Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident’

Gold fever prior to 1890

Galbraith reminds us that the young men who made up the Pioneer Column in 1890 were all united in their excitement at the prospect of the gold finds that awaited them and had been lured by the promise of 15 gold claims and a 3,000 hectare farm. Most would later sell their farms for £100 to the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow before dispersing to try their luck at prospecting.

More than twenty years previously Karl Mauch[i] had been invited by Henry Hartley in late 1867 to go on a hunting and exploring trip into Matabeleland and Mashonaland. Travelling between the Shashi and Ramaquabane rivers, a region after called the Tati district, they came across extensive pre-European gold workings.

The Transvaal Argus printed a letter from Mauch on 4 December 1867 in which he wrote that countless thousands would find wealth there in the future. “The vast extent and beauty of these goldfields are such that, at a particular point, I stood as if transfixed, riveted to the place, struck with amazement and wonder at the sight, and for a few minutes was unable to use the hammer.”

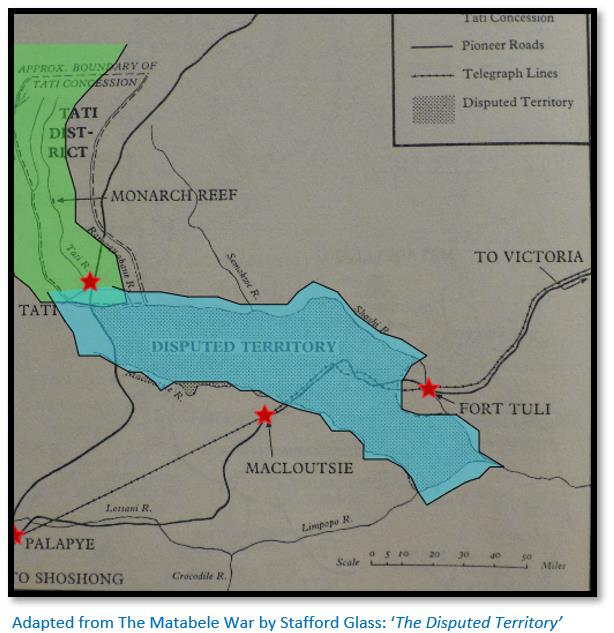

The Tati district, known colloquially as the ‘disputed territory’ at the time lay between the Shashi river on the east with the amaNdebele under Mzilikazi until his death in 1868 and then his successor Lobengula and the Macloutsie river on the west under Chief Khama III.

The news of Mauch’s gold discovery was printed around the world and led to a rush of small prospecting parties – mostly from Potchefstroom and included at least one listed London gold mining company – the London and Limpopo Mining Company under Sir John Swinburne who brought the first ore-crushing plant. The quartz reefs quickly pinched out and the ore grades reduced so that gold mining became uneconomic, the costs of transport were prohibitive and the lure of the Vaal river diamond fields in 1869-70 proved too much for most of the fortune-seekers.

Before turning to the Victoria incident itself it is probably best to take a look at the preceding period that Galbraith calls the ‘Years of Disillusionment 1890-1893.’[ii]

British South Africa Company (BSAC) hopes mining prospects will attract new capital

The BSAC[iii] used the public excitement on the prospects for gold in Mashonaland to their own advantage. Its promoters never intended to use the Company’s very limited capital of one million pounds in trading, agriculture and mining operations.[iv] This made it very distinctive from all the other chartered companies in Africa as it intended to use its rights under the royal charter as: “concessions to others rather than direct activity of its own. Its profits would derive from the work of subcontractors. The company, in short, was a giant concessionaire.”[v]

For this purpose the whole of Mashonaland was open to prospecting by individuals, but the BSAC proclaimed through its early mining regulations that only limited companies could exploit gold bearing deposits with a standard condition that 50% of the shares of any syndicate or company would be awarded to the BSAC. In view of the complaints from settlers this requirement was changed after 1903 so individuals could work their claims on their own account on payment of a sliding scale royalty.[vi]

However in order to make Mashonaland attractive to concessionaires, it was necessary to supply infrastructure and administration –transport in the form of the railway from Mafeking and access to the East African coast at Beira and communications – in the form of the telegraph line and the British South Africa Company Police.

The early Pioneers and early settlers discover the gold fields are not what was imagined

Although thousands of gold claims are registered:

Mashonaland Gold claims in August 1893[vii] | ||

| ||

Salisbury (Harare) district | 3,560 |

|

Mazoe (Mazowe) district | 6,510 |

|

Lomagundi district | 2,600 |

|

Umfuli (Mupfure) district | 7,590 |

|

Victoria (Masvingo) district | 6,150 |

|

Manica district | 10,150 |

|

36,560 |

| |

The claim holders quickly discovered that gold in Mashonaland could not be picked out by hand. Yet their enthusiasm remained high. Adrian Darter at the end of 1891 observed: “… Such was the faith in the gold country that the officials thought that soon we would have several reefs eclipsing the Johannesburg main reef and that next season the country would be swarming with the population and we - equally sanguine - were scouring the country in search of these reefs.”[viii]

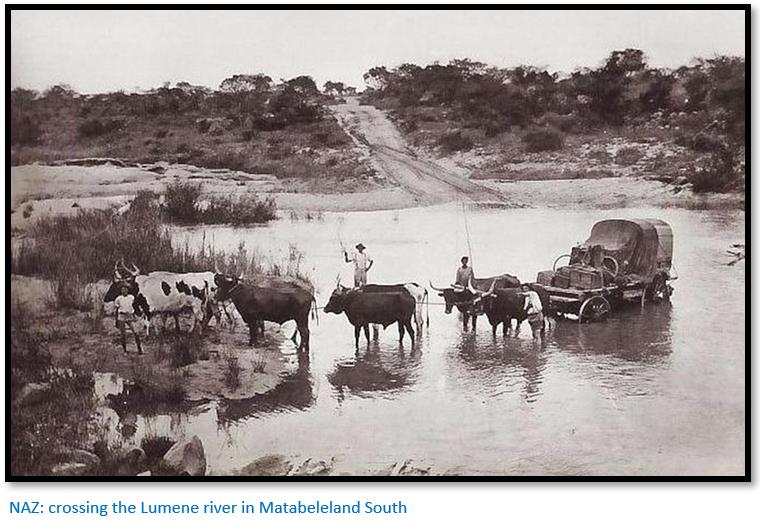

The obstacles were formidable. Mashonaland was over 1,600 kms from Kimberley which was connected by rail to Cape Town by 1885. Vryburg to the north was next connected by December 1892 with the Mafeking section under construction, but only completed in 1894. Until then supplies were transported by ox-wagon with long delays experienced particularly in the very wet season of November 1891 to March 1892. Bringing machinery by ox-wagon was both difficult and costly.

The rainy season of 1890 - 91

In the first year the summer rains were torrential.[ix] The wagon tracks became impassable, prices of food went sky-high and the settlers were threatened with starvation. Despite the chartered company’s best efforts the condition had come close to disaster and with it the realisation that a railway connection to the coast was the only solution – the railway via Mafeking was at best still years away from realisation. The firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow had advertised they would provide a transport and coach service from Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point on the Pungwe river to Mashonaland at much lower rates than those charged via Kimberley, but despite Maurice Heany’s best efforts the oxen were all doomed to die of tsetse-fly and the wagons were left abandoned in the veldt.[x]

Many worthless mining prospects are sold to the public

Mashonaland quickly gained a reputation for floating worthless mining companies and syndicates. The problem started with the chartered company’s intention to use its land and mineral concessions to attract capital into Mashonaland. Prospectors could obtain a licence to peg one alluvial claim and ten quartz reef claims for a small fee. The proviso was that evidence had to be shown that work had been carried out for which an inspection certificate was required.

To carry out further mining operations a company or syndicate had to be floated in which the chartered company had a 50% share. Claim holders were thus encouraged to sell their claims – whether there was payable gold or not – to companies which combined dozens of claims and sold them on the London stock exchange. The promoters in their prospectuses made all kinds of false promises with glowing sample assays and future mining operations which attracted many to the prospect of rich returns. But the public were soon disillusioned by the many failures and distrusted most Mashonaland mining ventures.

The Ayrshire[xi] is just one example of a mine with a very chequered past…over capitalised and subject to poor management. It is unlikely the holders of this debenture ever had their £50 capital returned.

The BSAC’s financial situation becomes increasingly perilous

Rhodes’ estimates of expenditure were always lower than the actual expenditure; loans from related companies such as De Beers were not disclosed on the balance sheet and the London directors began to fear that bankruptcy would result as they saw no immediate prospects of any meaningful revenue from Mashonaland.

Two major expenditure items were the British South Africa Company’s Police and the commissary system. The police force by the end of 1890 included 650 men at an average cost of £300 per annum, or £195,000 per annum. Major Tye, the senior commissariat and transport officer was requisitioning food supplies and transport far beyond what the directors thought was sustainable. £700,000 had been spent in the first year.

Rhodes initially ignored the directors demands for a general retrenchment, but by July 1891 the chartered company’s cash resources were down to £280,000 and he was forced to take action. Accordingly the police force was reduced to just about 100 men by the end of 1891 and only 40 men a year later. In its place the Mashonaland Horse, a volunteer force of 500 local men was organised.

The directors avoided a direct confrontation with Rhodes, but Major Tye became a target with the London secretary writing in January 1892: “the board cannot understand without further explanation how the affairs of the Company could have been allowed to drift into their present condition.”[xiii]

Rhodes was forced to turn to the reluctant directors of De Beers and Consolidated Gold Fields. De Beers[xiv] agreed to lend £3,500 per month in addition to the £70,000 already advanced. Gold Fields[xv] agreed to £500 per month which was matched by Rhodes. The total of £70,000 per year plus economy measures put in place saved the chartered company.

Rhodes works the financial press

The parlous state of the chartered company’s financial state was well hidden from the public. Journalists were paid to author favourable articles in 1891, particularly the Fortnightly Review and the Financial News with articles praising the wealth of Mashonaland and calling it the “New Eldorado” and writing that: “it was always expected that Mashonaland was rich in auriferous deposit, but it now appears that the reality exceeds the expectations.” [xvi]

James Johnston on his travels into Mashonaland from Tuli writes: “Many of the mining claims have not turned out to be such bonanzas as was expected: four syndicates have smashed up, dismissed their men and abandoned in disgust the fields that refuse to yield sufficient of the precious metal to pay working expenses; whilst almost every day we met bands of disappointed prospectors returning down country, poorer men than when they passed up, full of hope, a year or so ago. One graphically described things in general by remarking: “It ain’t no country for the white man anyhow, even if gold is there, where to live he has to be a-eatin’ of quinine all day long.”[xvii]

But not everybody is convinced and increasingly negative reports circulate

Henry Labouchere[xviii] in Truth described Rhodes as a pirate and the chartered company as a swindle. His newspaper was anti all chartered companies, but particularly the BSAC: “… the Charter of the British South Africa Company is unique in the history of such charters, and for this reason - that it was conferred, not upon a company of bona-fide traders, with territories in their possession, but upon a gang of speculators and company promoters, whose first object was, and is, to ‘boom’ their shares upon the stock exchanges of Europe and to sell for 50 shillings what cost them five - or less…”

Early reports such as that by Lord Randolph Churchill, a BSAC shareholder, were largely negative on Mashonaland’s prospects and attracted wide publicity in the Daily Graphic to which Churchill contributed paid articles. Henry Perkins, the mining expert who accompanied him stated there were some gold reefs that might make a smallholder a profit, there was nothing worthy of any large mining company.[xix]

Churchill’s newspaper reports concluding that Mashonaland would be a poor investment and that its emigration outlook was unpromising had a depressing effect on the BSAC’s shares which fell from £2.1s.2d at the beginning of 1891 to £1.1.2d in June and 12s 6d by February 1892.

The low share prices prompted Horace Farquhar and George Cawston, two BSAC directors, to hatch up a pool scheme to artificially raise the London share price. The riggers who would ‘work the press’ and persuade large holders of shares not to sell for a specific period would be paid £5,000 and receive share options. The only director not to agree to the scheme was Albert Grey, the others went along with it although it was clearly a plot to rig the market.

The BSAC’s right to the land increasingly also comes under question

The chartered company continued its somewhat perilous existence with the development of Mashonaland depending on speculative companies and syndicates that were expected to invest in return for mining rights and land grants. This policy depended on the chartered company’s right to dispense those rights.

The Foreign Office had given legitimacy to mining rights based upon the Rudd Concession, despite Lobengula subsequently repudiating the agreement.[xx]

But did the chartered company have land rights over Mashonaland? The Rudd concession in stating “to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence” prevented any future land concessions, but also gave no land rights to Rudd and his party.

So how did Renny-Tailyour, as the agent of Eduard Lippert, despite this clause in the Rudd concession, manage to persuade Lobengula to grant him the exclusive right for one hundred years to deal with all land in Mashonaland and Matabeleland? This concession was undoubtably granted because Lobengula wished to avenge himself on Rhodes for subsequently gaining the upper hand with the Rudd concession. He had to face many accusations from other concession-seekers who had a common interest in frustrating Rhodes’ party of Rudd, Maguire and Thompson and from his own izinDuna that he had “sold the land” to the BSAC.[xxi]

Edouard Lippert, an unsavoury character, through his agent Edward Renny-Tailyour in April 1891 allegedly obtained a concession from Lobengula granting exclusive rights to grant lands, establish banks, coin money and conduct trade within the territory of the chartered company on payment to Lobengula of £1,000 and annual payments of £500. The only witnesses to the concession were the inDuna Mshete and Renny-Tailyour’s colleagues. In addition, Lobengula was told the concession was for Theophilus Shepstone and his son “Offy” who he believed were his friends, so its validity was always in doubt.

The Adendorff Trek threat

The main threat to the question of land tenure at the time came however, not directly from Lobengula, but from a party of Afrikaners - the Adendorff or Banyailand trek was made up of Afrikaners who wanted to establish a Boer Republic across the Limpopo river in 1890 – 91.[xxii] Beach writes that in 1890 JLH du Preez and BJ Vorster stated that from 1874 the Shona Chiefs Chibi and Matibi had requested the Afrikaners to: “come and live with them to protect them from the murder raids committed on them by the nation of Moselekatze [Mzilikazi]”

On 24 June 1891, a group of armed Afrikaners under Col. Ignatius Ferreira assembled on the southern bank of the Limpopo and threatened to move into Mashonaland and proclaim a Republic by armed invasion. The leaders were arrested by British South Africa Company Police and Dr Jameson persuaded the remainder to disperse stating they were welcome to settle providing they obeyed the laws. Some members of the trek later settled peacefully in Mashonaland, the remainder dispersed.

The BSAC finally recognises it has no rights to land in Mashonaland

Lippert was always prepared to sell his concession to the chartered company if the price was right. Alfred Beit, Lippert’s estranged cousin, was tasked with the negotiations which went on for some time with both parties accusing the other of acting in bad faith. Eventually Rhodes conceded they had no rights to grant legal title to the farms that had been distributed to the pioneers and others.

Charles Rudd finally concluded the negotiations. If Lippert delivered a concession from Lobengula , however dubious, that the Foreign Office was prepared to recognise, he would receive in return 75 square miles (the Renny-Tailyour concession) in Matabeleland with all land and mineral rights and 20,000 shares of £1 in the United Concessions Company, plus 30,000 shares of £1 in the chartered company, plus £5,000 cash.

The Renny-Tailyour concession for land in Matabeleland

By October 1891 the chartered company had agreed to concede 75 square miles in Matabeleland, when publicly they were saying their interests lay only in Mashonaland. Of course, this was not revealed to Lobengula who still believed that Lippert was the chartered company’s opponent. Even the Foreign Office took part in the deception with Sir Henry Loch, High Commissioner for Southern Africa ordering John Moffat[xxiii] to cooperate and not give Lobengula any hint of the real situation.

In November 1891 in Moffat’s presence, Lobengula granted Lippert a concession for 100 years to lay out farms and townships and to charge rents in Mashonaland for £500 per year.[xxiv]

This was when John Moffat discovered the extent to which Lobengula had been deceived and the deceit behind the numerous concessions negotiated by the chartered company. He wrote to Rhodes that he would carry out his task, but: “I feel bound to tell you I look on the whole plan as detestable, whether viewed in the light of policy or morality.”[xxv] In 1893 at the start of the Matabele War he fell out with Rhodes.

The 1893 Matabele War was not a plan conceived by Jameson or Rhodes

Galbraith is quite clear that the chartered company did not have a plan to acquire Matabeleland’s land and resources through war, but he writes: “A variety of factors, some of which could not have been anticipated, created the environment for war.”[xxvi]

However, he goes on to say that when Jameson had the choice of peace or war in late 1893, his decision to go to war would have been influenced by the fact that Mashonaland as a “Second Rand” had proven to be a disappointment and the hope that Matabeleland would provide better opportunities.

Most settlers in Mashonaland believed the amaNdebele military system was incompatible with their and the chartered company’s economic objectives and there was never any doubt that sooner or later amaNdebele power must be crushed. But until 1893 both Rhodes and Jameson were inclined to avoid any collision between the two. The chartered company did not have the financial strength to wage war and there remained the possibility that Lobengula might lead his people north of the Zambesi river.

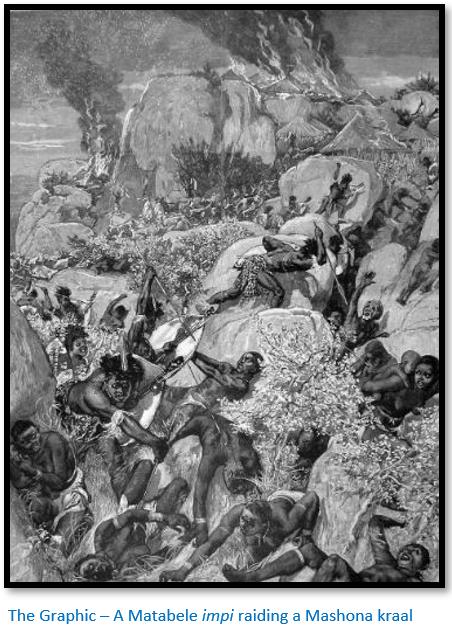

A clash however was inevitable. The chartered company needed complete control over Mashonaland without the hazard of amaNdebele raiding parties and the nearness of Matabeleland posed a real threat. Johnston in July 1892 says of the Banyai tribe near the Bubye river: “The Banyai natives are refugees from various tribes and have their kraals amongst the fastnesses of the hills, where they have been driven through fear of the Matabele. Like the Mashonas they are very poor, having been similarly plundered of almost everything they possessed by the raiding warriors of the Matabele, who not only seize their cattle, but take captive and enslave their women and children, assegaing their men.”[xxvii]

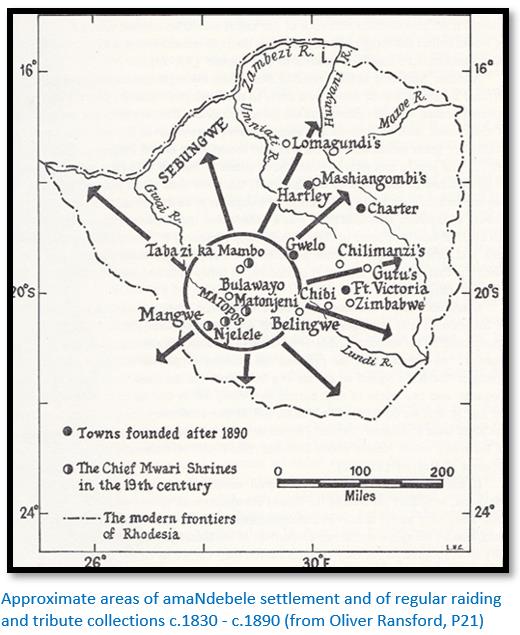

The entire area of Mashonaland was claimed by the amaNdebele, although it was not occupied by them and raiding had been carried out since Mzilikazi’s rule. Under Lobengula these raids continued as ‘expeditions of robbers’ with cattle, tribute and youths being seized, older men and women were simply slaughtered.[xxviii]

Sir Henry Loch, High Commissioner for Southern Africa, has ultimate administrative power and control

From the beginning Loch was concerned at the lack of administrative and judicial authority and two months after the occupation of Mashonaland he wrote: “If the mining population learn that they are not subject to any lawful authority, the place will become an Alsatia and a disgrace to civilisation.”

In 1892 he suggested annexation of the whole territory – including Matabeleland – as far as the Zambesi river and was supported by Sir Sidney Shippard, the resident Commissioner of Bechuanaland to ensure the region did not drift into a ‘state of anarchy.’[xxix]

However as far as Mashonaland was concerned, Loch did not wish to remove the BSA Company’s powers. Loch had some further suggestions, but these are outside the scope of this article.

The chartered company had very limited administrative capacity in Mashonaland

By the end of 1892 most of the British South Africa Company Police force had been discharged and its establishment was down to 40 men. The civil administration under Jameson was extremely small and the chartered company relied on the farmers and prospectors in the districts for civil order with field cornets elected by vote who were given the legal powers of magistrates.

The farmers and miners often intervened in local disputes, punished Mashona tribespeople for alleged offenses and forced them to work on farms and mines, sometimes swindling them out of their agreed wages. When clashes were brought to the attention of chartered company officials, they usually took the side of the settlers. The most notorious incident in March 1892, involved Charles F. Lendy, who we meet again during the Victoria incident.[xxx]

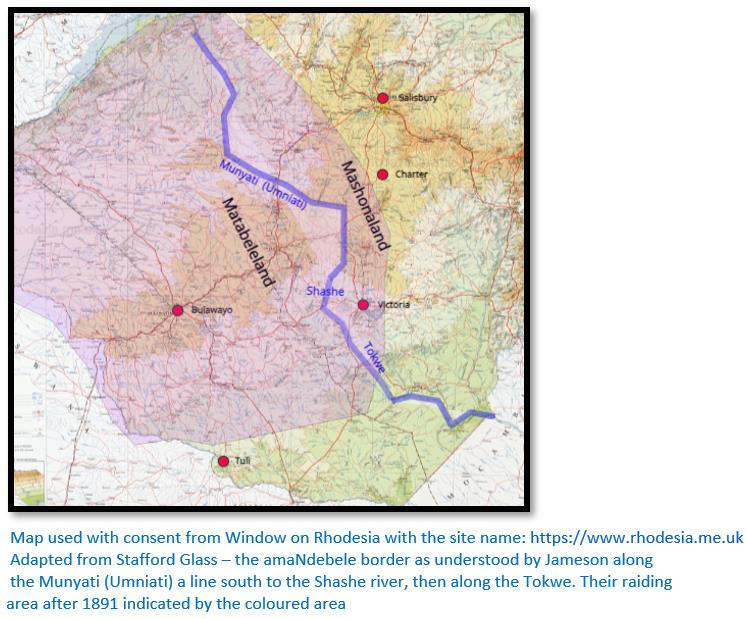

Jameson attempts to keep the peace by establishing a border with Matabeleland

Jameson was quite insistent that settlers should stay out of Matabeleland and that the amaNdebele should stay out of Mashonaland. His letters are clear:

2 December 1891 – urges Lobengula not to send impis to obtain tribute in Mashonaland

5 September 1892 – asks Lobengula to keep his impis out of the Victoria district

22 May 1893 – writes: “I have already explained to the King that bodies of his people crossing into Mashonaland might get into trouble.”[xxxi]

30 June 1893 – refers to: “the border agreed upon between the King and myself…the stipulated boundary.”

On 9 November 1891 James Dawson, the Bulawayo trader accompanied inDuna Malibamba to Salisbury with a complaint from Lobengula that prospectors were searching for gold too far to the west. Jameson was away, the complaint was made to Andrew Duncan, the acting Administrator.

Galbraith writes that Jameson believed that although Lobengula did not explicitly agree to ‘the border’ as shown above, he did accept it as a de facto divide between Mashonaland / Matabeleland.[xxxii] However in reality it appears that Lobengula’s understanding was that it represented a border for settler gold prospecting, but not for the raiding of the Mashona.

Lobengula, the peacemaker

The Pioneer Column had accomplished its mission in the second half of 1890 without being harassed by the amaNdebele, although small scouting parties tracked their presence. Adrian Darter[xxxiii] called Lobengula the pioneers ‘best friend’ and their ‘uncanonised saint.’ Lobengula after the Inxwala or ‘big dance’ of February 1891 had not hurled his spear in the direction of Mashonaland, despite the hopes of his young warriors (majakas) The first year was trouble-free and “the Matabele question seemed to have died a natural death” with most settlers having no fear of conflict with the amaNdebele although there was nothing to suggest that Lobengula: “had in any way renounced his ownership of Mashonaland, nor given up one iota of his power over the lives and property of the inhabitants of that territory.” [xxxiv]

Jameson however, assumed that occupation implied both possession of Mashonaland and authority over its people – two contrasting views that were bound to result in a collision.

Lobengula asserts his authority in Mashonaland

In June 1891 A.J. Leonard wrote that ‘the Matabele question’ seemed to have: ‘died a natural death’[xxxv] This turned out to be premature as on 1 December 1891 some of Chief Lomagundi’s people arrived in Salisbury to report that the chief and three of his advisers had been killed by an amaNdebele impi. Next day Jameson wrote to Harris saying that Lomagundi had been in the habit of walking every year to Bulawayo to pay his annual tribute to Lobengula. “Not having done so this year a small party of Matabele…was sent to demand his presence and the annual tribute.” When Lomagundi refused, he was killed along with his advisers.

Jameson wrote: “This, of course, is unfortunate, but in accordance with Lobengula’s laws and customs.”[xxxvi]

Lobengula’s explanation for the killing shows that he believed his authority still extended to Mashonaland: “I sent a lot of my men to go and tell Lomagunda to ask you and the white people why you were there and what you were doing. He sent word back to me that he refused to deliver my message and he was not my slave - this is why I sent some of my men to go and kill him. Lomagunda belongs to me. Does the country belong to Lomagunda?”

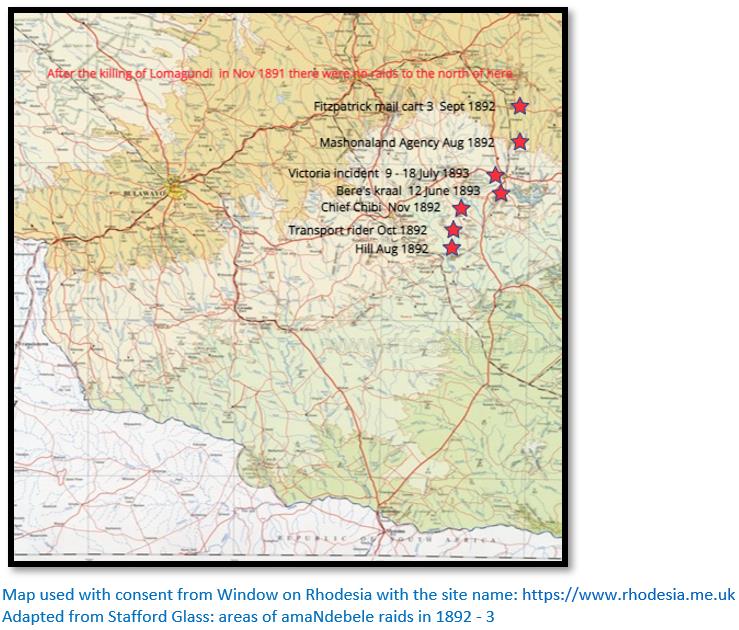

Lomagundi’s defiance of Lobengula is important because it shows that in some Mashona eyes they no longer believed they were amaNdebele slaves (Maholi) However by accepting the chartered company’s protection they were creating friction between the chartered company and the amaNdebele. From then on the northern plateau land of Mashonaland would be given a wide berth by the amaNdebele who would concentrate their raiding on the area between Fort Charter and Tuli.

Prospectors, hunters or traders who crossed into Matabeleland received no sympathy from Jameson if they were robbed or molested.

James McDonald (later Sir)[xxxvii] was in the Naka Hills, south west of Victoria in 1892 when he and his companion were surrounded by an amaNdebele raiding party of 400 warriors who robbed his carriers of all their possessions. Although they took nothing from McDonald and his companion: “they gave us a very bad time, repeatedly threatening to kill us and ordering us to return to Victoria at once and give up looking for gold to the west of that place.”[xxxviii]

On 15 March 1893, two traders Edkins[xxxix] and Shackleton left Victoria with a scotch cart and travelled west. Johan Colenbrander on behalf of Lobengula wrote to Jameson: “They got amongst the Amandebele and were fairly robbed. One of the gentlemen wrote to Loben to complain, upon which the King ordered them here. Only one man arrived today, Shackleton having died of fever on the 9th of this month. The King is very much annoyed that you allow strangers into his occupied country without first getting permission from him. He says, however, that he is sure that you know nothing of this particular case as the men say so, but he says will you be good enough to prohibit altogether anyone from trading or let them get his permission through yourself first as he says serious difficulties may arise between your people and his own warriors if you allow your men to roam around in this fashion.”[xl]

In April 1893 a party referred to as ‘the Becker’s and their companions’ went west from Inyazitza[xli] and had their possessions looted by the amaNdebele. The acting chartered company secretary wrote to the field cornet at Inyazitza: “Doctor Jameson understands that the Becker’s and their companions were warned before leaving Victoria not to cross the Sebakwe river and therefore any loss there may have been put to is entirely due to their own disobedience of orders.”

The border becomes official and settlers are discouraged from entering Matabeleland

Following these incidents in May 1893 Jameson wrote to Charles Vigers, then Civil Commissioner at Victoria: “You will also be good enough to make the residents of your district understand that they are not to go into Matabeleland; if people persist in doing so and get into trouble, the company will take no steps whatsoever to assist them but will severely punish anyone caught on the border.”

At the same time Jameson replied to Colenbrander: “Please tell the King that all the white people in Mashonaland have strict orders not to enter his country…my police and magistrates in each district have strict orders to prevent any white people going beyond our recognized line…I am determined not to have trouble between the King’s people and ourselves through the recklessness of individuals and they should be punished in each case.”

Jameson’s border policy was intended to protect Victoria

The settler population around Victoria had grown considerably and many were occupied in farming and mining. On 5 September, Hugh Marshall Hole, then acting secretary for the Administrator, wrote to Lobengula: “that the Victoria District is now becoming thickly populated with white men, and that it is advisable that he should prevent his impis from going in that direction...Dr Jameson further desires me to point out that individual Matabeles proceeding to work in the country are always welcome, but that he feels sure these apparently warlike bodies which are often not sufficiently under control, are likely to occasion trouble, and this he is anxious to avoid.”[xlii]

Jameson hoped with the border agreed, amaNdebele / settler relations would remain peaceful. The amaNdebele might enter Mashonaland if they came to work or trade, but raiders would be turned back and if vassals failed to pay tribute, negotiations should be through the administration.

Others believed the chartered company wanted peace with the amaNdebele

The company had every reason to preserve friendly relations with Lobengula as he had not hindered their passage to Mashonaland and its development required all the resources of the chartered company. In 1891 Rutherford Harris, the company’s South African secretary, had assured John Moffat that they intended to take good care and avoid any provocations that would arouse Lobengula’s hostility.

As late as 7 July 1893, two days before the ‘Victoria incident’ Herbert Canning, the company’s London secretary, told the Colonial Office: “that the well-being, if not the existence, of the company depended on its being able to carry on undisturbed its present work of peaceful development.”[xliii]

Stafford Glass maintains the border policy was destructive for the amaNdebele

An unofficial border was something the settlers could comprehend; the Pioneer Column had taken a route that avoided amaNdebele territory, although it was within their area of raiding on vassal tribes. It suited the economic and political needs of the settlers and they knew where the border lay having been told publicly on numerous occasions…the robbery of traders who crossed into Matabeleland would also have been public knowledge.

However Glass maintains that Jameson did not appreciate the significance of the amaNdebele raiding system which had flourished under Mzilikazi but had been checked by the arrival of the settlers in 1890. In addition, the amaNdebele had been told that the settlers had only come to dig for gold, but clearly much more was happening in Mashonaland and amongst its indigenous people. Lobengula’s sovereignty over that region had clearly been challenged.

The Mashona tribes according to Lobengula: “were his and his peoples, their slaves and their cattle…Any interference with them by the whites was anathema to him…The Matabele could do what they liked with them and any action they took must not be questioned by the whites. Are the Amaholis[xliv] then yours? Lobengula asked of Jameson in later crucial days when the pioneers rescued them from his impi at Victoria.”[xlv]

In the background the settler population is restive

Galbraith writes that supplies were short, inflated prices were a source of much grumbling. Many settlers were disillusioned by 1893 – fortunes were not being made from gold and farming life was tough and unpredictable. Naturally blame was heaped on the chartered company. James Johnstone[xlvi] visiting Mashonaland at the time writes: “that business was stagnant, bankruptcies frequent, and indignation at the company’s deception at fever pitch.”[xlvii]

Rising tensions in the Victoria district

The men of a local Shona Chief living near Fort Victoria had stolen cattle from other Shona, who were tributaries of Lobengula and holding cattle on Lobengula’s behalf. On 11 June 1893, Lobengula sent a “small impi” – some 70 men – from Bulawayo to recover these cattle. This impi was reported to be raiding about ten miles from the town. Lendy rode out to meet them, allowed the cattle to be taken back to Bulawayo, and sent a letter with the impi for Lobengula, warning in polite language about sending his impis into Mashonaland.

At the Newton enquiry on 26 May 1894, Thomas Arthur Chalk, a Sub-Inspector in the BSA Company’s Police stated concerning this incident: “Was in Victoria last July, was then Second Class Sergeant in the Company’s Police. Before the 9th July an impi had been close to Victoria raiding. I accompanied Captain Lendy to interview the Induna of that impi. Captain Lendy spoke to him and told him they were coming too close to Victoria. He also gave him a note to Lobengula from himself. He wrote it there himself when we met the impi. He explained to the Induna he was Lobengula’s friend. Lobengula had given him the road to Bulawayo and in the note he wrote words to the effect that the impi was coming too close to the town of Victoria. The Induna said he would deliver the note and would take the impi away. We left him; we did not hear of them close to Victoria again.”[xlviii]

James Johnston in 1892 wrote about local settlers’ scepticism on how long the uneasy peace with the amaNdebele would last: “By four o’clock we had covered the fifteen miles to Victoria, of which place there is little to say, except that there are several temporally built stores and a few police of the British South Africa Company. But why so few are there, no one knows. A foolhardy confidence is placed by the company in the professed friendship and pacific attitude of Lobengula toward the English; but those who best know the crafty old chief of the Matabele declare that an attack on the Europeans is inevitable and that at no distant date. For even now, although Loben is receiving a pension of £100 a month in gold, his younger braves are fretting like sleuth-hounds in the leash for liberty to – as they say – wipe out the white invaders of their country.”[xlix]

Neither Jameson nor Lobengula want conflict in 1892 – 3

In July 1892 an amaNdebele impi had raided Mashona territory as the tribute said to be owing had not been paid. Jameson wanted Lobengula to understand that the amaNdebele should no longer expect tribute from the Mashona who could hardly be expected to pay tribute to Lobengula and hut tax to the chartered company.

Henry Paulet[l] reported the inDuna in charge of the impi maintained tribute had been paid annually for a long period, but his ‘humble and civil’ attitude confirmed Lobengula had warned him not to cause any clash with the chartered company.

Jameson, on the other hand, did not directly challenge amaNdebele rights over the Mashona and concentrated on avoiding the disruption to mining and farming of amaNdebele raiding and to keeping them away from settlements, such as Victoria.

Lobengula issued strict instructions that settlers were not to be molested and they were strictly obeyed by any raiding parties that came across settler travellers. There was some cutting of telegraph lines – the copper wire being ideal for making bracelets – with the people in Chibi’s country blaming the amaNdebele. Lendy was sent to Bulawayo to request punishment of the offenders if this was correct. Lobengula agreed and requested that settlers stop shooting hippo, which were sacred animals and also requested the 1,000 additional Martini-Henry rifles had been promised to him if gold was discovered in Mashonaland. Jameson agreed to use his best efforts in regard to shooting hippos and enquire about the rifles.

In May 1893 another incident of telegraph wire cutting incurred and the BSA Company police seized cattle from a Mashona headman that actually belonged to Lobengula. Lobengula protested to Sir Henry Loch and Jameson with the latter promising they would be returned.

AmaNdebele raiding continues - the policy of mutual restraint cannot endure

In June 1892 Jameson reported to Harris: “Two parties of these Matabele have been interviewed by Captain Chaplin and explained that they were there by the orders of the King and were collecting such tribute as was due to Lobengula prior to the white occupation of the country.”

FBS Wrey, the consulting engineer to the Mashonaland Agency said one of these parties passed through their camp 22 km from Victoria and the 150 natives they employed: “were absolutely paralysed with fear and announced their intention of leaving directly…only with great trouble and persuasion that they were induced to remain and our position was a most false one: for as the natives very plainly said: when you white men came into Mashonaland, you promised that if we worked for you, you would prevent the Matabele from raiding us. Here we are working for you and here are the Matabele killing our wives and children and raiding our homes.”[li]

In August 1892 the first instance of a settler being stopped on the road between Tuli and Victoria was reported by The Rhodesian Chronicle: “a Mr Hill was stopped 12 miles to the north of the Nuanetsi by an impi of 200 – together with a large force of Makalaka women taken from kraals in the neighbourhood where they had been raiding.” The article went on to say Mr Hill’s rifles had been stolen and he was refused permission to continue until he had ‘given them bonsellas of tea and coffee.’

On 6 September 1892 George Fitzpatrick, the conductor of the mail cart, telegraphed from Charter that 30 Matabele had stopped his cart and taken what they wanted. The robbery occurred at sundown on 3 September about 20 km north of Makori’s post station when he, along with a two settlers and three natives met a party of about 30 armed natives sitting on the road. When the headman asked for a present, he was told to ‘clear off’ whereupon guns were aimed at Fitzpatrick and several blankets and overcoats taken from them. The headman said they were from Bulawayo and were raiding kraals to the south-east of Makori’s along with a larger impi some distance off. When told he was robbing the mail cart and Lobengula would hear of it, the headman only laughed.

When informed, Harris told Colenbrander to inform the King: “he must restrain his people from interfering with the whites and that he should not allow his people to upset the parts of the country we are occupying but keep further away from us.”[lii]

In October 1892 a transport-rider between the Lundi (Runde) and Nuanetsi (Mwenezi) rivers was robbed: “all his goods were taken, he himself being ill-treated.”

In the following month Lobengula sent an impi to punish Chief Chibi – he was captured, taken to Bulawayo and reportedly skinned alive. Lobengula’s answer to Jameson followed the usual format: “some cattle had been stolen and his impi was told not to interfere with the white men.”

On 11 June 1893 fleeing natives said that the amaNdebele were raiding 16 km south of the town. Lendy accompanied by a sergeant, two troopers and an interpreter set out to investigate and next day: “three or four men from Bere’s kraal came up and said the Matabeles had raided them, taking all their cattle, women and children and killing several of them.” This small impi of about 70 majakas (young warriors) had been sent by Lobengula because Bere had allegedly stolen 30 of his cattle. They had been told: Go and get the cattle back but be very careful to touch nothing belonging to the white men.”[liii]

Local newspapers reflect the public opinion

The Rhodesian Chronicle had a leading article on 17 September 1892 declaring: “The traveller cannot consider himself free from the chance of a possible meeting with the Matabele. Demands for presents have been made with increasing insolence and peremptoriness.”

The writer of the above was grateful the chartered company was encouraging settlers as farmers: “But, the question arises, are the authorities doing their best to protect these settlers from raids of the Matabele?...the manner in which wandering bands of Matabeles have recently treated travellers has been the cause of some alarm and uneasiness in the country.”

Despite Lobengula telegraphing Rhodes to say settlers had nothing to fear, the chartered company believed the raids called into question their ability to protect the Mashona and severely disrupted the economy – both mining and farming required stable conditions and available labour. In addition the settlers were agitated about amaNdebele incursions into the Victoria district.

The article pointed out that action was always taken by the chartered company against Makalakas. If they stole an ox, the settlers heard of “expeditions being organized to shell and destroy some village.[liv] Yet the Matabele could plunder travelers with impunity and at the most, a timorous remonstrance is sent to Lobengula…The Matabele will naturally look upon their treatment as a tribute to their power and unless the BSA Company changes its present policy of bullying the weak and cringing to the powerful, they will not be able to avert trouble with the Matabele, which will be the consequence of the death of Lobengula.”

Jameson telegraphed Rutherfoord Harris saying that although there was no real threat to the settlers, “unless something is done”[lv] it was difficult to get the Mashona to return to paid employ even when the raiding parties had left the district.

However there was still the view of Salisbury residents – who were not being raided – that the frequent raid alarms from Victoria were being exaggerated and that they were unnecessarily panicky. Even at the start of the raid of July 1893 Jameson was to say that the residents of Victoria had the ‘jumps.’

Jameson abandons his policy of restraint

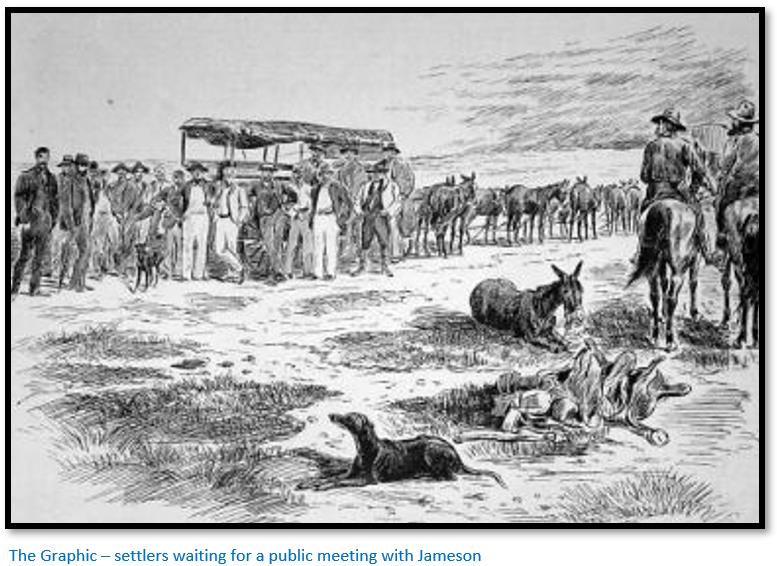

On 15 July 1893 at a public meeting held in Salisbury where heated speakers one after another demanded that Jameson stop putting off action with the amaNdebele and threatened to deal with them themselves supported by 500 Boers from the Transvaal. Two days later Jameson abandoned his policy of restraint and telegraphed Rhodes saying the chartered company must deter the amaNdebele with a show of force and drive them off and received Rhodes’ reply in agreement that added: “if you do strike, strike hard.”

Clearly his mind was made up when he met the inDuna Manyao on 18 July 1893.

Jameson’s orders to Captain Lendy once the meeting broke up were: “If they resist, shoot them” and although the amaNdebele offered no resistance once met, Lendy ordered his men to open fire.

When the patrol returned to Victoria, an eyewitness reported the settlers lining the walls[lvi] gave cheer after cheer at the sight of the amaNdebele shields and assegai’s being carried by the patrol.

The ‘Victoria Incident’ gives the excuse for the 1893 Matabele War and invasion of Matabeleland

On 19 July 1893 Jameson wired Harris: “We have the excuse for a row over murdered women and children now and the getting Matabeleland open would give us a tremendous lift in shares and everything else. The fact of its being shut up gives it an immense value both here and outside.” [lvii]

The Victoria incident continues with the article The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’

References

Alan Doyle. The lower Sunbury Lendy Memorial

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Carter. The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

Stafford Glass. The Matabele War. Longmans Green and Co, 1968

James Johnston. Reality versus romance in South Central Africa : An account of a journey across the continent from Benguella on the West, through Bihe, Ganguella, Barotse, the Kalihari Desert, Mashonaland, Manica, Gorongoza, Nyasa, the Shire Highlands, to the mouth of the Zambesi on the East Coast. Hodder and Stoughton, 1893

Notes

[i] See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[ii] Crown and Charter, P255

[iii] The terms British South Africa Company (BSAC) and chartered company are both used in the article

[iv][iv] Crown and Charter, P256

[v] Ibid, P122

[vi] See the article The British South Africa Company and the impact of early gold mining regulations on smallworkers under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vii] From Rhodesia of Today by Edward Knight

[viii] Adrian Darter. The Pioneers of Mashonaland. P111

[ix] William Hervey Brown in his book On the South African Frontier writes (P140): By December 1st the rainy season was fully upon us. Such continuously wet weather I had never encountered. Both day and night the sky was over-cast with heavy clouds and showers occurred at almost hourly intervals…The surrounding country soon presented the appearance of one vast frog pond.”

[x] For an overview see the article The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfiledguide.com

[xi] Rhodesian Study Circle. D.A. Mitchell & GW Begg. The Gold Mines of Southern Rhodesia selected mining and postal histories to 1924

[xii] Photo from C. Harding Far Bugles published by Simpkin Marshall, London 1933. Major Carden succeeded Colin Harding in 1906. I am not sure what the initials BCF carved on the tree stand for

[xiii] Crown and Charter, P263

[xiv] De Beers in 1893 received the exclusive right to exploit any diamondiferous ground within the chartered company’s control

[xv] Gold Fields in 1894 received the right to 250 gold claims in Matabeleland and an option for 51,000 morgen in farms of 5,000 morgen each at a maximum cost of £50 each

[xvi] Crown and Charter, P265

[xvii] Reality versus Romance in South Central Africa, P289

[xviii] See the article Contemporary criticism of the British South Africa Company (BSAC) in 1889 – 90 from Henry Labouchère the editor of the journal Truth under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xix] See the article Lord Randolph Churchill’s visit to Rhodesia in 1891 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xx] See the article Were Lobengula and the amaNdebele tricked by the Rudd concession under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xxi] See the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xxii] See the article The Adendorff trek and the planned invasion of Banyailand under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xxiii] John Moffat, son of the famous missionary, Robert Moffat, in 1884 became the Assistant Commissioner to Sir Sidney Shippard in Bechuanaland (Botswana) From 1887 to 1892 he was a representative of the Chartered Company in Matabeleland.

[xxiv] 30 years later the judicial committee of the Privy Council stated the concession only made Lippert an agent for Lobengula and gave no right to sell the land and charge rents. They decided the land belonged to the Crown rather than the chartered company, but the decision was academic. Lobengula was long dead and much of the Mashonaland had been sold.

[xxv] Crown and Charter, P276

[xxvi] Crown and Charter, P287

[xxvii] Reality versus Romance in South Central Africa, P246

[xxviii] The Matabele War, P6

[xxix] The Matabele War, P20

[xxx] Lendy was in command of a patrol that went to Chief Ngomo’s kraal in Chief Mangwende’s district east of Salisbury (now Harare) James Bennett, a farmer and trader who had his store near Ngomo’s kraal, had been robbed several times and when he protested to Ngomo’s son, who he believed was behind the break-ins, Ngomo’s son called upon the people to “kill the white man.” Bennett managed to escape and laid a charge of attempted murder. Previously a wagon driver had been murdered in the area, the case was still unsolved and there had been other cases of theft and violence in the vicinity. Lendy and his patrol went to Chief Mangwendi’s kraal and demanded that Ngomo come with them to Salisbury for trial. The Chief said he did not have the means to force Ngomo, but he hoped Lendy would punish Ngomo.

Chief Mangwende provided two guides to lead Lendy’s patrol to Ngomo’s kraal, built on a kopje and local people, including Mangwende, was that Ngomo would violently resist. Ngomo refused to co-operate and Lendy returned to Salisbury for instructions. On his second visit Lendy’s report stated: “Day had fully dawned before the natives became aware of our presence and catching sight of some of the mounted men, one man in the kraal, presumably Ngomo himself, shouted out to the others to come on and kill the white men. A well- directed shot from the seven pounder was the signal for the firing which was pretty general on both sides for some minutes.” Return fire came in the form of bullets, pot legs and stones fired from muzzle-loaders and in the ensuing shoot-out 21 tribesmen were killed, including Chief Ngomo. Jameson insisted that Ngomo was killed, not for theft from Bennett, but for war-like opposition to law and order.

[xxxi] The Matabele War, P38

[xxxii] Crown and Charter, P290

[xxxiii] Adrian Darter, a pioneer was author of The Pioneers of Mashonaland

[xxxiv] The Matabele War, P32

[xxxv] A.J. Leonard. How we made Rhodesia, P183

[xxxvi] The Matabele War, P49

[xxxvii] Sir James McDonald, author of Rhodes, A Life became general manager of the Gold Fields Rhodesian Development Company. Came to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) in 1891, stayed 40 years and accompanied Rhodes on many of his travels in the country.

[xxxviii] The Matabele War, P33

[xxxix] Ebenezer Crouch Edkins was murdered along with 27 others in the Filabusi district on 23 March 1896. See the article Filabusi Memorial and the Edkins Store killings under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xl] The Matabele War, P34

[xli] Inyazitza was a post station between Makori to the south and Fort Charter to the north and situated on the headwaters of the Sebakwe river

[xlii] The Matabele War, P37

[xliii] Ibid, P39

[xliv] Maholi was a term used by the amaNdebele to describe their “slave people” who comprised men and women that had been captured during impi raids

[xlv] Ibid, P46

[xlvi] James Johnston – author of Reality versus Romance in South Central Africa - his journey in 1892

[xlvii] Crown and Charter, P289

[xlviii] F.J Newton report on the collision between the Matabele and forces of the British South Africa Company at Fort Victoria in July 1893

[xlix] Reality versus Romance in South Central Africa, P257

[l] Wikipedia: Henry Paulet inherited the title of the 16th Marquess of Winchester

[li] The Matabele War, P52

[lii] Ibid, P55

[liii] Ibid, P67

[liv] Probably a reference to Lendy’s Ngomo kraal incident

[lv] Crown and Charter, P297 – telegram Jameson to Harris 17 July 1893

[lvi] See the photo in the article The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’

[lvii] Crown and Charter, P298 – telegram Jameson to Harris, 17 July 1893