World Wildlife Crime Report – Pangolins

Introduction

This article almost entirely relies on the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report called the World Wildlife Crime Report 2020: Trafficking in Protected Species hereafter called “the report.” I have extracted most of the information relating to Pangolins from that report which is available as a pdf from the website.

Since the publication of UNODC’s first World Wildlife Crime Report in 2016, regulation has increased for several wildlife markets, including that for pangolin products. International trade in all pangolin species is now banned. However, despite this, growing volumes of pangolin scales are being seized each year. The present edition of the World Wildlife Crime Report shows that between 2014 and 2018, seizures of pangolin scales increased tenfold.

The report draws its information from the seizure data in UNODC’s World WISE

Database which now contains just under 180,000 seizures from 149 countries and territories. This is supplemented by the new CITES illegal trade reporting requirement. CITES Parties are required to submit data on all seizures of wildlife made in the previous year and data for seizures that took place in 2016, 2017 and some countries for 2018 is included in the database.

See also the article Saving the Pangolin from the Wildlife trade where they are being increasingly trafficked under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com and read the work of the Tikki Hywood Foundation in Zimbabwe on saving pangolins (https://www.tikkihywoodfoundation.org/)

Some general observations from the report

From one country to another: geographic displacement

Criminals tend to exploit legislative and enforcement gaps in countries that are less capable of addressing them, (i.e. with regulation or the means to enforce the regulations) with the result that wildlife crime is displaced to these countries. This is the case, for example, with pangolin scale traders who store their stock in the Democratic Republic of the Congo as opposed to other source countries due to a perception of lesser capacity for interdiction.

From one species to another: wildlife product replacement

Similarly, African pangolin species were targeted after regulations tightened and populations were overexploited in Asia. Leopard, jaguar and lion bones have also emerged as substitutes in the tiger bone trade. At times, these substitutions are explicit, but often the buyers are not aware that a new species has been introduced.

How the value of wildlife seizures of pangolin scales has trebled in value

The 2009-13 period figures showed that, on the basis of the value of seized shipments, pangolins accounted for 5.5% of the total value: marginally ahead of rhino horn (5.5%) and the value of assorted reptiles (4.3%) but a long way behind elephants (33.1%) and rosewood timber (40.7%)

But for the period 2014 – 2018 the above chart shows the value of seizures of pangolin scales has increased to 13.9%; with corresponding increases in rhino horn (11.8%) but decreased seizures of both elephant ivory (30.6%) and rosewood timber (31.7%

The number of pangolin scale seizures has increased tenfold

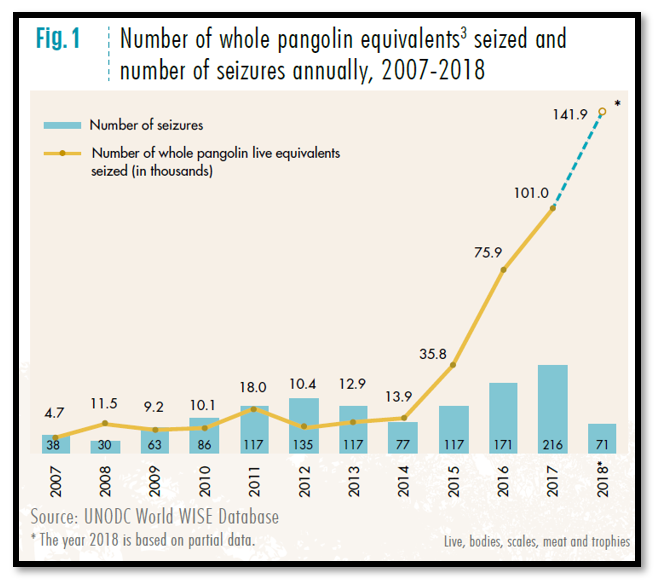

Between 2014 and 2018, Fig. 1 shows that seizures of pangolin scales increased tenfold from the equivalent of 13,900 pangolins to 141,900 pangolins. The reasons for this increase are unclear. All species of pangolins were elevated to CITES Appendix I in 2016, but there was very little legal trade before this time.

The main flow has always been illegal, but greater awareness may have produced a higher interception rate as a growing number of customs inspectors learn to recognise pangolin scales. The sharp and consistent increase in seizures of scales year after year, as well as the growth in the size of the largest seizures strongly suggest an increase in the illicit flow. Attempts to farm pangolins for commercial purposes have failed, and the loss of millions of wild pangolins to illicit markets cannot be sustained. Individual seizures made in recent years have been comprised of the scales of tens of thousands of pangolins, indicative of highly organized criminal operations.

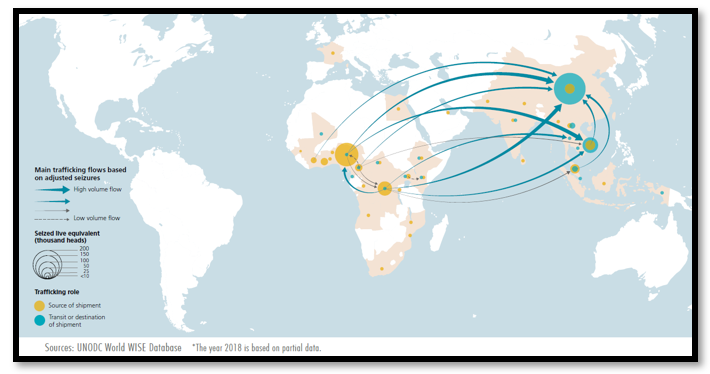

There has also been a shift in the nature of pangolin seizures over time, away from live and meat seizures (mainly of Asian species) and towards African pangolin scale seizures. Significant meat seizures continue to be made in Asia, but most seizures in recent years

were of scales exported from Africa (especially Nigeria and the Democratic Republic of the Congo) to Asia (especially Vietnam) Looking at a broader range of time, China has been the primary destination of pangolin shipments, so it appears that, as with ivory, Vietnam has become a conduit for this larger market.

Routes used for trafficking pangolins from Africa to Asia

Pangolin facts

Pangolins are reclusive nocturnal creatures and the only mammal wholly covered in scales. They remain elusive, with researchers having limited knowledge of their ecology, yet they are now arguably the most heavily trafficked wild mammal in the world. There are eight species of pangolin: four found in Asia and four found in Africa. They have traditionally been consumed in both regions, but only recently have the two markets met.

There has been a sustained increase in seizures of the species since 2014 (Fig. 1) Due largely to their exploitation in illegal trade, all species of pangolin were transferred from CITES Appendix II to Appendix I at the CITES Conference of the Parties in 2016.

Today, demand for pangolins in Asia is being supplied by pangolins from Africa. In both regions, pangolins are killed for their meat and their scales, which have been used medicinally. Pangolin products have been used in traditional Chinese medicine for

thousands of years to treat a wide range of ailments. The scales are said to promote blood circulation and increase lactation in pregnant women, while the meat is used as a tonic.

They are also used as medicine in Africa. In Nigeria, for example, pangolin parts are used to treat a wide range of physical and psychological conditions.

The pangolin market has changed dramatically from meat to scales

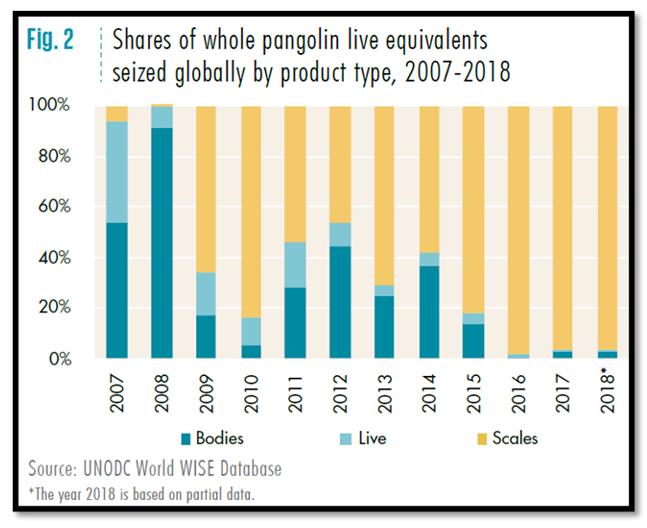

Fig. 2 shows that in 2007 the seizures of pangolin showed that 95% were destined for meat (dead or alive) and that scales only accounted for 5% of the illegal trade. By 2018 98% of the seizures showed that the shipments were of pangolin scales and only 2% for meat. Clearly for traffickers in Africa it is much simpler to ship pangolin scales and this is the source for most seizures.

All eight species of pangolins are believed to be in decline, but since exact population counts are unavailable, it is difficult to determine the conservation impact of the illegal trade. The sheer volume of seizures, though, suggests unsustainable harvesting, a hypothesis corroborated by hunters interviewed by UNODC in Uganda and Cameroon in 2018, who reported that pangolins are becoming harder to find.

As already stated since 2014, there has been a ten-fold increase in the number of whole pangolin equivalents seized globally (Fig. 1) The inclusion of all pangolin species on Appendix I in 2016 likely had some role in this trend, especially as it increased awareness, but there are several reasons why the listing is unlikely to be solely responsible for the increase:

--- The increase started in 2015, two years before the listing took effect.

--- The size of individual seizures has increased, alongside the increase in overall seizure quantity.

--- Before the Appendix I listing, the amount of pangolins seized was much larger than the legal trade, implying that the industries where pangolins are used have long drawn on illegal sources.

Legal versus illegal pangolin trade

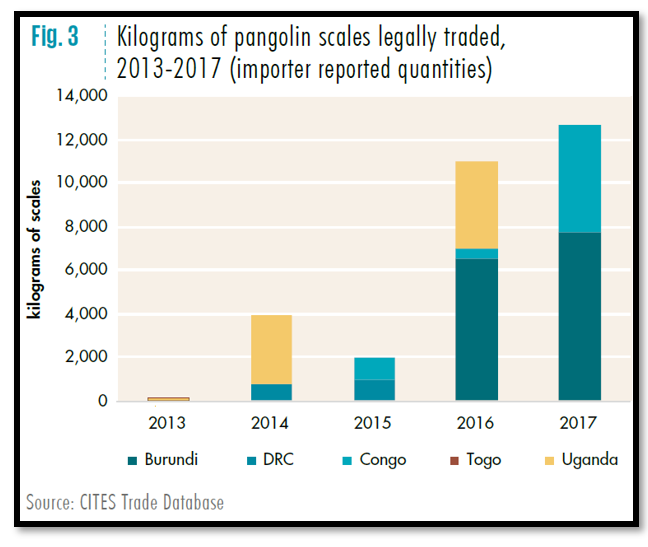

Between 2013 – 2017 the weight of pangolin scales legally declared increased from almost none to 12,500 kgs. Initially Uganda was a significant legal supplier, but by 2017 the vast bulk of legally-supplied pangolin scales came from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Congo. (Fig. 3)

Most illegal pangolin shipments are from Africa

Sizable shipments of whole (often live) pangolins have been seized in Asia 2015 (Malaysia) but most of the largest recent seizures have involved pangolin scales sourced from Africa (Nigeria, DRC and Cameroon) Prior to 2009, the international trade involved mostly pangolin meat and scales, sourced in Asia (Fig. 2) The reasons for the shift to African sources is unclear, but may be due to declining Asian populations. There have been very few seizures of pangolin meat from Africa. The reasons for this are also unclear, but almost all the World WISE pangolin seizures coming from Africa have been comprised of scales. The seizures had the most common source as Nigeria (58%) DRC (25%) and Cameroon (5%) (Fig. 3)

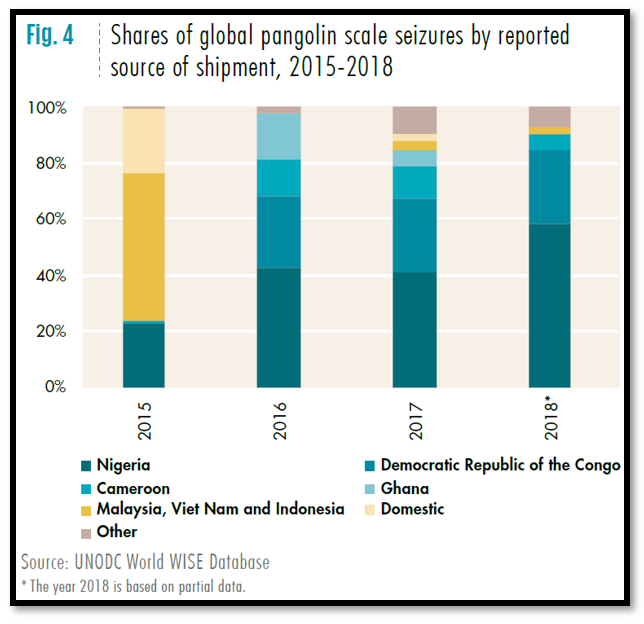

Most of the large African scale shipments originated in West and Central Africa, where three out of the four African pangolin species are found. (Fig. 4) Four pangolin species are also found in South-East, South and East Asia. Most of the trade for all species is destined for East and South-East Asian countries. Before 2016, the largest seizures intercepted amounted to less than 10,000 live pangolin equivalents. In 2019, the three major seizures made by Singapore were equivalent to more than twice that number.

In 2000, CITES Parties adopted a zero-export quota for wild-caught Asian pangolins traded for primarily commercial purposes. The legal trade in African pangolin species was rare until about 2014. Between 2013 to 2017 (when the up-listing of all pangolin species to Appendix I came into force), the amount of pangolin scales legally imported went from almost zero to nearly 13 tons, with four countries being responsible for the bulk of the shipments: Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Congo (Brazzaville) and Uganda (Fig. 3). China was the importer of 99% of this volume.

Demand for pangolin meat persists, but it appears to be satisfied regionally. Intercontinental meat seizures, though, remain rare, and the short geographic distance of trafficking may be one reason why meat seizures are not detected at the same level as scale seizures in recent years. Based on World WISE data, meat seizures represented 15% of pangolin seizures in 2015, compared to only 1-2% of pangolin seizures from 2016 to 2018. There were 4,355 live pangolin equivalents’ worth of meat seized in 2018, out of 187,256 live pangolin equivalents seized overall that year. There is some debate as to how much of the large increase in scale trafficking could be coming from stockpiles that existed prior to pangolins’ CITES Appendix I listing, and therefore, how much poaching is taking place. Nineteen countries have declared pangolin scale stockpiles to CITES.

China reports regularly releasing these stockpiled scales for domestic use by designated hospitals and manufacturers of patented Chinese medicines. The volume of declared stockpiles in source and destination countries is far smaller than the tens of thousands of whole pangolin equivalents seized over the past decade (Fig. 3) It is therefore unlikely that leakage from declared government stockpiles contributes significantly to the illegal trade: most sourcing is likely coming from the wild and most from African source countries, and not from stockpiles.

West Africa is the prime source of trafficked pangolins

The magnitude of the illegal trade - based on seizure records – suggests that this wild sourcing is unsustainable. Breeding of pangolins in captivity at commercial scale is currently not possible. Highly specialized diets combined with extreme sensitivity to capture-induced stress mean that pangolins fare poorly in captivity. Pangolins generally give birth to one cub at a time with gestation periods that range from about 65 to 370 days. Only a few births have been reported in captivity, with high infant mortality rates. At present, sourcing from captive-bred populations does not seem to be possible to meet demand and/or replace the wild population of pangolins harvested by hunters.

Given that the scales from one pangolin weigh anywhere between 0.36 to 3.60 kg,23 multi-ton seizures of scales represent far larger numbers of pangolins killed than meat shipments of a similar weight. Estimates of how many pangolins have been illegally traded in recent years are difficult to calculate given that:

--- seizures represent only a small fraction of the animals killed

--- size and weight of scales vary between species; and

--- incomplete seizure records that make it difficult to know what species was seized.

According to pangolin hunters and traders interviewed by UNODC in Cameroon and Uganda, giant pangolins are relatively rare. If each pangolin killed for illegal trade in Africa produced an average of 500 grams of scales, the 185 tons of scales seized between 2014 and 2018 would represent about 370,000 pangolin equivalents.

Nigeria / Cameroon / DRC are major pangolin suppliers

In 2000, zero export quotas were established for Asian pangolin species whose populations were seriously depleted from the skin and meat trade. These zero quotas may have contributed to the decline in the skin trade, but despite population depletion, sourcing from South-East Asia (primarily from Indonesia, Malaysia and Thailand) continued in large quantities until 2013, at which point it dropped off significantly.

Based on World WISE seizure data, it appears that, starting in 2013, the source of seized pangolins shifted to the African continent, primarily to West and Central Africa. Seizures were made first on shipments coming from Cameroon, then Nigeria, and then (in

2016) from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (Fig. 4) Other source countries mentioned by pangolin traders during fieldwork include the Central African Republic, Congo, Gabon and Uganda. Recent large seizures in Côte d’Ivoire involve Guinea and Liberia as additional source countries for trafficked pangolins.

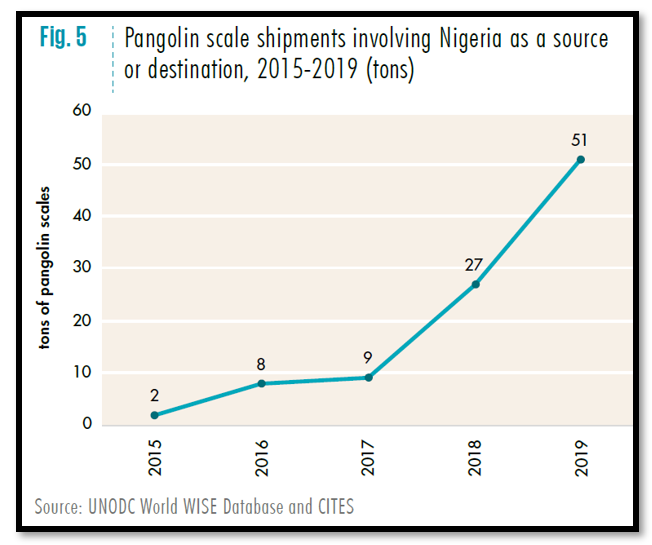

Nigeria, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo act as transit countries and logistical hubs for pangolin and wildlife trafficking more generally. Illegal pangolin trade in Nigeria seems to have grown significantly in recent years, and the country was the reported provenance of at least 51 tons of pangolin scales seized in 2019 (Fig. 5)

Actors involved in pangolin scale trafficking

Based on UNODC fieldwork in Cameroon and Uganda in 2018, it appears that the initial hunting of pangolins for the trade is done by local community members. Wealthier

local traders and intermediaries then consolidate their catch into bulk batches and transport them to urban centres where they are trafficked onward by Asian expatriates. In some locations, it is not unusual for a large number of members of a community to be involved in hunting pangolins, often in addition to their main job as farmers.

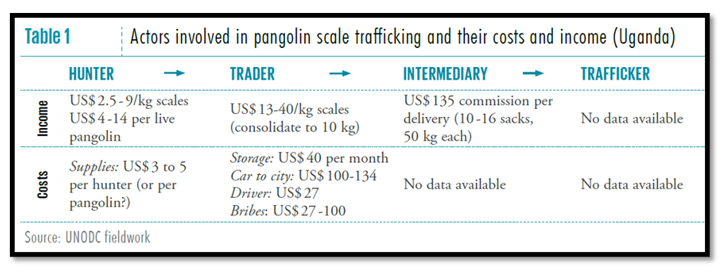

As a result, there are large numbers of suppliers dispersed throughout rural areas. These suppliers seem to be primarily part-timers. Entering the illicit trade chain is easy. Without the need for the heavy guns and specialized equipment required for big game hunting, anyone can participate. UNODC fieldwork in Cameroon found that prospective new entrants only need supplies costing US$3 to US$5, with hunters making anywhere from US$8 to US$13 for a small live pangolin and US$25 to US$30 for a large one. In Uganda, hunters report being able to catch anywhere from one to 20 pangolins per day. Hunters in Uganda track the animals and set traps, while hunters in Cameroon use wire traps or hunting dogs.

Processing pangolins

Pangolins, once dead, are immersed in hot water or fire and descaled with a knife. The scales are then dried in the sun in centralized ‘drying camps’ set up by hunters in the forest. Some hunters reported keeping the meat to eat. In Cameroon, scales were also recovered from open bushmeat markets in the region or from restaurants selling the meat. According to UNODC fieldwork, most people seem to understand that pangolins can be sold for profit, which encourages local hunters to catch them whenever possible. Most hunters and even traders interviewed knew very little about the animal itself and had radically different and often misguided ideas of what consumers used the animals for, including making bullet-proof vests out of their scales. Local traders and intermediaries consolidate scales until

at least 10 kg are ready for transit to urban centres. These operators – some of whom are women - tend to be local residents. They are in contact with international traffickers, who sometimes pay for their services by wire transfer.

The first buyers are often small business owners, local authorities or transportation workers that have enough cash to buy stock from local hunters and pay for transit to urban areas. In fieldwork in Cameroon and Uganda, it was reported that Congolese and Nigerian citizens act as traders and intermediaries. In the urban areas, the pangolin scales are sold to international traffickers, primarily Chinese, but also some Nigerians and Vietnamese. International traffickers tend to be individuals with enough wealth and political connections to ensure protection from the authorities. These include high-level government officials and wealthy business people but can also be foreign workers based in the country for development projects.

The number of actors involved in the trafficking from source to destination ranges from five to more than 15 people, with prices paid to each actor increasing the closer one gets to the consumer. For example, in Uganda, traders who consolidate scales are paid quadruple the price per kg than that paid to the hunters.

Traders order pangolin scales by the kg, with a preference for the large scales from giant pangolins, Manis gigantea, which hunters report are harder to find. Several hunters described traders seeking them out and requesting they switch to hunting pangolin rather than other species.

Table 1 above provides an overview of the actors involved in the trafficking of pangolin scales from source to the international trafficker in major urban centres. It includes associated costs along the way, where known, using data collected through field interviews in Uganda as an example.

Trafficking pangolins from Africa to Asia

Trafficking is done by sea, air and land, and parcel post is also sometimes used. Shipments may not be well concealed, but they have been found under frozen meat and ice, hidden in logs using candle wax and stuffed inside steel barrels of other goods. Large illegal consignments of pangolin scales in shipping containers are either mis declared or concealed

under ‘cover loads’ such as plastic waste. International seizures have shown that traffickers are using the same techniques repeatedly, including regular air shipments of relatively small amounts of scales. For example, authorities in the Netherlands have repeatedly seized similarly packaged consignments of about 20 kg of scales from Nigeria in parcel post. Malaysia also seized a series of similarly packed shipments in air cargo from Ghana in 2017. Some are even smuggled in luggage and sent via parcel post declared as wood chips or other commodities. Traders reported that pangolin traffickers often use the same routes to export and import pangolin scales as they do ivory. A third of hunters and traders interviewed in Uganda reported that traffickers take advantage of the weak border controls and security challenges in northern Uganda, Democratic Republic of the Congo and South Sudan to offload the scales they collected, sometimes concealing themselves as impoverished locals to avoid detection at known checkpoints. Traders and traffickers also store stockpiles of scales in countries where the rule of law is weaker and wildlife crime enforcement limited before moving the scales for immediate sale to buyers in more high-risk locations.

The development of logging operations in previously wild areas, bringing with it an influx of people and infrastructure like roads, facilitates hunters’ access to wild pangolin populations, making areas near logging operations particularly vulnerable to pangolin poaching. In fact, two-thirds of the interviewees in Cameroon noted that traders often transport scales to larger cities on logging trucks, with the scales concealed as wood chips or foodstuffs. A third of the traders interviewed in Uganda mentioned using motorbikes for local transport, although several choose “fancier” vehicles that belong to official organizations when possible to limit the chances that they will be searched.

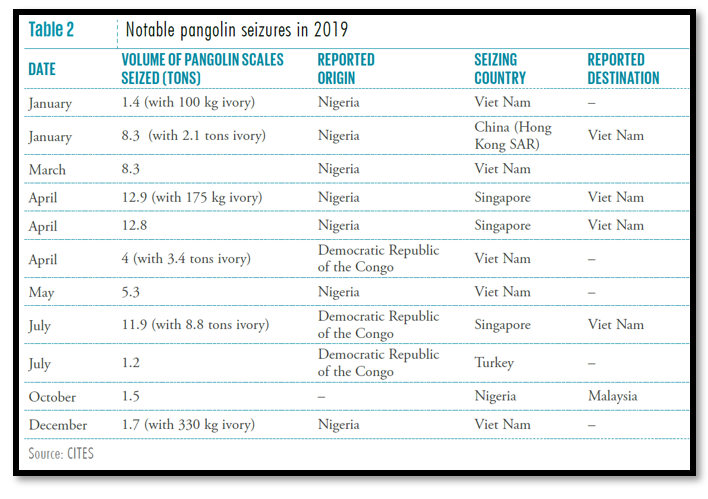

Very large individual seizures in 2019 show that Nigeria is the primary point of export of pangolin shipments, while Vietnam has emerged as the primary destination (Table 2). In October 2019, the Chinese government announced having seized 23 tons of pangolin scales in China in a series of operations. These shipments were coming from Nigeria via the Republic of Korea. Ivory traffickers appear to be involved in the pangolin scale trade, often transporting mixed shipments of ivory and pangolin specimens together.

The interviewed hunters also seem to be of the view that authorities consider crimes associated with pangolins as less serious than other forms of poaching, for example elephant poaching. Fear of enforcement action did not appear to play much of a role in their decision-making.

Currently, the market for elephant ivory appears to be in decline, while, according to interviews with hunters in Cameroon and Uganda, pangolin prices have been going up since 2017. UNODC fieldwork in Cameroon and Uganda suggests that some ivory traders may be entering the pangolin scale trade in response to lower risk. For example, hunters interviewed in Uganda reported that while they used coded language to discuss transactions involving ivory and rhino horn over the phone, they did not feel the need to take such measures when trading in pangolin products and openly discussed the number of kg of pangolin scales that they wanted to buy or sell. If those involved in the ivory trade are now selling pangolin scales, this would imply that the pangolin trade can now build on the supply chain of the well-established ivory market.

The demand for pangolins

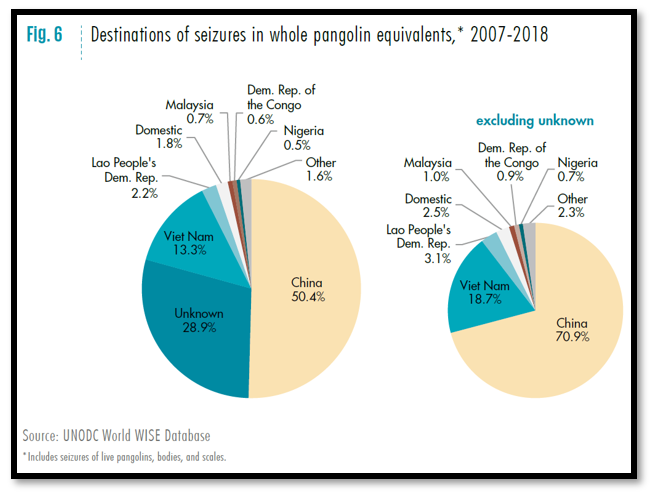

Based on seizures, most pangolin scales are destined for traditional medicine use in China, followed by other Southeast Asian countries. Some 71% of seizures of whole pangolin equivalents recorded in World WISE between 2007 and 2018, were destined for China, with 19% bound for Viet Nam (Fig. 6) As noted above, this routing seems to have changed dramatically in 2019, where all the major seizures were destined for Vietnam.

In China, the cities of Fangchengang, Guangzhou and Kunming are key nodes for pangolin trafficking according to a 2016 study of 206 Chinese seizures. In a survey of five major Chinese cities in 2012, Guangzhou residents reported the highest rates of wildlife consumption for food and as ingredients for traditional medicine.

Consumer surveys in 2018 of 1,800 people living in Chinese cities with active markets for wildlife products (Beijing, Guangzhou, Harbin, Kunming, Nanning and Shanghai) support the increased demand argument, especially for scales. Some 68% of that group reported that they intended to rebuy pangolin products in the future, suggesting that there is a stable base of buyers regardless of campaigns against the practice. The government announcement in August 2019 that pangolin products would no longer be covered by China’s state insurance funds could reduce purchases overall.

A 2018 survey of 1,500 wildlife product consumers in key Vietnamese cities (Can Tho, Da Nang, Haiphong, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City) found similar results and consumer profiles for pangolin scales and powder. About 60% of the sampled buyers who bought pangolin products in the last 12 months and 54% of all buyers of pangolin products surveyed indicated that they would purchase these again, suggesting a strong continuing consumer demand.

References

World Wildlife Crime Report Trafficking in protected species 2020. May 2020. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, Vienna