Dr James Johnston’s account of a journey across Africa (Part 4 of 5 - From Palapye, formerly Palachwe, to Massi-Kessi, now Manica)

30 March 1892. We reached Palachwe, present-day Palapye, the main town of the Mangwato (referred to today as the Bamangwato (more correctly BagammaNgwato or the BaNgwato or Ngwato) having been four weeks on the road from Leshuma. Having passed many broken wagons, shattered wheels and disselbooms we are happy to have arrived and outspanned in front of Messrs Blackbeard Bros’ trading station. The Bechuana Trading Association has a store under the management of Mr Gifford and there is a hut nearby that is the post office and across the track the telegraph station that is now connected to Salisbury in Mashonaland.

31 March. “I was called this morning to see Khama, his wife, and child (the child died the following day) who were all three down with fever. Not only they, but, as the chief tells me, fully half the natives are stricken with a bad type of malarial fever, which has assumed the form of an epidemic, an average of fifteen succumbing to the disease daily; while I am informed that since the year began, close upon three thousand of Khama’s subjects have been cut off.”

He seemed greatly distressed, imploring Johnston to remain a few weeks and offer what medical aid he could. “The night is made hideous by the gruesome cries of the hyena's as they joined in the carnage among the many dead bodies, but partially interred in the sand of the plain.”

Soshong, their old town, suffered from a water shortage so the population of fifteen thousand moved to Palachwe. The town is made up of villages called ‘staats’ with a small lekhothla in the centre and the land around is unbroken veldt. The fetid, foul air from excrement and refuse hangs around the huts, the bush preventing any free movement of air. There are no sanitary arrangements, the huts are of the poorest construction and at the end of the rainy season are little better than “a reeking dungheap” under which the inhabitants sleep.

The water table is just 90 – 120 cm (3 – 4 feet) down and in many places around are green stagnant pools. Traders and inhabitants have to send wagons with iron tanks some miles away to source domestic water. No surprise then, that fever has taken such a hold on the town.

The watercart, Palachwe (now Palapye)

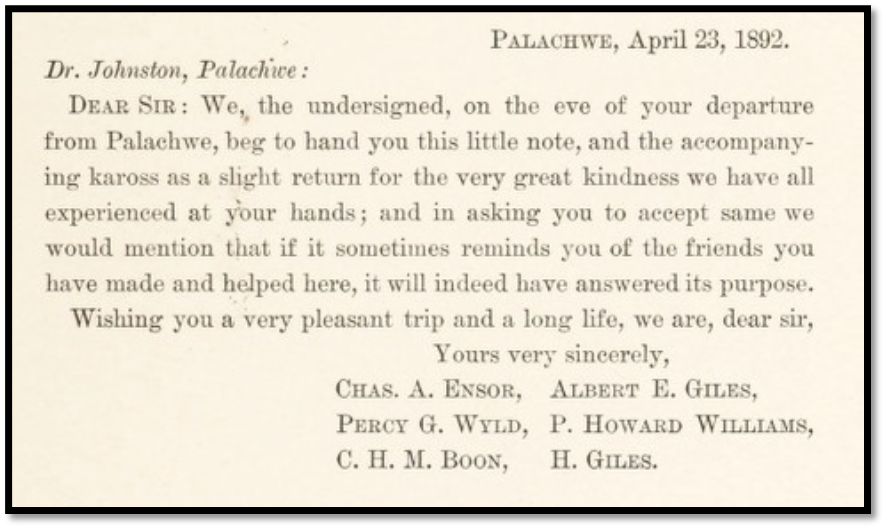

26 April. The chief and white residents are keen for me to stay longer, but I feel weaker every day and have decided to leave by wagon tomorrow. Besides treating chief Khama, I have treated 17 of the 20 Europeans in the town, as well as several Dutchmen passing through. Although none of my patients died, the death rate amongst the natives is very high but with winter approaching things shouldd get better. My patients presented me with the following testimonial:

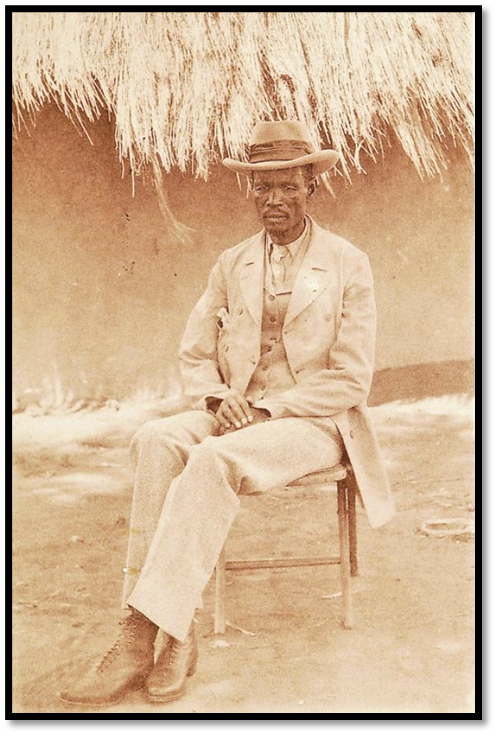

Chief Khama III

Johnston writes: “Khama is a noble example of what Christianity and civilization can do for the African. Both friends and foes acknowledge him to be a straightforward, honest and upright man. Stern and vigorous in administration, he enforces his laws with undeviating firmness and impartiality, particularly in the suppression of the drink traffic. A trader discovered selling drink to a native is forthwith expelled from the country. So extreme are his personal feelings on the subject, that he declined to drink the medicine I prescribed for him during his illness because it was in a bottle but took it readily when sent in a jug. A native who attempts to make beer - so largely consumed in almost every other part of Central Africa - is not only exiled with his family, but has all his lands, cattle and household goods confiscated, excepting cooking-pots and blankets and with no respect of persons, Khama’s own brother-in-law having had to share this fate only a few months ago. In a word, under no pretence whatever are intoxicating liquors supposed to be obtained in Palachwe, not even for medicinal purposes.”

Khama III, Chief of the Bamangwato

Johnston continues: “As usual among such people, the bulk of the hard work falls upon the women. They till the ground, stamp the mealies and act as maids-of-all-work to their husbands and brothers. What we have written concerning slavery in the Barotse applies also to Bamangwato, although perhaps in a milder form. Yet over fifty per cent of Khama’s people are slaves (Makalakas) subject to his orders, his sub-chiefs, or such of the Mangwato as may have permission to appropriate their labour. These Makalakas are the representatives of many tribes conquered and captured in by-gone days, when the Mangwato was a strong and warlike nation. Still, many friends of freedom would be glad to see Khama add to his many virtues and humane laws that of equal rights to all his subjects and place those victims of ‘the accidents of war’ on a footing with the Mangwato and not the abject slaves they are at present.”

Reverend Hepburn[i]

Johnston was upset to learn that because of a dispute between Khama and himself, Hepburn had left for England. He describes the splendid church as near completion, but now at a standstill and likely to remain so until the London Missionary Society send out a replacement missionary.

The Jamaicans leave for Cape Town

Johnston meets the Rev Elliott at Palachwe who promises to take his two Jamaicans, Frater and Jonathan to Cape Town with him. He says that he is sorry to part with them as they have been of great service and of practical help in his journey from Angola.

Trekking to Mashonaland

Mr Ellard, in the employ of Messrs Blackbeard Bros. has volunteered to accompany me some of the way at least so I have laid in a supply of provisions for the road sufficient, I hope, for two of us until we reach Salisbury. Our baggage is on board the wagon, our 18 oxen are ready to be inspanned and we trek tonight.

There was little variety in the scenery; an odd kopje, scrubby thornbush or small mopane trees and a great expense of dry struggling grass constitutes the landscape. The road, however, is fairly good and we lumber along, the drivers bawling out the names of the oxen with threats and exhortations and cracking their long whips. We cover about 4 km (15 miles) a night, one trek from sunset until 9 or 10pm and another from 1am until daylight. There are 800 km (500 miles) of road ahead of us.

2 May. A driver went out and shot a splendid eland antelope, the flesh of which we found delicious and made a good addition to our larder, as with care a hindquarter keeps for a week.

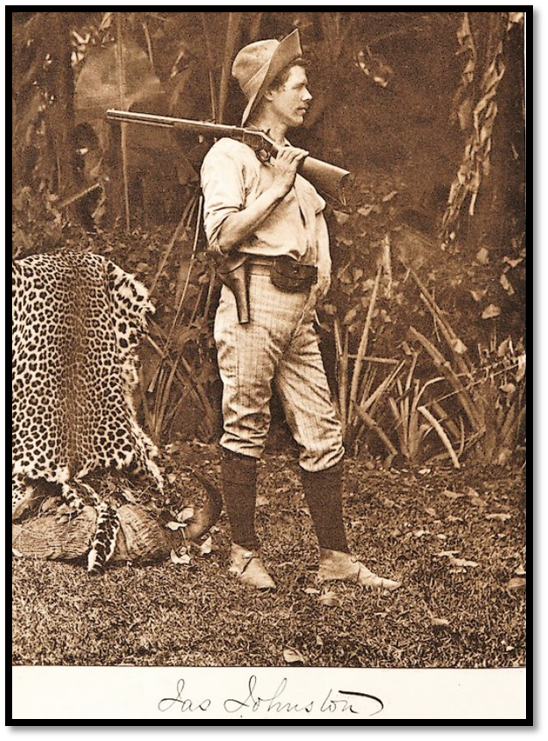

Dr James Johnston – explorer and author

3 May. We reach Macloutsie which is the fort and headquarters camp of the 250 troopers and officers of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) here to enforce British authority in the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The elevation of the district is much higher than Palachwe and healthier, there being but three or four patients in the well appointed hospital at the time of our visit.

In the days beyond Macloutsie the drivers went out and shot a warthog – a horrible looking animal with tusks six inches long. Along this part of the road, wolves [hyenas) and jackals come howling around the camp at night, the fires keep them at bay. The track is rough and extreme, not only from the numerous stones and holes in the way, but what is even worse, stumps of trees varying in height from a few inches to a foot.

8 May. “We outspanned within three miles of Tuli and walked on in the morning to see this mushroom ‘staat’ that has sprung up since Rhodes & Co. began to boom Mashonaland as England’s Eldorado. A small hut at the outskirts surprised us not a little; for the proprietor, besides announcing on a board of many colours fixed to a pole in front of his establishment, that he was a hairdresser and barber, also intimated that in his twelve-feet-square domicile he was prepared to accommodate, for a consideration, hungry and somnolent wayfarers with refreshment and beds.

I found the artist - an ex-policeman - busy with a very refractory subject, a prospector, maudlin drunk. Talk he would, while being shaved, in spite of the barber’s expostulations. As a second party in a like condition sat awaiting his turn, we proposed taking a stroll. Intoxicated white men seemed the order of the day; we met them at every turn, although they have to pay twenty-five shillings per bottle for brandy and five shillings per bottle for ale. Tuli is situated on the south bank of the river Shashe and boasts of a small hotel and half a dozen trading stores, built mostly of wood and corrugated iron. There, besides, two stores belonging to the British South Africa Company filled with great quantities of wheatmeal, while in the open air are stacked some 700 bags of mealies; but evidently, the administration of the commissariat department of the company is rather defective, as there is not a single bag of either commodity fit for food. The shameful waste of grain has not been confined to Tuli however, the same company hoarded 1 000 bags of mealies during 1890 at Alibi, until they had to be thrown away on the veldt and nearly the same quantity was disposed of in a similar manner at Macloutsie. The over-sanguine purchasers probably intended to lay in a supply for the hundreds of horses, which though brought up from the Cape Colony, refused to live in such a climate.[ii]

In the centre of the town, on a small kopje, a fortification has been constructed and is garrisoned by some five policemen, every white man in the district being under pledge to aid in holding the fort in event of an attack from the Matabele, their most formidable enemy. Having obtained permission of the captain,[iii] I proceeded to do some photography from the fort, but was warned not to climb over the breastwork, as the sandbags would not permit to be walked upon.”

Whilst doing this Johnston was overcome by dizziness, probably a relapse of malaria fever, and was forced to lie down in the shade of a shelter for a few hours, helpless as if paralyzed. “But a cup of tea revived me a bit and the wagons having come up early in the afternoon, so as to get across the 500 yards of sandy riverbed of the Shashe during daylight, I walked on after them.”

When about to get on the wagon for the purpose of reaching the other side, a policeman rode up demanding to see our passport or license to enter Mashonaland . We made some observations in reference to our possessing a Portuguese passport through their country as a foreigner but thought it rather extraordinary that a British subject should require a permit to pass through (so-called) British territory. ‘Can’t help that, sir; my orders are to stop every white man from passing through Tuli unless he can show a prospector’s license.’

In vain were our protests that we were not ‘prospectors’ nor would we know the difference between reef quartz and alluvial gold if we saw it. A policeman on duty is not open to reason and though feeling very ill, we had no alternative but to march back to a small mud hut, where a minion of the law duly registered us as prospectors and on payment of a small fee handed us strips of paper to that effect. It was now getting late and we hurried back to join our wagon. To cross the river-bed was no light work, the wheels sinking to the hubs in the wet sand and requiring double spans of oxen to pull it through; but it was accomplished without any mishap and having trekked seven miles more, we tied up.

We crossed the Umpagi (Ipagee) on the 10th and are now in the Banyai country. The roads are still very rough, being cut up every few yards by spruits and sluits from a few feet to several yards in depth, requiring the frequent application of the brakes to prevent the wagon from crushing the oxen as it plunges into the ravine.

The Banyai natives are refugees from various tribes and have their kraals among the fastnesses of the hills, where they have been driven through fear of the Matabele. Like the Mashonas, they are very poor, having been similarly plundered of almost everything they possessed by the raiding warriors of Lobengula, who not only seize their cattle, but take captive and enslave their women and children, assegaing their men. The dress of the women consists chiefly of large coils of beads round the waist and ankles. They shave their heads with the exception of a round spot on the crown about three inches in diameter and over all, of course, grease. The men, as usual, are more simple in their attire, contented with the regulation small tab of wild cat skin fore and aft.

Four more days saw us outspanned by the Bubi (present-day Bubye) river, surrounded by numerous grand kopjes rising abruptly from the plain, some of them to the height of eight hundred to a thousand feet, bare and bald, seemingly one solid block of granite, closely resembling those we first saw in the Cisangi country west of Bihe [Angola] While out hunting, the drivers encountered a lion, but there is no exciting story to tell of the adventure, for with commendable discretion they sought refuge in the camp. Two days ago four lions attacked the oxen of a transport rider, killing several; but thus far we have escaped them.

Next day we halted at Matibi’s kraal, and bartered for some vegetables with salt, gun-caps, and matches. I climbed an adjoining kopje for the purpose of taking photos and found quite a village near the top composed of poor little huts built in the nooks and crevices of the rocks; having no soil in which to fix the upright sticks, the foundations were strengthened by layers of mud.

The following day we crossed the Gandon [Nuanetsi, present-day Mwenezi) river. There is a small whisky shop here, run by white men nominally for the convenience of travellers and one of many that have been opened between Tuli, Salisbury and Umtali (present-day Mutare) since the British took possession and generally situated as nearest possible to the regular outspanning places. The Salisbury correspondent of the Cape Argus Weekly on 6 April 1892 writes. “The following list will be interesting to many and also useful to those intending to trek to Mashonaland.” Wayside places on main road, Tuli - Salisbury.

From Tuli | ||

Mpagie's [usually Ipagee] | 15 miles Campbell & Drummond | Campbell and Drummond |

Umzingwani | 35 | Hinds & Firman |

M'Gobie's | 80 | Withers |

M'Tibi's | 92 | Drummond |

" | 106 | Dillon & Perkins |

Nuanetsi | 122 | Sanderson |

Lundi | 155 | Grant |

Tokwe | 182 | Saunders & Prinsloo |

Fern Spruit | 194 | Bowden |

Fort Victoria | 204 | various hotels and stores |

U'Mare's | 234 | |

Inyazitza | Werrit & Young | |

Fort Charter | Dunn | |

Umfuli | ||

Six Mile Spruit | Mashonaland Auctioneering Co. | |

Wells & Foote." | ||

From Salisbury | ||

16 | Duncan and Kerr | |

32 | Graham and White | |

Marandella's, Bottomley | Head and Moore | |

M'Chiki's | 78 | Lewis |

Laurencedale | ||

Lesapi Drift | 108 | Reid Bros |

130 | Bates and Watson | |

Odzi | 150 | Holberg |

They are of but little benefit to a hungry man, as we have inquired in vain for bread at every one we passed. This, with the fact that out of a hundred wagons now on the road to Salisbury, seventy carry an average of two thousand bottles of intoxicating liquor each, is not much to the credit of Europeans, nor to the company under whose patronage it is admitted. It is the unanimous opinion of those we have met that whisky dealers will get their fingers burned this time, for there is neither money to buy, nor people to drink a tithe[iv] of the stuff that is pouring into Salisbury.

This rush is owing to the scarcity of liquor and provisions last year. The rivers being full, wagons were detained on the road until whisky brought £30 per case; champagne £5 per bottle; Boer meal £12 10s per bag and one-pound tins of provisions 10s each. The times have changed materially since then. Many of the mining claims have not turned out to be such bonanzas as was expected; four syndicates have smashed up, dismissed their men and abandoned in disgust the fields that refuse to yield sufficient of the precious metal to pay working expenses, while almost every day we meet bands of disappointed prospectors returning down country, poorer men then when they passed up full of hope a year or so ago. One graphically described things in general by remarking: “It ain't no country for the white men anyhow, even if gold is there, where to live he has to be a-eatin’ of quinine all day long.”

We could not but sympathise with one young fellow, whose health seemed completely shattered and who but eighteen months before had gone up in company with two brothers, but now returns alone, both the brothers having died of fever after sinking their all, some £1 ,500 pounds in a fruitless search for “the wealth of Mashonaland.”

19 May. We crossed the Lundi (present day Runde) river on the morning of the 19th - a tough bit of work, taking two spans of thirty-six oxen, pulling their hardest, to get the wagon through. The river, though low, had a good stream running. During the rainy season, the Lundi rises very high and owing to the rapidity of the current becomes impossible for transport wagons, many being delayed on the bank for months at a time. Then fever, aided by the canteen close by, gets in its deadly work. There were no fewer than fifty-seven white men's graves, mostly on the south side, made during the last wet season.

Crossing the Lundi river

We are now in Mashonaland. The landscape grows more hilly and rugged as we move northward, while the same smooth-faced, rocky kopjes predominate here as we noticed further South. The vegetation on the plains is richer, the trees larger and the scenery in general much more interesting, but there are no signs of cultivation anywhere and the few natives who come out to trade seem to set great store by their meagre stock of garden products. One brings half a pound of mealies in a basket, little larger than a coffee cup, while another swings in his hand one small, sweet potato and for which they each ask a shilling or a yard of limbo but go away satisfied toward evening with a tablespoon of salt.

We have travelled twenty-three days without seeing a native village, with the exception of the kraal at Matibi’s. Through the Naqua (Naka) Pass the high, rocky bluffs on each side present quite an Alpine appearance. Emerging into the open country, we outspanned and were entertained the whole day by a concert of unearthly whoops and yells issuing from a glen where a Mashona kraal lay hid. A big beer-drink was evidently on hand. We continued our journey the same night through ‘Providential Pass’ where the Pioneer Column was so agreeably disappointed in not being attacked by Lobengula’s warriors, hence the name.[v]

22 May. We reached the Toquani (Tokwe) river, another hard river to cross. Last year at this place three prospectors on their way to Salisbury had a melancholy experience. The eldest of the party having been gored by an ox, one of his companions boldly ventured to cross the swollen river on horseback to call medical aid from Victoria. He had reached the centre of the stream, when a crocodile seized him by the leg, mangling it fearfully and dragged him down to some reeds where he lay in a helpless condition all night, doing his best to keep the monster at bay with his revolver. At daybreak his moans brought friends to his assistance, who carried him to Victoria. But it was too late; gangrene had already set in. He succumbed next day and was laid to rest by the side of a young Englishman who fever and hunger had cut off a few days previously (kind-hearted countrymen had planted a few flowers on the graves and erected a palisade of sticks to protect them from the hyenas) while the comrade for whose sake he had attempted to ford the river died by the wayside.

24 May. We reached Victoria and outspanned at the new township. I walked back to the fort, about four miles, for the purpose of picking up carriers to carry my photo apparatus, blankets and some provisions and started about noon to visit the Zimbabwe ruins, 24 km (15 miles) southeast. By sundown we were busy cooking our supper in an open space near these marvellous memorials of a great, but long defunct people. The night was bitterly cold for a bed on the bare earth and we had only enough firewood to last a couple of hours, so we hailed with relief the first streak of day and got astir stiff and cramped. With dry grass we made up sufficient fire to prepare a cup of hot tea which had a wonderful effect in reviving our spirits.

We visit Zimbabwe ruins

I then set about seeking points of vantage for the tripod, but found it impossible, even with a wide angle lens, to get the curious tower within the rotunda.[vi] Its position is much confined by high trees and broken walls, while the long grass and weeds would require half a dozen men clearing up for days before the camera could be brought to bear successfully on much that is most interesting among these grand relics of a people whose identity so far is a matter of speculation. After taking a view of the rotunda from the north east, we gathered our traps and climbed to the top of the kopje where the remains of the ancient fort are to be found.[vii]

Here again we were foiled in the attempt to get pictures, everywhere the summit of the southeast portion has been built upon and so closely that one can only walk in and out among the narrow passages and small rooms, but nowhere could we find sufficient distance to focus upon more than a few feet of wall at a time. Why these Phoenicians, Arabians, or whoever they may have been,[viii] should have crowded themselves and their stronghold into such a limited space is explained when in walking around to the north side we find the only entrance is through a crevice between two huge rocks, so small as to admit of but one person at a time; while the boulders present a perpendicular front about forty feet high uniting with others of the same character to form a wall across the kopje almost as impregnable to modern weapons as it must have been to those of ancient warfare. Access from any other direction is impossible on account of the high, smooth-faced, rocky cliff of 27 metres (90 feet) on the opposite side, which in several places has been supplemented by the addition of walls from 4.6 – 6 metres (15 - 20 feet) in height and built so as to form a continuation of the precipice.

Clearly Johnston was influenced by Theodore Bent’s book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland from which he quotes at length and is not repeated here.

Exterior wall of the Great Enclosure

By 11am I had finished my work and delighted with our visit to Zimbabwe we set out for the wagons, but on coming to a brook we remembered that we had omitted breakfast. We stopped and boiled water in our ‘billy’ threw in some tea and this served to wash down the bit of bread we had saved for this repast. This done, we were off once more.

The extremes of temperature are so great at this (winter) season of the year that it is hard to tell whether we suffer most from the cold during the night or the sweltering heat of the day. We have no time to delay thinking of it, however, as we do not wish to keep the wagons waiting; we generally like to trek about sundown. By four o’clock we had covered the fifteen miles to Victoria, of which place there is little to say, except that there are several temporarily built stores and a few police of the British South African Company.

But why so few are there, no one knows.[ix] A foolhardy confidence is placed by the company in the professed friendship and pacific attitude of Lobengula toward the English; but those who best know the crafty old chief of the Matabele declare that an attack on the Europeans is inevitable and that at no distant date.[x] For, even now, although Loben is receiving a pension of one hundred pounds a month in gold, his younger braves are fretting like sleuth-hounds in the leash for liberty to - as they say - wipe out the white invaders of their country. A fort[xi] has been constructed with a broken-backed provision - shed in the centre and a trench and breastwork that would be no formidable barrier to the advance of a company of schoolboys, not to speak of a charge of Zulus.

Four miles more and we reach the wagons, rather footsore and a bit hungry. The oxen are being driven up as we get into camp. An hour more and we are on the trek again, travelling slowly on account of the deep sand, grass fires sweeping through the scraggy bush for miles on either side. Two days of this and we find ourselves on a great desert plain where we look in every direction for some sign of life on this vast stretch of sunburnt earth - in vain. We cannot even obtain wood enough to cook our food, having to collect dry ox-dung for this purpose, little thinking that this was to continue, with the exception of one or two narrow belts of thorn-bush and ‘wait-a-bit’ for nearly a hundred miles.[xii]

Fort Victoria to Inyamacambe[xiii]

5 June. We passed fort Charter on the night of 5 June. [This website has an article on Fort Charter under Midlands province] This is the place where the Company’s Pioneer Column endured the greatest hardships through the mismanagement of the commissariat department, the men suffering with hunger with only an occasional pannikin of mealies to appease it, while seventy per cent were without boots and clothed in rags, at the same time working their hardest, building the fort and getting the numerous wagons, machines and guns through the mud.[xiv] And all for what?

The fort is situated on a slight rise on the dreary plain, the only outlook being a vast expanse of white sand. I found two solitary white men in charge. One was running a ‘gin-mill’ in the magazine but intending to close up in a week or two as travellers are too few to make it pay, the main road being lately diverted through another district. The other is the telegraph operator who is in danger of forgetting the Morse alphabet for want of practise.

10 June. We outspanned at ‘Six Miles Spruit.’ The large native kraal in the vicinity turned out to be completely deserted, the natives having fled in terror from the outrages committed upon them by white policemen. The cooking pots, calabashes and baskets of the Mashonas scattered around the huts were suggestive of hasty flight. I walked through among the silent dwellings and found in one the decomposed corpse of a woman, apparently about 25 years of age. The whole scene was sad and sickening in the extreme.

Arrival at Salisbury

By 8:30am they are on the outskirts of Salisbury and in searching for a place to stay Johnston is offered a hut by a German resident of the town.[xv] He writes: “The business shanties are built along the base of an isolated kopje, forming one long street, while on the opposite side of the valley and about a mile distant are situated the official huts belonging to various departments of the government, the military camp and the public hospital. At present there seems to be stagnation in every line of business in Salisbury. Miners are discouraged over the 50% of their ‘finds’ being claimed by the company and are leaving for pastures new, while there are but few coming in to take their places. [This website has an article The British South Africa Company and the impact of early gold mining regulations on smallworkers under Midland Province] Large consignments of liquor and provisions are being piled up at the doors of the traders, until they have now more than sufficient to supply the needs of the small community for several years to come.

Bankruptcy is the order of the day. Sales by auction are held twice a week where goods are sacrificed at less than the original cost in the colony so as to realise sufficient to meet present demands. All this has caused a deplorable reaction and those who have extolled ‘the inconceivable wealth of Mashonaland’ as ‘impossible to exaggerate’ are in worse than bad odour with the unfortunate inhabitants. Every other night, indignation meetings are held.”

He continues that agricultural prospects are poor and that farmers who have been persuaded to settle have been duped. “We have talked with several white men who have put the matter to the test during the past two years with results almost nil” and concludes: “far from Mashonaland being even a fair average country for farming, none but those who have ‘an axe to grind’ in booming it will speak of it other than as a failure for such purposes.”

On mining prospects he writes: “That there is gold in the country there can be no question and for those who are willing to risk their lives in an insalubrious clime to find it there is no doubt a future of some promise, but as for ought else, it is but another South Sea bubble.”

14 June. He writes: “Accompanied by Dr Rand (to meet with whom so unexpectedly here was a mutual joy, having known each other years ago in Jamaica) I returned to Six-Mile Spruit for the purpose of taking some photos of the village, to find nothing but a mass of blackened ruins. We draw our own conclusions from this and regret having prematurely spoken of discovering the body of a woman in one of the huts as interested parties have undoubtedly got wind of this, hence the evident incendiary. Special care has being taken to see that the burning of the hut with the body was done thoroughly. That it was not the result of a bush fire was manifest from the fact that the grass was several yards round the hut was unscathed. On removing the debris and exposing the remains of the woman, however, Dr Rand found the bones in sufficient form to enable him to corroborate my statements.”

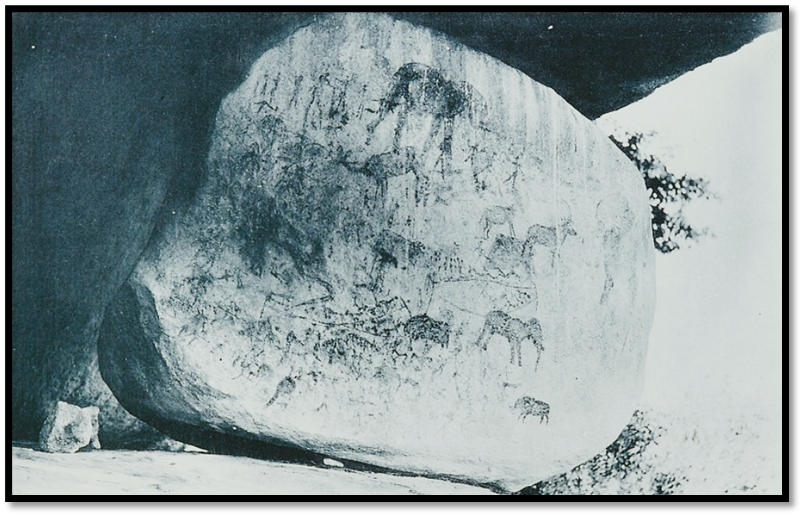

San Rock art

While rambling in the bush a short distance from this place, Dr Rand drew my attention to an overhanging rock under which was a large stone, its flat surface literally covered with bushman’s drawings, very ancient and interesting. The artists as a people have long since disappeared from Mashonaland, although specimens of their work are to be found in many districts, particularly in the Mazoe Valley. They represent generally, wild animals and all sorts of game, battle scenes, etc. and are done in coloured pigments, red, black and yellow predominating. On close inspection the pigments appear to have eaten into the rock, hence their preservation. [These are undoubtably the ‘Bridge Paintings’ at Glen Norah East; National Monument No 142 and are described on this website in the article Rock Art at Glen Norah East and West under Harare]

Bushmen’s drawings

One evening Johnston gave a lecture in the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel at the invitation of Rev Isaac Shimmin on his journey from the West Coast and Barotse Valley and he says: “and probably never again shall I have the opportunity of addressing an audience so entirely composed of those who could best appreciate an account of the trials, privations and dangers incident to African travel, every individual man being in the position to sympathise more or less from actual experience.”

Onward journey

Two ways are open to us: by Tete to Blantyre and Nyasa, or via Umtali and Sena and up the Shire river. We have tried our best backed by the influence of Mr Doyle, the interpreter and others, to get carriers for the first route but no money will tempt them to go.

19 June. They leave Salisbury going via Umtali (present-day Mutare) and Manicaland. “The road gets more diversified the nearer we approach Manica. Some of the gorges and canyons are very fine and the rocky kopjes present most fantastic and peculiar features. At a distance the rugged peaks appear like ruins of ancient castles or monasteries so familiar to tourists in Italy.” [This article contrasts very negatively with Major Arthur G. Leonard's journey by foot from Salisbury (now Harare) to Beira in October 1891 under Manicaland province]

Once more we see the extent of Johnston’s distaste for anything to do with the Chartered Company: “when about three treks from Salisbury, a circumstance came under my notice that confirmed in a great measure reports I had heard of the doings of some of the British South African Company’s police. A certain captain with three men, who had been sent to arbitrate some matters with the natives in the Mutasa district, were returning to headquarters when they overtook on the road four Mashonas driving two small oxen. On seeing policemen approach, of whom they had heard enough to make them dread a closer acquaintance, they of course, ran off into the bush. Whereupon, according to the captain, who was my informant, the police put spurs to their horses, rode down one man, whom they tied up on the spot and began firing on the others with their Martini’s.

Walking some distance in advance of the wagon, I found at a wayside hut this noble band of Englishmen, who seemed to think they were doing valiant service for their Queen and country by attacking four harmless and defenceless natives on the public road. The night was very cold, but there outside sat the Mashona, secured by an ox riem tied round his waist, while inside was the captain, swearing roundly at his men for their bad shooting, who in turn excused themselves on the ground that it was dark.

I could not make out why he wanted to murder the natives and asked for an explanation. “Why,” he replied, “they were about no good, or they would not have run away when they saw us coming. Bring in the fellow, interpreter and ask him what the ---- made him run.” “Great chief, I was frightened.” Where were you going?” Going to my kraal. ”Where did you get the two oxen?” I don’t know where they came from. I only overtook the boys who were driving them a short time before we saw you coming. But I believe the cattle had strayed and were being brought back to their owner, the chief of ---- kraal.” “Take the fellow outside and tie him up till morning when we’ll see about it; meantime, let me have a glass of whisky.”

30 June. Umtali is reached and they learned a road has been cut as far as Massi-Kessi (Macequece, present-day Manica) and decide to put off hiring carriers until they get there. “We stayed only one night in this village which differs but little from such places as Macloutsie or Fort Victoria. It is situated at the base of a large kopje and consists of some two dozen wattle and daub huts, every third one devoted to the sale of drink.” [See the article on this website Old Umtali – the second site under Manicaland province]

1 July. The evening saw them trekking towards Massi-Kessi. “For the first two treks the road was fairly good as we were mostly on the grassy plains; but the balance of the way was simply execrable, the trees having been very carelessly cut down leaving stumps two feet high. Every five hundred yards there are ravines from thirty to fifty feet deep with sides so abrupt that though the brakes were screwed home until the wheels stood still, the wagon would plunge forward with a rush shrouded in a cloud of dust at a speed that threatened to crush the oxen and end in a general smash-up and giving rise to the fear that we should soon have nothing but the pieces to collect of both oxen and wagon. The next four miles was over rough veldt among great rocks and sluits where no attempt had been made to prepare the way for wagons. We succeeded in reaching Massi-Kessi safely on the morning of the 4th. [The road winds its way over what was called ‘the Divide’ and was the route Cecil Rhodes used when he came from Beira – see the article Penhalonga under Manicaland province]

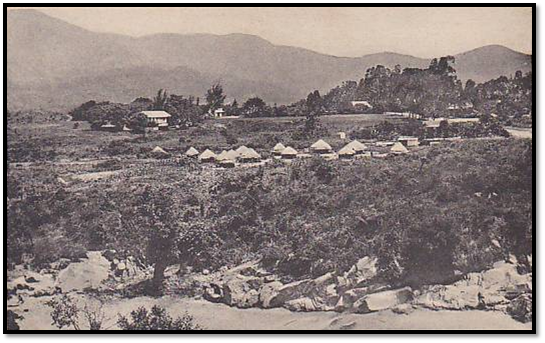

Massi-Kessi or Macequece (present-day Manica) about 1900

At Massi-Kessi they meet Captain Andrada and Commandant Bettencourt. [Both feature prominently in the article on this website How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland province] Officers of the Boundary Commission are based at Massi-Kessi surveying the border that still exists between Zimbabwe and Mozambique, he says there presence handicaps him as the Boundary Commission are employing all the available carriers.

Johnston dines one evening with the Commandant and found him very hospitable and visits the fort at Massi-Kessi which is the local headquarters of the Companhia de Mozambique. He clearly believes 70 years of prior occupation of the site gives the Portuguese sovereign rights over Manicaland and is indignant of the British South Africa Company Police victory over the Portuguese at the battle of Chua Hill.

The Portuguese Captain who is part of the Boundary Commission readily agreed to release some of his carriers to Johnston and even better, some are from Gorongoza through which area they must pass. For the three weeks journey to Sena they will each receive thirty shillings in gold and their food.

[i] James Davidson Hepburn (1840-1893) was converted in his mid-twenties and volunteered to serve the London Missionary Service which trained him and sent him to South Africa in 1870 immediately after his marriage and ordination. Initially he worked at the Ngwato capital, Shoshong, assisting John Mackenzie until the latter went to Kuruman, Griqualand, in 1876. Hepburn stayed on with his growing family, becoming a close friend of the Ngwato chief Khama III, who had come to power in 1875. Hepburn moved with Khama to the new capital of Palachwe (now Palapye) in 1889, but by this time relations between them were breaking down. Khama saw his role as that of leader of his people and of the church among his people. Angry at having his authority as church leader challenged, Hepburn left for London in 1891, the year before Johnston arrived.

[ii] The senior commissariat officer responsible was Tye, who appears to have got the job because he was a pal of Rutherfoord Harris, the BSA Co secretary at Kimberley. Major Leonard, makes many uncomplimentary mentions of him in his book How we made Rhodesia, including “Tye’s presence, so far, has made no appreciable difference in our commissariat and transport supply, which are still woefully deficient…”(P.113)

[iii] Major AG Leonard had commanded E Troop at Fort Tuli until 20 September 1891 when he was succeeded by Lieutenant the Honourable C.J. White who on 1 January 1895 was appointed Chief Commissioner of Police

[iv] 10%

[v] The author is incorrect here. Providential Pass is only reached after the Tokwe river has been crossed.

[vi] The conical tower inside the Great Enclosure

[vii] The Hill Complex, formerly Acropolis

[viii] Now all discredited by archaeology as the possible builders of Great Zimbabwe

[ix] Most of the British South Africa Company police were laid off because of a cashflow shortage. Marshall Hole at the time, Dr Jameson’s secretary writes the following In Old Rhodesian Days: “The companies funds were running low and hardly any revenue was to be expected for months to come. The most ruinous item of expenditure was the cost, amounting to about £150,000 a year for the police force which the Imperial authorities required the company to maintain as a safeguard against attacks from the natives. Rhodes and Jameson put their heads together to devise some means of ridding themselves of this white elephant.”

[x] In fact the ‘big raid’ from the amaNdebele on the Mashona came in July 1893 around Victoria. See the article Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident’ on this website under Masvingo

[xi] The original fort built by C Troop of the British South Africa Company Police now 6km south of Victoria (present-day Masvingo) on Clipsham Farm, National Monument No 123 – now destroyed

[xii] Many travellers, including Randolph Churchill complained that this sandy stretch to Fort Charter taxed their oxen, was cold and windy and dreary travelling

[xiii] Inyamacambe is between Gorongoza and Sena in Mozambique

[xiv] The ground is sandy rather than muddy; also it was early September and therefore in the dry season

[xv] Johnston writes that the site of Salisbury was reached in 1892. This is clearly a misprint as the site was reached on 12 September and the Union flag raised the next day