Postal service in 1890 – 1892; the post-stations from Fort Tuli to Salisbury

Much of the detail, particularly quotes, contained below comes from the article by Dave Collis titled The Thin Red Line; Tuli to Salisbury which was kindly lent to me by The Rhodesia Study Circle. The many quotes were sourced by Collis from the National Archives of Zimbabwe and cover the changes in the mail service until the 1894 winter season when the Matabeleland routes dominated and services on the Tuli—Salisbury route ceased. The quotes used in this article have been supplemented by information from the postal histories listed under references.

Mafeking – Gubulawayo runner post

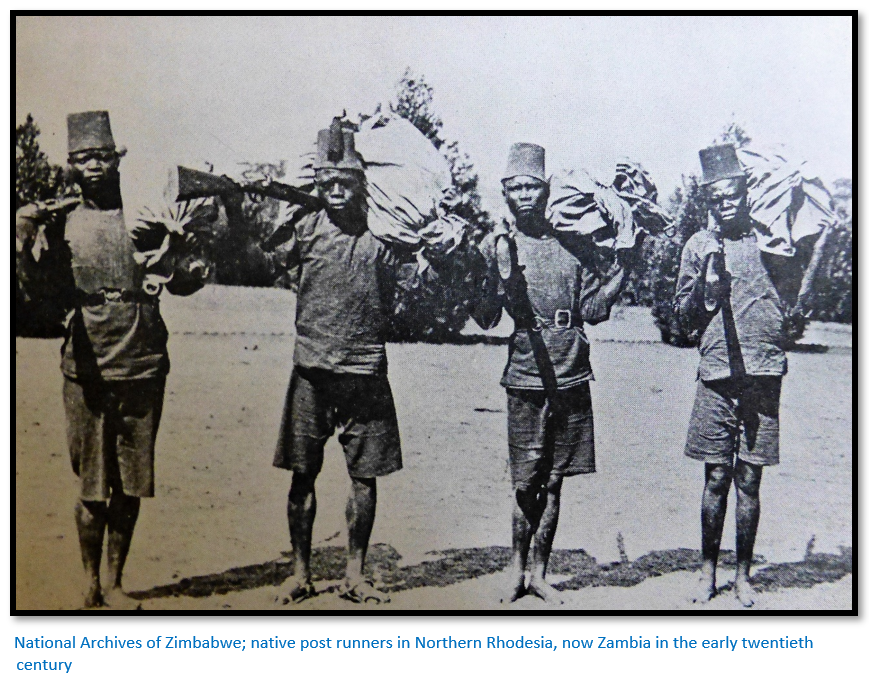

In the nineteenth century isolated missionaries such as Robert Moffat at Kuruman, Sykes and Thomson and later C.D. Helm who were all initially at Inyati Mission, now Inyathi and then at Hope Fountain and were forced to depend on traders and hunters to bring on their mail with them as they were situated hundreds of kilometres from the nearest towns.

They operated a private service whereby local traders, hunters and the missionaries paid an annual subscription or in the case of a temporary stay, by letter. Pairs of runners took the letters to the nearest Government Post Office or Postal Agency.[i]

The first postal service in the region was that operated by John S. Moffat, Assistant Commissioner of Northern Bechuanaland and son of Robert Moffat, who inaugurated a regular system of mail runners between Mafeking and Gubulawayo on 7 August 1888 and for which Bechuanaland postage stamps were used. It lasted for a year before being superceded by a mail cart service. Contracts were made for five postal agencies north of Mafeking: at Kanye, Molepolole, Shoshong, Tati and Gubulawayo; with the total cost to the Cape Colony not to exceed £300 per annum. It ran weekly between Mafeking and Shoshong and fortnightly between Shoshong and Gubulawayo. John Moffat at Palapye, Sam Edwards at Tati, Rev H. Schulenburg at Shoshong and Rev Charles Helm at Gubulawayo were appointed postmasters with date stamps marked “Bechuanaland.”

The pair of runners from Gubulawayo travelled to Tati a distance of 177 kms (110 miles) before new runners took over. As the settlement at Gubulawayo grew the post office at Hope Fountain was transferred to Dawson’s store.

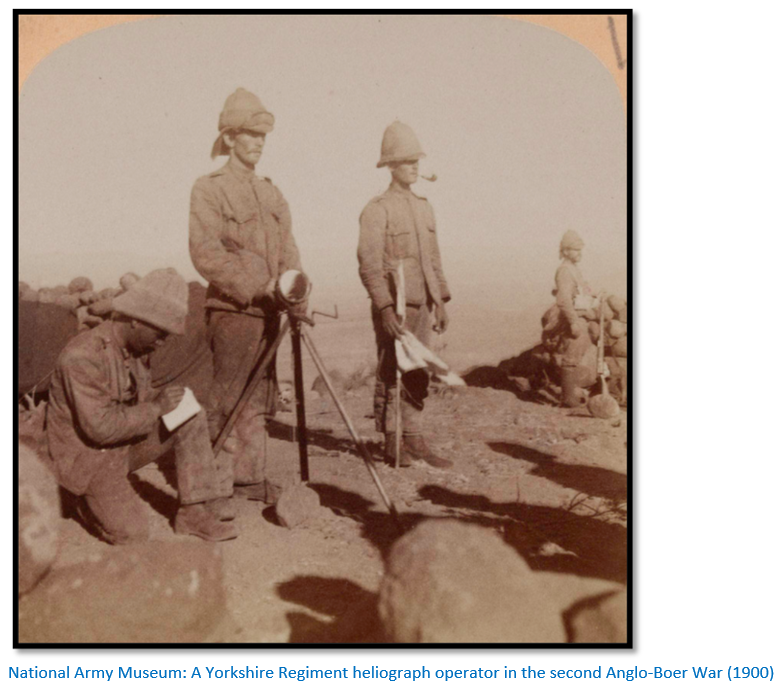

Heliograph system between Palapye and Fort Tuli

Prior to the occupation a heliograph signalling system, which uses a mirror to reflect sunlight to a distant observer, was in operation. By moving the mirror, flashes of light could be used to send morse code making it an ideal tool in the vast open spaces of country where the operator could quickly set up a position on high ground, or a kopje. In 1890 there was a telegraph line as far as Palapye, from there heliograph stations in present-day Botswana operated from Palapye to Macloutsie (193 kms) and were manned by the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) and from Macloutsie to Fort Tuli (97 kms) they were manned by the British South Africa Company (BSACo) Police. There were three heliograph stations between Macloutsie to Fort Tuli each about 32 kms apart.[ii]

In practice, problems were encountered with the heliograph system as there could be morning mist, or cloudy weather conditions, or a heat haze during the day which also disrupted signalling.

The heliograph continued in operation for some time as Major Leonard states: “24 December [1890] at midday, I received the following helio from Pennefather who has evidently left Palapye: “Expect me Friday. Tell Hannay to look after Maxim guns. Graves must go at once to Fort Victoria. Turner must remain at Fort Charter until further orders. A Troop must concentrate at Salisbury and your Troop must go there when relieved at Charter by B Troop. Shew these orders to Tye and forward by special messenger to each fort. Faulkner must continue to strengthen Victoria.”[iii]

The British South Africa Company

Communications and the postal service in the early days of the occupation of Mashonaland were operated by the BSACo Police with the BBP covering present-day Botswana.

Instructions to the BSACo’s acting Administrator, A.R. Colquhoun regarding the mail services to be established were very general: "An arrangement should be made with the authorities at Vryburg, for the conveyance of mails from the Bechuanaland Protectorate border southward, and vice versa, and a supply of Bechuanaland Protectorate stamps taken with you for issue in Mashonaland.

![]()

![]() A regular Postal Service should be established between Mashonaland and the Bechuanaland Protectorate border.”[iv]

A regular Postal Service should be established between Mashonaland and the Bechuanaland Protectorate border.”[iv]

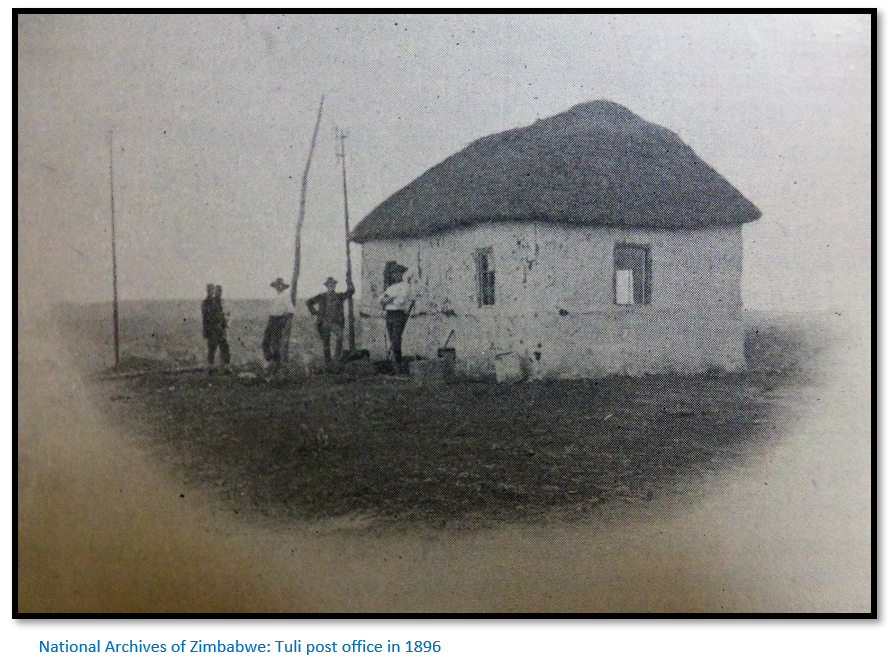

Post Stations are established

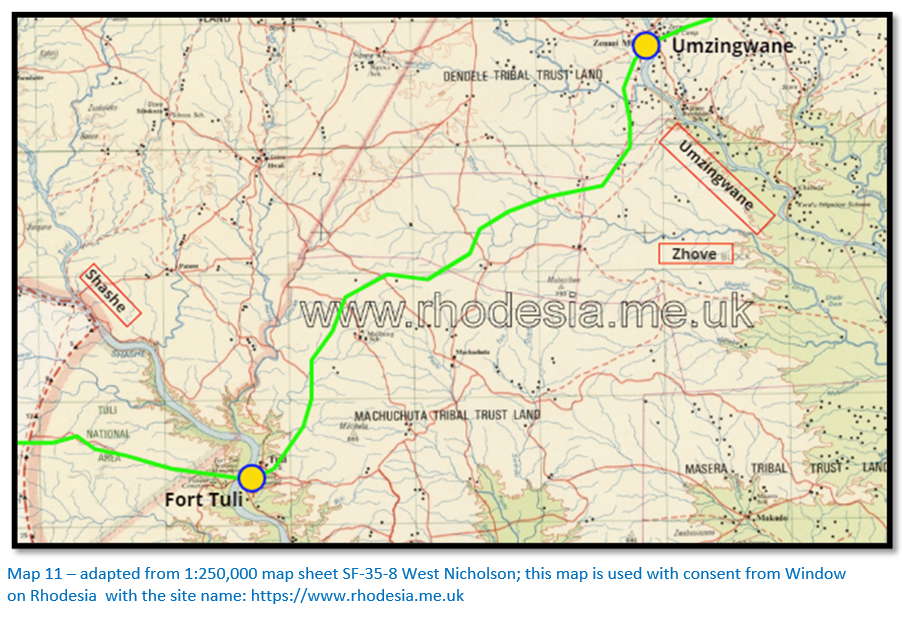

The Shashe river was crossed by the Pioneer Column on 11 July 1890 and postal communications were required firstly with the advancing column as it moved away from Fort Tuli and from 13 September 1890 with Fort Salisbury.

The Pioneer Column was only at the Umzingwane River just 50 kms (30 miles) from Fort Tuli when both Lt-Col Edward Pennefather, commanding officer of the BSACo Police and A.R. Colquhoun, the acting Administrator reported separately to Kimberley.

Pennefather wrote:

“I cannot provide communication on this line with the force now at my disposal: I haven't half enough men with me, so you must take your chance of information. I will try and get the Banyai to run the post for us. As soon as Willoughby comes, I shall have to send him down again to open communications on the line, but it will be absolutely impossible to keep it open in the wet weather.”[v] An accurate prediction of things to come!

Colquhoun wrote from the Umshabetsi [Mtshabezi] river: “I am arranging with Pennefather to have a Scotch cart and trotting oxen postal service between Macloutsie Camp and Tuli Camp; also endeavouring to establish a runner service from the Tuli camp northwards through the Makalaka villages which will be subsidised for the work. These arrangements are to be replaced later on by something more substantial.”

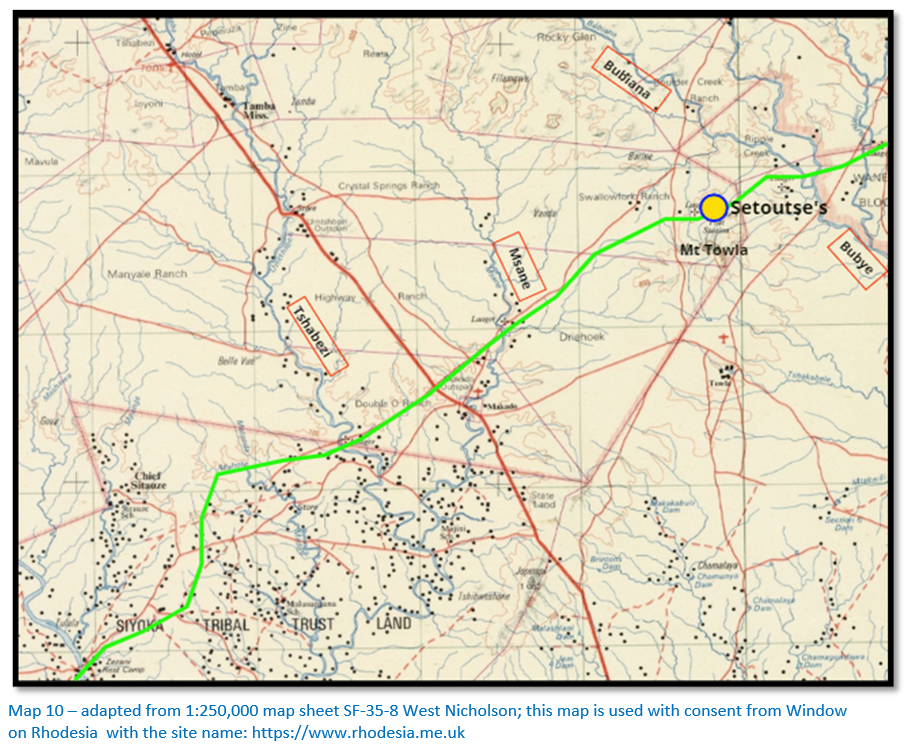

Just a day later Pennefather had changed his mind about using Banyai and Makalaka runners as he wrote a letter dated 18 July 1890 from “the front” to Willoughby at Macloutsie, instructing him to establish "block houses and a system of post service, at the Umzingwane River, and at Setoutse's on the Bubye River."

Willoughby was to report on the 1 August 1890 as he marched upcountry after the main column: "Movements of the second convoy, 35 miles from Tuli at Umzingwan (sic) post station. I have established a post station here of six men in a splendid position commanding the water and the drift, so if any convoy were attacked while crossing, they could afford a great deal of assistance.”

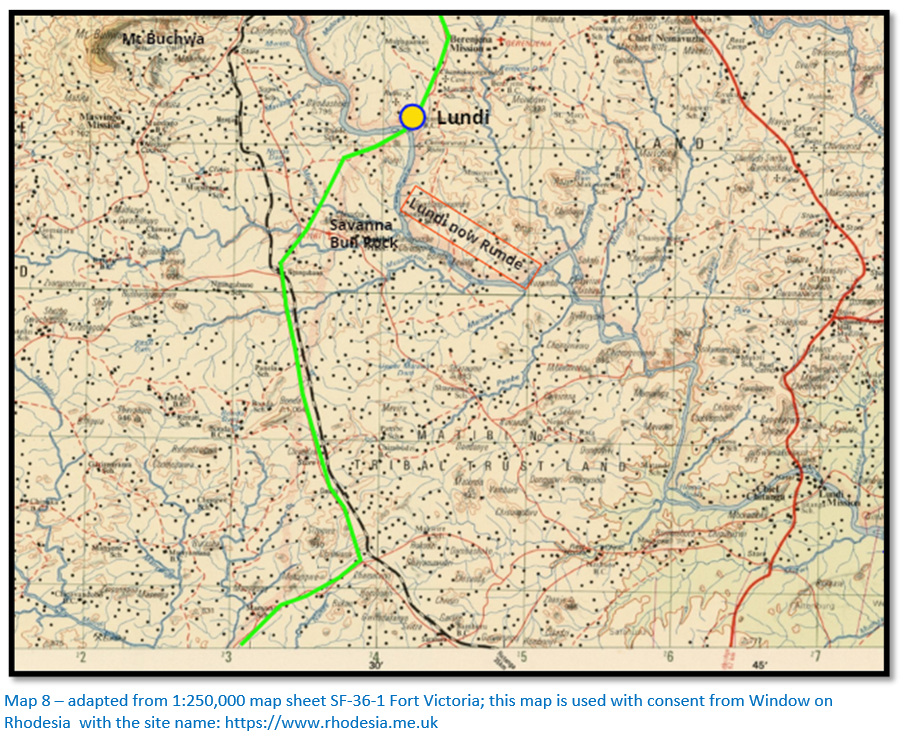

On 3 August Pennefather wrote from The Lundi, now Runde river stating it was his: “intention to make a fort on the east bank of the Lunde, and to leave a detachment of Police in occupation.”

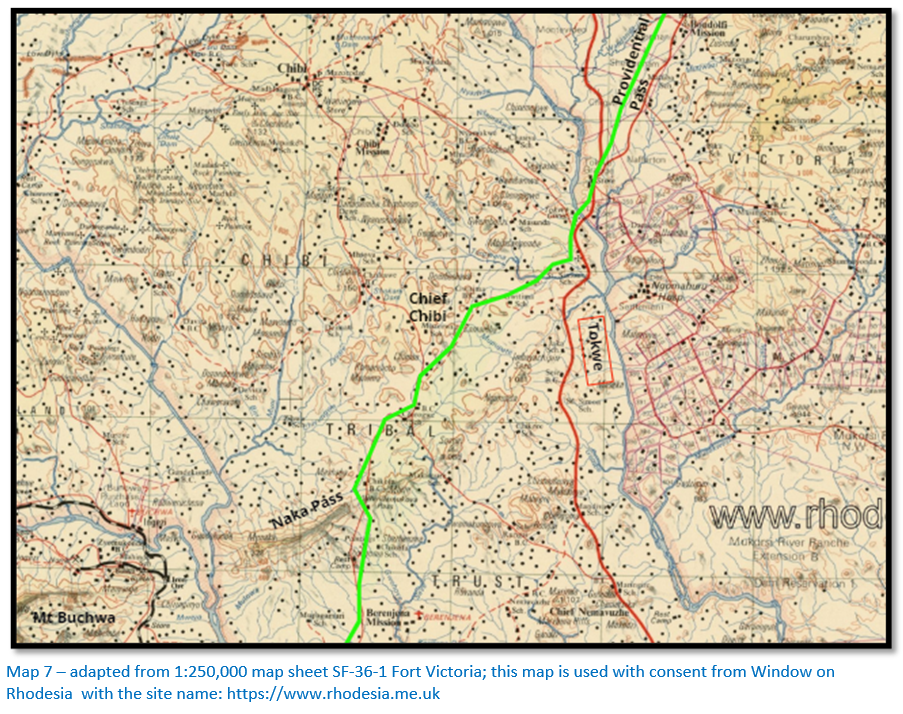

But shortly after Colenbrander had caught up with the Column from Bulawayo and provided Pennefather with the information that the amaNdebele intended military action against the Column, Pennefather wrote to Kimberley from the Naka Pass: “I cannot control this long line of road with five hundred men, if the Matabele are actively hostile. You must be prepared to abandon this road altogether, at any rate until next April. I do not know what we shall be able to do about keeping open postal communication. I am leaving post riders along the road, but if the Matabele interference takes the form of cutting our communications, they will, I fear, make short work of our isolated posts."[vi]

Appointment of the first Postmaster-General in 1890

On 11 August 1890 the Kimberley office of the BSACo advised London: “Mr Rhodes has appointed Captain C. H. Tye,[vii] late Senior Captain 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons as Chief Officer at Tuli, in charge of commissariat, transport and postal services.”

Tye’s job description included the task of the first Postmaster-General: "The postal service from Tuli northwards will be entirely in your hands: as we do not know the details Colonel Pennefather has arranged, precise instructions cannot be given you, but the wish of the Company is that there should be as far as possible rapid communication between Mr Colquhoun in Mashonaland and the base camp at Tuli, for transmission to Head Office in Kimberley.”

The mail service is functioning

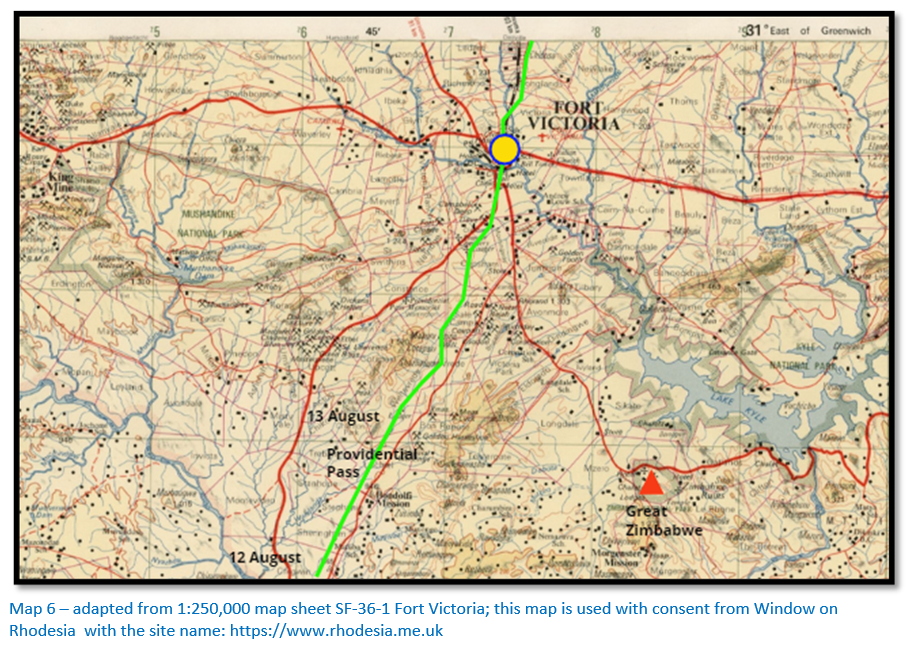

Henry Borrow, the Pioneer Column’s Adjutant, wrote to his mother soon after the Column reached Fort Victoria: “Another chance of writing you as there is a post leaving tomorrow. We have been very lucky so far and have been able to send a post almost weekly, but of course we do not get our posts in quite so often, still we cannot complain…”

On 23 August Colquhoun reported to Kimberley from "B.S.A. Co.'s Camp, Mashonaland, forty miles south of Mt. Wedza, altitude 4,300 feet. Postal arrangements organised and working admirably – letters arrived from Kimberley last two mails in eighteen and twenty days respectively…”

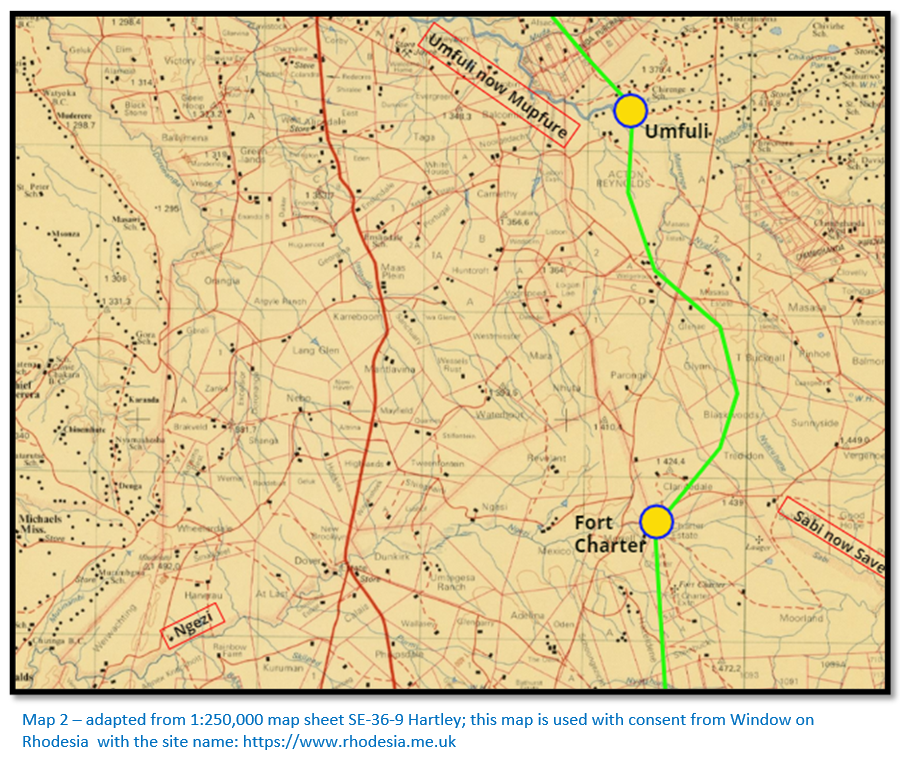

Pennefather reported to Kimberley on 4 September 1890 from a “Camp at Sabi and Umgesi [Ngezi] rivers [i.e., Fort Charter] A postal service has been established by means of post-riders, four of whom are stationed at about every thirty-five miles along the road. So far it has worked very well, our letters reaching us with great regularity. But I hear that many horses have died in the low country of horse sickness, and I hope that the service of carts drawn by running oxen will soon be established as far as Fort Victoria. Whether any service can be maintained in the wet season remains to be seen."

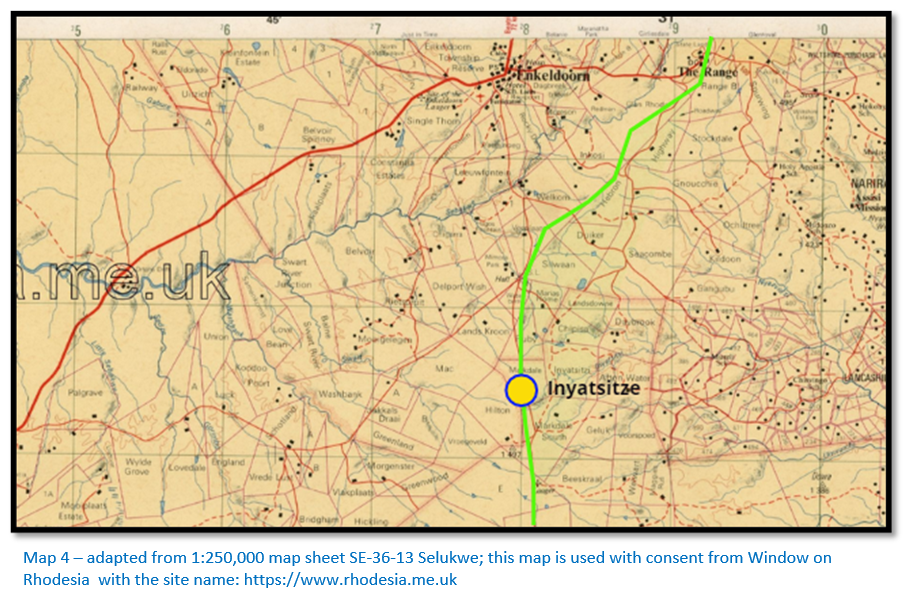

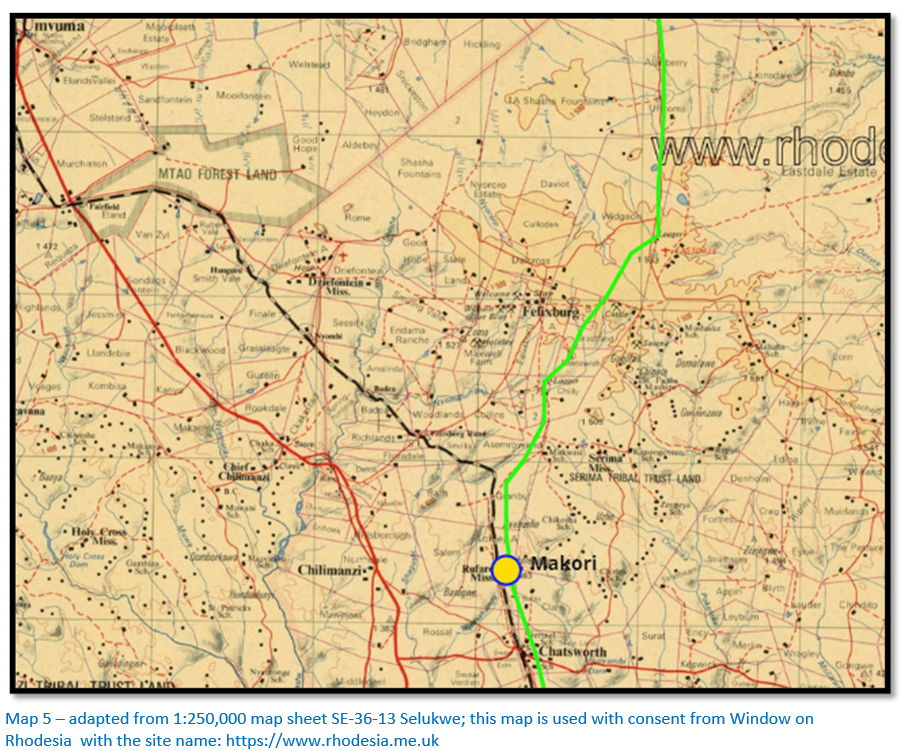

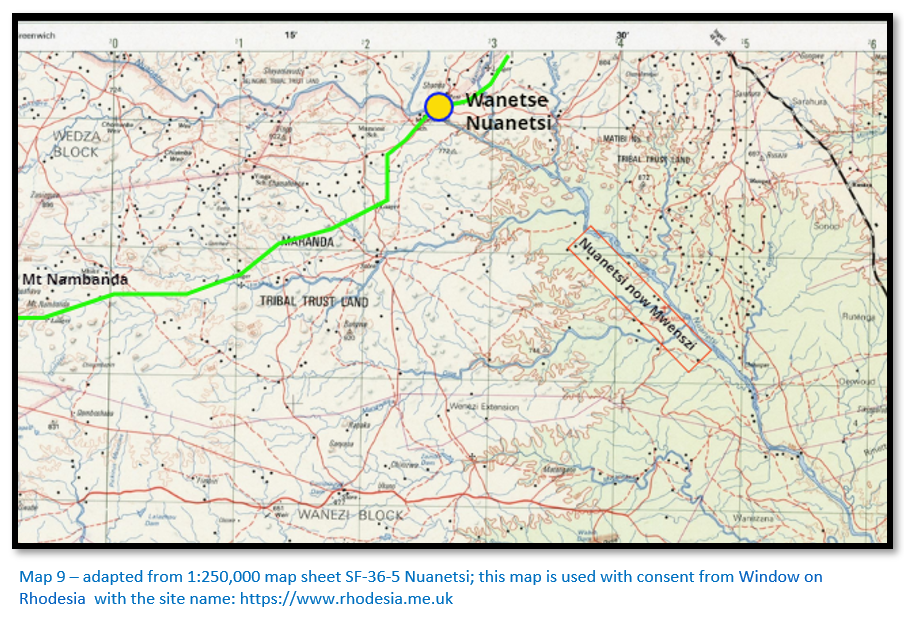

Smith lists further stations at Matibi’s and Wanetse (Nuanetsi) – Dave Collis thinks these were probably post stations at a later stage and that their establishment coincided with that of the telegraph line in 1891. When Victor Morier was at Lundi post station on 9 October 1890 the next station down the line was Setoutse’s, not Matibi’s or Wanetse.[viii] However, the distance between Setoutse’s and Lundi post stations looks too far to be accomplished by one despatch-rider and I have included Wanetse (Nuanetsi) on the maps below. The article below about the despatch-rider Thomas Llewellyn Thomas does however mention Matibi as a post station.

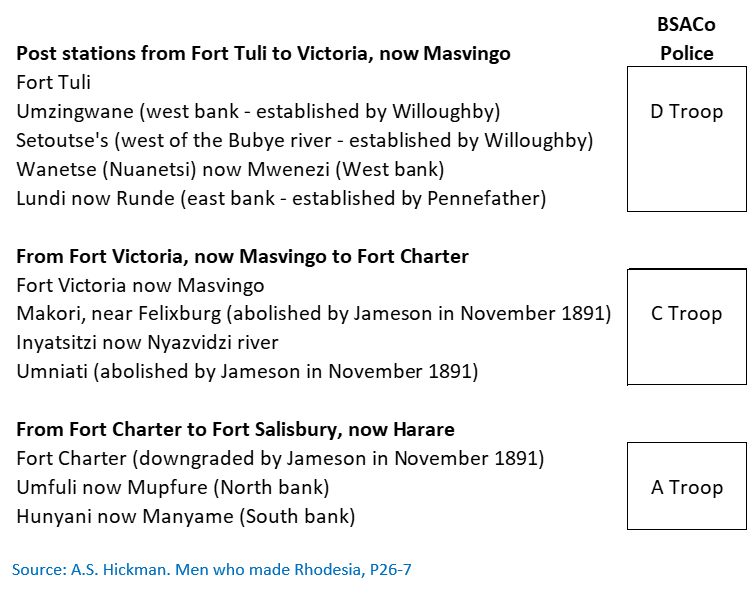

The headquarters stations of the various BSACo Police Troops were responsible for manning the post stations, but the situation in the early days was not static and the Troops had to be moved around as the situation required.

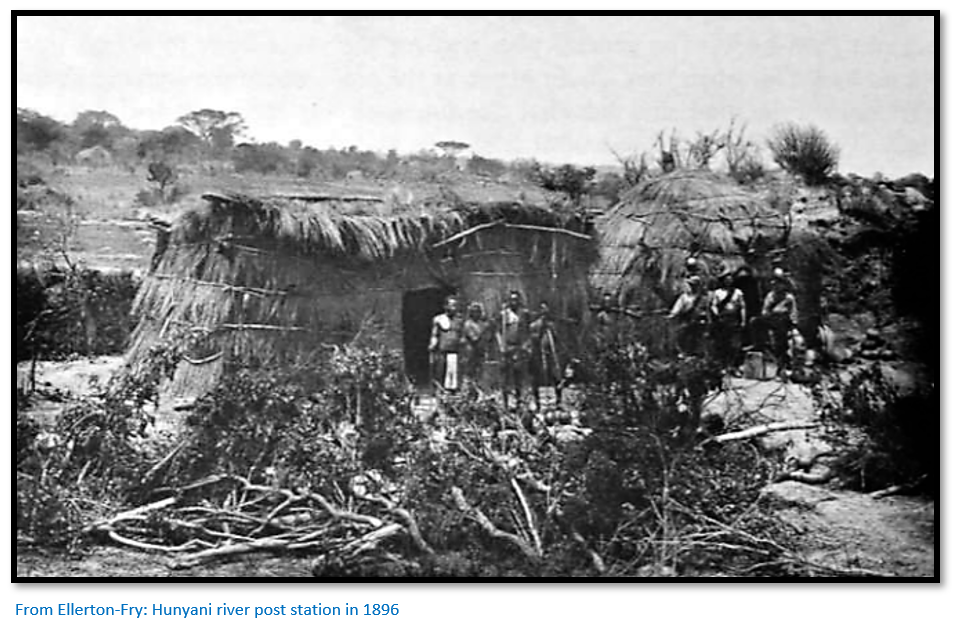

The post stations were established along the length of the route traversed by the Pioneer Column from Fort Tuli to Fort Salisbury and averaged between 48 – 64 kms (30 – 40 miles) apart. Many were sited on the banks of the bigger rivers that needed to be crossed and each manned by a small team from the BSACo Police Troops who used horses for transport.

By the time Fort Salisbury was reached, post stations had been established along the route of the Pioneer Column and on 13 September 1890, the day the Union flag was raised by Edward Tyndale-Biscoe, the first message was sent back along the line of march. Lieut-Col Edward Pennefather wrote a report to Rhodes notifying him that the Pioneer Column had reached its destination at the site of Cecil Square, Salisbury (now African Unity Square, Harare) and not the original intended destination of Mount Hampden.

Pennefather’s message left Fort Salisbury on Saturday 13 September and reached Macloutsie at 10:30 am on Thursday 18 September 1890. The distance of 790 kms (490 miles) being covered in five travelling days by despatch riders on horses travelling from one post station to the next.

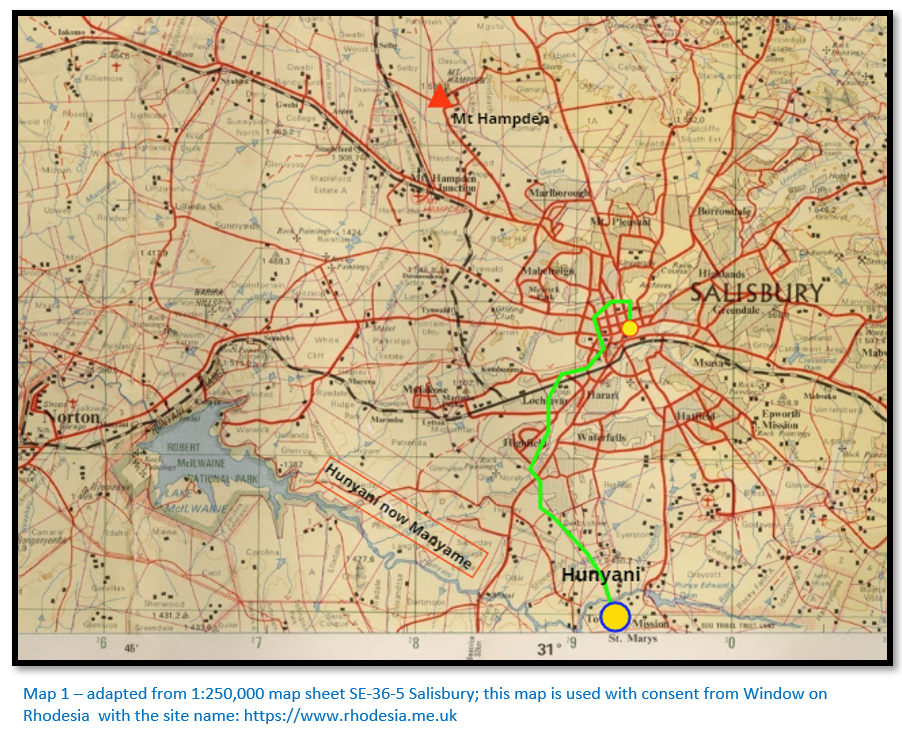

Difficulties of keeping the mail route open in the 1890-91 rainy season

On 17 September 1890 Pennefather wrote to Rutherfoord Harris at Kimberley: “I cannot think of any better means of getting the mails over the large rivers when in flood than by a long wire rope with a travelling cage on it. The wire ought to be strong enough to bear a man's weight and might be stretched tight by a windlass at either end. The Tuli is too broad and the banks too low for this plan, but I have told Turner to construct a flying bridge, anchored in the middle of the river-bed. The wire rope would answer on the Umzingwane, Wanetse, Lunde and Tokwe, also the Bubye and Umsawe. The Umzingwane would take about 400 yards of rope; the Wanetse about 200, Lunde 800, Tokwe, Bubye and Umsawe about 100 each. Several of these rivers I could put timber bridges over which would last a couple of years, if I had plenty of men and plenty of rope and chain. There are three rivers on the high veldt, the Umshagashe, the Umfuli and the Hunyani which may want bridging and I can manage all those."

On 30 September Pennefather’s hopes that a cart service would replace the existing system was expressed again: “I have written instructions for Captain Tye with regard to the postal service from Tuli and have informed you from time to time of the orders I have issued for the establishment of the mail service on a more economical footing than the present one, which entails a heavy sacrifice of horses. On account of the length of the line of communications and the possible delay of carts by the rivers in summer, a larger number of carts will be required than you seem to have contemplated. I do not think that the service can be effectually carried out with less than seven carts between Macloutsie and Mt Hampden.”

A week later on 6 October, Rutherfoord Harris advised London: “In view of the near approaching rainy season, three large ship’s boats each capable of containing about twenty-five men, or one entire wagon taken to pieces, left Kimberley this week for Tuli. They will, we hope, overcome the difficulty of connection during the rainy season.”

On 11 October Pennefather reported to Colquhoun: “I am endeavouring to substitute carts drawn by running oxen for the post-riders, in the low country, but owing to the non-arrival of the carts ordered long ago from Kimberley, I have still to keep the horses on the line.”

Early Troop movements

A Troop were soon withdrawn from Fort Charter to supply reinforcements to Captain P.W. Forbes in his dealings with Chief Mutasa and the Portuguese who were determined to resist any incursion by the BSACo into what they regarded as their territory in present-day Manicaland.

They were relieved by F Troop under Captain Lendy whose role now changed from artillery to despatch-riding. This did not last long, and they were soon sent back to Fort Salisbury, being relieved by D Troop from Fort Tuli. E Troop under Captain Leonard moved from Macloutsie to

Fort Tuli arriving on 15 December 1890 leaving the BBP to garrison Macloutsie.

D Troop’s journey to Fort Charter

On 16 December 1890 D Troop under Captain Chamley-Turner crossed the Shashe River, the rainy season that year was one of the heaviest on record. The Police were not adequately prepared for the weather which left the track a muddy quagmire along which the ox-wagons had

to be frequently dug out of the mud and the rivers came down in full flood. Hold-ups were frequent particularly at the rivers and the Lundi, now Runde river proved one of the toughest obstacles. Trooper No. 358 Corporal Divine describes how a complete span of oxen was nearly swept downstream. Eventually a raft was made to carry the stores and empty wagons and was pulled over by the entire Troop. Christmas Day was spent on the northern bank of the Lundi river where all the ox-wagons had to be repacked. The Tokwe river, a tributary of the Lundi, also proved a formidable obstacle, but fortunately the floods subsided for a short period and was quickly forded. Finally, D Troop reached Fort Victoria in a wretched state and needed a few days to recuperate and recover after what was described as “a nightmare of a trek.” Eighty of the one hundred men in D Troop were riding on the ox-wagons when it reached Fort Victoria and sick with either malaria or dysentery.

Living conditions of the Despatch-riders

Often their rations at the small post stations became exhausted and they were reduced to eating mealie-meal and pumpkins, if they could barter them with local tribespeople, their uniforms were in tatters and their horses were so poorly they were unfit to ride. The rivers had often to be swum with the mail and despatches despite being swollen in flood and crocodile infested. Yet wherever possible, the despatches got through despite the obstacles.

Smith writes: “a heavy burden fell upon the dispatch-riders, who had to maintain communications under the most adverse conditions imaginable. Apart from the weather, they are often reduced to extremely meagre rations and they went in rags and some were barefoot. They also suffered heavily from malaria, dysentery, and undernourishment. Their horses were often unfit for service and many succumbed to the dreaded horse sickness. Yet in spite of all this misery, these men saw that the mails got through where it was humanly possible.”[ix]

Two despatch-riders were attacked by crocodiles at the Lundi river. One man died, the other had his leg frightfully wounded. There was no doctor, so a colleague tried to amputate the leg with a carpenter’s saw and he also died. The Tokwe river was also notorious for crocodile attacks and several telegraph linesmen and transport-riders were attacked here.

In a letter dated 9 October 1890 from Lundi post station Victor Morier wrote: "I have passed two post stations on my way up here where the men were absolutely barefoot, and not a boot to be got, though there are thousands somewhere. I am riding bare-behinded, the seats of both my regulation breeches being through, and no stuff, needles or thread to mend.”

Then followed on 18 October a letter from Fort Victoria: “I trust that you got my letter from Lundi River, though I feel doubtful about all these letters - the post is awfully erratic and irregular. There is a soi-disant [so-called] post system, i.e., there are post stations at intervals of fifty miles along the road from Tuli to Mount Hampden, at which four to six men are stationed as post-riders. The horse sickness, however, plays the d---l with the weekly mail; the horses die suddenly half-way, and the men have to walk twenty or thirty miles, carrying the bags or abandoning them, according to their various constitutions. All this could be easily avoided, but there is mis-management in many of these things. The Pioneers, who did hardly any mounted duty, and were disbanded after seven months, were provided with valuable salted horses, as much as $95 being paid for a horse. Fifty of these horses along the road would avoid all this delay and misery to the men who have to ride the post and save the Company enormous expense as new sets of horses have to be found for the stations every fortnight almost.”[x]

The death rate was extremely high for Despatch-riders

The heavy rains in 1890-91 brought sickness to many of the Troopers at the post-stations where they often lay unattended until death took them away. Quinine was used as a remedy, but the real cause of malaria, the female Anopheles mosquito, was unknown and it was popularly thought that unhealthy vapours from low-lying ground was the cause of the disease.

A Despatch-rider’s encounter with a lion

Smith tells the story about one of the despatch riders named Thomas Llewellyn Thomas which illustrates the conditions under which they operated. The mail dispatched from Salisbury on 18 December 1890 was carried by Thomas from the relay station at Matibi’s onto Fort Tuli. It was a dark, rainy night when he set out, riding one horse and leading a second which carried the mailbag on its pack saddle. Riding alone through the wilderness at night was grim enough, but the wet conditions added to the discomfort of the ride and in the shadows lurked all kinds of real and imaginary dangers. Suddenly the horses snorted, plunged and broke into a gallop. The grunt of a lion in the bushes revealed the cause of the horses’ fear.

Thomas drove the horses hard, but the darkness and slippery trail impeded their progress. The lion charged after them and with a roar, it sprang and seized Thomas's mount on either side, digging its claws deep into both quarters. Thomas was thrown to the ground, but the pace of the horse tore the lion’s claws like knives through its’ skin and flesh. The two horses rushed madly into the darkness down the trail with the lion in full pursuit.

Thomas ran to the nearest tree and scrambled to the top, and before long, the lion having abandoned the chase, came back. Scenting Thomas in the tree, it walked up and down at the foot of the tree. For the rest of the night, the animal remained there, sometimes lying down, sometimes walking restlessly around the tree. With only a revolver, Thomas could do nothing. He was perched in a mopane tree and feared that if he attempted a shot and only wounded the lion, the infuriated animal would be goaded into the discovery that it need only spring up in order to claw him down.

With the coming of daylight, a wagon came down the trail and the lion made off into the bush. Thomas walked back to Matibi’s and the horses ran onto the next staging post where the wounded animal recovered. The post bag however, was only found about four months later in a soggy condition with the contents ruined.[xi]

The high cost of replacing horses

The loss of horses was extremely high. At Macloutsie and Fort Tuli Captain Leonard in command of E Troop estimated that ninety-seven percent of the BSACo Police horses died of horse-sickness, known as “dikkop.” There was no known remedy for the disease and hundreds of horses died. “Salted” horses (i.e., those who had horse-sickness and recovered) were few and far between and were said to lack their former stamina.

The 1890-91 rainy season brought the mail service to a halt

As Collis writes in his article – things just got worse. On 25 January 1891 Kimberley received two telegrams:

From Pennefather at Fort Tuli - who was proceeding on leave: "No communication with up country for past fortnight, it is most probable that no vehicles can go up or come down for next two months at soonest hope to re-establish postal communications when boats and wire arrive but cannot be done quickly you must not expect any wagons leaving Tuli now to reach Victoria before end of March."

The other from Captain Tye: "Two boats complete arrived Monday have them in the river here have sent to Macloutsie for rope and hawsers have got a man who understands work of that sort will send him up with the boats certainly in a week."

Henry Borrow in a letter written at Hartley Hill on 12 February to his mother wrote: “We have had no communication from the outside world for the last six weeks and as far as I can see there is no probability of the post being able to get through by the road for the next two months, if then. The Lundi River where the down posts are stuck is about a half mile of rushing water going like a mill race - the up posts are all on the Nuanetsi River.”

In the same letter Henry Borrow describes a successful attempt to send their letters via Bulawayo for which he and his partners earned a strong rebuke from the acting Administrator Colquhoun, although he was later forced to use this route himself for some official dispatches. On 27 February Colquhoun sent George Burnett[xii] down-country armed with the following note: “To Heads of Prospecting Parties, etc. The bearer, Mr Geo. Burnett, is proceeding down country to endeavour to open up communications. I will be glad if you will assist him in any way in your power. Anything requisitioned for by Mr Burnett will be paid for or returned by the Company.”

The rains gradually eased by the end of March and as the flooded rivers subsided allowed the backlog of mails and transport to get on the move again. The Cape Town office of the BSACo received the following telegram from Colquhoun on 24 April 1891: "Mails of 26th December to 16th January received yesterday communications across rivers re-opened.”

Introduction of a bullock cart service in 1891

In February 1891 Lieut-Col Pennefather, noting the plight of men and horses, issued an order that that the mail and despatches were to be carried by scotch cart and oxen. However, this slowed down the whole system and it was not long before Dr Rutherfoord Harris, the BSACo’s Cape Secretary issued a new order that special despatches should be carried by the old method of horse and rider.

However, Borrow wrote on 6 May from Fort Salisbury: “…and yet the old post meanders along as best it may. It starts from Tuli to Victoria two hundred miles - with two men to ride the whole distance on the same horses. Then it comes on by bullock cart and after that, it is brought on by donkeys, but as the donkeys belong to one of the prospectors and are likely to be required any day, the fate of the post is precarious.”

The 1891 dry season

The end of the rains saw a renewed effort to bring the postal route up to scratch. Captain Nesbitt[xiii] of the BSACo Police was appointed as Senior Commissarial Officer with responsibility for the Salisbury end of the mail system and from mid-1891 the post carts were organised north of Victoria, although the lowveld country was still left to the BSACo despatch-riders.

On 12 August the Cape Town office advised London that mails for Fort Salisbury left Tuli weekly on Thursdays and were twenty-two days in transit and that the despatch of mails from Fort Salisbury depended on the arrival of the up mail from Tuli.

A typical upset

In September 1891, Senior Commissariat Officer Captain Tye was asked to reply to Robert Morier’s father who alleged that letters from his son had been tampered with: “It must be borne in mind that letters are sent from Salisbury in a cart a distance of 400 miles to Tuli and necessarily get a good shaking up. Previous to the mail carts being established letters were brought by despatch riders on horseback and on one occasion the rider was attacked by a lion and the mail bag was lost. It was afterwards found by the Honourable Erskine's party and sent to me. On being opened nearly all the envelopes had been eaten by ants and the letters were in a very dilapidated condition. I ordered those where the addresses could be made out to be put into fresh envelopes and redirected and eighty such were so done. The remainder had to be sent back to Fort Salisbury. On other occasions, which happens nearly every week, when letters reach here with the edges frayed, they are pasted up and put in fresh envelopes.”

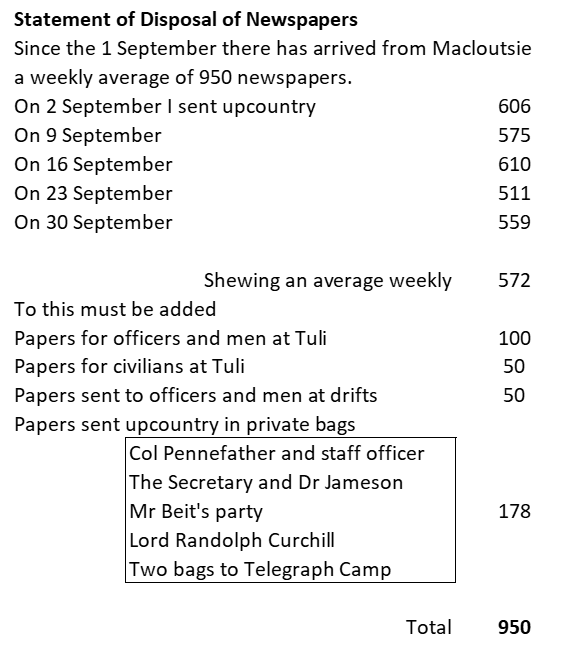

The amount of mail being moved can be judged from a report made by the W.J. Angus, the Postmaster Tuli to Captain Tye on 30 September 1891.

The telegraph advances

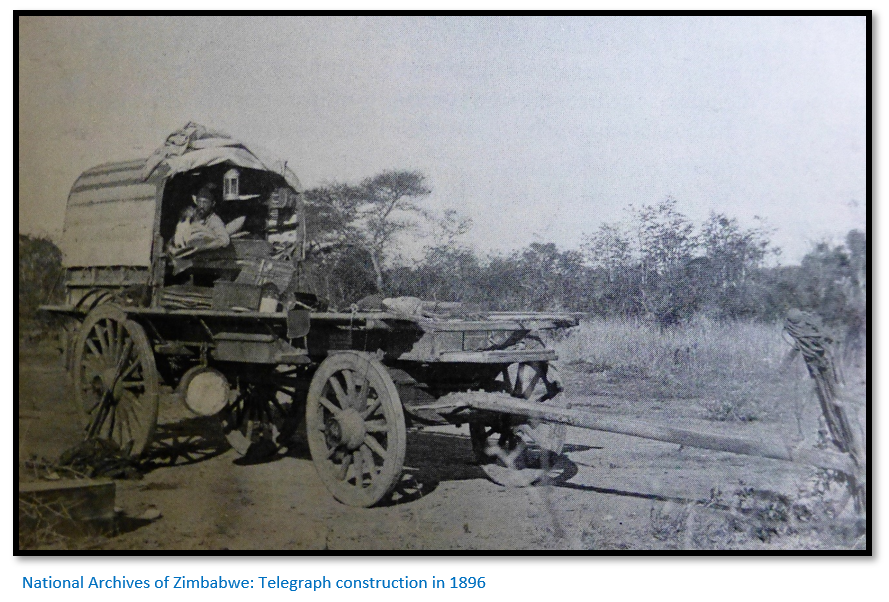

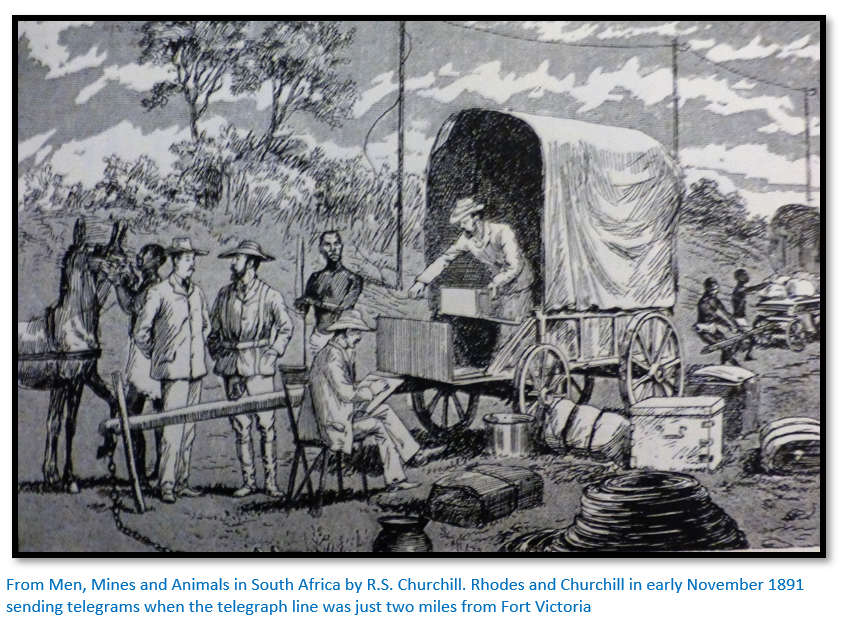

The telegraph line was advancing and a Tuli office was opened on 28 May 1891.[xiv] The BSACo saw the telegraph line as the solution to their communication problems. On 16 June the Cape Town office advised London: "The extension to Fort Victoria when completed will enable Dr Jameson to reduce considerably the very heavy expenditure now incurred in despatch riding.”

On 10 July the same office advised Dr Jameson, now in Mashonaland: “Mr Rhodes as you know does not care much for letters and he says that the men's letters can come by oxen wagon just as well as killing horses in carrying them. You will have a telegraph to Victoria in October, and this is all that is necessary. The fewer letters written on petty details the better and gold and other news of importance can be telegraphed.”

By December 1891 the telegraph line had progressed north of Fort Victoria 1,014 kms (630 miles) from Mafeking and on 16 February it reached Salisbury. The line construction cost was £92,803.

Dr Jameson makes changes to the mail system in late 1891

Although A.R. Colquhoun was the BSACo Administrator from October 1890 to September 1894, it was Dr Jameson who was Chief Magistrate from September 1891, who wielded the real power.

As Hugh Marshall Hole, Dr Jameson’s private secretary, explains in Old Rhodesian Days in October 1891 Rhodes made his first visit to the country. He particularly wanted to discuss finance with Jameson. The BSACo’s funds were running low with hardly any income be generated and the biggest cost being that of the BSACo police force which was running at £150,000 per annum. Rhodes and Jameson put their heads together to discuss a means of getting rid of this white elephant.[xv] They pooh-poohed the idea that the settlers, who were familiar with firearms and mostly in their mid-twenties, needed a permanent body of six hundred Police to protect them.

The Mashona were not thought of as any kind of threat – at least until the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga of 1896 and the amaNdebele in the first year after the occupation of Mashonaland had shown no obvious signs of hostility.

Jameson thought the constant drills and training continued by the BSACo Police were a mere show and could not understand why the force would not carry out civil duties, such as driving post-carts, assisting with surveying the farms, or carrying clerical work in the administrative offices. Marshall Hole heard him saying to Lt-Col Pennefather, the commanding officer: “When your men are doing nothing, you show them in your returns as ‘available for duty!’ But the moment I ask for a man to do something, I am told that he must get extra duty pay.”

The solution was to raise the Mashonaland Horse – volunteers from Salisbury and Victoria were recruited and once a week required to bring their horse for an inspection parade. In a year Jameson managed to reduce the Police force from six hundred and fifty members to one hundred and fifty of all ranks.

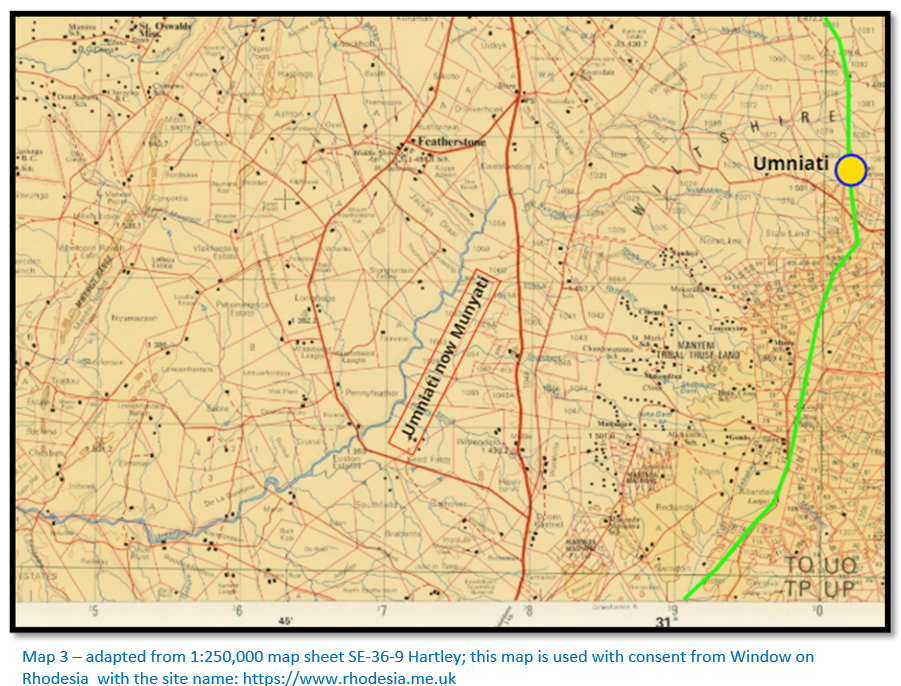

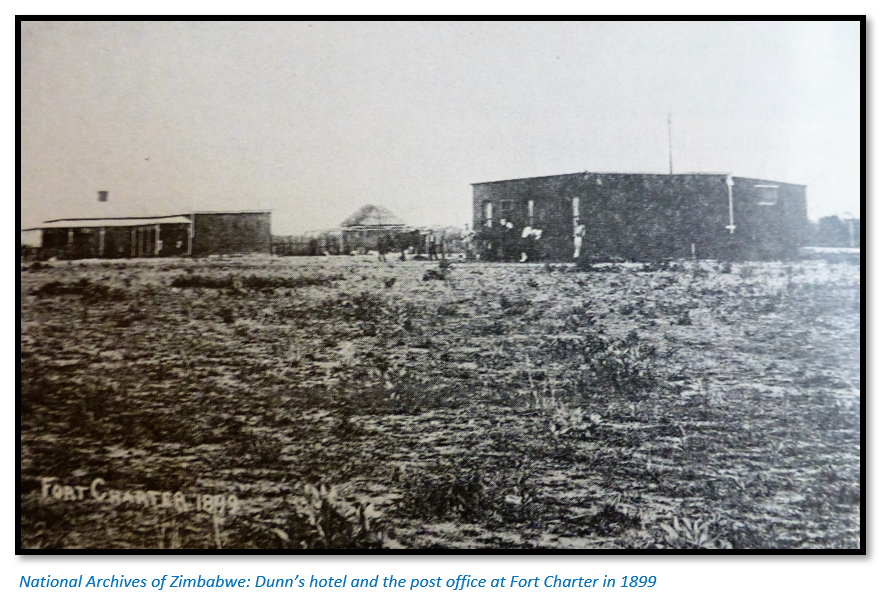

In 1891 changes were made to the post-stations and Jameson "abolished" those at Makori and Umniati and downgraded Charter to a two man post with a Sergeant, or NCO in charge.

This was followed up by a letter to Captain Nesbitt on 22 November 1891: "Dr Jameson directs me to inform you that he has found that the mail cart proceeding from Salisbury to Tuli often arrives at Charter three days before the up cart arrives. These three days are so much time wasted to people in Salisbury who might as well post their letters three days later. Instead of changing the date for the departure of the mails from Salisbury, Dr Jameson suggests that the cart should go straight through from Salisbury to Victoria, and no longer stop at Charter.

The cart from Salisbury down would then wait at Victoria till the arrival of the up cart when they would exchange loads and return, the one to Salisbury, the other to Tuli.”

Rhodes then makes further changes, but in reality, the changes are superficial

More important changes came a month later on 21 December 1891 when Rhodes telegraphed Jameson: “…as to Police Officers and whole Administration north of Nuanetsi…the military regime is to be superseded by a civil administration… I will deal with Tuli and Nuanetsi from here including the post by oxen as far as Victoria.”

The BSACo Police acting as despatch riders received their discharges, but in many cases stayed on as trading agents for the BSACo, or as store or hotel-keepers in their own right with an honorarium for looking after the Company’s post oxen. The transport-drivers and leaders of the ox-wagon teams on the road lost their Police titles and were paid through the books of the civil administration.

Thus, the estimates of expenditure for the new Post Office Department for the year 1892 included:

7 conductors on Tuli line at 5/- per day £630

7 leaders on the Tuli line at £2 per month £178

The only postmaster was that of Victoria at £100 per year; the postmaster at Fort Tuli was paid from the Cape Town office.

Dr Jameson makes changes to the route in 1892

In order to avoid the difficulties of crossing the drifts over the Umfuli, now Mupfure and Hunyani, now Manyame rivers during the rainy season, Jameson re-routed the post carts along the new road built by Sergeant-Major Lyons-Montgomery,[xvi] from Marandellas’ kraal to Charter, now known as the Watershed Road, which turns south towards Charter just before the present main road to Umtali, now Mutare enters the town of Marandellas, now Marondera.

In 1892 the post carts left from Manica Road in Salisbury and went east as far as Marandellas’ before turning off for Charter and Fort Victoria. A public notice appeared in the Mashonaland Herald and Zambesian Times of 9 January 1892:

POSTAL NOTICE

For the future the mail for Tuli will leave Salisbury on Mondays (by the new road via Marandella's Kraal) closing at 11.30 am - registered letters at 10 a.m.

By Order A.M. Morkel

9.1.1892 Postmaster

A letter was sent by Marshall-Hole at the BSACo office dated 11 January 1892 to Captain Chaplin, the postmaster at Fort Victoria: "Dr Jameson directs me to inform you that the post-cart this week is going down by Montgomery’s new road via Marandella's: as this road is forty miles longer the post is leaving Salisbury two days earlier. The Salisbury post-cart will in future go right through to Victoria and then return with the Tuli mail.”

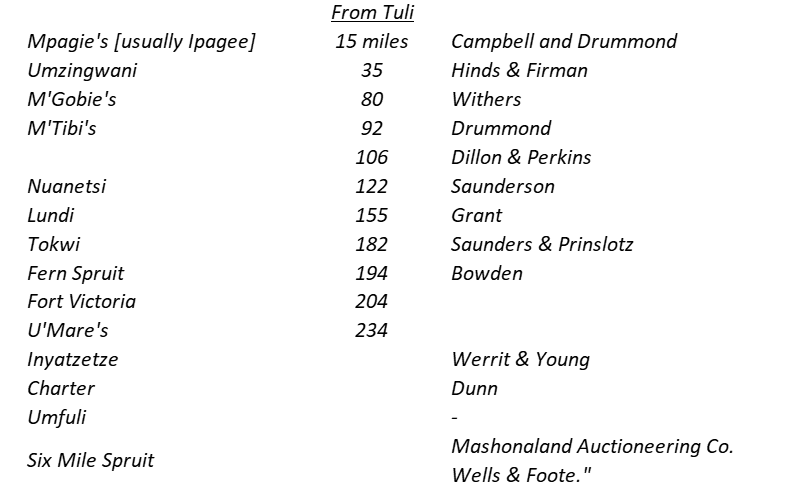

Main Tuli – Salisbury Hotels

Primitive hotels and stores were springing-up along the route and on 2 April 1892 the Herald carried an announcement:

"MAIN ROAD HOSTELRIES

The following is a list of wayside hotels which have been or are being instituted. The advantage to persons travelling to and from this country thus afforded is evident. We hope all the enterprising proprietors will do well.

These commercial arrangements between the BSACo and individual "hoteliers" were quite common and are illustrated by a letter from AHF Duncan, then Surveyor-General to the Accountant dated 31 May 1892:

“Mr David John Thomas will take out a Wayside Licence at the Post Station about five miles this side of the Umfuli River; Mr Thomas will pay ten pounds cash and the Company will pay him £2.10.0 per month for a period of six months from 1 June 1892 - £15, leaving a balance of £12.10.0 for which sum he will sign a promissory note…The £15 to be debited to the Postal Department.”

See the article: A description of the old Meikles Hotel, the Mill and Coach House and Coaching Stables and Strickland’s Store on Marshbrook Farm (now Charter Estates) in Charter District under Midlands Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

A mail cart traveller’s memoirs of a 17 day journey from Tuli to Salisbury in 1892

D.G. Gisborne wrote an account of his journey: "On reaching Tuli we changed to what was known as a travelling wagon - a four-wheeled covered conveyance on springs - which had once provided a very comfortable way of travelling on the rough Pioneer road which lay ahead of us, but was then, as we knew it, only fit for the scrap heap. However, drawn by eight oxen - not in the best condition - Her Majesty's Mail with four passengers, started off on the long journey to Salisbury in June 1892.”

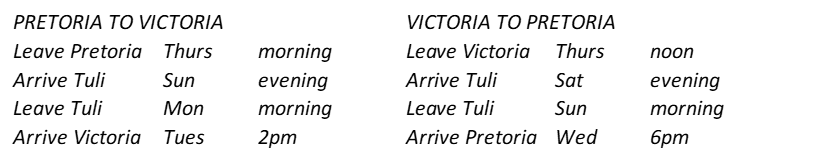

Gisborne goes on to record stops at "canteens" at the Ipagee and Umzingwane Rivers, at the Gondokwe River, at Fern Spruit and at Charter. The journey time between Tuli and Salisbury was seventeen days as per the following timetable:

In view of the very slow journey involved the public were no doubt pleased to read in the Herald of 18 June 1892: "A pressing want of Mashonaland now is a fast postal and passenger service from Tuli. Several parties have been or are negotiating with the Chartered Company in the matter. It is to be earnestly hoped that out of it all something practical will emerge.”

In the Herald of 6 August: "Mr Duncan, the Surveyor-General, must be congratulated upon the new postal tariff and upon the arrangement with Mr Bezuidenhout whereby, in a few weeks, the mails are to run ‘twixt here and Tuli in twelve days. There are few things more important - and less obtrusively so - for a young country than a quick postal service between it and more civilised centres.”

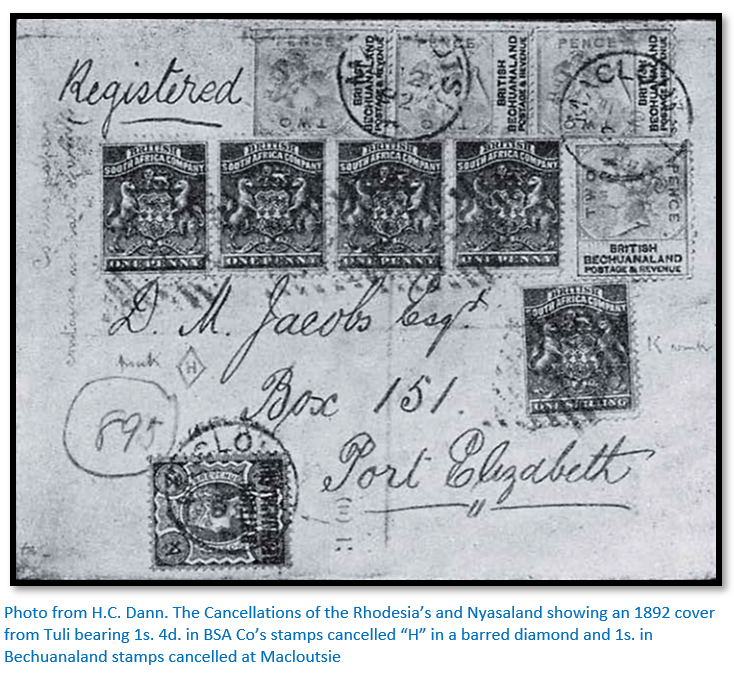

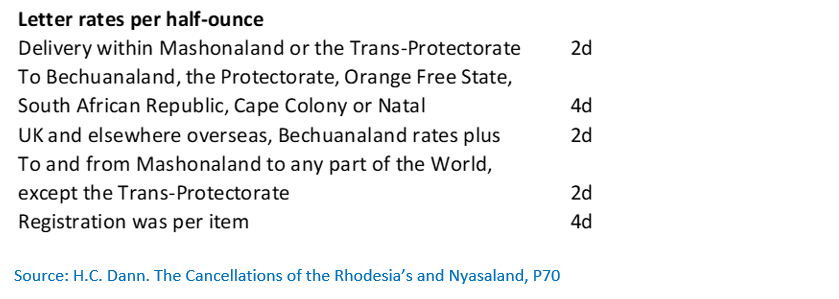

Postage stamps

Initially stamps from the Bechuanaland Protectorate were used, but by 1 August 1892 an agreement was reached between the British South Africa Company, the British Bechuanaland government and the Cape Colony in which BSACo postage stamps were accepted.

A new private mail service contract run by Bezuidenhout in late 1892

On 8 August 1892, the Acting Secretary, Salisbury advised the Cape Town office:

"Enclosed I beg to hand you a copy of the Postal Contract entered into on the 8th instant with Mr H. Bezuidenhout, the terms of which have already been telegraphed by Mr Duncan to Mr Rhodes.

This contract will entail an increased expenditure on postal service without a relative increase in revenue, but Dr Jameson considered that such an arrangement was absolutely necessary, as, were we to go on as we have been doing lately, we should within a few months find ourselves with no postal plant left - either oxen or carts - and a still larger expenditure than the present contract entails would then have to be incurred, otherwise our post and passenger service would have to be stopped altogether.

You will see by the terms of the contract that there will be a monthly cash expenditure of £175 and that the balance of the £4,500 has to be paid at the expiration of the contract. This balance, Dr Jameson thinks, will probably be fairly well covered by the plant taken over and the rations issued, so that at the end of the twelve months there will be practically no balance to pay to the contractors.

Bezuidenhout has the reputation of being the best transport rider on the road. He does not appear to be a very sharp businessman, but Dr Jameson feels sure that his agents, of whom he believes Mr EE Homan is one, will be able to supply any deficiencies in that respect. Bezuidenhout has a large stock of good cattle and promises very shortly to put on more comfortable carts or even coaches.”[xvii]

But the new mail service was not a success

Bezuidenhout, probably the lowest tenderer, was not a good choice. He was neither a "sharp businessman" nor an efficient transport contractor and the BSACo Company regretted employing him. The actual 12 month contract was signed and was to commence on 8 August 1892 with Bezuidenhout given until 19 September to get the journey time down to the promised twelve days, but the twelve day timetable had to be delayed until 17 October and a few days later, on 29 October, Bezuidenhout placed his first advertisement in the Rhodesia Herald:

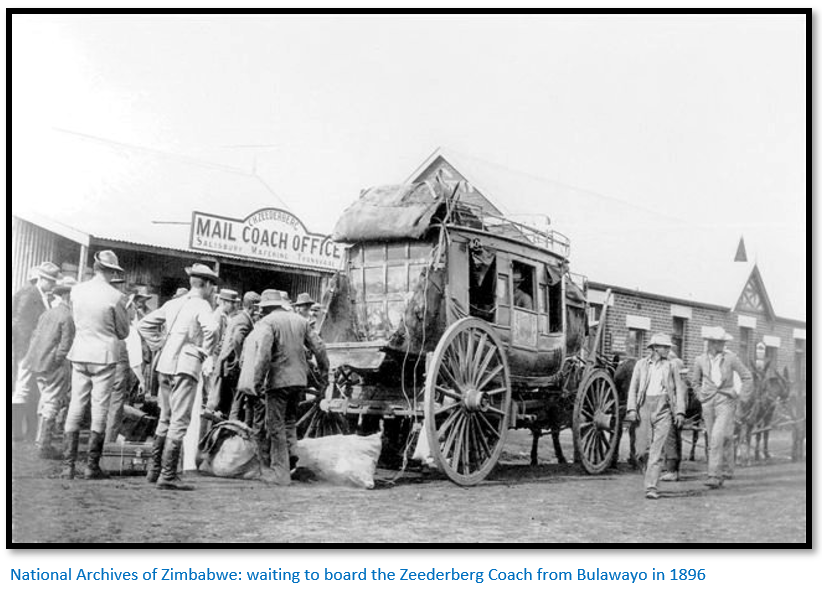

"THE CHEAPEST AND QUICKEST ROUTE TO AND FROM MASHONALAND THROUGH PASSAGE IN EIGHTEEN DAYS - AT REASONABLE FARES. H. BEZUIDENHOUT'S ROYAL MAIL CARTS BETWEEN TULI AND SALISBURY IN TWELVE DAYS EACH WAY, RUNNING IN CONJUNCTION WITH ZEEDERBERG BROS. MAIL COACHES FROM PRETORIA TO TULI. GOOD HOTEL ACCOMODATION AT SHORT DISTANCES EXISTS NOW ALONG THE ENTIRE ROAD. FOR FURTHER PARTICULARS APPLY TO: E. E. HOMAN, SALISBURY & TULI"

With the onset of the rainy season on 3 December 1892 the Rhodesia Herald reported:

"Mr Bezuidenhout is once more back from an inspection of his post-cart stations. It is intended we understand to run a basket over the wires spanning the larger rivers, for passing on the mail at high flood.”

There is little news of either the service or the contractor until the end of the rainy season; the absence of press comment indicates that Bezuidenhout must have kept the mail service going fairly efficiently during the rains. However, in April there was a new arrangement with Hollins and Zeederberg taking over the section as far north as Victoria; Bezuidenhout to keep the Victoria to Salisbury section until August 1893 when this would be taken over by Zeederberg and Bezuidenhout would receive the Salisbury to Umtali section as compensation. Within a short period, the "The Eastern Route" to Umtali was relinquished by Bezuidenhout to Symington.

Bezuidenhout was awarded the Salisbury-Bulawayo mail run in 1894, but the mail service soon came under heavy criticism.

Zeederberg and Hollins are awarded the mail service contract in 1893

In June 1893 the bullock cart service was succeeded by the Zeederberg mule coach service.

The following appeared in the Rhodesia Herald of 8 April 1893: "THE FAST SOUTHERN ROUTE

Messrs Zeederberg and Hollins have signed the contracts, and the first fast coach will leave Pretoria on the 15 May. The contract time to Victoria is six and a half days, and Mr Bezuidenhout will keep the section of the road from Victoria to Salisbury in his own hands until the 1 August. After that date he will take over the Salisbury-Umtali coaches, which will be run by mules, while those animals will then be employed from Salisbury through to Pretoria. This immense advance in Rhodesian means of communication is indeed a sign of the times.”

The start of the “first fast coach” was later changed to 15 June and on 13 May 1893 the following advertisement appeared in the Rhodesia Herald: "ZEEDERBERG'S POSTAL CONTRACT TENDERS

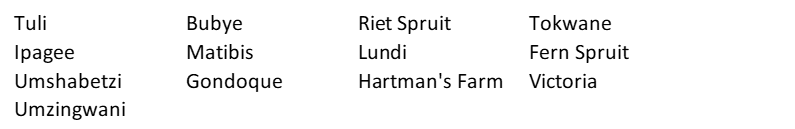

Tenders for a period of twelve months, commencing on the 15 June I893, will be received by the undersigned for the supply or delivery of TEN BAGS or less of MEALIES monthly, at each of the following stations between Tuli and Victoria:

Tenders to be sent in not later than the 30 May 1893 addressed and marked "Tender" to E. E. HOMAN, TULI.

N.B. Tenders can be sent in either for the supply of one or more stations.”

The Mashonaland Times and Mining Chronicle of Fort Victoria on 17 June announced that Weir and Co of Victoria were the successful tenderers for the entire contract.

This same newspaper ran two advertisements:

THE CHEAPEST AND QUICKEST ROUTE TO AND FROM MASHONALAND

HOLLINS AND ZEEDERBERG'S: MAIL COACHES

TIMETABLE

“IMPORTANT NOTICE: MESSRS HOLLINS AND ZEEDERBERG beg to announce that the first of their fast mail coaches from Victoria to Salisbury will leave Victoria on Thursday 8 August doing the journey to Salisbury in nine days from Johannesburg. On and after the 8 August these coaches will leave Victoria weekly on Thursday morning, and arrive at Salisbury on Saturday morning. Return Journey - leave Salisbury Monday noon and arrive at Victoria on Wednesday.

E.E. HOMAN, Agent”

Dave Collis found a copy of the contract for the Victoria to Salisbury section at the National Archives of Zimbabwe. It is signed by Dr Jameson on behalf of the BSACo and by the three contracting partners - Richard Roger Hollins, Christian Hendrik Zeederberg and Hans Jacobus Zeederberg. It began on 8 August 1893 and was for five years at a subsidy of £2,500 per annum. The weekly service between Victoria to Salisbury took forty-eight hours, considerably faster than the five days that Bezuidenhout’s service had been taking.

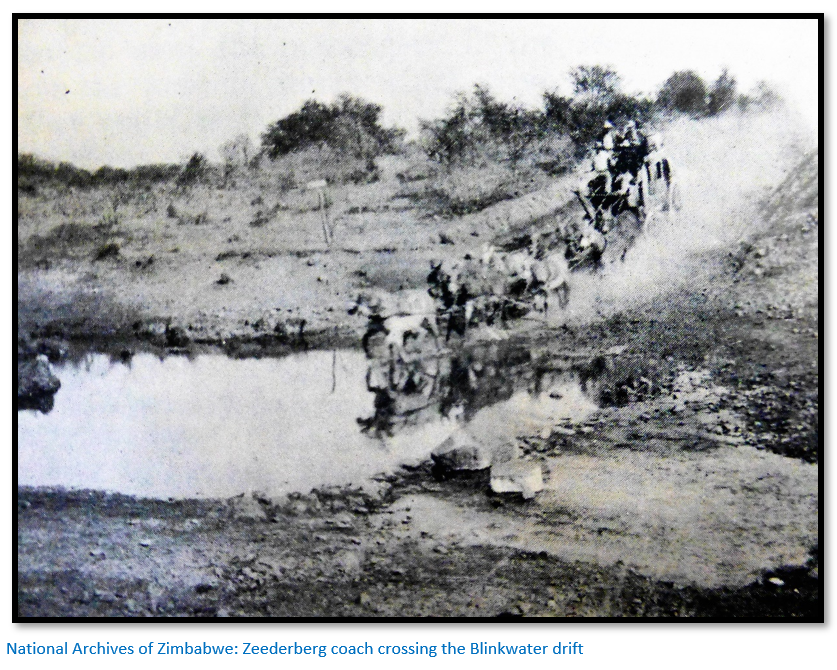

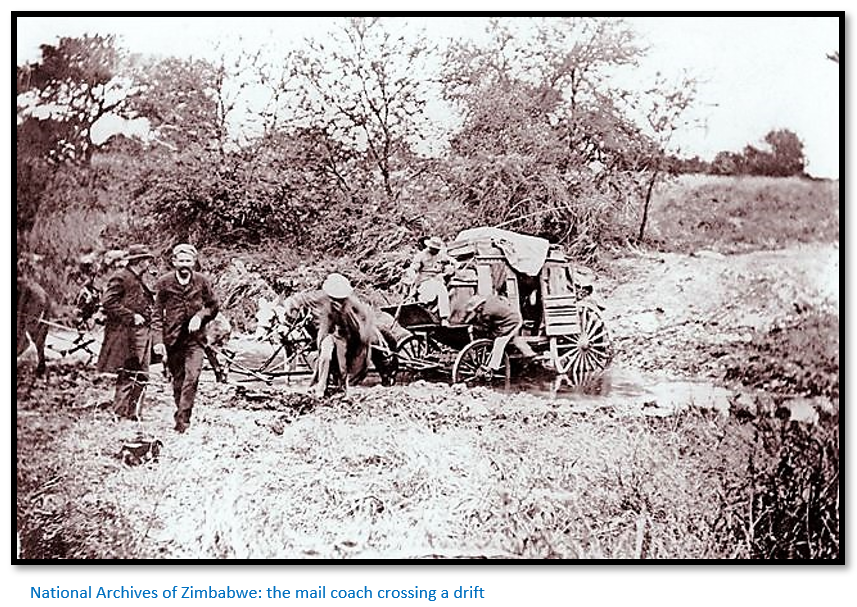

Mules were more hardy than horses and were not subject to horse-sickness or “dikkop.” Zebras were even tried as an experiment by Zeederberg but were not a success. Swollen rivers remained the main cause of delays as there were no bridges and all river crossings were through causeways or drifts.

For a full description see the article The Zeederberg Coach Company and the first passenger services into the country under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The amaNdebele begin to threaten the mail service in 1893

The Victoria newspaper of 22 July 1893 ran a report by Mr Eva, Hollins and Zeederberg’s manager: "MR EVA'S ROAD REPORT FROM TULI. On my arrival at M’Tibi's on Tuesday last, I found all the transport riders in "laager" and they informed me that fifty-two Matabeles had been there the day before, on which I suggested a wire being sent to Tuli. The wire came back that the Matabeles were on the Shashi also.

I then came on to my first station from there and found that the Matabeles had taken all my boys' clothing and food and one of the Matabeles put an assegai against the Colonial boy's breast and threatened to kill him: that night they returned, but the boys went to the hills for protection.

On arrival at the second station, I found all the cattle and boys gone. I was told that the Matabeles had taken the cattle, all my boys were threatened, and I cannot now get native labour to look after my stations and even the old Colonial boys will not work for me now on the line.

Manager for the Coach Company.”

The Salisbury newspaper of 5 August indicated that the Matabele were busy on the northern section of the line also: “…for on Saturday they slaughtered the Makalaka servants at the Range, the halfway post station to Salisbury…”

Later in the month from the same newspaper:

“ZEEDERBERG’S MAIL COACHES

His Honour the Administrator has given Mr C. H. Zeederberg full permission to raise an escort for his mail coaches, ![]() should events prove that same to be necessary…”

should events prove that same to be necessary…”

And a month later in September 1893:

"THE MATABELE MENACE; THE TULI FORCE

…Mr C.H. Zeederberg has been busy at Pretoria, selecting his troop of fifty who are to escort his coaches. Another batch of twenty-two horses and five men arrived from Pretoria yesterday, having been sent up by Mr Zeederberg to form part of the escort for the convoy of wagons which he is sending up to Victoria. These do not belong to the coach escort, which is to be formed separately, and of which the Chartered Company pay the expense, it being a mail escort."

Zeederberg's efforts at self-protection seem to have succeeded for there are no further accounts of delays, but of course, the Matabele War began from mid-October and this is probably why.

Travel by mail coach was no luxury

Travel by mail coach was almost non-stop and it is difficult to think of a more uncomfortable means of travel, although the ox-wagon was terribly slow and by bicycle a feat of arduous endurance! Day and night there was no rest for the passengers, except for short halts where fresh teams of mules were inspanned every two hours, as this was the limit of their endurance and there might be enough time for a hasty meal, unless it was the middle of the night. Up to twelve passengers would occupy the space that would be comfortable for four; other passengers would be balanced precariously on the mail bags heaped on the roof. Those who were sensible strapped themselves on for fear of falling asleep and being tossed off by a sudden jolt or swept off by an overhanging branch.

The driver would crack his whip above the team of mules to encourage them to keep moving, at times he might run alongside them to encourage them on. An average speed of about 10 kms (6 miles) per hour might be achieved but the deeply rutted tracks that served as a road always made travelling precarious. One moment the coach would be plunging like a ship at sea, next moment it would be heeling over at an angle that made a collapse look inevitable. The tracks descended steeply into the river-beds where the driver had to maintain speed through mud and over rocky beds to ensure the coach had sufficient momentum to negotiate the ascent on the other side.

There are a number of accounts of these tiring journeys. A good example is Travelling by coach in 1890 by Major A.G. Leonard under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

1893 rainy season disrupts the mail service

The Herald of 29 December 1893: "OUR COMMUNICATIONS: On Sunday last news was received here by the postal authorities that the up-mail due last Saturday has been delayed at the Umzingwane where the drift was twenty feet under water and the boat and wire swept away; the down-mail, which had left here the previous Sunday, had been stopped by the Lundi, which was also in flood. All mails were, however, so far safe. The down coach last week took with it a quantity of stout rope for repairs to the cradles at the rivers.”

The end of the Tuli – Salisbury mail service in July 1984

Matabeleland now became the commercial attraction and by mid-1894 the Wirsings’ were moving the mails into Bulawayo via Tati and the Mangwe Pass and Bezuidenhout had a new contract to carry the mails on to Salisbury via Gwelo and Iron Mine Hill. The lowveld route from Tuli had become redundant. It had begun as a route into Mashonaland which skirted Matabele territory and the need for this had now fallen away. Hollins and Zeederberg's contracts between Tuli and Victoria and between Victoria and Salisbury were terminated, by mutual consent, at the end of July 1894.

They were given a new contract between Pietersburg and Bulawayo and as an add-on to this contract they agreed to continue an ox-cart service from Tuli to Victoria for the rest of the 1894 dry season.[xviii] This was really just a pacifier to Victoria residents who might object to getting their mail by branch line from Iron Mine Hill.

An editorial in The Rhodesia Herald of 8 June 1894 summed up the situation: "THE POSTAL ROUTES

Mr Doel Zeederberg is in Salisbury for the special purpose of conferring…in regard to the contract that he has held for the past twelve months. The original terms were that Messrs Hollins and Zeederberg should run a mule service between Macloutsie and Salisbury in six days, connecting also with the firm’s Transvaal line from Pretoria, at Fort Tuli. This arrangement brought the capital of Rhodesia within nine days of the Rand and within eleven days of Cape Town…Messrs Hollins and Zeederberg have received notice that the service is to be discontinued, as far as subsidies go, the route via Gwela (sic) being preferable. The line between Bulawayo and Salisbury is in the hands of Mr Bezuidenhout, who after a certain date will undertake to run with mules and oxen in four days between the two places. Bulawayo is already connected with the Transvaal route by Hollins and Zeederberg, who initiated the fast service and do the distance between Tuli and there in two days. However, the Zeederberg coaches from Tuli to Salisbury are timed to four days, it is clear that by the round-about six-days' route, via Bulawayo, Salisbury loses two days. As regards Transvaal passengers and letters Messrs Hollins and Zeederberg have undertaken to run a coach during the dry season to Victoria unsubsidised, and are ready to continue the direct line to Salisbury at a half-subsidy price.”

On 6 August 1894 a Victoria resident commented on the Tuli-Victoria service as follows: “…the English and Colonial mail for our town arrived ![]() in excellent time on Thursday evening by Messrs Zeederberg's ox wagonette from Tuli, which was certainly more than we expected, but on the other hand, when the same vehicle started on its return journey on Saturday morning at nine o' clock, everybody was taken by surprise, and had we known of the fact of a coach starting then, we could have sent out letters by it. The Postmaster informs us, however, that he has had no instructions to despatch mails, by this route, so I suppose if we wish to write to the Tokwe our letters will make a round Journey to Buluwayo, Tuli etc."

in excellent time on Thursday evening by Messrs Zeederberg's ox wagonette from Tuli, which was certainly more than we expected, but on the other hand, when the same vehicle started on its return journey on Saturday morning at nine o' clock, everybody was taken by surprise, and had we known of the fact of a coach starting then, we could have sent out letters by it. The Postmaster informs us, however, that he has had no instructions to despatch mails, by this route, so I suppose if we wish to write to the Tokwe our letters will make a round Journey to Buluwayo, Tuli etc."

This service did not last long and had certainly ceased by October 1894. The route of the Pioneer Column - the thin red line - fell into virtual disuse, only four years after it had been cut from the bush by the advancing Pioneers. At the end of the decade, in 1900, it was reported that only four or five ox-wagons used the Tuli-Victoria road during the entire year.

Arrival of the Telegraph line

On 24 October 1893 Dan Judson was appointed Inspector of Telegraphs – was originally employed by the Cape telegraphs department from where many of the early staff were recruited. The telegraph line was regarded as a top-priority by the BSACo and its construction followed along the Pioneer Column route. By February 1892 Salisbury was in telegraphic communication with Mafeking and Cape Town. See the article Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Company under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Macloutsie was the principal transmitting station for Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe and the telegraph line had arrived in May 1891 and a Mr McGrath was the first telegraphist. The Macloutsie station became the first telegraph office controlled by the BSACo. In 1897 George Henry Eyre was appointed Postmaster-General and remained in post for 27 years.

From the date of his appointment telegraph staff began to be transferred, mostly to Bulawayo and the Macloutsie telegraph station began to lose importance. Once the railway arrived, the telegraph line was diverted to run alongside the railway line and the old route via Macloutsie fell into disuse.

References

D. Collis. The Thin Red Line: Tuli to Salisbury. Kindly lent to me by The Rhodesian Study Circle

H.C. Dann. The Cancellations of the Rhodesia’s and Nyasaland. Robson Lowe Ltd, London. Pdf from http://www.rhodesianstudycircle.org.uk/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2018....

A.S. Hickman. Men who made Rhodesia. The British South Africa Company, Salisbury 1960

A.G. Leonard. How We Made Rhodesia. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1973

H. Marshall Hole. Old Rhodesian Days. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1976

R.C. Smith. Rhodesia, a Postal History – its Stamps, Posts and Telegraphs. R.C. Smith, Salisbury 1967

[i] Rhodesia, a Postal History, P96

[ii] Men who Made Rhodesia, P26

[iii] How We Made Rhodesia, P153

[iv] The Thin Red Line: Tuli to Salisbury. Article 11 of "Memorandum of Instructions for Mr Colquhoun" dated 13 May 1890 at Kimberley.

[v] Ibid: Willoughby was to follow with the rear-guard and supply wagons

[vi] Ibid: NAZ LO5/2/3

[vii] Neither Robert Cary in The Pioneer Corps nor Adrian Darter in The Pioneers of Mashonaland mention Captain C.H. Tye, but Major A.G. Leonard i/c of E Troop at Fort Tuli in How We Made Rhodesia has a lot to say about him. He reports that Tye turned up with official position as Senior Commissariat Officer. Leonard claims he put the idea in Tye’s head that the BSACo should have its own Commissariat and Transport under an efficient officer and although he had no experience of either, managed to get himself appointed SCO as Rutherfoord Harris “is a bosom friend of his.” A little later Leonard is calling Tye ‘Prince Bluster Fluster’ as he says in the sphere of bluster “our SCO is a princely champion!” He describes after much wearisome wrangling and haggling, Tye and Hicks Beach are to have a shooting match for £10 a side in order to decide the momentous question as to which of them is the better shot. The match came off this morning at the BBP range and all of us were there to see Prince Bluster Fluster easily beaten by Hicks Beach as well as Laurie!

Sometime later Leonard writes: “Tye’s presence, so far, has made no appreciable difference in our commissariat and transport supply, which are still woefully deficient.”

[viii] Rhodesiana No. 13, December 1965

[ix] Rhodesia, a Postal History, P90

[x] Ibid, P92

[xi] Ibid, P91

[xii] Robert George Burnett (brother of Albert Edward Burnett) was a Lieutenant in the Pioneer Column, initially in charge of the native labourers, later as Transport officer.

[xiii] Captain Randolph Nesbitt was later to win fame and the VC in the Mashona Rebellion of First Chimurenga with the Mazoe patrol

[xiv] Rhodesia, a Postal History, P126

[xv] Old Rhodesian Days, P32

[xvi] Sergeant-Major Lyons-Montgomery, was recruit No. 1 on the BSACo police attestation rolls

[xvii] The contract also provided for at least a four hour stop at the Post Office at Victoria; for a weight of mail not exceeding 1000 lbs. per conveyance; for the contractor to hire and maintain the Company's boats on the rivers and for the Postmaster-General to let these boats at one shilling per boat for the twelve month period; for the "Contractor to pay the Conductors now on the line at their current rates of pay and the cost of rations of seven Europeans and six Colonial boys for the period of one month from the date hereof.

[xviii] Clause 48 of the contract "The Contractors hereby undertake to run a weekly passenger service between Tuli and Victoria and vice versa in eighty-four hours during this dry season for which service no subsidy shall be claimed or paid. This service shall continue until the Company has received one month's notice in writing from the Contractors of their intention to discontinue it; no fines on this section.