Traveller’s tales from the Devil’s Pass

The Devil’s Pass is almost unknown to people living in Zimbabwe nowadays.

The construction on the railway line from Fontesvilla, 56 kilometres from Beira began in September 1892. The 222 mile (355 kilometres) link to Umtali (now Mutare) was built with 2ft 0 inch track gauge using 20lb / yard rail and only completed in February 1898 after immense difficulties had been overcome and many lives lost. On 23rd May 1899 the 3ft 6 inch gauge railway link between Umtali and Salisbury (now Harare) was completed; the Umtali Beira line being converted to the same standard gauge by August 1900.

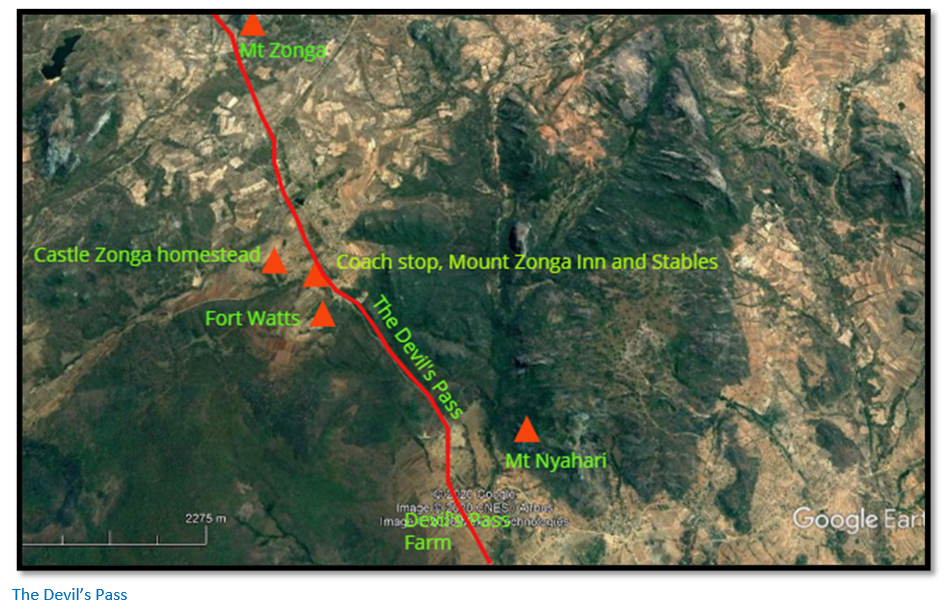

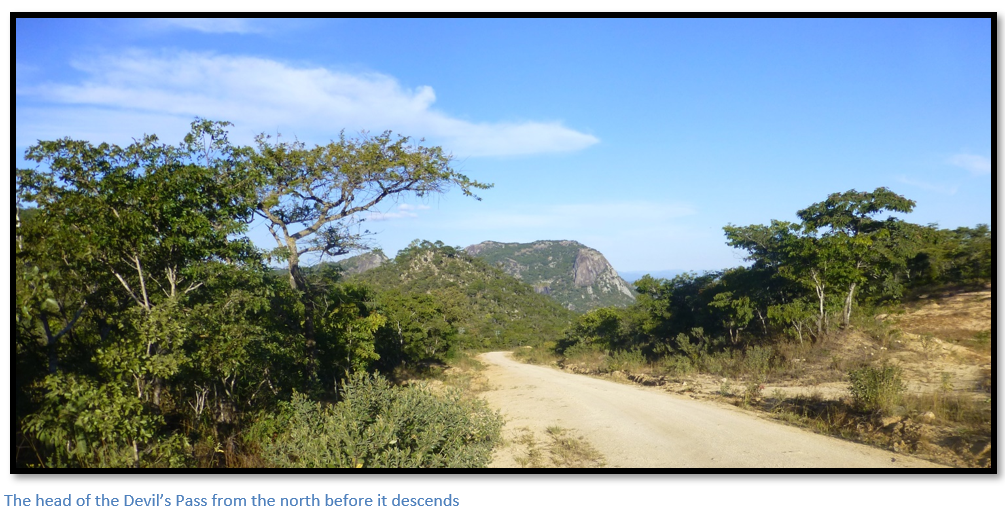

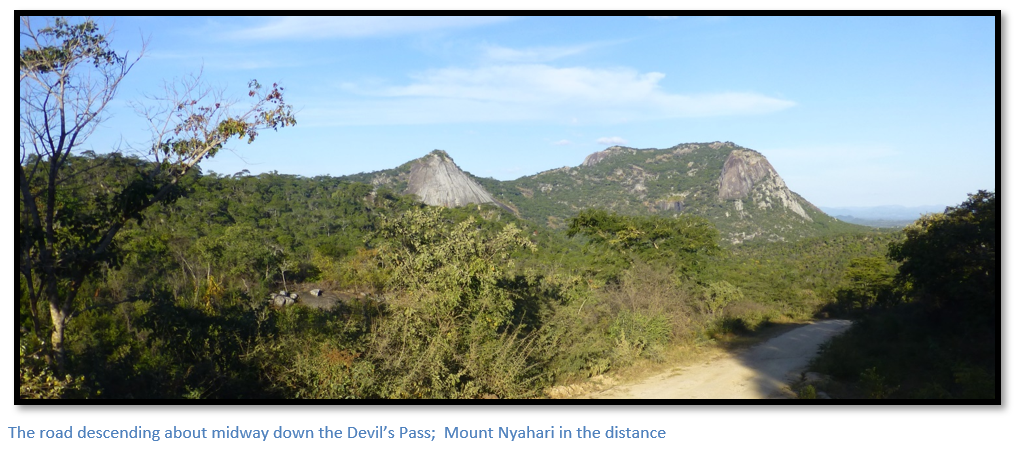

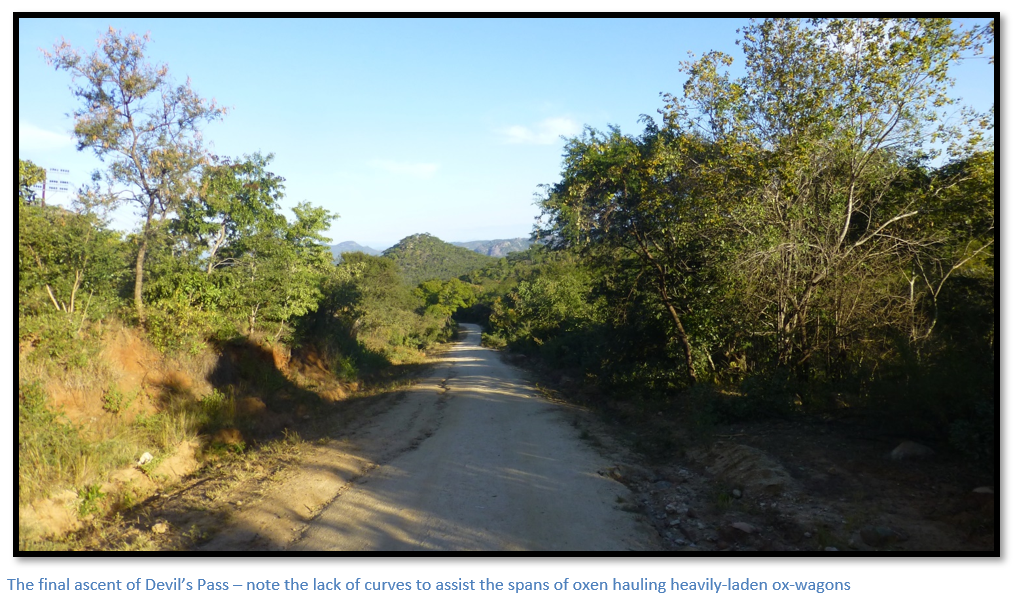

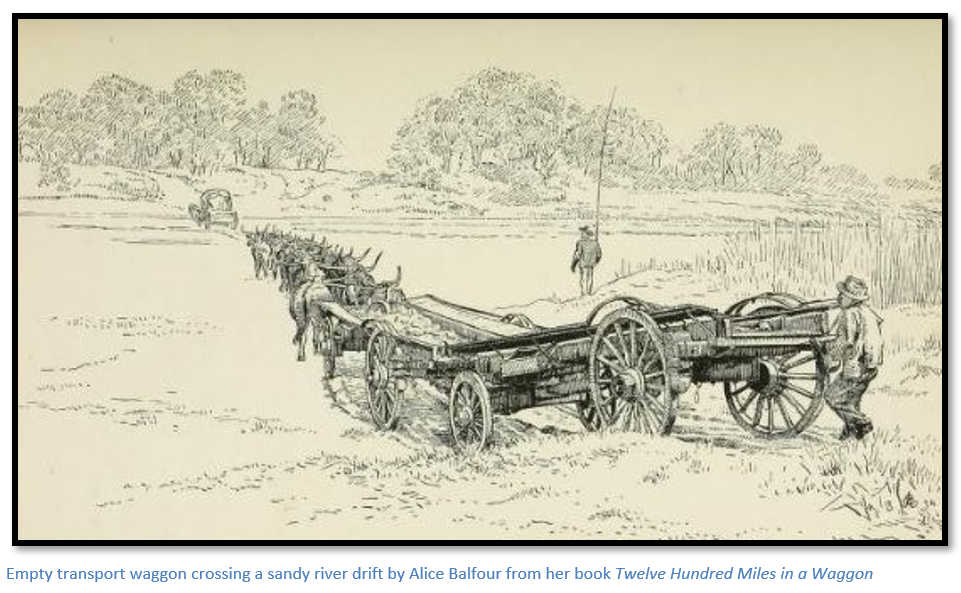

For the period 1890 to 1899 all traffic between Umtali and Salisbury was by ox-wagon mostly through the Devil’s Pass. The altitude at the highest point of the Pass is 1,446 metres, at its base it is 1,286 metres; so the oxen had to haul up their wagons 160 metres over a distance of 2.4 KM. This is a formidable gradient for a span of sixteen oxen harnessed in pairs drawing a wagon load of 4 to 5 tons.

A normal day’s travelling might be 16 KM, but this depended on the rivers and steep inclines that were encountered. At the bottom of the Devil’s Pass one or two teams would be detached from other wagons and each wagon would be double or triple-teamed in order to get to the top of the Pass. This meant that each team of oxen would make two or three trips and needed to be rested when all the wagons were finally up and meant only the 2.4 KM of the Devil’s Pass would be covered in a day. After overnight rain, the trail would be like grease and on these days there was nothing to do but wait for the road to dry.

Returning to Umtali down the Devil’s Pass was usually with a lightly-loaded wagon. They had large wood blocks on the rear wheels which were the brakes and were operated by a handle attached to a large turn screw. In addition to the driver and voorlooper, someone had to walk behind the wagon ready to apply the brakes at a moment’s notice to prevent the wagon from rolling over the oxen pulling it. Sometimes twelve of the oxen were moved to the back of the wagon, leaving four to steer the wagon while the remaining twelve held it back, helping the brakes and in the event of a runaway, reduced the number of casualties among the precious oxen.

The arrival of the railway which followed the watershed to the west was followed by the roads and so the old wagon route through the Devil’s Pass became abandoned and forgotten.

From Rusape take the A14 turnoff to Nyanga. Distances are from the turnoff; 7.5 KM pass on the left the turnoff to St Faith’s Mission, 17.9 KM turn right off the tarred road at the store. 18.2 KM turn right at the intersection heading for Mt Zonga in the distance. 20.5 KM take the left road at the intersection, heading due south, 22.9 KM take the right road at the intersection, now heading south west with Mount Zonga directly ahead. 27.5 KM turn left at the intersection away from Mount Zonga and heading for the Devil’s Pass ahead. 30.1 KM at the intersection turn left into the Devil’s Pass. See directions below for Fort Watts. 32.7 KM emerge from the Devil’s Pass, 33.9 KM continue directly on, 43.1 KM turn left at the intersection, 43.7 KM continue on the main road ignoring turnoffs and heading generally south. 56.1 KM reach intersection and continue on. 60 KM reach intersection and continue south. 66.2 KM reach intersection at Odzi Rapids Farm and continue south. 66.9 KM cross the Chingwandow River; 70.3 KM reach the A3 National Road and turn left for Mutare.

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass road north onto A14 near the business centre: 18⁰32′15.99″S 32⁰16′46.44″E

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass: 18⁰37′52.62″S 32⁰16′39.74″E

GPS ref (approximate) for Coach Stop, Inn and stables: 18⁰37′35.28″S 32⁰16′19.50″E

GPS ref for JB’s grave (approximate): 18⁰37′59.54″S 32⁰16′23.79″E

GPS ref for Fort Watt: 18⁰38′00.24″S 32⁰16′29.69″E

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass road south onto A3 near the Odzi River bridge: 18⁰54′51.08″S 32⁰24′05.22″E

This article is made up of the accounts of early travellers who used the road through the Devil’s Pass either on foot, or by wagon before 1900.

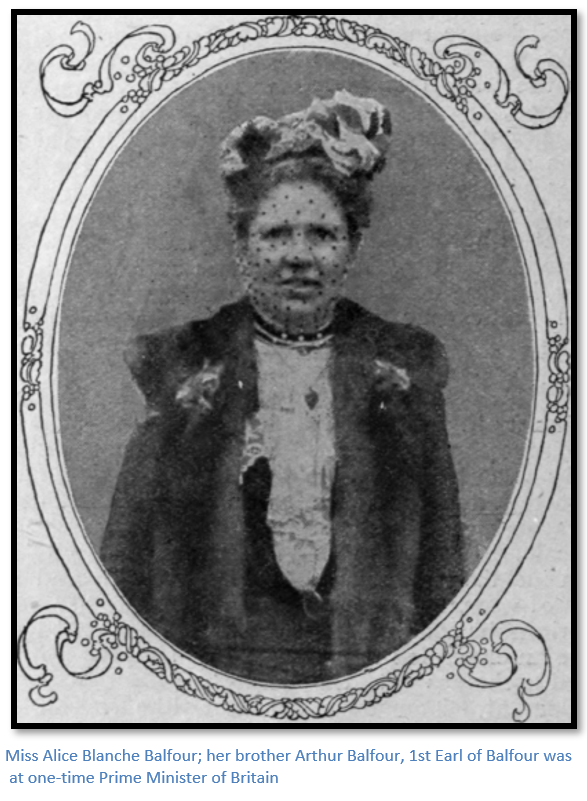

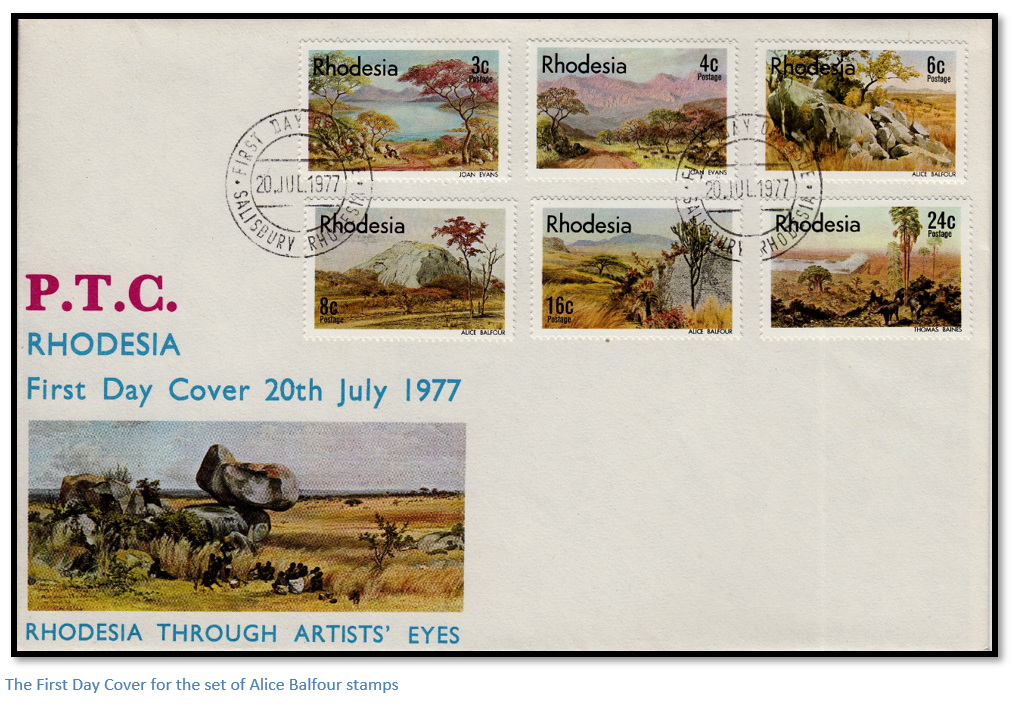

Alice Blanche Balfour who wrote “Twelve Hundred Miles in a Waggon”

Alice Balfour passed this way in 1894. The author and her friends, Mr and Mrs Albert Grey and Mr H. Fitzwilliam on their arrival at Cape Town, stayed for some days at Groot Schuur, and after a short trip which included Basutoland, Johannesburg, and Kimberley, started on their trek to the north. They were joined by George Grey who acted as their guide. Their wagons consisted of a second-hand buck-wagon for the stores and heavy luggage and two further waggons; one occupied by the three gentlemen and the other by the two ladies.

She describes the ladies’ wagon as about fourteen feet long and about six feet wide above the wheels. It is covered with a canvas tent over its whole length, but the roof is not quite high enough to allow her to stand upright inside and divided by a curtain about halfway along. At the front end are their beds, which lie parallel to the length of the wagon, and when down meet in the middle. They can be fastened up by day to the sides of the wagon if required. Under them are lockers and their boxes fill the floor in the middle. The wagon is lined with dark green cloth. The back end has small lockers along its sides with cushions on them to sit on. One gets out at the end by a high step, or when the oxen are outspanned (unharnessed) by a ladder, as the floor of the wagon is over four feet from the ground.

The journey through Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) appears to have been a great success, and the discomforts of early travelling in the new country were met with unvarying good-humour. There is an interesting account of the quarters occupied by Dr Jameson and Sir John Willoughby in the newly started township of Bulawayo; those gentlemen having put their habitations at the service of the ladies of the party, and there is a description of what existed of the town in those days. Great Zimbabwe was visited, and short trips were made to Victoria (now Masvingo) and Salisbury (now Harare), both in their infancy at this period. Many lion stories are related, although no lions were encountered, and Alice regretfully remarks; I have spent five months in the country without seeing lion, crocodile, or hippopotamus. What has been the use of coming to Africa?

In the section describing Devil’s Pass she says: Day after day as we went along we have heard the usual rumours of lion having killed oxen about a week before (it is always a week before!) and now they have at last proved true. We have been shown the exact spot where the lions were shot and have seen their skins and skulls. Mr Coope, who is engineering a new waggon road in the “Devil’s Pass” between Salisbury and here, is the principal hero of the story. A Dutchman had outspanned for the night on the road just below his hut, his oxen as usual fastened to the trek-chain, and a number of Mr Coope’s “boys” sleeping close by, when a lioness came up the road and seized the first living thing she came to, which luckily happened to be an ox, and not a “boy.”

The ox and the lioness rolled over together, and somehow the trek-chain got twisted around the body of the lioness and was held there by the rest of the oxen pulling hard in the opposite direction. The Dutchman fired at the lioness, and thereupon heard some others retreating, alarmed at the sound of the shot. Awakened by the noise, Mr Coope came down, and he and the transport rider arranged to sit up with their rifles for the rest of the night in case the lions should return.

Luckily, they did not do so, for morning broke to find both men lying fast asleep, their heads pillowed on the dead lioness. It was then that they found that she was twisted up so tightly in the trek-chain that she would have been squeezed to death if she had not been shot first. Mr Cope gave Mrs Grey the skull of this lioness. She was old and in very poor condition, with her teeth much worn, and had three porcupine quills in her, two stuck in her fore-paws, and one long one running upwards through her jaw and piercing her tongue. They had all made bad festering wounds, so that the poor beast must have suffered greatly.

The other lions went up to a neighbouring kopje, where they spent their time among the baboons, whose lives were thereby made a burden to them, if one may judge by the screams and yells which ensued for several days. After about a week another transport rider came past. He was warned that there were lions about, but took no heed, even allowing his oxen to wander loose all night to feed. This was too good an opportunity to be lost, and next day it was found that three had been killed by lions.

Mr Coope bought the carcases, removed two entirely, and left the third for the lions to come back to. He had a little shelter of branches and poles laid against a tree beside the remaining carcase, and inside this, he and his overseer, and the Dutchman watched for the reappearance of the lions. It was moonlight and after waiting for some time, Mr Coope saw the grass divide close to him and the head of a lioness appear and could hear the sound of her hungry grunts and the swish of her tail from side to side, as paused suspiciously and then retreated.

Mr Coope might have shot her, if he had not promised the first chance to the transport rider, whom he now found to be asleep! Presently the animal returned; he fired, and she disappeared without a sound, so he believed he had missed her. The smoke was hardly cleared away before he became aware that another lioness was close by on the other side. He fired again; a roar followed, and she also disappeared, and he could hear her moaning in the grass a little way off. At the same time a third lion bounded away into the bush. Next morning the first lioness was found shot through the head, and lying just where she had stood, about five yards off. The second had gone away about a mile and was there despatched. The third was no more seen.

The lioness’ skull which was given to Mrs Grey caused much excitement amongst our “boys” that night. Our outspan was at the foot of the pass, and most weird was the scene, - the waggons dimly visible amongst the tall trees in the hollow, and the blazing fire with the boys sitting around it like the Witches in Macbeth, eagerly scanning the skull as they handed it from one to the other with almost reverential gestures.

Then Alice spends a page or two telling another of Mr Coope’s adventures with lions which had taken place a few years before, before continuing: At the “Devil’s Pass” we met a man whose terrible experiences some two or three years ago have often been held over us “in terrorem” by Mr G. Grey when we did not show sufficient appreciation of the dangers of getting lost on the veldt. This man was travelling up country with a waggon and got lost on the veldt for forty-six days. During all this time he was without fire and without food, beyond what an unarmed man could procure. For days he had no water and was so tortured with thirst that he went into the reeds in hopes that wild beasts would devour him. At last he came to a small vlei, or pond, of stagnant water.

He lived upon the frogs which he caught in the vlei and ate raw and on roots and fruits that he could find; but they were so hard that his teeth became quite worn down by them. At night he crawled feet foremost into a deserted any-bear’s hole, blocking up the entrance after him with a bundle of dry grass. Thus, he existed until some Dutchmen happened to come across his spoor where he had worn a path to the vlei, and following it up, rescued him. He was almost mad with want and privation when they found him and could not give a coherent account of how he had lived all those awful weeks. He has now completely recovered.

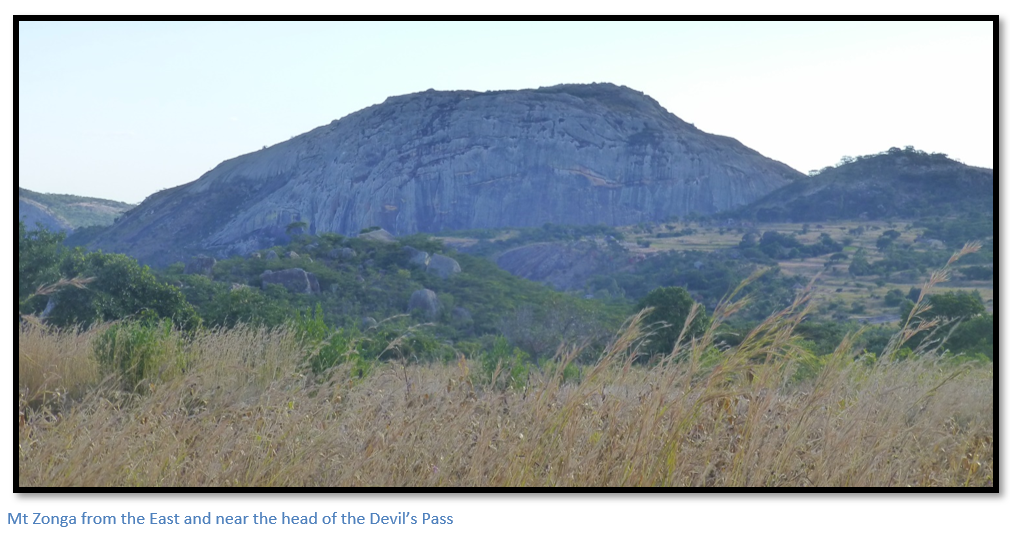

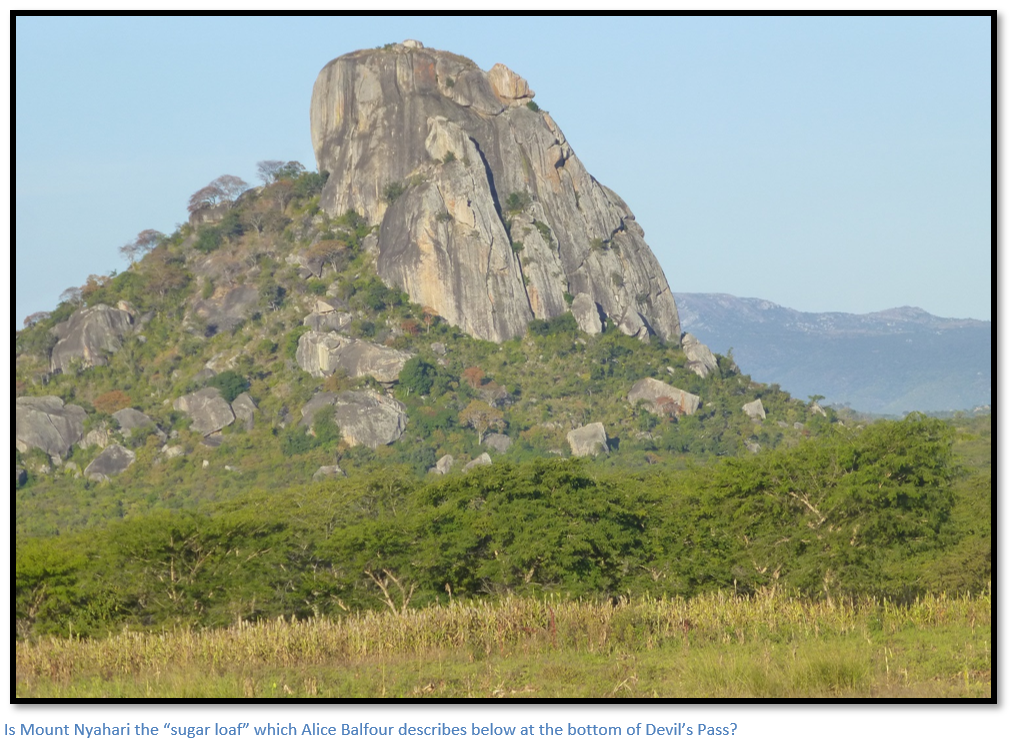

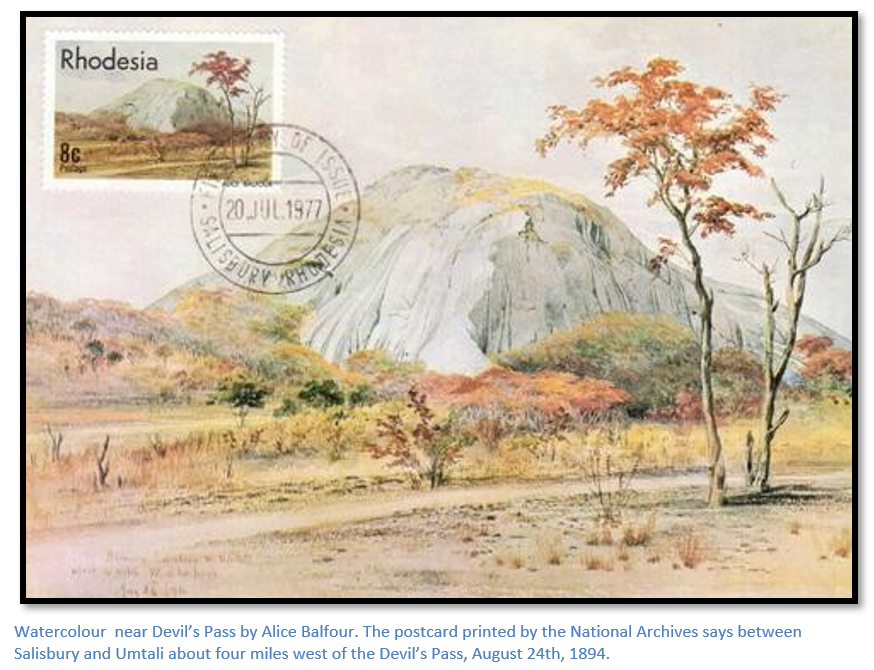

Next day we outspanned close to the “sugar loaf” a high-peaked hill looking as if made from one solid piece of granite. There are a good many hills of this type in this district, and as they are smooth and bare of vegetation, their delicate pale grey colour contrasts beautifully with the crimson and orange of the young leaves of the Magoussy trees, forests of which extend on every side. [F.C. Selous in A Hunter's Wanderings in Africa uses “goussy”, as in "a forest of goussy trees” but clearly, they are both referring to the Msasa tree, or Brachystegia spiciformis Benth]

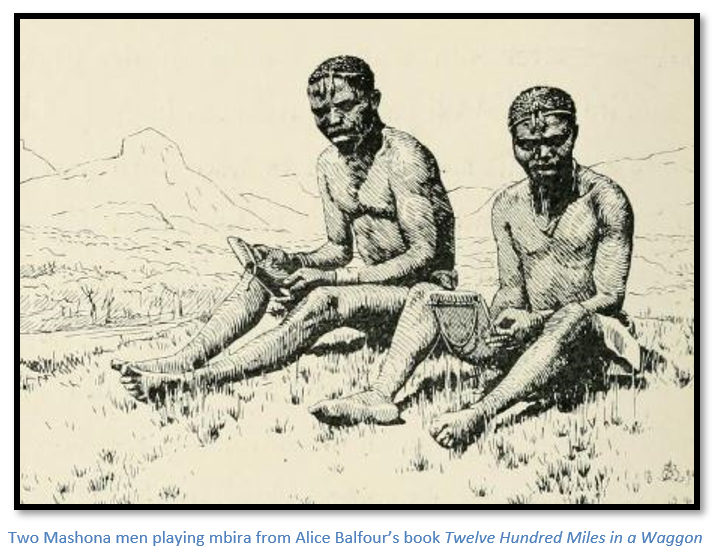

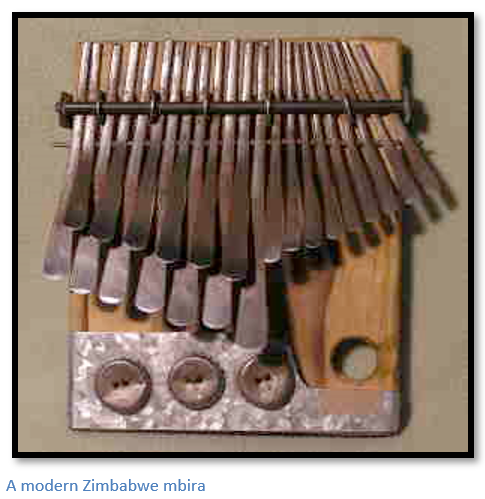

I spent most of the morning trying to note down the tunes played by two natives on their little metal-tongued pianos; but as they played extremely fast and could not be made to understand that we wanted to hear the tune played slowly, I did not make much of my well-intentioned efforts.

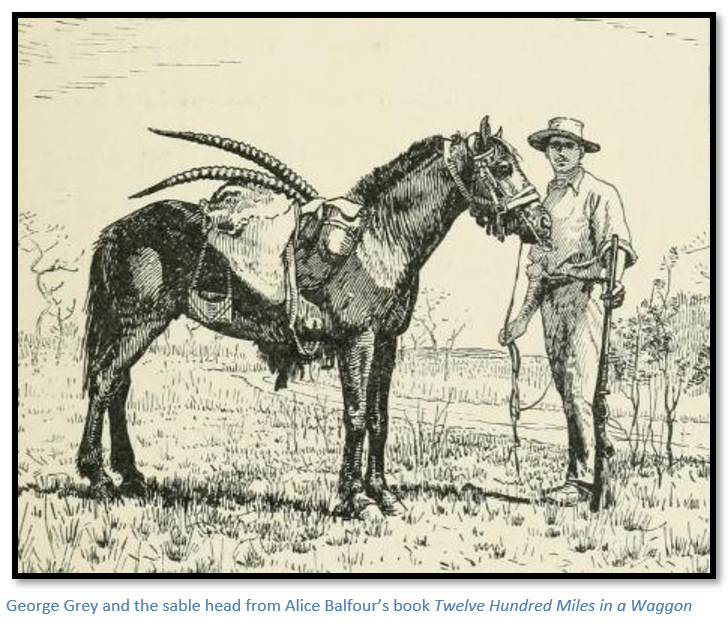

Before we left, Mr G. Grey brought home a fine sable antelope head on his pony (not forgetting part of the carcase to supply the larder) of which I got a good photograph.

At the Odzi River, about ten miles from Umtali [this is now Old Umtali Mission and not Mutare – described on the website as “Old Umtali – the second site”] we went on ahead of the waggons, leaving them to follow slowly. I think I enjoyed this ride more than any other I have had, for the views were so lovely, the hills ideally beautiful in shape, and their colouring of the rare and exquisite iridescent tints that one can only compare to rainbows and mother-of-pearl.

When we got here we found ourselves minus an abode to dwell in, but finally became the guests of the sisters at the hospital [see the website article describing “The Nurses Memorial”] which was luckily empty except for one “boy.” This poor fellow got into a tree to avoid a veldt fire, and it is supposed that he was stupefied by the smoke and fell down. At all events he was found afterwards lying on the ground so terribly burnt that he lost an eye, and both hands had to be amputated. This is the only case in which I have heard of anyone being injured by these fires. As a rule, they are very tame affairs, just a narrow line of flame running along the ground only a foot or two high. The grass burns so quickly that you do not see anything like a sheet of flame, and I have more than once walked across the advancing line of fire. As for the oxen and horses, they cross it with scarcely a glance, only giving a kick out if a flame happens for a moment to lick up their sides. When the grass is very luxuriant and the wind high, then it is a different matter, and I have seen a grassy kopje one mass of flames and smoke, even the trees blazing furiously.

From here the party split up. Miss Balfour having decided to return by the East Coast route through Beira and Mr Coope accompanied her down to the coast, but that is the subject of another article.

Alfred Arkell Hardwick

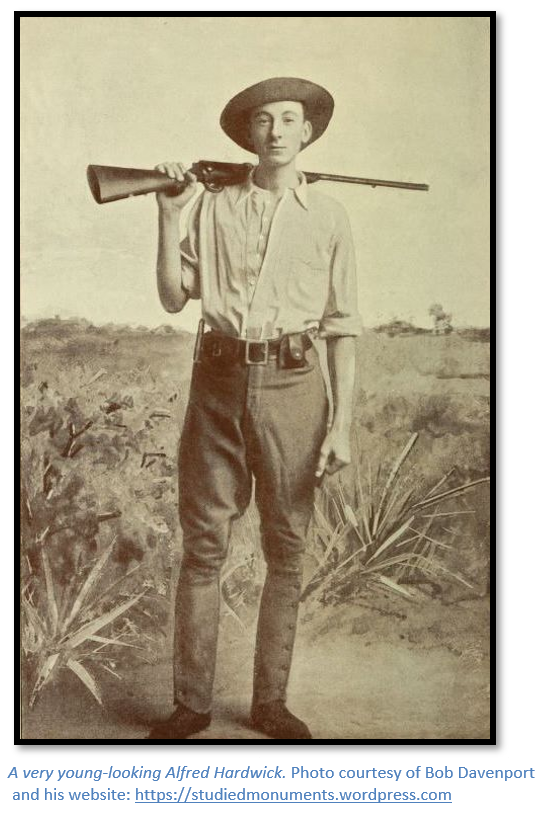

Another young adventurer in the early days who passed through the Devil’s Pass in 1897 was Alfred Hardwick shown below in a typical Edwardian pose in front of a professional photographer’s canvas backdrop.

Hardwick was born in Dalston, in north-east London, on 14 January 1878. When he was 14, he went to sea as an apprentice on an Australian liner and, according to his obituary, ‘spent three or four years knocking about the seven seas’ – surviving being washed overboard on one occasion – ‘and then turned up in Yokohama, and afterwards Beira and Cape Town’.

From Cape Town, he and a friend decided to head north to Bulawayo in present-day Zimbabwe, and enrolled into the British South African Police, and fought in the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga of 1896–7.

Hardwick’s commanding officer, Inspector (later Colonel) Colin Harding, wrote of him:

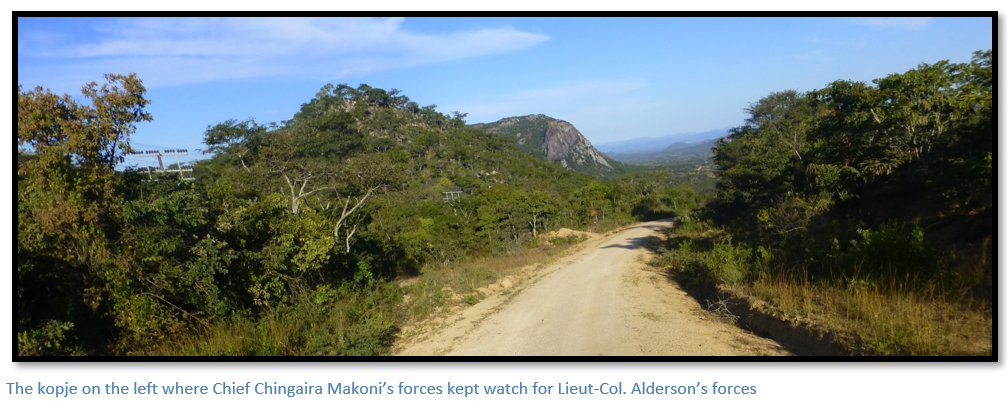

Hardwick was a typical Londoner, a type of man very hard to beat. He left a comfortable home in the North of London and joined the British South African Police, as he informed me to see life. I do not think he was disappointed, for everything he had to do, whether rough or smooth, he thoroughly enjoyed, and he was heard to exclaim to a fellow-trooper who was raving about the ‘Devil’s Pass,’ one of the most beautiful sights on the picturesque journey between Umtali and Salisbury [present-day Harare], ‘You may keep your “— view” but give me Hampstead!’ I have seen Hardwick clambering over a stockade far ahead of anyone else, and then with a captured Mashona gun much older than himself, return dirty and glorious to dream of fleeing Mashonas, in his service blanket under the starry canopy. A great lad was Hardwick.

Hardwick was wounded, mentioned in dispatches, and awarded a medal and a bar for his part in the campaign. [BSA Company medal with bar for 1896] He then worked on the railway being built to link Beira with Salisbury, before finding his way to Egypt, where he worked on the Nile boats and befriended an engineer in the irrigation department of the Egyptian government, George Henry West.

His Obituary which appeared in the Otautau Standard and Wallace County Chronicle, Volume VIII, Issue 404, 11 February 1913, details his colourful life as follows:

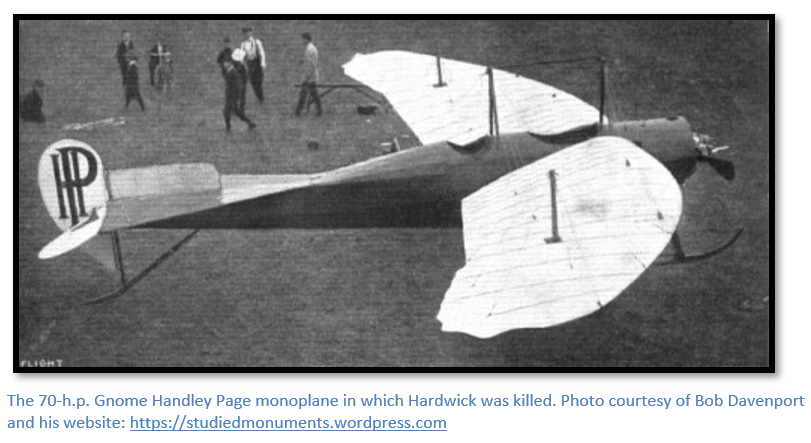

Two more victims were added to the death roll of aviation through a terrible accident which occurred at Wembley, near London, on December 15. Lieutenant Wilfrid Parke, R.N, of the Naval Wing of the Royal Flying Corps, attempted to fly from Hendon to Oxford on a Handley-Page monoplane just before noon on Sunday; Mr Hardwick, the manager of the Handley-Page Aeroplane Company, accompanying him as passenger. Fair weather conditions prevailed, although there was a somewhat choppy wind, but the journey was begun without mishap. The machine rose to a height of 150ft and appears to have steadily maintained that level until the disaster occurred. Apparently, everything went well, while the four or five miles separating Hendon and Wembley were covered, and members of the Wembley Golf Club who were playing on the course, and whose attention was attracted by the sound of the machine, state that the aeroplane was flying steadily as it approached. When nearing a clump of trees close to the 17th green, however, it became apparent the pilot was experiencing some difficulty in controlling the monoplane. The wind at the time was particularly gusty, and in the opinion of those who witnessed the accident it was Lieutenant Parke’s intention either to alight on the golf course, or to circle with the object of returning with the wind. At any rate, the machine began to descend gradually, and at the same time the pilot steered it round at a very sharp angle. Then, to the horror of the spectators, the monoplane, which was at a height generally estimated at from 80ft to 90ft suddenly turned over and dived nose first to the earth at a tremendous speed. When the eye-witnesses reached the spot to render any aid they could, they found that one of the unfortunate occupants of the aeroplane was already dead, while the other, although alive, was unconscious and terribly injured. It was only after considerable difficulty that the bodies were extricated from the wreckage, for owing to the construction of the machine, pilot and passenger were encased.

Lieutenant Parke, who was 28 to 30 years of age, figured prominently in the Army air trials on Salisbury plain last summer. There, too, he met with a bad accident. He had been seen frequently at Hendon on Sundays.

- A remarkable career –

Although only 34 years of age, Mr Alfred Arkell Hardwick, the other victim of the disaster, has had a remarkable career of adventure. Born near London, he went to sea as an apprentice on one of the Australian liners. He spent three or four years knocking about the seven seas, and then turned up in Yokohama, and afterwards Beira and Cape Town. At the Cape he and a friend decided to go up country to Buluwayo, to make their fortunes in the country which the Chartered Company [British South Africa Company] had just taken over. There Hardwick very soon drifted into the Mashonaland Police [British South Africa Police] He fought in the suppression of the Mashonaland revolt of 1896, and was wounded, and mentioned in despatches, and awarded a medal and bar [BSA Company medal with bar for 1896]

When the rebellion was over, he got employment on the Beira Railway. Next, he turned up in Egypt, where he worked on the Nile boats and in the general tidying up which followed Kitchener’s campaign.

In the Autumn of 1899 Hardwick started off on his travels again; this time with a friend named West, travelling up the Nile to Mombasa, and then by rail to Nairobi, where he met “El Hakim,” an Englishman, who was afterwards engaged in elephant hunting and had a prodigious reputation. His English name is not stated, but “El Hakim” means “the doctor” and it was known that he was a medical man in England until he abandoned civilisation for Equatorial. “El Hakim” was a man whom Hardwick declared he would follow anywhere, and the result of the meeting was that they set off for a year’s ivory trading in North Kenya – the almost unexplored country between Mount Kenya and southern Somaliland. An additional attraction to Hardwick was “El Hakim’s” proposal to visit the mysterious African Lake Lorain, which had been the subject of so much controversy.

The natives reported that it was a large lake; Mr William Astor Chandler, the American who reached it in 1892, reported that it was only a vast swamp. When Mr Hardwick and his companion reached it in 1900, they found neither lake, nor swamp. For disproving the existence of the lake, Hardwick received the right to add the letters F.R.G.S. to his name. On returning to England he lectured before the Royal Geographical Society, and published a most interesting book, “An Ivory Trader in North Kenia” in which he described his explorations.

His next trip was to West Africa on behalf of the “African World” examining mining and trading prospects. He went from Sierra Leone right down to the Congo and became interested incidentally in some West African trading ventures.

In 1907-8 he spent a year in Morocco with Mr Lawrence Harris and Mr Ashmead Bartlett, the war correspondent. There was a big scheme in hand for the recruiting of a force of European adventurers to maintain the pretensions of Muley Hafid to the Sultanate of Morocco, and Hardwick went up from Tangier to Fez, where he spent eight months, had many hair-breadth escapes of his life, and witnessed many of the horrible executions that marked the fall of the Shereefian Empire.

When this episode had closed this amazing soldier of the “Lost Legion” went off to America to help Dr Spratt, the American aviator, and in 1911 he was engaged in aviation experiments. He went back to London and joined Mr Handley Page, the inventor of the monoplane on which he met his death.

If you would like to read a fuller account of Alfred Hardwick’s life try Bob Davenport’s website: https://studiedmonuments.wordpress.com

Acknowledgments

H.C. Thomson. Rhodesia and Its Government. Smith Elder & Co. 1898

Umtali Boys High School 1973 Zuro Magazine P34

C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall. 1933

E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896. Books of Rhodesia. 1971

A. Balfour. Twelve Hundred Miles in a Waggon. Edward Arnold. 1895

https://studiedmonuments.wordpress.com/2016/04/27/alfred-arkell-hardwick-adventurer-and-sales-manager/ by Bob Davenport