An Introduction to the significance of Mapungubwe

The Limpopo-Shashe river area is important for Stone Age sites and rockart with evidence that human development stretches back over 50,000 years. Mapungubwe is recognised as the capital of an important southern African state that existed from about 1220 to 1300 AD. The state was the centre of an extensive trade network that stretched down the Limpopo river to the Indian Ocean coast in which goods such as gold, ivory and animal skins were exchanged for imported items such as glass beads, cotton and silk goods.

In South Africa it is recognised as one of the earliest class-based societies with rulers who isolated themselves from the common people – a concept known as sacred leadership. The society was hierarchical with the rulers living on the hill and the common people living on the plains below.

The National Park includes an Interpretation Centre that explains the function and importance of Mapungubwe and includes a replica of the famous gold rhino, providing evidence of the wealth and status of the kingdom.

The Mapungubwe cultural landscape was declared a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2003

The National Park is important for its rich biodiversity of plant life and wildlife situated at the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe rivers at the junction of the three countries of South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe.

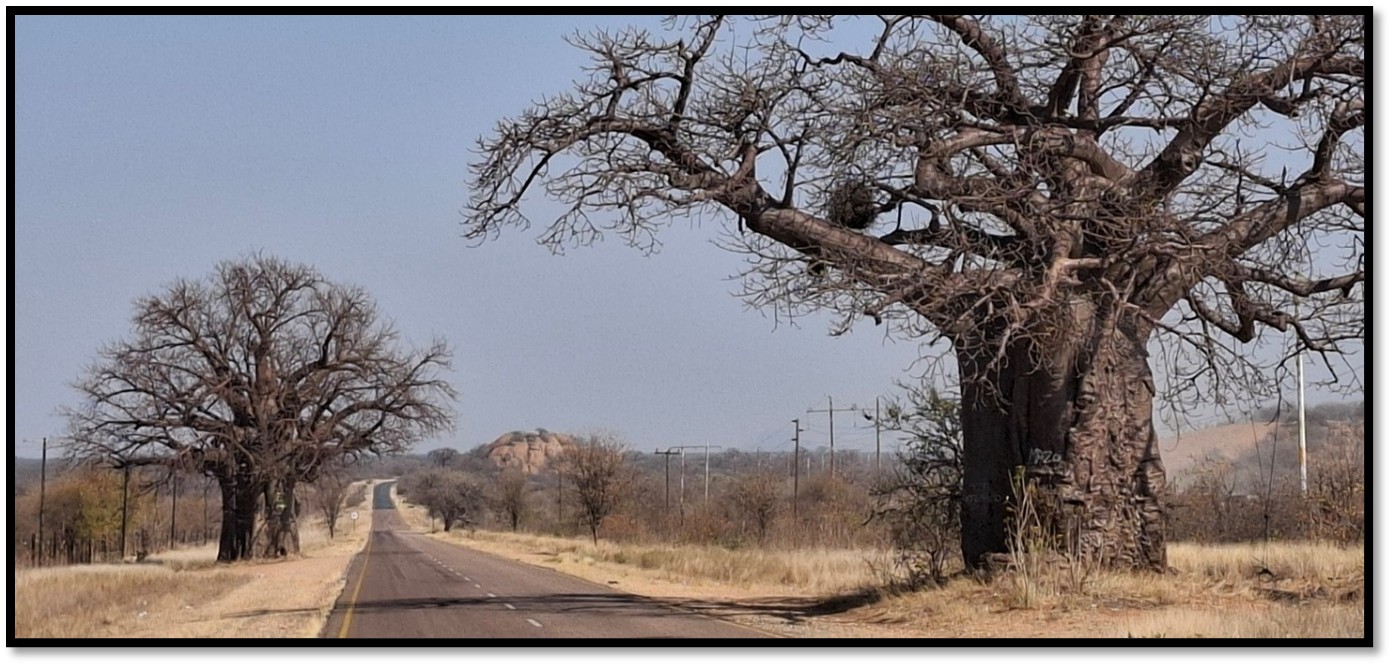

From Johannesburg or Pretoria take the N1 North through Polokwane. At Musina take the R521 west to the main gate of the Mapungubwe National Park. The roads on this route are all tarred and in good condition.

The roads within the National Park are mostly gravel except from the main gate to the Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre which is tarred. The gravel roads in October 2025 were in good condition and 4WD is not necessary although a high clearance vehicle is recommended.

Where is Mapungubwe?

Background to Mapungubwe

Mapungubwe Hill was first investigated in 1932 by a local farmer, E.S.J. van Graan and his son led by a local guide named Mowena. They found bits of walling, some pottery and gold artefacts. The son realised the value of the site and contacted Professor Fouché, head of the history department at the University of Pretoria who obtained excavation rights and ownership of any artefacts.

In June 1933, the University of Pretoria bought the farm and soon after began the archaeological excavations which continued between 1934 – 1940.

What’s the importance of Mapungubwe?

Mapungubwe is important for the discoveries made in the 1930’s by archaeologists from the University of Pretoria.

The golden rhinoceros of Mapungubwe

However, these archaeological findings were augmented by the recording of the oral traditions of local African communities by N.J. van Warmelo, a government ethnologist who advocated the site’s importance in the 1940’s and carried out oral research and studies on the Venda people who are linked with the Mapungubwe state although by the 1930’s the area was largely inhabited by Tswana rather than Venda communities.

The fact that Schroda and K2, the ancestors of Mapungubwe, as well as Mapungubwe itself, had been so little disturbed until excavated by archaeologists meant they were able to reconstruct their changing uses and development and construct an accurate description of the landscape as it evolved into what has been termed the Zimbabwe Culture.[1]

For this reason Mapungubwe has become one of South Africa’s newest UNESCO World Heritage listings.

Understanding what the term ‘Zimbabwe Culture’ means

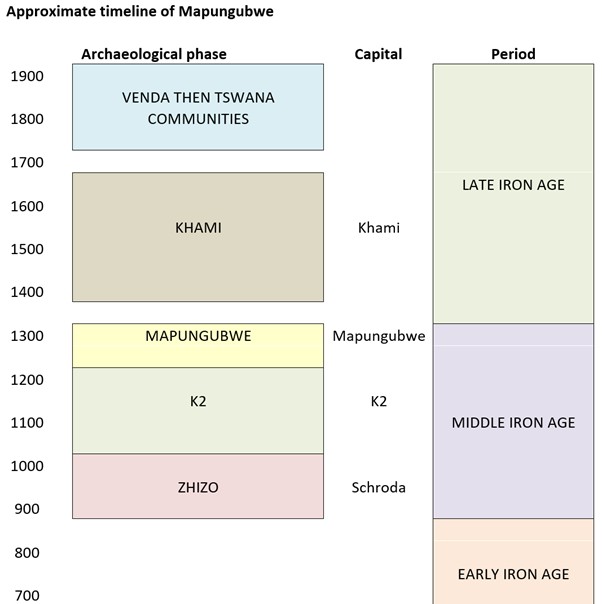

Between approximately 900 – 1300 AD, termed the middle Iron-Age in the graphic below, African communities in the Limpopo-Shashe Valley developed a new type of complex society that was characterised by distinct class divisions and what is called sacred leadership. So how do these terms contribute to the collective description of Zimbabwe Culture?

Zimbabwe Culture is the term archaeologists use to describe societies that are based on:

- Class division – this refers to a distinct split between the rulers that form an elite class and the common people who form the majority of members of a society

- Sacred leadership – this relates to the link between the rulers and the land and the rulers link between their ancestors and God. Mixed up in this is the ruler’s role in rain-making, an important rite in African culture.

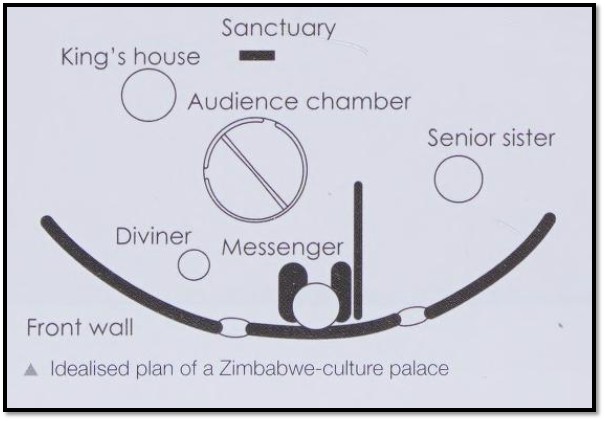

Zimbabwe Culture gradually evolved within the Mapungubwe region with the beginnings of a class-based society in the period that archaeologists call K2. From communities based around what Huffman calls Central Cattle Pattern (CCP)[2] where the settlement centre was dominated by men and the outer residential areas dominated by women came a new spatial pattern where the rulers became aloof from the commoners and began to inhabit a private and sacred area – later dominated at Great Zimbabwe by dry-stone walling apart from the commoners.

In its final stages one axis of the court became primarily a male-dominated area with a separate area for the ruler’s wives and designated areas for the making of medicine, court officials and messengers. This area was then protected by a ring of guards.

There are three capitals within the Mapungubwe National Park – each representing a distinct period of time. They were:

- Schroda (900 – 1000 AD)

- K2 (1000 – 1220 AD)

- Mapungubwe (1220 – 1300 AD)

Of the three, the only one still with visible remains is Mapungubwe. Most archaeologists view Mapungubwe as the prototype of Great Zimbabwe, another UNESCO World Heritage site, 300 kilometres north-east of Mapungubwe.

Early Iron Age

The first Iron Age farmers moved into the Mapungubwe area between 350 – 450 AD when the rainfall appears to have been adequate for agriculture. Their pottery has been found at Mapungubwe and at least three other rainmaking hills. Thereafter the rainfall appears to have worsened and these early Iron Age people left the area for about 450 years.

Schroda

Between 600 - 900 AD little farming seems to have taken place in the Shashe-Limpopo Valley because of the unsuitable climate. The Zhizo people lived in south-western Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana where there was higher rainfall.

About 900 AD some of the Zhizo moved south from Zimbabwe and established themselves at Schroda where they kept cattle and goats while the remains of grain bins and grinding stones show they grew sorghum and millet. At this time, their communities were of a traditional type with their chief living amongst the people, but distinguished by his wealth accumulated through court fines, tributes, raiding and the high bride price of his daughters.

The Zhizo are primarily identified through their distinctive pottery that is generally named after the first location where it was found. The excavations at Schroda uncovered a large number of clay figurines, including cattle, humans and fantasy creatures that were probably used during initiation ceremonies.

British Museum: clay animal figurines from Schroda

Archaeologists believe that the main cause of the Zhizo communities moving to Schroda were the large elephant herds thriving on the widespread vleis centred on the Limpopo-Shashe river confluence. This is confirmed by ivory artefacts and imported glass beads found in the Zhizo levels at Schroda.

Schroda and the Zhizo state seem to have existed for about 100 years.

International trade

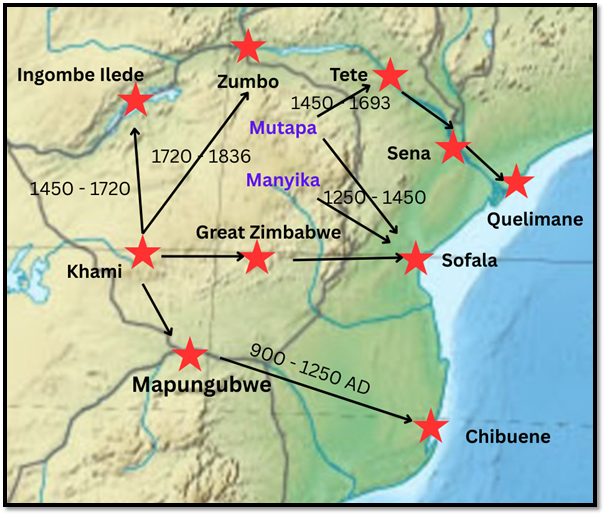

Ivory was already a commodity traded from present-day Zimbabwe. A large number of ivory artefacts from Schroda provide evidence of an outgoing international trade, but the trade probably also included gold, rhino horn, leopard skin and iron. They were taken down to the Indian Ocean coast at Chibuene and transported in Arab Swahili dhows to northern destinations including Kilwa and Mogadishu and then India. Exchange goods included glass beads,[3] cotton and silk cloth and ceramics.

K2

K2 was the new capital between 1000 – 1200 AD. Around 1000 AD the Zhizo people were displaced by a Leopard’s Kopje[4] community who spoke Kalanga, a western form of Shona; the Zhizo[5] people moving into western Botswana.[6] By 1200 AD probably 1,500 – 2,000 people were resident at K2 at Leokwe Hill,[7] probably organised into several kraals, each under a headman with the largest under a chief. Traditionally, the chief ruled over the court, always situated near the cattle kraal, where disputes between neighbourhoods and districts and cases of witchcraft were heard.

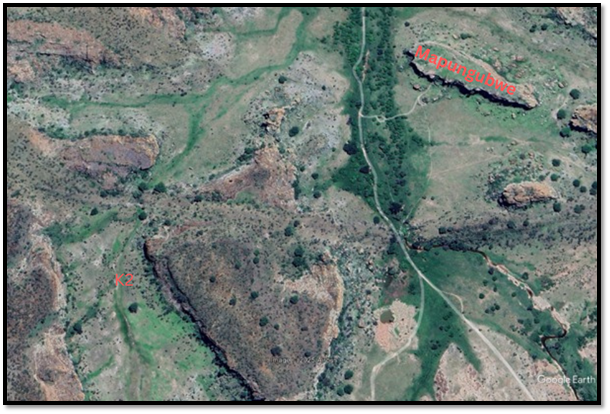

K2 showing the excavation site

A large number of ivory artefacts were excavated in the 1930’s at K2 from complete elephant tusks to arm-bands, bracelets and chips. But there were also knife-hilts that indicate they were made for the international trade. Thousands of imported beads ranging in colour from blue and turquoise to green from India and Egypt were also excavated and probably formed payment for the ivory. The beads were so plentiful that the K2 community melted them down into clay moulds to form large conglomerate beads called ‘garden rollers.’

K2 also revealed copper beads and bracelets along with the associated slag, broken crucibles and tuyeres. 75 pieces of ironware were excavated from iron spear tips to bangles, round and square wire, pendants and an iron knife with an ivory handle. Notably copper is only found at Musina, 80 kms away and iron even further afield.

Excavations at K2 disclosed that the settlement organisation followed what is called the Central Cattle Pattern (CCP) with the chief’s residence on the western side of the complex with houses and grain bins on the other side of a cattle kraal in the centre that made up the men’s domain - all connected by social ranking. The circular homes made of mud and dhaka would have red walls and smooth white clay floors, all covered by a thatched roof.[8]

Huffman states the cattle kraal was the main part of the men’s area who were buried within or nearby and cattle sacrifices were made here to male ancestors. A special midden contained the debris from the cattle kraal. Ash from the men’s fireplaces, broken pots and cattle bones caused this special midden to reach a height of four metres above ground.[9]

The excavations also uncovered over 90 graves. Most were women and children buried in a foetal position facing west, towards the sunset. Men buried on their right-hand side, women on their left. The same pattern of burial often prevails today with people buried in those areas associated with them in life. Thus married women were buried behind their hut, children where they played, infants under the house where they were born, men in or near the cattle kraal.

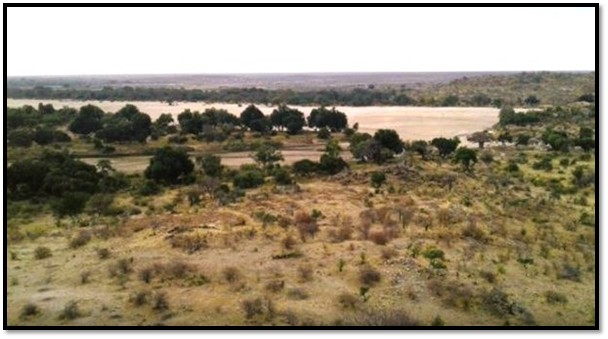

In contrast to the Zhizo communities, K2 people lived in scattered kraals under a headman often along the Limpopo floodplains where they cultivated grains such as sorghum and millet in the rich alluvial soils and climate data indicates the rainfall was higher than today.

View towards K2 area from Mapungubwe Hill

About 1000 AD Zhizo pottery disappears and is replaced by K2 pottery that is associated with Leopard’s Kopje ceramics associated with western Shona-speaking people and dating between 1000 – 1200 AD.[10]

The social changes within African society at K2 that gave rise to Mapungubwe

However during the K2 period the spatial organisation began to change with the cattle moving away from the centre of the kraal and all cattle becoming more or less royal property. Also the process began for the evolution of two courts; one for the rulers and another for commoners. This marks the beginning of a class division. The increasing prosperity enjoyed by the ruling families from the international trade with the East African coast was resulting in a wealthy elite and ruling class.

This growing split was reinforced by a population fed by the increased agricultural productiveness of the Limpopo-Shashe flood plains. Huffman writes that these two factors transformed K2 society from one based on social ranking to one based on social class.[11] In addition the rulers took on the function of rainmaking that had been previously undertaken by commoner rainmakers.

Rainmaking

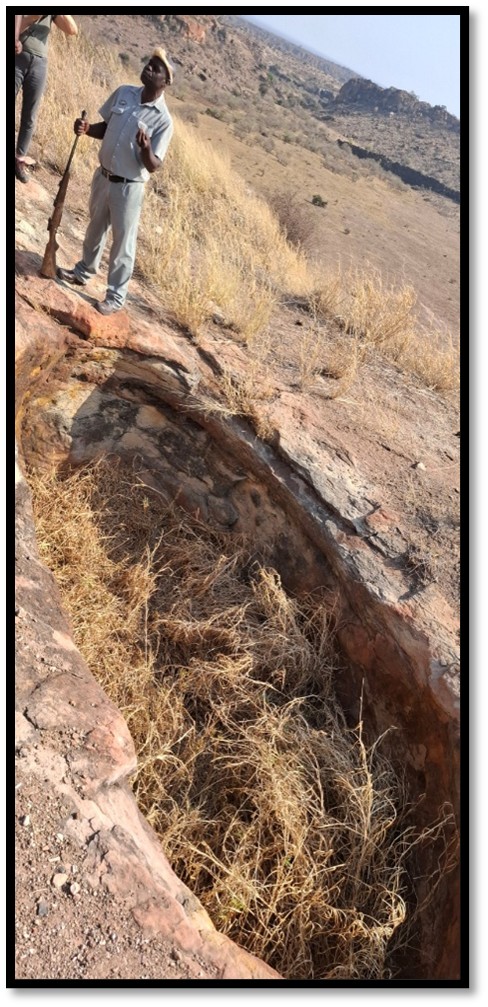

Rain-making hill within the Mapungubwe cultural landscape

Rainmaking has always been a sacred and secret ritual connected with the agricultural cycle. The ceremonies would be centred around the chief although they were often not in charge. The actual rainmakers might be those considered most connected with the ancient spirits of the land…San hunter-gatherers, for example.

Between September and November rituals would be carried out connected with rainmaking to bring the clouds and the people would work in a tribute field before beginning on their own. At the end of the rainy season the chief would lead a harvest celebration that included music, dancing, beer and feasting.

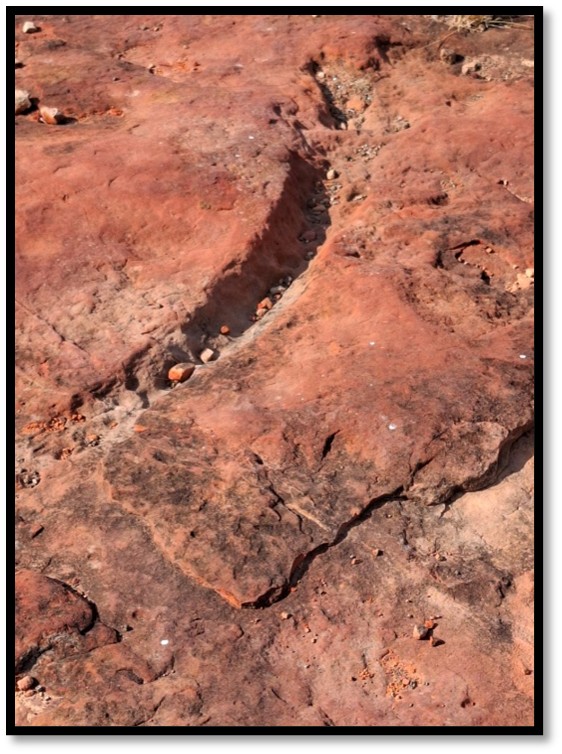

Special rainmaking hills had certain qualities – steep sides with difficult access, a space too small for huts and man-made dolly holes or shallow cupules. Sorghum would be left as well as ritual beer to satisfy the spirits.

Man-made cupules at Mapungubwe Hill

A water cistern on Mapungubwe Hill

Grain storage site on Mapungubwe Hill

A big difference occurs with the transition from CCP at Schroda and K2 to the Zimbabwe Culture at Mapungubwe where the elite became associated with rainmaking. This now took place at the back of the ruler’s palace, not on top of an isolated rainmaking hill and the sacred leader became the rainmaker praying to God through his ancestors in rituals that involved beer and the sacrifice of a black bull to satisfy the spirits.

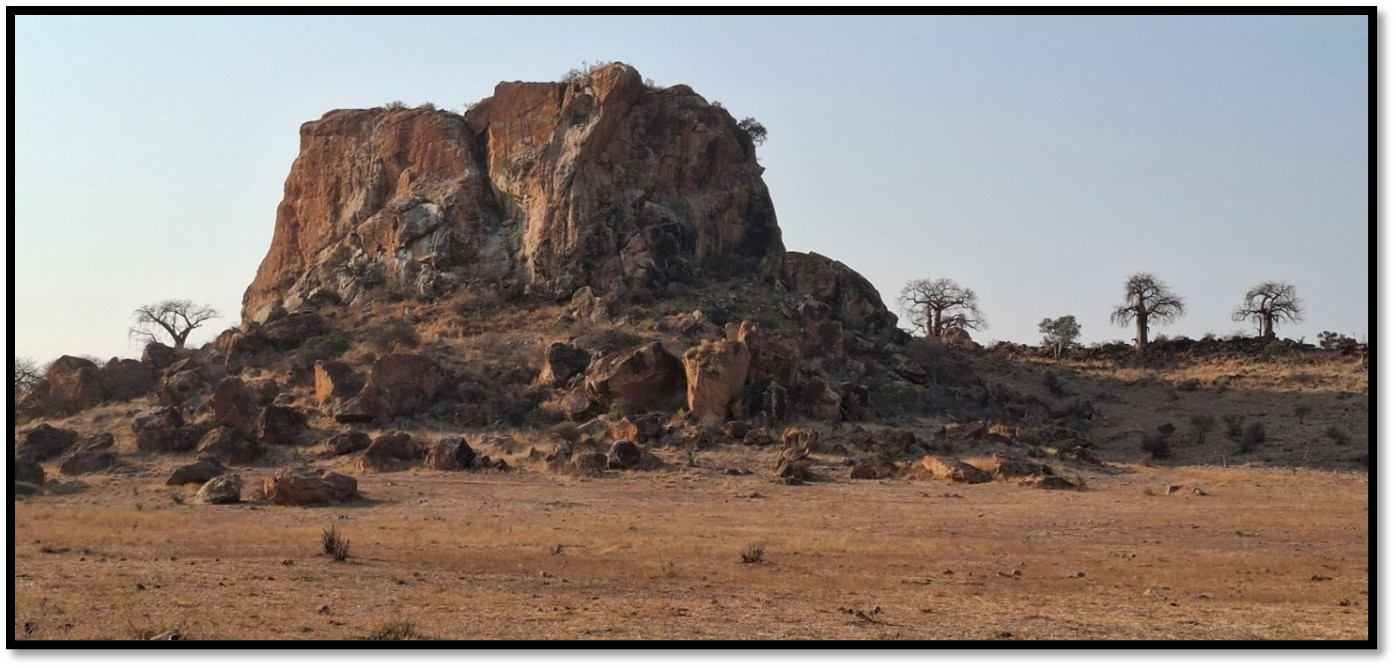

Mapungubwe

Mapungubwe became the capital circa 1220 AD. The organisation of society was now very different from the traditional pattern. The ruler lived on the summit of the hill, separated from the people, in ritual seclusion. This is the first time in southern Africa that a ruler is physically separated from the commoners and although Mapungubwe was only inhabited between 1220 – 1300 AD the new spatial organisation involving ritual seclusion set the ruler apart from family as well as the commoners. Huffman writes, “Mapungubwe was probably established so that the new socio-political order could be spatially expressed.”[12]

Google Earth: graphic of Mapungubwe and K2

The new spatial layout

The commoners settled below Mapungubwe Hill and to the west. The rulers settled on the hill.

Huffman writes, “This was the first time in the prehistory of Southern Africa that a senior leader was so physically separated from his followers. This new spatial pattern is associated with class distinction and it represents the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture.

Until now, Mapungubwe had been a rain making hill. By living on top, the leader acquired the power of the place. His new location also emphasised the link between himself, his ancestors and rainmaking. This link is an essential characteristic of sacred leadership.”[13]

The large boulder was the site of the commoners court at the base of Mapungubwe Hill

Excavations undertaken in the 1980’s show that the grey soil marks an extensive residential area and revealed the occupation sequence. The earliest occupation was from 500 AD by early Iron-Age farmers who used Mapungubwe Hill for rainmaking. In 1000-1220 AD, when K2 was the capital, some villagers lived at the base of the hill. In the period 1220-1250 AD there was a buildup of the residential population at the base of the hill. Marked by an horizon of burnt ash that Huffman suggests might be the result of the people burning down the old huts to start the new capital.

The commoner area from the summit of Mapungubwe Hill

The Ruler’s Court

The ruler was now represented by a specially-designated brother who became the second most important person at Mapungubwe with messengers to summon people to court and court officials who reported to him. His office probably a stone-walled space against the large boulder in the centre of the above photo and a terrace wall in front for people who were attending court.

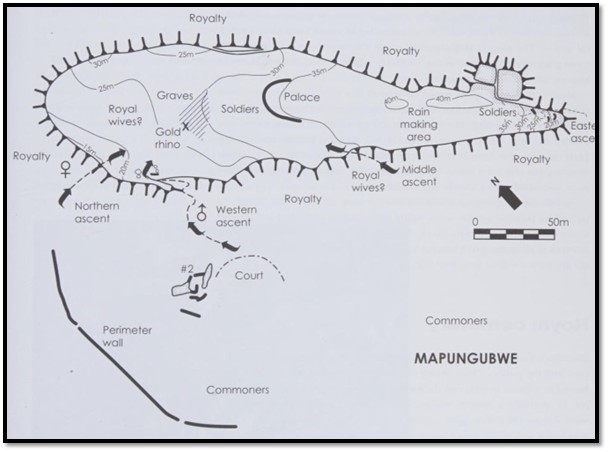

Plan layout of Mapungubwe

The specially-designated brother may have lived in a small residential area that was excavated behind the court.

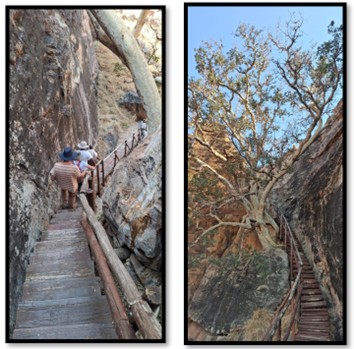

Ascending Mapungubwe

When Mapungubwe was the capital there were four ascents that are shown on the above plan. The western ascent from behind the court had pairs of holes drilled into the rock that had poles that supported a stone stairway and appears to have been the main ascent. The other ascents likely had soldier guards on the hill summit.

Present-day ascent of Mapungubwe, also the main ascent on the plan

First Ruler

Excavations in the 1930’s and 1980’s revealed numerous hut floors with the earliest dating to circa 1220 AD and the first ruler on Mapungubwe Hill. One hut had a wide verandah with two fireplaces on either side of a seat and may have been for the ruler’s diviner. Another had the burnt remains of a door opposite the fireplace and may have been the ruler’s sleeping room. Nearby would have been an audience chamber for the ruler to receive visitors after they had been welcomed by the ruler’s messenger who had his own hut.

Dry-stone walling

Huffman believes that the magnificent dry-stone walling at Great Zimbabwe was initiated at Mapungubwe.[14]

He believed that three walling functions helped class division and sacred leadership in the form of (1) prestige enclosures, (2) hut terraces and (3) long boundaries. Most importantly, prestige walling provided ritual seclusion for the ruler. Retaining walls with irregular coursing in a vertical face were built as the ruler’s palace front and for the office of the court officials. In contrast, the palace huts were supported by roughly piled terraces. Finally the boundaries of the residential area were marked by long stretches of rough walling.

Photo Shadrick Chirikure: retaining walls of the rulers palace

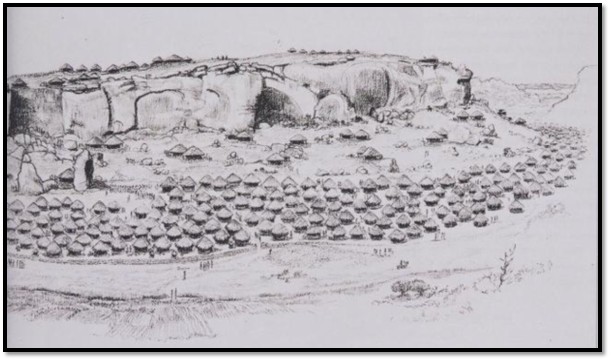

Southern Africa’s largest known settlement and first town

Archaeologists believe that by 1250 AD Mapungubwe had a population of around 5,000 people. The artists’ impression below shows the commoner population living on the southern terrace and on the plateau to the north-east and east.

The rulers lived in seclusion on the summit of Mapungubwe Hill.

Artists impression of the settlement around Mapungubwe[15]

The second Ruler

By 1250 AD the ruler’s residence had shifted to the middle of Mapungubwe Hill where he was supported by a small number of court officials. The physical separation of the ruler was an expression of sacred leadership.

Idealised plan of a Zimbabwe Culture palace[16]

At the front of the ruler’s residence was the ruler’s messenger who would greet visitors and take them to the diviner to establish if they had any evil intent. From here they would be taken to the audience chamber to meet the ruler. The audience chamber was divided into two by a dhaka wall; the visitor on one side and the ruler and his court officials on the other side. The ruler slept in a small hut with a wooden door in a secret location. The youngest wives lived in the back of the palace, also in a secret location. In the ritual area would be stored the national drums and items used in sacred rituals, including for rainmaking.

A male entourage of soldiers, musicians and praise singers also surrounded the ruler. A tsoro board carved into the rock indicates that male soldiers guarding the ruler were at this spot. Most of the time the musicians played mbira’s and xylophones within the ruler’s hearing; on special occasions a praise singer would be added.

A circular grove in the sandstone served to anchor a hut on Mapungubwe Hill

Tsoro board on Mapungubwe Hill

Royal wives

The number of wives reflected the ruler’s wealth and political power. Most would have lived in a special area outside the ruler’s residence but on Mapungubwe Hill. The north-west end of the Hill had a grindstone and this may have been the royal wives area. Some of the wives may have lived in outlying districts under the supervision of a headman or petty chief.

The Royal cemetery

The 1930’s excavations revealed a royal cemetery between the possible women’s area and the ruler’s residence. There were 23 graves; most in a flexed position lying on their sides, but 3 were different. No 10 was a middle-aged man also facing west wearing a necklace of gold beads and cowrie shells with some objects covered in gold foil, one resembling a crocodile. No 14 was probably a woman in a sitting position facing west with 100 gold bangles around her ankles and 12,000 gold beads and 26,000 glass beads. The third, known as ‘the original gold burial’ was buried with a wooden headrest and three objects covered in gold foil – a bowl, a sceptre and a rhino. There were two more rhinos in the cemetery, but it’s not known what graves they came from. They are now declared a national treasure.

These items are clearly related to the status of the individuals in the graves.

The excavated area is the site of the royal cemetery where the graves and golden rhino were found

The gold artefacts

Huffman believes there is symbolism behind the rhino artefact because it represents a black rhino - known for its dangerous behaviour, unpredictability, power and solitary life – all characteristics of sacred leaders. He believes even a black rhino’s propensity to stamp the ground and throw soil and leaves into the air is mirrored by a dance that the sacred leader performed on the graves of his ancestors.[17]

Photo University of Pretoria: the major gold artefacts from Mapungubwe

Precolonial gold trade

Gold production and trading from the northern plateau of present-day Zimbabwe and the Limpopo Valley has taken place for more than twelve hundred years and was well-established by the 11th Century when Kilwa began its rise to prominence on the back of the gold shipped up the East African coast from Sofala. See the article How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The gold trade was conducted by the Iron-Age communities referred to in this article – Schroda, K2, Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe who controlled the trade routes from the interior to the Indian ocean coast. A significant part of this trade was gold, confirmed by the 13th Century archaeological evidence in the form of gold artefacts found at Mapungubwe.

Swahili traders established the routes up the East African coast and their dhows exported gold across the Indian Ocean to Arabia, Persia (Iran) India and even China via the Swahili city-states of Sofala, Kilwa and Mogadishu. See the article Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century? under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Gold production

Al-Masudi, an Arab historian and geographer, writes about the gold and ivory trade in the 10th Century from Sofala when it is believed most gold was exported. By the 13th Century gold objects were actually being manufactured at Mapungubwe and now had acquired an indigenous value and was not only exported as an exchange food.

Huffman writes that gold was processed in the same way as copper by first being melted in a clay crucible in a clay furnace to produce nodules. These were then turned into beads or drawn into wire or beaten into gold foil. The gold rhino was made by tacking gold foil onto a carved wooden rhino replica. Evidence of gold crucibles has been found at Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe.

The gold bowl made of wood and covered with gold foil found at Mapungubwe

The extent of Mapungubwe’s rule

Huffman writes that Mapungubwe pottery changed in style after its demise and thus the extent of its rule can be traced by its distribution between 1200 – 1300 AD. Much of the territory seems to have extended into the southern part of present-day Zimbabwe with the Mapungubwe-style pottery being found over an area of 30,000 square kilometres.

Internal trade and network

Copper and gold would have been sourced from Botswana, South Africa and Zimbabwe. Salt from the Makgadikgadi pans in Botswana with tin from Rooiberg in South Africa. Excavated pottery sherds show that it was traded from other areas to the south and west of Mapungubwe and demonstrates the extensive trade network around Mapungubwe.

Clay spindle whorls were used to spin cotton grown in the region although the technique of cotton spinning was probably introduced from India. Chinese celadon was excavated at Mapungubwe although locally-produced pottery was more suitable for cooking purposes. The celadon ware was probably trade gifts to the ruler.

Precolonial trade networks from present-day Zimbabwe

Commoners

Archaeologists speculate that agricultural activities were carried out on the floodplains closer to the Limpopo and Shashe rivers and cattle herding carried out further away. All the kraals would have been organised according to the CCP with the rulers living in ritual seclusion at Mapungubwe Hill.

Climate change and Mapungubwe’s demise

Climate data reveals that colder conditions in the Limpopo-Shashe Valley possibly began before 1300 AD and it is possible that the colder weather and flooding outside the usual pattern may have ruined the agricultural system. Around this time Mapungubwe was abandoned and the people moved to the north-west and south.

It is possible that some of the rulers may have moved to Great Zimbabwe, the successor to Mapungubwe. However, pottery-styles show that the two sites were made up of different groups although the two major centres are only 270 kilometres apart.

Mapungubwe Hill itself was never re-occupied.[18]

Mapungubwe was abandoned about 1300 AD in favour of Great Zimbabwe near Masvingo, Zimbabwe

About 50 years later Sotho-Tswana people moved into the Mapungubwe landscape. They were followed by Khami communities who crossed the Limpopo river and populated the region.[19]

According to tradition and Portuguese records, about 1690 the Singo, identified with the Changamire Rozwi, conquered the independent chiefdoms and consolidated the Venda as a single nation for the first time.[20] The Tshivhula dynasty made a marriage alliance with the Singo, but after a disagreement, moved their capital to Mavhambo, and from here chief Machete I (Raletaupe) moved to the Mapungubwe area.

At the time the Birwa, a North Sotho group lived around Leokwe Hill at two settlements on the east and west ends; the west settlement being sited on top of an earlier rainmaking site and was probably occupied by Birwa in the 1820’s and 1830’s. Fortifications with loopholes for guns at Machete’s residence show that they were the subject to Ngwato and Ndebele raids. After the death of Machete II, the chieftaincy vanishes from the oral record.[21] This may be due to climate factors making the Mapungubwe landscape becoming less productive with declining rainfall and the population appears to have declined from around 2,000 to 500-600 with a shifting subsistence population.

Leokwe Hill was probably abandoned in the 1860’s; excavations at a number of sites have revealed blue hexagonal glass beads that were used in the region from 1860-70 and .577/.450 Martini-Henry cartridges manufactured 1884-89.

Farms in the Limpopo area were surveyed in the late 1860’s and Boer farmers began to take them up in the 1870’s although the rinderpest epidemic of 1896-7 decimated the cattle in the whole region and made some destitute so they were forced to sell up and generally stayed on as tenant farmers.

Khami sites in the Mapungubwe area

These Iron-Age people built around 255 settlement sites that have been recorded during foot surveys. Different types of Khami sites have been recorded including:[22]

- Commoner homesteads that contained about 50 people, including 20-30 children with a family head

- Field camps near cultivable land with grain bins, but not inhabited

- Cattle posts with grain bins but not near cultivable lands

- Headman’s residence with a short length of walling

- Hilltop sites with a stonewalled ruler residence. These housed a petty chief and about 350 people

Each of the petty chiefs residences were built to a similar pattern comprising a private audience chamber, a designated space for a messenger and a space for a medicine-maker. However, Huffman notes that there were too many type-5 ruler residences and type-1 commoner homesteads to exist at the same time. Radiocarbon dates and pottery artefacts have revealed there were two phases of occupation. The first occupation dates from 1400 AD and the second from the 1550’s. It is possible there were four type-5 ruler residences (Mzinda’s) around the Limpopo-Shashe confluence at any one time. One in the Tuli block, another in the Maramani area, and two near Mapungubwe with each serving as an administrative centre to allocate land and provide a court for settling disputes between villagers.

The numerous petty chiefs would have been subordinate to a senior chief. The closest senior chief’s residence was believed to have been at Machemma, about 60 km to the south near the Soutpansberg. Excavations at Machemma have revealed a first occupation date of circa 1400 AD and a second one hundred years later. A third occupation around 1600 revealed Venda-style walling and pottery. The Tshivhula dynasty claim their territory once stretched from the Soutpansberg to the Limpopo river and that they left the Mapungubwe area by 1700; a period when climate data reveals that the Limpopo valley was too cold and dry to support agriculture.[23]

Climate and Geology

The Shashe-Limpopo Valley is only 600 metres above sea-level and lies within a rainfall trough. Current rainfall is between 320 – 350 mm per annum; insufficient for traditional millet and sorghum crops.

The Limpopo river has wandered over the Mapungubwe landscape as the climate changed between wet and dry periods causing erosion, sediment transport and the creation of landforms such as floodplains and terraces.

The Limpopo river from Mapungubwe National Park

At the time of Mapungubwe between 1200 – 1300 AD the Limpopo river flowed permanently due to higher rainfall. The Shashe even then was a river of sand with water flowing underneath, but when it flooded it impeded the Limpopo river that would back up for some kilometres. The narrow gorge upstream would increase the backing up effect on the Limpopo river and serious flooding must have been quite a common occurrence.

The Limpopo-Shashe Valley lies between two granite cratons – the Zimbabwe and Kaapvaal cratons to the north and south with sandstones being transported into the region by gradual upstream erosion. Cracks in the earth’s crust allowed basalt and dolerite dykes to intrude into the underlying sandstones. The area is still seismically active.

The confluence of the Limpopo-Shashe rivers

Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre

The Interpretation Centre with its diorama and displays explaining the history and function of Mapungubwe is well laid-out and definitely worth the visit.

Mapungubwe Interpretation Centre

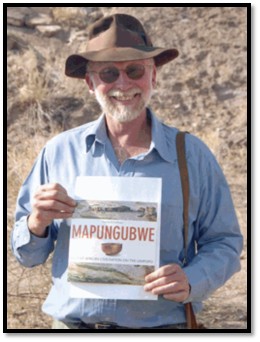

Tom Huffman – a tribute[24]

Thomas (Tom) Niel Huffman was born and educated in the United States graduating in 1966 with a BA Honours degree in anthropology and later obtained his MA (1968) and PhD (1974) in anthropology from the University of Illinois.

In 1967 he excavated with Brian Fagan two sites on the northern edge of the Zambezi escarpment before moving to Bulawayo to work on his doctoral project in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe) He spent two months at the National History Museum of Zimbabwe studying collections and then excavated at the Leopards Kopje site expanding our knowledge of the culture.

His professional career started in the early 1970s with his appointment at the Queen Victoria Museum, Salisbury (present-day Harare) as Chief Scientific Officer, National Museums and Monuments. He served as Inspector of Monuments for the Historical Monuments Commission from 1970 - 72 with duties that included monitoring the Great Zimbabwe site. In 1971 its curator pointed to dhaka structures that had been exposed during construction in the area below the museum. Tom obtained permission to carry out salvage excavations, which he executed over the next five years. These excavations revealed ‘élite’ and ‘commoner’ areas and provided the material building blocks for Tom’s detailed structuralist interpretation of Great Zimbabwe and the site of Mapungubwe that followed

While excavating at Great Zimbabwe, Tom continued the Ranche House tradition of field schools started by Roger Summers and Peter Garlake. Tom had a great talent for entertaining and motivating scholars, students and members of the public into the magic of archaeology.

In 1977 Tom left the Queen Victoria Museum to take up the position of Professor and Head of Archaeology at the University of the Witwatersrand (‘Wits’) in South Africa. For the next 30 years he was the head of a vibrant and productive department. Following his retirement in 2009 he was awarded the title Emeritus Professor.

Amanda Esterhuysen writes that he was always provocative and his ideas sometimes stimulated heated debate; it was common for him to seek the opinion of a very broad social and academic network that included colleagues, anthropologists, linguists, historians, biologists and philosophers. More often than not these animated discussions would take place around Tom’s dinner table. He was the quintessential host and his house was home to visiting scholars, struggling students and anyone who needed a roof or a meal.

In the early 1980’s he was deeply influenced by Adam Kuper’s idea that African homesteads had an underlying regularity in spatial organisation derived from and reflective of their belief systems and by the socio-economic importance of cattle to these societies. From this Tom developed the Central Cattle Pattern (CCP), an historic template that could be applied to identify the presence of Iron Age Eastern Bantu-speaking people in the archaeological record. He later applied a similar ethnographically derived approach to the spatial layout of Mapungubwe and to explaining the emergence of the Zimbabwe Culture pattern.

The CCP and the Zimbabwe Culture Pattern dominated archaeological discourse in southern African Iron Age research throughout the 1980’s and 1990’s but did attract criticism. This remains an essential reference point for studies of pre-colonial farming communities in southern Africa.

Esterhuysen says Huffman’s curiosity and creativity were contagious and he attracted and supported postgraduate students from a wide range of sub-disciplines. Tom had a real passion for fieldwork and his field schools and field trips were legendary, with many young archaeologists learning their trade working alongside him on a salvage or research project.

After South Africa’s national heritage legislation changed in 1999 to include a requirement for environmental impact assessments, Tom set up a contract unit at Wits to cross-subsidise research projects, students and conferences. He personally led many of these surveys or salvage excavations, weaving the material into his interpretative framework. It was also at this time that South Africa began to rewrite its school history curriculum and Tom provided funding and space for the development of an educational archaeology unit. He also produced educational materials on Mapungubwe and, much later, co-authored a book called Palaces in Stone that he was hoping would be recognised for use in the classroom by the Department of Education (Main and Huffman)

After his retirement Tom continued to work in the field and published extensively on a wide range of material, but around 2010 he began to spend part of each year in the United States. He had become reacquainted with Frank Lee Earley, a childhood and university friend from Denver, visiting sites on which they had worked together as undergraduates.

He and Frank Lee Earley began a long-term project on the Middle Ceramic period in southeast Colorado and published a series of articles as well as his penultimate book, Paradigms in Conflict: Cognitive Archaeology on the High Plains.

Tom died on 30 March 2022 in Johannesburg, South Africa.

References

Thomas N. Huffman. Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo. Wits University Press. Johannesburg, 2005. https://archive.org/details/mapungubweancien0000huff/page/6/mode/2up

Thomas N. Huffman. Historical Archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete. Southern African Humanities 24: P33–59 July 2012 KwaZulu-Natal Museum

Peter Robertshaw et al. Southern African glass beads: chemistry, glass sources and patterns of trade.

Journal of Archaeological Science, Volume 37, Issue 8, August 2010, P1898-1912. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0305440310000798

Thomas N. Huffman. Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 28 (2009) P37–54

Notes

[1] Zimbabwe archaeologists believe the original development of Zimbabwe Culture took place at Mapela, a site excavated in south-eastern Zimbabwe, that displays all the same characteristics as Mapungubwe. See the separate article on Mapela under Matabeleland South on this website

[2] Historical Archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete, P35

[3] Over 1,000 glass beads were found at Schroda. Southern African glass beads: chemistry, glass sources and patterns of trade

[4] Leopard’s Kopje refers to the site in Matabeleland where this style of pottery was first identified

[5] Zhizo-style pottery is called Leokwe after the hill near Mapungubwe where it was first found

[6] Not all the Zhizo people left and may have become cattle herders for the K2 people. They originally lived on the south side of Leokwe Hill, but when K2 became established, they moved to the northern side of Leokwe Hill

[7] Leokwe Hill may originally have been a rain making site

[8] Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa, P39

[9] Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo, P23

[10] Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa, P42

[11] Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo, P30

[12] Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa, P44

[13] Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo, P32

[14] Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo, P39

[15] Mapungubwe: Ancient African Civilisation on the Limpopo, P41

[16] Ibid, P42

[17] Ibid, P48

[18] Ibid, P56

[19] Historical Archaeology of the Mapungubwe area

[20] Beach, D.N. 1980. The Shona and Zimbabwe 900–1850. Gwelo [Gweru]: Mambo Press

[21] Historical Archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete.

[22] Historical Archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete.

[23] Holmgren, K., Lee-Thorp, J.A., Cooper, G.R., Lundblad, K., Partridge, T.C., Scott, L., Sithaldeen, R., Talma, A.S. & Tyson, P.D. 2003. Persistent millennial-scale climatic variability over the last 25,000 years in southern Africa. Quaternary Science Reviews 22: 2311–26

[24] This tribute is entirely from Amanda Esterhuysen’s obituary on Tom Huffman