The Victoria Cross (VC) medal recipients connected with this country

The Victoria Cross is the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces and the first awards were backdated to 1854 to include the Crimean conflict. The Victoria Cross is a bronze Maltese Cross, made from the metal of two Russian guns captured at Sebastopol, in the Crimea. A scroll with the words 'For Valour' is surmounted by the Royal Crest and the ribbon is red. Behind the clasp appears the name of the recipient, and behind the cross the date of the action of bravery.

The first awards of the Victoria Cross were made by Queen Victoria to 62 recipients in 1857 in Hyde Park. In earlier years there was no provision for posthumous awards. The London Gazette would state that the person 'would have been recommended for the Victoria Cross had he survived.' Since 1902 this has changed and 291 posthumous awards have been made retrospectively to the Zulu War in 1879.

The first man to win the award was Mate (later Rear-Admiral) C. D. Lucas, Royal Navy, in the Baltic on 21/6/1854. An unexploded Russian shell lay on the deck of his ship during an engagement. He threw it overboard seconds before it exploded.

The youngest VC recipient is generally regarded as hospital apprentice Arthur Fitzgibbon, Indian Medical Establishment (15 years and 3 months) for bravery at Taku Forts in China in 1860. Boy (First Class) John Travers Cornwell won the VC posthumously at the age of 16 years in the Battle of Jutland in 1916. The oldest VC recipient was Lieutenant W. Raynor (69 years), Bengal Veteran Establishment at the 1857 Indian Mutiny.

Three men have won a bar to the Victoria Cross. They are:-

Surgeon-Capt. A. Martin-Leake, S.A. Constabulary, 1902 (S. Africa), and as a Lieutenant in the R.A.M.C., 1914 (Belgium);

Capt. N. G. Chavasse, MC, R.A.M.C., 1916 (France), and 1917 (Belgium);

2nd Lieut. C. H. Upham, N. Zealand Military Forces, 1941 (Crete), and as a Captain, 1942 (Western Desert)

The Victoria Cross can be awarded to all members of Commonwealth Forces, irrespective of rank and South Africans were eligible until the declaration of the Republic in 1961.

From 1858 to 1881 the VC could be won for acts of bravery not in the presence of the enemy, of which six awards were made. Later the British Empire Medal (BEM) and the Albert Medal, replaced in 1971 by the George Cross (GC), were awarded for this type of courage.

For much of the nineteenth century the Victoria Cross and the Distinguished Conduct Medal were virtually the only awards presented; but later other awards for bravery were made, for example, the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) Military Cross (MC) Military Medal (MM) Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) Distinguished Service Medal (DSM)

To date 1 352 Victoria Crosses have been awarded (including three bars). These are made up as follows:

Up to 1914 | 522 |

World War I | 633 |

U.S. Unknown Soldier | 1 |

Between the World Wars | 5 |

World War II | 182 |

Since World War II | 9 |

| 1,352 |

The following persons are listed by the date of the action that resulted in the award of the Victoria Cross. They either lived, or had a close connection with Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) or were attached to local military forces associated with Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and are all recipients of the Victoria Cross.

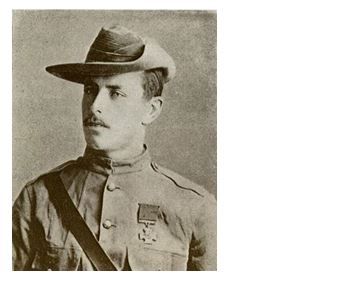

Herbert Stephen Henderson VC (1870 – 1942) was born at Hillhead, Glasgow, on the 30th March 1870. He went to school at Kelvinside Academy, Hillhead, Glasgow and served his apprenticeship with J&J Thomson Engineers, Glasgow before moving to Belfast where he worked for Harland and Wolff. In 1892 he left for South Africa and worked on the gold mines for two years before moving to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) where at 26 years old, he became the engineer of the Queen's Mine. When the Matabele rebellion broke out he joined the Bulawayo Field Force, initially as a scout, and served as a gunner in the Artillery Troop.

Henderson volunteered earlier to ride from Queen's Reef Mine to Bulawayo for help and for protection was given a revolver and one cartridge, all that was available.

Once he arrived, news was received in Bulawayo that seven white men were surrounded by the Matabele at Inyati, a post 24 kilometres north-east of the Queen's Mine and 80 kilometres north of Bulawayo. A small party of eleven men under Captain Pittendrigh of the Afrikander Corps rode out of Bulawayo just before midnight on Saturday 27th March 1896 to rescue the trapped men, first stopping at Jenkin's Store and then on to relieve Mr Graham, the Native Commissioner in Inyati.

Finding all was quiet at Jenkin's Store, the party, now increased to nineteen, rode on through the bush to relieve Mr Graham. They were riding through the Elibaini Hills when they were attacked by a strong detachment of Matabele armed with assegais and rifles. Two men were wounded before the patrol managed to throw off the attackers and made for Campbell's Store across the Bembesi, where they learned that Mr Graham, Sub-Inspector Hanley and four miners had been massacred after holding out against overwhelming odds.

As the area was swarming with warriors, mainly from the crack Ingubo Regiment, they decided to fortify the store. They had about two thousand rounds of ammunition and felt that they could withstand a night attack. Two men, Troopers Fincham and Mostert, were sent back to Bulawayo by another route for reinforcements, and got away safely to Bulawayo.

The same night, Sunday 28th March, a second stronger patrol, under the command of Captain MacFarlane, left Bulawayo to effect a rescue. Their numbers consisted of thirty horsemen; fifteen from the Afrikander Corps under Commandant van Rensburg and Captain van Niekerk and the remainder from the Rhodesia Horse volunteers.

Riding through the night with only a brief halt at Queen's Reef Mine, they pushed on to Campbell's Store. Heading the patrol as scouts and advance guards were Troopers Celliers and Henderson. In the early hours of Monday the 29th, the patrol was attacked in dense bush about 8 kilometres from Campbell's Store. The Matabele opened fire at close range, and although the darkness and thick bush favoured the Matabele, the accurate return fire from the patrol enabled them to fight their way through the ambush.

A running fire began which lasted about 30 minutes, before the patrol rode across the open veld and dashed up the river bank to the store to the relieved cheers of the besieged men. It was only then that they realised that Troopers Celliers and Henderson were missing.

Celliers and Henderson had been ahead of the main body when the Matabele sprang the ambush. Celliers was shot through the knee and his horse hit in five places. Subjected to heavy fire and cut off from the main party, the two men swung their horses off the track and headed into the dense bush. After a wild gallop lasting a few minutes they reined in their horses to hear sporadic firing above the shouting of the Matabele.

Celliers' horse finally collapsed from its wounds. Henderson dismounted, lifted the injured Celliers onto his own horse and led it away from the noise of battle. Celliers, in great pain, and suffering from loss of blood, appealed to Henderson to leave him as it would be suicidal to try to walk to Bulawayo through rough country thick with marauding bands of fierce Matabele; but Henderson refused to listen. He led the tired horse into thick bush, where he treated the injured man's wound as best he could. They had no food with them, but managed to catch some sleep although they were uncomfortably close to the Matabele.

For two days and two nights Henderson trudged through the bush leading the horse carrying his injured companion. Both were suffering from hunger and Celliers was in intense agony. Tuesday the 30th March was Henderson's birthday and he said later, that did he want to spend another birthday like that again as he weaved his way through the Matabele Impis which encircled Bulawayo.

On Wednesday morning, a bone-weary Henderson walked into Bulawayo with his horse and injured companion. Celliers had his leg amputated, but died in hospital on the 16th May 1896.

Albert Henry George Grey, 4th Earl Grey, Administrator of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) at a general parade on the 3rd June, referred in his address, to Henderson's gallant conduct and brave feat. Captain MacFarlane, the leader of the patrol, wrote a letter to the Administrator of the British South Africa Company, recommending Henderson for the award of the Victoria Cross. As all communication with Salisbury had been cut, the letter was forwarded to Cape Town and from there to London.

The award of the Victoria Cross, the first won on Rhodesian soil) to Henderson was gazetted on the 7th May 1897. The citation was drawn from the letter written by Captain MacFarlane. The London Gazette of 7th May 1897 states: “On the morning of the 30th March, 1896, just before daylight, Captain. Macfarlane's party was surprised by the natives. Troopers Celliers and Henderson, who formed part of the advanced guard, were cut off from the main body, and Celliers was shot through the knee. .His horse also was badly wounded and eventually died. Henderson then placed Celliers on his own horse, and made the best of his way to Buluwayo. The country between Campbell's Store, where they were cut off, and Bulawayo, a distance of about thirty-five miles, was full of natives fully armed, and they had, therefore, to proceed principally by night, hiding in the bush in the daytime. Celliers who was weak from loss of blood, and in great agony, asked Henderson to leave him, but he would not, and brought him in, after passing two days and one night in the veldt without food.”

Tpr Henderson was decorated with the Victoria Cross on 4 November 1897 by Sir Alfred Milner, High Commissioner for Southern Africa and Governor of the Cape Colony Milner at the opening of the Bulawayo Railway on the 4th November 1897.

Henderson remained in the gold-mining industry for some years and was, at one stage, the timber contractor to the Globe and Phoenix goldmine and later prospected for the German Administration in South West Africa. During the First World War, he was not permitted to leave Rhodesia on active service, as gold-mining was considered an essential service. In 1924 he married Helen Joan Davidson. They had two sons, Alan Stephen Accra in 1926 and Ian Montrose in 1927.

For the duration of the Second World War, Henderson had all profits from the Prince Olaf Mine given to the War Fund.

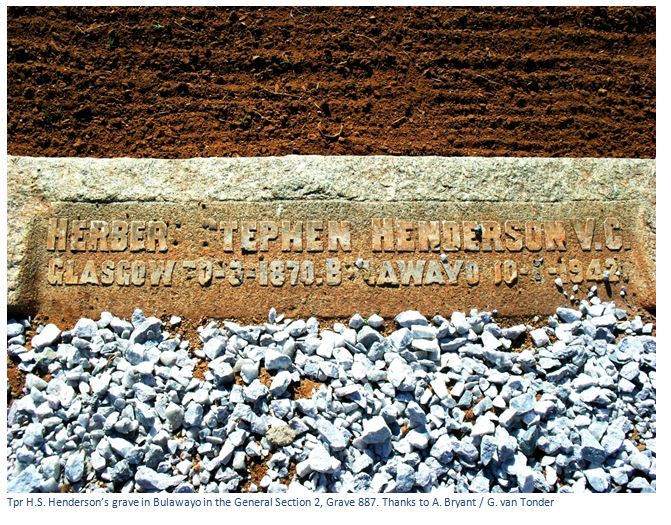

He died of a duodenal ulcer on the 10th August 1942 and is buried in the Bulawayo cemetery, his grave number is 887; his medal was donated by his family to the National Army Museum in London.

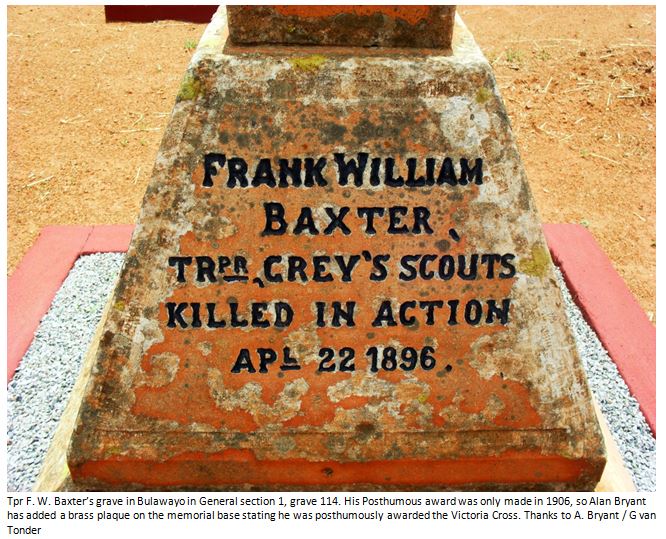

Frank William Baxter VC (1869 - 1896) was a 26 years old Trooper in the Grey’s Scouts, Bulawayo Field Force during the Matabeleland Rebellion, when on 22nd April 1896 near Umguza, Matabeleland, Rhodesia, he gave up his horse to a wounded comrade who was lagging behind, with an enemy force in hot pursuit. Baxter then tried to escape on foot, hanging on to the stirrup of another mounted scout of the Bulawayo Field Force, until he was hit in the side by enemy fire. He let go of the stirrup and died moments later. He was born on 29 December, 1869 in Woolwich, London. Baxter is buried at Bulawayo Town Cemetery, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe and his medal is in the Ashcroft collection at the Imperial War Museum, London.

On 15th January 1907 the London Gazette announced that His Majesty Edward VII had approved of the Victoria Cross being delivered to the representatives of six officers and men who would have been decorated, had they survived, namely:— Lieuts. Melville and Coghill, for saving the colours at Isandhlwana; Trooper Baxter of the Bulawayo Field Force for helping a wounded comrade on 22nd April, 1896; Private Spence and Ensign Phillips for valour during the Indian Mutiny; Lieut. MacLean who distinguished himself on the Indian Frontier during 1897.

At the time of Baxter's death and of the others there was no provision in the Royal Warrant for posthumous awards. In fact the first formal indication that the provision had been authorised seems to be in the amendment dated 22nd May, 1920, over the signature of Sir Winston Churchill.

The citation for Baxter's award, in the London Gazette of 7th May, 1897, is very brief; it reads: "The late Frank William Baxter, Trooper, Bulawayo Field Force. Trooper Frank William Baxter, one of the Bulawayo Field Force, on account of his gallant conduct in having, on the 22nd April, 1896, dismounted and given up his horse to a wounded comrade, Trooper Wise, who was being closely pursued by an overwhelming force of the enemy, would have been recommended to Her Majesty for the Victoria Cross had he survived."

The reports of Capt. Bisset, who was officer commanding the force that went out that morning, to Colonel Napier which ends "I regret to have to report the death of Trooper Baxter (Grey's Scouts) and four men wounded", or the news items in the Bulawayo Chronicle of Saturday, 25th April, or in the Rhodesia Herald of Wednesday, the 29th April 1896 were very meagre.

The Croydon Advertiser of 2nd May, 1896, had this to say: "A Thornton Heath Man's Splendid Heroism. The fierce fighting at Bulawayo a few days since has brought to light a deed of devoted heroism of which every Englishman will read with pride. Cpl Wise having been severely wounded, and having had his horse shot under him, Trooper Frank William Baxter gave up his own horse to his hurt comrade, who was thus able to escape; but Baxter himself was assegai’d by the Matabele. Capt. Napier, the commander of the expeditionary force, paraded his men on the following day, and spoke feelingly of Baxter's heroism, as well he might; for, as the Daily Telegraph says, 'no finer deed of comradely devotion than his has ever been recorded'. Trooper Baxter is a son of Mrs. Baxter of 119 Bensham Manor-road, Thornton Heath, and had many friends in the neighbourhood. We offer to the bereaved family our heartfelt sympathy upon the death of one whom we are proud to call a local man. We understand that Mrs. Baxter has another son in the expedition."

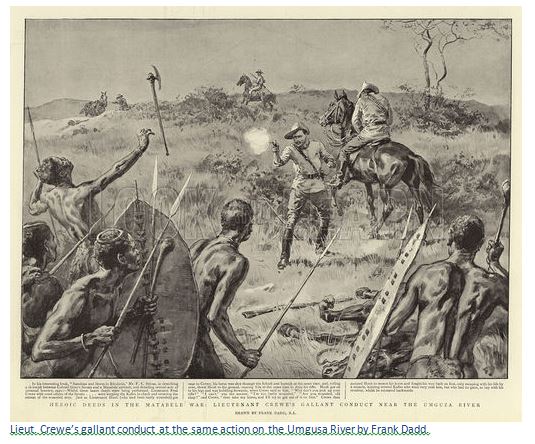

There is a stirring account of the entire action on the Umgusa River in Selous’ Sunshine and Storm in Rhodesia. Selous himself had a narrow escape when his own horse bolted; he says: “they thought they had got me, and commenced to shout out encouragingly to each other and also to make a kind of hissing noise, like the word “jee” drawn out.” At the same time he noticed he had only two cartridges left of the thirty he had started with, and was lucky to be rescued by Lieut. Windley who “like a good fellow came back to rescue me” and they gained some ground on their pursuers with Selous running alongside Windley and his horse, two bullets striking by Selous feet and another knocking the heel of Windley’s boot off.

The mounted patrol consisting of about one hundred and twenty men consisting of 20 under Capt. Grey, 40 under Capt. van Niekerk, 20 under Capt. Meikle, 20 under Capt. Brand and another 20 unattached, plus a Hotchkiss and Maxim, but the shaft on the carriage of the Hotchkiss broke and the gun was damaged and became inoperative. The lack of firepower meant they were engaged in a series of constant close quarter engagements with the Matabele until: “they were suddenly fired upon by a party of Matabele who had taken up a position amongst some bush to the left of their line of retreat. The foremost amongst the Scouts galloped past this ambush, but Capt. Grey with a few of those in the rear halted and returned the enemy’s fire. Trooper Wise was the first man hit, and seems to have received his wound from behind just as he was mounting his horse, as the bullet struck him high in the back and travelling up the shoulder blade, came out near the collar-bone. At this instant Wise’s horse stumbled, and then, recovering himself, broke away from its rider, galloping straight back into town and leaving the wounded man on the ground.

A brave fellow named Baxter at once dismounted and put Wise on his own horse, thus saving the latter’s life, but as it proved, thereby sacrificing his own. Capt. Grey and Lieut. Hook at once went to Baxter’s assistance, and that got him along as fast as they could, but the enemy had now closed upon them and were firing out of the bush at very close quarters. Lieut. Hook was shot from behind, the bullet entering the right buttock and coming out near the groin, but most luckily severing the sciatic nerve, just missing both the thigh bone and the femoral artery. Nearly at the same time too, a bullet just grazed Capt. Grey’s forehead, half-stunning him for an instant. “Texas” Long, a well-known member of the Scouts, then went to Baxter’s assistance, and was helping him along, when a bullet struck the dismounted man in the side, and he at once let go of Long’s stirrup leather and fell to the ground. No further assistance was then possible, and poor Baxter was killed immediately afterwards.

Whilst these brave deeds were being performed, Lieut. Fred Crewe, with some of the other Scouts, amongst whom I may mention Button and Radermayer, were keeping the enemy in check and covering the retreat of the wounded men. Just as Lieut. Hook got near to Crewe, his horse was shot through the fetlock and buttock at the same time, and rolling over, through Hook to the ground, causing him at the same time to drop his rifle. Hook got on his legs and was hobbling forwards when Crewe said to him. “Why don’t you pick up your rifle?” “I can’t” was the answer, “I’m too badly wounded.” “Are you wounded, old Chap” said Crewe, “then take my horse and I’ll try and get out on foot.” Crewe then assisted Hook to mount his horse, and fought his way back on foot, only escaping with his life by a miracle, keeping several Matabele who were very near him, but who had no guns, at bay with his revolver, whilst he retreated backwards. So near were these men to him, that one of them, as he turned, threw a heavy knobkerrie at him, which struck him a severe blow in the back. Nothing could have saved him had not the enemy been constantly kept in check by the steady fire of Radermayer, button, Jack Stuart and others of the Scouts, and also by crossfire from some of the Colonial Boys, directed by Capt. Fynn and Lieut. Mullins.”

Baxter’s remains were only recovered over ten weeks later on the 4th July 1896 when they were interred with full military honours. Many men were very brave that day in the face of very organised and violent opposition as Selous’ account recalls. C. L. Norris Newman who wrote Matabeleland and how we got it and who seems to have been Reuter's Special Commissioner in Bulawayo during the early part of the Rebellion left for the United Kingdom a day or two after Baxter's funeral and they were probably his newspaper accounts which were published in the Croydon papers.

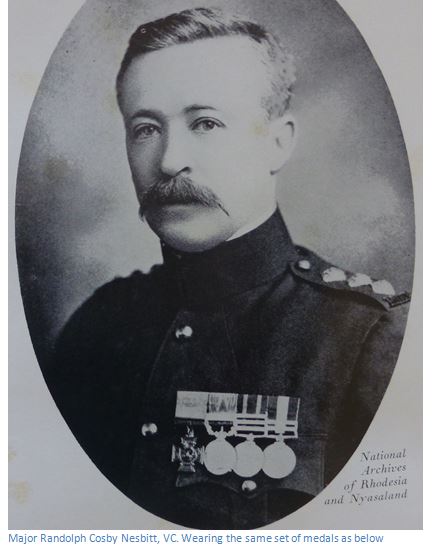

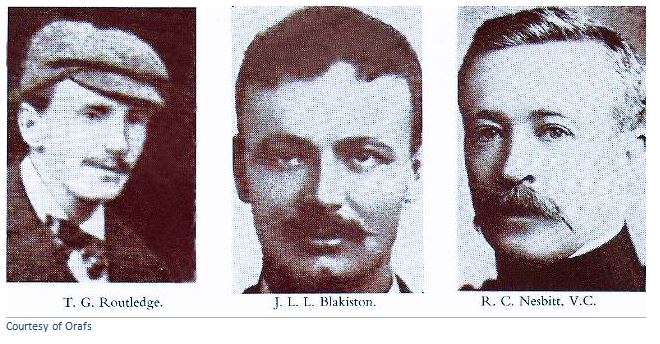

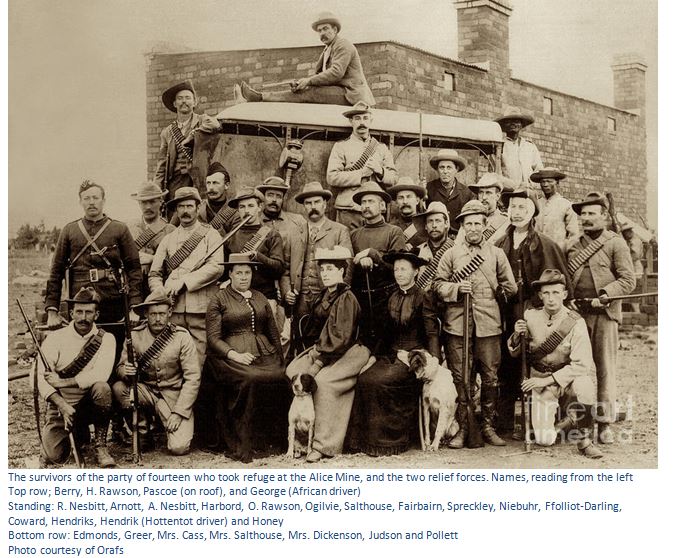

Randolph Cosby Nesbitt VC (1867 – 1956) was serving as a Captain with the Mashonaland Mounted Police (Reg. No. 920) forerunner of the British South Africa Police and later the BSA Police, during the Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga, when on 19 June 1896 he led a patrol consisting of only 13 men to the rescue of the Salthouse’s group of miners and three women at the Alice Mine in the Mazowe Valley, which was besieged by Shona tribesman. Nesbitt, Blakiston, Routledge and Pascoe were the four main leaders and instigators of the rescue.

His VC medal citation in the London Gazette, issue 26850, dated 7 May 1897 states that Capt. Nesbitt and his patrol fought their way through to the laager and succeeded in getting the beleaguered party (including three women) back to Salisbury, in spite of heavy fighting in which three of the small rescue party were killed and five wounded and fifteen horses killed and wounded.

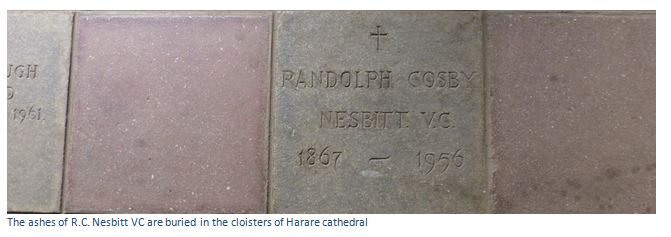

Born on 20th September 1867 at Queenstown, Cape Colony, South Africa, Nesbitt later achieved the rank of Major and served during the Boer War (1899-1902). He then became a Native Commissioner and served in the Goromonzi district at Warrendale Farm Police Camp for many years during which time he owned Bain’s Hope Farm in the Enterprise Valley, west of Goromonzi village. He died aged 88, on 23 July 1956 in Cape Town and his ashes are interred in the cloisters of the Harare Anglican Cathedral and his medal is held at the National Archives of Zimbabwe.

Left to right:

(1) Victoria Cross

(2) BSA Company medal with bars for 1890, 1896 and 1897

(3) Queens South Africa medal (QSA) with bars for Transvaal, Relief of Mafeking and Rhodesia

(4) Kings South Africa medal (KSA) with bars for 1901 and 1902

Left to right:

(1) Queen Elizabeth II Coronation medal (1953)

(2) King George VI Coronation medal (1937)

Randolph Cosby Nesbitt’s medals are stored at the National Archives of Zimbabwe and the above photos were taken in 2012 by the Chairman of the Zimbabwe Medal Society, Tim Rolfe, and scanned by Brent Barber.

The following is an account by Hugh Pollett who came out to this country about 1894 and was about twenty years old at the time of the Mashona uprising / First Chimurenga. Initially engaged in mining in the Mazowe area, he later became a stockbroker and wrote his account in Rhodesiana No 2 in 1957. I have included much more of his account than just Nesbitt’s contribution to give a fuller description of the perils they faced.

Great concern had been felt by the Salisbury population who had been informed through the telegraph office at Mazowe that fourteen men and three women were in a laager at the Alice Mine. Initially a wagon was sent out with Blakiston and Zimmerman, later changed his name to Harold Rawson, to bring in the women and no opposition was encountered on the road through the Tatagura valley.

Messrs. Dickenson, Cass, Faull, Pascoe, Fairbairn and Stoddart took with them two donkeys, a cart and 14 Mashona carriers, to be followed later by a second party with the wagon. All went well until they were about three miles from the Mazoe Camp, here the natives started firing at them, and to quote Mr. Fairbairn's report on seeing some boys striking something on the ground with their knobkerries one of their carriers was sent to see what it was and he returned saying—"Fundissi is felie" meaning "Missionary Cass is dead". Immediately after this Dickenson was shot dead, several more rebels appeared on the ridge a short distance off and on the remaining four men opening fire, the 14 carriers threw down their loads and disappeared.

The party then decided to go back to the Camp, but scarcely had they turned their cart than Faull who was driving, was shot through the heart by a native concealed in the grass, who was shot almost instantly by Fairbairn. One of the donkeys was shot which compelled them to leave the cart and make the rest of their way on foot. They soon met the van containing three women and accompanied by the rest of the men, who on hearing the news, decided to return at once to the laager at the Mazoe Camp. Before reaching their destination they were fired at from all sides and no less than 50 natives came out of the grass quite close to their rear and seemed for the moment intent on rushing them. However, by constantly firing and urging on the mules, they were able to reach the rough laager on the Kopje at the Camp, having lost three men killed. [Cass, Dickenson and Faull]

A desultory fire was still kept up by the natives on the laager and the women were obliged to crouch behind the rocks for shelter. Shortly after this Blakiston, who was a telegraph mechanic, but not an operator, offered to go to the Telegraph Office, a hut situated about 500 yards from the laager, if Routledge, the telegraphist, would go also and send a message to Salisbury asking for relief and describing the situation. [in fact, the direct line distance is about 2.75 kilometres]

They took a horse with them and reached the Office safely and the message flashed through to us in Salisbury was, "We are surrounded, send us help, this is our only chance, goodbye". Two minutes after sending this, both men and horse lay dead about half way between the Telegraph Office and the laager.

All through that day and night the enemy kept up a hot fire. A Matabele boy who was evidently their leader posted himself behind a rock about 400 yards off and by the way he splintered the rocks in the laager each time he fired was undoubtedly the best shot of the party. [This was probably Mhasvi, an African constable who deserted from the BSAP] He never exposed himself and all that was left for the besieged to fire at was the barrel of his rifle. He evidently had a great idea of his personality as during the evening he was heard to yell in his native tongue—"I am a Matabele, why do you leave me without tobacco?" During the night the rebels got within 150 yards of the laager and although some of them were shot, things looked terribly serious for the inmates.

Nothing, however, occurred and day at last dawned when the previous day’s tactics of the enemy were resorted to. At 2 o'clock a stir was visible amongst them all, and the Matabele boy was heard to call out to his followers to rush the laager. The besieged knew this meant one of two things, either it was immediate death to them, or that relief was near. Happily, it turned out to be the latter, as, to use their own words, under terrific fire Lieut. Judson and his men galloped up to the laager.

Hugh Pollett personal involvement begins here on the evening of the 18th June when he reported at the Volunteer Barracks to do picket duty if required, but heard a patrol was being organised for the Mazoe relief and having a good knowledge of that District through owning some mining property there, he volunteered to go and his services were accepted.

We started at 12 o'clock that night, rather indifferently mounted, though personally I could not complain as being a light weight I was given a racing pony that had been successful the week before in carrying off no less than three prizes. Altogether, there were seven of us—Lieut. Judson in command, Capt. (Honorary) Brown, Troopers Hendrikz, Carton-Coward, Honey, Neibuhr and I; not a very formidable band, but all that could be spared and horsed at the time. Nothing much of note occurred until we got to within a mile of the Salvation Army farm, where Mr. and Mrs. Cass had lived. From here we could see one of the ridges covered with natives, but as soon as they saw us they bolted into their huts and caves like a lot of scared rabbits. We kept a keen look out, however, and proceeded in skirmishing order until we reached the farm house; here we found evidence they had recently been there, by the still hot embers of a fire. We had lost our way during the night and it was now 10 o'clock in the morning and we were only 20 miles from Salisbury.

There were seven miles more to do before we got to our destination, but as men and horses were tired and hungry we decided to off-saddle here for an hour or so, to give the horses a rest and feed, and get something to eat ourselves. We found plenty of mealies for the horses and some eggs, flour and sour milk on which we made a very fair repast. We entered the house by the window and found it quite deserted, but it gave us the impression of having been left hurriedly as everything was lying about in confusion and the food was only partly consumed. There was a skinned goat hanging up under a tree which had not long been killed but we decided not to touch it for fear the natives had poisoned it and left it as bait. During this stoppage three of us were posted as vedettes (a mounted sentry) in order to guard against surprise, but with the exception of my seeing what looked like a handkerchief being waved at us, and which afterwards was found to be the corner beacon flag of a farm, nothing further occurred.

Feeling completely revived by the rest and food we started about 12 o'clock to enter the Mazoe Valley, Lieut. Judson addressed us before starting, pointed out might prove to be a veritable valley of death, one could but be struck by the strange quietness pervading everywhere. It was a most imposing sight to see those grand old granite kopjes dotted here and there, resting in the shade of the still larger and more imposing chain of mountains that run several thousand feet high and extend both sides of the valley. The sun was pouring down, the wind gently rustling in the grass and all seemed wrapped in peace and quietness. Now and then the hum of insects would be borne on the wind, or a frog could be heard croaking in the river close by—it hardly seemed possible that at any moment we might be brought face to face with an enemy of illimitable numbers and perhaps fighting for our lives. I had journeyed down the valley a good many times, but never without seeing the natives at work in their mealie fields, or other abundant signs of life around me.

We had not much time left to indulge in thought, for after going about a mile we had to enter a long stretch of very tall grass terminating in a perfect jungle in low lying ground. It was a nasty looking place and Judson gave the order to gallop. He passed through first with Brown, Neibuhr and myself following, riding in half sections, just as we were passing the thickest clump, I saw the grass and bushes move and knew in an instant what was up and a dozen shots rang out in quick succession from within six yards of the road. Before I had time to do anything my horse gave a terrible plunge and came down on his side, pitching me a good ten yards over his head. I still retained my rifle, having taken it with me out of the gun bucket in my fall. I tried three times to get up, but for the moment was unable to do so as all the breath had been knocked out of my body. At last, regaining my feet, I saw Neibuhr lying in the road bleeding profusely and both his and my horse in their last agonies of death lying within ten yards of one another. The rest of our party had not been idle and three of the enemy lay dead in the bush; Judson, who had a double-barrelled gun loaded with buck shot accounting for two of them. We had now no time to waste as the natives in front attracted by the firing were coming down from the hills trying to stop our advance, so after helping Neibuhr, who had been shot through the hand, on to Judson's horse and getting myself up behind Trooper Hendrikz we pushed on as quickly as possible. We still had six miles to go and firing was opened at us now from both sides.

Frequently, when coming to thick patches of grass or bush, we stopped to fire a volley into them and then galloped by at a smart pace; but in spite of these precautions, shot after shot would come from the enemy concealed in the grass and we had little or no chance to retaliate. We were now all impressed with the gravity of the situation and felt that our chances of reaching the Mazoe Camp were momentarily becoming less. Judson again addressed us and said if any more of us should get wounded, we would stop and take up a position on one of the kopjes where we could hold our own so long as our ammunition lasted. Fortunately, no further mishap occurred, but after we had gone about four miles, we came upon the donkey cart and the three dead bodies [Cass, Faull and ….The body of Cass had been carefully covered with grass and bushes, this respect probably being shown to him because he had acted as Missionary in that District and had a thorough knowledge of the language. We now believed it possible that all the inhabitants of the Mazoe laager had been murdered and that we were riding to our certain doom, but there was no turning back, and we decided in case we found no trace of them in the laager, we should force our way to the Telegraph Office, send a message to Salisbury and wait for relief, want of ammunition and food being our main difficulties.

Our feelings can better be imagined than described when, on reaching the last kopje that screened us from the Mazoe laager, we heard sharp firing going on and could very soon see it proceeded from the laager and was replied to from the hills surrounding it. With a cheer such as men only give under such circumstances, we galloped up to their little fort and were greeted if possible by still louder cheers from the inmates. The enemy poured a raking fire at us on our way up, but happily, with no result although the twigs were torn from the trees around and the road in places was literally cut up by the bullets.

After our arrival the firing slackened off greatly, but a strict watch had to be kept and that night we were all posted at various places in the laager and ordered on seeing anything to "first fire, then enquire". That night there were fires all around us and some were as near as 300 yards, at one time we thought they were approaching the side of our laager under cover of a large rock. Salthouse dropped a few grenades of dynamite and detonators over the side, which when exploding sounded like heavy guns going off and completely scared whatever natives may have been hanging round there. At 12 o'clock that night we held a counsel and decided to offer a Hottentot boy [Hendricks] we had with us, £100 and the best horse we had, if he would ride into Salisbury with a note to Judge Vintcent (Administrator) asking for assistance. Hendricks consented to go as soon as the moon had gone down and started off at 2 o'clock in the morning by which time it was quite dark and cold. He led his horse as far as the road and just as we supposed he had reached it we heard a shot, but were unable to form any idea as to whether it had been fired by the enemy or him.

He afterwards told us that on mounting in the road he accidentally discharged one chamber of his revolver; this, of course, gave warning to the enemy and several shots were fired at him on his way in, although none, happily, took effect, and he was able to get within 12 miles of Salisbury where he met Capt. Nesbitt and 13 more men who had been sent out to look for us. Nesbitt after reading the note decided to come on (in spite of our having asked for 40 men and a Maxim) and brought Hendricks back with him. It was about 5 o'clock in the morning we heard heavy firing going on down the valley and shortly afterwards that gallant little band of 13 men came riding round the corner having encountered no opposition until within a mile of us and, luckily, had met with no casualties.

After Nesbitt's arrival a consultation was held and it was resolved to return to Salisbury as soon as the horses had been fed and rested. The wagon, in the meantime, was made safer by two sheets of iron being placed along each side of it and this certainly saved the lives of the women as a glance afterwards at the vehicle testified. The mules, which had brought the van out, having strayed; six men were dismounted and their horses harnessed to the van. The following is the order in which we started—advance guard five mounted men and eight on foot; van drawn by six horses, containing three women, one wounded man, a driver and a whip, the rear guard men had eight on foot and seven mounted men.

I was one of the latter having been given a fresh horse. We had scarcely gone half a mile when the enemy opened a brisk fire on us from both sides and it was quite evident that they had foreseen our departure and had taken up their positions accordingly. Behind every tree and rock seemed to be posted a native and although smoke was seen proceeding from the hills and kopjes, yet seldom could we get a glimpse of the enemy. A peculiar coincidence happened in the early stages of our ride in. I was riding next to Lieut. McGeer and asked him if he would mind changing places with me, i.e. let me ride on his left instead of his right, as I could shoot better mounted that way. The poor fellow declined as he had his hands full with a very restive horse, and strange to say, five minutes after, he was shot dead, being my half section and therefore riding close to me at the time he nearly swept me out of the saddle when throwing his arms back with his last gasp.

When we got opposite the Vesuvius Mine the firing became terrific and Capt. Nesbitt and Trooper Edmonds were the first to have their horses shot under them. At this point, Pascoe got on top of the coach and did much good work by showing us the movements of the enemy and putting in many a telling shot. The kopjes and grass seemed to be alive with rebels, several of whom were mounted and these were undoubtedly directing the movements of the others. A large number of the enemy now began harassing our rear and the further we went the more we had to contend with from this quarter, until at last they got so near that we were ordered to dismount and fire three or four volleys into them, this kept them off for a bit, but they never ceased to harass the rear.

All this time the sun was pouring down and men and horses were getting thoroughly done up, several of the former were scarce able to lift their rifles to their shoulders; in fact, the whole party was getting into a pitiable plight. Volley after volley was fired into us from the grass at the road side and only the erratic and bad firing can account for the miraculous escape we had had. They were armed with all sorts of rifles, including Lee-Metfords and Martini Henry’s, but a great many had muzzle loaders into which they crammed almost anything that came handy, potlegs and even stones, as some of the missiles that were afterwards taken out of the wounded horses testify. The "footsloggers" when too tired, held on to the stirrup leathers of the mounted man and were thus able to gain a little help and the women in the van were kept busy handing ammunition out to the men whose bandoliers were exhausted. The worst had however yet to come, and at the very place where we lost our horses coming out.

Before getting there the advance guard were ordered to fire into the bush and grass where last time the enemy had hidden, but strange to say, whether they anticipated this action on our part, or whether it was by accident, they had removed themselves just about 50 yards higher up the hill and here such a fusillade met our advance guard as to completely disorganise it. Two of the men, Van Staaden and Jacobs were killed together with their horses, Burton and Hendrikz were both shot through the face, three of the horses in the van fell mortally wounded, and two more horses were killed in the rear guard. Truly it seemed to us now the Valley of Death. The grass was simply swarming with blacks and it seemed for a moment that here we must take our last stand, but the stubborn resistance offered by our men proved too uninviting for the enemy to rush us, and in less time than it takes to tell, the dead horses had been cut free, and the others gallantly pulled the van up the hill. Again, I had another narrow escape as in trying to remount my horse I saw a rebel only a few yards off placing a cartridge in his rifle which I knew was meant for me—however, as my rifle was loaded I succeeded in placing him 'hors de combat'.

In the meantime, Arnott and Hendrikz, two of the Advance Guard were cut off from us and rode into Salisbury as fast as they could, but both horses were badly wounded and eventually died. They reached the town about 5 o'clock in the afternoon. The gloom that fell upon the laager in Salisbury on receipt of their news can hardly be described. Hendrikz's face was covered with blood and that combined with Arnott's account of our position contributed to the gloom. Arnott asked for 100 men and a Maxim as he considered our party could not be rescued with less, and without this help they could never hope to see us again. After a long debate, the Defence Committee decided that it would be worse than folly to send so many men and rifles at a time when their position in Salisbury, where there were 180 women and children was getting desperate.

This decision was strongly criticised at the time, but it was a far more defensible decision than appeared at first glance, more defensible too than many other decisions arrived at by the same committee. All this time we were plodding slowly onwards and nearing the exit from the valley. A slight cessation of firing caused us to be suspicious of the enemy's movements, and soon we found out that they had altered their tactics and were making for the kopje commanding the entrance of the valley. Lieut. Ogilvie, Lieut. Judson and I, having the only three horses that were not wounded galloped on to try and reach the top of this kopje before the enemy. We succeeded by getting up the opposite side, and rather surprised some 60 or 70 natives who were coming up at the foot, by letting them have two or three volleys in quick succession.

Then, for some reason I can never quite account for, I proposed we should cheer which might perhaps make the enemy think reinforcements were at hand; anyway our own fellows with the van were so misled and took up our cheers most lustily. This had the desired effect and the natives immediately began to withdraw and thus afforded us time to get into the open country. The enemy, however, soon found their mistake and immediately pursued us again with raking fire, but finding they had to expose themselves much more now in order to get a shot at us, they very soon decided this was not the kind of warfare they liked.

A few of the more reckless spirits still kept up a desultory fire, until we got to the Gwebi River, about 12 miles from Salisbury. Here we off-saddled for a time but a false alarm caused by a troop of sesabi [tsessebe] buck coming through the grass induced us to push on to Salisbury where we ultimately arrived at 10.30 that night. We had had 12 1/2 hours incessant fighting and lost three men killed, five wounded and 11 horses, besides a foal that had followed its mother out there and two dogs.

When we arrived the whole town was in laager, and of course, the first sign of life we stumbled against was one of the pickets, on hearing who we were, his excitement was so great that he rushed towards the laager with the news. The main guard seeing him run in, gave the alarm and in a moment everyone knew the pickets were coming in. As we drew near, the whole wall of the laager presented one long line of rifles; but fortunately the picket soon made himself understood and such was the excitement at the moment that I do not think he was even censured for his conduct. By the time we arrived at the laager gates every man, woman and child in the place had turned out to do us honour and we were greeted to use Mr. Salthouse's words "as men and women might be who returned from the dead".

Eight men had been killed outright, and six wounded. Six mules, two donkeys, and eleven horses were killed, while most of the remaining horses were wounded.

As seen from the photograph above; R.C. Nesbitt was the only member of the military, the rest were civilian volunteers and although many brave deeds were done, they were not eligible for the award of the Victoria Cross.

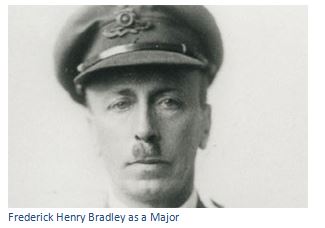

Frederick Henry Bradley VC (1876 – 1943) was born 27 September 1870, at 5 Huntingdon Street, Kingsland, London, son of Edward Thomas Bradley, of Barnet and served in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899 to 1902. Then a driver in the Royal Field Artillery, 69th Battery, he displayed great gallantry at Itala, Zululand. On the 26th September, 1901, sixteen hundred Boers attacked in the early morning, but Major Chapman and his little garrison of mostly Mounted Infantry made a spirited defence against Botha and held their ground for nineteen hours,. Lieutenant Kane, of the South Lancashire’s died at his post, shouting: "No surrender, men!" and although they suffered heavy casualties, they kept their position against overwhelming odds.

During the fight ammunition ran short at the top of a steep hill, 140 metres from the main body, and Major Chapman, of the Dublin Fusiliers, called for volunteers to carry some up across a space that was swept by Maxim machine guns. It was then that Driver Bradley won the Victoria Cross, and Driver Lancashire and Gunners Bull, Rabb and Boddy the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Bradley's Victoria Cross was gazetted 27 December 1901: "H G Bradley, Driver, Royal Field Artillery. Date of Act of Bravery: 20 September 1901. During the action at Itala, Zululand, on the 26th September 1901, Major Chapman called for volunteers to carry ammunition up the hill; to do this a space of about 150 yards, swept by a heavy cross-fire, had to be crossed. Driver Lancashire and Gunner Bull at once came forward and started, but half-way across Driver Lancashire fell wounded; Driver Bradley and Gunner Bull, without a moment's hesitation, ran out and caught Driver Lancashire up, and Gunner Rabb carried him under cover, the ground being swept by bullets the whole time. Driver Bradley then, with the aid of Gunner Boddy, succeeded in getting the ammunition up the hill". He was promoted to Bombardier, received the Queen's Medal with five clasps, and the King's Medal with two clasps. His Victoria Cross was presented to him by Lord Kitchener at Pretoria on Peace Thanksgiving Day.

For the following I am indebted to various correspondents on the website www.victorianwars.com discussing the various initials for Major Bradley. He was born Frank George Bradley on the 27th September 1876, joining the Royal Field Artillery with the names Frank George on the 12th March 1894; his Attestation Papers give his number as 3015; his Boer War Medals give his number as 3105. (QSA 3105 DVR FG BRADLEY VC 69th BTY RFA and his KSA as 3105 BOMB FG BRADLEY RFA) so it is assumed that his official number was actually 3105.

He served with the colours from 12th March 1894 to the 11th March 1906; on the 20th March 1906 he joined the Transvaal Mounted Rifles and Central South African Railway Volunteers. During 1906 he changed his forenames from Frank George to Frederick Henry; his Natal Rebellion Medal with clasp 1906 is impressed FH BRADLEY VC TRANSVAL MTD RIFLES. The remainder of his medal are all impressed with FH BRADLEY

In 1907 he married Florence Hamblin Hillary of Natal, having two sons Arthur and Elton and left the South African Defence Force in 1908, but re-enlisted on the 7th January 1910, serving with the Defence Force until 1915 when he came back to England. He was made temporary Lieut. in the Royal Field Artillery on 26th October 1915 and acting Capt. on 3rd October 1916. On 1st Sept 1916, he was transferred to the Royal Engineers Special Brigade, responsible for chemical warfare, as second in charge of No 4 Special (Mortar) Coy. The Company was part of 5th Battalion Special Brigade responsible for all the 4 inch Stokes Mortar work within the Brigade and was largely manned by Royal Field Artillery personnel compulsorily transferred to the Specials in early 1916.

He served throughout the 1916 Somme offensive, but on 18.11.16 he was badly concussed by the detonation of a high explosive shell at Delville Wood. Diagnosed with shell shock, he returned to the UK for further treatment. He was later returned to his unit, but the symptoms reappeared, and he resigned his commission due to ill-health on 12th July 1917 before going back to South Africa to recover from his wounds.

Post-war he was treated rather badly by both the British and South African Governments. Entitled to a pension for his war injury, and desperate for the money to send his sons to a decent school, he became entangled in wrangling between both governments as to who was responsible for his pension. After a considerable time the South African government accepted responsibility for the payment and he served with the South African Defence Force until he retired in 1938.

His WW1 medal index card gives his middle name as Henry, as does his London Gazette entry for his commission mentioned above, but his VC is engraved on the reverse of the suspender DRIVER F.G. BRADLEY 69th BATTERY RFA and the reverse of the Cross is engraved 26th SEPTEMBER 1901.

Bradley was 66 years old when buried on the 11th March 1943 in grave 971 at Gweru Cemetery and his medal is in the Ashcroft collection at the Imperial War Museum, London.

William Frederick Faulds VC, MC (1895 – 1950) then 21 years old, and a Private in the 1st Battalion (Cape) of the South African Infantry Brigade was awarded eleven medals during his military career, of these, the Military Cross (MC) and that most prestigious of British military awards, the Victoria Cross (VC), were bestowed on him for conspicuous gallantry during the First World War. The VC was awarded for his actions during the Battle of Delville Wood (15-20 July 1916) and the MC for his endeavours during his unit's retreat to Marrières Wood during March of 1918.

Faulds was awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions on 18 July 1916 at Delville Wood, France, it was also the last VC awarded to a fighting soldier for a rescue attempt during the war. His citation reads: “A bombing party under Lieut Craig attempted to rush over 40 yards (37 metres) of ground which lay between the British and enemy trenches. Coming under very heavy rifle and machine gun fire the officer and the majority of the party were killed and wounded. Unable to move, Lieut Craig lay midway between the two lines of trench, the ground being quite open. In full daylight, Faulds, accompanied by two other men, climbed over the parapet, ran out, picked up the officer, and carried him back. Two days later Faulds again showed most conspicuous bravery in going out alone to bring in a wounded man, and carried him nearly half a mile to a dressing-station, subsequently rejoining his platoon. The artillery fire was so intense that stretcher-bearers and others considered that any attempt to bring in the wounded man meant certain death. This risk private Faulds faced unflinchingly, and his bravery was crowned with success. ” The SA Brigade suffered appalling casualties at Delville Wood: on 15 July it numbered 3 155, but six days later the brigade mustered a mere 720.

He won the Military Cross holding the rank of temporary Lieut., his citation reads: “In the retirement from the line east of Hendicourt, 22nd March 1918, he was commanding one of the platoons which formed the rear-guard. He handled his men most ably, and exposed himself freely. Though the enemy pressed hard, he, by his fearless and able leadership, checked them, and enabled the rest of the battalion to withdraw with slight losses. He was wounded on the 24th.”

Faulds and the exhausted SA Brigade stood and fought the advancing Germans at Marrières Wood on 24 March 1918. At 09.00 the brigade, which by then numbered only 500, sighted the field grey mass of the German advance. The South Africans, who were eventually outflanked and encircled, beat off one German assault after another. With ammunition virtually exhausted, they were finally overrun that afternoon. Fewer than a hundred of the brigade's members, the bulk of them wounded, surrendered at 16.20. Faulds was marched into captivity with his comrades. The seven-hour South African stand at the wood won vital time for the retreating Allies.

He later went on to serve in the Second World War (1939-1945) and saw active service in Italian Somaliland and Abyssinia before being commissioned as a Captain when he joined the Rhodesian forces 2nd May 1945. His death certificate records that he was living at Cranborne hostel at the time of his death on 16th August 1950 and is buried in the Pioneer Cemetery, Harare in the General Adults section (1950’s) at grave plot 2992.

His Victoria Cross was kept at the National Museum of Military History in Johannesburg, but was stolen off a display in 1994 and is still missing. Faulds's eleven awards included: the Victoria Cross, Military Cross, 1914-1915 Star, British War Medal 1914-1920, Allied Victory Medal 1914-1918 (South African issue), 1939-1945 Star, Africa Star, Defence Medal 1939-1945, War Medal 1939-1945, Africa Service Medal and King George VI Coronation Medal 1937. The Museum possessed nine of these medals which were purchased for R80, 000 and can obviously never be replaced, but the loss was perhaps not entirely futile as the insurance monies received for the stolen items have been used to help construct the Capt. W.F.Faulds VC MC Centre at the South African National Museum of Military History in Saxonwold, Johannesburg.

FREDERICK CHARLES BOOTH VC, DCM

This was written by Rod Ellis and included in this article with his permission and incorporates additional material by Mike Tucker

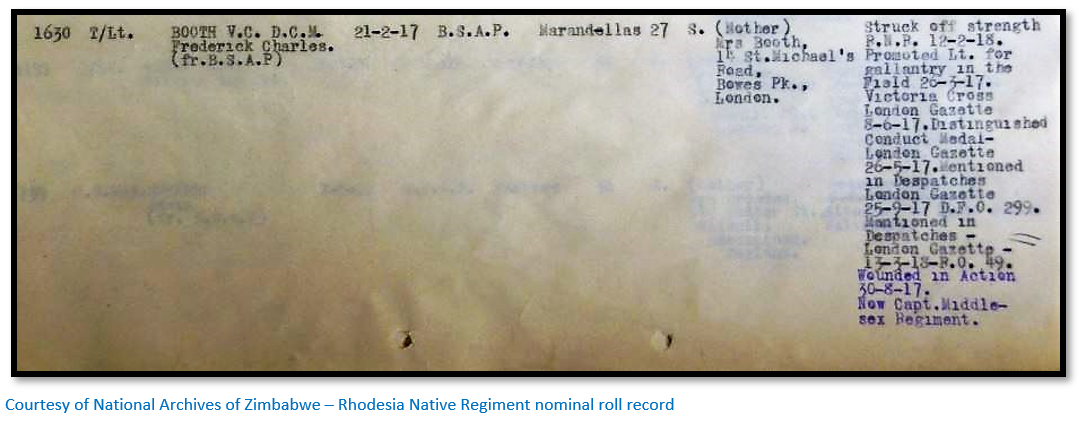

Frederick Charles Booth was the only man associated with the Rhodesian forces who was awarded a Victoria Cross as a result of actions in the Great War of 1914-1918. He was a Sergeant in the British South Africa Police attached to the Rhodesia Native Regiment when, in an action in German East Africa in February 1917, he distinguished himself to be awarded the medal for conspicuous bravery.

British South Africa Police Service

Frederick Charles Booth was born in Holloway, in the London Borough of Islington on 6th March 1890, the son of Thomas Charles Booth and Lydia Jane Booth. His father’s profession was given as Author and Journalist in the 1891 census, living in Tottenham and as a Printer and Publisher in the 1901 census, living in Enfield. Frederick was educated at Cheltenham College, an independent co-educational school, not to be confused with Cheltenham Ladies College. The school has the proud record of having produced 14 men awarded the Victoria Cross, five of them in World War 1.

Frederick Charles Booth left the UK, according to sailing records, on the Gloucester Castle leaving Southampton on 27th July 1912, bound for Algoa Bay, South Africa. (www,Ancestry.co.uk) He is reported to have travelled to Rhodesia and joined the British South Africa Police (BSAP) that same year as a trooper. He served in the British South Africa Police in Southern Rhodesia from 1912 to 1917 and his regimental number was 1630.

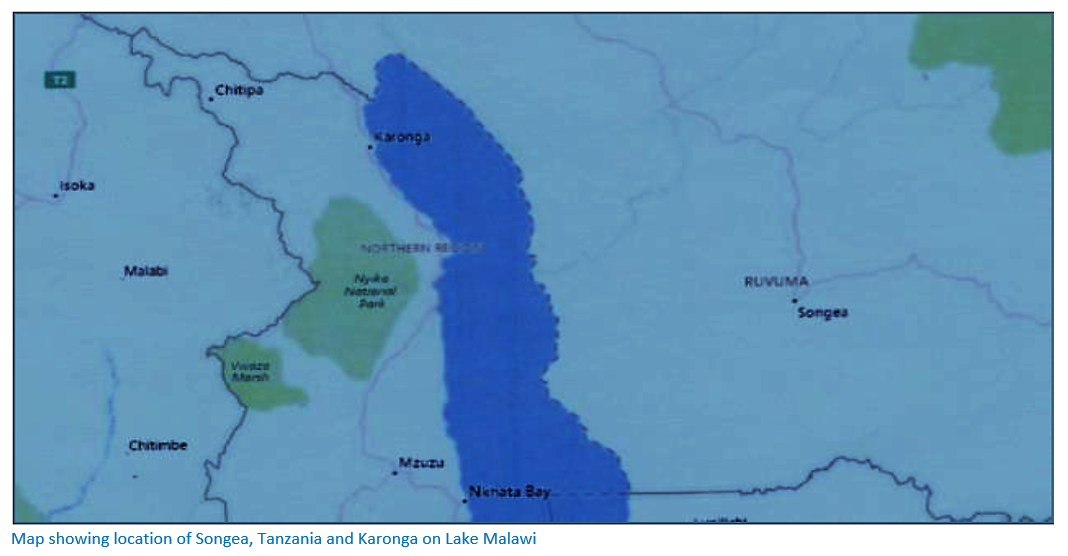

Initially Trooper Booth served in such stations as Sinoia, now Chinhoyi and Marandellas, now Marondera. In August 1914 he joined the B Company of the Special Reserves of the BSAP, later to be known as “Murray’s Column”. During one of the very first actions to take place in August 1914, Booth was involved in fighting at an outstation at Karonga, at the northern end and western shores of Lake Nyasa, Nyasaland Protectorate.

The station included a small block of offices and residences and was a depot for the Ross-Adam Trading Company. Having been alerted to the likelihood of an enemy attack, a British force made up of 500 troops together with 200 non-combatants left Fort Johnston by steamer, arriving at Karonga five days later on 22 August. After much confusion over where the enemy was actually deployed, the enemy was ejected with heavy casualties. It is notable just how early in the war this fighting took place and that, had the enemy been successful at this early stage, they may have been able to control the whole of Nyasaland.

Just over three weeks later, while serving with Colonel A. Essex Capell’s No. 1 Mobile Column to Schuckmansburg, on 16th September 1914, Trooper Frederick Booth dived into the Zambezi at Kazungula at great personal risk in order to save the life of a troop horse that had broken loose and had become caught up in some thick reeds. This deed received a Commendation in Police orders on 3rd November 1915. http://www.vconline.org.uk/frederick-c-booth-vc/4585986295

Rhodesia Native Regiment Service

In early May 1916 Booth, by then a Sergeant and 26 years old, was attached to the “Rhodesia Native Regiment” (RNR), under its original name of “The Matabele Regiment” upon this unit’s formation. His pay as a Sergeant was 180 shillings per month. After a period of training, Booth, in Major CL Carbutt’s detached No. 2 Company of the Regiment, proceeded to German East Africa (now Tanzania). The RNR formed part of General Northey’s Nyasaland-Rhodesia Field Force in this campaign. (The Outpost, October 1960 p39)

An early engagement in this campaign saw Booth and other members of the Force in action defending a British supply base at Malangali, where he received a Mention in Despatches because: “The native troops reserved their fire and took good aim, whilst the fire control generally exercised was of a high order. The maxims were most efficiently worked and were the main factors in each instance in breaking up the attack”. (http://www.kaiserscross.com/188001/389101.html)

According to Captain Marriott, the South African Commander in this engagement:” Sergeant Frederick C. Booth, a young BSAP trooper who had been involved in the seizure of a German post in the Caprivi Strip in 1914 and who would later become the most famous member of the RNR, was said to be “fearless and full of dash; he also put his whole heart into the work and was of the greatest assistance.” (Stapleton)

On 12 February 1917 at Johannesbruck, near Songea, German East Africa, Booth took part in an action for which he was awarded the Victoria Cross, gazetted in the London Gazette 8th June 1917 (Issue 30122/page 5704), the citation reading:

“No. 1630 Sjt. Frederick Charles Booth, S. Afr. Forces, attd. Rhodesia Native Regt.

For most conspicuous bravery during an attack, in thick bush, on the enemy position.

Under very heavy rifle fire, Sjt. Booth went forward alone and brought in a man who was dangerously wounded.

Later, he rallied native troops who were badly disorganised, and brought them to the firing line.

This N.C.O. has on many previous occasions displayed the greatest bravery, coolness and resource in action, and has set a splendid example of pluck, endurance and determination.”

News of this award was widely publicized in Southern Rhodesia and Booth was held up as an example of Rhodesia’s patriotism. Booth became the only soldier serving in a Southern Rhodesian unit to receive this legendary decoration in the Great War. (Stapleton) Sergeant Frederick Booth was invested with the Victoria Cross by King George V at Buckingham Palace on 16th January 1918, following his return to Great Britain after his discharge from the RNR.

Shortly after this action, the two companies of the RNR came together again and Booth achieved renown with his work at Kitanda where, on the 15th May 1917, he earned the Distinguished Conduct Medal, gazetted in the London Gazette 26th May 1917 (Issue 30095/page 5189), the citation reading:

“1630 Sjt. F. C. Booth, B.S.A. Police, attd. Rhodesia Native Regt. For conspicuous gallantry on many occasions. He showed a splendid example of courage and good leadership, inspiring confidence in his men. He twice carried despatches through the enemy lines.”

At St Moritz, a few months later, he was commissioned as a Lieutenant and is said to have been recommended for the Military Cross. He saw further action in German East Africa at Mpepo and Likassa and it was at the latter action that he was wounded through the hip and was invalided out of East Africa back to Rhodesia.

Just after the new second battalion of the RNR had left Southern Rhodesia, the wounded Lieutenant Booth VC arrived back in Salisbury to recuperate. Immediately, he became a focal point for displays of patriotism. A large crowd, including dignitaries such as the Chief Native Commissioner, Mayor, and Commandant-General, met him at the railway station. He was carried to the police camp on the shoulders of RNR and BSAP NCO’s who were led by the RNR band. A newspaper reported that: “Indeed the welcome offered to Lt. Booth was the most spontaneous and loyal that has ever been afforded any returning Rhodesian …He has won great honour for himself, his old regiment, and for the country generally.”

By contrast, Corporal Nsuga, the African soldier who saved Booth’s life, while decorated with the Military Medal, was not given any public recognition besides a short newspaper article. (Stapleton)

In October 1917 Lieutenant Booth was recommended for a permanent commission in the regular army and left in November for Britain. Just before Booth left Southern Rhodesia to join the Middlesex Regiment in England, he was presented with the Distinguished Conduct Medal for “conspicuous gallantry” in carrying messages through enemy lines.

On 13th February 1918 he was discharged from the Rhodesia Native Regiment on appointment to a permanent commission in the Middlesex Regiment with the rank of Captain, probably too late to make a mark on the European war. Booth later transferred to the Reserve of Officers, remaining thus until he reached the age of liability to recall on 16th April 1939.

Throughout his service in Africa Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM displayed exceptional courage and bravery, as witnessed by the award of the Victoria Cross and Distinguished Conduct Medal and Mentions in Despatches and Commendations. In the obituary published in the BSAP magazine of October 1960, the anonymous author writes; “Here surely, has passed away the outstanding personality of both General Northey’s Nyasa-Rhodesia Field Force and of Murray’s Column. He was “Beau Sabreur” – a dashing adventurer – to every unit he came in contact with and the tales of his audacious activities are numberless. Right from his attestation into the B.S.A. Police one finds his deeds being recorded by his fellows”. (The Outpost, October 1960 p39)

Post-War Activity

His post-war experiences seem not to have been as successful as the wartime ones. He married a wealthy widow, Dolores Pauling, in 1921. She was the widow of George Pauling, contractor to all the railways in Rhodesia. [See The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories filed under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] However, the marriage soon ran into trouble as Booth struggled with alcohol and his temper. Dolores filed for divorce on the grounds of cruelty but this was dismissed and the couple agreed to separate. He was employed in London and, after his wife died in 1938 in France, Booth received an annuity of £500 per annum and in 1941 made a claim against his wife’s estate receiving a settlement of £6,547.

After the outbreak of WW2 Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM volunteered for the Army and served with the Military Pioneer Corps in 1940 stationed in East Lancashire, and later in France.

He attended a number of commemorative events that people who were awarded the Victoria Cross were invited to, including:

• November 1929 – VC dinner at the House of Lords, hosted by the Prince of Wales

• May 1937 – At the Coronation of King George VI, he helped with organising the reception for Rhodesian Troops visiting London

• 1938 – Attended a BSAP reunion dinner as guest of honour

• 8 June 1946 – Attended VE Celebrations in London, followed by dinner at the Dorchester hotel

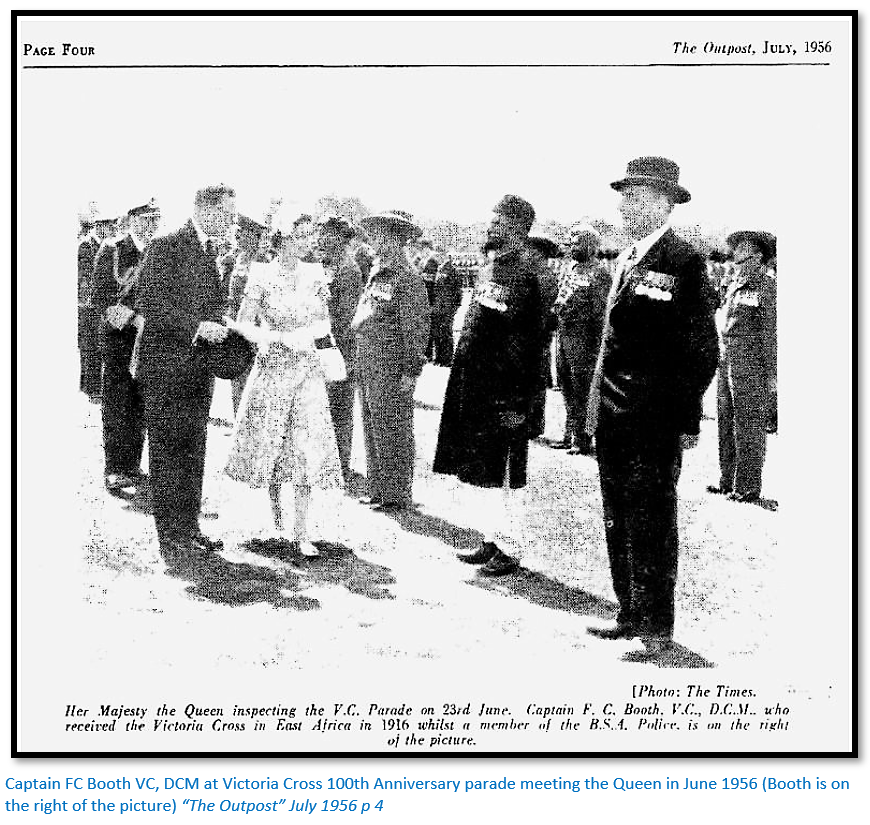

• June 1956 – Attended the VC Centenary commemoration in London, representing Rhodesia. After this occasion he wrote to the Commissioner of the BSAP, Lt-Col H. Jackson, telling of how he had spoken to the Queen about the Force and heard her say she was proud of their record. He also spoke to the Queen Mother who said she well knew of the BSAP, of their long march through the bush, and of the Rhodesia Native Regiments and the splendid fighting qualities of the Matabele and Mashona. The Queen Mother’s knowledge of Rhodesian affairs astonished Booth. “The Outpost” July 1956 p5

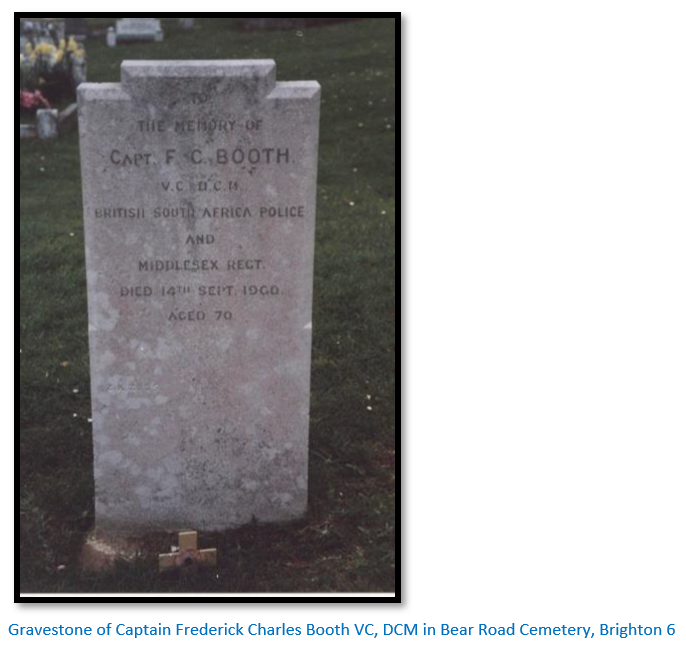

Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM died on the 14th September 1960, aged 70, at the Red Cross Convalescent Hospital for Officers, Percival Terrace, Brighton, East Sussex. He was buried five days later in the Red Cross Plot, Bear Road Cemetery, Brighton, Grave number ZKZ-36.

The mystery of the medals

The medal entitlement of Captain Frederick Charles Booth – British South Africa Police, attached to Rhodesia Native Regiment is as follows:

• Victoria Cross

• Distinguished Conduct Medal (DCM)

• 1914-15 Star

• British War Medal (1914-20)

• Victory Medal (1914-19) + Mention in Despatches Oakleaf

• King George VI Coronation Medal (1937)

• Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal (1953)

There's an indication that probably sometime in the 1930’s Frederick Booth sent his Victoria Cross and campaign medals back to the Rhodesia Native Regiment in Salisbury, Rhodesia (now Harare, Zimbabwe), the regiment with which he was serving when he won his Victoria Cross.

In an article in the “The Outpost” July 1956 p5, the author K.W.B. reports “The B.S.A. Police is singularly fortunate that Captain Booth (Sergeant BSAP; Temporary Lieutenant, Rhodesia Native Regiment, at the time of the award) has presented his Victoria Cross, together with his DCM and war medals, for perpetual safekeeping in the Sergeants Mess at Salisbury.”

This is confirmation that the medals had been returned to Rhodesia by Fredrick Booth VC, DCM. Booth’s medals were displayed in the Sgt’s Mess in the Morris Police depot, Harare until 1956, when he attended the VC parade in London with "Toys" Norton VC. Prior to attending this parade, his medals were sent from the Sgt’s Mess to the Military Attaché at Rhodesia House to be cleaned and new ribbons put on and it is known that Booth wore his medals on that parade. It was assumed that his medals were returned to the Sgt’s Mess, but this has never been confirmed. http://zimfieldguide.com/mashonaland-west/victoria-cross-vc-medal-recipients-connected-country

In 1984 the subject of a Medal Sale of December 1982 was discussed in South Africa, especially how a huge number of various medals from the former Southern Rhodesia, and Rhodesia, had come onto the market. This included a very substantial number of the British South African Police Company medal in its various forms. It was quite common knowledge within medal collecting circles that this huge number of various medals of Rhodesian origin had been acquired in the very early days of Zimbabwean independence by a man who was a former BSAP Field Reservist. The man concerned had claimed that he had obtained Booth's Victoria Cross medal group (along with many other such groups for gallantry) from a government establishment during the state of confusion in late January 1980. He had further claimed that he had sent all the valuable medals, such as Booth's, to the United Kingdom where they were held in secure circumstances.

A further report suggests that a Rhodesian medal collector, who resided in England, was in possession of the Frederick Booth Victoria Cross group from 1980 to at least 1984. (http://www.victoriacross.org.uk/bbboothf.htm)

WHERE ARE THEY NOW?

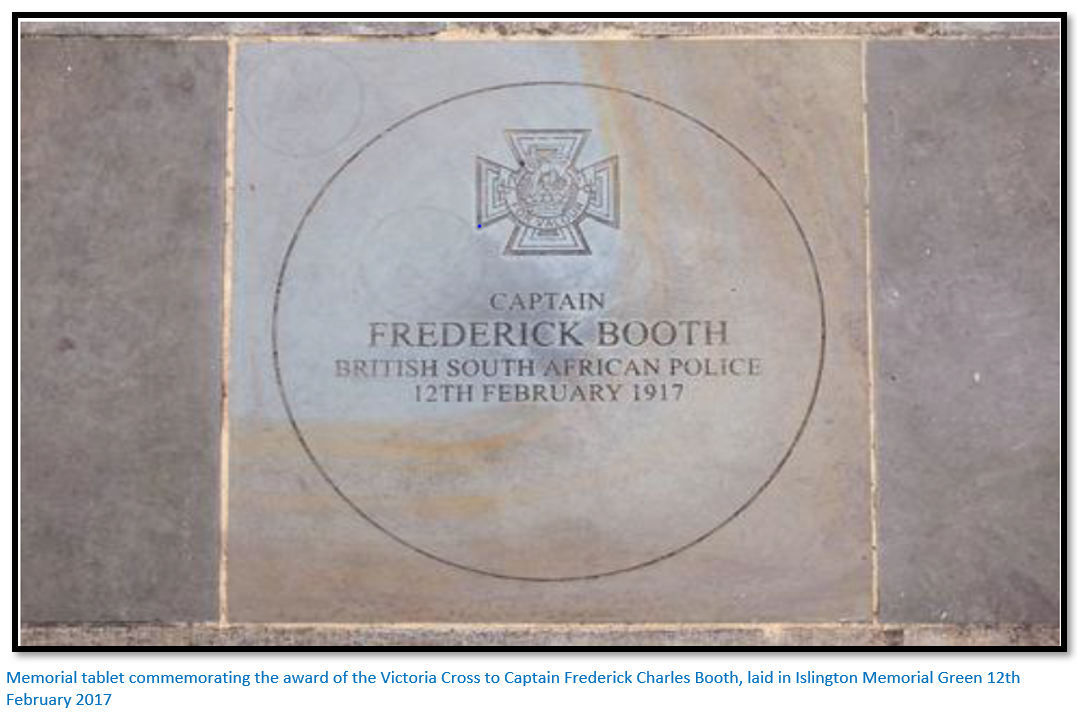

The 100th Anniversary Commemoration of the award of the VC

As part of the commemoration of the Great War, the British government provided funds for the installation of memorial tablets in the birthplace of each of the men awarded Victoria Crosses on the 100th anniversary of the event for which they were awarded the medal. The ceremony honouring Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM took place in Islington Memorial Green on 12th February 2017 with the unveiling of the memorial stone and the laying of a wreath by Cllr Gary Poole, Islington Council's Armed Forces Champion, and Deputy Mayor Cllr Una O'Halloran.

Cllr Poole said: "In an act of extreme bravery, Sgt Booth risked his own life under heavy fire to rescue a badly wounded soldier. He also managed to rally his soldiers in the heat of battle. This memorial stone is a lasting reminder of his courage 100 years ago, which is still remembered today. We must also remember that young servicemen and servicewomen still put their lives on the line every day for this country.” (http://www.islington.media/r/6455/bravery_of_victoria_cross_sergeant_is_honoured_with)

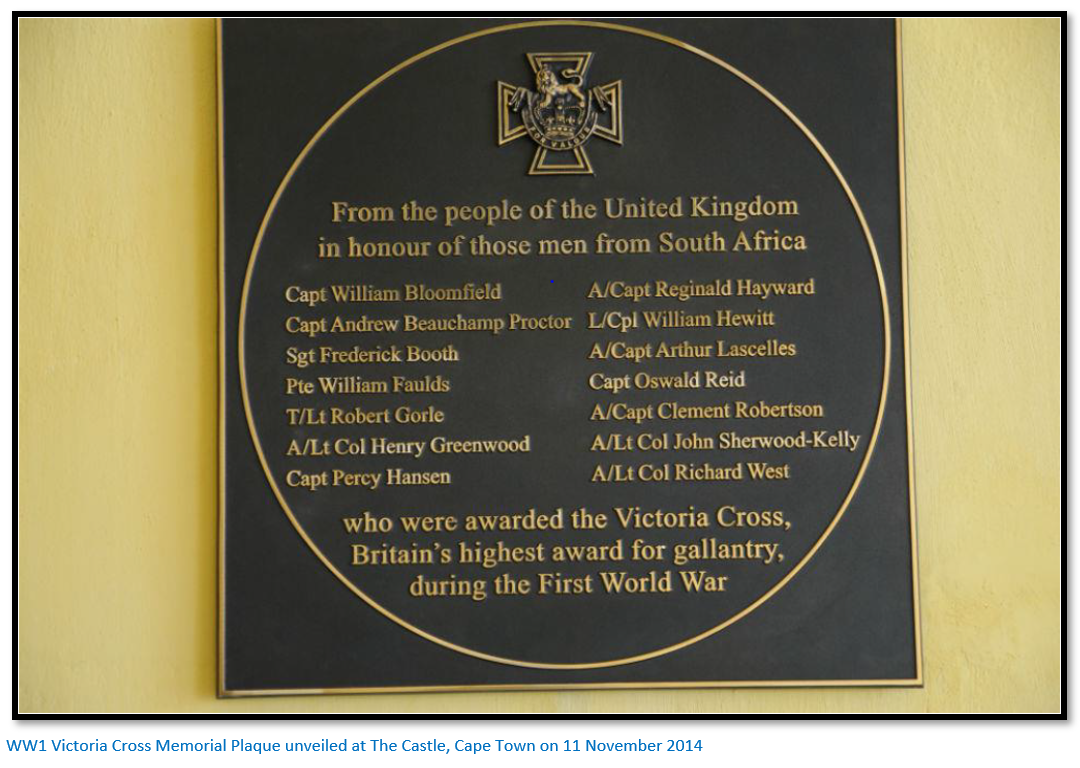

Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM also has the possibly unique distinction of having his feat recognised twice on VC Memorial tablets approximately 6000 miles apart. On 11th November 2014 (an ironic day in the circumstances and two years and three months before the 100th anniversary of Captain Booth’s event!) a tablet with his name and that of thirteen other soldiers from South Africa awarded Victoria Crosses, was unveiled at The Castle, Cape Town.

These thirteen other soldiers probably had a higher claim to South African military affiliation than Booth, who had none. Booth’s only association with South Africa had been a short journey between Algoa Bay and Salisbury, Rhodesia to join the BSAP. The plaque was sent to South Africa and unveiled by the UK High Commissioner Judith Macgregor and the South African Director General of the Department of Military Veterans Tsepe Motumi. I believe the Foreign and Colonial Office was responsible for this, thinking that Booth was a foreign soldier from South Africa and that the British South Africa Police had something to do with the Union of South Africa. Either way, the right memorial plaque was laid in Islington, Frederick Charles Booth’s birthplace but he has the bonus of two remembrances. (https://www.gov.uk/government/news/unveiling-of-wwi-victoria-cross-plaque-the-castle-cape-town)

His name is also commemorated on a VC Roll of Honour Board at Cheltenham College. The Enfield Council in London thought of Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM too as one of their Famous Five recipients because he had lived with his parents in that Borough and was recorded there in the 1901 census, aged 11. Guessing at Frederick Booth’s love of adventure and sense of fun, it’s likely that he would have been amused at the desire to own his memory by so many, as evidenced by the memorial activity.

SOURCES

1. Gerald Gliddon (2014). “VC’s of the First World War: The Sideshows” pp 32-38, published by The History Press in 2014 and available from Amazon as a book as well as a Kindle edition. This is the principal source of information for this article. In this book, Mr Gliddon relates stories of those men awarded the Victoria Cross in the war zones of the Great War apart from the engagements in Europe and Gallipoli. The latter are covered in separate volumes of the series. The life of Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM is well documented in this article.

2. “The Outpost”. The British South Africa Police United Kingdom Branch Secretary kindly provided information of issues of Outpost, the BSAP magazine, that featured articles on Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM. The following issues were relevant to this article and are quoted in the text:

a. The Outpost, July 1956, p 4 has a picture reproduced from The Times of the Queen inspecting the VC parade at the 100th Anniversary of the medal, showing Captain Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM.

b. The Outpost, July 1956 p 5 reported a letter written by Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM to the Commissioner of the BSAP, Lt-Col H Jackson relating his experiences of the VC Centenary Celebrations in June 1956.

c. The above issue also had an article describing the history of the Victoria Cross mentioning both members of the BSAP who were awarded the medal. Besides Booth the other man awarded the Victoria Cross was Inspector (later Major) RC Nesbitt who received it for gallantry and resource during the Mashonaland rebellion in 1897. The same article reported how fortunate it was that Booth had presented his Victoria Cross with his DCM and war medals, for perpetual safekeeping in the Sergeants Mess, BSAP, Salisbury.

d. The Outpost, October 1960, p 39 contained a moving obituary of Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM

3. vconline.org.uk website A complete listing of Victoria Crosses and George Crosses can be found on this website with Frederick Charles Booth’s record at this address: http://www.vconline.org.uk/frederick-c-booth-vc/4585986295

4. kaiserscross.com website. There are two excellent articles in Harry’s Africa section of this website dealing with the Rhodesian activities in German East Africa in the Great War:

a. One focuses on the activities of the British South Africa Police Special Reserve Companies of the BSAP and Southern Rhodesia’s response to German aggression on the Northern Rhodesia border: http://www.kaiserscross.com/188001/366822.html

b. The second takes up the story of the Rhodesia Native Regiment’s formation and activities in German East Africa: http://www.kaiserscross.com/188001/389101.html

5. Timothy J. Stapleton (2006). No Insignificant Part: The Rhodesia Native Regiment and the East Africa Campaign of the First World War. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada 2006. This book relates the history of the Rhodesia Native Regiment from its inception in 1916 until the conclusion of hostilities in German East Africa in 1918.

6. Victoriacross.org website http://www.victoriacross.org.uk/bbboothf.htm This website reports the medals awarded to Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM and the mystery of their disappearance from public view.

7. Zimfieldguide.com website http://zimfieldguide.com/mashonaland-west/victoria-cross-vc-medal-recipients-connected-country This website has a report on Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM and the missing medals. It also relates stories of seven other men awarded the Victoria Cross who had an association with Rhodesia and later Zimbabwe.

8. Islington Council Media centre website (2017) http://www.islington.media/r/6455/bravery_of_victoria_cross_sergeant_is_honoured_with Report of the unveiling of Memorial Stone in Islington, London, birthplace of Frederick Charles Booth VC, DCM

9. UK Government website (2014) https://www.gov.uk/government/news/unveiling-of-wwi-victoria-cross-plaque-the-castle-cape-town Report of unveiling of Victoria Cross Memorial Plaque in Cape Town, S Africa.

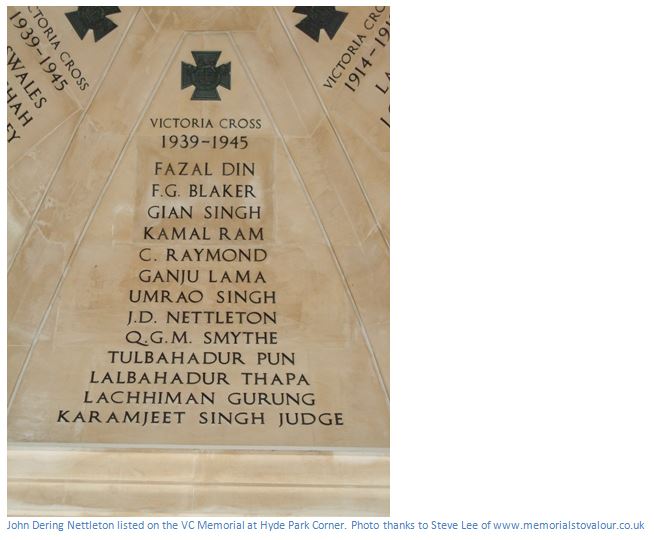

John Dering Nettleton VC (1917 – 1943) a South African, was commissioned in the RAF in December 1938, he then served with Nos. 207, 98 and 185 Squadrons before joining 44 Squadron flying the Handley Page Hampden. He took part in a daylight attack on Brest on 24 July 1941 and in a series of other bombing raids and was mentioned in dispatches in September 1940. Nettleton was promoted Flying Officer in July 1940, Flight Lieut. in February 1941 and was a Squadron Leader by July 1941. No. 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron was based at RAF Waddington, Lincolnshire at this time and had taken delivery of Avro Lancaster’s in late 1941.

In 1942 a daylight bombing mission was planned by RAF Bomber Command against the MAN diesel engine factory at Augsburg in Bavaria, responsible for the production of half of Germany’s U‑boat engines. It was to be the longest low‑level penetration so far made during World War II, and it was the first daylight mission flown by the Command’s new Avro Lancaster. Nettleton was the leader of one formation of six Avro Lancaster bombers flying Lancaster Mk I, R5508, coded "KM-B". A second flight of six Lancaster’s from No 97 Squadron based at RAF Woodhall Spa, close to Waddington, did not link up with the six Lancaster’s from 44 Qquadron as planned. When they had just crossed the French coast at low level near Dieppe, German fighters of Stab and II./JG 2 returning after intercepting a planned diversionary raid which had been organised to assist the bombers, attacked the 44 Squadron aircraft a short way inland and four Lancaster’s were shot down (7 were claimed). Nettleton continued towards the target, and his two remaining aircraft attacked the factory, bombing it amid heavy anti-aircraft fire. He survived the incident, his damaged Lancaster limping back to the UK, finally landing near Blackpool. His VC was gazetted on 24 April 1942.

Nettleton died on 13 July 1943, returning from a raid on Turin in Italy by 295 Lancaster’s. His Lancaster KM-Z (ED331) took off from Dunholme lodge and was believed to have been shot down by a fighter off the Brest peninsular. FW 190s of 1./SAGr.128 and 8./JG 2 scrambled from bases near Brest in the early hours of 13 July, and at 06:30am intercepted the bomber stream. A total of eight bombers were claimed, and at least three Lancaster’s were almost certainly shot down by the German fighters, one of whom was Nettleton’s. His body and those of his crew were never recovered and his Victoria Cross medal is not publicly held.

Nettleton Primary School is in Cranborne, Harare. A flying school was set up here in 1937 as part of Rhodesian Air Training group to train WWII pilots and from 28 November 1947 Cranborne acted as the main Southern Rhodesian Air Force base, including the Spitfire squadrons, until 1952 when New Sarum opened.

No 44 (Rhodesia) Squadron was based at Waddington from June 1937 to May 1943, equipped with the Handley Page Hampden and the Avro Lancaster, and again from August 1960 until December 1982 with Avro Vulcan Marks 1 and 2. The addition of the word (Rhodesia) on the Squadron badge reflected the contribution to the war effort by the citizens of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) during WW II.

Gerard Ross "Toys" Norton VC, MM (1915 – 2004) was a Sergeant in the Kaffrarian Rifles, South African Forces attached to the 4th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment in the Western Desert, when General Neil Ritchie ordered the precipitate withdrawal of the 8th Army from the Gazala Line in June 1942. Part of the rearguard of the 1st South African Division was cut off on the desert coast road east of Tobruk. He was posted missing, believed taken prisoner, but at the fall of Tobruk he and five comrades avoided capture by Norton and his officer friend, Lieutenant Lawrence "Bill" Baillie, who had worked for the same East London bank as Norton before the war, took over an abandoned Allied truck and, after 38 days, reached the El Alamein line, to which the routed British Eighth Army had withdrawn from Tobruk. The South African pair bluffed their way past Rommel's Italian troops by speaking Afrikaans, which the Italians mistook for German. They drove south-eastwards until after 160 kilometres their petrol ran out. Norton prepared his men for a long march and led them on an astonishing 760 kilometres trek through the desert, avoiding enemy positions and utilizing water and supplies found abandoned. After a 38 day march, he found a route through the German forward area and reached the safety of the newly formed 8th Army defence line on the Egyptian frontier. For their courage and initiative Baillie was awarded the Military Cross and Norton the Military Medal (MM).