The Hunter’s Road - followed on maps

To those unfamiliar with the term ‘the Hunter’s Road’ a brief explanation for an expression which is often used in historical articles but rarely explained. Today’s railways require easy gradients and often follow the watersheds that were in times past were frequented by travellers using carts or ox-wagons, on foot or on horseback. These trails had often started as old elephant paths or native trails and in the sandy regions they were broad tracks across the veld as travellers followed the wheel ruts left by previous trekkers.

All traveller’s going into and out of Matabeleland between 1864 – 1890 were forced to use The Hunter’s Road except trusted individual’s given permission to use a different route. All visitors were forced to wait at Makobi’s kraal, later at Umvolulu until the King gave his permission; “given the road.” The King required a gift for trading, hunting or travelling in his territory; it could be a salted horse, musket, ammunition, pistols, furniture, a uniform – anything that was valuable, useful or pleasing. The gift paid for one season only, but it usually brought freedom from competition as hunting parties were assigned an area.

Certain agreements were renewed over several hunting seasons; hunters were given familiar guides and allotted the same hunting areas until the wildlife was exhausted. Lobengula wished his own hunters to acquire as much ivory as possible, but still wanted the hunters gifts and raised the price above what Mzilikazi received – George Wood gave a salted horse worth £100 in 1870. The guides such as Inyoka described were spies for the King; to control the amaNdebele servants, to see they did not trespass outside their assigned hunting areas, prospect actively for gold, kill animals that were protected such as crocodiles,[i] sell firearms to the Mashona, but also had orders to also look after them. Frank Oates’ guide selected healthy sleeping spots for him which were relatively malaria-free.[ii]

For the reasons explained below, the Hunter’s Road became the safest and most direct route into Matabeleland and Mashonaland – it became a well-travelled path marked out by wagon wheel tracks and familiar to all the native guides and wagon-drivers who trekked the route. The 1896 Stanford map refers to the ‘Hartley Hill Road’ as do some earlier travellers.

Travelling into the far interior before 1871

Potential travellers glancing at a map might be forgiven for thinking that any of the three rivers flowing east from Zimbabwe into the Indian Ocean; the Limpopo, Save (or Sabi) and the Zambezi rivers might have provided a navigable waterway into the interior of what was called Zambesia in the nineteenth century. However, the Limpopo and Save are navigable only for short distances from the coast and both have sandbars which prevent all but the smallest boats from crossing except at high tide. Similarly the Zambezi river has a sandbar at its delta, but it is navigable for 650 kms to shallow craft although river levels are low during the dry season. During his expedition of 1858 – 59 David Livingstone discovered that the Zambezi river was navigable only as far as the Kebrabassa [Cahora Bassa] rapids. [See the article Thomas Baines’ disastrous 1858-59 Zambezi Expedition with David Livingstone under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Even if the Zambezi river had proved navigable the Portuguese would probably have hampered any future trade for political and economic reasons.

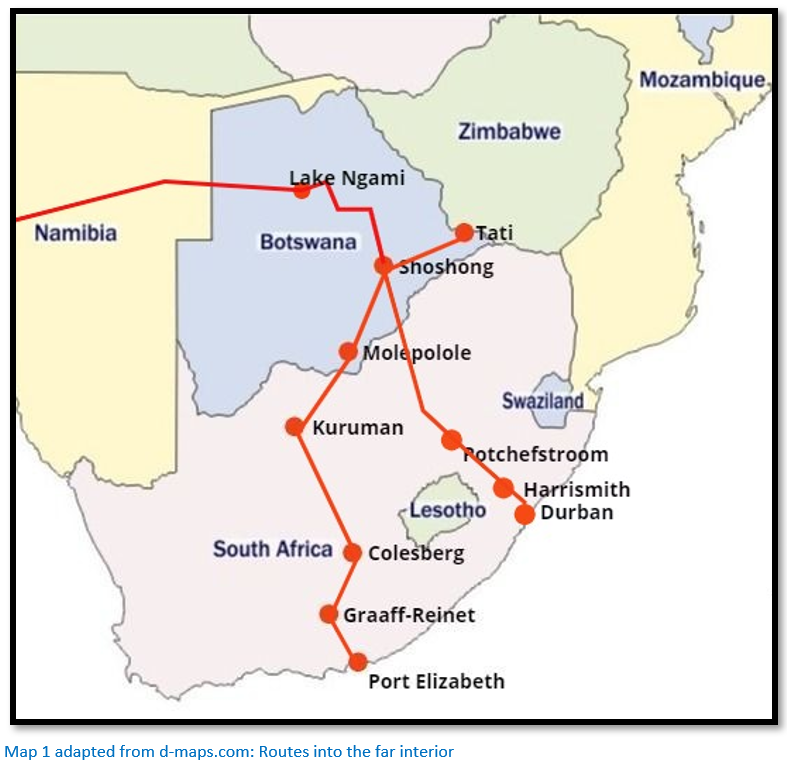

The only route then available was from the south. Two alternative routes were available for travellers into the interior by ox-wagon from the south and led from either Port Elizabeth or from Durban; both converged at Shoshong, the entrepôt for trade with the interior and a place of considerable importance to early explorers and traders in south-central Africa. The ox-wagons carried into the interior trade goods and supplies for the hunters, traders, prospectors and missionaries with the return cargoes consisting of ostrich feathers, ivory, hides, riems and a little gold.

Port Elizabeth in the Cape Colony was the earliest route; the journey to Shoshong being about 1,460 kms (907 miles) The route was through Graaff-Reinet and Colesberg and across the Orange and Vaal rivers to Kuruman, the mission station founded by Robert Moffat of the London Missionary Society in 1821. From there the celebrated missionary road ran north passing through Sechele’s town, Molepolole – beyond water was scarce and the route ran through deep sands which made heavy going for the oxen – in all, this route took about two months to travel to Shoshong.

The later alternative route ran from Durban – it was shorter with the distance to Shoshong being about 1,180 kms (735 miles) and took between five to six weeks of constant trekking.[iii] Once the Boers overcame their resistance to penetration of the interior by the British this became the preferred route. Climbing the Van Reenen’s Pass was a major obstacle and the oxen needed to recover before reaching Harrismith in the Free State, a town named after Sir Harry Smith a nineteenth century British Governor and High Commissioner of the Cape Colony. Food in Natal was obtainable at farmhouses and inns, but in the Free State there were fewer inhabitants and firewood was scarce. Some Boer farmers might refer to the British sportsmen and amateur naturalists passing through as verdoemde Engelseman and blomsoekers (flower hunters) whilst others were hospitable and friendly. From Potchefstroom, travellers had choices; travel to Rustenburg and then on to the Limpopo river, or to Zeerust and follow the Marico or Notwani rivers to the Limpopo – both routes then went to Shoshong through sandy wastes with little water.

Another route began at Walvis Bay to Damaraland crossing the Kalahari desert to Lake Ngami and then skirted south of the Makgadikgadi salt pans before travelling down to Shoshong; a distance of 2,090 kms (1,300 miles) although this route was longer, drier and more dangerous than those routes from Port Elizabeth and Durban.[iv]

Travel to the far interior from 1871

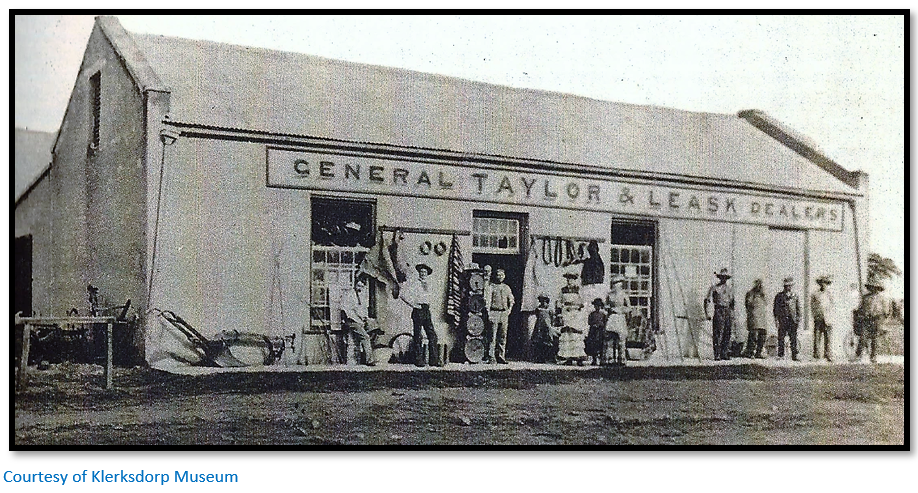

Klerksdorp gradually replaced Kuruman and rivalled Potchefstroom as a base for travel from 1871 for two reasons; first, it was fifty kilometres nearer to the diamond fields and secondly, in 1865 James Taylor opened a store at Klerksdorp which Thomas Leask later joined as a partner;[v] here hunters and traders, especially British ones, were made welcome.

Klerksdorp, Rustenburg, Zeerust, Potchefstroom and Shoshong served as bases to outfit travellers on their inward journey and for hunters and traders to sell their produce on their return from the far interior; here servants might be recruited and teams of oxen purchased. After what might have been an arduous and dangerous journey of perhaps two years in the interior most old hands went on a prolonged drinking session at Klerksdorp to celebrate their safe return. In 1873 Klerksdorp which was located on the Schoon spruit consisted of one street of twenty-five houses each of which had a garden, orchard and separating hedges. Potchefstroom was far larger with a population of four thousand including a landdrost (magistrate) and Portuguese consul. The white-washed houses had flat roofs or Cape gables that were surrounded by gardens, orchards and flower beds. Tree-lined streets crossed at right angles to form squares, the largest of which was the market-place and there were several schools and churches. Grain, meal, meat and tobacco were sent to the diamond fields; products from the interior included ostrich feathers, hides and ivory that were sent to Durban.

Shoshong

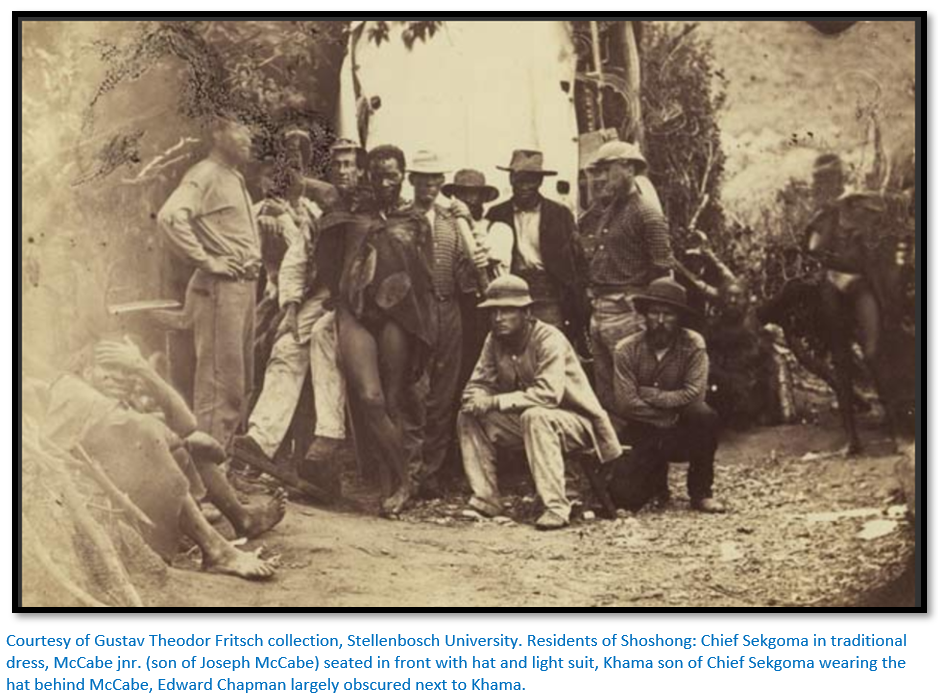

In 1874 Shoshong was the largest native town between the Drakensberg mountains and the Zambezi river with about 30,000 inhabitants and was the capital of the Bamangwato people (more correctly BagammaNgwato, also BaNgwato) The town was partially surrounded by the high and rocky Mangwato Hills rising from 215 – 245 metres (700 – 800 feet) above the surrounding plain which had given the town’s inhabitants access to strong defensive positions when attacked by Boers or amaNdebele. The town was located at the southern end of a valley which narrowed towards its northern end into a pass just fifty metres wide where a small stream, the Shoshon, flowed through the hills as an intermittent tributary of the Limpopo river.

Shoshong was initially a station of the Hermannsburg Lutheran Missionary Society, but in 1862 the London Missionary Society (LMS) became firmly established and the Scottish missionary John Mackenzie (1835–99), who lived at Shoshong from 1862–76, "believed that the Ngwato and other African peoples with whom he worked were threatened by Boer freebooters encroaching on their territory from the south", and campaigned "for the establishment of what became the Bechuanaland Protectorate, to be ruled directly from Britain."[vi]

The mission station was sited at the narrow northern end of the pass near the water supply and by 1879 the LMS missionary James Hepburn and his wife had built a compact settlement comprising of a brick house with corrugated iron roof, a church and school and some huts.

The large profits to be earned from the ivory trade induced several traders to settle permanently in Shoshong but like the missionaries they built a short distance outside the town and formed a small community of self-contained stores and brick houses. William Francis and Richard Clarke were established at Shoshong just after Khama became Chief in 1872; other prominent traders included Edward Chapman and James Cruickshank. [See the article on the Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate of concession seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

By 1878 there were nine trading stores in Shoshong and the Europeans comprised twenty-three men, six women and thirteen children, usually taking cattle, sheep and goats in exchange for their wares, but the commodity that really counted was ivory and ostrich feathers and Shoshong was where these commodities were traded. The country at the time was called ‘Khama’s country’ and the Chobe region supplied the bulk of the ivory.[vii] Khama needed to trade in ivory because he was badly in need of firearms to deal with the threats posed by the amaNdebele and the Boers.

The ivory trade grew and like his father Chief Sekgoma I Khama retained complete control over the ivory trade and ensured all ox-wagons came through Shoshong. In 1878 around 75 tons of ivory (68,000 kgs) from thousands of killed elephants were exported through Shoshong. In the following year the ivory trade was estimated to be worth £30,000. This wealth resulted in Shoshong becoming the largest and most wealthy town defended by Khama’s army of 3,000 men.[viii]

However in time the elephant retreated into the most remote areas and became harder to hunt and the old ivory trade declined in importance. Alfred Musson, a Shoshong trader, commented in the 1870s that: “The old trade in ivory, feathers and pelts, in exchange for beads and brass wire, was declining. Instead in accordance with their changing tastes and demands, we stocked roughly-made clothing such as shirts, trousers, guns and ammunition, ploughs and their spare parts (the plough trade soon developed into one of considerable importance) and assorted groceries.”[ix]

In the dry season all the water had to be brought by the women from a fountain in the gorge behind the town – the lack of water was Shoshong’s greatest disadvantage.

Tabler states that under Chief Macheng Shoshong was the haunt of all sorts of adventurers including: “white riffraff, renegade Matabele, vagabond Makalanga and Bechuana and Matabele spies; natives and traders cheated and abused each other and caroused indiscriminately.”[x] This all changed once Chief Khama was established as the tribal leader.

The rise of Khama III (1837 - 1923)

Young Khama was well-travelled and spoke Afrikaans, the common language between native speakers whose languages were different. In his early twenties he was baptised into the Lutheran Church but his beliefs brought him into conflict with his father Chief Sekgoma I that ultimately resulted in a botched assassination attempt and the installation of Sekgoma’s brother Macheng as the new chief of the tribe after Sekgoma left into exile.

Soon Macheng and Khama clashed leading to another botched assassination attempt before Khama overthrew Macheng and was appointed Chief of the Bamangwato in 1875. Khama banned alcohol from his territories and sought the protection of the British from the combined incursions of the amaNdebele in the east, German colonists from the west and Boer trekkers from the south who all hoped to seize his territories. In 1885 the British government declared the territory south of the Molopo river to be the colony of British Bechuanaland, whilst territory to the north of the river became the Bechuanaland Protectorate.

The capital moves from Shoshong to Palapye

The establishment of a British Protectorate gave the Bamangwato people greater security and Chief Khama III moved his capital from Shoshong to Palapye 60 miles (95 kms) to the north-east where the water supply was better. Later the capital moved to Serowe to the north-west of Palapye. From 1874 to 1884 the population at Shoshong fell to one-tenth of its peak of 30,000.

The roads to the north of Shoshong

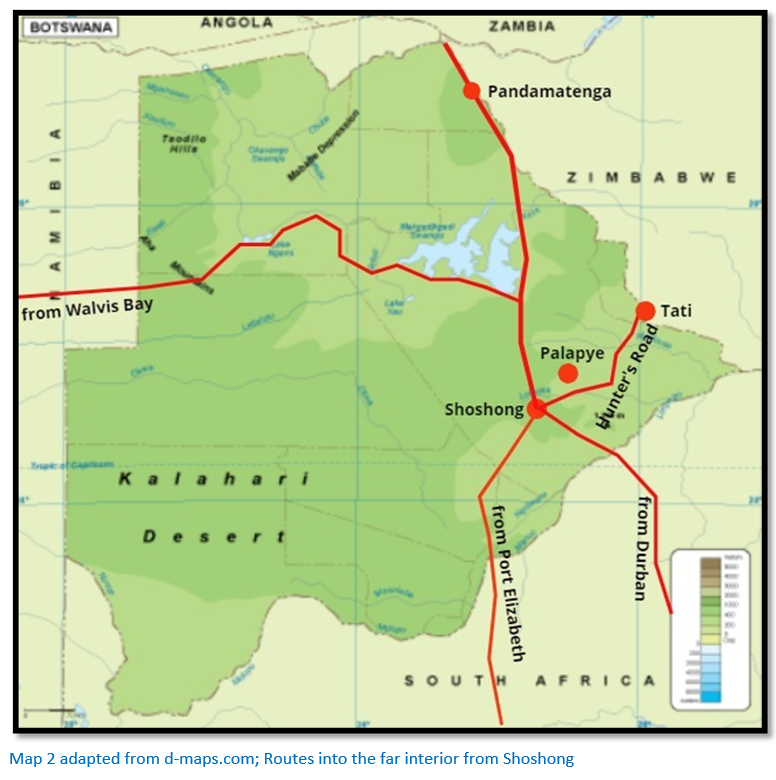

Two routes led north from Shoshong; one led to Lake Ngami, the other to the Zambesi river via Pandamatenga, now Mpandamatenga, which had been established by the trader George Westbeech in 1871. The name means: “the tree from where trade is done” but crucially the trading settlement was just outside the tsetse-fly belt, that region so fatal to domestic animals.

The road from Shoshong split at Tlabala Wells, the Lake Ngami road following the Botletle river to the lake and then going west for over 1,100 kms to Walvis Bay across the semi-arid sandy savannah of the Kalahari. The road to Pandamatenga and the Victoria Falls skirted the eastern edge of the Makgadikgadi salt pans and crossed the Nata or Amanzamnyama river at Madsiara drift and then entered the mopane forest. At Nwasha Pan, a perennial source of water, the Westbeech road from Tati (opened from about 1871) joined the road to Pandamatenga. Because of tsetse-fly north of Pandamatenga travellers were forced to walk across the headwaters of the Matetsi river to the Victoria Falls and the road continued to the confluence of the Chobe and Zambezi rivers, the gateway to Barotseland at modern-day Kazungula.

The Hunter’s Road to the west of Shoshong

Because the route to Matabeleland from the south across the Limpopo river was largely closed due to the prevalence of tsetse-fly, the Hunters’ Road was the best and most direct route into Matabeleland and well-marked by the paths of ox-wagon wheels. The section between Shoshong and Tati was 154 miles long (248 kms) and free from tsetse-fly and malaria fever except in the rainy season near Tati. The grass was sufficient for oxen except in the driest months and wandering bands of Khoisan hunter-gatherers and scattered groups of Tswana herdsmen posed no threat to travellers. The water essential for the oxen drawing the wagons was usually available at pools in the many tributaries of the Limpopo except in winter, but even then it could usually be found by digging into the sandy riverbeds.

The heavy rainy seasons created swiftly rushing run-off which cut deep channels in the riverbeds so the road crossed these streams at drifts which were either natural causeways or cut into the stream banks to create easy roadways for the ox-wagons. The sand made heavy work for the oxen and alternated with level stony ground covered by thorny bushes and occasional low granite kopjes. The sand was remembered and cursed by all; the scenery was mostly unvarying and many travellers found the journey from Shoshong to Tati uninteresting and hot and were constantly anxious about water supplies.

The first significant penetration of Matabeleland by Europeans 1854 – 58

On 18 May 1854 two young Englishmen, Samuel Edwards and James Chapman who had outfitted to travel upcountry met Robert Moffat at Kuruman to persuade him to trek with them as they knew he was a friend of Mzilikazi. Moffat agreed to accompany them as he wished to renew his friendship and prepare the way for new missions and also because he wished to get some news of his son-in-law David Livingstone from whom nothing had been heard for over a year. The fifty-nine year old missionary got on well with his younger companions whom he found agreeable and cheerful.[xi] They left in three ox-wagons on 22 May visiting Sechele at Old Molepolole and then left for Shoshong. They met with Chief Sekgoma who wanted traders and travellers to go no further than his town so he could monopolize the ivory trade with his own tribesman hunting the elephants and profit on the sale of their tusks.

Sekgoma ordered his tribesman and the Khoisan hunter-gatherers not to help the party and Chapman at this time left for Lake Ngami. Moffat and Edwards left Shoshong on 21 June but travel was slow without guides to point out the watering holes and drifts over rivers. They found the tribesmen would not be hired as guides for fear of displeasing Sekgoma, but for a little tobacco or meat they pointed out the way!

In early July after losing their way and much chopping down of trees and bushes and making drifts they arrived at the Shashi river.

A detailed description of the journey

The road ran initially along the base of the Mangwato Hills before turning north-east once the end of the range was cleared passing through sandy bushveld until after 40 kms the Mhalapshwe river was reached. If the pools in the wide dry stream bed were dry there was almost always water under the sand. The Mita river 6 kms further and the Towani river another 11 kms on, both tributaries of the Mhalapshwe, usually also had water. A trek of 16 kms over a sandy plain brought the wagons to Chakane pan, a pretty pool dotted with water lilies and shaded by surrounding trees when water was present, but just filthy mud before the rains. Springs to the south-east lay in a belt of tsetse-fly – an agonising choice in the dry season.

The next stage of 12 kms to Limone was through mopane forest and the following 16 kms to the Lotsane river were heavy going with deep sand as far as the rocky drift near the present railway station of Palapye Road. This area was notorious for aggressive lions before 1876. The Matswapong people living at the western end of the Chwapong Hills were well-known as ironsmiths.

8 kms from the drift were deep permanent pools of water but the presence of tsetse-fly during the day meant oxen were always watered here after dark. Many travellers were not informed of the presence of these pools by the local Khoisan hunter-gatherers ordered by the Bamangwato to keep them secret to handicap amaNdebele raiders. The route continued through another 11 kms of heavy sand to the Dikabia spruit which usually contained water. The water in the Seruli river 34 kms further on was salty, but drinkable and in the early days often frequented by lions, rhinos and giraffe.

A long stretch of 40 kms crossed the Chokana river and the western end of a range of granite hills before reaching the Khokwi river where the first baobab trees (Adansonia digitata) were encountered. The direction of travel thus far had been northeast, but here it swung northwest for 16 kms passing more baobabs and stunted mopane trees before reaching the drift of the Sedibi river shortly before it reached the much larger Maklautsi river, a short distance below the drift.

Another 11 kms brought the wagons to the Motloutsie or Maklautsi, the later recognised boundary between the Bamangwato and the amaNdebele whose broad watercourse of 100 metres comprised deep sand and large boulders. The next stage of 34 kms was often on rocky surfaces and twisted often to avoid sandy stretches and travelled through dense bush and groves of mopane trees before descending to the Shashe river, a major tributary of the Limpopo.

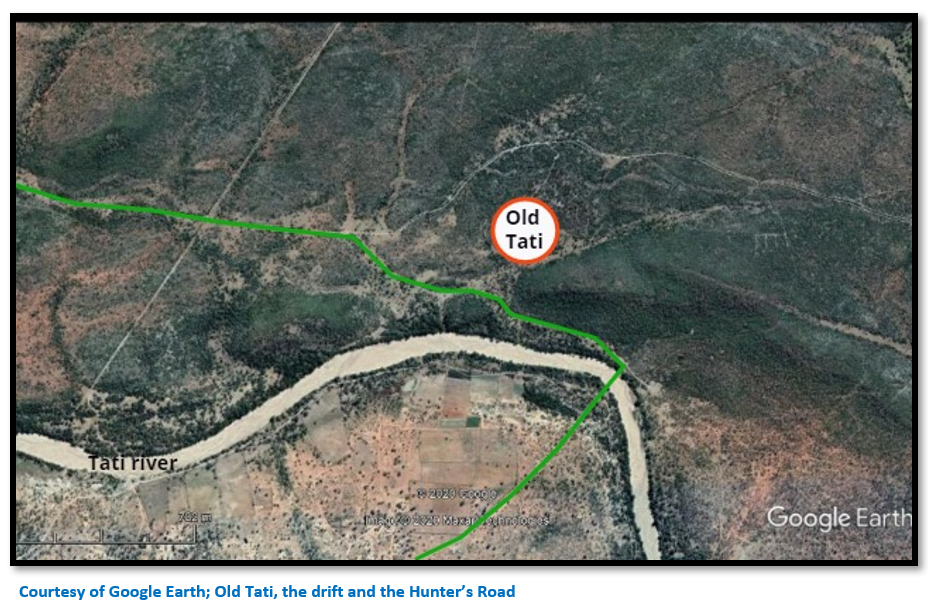

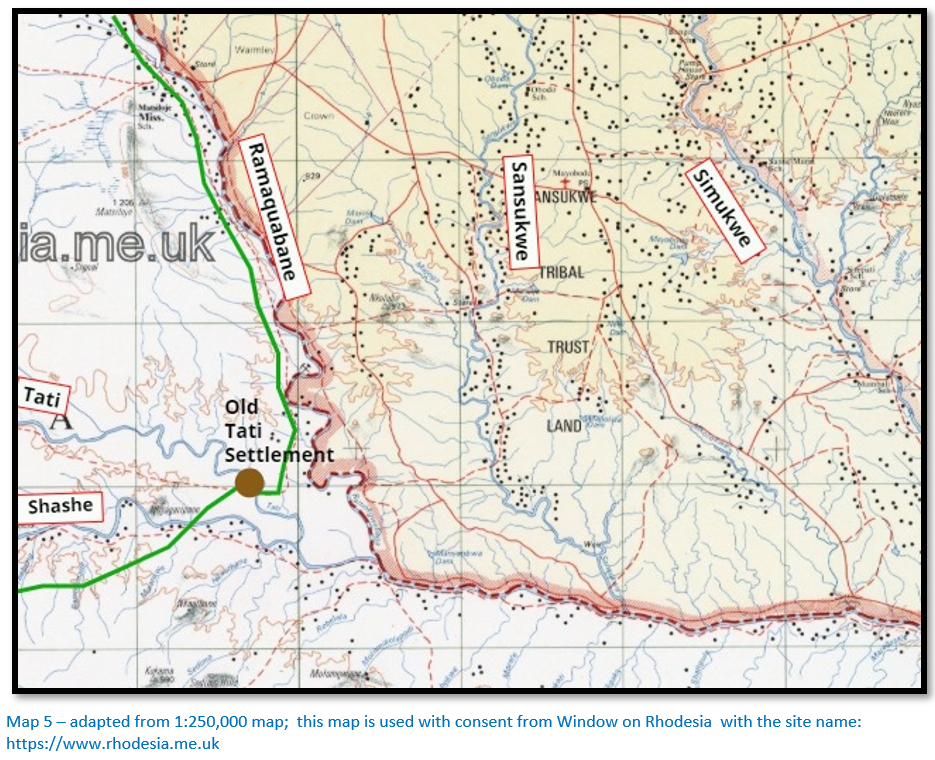

Although the riverbed was wide and sandy the drift was comparatively easy to cross; a kilometre below the drift was a deep permanent pool of water big enough for crocodiles to inhabit. A short trek of 11 kms through rocky hills brought travellers to Tati and completion of the ten day trek from Shoshong.

Tati

The land bordering to the south of the Tati district between the Shashe and Motloutsie rivers was claimed by both the amaNdebele and the Bamangwato and was in effect a ‘no-man’s land’ and called in later years the “Disputed Territory.”[xii] It was an area where the amaNdebele used to hunt and Khama’s people grazed their cattle, but in general they avoided each other.[xiii] After the granting of the first mining concession in 1870 which gave the Tati concession-holders the right to dig for gold, but did not confer land rights, one of the stipulations of the agreement was that Lobengula agreed to prevent his amaNdebele warriours from raiding in the area and to let the Europeans rule themselves with little formal law or laid-down procedures.

Reasons for the existence of Tati

The Bakalanga prior to the arrival of Europeans mined surface outcrops of quartz veins for their gold along the Tati River using an open-stope form of mining. The first European to follow up reports on the gold diggings was Henry Hartley who hunted in the region during each winter season with his family before returning to his farm in the Magaliesberg range. In 1866 and 1867 Hartley brought the young German geologist and explorer Karl Mauch with him to examine the gold workings. It was Mauch’s enthusiastic accounts to the Transvaal Argus stating he believed this area was the Ophir of the Bible and the El Dorado of the ancients that excited readers – this story was repeated in the newspapers in Europe, America and Australia.

His reports led to the first European gold rush in Southern Africa as prospectors all over the world packed their bags for South Africa and having arrived enquired about the road to the north. Sir John Swinburne arrived at the same time as Thomas Baines in Potchefstroom. The town was booming as prospectors and miners stocked up with all the essentials necessary for the long journey to the Tati goldfields – around 250 miners and prospectors were active in the area.[xiv] In 1870 Lobengula granted Swinburne’s London and Limpopo Mining Company a mining concession and the company worked its claims under Captain Arthur Levert bringing stamp mills and steam engines to Tati, but by 1880 the concession had been revoked for failure to pay the £60 annual fee and the concession was granted to Northern Light Mining Company, a syndicate formed by Daniel Francis, Sam Edwards and others.

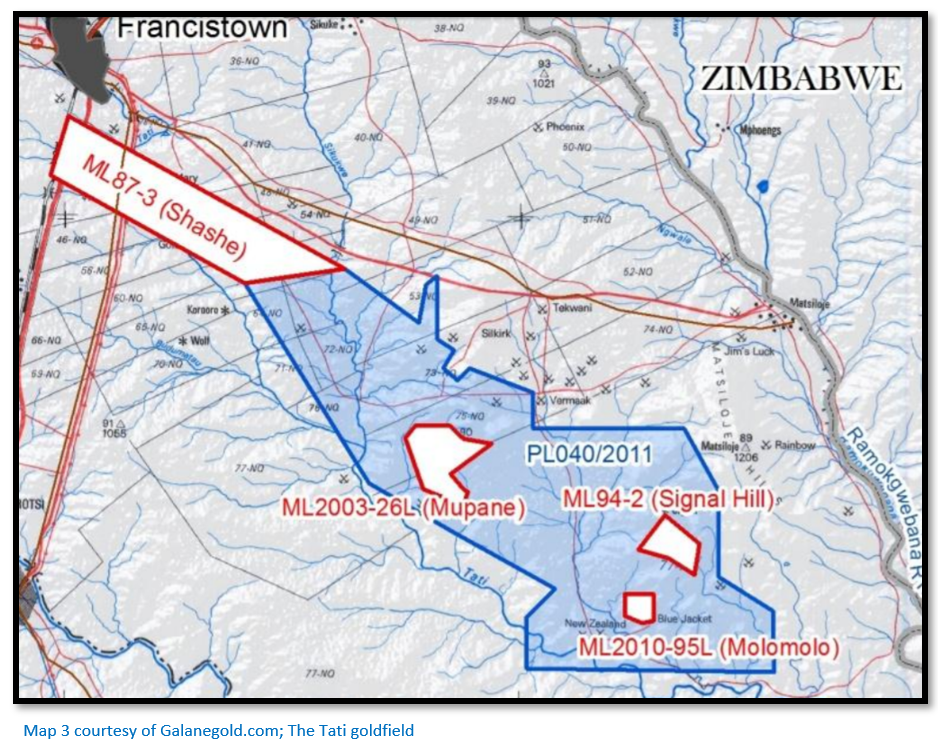

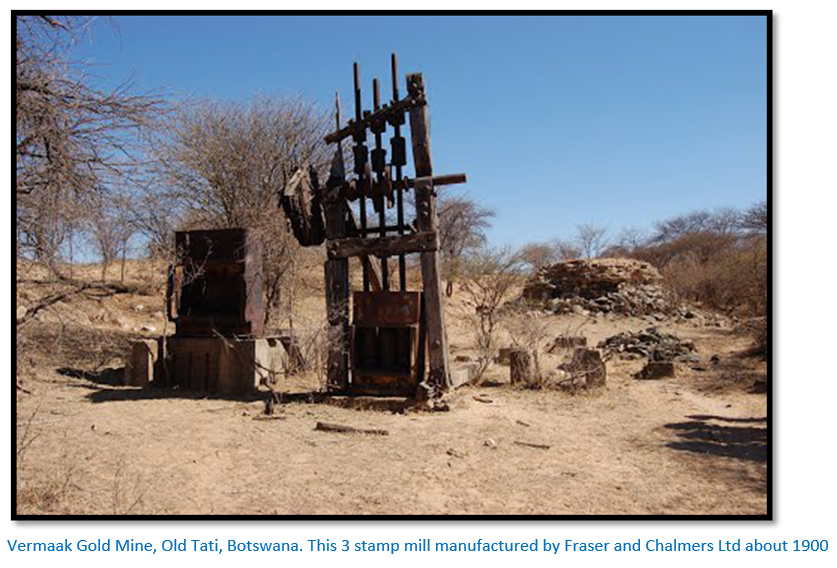

Daniel Francis had first arrived in 1869 but the gold was difficult to extract without machinery and most gold miners soon left for the Kimberley diamond fields. Francis had returned in 1880 and obtained his mining concession from King Lobengula; when the railway arrived in 1897 Francistown was named after Francis who owned most of the land by then. There followed an upsurge of mining activity; between 1866 to 1963; it has been estimated over 200,000 oz of gold (6,220 kgs) were produced from 60 mines in the area - some of the historic mines being the Mupane, Signal Hill, Vermaak, Jim’s Luck, Blue Jacket (the pre-European workings were 28 metres deep) New Zealand (reputed to have reached a depth of 360 metres) and Golden Eagle.[xv]

Old Tati

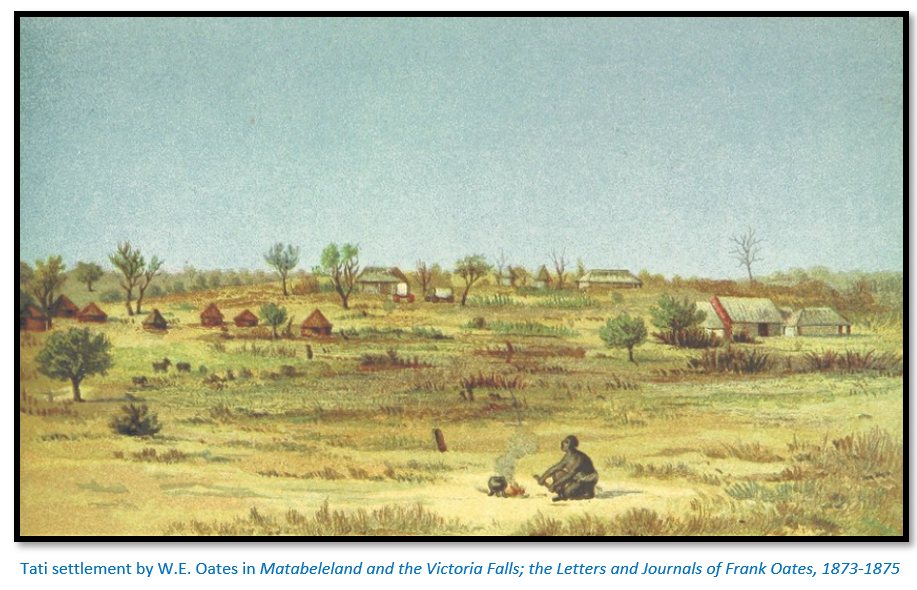

Until the gold rush of 1868 the Tati river was just another stream to be crossed on the road to Matabeleland, but once the settlement was formed it rivalled Shoshong as a base for travel to Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls as it was closer to these objectives and controlled by Europeans which made it a good place to rest and where the few Bakalanga natives made no trouble. Houses and stores were built on the slopes of two low hills on the northern bank and either side of the road from the drift. Soon the slopes of the hills around the settlement were dotted with spoil heaps as prospectors tested the quartz reefs.

Before Old Tati was established the surrounding countryside had been home to elephant, rhino and giraffe; early residents of Old Tati were forced to erect thick thorn barricades around their huts to keep out the lions and protect their stock. Lions often roamed at night; but a lioness was killed at noon once in Old Tati and a native labourer mauled near the steam engine. Hunts were organised by the residents to keep down lion numbers.

The Tati river was generally dry across its 200 metre sandy bed with pools below the drift and water could be found by digging. When the rains began the river flowed quickly; on 21 December 1877 the river rose 3.7 metres (12 feet) in eight hours and generally flowed freely during January and February in most years.

When Thomas Baines first arrived in December 1870 most miners had departed for the diamond fields and he found some of the buildings in ruins and others burned down. The London and Limpopo Mining Company continued operations on a small scale under a Swede named Nelson until work was suspended in 1874. Alexander Brown, a Scotsman, kept a store at Old Tati in the 1870’s and the Boer hunter Piet Jacobs appropriated a house for his family; he and Brown were the longest staying residents of Old Tati.[xvi]

After the gold boom the settlement became locally important as a road junction and convenient base for operations and the seasonal home for traders and hunters although by 1871 most of the game in the area had been shot. Old Tati is 46 kms south-east of Francistown as measured on Google Earth.

A small cemetery at Tati commemorates the first Jesuit missionaries here. The two, Father Charles Fuchs SJ (1839-1880) and Father Anthony De Wit SJ (1823-1882) are buried in the cemetery with six unmarked graves and one inscribed with the words, ‘IN MEMORY OF JAMES TAYLOR OF KLERKSDORP TRANSVAAL. BORN IN ABERDEEN, SCOTLAND, DIED 23 MARCH 1878 AGED 40 YEARS’.

The Jesuits arrived at Tati on 17 August 1879 where they were well received by the traders; Father Depelchin decided to start a mission here at Tati, the first mission of their province, named the Good Hope Mission and later Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Plans were afoot to build a chapel, school and establish an orphanage. However, the missionaries faced many challenges including malaria fever, lack of funds and transport and manpower which were responsible for the mission lasting only for a period of six years to 1885.

In June 1874 Lobengula imposed what were quarantine restrictions against redwater, a tick-borne cattle disease that became widespread amongst cattle from the Transvaal and Natal. Trekkers were forced to leave their span of oxen at Tati and change them for local oxen which local traders kept for the purpose before going on. A guard of amaNdebele enforced the restrictions greatly annoying the Europeans and plundering any Bakalanga returning from the diamond fields with newly acquired guns and ammunition.

The Hunter’s Road into Matabeleland and beyond

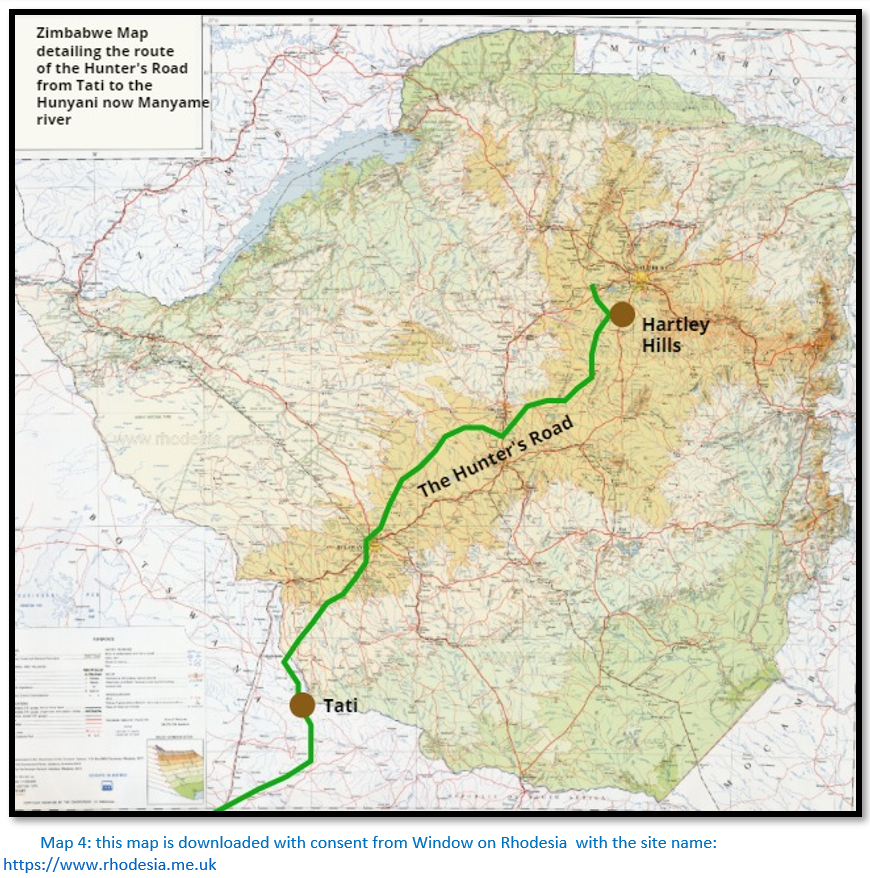

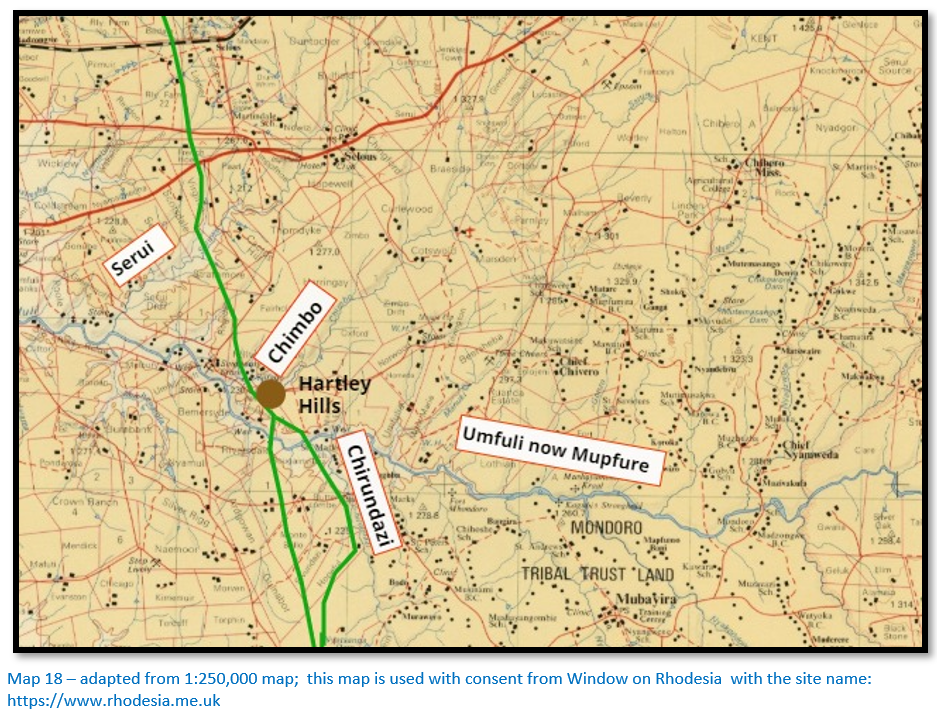

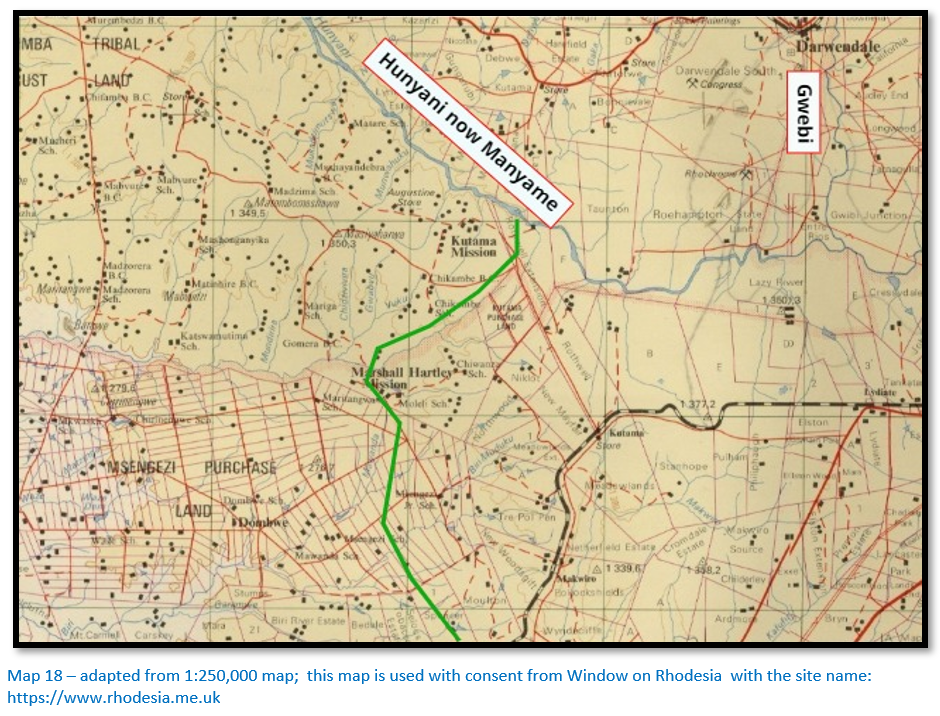

Below a map shows the Hunter’s Road through Matabeleland and Mashonaland to its end on the Hunyani, now Manyame river.

Tati to the Ramaquabane river

After passing through the hills north of Tati the road crossed the valley of the Blue Jacket reef before skirting Signal Hill and continued through alternating belts of Mopane and thick thorn bush, the Afrikaans wacht-en-beetje (wait-a-bit thorn) to Mopane Pan. This was a small reedy vlei but a popular camp-site because the Mopane trees offered shade and the road from here ran straight to the Ramaquabane river. Distances were 10 kms (6 miles) to the Blue Jacket spruit, 10 kms (6 miles) to Mopane Pan and 14 kms (9 miles) to the Ramaquabane.

Moffat and Edwards in 1854 had to coax their reluctant guides to take them further than the Shashe. The descent down the river-bank was steep and the ox-wagon crossed the sandy bed of 75 metres. Next day saw them at the Ramaquabane river and the oxen were rested before their attempt to cross the 275 metres of deep sand into which the ox-wagon wheels sank. An axle on Edward’s wagon broke and they spent a day fitting a new axle from acacia wood.

Their guides were persuaded to go on for payment of two knives, two tinderboxes, two snuffboxes and some beads and they trekked with the Ramaquabane on their left. [note the Hunter’s Road was established later on the other side of the river] but their guides left next day from fear of Sekgoma and the amaNdebele.

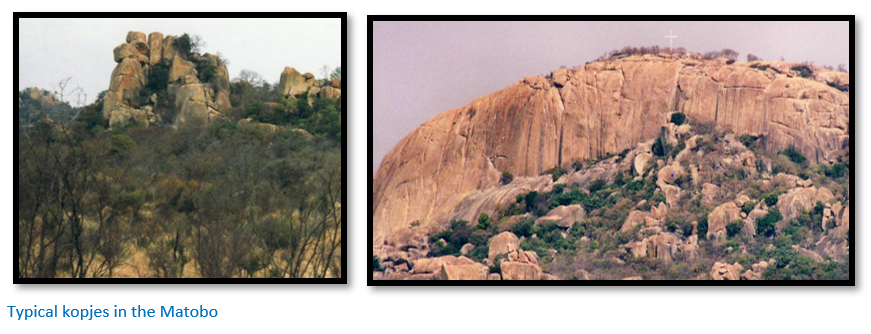

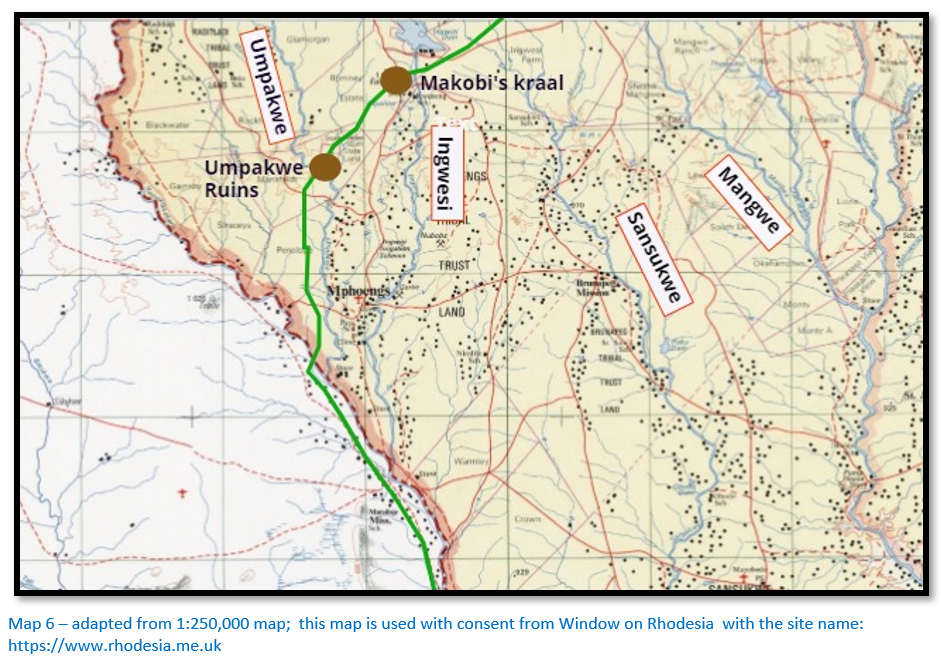

Ramaquabane river to Makobi’s kraal

For most of the year there was little water in the Ramaquabane unless travellers dug below the sands or found a hole dug out by elephants. Wagons often stuck in the sand crossing the river which was about 90 metres wide. The Umpakwe river was 15 kms (9.5 miles) from the Ramaquabane drift and the countryside was becoming dotted with granite kopjes made up of piled-up and scattered boulders or the bare ‘whalebacks’ with piles of rocks at their base and densely packed with euphorbia, aloe, wild fig, wild rubber and other trees and shrubs.

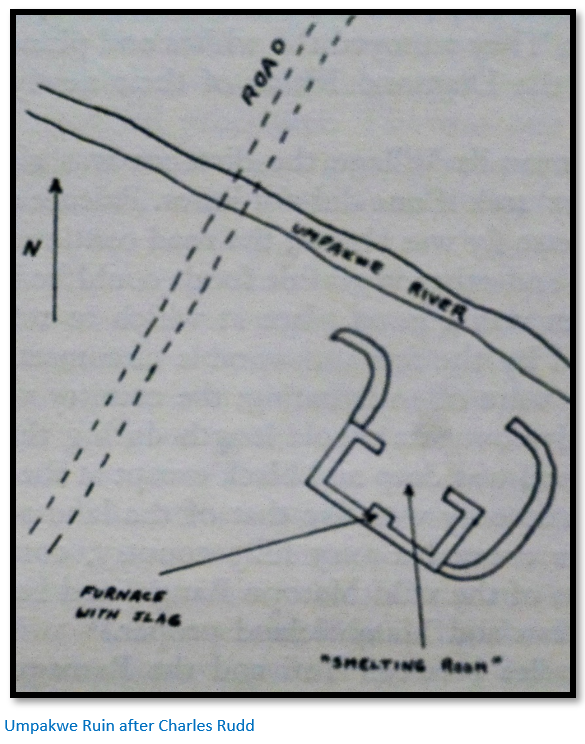

The Umpakwe usually had pools of water along its course with a difficult drift to cross. 150 metres to the right of the road and on the south side of the Umpakwe was a ruined dry-stone wall with a chevron pattern at its base. Three circular raised platforms of clay - previously hut bases, were inside the wall. Here George ‘Elephant’ Phillips found a copper bar and a pipe of fireclay. This and the presence of iron slag caused Phillips, Oates and Selous to speculate that the ruins had once housed a gold or copper smelter and that the platforms were ‘roasting platforms.’

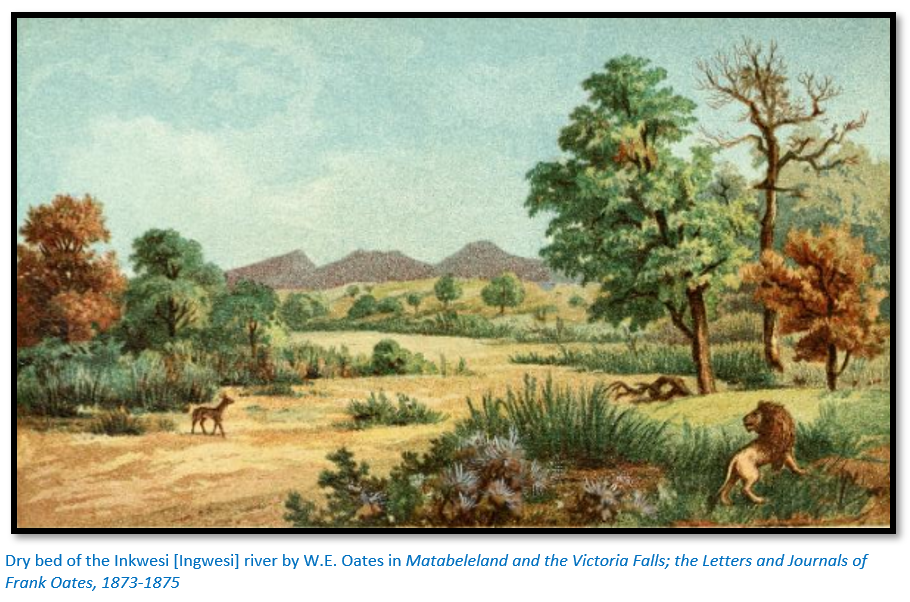

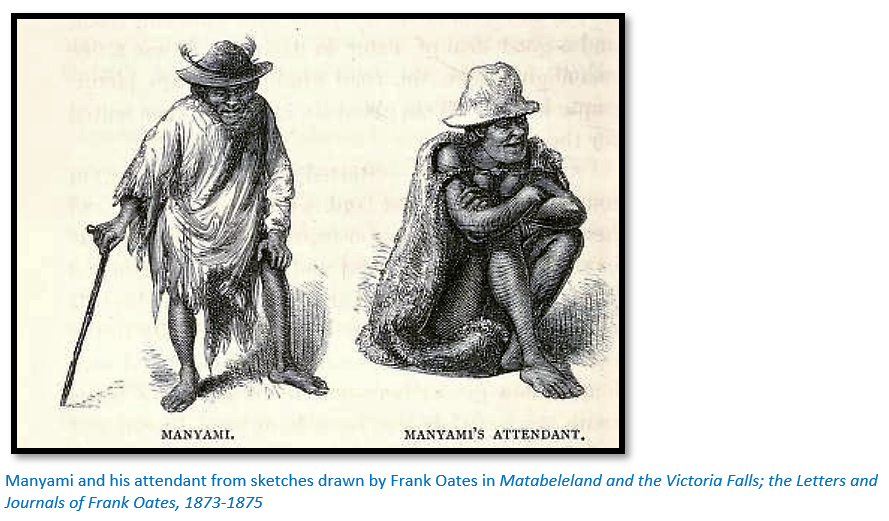

It was an 18 kms (11 mile) trek to the Ingwesi river through picturesque granite hills and the road crossed a number of small streams in narrow valleys. The perennial streams were looked on with delight after the dry and dusty haul from Shoshong to Tati. About 400 metres beyond the Ingwesi drift was Makobi’s kraal occupied by Bakalanga, a people linked with Mapungubwe, Khami and the Rozvi Empire. A huge baobab was a notable feature in this deep valley between hills. Although Makobi was Chief, he was outranked by an amaNdebele induna named Manyami who was stationed at this point to ensure no outsider entered Matabeleland without permission from King Mzilikazi.

Visitors were forced to wait until Manyami had sent a message to the King and received a reply telling him they were admitted or turned away. This was main function of Makobi’s kraal until March 1863 when the amaNdebele destroyed the kraal and killed Makobi and most of his people for an alleged treasonable offence. For the next ten years the new reporting kraal was then established 64 kms (40 miles) further down the Hunter’s Road. In 1873 – 4 a new outpost was re-established at the site of Makobi’s kraal and Manyami returned to his old post.

Moffat and Edwards trekked on using a compass and climbing small hills to get sights and proceeded up the riverbank of the Ingwesi noting the countryside was devoid of people and wildlife. Eventually they met some Bakalanga who initially ran away thinking they were Boers but relaxed after being given wildebeest meat. They stopped short of Makobi’s kraal and Manyami soon came down to meet them. Once Manyami learnt Moffat was one of the travellers they were escorted to the kraal.

About twelve Bakalanga families lived here with four amaNdebele women who had been banished for witchcraft where they cultivated the lands and tendered some of Mzilikazi’s cattle. They were hungry for meat so Edwards killed eight zebra. Whilst the oxen rested for two days Manyami sent word to the King to announce Moffat’s presence. They set off on the 13 July with Makobi in charge of the escort.

Frank Oates wrote:[xvii] “Old Manyami is the man who used to stop all wagons coming into the country til the King had given them leave to proceed and he stopped me when I first came myself as I daresay I told you at the time. This is done at a different kraal now – the first one passed by any wagons going from here to Gubulawayo about forty miles north-east of Tati. In the meantime I remained on the Ramaqueban [Ramaquabane] my ally riding over to Tati once or twice.

Whilst I was here a trader by the name of Horn[xviii] passed and had to wait when he was a few miles on the road to ask leave to proceed as all wagons on the road are now stopped for fear of the disease and Horn had to explain who he was and where he came from. Horn, I think, is the man who opened the Zambesi trade but is at present trading with the Matabele. A lion killed one of his oxen on the Inkwesi [Ingwesi] one night whilst he was waiting here and a dozen of them took fright and ran away.”

The disease which forced Horn to stop was an outbreak of redwater among the cattle in the Cape Colony. Lobengula put a complete ban on trek oxen of all travellers into Matabeleland until he was satisfied the outbreak was controlled.[xix]

Thomas Baines wrote: “We now left the quartzose country and passed through ranges of picturesque granite hills with forests at their base and huge rocks bearing often a grotesque resemblance to animals or other familiar objects. Crossing their summits we reached Manyama’s kraal on a spruit of the Shashani when Mr Lee explained to him the general purpose of my visit and desired him at once to send forward special messengers to announce my arrival and to call together the council of the nation to hear the contents of His Excellency’s letter.[xx] We remained here from 16 June ‘til the beginning of July when two petty chiefs were sent by order of Um Nombata from Umbeko’s kraal. They showed much curiosity respecting my business and the contents of the letter. I desired Mr Watson, my interpreter to tell them that the letter could be read to no one but the chief or chiefs in council of their nation, but that I recognised the name of Um Nombata as the great and venerable councillor of the late king…”[xxi]

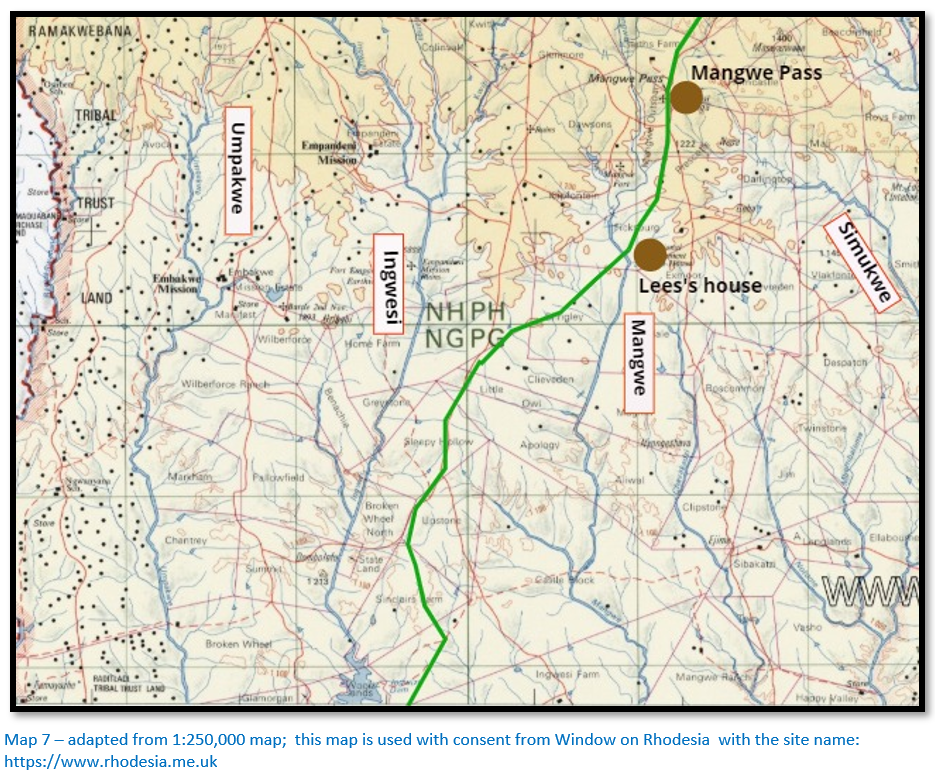

Makobi’s kraal to Mangwe Pass

After the Ingwesi river Bakalanga villages became more frequent and the road was lined with cultivated fields protected by fences of sticks and hedges. If horses or oxen broke into the field damages were usually paid in trade goods such as beads or copper wire. After 32 kms (20 miles) trekkers reached Sawpit Spruit a rivulet feeding the Mangwe river and the spot where Thomas Baines later made a sketch. This spot was John Lee’s first cattle post and 6 kms (3.5 miles) further on the Mangwe, a perennial river was reached.

John Lee hunted elephant in Matabeleland with the permission of King Mzilikazi and after five years was granted a farm in the Mangwe valley. He became the ‘customs and immigration’ agent for both Mzilikazi and Lobengula in their dealings with Europeans and gained great influence with the amaNdebele. His farm was 97 kms (60 miles) from Tati in a valley with numerous rivulets to the Mangwe river and he grew vegetables and fruit trees in gardens. However his main business was oxen which were often bought as replacements by passing travellers. His farmhouse was spacious and comfortable, the chairs covered in leopard skins and Baines even left a painting that showed Lee hunting elephants.

Before 1870 his farmhouse was south of the Mangwe beside a small tributary, but in November 1870 he built a new farmhouse just north of the Mangwe drift where a trader named Elstob had started a store.[xxii] The new house measuring 15 x 5 metres (50 x 16 feet) with walls of mopane logs and a thatched roof had verandas front and back and was divided into a hall, dining room and two bedrooms. It was within sight of two prominent granite landmarks: Lee’s Rock and Lee’s Castle.

Baines writes: “We crossed the Ramoqueban, the Impaque, the Umkwesi and a small branch (afterwards called Sawpit Spruit) of the Mangwe river. Here Mr Hartley introduced us to Mr Lee, who not only perfectly understood the language and customs of the Matabili but was privileged to hunt and reside in the south western district, had long enjoyed the confidence of the late chieftain Umselekatze and was generally regarded as his agent in all business affairs with white men.”[xxiii]

From Lee’s house the road continued over several sharp rises, the hollows containing feeder streams to the Mangwe river and then entered a range of granite hills through the Mangwe pass; sometimes called Tiger Port. The view through the pass revealed a sea of jagged kopjes that stretched away into the Matobo.

Moffat and Edwards cut a path through the trees making good progress with their escort and slept at the Mangwe river.

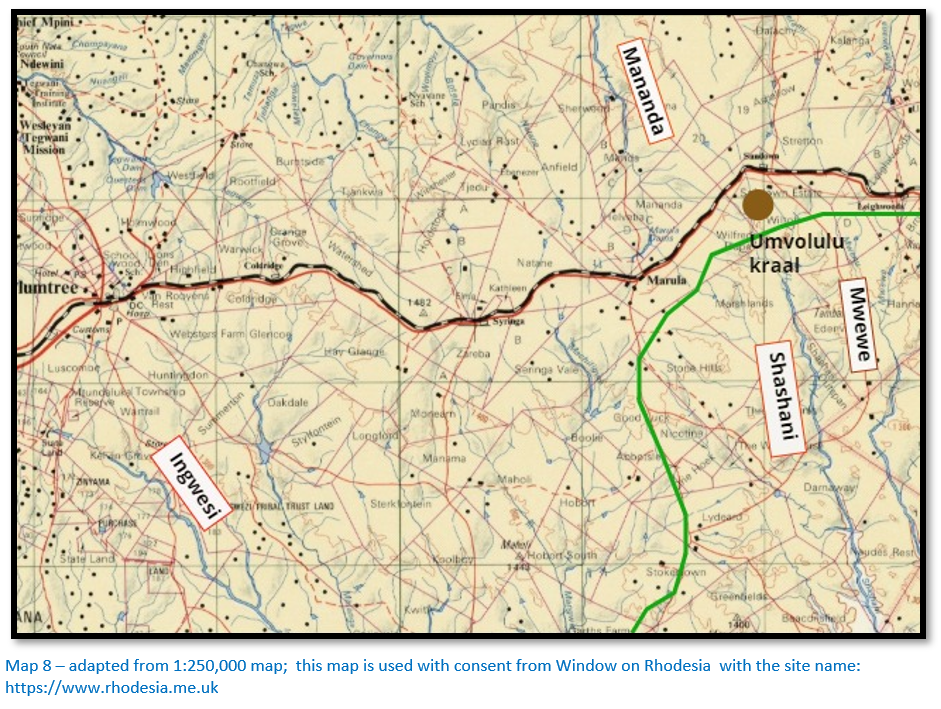

Mangwe Pass to Umvolulu kraal

The Semokwe river, another perennial stream, was reached after leaving the Mangwe pass and was 10 kms (6.5 miles) from Lees and after 7 kms (4.5 miles) the road reached Umvolulu, a Bakalanga kraal governed by Manyami the induna who guarded the entrance to Matabeleland between 1863 – 1873 before moving back to the site of Makobi’s kraal. Sited near the headwaters of the Shashani river travellers were offered honey, grain and vegetables for barter when the villagers had a surplus.[xxiv]

Next day Moffat and Edwards crossed the Semokwe and outspanned at the Shashani which had some water. The following day they reached Umvolulu kraal where they waited for runners to return from Mzilikazi. Mzilikazi doubtful that his friend ‘Moshete’ had really come at last told the guides to detain him for three days whilst the visitor was positively identified. AmaNdebele who had known Moffat as boys quietly examined him at a distance and assured Mzilikazi he was genuine. Martinus Swartz, a Boer hunter was camped at Umvolulu waiting for permission to proceed. On the evening of the 18 July two messengers arrived from Mzilikazi sending extravagant compliments of welcome to Moffat. The next day when Moffat suggested they leave in the afternoon to give the messengers a rest, they declared they would not rest until Moffat was with the King and insisted on leaving immediately.

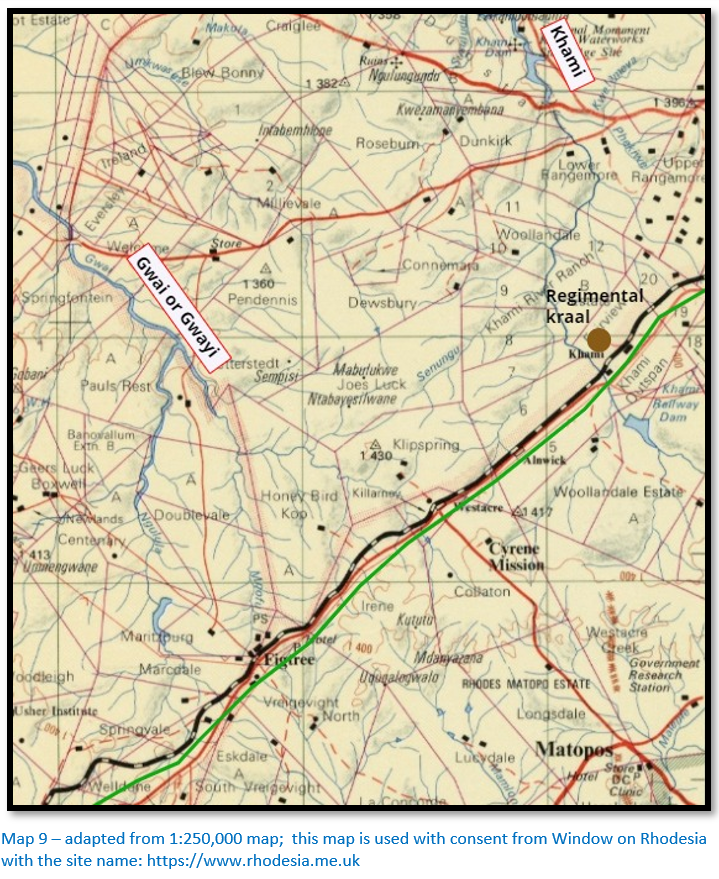

Umvolulu kraal to Khami river

The countryside here was well wooded but comparatively easy going and flat with numerous Bakalanga villages with planted gardens along the headstreams of the watershed. At the ‘top of the hill’ the headstreams of the Tuli drainage system were on the right-hand side and those of the Gwaai on the left; the road kept to the Tuli side of the watershed. About 8 kms (5 miles) from Umvolulu kraal at Tiger Bush[xxv] the road took a more northerly route crossing the headwaters of the Gwaai river and now keeping to the northern side of the watershed. The Khami river was reached 56 kms (35 miles) from Umvolulu kraal and consisted of long deep pools; in Lobengula’s time there was a regimental kraal at the Khami drift and the countryside around had been gradually deforested.

Baines writes: “We crossed the Shashani and climbed to the ‘top of the hill’ or watershed between the Limpopo and Zambesi systems. Brooklets trickling to the former on our right and to the latter on our left while proteas of considerable dimensions bordered our path. We crossed the Kumalo [Khami] or Royal River (a principal source of the Gwali [Gwaai] which I had visited near its junction with the Zambesi in 1862) and after we had outspanned were met by Captain Levert’s wagon coming from Sir John Swinburne at Inyati and bound to Natal for machinery. Here on account of the exhausted condition of the oxen I found it necessary to leave Jewell and Watson with one wagon ‘en cache’ under the protection of the young Prince Lo Bengula while I with Mr Nelson and Mr Lee proceeded with the other. We crossed the Umthlambo Boloi (the Bath of Majesty) on the Um Kosi or King river and spanning out at night on a waterless flat were aroused by the attack of a lion on our cattle. Of course every one sleeps outside to spring up fully armed at the first alarm. The cattle in terror were already breaking out of the kraal when I heard them and drove them back. My companions stood to their posts to guard the horses or other points of attack. Little Jack barked as lustily as if his small voice were backed by the power of a wolf hound. The lion circled round to the bivouac of our guides and they igniting the grass they had used for their bedding tossed it up high overhead filling the air with scattered sparks and flame and firing on the lion when the light revealed him…The horses strayed in the morning but were brought back by the people of the next village. Mr Nelson while out looking for them saw the lion but being armed only with a revolver did not fire on him.

At the military kraal of the Twong Endaba Regiment numbering perhaps 800 men and entrusted with the care of some thousands of the national cattle we saw Umbeko and as Mr Lee insisted on reading the letter to none but the great chief of the land, or to all the chiefs in council, it was at length decided that the Regent Um Nombata was in his own person sufficiently empowered to hear it and consider my application.”[xxvi]

Nombata agreed to let Baines continue as long as he promised to return by the same route and tell him if he had found gold.

Moffat and Edwards left with their escort on 19 July 1854 crossing the watershed and the headwaters of the Gwaai and after crossing the Khami river went to a kraal headed by Willem the Griqua who lived with the amaNdebele. Here they saw the rotted hulk of a wagon with broken chests, plates and rusted guns the Cape Government had presented to Mzilikazi after the signing of the Anglo-Matabele treaty of 1836; the local people swarmed from their kraal to view Moffat.

The route descended to the east, the old grass was being burnt off and the smoke from fires hung like an “extended, dense thundercloud.” Another of Mzilikazi’s messengers arrived telling them to “beat the oxen and hasten.” That night an ox was driven in from the King so they could prepare themselves for an early start next day. Moffat thought it “kindly intended, but not according to our way of doing things.”

Khami river to King Lobengula’s kraal

Amandebele capitals moved approximately every six to ten years; the soil around might be exhausted, the trees cut down for firewood and kraal construction, the grass and water supplies might be exhausted by increasing cattle numbers or because of the death of a favourite wife of the King.

For instance, Mahlokohloko which was visited by Robert Moffat in 1854 appears to have been on the right bank of the Intembeni river a tributary of the Umguza river, but by 1857 it was just north of the Inkwekwesi river west of Inyati, but by 1859 it had moved 500 metres from the previous site. Prior to this in 1840 Mahlokohloko was said to have been sited near Ntaba Zinduna.

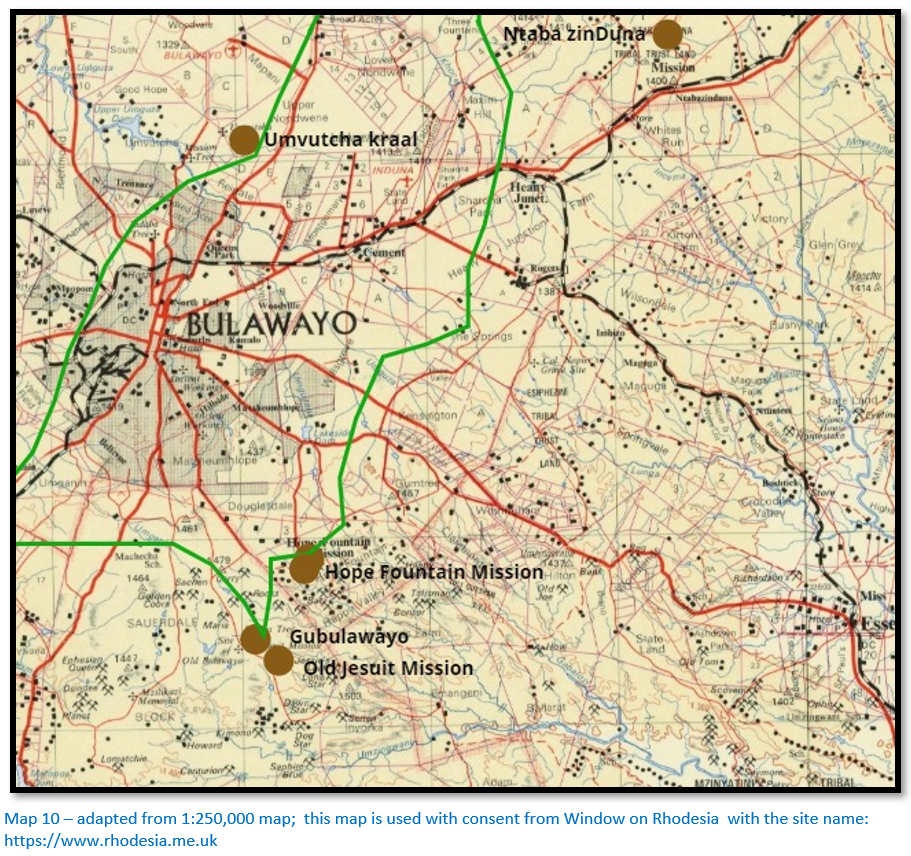

In 1863 Mzilikazi built a new capital, Mhlahlandlela south of the Khami river. The Hunter’s Road passed close by the kraal. During the latter half of Lobengula’s reign all travellers stopped at Umvutcha or ‘white man’s camp’ where a number of traders including Fairbairn and Dawson built stores and homes. All Europeans called on Mzilikazi and later Lobengula to pay respects and to present the King with gifts.

Old Gubulawayo founded by King Lobengula and inhabited during the 1870’s was on the southern side of the watershed and sited near a tributary of the Umzingwane river which flows into the Limpopo. From the Hunter’s Road a road led from the Khami drift and towards its source and south-east towards Gubulawayo. The kraal was 74 kms (46 miles) from Umvolulu and had a brick house built by John ‘Mubi’ Halyet who may have jumped ship at Cape Town. By 1877 a number of resident traders has established stores here and in 1879 the Jesuits received permission from Lobengula to establish a mission a kilometre away with Fathers Depelchin and Croonenberghs the first residents. [See the article Old Jesuit Mission under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] In August-September 1881 Lobengula transferred his capital to the present site of Government House near Umvutcha and the kraal at Gubulawayo was burnt to the ground.

From Gubulawayo the eastern arm of the Hunter’s Road went to the London Missionary Society’s Hope Fountain Mission founded in 1870, the second oldest in the country after Inyati. [For an account of the remarkable friendship between Robert Moffat and Mzilikazi and details of Hope Fountain Mission see the article under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com ] The road then crossed the little Umguza river and the Umguza river passing Ntaba Zinduna hill on the right and going north over the Khoce[xxvii] before the eastern and western versions of the Hunter’s road merged at Induba near the Zwangendaba kraal.

As the Moffat and Edwards’ wagons approached Mahlokohloko [Gubulawayo] on 22 July 1854 they were met by small groups of amaNdebele who urged them on. They were taken to a fenced enclosure used for public audiences around which sat fifty izinDuna and Mzilikazi, his feet crippled, sat in a small doorway in the far side of the fence. The King repeated “Moshete” over and over and threw his kaross over his head to hide his tears. Then he began telling Nombata about his happiness.

His weeping surprised Edwards who had heard about Mzilikazi’s savagery. Mzilikazi’s feet had dropsy, the old-fashioned term for oedema and were painful and he hoped his old friend may be able to cure him. Moffat presented Mzilikazi with two armchairs and basins and a water jug from Mary Moffat. Edwards gave him a shawl, cloth and beads.

Moffat and Edwards stayed a month at Mahlokohloko. The missionary rubbed the King’s feet with ointments and told him to stay off beer and on 26 July the King walked unaided to the wagons. He visited the wagons parked in the royal cattle kraal every day and his mood improved with his health. He was happy to be in Moffat’s presence and as an interpreter they used Willem the Griqua.

Moffat spent some time correcting the proofs on his Sechuana Old Testament, repaired some guns and made tin spoons and plates. Edwards did some hunting and saw to the camp work. Edwards thought highly of the King; his generosity, good manners and friendship and the King declared that Edwards was his son and that he admired him as much as Moffat.

Edwards bought 900 kgs (2,000lbs) of ivory from the King, but was not allowed to hunt elephant which was the King’s monopoly. Willem the Griqua told Moffat that he and his wife named Truey wished to go home to Griqualand and urged Moffat to ask the King for his release.

Nombata, an old man in 1854 who lived another seventeen years, was a friend of Moffat. The amaNdebele were kind and considerate to their guests and gave information about Mashonaland and the Zambezi; they were shown Tower muskets bought on the lower Save river that the King insisted were from Englishmen. However, whenever the topic of religion came up the King changed the subject, closed the conversation or merely agreed politely and avoided the Sunday services held at the wagons.

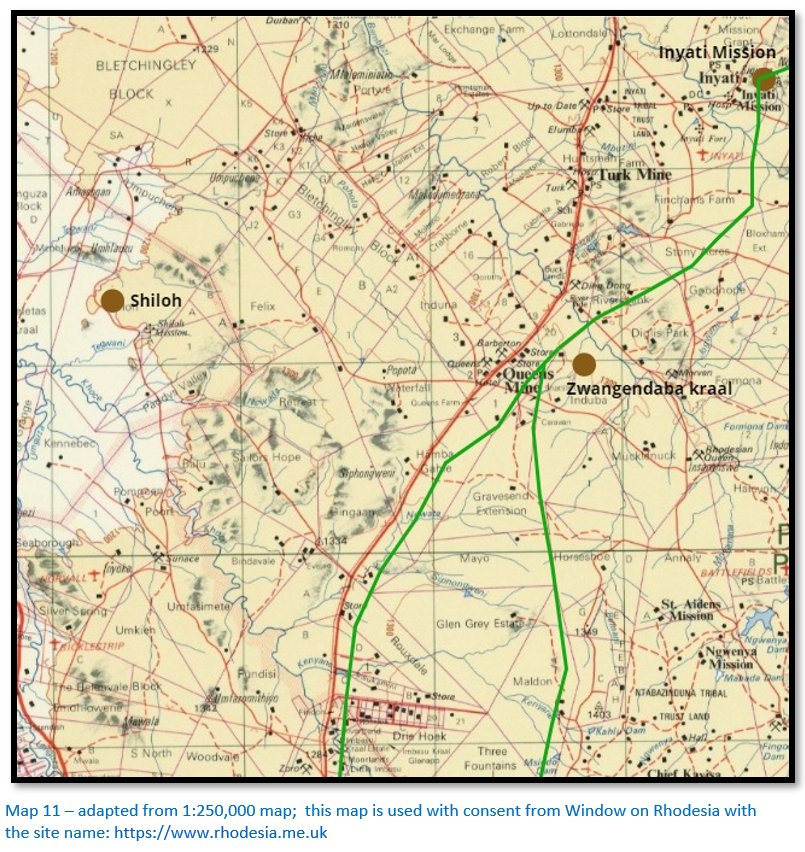

Umvutcha to Inyati Mission

The distance from the Khami river to Inyati was 85 kms (53 miles) or about three days trekking. Umganen spruit was 10 kms (6 miles) from the Khami river; the Umguza river was a further 19 kms (12 miles) and from the river the road ran northwards through heavy sand. A number of small streams were then crossed including the Khoce and the road passed various amaNdebele kraals before reaching the large kraal of the Zwangendaba regiment just south of the Bembesi river at Induba.

The steep banks of the drift at the Bembesi was difficult to negotiate although the river was dry for much of the year. The Inkwekwesi river was reached 14 kms (9 miles) after travelling over a succession of small ridges and valleys; its sandy bed was wider than the Bembesi and usually contained water. Just north of the drift was the Emhlangeni kraal of the Inyati (Buffalo) regiment and Inyati, now Inyathi Mission was reached 1.5 kms (1 mile) further on.

Inyati Mission was the most distant station of the London Missionary Society and the first Christian mission in Matabeleland and was established through Robert Moffat’s long-term friendship with Mzilikazi. Founded in December 1859 at a small but perennial tributary of the Inkwekwesi river the earliest missionaries included William Sykes and Thomas Morgan Thomas, although Thomas moved from Inyati and established a new mission 30 kms to the south-west at Shiloh in 1874.

Shiloh at a height of 1,200 metres was situated on the Tegwani a small tributary of the Khoce which flowed into the Umguza river. Thus it was a comfortable climate with fertile soils and plentiful water; the garden and orchard were always praised by visitors. The road to Shiloh left the Hunter’s Road 6 kms (3.5 miles) from the Khoce in a northerly direction, a distance of 21 kms (13 miles)

In early July 1866 there were twenty-two Europeans at the King’s kraal, now on the Umguza river; a fact that alarmed Mzilikazi and his izinDuna’s. They had spent some time at Umvolulu kraal, but with Mzilikazi weak and near death Manyami was beginning to disregard the custom of awaiting approval from the King and let them continue their journey for two pounds of beads. Henry Hartley’s group comprised; Henry Hartley, his sons Tom and Fred, son-in-law Thomas Maloney, Christian Harmse, an experienced old Boer elephant hunter and Karl Mauch. Hartley had seen shafts and open-stopes in Mashonaland which he suspected were evidence of abandoned gold-mining efforts – this was confirmed by local Mashona and Mauch was his expert to confirm these discoveries. William Finaughty and the other party comprising George Phillips, James Gifford, Thomas Leask, Phil Smith, J. Fenwick Wilkinson, and their driver Frank, an Englishmen notorious for dishonesty and untruthfulness made a total of five ox-wagons and twenty-four horses. They left for the Hunter’s Road on 11 July and were accompanied by Inyoka (snake) a minor inDuna assigned to this large hunting party by Mzilikazi with instructions to be strict and keep a careful watch on them.

Finaughty was tired of trading and wanted to take up elephant hunting again and left his wagon and span of oxen at Inyati with Reverend Sykes. Leask described the missionaries as “honest, hard-working and conscientious.” They left behind the last of the amaNdebele kraals and trekked through the territories occupied by Mashona under amaNdebele rule.

Inyati to the Shangani river

The Hunyani, now the Manyame river in Mashonaland was the ultimate destination and end of the Hunter’s Road – it was 327 kms (203 miles) from Inyati Mission to the Hunyani river or about eighteen days trekking by ox-wagon.[xxviii] The route kept mostly to the north of the watershed (i.e. on the Zambesi side of the divide) and mostly on the highveld as can be seen from map 4 thus avoiding the worst of the malaria and the belts of tsetse-fly; the first often fatal to humans and the second fatal to oxen.

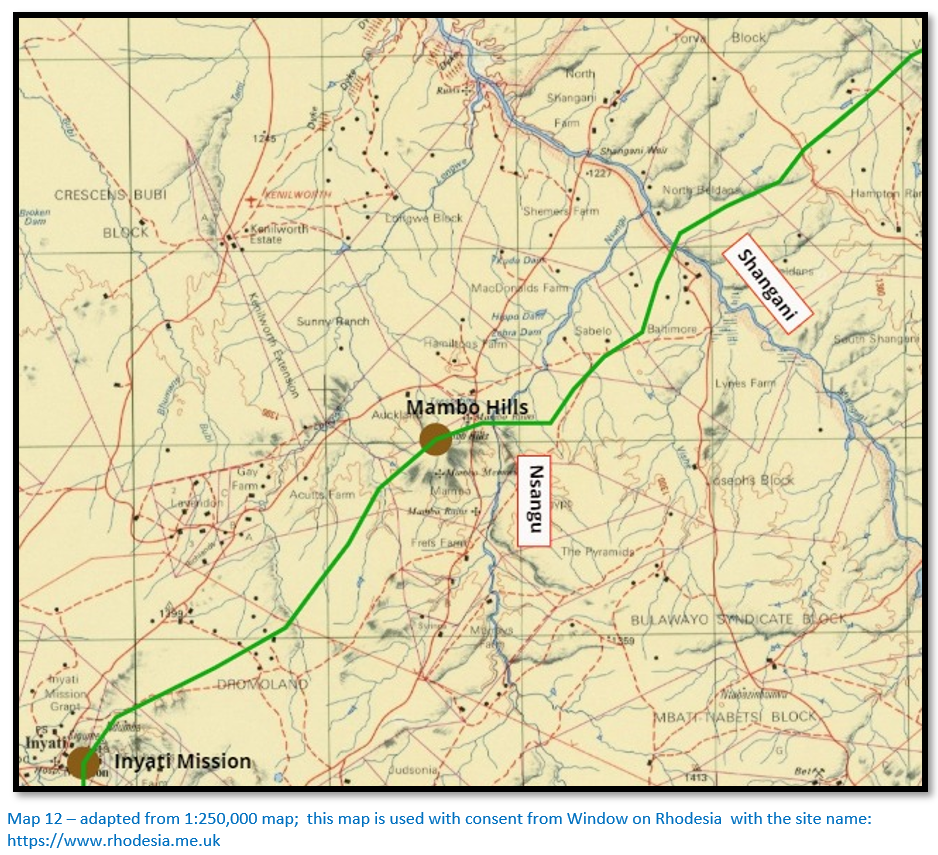

The road crossed the Longwe river drift before skirting the northern edge of the Mambo Hills and going north-east across the Nsangu river and then the Shangani river. Water was limited in the fifteen kms between Inyati and the Longwe river but streams were plentiful in the vicinity of the Mambo Hills. The rivers were the best milestones for travellers who measured the progress in terms of days’ travel rather than distances and their names were known to the drivers and herders.

The Intembin was the last of the amaNdebele kraals to be passed and the Shangani river, the largest river, was for most of the year dry but the deep sand of the riverbed proved a major obstacle for the ox-wagons.

Baines reported that Nelson had found several large quartz reefs which in his opinion might be gold bearing. “He [Nelson] washed gravel and sand in the Changani and M’Nyami rivers and readily found several specks of gold in every part proving that considerable quantities of fine gold had been washed down from the upper parts of the rivers.” [xxix]

Shangani river to Ngwenya

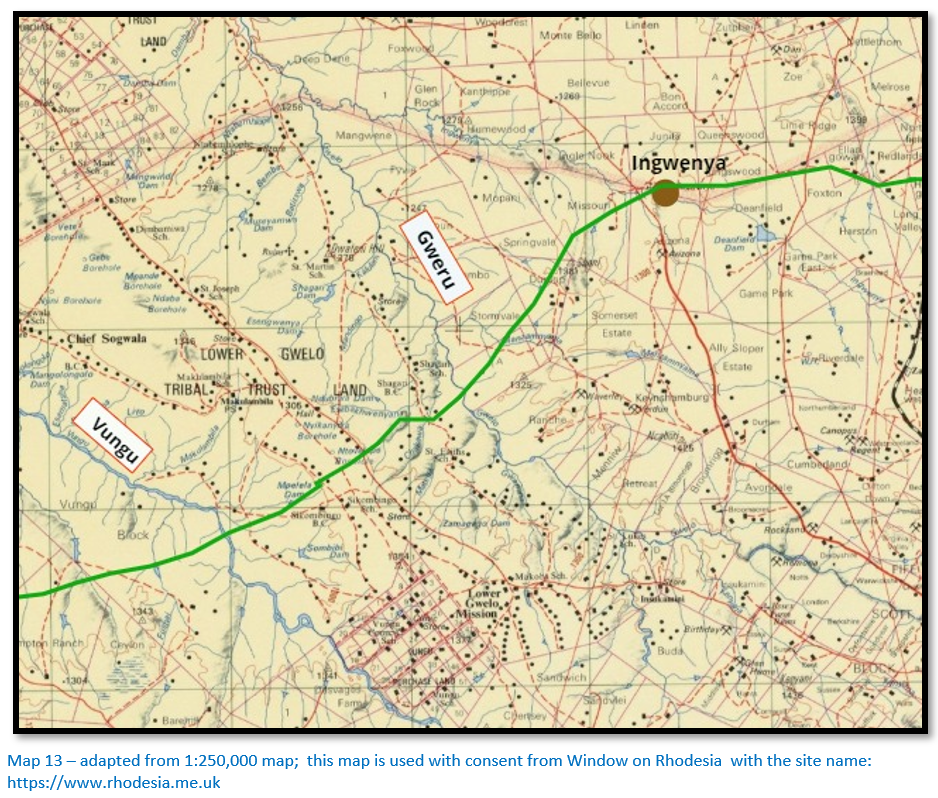

The Vungu river 75 metres wide was 21 kms (13 miles) beyond the Shangani and usually had pools of water fringed with reeds – some 6 kms upstream were deeper pools that sheltered hippos.

The 21 kms (13 miles) journey to the Gwelo, now Gweru river involved a long pull over thickly wooded red-sand and then a long descent to the Gweru river drift which was 8 kms (5 miles) above its junction with the Ngwenya river. The Gweru river 110 metres wide between its banks usually had at least a trickle of water even in the worst of the dry season.

The Ngwenya (crocodile) river was a further 7 kms (4.5 miles) and several small Mashona kraals were visible from where vegetables could be bartered. The road kept clear of the tsetse-fly belt which began at varying distances of sixteen to eighty kms from the wagon road and at the Ngwenya river travellers noted that the road went east to stay out of the tsetse-fly belt; travelling in darkness and the early morning was a common practice for many travellers that meant that the oxen became less fatigued and the tsetse-fly were believed to be active only during daylight hours.

Baines wrote: “On the 6 August 1869 Mr Nelson and I with one wagon trekked northward across country with wild hills composed of immense blocks of granite on either side. We struck the Hunter’s Road west of the Umbanga river and hills and met Mr Samuel Edwards coming out to fetch supplies for Sir John Swinburne who was in advance of us. We held onto the eastward, turning gradually more north and crossed the Um Vung, the U’Gwelo, the Gwailo and the Ingwainya or Crocodile river and taking a road which carried us too far north, had to turn south-east again and join the main one at the Quaequae river, near which we found extensive slate and schistous rocks striking north by west and south by east with numerous quartz reefs, some of which Mr Nelson found to be hold bearing. The country was park-like and beautiful, the graceful matchabela which in its young leaf presents a rich yet delicate crimson tint changing by various graduations into green as its foliage is matured; the leghondi which buds forth in golden yellow and the mimosa, acacias, aloes and occasional euphorbias added an ever-varying charm to the scene; while the higher lands were adorned with large white flowering proteas and other plants suited to their altitude.”[xxx]

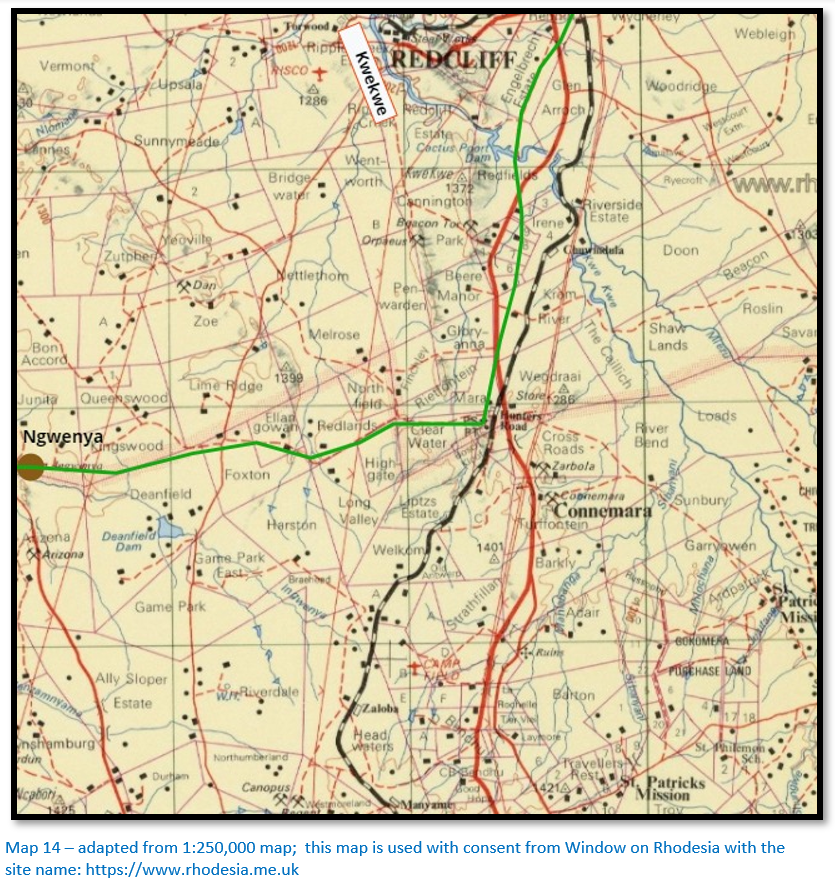

Ngwenya to Kwekwe river

16 kms (10 miles) after the Ngwenya the road crossed the headwaters of the Jumani river and then over open country before passing through a wooded pass in a line of foothills and turning north to cross the Que Que, now Kwekwe river. The river was perennial, its steep banks and stony bed made it difficult to cross and was recorded as flowing strongly even in May to August. Tabler says most travellers caught the use of the repeated syllable and used their own method of writing it. Various versions included QuaeQuae, Inquinquince, Hwahwa, Sekhoiwhoi, Ukwekwe and Sewhuewhue.

Thomas Baines cut 13 kms (8 miles) off the Hunter’s Road in 1869 - 70 by using a shorter route between the Gwelo and Que Que drifts, but the cut-off was not used much until after 1880 when the tsetse-fly spread up the Jumani river and forced travellers further south.

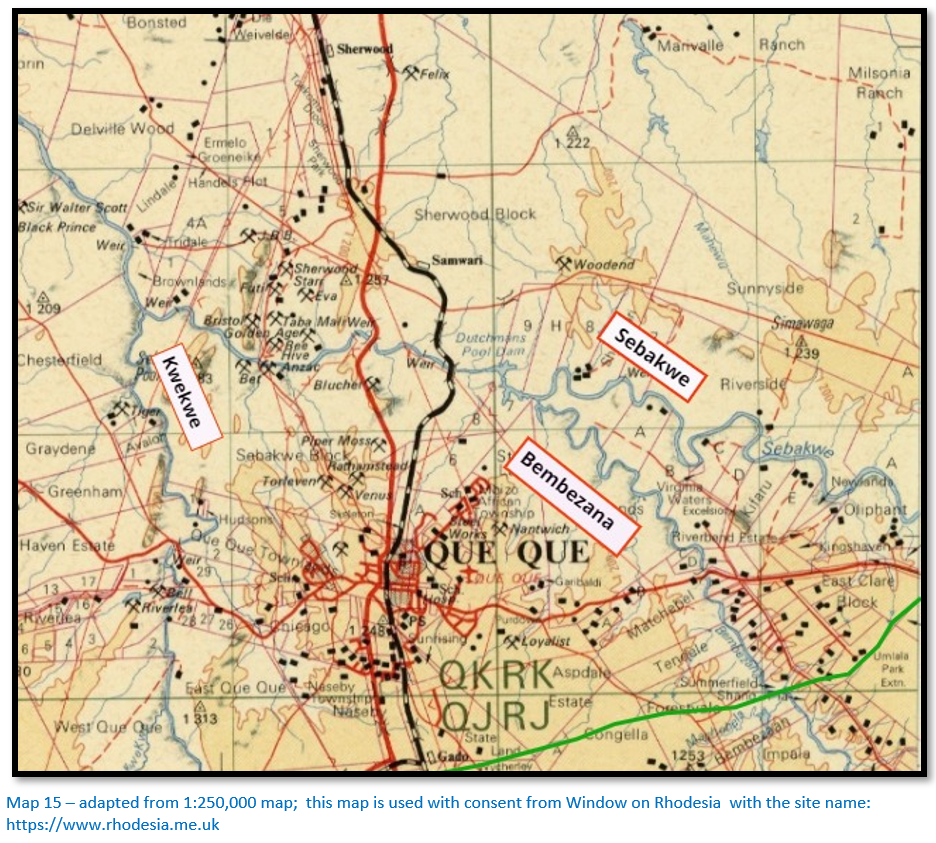

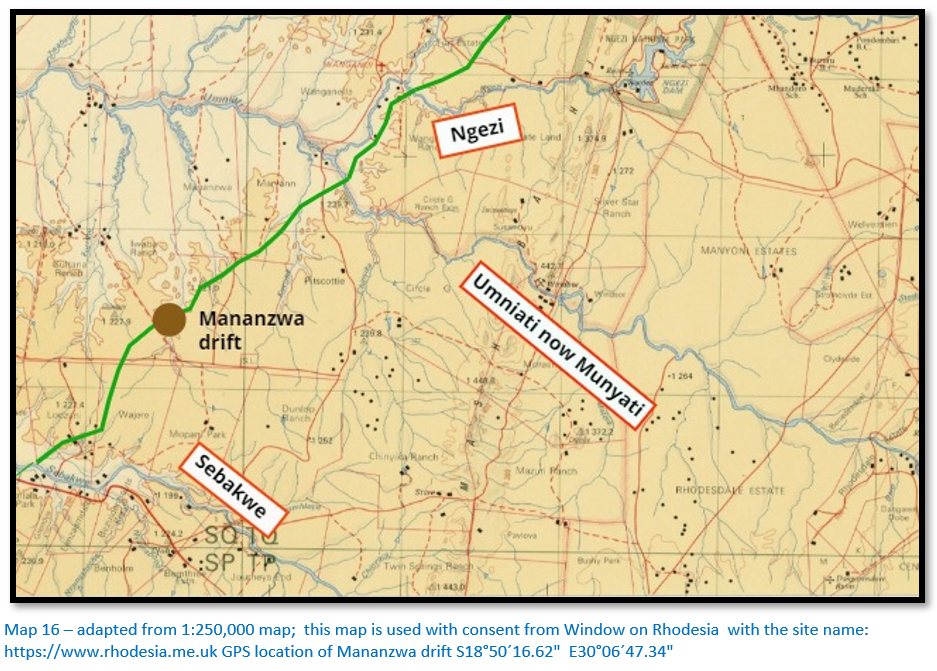

Kwekwe river to Sebakwe river

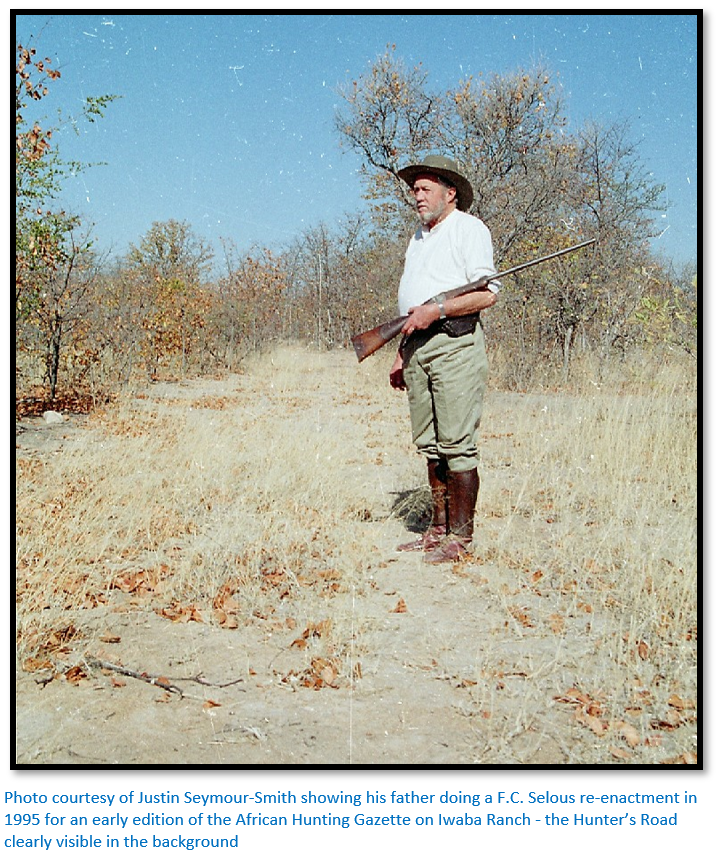

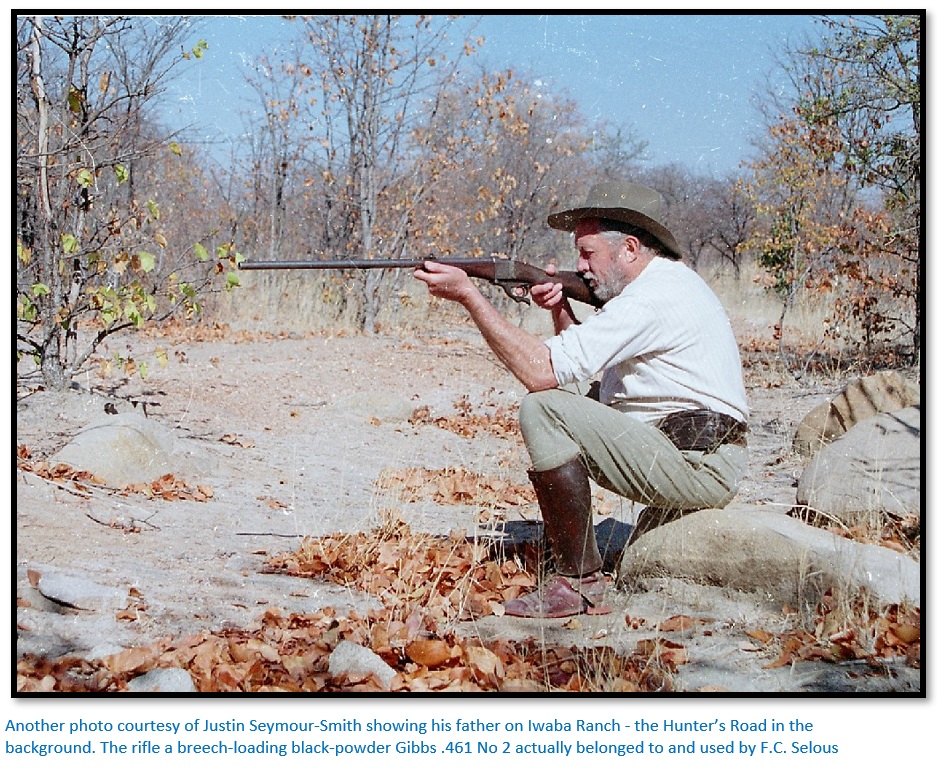

This from Justin Seymour-Smith whose family lived on Iwaba Ranch just north of the Sebakwe river:

“We must remember when thinking about the route of the Hunter’s Road that they were looking for the easiest route for the ox drawn waggons – avoiding too many river crossings, thick woodlands, black cotton soils and soft sand.

My guess is the Hunter’s Road went from the Kwekwe river crossing swinging east towards Gado siding – roughly following the present road to Cactus Poort from the main road to avoid the heavy clay soils that stretch up to the Redcliff turnoff - roughly along the railway line to the Gado area. From the Gado area just north of east towards the Bembezaan missing the small river that the Mvuma Rd crosses near the Igogo Rd junction. From the Bembezaan to the Sebakwe drift would have been fairly easy going.

The country would have been heavily wooded at that time prior to the development of all the gold mines. None of the early explorer mention any human settlement in all that area so one has to assume their livestock was at risk to tsetse fly north of the present day Hunter’s Road area – the range of the fly governed by the range of sufficient wildlife to support it.”

The Bembezaan drift was 22 kms (13.5 miles) north-east of the Kwekwe river and reached after crossing the Mlexwe, a small tributary of the Kwekwe river and crossing the pass of a small range of hills running north-south and into a wide level valley in which the Bembezaan flowed. The river usually had water; recorded as 60 cms and 23 metres wide in July 1866 with the river-bed covered in mud and stones and fringed by reeds and much frequented by buffalo.

The Sebakwe river was a further 8 kms ( 5 miles) beyond the Bembezaan was considered by most travellers to be the finest stream so far encountered and was forded at a small island. In July its wide bed was knee-deep with clear water though it was dry by October. Buffalo were abundant and they attracted lion, but most feared were the tsetse-fly that existed a short way downstream.

Justin Seymour-Smith sent me this quote[xxxi] from Selous: “In the afternoon we trekked on to the Sebakwe river, which is only about eight miles distant from the Bembees, and into which it empties itself a few miles below the drift. At daylight on September 5, we crossed the Sebakwe, and after a four hours’ trek reached a gully with some waterholes in it. In the evening, after in spanning I rode on ahead of the waggons and shot a tsessebe antelope.”

The Hartley party crossed the Bembezaan and Que Que rivers on 21 July 1866. Wilkinson on his only trip to Mashonaland was favourably impressed and reported the river banks lined with “crystals” and other minerals. They forded the Sebakwe river on the 24 July and continued on to the Umniati, now the Munyati where they shot some elephant and then rode on to the Ngezi river.

Baines wrote: “We crossed the Bembesi River and the Sebaque near the junction of which eight or ten miles north many apparently rich quartz reefs exist which were subsequently visited by Mr Nelson and myself. Mr Nelson tried the river and found a trace of gold and I remarked galena in several specimens of the quartz.”

Sebakwe river to Ngezi river

Justin Seymour Smith writes: “The Hunter’s Road was still visible in places on our old property, Iwaba Ranch up until we left in 2006. The early aerial photographs done in the late ‘50s showed it clearly in places if you knew where to look.”

Justin wrote out this Baines[xxxii] extract: “Hitherto the chief features of the country had been granite ; but to the north-west of our course greenstone schist was found, and beyond that a dark slate formation, striking north and south, and upright enough to enclose the stream between high bluffs. Mr Nelson found alluvial gold in two places in the river ; but it was very fine, and not enough to warrant him in calling it payable. We observed the first palm-tree at Sebaque. Here the country is chiefly fine-grained granite, intersected by green stone. On our right, or south-east, appear the ridges of the Thaba Euzimba, and the other highlands, forming the watershed between the Zambesian tributaries we were daily crossing, and between those of the Limpopo and Sabea, flowing from their south and eastern slopes.

The drift of the Munyati, or Buffalo, was guarded, as it were, by castellated granite hills, among which a small baobab or two, and the beautiful coral-blossomed erithrina kaffra, mingled with the acacias and mimosa, while cranes and waterfowl waded on the sandy beaches, or sported in the pools, and the hippopotamus and crocodile occupied the deeper reaches below. The Umgesi [Ngezi] a few miles onward was a bleak unsheltered mountain river rushing and babbling over accumulated rocks and stones, clear and cols as we experienced when we waded knee-deep across it.”

Justin sent me this quote[xxxiii] from Selous: “In December I returned to Matabililand in company with Mr. H.C. Collison, Cornelis van Rooyen, and Mr. James Dawson of Bulawayo, who had come to Mashunaland with an empty waggon in order to help me out with the large number of natural history specimens I had collected, which amounted altogether to more than a load for one waggon. I remember one incident of our return journey, which I think is worth relating.

One night we had outspanned at the head of a lovely grassy glade, between the Umniati and Sebakwi rivers, down the centre of which ran a nice little stream of water. Just at daylight the next morning the cattle were all unloosed to get a bit of feed before being inspanned for the morning’s trek, and soon spread out over the open valley which lay in front of our bivouac. I was drinking a cup of coffee, seated in the front part of my own waggon, when I saw a fine sable antelope bull come out of the forest that skirted the open ground and advance towards the cattle, which he kept examining enquiringly, standing still for a few seconds at a time and then coming slowly forwards again. Before long he had come quite close up to some of the foremost oxen and was then not more than one hundred and fifty yards or so from Van Rooyen’s waggon, which was some distance in advance of mine. My friend had all this time been watching the sable antelope as well as I, and at this juncture he fired at and wounded it, shooting from the inside of his waggon. Directly the shot was fired every dog rushed out from beneath the particular waggon to which he or she belonged, and the whole motley pack, about twenty in number, were soon streaming out down the valley. The foremost dogs soon caught sight of the sable antelope, which, badly wounded by Van Rooyen’s bullet, was making off slowly towards the stream which ran down the centre of the open ground. As it disappeared down the steep bank the foremost dogs were almost up to it. Van Rooyen, Dawson, and myself were now running as hard as we could to call the pack off and dispatch the wounded antelope before any of our valuable dogs were killed; for we knew from experience what havoc a wounded sable antelope can make amongst a pack with its long curved horns. Just as we were nearing the water two of my own dogs came howling up the bank, both badly wounded, and the loud barking of the rest of the pack, coupled with the defiant snorts of the sable antelope, which proceeded from the bed of the stream, let us know that the brave beast was still making a gallant fight and doing his utmost to sell his life dearly. A moment later we dispatched him with two bullets through the head and neck, and not a moment too soon. Four of our best dogs lay dead around their quarry, one of which, a kind of mongrel deer-hound, Van Rooyen would not have parted with at any price. Besides the four that were killed outright, four more were badly wounded, one of which subsequently died. My old bitch Ruby had one more very narrow escape. She had been struck right through the throat by the sharp horn of the sable antelope, which, however, had only pierced through between the skin and the windpipe. She must, I fancy, have been swung up into the air, and then twisted off with such violence that the skin had torn; so that a great piece of it as large as the palm of my hand hung down under her jaw. This piece of loose skin, however, I sewed in its place again, and the wound soon healed up.”

The drift across the Umniati was 800 metres (0.5 mile) above the Umniati / Ngezi river confluence with steep banks and hippos in many of its deep pools.

The Umniati flows around the southern end of the Mwenezi Hills[xxxiv] to the east; the Ngezi flows around the northern end with its headwaters near Featherstone. From the Umniati the Ngezi river was 6 kms (4 miles) distant – the Ngezi ran swift and clear all year round with long quiet pools that concealed both hippos and crocodiles.

Justin sent another quote[xxxv] by Selous on the Munyati river: “Laer always was a most lucky boy for coming across lions. I remember in 1882 I sent him out to Matabililand, in the early part of the hunting season, with some of the skins of the antelopes I had already preserved, as I saw I was getting so many that I should never have been able to have carried them all at once, on y one wagon, at the end of the hunting season. Laer travelled with the small wagon I had made by taking the wheels off my big buck wagon and then putting in a short lang wagen. He only had a double-barrelled shot gun with him with which to shoot guinea-fowls along the road, as I had no spare rifle to lend him. One night he was camped at the Umniati river, the ten oxen being tied, two by two, to the yokes as usual. Laer and the two boys who were with him were lying inside a fence which they had built behind them, and which ran out at right angles from the hind wheel of the wagon. A large fire was burning at their feet, which cast a good light for some distance round it. Suddenly Laer heard a commotion amongst the cattle, and jumping up simultaneously with the two Kafir boys, they all saw a large lion emerge swiftly from the gloom of the night, advance rapidly, and seize one of the two oxen that were standing just in front of the two tied to the disselboom. The grim beast stood in the full light of the fire, with one paw over the shoulder of the ox, and the other holding the poor animal by the muzzle, the lion’s hind feet being planted firmly on the ground all the time. Laer then very pluckily fired a charge of shot into him at less than ten yards’ distance. He told me, in relating the adventure, that the lion, on being hit, gave a loud roar, and instantly quitting the ox, bounded off into the darkness, and did not return. The ox that had been attacked had to be driven loose from the Umniati river to Matabililand, and eventually died from the effect of the bites he had received in the back of the neck.”

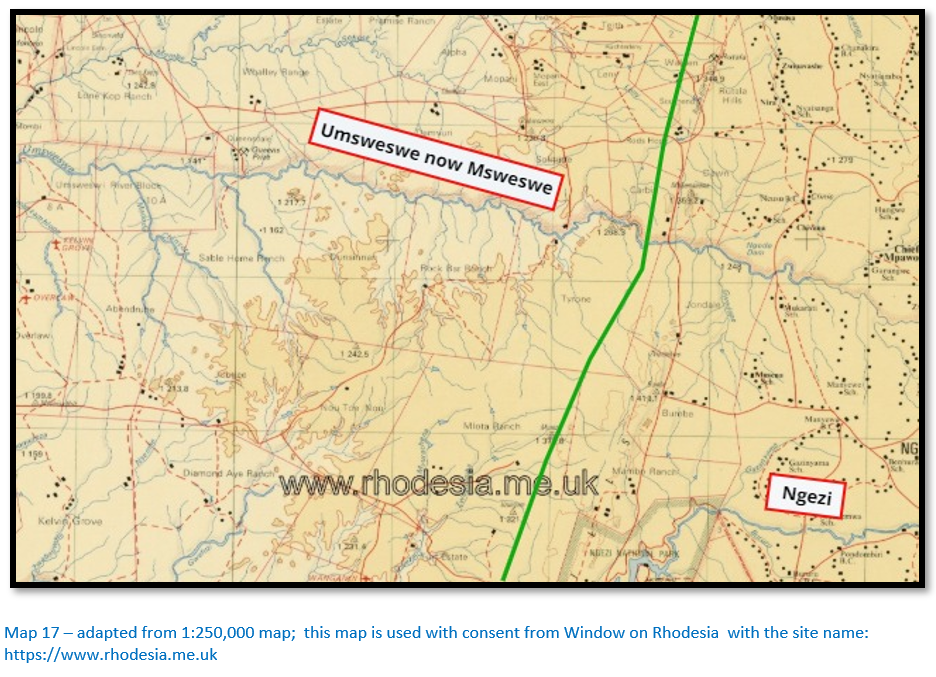

Ngezi to Umsweswe river

The next trek of 21 kms (13 miles) took the ox-wagons to the drift on the Umsweswe river that travellers described as a beautiful small stream of clean water flowing over sand and rocks. Trees lined the banks and at the drift the river channel divided into two after a very steep approach down the southern bank.

By 31 July the Hartley party were over the Umsweswe, now Msweswe where they camped. Henry Hartley told marvellous hunting tales – nobody could tell bigger or better ones, though they all thought Christian Harmse came in a good second for story-telling. For two weeks they made short hunting trips from their stand place. Some men remained in camp whilst the others searched the surrounding countryside for wildlife.

Finaughty left for Matabeleland on 7 August. He was so successful at hunting that the Hartley’s became jealous and made him feel uncomfortable. The hunting tactics of the Hartley’s were criticised by Finaughty who stated that when they found an elephant kept together and fired at the same animal until it fell; so elephants were killed one at a time. This resulted in a smaller bag than if each hunted independently although the “Oud Baas” is still credited with over 1,000 elephants in his lifetime. Since he had left his wagon at Inyati he had to leave his ivory for the others to bring out and on his way back to Inyati killed eight more cow elephants and had to ask a man also returning to let his servants carry the tusks.

Those remaining at the Umsweswe had some difficulties with Inyoka who exacted tribute from their Mashona guides. The oxen were inspanned on 13 August and the combined party moved on to the south bank of the Umfuli, now Mupfure river, an easy trek of just a day and a half following native paths.

Baines writes: “At Umgesana [Gwazana?] we found the brothers Jennings[xxxvi] with Mr Saunders[xxxvii] and Mr Gilliewie[xxxviii] outspanned by a clump of trees and dwarf palms and received valuable information from them. And at the drift of the Umzwezwie (beautifully overshadowed by bold groups of forest trees) Mr Nelson found gold among the stones and sand in the broad bed which only the flooded river could fill.”[xxxix]

Umsweswe to Hartley Hills

Baines continues: “The hills[xl] of the watershed upon our right sweeping round like a vast amphitheatre from east to north forced us still more in that direction and camping in a soft wood grove near Zizena or Mud Spruit we lost an ox from weakness and exhaustion and here, saddling up my horse – kept only for great emergencies – I rode on to overtake Mr Hartley. Crossing the Zinbindasi [Chirundazi] rivulet and the broad and sandy Um Vuli [Umfuli now Mupfure] river I reached the Sarua [Serui] and halted for the night. I observed the glare upon the clouds from fires in the direction of Sir John Swinburne’s camp, three or four miles south west of me [at Hartley Hills] Next day I crossed much quartz ore and well-wooded country, intersected by several rivulets and during the forenoon reached the wagons of Mr Hartley, the brothers Wood[xli] and Mr McMaster.[xlii] The hunters were absent, but Mrs McMaster and the other ladies welcomed me and spread upon the skin that did duty for a breakfast table, so may little delicacies created from the rough materials at their command that I seemed to have fallen into the very lap of luxury. A train of Matabili and Mashonas arrived loaded with ivory and elephant’s flesh and as the camp was shortly to be moved I rode back early next morning to hasten on the wagon. I met it at the Sarua river in which Nelson found a little gold.”[xliii]

The road travelled on the western side of the Rutala Hills before swinging east to the Chirundazi stream and following it down on its western side to the confluence with the Umfuli, now Mupfure river. Tabler states the first drift was 0.5 mile west of the confluence – the level of the river is now artificially raised by a series of weirs, but 600 metres west is a small island still visible and drifts were often sited where a river divided into two channels. Thomas Baines named this Hartley’s drift and his son is buried somewhere near the Chirundazi confluence although all trace of his grave has been lost. [See the article The search for Willie Hartley’s grave under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Typically as on the Ngwenya to Kwekwe river stretch of the Hunter’s Road (Map 14) Thomas Baines disregarded custom and cut a new section of road that avoided the turn to the Chirundazi stream and went straight on to the Umfuli. This shortened the distance and became the preferred route with the new Umfuli drift a mile further downstream. There is a small island above the water 1.3 kms downstream and this may have been where the drift crossed the river.

At both drifts there were old campsites sheltering under the shade of sausage trees (Kigelia Africana) and marked by stockades of thorns to protect the oxen and horses from lion which were common in the area. From the northern bank of the Umfuli the Hunter’s Road led off in a north-westerly direction for 5 kms to reach the fabled Hartley Hills – the scene that Thomas Baines painted of the elephant that Henry Hartley shot and fell dead on a pre-European gold working. [See the article Thomas Baines and the Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The Hartley Hills are marked by a short string of kopjes stretching south for a kilometre from the drift over the Chimbo stream which shortly after joins the Umfuli river. On the north bank of the Chimbo stream was Constitution Hill that Thomas Leask advised his friends to climb each day to quicken their recovery from malaria fever! The north bank of the Mupfure was generally clear of tsetse-fly, but malaria was prevalent.

Vegetables could be bartered locally from the Mashona. Both Chief Lomagundi to the north-east and Chief Umtigeza recognised amaNdebele sovereignty at the time and paid tribute. The amaNdebele raided east of the Mupfure river from time to time although it was often recognised as the physical boundary line.

The Hartley party found ruined kraals and gardens and followed a Mashona man to a kopje whose natural defences had been augmented with dry-stone walling. The fears of the inhabitants who had been subjected to an amaNdebele raid not long before were calmed when they bought grain and spent the night at the kraal. One of the Mashona was hired as a gun-bearer and to find elephant. Trips after elephant were carried out on horseback, the wagons being left at the Umfuli and usually lasted four or five days. They rode into the valley of the Hunyani river but did not reach it on this occasion.

Because they spotted tsetse-fly at the Umfuli they pulled the wagons back towards the Ngezi river and the next day Phillips left to return to Matabeleland. After some days of rest trekking began again on the 27 August towards the south-east and the Mwenezi range and to the headwaters of the Umsweswe river. In their search for elephant they reached the source of one of the tributaries of the Ngezi.

The wagons started on the return journey on 8 September taking a path that intersected with the Hunter’s Road. They crossed the Bembezaan on 19 September reaching Inyati in ten days and were at Mzilikazi’s kraal by 3 October 1866. Most of their horses died of dikkop, an African horse disease, but these losses were offset by the twenty-eight elephant killed by the Hartley party and the thirty elephant shot by the others, including Finaughty.

Hartley reached his home Thorndale farm by 10 January 1867 and Leask reached Potchefstroom in early February. Karl Mauch had to be very circumspect in his search for gold as Inyoka was extremely suspicious. Mauch possessed a pocket compass but did not have a sextant and did little mapping. His peculiarities were talked about by hunters long after he left Africa, but Hartley gave him what help he could and paid a Mashona named Makhombo to point out old gold-workings at the Sebakwe and Bembezaan rivers where Mauch spotted visible gold in the quartz seams. He was inconspicuous in his searches though; Leask only mentions Mauch twice in his diary and once was when he was forced by five lions to spend the night in a tree.

From Hartley Hills to the Hunyani now Manyame river

The Hunter’s Road ended at the Chimbo stream drift but a trail continued north-west for 8 kms (5 miles) and crossed an easy drift over the shallow but swiftly flowing Serui river.[xliv] Another 21 kms (13 miles) north-west the road crossed the Biri (rock rabbit) river where the road turned north for 14 kms (8.5 miles) to the Msengezi river which had a steep sandy drift.

The Hunyani now Manyame[xlv] was reached 19 kms (12 miles) in a north easterly direction over wooded and undulating grounds near to present-day Kutama Mission and College and below the junction of the Gwebi and Manyame rivers. Between the Mupfure and the Manyame travellers took the trail on horseback and left their ox-wagons parked in the shade of the Msasa trees at Hartley Hills where there was good grass and water for the oxen to recover.

Acknowledgements

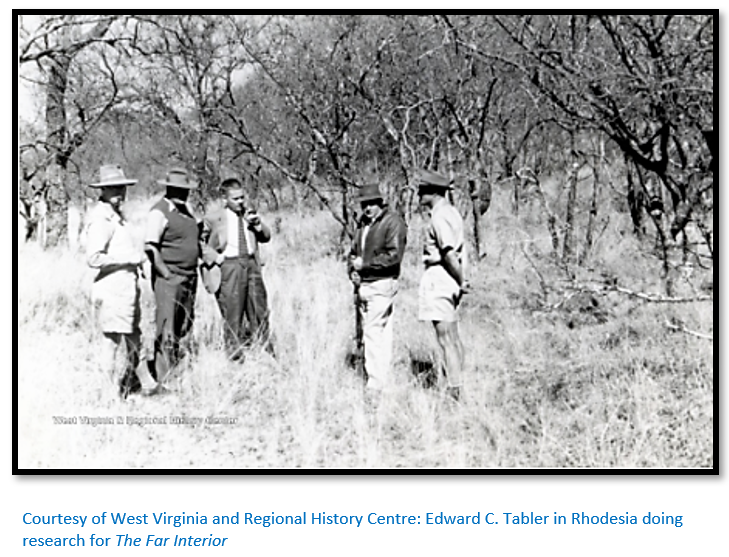

Much of the narrative for this article comes from the doyen of pre-occupation history - Edward C. Tabler’s The Far Interior; a classic account of pioneering in the Matabele and Mashona countries during the period 1847 – 1879 and the premier author of this period. His account is supplemented with the accounts by Robert Moffat and Sam Edwards to Gubulawayo and then by Thomas Leask’s account of the large hunting party that travelled under Henry Hartley to Mashonaland.

For The Far Interior Tabler relied on numerous historical sources. For example for the section from Makobi’s kraal where Manyami was located (Map 6) he used descriptions from Moffat (1854) Mackenzie (1863) Leask (1866) M’intosh (1869) Baines (1869, 1870, 1871) Selous (1872) Oates (1873) Anderson (1877) Rudd (1888) Mathers (1891) and Decle (1892) but of all of them he considered Thomas Baines’ surveys and measurements the most accurate; Baines was an excellent cartographer as well and his maps were the best for another 30 years.

For the 1:250,000 maps I am indebted for permission to download them with consent from Window on Rhodesia with the site name: https://www.rhodesia.me.uk which is authored by Colin Weyer.

Justin Seymour-Smith whose family lived on Iwaba Ranch north of the Sebakwe river was a great help in directing me towards the likely route of the Hunter’s Road from the Kwekwe river and across the Sebakwe as far as the Munyati river and kindly copied out the quotes in the article from F.C. Selous and T. Baines and let me use his family photographs. Thanks Justin!

References

J. Knight. Shoshong; a short history. Online pdf. Kwangu, Gaborone, Botswana. May 2014

E.C. Tabler. The Far Interior; Chronicles of pioneering in the Matabele and Mashona countries, 1847 – 1879. A.A. Balkema, Cape Town, 1955

Frank Oates. Matabeleland and the Victoria Falls; the Letters and Journals of Frank Oates, 1873-1875

R. Sampson. White Induna; George Westbeech and the Barotse People. Xlibris Corporation, 2008

T. Baines. The Gold Regions of South Eastern Africa. Books of Rhodesia Volume 1, Bulawayo, 1968

F.C. Selous. A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa, London, Richard Bentley & Son, 1881

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South-East Africa, London, Rowland Ward and Co, 1885

[i] It was believed by the amaNdebele that the liver, heart and gall bladder of reptiles could be used by sorcerers to kill humans at a distance

[ii] The Far Interior P164

[iii] Thomas Baines measured this distance in 1869

[iv] Walvis Bay to Lake Ngami was measured by Baines and Chapman with a trocheameter

[v] Roots web re Thomas Leask

[vi] Wikipedia. Shoshong

[vii] Sunday Standard Botswana. 10 June 2019. The Elephants of the Khama Dynasty article by Richard Moleofe

[viii] Shoshong, a short history

[ix] Shoshong, a short history

[x] The Far Interior P20

[xi] Ibid P213

[xii] Tabler states that Moffat, Mackenzie, Baines, Holub and Decle state that the Maklautsi river was the Bamangwato – amaNdebele border, but Moffat and Oates declared the Shashe river to be the border. Tabler thinks the amaNdebele ruled as far as the Shashi but by their 1863 raid on Shoshong they effectively extended their rule to the Maklautsi river.

[xiii] G.S. Quick. Early European involvement in the Tati District. Botswana Notes and Records. Vol. 33 (2001) Botswana Society.

[xiv] Botswana Daily News. Old Tati; Bechuanaland’s ancient commercial centre by P. Kedidimetse on 25.10.2017