James Theodore Bent and Mabel Virginia Anna Bent gave many artefacts to the British Museum from Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) collected during and after their excavation at Great Zimbabwe in 1891

Introduction

The story of the Bents’ excavation at Great Zimbabwe is told in the article The Bent’s archaeological expedition to Great Zimbabwe in 1891 and the prominent part played by Mabel Bent under Masvingo Province on the www.zimfieldguide.com website. Much of the information in this article comes from the very comprehensive website Theodore and Mabel Bent (http://tambent.com/) by the author Gerald Brisch. Theodore Bent wrote over 150 articles, papers and lectures with many listed on the http://tambent.com website. Both Theodore and Mabel Bent were prolific authors and their books are also listed on the website. Other information and details of their journey came from Theodore Bent’s book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland (1892) written very rapidly on their return home at 13 Great Cumberland Place, London – it proved very popular and ran to five editions. Finally, I used facsimile copies of Mabel’s notebooks stored at the Hellenic Society Archive, University College London.

The Bents’ excavations at Great Zimbabwe

In 1877, Theodore Bent married Mabel (née Hall-Dare) (1847-1929) who became his constant companion, photographer, illustrator and diarist on all his travels and from the time of their marriage, they went abroad nearly every year.

Peter Garlake gives a number of quotes that are relevant to these first excavations carried out at Great Zimbabwe and are repeated below. Bent approached the question of Great Zimbabwe believing, like almost everyone, that its origins must lie with a civilised and ancient people from outside Africa and he had in fact, been chosen because of his prior archaeological work on the Phoenicians.

But as far as the Phoenicians were concerned the excavations were showing little evidence of their presence. “Now, of course it is a great temptation to talk of Phoenician ruins when there is anything like gold to be found in connection with them, but from my own personal experience of Phoenician ruins I cannot say that [the Great Zimbabwe ruins] bear the slightest resemblance whatsoever.” [1] Every local resident they met was keen to perpetuate the Phoenician myth as was their patron, the British South Africa Company and the Bent’s soon saw that the archaeological evidence was contrary to this idea, “the names of King Solomon and the Queen of Sheba were on everybody's lips and have become so distasteful to us that we never expect to hear them again without an involuntary shudder.”

In June 1891 their excavation work around the Conical Tower within the Great Enclosure soon disproved the theories that Great Zimbabwe was ancient and of foreign origin. “We found but little depth of soil, very little debris, and indications of a native occupation of the place up to a very recent date” and Bent is quoted by his local guide C.C. Meredith as saying, “I have not much faith in the antiquity of these ruins, I think they are native. Everything we have so far is native.”

Wikipedia adapted by the author: Great Zimbabwe

To quote direct from Peter Garlake, “Work in the elliptical building [Great Enclosure] was abandoned within a fortnight and excavations started in the eastern enclosure of the Hill Ruin [Hill Complex] ‘because it occurred to us that a spot situated on the shady side of the hill might possibly be free from native desecration.’ This was not to be. Throughout the deposits there were great numbers of household objects: sherds from hand built vessels, pottery spindle whorls, iron, bronze and copper spearheads, arrowheads, axes, adzes and hoes and gold working equipment such as tuyères and crucibles. Most of these still seemed indistinguishable from contemporary Karanga articles.”[2]

Yet Bent still continued to be focussed on Phoenician origins. In the Great Enclosure were found four birds carved in soapstone on monoliths and flat soapstone dishes with abstract patterns or animals carved around the edges, small carved cylinders that looked like phalli and an ingot mould and were unique to the site. Had similar objects been found elsewhere? Bent theorised the birds might copy stelae from Assyria, Mycenae, Phoenician Cyprus, Egypt and Sudan: the patterns on some of the objects resembled Phoenician motifs, the mould resembled one found in Cornwall and thought to be Phoenician.

Similarly with the architecture. The shape of the Great Enclosure resembled the temple of Marib in Southern Arabia, the Conical Tower looked like a Phoenician temple on a Byblos coin as well as structures in Assyria, Malta and Sardinia. The birds might symbolize gods or goddesses, the disc patterns indicate sun worship, the soapstone monoliths and phalli were “grosser forms of nature-worship”[3] and so on.

From his above muddled ideas Bent decided there was, “little room for doubt that the builders and workers of the Great Zimbabwe came from the Arabian Peninsula… a prehistoric race built the ruins…which eventually became influenced and perhaps absorbed in the…organisations of the Semite…a northern race coming from Arabia…closely akin to the Phoenician and Egyptian…and eventually developing into the more civilised races of the ancient world.”

His final conclusions, “that the ruins and the things in them are not in any way connected with any known African race” seems extraordinary in view of all the artefacts excavated by the Bents’ in 1891.”

The Collection of Bent artefacts at the British Museum

The numbers of objects donated below represent only those listed on the British Museum’s online collection, there may well be others in museum storage and not listed.

In all, the British Museum lists on their online collection 583 objects given by Theodore Bent. Those from present-day Zimbabwe number 272 objects (i.e. 47%) the remainder come from their archaeological excavations in Greece, the Cyclades, Antiparos, Ethiopia, etc.

Mabel Bent gave a further 155 objects. Those from present-day Zimbabwe number 26 objects with the remainder from Iran, the Cyclades, Yemen, Arabia, Greece, etc.

For the purposes of this article I have only shown a representative sample of the objects that the Bent’s collected or excavated on their 1891 expedition to present-day Zimbabwe

British Museum objects listed mostly alphabetically and by location area where known. All the images are © The Trustees of the British Museum and appear under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence

Armlet made of eight strands covered with copper or iron Arm-ring made of brass wire twisted spirally round

wire, held in place by five triple copper clips (Af1892,0714.13) some pliable substance (Af1892,0714.13)

.

.

Armlet made of leather, with small penannular pieces Armlet made of spirally-twisted brass and copper wire

of iron, copper and brass wire nipped on at intervals (Af1892,0714.7)

(Af1892,0714.7)

Axe with iron blade, wooden handle with incised Axe with iron head and wooden shaft

triangle design (Af1892,0714.71) (Af1892,0714.172)

Bag woven from a strip of bark Bone disc with incised swirl design Bracelet with beads made of copper with

fibre with a long loop handle (Af1979,01.4521) leather, beads (brass and copper) and iron wire (Af1892,0714.62) (Af1892,0714.179)

Bracelet made of polished leather Bracelets can be worn on the wrist or arm Bundle of 24 armlets made of plaited yellow

(Af1949,46.641) (Af1949,46.640.a-b) and black grass (Af1892,0714.179)

Cap made of woven grass Carved wooden bowl with incised Carved wooden spoon with design of incised

in a zig-zag pattern diamond pattern around the rim triangles along the handle

(Af1892,0714.161) (Af1892,0714.52) (Af1892,0714.140)

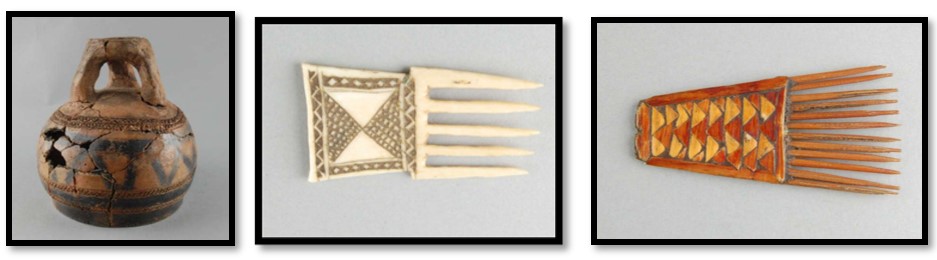

Circular vessel of burnished Comb made with bone with Comb made of cane and grass with zig-zag

earthenware with incised zig-zag, incised zig-zag and triangle design design Mtoko’s country (Af1979,01.4483)

red and black graphite designs Mtoko’s country (Af1979,01.4491)

Chibi’s country (Af1892,0714.177)

Comb made of wood with incised Divining bones (4) with incised triangle and Divining tablets carved in wood

triangle design. Mtoko’s country diamond design attached with fibre string (Af1892,0714.73)

(Af1979,01.4485) (Af1979,01.4520)

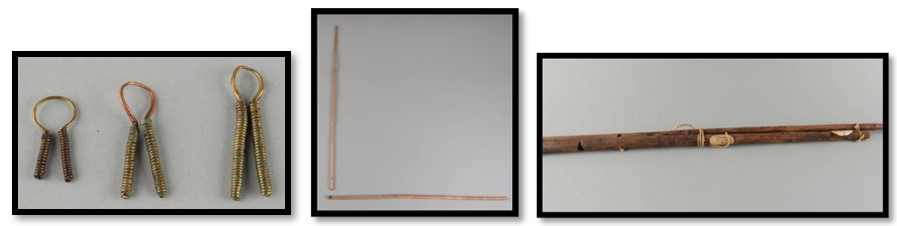

Ear ornament made of pulled brass and Fire-stick – wood (female) Fire-stick – wood (male)

copper wire. Mtoko’s country (Af1892,0714.39.a) (Af1892,0714.38.b)

(Af1979,01.4519.a-b)

Gourd dipper ladle with design of black triangles, handle Grease holder Hat made of woven grass with flat brim

with chequers (Af1892,0714.59) with thong Gambidji’s country (Af1892,0714.191)

(Af1892,0714.101.a)

Head rest with design of two concentric circles Head rest with two legs connected by rectangular

on the base (Af1892,0714.156) cross-piece. Chibi’s country (Af1892,0714.151)

Head rest with incised concentric circle design Head rest made of plaited string. Chibi’s country

(Af1892,0714.25) (Af1892,0714.159)

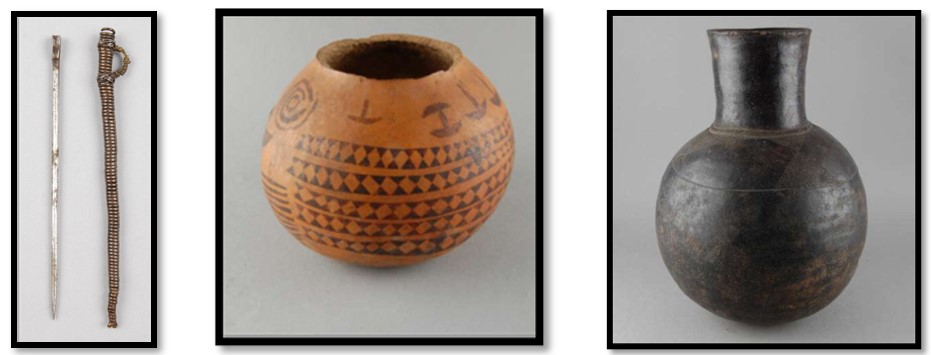

Iron dagger with wooden Knife made of iron Knife with iron blade and wooden

Sheath, the handle bound in a wooden sheath handle bound with plaited brass wire

with brass wire (Af1926,0410.3.a) (Af1892,0714.133.a) (Af1892,0714.132.a)

Mbira, musical instrument made of wood and iron Necklace with two snuff boxes and Necklace made of flat, circular

with fibre string. Chibi’s country (Af1892,0714.132.a) a needle case made of leather, brass ostrich eggshell beads and

and steel beads, seed pods fibre string

(Af1979,01.4510) (Af1979,01.4511.a)

Needle made of iron Pot made from a gourd, decorated with a Pot made from black burnished earthenware,

with wire sheath black diamond and zig-zag design globular body and cylindrical neck, incised neck

(Af1892,0714.108.a) (Af1892,0714.66) triangle pattern around base. Chibi’s country

(Af1892,0714.149)

Pot made of buff earthenware, spherical body coloured Pots of buff earthenware with plumbago and red triangular

patterns black with plumbago and red triangle pattern, and inward curved cylindrical necks (Af1892,0714.147)

neck 8-shape (Af1892,0714.148)

Pot with tripod base and intricate incised Pottery vessel with loop; string with incised zig-zag design

Diamond, triangle and incised line design Chibi’s country (Af1979,01.4537)

Kunzi’s country (Af1892,0714.189)

Quiver made with hide, Rattle made of cane framework enclosing Sack of woven bark fibre ornamented with

containing 11 arrows a number of black spherical seeds transverse red stripes (Af1892,0714.3)

(Af1892,0714.36.a) Chibi’s country (Af1892,0714.24)

Snuff horn container decorated with plaited iron and Snuff bottle with bands of copper Snuff bottle carved from

Brass wire, the large end with wooden stopper and brass wire, leather strap wood with incised line design

(Af1892,0714.21) (Af1892,0714.84.a) (Af1892,0714.87.a)

Snuff box made of cane with Snuff box made from a gourd with Snuff bottle made from a gourd with

incised line design, cloth loop zig-zag line design and leather strap stitches of brass wire in triangle designs

Chibi’s country (Af1892,0714.95.a) (Af1892,0714.113.a) (Af1892,0714.85)

Snuff bottle of wood attached by a thong String of glass beads on leather strap Woman’s girdle with skin scrapers and

to pieces of bone, seeds and blue glass beads Chibi’s country medical phials attached. Kunzi’s country

(Af1892,0714.100.a) (Af1979,01.4492.a-h) (Af1892,0714.181)

Woven basket with grass plaited in a spiral Woven material of bark fibre string Beer strainer made of woven palm leaf

(Af1892,0714.112) (Af1892,0714.34) Mtoko’s country (Af1892,0714.32)

References

Gerald Brisch. The Bent Archive (http://tambent.com/)

British Museum online Collections (https://www.britishmuseum.org/)

Peter S. Garlake. Great Zimbabwe. Thames and Hudson, London 1973

J. Theodore Bent. The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia, Gold Series Vol 5, Bulawayo, 1969

(First Edition 1892, Longman Green & Co, London)