Are there cultural links between Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe?

introduction

According to Thomas Huffman Mapungubwe (meaning ‘Hill of the Jackals’) was the crucible for a more socially complex society than had previously existed and on a much larger political scale than previously in southern Africa. The site saw changes in political power, leadership and authority and in organising, managing and maintaining that political power and he believes Mapungubwe was the precursor of Great Zimbabwe.[1] UNESCO say Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape demonstrates the rise and fall of the first indigenous kingdom in Southern Africa between AD 900 and 1,300.[2]

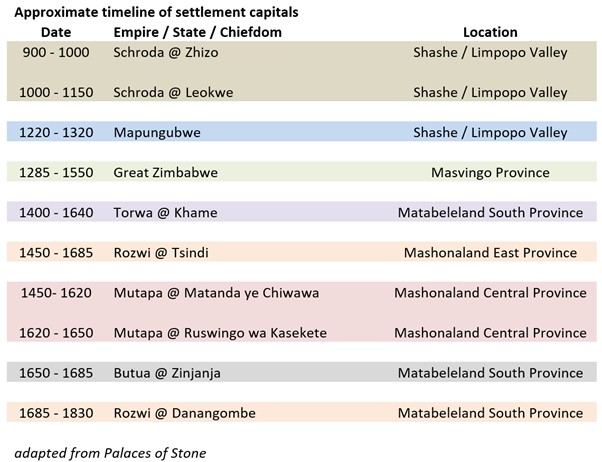

Huffman writes, “Mapungubwe's architecture and spatial arrangement provide the earliest evidence for class distinction and sacred leadership[3] in southern Africa. This stratification and associated ideology are the essence of the Zimbabwe culture.”[4] Huffman divides the Zimbabwe culture sequence into three periods: Mapungubwe (AD 1220 to 1290), Great Zimbabwe (AD 1290 to 1450) and (Khame (previously Khami) (AD 1450 to 1820) and believes that the extensive Portuguese eyewitness accounts written during the Khame period make it clear that the Zimbabwe culture was the product of a Shona-speaking society. See the article The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland under Mashonaland Central Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

From the discovery of Mapungubwe in 1931[5] until the late 1970s, it was interpreted as a lesser order settlement under Great Zimbabwe. However, from the early 1980s, its’ importance has been recognised. Recent excavations at Mapela Hill show evidence of similar social complexity as Mapungubwe, and are two hundred years earlier, indicating these changes were evolving gradually in the same region.[6]

Clearly there are strong cultural links between Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe. Both sites are considered to be important centres of social complexity and state development in southern Africa. Academics like Thomas Huffman have argued that Mapungubwe, which existed in the 13th century, may have played a role in the development of Great Zimbabwe. “Here, settlements and societies evolved and adapted, leaving sufficient evidence for archaeologists to develop a good understanding of the people - what they did for a living; how they develop trade routes to the east coast of Africa; and how, in time, they formed stratified, class-based societies that led to the genesis of the Great Zimbabwe state, a powerful precolonial empire that spawned as its political successors the equally impressive states of Torwa and Mutapa.”[7]

Mapungubwe falls within the Limpopo-Shashe Transfrontier Conservation Area (TFCA) This very extensive area of 5,040 km² will, when established, constitute an effective buffer zone. It is intended that each participating country will concentrate on one facet of protection: cultural heritage in South Africa; wildlife in Botswana; and living cultures in Zimbabwe.

However some archaeologists feel there is a strong case for Mapela Hill being earlier than Mapungubwe

Chirikure et al state, “Not surprisingly, in southern Africa the traditional assumption that the evolution of socio-political complexity began with ideological transformations from K2 to Mapungubwe between CE1200 and 1220 is clouded in controversy. It is believed that the K2−Mapungubwe transitions crystallised class distinction and sacred leadership, thought to be the key elements of the Zimbabwe culture on Mapungubwe Hill long before they emerged anywhere else. From Mapungubwe (CE1220–1290), the Zimbabwe culture was expressed at Great Zimbabwe (CE1300–1450) and eventually Khame (CE1450–1820)”[8]

Further details are given below the main body of this article.

Schroda

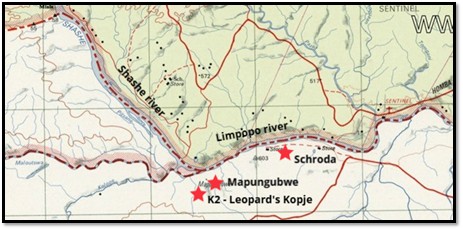

Main and Huffman[9] tell us that it was from Schroda, north-east of Mapungubwe around the Shashe / Limpopo confluence that the links to Great Zimbabwe first began. The rainfall then (1,000 – 1,500mm) was higher than present-day (300 – 350mm) and supported grain crops such as sorghum and pearl and finger millets and livestock for settled Zhizo communities even after the annual floods. Archaeological surveys have revealed the existence of over a thousand Iron Age sites in the region.[10] At Schroda the community numbered perhaps one thousand Zhizo individuals over a number of sites, the largest being perhaps 300 – 500 people, led by a senior chief, petty chief and headmen. They made a distinctive pottery-type and manufactured metal tools.

Prior to the Zhizo the San has inhabited the area but were driven off. The San hunter-gatherers of the Later Stone Age left many rockart sites across the region beginning 10,000 to 15,000 years ago.[11]

A large number of elephant lived on the nearby Kolope Pan and their ivory was likely bartered with Arab Swahili traders through Chibuene[12] on the east African coast of present-day Mozambique, some 650 kms away, and possibly also gold and copper, in exchange for imported cloth and glass beads that have been excavated in sites that were once Zhizo kraals.[13]

From about the 9th century, Swahili traders travelled south expanding their commercial networks and spreading Islam. Evidence of this trade comes from imported glass beads found at many early Iron Age sites and also the writings of Arabic geographers such as al-Masudi who visited the east African coast in AD 916 and described ivory being exported to India across the Indian Ocean and to China via the Silk route.

Marilee Wood: Indo-Pacific traded beads

Main and Huffman state that the organisation of an organised ivory trading network was a necessary foundation to the development of Great Zimbabwe and subsequent cultures.

Chirikure also writes that excavated artefacts from Schroda includes iron slag, metal objects, exotic glass beads, significant amounts of figurines and ivory, as well as domestic pottery and animal bone.[14]

Circa AD 1000 a number of changes occur in the Shashe / Limpopo Valley

Archaeologists believe that between AD 1000 – 1300 the climate entered a warm period which triggered a higher and more regular rainfall pattern and led to increased sorghum and millet grain crops that allowed more permanent settlements to flourish.

However, attracted by the more favourable living conditions, a new set of Iron Age farmers arrived from the south. Named the Leopard’s Kopje people,[15] they established their capital at a site now called K2,[16] on Bambandyanalo Hill, a few kilometres from Mapungubwe.

Farming led to the establishment of more permanent villages in place of the nomadic camps of the hunter gatherer bands that had moved seasonally from place to place for thousands of years and they chopped down trees and burned clearings in the woodlands to make fields where they planted crops. The impact of interaction between farmers and hunter gatherers was probably more disruptive to the latter group.

Map of the Shashe / Limpopo Valley – adapted from Sheet SF-35-12 Beitbridge 1: 250,000 Map: this map is used with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk

Huffman believes that the social changes the Leopard’s Kopje people introduced, “led to the emergence of a powerful ruling elite, the restructuring of society and, eventually, the establishment of Mapungubwe, the first in a series of precolonial states.”[17]

It was established by the cultural ancestors of the present-day Shona and Venda between AD 900 and 1300.

Photo Alex Schoeman: The site of K2 with Bambandyanalo in the background

The Leokwe people and K2 / Leopard’s Kopje

About AD 1000 a new capital was established at K2, located at the base of Bambandyanalo Hill by a group of people who expanded their territory which previously was in south-western Zimbabwe. Their cultural network can be traced through their pottery designs with a pattern known as ‘Leopard’s Kopje.’ Chirikure states that K2 also had a fairly large-scale iron working industry.”[18]

The arrival of the Leopard’s Kopje people prompted the movement of many Zhizo people to the west around Touswe in present-day Botswana. Those Zhizo that remained modified their pottery style and decoration that archaeologists have named Leokwe. Main and Huffman maintain their status was subordinate to the newcomers at K2 as they became cattle herders and that gave rise to an ‘ethnic stratification’

However despite their inferior social status, it was recognised that the Leokwe people had a spiritual relationship with the land and retained their ritual roles and were given responsibility for organising and managing the initiation schools for the children and puberty rituals for boys. At Schroda over four hundred clay figurines of animals, humans and fantasy creatures were found by archaeologists at Leokwe sites.

It should be noted that this model has been challenged by Calabrese who showed that the producers of Zhizo-style ceramics co-resided with Leopard’s Kopje farmers in the Mapungubwe area during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

University of Pretoria Museum; The Mapungubwe Collection of 13th Century clay figurines

The improved climate resulted in the growth of the population to an estimated 1,000 – 2,000 at K2 itself and the same number at nearby surrounding sites. This was sustained through growing cattle herds and a reliable food supply. Archaeologists have found traces of millet, sorghum and cotton in the remains of storage huts indicating their harvests produced surpluses.

A lively trade exchange developed with the east coast using networks along the Limpopo river and gold, ivory, iron, hides, salt, cattle, fish, wood, chert and ostrich eggshell beads were traded for glass beads and cotton cloth, Chinese ceramics, fish and cowrie shells with the result that the community grew more prosperous. Huffman states, “For me, long distance trade was a “prime mover” in that without it, the internal processes that led to statehood would not have begun at K2 and crystallised at Mapungubwe.”[19]

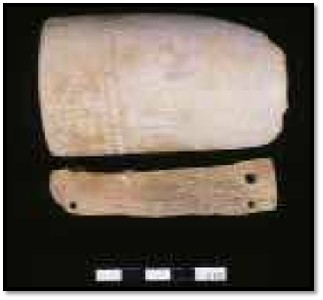

University of Pretoria: ivory from K2

Developments that grew from an evolving K2 / Leopard’s Kopje Society

With a reliable rainfall and the assurance each season of healthy crops the tradition of men herding cattle and women preparing and planting the land for crops became firmly entrenched. Society was now male dominated with a male hereditary leadership and the community developed into a rank-based social hierarchy. Villages followed a similar spatial pattern developing around a central cattle kraal; next to it was situated a court[20] with the chief, or headman’s office close by.

However at K2 itself, the home of the elite ruling class, this spatial pattern reversed with all the cattle removed from the central cattle kraal; a move that signalled that all the tribe’s cattle were owned by them…the royal herd. The stage is now set for the emergence of a community that was stratified into two socio-economic classes: nobles and commoners[21] with “senior families of different lineages across the culture area formed a single bureaucratic upper class, restricting wealth, prestige and political power to themselves.”

Circa 1220 the capital moves from K2 to Mapungubwe Hill

Although K2 is only a kilometre away from Mapungubwe Hill, Huffman believes it provided the impetus for a dramatic political and spatial change to take place. “It represented an extraordinary social evolution, marked by the transition from a rank based farming community to a complex Society with class distinctions, unequal distribution of wealth and control of an international trade network, new ideas about leadership, and then expanded polity.”[22]

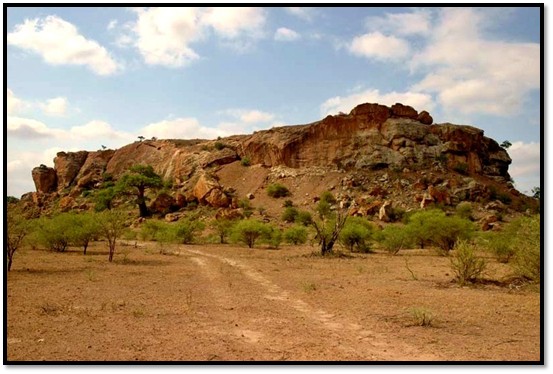

Wikipedia: Mapungubwe Hill

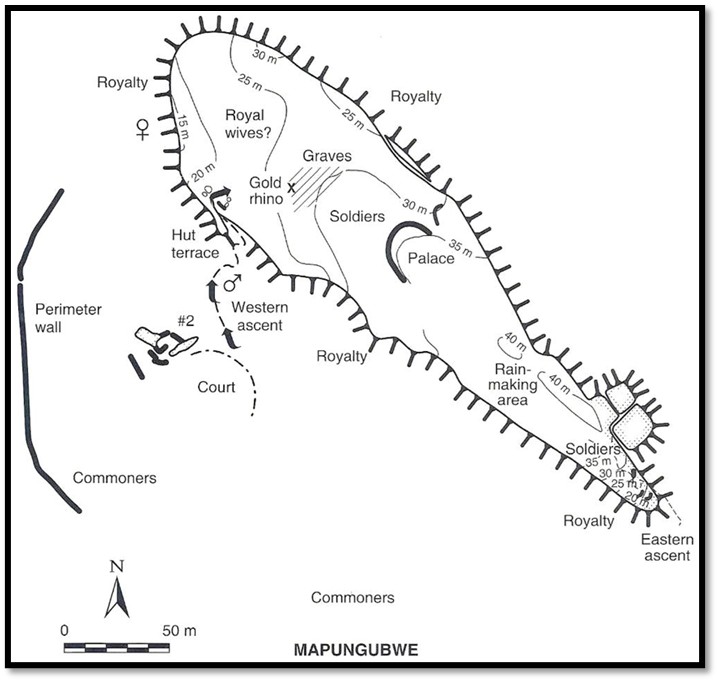

The hill itself is made up of sandstone, kidney-shaped and surrounded on all sides by steep cliffs. Although a small settlement of K2 people had previously lived on the hill, from c. 1220 only the ruling elite with their close family occupied its summit along with their court officials, including a diviner, praise singers, musicians and probably a group of palace guards.

Main and Huffman estimate the population at this time surrounding Mapungubwe probably numbered around 11,000 and more than a hundred associated village sites[23] have been identified by their distinctive pottery style in an area of approximately 30,000 square kilometres.[24] Mapungubwe itself may have had a population of 5,000 people.

The new spatial relationship at Mapungubwe between rulers and commoners

The ruling elite established on the hill, their residential structures today exposed by archaeologists, were now physically separated from the commoners…probably a completely new phenomena within southern Africa.

The court, previously close to the chief or headman’s residence, was now separated and placed with the commoners – a new spatial relationship that emphasised the class division that now existed between the ruling elite[25] and commoners. A garbage site (midden) close to K2, where commoners lived, indicates that rich and poor ate very different foods.

Huffman states this class distinction is revealed through a dual settlement pattern: commoners live in small homesteads near the agricultural lands; nobles live in special areas of district, provincial and national capitals legitimatised by the ideology of 'sacred leadership.'[26]

S. Chirikure: retaining walls of the ruler’s residence on top of Mapungubwe Hill

Huffman states the new spatial relationship involves the sacred leader with ritual brother and sister moving to a hilltop location where they are separated from the commoners. His audience chamber, reserved for his entourage and nobles, was in front of his residence along with designated places for his doctor and messenger and his ritual sister. Behind his residence was a secluded area reserved for national ceremonies such as rainmaking and the leader’s young wives. Nobles lived on the terraces of Mapungubwe Hill with their entourages and commoners in the valley below the hill and local chiefs and headmen in their own villages.

Plan of Mapungubwe (CE1220–1290) (after Huffman, 2007):

The new conception of the ruler as rainmaker through his ancestors

Prior to the first ruler taking up residence on the hill, Mapungubwe was a rainmaking site and therefore sacred. Natural cisterns, small water reservoirs, feature on Mapungubwe Hill and are found near the hill summit and are believed to have been used for water storage and ritual rainmaking purposes. They often have artificial cupules (small depressions for ritual beer) as seen below.

T.N. Huffman: Natural rock cistern with artificial cupules on Mapungubwe Hill. Sandbags are part of a rehabilitation project.

The ruler’s residence was built on the summit of Mapungubwe Hill to publicise the visibility of hierarchy with their leaders living on top of the hill while the commoners lived below. The ruler’s residence was deliberately placed directly on a rainmaking site to signify to the people that the ruler was now the rainmaker. The residence was built on a platform supported at the edges by dry-stone walls, the earliest example of the platform-type structure, later developed into a more sophisticated form at Khame.

Huffman believes siting the ruler and his family on Mapungubwe Hill in a dry-stone-walled residence was clearly done so that the commoners understood the “ritual seclusion of a sacred leader.”[27] ‘Sacred leadership’ occurred through the leader having a relationship with the land, and a related link between the leader, his ancestors and God.[28] The leader through rainmaking ceremonies would appeal to God, through his ancestors, to create rain that ensured the fertility of the land for his people. The commoners understood it that the leader’s power was partly based on his ability to appeal to God through his ancestors, and accordingly, they believed the sacred leader was appointed, or at least approved, by the ancestors.

Capitals of the Zimbabwe Culture are characterized by having the following five elements: (1) a palace, (2) court, (3) royal wives' area, (4) place for followers and (5) places for guards to ensure that the sacred leaders remained secluded.[29]

Hut floors become more sophisticated

Hut floors were made from mixed termite soil with fine decomposed granite dust and rubbed with a smooth heavy stone to consolidate the material. Often cow dung is mixed in to give a very hard surface which stands up well to day-to-day traffic.

Courtyard floors were a mix of termite soil and fire ashes upon which small fires were lit which heated the ashes within the dhaka mix and subsequently gently ‘cooked’ and baked extremely hard. This dhaka was used also in hut platforms, low walls in the open, kerbs and seats. For more detail see the article Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings; an article on their extent and meaning under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

These types of floors required more work and greater community involvement but would become the standard hallmark at later dry-stone monuments, such as Great Zimbabwe, Khame and Danangombe.

Evolution of metal-working at Mapungubwe

Chirikure gives four phases of occupation revealed by archaeology on the southern terrace of Mapungubwe Hill:

- Phase 1 (c. AD 600) was defined by the presence of Early Farming Community pottery, with a total absence of metallurgical activity.

- Phase II was contemporaneous with K2 and yielded evidence of iron and copper working. Fouché (1937) reported substantial amounts of iron slag, weapons and tools from Mapungubwe. The inventory of these weapons and tools include iron rods, arrow heads, spear blades, hoes, chisels, solid rings, an awl, spikes and wound or coiled wire bangles.[30]

- Phase III (AD 1220- 1250) is marked by the first appearance of gold and possibly bronze. The evidence for metalworking becomes more prominent.

- Phase IV, dated from (AD 1250-1290) contains metallurgical evidence identical to that of phase III, the only difference appears in the form of the gold-rich burials which were recovered from the hilltop.[31]

There is evidence for metal-working production that includes crucibles, slags and ores. There are also half-finished objects which were in the process of being fabricated, for example bangle blanks and flat gold discs. A number of finished objects were recovered from house floors, middens, as well as burial sites. However there is no evidence of large-scale iron ore production debris. According to Meyer (1998: 203), although traces of slag and ore are present on the site, remains of significant metal production activity have as yet not been found.[32] Copper and bronze processing did take place on Mapungubwe Hill. Ores, slags and prills of copper were recovered on crucibles for melting copper to produce refined metal.

Chirikure writes that bronze was highly valuable, possibly more valued than gold, necessitating the control of its production by the ruling elites which is why virtually all the bronze processing evidence was recovered from the top of Mapungubwe Hill.[33] Gold too, was a prestige metal associated with the rulers.

There are no known iron, copper or gold sources in the Mapungubwe area. The nearest goldfields are at the Tati goldfields in Botswana and the Gwanda region of south-western Zimbabwe, copper from Musina and iron from Zimbabwe. It seems all of these metals were produced elsewhere and came to Mapungubwe through trading and exchange relationships.[34]

Elite burial sites

Funeral traditions were also different between rulers and commoners. Mapungubwe is famous for the twenty-three elite burial sites that were excavated. Most were buried in the customary flexed position lying on one side, but three burials of a woman and two men were placed upright in sitting positions reserved for high status individuals. With them were a number of gold artefacts, including the famous golden rhino, a gold sceptre, a gold foil bowl and thousands of imported and gold beads. All are kept at the University of Pretoria Museum.

University of Pretoria Museum; Mapungubwe gold artefacts

Clearly these golden objects served as symbols of royal power and political leadership.

Huffman speculates the three high status individuals may represent the ruler, his ritual sister and senior brother. In Zimbabwe, many of the burials may have been destroyed through the activities of the Ancient Ruins Company around 1894.[35] The best record of these treasure-seeking activities was recorded at Danangombe (See the article Danangombe Monument (formerly Dhlo-Dhlo Ruins) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

Mapungubwe's population is thought to be the ancestors of present-day kalanga people[36] who mostly inhabit western Matabeleland in Zimbabwe, northern Botswana, and parts of the Limpopo Province in South Africa.

Here's a summary of the more obvious cultural links between Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe:

Archaeological Expression

Mapungubwe is seen as an earlier, developing site, and Great Zimbabwe is seen as a later expansion of those developments.

Social Complexity

Mapungubwe is thought to have been a centre from where social complexity developed into clear class distinctions between ruler and commoners with evidence of wide-spread trade networks and craft production. The leader chose to live at the top of Mapungubwe Hill that would have required the mobilisation of a large workforce to prepare the site before the rulers could occupy it in a secluded and private and sacred stonewalled palace that was probably established from the beginning so that the new socio-political order could be spatially expressed. The court, a predominately male area was located to the side of the palace, opposite the compound for the king’s wives.[37]

Great Zimbabwe also shows signs of social stratification with rulers on the Hill Complex within dry-stone structures built with sophisticated dry-stone construction techniques and the commoners in small villages near the places of agriculture in pole and dhaka huts.

Trade and Economy

Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe sites were involved in regional trade networks, principally with the Indian Ocean trade (AD 700 – 1500) associated with the ‘Islamic era’ and playing an important role in the gold and ivory trade on the east coast of Africa from Mogadishu to Chibuene on the southern coast of Mozambique in which local African merchants, the Swahili, played an important role. Between AD 1250 and 1330 Kilwa became the dominant player in the gold trade. Early trading may have augmented the traditional wealth in cattle. Local control of this long-distance trade may have resulted in an unequal distribution of wealth so that the ruling families became an upper class and also gained political power.[38]

Rainmaking

In traditional African culture certain individuals were thought to have a special relationship with the spirits and were active as rainmakers. It appears from the archaeological evidence that the ruler at Mapungubwe assumed the role of rainmaking through his royal ancestors, a crucial part of the social and political life of the community for ensuring good harvests and that this role continued at Great Zimbabwe and other sites in present-day Zimbabwe. This came about because the rulers claimed their ancestors could ask God on the ruler’s behalf to make sure the rains came and ensure the growth of the crops and the survival of the people.

The international trade with the east coast of Africa must have widened the range of interaction and introduced new social issues in the Shashe-Limpopo area. As social ranking intensified into class divisions, the concept of God probably developed to embrace sacred leadership.

Evolution from Mapungubwe to Great Zimbabwe

Some archaeologists have put forward the idea that the decline of Mapungubwe in the late 13th century may have led to the rise of Great Zimbabwe, where the rulers continued with the gold and ivory trade networks. However, other researchers argue that Mapungubwe may have continued for longer and the relationship between the two sites is more complex than a simple transition.

In essence, Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe are linked through their shared role in the development of indigenous states in Southern Africa, their evidence of social complexity, trade networks, and potentially, the influence of one site on the other.

Was Mapungubwe abandoned for Great Zimbabwe?

There is no definitive answer to this question. Mapungubwe may have declined in the 1100's because the climate changed[39] and the weather became colder and drier and reduced the grazing land making cattle farming difficult.[40] Or there may have been a change in the trading networks and any blow to this activity may have forced people to move away. Huffman and others give a date of AD 1290 for its abandonment.[41]

Probably there is no simple explanation. Huffman suggests that poor climatic conditions at the end of the 13th century undermined sacred leaders at Mapungubwe itself, and while vulnerable, the elite at Great Zimbabwe took over the important gold and ivory trade.[42] Others believe Kilwa’s prominence in the Indian Ocean trade redirected the gold trade northwards through Sofala, a coastal port with easier access to the gold on the Zimbabwean Plateau, rather than Chibuene, cutting Mapungubwe out of the gold trade. After the elite left Mapungubwe Hill, so did the farmers and hunter-gatherers and the site became deserted.

University of Pretoria: Gold bracelets and symbols of royal office from Mapungubwe

Mapungubwe (AD 1220–1290) and Great Zimbabwe (AD 1000–1700)

The authors Manyanga and Chirikure write that because there is just 270 kilometres between the sites many archaeologists have always “sought to establish cultural connections between them.”[43] First investigated by local farmers and prospectors in 1931 and then subject to looting and the investigations by amateurs,[44] Mapungubwe was always considered of secondary importance to Great Zimbabwe, however from further excavations in the 1980’s Mapungubwe came to be recognised as the precursor that led to the development of Great Zimbabwe. However little attention was paid to other sites, particularly in southern Matabeleland that lay between them.

In 1937 Neville Jones carried out the first archaeological excavations at Mapungubwe and concluded that the artefacts, structures and features demonstrated the Bantu character of the site and its close affinities with Great Zimbabwe. John Schofield’s (1937) analysis of ceramics also revealed close links with the Zimbabwe ceramics. Subsequent excavations and radiocarbon dating have added to the large collection of material accumulated from the site.

Great Zimbabwe

Local African communities were living around the site long before the arrival of Europeans. Probably the first European to see Great Zimbabwe was Jan Adam Renders in 1868 followed by Carl Gottlieb Mauch who saw the site in 1871 and wrongly came to the conclusion it had been built by the Queen of Sheba. (See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) Unfortunately after 1890 the site was subject to the looting of treasure seekers.

The first amateur archaeologist to work at Great Zimbabwe was Theodore Bent who, despite the excavated evidence of native artefacts and dhaka structures came to the equally wrong conclusion that the site had semitic / Phoenician origins. (See the article The Bent’s archaeological expedition to Great Zimbabwe in 1891 and the prominent part played by Mabel Bent under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

Bent was followed by Richard Nicklin Hall, the curator of the site, who carried out a disastrous excavation destroying much archaeological evidence in the process on the basis that he believed it was created by local African occupation in the recent past. This destruction continued until he was forced out of the job in 1904. (See the article Examining how the author Richard Nicklin Hall (1853-1914) justified his thesis that Zimbabwe’s gold mines were dug in ancient times by foreign miners under Masvingo Province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The first professional archaeological examination of Great Zimbabwe was carried out by David Randall-MacIver in 1905 who dug test trenches at both the Hill Complex and the Great Enclosure and came to the conclusion that Great Zimbabwe was of purely African origin, dating from about the 14th century and this view was borne out by a later archaeological study carried out by Gertrude Caton-Thompson, who gave dates of the 8-9th century for the foundations with the main occupation in the 13th century[45] and confirmed Randall-MacIver’s findings.

In all this time local communities were employed as labourers but were not encouraged to air their views on the origin and significance of Great Zimbabwe, although they continued to believe they were the traditional custodians and to view the site as a cultural shrine. The authors state, “More recently, however, we are beginning see increased efforts by anthropologists and heritage managers in making connections between Great Zimbabwe, its surroundings, and the local communities.”[46]

Which came first Mapungubwe or Great Zimbabwe?

There has been much debate over the years on which site was the likely centre of the Zimbabwe Culture. Excavations at Mapungubwe were heavily influenced by comparative ceramics and ironwork and imports such as beads and gold objects excavated at Great Zimbabwe which bore many similarities to those being excavated at Mapungubwe with the Southern Rhodesian authorities being a constant source of reference.

Radiocarbon dating brought the answers. Great Zimbabwe’s chronology has a confirmed five-phase occupational sequence as follows:

Period I (AD 100–300)

Period II (AD 300–1085),

Period III (AD 1085–1450) Main occupation, with Great Zimbabwe becoming important after AD 1290

Period IV (AD 1450–1833)

Period V (AD 1833–1900)

Radiocarbon dates confirm that the main occupation at Mapungubwe Hill (AD 1220 – 1290) pre-dates that of the main buildings in stone at Great Zimbabwe and confirms that Mapungubwe was the origin of the Zimbabwe culture and is thought to have been abandoned about AD 1290 when the ruling elites are thought to have migrated to Great Zimbabwe.[47] Following the decline of Great Zimbabwe, Khame (in western Zimbabwe) and Mutapa (in northern Zimbabwe) became the new centres of power.

Mapela Hill as a precursor of Mapungubwe

Chirikure, Manyanga et al argue that “on the basis of cultural precedence, Mapela had a fully developed Zimbabwe culture much earlier than Mapungubwe.”[48] Also, “Fundamentally, the ceramics, glass beads, chronometric and architectural evidence suggest that Mapela had fully developed attributes of the Zimbabwe culture during K2 times. Furthermore, the ideology of class distinction and sacred leadership at Mapela antedates that at K2 and Mapungubwe.”

Mapungubwe-type glass beads from the glass bead cache on the edge of a lower terrace, northern side of Mapela.

The authors give the following evidence for justifying that Mapela Hill predates Mapungubwe:

- The stone-walled terraces at Mapela have initial construction dates from the 11th century CE, almost two hundred years earlier than Mapungubwe.

- The basal levels of the Mapela terraces and hilltop contain élite solid dhaka (adobe) floors associated with K2 pottery and glass beads.

- With the hilltop and flat area showing occupation since the 11th century CE, Mapela shows evidence of class distinction and sacred leadership earlier than K2 and Mapungubwe, the supposed propagators of the Zimbabwe culture.

- Mapungubwe’s material culture only appeared later in the Mapela sequence and therefore post-dates the earliest appearance of stone walling and dhaka floors at the site.

They state, “Evidence from Mapela suggests that it was a major centre, probably four times the size of Mapungubwe Hill. The site exhibits characteristics of a hierarchical society, with evidence of economic diversification, population agglomeration, and external trade. These developments occurred 200 years earlier than Mapungubwe, prompting Chirikure et al. (2014) to consider it a possible origin of the Zimbabwe culture.”[49]

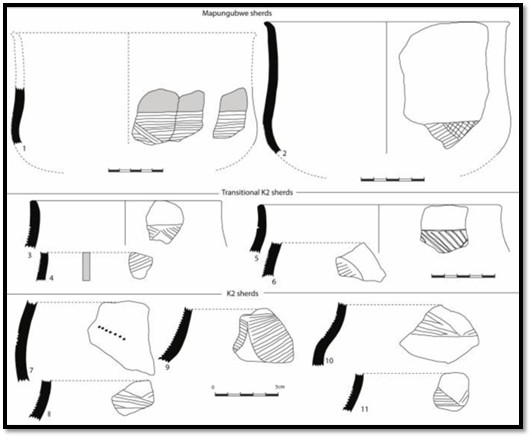

Selected K2, Transitional K2 and Mapungubwe pottery ceramics from Mapela Hill.

Huffman states K2 (Leopard’s kopje) pottery dominated the region between about 1000 and 1200 AD, while classic Mapungubwe dates between 1250 and 1300 AD. Transitional K2, fills the gap and occurs in the very upper levels of K2 and the lower occupation on the summit of Mapungubwe Hill[50]

References

T.N. Huffman. Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture. South African Archaeological Society. Goodwin Series, Vol. 8, African Naissance: The Limpopo Valley 1000 Years Ago (Dec 2000), P 14-29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3858043

T.N. Huffman. Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. Volume 28, Issue 1, P1-126 (March 2009)

T.N. Huffman. Historical archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete. KwaZulu-Natal Museum. July 2012. Southern African Humanities Vol 24, P33–59

M. Main and T.N. Huffman. Palaces of Stone, Uncovering ancient southern African kingdoms.

Struik Travel and Heritage. Cape Town 2021

Shadrick Chirikure, Munyaradzi Manyanga, A Mark Pollard, Foreman Bandama, Godfrey Mahachi, Innocent Pikirayi. Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe. PLOS ONE. 9 (10): e111224. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k1224C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0111224

South African History Online (2015), Kingdoms of Southern Africa: Mapungubwe, http://www.sahistory.org.za/kingdoms-southern-africa-mapungubwe

M. Manyanga, S. Chirikure. The Mapungubwe-Great Zimbabwe relationship in History: Implications for the evolution of studies of Socio-Political Complexity in southern Africa. January 2019. South African Archaeological Society. goodwin Series Vol 12, P72-84

Editors: Alex Schoeman, Michelle Hay et al. Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state. MISTRA Research Report. 2013

Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1099/

Wikipedia: Mapungubwe. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingdom_of_Mapungubwe

[1] Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape is one of the eight World Heritage Sites currently listed in South Africa and was listed in 2003. It is valued for a landscape that contains information on pre-colonial state formation, social hierarchies, the architecture of stone-walled towns, mineral processing and intercontinental trade

[2] Mapungubwe Cultural Landscape: https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1099/

[3] Sacred leadership implies a spiritual relationship between the rulers and the land

[4] Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[5] Van Warmelo (1940) recorded the oral traditions of local African communities, such as the Tshivhula (the senior Venda chief) and Machete (a petty chief) Mapungubwe was established by the cultural ancestors of the present-day Shona and Venda between AD 900 and 1300.

[6] Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe

[7] Palaces of Stone, P6

[8] Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe

[9] Palaces of Stone

[10] 1,150 Iron Age sites according to Huffman in Historical archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete

[11] Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state, P24

[12] Chibuene was part of the Indian Ocean trade network and is the most southerly sited port on the East African coast

[13] Marilee Wood: Glass Beads and Trade in the Western Indian Ocean. Beads at Schroda came from the Middle East, but those found at K2 came from Southeast Asia

[14] Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state, P68

[15] Leopard’s Kopje refers to Iron Age people who came from a site excavated by K.R. Robinson and T.N. Huffman near Khame ruins, west of Bulawayo. The earliest settlement dates from the 9th century AD, now called the Zhizo phase and excavation revealed the people kept goats or sheep. Large quantities of Zhizo pottery were excavated along with glass and shell beads, copper bangles, dhaka hut bases and iron slag. The area associated with the Leopard’s Kopje culture stretches down to the Limpopo River and includes Zhizo Hill, York Ranch, Leopard's Kopje, Taba Zika Mambo, Woollandale Estate Midden Mounds, Enyandeni Farm, Mapela Hill, K2, or Bambandyanalo, Khame and Mapungubwe.

[16] The UNESCO (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1099/) website refers to K2 as Leopard’s Kopje

[17] Ibid., P19

[18] Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state, P69

[19] T.N. Huffman, T.N. 2010 State formation in Southern Africa: A Reply to Kim and Kusimba. African Archaeological Review 27: P4-6

[20] Kgotla in Botswana / Dare in Mashonaland

[21] Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[22] Palaces of Stone, P32

[23] The UNESCO website (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1099/) describes Mapungubwe as developing into the largest kingdom in the sub-continent before it was abandoned in the 14th century

[24] Palaces of Stone, P33

[25] Main and Huffman call them “sacred leadership”

[26] Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[27] Palaces of Stone, P37

[28] Historical archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete

[29] Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[30] Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state, P70

[31] Mapungubwe Reconsidered: Exploring beyond the rise and decline of the Mapungubwe state, P69

[32] Ibid, P70

[33] Ibid, P73

[34] Ibid, P72

[35] The first legislation in Southern Rhodesia to bring a stop to this pillaging of ancient sites was the Ancient Relics Act of 1902

[36] Wikipedia: Mapungubwe

[37] Historical archaeology of the Mapungubwe area: Boer, Birwa, Sotho-Tswana and Machete

[38] Mapungubwe and the origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[39] The UNESCO website states unequivocally that Mapungubwe’s demise was brought about by climatic change

[40] Great Zimbabwe on the other hand is located in the high rainfall zone along Zimbabwe's south-east escarpment. If rain fell anywhere, it fell on the escarpment.

[41] Mapungubwe and the Origins of the Zimbabwe Culture

[42] Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa

[43] The Mapungubwe-Great Zimbabwe relationship in History

[44] Mapungubwe Hill was clearly well-known to the local surrounding communities long before 1931 as a sacred place, but was kept secret as required by their tradition

[45] The Mapungubwe-Great Zimbabwe relationship in History

[46] Ibid

[47] Ibid

[48] Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe.

[49] Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe.

[50] Mapungubwe and Great Zimbabwe: The origin and spread of social complexity in southern Africa