Witches and Witchcraft

By Ignatius M. Zvarevashe

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

The Shona word muroyi (pl. varoyi) means ‘witch’ and nearly always refers to a woman. A muroyi travels at night visiting those places and people she wants to harm. Before she departs from her home she bewitches her husband so that he falls into a deep sleep and cannot wake up until she returns.

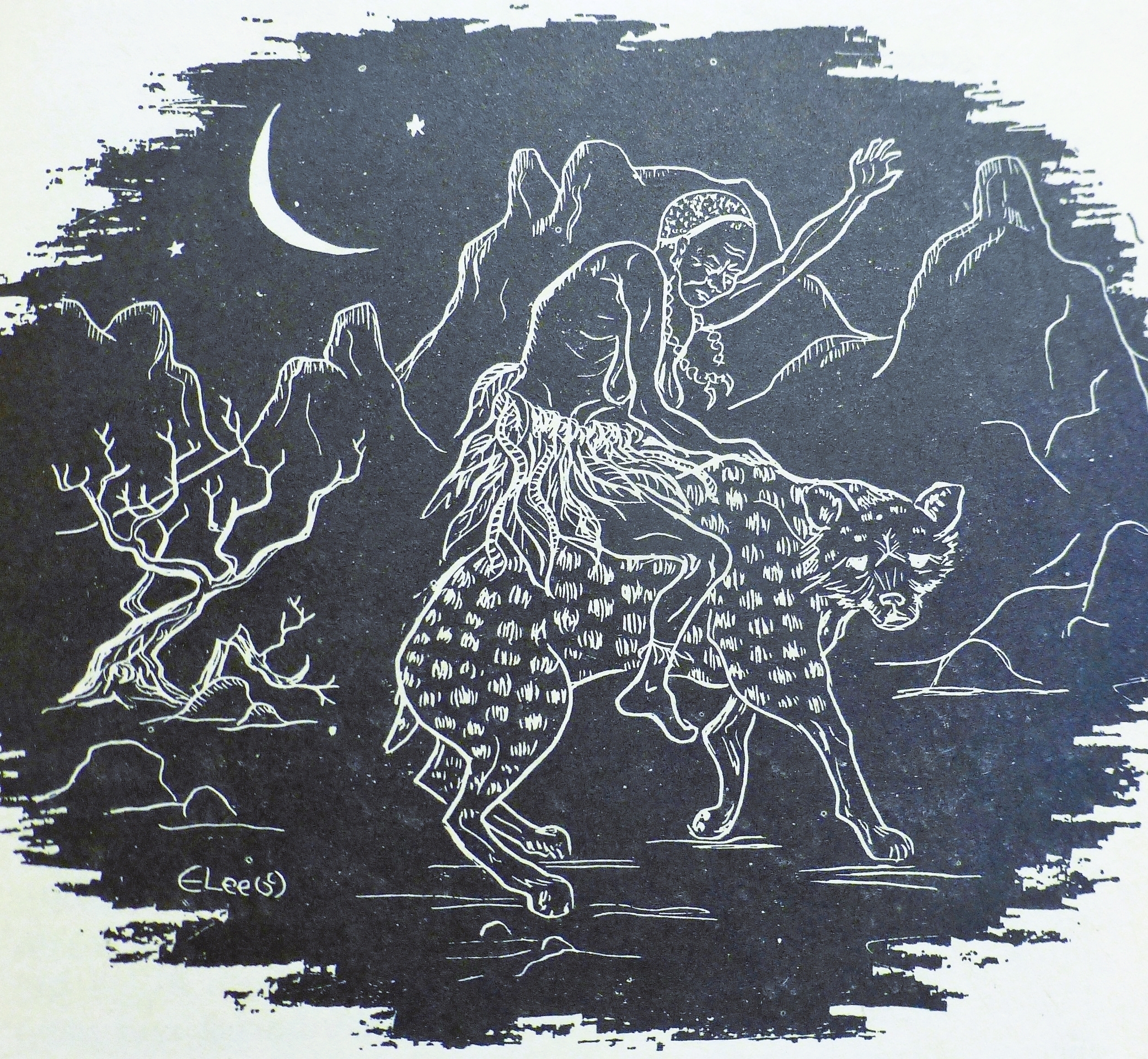

In order to bewitch a person, the muroyi must know the victim's family (dzinza) and his clan name (mutupo) otherwise her witchcraft is harmless. To travel, the muroyi usually rides on the back of a hyena. When she reaches her destination, she bewitches the house and the surroundings so that the victim falls into a coma. Then she recites a number of praises connected with his family and clan names. In so doing, she begs his ancestral spirits to allow her to do what she wants with this person. After reciting this litany of praises solemnly. She proceeds with her work.

She sends her ghosts (zvidhoma) into the victim’s house to kill him. In some cases she calls the victim’s name and the sleeping person wakes up hypnotised. In this state, he does as she commands and unlocks the door. Such a bewitched person rarely dies while the witch is present and operating on him because his matrilineal vadzimu (ancestral spirits) prevent this. When the witch has departed, the victim wakes up yelping, shivering, powerless and half mad.

When relatives discovered that a kinsman has been beaten by the ghosts (warohwa nezvidhoma zvomuroyi) they run to an n’anga who can either cure the sick person or advises them of someone who can. In many cases, after the witch has been named by a n’anga, the relatives go to that witch and implore her to cure the sick person. They don't kill her that she is the muroyi but they flatter her, saying: “a certain person thinks you are able to help. If you can cure him, we will give you some money or a goat.” Then the muroyi may reverse her spell and the sick person recovers.

A muroyi passes her witchcraft (uroyi) on to the next generation when she dies. There is a case that occurred near Masvingo River where a daughter refused to continue the witchcraft of her late mother and was punished by being rendered barren. The n’anga told her to carry out the job which her mother used to do, but she refused and remained barren.

There is a kind of witchcraft caused by a shavi (wandering spirit) called uroyi hweshavi. This is the spirit of a witch who has died without leaving children or relatives in whom her spirit can manifest himself. The spirit comes to a foreigner who may either welcome or refuse this bad shavi. If accepted, the shavi will cause its medium (svikiro) to become a muroyi.

Most kinds of witchcraft are operated only by women. However, males also possess a form of witchcraft called black medicine. It causes physical disorder. This medicine can be used at any time especially during the day. This type of black medicine is a formidable force among workers who are usually jealous of each other’s positions. Many Africans have been injured for life by this type of uroyi. Even the Shona who are Christians fear this kind of witchcraft.

There are many stories about varoyi. When a person has died and been buried, the witches made visit the grave in the night. Using a magic stick, one of them beats the grave once and it opens. Then the varoyi enter the grave and take parts of the dead body to mix with their medicine. If the dead person happens to be young, they take the whole body, dividing it fairly between themselves and eat it.

When varoyi want to make ghosts (zvidhoma) which are the children of the varoyi, they bewitch a young person. When the child has died and been buried, the varoyi visit the grave and by the usual method they entered the grave, call back the spirit of the dead child and make them eat their medicine. Thus they create a ghost (chidhoma) Varoyi can only make a chidhoma out of someone they have killed themselves. A sign that a person has been killed by a witch is an owl which comes during the burial and perches on a tree near the grave. The Shona believe an owl is an omen of ill fortune and a harbinger of illness or death.

Among the Shona-speaking people, witchcraft is a traditional practise which continues into the present. Even today it is common to find a witch in nearly every village.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974