Maramuca, a Portuguese Feira dating from 1660 - 1680

- The Portuguese were not the first traders and explorers to enter Zimbabwe, as prior to their arrival on the east coast of Africa the Arabs, Indian and Swahili merchants had traded in the interior with local people. The Arab-Swahili merchants adopted Islam and moved south from Kilwa from about 900AD establishing trading settlements where they traded for gold and ivory at Angoche, (now in Nampula Province in Mozambique) Quelimane (north of the Zambezi River mouth) and Sofala (on the Buzi River, south of Sofala) and in the interior.

- Initially after their 1498 arrival the Portuguese cooperated with the Arab-Swahili merchants, but gradually they planned to take-over the entire trade and force out any rivals through their sea power and by dominating the seaports. In response the Arab-Swahili traders opened up new routes into the interior in rivalry and little gold reached the Portuguese who were forced to undertake trading expeditions into the interior themselves. They built inland settlements along the Zambezi River at Sena and Tete initially, but found that to increase their trade in gold and ivory they needed to establish permanent trading posts deep in the interior where a few Portuguese settled with their vashambadzi, offspring from local marriages. Amongst these were Dambarare, Massapa, Luanze (Ruhanje) Manyika, Bocuto, Piringani, Angwa (Ongoe) and Maramuca. Most of these appear to have been well established by the 1580’s, although Maramuca was probably only occupied for a short period between 1660-1680 and at the end of the Portuguese presence in Mashonaland.

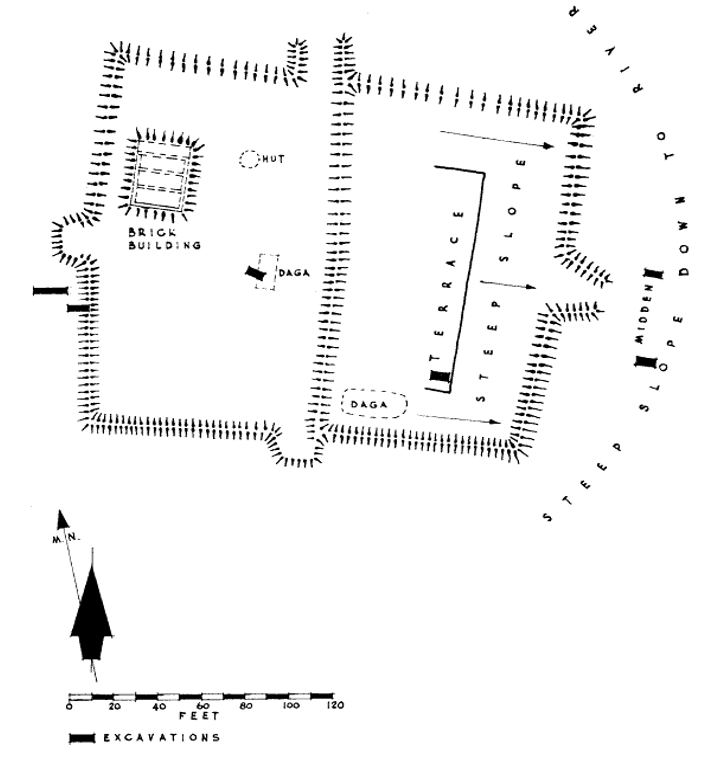

- Peter Garlake’s excavations of Maramuca near Chikari in 1965 revealed that it was very similar to the feira at Luanze near Mutoko which had a sun dried brick building surrounded by a earth bank and ditch. Unlike Luanze however, Maramuca’s wall had a brick core and there was no ditch and the enclosure was much smaller. The Maramuca brick building was built onto an artificial stone platform and divided into three long narrow rooms, each 2.1 metres wide and 4.9 metres long.

- Neither Maramuca nor Luanze were built with strong defence in mind; they were primarily places for storing and selling goods and to provide shelter. This was confirmed by archaeological finds following an excavation done by Peter Garlake which included European and Chinese imported ceramics, glass and gold beads, musket balls and gold dust. Luanze is described on the website www.zimfieldguide.com under Mashonaland East.

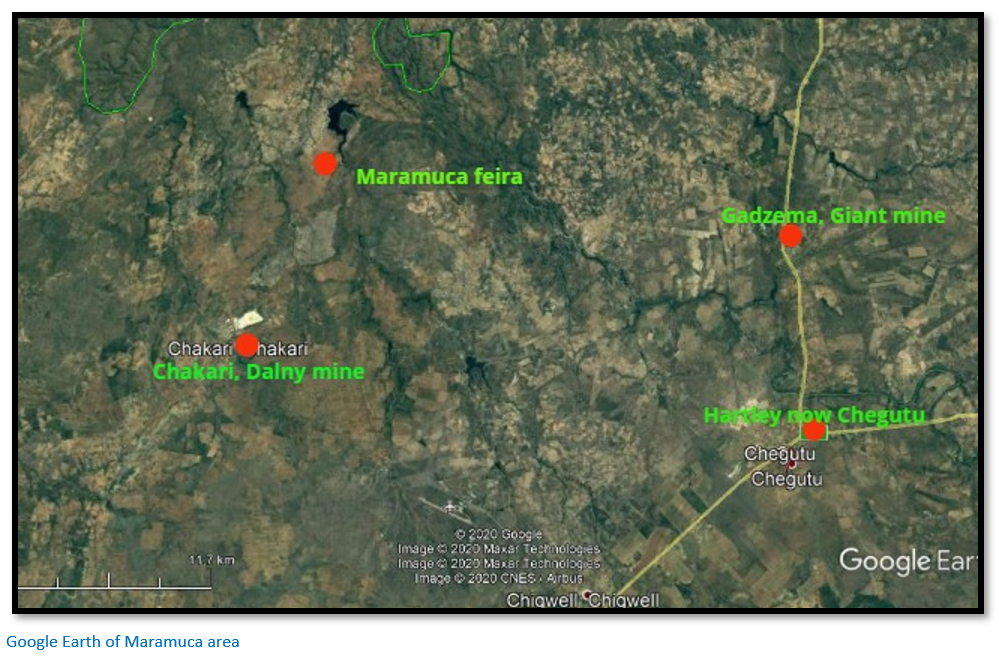

- The Maramuca site is on the eastern edge of the lower Mupfure gold belt and the kopje on which the earthwork is built and another kopje 90 metres to the north is pitted with shallow “ancient gold workings.”

Take the A5 from Harare to Chegutu. Turn right on entering the town for Chegutu (the Seigneury Road goes left) 0.5 KM turn left, 29.4 KM reach junction and turn right, 33.2 KM turn right onto untarred road in front of the Dalny Mine dumps at Chikari. 35.2 KM turn left, 42.2 KM continue straight on, 43.3 KM turn off the main road onto a farm track, 44.7 KM park. Maramuca site should be 250 metres due east, with the Suri Suri River a further 150 metres east.

GPS Reference: 17⁰59′58.02″S 29⁰54′51.61″E

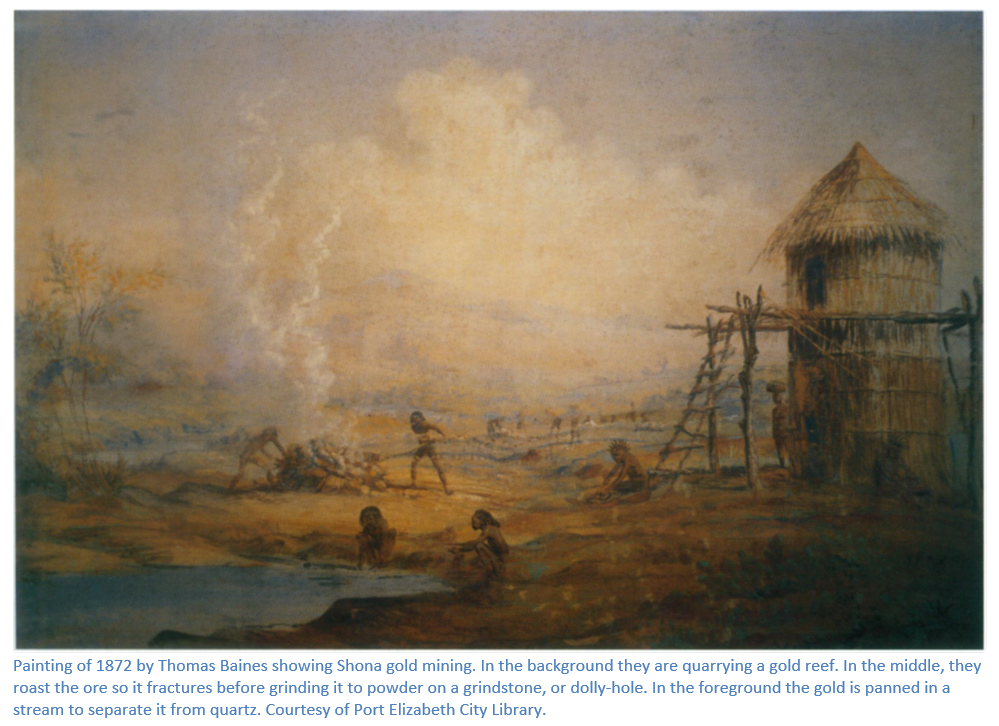

There a number of direct and indirect nineteenth century references to the feira at Maramuca. In 1867 Thomas Baines was told by Shona informants that the ruins of a Portuguese house were still visible, although he did not visit the actual site. Another reference is from William Harvey “Curio” Brown who set off on November 16th 1890 for Guidzema (now Gadzema, a siding on the railway line) about 35 kms from Hartley Hills taking Krohn, a prospector for the firm of Johnson, Heany and Borrow. They found the area had been heavily turned over by the “ancients” looking for gold and the quartz reefs had been worked to the depth of the water table, about fifty or sixty feet (up to 18 metres) and they found many grinding stones, or dolly holes, their upper surfaces worn away where the miners had crushed the quartz preparatory to panning it. Also, they saw the remains of two houses built of adobe bricks, 12 metres long (40 feet) by 6 metres (20 feet wide) that Brown speculated might have been a Portuguese Jesuit mission station, or the home of a Portuguese trader, who had lived there fifty or one hundred years before, buying gold from native miners. In truth, the Portuguese had been in Zimbabwe from 1560 and left by 1693, nearly two hundred years before.

There is gold at both Chikari and Gadzema; in Roger Summers’ Ancient Mining in Rhodesia Chakari is Area 29 which has estimated pre-colonial mining production at the Bay Horse Mine and Dalny Mine of > 10,000 oz. or 310 kgs and the Turkois Mine of > 50,000 oz. or 1,550 kgs. Gadzema is Area 30 with pre-colonial mining production at the Butterfly Mine, Lone Star Mine and New Found Out Mine each of > 10,000 oz. or 310 kgs and the Giant Mine > 300,000 oz. or 9,330 kgs. However, although Brown says he set off for Gadzema (he spells it Guidzema) he actually may have gone to modern day Chakari, 30 kilometres west and the site of the Dalny Gold Mine, also one of Zimbabwe’s largest gold producers. The reference to the Portuguese Jesuit mission station is probably the best clue as Maramuca is north east of Chakari and just 8 kilometres west of the Mupfure River. It seems much more likely that Brown actually went in the direction of Chakari following the Mupfure from Hartley Hill and Guidzema was just a general name for the area. Chakari only became a village in 1907 around the Turkois Mine after which it was named, and then it became Shagari in 1911 and Chakari in 1923.

Until the Portuguese forced the Mutapa Mavura to sign a treaty in 1629 the Mutapa controlled all the gold mines and the Portuguese only had jurisdiction within their feiras, and were not able to travel or trade as they liked and had to pay taxes and tribute (curva) to the Monomotapa State. After the treaty date they travelled at will, recruited labour and mined for gold as they choose. However, their meddling in the affairs of the state alienated the chiefs and spirit mediums “mhondoros” and in November 1693 the Rozvi under Changamire Dombo destroyed Dambarare in a surprise attack and forced the Portuguese at the Angwa River feiras to retreat north back to their bases at Tete and Sena.

Peter Garlake in his defining article Seventeenth Century Portuguese earthworks in Rhodesia says that his attention was drawn to an unsigned 1947 report in the Mining Commissioners office in Kadoma (previously Gatooma) referring to a “Portuguese Fort marked on an old blueprint” and a low quartz wall retaining a terrace near the Suri Suri River. Garlake visited and excavated the Maramuca site in July 1965 and found to an earthwork very similar to that of the Luanze feira. The site is on the summit of a small kopje on the west bank of the Suri Suri River fifteen kilometres above its confluence with the Mupfure River, opposite one of the permanent pools and on the eastern edge of the Lower Mupfure gold belt. The kopje on which the earthwork is sited is quartz rubble and a similar kopje 90 metres to the north is covered with shallow ancient workings.

Stan Mudenge suggests that the gold trade was carried out either:

- From Sena where Portuguese traders and / or their offspring from local women called vashambadzi either carried their trade goods of beads and cloth overland through Barwe to Manyika, or to the feiras of Mukaranga or,

- Sailed up the Zambezi River to Tete from where they went overland to the feiras of Mukaranga where they traded their cloth and glass beads and manufactured iron products to barter with the local people.

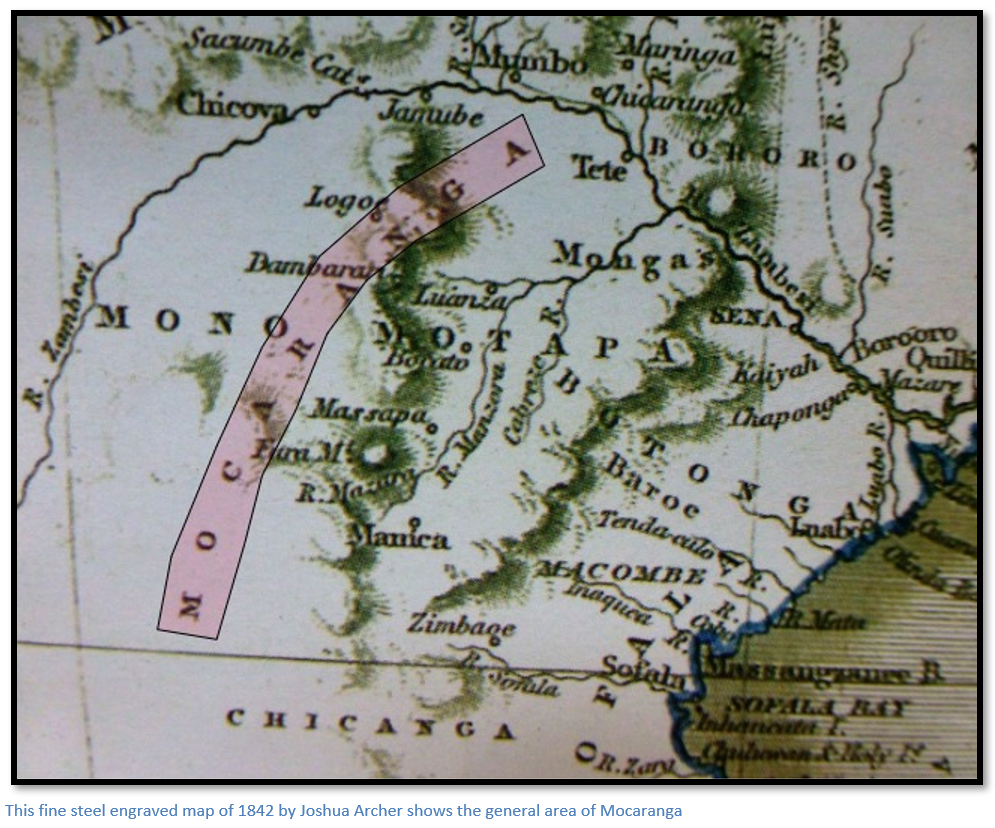

In Mocaranga (northern Mashonaland) in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the feira of Masapa was the most important; but later in the second half of the seventeenth century the feira of Dambarare became dominant until the Portuguese were forced from Mashonaland and established a feira at Massi Kessi in Manyika for gold trading. Indian cloth, blue and white beads, Indian tin and pewter wares were popular imported trade items as well as muskets.

A Portuguese trader Gonçalo João obtained the rights to open a trading station, or feira at Maramuka from the Mutapa Kamharapasu Mukombwe, but at the same time the Mutapa gave monopoly rights to trade in the area to Antόnio Roiz de Lima and a mulatto priest, Fr. Simão Gomes, both very rich traders at Sena. Gonçalo João started trading at Maramuka from 1660–1680. In response to him trading within their monopoly area, Antόnio Roiz de Lima and Fr. Simão Gomes began to encourage the local chiefs around Maramuka to rise up against Gonçalo João by sending them arms and men. Joao was unprepared for this assault and because he had no defences, his feira was attacked and pillaged around 1680.

Roger Summers in Ancient Mining in Rhodesia states this carved ivory statuette of the Immaculate Conception was found at depth in an ancient working of the Bay Horse Mine in the 1930’s. It was given to the miner’s children to play with and rescued by Capt. RHR Stephenson who gave it to the Bulawayo Natural History Museum. The British Museum reported that it is a Portuguese colonial work of the seventeenth or eighteenth century, probably Goanese. Abraham was the first to suggest that the statue may have been the property of a Portuguese trader living at the Maramuca feira just nine kilometres away.

Abraham used Portuguese records and local oral traditions to suggest this is the area of Maramuca and Manoel Barretto in 1667 described it as follows: “Maramuca is the name of a great district of the Kingdom of upper Mocaranga…this kingdom is the richest in gold known.“

Mocaranga refers to the broad area of Mashonaland; Rimuka referred roughly to the much smaller area between the Mupfure and Umsweswe rivers. The above 1824 map by Joshua Archer continues to show Mocaranga diagonally across the area south of the Zambezi River and the Portuguese feiras of Dambarare, Luanze and Bocuto even though they had all been sacked and destroyed by the powerful Rozwi warlord Changamire Dombo in 1693 at the instigation of the then Monomotapa Mutapa Nyameande Mhande. Although mapmaking techniques had changed greatly between the above dates; later cartographers continued to borrow a great deal of misleading information from earlier mapmakers.

Maramuca as a feira appears to have been much smaller trading post than those named above which each comprised several Portuguese families operating under the overall command of an elected Capitão with servants and followers, or their offspring from local women called vashambadzi, possibly just a single trader occupied the Maramuca site.

The Maramuca feira site closely resembles the earthwork at Luanze feira with straight banks enclosing a rectangle facing north which is 67 metres wide (220 feet) and 55 metres long (180 feet) with bastions 6 metres wide (20 feet) and projecting 4.5 metres (15 feet) from the centre of each wall. A wall runs down the middle of the site with a retaining wall made of massive quartz boulders on the east side to provide a flat artificial terrace before falling away to a steep slope.

On the western side of the rectangle is a rectangular brick building, whose southern wall at the time of Garlake’s 1965 excavation was still partly above ground. This building was 6 metres wide (20 feet) and 8.2 metres long (27 feet) and divided into three long narrow rooms with a raised internal floor; most of this is obscured unfortunately by a large termite mound.

The walls were built of sun dried brick, probably using ant heap material. An excavation trench outside the western wall revealed there was no ditch, but that the wall contained brickwork. The steep eastern slope revealed scattered stick dhaka, probably from huts destroyed on the terrace.

The only imported wares excavated were scattered parts of a seventeenth century brown and black glazed storage jar; similar jars were commonly found in the seventeenth century levels of the Portuguese built and occupied site at Fort Jesus, and scattered shards of imported Chinese blue and white glazed wares. Fort Jesus was built between 1593 – 1596 by order of King Philip I of Portugal, to guard the Old Port of Mombasa. A few pieces of local pottery were found identical to those at Luanze and some imported red and white glass beads and cylinders identical to those found at Luanze and Dambarare feiras and other glass fragments.

In conclusion, Peter Garlake states the basic architecture of the Maramuca feira had a military basis featuring bastions; but that the long perimeters and low banks were never practical for defensive purposes and the enclosures were intended for secure bulk storage as warehouses and built for trading as indicated by the finds of beads, wire and ceramics. Maramuca was situated for convenience within the gold field; but the absence of many archaeological finds tends to suggest a short period of occupation of about 20 years.

Further to the west around the goldfields of modern day Kadoma and Kwekwe was Abutua, or Butua, first reported by the Portuguese degredado Antonio Fernandes, whose accounts of his travels reached Portugal in 1516 and earned him recognition and great esteem as an explorer.

The Rozvi forbid foreigner travellers into the interior after the destruction of the Portuguese feiras in 1693 and this situation lasted until the 1830’s Mfecane when Zwangendaba destroyed the Rozvi state. The entire interior saw great migrations of people and confusion and hardship. By the time European explorers and hunters such as Karl Mauch and Henry Hartley entered Mashonaland in the 1860’s and 1870’s overall control was in the hands of the amaNdebele who sent annual raising parties into Mashonaland to exact tribute in the form of women and children and cattle.

Archaeological site of Maramuca has been destroyed

The former site has been overrun by Makorokoza or small-scale miners who have been forced by the wretched state of the economy to mine in the former gold mines of the area; others have resorted to panning. There are reports that numerous miners have been trapped and killed after undermining the support pillars in the stopes of Dalny and Giant mines resulting in the roofs caving in and collapsing. Others are panning the local rivers and known former gold-mining areas such as Maramuca in search of gold. Extreme risks are taken by miners to earn a living and as a means of survival in an economy that is barely ticking over due to mismanagement and corruption and where formal jobs are scarce.

Acknowledgements

D.P. Abraham. Maramuca: an exercise in the combined use of Portuguese records and oral tradition. Journal of African History 11, 2

W.H. Brown. On the South African Frontier. Books of Rhodesia 1970

C. Dunbar. Article on a visit to Maramuca on www.colonialvoyage.com

P.S. Garlake. Seventeenth Century Portuguese Earthworks in Rhodesia. The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol. 21, No. 84 (Jan., 1967), pp. 157-170

Col. A.S. Hickman. Norton District in the Mashona rebellion. Rhodesiana No. 3. 1958

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of the Munhumutapa c.1400-1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1988

H. Sauer. Ex Africa. Books of Rhodesia 1973

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia 1969