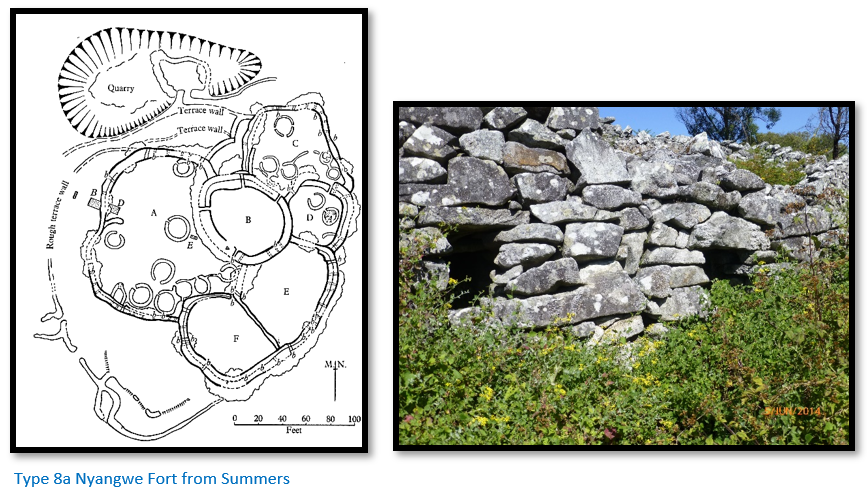

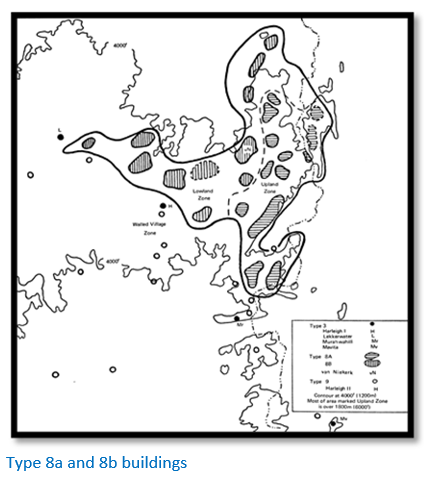

Type 8a and 8b

Summers divides Type 8a as occurring in the Nyanga mountains and Type 8b as occurring in the lowlands west of the mountains with both types within the solid line of the Nyanga district map below.

Both types share some of the same structures, namely terracing, stone-lined pit structures and hill-top strongholds. Furrows channelled water along the terraces with weirs diverting the water from their natural streams into the furrows.

Type 8a terracing often has no stone banks, being made of earth alone and may contain water furrows which Summers and other earlier archaeologists associated with irrigation. More recently Ann Kritzinger in her book Gold Mining Landscapes of Nyanga: Discovering Zimbabwe's Hidden Heritage dismissed the farming potential of these terraces and using the experience of internationally recognised mining engineers and metallurgists combined with gold geological sampling techniques to form a theory that the terraces and pit structures were part of an early pre-European gold mining process.[ix]

Type 8b terracing is normally stone-faced and are more easily seen than Type 8a. They often cover whole hillsides from base to summit with thirty or more lines of terracing. The area around Ziwa is particularly heavily terraced but a large triangular area from the foot of Nyanga Mountains as far as Headlands in the west and the Bvumba in the south has terracing. [See the article Ziwa Ruins and Site Museum under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The stone-lined and stone-floored Type 8a pit structures are surrounded by a stone-lined platform and the pit is generally accessed through a passage under the platform. On many, but not all platforms are the remains of pole and dhaka huts. [See the article Pit Structures under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Type 8b pit-structures in the lowlands to the west of the Nyanga Mountains at Ziwa for example, have many characteristics of Type 8a on the higher-ground with the platforms often extended and surrounded by an enclosure wall which may be entered through a lintelled doorway and the entrance to the pit is within the enclosure and not, as in the uplands, from outside the platform and may have a beam which slides into the wall to close off the passage.

The strongholds usually called forts are sited on the mountain tops with good all-round views. Nyangwe fort whose plan is below is a good example. Little was learned from the archaeological excavations carried out here by Hall (1904) MacIver (1905) and the Inyanga Research Fund (1951) The stones on the walls are laid without much attempt at coursing, but the entrances were built with more care to ensure the sides of the doorways are vertical and long stones of dolerite are used as lintels over the entrances.

Nearly all the walls which were originally 2.5 metres high have parapet walks and there are small holes about 30 cm across through the walls which have been called loopholes. In Hall’s 1905 plan there are fifty-eight of them, but in 1951 only fifty-one remained, so some must have collapsed. The plan is of a more or less circular enclosure surrounded by five more enclosures which were added at later dates. Summers thought E and F enclosures were added to the original B; then came A followed by D and finally C enclosure.

Type 8b strongholds are not as frequent as those in the upland zone but show signs of being more carefully built and the very thick walls of 2.5 – 3 metres do not collapse. There are parapet walls and loopholes, but they are not as common as in Type 8a. Entrance tunnels are longer with provision for poles to be pushed through the roof to prevent access.

[See the articles Nyangwe Fort and Chawomera Fort under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

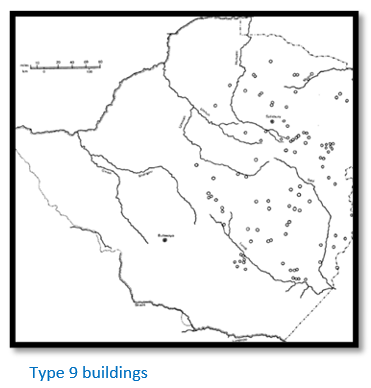

Type 9 – fortified enclosures

These stone structures are found throughout Mashonaland consisting of strong walls often built amongst the rocks and either in or at the base of kopjes. They are always well-concealed and use features such as caves or cliffs as natural aids to defence. There is always good visibility of the surrounding countryside to give the defenders early warning of the approach of any enemy.

Summers also included well-concealed caves within Type 9, such as Pomongwe in the Matobo where cattle were believed to have been hidden and which relied on their invisibility as a defence and these occur throughout Zimbabwe with the fortified enclosures covering much of the eastern half of Zimbabwe.

Cultural and Ritual aspects of Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings

This important aspect has been increasingly reviewed by modern historians such as Tom Huffman who writes: “First and foremost, ritual spaces in the elite Zimbabwe Pattern related to sacred leadership. Because these leaders claimed a special relationship to God through their royal ancestors, even political drama had a supernatural component.”[x]

The early Portuguese writers recognised the cultural and ritual importance of dry-stone buildings as Huffman quotes: “…and the amyr went into the houses of the king which were of stone and clay and very large and on one level (De Alcac¸ova 1506, in Documents 1962 vol. I: 395) thence to Embire, which is a fortress of the king of Menomotapa and is now made of stone without mortar (Veloso 1512, in Documents 1964 vol. III: 183).

In this same town of Benemotapa is the usual residence of the king, in a very large place…he is each day served with very large presents…and they bring them through the middle of the town bareheaded until they reach a very high house where the king is always lodged (Barbosa 1517–1518, in Theal 1898 vol. I: 96).

The natives of the country call all these edifices Symbaoe [dzimbahwe in Karanga] which according to their language signifies court, for every place where Benemotapa may be is so called; and they say being royal property all the king’s other dwellings have this name (De Barros 1551, in Theal 1901 vol. VI: 267)”

Huffman sums up by saying: “Rather, the entire palace was a sacred space that provided the leader with ritual seclusion from physical and supernatural danger...Among other things, people in ‘hot’ (i.e. contaminated) states could affect his power, while political rivalry was an ever-present threat. As a result of this need for supernatural protection, sacred leaders were separated from ordinary people and expected to be aloof…From an indigenous viewpoint, the space dedicated to sacred leaders was sacred by definition. The palace, in particular, was where sacred leaders held private audiences, ate, lived, and slept, and communicated with their ancestors.”[xi]

The significance of the spatial layout of dry-stone buildings

In order to give substance to the above Huffman is quoted again:

“In Shona and Venda spatial organization, the front is associated with secular activities while the back is reserved for private and sacred functions (this is also true for other Eastern Bantu speakers)

Although the entire palace was a ritual space, it nevertheless followed this convention. The front portion enclosed a section for the mambo (king) that included offices for a senior messenger and diviner, the king’s private sleeping quarters and sanctuary and an audience chamber. The large audience chamber was where supplicants could meet the king and his entourage in private. As Dos Santos described the scene (1609 in Theal 1901 vol. VII: 192, 195): [The new king] seats himself with the principal wives in a public hall in which the king hears all causes, in which he is hidden by a cloth or curtain so that none can see the king and his wives who sit behind it…When the [people] wish to speak to the king they throw themselves on the ground in the doorway and drag themselves to where he is and speak to him lying on their sides without looking at him, clapping their hands all the while they are speaking…When their business is concluded they withdraw in the same manner as they enter.”[xii]

Construction materials used in dry-stone walling

Granite Stone

The most common building material used was granite which was quarried in slabs by heating the surface with fire for some hours and then cooling it rapidly with water that caused slabs to split away from its matrix when aided by iron gads to prise them up. Within limits the longer the fire is kept burning, the thicker the slab which will eventually split away.

The builders were expert at this craft although it must have required huge quantities of timber to produce the quantities of stone particularly at Great Zimbabwe. Whitty first drew attention to the fact that the granite in Zimbabwe splits at right angle to the ‘plane of exfoliation’ thus producing the neatly shaped blocks we see today.[xiii]

Other stone

Banded ironstones, dolerite and greenstone schists were used as alternatives to granite particularly in forming various patterns in the stonework (chevron, herringbone, check, cord and line) which all held various symbolic meanings to the viewers.

Soapstone was also used in the carved monoliths and bird figures.

Dhaka

This is basically mud from termite mounds ground fine and mixed with water that sets hard upon drying.

Hut floors were mixed termite soil with fine decomposed granite dust and rubbed with a smooth heavy stone to consolidate the material. Often cow dung is mixed in to give a very hard surface which stands up well to day-to-day traffic.

Courtyard floors were a mix of termite soil and fire ashes upon which small fires were lit which heated the ashes within the dhaka mix and subsequently gently ‘cooked’ and baked extremely hard. This dhaka was used also in hut platforms, low walls in the open, kerbs and seats.

Wall dhaka was made by mixing termite mound with clay soil and short grasses or cow dung and was used for solid walls or around posts: provided the interior was protected from rain it remained weatherproof. To prevent a driving rain from eroding the base of a hut a kerb of courtyard dhaka would be plastered over the lower 30 cm of the huts and sometimes into a circular trench. Hut walls might be as much as 40 cm thick.

Evidence of reliefs made into the dhaka were found during excavations at Tsindi monument. As well as being decorated in relief, huts were most probably also painted in reds and yellows, purple and chocolate and white in both geometrical and more naturalistic designs although Summers says there is no archaeological evidence for the use of colours.[xiv]

Wood was clearly widely used although the presence of termites have ensured that very little survived to the present-day. Caton-Thompson and Robinson found wood pieces at Great Zimbabwe. In two logs found by Robinson radiocarbon testing dated them with mean ages of AD 700 +/- 95 years and AD 590 +/- 120 years.

Siting of the dry-stone buildings

Summers suggests that agriculture clearly had a strong influence in their sites. There is some strong differences of opinion of whether type 1 and type 8 buildings were built for agricultural or mining purposes which has already been discussed. Clearly some archaeologists believe the stone-lined pit structures were domestic stock pits, although Summers acknowledges the narrow tunnel entrances are too small for cattle and suggests sheep and goats. He also contends that the soils on the terraces would have become quickly exhausted that would have entailed the continuous building of new terraces. Both these explanations are rejected by Ann Kritzinger who believes their real purpose lies in gold-mining.

Building Types 1a, 2, 5, 6 and type 8a and 8b Summers believes are usually found on small rises in open country as if to watch over cultivated lands and that the low walls in type 8b would have been used to contain cattle so that they would not graze on growing crops. Type 9 enclosures within kopjes were primarily sited for defence but they also housed farming and cattle-owning populations.

Type 7 buildings (feiras) were constructed by the Portuguese with trading purposes in mind and always adjacent to gold fields that were being exploited by local pre-European miners as seen in the map below.

Type 3, 3a and 4 buildings show archaeological evidence of cattle rearing and crop growing but exhibit signs that that other considerations rather than just farming led to their siting. These are what Summers calls his “grand ruins” and the important ones in his opinion are numbered on the map above and include:

Zimbabwe and associated group (29)

Matendere group (24, 25)

Chichidza and Chibvumani (26)

Webster in Chipinga district (28)

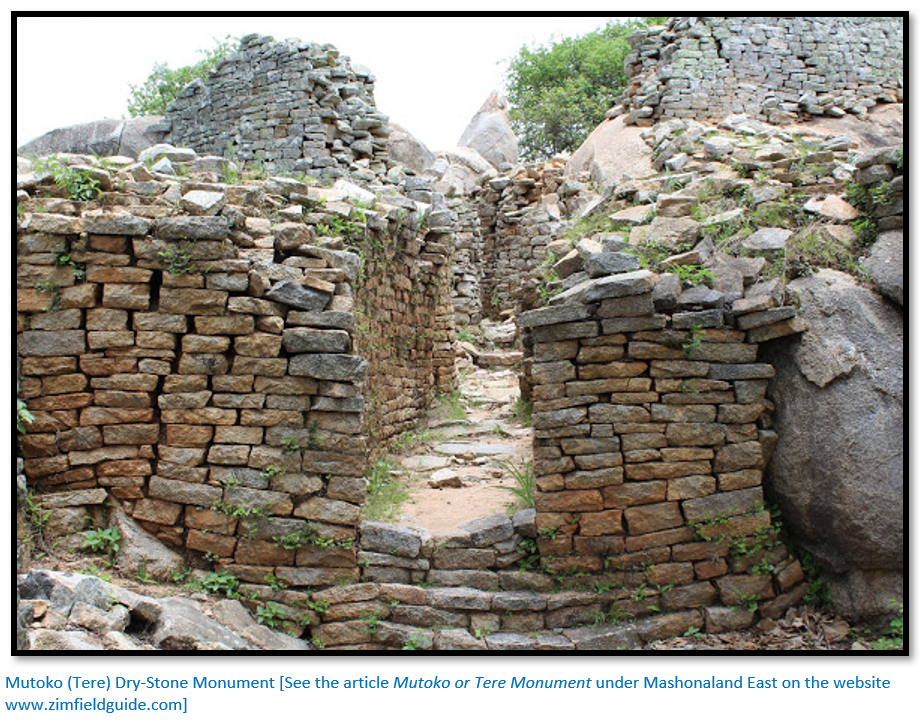

Lekkerwater (Tsindi) Harleigh, Mutoko (Tere) (9, 10, 3)

Bumbusi group (57, 58)

Tom Huffman believed that the leaders inherited the mantle of rainmaker and from this time sited their palaces on top of old rainmaking hills, the most famous being Great Zimbabwe. An important feature of this Zimbabwe culture was that dry-stone buildings became reserved for only the sacred leaders and their closest entourage.

Association of dry-stone buildings with ancient mining seems unlikely

Summers states the above map “shows that ‘grand ruins’ are frequently on granite outcrops close to the old mines, which were of course on gold-bearing rocks and not on the un-mineralised granite.”[xv] However even a brief view of his map above with its marked gold fields and the distribution of his “grand ruins” does not show a close relationship between them.

Great Zimbabwe’s prosperity most probably came from its position on the route between the gold producing regions and the seaports on the Mozambique coast, particularly Sofala and Quilimane; the rulers of Great Zimbabwe most likely regulated the gold trade over time until it became the heart of an extensive commercial and trading network. The main items being exported included gold, ivory, copper and tin and possibly cattle. Excavations in Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings and particularly the ‘grand ruins’ including Great Zimbabwe have revealed large quantities of glass beads, glassware from Syria, a minted coin from Kilwa, Chinese celadon dishes (mostly Ming dynasty 1368 to 1644) Persian faience bowls, bronze bowls and iron utensils, including hawk bells and iron gongs as well as coral and cowrie shells.

Estimates of the population at Great Zimbabwe range from 10,000 to 20,000. With an economy based on cattle husbandry, crop cultivation and the gold trade with the coast of the Indian Ocean, Great Zimbabwe was the heart of a thriving trading empire from the 11th to the 15th centuries which extended as far as Mapungubwe in South Africa’s Limpopo province to Manekweni in southwestern Mozambique.

Most excavations of the dry-stone building sites have revealed locally made pottery, objects of iron, copper and bronze including hoes and spear points and jewellery. Also locally made items found were soapstone carvings including the Zimbabwe birds and shallow bowls carved with a variety of designs and pipes for smoking dagga and a variety of domestic stone tools. Gold objects were found in great profusion but scavenged by the Ancient Ruins Company and so lost to archaeologists.

Association of dry-stone buildings with Chieftainship

Huffman explains that the layout of Plans 6 and 7 above and all the other dry-stone buildings in Zimbabwe indicate the spatial layouts of Matendere and Danangombe are directly linked with the cultural and ritual aspects of society and chieftainship. Firstly he maintains that: “similarities in layout between many settlements show that there must have been some underlying mental template, or structure, that generated the repetition.”[xvi]

Huffman explains that the Portuguese chroniclers grasped this concept and it is evident in their writings: “A sacred leader, ruling with the aid of a specially designated brother and sister, remained secluded in an elevated enclosure with a small number of officials (Barbosa 1517–1518, in Theal 1898 vol. I: 129; Bocarro 1631–1649, in Theal 1899 vol. III: 356); the back of this palace, in contrast, was reserved for national rituals and the youngest royal wives. A law court for disputes among

nobles was usually secluded inside the palace, while commoners resolved their disputes in a public arena (Dos Santos 1609, in Theal 1901 vol. VII: 208–209)

This public court was predominately a male area located to the side of the palace, opposite the compound for the leader’s wives. Most of his wives lived in a single compound under the authority of the first wife (De Barros 1551, in Theal 1901 vol. VI: 272) and this compound sometimes included an initiation centre. The leader’s mother lived at the edge of this complex, opposite a man in charge of female labour. Commoners formed a protective circle around these wives, as well as the leader, particularly on the west front side below the palace (Barbosa 1517–1518, in Theal 1898 vol. I: 128). Overall, the commoners, wives and palace were surrounded by guards and medicines (Dos Santos 1609, in Theal 1901, vol. VII: 202) while rivals for political power, such as district chiefs and regional governor lived in prestige enclosures outside this protective zone.”[xvii]

In summary:

- The palace,[xviii] in particular, was where sacred leaders held private audiences, ate, lived, and slept and communicated with their ancestors[xix]

- In Zimbabwe these dry-stone buildings are situated on a hill because of a metaphorical association between leadership and mountains. ‘To climb the mountain’, for example, means to approach a chief in the Shona and Venda languages (Hamutyinei and Plangger 1987: proverb 1486)[xx]

- The chapter on the significance of the spatial layout of dry-stone buildings demonstrates that the layout of these buildings followed a conventional pattern as shown in Plans 6, 7 and 8

- Distinctive radial walls often divided the audience chamber as at Danangombe, Khame, Naletale and at Great Zimbabwe to facilitate the separation of the leader from the others.[xxi]

- The rear of the dry-stone buildings was where the mambo (king) prayed for the good of the nation and usually included boulders and natural rock shelters. Rock shelters were direct entrances to the spirit world and enhanced the spiritual significance of this area. It may also have stored the king’s sacred drums, sacred objects and large grain bins to store sorghum for the production of ritual beer.[xxii]

- Dry-stone buildings are sited where traditionally rain-making ceremonies would have taken place in earlier times those perpetuating the tradition. Huffman writes: “Among other things, what had been rain-control hills in the wild bush became the locus for stone-walled palaces inside the capitals.”[xxiii]

Roger Summers

From Wikipedia: Roger Summers (1907-2003) was a Zimbabwean archaaeologist, who worked for the National Museums and Monuments Commission from 1947 to 1970 and was described as "a major influence in the formative years of Zimbabwean, then Rhodesian, archaeology". He came into conflict with the Rhodesian government due to his refusal to deny African origins of Gret Zimbabwe. He worked extensively on Great Zimbabwe, Nyanga and more generally on the Iron Age and ancient mining in Zimbabwe. He took part in many excavations including at Nyanga, Great Zimbabwe and Danangombe (formerly Dhlo-Dhlo) and wrote many scientific papers.

His books include: Inyanga (1958) Zimbabwe, a Rhodesian Mystery (1963) Ancient Mining in Rhodesia (1969) Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilizations of Southern Africa (1971) and edited Rock Art of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (1959)

Thomas Huffman

Huffman is an American archaeologist who obtained his MA and PhD at the University of Illinois. He was an Inspector of Monuments in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe and made many excavations in Zimbabwe and Zambia and specialises in the Iron-Age and pre-Colonial farming societies in Southern Africa. He is now Professor Emeritus at the Department of Archaeology at the University of the Witwatersrand. He has written many publications on farming and mining in the Iron-Age; some of which are listed on https://www.wits.ac.za/gaes/staff/academic-staff/tom-huffman

References

R.N. Hall and W.G. Neal. The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia. Methuen, London 1904

T. Huffman. Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture. Ethnoarchaeology, Vol 6 No 1, April 2014

A. Kritzinger. Gold Mining Landscapes of Nyanga: Discovering Zimbabwe's Hidden Heritage. Time Horizons, Zimbabwe 2017

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin, Cape Town 1971

National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (www.nmmz.co.zw)

Wikipedia

Notes

[i] Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture, P5

[ii] Wikipedia on Great Zimbabwe

[iii] Antonio Fernandes is also sometimes referred to as a degradado, a convict transported to the colonies, but appears to have been a carpenter and interpreter by trade and may have been involved in the construction of Fort São Caetano at Sofala.

[iv] At the height of its power in the 15th century the Kilwa Sultanate owned or claimed overlordship over the mainland cities of Malindi, Inhambane and Sofala and the island-states of Mombasa, Pemba, Zanzibar, Mafia and Mozambique Island - essentially what is now often referred to as the "Swahili Coast."

[v] Professor D.P. Abraham trained at Oxford as an historian and anthropologist and was a research fellow at University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland 1950 – 1955 and then at the University of North Carolina.

[vi] A. Whitty. A classification of Prehistoric Buildings in Mashonaland, Southern Rhodesia. The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol. 14, No. 54 (June 1959), pp. 57-71

[vii] Ancient Ruins, P48

[viii] Theal’s Records, Vol 6, P267-8

[ix] Gold Mining Landscapes of Nyanga: Discovering Zimbabwe's Hidden Heritage

[x] Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture, P11

[xi] Ibid

[xii] Ibid, P15

[xiii] Ancient Ruins, P148

[xiv] Ibid, P151

[xv] Ibid, P160

[xvi] Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture, P8

[xvii] Ibid, P11

[xviii] read ‘dry-stone building’ or ‘ruin’ or ‘monument’

[xix] Ritual Space in the Zimbabwe Culture, P11

[xx] Ibid, P12

[xxi] Ibid, P15

[xxii] Ibid, P22

[xxiii] Ibid, P4