How the Ox-Wagon and transport-rider opened up this country

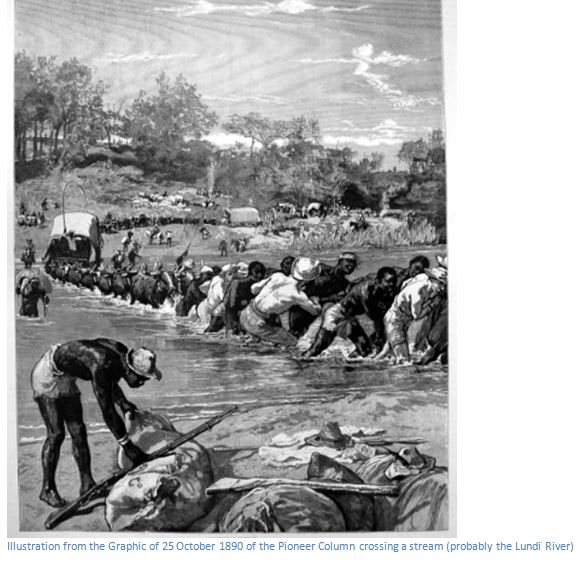

Hans Sauer says the trek ox is the real pioneer of the southern African sub-continent. They dragged the wagons across the whole of South Africa and crossed the Limpopo and Shashe Rivers and then across the Lundi (Runde) to Victoria and finally Salisbury.

Before the coming of the railways it was the trek ox that provided all the transport leading to the development of the diamond fields at Kimberley and the goldfields of the Witwatersrand and finally the occupation of Mashonaland and conquest of Matabeleland.

The trek ox brought from the coast into the interior all the food, furniture, clothing, household utensils, corrugated sheeting, timber, heavy machinery required for mining, the portable steam engines that provided power and permitted the development of the towns at Victoria (Masvingo) Salisbury (Harare) Gwelo (Gweru) and Bulawayo.

To the transport-riders the road had huge appeal. Stanley Hyatt says to him, the road was what the sea is to other born wanderers. He had already sailed around the world in a wind-jammer, but this was nothing in comparison to the dusty, narrow track which ran from the railhead towards the heart of Africa.

To see examples of wagons, visit the excellent Mutare Museum, which specializes in transport, and has some excellent wagons and carts donated by the Strickland family, or see the article under Manicaland Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

So quickly did land transport develop – the railway reaching Bulawayo in 1897 and Salisbury from Beira in 1899 and from Bulawayo in 1902, that the era of the ox wagon and the transport –rider was a short one and their significant part in the opening up of the country is largely forgotten.

Louis Bolze reminds us in the Foreword to The Old Transport Road by Stanley Portal Hyatt that wagons plying the route between the railhead at Vryburg and Bulawayo took two months to complete the 840 kilometre route; in 1895 the Bulawayo Chamber of Commerce reported over 2,000 ox wagons had arrived in Bulawayo and in the same year a passenger on a Zeederberg coach counted over 100 ox wagons between Palapye and Bulawayo.

Stanley Hyatt, born in 1877, felt great pride and affection for his trek oxen, their individual characters and positions in the span, their care and training, the driver skills and resourcefulness called for to keep an ox-wagon on the road, from repairing a broken wheel in the bush, righting a capsized wagon with an 3,600 kilogram load, to looking after a sick ox.

For Hyatt who came to Matabeleland when he was 19 the fascination of the transport road was immense. He says it did not lead to places, to Palapye, to Bulawayo, to the Victoria Falls. It led through them, past them. It went on; it was always going on, into the very heart of the Dark Continent. One year a District would be a blank on the map, a mere name at best; the next year you would find that the road had reached it, had passed through it, and in the new edition of the map there would be scores of names of mountains, rivers and townships even, on that space.

In 1891 the only route from Fort Tuli to Salisbury was along the route cut by the Pioneer Column between July and September of the previous year. In their hurried march during the previous year Dr Hans Sauer says the worst obstacles they left behind were the many foot-high tree stumps as, unlike stone boulders which the wagon wheels climbed over, they produced a dead shock followed by a violent swerve which could result in the dϋsselboom, or wagon pole snapping. When this happened, everyone looked for a suitable shaped tree to replace the broken dϋsselboom which often had to be cut down by starlight.

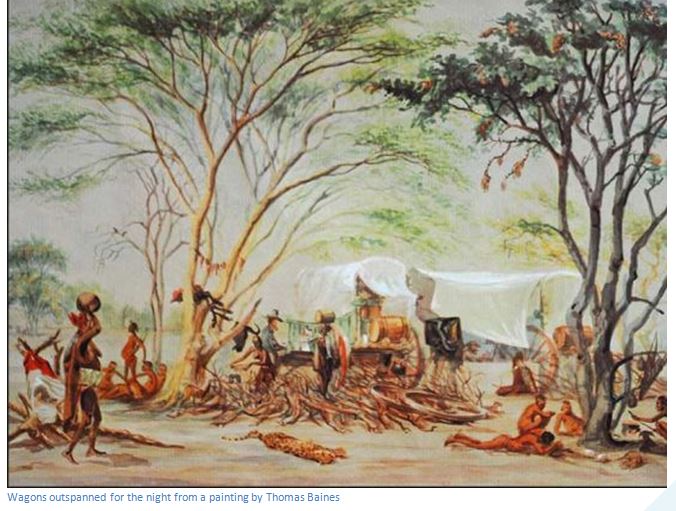

On his journey Sauer followed the routine of the Afrikaner transport riders, which was the tried and tested method for oxen when long distances were being traversed. Two treks were made every 24 hours. The first began about 4pm when the voorloper would crack his whip and bring the oxen back to the wagon for in- spanning. The trek began at 5pm and lasted until 9pm when the oxen were unyoked and tied to the trek chain to lie down and chew the cud. Two or three fires were lit around the camp to scare off lions and for the evening meal. Dry firewood was collected and stacked for use during the night. After supper everyone slept, rising about 2am when the second trek began and ended just after sunrise at 5am.

During the day the oxen were let out to graze with a herder, and the wagon conductor or driver, the voorlooper and other assistants would take long naps, just waking to check on the oxen. All passengers followed their example as it was difficult to sleep whilst the waggons were trekking due to the wheels constantly bumping against boulders and stumps.

The only exception to this routine was in the rainy season when the roads washed out, every rut became a river and scooped out the road into trenches up to three feet deep and travelling by night became dangerous; the Selukwe-Victoria road was notorious for wash-outs.

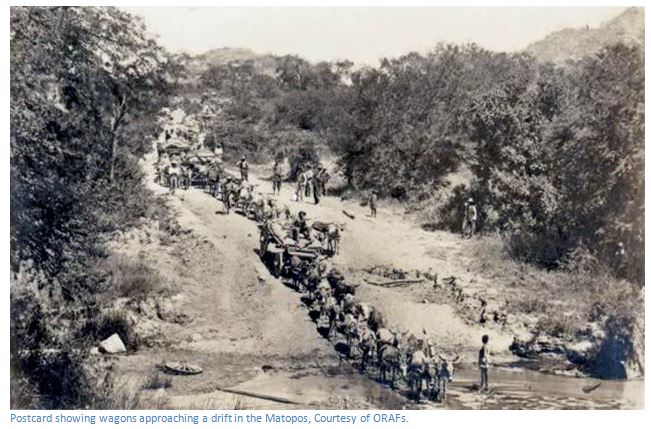

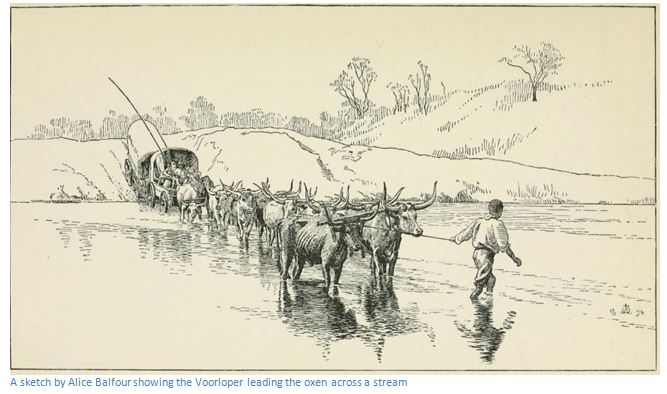

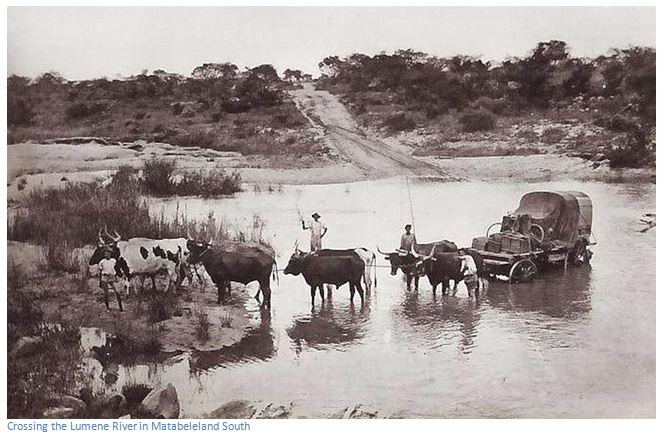

Approaches to drifts across rivers were always taken cautiously especially if the pull-out was steep or narrow, often just a cutting in the river bank. It was always difficult to get the span to begin a heavy pull with a dead-straight chain, they preferred a swing and often at drifts two spans would be used as the wheels would get caught in a wash-out into which they sank.

On flat ground the driver had an easy time sitting on the front box with his helper smoking endless pipes of Boer tobacco. Trekking by night in broken country intersected by dongas and small streams could be very difficult. The driver would be on foot beside the oxen, shouting their individual names and cracking the whip in the air when they were not doing their fair share of pulling, touching an ox with his whip on occasion when it refused to obey an instruction and prodding the wheeler in the ribs with the whip butt end to make him swerve and miss a stump or boulder on the road.

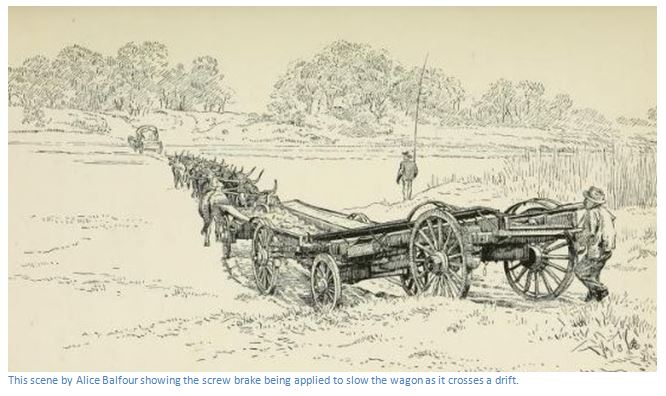

When the voorloper shouted they were approaching a steep stream bank, the driver would rush to the rear of the wagon to screw the brake onto the two rear wheels to prevent the wagon gaining speed and injuring, and even killing the two hind oxen, or wheelers. The constant braking and then loosening the brake when negotiating difficult ground was hard work and a great test of the driver’s ability; demanding strength and stamina and quick thinking. Hans Sauer says he tried it and found seven or eight kilometres of bad road quite exhausting work.

Accidents were common. Lord Randolph Churchill does not mention this happening in his book Men, Mines and Animals in South Africa to one of his ox-wagons when crossing the Lundi River (Runde) on his grand tour of Rhodesia in 1891. The slope leading down to the river was very steep and the driver too slow in applying the brakes so that the wagon rushed down on the team of oxen, killing both wheelers and injuring others. A little later, voorloper was killed by a crocodile, another incident which also goes unmentioned, but is recounted by Hans Sauer, who was crossing the Lundi River at the same time.

Trekking was a noisy affair; the driver shouting out the names of the oxen if he considered they were not pulling their weight. “Englishman” or “Rooinek” was the name usually given to the worst in the span and was an old-standing joke with Boers. Other common names were Bandom, Biffel, Jackalass, Jonkman, Sixpence, Fransman, Witkop, Blom, Appel, Basket, Scotchman, Swartland and Dudmaaker.

Biffel, the left hind bullock of the Stanley Hyatt’s black span was his favourite. Like all true Mashona cattle he was short in the legs and long in the body with a beautiful head, short flat horns and the kindest, wisest eyes. He was fond of strolling up to strangers in the mining camps and would stand still as they scratched his ears, or put an arm around his great neck.

The two hind oxen, achter-os, or wheelers, who steered the wagon, had most work to do in avoiding obstacles in the road and were the most important oxen. They had to push sideways against the dϋsselboom and the pulling strain of the other fourteen oxen in the span. If they were slow in obeying the driver’s orders, they would receive a cut from his whip, causing the ox to swerve violently against the dϋsselboom and his companion to change the direction of the wagon and miss a boulder or stump in the road.

On inclines the wheelers would help brake the wagon by planting their feet in the ground and causing a backward pull on their yoke with the rest of the span being held back whilst the voorloper would also pull back on the “tow” a leather riem attached to the horns of the two leading oxen. In addition, he might shout for them to go slow, even punch the leaders on the nose, or throw handfuls of dirt at the others to make them slow up.

Next in importance to the wheelers were the voor-os or leaders and expected to be a cut above the other oxen. They have to choose and follow the most promising track and not wander into the veld, or lunge at the voorlooper when he unhooked the tow. They act for the rest of the team; for instance if attacked from the front by lion they keep their nerve and gently back up with their heads down and horns pointing out. The worst thing they could do would be to turn around followed by the rest of the team as this would snap the dϋsselboom, or capsize the wagon.

Hans Sauer says near Hartley Hills where he was inspecting old workings with Bob Williams and Edward Maund, their wagon was charged in the early morning by a fully grown male lion. The first he heard was the lion roaring and the shouts of the driver and on getting up saw the lion making short menacing rushes at the lead oxen. The voorloper abandoned the tow and bolted underneath the wagon and refused to return. As the lion rushed forward, the oxen moved quietly backwards until they were hunched around the dϋsselboom and showed no fear, standing stolidly with their heads down and horns pointed up to protect themselves. Sauer fired at the lion, wounding him and he vanished into the long grass.

Stanley Hyatt describes a journey down to Filabusi, where sixteen kilometres short of their destination near the Killarney Mine they stuck fast in the mud and it took five days to move a kilometre. It was a huge grassy vlei, saturated with water from constant rain, and the ox-wagon stuck up to its axles in the black mud. Any attempt to move made the ox-wagon sink deeper whilst the heaving cattle trampled the ground into a pond of black slime and were up to their bellies in thick mud.

The only way out was to unload all their freight onto a “sledge” made from the fork of a large tree and pulled by six oxen onto higher ground on a number of trips; each load being stored under corrugated iron sheets borrowed from the nearby Killarney Mine. Then sixty feet of chain was made fast to the dϋsselboom of the now empty wagon which was pulled out by the entire span.

Hyatt disliked trekking on the highveld between Bulawayo and Gwelo he never shot anything here which meant he never had fresh meat on that road. In the bush country towards Fort Victoria there were trees for firewood and villages to buy milk, pumpkins, sweet potatoes and eggs; also guinea-fowl to shoot. The disadvantage was that the rivers were much bigger and the chances of being held up by them increased. Both Sauer and Hyatt say that it was good practice to cross a river as soon as it was reached, in case it rose in the next few hours.

When they were held up at a river a stick would be driven into the bank at the edge of the flood and left for an hour or two before it was inspected to see if the level had fallen. Hyatt says his spirits would rise and fall with the water. A drop of an inch and you gave the wagon boys extra sugar; a rise of half an inch and you throw your boots at the cook boy. His younger brother Amayas was once compelled by floods to wait six weeks at the Tebekwe River, but as he was so ill with fever, he never noticed the time.

Sauer favoured the red Afrikander, a native of the Cape with long wide spreading horns and the largest of its kind and says a well-selected and matched team of Afrikander’s, with their immense horns, stepping out on a transport road, was a sight not easily forgotten. Stanley Hyatt, with more experience of transport-riding in this country, favoured the local cattle found in Manicaland. They initially bought sixteen young cattle which cost £64 in cash; they all developed into fine beasts and three years later he could have sold them for over £400. They bought many hundreds of cattle over the next three years, but always hung onto their original sixteen.

The conductor, or driver, needs to search out the best places for pasture when they stop in the early morning and find soft ground for the oxen to lie down comfortably tied to their chain at night. He must notice and doctor all wounds and cuts on his oxen, especially on the hoff, or hump, and for this he uses the greased tar used for the axles of the wagon. He will rest his oxen for up to ten days when they look weary and throw over and shoe them with two shoes, or ox cues when their hooves get worn out. He will not allow his oxen to come into contact with any other cattle for fear of them catching lung-sickness or red-water.

Matching the temperaments of oxen was an important matter as pairing an eager ox with a slow one acts as a brake on the span because the eager ox with the slight advance of the yoke-end tends to push his mate back. In the first ten or fourteen days of a trek the driver will constantly change the pairings until he is satisfied they are perfectly paired.

The driver’s whip is made up of a long and hefty bamboo shaft from 3.6 to 4.3 metres in length to which is attached a 6 to 9 metre lash, made out of buffalo, giraffe, hippo or rhino hide trimmed to the thickness of a finger and made very pliable and supple by a process called “braying” or constant rubbing with a greasy hand. The long lash ends in two shorter pieces called the achter-slag and the voor-slag; the latter being at the end of the whip. When a whip is properly handled, the achter-slag and even more the voor-slag inflicts the punishment and produces the rolling and cracking sound which can be heard for miles around. Anything else according to Amous, Hyatt’s Basutu driver, was “fit only for a Zulu, or a thief from Cape Colony.” A good driver never hit his bullocks if he could avoid it. The crack of his whip was sufficient, together with his voice, except when the wagon was badly stuck in a stream or black vlei.

A lot of the driver’s spare time is taken up with keeping trek gear in good condition including the mending and replacing of broken yokes, strops, yoke-skeys and riems. The riem is indispensable, anything broken is bound up, and it serves to tie up the oxen at night, for the tow, catching the oxen at inspan time, for arranging them in yokes and for a hundred other purposes.

The driver must be agile too as he mounts and dismounts whilst the waggon is in motion. To get onto the wagon he puts his foot on the dϋsselboom and pulls himself up with his left hand by catching hold of the side rail. The surface of the dϋsselboom is highly polished by the hind oxen, achter-os, or wheelers rubbing against it. This slippery surface and the constant motion of the wagon have caused many unlucky drivers to slip and fall directly in front of a wagon wheel and be crushed to death.

Stanley Hyatt’s driver was Amous, a little Basutu and very contemptuous of his previous driver, a Zulu schelm called Joseph. He had horse hair plaited into the ends of his moustache to make it appear long and fierce, he was small and slightly built, but as tough as a watch-spring, absolutely tireless and indifferent to danger and hardship and unaffected by wet, cold, hunger, thirst or heat. His costume was always the same; blue dungaree trousers, a tattered canvas shirt and a huge sombrero, known as a “B.P” but according to Hyatt in use and known by this name long before Baden-Powell had been heard of in Africa.

When they met, Amous explained, quite truthfully as it turned out, that he was the best driver in the country. They agreed £3 a month and food; he saluted, borrowed some tobacco and went to inspect the oxen. An hour or two later, Amous returned saying they were “cattle indeed” and set to work to overhaul the wagon and gear, keeping up a running fire of uncomplimentary remarks about the Zulu character. All his thoughts and conversation were about cattle and he constantly lectured the picannin and young cook-boy on the beauties of the “very little oxen indeed.”

Hans Sauer says the trek ox is the most delicate and least resistant to hardship, overwork, cold and bad feeding and soon goes “off-colour.” They do not have a great reserve of endurance or resistance to conditions foreign to their usual habit, but in character an ox is uncomplaining, tolerant and a bit of a stoic. He says he has never known the ox display any affection towards mankind!

Hyatt described in 1896 the Tuli outspan outside Bulawayo, close to the racecourse, as filled with scores of wagons and unbelievably filthy. The perfect breeding place for flies, filled with the litter of empty tins, no trees but plenty of low scrub to hide a sneak-thief; cow dung was used as fuel which half-choked everyone with its acrid smoke. Locals at the outspan comprised a choice collection of rascality and when not forging names to liquor passes would hand around the wagons and steal anything from a bullock to a pair of boots!

He concedes the one good point about Bulawayo is that the streets are so wide that you can turn a full span of bullocks in most of them; otherwise it has no merits whatsoever. The red dust is abominable, choking everything, whilst a single shower of rain changes the dust to slimy red mud!

He says that generally the Bulawayo man could neither ride nor shoot and would have lost his way five kilometres out of town; yet he invariably wore riding-breeches, puttee leggings and a hunting stock and any stranger hearing him talk to a barmaid about his mighty deeds would have taken him to be one of the original Pioneers.

The transport-rider on the other hand, wore dungaree trousers, a flannel shirt open at the neck and a disgraceful sombrero and at his three or four favourite bars around market square liked to be served by a man and to talk about his oxen and the rotten prices the forwarding agents were offering.

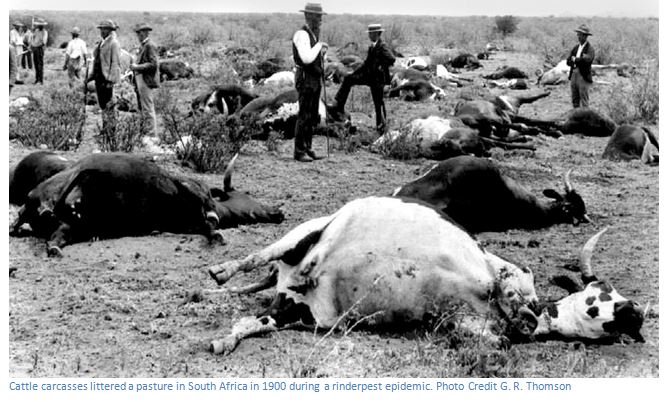

The rinderpest devastated the cattle herds in 1896 when 85-90% of the cattle were wiped out and transport rates rose enormously. Ox-wagons were abandoned in their hundreds; they might cost £80 – £100 at the coast, but in the interior they cost £3 - £4, or Stanley Hyatt says you could just take them and trust to luck not to meet their former owner later on. However from the viewpoint of the transport-rider rates were not extravagant as “salted” cattle (i.e. those that survived the rinderpest) cost £40 each, so a span cost over £640. Transport rates were 25 shillings per 100 pounds weight for a journey of over 320 kilometres along almost inconceivably bad roads, with long dry stretches and the possibility of lions at every outspan. On his first trip to the Geelong Mine this journey took Hyatt over six weeks.

In the last days of the Boer war in 1902 African East Coast fever came to the country. Rinderpest had spared up to 10% of the cattle and those that survived, being salted, increased very much in value. But African East Coast fever spared practically none and was carried by a tick. Hyatt had one bullock spared out of hundreds and their death was a long drawn out agony. Hyatt blamed the British South Africa Company that would not draw a cordon around Umtali (now Mutare) when the disease entered the country. Rhodes had just died and Hyatt thought the news of a new disease would send their share price down. Dr Koch told Hyatt that all cattle born along the coast were infected, and were unaffected unless they moved inland to the highveld. Hyatt believed that Rhodes’ Australian cows were landed at Beira, became infected and out of a thousand, all except three died when they entered Manicaland.

In a few weeks the disease spread throughout the country and the price of cattle fell dramatically killing the transport business. Their black span all died at Selukwe, the red span’s wagons were abandoned, fully loaded, near Tebekwana drift and Hyatt and his brother lost everything. A few weeks before they had been offered £550 for the black span, without the wagon.

This tragedy, which similarly affected all transport-riders throughout the country, combined with the spread of the railway, effectively finished the days of the ox-wagon as a means of transport, except in very out of the way areas. Robin Taylor writes in his article Gweru, a Railway Centre, that asbestos was moved from Shabani (Zvishavane) to the rail head at Selukwe (Shurugwi) a distance of 72 kilometres by ox wagon from 1913. Up to 5,000 oxen were used to pull 400 wagons continuously to move 18,000 tons of asbestos to Selukwe and supplies and machinery to Shabani. This method of transport by ox wagon continued until the railway line, which ran from Somabhula and was built by the Shabani Railway Company, was formally opened by Sir John Chancellor, then Governor of Southern Rhodesia on 11 May 1928.

Acknowledgements

H. Sauer. Ex Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Volume 27 1973

S.P. Hyatt. The Old Transport Road. Books of Rhodesia, Volume 3 1969

R. D. Taylor. Gweru, a Railway Centre. Heritage of Zimbabwe No 20, 2001