Home >

Mashonaland West >

Thomas Baines journey to present-day Mashonaland in 1869 / 70 – background and travel by ox-wagon to Tati

Thomas Baines journey to present-day Mashonaland in 1869 / 70 – background and travel by ox-wagon to Tati

Introduction

Much of the biographic information below is from the excellent book Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, Explorer and Artist 1820-1875 written by J.P.R. Wallis, although I have used supplementary information from other sources.

This article gives an overview of his life as an explorer and artist in Southern Africa and hopefully provides an introduction to his detailed journeys that are detailed in The Northern Goldfields Diaries of Thomas Baines also edited by Wallis. The next few articles on this website will go into some detail into each of his journeys into present-day Matabeleland and Mashonaland.

In addition to being known as an explorer and artist, Baines was a competent cartographer, prospector, manager of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company’s expedition in 1869-70 and later a concessionaire.

As these articles are principally about Baines’ connection with present-day Zimbabwe, this begins with the discovery of gold by Karl Mauch just before Baines travelled to the region. Henry Hartley was guide to both Mauch and Baines, although I suspect that Baines was the more congenial travel companion!

Baines in 1869 was not a newcomer to travel expeditions. He had sailed to Cape Town in 1842 and been employed as a ‘marine and portrait’ painter before travelling in the Eastern Cape and Kaffraria as far as the Orange river in the north and the Great Kei in the east. Here he met traders and hunters and made sketches that he later worked up into canvases.

In 1850 he wanted to travel to Lake Ngami (the mysterious 'Great Lake' of the interior) with Joseph McCabe from Grahamstown, but never got much beyond the Transvaal because McCabe was jailed for treason for publishing a map of his route down the Limpopo river! The Transvaalers thought the map would open a route for a British occupying force!

On his return he was appointed artist to the forces in the 1850-53 Kaffir Wars and made a great selection of vital paintings and sketches that cemented his reputation as a painter.

In 1853 he returned to England where he remained until 1855 when he was appointed artist-storekeeper to Gregory’s Northern Australian expedition around the Victoria river, only returning in late 1857. The hope was that the region, like the territory in the south, might be gold bearing. Again he earned a reputation for practical expedients and in completing a sea voyage of 700 miles (1,127 km) for re-supplies from off Croker island to the mouth of the Albert river in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

His next expedition was a disaster as artist-storekeeper to David Livingstone’s Zambesi expedition. The details are covered in three articles on this website:

-Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-9 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone

-The Victoria Falls Zambesi River sketched on the spot by Thomas Baines F.R.G.S.

-Thomas Baines – more paintings from his Zambezi journey

Charles Livingstone, a mischief-maker and to cover up his own failings, accused Baines of theft on expedition supplies and a sick and weary David Livingstone, without examining the evidence, dismissed Baines from the expedition on 31 July 1859. Baines was cleared of theft by local missionaries, in later years David Livingstone acknowledged his brother Charles’ unreliability, but never formally cleared Baines of his earlier false charges. Most of Baines’ friends and colleagues, knew Baines as completely trustworthy and hard-working, but officialdom in the form of the Royal Geographic Society and Foreign Office were slower to accept his innocence.

In 1860 Baines met James Chapman who planned an expedition from Walvis Bay to open up the middle and lower Zambesi river to trade. James left first for the interior despite opposition to travel from local Nama people because of the onset of cattle lung sickness. Drought and cattle thieving were other obstacles.

Baines followed with Henry Chapman bringing two boats he constructed to navigate the Zambesi. Despite the diseases and hostility from local tribes they reached Lake Ngami in December 1860. Much ivory was bartered for goods. In March / April the party, now joined by Edward Barry and John Laing travelled down the Botletle river before trekking east and north to the Ntwetwe Pan reaching Gerufa on the Westbeech Road in June 1861.

From their camp on the Deka river they walked to the Victoria Falls from 22 July to 16 August 1861 and were back at Deka by month-end. Baines and Laing made a boat building camp on the Zambesi at its confluence with the Deka river at a spot he named Logier Hill after his friend Frederick Logier (1801-1867)

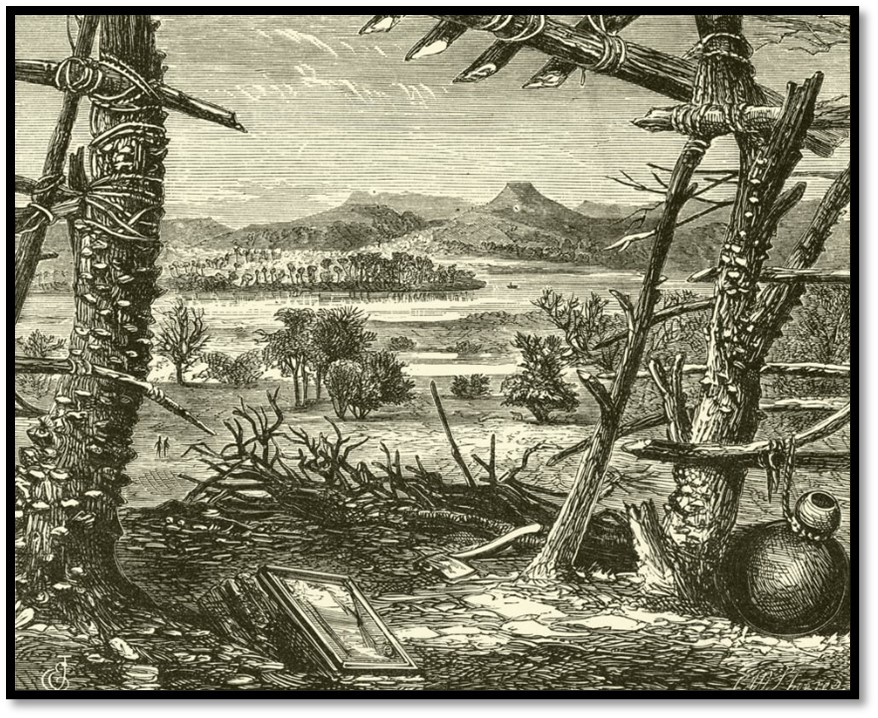

E. Jennings: The Zambesi river, from Logier’s Hill

James Chapman walked down the Matetsi river and reached Logier Hill on 18 October 1861. Chapman and Laing returned to the wagons at Deka, Baines worked on the boats, Barry looked after the wagons and oxen. Fever, semi-starvation, accidents and deaths, tsetse-fly made them give up their plan to boat down to Tete.[ia]

During the long journey from Gerufa via the Botletle river to Walvis Bay more ivory was bartered – this being the only commodity that paid for expedition expenses. Baines lingered in what was Hereroland in present-day Namibia staying with Charles John Anderson, painting over a hundred Damaraland bird studies for his host and living by painting as he waited for James Chapman to return for another expedition. But Chapman was too ill and Baines returned to Cape Town in October 1864 before leaving for England in May 1865.

The article below picks up from this time of Baines' life, but first a short section that gives a little background to the gold discoveries themselves.

Karl Mauch publicises his gold discoveries at Tati and Mashonaland

Mauch’s first journey

Karl Mauch travelled with the elephant-hunter Henry Hartley “Oud Baas” across the Limpopo into the territory of King Mzilikazi, a journey of 7½ months from 22 May 1866 to 10 January 1867. Hartley during his 1865 hunting trips in the region in 1865 had come across what he believed to be evidence of ancient mine workings in the gold-bearing quartz in the area between the Shashi and Ramaquabane rivers, afterwards called the Tati district.

Karl Mauch Henry Hartley, the famous elephant hunter

whom Karl Mauch and Thomas Baines

accompanied to Mashonaland

Mauch wrote in his diary at the time:[ib] Preoccupied with my thoughts about the future., wondering about what kind of news from home could have arrived, doubtful as to whether I would be able to repay my debts and how this could be done, contemplating in what way I could earn my daily bread in future, angry that I refused many offers that would have guaranteed a quiet life for me, recapitulating the course of my life up to the present and asking myself. “What is all this for?” - I was happily torn out of all this by the sight of an immense quartz vein between greenish schist, which rose more than six feet above the ground. “Halloh” I cried, “here must be the reward for my efforts. I shall have to come here to dig for gold.” And this decision, I actively took then and there. Having made fairly accurate acquaintance with goldfields, to the north of Mosilikatse, I certainly suspected gold and I was not disappointed. Over a width of 20 miles occurs various fine schists of grey, snowy-white and greenish colour, interspersed with smaller or larger quartz veins. I satisfied myself by taking some few gold bearing samples of quartz. I take this region as being still richer in this precious metal than the already mentioned ones. Had I not had to battle against the chief faults of the younger generation of Afrikaners of Boer extraction: laziness, ignorance and even perfidy, I would certainly have obtained up to 3 lbs [of gold] within 14 days, by simply crushing the quartz stones with the hammer.[ii]

Mauch’s second journey

The second journey lasted 8½ months from 15 March to 1 December 1867 in which Mauch accompanied Hartley on a journey into present day Mashonaland during which they confirmed the existence of still more ancient mine workings and gold deposits near the Umfuli, now Mupfure river (south-west of present Harare) called the Northern Goldfields at the time. Both Hartley and Mauch were very much guided by the evidence of old workings in potential outcrops in their search. The travellers were often offered small quantities of gold for barter by the Mashona; so they knew gold-mining had long been an activity carried out in the dry season by local people.[iii]

Again Mauch records in his journal: “on the 27th July, Hartley brought me the news that, when following a wounded elephant, he passed several pits dug into quartz and that he suspected that the former inhabitants of the country had dug for metal there, but what kind of metal he had not been able to discover. Following Hartley’s description, I should be able to reach the site from our camp in one day. And so I started the following day, armed with a hammer, to search in the indicated direction. I passed a small river at a distance of about 4½ English miles, the rubble and sand from which stemmed from ‘talk’ gneiss stone. On the other riverbank I came to a bare patch of brackish soil on which, at a distance of 1½ miles, a distinct white line across the burnt black ground could be made out. On my approach this proved to be a quartz vein which protruded in places to a height of up to 4 feet. I soon came to this line and a few paces alongside it, I came to a site which I recognised as a smelting place. This was about 10 feet in diameter and contained slag, quartz stones, pieces of clay pipes, ash and coal. There were some pits, 4 to 5 feet deep, at a distance of about 50 paces, placed in openings of the quartz vein. Yet further on there was one pit 10 feet deep, but this was filled with 2 feet of water, which probably prevented any further digging by the natives.

On examining some of the recovered stones, I found ‘Bleiganz’ which was extremely shiny and had a small silver content and gold. I looked at the extension of the vein and made speculations which, later on, proved to be correct. Highly pleased, I put my hammer into my belt, shouldered my rifle and ran, rather than walked, back to camp to impart this good news.

I returned to this locality early in the morning of the 29 of July, crossed the vein extending N 35° E In a south-eastern direction and arrived after 20 minutes at a strong flowing small river in whose sand, I discovered fine gold-like shining particles. After crossing the river, I soon found the diggings which Hartley had described to me. These are irregularly placed, first here, then there. The quartz, which appears to have been stored, is turned upside-down and is thrown about. I found a largish depression close to the river which probably was used to separate the metal during the process of washing for gold. The pits are situated in an area 2 miles in length and 1½ miles wide. A regular vein has been worked to a depth of six feet in the north-eastern part of this region, but it is again covered with so much earth that trees of seven inches thickness already grow on it. Gneiss forms the basis of this goldfield although granite occurs sometimes in the shape of boulders and then again as kopjes of 150 feet in height...”[iv]

However, because their amaNdebele guides, on Mzilikazi’s orders, watched them closely they did not dare to pick up rock samples. But an assay in England of one rock sample yielded gold worth £40.

Convinced this was an enormous goldfield, he gave details in a letter printed to The Transvaal Argus on 4 December 1867 that caused great excitement in Potchefstroom where soon every store was carrying advertisements for diggers’ clothing and mining equipment.

Thomas Baines returns to England in 1865 and tries to salvage his reputation following David Livingstone’s charges of theft against him on the Zambesi Expedition

Baines had left South Africa on 15 May 1865 following his journey with James Chapman from Walvis Bay to Lake Ngami, the Botletle river and Victoria Falls.[v] His ship, the Union mail steamer Roman endured the last of a great storm that had torn most of the ships in Table Bay from their anchorages and sunk the Athens with the loss of all on board.

He settled in Northumberland street, off the Strand, in London where he could live cheaply for about a guinea a week and renewed his friendships with staff of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS)[vi] He was still upset at the theft charges David Livingstone had laid against him on the Zambesi. He laid his case before Sir Roger Murchison, President of the RGS, gave the names of those in South Africa and England who affirmed his account and explained that the Rev D. Stewart, travelling to Nyasaland in 1862, who made an independent investigation and said the thieving had been carried out by the Doctor’s Makololo.

The accusations had a damaging effect on Baines. Captain Speke needed an artist with him on the Victoria Nyanza but feared the stories he heard about Baines. Both Murchison and H.H. Bates[vii] had ‘spoken strongly’ to the doctor, who refused to be drawn and left the country. Baines wrote to his sister that the doctor had told Bates he wished Baines no harm and “if Baines had not made a fuss of it, no one would have heard of it” with Baines writing: “as if I was going to hold my tongue and allow everyone to think he was right in calling me a thief.”[viii] Baines tried to make the Colonial Office hold an enquiry but was told in April 1860 that the minister was: “unable to interfere in the matter.”

Baines loved activity more for its own sake than for its cash returns

He read a paper on the Zambesi river in early to the Geographical and Ethnographical section of the British Association of Science (British Association) in Birmingham for which he prepared an address and two twelve-foot paintings and three smaller ones.

He continued revising the proofs of the preface to his folio volume of views of the Victoria Falls and although the publication date is given as 4 October 1865, it only appeared on 12 January 1866. Probably it is the most impressive of his publications, but the subscription list was small and it lost him money.

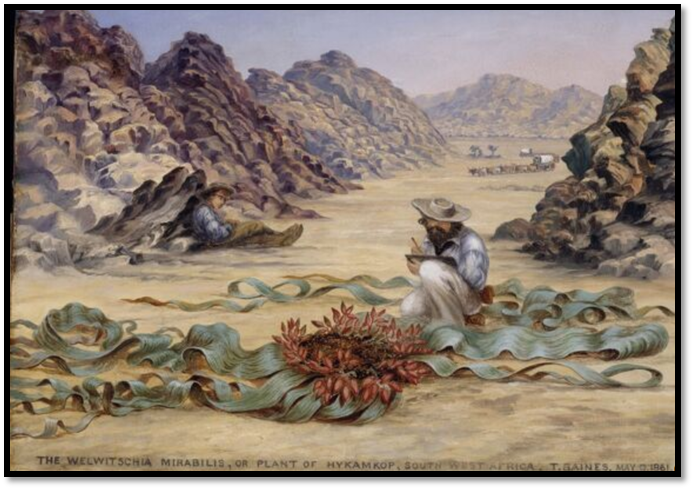

In March 1866, being in need of money he sold all his pictures, 127 or so, to Robert White, his friend from Grahamstown days for £160 saying: “it seems almost like parting with a greater part of myself.” Yet his charges were modest, 10 guineas being the usual price for a canvas and often less, like when he sold his paintings of the Welwitschia and the giant-tree aloe to Kew Gardens for £10 for the pair.

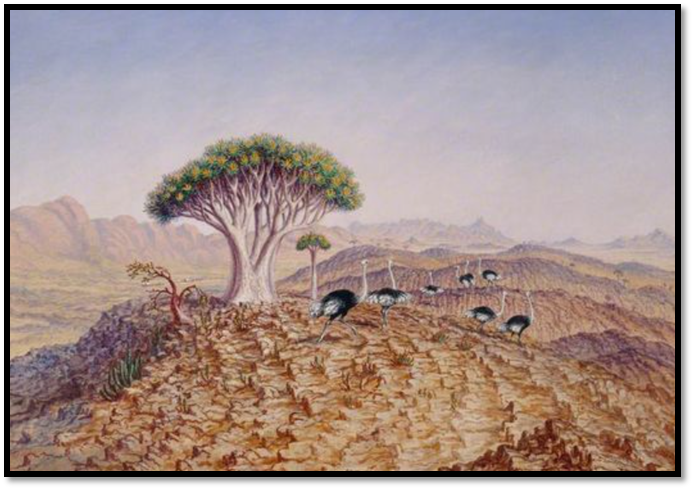

Image.Kew.org: The Welwitschia mirabilis, Nyanka Kykamkop or plant of Hykamkop or Otjitumbo Otjihooro

Image.Kew.org: The giant-tree aloe of Damaraland (Aloe dichotoma)

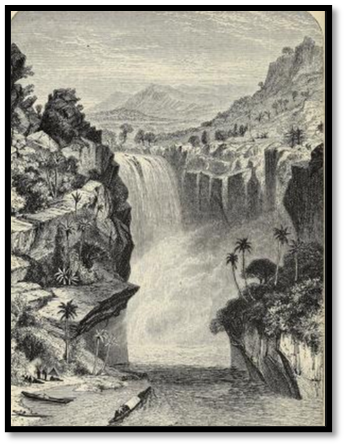

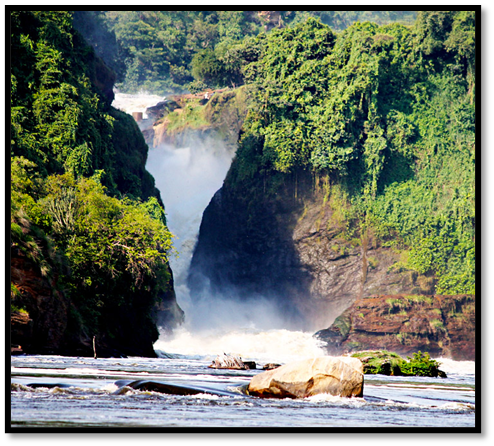

His reputation as an illustrator grew; he made two paintings of the Aru Islands for Alfred Russell Wallace and painted a picture of the Murchison Falls for Samuel Baker, recently returned from his discovery of the Albert Nyanza. Baines wrote: “He was astonished at the picture I had made from such slight materials, he said he never expected to see the Murchison falls so vividly again.” Baines also assisted Bates in editing Richard Thornton’s journals.[ix]

The Murchison falls, about 120 feet high, from the Victoria Nile to the level of Lake Albert

This is the illustration in Sir Samuel Baker’s book which may have been taken from Baines’ painting.[x]

During this time he came to know a retired Indian army officer, Captain Burslem, who was lodging in the same house as Baines. Baines fell for his daughter, Emily Burslem, a “cheerful, beautiful and accomplished” girl of 21 years and although they both seem very fond of each other nothing comes of their relationship. Her brother, Lieutenant Nathaniel Burslem and Private Thomas Lane, both won the VC for gallantry at the North Taku Fort during the Second China War but was drowned in New Zealand on 14 July 1865.[xi]

His fellow-traveller in James Chapman attacks Baines

Baines’ Explorations[xii] had been published in 1864. James Chapman's Travels in the Interior of South Africa was published in 1868, but Chapman had suffered heavy financial losses in Damaraland and was living in poverty at Cape Town. Embittered by events, Chapman wrote letters to the Cape papers and people of influence saying that Baines had broken faith by printing his book and exhibiting and selling his paintings. He accused Baines of deserting from Logier Hill just as Chapman was about to join him and ruining the Tete expedition.

Baines denied all of Chapman’s accusations; he had paid his share of expenses, the march to Tete had been abandoned due to fever and he denied he had gone as Chapman’s assistant. Chapman’s name had been published with his own name in the Victoria Falls folio[xiii] and in Explorations Chapman had been given full credit as the leader. Although vindicated, it was disheartening to be charged with false dealing after Livingston’s accusations.

Lack of money continued to be a problem

A number of expedition proposals as artist came Baines way – Thomas Valentine Robins proposed an exploring trip to Niger, Charles John Andersson planned a book on South West Africa ornithology, Francis Galton suggested a sketching tour from Somaliland to the mouth of the Senegal river, but all failed for lack of funds.

Baines wrote illustrated articles for Leisure Hour and Sunday at Home, Illustrated London News, Land and Water and Nature and Art. Through these articles he came to know an ex-artillery officer, W.B. Lord, who had travelled in Canada and Asia and proposed that should collaborate on a traveller’s handbook. Baines contributed most of the text and almost all the illustrations, some of which he did as woodcuts. The result was Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life Travel and Exploration published in 1871 by Horace Cox.

Title page of Shifts and Expedients

In August 1866 he was invited by the British Association in Nottingham to read papers on the Limpopo and the Zambesi where he exhibited his own map and gave a magic-lantern slides that proved a great success. Further lectures followed at the London Polytechnic and in Hull I January 1867 and on his return he met the veteran geologist Sir Charles Lyell who requested sketches from him. A lantern lecture to the Highgate Literary and Scientific Society and then the Pharmaceutical Society followed.

Many of his lectures cost him more than he earned including two appearances at the Working Men’s Institute in Mile End Road and for hospital patients at Victoria Park, but as he explained apologetically to his mother: “I spend a pleasant evening and make friends. Of course it costs me some trifle both in time and money, but I cannot help that.”[xiv]

Rumours of David Livingstone’s death reach England

First rumours came in March 1867. Murchison[xv] proposed a relief expedition in which Baines was happy to volunteer to serve and its proposed leader, Lieut. E.D. Young, was keen to have him. He had heard that the doctor had privately retracted his accusations, but apparently felt he should have gone public about it. Mrs Baines was not so reticent, writing to her daughter: “The doctor had very lately owned his mistake and that he was led to this by his wicked brother Charles to treat Mr Baines and all his officers as he did, and told him (Charles) that he was sorry he ever took him with him for he was the cause of all the wrong he himself had done under his base influence.”

It seemed certain that Baines would be a member of the relief expedition, until Murchison said it would be in bad taste to send Baines as Livingstone’s rescuer, and the proposal fell through as did the RGS relief expedition. Another proposed expedition from Cape Town, in which Baines hoped to be included, was also abandoned.

Baines keeps his name in the public eye

At the British Association meeting in Dundee in September 1867 Baines read a paper on Walvis Bay and the ports of South West Africa and was supported by Sir James Alexander, the first British traveller to these places.

Throughout he continued work on Shifts and Expedients writing and drawing and cutting woodblocks.

T Baines: illustration from Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life Travel and Exploration

Towards the end of 1867 the British newspapers were full of reports about Field Marshall Robert Napier’s punitive expedition to Abyssinia and the rescue of hostages from the Emperor Tewodros II of Ethiopia. Baines gave a lecture at the London Polytechnic outlining Ethiopia’s history from the time of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba which he illustrated using his own magic lantern slides. Preparation took time and the lectures paid very little, but they kept Baines’ name in the public domain.

In 1868 interest and excitement grows at the prospect of a new southern Africa goldfield

At the thirty-eighth meeting of the British Association held on 19-26 August 1868 at Norwich Professor Tennant discussed the recent discovery of diamonds in the Cape and Robert Mann, superintendent of Education and Special Commissioner of the Natal Government gave a lecture on Karl Mauch’s recent discovery of gold workings in present-day Mashonaland.

Many exploration companies were formed, Mann himself came over to assist in the flotation of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company.

Life takes a positive turn for Thomas Baines

On 5 October at Highgate he listened to another of Professor Tennant’s talks and two days later in the Haymarket examined the first two diamonds from the Cape. Before the end of the month Mann had invited Baines to take charge of a prospecting expedition in the district between the Limpopo and Zambesi rivers to evaluate its actual character and value as a gold-bearing region.

Baines managed to persuade his sceptical mother in King’s Lynn that the venture was viable as he would receive a salary as ‘general exploring superintendent and geographer’ of £200 a year.[xvi] The technical officer was C.J. Nelson, an experienced Swedish mining engineer and a young London clerk, Robert J. Jewell, would be secretary and photographer. Sir John Swinburne, chairman of the London and Limpopo Company, who had already left, would be responsible for negotiating mineral concessions with local chiefs.

Baines was in the process of completing Shifts and Expedients of Camp Life, Travel and Exploration with his co-author W.B. Lord. The first instalments were already on sale and going well, there were still a hundred woodcuts to be finished, but Baines was ready to finish them and did so with the accompanying text on the voyage to Cape Town. For once his private affairs were in good order. His mother was to draw £60 a year from his salary and his paintings were to be exhibited at Crystal Palace and as many sold as possible.

On 30 November 1865 he boarded the steamship Asia, but she was delayed and he wrote to his mother partly to hearten her at his parting[xvii] and partly a reflection of his own eternal optimism, saying on his return he would: “spend a happy and comfortable sojourn in London, working out and enjoying the fruits of his labours.” They left England on 19 December 1868, but the ship ran into a heavy gale and nearly came to grief on St Catherine’s Point off the Isle of Wight. A huge wave tore the compass out of the binnacle and while the captain tried to re-assemble it, Baines used his own pocket-compass to aid the helmsman. The storm split the sails and broke the foresail boom, a loose chain smashed the saloon skylight and the ship was forced to return to Gravesend before continuing. The rough seas continued, the cabins were constantly wet, but over Christmas Baines and Jewell lightened the atmosphere with songs and choruses although the lady playing the piano had to be lashed to her stool as the ship rolled so much, but Baines’: “quiet sociability, his knowledge of the sea and his resourcefulness made him popular with his fellow passengers.”[xviii]

Journey to Mashonaland begins

The Asia reached Table Bay on 30 January 1867, Baines: “glad see the grand old mountain again, and to be at anchor in the quiet bay.” Welcomed by old friends, he found time to visit James Chapman, whose health was poor and they parted friends once more.

Cape Provincial Administration – late afternoon view of Table Bay and Mountain, a favourite painting subject for Baines

Old friends were visited again at Port Elizabeth before the ship dropped anchor at Durban on 14 February 1869. As soon as he was ashore he revisited his aunt, now widowed and re-married as Mrs A.M. Watson. The local agent of the South African Goldfields Exploration Company, Carl Behrens, met him as did a group of Australian miners who were disappointed to hear the discoveries were far inland and that Baines had little new information for them. They threatened to wreck the offices of the Natal Witness, but troops were called in and most left for Australia.

Mining supplies were bought at Durban and sent to Maritzburg (present-day Pietermaritzburg) where the wagon awaited. Swinburne had taken six wagons to the Tati goldfields carrying a quartz-crusher and steam engine to drive it. He had crossed the Drakensberg mountains via Van Reenen’s Pass and then through Harrismith and Potchefstroom. Baines thought the better route was via Pretoria and north through the Zoutpansberg.

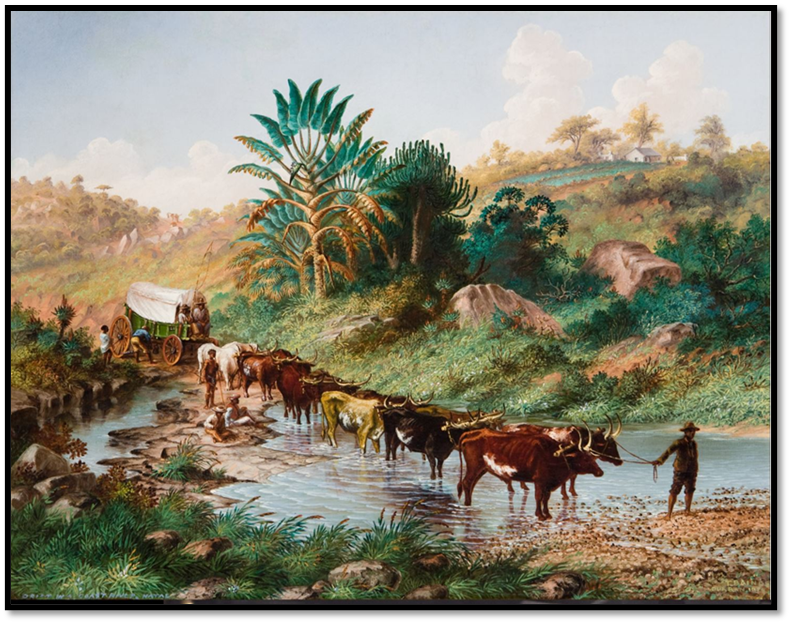

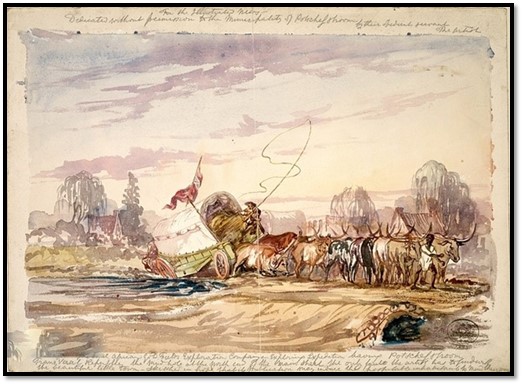

Thomas Baines: A Cape-wagon fording a river near Durban

On 25 February he set out for Maritzburg in what was called an omnibus but was in fact a light spring wagon drawn by four horses. The road, a rough track, twisted around the hills with the passengers asked to dismount and walk at the steep descents. Swinburne had brought out a ‘tractor’ to haul wagons up the steep gradients – Baines had tried to dissuade him; now it lay derelict by the side of the road until sugar-growers bought it to haul loads of cane.

Preparations at Maritzburg

At the town his wagon, sixteen oxen and three horses waited.[xix] Servants had to be hired and a decision made on the inland route. Baines had interviews with government officials including Theophilus Shepherd who introduced him to the Lieutenant-Governor, Robert Keate who asked Baines to keep him informed of the expeditions findings – almost nothing was known by the Natal administration and in return, was given an official letter recommending Baines to the native chiefs along the route.

Baines hoped that St. Vincent William Erskine,[xx] son of the Colonial Secretary would join as interpreter, but he was elsewhere at the time and Baines recruited his cousin, William Watson, who was fluent in Zulu and a blacksmith and handyman. A native herbalist (Nganga) wishing to return home beyond the Limpopo river was also recruited, Baines was delighted.

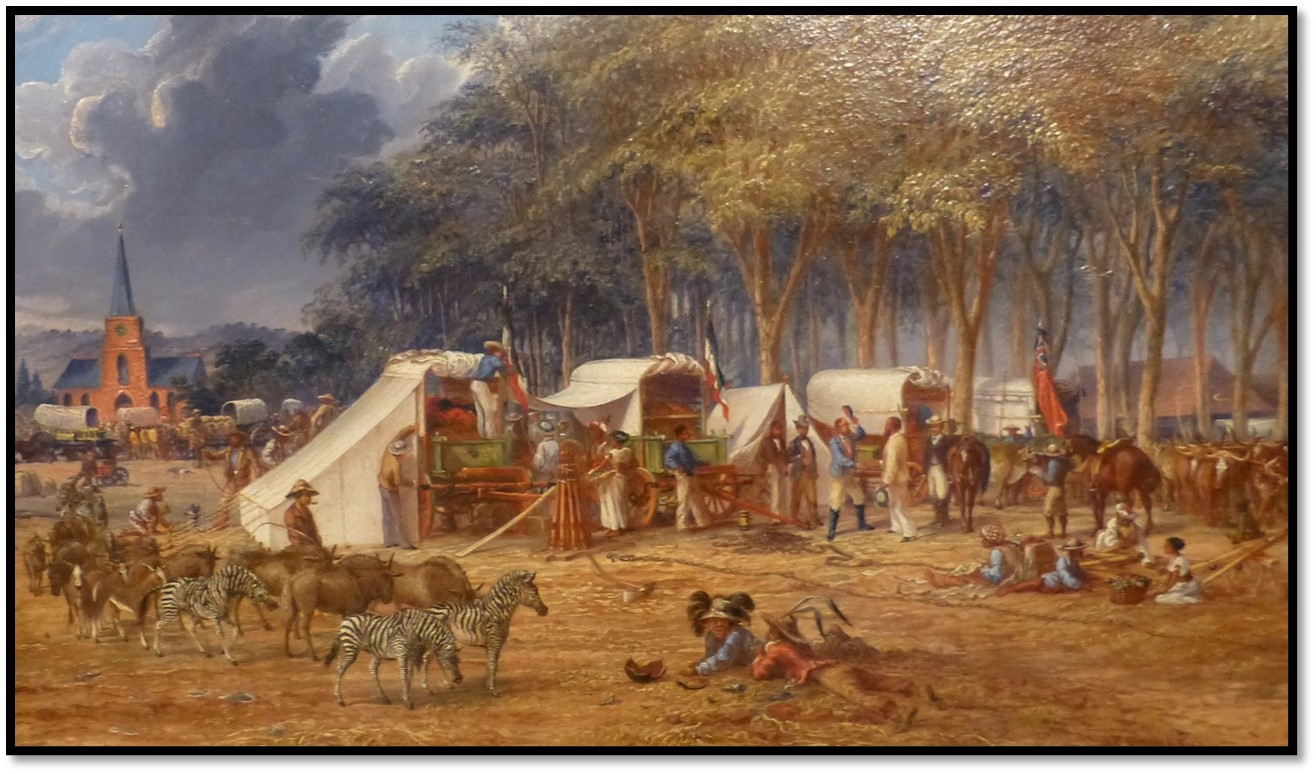

Their stores had mounted up and rather than hire a transport rider, a second ox-wagon was bought with twelve oxen. After a near-disastrous fire in the wagon storehouse, their wagons were drawn up to the market square alongside those of Eduard Mohr [xxi]and Hübner,[xxii] each flying their respective country’s flags and set against a backdrop of syringa trees and the scene busy with camp followers.

NAZ: The South African Goldfields Exploration Company’s expedition preparing to leave the Market Square, Maritzburg. Baines is seen greeting Eduard Mohr

On 13 March 1869 The wagons left making short, easy stages so the drivers and oxen familiarised themselves. It was still the rainy season and the tracks in the foothills leading to Van Reenen’s pass were heavy going, but the frequent farms and Zulu villages with their beehive huts made agreeable conditions for travel. After passing Howick they were pummelled by large hailstones as big as musket balls. Next day Baines noted: “6.30am-sunrise light from right, green hills, warm lights, deep shadows and rolling mist.”

In many places the ox-teams were doubled to get the wagons up the sharp curves and steep descents. At one spot the wagon wheels climbed the stones on the very edge of the track and for a breathless moment Baines expected the wagon to topple down the steep slope dragging the oxen with it. However the wheels came back on the track and the wagon toppled over on its side. Poles were cut and thrust through the wheels, ropes tied to the pole ends and the wagon gradually righted. At other places screw-jacks eased the wheels out of holes and causeways built across streams.

At the Tugela river where the wagons were pulled across on a pontoon, he met Mohr and Hübner again and compared his map of the route with theirs. At Sand spruit they stayed at the Dew Drop Inn where Baines painted a sign for the Inn of a woman’s are holding a pendant flower, dropping dew.[xxiii]

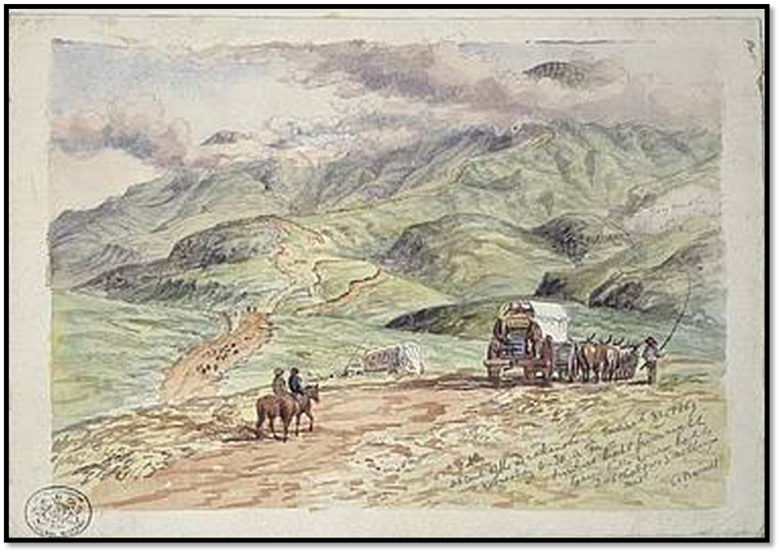

NHM : Ascent of the Drakensberg 31 March 1869 by Thomas Baines

Next day, the 31 March, they began the ascent of the Drakensberg. The first wagon started on the spurs and along the ridges. Robert Jewell, as well the native drivers needed to watched to ensure they did not indiscriminately use their whips particularly on the steep slopes where double teams were used. In ‘a nasty little hollow’ the screw-jacks had to be used and a causeway built. The lead wagon had just scaled the last slope with cracking whips and every man screaming at the top of their voices when the heavens opened up and the rain came down. Next day the second wagon was brought up when the sun had dried the mud on the track and even then stones had to be laid for the wheels.

Harrismith and the Orange Free State[xxiv]

The descent into the Orange Free State[xxv] was just as hazardous – both wagons sank nave-deep in a swamp and took much labour to be pulled out, but finally the Wilge river was crossed and they were in Harrismith. Here he met the Presbyterian minister, Macmillan from Aberdeen, who ministered to the scattered Boer farmers and enjoyed their culture and hospitality before trekking onwards on 8 April.

The rain pelted down, there were no roads, only wheel-tracks and as there were no trees until they reached the Vaal river, they burnt ox-dung to keep warm during the cold nights. Blesbok, springbok and wildebeest were present in their thousands.

They met a few other travellers like themselves, Boers who had been as far as the Limpopo and miners returning from the Tati goldfields and on 20 April they reached the Vaal, crossing at Lys’s drift and turning west for Potchefstroom.

The roads were terrible necessitating the frequent use of the screw-jacks and building of causeways, the countryside was blighted by locusts and they were pleased to see Potchefstroom on 27 April. The party cleaned themselves up, hoisted their flag and rode in to camp once more beside Mohr and Hübner in a grove of willow trees.

Potchefstroom

In 1850 when Baines first visited Potchefstroom had been a hamlet of fourteen houses, now it had four or five hundred inhabitants. He met the field cornet who had been sent to take him dead or alive and they enjoyed a drink together. He noted: “But it certainly did feel strange to be thus drinking and conversing on friendly terms with a man who had formerly been authorised to send a bullet through me with his little compunction as if he had shot a bird.”[xxvi]

Situated just north of the Orange Free State, Potchefstroom was in the South African Republic (ZAR) or Transvaal Republic[xxvii] and in a bad way at the time. Near Potgietersrus (now Mokopane) a party of Boers were murdered at a ford on the Maghaliquain river known thereafter as Moordenaars drift. The government surveyor told Baines he went to work armed as some Boers did not want their farms surveyed. Two of Baines servants were arrested for singing on Saturday night after curfew. Baines paid their fines, but Mohr refused to pay the fine of one of his servants and he served jail time.

Wagons of the South African Gold Fields Exploration Company leaving Potchefstroom in 1869

Baines painted the above painting for Mohr and it created great interest amongst local burghers who had never seen an artist at work. The money received he paid into the Expedition funds as money was slow coming from the company.

Amongst his many acquaintances in Potchefstroom was Fred Jeppe, the postmaster general who was also well-known to Karl Mauch [See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo province on this website]

The route from Potchefstroom across the Magaliesberg to Rustenberg and then nearly due north to the confluence of the Marico and Crocodile rivers was the easiest and most common route followed by hunters and traders of the day. It then ran through Sechele and Matjen’s territory to the Macloutsie river, a large tributary of the Limpopo. From here the route was in Makalaka territory where it climbed to the watershed running in from south-west to north east dipping as it reaches the main river the Shashe and the Tati and finally the Ramokgwebana where it enters amaNdebele territory.

Journey to the Magaliesberg to meet Henry Hartley

On 8 May 1869 the restocked wagons left, Baines stayed behind to talk to travellers who had just arrived with news of the Tati goldfields, before following on. On the way he sketched the limestone caves at Wonderfontein before taking Nelson and Jewell to meet Henry Hartley at his farm, Thorndale. Hartley amused them with stories such as that he told his neighbour McCabe, who Baines knew, that all elephants were to be branded ‘Zuid Africansche Maattshappij’ so that English hunters would know they must not shoot them!

They would have discussed the situation in Matabeleland where Mzilikazi had died on 5 September 1868 and there being no heir apparent, a Regent, Ncumbata or Mncumbatha Khumalo is appointed (Baines spells his name Umnombata) He is very old – reputed to be almost 100 years and quite frail and may have had dementia. However despite factions taking different views, his authority is generally recognised, although no really important questions such as mining concessions would be dealt with until the new king’s coronation.[xxviii]

Some Ndebele, including the Zwangendaba Regiment under Mbiko Masuku hope Nkulumane is still alive in South Africa and oppose Lobengula. A bloody fight ensued from which Lobengula's forces emerge victorious and Lobengula’s coronation took place in 1870.

[See the article KoBulawayo, or Old Bulawayo (1870 – 1881) and the Indaba Tree under Bulawayo on this website]

The situation in Matabeleland was confused and it was a great relief to Baines when Hartley said he was about to start on a hunting trip and Baines could accompany him if his heavily-laden wagons could keep up with Hartley’s fresh teams and lightly-laden wagons. Hartley knew the route, the water-holes and was known to all the headmen along the route as the friend of the late Mzilikazi.

The wagons travelled together over Oliphants Nek to Rustenberg where they turned north for the Marico and Limpopo rivers. Hartley was invaluable in teaching Baines amaNdebele etiquette and he decided that he would explain that he had come as citizen of Queen Victoria, not to steal their land, but to look for gold and bring the benefits of free trade. Hartley told him to make use of Lieutenant-Governor Keate’s letter and Baines also painted the royal coat of arms on his wagons.

The Limpopo river is reached

Wallis writes that on 23 May the Limpopo was reached and next day they were at its confluence with the Marico river.[xxix] At this point it is described as “a fair-sized stream with high clay banks fringed with feathery reeds and overhung by acacias and other trees.”[xxx]

Here the wagons were sent down the steep banks to ford the river, a task that required concentration and was achieved without mishap.

Amongst the hills in the territory of the Bamangwato (present-day Botswana) the wagons were visited by a young chief. He knew Hartley would be on a hunting trip but was puzzled by Baines. To explain, Baines took out his sketch-book and explained he was here to make pictures. The chief believed he must be a spiritual or herbal doctor (Nganga) and asked him to cure his son’s sore eyes and Baines administered a simple lotion and powders.

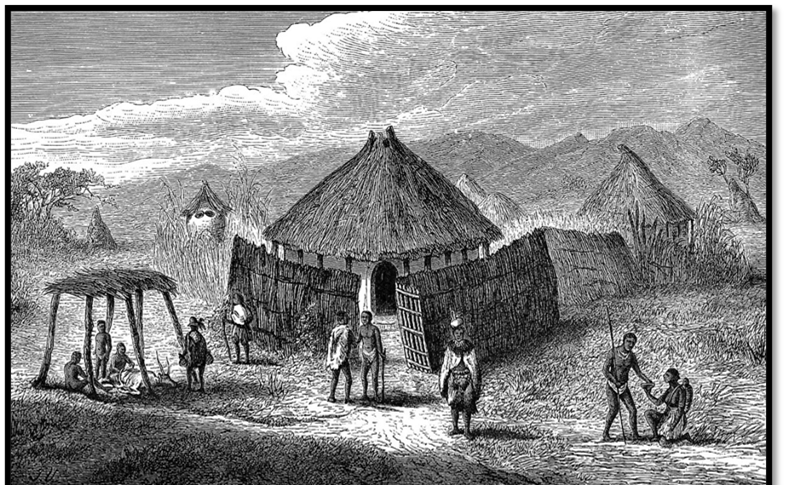

Hartley protects Baines at Shoshong

Shoshong the Bamangwato capital, on the Shoshong river, an intermittent tributary of the Limpopo, was reached. It had been sited because it was easily defensible against the amaNdebele but is described as “a clutter of slovenly huts and foul lanes” and its chief, Matjen, as a “treacherous, grasping rogue” who harassed all travellers until he was driven out by Khama III in 1873. He had an army of 8,000 men armed with Tower muskets and guns and ammunition were the main barter items.

Wikipedia: Bamangwato huts at Shoshong 1881, from the book Seven Years in South Africa, volume 1, page 372

Hartley’s presence however saved Baines from Matjen’s greed and it was the British agent Gordon who rode down to the wagons and challenged Baines’ right to fly the red ensign and asked what he would do if fifty men came to tear it down. Baines replied that he did not think an Englishman would attempt such an outrage and Gordon rode away, muttering.

Tati is reached

On 9 June Baines and Hartley’s wagons reached the Tati district between the Shashe and Ramaquabane (present-day Ramokgwebane) rivers. Sir John Swinburne was away, but his storekeeper Benjamin Kisch welcomed them. Baines party consisted of Nelson, Jewell and Watson. Hartley’s party included his son-in-law Molony, McMaster and the brothers George and Swithin Wood.

Tati District

This area between the Shashe and Ramaquabane (present-day Ramokgwebane) rivers was a bone of contention between the amaNdebele and the Bamangwato. Old Tati and the gold bearing quartz reefs were all in the valley of the lower Tati river. Both Bamangwato and amaNdebele tribes claimed tribute from concessionaires at different times.

Google Earth - Tati District

The question of ownership was eventually settled summarily by the British who made Bechuanaland north of the Molopo river a British protectorate in September 1885.

References

T. Baines. Explorations in South-West Africa : being an account of a journey in the years 1861 and 1862 from Walvisch Bay, on the Western Coast to Lake Ngami and the Victoria Falls / by Thomas Baines. London : Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, & Green, 1864

F.O. Bernhard (Edited and translated) Karl Mauch African Explorer. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town 1971

R.J. Mann. Account of Mr. Baines's Exploration of the Gold-bearing Region between the Limpopo and Zambesi Rivers prepared from Mr. Baines's Journals. The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London , 1871, Vol. 41 (1871), pp. 100-131

J.P.R. Wallis. Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn. Books of Zimbabwe, Bulawayo, 1982

Notes

[ia] The Zambezi river turned out to be completely unnavigable in the Cabora Bassa rapids after which Lake Cahora Bassa is named

[ib] Karl Mauch African Explorer, P80

[ii] This passage shows some of the negative traits of Mauch’s character. Both a failure to mention that Hartley has spotted the significance of the Tati goldfields the year before and brought Mauch with him and the unwarranted criticism of the Afrikaners in the interior, many of whom actively assisted him during his travellers

[iii] For details see the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[iv] Karl Mauch African Explorer, P22-3

[v] James Chapman, Edward Barry and Thomas Baines reached the Victoria Falls on 22 July 1861

[vi] The RGS at the time was in Whitehall and later settled in Kensington

[vii] The RGS under-secretary

[viii] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P230

[ix] Richard Thornton had been another member of David Livingstone’s ill-fated Zambesi expedition and after leaving Livingstone had joined Baron von der Decken’s expedition to Kilimanjaro, but died of fever and dysentery on 21 April 1863

[x] The Albert Nyanza, great basin of the Nile and explorations of the Nile sources by Samuel White Baker, 1866

[xi] Wikipedia – Nathaniel Burslem

[xii] Explorations in South-West Africa : being an account of a journey in the years 1861 and 1862 from Walvisch Bay, on the Western Coast to Lake Ngami and the Victoria Falls by Thomas Baines

[xiii] ‘The Victoria Falls, Zambesi River – sketched on the spot’ was published in 1865

[xiv] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P241

[xv] The geologist Sir Rodney Impey Murchison was President of the Royal Geographical Society many times 1843-5, 1851-3, 1856-9, 1862-71

[xvi] He could also claim 3,000 shares at par. If the expedition was a success he salary would rise to £300 per annum and the value of his shares would soar.

[xvii] Mrs Baines died on 29 March 1870 and Thomas never returned to England again

[xviii] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P247

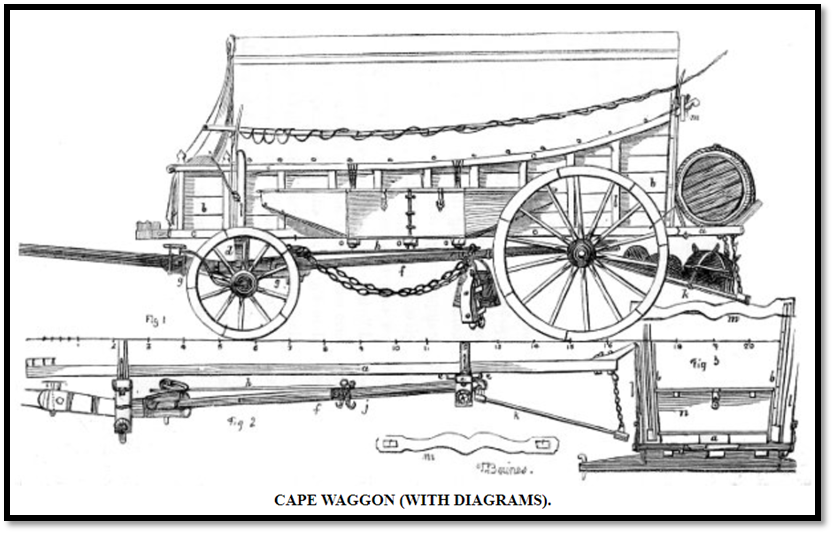

[xix] The website has a very good article on ox-wagons that goes into much detail https://grahamlesliemccallum.wordpress.com/2016/07/14/the-cape-wagon-fun...

[xx] Erskine had explored the lower Limpopo and after much hardship had been to its outlet to the Indian Ocean

[xxi] Eduard Mohr was an explorer and author of To the Victoria Falls of the Zambezi published in 1876

[xxii] Adolf Hübner (Baines calls him Hubenaar) was a mining engineer sent with Mohr at the prompting of August Petermann, the German cartographer

[xxiii] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P255. Wallis quotes the daughter of St V.W. Erskine as saying: “He [Baines] shyly asked father if he would allow mother’s beautiful arm and hand to be used as a model.” Perhaps she would consent: “if her arm was covered with blue illusion gauze.”

[xxiv] A Boer Republic from 1854 to 1902

[xxv] The Orange Free State lay between the Orange and Vaal rivers

[xxvi] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P258

[xxvii] The Transvaal republic lay between the Vaal / Hart rivers and the Limpopo

[xxviii] Ibid, P263

[xxix] For the technically minded – in fact they were on the Crocodile river. The Limpopo only begins at the confluence of the Crocodile and Marico rivers

[xxx] Thomas Baines of King’s Lynn, P264

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: