Runde (formerly Lundi) River strip road

- The strip roads were unique to this country and although they had their disadvantages, they enabled the road engineers to cover a much greater distance of roads with asphalt/macadam than would have been possible on a limited budget.

- Many of the older residents remember the tarred strip roads from their younger days of travelling to South Africa and Beira on holiday and the perils of having to edge off the tar strip onto the shoulder of the road, often with a drop of more than 10 centimetres.

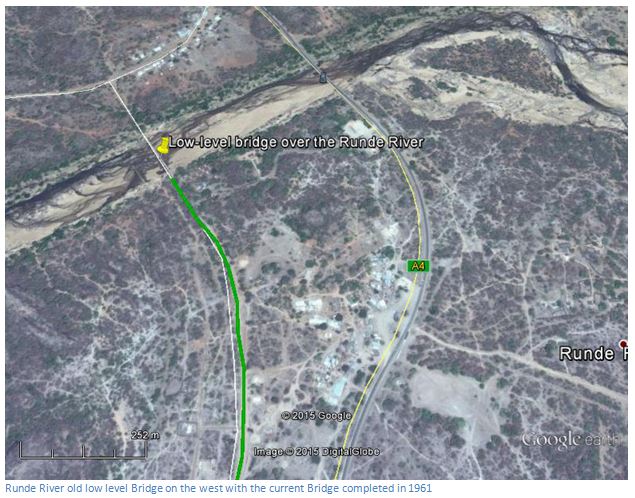

From Masvingo (formerly Fort Victoria) to Beitbridge the sequence of major rivers is the Tokwe, Runde, Nuanetsi and the Bubi. The Runde River (formerly the Lundi) section of strip road is south of the low-level bridge as seen on the Google Earth imaging below.

GPS reference: 20°53'37.20"S 30°46'30.91"E

In 1900 there were no properly constructed roads in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and when travelling on these dirt roads the ox-wagons had to plough through deep sand, or be man-handled over stretches of black clay and dense clouds of dust choked everything and reduced Europeans and Africans alike to a uniform grey. So rudimentary and primitive were these roads that sometimes it was difficult to tell them apart from the animal tracks around them. Sir Crawford Douglas-Jones noted: “One of the chief difficulties was that of keeping to the road they wished to follow. On leaving a town, the track would be distinct and easy to follow but a few miles out, unless one was familiar with the road, it became difficult to decide which was the correct way, either the well-defined spoor, or the indistinct one often hidden in the tall grass.” All traffic came to a standstill during the rainy season, not only because of the muddy conditions, but also at river crossings where the drifts would be impassable. Interminable delays, sometimes of up to six weeks, were not uncommon due to flooded rivers which forced travellers to bide their time until the rivers were passable once more. Not surprisingly, the journey from Salisbury (now Harare) to Tuli took three to four weeks.

It was not only the main roads linking the country's towns which were in poor condition; even in the towns, the roads were in such an appalling state that many settlers resorted to the use of bicycles. An amusing account is given of Rudyard Kipling's experience when riding a bicycle on Bulawayo's streets one day when he hired a bicycle from Duly’s for 7s 6d and set off for the Umgusa Hotel, where he arrived with a flourish. In a spirited moment, he took a running leap over the low railing of the verandah. His style was admirable, but sad to relate, he lacked altitude and caught the top rail in his flight, landing heavily on a flower bed.

A Roads Department had been created in 1895 by the BSA Company, but even by 1914 it had a total transport fleet of only 39 scotch carts and 89 mules and because of inadequate resources had managed to establish only a few earth roads and built a total of only seven footbridges. Throughout the BSA Company years, farmers continued to demand better roads, particularly as they felt that the railways were taking advantage of their monopoly position as the sole carriers of goods within the country to charge unacceptably high transportation rates and complaints became more vociferous following the increase in railway freight rates in 1916 when grain rates doubled.

Even by 1919 the Roads Department was still inadequately equipped for its task. Its annual report states it had carried out repairs on over 2,500 kilometres of roads, but noted that if it 'had been more fully equipped with carts, mules and oxen, more permanent work would have been undertaken'. Throughout the BSA Company period, labour for road construction and maintenance was supplied primarily by African convict gangs and conscripted African labourers who worked under the supervision of a handful of White overseers. The same 1919 report stated that the department was employing five permanent convict parties for road construction work, four of which 'were fifty-strong, with necessary guards . . . and one party twenty-five in number.' From the late 1920’s convict gangs were phased out and staff hired in their place.

By the end of 1926, the Roads Department had increased their equipment to a total of 326 scotch carts, 2,262 oxen, 126 mules, 56 rollers, six motor lorries and two concrete mixers and had also constructed seven high-level and 25 low-level bridges throughout the country. Until 1929 Chandler built only gravel roads as the volume of the country's road traffic was still too low to justify spending large sums for the construction of the more expensive permanent roads. This policy changed however as more and faster motor vehicles in the late 1920’s began to cause corrugations on the gravel roads, especially in the dry season.

The country's first motor car did not arrive until 1902 when Charles Duly became the proud owner of a chain-driven, single cylinder, six-and-a-half-horsepower French Gladiator. Soon afterwards, Duly's friend, Francois Issels, imported the second car to grace the country's roads: a Ford. Thereafter, more cars were imported into the country as the new mode of travel became increasingly popular. By 1922 the number of motor car owners had increased sufficiently to justify the formation of Rhodesia's own Automobile Association (AA) whose membership was reported at 1,000 and in the late 1920’s the motor car became more popular and large numbers of cars were brought into the country.

R. Hodder Williams noted that, while in the early 1920s most farmers in Marandellas (now Marondera) District used ox-wagons and car owners 'were the exception', by the end of the decade, the Ford Model-T was becoming more familiar. To service farming areas, the railways introduced the Rhodesian Motor Services (RMS) and the first service ran from Sinoia to Miami and was served by a Thornycroft A3 Petrol-driven six-wheeled vehicle, with a payload of two half tons; the first lorry with three axles to be used in the country, but because of the poor condition of the roads, the 72-mile trip from Sinoia took eight hours in the dry season and a staggering 24 hours during rainy season.

By 1930 there were many more cars and lorries in the roads and after a very light rainy season many drivers complained about the corrugations and dust experienced on the main roads. S.F. Chandler, the Chief Road Engineer, carried out an experiment on the Gweru – Shurugwi (formerly Selukwe) road by laying two parallel concrete strips an axle base apart for a car, or truck and estimated to have a 15 year life; these were followed with concrete strips from Bulawayo to the Matopos and from Harare to Beatrice in 1932. Although effective, they were expensive and so the next experiment entailed using asphalt/macadam parallel strips.

In 1931 an unemployment relief scheme to help men who had lost their jobs due to the Depression was rolled out to extend the road system and experiments were carried out with asphalt/bitumen and in 1932 the first of the strip roads were laid. By the end of 1933, 54 miles of asphalt/bitumen strips had been laid at an average cost of £320 a kilometre, a saving of more than £200 a kilometre on concrete strips. By 1934 about 275 kilometres were complete and by 1945 about 3,600 kilometres of strip roads had been laid, but experiments to convert existing strips into narrow tar roads proved uneconomic. They were built to last 10 years, but WWII meant they had to last longer than was intended and some strip roads stayed in fair condition for more than 20 years. Only after 1945 were surfaced roads, other than strip roads, constructed.

The 'Strip Road' was a unique concept and was essential for the development of a very young country in constructing a road network. This was of course not immediately possible because of financial constraints. The 'Strip Road' concept was arrived at essentially as an interim measure to allow for the development of a much needed functional road network while financial resources were being built up to construct a fully tarred road infrastructure. Many visitors to the country commented in an uncomplimentary fashion about the strip roads, but they served a useful purpose enabling many more kilometres of road to be built than would otherwise have been possible.

When two cars on a strip road approach each other from opposite directions, each is expected to move away from the centre of the road and use only one strip until the other car has passed. The drop off the macadam was often 10 centimetres or more, meaning each vehicle had to slow up as they approached each other, before dropping off the outside wheel until the cars had passed and then driving back up onto the strips.

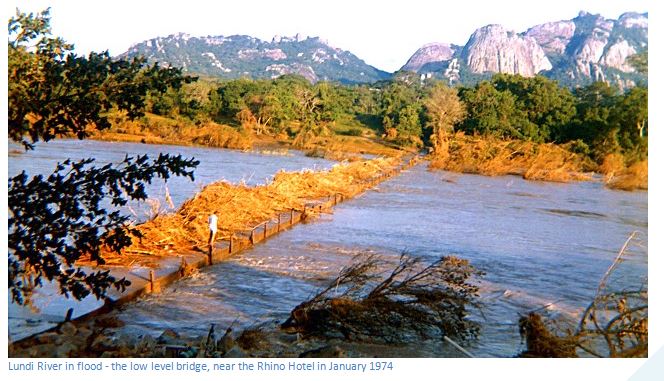

From 1924 the first low-level bridges were constructed on the main roads, usually with money given by the Beit Trustees. They made travelling less hazardous, but there were occasions when flood-waters over-whelmed them and travellers were often caught between two rivers, where they waited for hours and even days. The low level bridges were also all built as single lane structures; so right of way was determined by which car arrived at the bridge first and a simultaneous arrival at opposite end of the bridge was usually settled by courtesy of the drivers, a flash of the headlights giving the other car the 'go ahead'. These times have gone and the low-level bridges have been replaced by concrete structures, many of which take traffic far above the level of any flood hazards.

Acknowledgements

ORAFs website

Encyclopaedia Rhodesia

From Dirt Tracks to Modern Highways: Towards a History of Roads and Road Transportation in Colonial Zimbabwe, by Alois S. Mlambo

Tabex Encyclopedia Zimbabwe