Home >

Mashonaland West >

The story behind Derick Hoste who died of blackwater fever at Hartley Hills in 1893

The story behind Derick Hoste who died of blackwater fever at Hartley Hills in 1893

How to get here:

Hartley town on the A5 national road is now named Chegutu. The original Hartley Hill goldfields are east of the junction of the Mupfure River (formerly the Umfuli) and the Chimbo River (sometimes marked Zimbo) The area is easily reached from the main Harare Bulawayo A5 National road 71 KM from Harare, by turning left off the National road at the roundabout, south toward Ngezi Mine. At 7.2 KM continue past Chengeta Safari Lodge turnoff on the left and at 15.73 KM reach Seigneury Road intersection. Turn left onto the gravel road, 17.54 KM go to the left of the Seigneury store, 17.69 KM cross the Chimbo River, 18.00 KM pass the stamp mill on your left, 18.62 KM stay on main gravel road, pass old gold diggings on your right, 19.11 KM a farm track turns left for Fort Hill. (i.e. 3.3 KM from the tar turn-off) 19.27 KM take right-hand fork, 19.62 KM park car and the fort is on the summit of the kopje to your left.

The cemetery is 150 metres to the north east.

GPS reference for the cemetery: 18⁰12′12.55″S 30⁰23′45.19″E

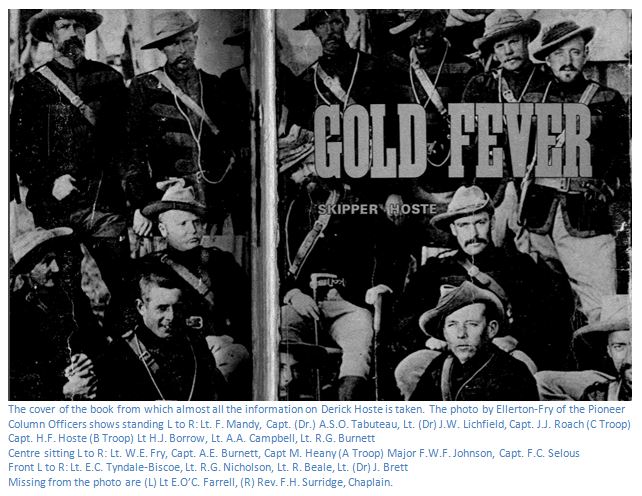

Henry Francis “Skipper” Hoste was one of the older officers when at the age of 37 he was commissioned as the Captain of B Troop of the Pioneer Corps. He was born in 1853 at Stanhoe, near Sandringham in Norfolk, the eldest son of the Rev James Richard Philip Hoste, who was later Rural Dean of Winchester Cathedral. He was nicknamed “Skipper” because of his sea-faring background and he resigned his command of R.M.S. Trojan to join the Pioneer Column at the instigation of Cecil Rhodes who he met on board ship.

Like many he hoped to make his fortune in this new country which was reputed to be so rich in gold that it would soon outstrip the new mines on the Witwatersrand…many believed their fortunes were made already! They seriously believed that gold was so plentiful that it could be picked up with no greater exercise than stooping down!

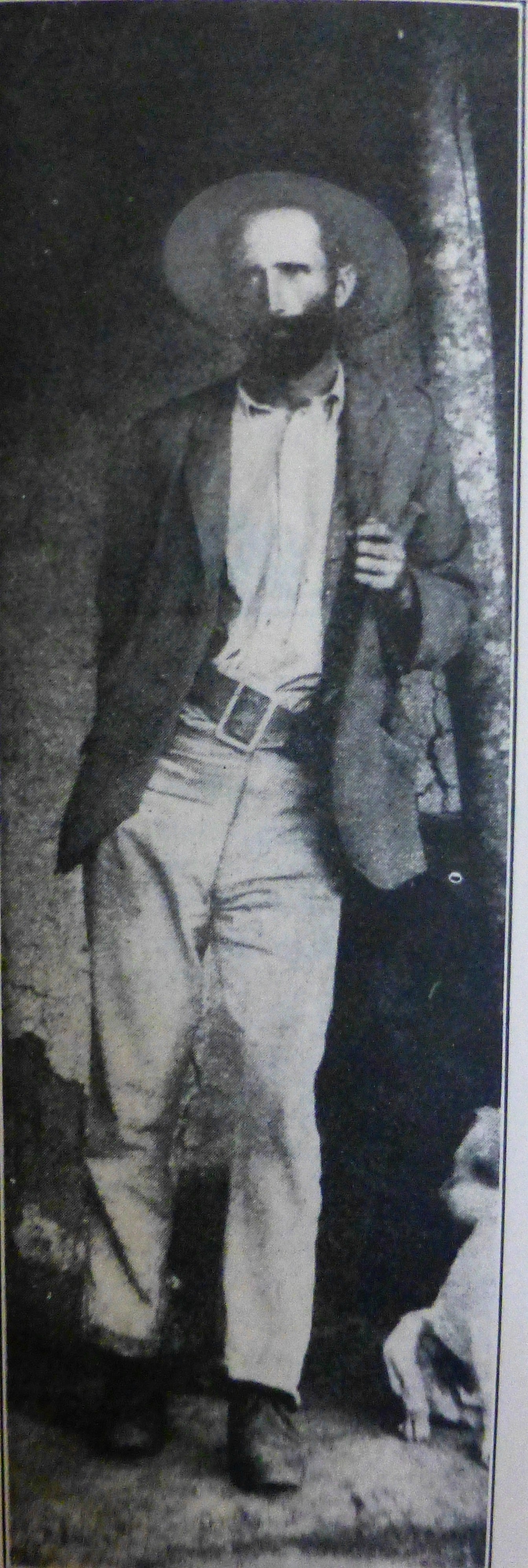

Derick Hoste was his younger brother and had also been at sea; but left and joined the gold rush to Johannesburg to became an “amalgamator” on a big gold mine, before joining the Johannesburg contingent of the Pioneer Column. They met up at Mafeking, then a town of thirty to forty European houses made of wood and iron with the Bechuanaland Border Police headquarters in a big camp just outside Mafeking under the command of Sir Frederick Carrington. Carrington advised Hoste to make the Pioneer Camp a few miles outside the town on the banks of the Molope River. Then Skipper and Derick sat in the shade of a wagon and spent a few hours catching up with each other’s news. Lieut. Henry Borrow arrived the next day with the main body of men.

Skipper’s two other younger brothers, Cyril and Bill, had been sheep farming in Canada, but suffered from drought and sold their farm to go cattle herding in Texas. They wanted to join Skipper and Derick, but would be too late to join the Pioneer Column and Skipper told them to wait until the road was open. Skipper calculated that as he and Derick would each get pioneer farms of 3,000 acres each they would have enough for the four of them; “there was no reason why Cyril and Bill should not get down to a little farming while Derick and I hauled gold out of our chain of mines by the ton. After all, the country was reputed to be fabulously rich in gold.”

Skipper recounts that at Mafeking Lieut. EC Tyndale-Biscoe took the doubtful horsemen and gave them riding lessons, Henry Borrow took the “awkward squad” and had them marching about and he merely rode about and inspected things generally.

One Saturday afternoon Henry Borrow organised a paper chase, and promised, on behalf of himself and Skipper, that every man that reached Isaac’s hotel, where the chase ended, within five minutes of the hares would be rewarded with a bottle of beer. When Skipper said it was a rash promise to make, Borrow said if a couple of men arrived within the five minutes he would be astonished. Wel,l he was astonished, because the hares waited just outside the town until the others arrived and then all rushed in together and demanded their prizes!

It was difficult to describe the optimism with which the twelve officers and ninety rank and file men began their march forward to tame the unknown country to the north. Very few white men had ever ventured into that part of the Dark Continent, apart from big game hunters and missionaries who had come back with tales of a fabulously rich country, literally studded with pockets of gold.

B Troop led the Pioneer Column across the Shashe River at Fort Tuli on 6 July 1890 and began to cut the road for the wagons, their method being for half the men to cut down trees and clear the way whilst the other half led their horses and held their rifles; they swopped places in every few hours.

The Pioneer Column was finally disbanded on 30 September 1890 and within 24 hours the majority had formed themselves into small syndicates and scattered all over the country prospecting for gold, each certain they would make a fortune within 12 months and meet at the Philadelphia exhibition in 1892. Only one of them actually made it and that was because he married a rich woman!

Skipper and Derick with Biscoe formed the syndicate of Hoste Brothers and Biscoe with the express purpose of finding gold and “making a pile.” Their assets comprised 5 horses, a wagon, a span of oxen and supplies for 3 months. They agreed Derick would go to Hartley Hills which were full of “ancient workings” and reputed to be fabulously rich in gold. Biscoe would investigate the Mazoe valley, there were rumours of good looking quartz and gold in the sands of the river. Sir John Willoughby asked to join their syndicate; they were not particularly keen, until they heard he had a wagon and some tools, all useful and rare at the time.

They prospected around their camp at Mazoe, but were depressed not to find any worthwhile gold until they came across a party of Africans who told them of a mountain down the valley called Simoona [Simoona today is a siding on the railway line 12 kilometres from Bindura] which had many “ancient workings.” They broke camp immediately, inspanned the waggons and set off for this El Dorado.

On the way they saw a horseman who turned out to be from the prospecting party sent out by Goldfields of South Africa and who told them one of their party named H. Denny had died in the night. He was the first casualty suffered from the Pioneer Column and died of a heart complaint.

In the evening Biscoe and Hoste went down to the Mazoe River and washed some sand and in half a dozen spadesful found enough gold to cover a silver penny and calculated they could produce half, or even an ounce of gold a day. Ted Burnett and Bowen turned up from a search of the Simoona Mountain and reported numerous “ancient workings.” They had just finished building their camp at Simoona when Henry Borrow turned up with news from Derick saying he thought he was onto something good at Hartley Hills and wanted Skipper to come along and take a look. Next day he left Biscoe at Simoona and went with Borrow and Burnett and two pack horses to carry their kit.

When they reached Hartley Hills, Derick told Skipper that he had wonderful news and had just got back from pegging the Empress reef; “she’s the richest reef I’ve seen yet.” He was full of enthusiasm about the area around Hartley Hills and when Skipper told him about Simoona he could hardly contain himself. “Our fortunes are made,” he exclaimed, slapping his knee so hard he must have left a bruise, “I reckon with just these claims we have now we should net £4,000 for each member of the firm.” Skipper said: “anyway, that isn’t going to last for ever, it may peter out at any time. Whilst we have the country to ourselves we must make the most of our opportunities and peg as many claims as we can before the rush of gold seekers begins and this freedom ends. In a few months this country will be swarming with prospectors falling over one another to get at the gold.”

Where was the Empress claim? “Over there across the Umfuli” said Derick, pointing with his pipe to the country to the south west, “as far as I know that’s never been explored. I have a feeling we’ll find rich reefs there.” Skipper objected: “but that’s fly country, we can’t take horses and oxen in there,” referring to the dreaded tsetse flies, whose bite carried diseases fatal to domestic animals. “No, that’s why it’s not been explored yet. But I’ll eat my hat if there aren’t some very rich seams over there.”

They spent the next few days prospecting around Hartley Hills before crossing the Umfuli River (now the Mupfure) to investigate Derick’s theories, taking four Mashona with them as carriers. They were rained on very heavily and had several close encounters with lion; and during one Skipper had to take to a tree for safety. They found “ancient workings” with some quartz reef showing visible gold and pegged off ten claims which they named the “Harvester” after John Willoughby’s horse which had run a dead heat at the Derby a few years previously.

Near what were called Concession Hills years later, they located more “ancient workings” and pegged another ten claims named the “Wanderer” after a steam yacht Skipper had commanded several years before.

“D’you know, Harry” Derick sighed, collapsing into a chair when they got back to his camp, which was on the top of the highest of the Hartley Hills, “I’ve never felt better in my life.” Skipper replied; “what did I tell you, this is the healthiest country in the world.” “D’you think it is the lost land of Ophir?” he asked. Skipper replied: “I’m sure of it, look at all these ancient workings we’ve found in the last couple of days. The place is riddled with them. And as for that mountain down in the Mazoe Valley, Simoona – why it’s been practically hollowed out.” Derick said “I wonder what made them leave so suddenly?” and Skipper replied: “Goodness knows, there’s still plenty of gold left in the ancient workings – most of them, anyway. Let’s hope we come across some old tools or something left in some of the old shafts which will give us a clue as to the original owners of this country.”

Skipper spent a couple of days helping Derick build a hut on the top of his hill. He had a magnificent view from there and as his nearest neighbour would be the Mining Commissioner, whose house was to be built on the lower plateau, he was not likely to be crowded. Whilst Skipper was there Colquhoun the Administrator, came to look at the place and installed Woodthorpe Graham as the Mining Commissioner.

On his return to Salisbury, Colquhoun asked Skipper if he would take some despatches to Capt. Forbes who was negotiating with Chief Mutasa in Manicaland over his treaty with the BSA Company which the Portuguese were trying to make him repudiate. These he took with Tyndale-Biscoe and spent several very wet days on the journey. Near Makoni’s kraal, east of Rusape they met fifteen BSA troopers under the Hon. Eustace Fiennes on to their way to reinforce Forbes’ two officers and ten men. Soon after crossing the Odzi River they met some of Mutasa’s men who told them the Portuguese were very angry and would undoubtedly kill them.

They found Forbes camp at the base of Chief Mutasa’s mountain stronghold. The story of the capture of the Portuguese representatives Colonel d ‘Andrada, Gouveia and the Baron de Rezende will be left for another article.

On 20 December 1890 Biscoe and Skipper were sitting on their hut verandah cleaning their rifles and discussing how they were going to spend Christmas when Derick Hoste arrived with two carriers. “Well, I’m sorry I can’t offer you a drink” said Skipper, “we’ve been out of the stuff for weeks – months, in fact.” “Not to worry” said Derick, “I’ve brought some whiskey with me and also took the liberty of bringing some cigars.”

The next day the Portuguese commandant, Capt. Bettincourt arrived and Skipper escorted him to the police camp at Fort Hill in Penhalonga. Biscoe and Derick then arrived and they spent Christmas Day with the Police Officers. There was no turkey, but he says they had a noble thing in the way of plum pudding. There had been a rumour that it had been boiled in the cook’s shirt, but as it didn’t come to the table with the shirt on, nobody minded!

On Boxing Day Skipper and Pascoe moved into the huts built by the mining engineer Mr Campion. In all probability this is Sabi Ophir Hill at Penhalonga about 500 metres from Fort Hill across the Mutare River and where the three nurses, Rosanna “Rose” Aimée Blennerhassett, “Sister Aimée” Lucy Anna Louisa Sleeman “Sister Lucy” and Bertha Anne Welby “Sister Beryl,” the first three trained nurses in the country stayed whilst the hospital at Fort Hill was being constructed [see the article “Nurses Memorial” under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Skipper and Biscoe were asked by Capt. Heyman to find a suitable drift across the Odzi River and cut a road to Umtali. Selous was at the same time cutting a road from Salisbury and Skipper swam the flooded river and camped the night with Selous. Derick had already left for Salisbury.

Biscoe and Skipper arrived back in Salisbury to see the end of a cricket match between the BSA Police and a Rest of the World team. Skipper met Col. Pennefather who said he had meet his two brothers, Cyril and Bill, stranded on the flooded Nuanetsi and thought with their poor oxen and driver it might take them another three months to get to Salisbury.

Their ride back to the kopje took them across the Causeway and the water came up to their horses’ girths; fifty-four inches (137 cm) of rainfall being measured in the 1890-1891 rainy season.

Skipper says living with Biscoe and Derick was like living in the same house with a hurricane, they were always hatching up something. But before the rain came to an end and they could resume their mining operations they decided to rescue their brothers. Their oxen were knocked up, Derick was still recovering from fever, so Skipper decided to construct a scotch cart and take a span of ten oxen. They cut down trees and used Frank Johnson’s saw mill to make planks and constructing the cart took a week. Skipper left for the south leaving Biscoe and Derick building a sleeping hut big enough for all.

It took eight days to reach Fort Victoria and transport-riders informed him his brothers were on the north bank of the Nuanetsi. Next day he set off at dawn and two days later was on the north bank of the Lundi River. He says; “there must have been 50 and 60 wagons collected around the drift on one side of the river or other. Sick and exhausted men lay about in the shade of the trees and under wagons, while a few who had enough strength left hobbled around trying to collect enough dead wood to make a fire. The place looked like a battlefield.”

Skipper walked down the steep bank to the water where he found the BSA Company had sent up a boat and a provided a blue-jacket to ferry people across. The blue jacket directed Skipper to a large tree about two hundred yards or so from the river where he found his brothers sitting in the shade of a tree looking very disconsolate. Cyril looked yellow, lean and fever stricken, but Bill was comparatively fit.

They immediately moved all their kit to the north bank of the Nuanetsi. Both brothers found climbing the north bank as much as they could take and once they reached the scotch cart were given a dose of rum with quinine. As the brothers talked around the fire that evening Skipper couldn’t help but think of all the living skeletons he had seen that day, staggering drunkenly around the camp, their heads spinning and buzzing with fever. When they had started out their journey they had been strong, healthy young men. Now they were hardly able to put one foot in front of the other without falling over.

Bill told him: “I thought the fever season was over, but I soon found out my blooming error. About three days afterwards it came on to rain down in torrents and both Cyril and Max Lambert got the fever again. Max was lucky, he only got it slightly, but Cyril got it most awfully badly. I hardly dared leave him for a minute. It took me all my time to nurse the two of them and do the cooking…out of a camp of forty-five men, only myself and three others were without fever.”

Then Cyril took up the story: “We had hard times coming along the road from Nuanetsi. A wagon that was travelling with us got smashed to bits in a mud hole and one man died in the night. Then about fifteen miles from here the owner of our wagon died. Then when we got here the owner of another wagon that was travelling with us died.” He knocked the ashes out of his pipe and then continued; “we had travelled a good deal of the road with him and had got to know him very well.”

There was silence for a moment and we all stared at the fire, each absorbed in his own thoughts. Then Bill went on: “I was getting firewood that night when we got to the Lundi and I came upon the grave of a fellow I knew most awfully well when I was in the Police. It gave me quite a shock.”

Early next morning Bill and Skipper went back to across the river to see if anything was left behind in the wagon. On the way back they passed a small bell tent standing by itself and noticed a man’s leg sticking out from under the wall of the tent in a very unnatural position. They looked inside and found a dead man lying on the floor, and besides him, completely unconcerned, a couple of men eating their breakfast.

One of them explained: “it’s poor Tom, he died in the night. We’re going to bury him as soon as we’ve had our scoff.” Skipper asked him if he could help in any way and the reply was: “no thanks very much, we’ll manage all right.” Such was the casual way that death was treated by those that came into daily contact with it.

As soon as they finished breakfast the oxen were inspanned for the return journey. Skipper writes: “I was not sorry to see the last of the Lundi. I don’t think I ever saw so many miserable looking people gathered together in one place as I saw in that camp. There were several hundred of them and nearly all were yellow, hollow-eyed and fever-stricken. There were four graveyards, two on either side of the river, one for white men and one for black and coloured. Hardly a day passed without one or two deaths, sometimes more.”

Skipper says those down with fever were “as yellow as guineas” with lack-lustre eyes that showed they were all rotten with fever. Nobody knows just how many men died between Fort Tuli and the Lundi River, nearly every wagon lost at least one or two. The wagon his brothers travelled on lost four men and he heard that on one wagon with sixteen Italians, not one survived.

On their arrival at the top of Providential Pass, Bill said: “you have no idea what a relief this is after wading through miles and miles of swamp. This air, it bucks you up like wine.” The party arrived back in Salisbury on 15 May 1891 after covering a record 730 kilometres in thirty-one days.

In the meantime Biscoe and Derick had built a long dormitory house on the side of the kopje with eight beds and four huts which served as kitchen, dining-room, stable and servant’s quarters, all surrounded by a grass wall. The wagons they had passed on the road now arrived and Homan’s was the first store to be set up in Salisbury. They opened at 6am and by noon their entire stock, made up of jams, potted salmon and tin goods, were all sold out.

On 1 June 1891 Derick, Cyril, Bill and Lambert left for the Lomagundi district or “Northern goldfields” in the area their friends, Arthur and Herbert Eyre, had claimed a Pioneer grant farm “Kilmacdaugh” on one of the major passes through the Umvukwes range just north of where the modern Harare-Chinhoyi road passes through the Great Dyke. Then Biscoe returned from Manicaland with news that the Portuguese fort at Macequece had been blown up and left with Skipper two days later and they soon came up with Derick and his party stuck in a swamp at the foot of the Umvukwes Hills. Two days later they arrived at their two blocks of claims called the St. Valentine and Blue Peter which Derick had pegged a few months before. They built camp and began to sink a shaft on the St. Valentine.

Next day Skipper went hunting, he missed a tsessebe and chased it on his horse which took a tumble when it stumbled it a hole and dragged him along for about 20 yards with his foot in the stirrup.

A few nights later they had a night alarm. There was a lot of meat out drying to make biltong, and hides pegged out on the ground. Their dog Vic woke up everybody except Biscoe who was sleeping in the wagon. It was pitch black and as Skipper thought it was a hyena, he took a shotgun and walked out of the hut. Then he heard a throaty growl and knew it was a lion; quickly retreating back to his hut and smoked his pipe with Derick. Then Biscoe woke up, but none of them heard anything more until Biscoe knocked out his pipe on the side of the wagon, when pandemonium broke out. The hot ashes had evidently fallen on the lion’s back! Biscoe followed up with a shot and the lion scarpered.

The next night they had all their rifles close and a fire in front of the hut as it had no door. The lion returned three times that night and Biscoe may have wounded him as he dropped a hide he had snatched, but was not seen again.

Bill and Skipper were working on the St Valentine claim. They dug a shaft and then drove tunnels 8 metres to the north and 3 metres to the south, but lost the reef. This and the Blue Peter reef were not coming up to expectations, so they decided to transfer to Salisbury. Biscoe, Cyril and Skipper left for Salisbury leaving Derick and Bill to check the claim pegs and follow on.

On their arrival in Salisbury there was bad news. Bill Lambert had died from fever. Mother Patrick and her sisters and Dr Rand had done their best. Skipper says he made a big gap in their party. He was a fine youngster, as straight as a die, a fair shot and a good horseman; just the sort of man for a new country.

In Salisbury they met Lord Randolph Churchill, but he made himself very unpopular and was nicknamed “Grandolph.”

At the beginning of September they all left for Hartley Hills, except Cyril who was rethatching their huts before the rains. At Hartley they met Ted Burnett, the Pioneer Column transport officer, who was leaving for a while and offered his camp of two huts and a cattle kraal near the Phoenix Reef which they had pegged the year before. They had the help of eight natives from Mozambique that Biscoe had sent up and dug a trench to locate the reef before digging a shaft.

Fetching water was time wasting with the Mupfure River a kilometre away, but Ted Burnett’s shaft close to camp filled with clean water and this was used. Then they all began to suffer from terrible headaches and only when Derick and Bill returned from buying grain did they notice the water smelt of dynamite. They subsequently discovered that Ted Burnett put his tools and unused dynamite at the bottom of the shaft when it was dry, but it subsequently filled with water!

Their shaft at the Phoenix Reef filled with water as soon as they reached 20 feet and as pumps were unobtainable, they moved to the Cumberland Reef about 6 kilometres away. This too was quickly abandoned as no payable reef was found. Skipper then built a camp at the Harvester Reef in the tsetse-fly country near Concession Hill. Derick and Bill brought the scotch-cart with their kit at night and then had it out of the tsetse-fly area by morning. Despite these precautions, all the oxen died when the rains came, one by one.

The Harvester Reef was getting good values when panned, but none of their workers would stay more than a month. In the end, two of the Hoste brothers would work at the windlass whilst another picked and shovelled in the shaft and the fourth did the hunting and cooking; this was the easiest role as the bush was full of game. They worked on the Harvester Reef until the end of November and then left for Salisbury before the Mupfure and Manyame Rivers became impassable.

They spent a jovial Christmas in their dormitory hut which had been divided into bedrooms and a living room in which various mounted animal heads were mixed with assegais and knobkerries and gave the place quite an atmosphere. On Boxing Day they had a race meeting, the first in the country, behind the kopje and which everyone in town attended. Skipper had intended to race Trumpeter, but scratched him as he says he was fat and lazy. Instead he acted as assistant starter to Frank Johnson. Trumpeter got excited when the horses raced off; Skipper says it would have been embarrassing to come a cropper in front of the entire population of Salisbury!

There was also a shooting race which Selous was strongly tipped to win. But when the three lead contestants dismounted to shoot; their horses got excited and bolted leaving their riders stranded in the veld. Bob Coryndon had a club-footed pony which Skipper says could not go faster than a cow, but won the race because he was the only one that finished!

Lord Randolph Churchill complains in his book of this race that the horse he backed to win was nobbled and could only stagger a few metres from the start before giving up!

At this time when everyone was feeling somewhat downhearted about their gold prospects, Frank Johnson and Henry Borrow returned from their Mazoe Valley properties saying when their shafts were down to 18 metres the the quality of the payable ore improved. Johnson persuaded Skipper that more finance could be raised through a syndicate to carry out the development work on their properties and so they travelled via Beira to Cape Town.

At the Sabi River, Johnson left their gold samples from the Salamander Mine at Hartley in a box under a tree; they had to race back after several hours to retrieve it. At Christmas Pass he disturbed the sable antelope that Paddy O’Toole was stalking. [O’Toole won the Victoria Cross at the battle of Ulundi in the Zulu War, but very little more is known about him, or the whereabouts of his medal]

At Sarmento on the Pungwe River in Mocambique they came upon wrecks of numerous ox wagons which had belonged to Johnson, the oxen had all died of tsetse-fly and so they built a raft from some of the wood. Building took three days and after launching they had only travelled a hundred metres before they hit a snag which turned the raft over and plunged everyone into the river. They crawled out the Pungwe like drowned rats, but all their supplies and rifles were at the bottom of the river and the raft floated on without them!

Johnson had arranged for the Agnes, a little river steamer to come up river and collect them, but with the Pungwe River flooded, it had lost its way and grounded. They went down to Beira in the flood tide in a large six-oared whale boat and after further mishaps and adventures finally reached Cape Town.

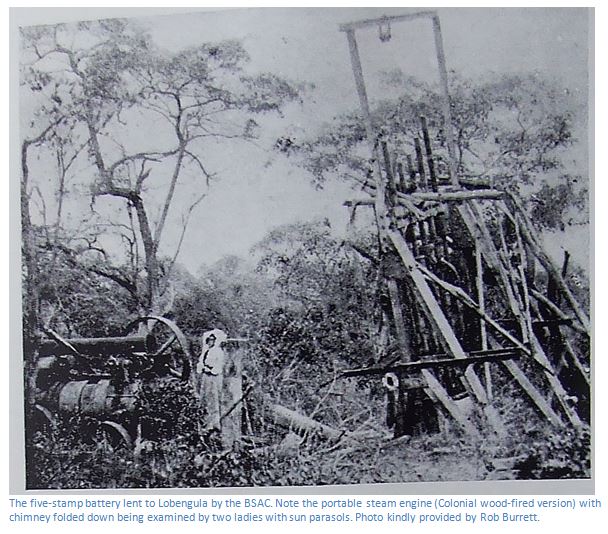

However Skipper had no success whatsoever in financing a syndicate to develop their gold mines and with Biscoe returned to Mashonaland via Beira again, but this time without any major mishaps. Derick, Cyril and Bill were managing a mine called the Bonanza at Hartley Hills. Towards the middle of 1891 Lobengula heard there were two five-stamp mills at Hartley Hills and asked the BSAC for a mine and mill so he could find gold. The BSAC agreed to lend him a second-hand iron framed five-stamp mill, boiler, engine and pump for the Bonanza Reef next to the Mupfure River. Everything was very old, but the boiler had been repainted a brilliant green with the name Lobengula painted in gold letters on each side.

Initially James Dawson, the trader, was in charge of the team of amaNdebele workers at the Bonanza Reef. They only ran day shifts with the boiler running down at night, but one night was cloudy and the boiler stoker woke at midnight, thought he had overslept and fired up the boiler. Pressure built up and steam blew out the safety valve. He knew the steam, which he called “smoke” powered the mill and was afraid if it escaped he would lose it all. So he threw some sacks over the safety valve; when that didn’t work, his trousers and then his shirt and then sat on top of it himself.

Dawson laughing told him to come down, the moment he did so his clothes were blown off, and Dawson threw the furnace doors open. Lobengula got little gold and soon tired of his new toy, returning the mill to the BSAC. Jameson wanted someone else to continue running the mill and Derick Hoste volunteered. The Bechuanaland Exploration Company’s mill nearby had just ceased to work because of a shortage of water and Jameson pleaded with them to keep the Bonanza mill running.

Next day Skipper and Biscoe left for Hartley Hills to find Derick and Bill running the mill night and day and Cyril doing the mining. Derick told him it was averaging about five penny-weights (nearly eight grams) of gold to the ton of quartz and whilst they wouldn’t make a fortune, it should cover expenses. The mill, boiler and engine Derick described as nothing more than wrecks with about a 50% recovery rate. They ran the mill for thirty-six days and then stopped for a clean-up, but calculated after stoppages for repairs they had milled for just over fifteen days. They obtained thirty ounces of gold meaning they were getting just two and a half pennyweights per ton.

They had a look at the Bechuanaland Exploration Company mill which was situated near a creek of the Mupfure River and only filled with water in the wet season. There was no piping available, but they estimated they could dig a trench to bring water up to the mill and hired it for £50 per month. Jameson sent a fitter to patch up “Old Lobengula” whilst they dug the trench and got both mills going within a few days of each other. They struggled on to the end of November; however what profit they made on the B.E. mill they lost on “Old Lobengula.” The B.E. mill was sold to the Dickens Mine at Victoria and “Old Lobengula” was left a hopeless wreck. Derick expressed their feelings as they finished their last shift saying: “Thank God that’s over. The next man that offers me a mine and mill, I’ll shoot on sight.”

Salisbury was no longer being called Fort Salisbury and the town had grown. The telegraph had arrived and some women, new stores had opened, but the businesses that thrived were the pubs. Skipper says without exception he never saw such a drunken town as Salisbury. His brother Bill said Fairmont in Canada had a reputation as a “wet” town, but declared that a Fairmont habitual drunkard would pass as a sober, steady-going citizen in Salisbury!

With the onset of the rainy season mining operations ceased and Bill and Skipper decided to visit England, their mother had not been well and perhaps raise some funds to develop their claims. Both were suffering from the attacks of fever and looked forward to being at sea again. They had an eventless journey down, taking the Beira Railway for part of the journey and at Fontesvilla catching the tugboat Kimberley to Beira.

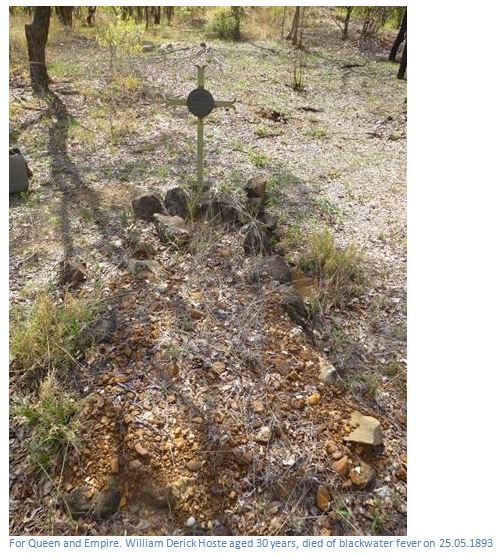

They spent three months in England, but were saddened by the death of their mother. The RMS Scot took them from Southampton to Cape Town in the record time of 14 days, where they learned of the death of their brother Derick.

He had taken Arthur and Hubert Eyre on a prospecting trip to Hartley Hills where they found the Mining Commissioner Ferguson very ill with malaria. Derick sent a runner to Salisbury to ask Jameson to send out a Doctor and began to nurse Ferguson. Ferguson began to mend and Derick went down with malaria. The others dosed him with quinine, but he got steadily worse and by the time the Doctor arrived Ferguson had recovered, but Derick had died of blackwater fever on the 25 May 1893.

Backwater fever is a less common, but dangerous complication of malaria and has a very high mortality rate of upto 50%. The disease’s name comes from the passage of urine that is black, or dark red in colour due to the destruction of the patient’s red blood cells by malarial parasites. Individuals most likely to suffer are those who have had at least four attacks of malaria and have been in an endemic malarial area for six months. Modern day treatments which include antimalarial drugs and whole-blood transfusions were simply not available in the nineteenth century.

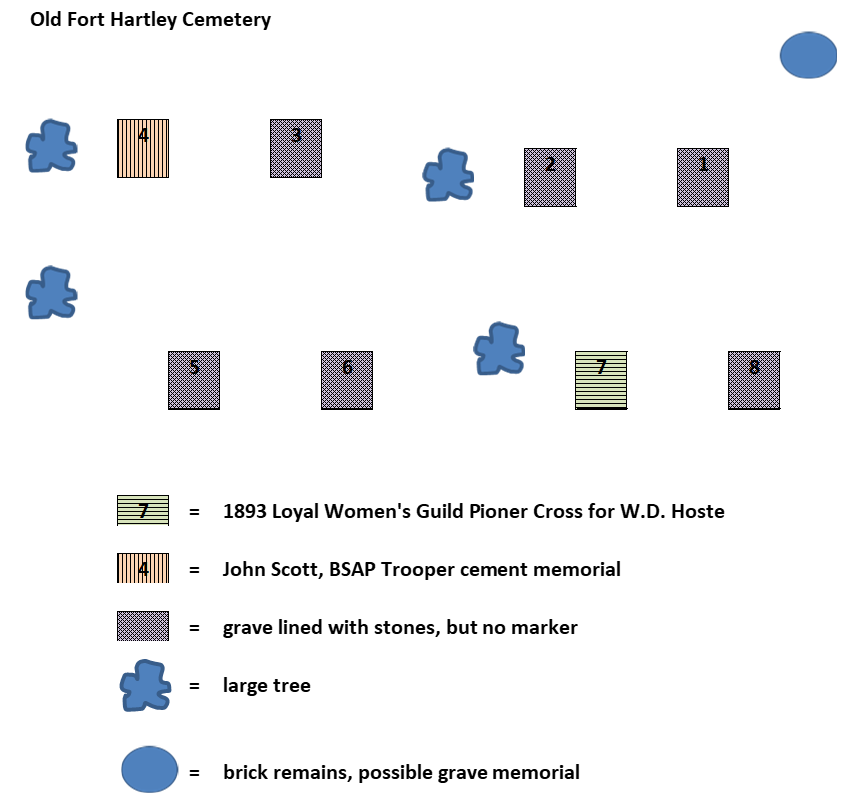

Those listed as died at Old Fort Hartley cemetery include the following.

| Burials at Old Fort Hartley Cemetery | ||||||

| Grave | Surname | Name | Title | Date | Reason | |

| 1 | Livingstone | William Kinloch | Trooper, BSAP | 1 January 1897 | Fever | Note 1 |

| 2 | Overstall | Frederick | Trooper, BSAP | 11 February 1897 | Fever | |

| 3 | Butcher | Harry | Trooper, Natal Troop | 16 February 1897 | Fever | |

| 3 | Tenant | Robert | Hospital-Sergeant, BSAP | 26 February 1897 | Fell off a rock and killed | Note 2 |

| 4 | Scott | John | Trooper, BSAP | 22 March 1897 | Fever | |

| 5 | Foster | John Lowry | Trooper, BSAP | 23 March 1897 | Fever | |

| 6 | Sims | George | Trooper, BSAP | 2 April 1897 | Fever | |

| 7 | Hoste | William Derick | Prospector | 25 May 1893 | Fever | |

| 8 | Jay | Edgar | Corporal, BSAP | 27 Dec 1897 | Fever, died at Makori | Note 3 |

| Some details are from The '96 Rebellions BSA Company Reports | ||||||

| Note 1: The '96 Rebellions state 12 January 1897 | ||||||

| Note 2: The '96 Rebellions state 26 July 1897; but if there are two burials in the grave, the February date makes more sense | ||||||

| Note 3: Ken Flower letter states date of death and reason unknown, but The '96 Rebellions have details | ||||||

Derick Hoste has the cast iron marker because he was a Trooper in B Troop which his brother Henry Francis “Skipper” Hoste commanded. The remaining victims of the Hartley Hills cemetery are from when the fort was re-occupied by the BSAP from December 1896 to February 1897 and all their markers are missing.

J. Scott is listed as Trooper No. 503 in Col. Hickman’s Men who made Rhodesia. He attested on 4 May 1890 serving in C Troop in the Pioneer Column and was discharged from the force on 30 November 1891 and must have signed up again before his death on 22 March 1897. His grave is the only one we can be sure of, as his name has been recorded in cement.

The BSAP compiled lists of the names of those buried at each site around the country before 1908. Lists were then drawn up by the Guild of Loyal Women (GLW) that were sent to be cast as the familiar circular cast iron markers by the Gregory iron foundry in Cape Town. Those who died prior to the death of Queen Victoria on 22nd January 1901 are headed “FOR QUEEN & EMPIRE” and those after are “FOR KING & EMPIRE.” The BSAP then placed the grave markers, but not always on the correct graves; so the current positioning of the grave markers should always be treated with caution, including that of W.D. Hoste.

The Hoste brothers went off to work their claims at Simoona, Biscoe joined the Salisbury Column; Skipper’s old friend Ted Burnett was killed between Gweru and the Shangani River. Cyril went back to England and Skipper, Bill and Biscoe worked the Vesuvius Mine in the Mazoe Valley.Before the 1893 invasion of Matabeleland began, both Arthur Eyre, Derick’s chum, and Skipper Hoste were offered commissions, but they heard that each man was only allowed 3 kilograms of kit, barely enough for a blanket, but not for a change of clothes. They saw Capt. Forbes who remained adamant that this was the limit, so both refused to enlist on such terms.

Herbert Hedges Eyre was killed in one of the earliest events of the Mashona Rebellion on the 21 June 1896 aged 28 at his farm . His brother Thomas Arthur Eyre, a great friend of Derick Hoste, died on 9 March 1899 aged 39 and Skipper Hoste was one of his pallbearers.

Arthur Eyre

In 1897 Skipper Hoste returned to England and married Florence Eugene Clark, who had previously been engaged to Derick Hoste before his death. Together they lived quite a rough and ready life moving about on varuious gold mining locations before finally settling at Essexvale (now Esigodinin) where he was a cattle inspector and died in Bulawayo in January 1936.

The drive up Harare kopje is named after Skipper Hoste.

Acknowledgements

H.F.Hoste and edited by N.S. Davies. Gold Fever. Pioneer Head. 1977.

R. Burrett. The Eyre brothers: Arthur and Herbert. Heritage of Zimbabwe publication No. 9, 1990.

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

Not applicable

Category:

Province: