The build-up to the 1893 Matabele War

This article forms one of a series of six articles covering the 1893 Matabele War. It begins with Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident’ and then The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’ [both articles are under Masvingo province] that lead onto this article. The series then goes onto Iron Mine Hill (Ntabasinsimbe) and the first casualty of the 1893 Matabele War [under Midlands province] before concluding with Battle of Shangani (called Bonko by the amaNdebele) and Battle of Bembesi (called Egodade by the amaNdebele) under Matabeleland South province. All six articles are on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The bulk of the information below is from the Stafford Glass book, The Matabele War.

Ground already covered in previous articles

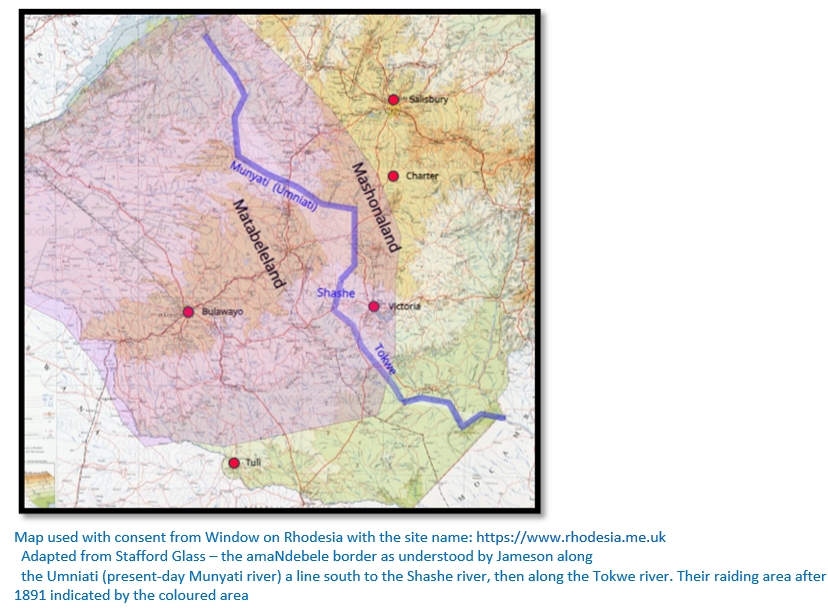

Jameson’s policy towards Lobengula and the amaNdebele including the ‘border’ and his ‘peaceful policy’ have already been discussed in the previous articles but is worth restating.

By December 1891 the British South Africa Company (BSA Co) had extended its gold and mineral rights to be found within the territories claimed by Lobengula within Mashonaland with the acquisition of the Lippert Concession that gave the BSACo the power to lay out towns and farms [See the article Land and the British South Africa Company - the Renny-Tailyour and Lippert concessions under Harare]

The problem was that Lobengula had in no way abandoned his rights over Mashonaland nor had he relinquished his power over the property and lives over the Mashona people.[i]

Around the same time James Dawson had brought messages from Lobengula objecting to European prospectors moving too far west of the Umfuli (present-day Mupfure river) and from then on prospectors, traders or hunters who were molested or robbed by the amaNdebele west of the Umfuli received little sympathy from the BSA Co.

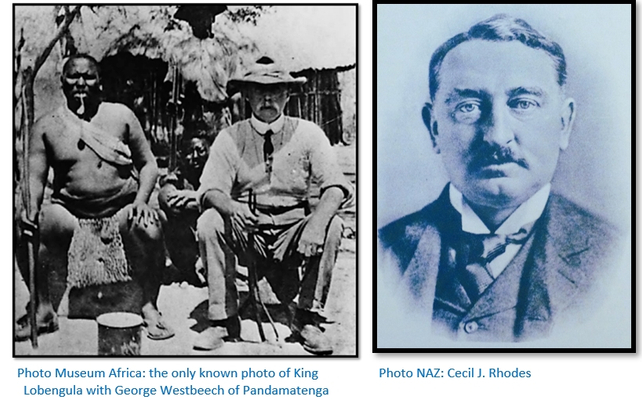

Jameson wrote to Colenbrander, the BSA Co's representative in Matabeleland: “Please tell the king that all the white people in Mashonaland have strict orders not to enter his country…I quite agree with the king that these unauthorised individuals proceeding into his country may lead to trouble between his people and ours, just as I have already explained to the king, that bodies of his people crossing into Mashonaland might get into trouble…my police and magistrates in each district have strict orders to prevent any white people going beyond our recognised line.” And he added: “I'm determined not to have trouble between the King’s people and ourselves through the recklessness of individuals and they should be punished in each case.”[ii]

This is discussed in detail in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident.’ Galbraith writes that Jameson believed that although Lobengula did not explicitly agree to ‘the border’ as shown above, he did accept it as a de facto divide between Mashonaland / Matabeleland.[iii] However in reality it appears that Lobengula’s understanding was that it represented a border for settler gold prospecting, but not for amaNdebele raiding of the Mashona. His belief was that the BSA Co’s powers extended over settler’s only and did not extend over the Mashona.

In June 1893 Jameson appears to still believe in the border as he complained to Colenbrander that Chilimansi’s people, living across the Shashe river 65 km northwest of Victoria: “as the kraal of this chief is situated about 25 miles beyond the border agreed upon between the King and myself, I wish the King to take steps to prevent the constant thefts which are going on by that kraal…Tell the King that my white police had been told not to go beyond the stipulated boundary, in order that he may take steps himself. If not, in order to prevent a recurrence of such things, I shall be compelled to send the police and give this chief and his kraal a severe lesson.”[iv]

Attitudes towards the Mashona people

(1) Lobengula’s view

The King did not approve of the settler’s behaviour towards the Mashona who were his and his people’s, their ‘slaves’ and their ‘cattle.’[v] He believed the settlers should not exercise any authority over his Maholi and should not interfere in squabbles between Mashona kraals. In February 1892, when the British South Africa Company Police took action, he wrote to Loch[vi] saying: “I don’t like the action you have taken with the Mashona. What does it matter if the Mashona fight among themselves? It is bad for you to mix yourself up in such matters.”[vii]

In Bulawayo settlers were told to leave local people alone, the amaNdebele could do what they liked with them and nothing must be questioned by them. Later Lobengula asked Jameson: “Are the Amaholis then yours?”

Lobengula feared most the Mashona taking up employment with their new ‘masters’ as this undermined his own authority and brought into question his previous accepted right to raid them at will.

(2) The settler’s and BSA Co view

From earliest days John Moffat[viii] had been warning the BSA Co that if the Mashona people claimed the Company’s protection from Lobengula it would have dire consequences. He stated the Mashona and their herds were considered amaNdebele property and Mashonaland was their raiding ground. He believed that Lobengula could not accept what seemed reasonable to the settlers…that he should keep to his side of the ‘border’ just as the BSA Co would enforce recognition of a border on the settlers and he would accept that the Mashona were no longer under his control.

However the BSA Co and settler’s required peace and order and Mashona labour to carry out their farming and mining and so it was increasingly necessary to show the Mashona that they could rely on settler protection. BSA Co officials thought that if the Mashona were encouraged to accept settler protection they would, out of gratitude, agree to work on the farms and mines.

This did not mean the BSA Co and its officials tolerated any Mashona opposition to their control. Any opposition brought swift punishment. Mashona kraals accused of theft or other crimes could expect fines of cattle, goats and grain, or even have their huts burned down. When Jean Frederique Victor Guerolt was murdered at Wathas Hill in the Mazoe (now Mazowe) district on 22 January 1892, the kraals of chiefs Chirumziba and Golodaima were burnt down. Individuals might be flogged.

The worst example of friction between settlers and the Mashona was the killing of headman Ngomo along with his son and twenty-one others in his kraal on 17 March 1892. Details are provided in Note xxx in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident.’

But as Glass writes: “A useful labour force does not develop from ill-treatment.”[ix]

(3) The above opposing views would ultimately lead to the 1893 Matabele War

Jameson was caught between these two forces that would in the end mean an end to his policies to promote peace and engage the BSA Co in conflict.

In 1878 prior to the occupation of Mashonaland, Selous[x] had visited Makonde’s kraal and went hunting up and down the Hunyani (present-day Manyame river) He was back in 1880 describing chief Makonde as: “holding his life and property at the caprice of the Matabele chief Lobengula.” However he noted of the Mashona: “They seemed very industrious, cultivating great quantities of kaffir corn, [sorghum] mealies, ground nuts and a few sweet potatoes; they must have got any amount of vegetable food and lots of beer.” He also noticed cotton being woven.

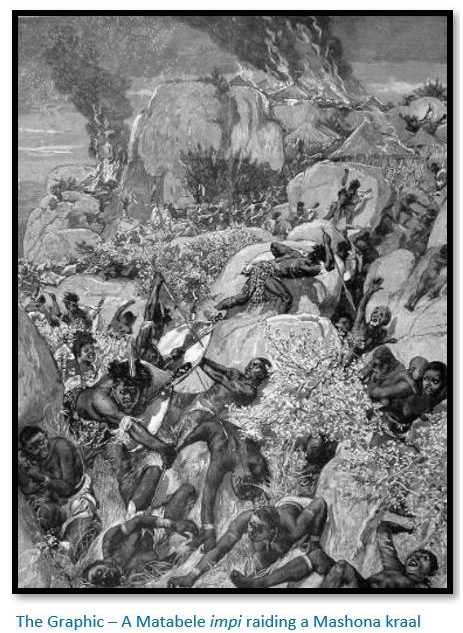

Just two years later in 1882 he travelled north towards the Zambesi river making a map and noticed that all the kraals appeared deserted. “The abject state of fear in which the inhabitants of this part of Africa were living can scarcely be apprehended by the members of any society living under a powerful and settled government and must have made the natives’ lives a misery.”[xi]

Colin Harding in command of the Native Police Force in Mashonaland wrote: “The Mashona preferred the occasional raid of the Matabele, with its results of plundering and looting for a short period, to the everlasting domineering of the government who always wanted something or other; either men to work, or Hut Tax, or from their point of view some damn thing or other.”[xii]

The killing of Chief Lomagundi[xiii] by the amaNdebele in November 1891

Jameson did not question Lobengula’s right to levy tribute and punish his vassals.

In late November 1891 Lobengula chose to ignore the border and assert his ownership by sending his impi’s to Mashonaland. Chief Lomagundi has stated that he was no longer prepared to pay annual tribute and no longer recognised amaNdebele supremacy.

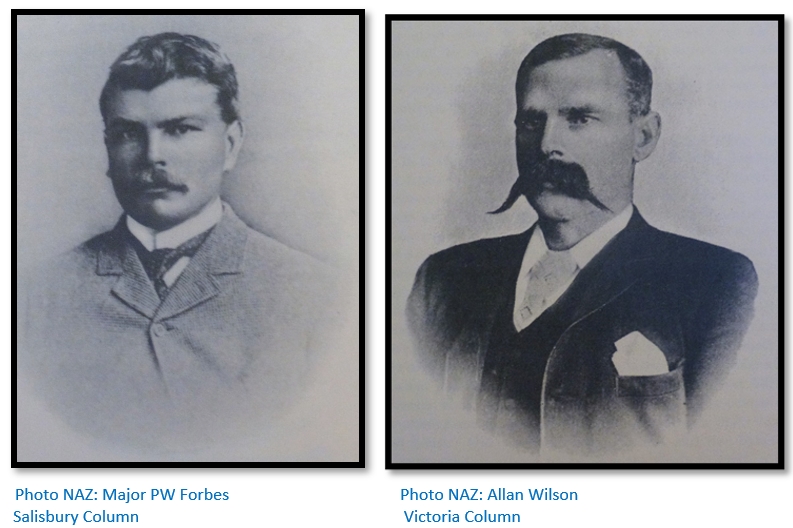

The first Jameson knew of the incident was when some of the chief’s people arrived in Salisbury on 1 December 1891 and reported the killing of Lomagundi himself and three of his people by a body of amaNdebele. Captain PW Forbes,[xiv] then Magistrate at Hartley Hills, was sent to investigate and Jameson wrote to Lobengula via John Moffat that should any of Lobengula’s vassal chiefs refuse to pay tribute, the BSA Co would collect it on his behalf and avoid future incidents. Clearly this would never be acceptable to Lobengula.

Forbes’ report arrived a week later and resulted from interviews with Lomagundi’s headmen. About forty amaNdebele had arrived at the kraal about 25 November 1891. They asked the chief why he had accepted gifts from the Portuguese and English and shown them where to dig for gold. Also why the chief had given Selous and others guides to the Zambesi river without requesting permission from Lobengula, to whom the country belonged. The chief said he would reply next day. But next morning the amaNdebele went to Lomagundi’s kraal when he and three of his headmen were shot.

Johan Colenbrander, the BSA Co representative at Bulawayo, wrote a reply dated 15 January 1892 on Lobengula’s behalf to Jameson. “I sent a lot of my men to go and tell Lomagunda to ask you and the white people why you were there and what you were doing. He sent word back to me that he refused to deliver my message and that he was not my slave – this is why I sent some of my men to go and kill him. Lomagunda belongs to me. Does the country belong to Lomagunda?”

Forbes’ report gives no indication of the first amaNdebele visit.

Repercussions of Chief Lomagundi’s killing

(1) Clearly Lobengula believed that as long as no settler’s were harmed, he could continue with his past practice of sending his impi’s into Mashonaland. It does not seem to have occurred to him that the raids disturbed the settlers and brought all their farming and mining activities to a halt as their Mashona labour all ran away.

(2) Additionally Lobengula was disturbed by Jameson’s letter saying the BSA Co could collect unpaid tribute for him as this was a clear violation of the King’s authority.

(3) This was the first time a Mashona chief had told the king he was no longer his slave and that his authority was to the BSA Co.

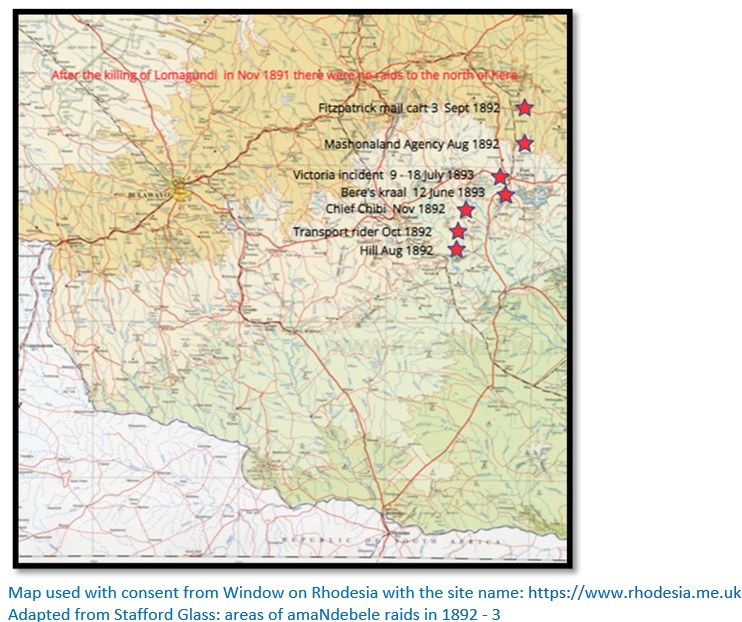

(4) The amaNdebele thereafter stopped raiding into northern Mashonaland and diverted their attentions to the south between Charter and Fort Tuli.

(5) When the Mashona accepted the BSA Co’s authority and protection that it offered, the seeds were sown for the ensuing conflict.

Rising tensions in the Victoria district due to amaNdebele raiding

These are described in the article Re-examining the events leading up to the ‘Victoria incident.’ The graphic showing the location of amaNdebele raids from the same article is reproduced below.

Local newspaper articles agitated for some action from the BSA Co. The Rhodesian Chronicle carried an article declaring that in August 1892 the first instance of a settler being stopped on the road between Tuli and Victoria had been reported: “a Mr Hill was stopped 12 miles to the north of the Nuanetsi [present-day Mwenezi] by an impi of 200 – together with a large force of Makalaka women taken from kraals in the neighbourhood where they had been raiding.” The article went on to say Mr Hill’s rifles had been stolen and he was refused permission to continue until he had ‘given them bonsellas of tea and coffee.’

This was disturbing news as it appeared that travellers between Tuli and Victoria were now in danger of being molested by amaNdebele impis and the same newspaper had a leading article on 17 September 1892 with the headline of ‘The Matabele Raids.’ It declared: “The traveller cannot consider himself free from the chance of a possible meeting with the Matabele. But the question arises, are the authorities doing their best to protect the settlers from raids of the Matabele…the manner in which wandering impis of Matabeles have recently treated travellers has been the cause of some alarm and uneasiness in the country.”

The article suggested that Mr Hill was not the first traveller to be robbed: “these impi's which regularly roam about Mashonaland after the great beer drinking in February until the ploughing begins in November, is to collect tribute from the Mashonas and Makalaka, or, in other words, to rob them of every grain of corn and every head of cattle. It is, we contend, a disgrace to the Chartered Company to allow these raids on natives whom they have taken under their protection.”

The article concluded: “The Matabeles will naturally look upon their treatment as a tribute to their power and unless the BSA Company changes its present policy of bullying the weak and cringing to the powerful, they will not be able to avert trouble with the Matabele which will be the consequence of the death of Lobengula.”[xv]

The lengthy article above concerned not only the amaNdebele theft from Mr Hill, but also the robbery of the post cart. News was received on 6 September from Fort Charter when George Fitzpatrick, the conductor, telegraphed that thirty amaNdebele had stopped his cart and taken what they wanted. About twelve miles from Makori post station they had met armed amaNdebele sitting on the road. The headman asked for a present and after being told to ‘clear off’ guns were pointed at Fitzpatrick. The headman then took blankets and overcoats belonging to the three Europeans and three native servants.

Within a month another similar theft took place between the Lundi [Present day Runde] and Nuanetsi rivers – the victim was a transport-rider: “all his goods were taken, he himself being ill-treated.”

The killing of Chief Chibi (Mazorodze)

De Waal, who accompanied Rhodes in 1891, wrote[xvi] in his book describes how the amaNdebele collected tribute from Lobengula’s vassals. As many as 600 amaNdebele would arrive simultaneously with each party staying at a different kraal. If any dispute arose over the amount of tribute to be handed over, all the tax-gatherers quickly assembled to attack the kraal and took away by force as many women, children, cattle and sheep as they could take to Bulawayo.

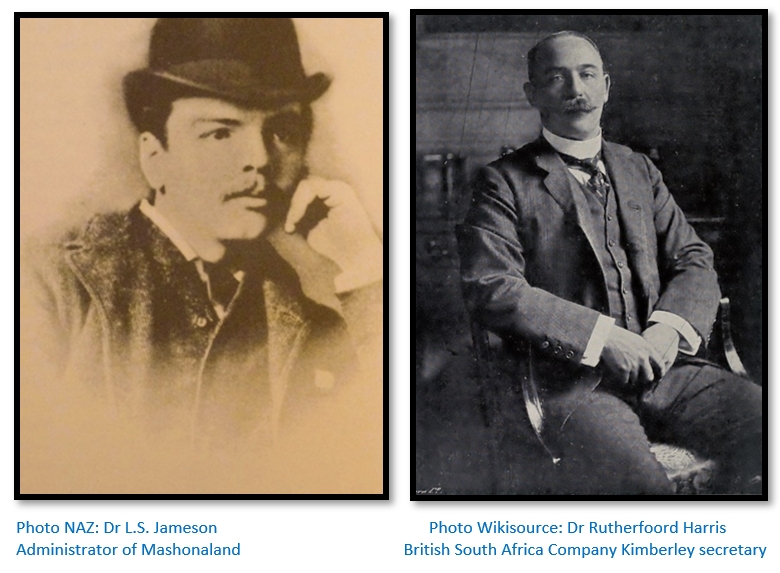

In November 1892 Lobengula sent an impi to punish Chibi who had many cattle. He was captured, taken to Bulawayo and apparently, skinned alive.[xvii] If he believed that Lobengula would not attack him because of the settlers in Mashonaland, he was proved sadly mistaken. Jameson told Rutherfoord Harris[xviii] that: “I sent a severe message to Lobengula” and received the usual answer that some cattle had been stolen and his impi had been told not to interfere with the settlers.

Jameson is relaxed but Victoria residents are getting nervous

Despite the above incidents, the Administrator seemed sanguine. Lobengula had been urged to keep his tribute-seeking impi’s away from Victoria, but the settlers still believed that Lobengula was being permitted to do as he pleased and in so doing reminding them that they were in a land that belonged to him.

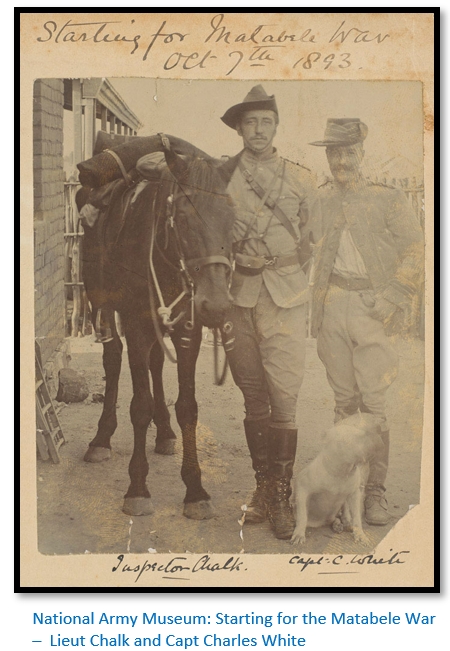

Wire cutting of the telegraph line

In December 1892 Jameson asked Charles Vigers, the mining commissioner at Victoria, to send Lt Chinery and a police patrol to search kraals in the area of the Naka Pass near the Lundi (present-day Runde river) where the break had taken place, and if the culprits were found to have them flogged. Jameson thought they would be Makalakas, but when questioned, they named two amaNdebele, Chakala and Mazererree, as the guilty parties.

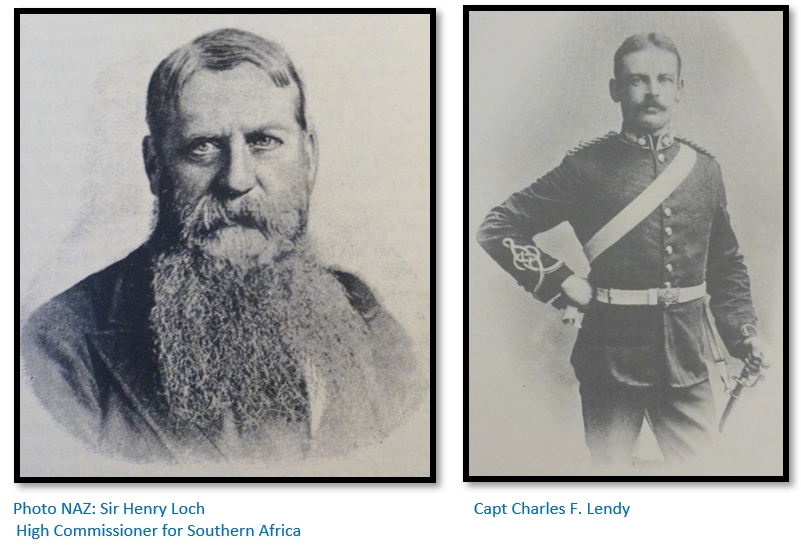

Jameson sent Captain Charles Frederick Lendy with a small escort to carry a letter protesting the theft and breakage of the telegraph; the party arrived in Bulawayo on 23 January 1893. He was anxious to maintain friendly relations with Lobengula – the letter stated Jameson was sure the King was not aware of the thefts but hoped he would: “take measures to stop them and so prevent any possibility of a collision” between his people and the settlers.

On his return Lendy reported the King laid the blame on the Maholi and said he did not recognize the two names. After further investigations it turned out the Makalakas at Nata Pass admitted they cut the telegraph line and that the guilty ones had fled. On his return to Victoria in March 1893, Lendy’s reward was to be appointed resident magistrate.

Both Jameson and Lobengula were pleased with the outcome; Colenbrander wrote: “Old Ben awfully pleased with you for sending and letting him know your troubles and difficulties with the Amandebele. For he says: ‘If the doctor does not tell me how should I know of my people’s misdeeds and I am anxious that we should live peacefully together.”

Another wire cutting incident

The telegraph was cut once more in early May 1893 and the theft traced to the kraal of Gomalla, a petty Maholi chief under Setoutse and the police sent to demand either the culprits be handed over or a fine paid in cattle. Gomalla handed over cattle knowing full well they belonged to Lobengula. He told chief Setoutse that the cattle had been seized despite being told they were the King’s cattle and Setoutse reported this to the King.

Lobengula was incensed and protests were sent to Loch and Jameson. “Now I want to know whether it is right that you should punish these people without knowing for certain they are the real offenders. In any case, why should you seize my cattle - did I cut your wires? It is your excuse, you accuse my people when probably the damage is done by some of your discharged men.[xix] I also wish you to know that my people begged and prayed of me to allow them to go and fetch the cattle, but I would not allow it and prefer settling these matters amicably.”[xx]

Jameson advised he would send the cattle to Tuli where they were sent in July. Maholi herders sent to collect them left before they arrived. Rinderpest broke out and the cattle were sent across the Limpopo for better grass and isolation. In August Lobengula asked for his cattle and pointed out he lived in Bulawayo not Tuli. Colenbrander advised Jameson to have the cattle sent to Bulawayo: “unless you are prepared for a lot of unpleasantness.” By mid-August 1893 preparations for the invasion of Matabeleland were well underway and Jameson said: “It would be absurd to send cattle to Lobengula under present circumstances.”

The ‘small’ impi of June 1893

On 11 June there were reports the amaNdebele were raiding within ten miles of Victoria. Lendy took a sergeant, two troopers and an interpreter and came to a kraal and granary that were on fire. They camped the night and next morning: “three or four men from Bere’s kraal came up and said the Matabeles had raided them, taking all their cattle, women and children, and killing several of them.”

Lendy and his men rode on and came up with the impi[xxi] who: “ran in all directions, dropping whatever they might be carrying and shouting that they had only come to punish the Mashonas. We had to ride some considerable distance in pursuit. Before they condescended to stop and bring their headmen to come and talk.” It had been stated that Bere had stolen thirty of Lobengula’s cattle and the King had said: “go and get the cattle back but be very careful to touch nothing belonging to the white men.”

Lendy’s message to the induna

Lendy believed it was an inter-tribal dispute and he should not interfere, but he asked the induna to remind Lobengula that his warriors should keep to the west of the border and that there were risks entailed in crossing it. However the Mashonaland Times of 20 July 1893 stated: “Lendy interviewed the marauders who then informed him that it was Lobengula’s intention to send a large impi to thoroughly wipe out the Makalangas whom the King accused of crossing the Matabeleland border…and stealing cattle from outlying Matabele posts.”

Jameson’s policy towards Lobengula until June 1893

The killings of chiefs Lomagundi and Chibi, the robberies on the Tuli – Victoria road and the post cart beyond Makori post station, the wire-cutting incidents and the small impi were all handled in a tactful way by Jameson. To the settler’s it was a sign of the BSA Co’s weakness, that of ‘cringing to the powerful’ in failing to put a stop to amaNdebele incursions across the border and the subsequent disruption to farming and mining activities when their Mashona employees ran away.

In Jameson’s defence the finances of the BSA Co were in poor shape – the police force had been laid off to reduce the cash outflows and replaced by volunteer units, the country was also woefully short of horses and so as long as the impis did not disturb the settlers Jameson was prepared to handle the amaNdebele tactfully.

The ‘big’ raid of 9 July 1893 on the Victoria district

Lobengula believes the ‘small’ impi was a failure as it did not capture the cattle stolen by Bere’s people. James Dawson wrote a letter from Lobengula on 28 June stating that an impi is leaving Bulawayo to: “punish some of Lobengula’s people who have lately raided some of his own cattle.” The settlers are to understand: “it has nothing whatever to do with them” and “not to oppose” it in its progress.[xxii]

Colenbrander returned from Hope Fountain and sent telegrams on 29 June on behalf of Lobengula to Moffat, Lendy and Jameson.[xxiii] They all say much the same thing – a large force will be sent to punish Bere and others for their misdeeds, the warriors have been given “strict orders not to annoy any whites they might meet” against whom “he has no hostile intentions.”

When Jameson received the telegrams on 9 July at Salisbury you will see that in his reply to Colenbrander and Lobengula he still believed the old policies remained in place. “Thank the King for his friendly message and tell him I have nothing to do with his punishing his own Maholi but must insist that his impis are not allowed to cross the border agreed upon between us. He not being there, they are not under control, and Captain Lendy informs me that some of them have actually been in the town of Victoria, burning kraals within a few miles, and killing Mashonas who are the servants of the white man. Also that they have captured some cattle of the government and of other white men. I am now instructing, Captain Lendy to see the head induna, tell him that those cattle must all be returned at once and his impi must retire beyond our agreed border. Otherwise, Captain Lendy is to take his police and at once expel them, however many they are. The King will see the necessity of this, otherwise the white men getting irritated, the expedition may never return to Bulawayo."

Results of the ‘big’ raid

Stafford Glass writes: “outside the town of Victoria, the Matabele were pursuing their orgy of fire and destruction. The Mashona, as was their wont in such raids, fled to the kopjes and inaccessible places, leaving their kraals and granaries to be razed and their cattle to be driven away. During the night of 9 July the kraals burned continuously; and on Tuesday 11 July, the fires still blazed. Night after night the sky was lit up east and west as huts burned where the impis passed through with assegai and fire.”[xxiv]

A figure of 400 Mashona killed was quoted, but nobody really knew. The Rev. AD Sylvester wrote in a letter: “To Europeans who know little of the situation it would be a sickening sight to see the number of human beings lying dead on all sides, mutilated by the Matabele…no christian people can simply fold their hands and allow hundreds of their fellow creatures to be murdered wholesale.”

Alfred Drew said: “the bodies of several native servants and herds of the settlers slain on these occasions were afterwards seen in the course of our patrols of the next few days.”

Meikle said: “The country was laid waste and not a kraal left standing. The inmates for the most part took refuge with their flocks and herds in inaccessible places. The greatest loss was the granaries.”

Selous quotes the experience of Richmond, a prospector: “having been summoned to Victoria by Captain Lendy, in common with all the other white men who were living in the various mining camps in the outlying districts, was coming in with all his worldly goods packed on a donkey. This donkey was being led by a Mashona lad, Mr Richmond walking behind. A party of Matabele being encountered, the Mashona boy let go of the donkey and clasped Richmond round the legs. The Matabele dragged him shrieking and assegai’d him to pieces before the eyes of his master. Richmond, although he had a rifle with him, was afraid to use it; but he remonstrated strongly with the murderers of his servant, when one of them, placing his hand on his arm, said, ‘You keep quiet white man; we have been ordered not to kill a white man now, but your day is coming.”

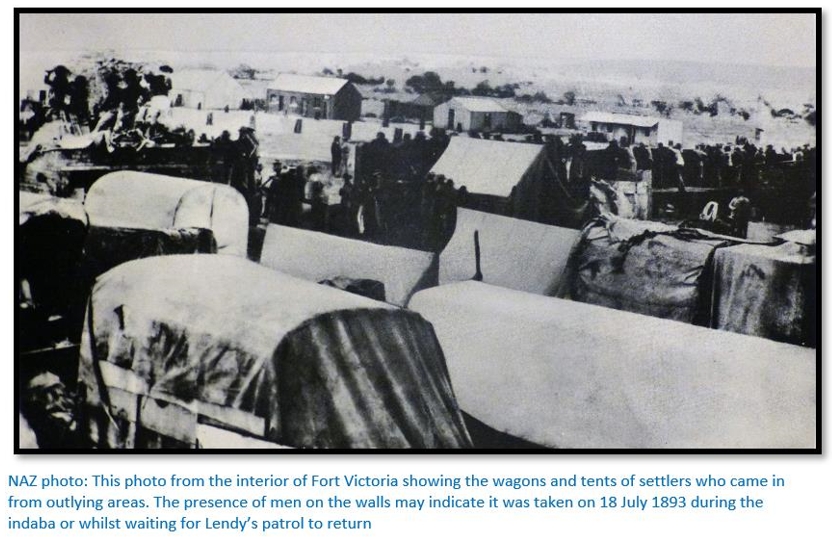

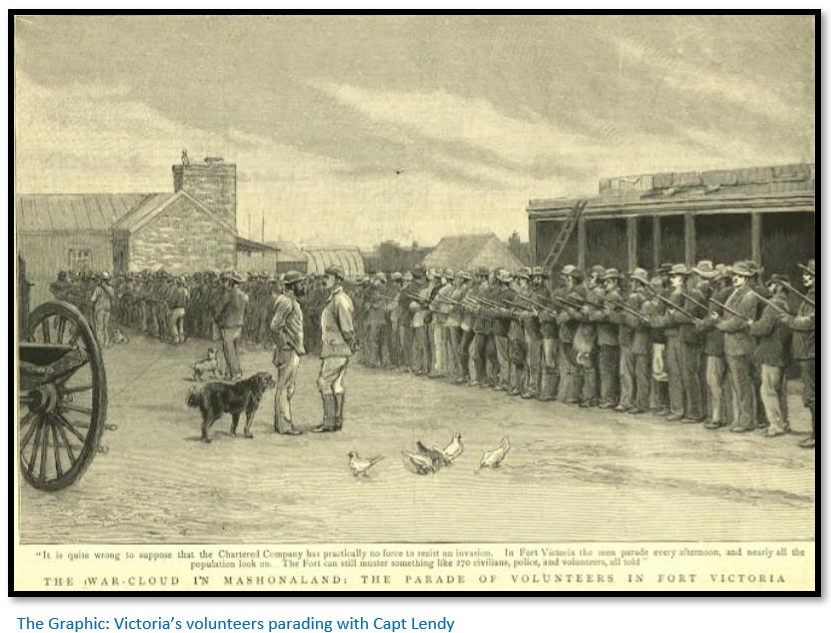

Victoria prepares to defend itself

Victoria became an armed camp in which the armed settlers prepared to protect themselves. About 90 women and children were placed within the buildings of the fort that had only been built a short time before with the first tower completed in 1891 (on the left below, now housing a bell) and the second in 1893.

The magistrate’s office in the court house was converted into a hospital run by the Dominican sisters. The wagons of settlers living in the district were formed into a laager under the south wall of the fort and at night everyone slept inside the fort. The fort itself was surrounded in barbed wire entanglements and pickets were continuously roaming outside to guard against surprise attack.

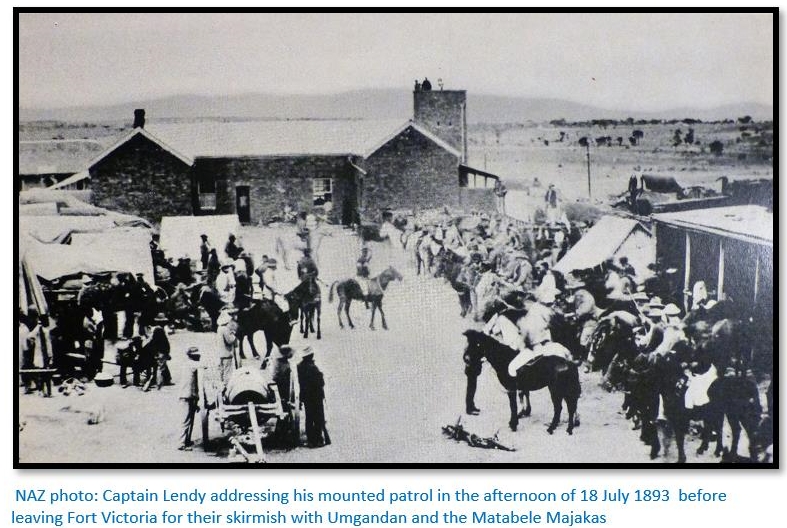

Captain Lendy, as Victoria’s Magistrate, was in charge of all these preparations and did a good job in preparing the fort against possible attack. At the time there were only seven BSA Co police left in Victoria and only eighty-two horses in the entire district with only fifty fit enough for patrolling.

The big raid itself and the Newton investigation into its circumstances are discussed in detail in the article The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’ under Masvingo province on this website and are not repeated here.

Effect on settlers activities

With all the miners and farmers summoned into Victoria and the panic-stricken disappearance of all their Mashona workers, all mining and farming activities came to a halt. Locals said that: “within 48 hours of the appearance of the Matabele every native had deserted and fled to his kraal.” Transport riders loaded with supplies, simply dumped their loads in the open veld and turned back for Tuli.

There does not appear to have been any damage caused to settler homesteads or farms, except that Mashona workers were killed. No settlers were killed and few of their cattle and livestock were taken. The settlers committee stated stolen stock comprised: “50 cows and oxen, 280 sheep and goats, 10 asses and 15 pigs.” Manyao, their induna, agreed to return cattle taken from settlers at his meeting on 10 July 1893. The raid clearly was on the Mashona and not the settlers according to Lobengula’s instructions.

Jameson travels to Victoria

Jameson left Salisbury on 13 July by horseback and wired Loch from Charter. “Here at present, this is merely a raid against Makalakas around Victoria and not against whites. Magistrate wires me here that Matabele induna will await my arrival and then I hope to get rid of them without trouble. Will be in Victoria on Monday, then will wire you fully.”[xxv]

Salisbury (present-day Harare) to Makori post station is 241 km which Jameson rode by horseback, but at Makori was a Mr Wrey with a cart and 8 mules and Jameson, now suffering from piles, rode in the cart with Wrey writing: “as I travelled with him during the last section of the journey, I can most emphatically state that even after having heard the fullest details of how serious the aspect of affairs was, he was most loath to take offensive measures, could he have seen any other way out of the difficulty.”

Jameson at Victoria

Jameson arrived at Victoria on 17 July and summoned the induna Manyao to an indaba that was held next day. These events are discussed in detail in the article The Newton Commission conclusions on the ‘Victoria incident’ and do not need repeating here.

However once at Victoria, Jameson made a complete volte-face and completely discarded his old policies and decided on military action that previously had seemed so foreign to his character and methods.

Jameson abandons his policy of restraint

On 15 July 1893 at a public meeting in Victoria heated local settler speakers one after another demanded that Jameson stop putting off action with the amaNdebele and threatened to deal with them themselves supported by 500 Boers from the Transvaal.

Stafford Glass writes: “It became clear to him [Jameson] that the issue of actual physical danger to the Europeans was not the only issue. The devastation, the cessation of work, the virtual siege of Victoria, the attitudes of the pioneers and the plight of the Mashona, all indicated that the Matabele had to be driven away.”

Two days later Jameson abandoned his policy of restraint and telegraphed Rhodes saying the chartered company must deter the amaNdebele with a show of force and drive them off and received Rhodes’ reply in agreement on 17 July: “Yours just received. Mr Rhodes understands that you may find it necessary, in the interests of the Mashonas, women and children, to drive the Matabele away, in this he thoroughly concurs, but he says if you do strike, strike hard.”[xxvi]

I hereby declare war on the Matabele

On 18 July the indaba with Manyao was held…two hours after it finished Jameson sent Lendy out with a patrol with verbal instructions: “You have heard what I have told the Matabele. I want you to carry this out. I do not want them to think it is merely a threat. They have had a week of threats already with very bad results. Ride out in the direction they have gone to Magomoli’s kraal. If you find out they are not moving off, drive them as you heard me tell Manyao I would. And if they resist and attack you, shoot them.”

On his return Captain Lendy said: “Doctor, you told me if I struck I was to strike hard. And I think I have accounted for 300.” Jameson then turned around to the people on the walls and said: “I hereby declare war on the Matabele.”[xxvii]

That evening Jameson spent in the telegraph office in an exchange with Loch and Rhodes.[xxviii] Unfortunately copies of the telegrams were not kept. It was in this exchange that Rhodes sent: “Read Luke XIV, 32” and Jameson read: “Or what king, going to make war against another king, sitteth not down first, and consulteth whether he be able with ten thousand to meet him that come against him with twenty thousand?”

During this telegraphic exchange Rhodes stated the BSA Co had no money available and he had spent his own money on constructing the telegraph line. Jameson replied: “By this time tomorrow night you have got to tell me that you have got the money.”

Jameson sets aside his old amaNdebele policy

On the 18 July Jameson understood the old policy with regard to the amaNdebele had failed. Stafford Glass writes: “From that date Jameson the circumspect, the diplomat, gave way to Jameson, the man of action… after 18 July he became the aggressor who would rather act than negotiate and destroy rather than cure.”[xxix]

Glass continues: “The character of Jameson as administrator was that of Jameson as doctor. He handled men as he had handled his patients; he persuaded, he coaxed, he used his charm, and he remained convinced that his methods would solve problems as his medicines had cured the ailing. After 18 July, he became the aggressor who would act rather than negotiate and destroy rather than cure. The real turning point in Jameson’s life was on 18 July 1893.”[xxx]

The BSA Co argues that raiding by the amaNdebele must be stopped

Jameson’s border policy and his tactful handling of Lobengula was designed to minimise settler fears. The ‘big’ raid of 9 July against the Mashona and Makalakas with 2,500 amaNdebele warriors augmented with 1,000 armed Maholi created uncertainty and disturbance amongst the settlers who knew further raids could come at any time and would paralyse all commercial activities.

Every threat to stall the threat of amaNdebele raids upon the Mashona had failed and therefore Jameson’s policies had resulted in failure. The BSA Co Report for 1892-4 declared that war: “was forced upon the company by the attempt of the Matabele to enforce their claim to murder or carry off the Mashona men, women and children to slavery. This was the true and only ground of the differences which led to the war. If the company had not protected the Mashona there would never have been trouble with the Matabele. From the very first the latter had insisted on their right to enslave or murder the Mashona as they pleased and during the last year or more the insolence and aggressive acts of the Matabele were very much on the increase.”[xxxi]

Was the invasion of Matabeleland always on the cards?

On 29 November 1892 at the second AGM of the BSA Co Rhodes declared: “I have not the least fear of any trouble in the future from Lobengula…I have never met anyone in my life whom it was not as easy to deal with as to fight.”

Prior to Jameson’s change of attitude it was Rhodes’ hope that the development of Mashonaland would take place with the amaNdebele as peaceful neighbours. Mashonaland had been occupied and he thought that was sufficient for the present: “I thought that that position would last for five or ten years.”

Rhodes opinion in August 1893 was: “I would much rather it [the invasion] had been postponed for a year.” But Stafford Glass believes that what is also clear is that Rhodes, unlike Jameson did not consider that Matabeleland could be acquired peacefully. Perhaps he hoped “that Jameson's policy would prove successful, but without undue optimism was prepared to fight the amaNdebele should that later become necessary. Matabeleland was the goal of the Company, whether through war, through some sort of ‘buying’ or through Jameson's peaceful policy.”

Jameson makes up his mind that the amaNdebele question needs settling

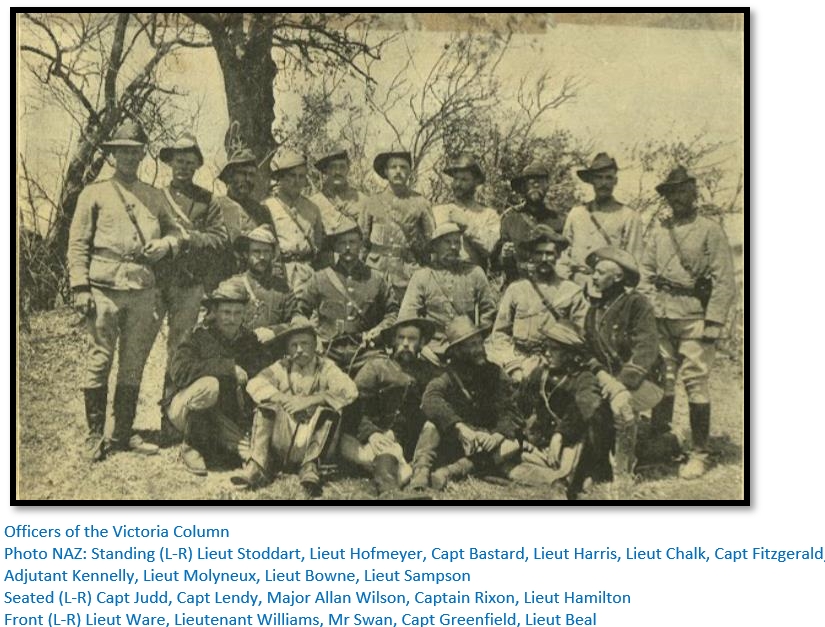

On 19 July 1893, before the public meetings in Victoria and Salisbury were held, Jameson told Patrick Forbes, Salisbury’s resident magistrate of his plan for three columns to advance upon Bulawayo from Victoria, Salisbury and Tuli under Forbes, Lendy (later replaced by Allan Wilson) and Raaff.

The same evening he telegraphed Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner in Cape Town. He told Loch he wished action to take place before the summer rains set in during November and whilst an impi of 6,000 amaNdebele was away raiding chief Lewanika’s country in Barotseland.

Loch was sufficiently persuaded to warn Lobengula by telegraph on 20 July that the raid on Victoria would bring him: “the punishments that befell Cetewayo and his people.”[xxxii]

Public opinion is for action against the amaNdebele

In Victoria on 21 July 1893 a public meeting appointed a committee: “to lay before [Dr Jameson] tangible proofs of the paralysing effects which these continual scares have and will have upon all the undertakings and business of whatsoever kind in the district and throughout the whole of Mashonaland, and by doing so to endeavour to prove to you the absolute necessity of an immediate settlement of this question, and to show how fatal to all interests will be the temporary patching up of the present difficulty.”

The next day the committee presented Jameson with its feelings that Lobengula had: “broken his word once more in crossing a forbidden boundary and having so done they know that any promises made by him as to the future delimitation of his raiding areas are not in any way to be trusted.”

In a 22 July telegram to Harris, Jameson said: “I feel sure work will not be recommenced or even transport carried along the roads till some definite action on our part is taken of going into Matabeleland to settle the question finally which can easily be done by us in Mashonaland.”

The High Commissioner is supportive of action against the amaNdebele

On 24 July Loch made it clear that Imperial policy remained the same and the responsibility for keeping law and order and the safety of settlers lay with the BSA Co, but perhaps the most useful statement was: “I am fully aware that the best preservative against danger is to be prepared to meet it”[xxxiii]

On 26 July Loch telegraphed Ripon[xxxiv] stating: “The British South Africa Company are fully aware that they are solely responsible for providing both men and money for any war and for maintenance of peace and order in Mashonaland and Matabeleland.”

Once Jameson had this go-ahead, all he had to do was continue with the theme of war scare and prevent any moves for peace.

The High Commissioner alerts the Colonial Office there might be spill over

However Loch also made it clear that war in Matabeleland would mean: “probable disturbances in Bechuanaland Protectorate” and was thus alerting Ripon to the fact that Imperial Forces in the form of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BBP) might also be drawn into any conflict. Indeed, Loch over the coming months would arm and strengthen the BBP.

Relations between Lobengula and Jameson are deteriorating

When Lobengula received news that Mashonas had been given protection in Victoria he wrote an angry message to Jameson complaining that he had allowed: “Captain Lendy to refuse the Amaholis and their cattle to be delivered to my impi” and asked: “why do you interfere or protect them?”

On 27 July Lobengula heard from the returning impi that they had been fired upon and that Umgandan, a young induna killed. Lobengula instructed Colenbrander to write letters to Loch and Harris in which he complained about the firing on his impi and settler protection of the Amaholis.

Although Jameson wanted compensation from the amaNdebele for losses suffered at Victoria on 11 August, Colenbrander sent a message to John Moffat saying the King: “flatly refuses to either give up or give compensation for any cattle taken at Victoria belonging to white people or goods destroyed until such time that his Amaholi slaves, children, cattle, goats and sheep are delivered to him that lately got protection from white people at Victoria by Dr Jameson.”

On 17 August the Colonial Office wrote to Harris stating that they would not agree to the demand on Lobengula for compensation.

The Government will not agree to war without ‘proper authority’

Loch needed to delay any advance on Matabeleland until he was ready to take part through the BBP and had no wish to be left sitting on the fence whilst the BSA Co extended their rule over Matabeleland.

To ensure no premature actions began Loch advised Harris that he had been authorised by Lord Ripon to inform him: “that unless the Company’s people are attacked no aggressive movement should be made without the previous knowledge and permission of the High Commissioner.”

Jameson’s preparations at Victoria and Salisbury

Jameson told Forbes he wanted the force to be mounted. He had been influenced by Hans Sauer[xxxv] in Victoria who told him that impis were completely at the mercy of mounted infantrymen. There were plenty of volunteers prepared to fight and the necessary military equipment, but a great shortage of horses. Willoughby[xxxvi] said there were only 100 horses belonging to the BSA Co at the time; Forbes said he needed 250 horses for the Salisbury column alone. Raaff was sent from Tuli to Johannesburg to buy a further 750 horses.

Jameson wanted his preparations kept secret; neither Loch, nor the directors of the BSA Co were informed of preparations. Harris informed the directors on 26 July: “Lest an erroneous impression should get abroad respecting the purchase of horses for the Company’s service, I would explain that some months ago, Dr Jameson suggested the purchase of a few horses and Mr Rhodes has sanctioned this being done.” Rhodes himself paid £50,000 for their purchase.

In Victoria the organisation of the Victoria Rangers and the Victoria Burghers was taking place, although Lendy voluntarily stepped down in favour of Allan Wilson who was appointed in command on 31 August 1893.

On 7 September when Willoughby arrived in Victoria they were still waiting for horses, but by 23 September Harris informed Loch that there were 300 mounted men ready at Victoria.

Jameson was in Victoria from 17 July to 12 September; only being in Salisbury for a week and leaving the organisation of the Salisbury column to Forbes. He decided to move the Salisbury column to Charter to meet the horses. The first party left on 28 August, the remainder on 5 September, with a good send-off from the town’s people. On 7 September there were only 59 horses at Charter, but they gradually arrived and by the end of September the Salisbury and Victoria columns were reaching a state of readiness.

Raaff’s preparations at Johannesburg

Raaff’s volunteer force of 250 men was quickly recruited, although there appears to have been some wild spirits amongst them and they acquired the nickname of ‘Raaff’s riff-raff.’ Four were arrested after stealing bottles of liquor from a store at Hamman’s kraal on 28 August; on 1 September another was discharged and three others fined.

The Transvaal State secretary wrote to Loch on 2 September: “that a troop of persons in the service of the Chartered Company are trekking through the Republic and that they are stealing and robbing along the road.”[xxxvii]

Loch wrote to Harris enquiring about: “trekkers in the service of the Chartered Company who are passing through the South African Republic” but he seems to have presumed they must be connected to the horse-buying and asked that nothing be done to delay or interrupt their transport! The southern column was at Tuli on 29 September 1893.

The Victoria Agreement

The volunteers of all three columns – Victoria, Salisbury and Tuli - were to receive no pay, but were promised land and loot when the campaign was over. In August a "loot" committee was formed in Victoria with instructions to draw up an agreement on the rewards. The final agreements were:

(1) Each volunteer would be entitled to a 3 000 morgen (6 351 acres) farm in any part of Matabeleland with a quitrent of ten shillings a year. The farms had to be marked out within 4 months and the Company reserved the right to purchase their farms at £3 per morgen with compensation for improvements

(2) Each volunteer was entitled to 15 gold quartz reef claims and 5 alluvial claims with the proviso that a 30-foot (9 metres) shaft be sunk within 6 months or a 60-foot (18 metres) shaft within 12 months

(3) Cattle were to be divided one-half to the BSA Co and the balance to men and officers in equal shares.

The final document was given to Jameson on 4 October, although there were several new clauses which he refused to sign, instead signing the original document of 18 August 1893.

After the invasion, Rhodes proposed that all members of the BBP who had taken part also be accepted, but Loch told Lieut-Colonel Goold Adams it could not be accepted.

The loot committee was busy in 1894 registering ‘shareholders’ for those entitled to ‘dividend payments.’ Captured cattle sales took place as far away as Johannesburg and Kimberley. Capt H.M. Heyman (later Col Sir) estimated each volunteer might receive £30 when the ‘final dividend’ was paid in December 1894, but there is no record of what exactly was paid.

References

Colin Black. The Legend of Lomagundi. Art Printopac, Salisbury, 1976

J.S. Galbraith. Crown and Charter. The Early Years of the British South Africa Company. University of California Press, 1974

Stafford Glass. The Matabele War. Longmans, Green & Co, 1968

Colin Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall, London, 1933

[i] ‘Maholi’ was a term used by the amaNdebele to describe their “slave people” who comprised men and women that had been captured during impi raids – many into present-day Mashonaland

[ii] The Matabele War, P35

[iii] Crown and Charter, P290

[iv] The Matabele War, P35

[v] Ibid, P46

[vi] Sir Henry Loch, the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, 1889-1895

[vii] The Matabele War, P46

[viii] John Smith Moffat (1835-1918) was the son of Robert Moffat, the missionary based at Kuruman. He was based at Inyati mission for six years (1859-1865) before taking over the running of Kuruman mission. In 1879 he resigned from the missionary service and joined the British colonial service, being appointed assistant commissioner to Sir Sidney Shippard in Bechuanaland in 1884. Lobengula trusted Moffat and in February 1888 signed what was known as the Moffat Treaty that stipulated that Lobengula would not sign any concessions or other treaties without British approval – in return Moffat gave a verbal promise of British protection. Later Moffat fell out with Rhodes over his deceptions and particularly the circumstances leading to the 1893 Matabele War discussed in this article.

[ix] The Matabele War, P45

[x] Frederick Courteney Selous

[xi] Above quotes from The Legend of Lomagundi, P7

[xii] Far Bugles, P48

[xiii] Lomagundi is a misspelling of Nemakonde with Ne being an ownership prefix, meaning that Makonde is the owner or custodian of the land

[xiv] Patrick William Forbes (1861-1923) was Captain of B Troop of the British South Africa Company Police and took part in the occupation of Mashonaland. In November 1891 he was the Magistrate at Hartley Hills. He commanded the Salisbury Column during the Matabele War 1893.

[xv] The Matabele War, P54

[xvi] With Rhodes in Mashonaland, P301

[xvii] The Matabele War, P57

[xviii] Dr Rutherfoord Harris, the BSA Co secretary in Kimberley

[xix] A hint that the discharged BSA Company police were responsible

[xx] Ibid, P64

[xxi] The impi reportedly was made up of 70 warriors

[xxii] The Matabele War, P70

[xxiii] Dawson’s letter of 28 June was sent by runner ahead of the impi, but only delivered to Lendy on 10 July. Colenbrander’s telegrams written on 29 June were sent to Palapye for transmission to Salisbury and Victoria and only arrived on 9 July

[xxiv] Ibid, P75

[xxv] Ibid, P87

[xxvi] Ibid, P96

[xxvii] Ibid, P97

[xxviii] The telegraphist Mr W.T.E. Wallace confirmed this exchange took place on the 18 July 1893 – he was sending the messages and Jameson used his bible. Also present were Sir John Willoughby, Percy Inskipp and the magistrate’s clerk, Ivon Fry

[xxix] The Matabele War, P103-4

[xxx] Ibid, P104

[xxxi] Ibid, P83

[xxxii] Cetshwayo kaMapande, king of the Zulu Kingdom 1873 - 1879 and its leader during the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879.

[xxxiii] The Matabele War, P126

[xxxiv] George Frederick Samuel Robinson, 1st Marquess of Ripon (1827 – 1909) was Secretary of State for the Colonies between 1892 -1895

[xxxv] Hans Sauer doctor and lawyer who accompanied Rhodes to Mashonaland in 1892 and wrote Ex Africa. He was appointed head of the Rhodesian Exploration Company and settled in Bulawayo in 1894 where Sauer Town West, a suburb in Bulawayo, is named after him. H accompanied Rhodes to the Indaba with the chiefs in the Matobo in 1897.

[xxxvi] Sir John Willoughby (1859 – 1918) was Jameson’s military adviser

[xxxvii] The Matabele War, P147