Home >

Mashonaland West >

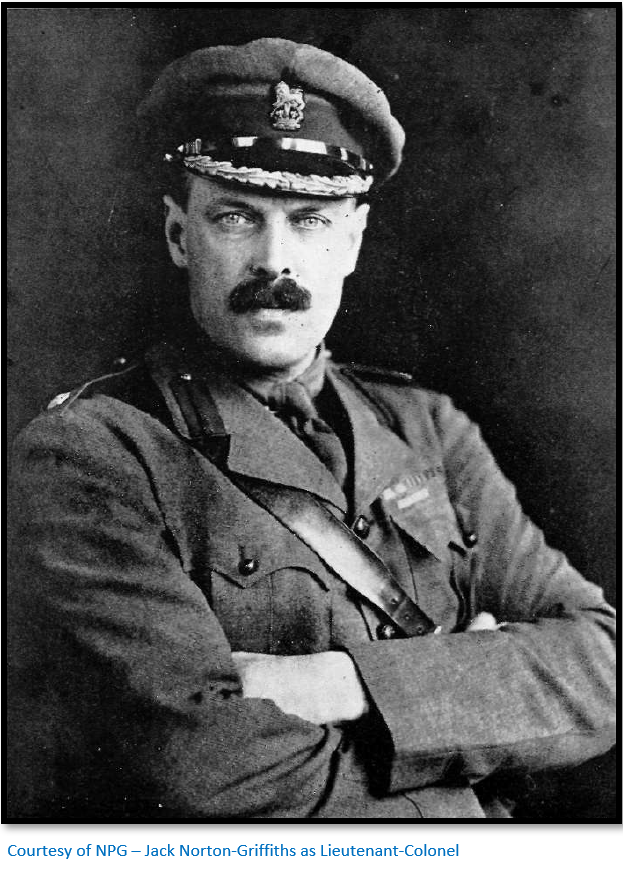

First Baronet Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths, KCB, DSO – the Great War engineer whose mine explosions at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917 were heard 240 kms away in London

First Baronet Lieutenant-Colonel Sir John Norton-Griffiths, KCB, DSO – the Great War engineer whose mine explosions at Messines Ridge on 7 June 1917 were heard 240 kms away in London

Sir John Norton-Griffiths, First Baronet, KCB, DSO (13 July 1871 – 27 September 1930) was an engineer, British Army officer during the Second Boer War and the First World War and a Member of Parliament. A colourful figure in his day, known as "Empire Jack" or “Hell-fire Jack” he was also the grandfather of Jeremy Thorpe, a leading British politician.

He was featured in a good article in Rhodesiana Publication No 20 of July 1969 by Dick Hobson and this piece aims to expand on the man with additional information. Dick Hobson’s article provides the perfect introduction: “Sir John Norton-Griffiths, Bt., KCB, DSO, was a man remarkable in both character and achievement. Without formal qualification as an engineer, he yet carried out vast projects of construction and destruction which ranged in time and place from the building of the Benguela Railway to the mining of Messines Ridge. His abundant courage, self-confidence and energy were the typical resources of the pioneer and the purpose of the present note is briefly to recall the part that Rhodesia played in the shaping of these qualities, the achievements they made possible and the failures to which they contributed.”

Tony Bridgland, author of Tunnel-master and Arsonist of the Great War: The Norton-Griffiths Story says: "He was an entrepreneur, a go-getter - not a glory seeker, but the type of man who didn't sit on his hands and liked to get things done."

I have quoted his diary of events in 1896 verbatim as they were written…some of the words are understandably not acceptable today but were in common usage at the time of writing.

Early life

John Norton-Griffiths was born John Griffiths in Somerset on 13 July 1871, but was always called Jack and the only son of four to make it into adulthood. He was the son of John Griffiths (1825-1899), a building contractor, who at the time of his son's birth was Clerk of Works at St Audries Manor Estate, West Quantoxhead, but later came to London. As a young lad he showed no interest in books or study and was always getting into trouble being mostly interested in sports or boating and being with his friends; even at a young age he made good friends and was entertaining company. At 16 he threw up a job as trainee draughtsman his father had arranged and enlisted as a trooper with the Royal Horse Guards.

He did well at riding and won an award, but after a year was persuaded by Percy Kimber, a friend and son of the MP for Wandsworth, who owned a firm called the Natal Land and Colonisation Company Ltd to try sheep farming in Natal. Ironically Jack himself would be MP for Wandsworth himself from 1918 to 1924! If successful, after a year he would be set up with fifty acres of his own and a £150 loan to start farming. Cecil Rhodes had previously joined the same scheme and worked on his brother Herbert’s farm at Umkomaas growing cotton. So in 1888 Jack and Percy left for South Africa.[i]

He spent a short period farming and learning the habits and views of Natal colonists before once again, true to his habit, threw up his job and left for the gold mining camp of Johannesburg which had been in existence just two years. Gold-mining on the Rand required large amounts of machinery to process the low-value ores and therefore was soon dominated by the Randlords who had access to capital. Thanks to his ability to make friends easily Jack made friends with a Captain Maynard, a member of the Diggers committee and was hired as a miner at the Crown Reef gold mine.

Working on the Johannesburg gold mines and the Jameson Raid

In 1889 he began to gain experience about tunnelling, stoping, jack-hammers and the use of dynamite for the gold extraction process; by 1894 and 24 years old, he had been promoted to sub-manager at Tharsis Gold Mining Company at Johannesburg. Somehow he became involved in a minor way with the botched Jameson Raid into the Transvaal which was launched on 29 December 1895 from Pitsani in modern day Botswana. By 3 January 1896 Jameson and his raiders were all imprisoned at Pretoria. The details of Jack’s involvement with the attempted uprising are unknown, but within 24 hours he was escorted out of the Transvaal by two of Paul Kruger’s Zarps (Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek Politie) as far as Volksrust on the border with Natal.

Military career in Africa

Matabele and Mashona Rebellion of 1896

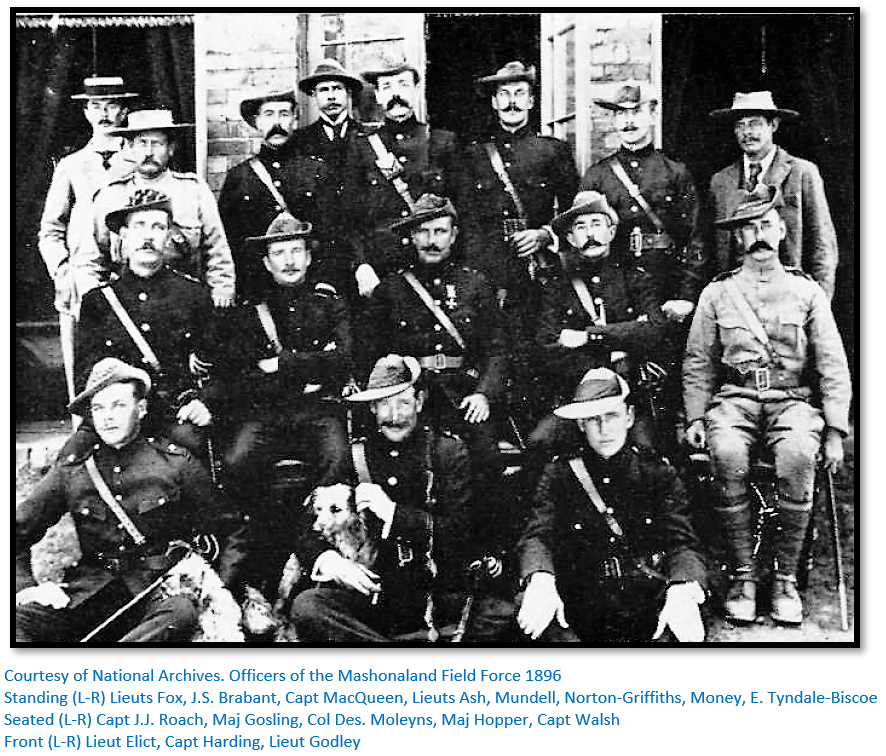

Jack boarded the Arab at Durban; as fate would have it Lieut-Colonel Edwin Alderson was aboard with a contingent of mounted infantry and their horses; he was about to assume command of the Mashonaland Field Force following the outbreak of the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga. During the three-day voyage to Beira Alderson agreed to introduce Jack to Wilfred Honey, the Standard Bank’s first accountant in Mashonaland who had formed Honey’s Scouts. Once they reached Beira Jack was signed on to Honey’s Scouts as a sergeant earning ten shillings per day plus uniform and rations.

In July 1896 the two-foot narrow-gauge Beira and Mashonaland Railway began at Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point on the Pungwe river and would only be connected directly with Beira in October 1896. From Fontesvilla the railway continued over the Pungwe flats before rising steeply and encountering the steepest gradients in the Amatongas forest and continuing on to Chimoio the railhead at the time. Umtali, now Mutare was only reached by rail in early 1898 [see the article The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s Stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.co]

From Chimoio the mounted infantry and Honey’s Scouts travelled to Umtali with wagons hitched to mules, the oxen had all been killed in the rinderpest outbreak the previous year. Once Umtali was reached the going became easier but the troops needed to be on alert and Honey’s Scouts ranged ahead of the main column as advance guard to ensure the main force was not ambushed crossing the Odzi river or at the Devil’s Pass. Laagers were formed at night and on the highveld a fierce but inconclusive engagement fought with Chief Makoni at his stronghold [see the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com / also Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts]

Charter and the fight at Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal[ii]

From 29 September when Jack was posted to Charter[iii] he kept a brief diary for three weeks.

29 September 1896: “Dear Mother, Nell and Annie, A wagon arrived here bringing mail from Bulawayo on its way to Salisbury. I take advantage to write. We’re laagered. No news. Waiting for the remaining part of our column before proceeding to Mashayamombe’s. Frightfully monotonous. Reading when we can get books to read. They are still fighting and having rough times at Mazoe – losing some men. A private wagon belonging to a Beyenhout [Bezuidenhout] brought some things on speck. But what a price! Whisky £2 10s a bottle. Cigarettes two shillings a packet.”

30 September 1896: “A very enjoyable evening. Sat around the campfire, took turns singing songs. I was persuaded to get up and sing, which they seemed to appreciate. There was a fight. I was referee. One man was knocked out. I’ve heard from all sides that Mashayamombe’s is a very strong place indeed. And I am afraid that some of us will rest in peace there or depart for pink clouds. I hope not.”

1 October 1896: “Another, but more private smoking concert was given over at the C laager to wish Captain Stricklin goodbye [Arthur Strickland…see the article on Fort Charter under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] he has resigned as O/C of the Charter. I thought the singing was rather poor.”

The wagons finally turned up with 14 days rations and 200 rounds for the seven-pounder gun and the force moved out of Charter heading north to Beatrice and following the Mupfure river west to Mashayamombe’s kraal. The earliest deaths of the Mashona rebellion of First Chimurenga had occurred in the vicinity of his kraal…those of some Indian traders and the two prospectors Stunt and Shell along with the Native Commissioner David Mooney on 15 June 1896.

6 October 1896: “On the 6th we outspanned about six miles from Charter. 4pm on the Gazu river. Very forested. After off-saddling, Honey and self went for a bath and discovered a lovely deep place about 200 yards long. I jumped for joy and immediately undressed for a good swim. A shout from Skeed, our guide. ‘For God’s sake look out! Crocodiles!’ I made for the bank as hard as I could and was just in time to escape the jaws of a rather small croc. Narrow escape. The rivers in these parts are full of them. Horses in at 6pm. Dinner at 7pm. Army and Navy rations. Nice bread and tea.”

7 October 1896: “Soft ground and clumps of trees, etc. We proceed to advance. On arriving at pools found 3 little holes. Two we used for horses…the other and best one was kept for drinking. This consisted of 25% mud, 15% reeds and 60% water. Anyhow this had to do as it was quite dark and we could not go on to better water. So we had to quench our thirst with this, which also had to do for cooking, but we were quite thankful for it. Lights out at 8:30. Going to sleep. Goodnight all. Reveille 4:15am tomorrow.”

8 October 1896: “The Scouts under myself left the laager half an hour before orders to find our way and whereabouts we were. The guide here was utterly useless. I sent back half section every mile to lead the column on. I came across the mule road and discovered by scouting the country that we were within 3 miles of the [Beatrice] mine. Sent back and reported this and waited until the column came up. We then proceeded to the mine and laagered. The mine was completely deserted of course. Two men (Tate and Koefoed] and a Cape boy being recently murdered here and their bodies thrown down the shaft of the mine. Four other men escaped. We saw the blood marks where the men had been murdered. Found plenty of jam, butter and a few other luxuries which the n*****s had left. Came in very handy. The quartz here was very rich, showing visible gold. The troops were highly interested, each trying to obtain a specimen. We started ahead again to find our next water and distance. Found water and good grazing 5 miles from our last outspan. On the way to this water we had to ride hard at times to miss a very big grass fire raging across the country. Getting scorched and almost burned in some places. When I reached the water, I put a sentry half a mile ahead to keep a sharp lookout as we are only about two miles from the place where the Natal troops on their previous visit here had to off-load their kit and dump their provisions to lighten their wagons so as to hasten their retreat.”

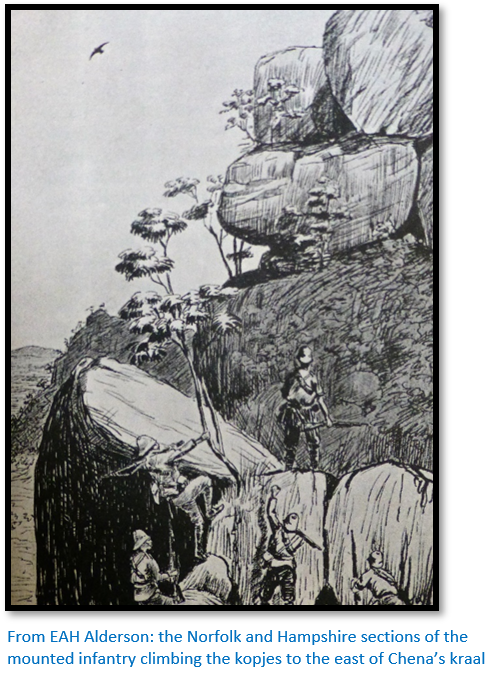

On 9 October: Major Jenner made contact with Lieut-Colonel Alderson exchanging red and white lamp flashes and planned a joint attack on Chief Mashayamombe’s kraal next day. From the north of the Mupfure river Alderson sent in sections of the Salisbury Rifles, Mounted Infantry and native contingents to clear the kopjes and burn down the kraals; the inhabitants running terrified into the nearby caves. Major Jenner with his force including Jack approached from south of the river towards Chena’s kraal.

9 October 1896: “Left laager 5:45am. Proceeded about 8 miles when Major Jenner who was riding along with me leading the column, espied a kraal in the distance. Major Jenner, myself and other scouts immediately called in as they were flanking either side of me. Also a half section galloped around the kraal to gain an idea for the best place for an attack. We then advanced, Major J and self, rushing through an opening in a strong stone wall, but alas after this [illegible] we found the n*****s had retreated to stronger place. Left here and proceeded at 2pm. At 4:20 one of the half sections of scouts flanking on my right was fired on from the kopjes. Strongly fortified. We were all proceeding across an open space towards the kopjes expecting to find n*****s. Closed my men in immediately and dismounted them, leaving 3 holding the horses. All told we were about 50 men dismounted. We then chased up side of kopje fighting hard and a goodly [illegible] fire from the enemy. We drove them out and continued chasing them across very rocky country. Very woody and full of kopjes, killing a great number. Bullets whizzing all around us.

The whole of the men divided into three distinct sections. Lieutenant Eustace was shot thru ankle and one man amongst other narrow escapes receiving a bullet right through his helmet taking off the hair on his head. But we gave them very little chance of stopping to [illegible] We then espied another kraal on a high kopje. We all advanced from different directions, pouring in deadly volleys. This we took, completely routing enemy, burning the kraal, about twenty-five big huts. Continued chore until dark, shooting and killing the whole time. This is the commencement of a range of country, nothing else but steep honeycomb kopjes and mountains full of caves. Mashayamombe’s country. Dogs, fowls, etc are being burned alive in the huts. No time to set them free. We returned to our laager after sunset very tired and sopping wet with perspiration. Had grub.

About 7:30 we saw the signal rockets of the other part of the column which has come straight from Salisbury. By the rockets we should say they were about 10 miles off – about 300 men and horses. I am too tired to give a more descriptive account of over 3 hours continual climbing rocky kopjes, fighting – hard work, I assure you. A very [illegible] Sergeant Jack with bullets whizzing all around you and they sound very peculiar. We start tomorrow at 6am to advance and attack at the same time.”

10 October 1896: “With about 70 men left laager at 6am; detailed to take kopjes each side of the drift[iv] and where the wagons had to go through and burning two kraals which had been deserted. We held the kopjes while the column passed through. It seemed as if we were entering a regular maze of kopjes and hills.

If they had been occupied by n*****s it would have been a deadly place to have entered. Of course we, the scouts, were a good way ahead and on each side of us some 200 yards out were a section of men dismounted, walking and climbing along to see if there were any n*****s. About 8:30 we came in contact with the Scouts of the main column under Colonel Alderson and some 20 minutes later met the whole column, about 400 men all told – 200 of his column were then engaged in attacking Mashayamombe’s principal kraal and caves. We laagered to give the horses and mules water and food. I could hear the firing of the attacking party who were some 600 yards away. About one o’clock we heard a tremendous report and could see a great deal of smoke, dust, etc. This turned out to be a big charge of dynamite they lowered into a cave in which the n*****s had taken refuge. They were firing from it on the troops. As far as I can ascertain they blew the cave to blazes. If so, it must have killed a good number. The men then returned to their column bringing 3 wounded men with them. We stayed where we first laagered for the whole day. I expect we shall get some more fighting tomorrow. Going to have a wash now. We have just caught two goats. The boys are killing them for dinner. A change from corned beef.”

11 October 1896: “We left laager at about 7:30am after waiting about an hour for the Col. and his column. The scouts under myself leading Jenner’s column down through the kopjes towards the drift or entrance as it were into Mashayamombe’s country. The other columns riding up and scouting the kopjes and keeping in touch with us on the road. We reached the drift without anything happening but could hear firing on the right-hand side of the road. Here the Colonel joined us and some 200 troops and when they moved off in the direction of the firing, Major J telling me to take four men and go with them, leaving the others with the guns on the drift. Waiting for orders after proceeding some half a mile down the river where all the kraals are situated. The Colonel sent a Mr Harding who knows the kraals very well and my four men and myself ahead to find the exact spot of the fighting. Myself and two men were riding through a pass between the kopjes on all sides, when rounding a kopje on the riverside (with caves and kopjes facing us from the other side of the river) we were suddenly fired upon – one bullet nearly knocking Botha from his horse, but fortunately only grazed him. Ordered all to dismount, gave Harding our three horses and gave order to return fire into the kopjes, picking holes of caves. Harding in meantime retiring with horses and we doing the same thing but firing away the whole time until we got under cover and returned to the Colonel’s column. We then marched on and attacked Mashayamombe’s kraal. Here we had a very hot time of it, a strong fire being returned. Fighting until 4pm when we returned to our laager. Several men were hit this day, one white man being shot dead. Trapped by a calf tied up at the bottom of a kopje. He thinking it was loose, went up to drive it away. By doing this, the enemy drew him under the opening of one of their caves. As soon as he arrived where the calf was, he received a bullet through the chest.” [this was Trooper J.S. Coryndon]

12 October 1896: “This was a day of hard fighting. Marching from laager at 7:30 we no sooner arrived within 300 yards of the same kopje when a heavy fire was opened on us. The column took up position the same as yesterday with the men on a kopje facing the enemy, the river running in between. Captain McMahon with the Irish column attacked on the right face, got down into the open. Here the fire was so strong that he and his men had to take cover behind some small rocks dotting up here and there out of the ground. For five hours he could neither advance nor retreat. As soon as any of the men showed themselves to the enemy, they were either killed or seriously wounded, one man receiving a bullet right through his helmet. The men brought the Maxim and two seven-pounders into action, pouring in a continuous fire. The Irish column were enabled to get up to our kopje and assist with keeping up the fire from there. After this, Major Jenner and his men and scouts under myself were ordered to work around by the left face and attack the rear of the enemy’s position. This was rather a dangerous task. We managed to cross the river and when on the other side we discovered we should have to gallop between two of the enemy’s kopjes, about a quarter mile in order to get to the back. So when we were all ready we spurred and galloped through under a pretty strong fire. Three of the horses were shot dead but no men hit. We then got to the rear and Major J and myself and one scout and the adjutant started creeping up under cover to see the position of the enemy. This took a good hour. Suddenly a fire was opened on us. Time to beat a retreat. Major J ordered us to dismount and put the horses into a safe position and sent word to Colonel that no chance of attacking kopje unless losing several men. Colonel sent order to attack, burn kraal and retire. We all extended into skirmishing order and the Col on one side opened a heavy fire and finished up with three seven-pounder shots. This was the signal for our attack to commence. Major J called out ‘Advance my boys!’ Double time emerged out of thicket of cover and as hard as possible across the open – some 300 yards to clear. Here unfortunately, hidden by some thick bush, was a small but steep kopje to our right from where a strong and steady fire was opened upon us. It took some three minutes to gain the other side and during this time three men were hit and one poor little fox terrier who was with us was shot right through the shoulder and dropped dead in front of me. Poor little thing, he died like a soldier anyhow. Previous to the charge, Major J said to me, ‘Griffiths, I want you to keep with me.’ (Here I may state that, so I am told, he had formed a very high opinion of me) When we arrived at the bottom of the kopje, which was very steep, we took cover under some rocks to get wind. Major J telling me to keep up a steady fire with my men on the kopje to the right, from where we got the surprise from. While doing this, pouring in independent fire, young Botha, one of my men who was next to me, touching me in fact, received an explosive bullet in his forehead, almost taking the top of his head off. The poor youngster, only 19 years old. Dropped dead, past all assistance or aid. It was a terrible sight to see him lying dead. One of our best scouts, always willing, plucky and I never had to tell him twice to do a thing. God help any Mashonas if I could have had any within reach of my hand then. When we saw he was quite dead I left him there for the time being and Major J and myself and scouts led the soldiers up the kopje, forced our way into the kraal losing two more men and wounding several. After searching some men all done in a few seconds, we pretended to retire when several n*****s jumped out of the caves to take aim at our supposed retreat, were promptly bowled over by our men, one n****r getting 7 bullets in him. Good luck to the black devil. We then set light to the huts and obeyed the Col’s orders to retire.

Over this attack I must remark that it was surprising to see that some of our men were not killed. The fire was simply terrible from the enemy and it’s the day I shall never forget to my dying day. Each man during that attack, I am sure, felt he was near his death. Thank God not more were shot and thank God I was saved. Myself and 3 others carried poor Botha back until we met the ambulance corps. At 6 o’clock we buried him. Then we made a rough cross and put it upon his grave.

When we were charging up the kopje, some 20 or 30 n*****s charged down on the right, this coming under the notice of the Colonel and were promptly mown down by the Maxim. I am too tired to write more tonight and am also upset over poor Botha. It was only a few days ago that he received a telegram of his sister’s death and this is the second son who has been shot in this country and his father is dangerously ill in the Salisbury hospital.”

13, 14 and 15 October 1896: “….seeking fresh [illegible] bad for horses. Very bad coats and very scarce and frightfully hot.”

16 October 1896: “Continued trekking . Sent Steven and half a troop detail for special duty with myself and 5 other men to follow up a k****r footprint which was seen. After riding across country for some distance, we came upon a scherm lately occupied by n*****s. Myself and F… went up the hill and burned same and returned to the others. Came to a good size spruit where we saw lion spoor but couldn’t find lions. Continued some two miles alongside of water and came across another temporary kraal with 13 huts. My men burnt them and we then made in the direction of where the laager was supposed to be. Found them after hours of riding. Had grub my boy cooked, a good sleep, then went down for a bath.”

17 October 1896: “Continued trekking. After going some 8 miles we came up to the Hunyani [Manyame] river. On the march one of the scouts belonging to Col. Alderson’s column was fetched up on a stretcher and put in an ambulance wagon having had a fall off his horse while chasing two n*****s which he saw whilst out scouting, he having fallen with his chest on a stone. Nothing serious. We laagered by the river which is big and very pretty. Off-saddled. Had scoff. Then 2 hours sleep. Went for a swim. Previous to anyone swimming, the river where the bathing was to take place was dynamited, a charge being thrown in. The surface of the water was covered with dead fish. We all then plunged in, bringing fish to the bank. Splendid eating and quite a treat. Enjoyed my dinner so much. We fried them in a pan. The particulars of Norton’s murder by k*****s is very terrible to hear. One of the other columns relayed me the facts.”

18 October 1896: “Both the Colonel’s and our laager moved off today at 6am. The Colonel’s column continuing towards Reform where Eyre[v] was murdered some 20 or 30 miles off. Four sections of scouts under myself, also 30 of the native contingent left laager at 6am to patrol the Hunyani river to look for kraals. About 3 miles downriver we came to Selous’ old camping ground, the river here was very pretty indeed and very wide, reminding me in some parts of me dear old [Thames?] Here we are into lovely country, very flat indeed, but very wooded and full of all kinds of game. Small and big buck, great buffalo, etc. We the scouts went ahead. I dodged off myself into the thicket and had some good shooting, killing amongst others a splendid Cessily[vi] buck. I was so interested in chasing the game that when I came to look about me, I hardly knew in which direction to go, for nothing to guide me, high trees all around. I should like to spend a month here shooting. No wonder Selous chose this spot. We off-saddled by the river about 10:45am after riding since six. Turned horses loose, knee-haltered to graze and had our grub. I took my billy off saddle and cooked some tea of which Major J and others partook as well and pitched into the corned beef and bread. After an hour’s rest saddled up and proceeded on our way home. Came across a section of Colonel Alderson’s column who had lost themselves while out flanking. Their officer declared: ‘Thank God we have met you.’ He also said he had lost two of his men in the bush. Their horses were all done up after galloping about all day. We then fired the seven-pounder twice as a signal to the other two, which was heard by them. They found our laager almost at sundown. It is a terrible thing to be lost in the veldt. Many have been lost and died dreadful deaths. We saw no n*****s whatever during the day, nor any signs of them. Had soup, fried fish for dinner, rice, treacle, off to sleep very tired. So is my horse who is rather footsore after chasing buck over stony ground.”

19-24 October 1896: “These six days we have been trekking, going through lovely country full of all sorts of game. One day shooting an ostrich. Having good sport. Yesterday I shot a porcupine. On 21 October we laagered at Eyre’s farm, awaiting the Natal Troop with provisions from Salisbury. Mr Eyre,[vii] the owner of the farm is acting as our guide. He is a very nice man indeed. I knew him in the early days in Johannesburg. His brother was murdered on the farm by the Mashonas while he was away. He has been trying to find the body, but cannot do so, only seeing the blood stains. I expect the Mashona have taken the body away. The Colonel’s column went out to some kraals some 7 or 9 miles away, the n*****s who are supposed to have murdered Arthur Eyre. We (Honey’s column) were left in to have a rest this time having done most of the fighting hitherto. So, not going, I cannot say really what happened.

They found that all the n*****s from these kraals had gone into a cave, with only two small openings. While trying to get at them, Captain Furnancou,[Finucane[viii]] of Salisbury Volunteers, was shot in the leg. They put five charges of dynamite into the two entrances and completely, it seems, entombed them. I hope so. Returning to the laager bringing this Furnancou with them, who I am sorry to say died shortly afterwards from loss of blood. His death cast quite a gloom as he was a very popular officer indeed. The following morning his funeral took place. The Salisbury Volunteers made the firing party over his grave, all the buglers blowing during the process. Yesterday the Natal Troop arrived with the provisions, having had a quiet trip and unmolested, not seeing any signs of n*****s whatever. I went over to see the Colonel previous to his departure for Salisbury to meet Rhodes who is expected there. He was very well…and was of great service to Major Jenner, who had spoken highly of me. He said if I wanted to join a new police force he would recommend me for a commission. I of course thanked him and said I would join if I did get a commission. Otherwise, I would like to remain with the troops while in the country.

This morning we left at 6am for the Mazoe district. We trekked on until about 10am when we laagered at a place I found for the column. This generally is my duty, going ahead and finding a good place with water, good grazing, etc. It is sometimes a difficult job to find both of these. We have no grain whatsoever for the horses. Poor devils have to live on grass, so we cannot do long treks owing to this. Also the mules wouldn’t stand it. Our new [illegible] Highfield seems a good sort, an Inniskilling Dragoon. I hope we shall come across n*****s soon.”

25 October 1896: “Wrote to Mother and Arthur yesterday and sent into Salisbury with the Colonel’s column.”

Sub-Inspector in the British South Africa (BSA) Police; posted to Fort Martin and Fort Hill

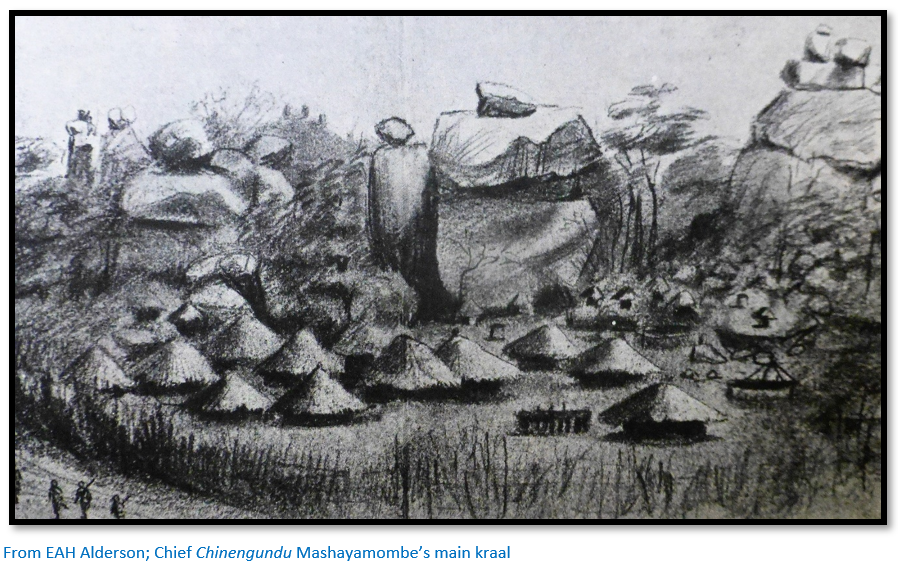

For a full account see the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and the Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com. As soon as Lieut-Col Alderson’s force left the area Chief Mashayamombe and his followers returned to their kraals to rebuild their huts and plant their crops before the coming rains…to keep him in check it was decided to build Fort Martin approximately 1.5 kilometres to the northwest of his main kraal. The fort was named after Sir Richard Martin who had been recently appointed Commandant General of the BSA Police by the High Commissioner for Southern Africa Sir Hercules Robinson as part of an attempt to assert imperial control.

The article mentioned above has photographs of where the BSA Police mounted a seven-pounder gun on the very summit of the kopje with the kraal well within its range. Captain RC Nesbitt took over command of the fort on 20 February 1897 writing: “It is very healthy, being splendidly situated, very high…it is impregnable and the best possible place.” Fort Hill had been re-occupied on 1 December 1896 by the Natal Troop and then two weeks later by Major Hopper and eighty men of the BSA Police but numbers were reduced in favour of Fort Martin as the men suffered badly from malaria fever. See the article Fort Hill and the cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Jack does not seem to have kept up his diary between late October 1896 and March 1897 when he was appointed second-in-command with his new commission as a sub-Inspector (Lieutenant equivalent) under Captain Nesbit at Fort Martin.

Military operations began to disrupt crop planting which forced Chief Mashayamombe to attack Fort Martin with 300-400 men on 17 March 1897, but they were driven off after a battle lasting three hours in which three of the fort’s African auxiliaries were killed.

Action needed to be taken against the recalcitrant Chief and Jack who was now in command at Fort Hill received the following from Nesbitt:

Confidential Fort Martin

Thursday, 22 July 1897

Sub-Insptr Griffiths

Commdg Fort Hartley

The Salisbury column is to arrive at the Zomba drift about six miles from Hartley, on the evening of 22 inst. (today) The attack on Mashingombi [sic] is to be made on the morning of the 24 inst. At daylight. You will leave a guard of six effective men (Europeans) and four of the native contingent at Fort Hartley and proceed yourself with the rest of the men and native contingent on the morning of the 23 inst. (Friday) bringing all horses which are fit. Mr Peel is to accompany you, bring wagons with more blankets, mealies, etc. Leave 3,000 rounds of ammunition (rifle) and 8,000 (maxim) at Fort Hartley and bring the remainder, also field stretchers if there are any, bring four days rations with you. You must start without fail early on the morning of the 23 inst. So as to arrive here on the evening of the same date. When approaching this fort (before arriving out of the bush) take your mounted and most of your dismounted men around by the way of where we get water and come up through bush, so as to prevent if possible the Natives noticing the arrival of reinforcements.

R.C. Nesbitt, Captain

At dawn on 24 July 1897 Chief Mashayamombe's stronghold in the kopjes behind his kraal was attacked by local forces under the BSA Police and led by Inspectors Nesbitt and Harding and Lt-Col. de Moleyns and taken after stiff opposition. The defenders retreated into a large cave but were blockaded within and surrendered next day. Chief Mashayamombe’s fate is unclear, but he may have been killed on the second day of fighting when an attempt to break-out of the caves was made at dawn and there were some casualties.

Fort Martin was abandoned the following year.

BSA Police Sub-Inspector at Sinoia, now Chinhoyi

For his next posting Jack was sent to Sinoia in charge of 30 NCO’s and men. The police station at Sinoia in the Lomagundi district west of the Manyame river was connected by a rough track of 115 kilometres to Salisbury. Both the Ayrshire gold claims north of Banket and the Eldorado gold claims had been registered by this time and would become important economic developments for the district especially after 1902 when a 2-foot narrow-gauge railway using track and rolling stock from the old Beira and Mashonaland Railway was completed.

In 1897 supplies and mail were infrequently delivered particularly in the rainy season when the river crossings were impassable. Tony Bridgland and Anne Morgan state Jack’s police camp became a showplace with visitors out from Salisbury to admire it and presumably the nearby attraction of Sinoia caves [See the article Chinhoyi Caves Recreational Park under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Clearly there was still resistance in the district and Jack’s commanding officer sent the following:

6 December 1897

Dear Griffiths, I congratulate you on the excellent work you have done – and done quietly which I gather from your report with little or no shooting – nothing could be more satisfactory. I am very glad to hear that the patrol has no fever, that is what I was afraid of.

You say nothing about an escort for your prisoners in your second report which I got this morning – as I suppose you still want it, am sending out 20 Black Watch to you this afternoon unless in the meantime Eastwood who is back at Mazoe tells me that you don’t want it.

Very truly yours, F. de Moleyns

P.S. The 20 Black Watch will take rations for the trip out and home.

On the same day Jack was appointed a Justice of the Peace for Lomagundi district.

An article on Lomagundi in Rhodesiana Publication No 10 July 1964 by CTC Taylor contains much useful information including a reference to Jack and the arrests referred to by de Moleyns above: “A map of 1895 shows that a mining commissioner named [Jack] Spreckley had a camp near the present site. The Police who replaced the Imperial troops in 1896 settled near Chinoya’s kraal (later corrupted to Sinoia) and called the places Lo Magundi’s, after the local Mashona Chief. In the National Archives is a single copy of a journal called The Lo Magundi Hornet dated 8th January 1898 and numbered Vol. 1 No. 9. This would appear to be a monthly publication, it has four pages measuring 9 x 13 inches, was printed by the Salisbury Printing and Publishing Co for the Proprietor and Editor, T.V. Rock and was priced at 2/6d.

From it one learns that the total Police strength there was 13 whites and 19 Africans, and that they had already created a record by having arrested 1,100 Africans as alleged murderers during the recent rising. Also that in the Lo Magundi Camp were Mr G.A. Jackson the Native Commissioner; Captain Pocock, the Claims Inspector; Lieut Griffiths; Sergeants Wood and Brown in charge of the local hospital; Corporals Davis, Clifton and J. Armstrong, Paymaster and Postmaster; Troopers Andrews and Hempseed; Messrs Evans, Nell and Jones, presumably prospectors; and Rock the Editor. The Editor wrote that Lo Magundi was rapidly becoming civilised, as Messrs Deary and Co. had nearly completed their new store and one of the local prospectors was said to be negotiating to import a bicycle from Salisbury.”

Fate takes a hand

Jack had registered a gold claim and might have resigned his BSA Police commission and taken up gold-mining using his experience gained on the Rand, but in early 1899 his father, John Griffiths died and a telegram arrived:[ix] “Father passed away. Hurry home. Mother distraught. Nelly.”

He travelled to Umtali via Salisbury and caught the narrow-gauge railway which had been connected with Beira on 4 February 1898 although heavy rains caused a ‘wash out’ and a delay of two days. He missed his boat but managed to catch a tramp steamer as far as Zanzibar.

Here he met his future wife, Gwladys Wood who had visited her brother in Johannesburg with her mother and was returning home, but with a stopover of three days in Zanzibar. Her fiancé had accompanied them, but as she settled into her lodgings: “Suddenly there was a commotion downstairs. I heard the front door swing open, slam shut. Footsteps, voices. A deep male voice I hadn’t heard before. I tensed on my stone seat, leaned a little further out into the yard. A tall man strode into the courtyard. He carried a mongoose on his shoulder and a parakeet on his finger. He was of course in whites with an open shirt and panama hat and was the handsomest man I had ever seen. I fell in love with him at that moment. He always said that when I sang to him that evening on the flat roof at the top of the house, he said to himself, ‘That’s the only girl I’ll ever marry.” So you see the damage was done quickly. That was 22 March 1899.”[x]

Return to Mashonaland

Jack returned to Mashonaland in mid-1899 but told Gwladys they would have to wait to be married…life would be very hard for a 26 year old woman who had no experience of roughing it in the wilds of the Lomagundi district. Jack used his gold claim in the formation of Rhodesian Mining and Development Company with himself as Managing Director and Sir Sydney Shippard as Chairman. Sir Sydney had served as resident Commissioner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate from 1885 to 1895; he was a great supporter of Cecil Rhodes and was appointed a Director of the BSA Company. In 1896 he played an unofficial part in the negotiations after the Jameson Raid, but was now in England.

Unable to raise any finance to develop his gold claims further, they were abandoned on the outbreak of the second Boer War and Jack set off for Cape Town with a letter of introduction.

Salisbury, 29 December 1899

Dear Sir Charles Warren, This is to introduce you to my friend, Mr J.N. Griffiths, late of the Second Life Guards and late in charge of scouts in Colonel Alderson’s column from which he was recommended for his commission in the BSA Police here in which he served and was a senior Inspector. He was mentioned in despatches by Sir Richard Martin and has his medal for ’96 and ’97. He lived for 12 years in the Transvaal and knows parts of it intimately. He wishes to see more service now and to be attached to one of the forces. I am glad you are in Africa again. I am flourishing, but not able now to offer you my personal services as I would like to do.

Yours faithfully, Joseph M. Orpin

Second Boer War 1899-1902

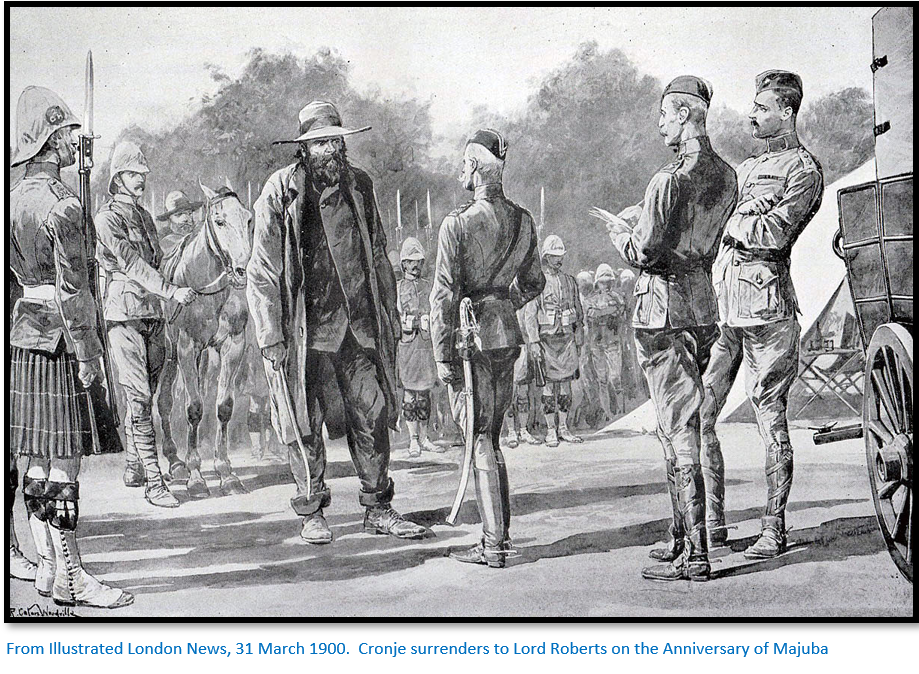

Jack was offered command of a squadron of Brabant's Horse which earned a distinguished record during the conflict.[xi] Dick Hobson has confused persons in his article; Brabant’s Horse was named after Major-General Sir Edward Yewd Brabant, KCB,CMG not Captain Jack Brabant.[xii] He did not stay long in Brabant’s Horse however as Lord Roberts, recently promoted as Commander in Chief of British forces, appointed Jack as Captain of his personal bodyguard and adjutant. In this position Jack accompanied Lord Roberts on one of the most impressive British operations – the relief of Kimberley by Major-General John French on 15 February 1900 and was at Paardeberg when the Boer General Piet Cronje surrendered to Roberts on 26 February 1900; the sketch below shows Jack on the far right.

Mining and Contracting

Jack resigned his commission from the army soon after Paardeberg as on 22 May 1900 he completed a membership application for the Institute of Mining and Metallurgy. He overstated his age as members were required to be at least thirty years old; but he had the required minimum five years practical mining experience in a responsible position. His own address he gave as ‘Salisbury Club’ and his business address as Griffiths Rhodesian Mining and Development Company. He added he was a member of the Salisbury Chamber of Mines and Justice of the Peace for Mashonaland and ‘late Captain and adjutant Lord Roberts Bodyguard South African Field Force.’

Nevertheless eighteen months went by until August 1901 when Herbert Stoneham gave him a commission at £5,000 per year to survey an alluvial gold project in Ivory Coast, West Africa.

First though he married Gwladys Wood and took her to America to source dredging equipment.

After a year on the Grand Bassam field near Abidjan as resident managing director he returned to England and set himself up as a consulting mining engineer.

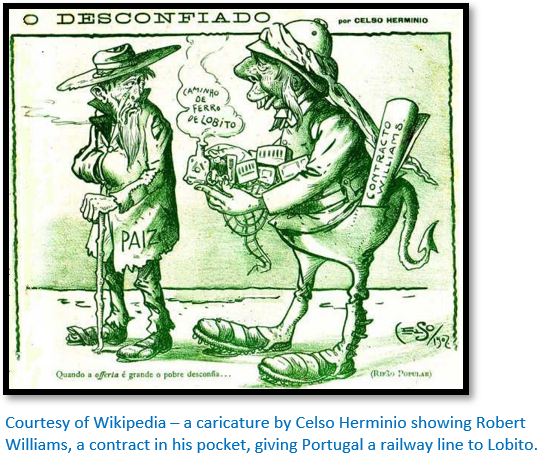

After surveying and giving an unfavourable report on a proposed mining project in the Nile Valley the proposed financiers brought him into a project for the building of the Benguela Railway, the brainchild of Robert Williams and his Tanganyika Concessions Ltd (TANK)

Benguela Railways

George Pauling the contractor built much of the railway in present-day Zimbabwe but work in Angola stopped due to contract difficulties in August 1903 when only a wood jetty and few miles of light railway track out of Benguela had been built. [See the article The Beira and Mashonaland Railway – the Contractor’s stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Although Jack had no experience as a contractor he decided he could build the railway. On his first survey visit to Angola he decided that Benguela was unsuitable as the rail terminus and bribed the ship’s Captain £100 to put into the almost uninhabited port of Lobito with its’ outstanding natural harbour. Following this survey he made a contract proposal which was accepted.

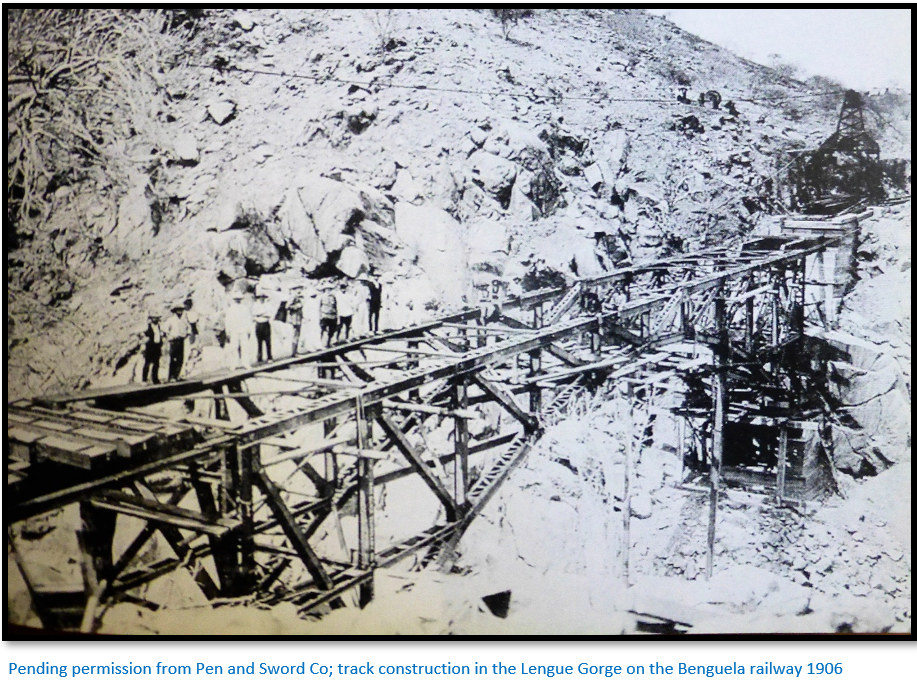

In May 1905 he and Gwladys sailed for Angola; the contract had only eighteen months to run in which 197 kilometres of rail track to Cubal had to be laid including a five mile rack and pinion section over a 915 metre (3,000 ft) escarpment. (2.5% gradient for half a mile; then 6% for two and a half miles; then 2.5% for two miles) With a labour force of 10,000 men he completed the first section to Cubal section with three days to spare.

In the Lengue river gorge which included the rack section work continued day and night with electric lights suspended on cables – Varian says it formed: “a weird illumination for the swarms of natives working on the rock faces of the gorge” and they worked in continuous shifts throughout the twenty-four hours.

In 1908 he returned to complete a further four hundred kilometres of rail track before a copper slump forced the Tanganyika Concessions Ltd to cancel further work due to shortage of funds.

For those interested in a more detailed account – read H.F. Varian’s account in Books of Rhodesia Volume 31 Some African Milestones. Varian worked for Messrs Pauling and Co who completed the railway from Cubal to Luau on the Congo border. Several mountain ranges without any natural route for a railway had to be negotiated and the railway ran through an extremely rough and waterless region.

Cecil Rhodes sent out an expedition in 1899 under George Grey with instructions to prospect as close to the Congo border as possible as he believed the great divide between the Zambezi and Congo rivers would be rich in minerals. He was correct and they discovered Kansanshi Copper mine in Zambia which still operates today.[xiii]

Sir Robert Williams obtained prospecting rights in the Katanga district of the Congo from King Leopold after a well-known Belgian geologist Professor Cornet examined old workings and wrote a negative report on the old workings but failed to test underneath these workings.[xiv] By 1902 Grey had proven the existence of the Copperbelt extending for 320km (200 miles) and located gold, tin and diamond deposits. The existence of these great copper workings provided almost the sole economic reason for Williams obtaining a 99 year concession from the Portuguese on 28 November 1902 to build and run the Benguela Railway (Caminho de Ferro de Benguela - CFB)

Opposition from Germany, difficulties of finance and construction plus the outbreak of WWI and the sheer distance of nearly 1,800km combined to delay the completion of the project until 1929, although by then Jack was no longer involved in the project.

Griffiths and Company

With capital backing of £100,000 from Lord Howard de Walden, Jack formed his own company in 1909 and won an array of contracts. From 1909 to 1914 he spent half of each year on railway projects included 800 kilometres of railway in Chile and 460 kilometres from Arica in Chile to La Paz in Bolivia. Contracts in England included Yarmouth and Weston-Super-Mare piers, Southsea promenade and parts of the London Underground. An aqueduct of 170 km (105 miles) was completed in Baku, Azerbaijan, a harbour in New Brunswick and the first skyscraper in Canada, the Dominium Trust Building in Vancouver.

However, more significantly for this article, Griffiths and Co had won a contract to build the Battersea to Deptford drainage system and also in 1913 was contracted to lay the sewage system in Manchester. It was this ready pool of workers with a knowledge of tunnelling that allowed him to form a regiment aimed at changing the dynamics of the First World War.

Member of Parliament

In January 1910 he was elected as a Conservative MP for Wednesbury, standing on a platform to protect British trade and was a staunch advocate of Imperial projects and ideas – his election speeches always included a large map of the British Empire. Some of his earliest contributions in the Commons included asking for reform of the House of Lords, albeit allowing territories that were part of the British Empire to have representation.[xv] In 1913 he also asked Ministers to provide relief to the families and children of workers striking in the Midlands. He held the seat until 1918 and was known in the House of Commons as “Empire Jack.”

From 1918 until 1924 he was the Conservative MP for Wandsworth in London.

First World War

As Whitehall prepared for war at the end of July 1914, Norton-Griffiths was like many enthused by the prospect of a decisive and quick victory against the Germans. On 21 July 1914 he advertised in the Pall Mall Gazette that: “that all Africans, Australians, Canadians and other Britishers who served in either Matabeleland, Mashonaland, the South African War…should apply to Mr John Norton-Griffiths MP.” At his own expense, he organised and equipped 500 applicants as the Second King Edwards Horse, the only force of irregulars to achieve official blessing;[xvi] he was commissioned Major in the regiment.

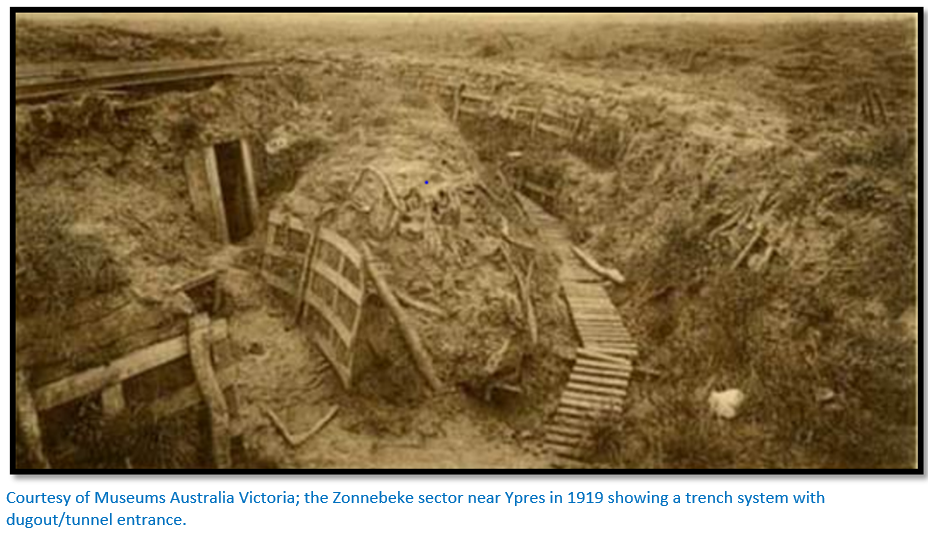

The First World War is traditionally known for the trench warfare and siege conditions which existed by November 1914 producing a state of attrition and stalemate. Both sides faced the need to break through the enemy's defensive entrenched positions and soon made innovations by mining and counter-mining intensively. For the infantry above ground, the wait for underground explosions was nerve-wracking; for the men underground, hard toil often came accompanied by sudden death.

Mining and counter-mining

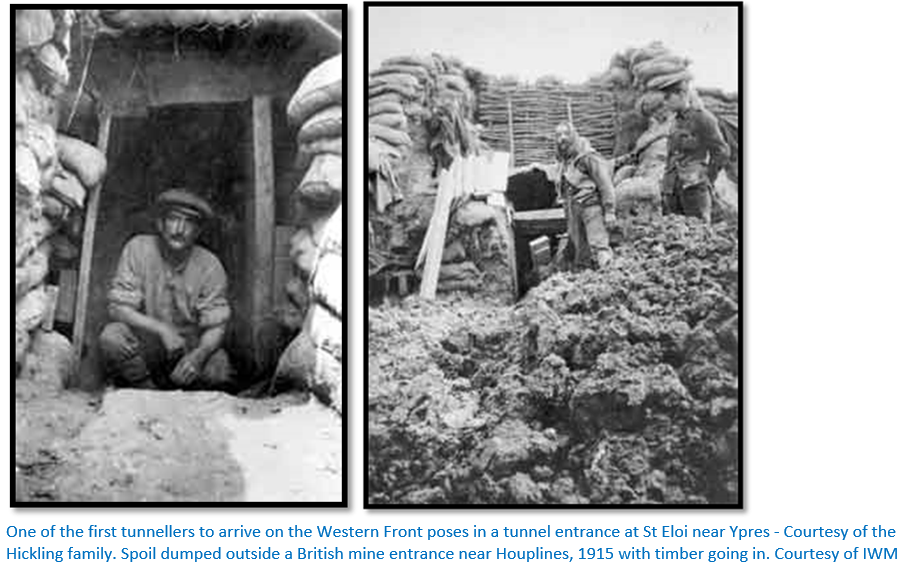

On 20 December 1914, German sappers placed ten small mines each of 50kg beneath the positions of an Indian Brigade in Givenchy-les-la-Bassee.[xvii] The detonation and follow-up attack next day led to the loss of 800 men and following further attacks, it was evident by January 1915 that the Germans were tunnel mining to a planned system which was leading to more successful German attacks.[xviii]

Initial British mining operations

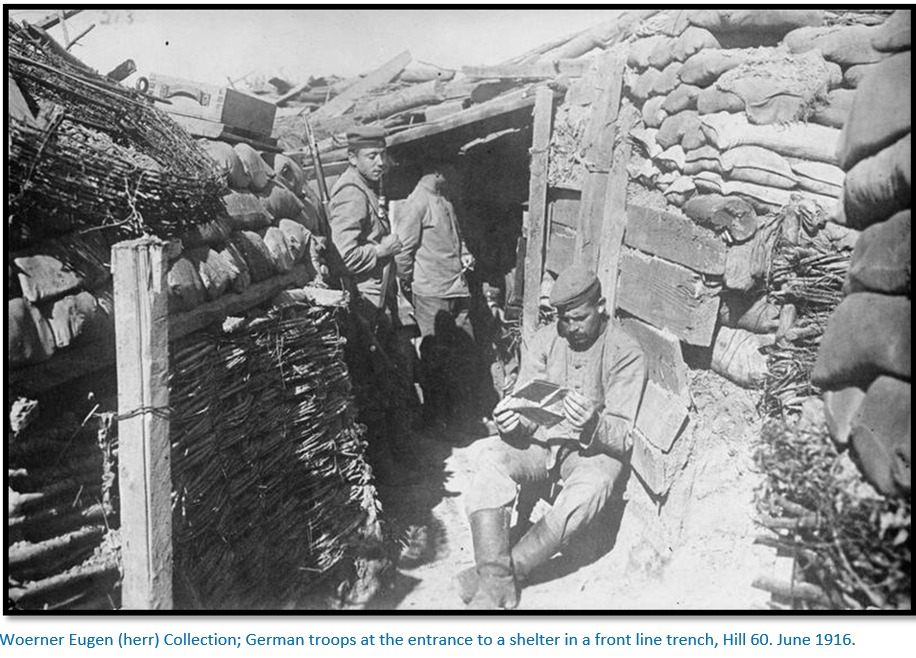

On 3 December 1914 the commanding officer of IV Corps, Sir Henry Rawlinson, requested the establishment of a special battalion to assist with mining duties as the German mining caused disquiet at the War Office. The Royal Engineers responded but found the sandy wet clay of Flanders heavy going and apt to flooding; nevertheless on 17 February 1915 the first British mine was blown at Hill 60 by Royal Engineer troops of 28th Division.[xix]

Norton-Griffiths offers his assistance

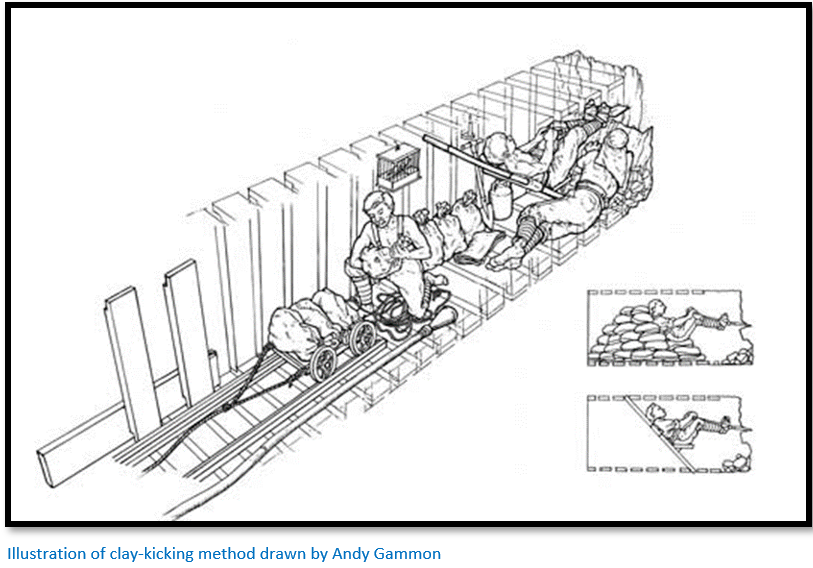

In early December 1914, Norton-Griffith’s engineering firm Griffiths and Co was working on a contract to extend the Manchester drainage system where the men driving the tunnels were using a method known as "clay kicking;" he wrote to the War office saying that his tunnelling workers could be useful for the war effort in Flanders as he believed their experience in tunnelling and engineering would allow his tunnelling teams to undermine enemy positions and counter Germans efforts. The Manchester geology was similar to that of Flanders - heavy clay. Rather than using picks with their arms to tunnel through the clay his men employed the far greater power of their legs; the “clay kicking” system is explained below.

His letter was not initially acted upon, but on 12 February 1915 he received a telegram instructing him to report to the War Office. His granddaughter Anne Morgan[xx] says: "Norton-Griffiths barged into Kitchener's office, grabbed a shovel from the grate, went down on the floor on his back, threw his legs in the air and began furiously shovelling imaginary earth between his feet to demonstrate clay-kicking." Lord Kitchener, then Secretary of State for War was impressed and asked Norton Griffiths to go immediately to France and examine the ground conditions on the battlefront to ensure that his method would work.

Next day, 13 February, he arrived at the office of the Engineer-in-Chief (E-in-C) at GHQ in St. Omer, France where he repeated his demonstration, explaining that the tunnels could be used for attack, for spying or for counter-mining German tunnels coming in the opposite direction. Brigadier (later Lieutenant General Sir) George Fowke, was persuaded by the demonstration and instructed his assistant, Colonel Harvey, to take Norton Griffiths, plus the two employees he had brought with him, to Army and Corps headquarters the next day, 14 February, to see what their engineers thought of the idea.

They visited Army, Corps, Division and Brigade headquarters where Norton Griffiths repeated his demonstration and finally, they got to the front line, a mile from the point where the first German mine assault had taken place in the previous December. His manager and works foreman, 35-year-old Norman Richard Miles, told his boss the clay was: "so ideal it made his mouth water." Further meetings followed at GHQ on the following day and Norton Griffiths was sent for by Sir John French, the Commander-in-Chief, for a personal demonstration.

Brigadier Fowke was now convinced and Norton-Griffiths was given War Office permission to return to England and start assembling his first units of "clay kickers" - soon to be known as tunnelling companies. He had wanted these units to be called Moles, but this was over-ruled. However, many of these companies retained the mole as their unit sign. By 17 February Norton-Griffiths was back in London where he was granted an immediate interview by Lord Kitchener, to whom he reported on his visits in France and on the reactions of the engineer and infantry officers to his suggestions.

Formation of the tunnelling companies

His proposal to recruit large numbers of civilian tunnellers and to throw them into the "deep end" without any form of military training was not well received by the War Office, but his persuasive manner won the day and War Office approval was given in early February to form the first of what would eventually be nine tunnelling companies.

Norton-Griffiths went to Liverpool, closed a tunnelling contract there and took eighteen of his "redundant" employees to Chatham to be enrolled, clothed and made into Royal Engineers and by the end of the month eighteen "Manchester Moles" sewer men were in France as founding members of 170 (Tunnelling) Company, Royal Engineers. Many were over 40 years old, white-haired and toothless. Most were small – less than 163cm (5ft 4in)[xxi]

This has been described as the quickest intentional act in the war: men who were working underground as civilians in the UK on 17 February 17th were underground at Givenchy only four days later, such was the need for countermeasures against the Germans. Another 12 British companies were eventually formed in 1915, and another in 1916. A Canadian tunnelling company was formed in France and two more arrived from home, by March 1916. Three Australian and one New Zealand tunnelling companies arrived on the Western Front by May 1916.

The first nine Royal Engineer Tunnelling Companies, numbers 170 to 178 was each commanded by a regular R.E. officer, comprised 5 officers and 269 sappers, aided by temporarily attached infantrymen from front-line units as required. Norton-Griffiths, in the rank of Major, acted as liaison officer between these units and the E-in-C in St. Omer.

The new recruits in these units, aged anything up to 60, did not readily agree with military discipline; the average infantry soldier would have nine months of drill, getting physically fit and learning the rules of order and obey before being deployed. Although in uniform, the tunnellers couldn't march, drill or salute and were more likely to call an officer "mate" rather than "sir." They were the founder members of 170 (Tunnelling) Company, Royal Engineers; by the war-end the tunnelling companies had dug more than 4,800 kilometres (3,000 miles) of tunnels in France, Belgium and Gallipoli.

Recruiting continued at a frenetic pace, with Norton-Griffiths constantly giving the impression of being in several places at the same time. His judgment of people was remarkably accurate and he very rarely made a mistake in selecting men for a commission. As the Tunnelling Companies developed, many ex-miners already serving transferred from their units and by the end of 1916 there were more 30 companies involved in this massive exercise.

The formation of tunnelling companies which were military units yet had no actual military training or experience

John Norton-Griffiths MP was the spearhead behind such efforts and his drive to implement the tactics of tunnel warfare led ultimately to the recruitment of 20,000 miners and engineers.

His recruiting efforts concentrated on 'clay kickers' from the north of England but regular infantry were also recruited. The first units of the Royal Engineer tunnelling companies were formed – eventually there would be nine. The issue of pay was also a major source of friction for the miners and almost led to strike action. Norton-Griffiths acted as the negotiator between military command and the miners, managing to introduce an escalating pay scale based on experience and skills.

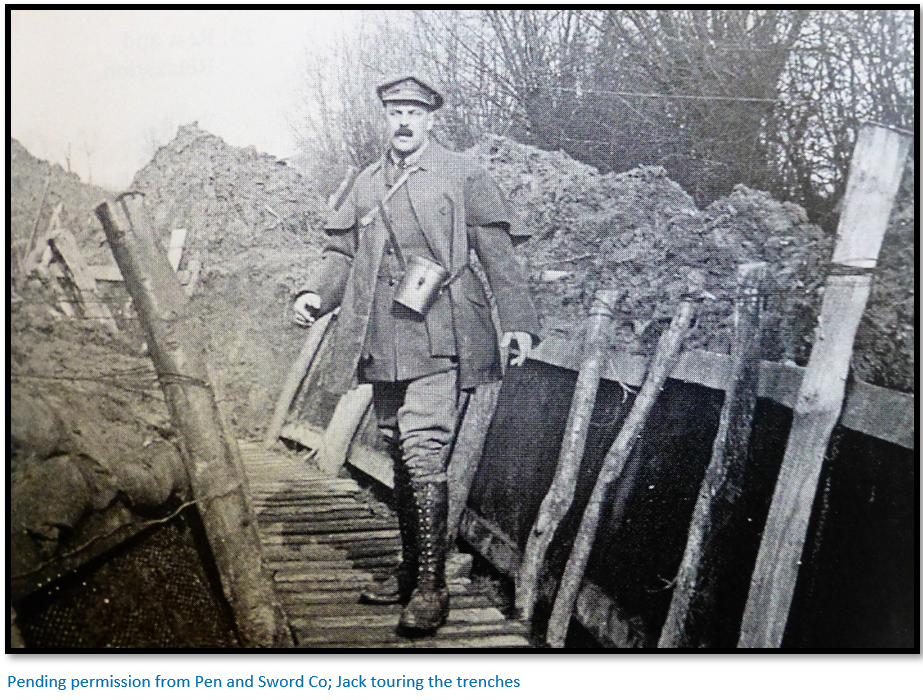

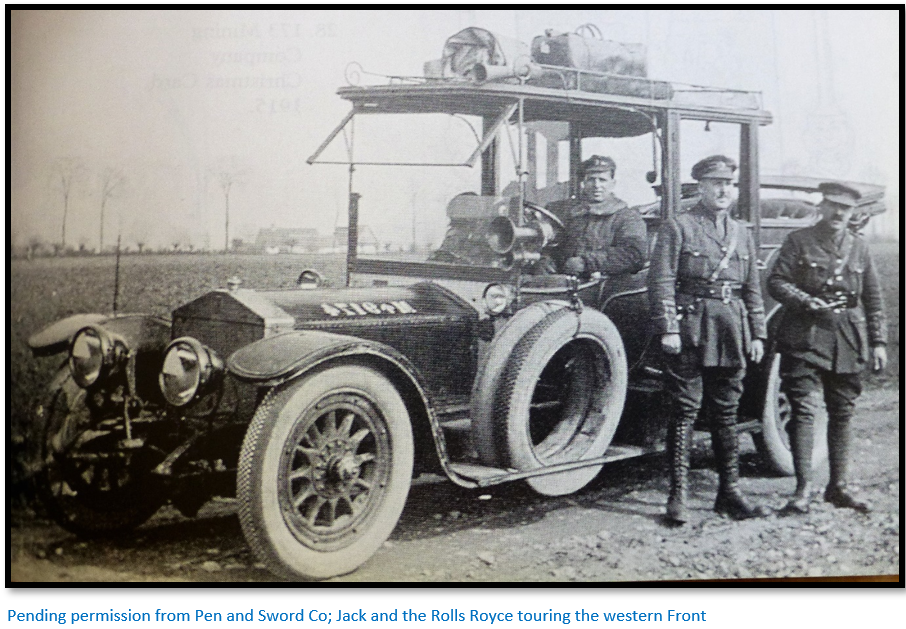

Anticipating much travelling in France and Flanders Norton-Griffiths decided he might as well be comfortable and persuaded the War Office to purchase his Rolls Royce and this larger-than-life character was soon renowned for touring the trenches in his Rolls-Royce loaded with cases of port. "He wasn't always the most politically correct man - he was impatient, of a rebellious nature and went on to bribe commanding officers of different companies to let him have their miners by getting them drunk on fine port - but he was certainly charismatic."[xxii]

Underground warfare develops

Once both sides started mining operations there was a struggle for tactical superiority. At Hill 60, The Bluff, St Eloi, Aubers Ridge, Hooge, Givenchy and Cuinchy, where the front lines were very close together and the geology suitable for tunnelling, the mining companies tunnelled under German strongpoints and also attempted to detect German mining operations. When they were detected in close proximity, a camouflet would be exploded to destroy the German tunnel, often at the cost of severe damage to the British tunnels. There were many underground encounters, breaking into an enemy position, meeting the enemy underground. Sometimes these encounters included fighting in the tunnels and chambers.

The 170 Tunnelling Company diary entry on 3 April 1915 states: "Charges were put in the ends of galleries and exploded, blowing up a strong point in the enemy's line... In the meantime the Germans had started a counter-mine, but we managed to blow up their trenches bringing down the front half of a brick stack which had been hollowed out and used as a sniper's post. One of the snipers could be plainly seen when the smoke cleared away pinned in up to his middle by the fallen bricks."[xxiii]

The development of tunnel warfare

Norton-Griffiths and his officers and men developed a range of innovations to assist in the varied conditions of the western front and the various geological conditions encountered varying from dry chalk to muddy clay.

- Clay-kicking: involved a man sitting with his back supported at a 45-degree angle against a wooden rest (the cross) and pushing a small, razor-sharp spade-like implement (a grafting tool) into the clay face before him with his feet and then passing the soil over his head to a ‘bagger’ for removal. It was not only quick and efficient, but quiet. “Clay kicking" was used commercially in small diameter tunnels: “The tunneller lay on his back, at 45 degrees to the floor of the tunnel, and facing the work-face, supported by a wooden back-rest shaped like a crucifix. He dug away at the wall into clay before him, using a special long-bladed light spade between his feet. The clay was hauled out by the digger's mate, who worked behind him with another man who helped him load it into sandbags to be dragged to the rear. A second team lined the tunnel with wooden props to prevent it from collapsing."

"A clay-kicking team," says Peter Barton, author of Beneath Flanders Fields and mastermind of the Tunnellers Memorial at Givenchy, "consisted of a kicker, who silently prised out clay "spits" at the "face", a bagger who quietly put the spits into sandbags, and a trammer who put the bags on a small trolley on rails which led back to the shaft.” On its return journey the trolley brought timber into the tunnel.

The team changed places over their shift time of six hours to relieve their aching muscles. Filled sandbags were hoisted up the shaft and packed along the trenches and dug-outs for additional protection. The method used by the “Manchester Moles” resulted in tunnels being dug at a rate of 8 metres per day compared to the Germans' 2 metres. British tunnels were also deeper and therefore more stable than the German tunnels and they were much harder to trace as they were much quieter. Underground mining continued around the clock - shifts worked eight hours on, sixteen off. The Givenchy tunnels were very wet, claustrophobic and constricted, typically measuring about 4 ft 6in (130cm) by 2ft 3in (69cm) The tunnels had an uphill slope of between 1:50 to 1:100 to ensure drainage.

- Timbering; having cut out the rough shape of the tunnel, a ‘push-pick’ was used to trim the clay to allow a timber ‘sett’ to be fitted. The ‘sett’ was made up of four pieces of wood; a sole for the floor, two side trees (also known as legs), and a cap. The sole went in first, the legs next, and finally the cap. No nails or screws were used to keep the process silent – the sole and cap timbers were sawn with small steps and the swelling clay pushed the constituent parts firmly in place. Setts were 23cm (9 inches) wide and installed one at a time.

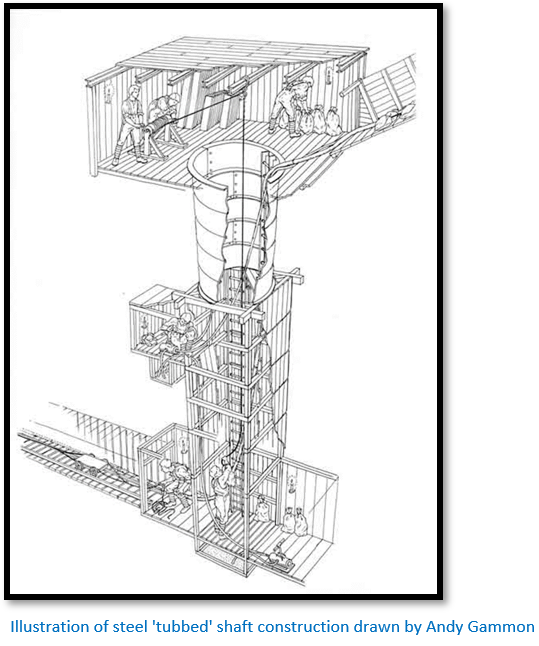

- Shafts; much of Flanders had a layer of quicksand known as Kemmel Sands. Tunnelling above them was easy, but it was extremely difficult cutting a shaft through them as timber supports became unstable and being under pressure from above and below the sands often fountained. The Germans until 1916 considered the problem insoluble.

They failed to realise was that British sappers had overcome the problem by using cylindrical steel shafts known as ‘tubbing’ which arrived in sections and were bolted together to form a vertical watertight tube that crossed the layer of Kemmel Sands. Once the steel shafts reached the dry clay it was safe to continue the tunnelling in timber.

The tubbing also allowed to British tunnellers to go deeper and drive galleries below the Germans and blow deep mines.

- Recruitment of miners; slate, copper and coal miners from all across the UK were recruited and ex-miners serving with infantry units urged to transfer to tunnelling companies. They were paid six shillings a day; even an unskilled tunneller’s mate received two shillings and tuppence, with a soldier in the trenches earning only one shilling and threepence.

With the two sides working in such dangerous conditions and in such close proximity, it wasn't long before the Manchester Moles suffered their first fatalities; a sapper called William Stafford was killed by a German mine on 21 April 1915: "When driving further branch galleries for attack purposes, we heard the Germans working a counter mine near one and exploded a small charge to destroy his work. The Germans put very large charges in their counter-mines and destroyed our forward galleries, besides blowing up a considerable portion of their own trench. Two of our men were killed underground by the explosion."[xxiv]

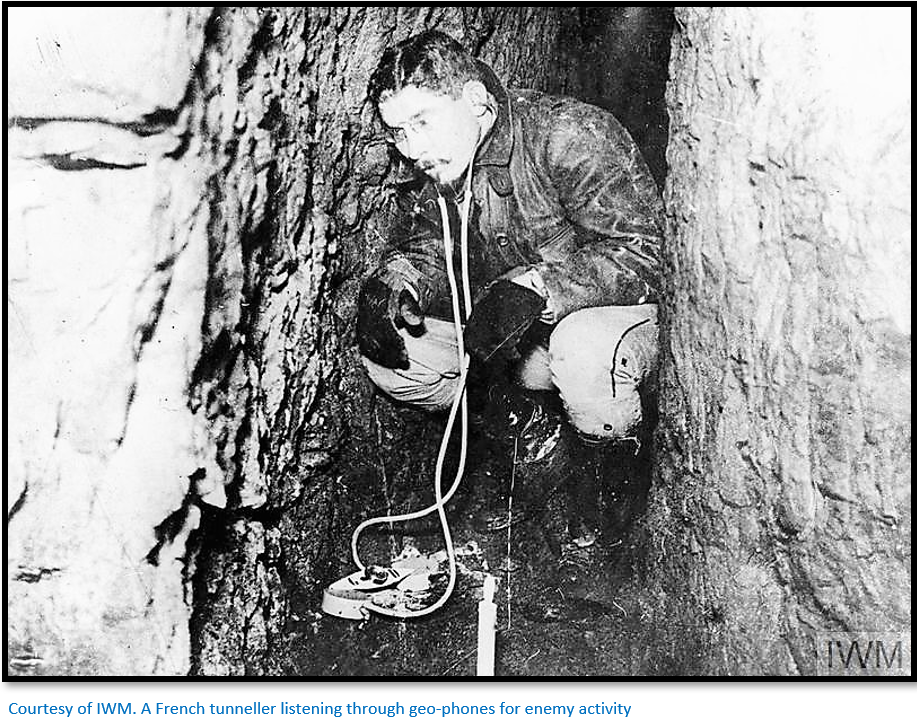

- Geo-phones; the tunnelling war was a blindfold game of cat and mouse and the only way to detect enemy activity underground was by listening - a key ingredient to success lay in detecting enemy tunnelling before the German miners’ were aware. After watching demonstrations at the University of Paris the tunnelling companies were equipped with the geo-phone which was essentially an adapted stethoscope that was incredibly effective - miners could hear German activity from a distance of 30 metres in clay and 80 metres in chalk tunnels.[xxv]

Clay-kicking was quiet; the Germans by contrast used picks and mattocks which struck the ground and made a lot of noise, an important factor in what became a dirty war of mining and counter-mining. The Germans never used clay-kicking as it was not a technique employed in civil engineering and it remained unknown to them for the entire war. Listening became highly developed and trained listeners would use their geo-phone to take compass bearings of suspected enemy tunnelling activity and then compare bearings to triangulate the sound’s location, the direction they were heading and the speed of progress. By the end of 1916 up to thirty-six remote sensors made up of geo-phones and seismic-microphones could be monitored by just two sappers.[xxvi]

If they detected a German tunnel close-by they hoped to detonate a camouflet before the Germans did. Geophones gave the allies an advantage in detection whose object was to ambush the enemy miners and the bodies of many of those killed remain where they fell – deep beneath the fields of France. William Hackett VC is just one example of a ‘mole’ who died in an attempt to help fellow miners when a tunnel collapsed at Shaftesbury Avenue Mine at Givenchy-les-la-Bassee, France on 26 June 1916.[xxvii] The Allies enjoyed so much success by 1916 that the Germans cut back on their tunnelling resulting in most of the tunnels under the Messines Ridge being pushed forward undetected.

- Camouflets: During 1916 one thousand five hundred mines were exploded on the British front, but many thousands of smaller defensive charge, known as camouflets, were also fired. These were small underground blasts designed to destroy enemy tunnels and their occupants.

Two basic offensive techniques were employed. In hard clay the preferred method was to plant a camouflet in a small spur off one’s own tunnel which was specially dug towards suspect enemy sounds. The second method often used in the softer ground of the Ypres Salient was a ‘torpedo.’ These were explosive charges housed in a tube, designed for this kind of warfare. They would be kept in a store at the rear of tunnel systems with at least one torpedo fully charged, primed with a detonator, and ready for instant use.

The main defensive form of mining was to use heavy explosive charges to damage larger areas of underground territory, the purpose being to either destroy substantial sections of hostile tunnels and the occupants or make the ground so shattered that it was difficult to work. These bigger blows often cratered the surface, but the problem with this kind of attack was that one’s own tunnel systems could be equally seriously damaged.

The citation to Manchester Mole Sapper Dennis Murphy’s DCM recorded: "During the operations of a German working party at the end of a 200-foot gallery, Sapper Murphy, with two other men, listened to and noted the progress of the work, and ultimately placed 200 lbs of gunpowder and over 400 sacks of tamping at the end of the gallery, working at the highest speed in bad air, when the slightest noise would have cost them their lives. He showed a splendid example of devotion to duty."[xxviii]

- Ammonal: the introduction of ammonal was another innovation, an explosive far more powerful than TNT that would lead to some of the biggest detonations of World War I.

- Deeper tunnels: Norton-Griffiths was a keen supporter of deeper tunnels, which led to shafts being dug straight down to depths of 30 metres (100 ft) before tunnels were pushed forward beneath no man's land and ultimately under the enemy trenches and strongpoints.

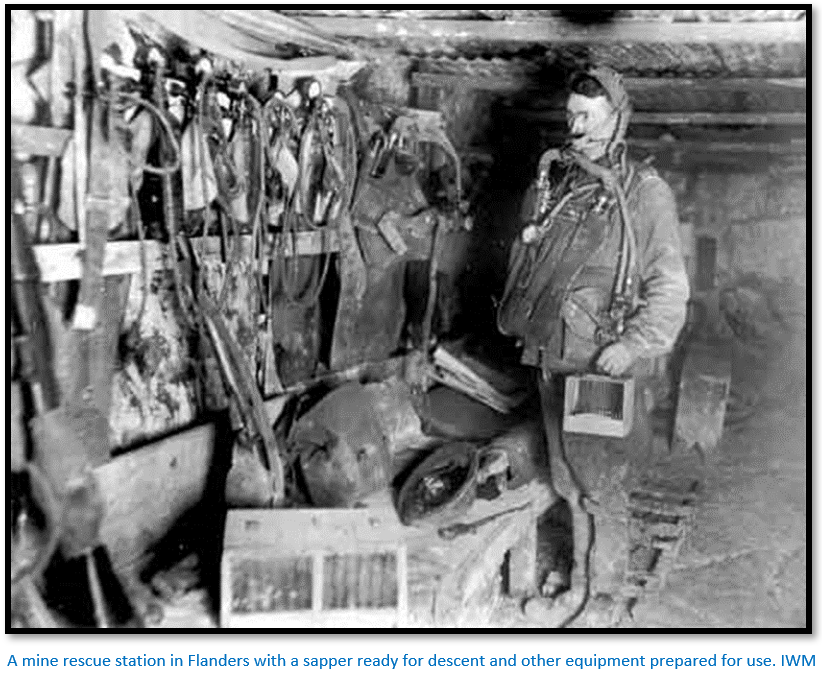

- Gas; This was the most common killer of tunnellers because carbon monoxide gas was generated in large quantities by every explosion. It was invisible and odourless and poisonous. Peter Barton says: "Tunnellers could lose consciousness or control of their limbs in a matter of minutes, so they had to act fast after an explosion. If they were working underground and the shudder of a blast was felt, everyone would race for the shaft to get out into the fresh air before the gas got into their bloodstream."[xxix] Like coal miners, tunnellers carried caged canaries underground as an early warning system and Barton continues: "if a canary fell off its perch, gas was present.”

On the surface the carbon monoxide gas quickly dissipated, but underground it was trapped in the clay and in the tunnels. Tunnellers would be unaware of low level concentrations of gas; but a concentration of 0.2% caused loss of consciousness in 25 minutes; 0.3% in 10 – 15 minutes. Early symptoms would be giddiness, shortness of breath followed by confusion and loss of power in the limbs followed by loss of consciousness.[xxx] If a lot of gas was present a tunneller would be unconscious in minutes with little warning.

In large tunnel systems regulator doors, essentially airlocks, prevented the spread of gas. To find if the air was ‘gassy’ the tunnellers used mice and canaries that have a higher metabolic rate than humans and were affected more quickly by the carbon monoxide gas.

- Proto rescue teams; eventually no shaft was more than 200 metres from a rescue station where two men were always on duty specifically picked for their experience and coolness under pressure. Each had rescue gear and oxygen reviving kit with spare lamps, canaries and rescue equipment including stretchers, primus stove, hot water bottles and blankets.

- Craters: these resulted from the blowing of mines and infantry tactics were developed to rush and seize a crater formed by a mine explosion. As mines used increasing quantities of explosives they often threw up a lip of earth which was higher than the surrounding ground and so became dominant ground feature in their own right. Crater fighting was a feature of many bloody encounters in 1915 and early 1916 and they were always fought over as if a crater could be incorporated into one's trench line it could prove very valuable.

Norton-Griffiths' former sewer foreman, now Sgt Norman Miles returned to the scene of an explosion on 24 April 1915 and was killed: "2/Lt Lacey and 2/Lt Martin who had gone up with Lt Boardall to assist in laying the charge then went out with a patrol of the IG sent to OC section to see if the crater was occupied and found it empty. Sp 66877 Sergeant Miles RE, who had accompanied this patrol, went out again with a second, which was to occupy the crater. The Germans had meanwhile occupied it and shot him dead."

In many sectors of Flanders the Germans and British trenches were about 50 to 100 yards apart, with each trying to seek the advantage. There was an overlapping mass of mine craters between them - it would have been hell on earth.

The 170 TC war diary on 18 March 1916 shows the importance of holding craters: "Germans made a very strong attack on Crater Nos. 2, A, B & C at 5pm exploding a small shallow mine East of No.2 Crater and another north of C Crater, both doing only very slight material damage. Our men were all caught in the crater by the bombardment. 1 NCO and 1 man retrieved from C Crater. 15 RE's and 20 attached infantry missing. The Germans gained crater 2, A, B & C, and we now have bombing posts looking into Nos 2 B & C."

- Working in secrecy: the Western Front became a labyrinth of underground workings but those troops not directly involved in tunnelling (including attached infantry) were not given details of the aims of the mining scheme as leakage of that information might lead not only to the wastage of colossal effort and the ruination of a plan, but the loss of many lives. However the dangerous nature of the work resulted in close relationships being formed between the tunnellers and their attached infantry.

Mining was extremely hazardous work

Sapper Thomas Welsby a 44-year-old father of five, and one of Norton-Griffiths' 18 originals was awarded the DCM for "conspicuous gallantry and ability" at Cuinchy on 28 June 1915. His citation records: "Whilst clearing a gallery which had been damaged by a German mine, he made a hole into the enemy's gallery accidentally, this he at once blocked up with sandbags and laid a charge against it. Our mine was successfully fired, destroying the enemy's gallery, and exploding the charge which they had laid."

1916 represented peak mining activity

By the middle of 1916 the number of British tunnellers had risen to about 25,000 but they were vitally assisted by almost twice that number of ‘attached’ infantry soldiers who worked permanently alongside them as ‘beasts of burden;’ fetching and carrying equipment and timber, pumping air and water and removing spoil from the tunnels.

Working for long periods in dark, wet and cramped spaces was not only physically demanding but caused great mental anxiety. Alcohol was an outlet when the men were off-duty and away from the front lines; court martials for drunkenness were quite frequent. Few tunnellers lasted the whole war with the strain on their nerves and five of the original sewer men received the Silver War Badge, issued to service personnel who had been honourably discharged as a result of wounds or sickness; in all twelve of the original Manchester Moles survived.

A 24 April entry at the Orchard workings in Givenchy reads: "Sounds first heard at 1pm of dropping tools and talking. Action taken by 2/Lt Barclay was to build a barricade against the crater end of our tunnel and to send for Colonel Boardall. This officer was over at Cuinchy and the message did not reach him at once. He arrived at the site between 5 and 6pm and instructed Lieutenant Barclay to construct another barricade 4ft this side of the original one, leaving sufficient space at the top for the [gun]powder to be passed through. He himself came down to arrange about getting a charge ready. Before the second barricade was quite completed the Germans blew a mine killing Lt. Barclay and 6840 Lance-Corporal Bishop, 2nd South Staffordshire Regiment attached to 170 Coy. RE. This happened at 9.30pm."[xxxi]

Major mining operations

- Lochnagar mine south of the village of La Boisselle underground explosive charge was dug by the tunnelling companies under a German field fortification known as Schwabenhöhe (Swabian Height) to be ready for 1 July 1916, the first day of the Battle of the Somme.

Two separate tunnels had been painstakingly dug with 900 men working on each one. Packed with 16,300 kgs (36,000 lbs) of explosives in one and 10,900 kgs (24,000 lbs) in the other, the blast ripped through the ground leaving a chalky crater 100 metres (330 ft) wide and 30 metres (98 ft) deep at La Boisselle. However, German soldiers had detected the tunnelling 24 hours before and retreated to safer ground.

Captain Stanley Bullock of the 179th Tunnelling Company wrote: “At one place in particular our men swore they thought he [the German enemy] was coming through, so we stopped driving forward and commenced to chamber in double shifts. We did not expect to complete it before he blew, but we did. A chamber 12′ × 6′ × 6′ in 24 hours. The Germans worked for a shift more than we did and then stopped. They knew we had chambered and were afraid we should blow and no more work was done there. I used to hate going to listen in that chamber more than any other place in the mine. Half an hour, sometimes once sometimes three times a day, in deadly silence with the geophone to your ears, wondering whether the sound you heard was the Boche working silently or your own heart beating. God knows how we kept our nerves and judgement. After the Somme attack when we surveyed the German mines and connected up to our own system, with the theodolite we found that we were five feet apart, and that he had only started his chamber and then stopped.”[xxxii]

German soldiers were still killed by the powerful blast, but as British infantry troops stormed over the top they were massacred by well-positioned German machine guns. 11,000 soldiers were killed just along this section and by the end of the day's fighting there were over 57,000 British casualties.

Messines Ridge

The British held Ypres town after barely managing to repulse two major German offensives against them in 1914 and 1915 but the troops inhabited a narrow salient overlooked by enemy strongpoints on three sides – the Messines Ridge. But when Field Marshall Douglas Haig ordered General Plumer, Commander of the Second Army to prepare an offensive at Ypres he discovered that Plumer had anticipated him and prepared the groundwork for an operation to defeat the German defences south of the salient in a single devastating blow.

John Norton-Griffiths had been promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel in April 1916 and the mining strategy had first been put forward by him. By June 1917 twenty-two tunnels were finally completed, with nearly one million lbs of explosives laid. [See the article Field Marshall Herbert Charles Onslow Plumer, 1st Viscount Plumer, GCB, GCMG, GCVO, GBE and his connection with Matabeleland under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com for more information on Messines]

The Messines Ridge stretched approximately 8 kilometres (5 miles) as the crow flies from the village of St Yves (near the town of Messines) in the south to Hill 60 in the north from which the Germans enjoyed commanding viewpoints from their strongpoints. Hill 60 provides a good example.

By November 1916 Canadian tunnellers had packed the two chambers; Hill 60A with 24,250 kgs (53,500 lbs) and Hill 60B with 31,750 kgs (70,000 lbs) of ammonal and guncotton. The 1st Australian tunnelling company took over to protect the site until detonation. But the Germans were working furiously to find them and the Australian listeners could detect the Germans approaching one of the two chambers beneath Hill 60. They could hope they missed the chamber or explode a camouflet with the chance it might detonate the main charge.

The Australians chose to dig a diversionary tunnel as quietly as possible towards the Germans until they could clearly hear the sounds of digging through the tunnel wall. Finally on 18 December 1916 they carefully packed 1,100 kgs of ammonal at the end of their gallery and detonated the charge at 2am the following morning.

“A huge tongue of flame leapt skyward from the enemy’s lines, and then all was deadly quiet.” For an instant everyone thought that the primary charge had blown beneath Hill 60. But the explosion was too small; the central chamber was safe and failing to realise how close they had come to their target the Germans abandoned their operations at that spot.

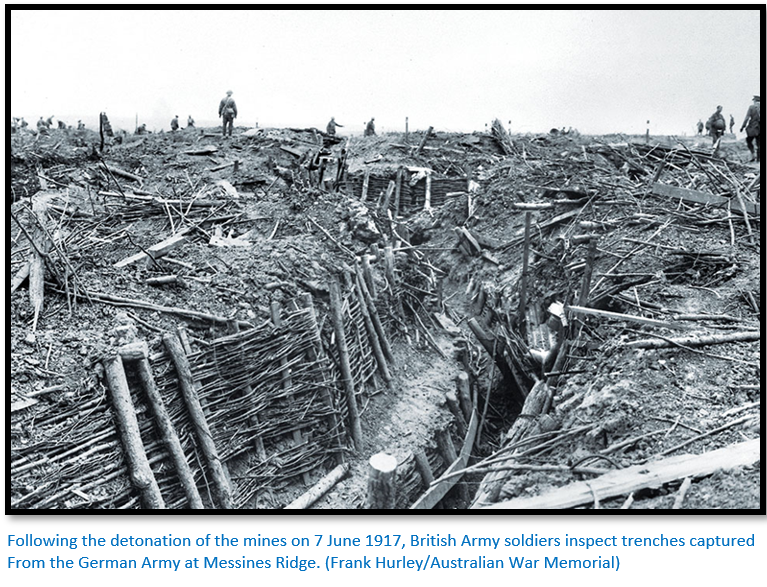

The massive mining campaign in the Ypres salient culminated on the 7 June 1917 at 3:10 am when nineteen huge British mines were exploded beneath the Messines Ridge in Belgian Flanders. In a dugout 400 metres from Hill 60, Australian Captain Oliver Woodward was so nervous that he threw his electric switch too violently, accidentally touching his hand to a live 500-volt pole. As he reeled across his dugout, stunned by the sudden shock, the mines exploded in unison. E. N. Gladden, a British private waiting to attack the strongpoint, later recalled feeling his body suddenly “carried up and down as by the waves of the sea.” As he peered forward, “the earth opened and a large black mass was carried to the sky on pillars of fire, and there seemed to remain suspended for some seconds while the awful red glare lit up the surrounding desolation.” After a few moments, Gladden recalled, the sound “leapt over us like some immense wave.”[xxxiii]

Nine infantry divisions with 80,000 men moved forward. The blasts killed as many as 10,000 German soldiers; 7,000 more were captured in a state of shell-shock and shattered morale that enabled the British to capture the enemy positions within hours. Hill 60 had two craters, one 90 yards across and 16 deep and the other 69 yards across and 11 deep. Each crater was surrounded by three-yard-high rims of concrete and debris, including fragments of equipment and men. Here and there a lucky survivor emerged to surrender.

The explosions were said to have been heard by the British Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, 240 kilometres (150 miles) away in 10 Downing Street. The attack was one of the war's few unalloyed successes.

Most tunnelling stopped after 1917