O.C. Rawson (1874 – 1953) of Darwendale

The following story of Otto Christian Rawson[i] ‘O.C.'s’ early life in Darwendale is taken from a short manuscript which he gave the late Pat Wise of Banket and was printed in The Legend of Lomagundi booklet referenced below.

In those early days (wrote OC) our cattle grazed on the plains with elephant among them by day and unwelcome visits by lions at night. Sometimes a leopard would take a hand in the game. Cattle were valuable so the marauders who haunted ruthlessly by night and followed up by day.

We bagged 29 lions at Darwendale - and many more leopards before this menace was overcome. The lions and the hyenas were not long in quitting, but the leopards and jackals, attacking the calves and the lambs, remained troublesome.

O.C. went north to Central and East Africa to look for cattle, while Dimmock ‘experimented with almost every known crop.’ There was little success with the small grains such as wheat, barley, sorghums and with clovers and root crops and the green crops also failed. Then in 1903, O.C. returned with hopes for sisal hemp, ‘then beginning to be planted extensively in East Africa.’ There were good reports from the Imperial Institute in London on the quality of the Rawson crop, but the scarcity and high cost of Labour, plus high transport charges, killed the small industry. While these experiments were going on, O.C. found that a new menace had developed.

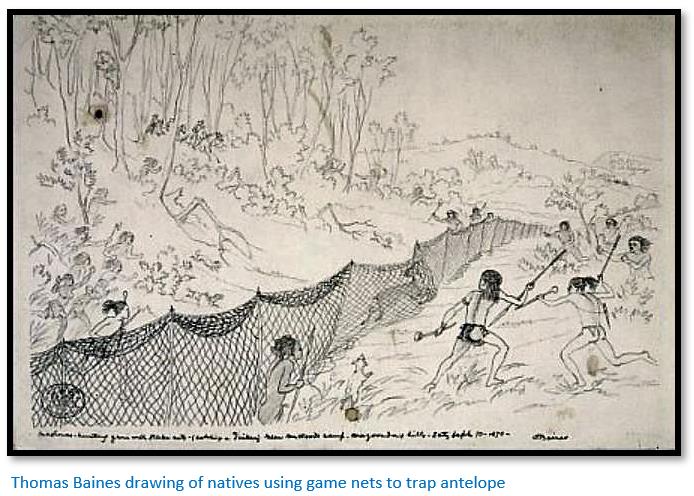

Baboons invaded our maize field and try as we would, we could not kill them. And then we saw, from very close observation, that the baboons did not appear to be able to count to three. If two of us walked into a maize field and one came out, nothing would induce the baboons to enter the field. If two came out, the baboons were hesitant. If three went in and two came out the baboons would, after a little prospecting, go into the field - and we had a chance of killing one or two. But they were many. We realized that we would have to take strong measures to check these vermin, or we would have to give up all attempts at crop cultivation. The baboon troops were increasing as we were killing the lions, and especially the leopards, which were their natural enemies. So, we enlisted the help of Chief Zvimba and his people - and the use of their game nets.

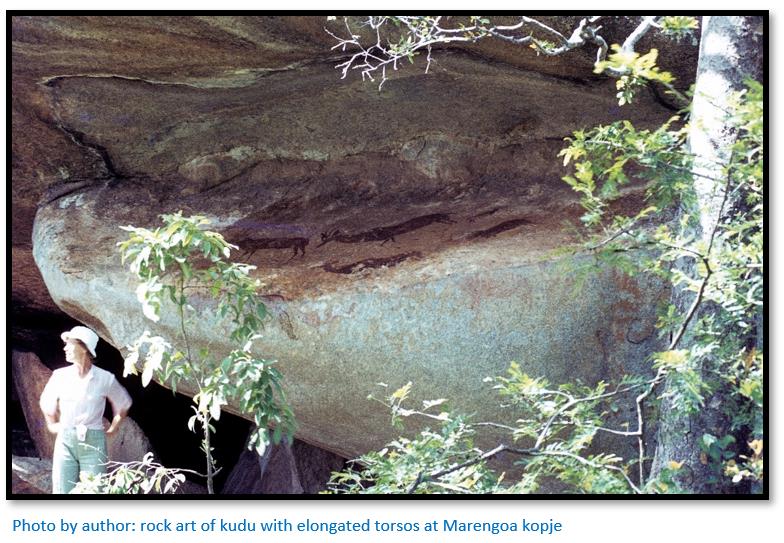

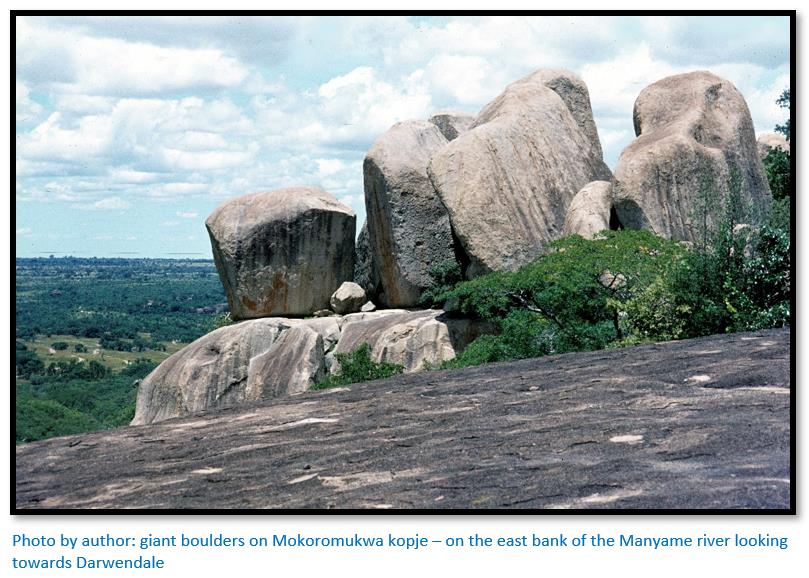

These nets, made of pliable bark rope, were six feet high and about one hundred yards long, carried about and set up on long sticks, about one inch in diameter. Sometimes the semicircle of net was as much as five hundred yards long, with natives armed with spears stationed behind the nets about twenty feet apart to kill any animal which ran into the net. Our body of natives would move off on a long detour, gradually working round towards the semicircle, lighting grass fires as they went and leaving guards at intervals to deal with the animals which might break back. Then the mobile body of natives would close on the semicircle of net, making as much noise as possible, driving the game to the waiting spearmen. This was the principle we wanted to use against the baboons, who had their headquarters on a small hill of huge granite boulders called by the natives ‘Marengoa’ - the hill of lions.

We set out from the homestead at 11pm, fifteen guns and three hundred natives, to be ready for the drive as the waning moon rose at 2am. At Marengoa we divided the party in two, one group going north and the other south. The nets were played out, the natives took their places and eventually the two horns of the company met on the far side of the hill as the shrill whistles of the signals sounded on the night air. As the moon topped the trees, its silver beams lit up the huge, mass of boulders, some as much as one hundred feet in diameter, and the uneasy baboons began chattering. I ordered fires to be lit against the chill dawn air and pots of coffee were soon cooking. As dawn came, one old man crept down and around the boulders and climbed the nets, leaping with a hoarse cry right amongst the squatting natives. There was one shot, but he got away. Pandemonium - baboons screaming, natives shouting, baboons rushing into the nets, dashing back up the hill, hiding between the huge boulders. When it was light, we decided to beat the kopje. There was a cave about fifty feet high and nearly one hundred feet long in which the baboons gathered, but as we beat the ground they scrambled out to take their chance at the nets.

When it was all over we counted thirty-five baboons dead and an unknown number wounded. After that hunt they gave us peace for a long time.

Money was scarce in those early, experimental days at Darwendale, so Rawson and Dimmock took to training oxen for work, finding a ready and profitable market for their spans in Salisbury. To save labour, they decided to switch to American methods and from the United States they ordered lassos, special saddles and stock whips. An American prospector, Yankee Jones, (who as a young man, had served under the famous General George Armstrong Custer of Indian fighting fame) taught them how to handle this novel gear and soon five or six horses were trained to the branding procedure. The ox would be roped by the fore and hind legs, two horses would take the strain of the ropes and tumble the ox, and the ‘cowboys’ would run in to brand the animal. But there was always a snag. Suddenly the horses got the mysterious horse sickness, for which there was no cure in those days and Rawson and Dimmock lost all their valuable mounts.

They tried a last fling – by trying to break bullocks to the saddle. And Rawson wrote: “They never seemed to get tame enough to ride easily and would suddenly break into buck jumping at the most critical times. When pushed, they would soon get blown. It was amusing, but not money making.

Then Rawson went north and Dimmock decided to try his hand at pig breeding, while waiting for the young cattle to grow to a saleable size. They started with a few sows and a boar and when Rawson returned the pigs totaled five hundred and the Salisbury market could not absorb the number which many farmers were producing. Pig handling was difficult. Fed on maize, the pigs were turned into the veld to graze and grub for roots, but they were difficult to round up and the native labour refused to herd them. Dimmock came to the rescue. He had hunted with the North Cheshire Hounds and from his kit he dug out a hunting horn. Morning and evening, as the pigs ate their ration maize, he blew that horn. When the pigs were in the veld, Dimmock would climb to the top of a kopje and sound the horn. Within a few minutes, from all points of the compass, hundreds of pigs would be galloping through the long grass to the homestead.

The partners decided to look for another market. They chose the Ayrshire Mine, fifty miles to the north-east. Fifty pigs were chosen. Twenty natives had the job of driving them. In the midday heat the pigs would not walk, one and all lying down. In the cool of the early morning the pigs wandered into the veld, the natives could not - or would not - find them and when Dimmock reached the mine after a twelve-day trek, twenty-five pigs had been lost. Even his great sense of humour could not stand such setbacks and he admitted that he could not have led the pigs, Pied-Piper style, with a hunting horn for fifty miles.

Another farming venture had failed.

During his travels Rawson, a keen amateur botanist, had collected about one hundred and twenty varieties of grasses, and these were sent to Kew. The reports, he noted with pride, showed that Africa, especially in the lowveld, was second to none in possessing the finest grasses in the world. But there was a persistence scourge - the great grass fires which swept the countryside every year.

“Time and again these were started by the natives in their belief that if the grass were not burnt, the rains would not come” wrote Rawson, “and if the rains were delayed, which often happened, nothing on Earth would stop the natives from burning the whole countryside.”

Nobody can recall certainty when the last elephant was shot in the Darwendale area, but in 1906 when O.C. returned from his East African trip, the population was put at two hundred. Carl Hagenbeck of Hamburg, wild animal collector, and the son of the man who planned the famous ‘natural’ zoo at Stellingen, sent an agent to Rawson to arrange for the capture of an elephant for training in Germany.

“When we told him that the number here did not exceed two hundred, he was no longer interested” Rawson noted. “He explained that it would take about five years to make and prepare the stockades and drives and they would require about five thousand natives to work with, when they would expect to collect one or two thousand elephants in a drive!” It would have been mind-shaking to work on the logistics of moving, say, two thousand elephant from Darwendale and the Umvukwes to Hamburg.

Rawson and Dimmock switched their thoughts from elephant to cattle improvement.

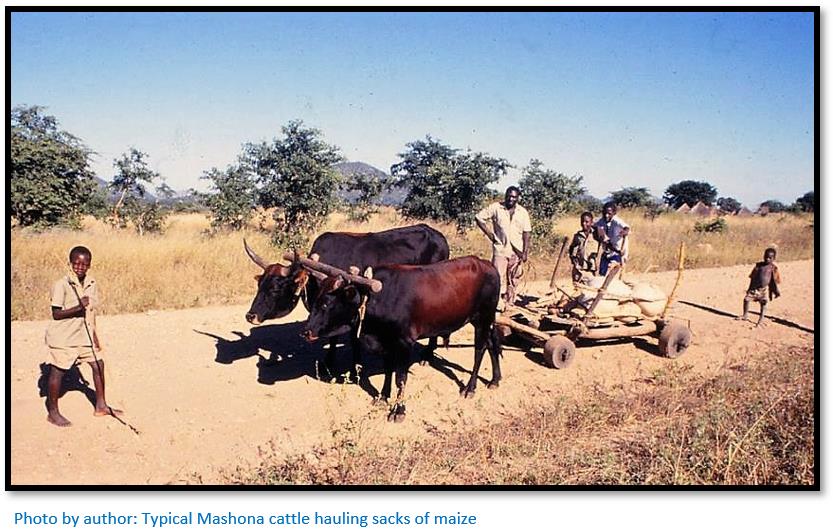

“Import good bulls,” said Dimmock and a Mr Williamson, a noted cattle judge in Scotland, sailed for home with an omnibus order from many farmers, which included six Coats Shorthorn and six Polled Angus for the Rawson ranch. The bulls duly arrived - and surveyed a domain carrying about two thousand head of cattle, mainly of the Zebu type then so prevalent in East Africa. Rawson noted: “This breed is very hard, docile and prolific and their confirmation of body is more akin to our home breeds, being fine in bone and low on the leg and carrying meat in the proper places. I have seen these small animals dressing 450 to 500 lbs. and so fat that water poured on their back would remain while they stood still. Looking back on that period, I cannot help feeling that we made great mistakes in rushing to the imported exotic breeds from England before the country and farms were ready to receive them.”

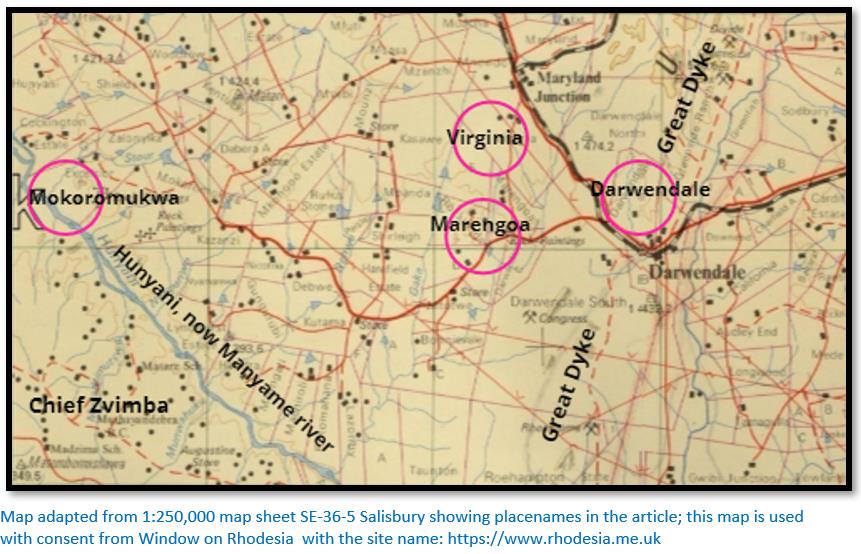

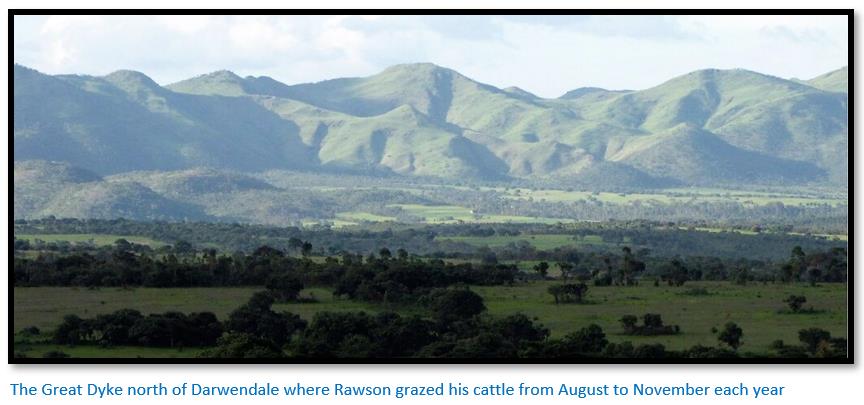

Rawson, complaining that the BSA Company’s policy of not allowing any land to be pegged in the ‘gold belt’ or where minerals were likely to be found - because of the many disputes between farmers and miner - was locking up some of the richest land in the country for many years, took his cattle during the winter months to graze north along the Umvukwes or south to the Hunyani (now Manyame) river.

“We used a stretch of land about one hundred and twenty miles long and about thirty miles wide,”[ii] he said. “We left the ranch about August and returned again with the opening rains, generally in November, with all our stock fat and many calves added to their numbers. We looked on this as our yearly holiday and moved from time to time to get new grazing where we could also be sure there would be plenty of game. This time of trekking with the cattle filled in part of the year in an easy and delightful way and although occasionally lions disturbed us we were fairly free from trouble on the whole. Living in such close contact with nature in all its aspects and sleeping on a grass bed under the heavens, covered with stars, deepens one’s sense of religion and makes one realize the vastness and mystery which surround us.”

Then the Duke of Westminster spoiled the idyll. From the railway station he sent a note. He had been, it said, on a hunting trip to Lomagundi with a special permit to shoot an elephant. Four miles from Darwendale he had wounded one badly. As he was leaving for England immediately, would Rawson follow it up! If he got it, would he keep every bone and the hide? Rawson got it after four or five days and the spoor of about sixty miles and the reconstructed elephant went on display in the Glasgow Museum as a memento of the Duke’s Rhodesian visit.

Came the time when a large bull elephant turned rogue and killed a native messenger. It chased the sole railway ganger, destroyed the gardens at a mission station and caught a second native who thought he could outrun the elephant along the track. He couldn't and the man said Rawson: “was literally pounded into the earth by the animal’s fury.” The farmers rose in uproar.

The government, without notice to the Darwendale inhabitants, threw open the shooting of what until then had been royal game. Rawson noted: “Our first intimation that this had happened was the arrival of a party of about twenty from Mafeking in Bechuanaland (present-day Botswana) with an equal number of horses and all their camping equipment at the station. We did not know what their business was until the slaughter started the next day. Very soon, about one hundred and twenty of the two hundred elephants that had roamed over our countryside had been slain and the rest had fled from the district to the Sanyati and the Zambesi Valley, two hundred miles away.”

The Darwendale farmers went up in steam. They had respected the law, not molested the elephant, and then, when they had called for some form of control, they had been by-passed and the elephant herds had been virtually destroyed by men from outside Rhodesia.

In his memoirs Marcel Mitton[iii] notes this occasion. He wrote: “In those days elephant roamed the Lomagundi area, causing so much havoc to maize growers, both European and African that hunters were invited to destroy the rogues. A party of Boers came up from South Africa in 1908 and slaughtered a good many. One of their party, Eloff by name, was killed in the middle of a herd by the ricochet of a bullet.”

Hagenbeck came back into the picture. An Australian and a South African sought permission to trap game on the flats which ran thirty miles east from Darwendale to Salisbury, planning eventually to ship them to Germany. Eland, sable and roan were plentiful. The country was good for horse riding, the game was ridden down until a selected buck could be cut out from the herd when it was blown, and in due course the captured animal would be put to graze in a special paddock with a small herd of cattle designed to calm it in captivity. The buck were given sweetened fodder and in a very short time were feeding contentedly with the cattle, the eland proving easier to handle than the sable. The Australian and the South African went their away with forty head of game for Hamburg and the two ranchers returned to their daily chores.

Rawson had one further brush with an elephant. He had stalked him and wounded a sable bull five miles from the homestead and then tracked the animal for another four miles before it finally collapsed. He sent his gun bearer back for the skinners, then decided to leave the hilly country he was in for the plains which he knew ran on either side of the rocky range. The day was cloudy, no sun showed and he was more than hungry, not having eaten since sunrise. It was dark when he reached the plains and then he found he had been walking north instead of south. He was twenty-five miles from Darwendale and the country was, he knew, well patrolled by lions and leopards. He pushed on hungry, tired. At about midnight he saw in front of him, a large granite boulder. He stood against it wearily - and the elephant’s trunk went up against the sky above him.

“I knew he might pick me up, as his trunk came down first one side and then the other, and I had just enough presence of mind not to fire. When the trunk came down my side for the second time and then stayed motionless, I quietly backed away with my rifle at the ready. The elephant went back to sleep and I backed cautiously for fifty yards, before scuttling towards Darwendale.”

Imagination thrives in the wild country.

One afternoon Rawson and Dimmock, having gone to their rooms for a short rest after lunch, were startled by a thunderclap: “which sounded like a heavy bore rifle discharge.” Both men shot out of their rooms with revolvers in their hand, ready for any emergency! A dry storm had come up suddenly, lightning struck the pole and dhaka house with its thatched roof, a metal lamp hanging over the dining table exploded, and the house blazed like a torch. Most personal possessions were saved, but the new home was destroyed. Rawson and Dimmock, however managed to laugh when they realized what had happened - for they both thought they were being attacked by two Australians who had visited them two days previously.

This brace of strangers from nowhere had wasted no time in proving how good they were at shooting, being able to hit a shilling on a tree trunk from twenty paces, shooting at great speed. They spent the night on the farm, then left at sunrise, moving across country. Three hours later, police troopers arrived, on the trail of the two Australians who were wanted for blowing open the safe at a gold mine and making off with the month’s output.

“They are desperate men,” said the policeman, “and you're lucky not to have suspected anything, or you would have had a rough house.” The policemen trailed the Australians in hot pursuit for four hundred miles before they could arrest them.

A short account of Otto Rawson’s life[iv]

Otto Christian Zimmerman (later named Rawson) arrived in Salisbury on the 15 July 1895 and took part in the Mazoe[v] and other patrols in 1896, decided three years later that there was no future for him here and was on his way out of Africa when he was called to meet Cecil Rhodes at Groote Schuur in 1899. The latter offered him six farms in Rhodesia if he would stay. Having said he would be quite satisfied with one farm; he was told that a telegram would be sent north ordering that this be granted to him. So, he went back to visit the Surveyor-General in Salisbury, where he was surprised to discover that there was a difficult condition attached to the offer: he had to put one thousand head of cattle on the farm within two years, fifteen hundred more in the third year, with further increases every year up to five years.

Though he knew cattle to be scarce he accepted and went to England to bring into the proposition, as partner, his friend, Cyril Ashton Dimmock. They started on Darwendale which was at first only one hundred and twenty acres but was later increased to three thousand acres. In 1901 East Coast fever killed off any cattle they had been able to acquire, but instead of giving up, the two partners starting in September that year, trekked up to the Fort Jameson area to buy cattle; they walked them back, swimming them over the Zambesi near Feira, by April 1902. Zimmerman made three further long trips for cattle on his own. The second started on 12 July 1902, the third on 15 August 1903 – both to Northern Rhodesia (present-day Zambia) and the fourth to German East Africa (present-day Tanzania) on 4 April 1904.

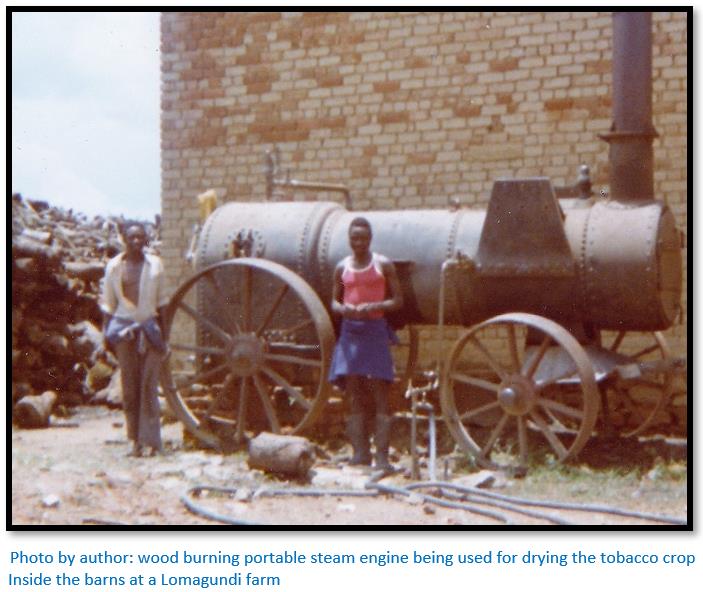

In about 1906 his partner Dimmock – who died in 1921 – took over Virginia Ranch near Maryland, and Zimmerman became sole owner of Darwendale. In 1913 Zimmerman changed his name to Rawson and was well-known to everyone in Lomagundi as O.C. Rawson or ‘Boss Jim’ until his death on 30 December 1953 at ‘The Homestead’ . He was an early enthusiast for Turkish-type tobacco and had a Turkish handling warehouse at Darwendale station in the 1930’s, which later became the headquarters of the Turkish Tobacco Co-operative.

The Ayrshire Gold Mine & Lomagundi Railway 2-foot gauge line

Much of the information below comes from Anthony Croxton’s article.

In 1892 George Pauling started construction of a 2-foot railway from Fontesvilla on the Pungwe river in Portuguese East Africa (present-day Mocambique) to Umtali (present-day Mutare) and after many difficulties climatic, health, constructional and mainly financial - the line was eventually completed by stages on 4 February 1898 and linked Beira with Umtali.

The 2-foot gauge proved inadequate for the growing traffic and in January 1898 a start was made with the Mashonaland Railway's line from Umtali to Salisbury to the standard ‘Cape’ 3 ft. 6 in. gauge. In late 1899 work began on converting the Beira Railway to the wider "Cape" gauge to be completed in July 1900 when deviations shortened the line from 357 to 328 km in length.

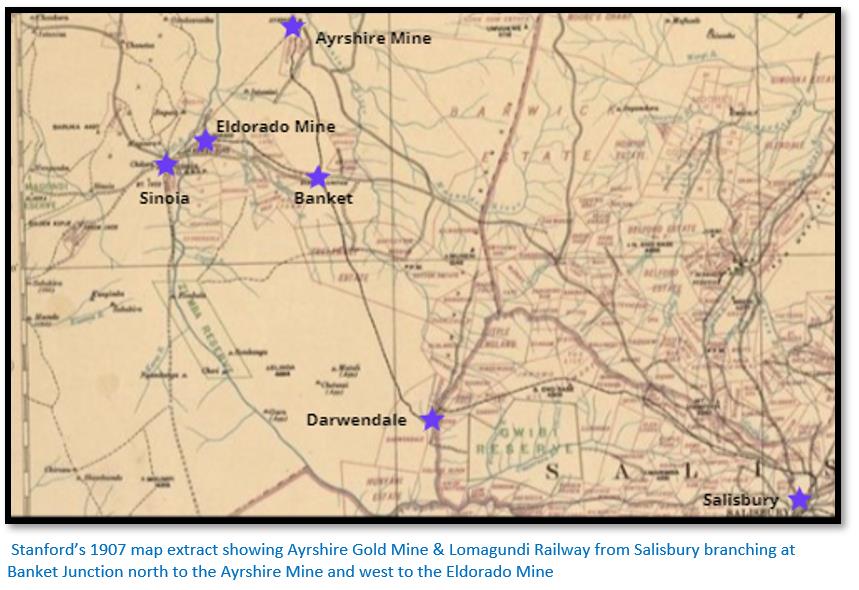

In 1902 the Mashonaland Railway in conjunction with the Ayrshire Gold Mining Co. built a 2 ft. gauge branch line from Salisbury to the Ayrshire Mine, 134 km long, and to operate this - the Lomagunda Railway - several of the Beira Railway 4-4-0’s[vi] were brought to Salisbury from Bamboo Creek and ran on the new line until 1913. As well as locomotives a number of open and covered goods wagons, one or two carriages and some guards' vans were also moved from the Beira Railway to the Ayrshire line.

A separate station for the narrow-gauge was built near the main line at Salisbury and a ‘mixed’ train ran three times a week to and from Ayrshire - the journey taking 8 hours out and 7½ hours back the next day. European passengers travelled in an ex-Beira Railway third- class carriage with hard seats and their backs to the windows - it was not unusual for sparks from the wood-burning engine to blow in causing much backslapping to put out smoldering clothes. At tea-time, the train stopped so that a fire could be lit at the lineside and a kettle boiled, while other stops occurred if the enginemen sighted a buck or some guineafowl within range of a shot from the rifle on the footplate.

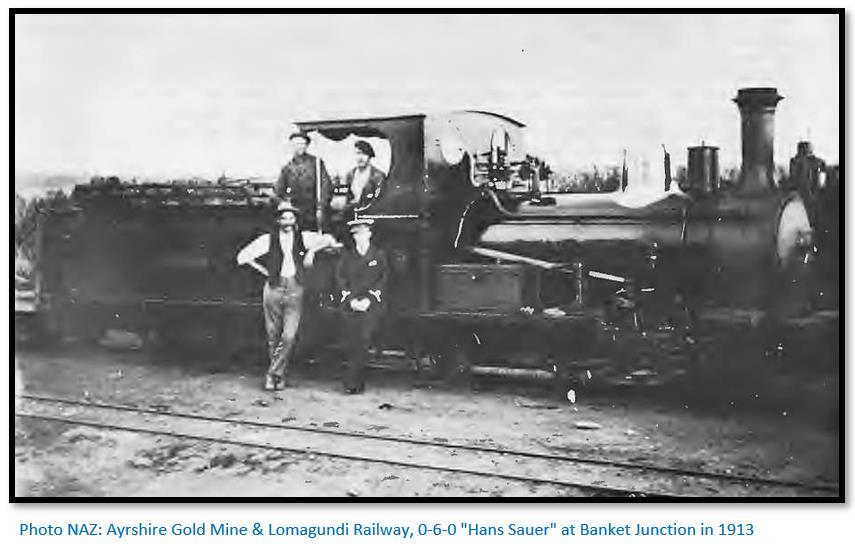

With the extension of the line west to the Eldorado Mine, the four Falcon 4-4-0’s could not cope with the traffic as the ore from this mine was carried for crushing at the Ayrshire plant, so an 0-6-0 side tank was ordered in 1905 from the Hunslet Engine Company which hauled 72 tons gross compared with 42 tons by the Falcons. The locomotive was named ‘Hans Sauer’ in honour of the chairman of the mining company, but soon after arrival it was decided to strip off the side tanks and attach a 6-wheel tender to which the nameplate was transferred.

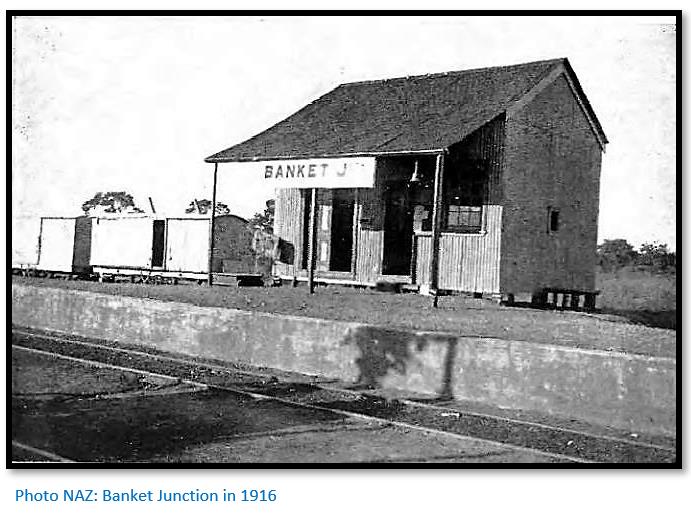

The ‘Hans Sauer’ locomotive proved very popular with its crews and ran over 148,000 km between mid-1905 and the end of 1912. When the Salisbury - Eldorado Mine line was extended and widened to 3 ft. 6 in. gauge in 1913, ‘Hans Sauer’ and a few wagons were left at Banket Junction until the short section of 2-ft. gauge to Ayrshire Mine was converted about 1916.

In later life the ‘Hans Sauer’ ran for many years on the Selukwe Peak Light Railway. Three of the Falcons 4-4-0’s went to the Cam & Motor Gold Mine which needed large quantities of firewood for their roasting plant and operated a light railway.

References

C. Black (Editor) The Legend of Lomagundi by North Western Development Association. Art Printopac, Salisbury, 1976

C.T.C. Taylor. Lomagundi. Rhodesiana Publication No 10, July 1964

A.H. Croxton. Narrow Gauge in Rhodesia. The Narrow gauge Railway Society Magazine No 43, February 1967

Notes

[i] Otto and his brother changed their names from Zimmerman to Rawson in 1913 presumably because of anti-German feeling at the time.

[ii] The Great Dyke extends north and south of Darwendale

[iii] Marcel Mitton features in a separate article in The Legends of Lomagundi booklet called The Frenchman who became a Rhodesian as a chef, miner and hunter. P54-56

[iv] Sourced from Major C.T.C. Taylor’s article Lomagundi in Rhodesiana Publication No 10, July 1964

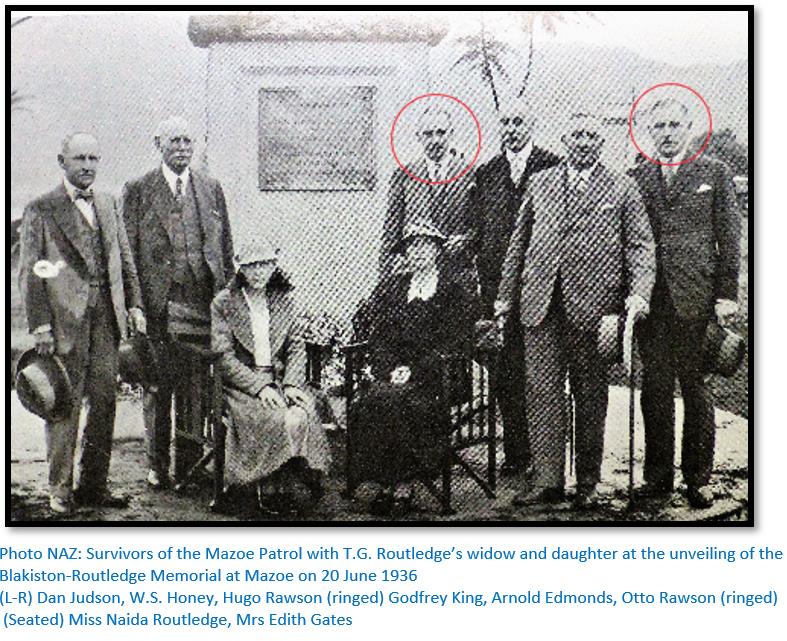

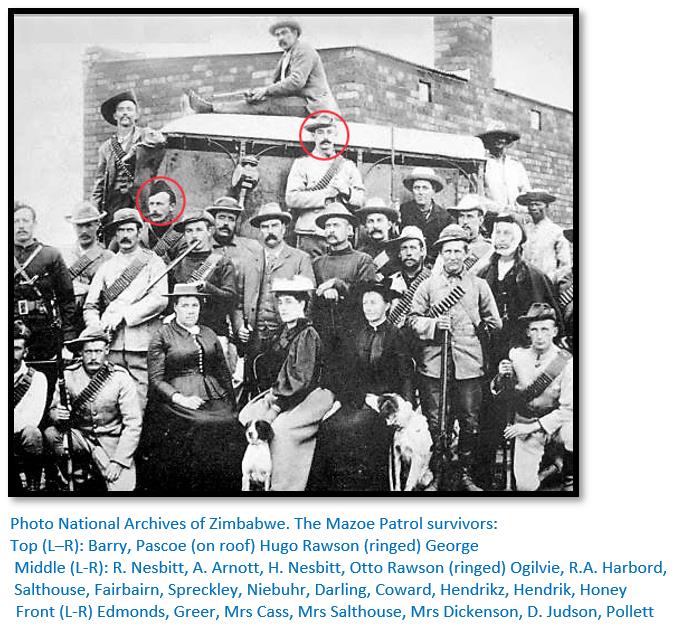

[v] Early in the morning of 18 June 1896, J.L. Blakiston of the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Line, H.D. Zimmerman (later named Otto Christian Rawson) who was then the owner of a general store in Salisbury (present-day Harare) and a ‘Cape Boy’ arrived with a wagonette sent by Judge Vintcent arrived at the Alice Mine to take the wives of Cass, Dickinson and Salthouse back to Salisbury. Captain Cass and James Dickinson went ahead to pick up papers and prepare food for the group’s arrival – apparently they thought that the presence of BSAC Police stationed at the Salvation Army farm made it safe. They party with the wagonette and wives left the Alice and five miles on when they heard shots John Pascoe ran ahead and saw Cass being clubbed to death with knobkerries. James Dickinson and William Faull were also killed. The party managed to turn the wagonette around and just managed to get back to the Alice ahead of their pursuers.

On the 19 June a second small patrol under Lieutenant Dan Judson arrived at the Alice Mine.

On the 20 June a third patrol of thirteen horsemen led by Police Inspector Randolph Nesbitt arrived from Salisbury and the entire party made their way back under fire.

Hugo Rawson (then Zimmerman) arrived at the Alice Mine on the 19 June 1896 with the first rescue patrol. Otto Rawson – the subject of this article – arrived with Nesbitt and the third patrol.

See the article The June 1896 Mazoe Patrol skirmish with detailed accounts from those besieged and their Mashona attackers under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

See also the article Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Co under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vi] Two types of 4-4-0 tender locos were built by the Falcon Engine and Car Works, a section of Brush Electrical Engineering Co., Loughborough. The later type supplied from about 1896 had a larger boiler and longer smokebox while the chimney was straight with a lipped top; a 6-wheel tender held 780 gals. of water compared with the 500 gals. of the 4-wheel tender, while the wood fuel capacity was also larger. In 1900 when the Beira Railway was widened in gauge all the Falcon 4-4-0’s were stored at a station in Mozambique called Bamboo Creek.