Operation Noah Memorial

- Rupert Fothergill and his teams rescued thousands of wild animals as Lake Kariba filled up and the animals were forced to higher ground which eventually submerged.

- They pioneered many of the rescue techniques that are in useby wildlife vets today.

- For a short period the efforts of the small teams with very limited resources attracted the attention of the world's press

The Operation Noah Memorial is at the top of Kariba Heights overlooking the lake. Take Heights Drive and park at the Kariba Heights viewpoint.

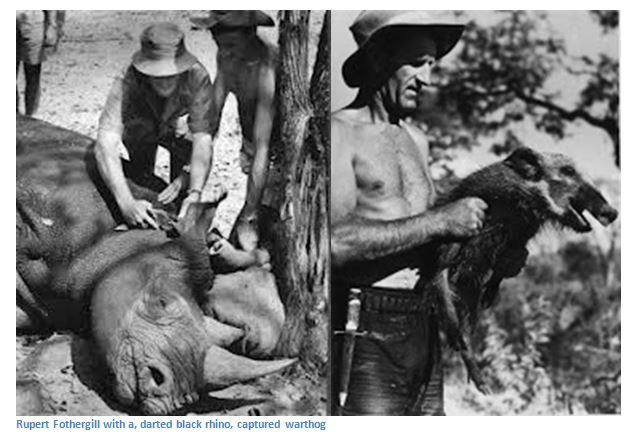

Few outside of conservation circles know the name Rupert Fothergill today, or remember the extraordinary effort when Kariba Dam filled from 1959 to 1963 that he and a few others made and the hardships they endured to rescue nearly 6,000 animals as well as requiring the forcible relocation of the indigenous Batonga people. The Batonga - 50,000 strong - were dispossessed and resettled on far inferior lands in the name of progress. With the exception of Keith Meadows excellent biography Rupert Fothergill; Bridging a Conservation Era published in Zimbabwe in 1996 which really captures the effort to save African wildlife from drowning in the waters of rising Lake Kariba over four gruelling years against impossible odds there is little to remind us of Fothergill and his conservation legacy. Many of the photographs below featuring photographs of Fothergill's wildlife rescue effort come from Life Magazine of June 29, 1959.

When the sluice gates that were used to dam the Zambezi River were closed, the water started rising, within 24 hours the level had gone up by six metres and by September 1959 it had risen by sixty metres. Alarm bells started ringing when it was realised that many animals were being marooned on hilltops that overnight became islands and then slowly, but surely, also began to disappear under water. Wildlife rescue efforts happened almost as an afterthought and in the beginning were an ad hoc affair. Many animals began to starve and die, until Operation Noah was mounted to save the animals that were still stranded on the shrinking islands as the lake filled.

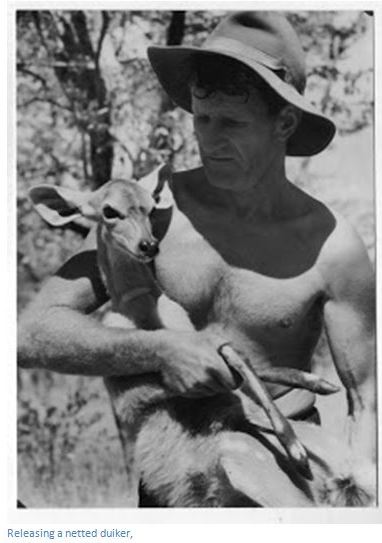

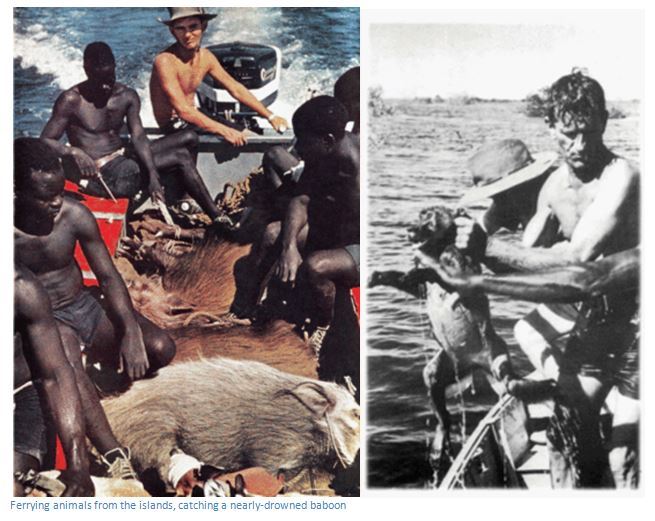

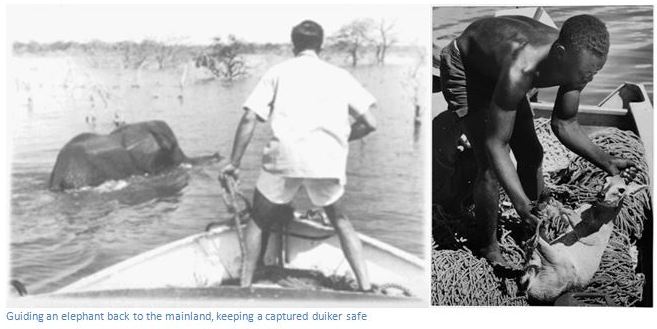

To rescue them, Operation Noah was organised to rescue the animals from the fast submerging islands and in a gigantic and unprecedented effort, that caught the imagination of the world, a gallant team of rangers from Zimbabwe’s National Parks and volunteers, led by Rupert Fothergill, rescued more than 6,000 animals between 1958 and 1964 in Zimbabwe, including elephant, rhino, lion, zebra, antelope, warthog and many other species were rescued, even many snakes including the deadly black mamba; while the Zambian team rescued about 2,000 animals. Sadly many of the animals they were unable to rescue perished, and as a result, one of the largest islands on Lake Kariba is known as Starvation Island.

Fothergill and two colleagues from the Southern Rhodesia Game Department were given the assignment to "take such measures as they thought necessary to save animals from the rising water." They had little besides a couple of commandeered boats, some rudimentary equipment, and their own ingenuity and the skills of their small team of Game Department employees and volunteers to meet this unprecedented challenge. Nets, boxes, sacks, cages, traps, ropes, drugs, darts and fuel for the boats and food for the team were assembled. The valiant band soon captured the hearts and minds of the citizens of Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and the British Sunday Mail brought the mission worldwide publicity and offers of funding.

However it continued on a shoestring budget and when Fothergill and his team noticed that ropes cut into the legs of the bound animals he sent out a plea for nylon stockings. When the stockings were plaited they provided a strong but soft alternative and the SPCA were deluged with stockings.

Many animals can swim quite long distances and they were escorted by boat to a non-hunting area on the mainland; while those that could not swim were trapped on the islands in nets, or into the water for easier capture. Keith Meadows writes: "For five hours he had been swimming, and he was a long way from any land now. And he became frightened. The aching tiredness brought fear, for it was becoming almost impossible to keep his head up and the tip of his trunk clear of the water. The tip had taken on a pale, almost bluish pallor. And the old bull began to flounder, the confusion and fear amalgamated into panic. His tusks were beginning to pull him down. "At first the old bull fought, smelling the smell of man, desperate against this new enemy as well as the water. But he was exhausted and his struggles diminished. The rangers improved their initial rope supports around the huge head, manoeuvring their launch so that the elephant was up beside the bow, tusks pointing ahead, away. The trunk was held aloft so he could breathe. And slowly, very slowly so as not to create too much of a bow wave, they guided the elephant back across the flooded country to dry land."

Fothergill and his vets pioneered the use of tranquilizer darts to subdue big game such as buffalo and rhino Then they were roped, trussed on stretchers and hauled by gangs of rangers to the lake shore, slid onto raft pontoons made out of 44 gallon drums strapped together and scrounged from the dam construction site; they were floated to safety on the mainland. 43 rhino were rescued during the nearly five-year effort, many through these techniques.

In 1959 they saved 1,700 animals, from birds and reptiles to large mammals, but also recorded the loss of 529 animals, drowned or succumbing to shock or shot because there was no way to save them. Time Magazine described some of the techniques of that the "three white game wardens and eight native trackers" used: "To capture the deadly black mamba, the wardens use a fishing rod adapted to pull a noose around the snake's neck; the snake is then gingerly deposited in a pillowcase. Dassies (rock hyrax)and porcupines are deliberately driven into the water since, despite their small size, dassies bite when cornered and porcupines have quills. Even in the water, it takes three men to outwit a porcupine."

Many rescued animals were relocated to the Matusadona National Park and around a large part of the southern shore, as well as some of the islands which are nature reserves, thus saving a large variety of animals and birds. Today due to this past great effort crocodiles go hunting, hippos rise out of the water to graze in the cover of darkness, elephant splash in the lake and fish eagles circle over the water, their wild and beautiful call echoing far and wide.

Time Magazine admired the tenacity and dedication of small band of rescuers, but took the colonial authorities to task for their negligence and disregard for the consequences of the dam for wildlife in the flooded region that created the crisis in the first place. "The government of Southern Rhodesia is being censured for having done too little too late to save the Kariba animals. But the government of Northern Rhodesia, across the lake, has done even less.

Starvation Island - represented the final and in some ways most difficult task of Operation Noah. It covered 5,000 acres and was initially too big for a game drive and yet crowded within its thickets were 200 buffalos, 11 rhinos, 4 elephants and 11 lions as well as countless other species. The elephants and lions were chased off into the water and swam to shore, but the rhinos and the rest needed to be subdued and removed. 200 animals were eventually relocated - many others perished.

Keith Meadows describes in his book the risks that the rangers took to capture the starving animals: "A few buffalos had been removed before the starvation crisis reached its peak. Rupert's team...removed five adults. Then they ran out of drugs for the darting equipment and there was no response from Salisbury as to when new supplies would be arriving. So Rupert went after the buffalos with the Land Rover. In the gloom of the dust pall, amidst the snorting, lumbering, desperate animals, they looked for targets. As the younger animals slowed and dropped behind, the men would race from the vehicle and bare handed, through force of numbers and in desperation at the plight of the game, wrestle the buffalo to the ground. Then the creature would be trussed up and carried to the raft. More often than not the bellows of the calves would bring angry mothers charging back and a free-for-all would ensue."

Throughout the Kariba crisis, a vast store of knowledge was amassed about wildlife habits, particularly the response of various species to the flood and their swimming capabilities and many ground-breaking capture techniques developed through trial and error. Mostly, it was grit and determination by a small band of white and black Africans who managed to salvage something good out of all the destruction.

Rupert Fothergill moved with his family to Southern Rhodesia (modern Zimbabwe) in 1922 when he was 10. He and his two younger brothers served during World War II in the South African Division for five years and afterwards established an engineering business in Mutare. However he spent as much time as possible in the bush, prospecting like his miner father before him, tracking game, or just sleeping beneath the stars and in 1955 at the age of 43 he applied for a job with the fledgling Game Department of Southern Rhodesia.

Rupert Fothergill died in 1975 at the age of sixty-two, but his name lives on as Fothergill Island and there is an Operation Noah Memorial at Kariba Heights to celebrate the achievement.

Acknowledgements

Keith Meadows. Rupert Fothergill; Bridging a Conservation Era. Thorntree Press. 1997

Life Magazine. June 1959