Strategies for minimising human – elephant conflict in Zimbabwe

Because of ever increasing human growth and encroachment into wildlife habitat, degraded foraging, reduced landscape connectivity and a significant decline in historical elephant populations, the problem of human – elephant conflict increases, not only in Zimbabwe, but in other African countries such as Zambia and Namibia and elsewhere with the problem being particularly pressing in Sri-Lanka and some of the Indian states.

Until now most strategies have been human-centric and weighted against wildlife offering solutions to deter elephant behaviour and have been based on keeping humans and elephants apart.

In Zimbabwe, Jacqueline Kubania of the African Wildlife Foundation (AWF) writes that they understand the economic benefits of having a thriving wildlife population that promotes wildlife tourism – these funds have been used to build schools and healthcare facilities. However, destroyed crops and injured or killed humans also builds resentment towards wildlife.

Nero Mtupaunga, a small-scale farmer from Mbire district says: “I have woken up to half of my crops gone after a night of elephants rampaging among the sorghum, cotton, and groundnuts. Couple that with other challenges including water shortages and pests and it means that there are times I only manage to harvest a quarter of what I planted, which is barely enough to feed my family, let alone sell for profit.”[i]

Collen Matema is AWF’s Community-based Natural Resources Management Officer in Mbire and knows the area well. The biggest challenge in implementing conservation activities in Mbire district has been demonstrating to the local community that peaceful co-existence between wildlife and people is possible if they put in place a few effective measures. Some of these strategies are discussed below.

Elephant Facts

Being long-lived animals, elephant survival depends upon seasonal migration across large areas to meet their needs for food, water, and social and reproductive partners. They consume about 150 kg of forage and 190 litres of water per day. Meeting those needs requires a large area to ensure they get a variety of grasses, shrubs, tree leaves, fruits and roots. An African family herd will typically range over 11 to 500 sq. kms.[ii]

In return research has shown they play a key role in shaping the landscape and a healthy elephant population maintains wide biodiversity.

Results of human-elephant conflict

As humans encroach evermore on elephant habitat, the likelihood of conflict increases. In India it is estimated that half a million families are affected by crop-raiding; there are 400 human deaths annually with 100 “problem” elephants being culled. Sri Lanka annually has about 70 human deaths and 200 elephants culled. In Kenya about 200 humans are killed by elephants and 50 to 120 problem elephants culled annually. Other Southern African countries have lower, but significant numbers.

Many of those directly affected are amongst the world’s poorest and live in marginalized communities that increasingly compete with the elephant for space and resources.[iii] There is often competition during the dry season between human needs for water for themselves, their crops and livestock and elephants.

Elephant conservation efforts

Conservation efforts in recent years have focussed on reducing human and elephant lives due to conflict to reducing habitat damage and ivory poaching and wildlife trafficking. Internationally the ivory trade has been curtailed and made illegal in many countries, but not all.

L J Shaffer, K K Khadka, J Van Den Hoek and K.J. Naithani write that: “Research in Zimbabwe suggests that elephant populations will co-exist to varying degrees with human communities until a threshold of about 15–20 people/km2 is reached (Hoare and Du Toit, 1999). At this point, the habitat loss and fragmentation accrued from a 40–50% transformation of the landscape for human livelihood activity use renders the area unfit for elephants.”[iv]

Human encroachment deprives elephants of their preferred forage and concentrated elephant foraging contributes to biodiversity loss and restricts their migration patterns…the habitat fragmentation leads to human-elephant conflict with roads and farms around their fragmented feeding grounds. The proximity of agricultural fields leads to crop-raiding.

Most strategies rely on altering animal behaviour by instilling fear in them

In the past most of the strategies have been to condition fear into elephants so they avoid human contact. Early efforts were directed at killing “rogue animals” that invaded villager’s fields – this had the advantage of also providing ‘sport’ for the hunter and many early written accounts by district commissioners and district officers give details of how they dealt with these problem animals and earned the grateful praise of villagers.

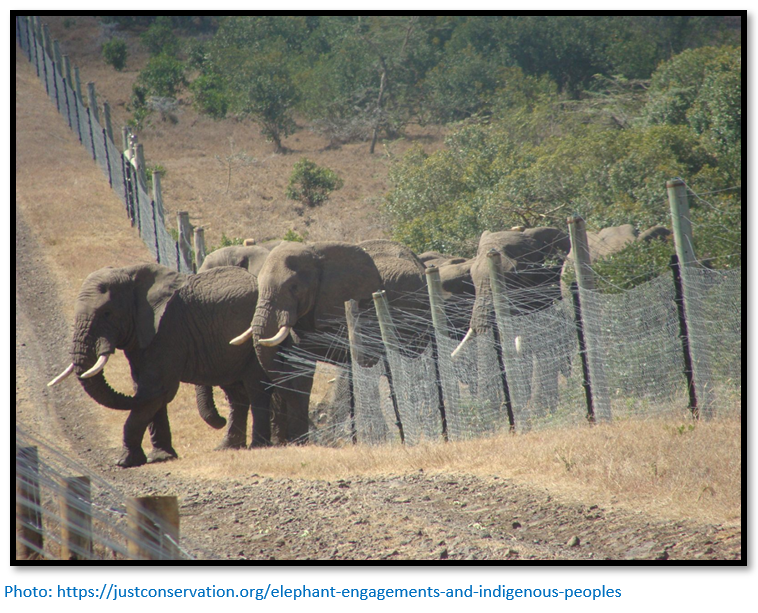

Fencing methods - Other attempts were made to fence off areas with barbed wire or chain link, more recently with electrified fences, but often these are overcome by the animals themselves as the photo below shows. Elephants are quick to learn when electric fences are inactive and that their tusks do not conduct electricity, so they use their tusks to break an enclosing electric fence, resulting in costly damage to the fence.

Physical barriers also negatively impact by further isolating already fragmented elephant populations, disrupting their movement and access to seasonal food and water resources and impeding gene flow between herds.

Experiments have been done in applying chilli pepper paste to a rope and beehives hung on fences or nearby trees have been shown to be quite effective at deterring elephants and have the added benefit of providing pollinators and honey. These all rely on fear responses from the elephant.

Perimeter methods – buffer crops such as chamomile, coriander, mint, ginger, onion, garlic, lemongrass and citrus trees can be planted around agricultural areas that are unappealing to elephants, trenches or ditches can be dug around fields which elephants find difficult to cross, trip-wires can be placed to warn crop guards.

Repellents – chilli pepper guns can be used, burning chilli and dung, chilli bombs utilised (dried chillies combined with dung and water) burning wood fires or using spotlights which are shone in elephants’ eyes to drive them away.

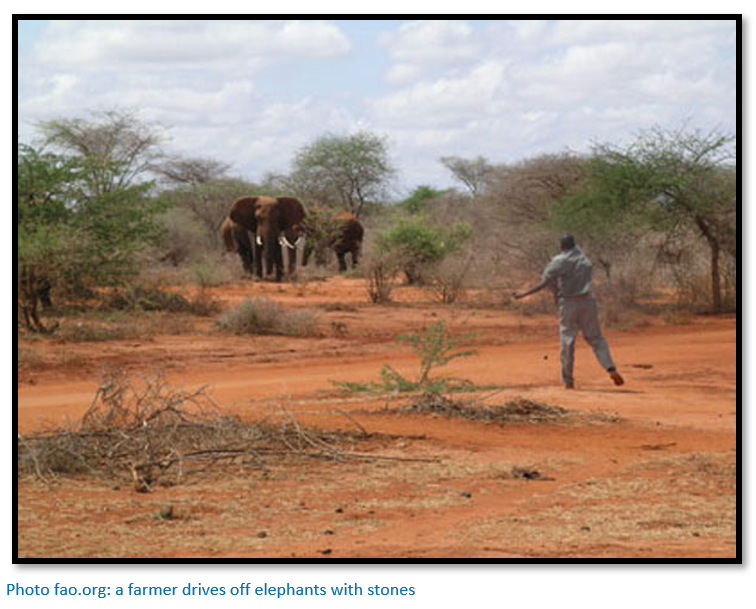

Acoustic deterrents – loudhailers playing loud sounds, using hand-held firecrackers whose light and sounds drive the animals away, hiring guards or local farmers occupying watchtowers, paying compensation for crop damage, human injury and death. Farmers have traditionally guarded crops and scared away crop-raiding elephants by yelling, setting off firecrackers, hitting metal objects, and throwing stones. Research has shown that elephants quickly learn to tolerate these sounds and return to raid crops.

Early detection and warning

Some warning systems incorporate detectors that monitor the infrasonic sounds “elephant rumbles” that they use to communicate and send texts to the mobile phones of farmers and local officials so that the elephants can be driven away before they begin their crop-raiding activities. In remote areas however there may not be the phone coverage to send texts to farmers. Satellite collars on elephants have also been used to trigger detectors into alerting individuals of their presence, but of course they need to be initially captured and collared.

Relocating elephants – moving elephants by drugging and immobilizing them before transporting them to new areas may result in increased conflict in those release areas and the spread of problematic behaviour. In many cases the elephants attempt to return to their original territory.

Paying compensation to those affected by crop-raiding

The attitude of local communities is crucial in managing human-elephant conflict[v] and compensation for crop losses can play a major role in building positive attitudes and tolerance towards their elephant neighbours. The process involves reporting any crop or property damage to park officials and then a visual assessment of the damage before making a compensation claim. In both Asia and Africa this creates opportunities for corruption, many African countries lack any official compensation process and others, including Zimbabwe, lack the financial resources to pay meaningful compensation.

Selective culling

The culling of ‘problem’ elephants, particularly those that have killed humans has been practised for a long time…it provided meat to local communities and offered ivory to the hunter. The widespread killing of elephant in Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe forced the herds into more marginal areas where they were protected by the presence of tsetse-fly. Illegal poaching and commercial safari hunting have targeted bull elephants with their heavier tusks, and this has potentially degraded the genetic health of fragmented elephant populations.

Mumby and Plotnik say that human – elephant conflicts take a variety of forms ranging from agricultural, environmental and / or financial impact related to elephant crop-raiding or foraging, to damage to property and water points and grain stores as well as injury and death to livestock and humans which often leads onto retaliatory killing of elephants by humans.

The above methods are all human-centric and offer wildlife deterrents, addressing the symptoms rather than offering solutions

They argue that more attention needs to be paid to the underlying causes of the problem from the elephant’s perspective – in fact interactions between humans and elephants are not always negative “and coexistence is a better term because it highlights that positive relationships can and do exist between species living in the same habitats and landscapes.”

They acknowledge: “that humans and elephants do often compete for resources and are often involved in agonistic interactions across both African and Asian landscapes.”[vi]

In the article on “human-elephant conflict” the authors argue that many strategies designed to minimise human-elephant conflict frequently transfer the conflict risk from one place to another.[vii]

There is a need to take the “elephants' perspective” to prevent conflict between humans and elephants

Mumby and Plotnik argue that more research needs to be done in: “investigating elephant behaviour, cognition and ecology at the level of the individual to prevent conflict from occurring in the first place.”

It is clear that: “in the social context, elephants are generally regarded, like humans, as cognitively complex, socially intelligent animals that display empathy toward and learn socially…”[viii] For example, they will respond to changing environmental conditions such as droughts by adjusting growth and reproduction rates. The young learn behaviour patterns and the layout of their landscape from both their mothers and the herd matriarch. Bulls live in a bachelor herd where they learn correct behaviour from the leader.

A clearer scientific understanding of their non-visual sensory modes - i.e., their sense of smell and hearing and listening will definitely lead to strategies that mitigate human – elephant conflict.

They believe that erecting physical barriers will not serve human – elephant conflict in the long-term.

Crop-raiding may be not only to access food

Mumby and Plotnik argue that migration may be a primary reason for crop-raids with limited space available in National Parks, the demography of the elephant population and dispersal patterns of male elephants may be another driver or other reasons not yet clearly identified.

There has been research done on the use of elephant communication – the low infrasonic rumbles they make – to better inform humans about the presence of elephants and to provide early warnings of their presence.

Mitigation strategy requires awareness of human and elephant behaviour

Before any action is taken, a careful evaluation of both human and elephant behaviour in any locality needs to be carried out with all the disciplines - biology, psychology, anthropology and ecology at this level being involved, with: “both the social dynamics and landscape use of the humans and the elephants must be considered.”

In village communities with good leaders and friendly relations between local people then projects that require collaboration over maintaining several kilometres of electric fence may find success. Where good relations do not exist, they must be resolved first for people to co-operate if such a project is to succeed.

Elephants show individual behaviour towards conflict

The question of why some elephants come into greater conflict with humans than others has been studied and the solution could relate to:

- Parasite load

- Body size

- Social hierarchy

- Cooperation

- Problem-solving

- Aggression

- Personality

Identifying if specific behaviours, physical characteristics, demographic or personality traits correlate with their tendency to crop-raid or engage in conflict would help prevent these conflicts occurring in the first place.[ix]

Research is required to identify individual differences in elephants in confidence, innovation, risk-taking, leadership or neophobia (fear or dislike of new or unfamiliar situations) and in any study area it is important to get a clear understanding of each individual elephants’ characteristics as well as the leadership structure within the groups.

Influencing an elephants’ decision-making process

Armed with this information, Mumby and Plotnick state; “that instead of forcing animals away from resources they desire or need, the animals make decisions on their own to avoid them. This would inevitably promote coexistence rather than conflict…we believe scientific research into behaviour, ecology and cognition has great promise for helping develop new strategies to prevent conflict between humans and wildlife.”

Long-term resolution of human-elephant conflict

L J Shaffer, K K Khadka, J Van Den Hoek and K.J. Naithani highlight the importance of including anthropological and geographical knowledge of site-specific considerations to find sustainable solutions for the African elephant population of 550,000 to 700,000 elephants in sub-Saharan Africa and far smaller elephant population in Asia.

Alternative Suggestions for mitigating conflict

L J Shaffer, K K Khadka, J Van Den Hoek and K.J. Naithani suggest:

Ecological corridors between fragmented habitats (and National Parks) which facilitate connectivity between elephant herds, provide rescue routes and enhance gene flow by providing routes for seasonal migration and allow herds to move to new feeding and water sources.

In Zimbabwe local community leader Chimukoro states: “One of the biggest challenges exacerbating human-wildlife conflict in this area is the settlement pattern. People are scattered all over with no thought to wildlife areas. So even when we try to deal with the elephants and successfully repel them from one place, they go on to affect the next household. As council members, we are trying to fix this by organizing settlement areas to ensure that wildlife corridors are opened up to prevent wildlife from straying into farms.”[x]

Effective strategic planning that seeks to support both humans and elephants must focus on their co-existence rather than conflict by addressing what causes the conflict. They focus “on resource competition and resulting conflict for water, food and space between humans and elephants.”[xi] Strategies could include digging new wells or boreholes along elephant migration paths that divert them away from areas populated by humans. They argue that it is crucial to identify potential conflict hotspots and to identify how humans living close to these hotspots use natural resources. Only then can effective land management strategies be devised.

Some specific solutions expanded

An article by Hannay Thomasy details how Beehive fences can help mitigate human-elephant conflict. The article explains how crop-raiding by elephants can cause catastrophic losses to small farmers and even lead to injury and death.

One solution that has been tried with success is beehive fences - surrounding fields with beehives attached to fence posts and strung together with wires. Trials in Tanzania have shown that they can be a success as long as the farmers are willing to manage the bees and the bees are willing to co-operate!

Zoologist Lucy King of the NGO Save the Elephants told Mongabay the idea came from Kenyan farmers, who noticed that elephants avoided foraging in trees that contained beehives. Beehive fences are made with the hives ten metres apart on posts with thatched roofs to keep off the sun and connected to each other by wires: any movement on the wire makes the hives sway and agitates the bees.

Trials have taken place in fifteen African countries including Botswana, Kenya, Mozambique, Tanzania and Zimbabwe and four Asian countries, they have shown that beehives are much more effective than traditional thorn fences and that 80% of elephants were deterred from entering the fields. Many communal farmers have requested to be part of the trials in both Africa and Asia.

Other benefits are that bees provide additional pollination which increases crop yields and honey is a useful by-product which can be sold for cash. Although initial results look good, African honey bees are extremely aggressive and beekeeping skills need to be taught with further trials needed to be carried out to see if the scheme can be rolled out on a larger scale. In some trials beehive fences have been supplemented with chilli oil on the fences to deter elephants.

Shreya Dasgupta in a BBC article titled ‘five ways to scare off elephants’ reveals that elephants don’t like chillies. Apparently, Capsaicin, the chemical within the chillies that makes them hot is an irritant which even makes elephants cough and sneeze and is an effective deterrent.

Buffer crops of chillies can be grown around maize crops and The Elephant Pepper Development Trust in South Africa has been teaching farmers to smear rope fences with a mix of waste engine oil and red chilli and hang cow bells to deter elephants away from their fields. Sarah Fretwell states in an article Zambian Farmers Use Spicy, Natural Deterrent to Ease Conflict with Elephants that in Zambia’s Eastern Province natural deterrents, such as chilli fences, are being used to keep elephants away from their crops and reduce human – elephant conflict.

Smallholder farmers struggle to produce enough food for their families and their crops can be destroyed overnight by a small herd of ten to fifteen elephants.[xii] Malama Njovu, Community Liaison Assistant for Zambia’s Department of National Parks and Wildlife (DNPW) says farmers will resort to spearing, snaring or poisoning the elephants if they are not provided with workable solutions to defend their crops with obvious negative impacts on wildlife conservation.

Chilli fences are made of two to three strands of sisal string strung along poles surrounding a crop. The ropes have cloths (mutton cloths work well), or rags soaked in chilli oil hung between the two strands of rope in between the two nearest poles. Both the rags and the sisal rope are first soaked in spent engine oil that has had crushed dried chilli powder mixed into it.

The DNPW works with local farmers to provide alternatives and chilli fences are an example. A main advantage of chilli fences is that they are inexpensive for farmers to build, taking just a few days to construct. Once farmers have dug holes and erected poles around their crops, they simply need to string rope between the poles and attach pieces of mutton cloth that have been smeared with a mixture of ground chillies and grease.

Malama says: “Once an elephant touches the cloth smeared with chilli paste, the chilli enters the elephant’s pores and starts to itch. This further dissuades the elephant from entering the field.”

Collen Matema, AWF’s Community-based Natural Resources Management Officer in Mbire says training community scouts and farmers to grow and use chilli has proved successful.[xiii]

“Both these efforts are working well so far. The use of chilli especially has proven to be sustainable, cost-effective, and easily adopted by households. Other than chilli blocks, farmers can also dip string in a mixture of oil and chilli powder and use it to fence off their farms. Testimonials from farmers show that this has also been quite successful in driving elephants away.”[xiv]

Creating pungent smoke – farmers in southern India combine dry grass with tobacco and dried chilli pods and seeds wrapped in newspaper to make a strong-smelling smoke that elephants with their keen sense of smell dislike. Clearly for this technique to work, the farmer must be in his fields when the elephants arrive.

In Zambia the DNPW shows farmers how to make chilli bricks that work the same way. Elephant dung is mixed with chilli to make the bricks and dried. When elephants are sighted, the bricks are lighted downwind in the direction of the elephant’s path and that drives them away.

Malama says: “Chillies are relatives easy to grow and there's a big demand for them since they are used often in Zambian cooking. So, farmers are really excited to integrate this new crop,” which provides additional cash income.

Jacqueline Kubania in her African Wildlife Foundation article Chilli peppers stop human-elephant conflict in northern Zimbabwe describes local Zimbabwean farmer Chenjerai Chimukoro driving off a herd of nearly 70 elephants from his fields of sorghum, cotton and maize using the same chilli pepper blocks whose smoke irritated the herd without harming them and drove them away. Again, Chimukoro says he made the effort to grow chillies to keep the elephants off his lands and to earn extra income and his efforts seem to be paying off.

In the remote parts of Zimbabwe these human – elephant encounters are almost a daily occurrence and in the past small farmers suffered severe crop-raiding which led to retaliatory attacks on wildlife. Zimparks reported that 20 people died from elephant attacks between January to October in 2019.

Using ‘chilli balls’ to reduce human-elephant conflict in Zambia

An article in Africa Geographic describes how twenty volunteers with Conservation South Luangwa (CSL) from communities around the South Luangwa National Park in Zambia have been using chilli balls, which are ping pong balls filled with chilli oil, to drive away elephants. They patrol at night as this is when elephants are most active.[xv]

The chilli ball is fired from a “chilli blaster” which is an ingenious device and does not hurt the elephant. The end of the “chili blaster” is unscrewed and the ping pong ball filled with chilli oil inserted. Flammable insect spray is sprayed into the chamber – an igniter at the back of the device when clicked ignites the gas and fires the chilli ball.

The chilli ball leaves chilli oil on the elephant’s hindquarters, which they dislike and so move off, the oil being washed away the next time the elephant sprays itself with water.

Emma Robinson, Human Wildlife Conflict (HWC) Program Manager says: “The nine chilli patrollers achieved 1,333 man-nights, firing 839 chilli ping pong balls to deter over 1,363 elephants in four months. This real practical help makes such a difference to the farmers, who are supportive of the project. In return, they help the patrollers by clearing pathways to their fields, so they can move around easily and safely after dark. They also increase the patrollers’ effectiveness by raising an early warning when they see approaching elephants. Not surprisingly, it’s much easier to move an elephant on, before its found a plentiful supply of deliciousness.”[xvi]

Apparently, elephants hate the ringtones on mobile phones, and they can be used to scare elephants away.

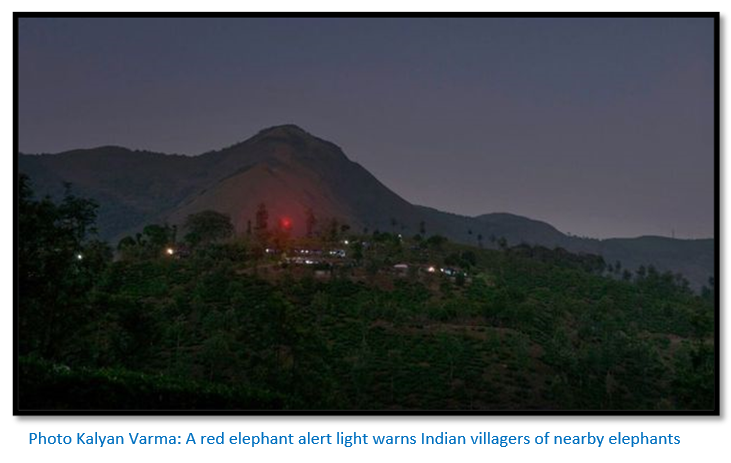

In southern India where elephants live in close proximity to tea and coffee plantations there have been many surprise encounters which can lead to human fatalities. The Nature Conservation Foundation has devised a simple SMS system to warn farmers. If an elephant is spotted, the NCF is alerted, and they text everyone living within two kilometres of the initial contact. A red elephant alert light on a mast also starts flashing in the vicinity to warn farmers of elephant presence and this can be set off by dialling its number to warn people returning to their homes in the dark. The system appears to be very successful in warning people of the presence of elephants.

References

H S Mumby and J M Plotnik. Taking the Elephants' Perspective: Remembering Elephant Behaviour, Cognition and Ecology in Human-Elephant Conflict Mitigation. Ecol. Evol., 20

August 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fevo.2018.00122 and at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fevo.2018.00122/full

L J Shaffer, K K Khadka, J Van Den Hoek, K.J. Naithani. Human-Elephant Conflict: A Review of Current Management Strategies and Future Directions

Hannah Thomasy. 11 September 2019 in Beehive fences can help mitigate human-elephant conflict: https://news.mongabay.com/2019/09/beehive-fences-can-help-mitigate-human...

Shreya Dasgupta. 7 December 2014. http://www.bbc.co.uk/earth/story/20141204-five-ways-to-scare-off-elephants

Sarah Fretwell. 30 October 2019. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/10/30/zambian-farmers-use...

[i] Chilli peppers stop human-elephant conflict in northern Zimbabwe

[ii] Human-Elephant Conflict

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Ibid

[v] Ibid

[vi] Taking the Elephants' Perspective

[vii] Human-Elephant Conflict

[viii] Taking the Elephants' Perspective

[ix] Ibid

[x] Chilli peppers stop human-elephant conflict in northern Zimbabwe

[xi] Human-Elephant Conflict

[xii] Zambian-farmers

[xiii] African Wildlife Foundation, with the support of the European Union, has so far supported 48 chilli growers in Mbire district,

[xiv] Chilli peppers stop human-elephant conflict in northern Zimbabwe

[xv] Using ‘chilli balls’

[xvi] Ibid