Home >

Mashonaland East >

The story of a nurse and authoress travelling on the Selous Road through Mashonaland in 1896 during the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga

The story of a nurse and authoress travelling on the Selous Road through Mashonaland in 1896 during the Mashona Rebellion or First Chimurenga

Background

The title of the book relates to two of the most dramatic events in Southern Africa. The Jameson Raid at the end of December 1895 and the outbreak of the Matabele and Mashona Uprisings in 1896. Few people are associated with both events; but Elsa Goodwin Green as a trained nurse volunteered to assist the wounded at Doornkop with a spell at Krugersdorp hospital.

Later she travelled from Beira to nurse at Old Umtali and then travelled on the Selous Road in an ox-wagon convoy to Salisbury during the 1896 Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga.

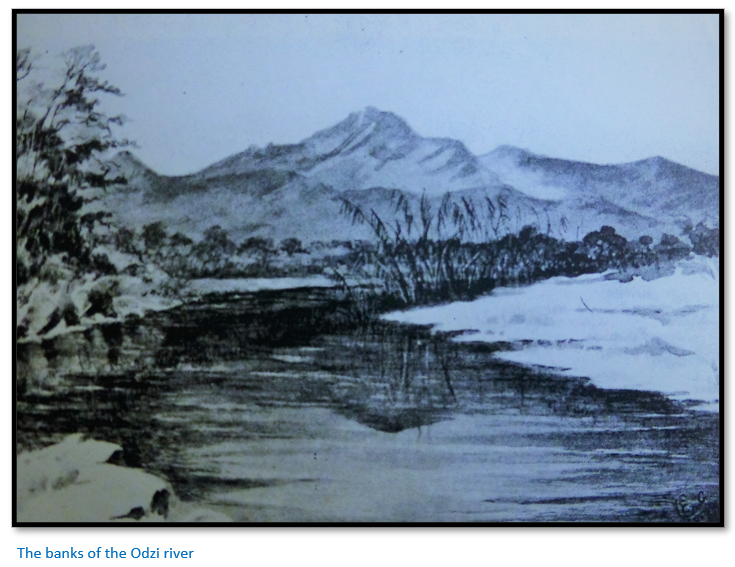

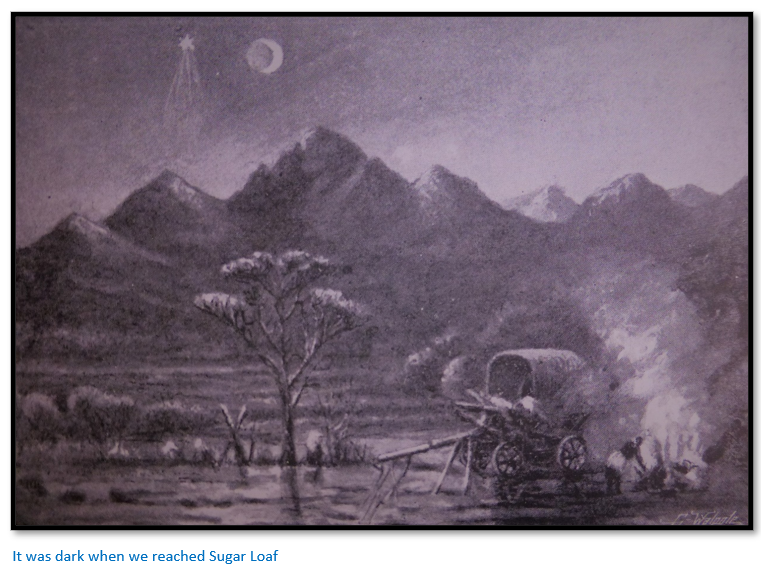

She graphically describes in her book Raiders and Rebels in South Africa the journey up the Devil’s Pass, the threat faced by travellers from Chief Chingaira Makoni until his stronghold was finally taken by military force, she recounts the narrow escape of those involved in the Mazoe Patrol, and the relief of Fort Hill in the Hartley district. As an artist, she made her own sketches which are illustrated in the article and copied from the black and white examples in her book.

Foreword to Raiders and Rebels in South Africa

W. D. Gale[i] wrote an extremely sympathetic foreword to the book saying despite the many spelling mistakes and the inaccuracies based on conversations with casual acquaintances who were woefully ignorant of Shona culture and often of earlier events in Mashonaland prior to 1896. He states Elsa Goodwin Green’s writing: “shines through on every page…warm and sympathetic, lively and inquisitive, intent on living each moment and each unfamiliar experience to the full. She must have been extremely good company.”

Gale used a copy of the book from the National Archives that had belonged to Lionel Cripps in which Cripps had made many notes and corrections and additional footnotes. Cripps had been attested into the Pioneer Column on 7 May 1890 as a Trooper and pegged the original Jumbo and Golden Quarry claims before being elected as the first Speaker of the Legislative Assembly from 1924 to 1935 and was a mine of information on the history and people of Mashonaland and Manicaland.

Both Cripps and Gale accepted that Elsa was not an historian, or a journalist used to check the facts, or the spellings of people she wrote about – but these defects are overcome by her courage volunteering for service as a nurse in the Transvaal in 1896 when feelings between Boer and Briton were running high and her adventurous spirit and ability to cope with the unexpected.

Leaving for South Africa

Her feelings of excitement on leaving Tilbury Dock on S.S. Bulawayo were identical to many travellers before and after: “Our spirits were not up to concert pitch, though we were bound for Africa, that land of promise, with its diamonds, gold, coal, and other mineral wealth, possessing a glorious flora, perhaps the richest found on the earth’s surface, whilst its’ varied and interesting fauna forms a veritable paradise yet for the sportsman and hunter of big game. It's hordes of dusky natives and great dark places, yet unexplored, have made the very name of the vast continent fascinating to many of us since early childhood. It is a name to conjure with, to those loving new scenes, which at least promise some adventures.”[ii]

Once they arrived in Cape Town: “the brilliant flowers and warm air made it difficult to realise how short a time had elapsed since we had shivered in the East wind and breathed a fog-laden atmosphere…” although the “Cape doctor” had its drawbacks: “when this wind blows, the mountain lays his tablecloth to warn his children not to venture from their more sheltered suburban homes into the discomfort of the windswept city.”

The Jameson Raid

There is no doubt that Elsa's sympathies lay with the British: “This rush of men with capital to the Rand meant undreamt of prosperity to the Boers, who found a ready market for horses, cattle and farm produce…Though the foreigner and his money were welcome to the Boer, yet he was persistently denied a voice in the government of the community - a vote even in matters most concerning himself - indeed, all rights as a citizen…A repressive legislation was persevered in, to prevent the still growing majority of newcomers from pre-dominating or participating in affairs of the Republican states.”[iii]

When the news came of Jameson and his raiders defeat at Doornkop, there was intense excitement throughout South Africa. “Crowds thronged the newspaper offices for the latest intelligence” and on 2 January 1896 an advertisement appeared in the Cape Times asking for volunteer certified nurses to go up to the Transvaal with Professor Liebman.

After a brief interview where the Professor accepted Elsa’s offer of help, they left the same evening. “I returned to my lodgings, made a few necessary additions to my nursing kit, paid a visit to the bank, telegraphed to my husband and joined the rest of the party at the Adderley Street station. The said telegram reached its destination [in Johannesburg] some days after I was already at work in the Transvaal. This will give some idea of the state of telegraphic communication at that time.”[iv]

At the Vaal river, the border between the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, a search party looked for arms and ammunition: “we were told to leave the train and were subjected to a severe personal scrutiny, even to the taking down of our coils of hair, that the searchers might be satisfied that no ammunition was concealed therein.”

They left the train at Pretoria. “Paul Kruger has been the President of the Republic since 1882. We drove past his house, which is a very unpretentious villa. His bodyguard of burgers were encamped on an open space before it, their wagons outspanned with the huge oxen grazing quietly nearby. But a scene of far greater interest to me was the camp, strongly guarded, whose tents had been temporarily set up to accommodate the prisoners who had been taken at Doornkop, amongst them Dr Jameson, whose name had thrilled every British heart in Cape Town when the news came of his defeat against such fearful odds."[v]

Next day they went to the military hospital at Krugersdorp where the wounded had been taken.

Krugersdorp Hospital

The hospital was actually a newly built store. “Never shall I forget the scene as I entered. The shaded lamp burned low, all was still, save for a low moan from one or two sleepless sufferers. The night nurse was on duty. She met us and with her finger on her lip to indicate quietness, ushered us into the ward. Her caution was needless for our hearts seemed to stand still as we surveyed the forty beds ranged round the ward. Many of the occupants looked like sixth-form boys at a public school, so young were they. Wounds and suffering had not yet had time to remove the healthy sunburn from their faces and hands.”

“A few hours’ sleep and then work commenced in the early morning. The store was large, new and clean. These wounded men were the first occupants. Their comfortable iron bedsteads were conveniently placed round the room and a double line down the centre head to head…Captain Barry and Raymond Philbrick lay in beds placed side by side in a quiet corner behind the screen. They were my constant care, as well as Sergeant Dreyer - whose leg was amputated - Troopers Palmer, Bruce and Rowley. Major Coventry was in great danger for some days the result of injuries from a bullet wound in the back…

…Five men died during the week of my stay - Burgher McDonald, a Boer, was one of these and also Lamb, Wild, Fraser and Captain Barry lingered 31 days after being fatally wounded on New Year's Day.”

The hospital was guarded night and day as the men were prisoners of the Transvaal Government. A rope barrier encircled it and armed Boers were stationed at various points. We had four convicts to ‘wash up’ for us and two guards to look after them.

The Braamfontein Explosion

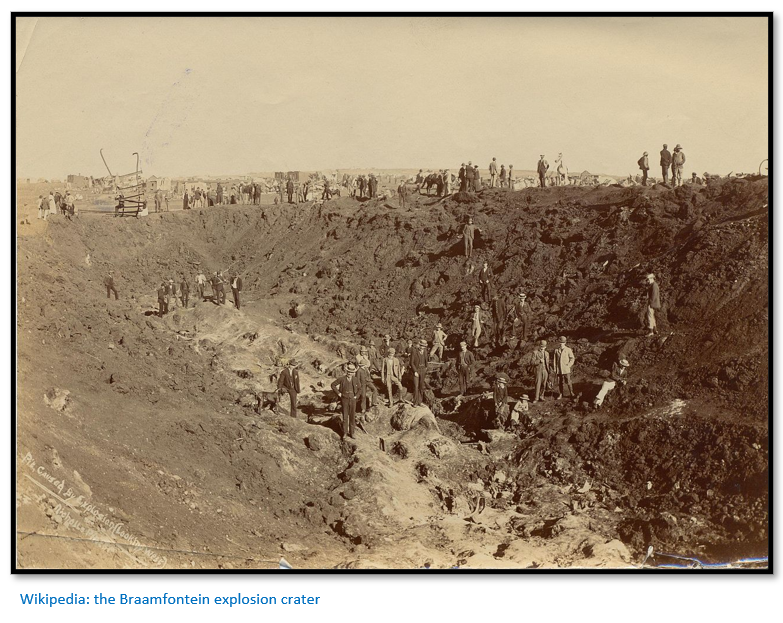

Elsa was back in Cape Town when on 16 February 1896, a freight train with eight trucks of dynamite – 2,300 cases of 60lb each, or about 60 tonnes - was put in a siding at Braamfontein railway station. The dynamite was destined for nearby mines, but the mine's stores of were already full to capacity, so the train was left in the siding - for days, in very hot weather - until there was somewhere to store the dynamite.

On the afternoon of 19 February, after labourers had started to unload the train, a shunter came to move it to another part of the siding; but with the impact of the shunter, the dynamite exploded. The explosion left a crater 60 metres long, 50 metres wide and 8 metres deep and was heard up to 200 kilometres away; it is thought that over 70 people were killed and more than 200 injured.[vi]

Elsa wanted to volunteer and nurse the wounded at Braamfontein, but she was suffering from blood-poisoning and was unable to travel. In her book she names it as Fordsburg; but Fordsburg was a nearby residential suburb where many homes were destroyed by the explosion and women and children killed by falling debris.

Matabeleland and Mashonaland Uprisings

First Elsa records the Matabele Rebellion or Umvukela. “The civilised world was startled by news of the murder and mutilation of whole families and isolated white men.”[vii]

Her explanation for the uprising in late March 1896 follows the popular stories in the newspapers of the time; the absence of most of the British South Africa Company Police and the death of the amaNdebele cattle to rinderpest being blamed on the coming of Europeans.

She volunteered her services to the British South Africa (BSA) Company but was told they weren’t needed at the time. She then quotes an article from the Rhodesian Times and Financial News of the influence of the spirit-mediums on the Mashona people: “…quite recently Chimororo [Chief Chinamhora] sent to consult a very famous female witch-doctor, who resides in the Mazoe Valley and whose name is given variously as Zahanda or Nanaanda [Nehanda] This lady is the acknowledged head of the witch-doctors [spirit-mediums] in Mashonaland and her reply to Chimororo was that if the Mashonas did not wipe out the whites, the whites would wipe them out. She promised her assistance in the shape of a great snake with ten heads from each of whose mouths fire would be poured upon the white men and another of her inconsidered trifles in the way of pledges was to the effect that the rain of lead from the Maxim gun should be turned to a rain of water.”[viii]

Elsa then received a telegram from the BSA Company asking if she would go next day to Rhodesia to which she agreed and boarded a train to East London where she was joined by Professor Liebman, two doctors and two other nurses. The Professor and one nurse then returned to Cape Town leaving the others to board the Union Castle liner S.S. Norman for Durban.

Inside the bar at Durban a little tug drew up alongside the S.S. Norman and Elsa was lowered by a crane onto its deck in a bell-shaped basket with a door on its side that held two passengers at a time. When one safely landed, it is some amusement to look over the taffrail and watch the other passengers passing through the same ordeal. Soon the troopship Inyoni arrived which had been chartered by the BSA Company. Then followed a wait whilst permission was awaited from the Portuguese to land troops at Beira. On board were five officers and one hundred and fifty men of the West Riding Regiment with six medical staff regulars and the volunteers party of Nurse Stanton and Nurse Goodwin Green with two doctors.

Within a few days they entered the wide mouth of the Pungwe river and Beira lay before them in brilliant sunshine. They stayed at the Royal hotel; at the back of the hotel was a large square garden, rows of rooms with a wide stoep (veranda) enclosed it on three sides, one side reserved for the accommodation of ladies and the opposite for men. Meals were arranged here as they are in India. Toast and tea in one’s room and tiffin at 11am.

The journey continues by rail

The officers of the West Riding Regiment with some of the men proceeded up the Pungwe river in the tug S.S. Kimberley whilst the horses were towed behind in lighters. Finally, it was arranged for the volunteers to accompany one of the BSA Company’s engineers by rail up to Fontesvilla, the highest navigable point of the Pungwe. They travelled in a truck covered with a tarpaulin as it had rained heavily and, on the way, saw magnificent flowers, ferns and tropical foliage as well as a herd of buffalo and zebra.

The bridge over the Pungwe was not yet constructed, so they were physically carried over a very unwholesome looking black mud to their ferry boat and greeted on the opposite bank by members of the West Riding Regiment that had gone upriver a few days before. Elsa’s most vivid recollection of Fontesvilla was a rat, almost as big as a rabbit, which she threw off whilst in bed. “It fell squealing to the floor.”[ix] For an article on the Beira Mashonaland Railway see The Beira and Mashonaland Railway, the Contractor’s stories under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

They left Fontesvilla next day for Chimoio at 6:30am in a cattle truck with a garden seat on either side. A case of medicines and surgical instruments in the centre served as a dining-table. The journey of 190 kms (118 miles) normally took two days but was done in one day and Elsa remarks on the lovely scenery. The spectacular colours of the Erythrina caffra and the tree ferns really captured her imagination.

Major Boucicault and Elsa had their backs to the locomotive and benefited greatly. “For a while all went well with our opposite neighbours, the air was pleasant, not too strong and the sparks from the wood fires in the engine were wafted away on the breeze.”

At 40-mile spruit (i.e., 40 miles from Fontesvilla) they had a picnic lunch of soup, ox-tongue, tea, biscuits and jam. The stop had a telegraph office manned by an Englishman who lived alone and invited them into his house for a ‘wash and brush up.’

At the 62-mile stop they bought eggs which were boiled for afternoon tea. For other stories of travel on the Beira and Mashonaland Railway see the article Mary Blackwood Lewis’s letters on her journey to Mashonaland from Beira 1897 – 1901 under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

At 72-mile stop was the Railway hospital with a fine view over the hills which they left at sunset. They passed out of the forested areas into grasslands dotted with tall palms and Aloe Bainesii, now Aloidendron barberae.

It was dark when they reached 80-mile spruit where they stayed in a hotel built upon piles with the rooms, which were pole and dhaka huts, below. The furniture in each consisted of two small wooden stretcher beds, a rough washstand and a packing case with a small mirror. While the nurses freshened themselves up, they saw a snake in the wall which glided away and congratulated each other they were not sleeping the night here! The hotel owner said a few nights before a native had been savaged by a lion which put its paw through a calico-covered window.

The railway terminates at Chimoio

Elsa writes: “the engine snorted and screamed and once more we were on our way. The sparks from the wood fire in the furnace fell in a golden shower now on this side, now on that, sometimes we seemed enveloped in them. They danced and played about our truck like so many fireflies…It was now intensely cold. Rugs and my kaross were unstrapped and preparations made for comfort during the remaining hours to be passed before we could reach our destination. We on our side were warm and sheltered from the sparks, but our opposite neighbours were kept busy all the time in keeping their rugs and wraps from being burned by them.”

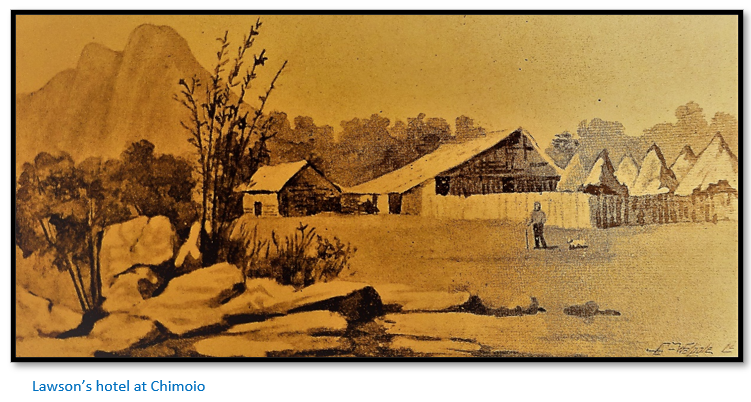

In the small hours of the morning, they reached Chimoio and Lawson’s Hotel, where they were expected, and soldiers helped them with the luggage. Again, the rooms were pole and dhaka huts. “Two packing cases, japanned washstand ware, two wooden stretcher beds with a piece of sacking laid on the mud floor completed our furniture. A calico-covered aperture served as usual as a window. The door was made of old packing cases on which we read ‘keep the contents cool.”[x]

With daylight they explored Chimoio but could not find anything that resembled a street, “the smell of the swamp lying in the vicinity was most objectionable, although not quite so bad as at Fontesvilla.”

“…we met many victims of the terrible fever. Men who looked as if they had not a drop of red blood in their bodies with skin like yellow parchment, shaking hands and wasted strength.”

“…an extensive belt of [tsetse] fly country lies between Fontesvilla and Chimoio. Horses are placed in horseboxes which have a fly-proof wire covering every aperture. They are then sent as rapidly through as possible. Perhaps worse than the fly is the disease known as horse-sickness [dikkop] He is liable to this during and after the rains. Should he have it and recover, he is termed a salted horse and commands a much higher price inconsequence, for he is unlikely to have a second attack, though this occasionally happens.”

The railway had only been constructed as far as Chimoio’s and whilst they waited for the Umtali coach many of the officers and men of the West Riding Regiment arrived and then begun their march to Umtali…the Umtali coach passed them on their first halt.

Travel by coach from Chimoio to Old Umtali

The first stop on the coach was Vendusi [now Nova Vanduzi] where the coach was delayed for some time as two mules strayed.

“the coaching we did not very much enjoy. It is most fatiguing to be packed into a small space and to be bumped over a fearful road in heat and dust; the latter is particularly trying, engendering excessive thirst. The coaches are drawn by fourteen mules. It is driven down dongas[xi] almost as steep as the roof of a house, across rivers and up the opposite bank at a like speed, unless the coach sticks in the river drift, which is not an uncommon experience. In that case it frequently necessitates waiting till a fresh span of mules can be got to help them out of their difficulties. Then on again we bump over stones, tree stumps and water courses; it is wonderful how a coach escapes being overturned during any journey.”[xii]

The next stopping place was Revue river. “Here we were to spend the night. The little compound with its mud huts lies encircled with dense thicket and jungle grass; inside the enclosure grow tree-ferns and tall bananas. We were expected and a grand wood fire delighted us. We shared its warmth with three or four beautiful dogs; their master appeared to be proud and fond of them. The walls of the room in which we supped were hung with skins of animals and decorated with horns of springbok, waterbuck, reedbuck and duiker, showing our host to be adept in the use of a gun.”

…Our sleep was short for we started again at 4am, getting well on the next stage of the journey before the heat of the day.

The moon waned and set, dawn brightened into day and noon brought us to Massi Kessi [Macequece, now Manica] “…The Portuguese Commandant resides here, and incoming goods are examined by the Customs House officials…An excellent lunch was served to us at this place.”

“The following night we stopped for dinner and a few hours’ rest at Brown’s store. We were to start again as soon as the moon rose…we were told that almost every night of late the lions had been about the mule stable.”

“All along the route we saw dead or dying oxen, victims of the terrible rinderpest which was depleting the land of its most valuable means of transport. These rotting oxen on the road - sometimes covered with evil looking vultures - were a source of danger to ox teams passing on their way to Salisbury from the coast.”[xiii]

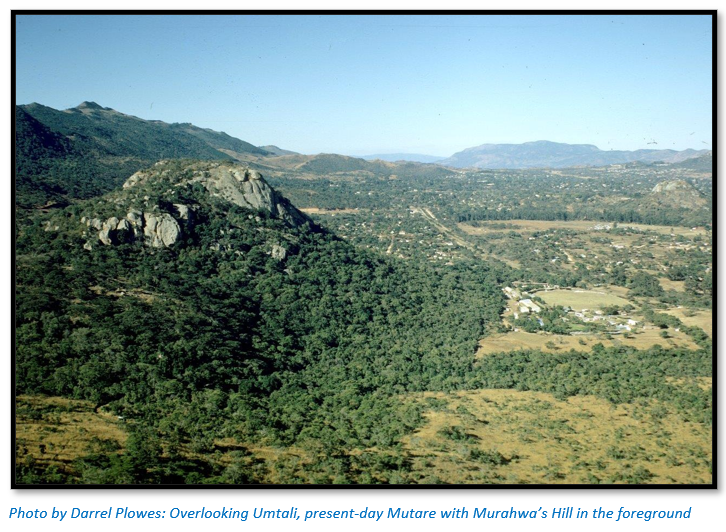

Our next outspan was at Umtali new township [present-day Mutare] Our orderlies made tea and we breakfasted on the open veldt. Meanwhile I sketched this site which was being laid out for the new town.”

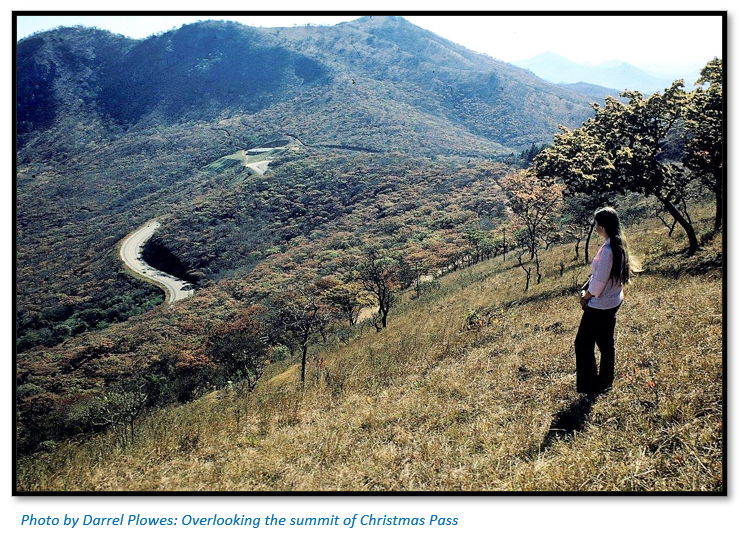

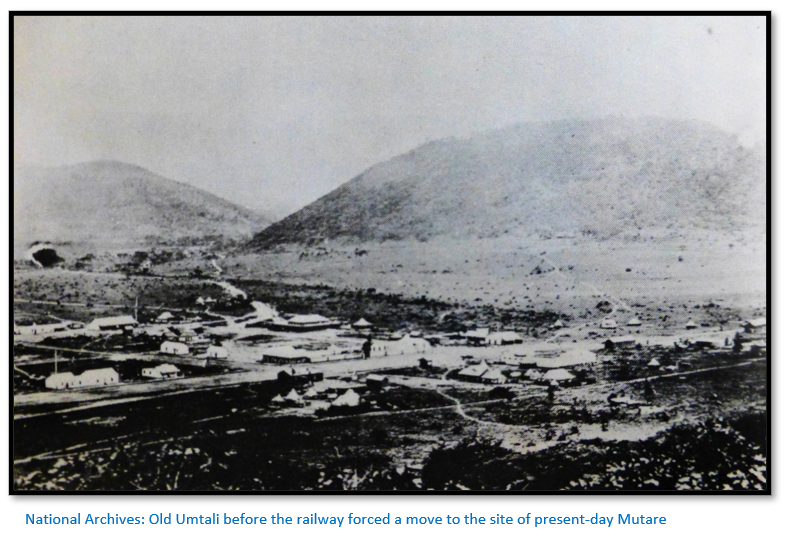

The town of Umtali [Old Umtali] was then situated 4 miles beyond the head of the [Christmas] Pass and about 18 or 20 miles from the proposed site [of present-day Mutare] The cost of engineering the line, so that it might touch the town where it then stood would be too great, for it presented many physical difficulties. It was therefore decided to remove the town itself. For since the line cannot go to [Old] Umtali, Umtali must come to the line.[xiv]

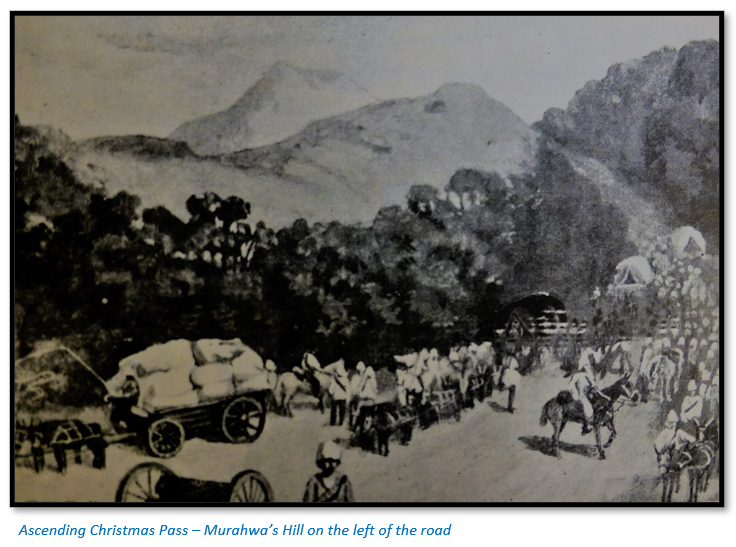

We started once more on the last stage of our journey by the coach. We had only proceeded a short distance when we saw wagons with mule spans, long trains of donkeys drawing guns on carriages, mounted men and foot soldiers, with all the paraphernalia of a column of Her Majesty's troops on the march. We learned that they were the Mounted Infantry Regiment and soon overtook them.

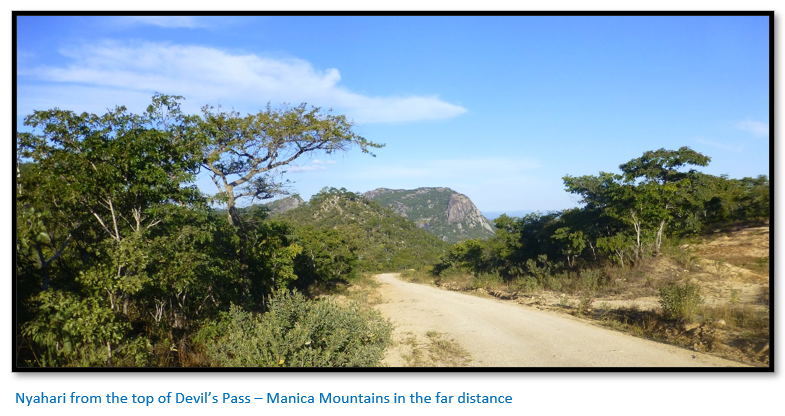

We left the coach to walk up the pass; the scenery is rugged and grand. Mountains rise on either side, lifting great granite boulders and jagged points high into the sky. Flowering trees with rich green foliage creep far up the slopes. Between the spurs of the mountain range, beautiful glimpses of the valley beneath are afforded to the traveller climbing this magnificent pass.

At midday we dashed into [Old] Umtali. Our driver had evidently spared his mules for this finale. We were ardently looked for as we carried Her Majesty's mails.

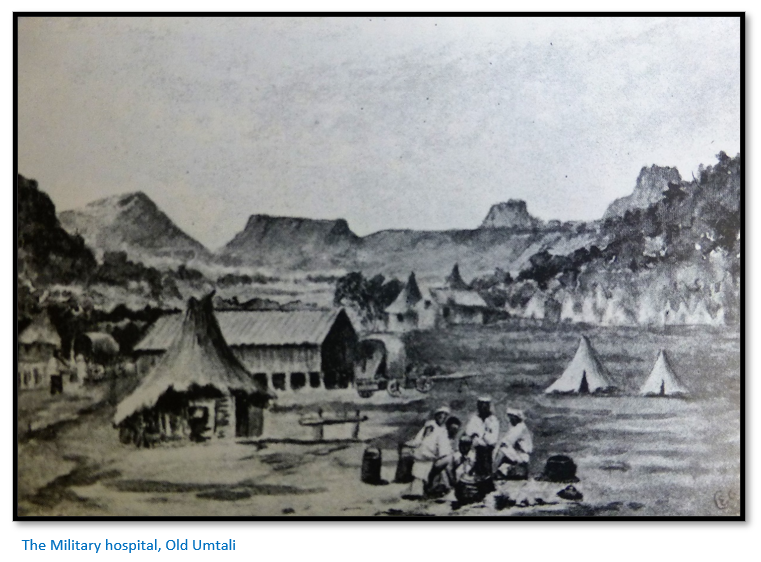

The Military Hospital at Old Umtali

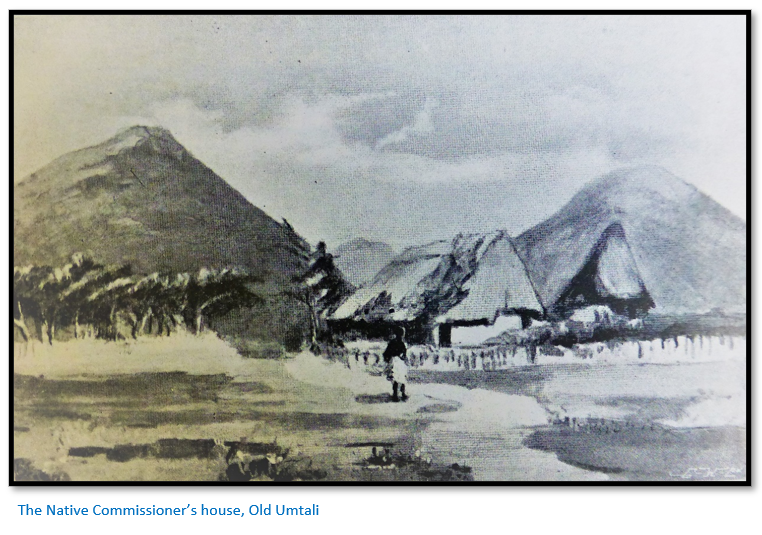

The Masonic hotel is the only building of two storeys in the township, but there are a few others built of brick - the bank, courthouse and prison. Most of the private dwellings consist of three or four mud huts, roofed with thatch. These can really be made very pretty and comfortable habitations.

When we first saw [Old] Umtali, all places of any size were in a laager formed of sacks of earth, branches of trees and thorn-bushes, with ox-wagons to further strengthen it…a very strong laager with an addition of a barbed wire entanglement was constructed round the courthouse and gaol in the market square. A seven-pound gun further defended it. The firing of this gun was to be the signal for everyone to fly to laager in the prison.

[Old] Umtali was full of refugees from outlying districts which were not considered safe, since brutal murders had been perpetrated by natives upon the white settlers in lonely out-of-the-way places in Mashonaland. These had taken place only a short time before. It was feared at this time that several of the powerful native Chiefs were only waiting a fitting opportunity to rebel. [the authoress refers to Chiefs Makoni and Mutasa]

The nursing sisters…with their patients, were located in the gaol; four nurses having to sleep in one of the larger cells with a brick floor, while their patients were accommodated in the largest room. The courtyard was provided with canvas shelters and tents to accommodate the townsfolk should occasion rise. One lady had a baby born in a prison cell during the time it was necessary to keep up a laager.

For more information see the article Old Umtali – the second site under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The Mounted Infantry attack Chief Chingaira Makoni’s stronghold

We were told by Mr Sawerthal, the Chartered Company’s agent, that a wagon was being prepared for us in which we were to travel to Salisbury with the mounted infantry and Colonel Alderson’s column. This however did not come to pass.

Colonel Alderson decided to attack Makoni’s kraal at the top of Devil’s Pass about 40 miles from Umtali. This powerful chief had been giving much trouble to the country. Several murders in the Salisbury and Umtali districts had been distinctly traced to his people. This part of the road was swarming with hostile natives. Colonel Alderson therefore considered the risk of taking us too great, particularly as should he form a hospital on the road he could not, for the present, spare sufficient men to guard it. His plan was to attack Makoni and pass on to Salisbury.

So, we were to stay. A base hospital was to be formed and sick and wounded sent to us. A large, galvanised iron store was utilised for this purpose. It was soon made very comfortable for the men and our enforced idleness bade fair to come to an end at last...The ward was a good-sized room having a wood floor. Little stretcher beds were conveniently arranged around the wall-space; bright red blankets covered them, giving a cheerful aspect to the somewhat sober appearance of the room. There was no window, but a large double door admitted light and air…A few small tables and a large four-fold screen completed our furniture. The wide open door framed an ever-changing, enchanting picture of wide open space covered with short brownish grass, blue and yellow flowers. Beyond were the purple Umtali hills of rugged outline, against which in the middle distance, gleamed in high relief the white tents and red coats of the West Riding Regiment, encamped on the open. Our patients were able to lie and watch the far-off movements of their more fortunate comrades. Sometimes a procession of friendly natives, driving goats, wended its way swiftly and silently, as in a panoramic picture across the field of vision.

Their first patient was Col. Alderson’s servant, Jenkins, who was accidently shot with his own revolver and subsequently died.

The account of the Mounted Infantry’s attack was placed on the door of the courthouse, but is not repeated here, but for a detailed account see Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Social events at Old Umtali

Being totally cut off as the telegraph line had been cut all sorts of rumours went around…a man arrived with a Durban newspaper saying Old Umtali had been wiped out. Elsa writes: “what would our anxious friends have thought had they seen us on Aug 6 enjoying a musical evening given by Mr and Mrs Moody [Moodie] at Mr Piggott’s [Pickett] pretty house on the slope of the hill near the town. We were strictly under martial law in Umtali. On our return from the dance, we were a large party, some carrying lanterns to light us over the veldt. We were met by the pickets who challenged us saying, ‘who goes there?’ We gave the word, fortunately someone had been careful to ascertain it and were answered by, “Friends, pass on."[xv]

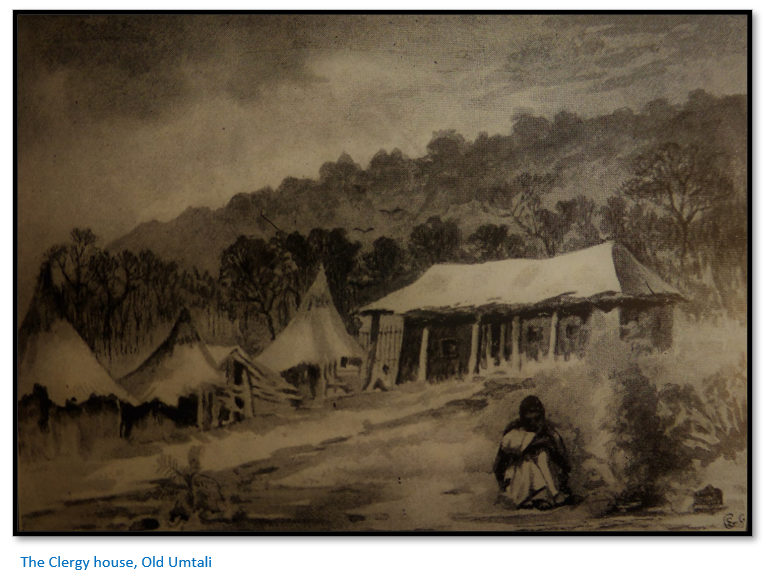

One very interesting event took place in Umtali on the 10th of August. Sister Emily Hewett [Hewitt] was married to Mr Herbert Blatch of Massi Kessi. [Macequece, now Manica] Miss Hewett [Hewitt] was one of the two sisters who followed the nurses first placed in the Mission hospital by Bishop Knight Bruce. She was now the matron and had endeared herself to the people of Umtali during the three years of her arduous work amongst them. See the article Nurses Memorial under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

It was a pretty wedding. The whole of Umtali seemed gathered together in the little church, including the dogs of the town, which were numerous and enterprising. The little cart belonging to the Sisters, usually drawn by the eccentric and historic donkeys Powder and Pills,[xvi] stood at the church door, but in the place of the animals, the gun squad men were drawn up in a line and they conducted them to the Masonic Hotel.

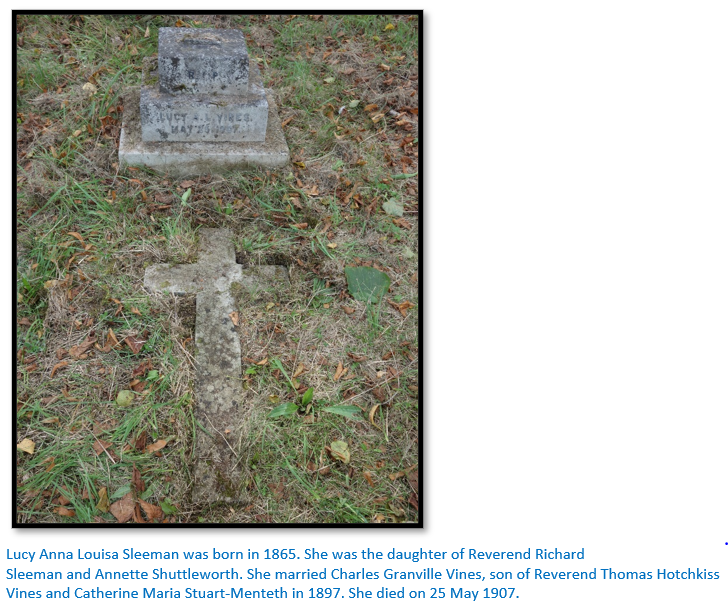

Lucy Anna Louisa Sleeman, one of the three original nurses is buried at Penhalonga Church.

Major Watts to fortify Devil’s Pass

Major Watt's column arrived at this time with about 50 men. It had come through from Bulawayo. Many of the men came to us with veldt sores on hands and face caused by the long hot march and diet of tinned foods and absence of fresh milk. We learned that it was Major Watt's intention to build a fort in the Devil’s Pass.

A visit to Penhalonga Mine

Mrs Jefferies with her husband had been staying sometime at the Masonic Hotel. Their home at Penhalonga Mine had not been considered safe since the first rising of the Mashonas. We had already had some delightful rides and they wished to take me out to see the mine at Penhalonga. The day was fixed for the expedition. It was very fine, but hot, almost close and sultry. Mr and Mrs Jefferies, Mrs Stockley and myself with Mr Meikle and Mr Taberer[xvii] made up the party.

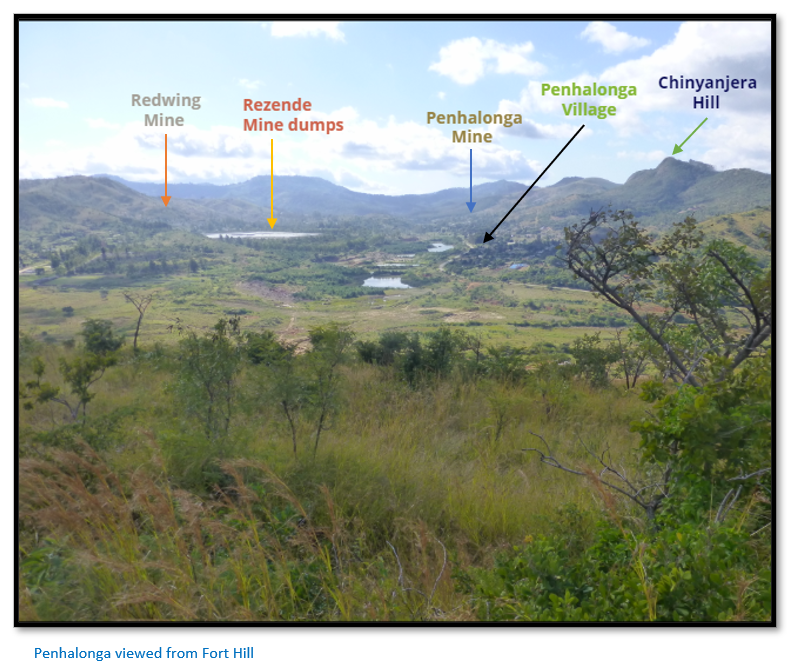

Our horses were good and the country beautiful. We went through some very fine scenery in the rugged passes between the mountains which entirely surrounded Umtali. In one place we forded the Umtali river near its junction with another stream [the Sambi or Mbeza] …after about 2 hours riding, we arrived at the little township of Penhalonga. It is a collection of huts with a house or two situated at the foot of a lofty mountain which is green far up the slope and then surmounted by granite pinnacles. [Chinyanjera]![]()

![]()

![]() `

`

We were received by Mr Hillary at the gate of his pretty thatched cottage which was covered with the granadilla vine…Our six horses were fastened to the bridle pole, which is fixed for the purpose in front of most dwellings and stalls…Lunch was followed by a rest, then we re- mounted for our ride to the mine.

It is situated about 2 1/2 miles from the township. Our road now lay along a bridle-path, which was only wide enough for us to proceed in Indian file. A precipitous mountain rose [Chinyanjera] on the right, while a deep valley lay on the left below forming a channel for the rivulet, which in the rains became a foaming river.

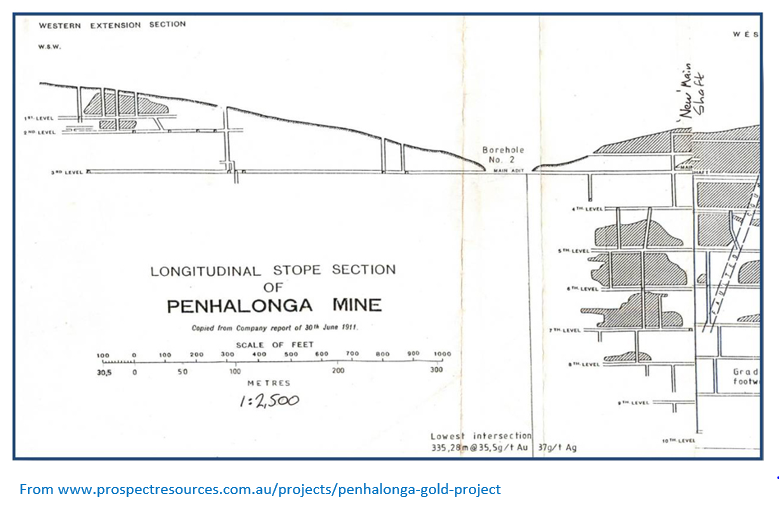

Penhalonga is one of the Mashonaland [Manicaland] mines which was worked by the ancients and again in more recent times by a Portuguese from whom the name is derived. The strata has been worked near the surface and the gold taken out. Having neither machinery nor appliances to work to a greater depth these gold seekers have left a heritage for their successors. It is believed that the reef is rich in gold. A horizontal drive [adit] has been carried more than a thousand feet into the mountain at the time of our visit. A truck line was constructed to the end. [narrow gauge rails for hauling ore]

For more details see the article Penhalonga under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The miners were not then at work, so a procession was formed, a candle lighted, and placed in the hand of each and we proceeded to explore the mine. At one spot in the long subterranean gallery a particularly rich archway of reef was pointed out; here gold was visible, shining in our taper’s light. A five-stamp battery was in the process of erection for the treatment of the gold-bearing quartz. It was nearer to the township of Penhalonga, the water from the stream being utilised for motive power. This has since been started and is, I believe, the pioneer battery in Manicaland.

We were received back at the Masonic hotel by the dogs of the town, who as usual assembled to see us dismount. They had watched us depart and greeted our return vociferously. Several of these animals insisted on attending the service at the church, where they certainly behaved well, causing no distraction even amongst the juvenile portion of the congregation.[xviii]

The defeat and execution of Chief Chingaira Makoni

Elsa’s Chapter 10 description of Major Watts’ assault on Chief Chingaira Makoni is included in the more relevant article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

She writes: This chief was still a terror and menace to travellers and troops on the road at the top of - and on the road above - the Devil’s Pass. Although the main body of Makoni’s men were still ambushed in the caves to which they had retired when attacked by Colonel Alderson, yet from time to time parties of natives were sent out to the head of the path to reconnoitre and straight shots were fired at horsemen and transports on the road.

The capture and execution of this chief had an immediate and beneficial effect upon the neighbouring chiefs, particularly upon Chief Mutasa, who had a long refused to come into Umtali. This he should have done when he was summoned by the Chief Native Commissioner for Mashonaland, Mr Taberer. It was believed that he only awaited events and Makoni’s kraal to breakout into open rebellion himself, had Chief Makoni been successful in resisting the Imperial forces.[xix]

Races and Sports in Old Umtali

Umtali is a wonderful place for wedding bells. About a month after Sister Emily Hewitt was married, Sister Mary (Miss Saunders) was married to Captain Randolph Nesbit [Nesbitt] of the Mashonaland Mounted Police (MMP) He was the leader of the relief party known as the Mazoe Patrol…he has since received the Victoria Cross. After their marriage the happy couple were to go to Salisbury and would spend their honeymoon in a wagon trip north…then Captain Nesbit [Nesbitt] came in quite unexpectedly, saying he just had a telegram which altered all their plans. He had been appointed inspector of the MMP and was to make Umtali his headquarters. This was good news, but he could only take a fortnight's holiday which was to start at once, so matters were hurried up and they were married next day, but one.

Certainly, Umtali proved itself a gay little place during my stay there. Besides four weddings and receptions, there were musical evenings and races, with cricket matches and tennis tournaments in the afternoons. The troops - officers and men - of the Imperial forces, as well as the Umtali volunteers, took part in the sports and races. Tent pegging and the Victoria Cross race excited much interest and mirth. At the latter the sack tied up in the middle represented the wounded comrade to be snatched from some impending danger.

Towards the end of September 1896, the military hospital at Umtali was closed. The patients, with one or two exceptions, were convalescent. The nurse who came with me from Cape Town returned to that place, while I was to go up to Salisbury with the next convoy of wagons. These would start as soon as Colonel Beal[xx] could send up sufficient food from Beira.

Provisions were very scarce in Salisbury. The coming rainy season would stop transport; it was already difficult owing to the scarcity of oxen from the ravages made by rinderpest. It was absolutely necessary to provision Salisbury for the coming wet season.[xxi]

A few nights later Elsa describes how a leopard, she calls it a tiger, entered Mr Snodgrass’ stable and clawed a horse, the dogs barking probably drove it away. She says leopards were not often seen, but the howl of hyenas at night was a familiar sound.

Travelling by ox-wagon to Salisbury

Colonel Beal and Mr Taberer arranged for a wagon with a sail (tent) for Elsa's journey to Salisbury and she was to be accompanied by a nurse [Miss Cramer] returning to Salisbury. They expected to be 12 - 14 days on the journey and kind friends lent them a kettle, enamelled wares and food. She remarks she cannot find the word ‘skoff’ in her Shona dictionary and says of her Shona translation book: This book formerly belonged to Mr Carrick, the mining commissioner, his body was found by the Hartley Hills patrol [Edward Carrick was killed 19 June 1896 near the Hunyani, now Manyame River with A. Turner, a storekeeper and January, a detective, they had left Hartley Hills fort the day before for Salisbury. [See the article Old Fort Hartley and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills goldfield under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

We added a lantern, tin wash bowl and candles to our equipment. These with waterproof sheets, blankets and my large kaross were considered equal to any travelling emergency.

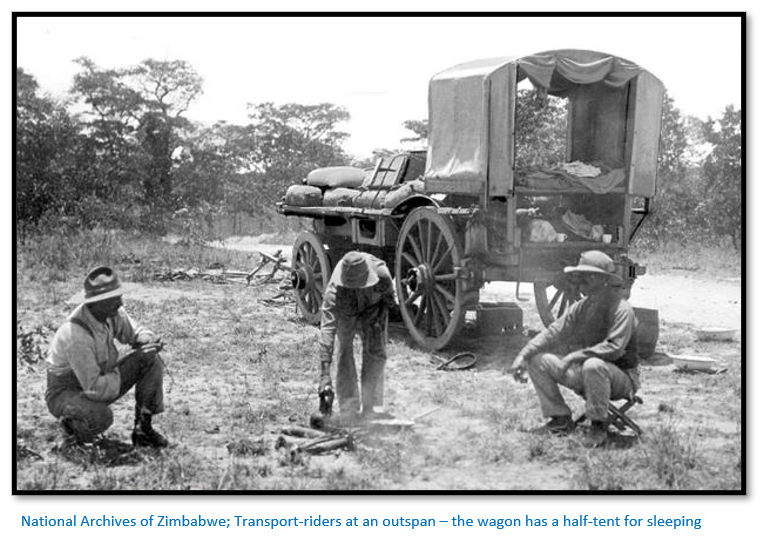

We started just before sunset, climbing into our waggon by a ladder which our transport conductor had provided at the last moment. Alas! it was necessary for our wagon was loaded so near the top that we could not sit upright. This was remedied next day by the removal of bags of rice. The convoy consisted of six wagons loaded with food supplies for Salisbury; eighty-four mules to draw them; twenty Egyptian donkeys belonging to Mr Cecil Rhodes; eighteen Shangaan natives, our transport rider and a Mr Matthews who was returning to Salisbury after accompanying his wife and child as far as Beira…besides this, we were attended by a military escort of about six or seven men of the West Riding regiment.[xxii]

We crossed the Odzi river by moonlight. Our wagon was in front. It was delightful to watch the long procession climb down the steep spruit and across the drift, each wagon with its fourteen mules. The transport rider had reined up his horse on the riverbank and shouted his directions to each driver…we outspanned at 10pm at Six Mile water. Our boys were very smart. They had fires lighted as if by magic. We hunted out our skoff box and were soon enjoying a comfortable meal.

Our conductor was the kindest man possible and as we women were only two, we got many little attentions and comforts, that of course, could not have been extended to a larger number of travellers. One we much appreciated was early coffee bought by our boy from the general mess. This prevented our having to get up at the early hour we usually trekked.

The first nights outspan was a great novelty to me. A sort of laager was formed of wagons; the mules were tied along the disselboom, to which was fastened a long portable manger for the mealies. This they got for supper as soon as we outspanned and again before our early start…The donkeys were safely tied up inside the laager, fires burning brightly, and natives round them cooking for us and boiling quantities of rice and oofu[xxiii] for their own supper.

After the early morning trek which started about 2am, the wagons would outspan about 9am for breakfast. After a wash in the nearest stream…breakfast was waiting for us. The cook Alley was good and quick. It was my plan to write notes til lunchtime, while Miss Cramer slept in the wagon. The boys and men selected any available spot of shade and slumbered also, with the exception of those appointed to watch the mules and the pickets on guard to prevent surprise from the enemy. After lunch I also got a little sleep for our nights were of necessity short. After tea on this second day, we packed carefully and travelled eight miles, not making any stop till suppertime at 9 or 10pm.

The Devil’s Pass

The third day after we left Umtali we started at dawn. I dressed after early coffee and walked the whole of the way to the remarkable pile of granite koppies called ‘Sugar Loaf,’ Orawatha is the native name for it. [the 1:50,000 map has ‘Nyahari’ in Shona ‘upside down pot’] Like some vast monument it stands in the lonely veldt. Block after block of granite rest one upon the other, bright patches of colour catch the eye from the orange and vermilion-tinted lichen growing up on the grey rocks. Halfway up the slopes the mountain is clothed with young Magoussy[xxiv] [Musasa] trees. The spring leaves are a brilliant pink, red and orange. They change later into a vivid green.

The Zeederberg coach timetable has the first stop after Odzi drift as ‘Orawatti’ before ‘Mount Yonga’ [should be Mount Zonga] in the article Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

As we left the ‘Sugar Loaf’ the scenery grew increasingly beautiful. The sunset that night was one of unwanted magnificence. That is saying much in that land of brilliant sky-effects. The moon rose as we entered the Devil’s Pass. The kraal and caves of the late powerful Chief Makoni were a few miles away to the right at the head of it. Here our natives and the Shangaans showed much alarm. They hurried up the donkeys and kept close to the wagons. Makoni had been for years a terror to the tribes who were friendly to the whites. The Shangaans had ask permission to accompany our convoy for protection from Makoni’s indunas.

It needed little imagination to see hostile natives in every burnt bush and weird, blackened tree stump. The wagon drivers even seemed to have caught the spirit of unrest and agitation, they lashed up the mules in places where the rocks and caves are abutted on the road. However, we reached Fort Watt[xxv] at the head of the pass in safety. Captain Watts of the West Riding who had been in charge here for some time was away at Lesapi [now Rusape] the Pass is wild, rugged and beautiful. The moonlight gave it a solemn grandeur, the impression of which will, I believe, be a memory forever. Our boys were too terrified to get wood or water willingly, but the threat of sjambok from the transport rider worked wonders. We encamped here for the night and the guards surrounded us for it was a dangerous place.

About 6am I woke and saw the mules grazing quietly round on the veldt. No signs were apparent of preparation for a start. I dressed quickly for I wished to know the reason of our change of programme. Soon after the conductor came saying I could sketch here for a fortnight. One of the wagons had broken down, the wheel being smashed. This was at Mount Zonga. We inspected the lopsided wagon…the boys had been sent to Lesapi [Rusape] for a new wheel.[xxvi]

Mount Zonga is almost like fairyland, beautifully wooded kopjes rose around. Later we found our way through a most lovely gully, walking on a dry riverbed. The banks sloped somewhat steeply and were covered with varieties of ferns, including maidenhair, palms, iris lilies, tall reeds and grasses, wild lobelia, geranium and trees with a white flower like a gardenia, having a delicious perfume, grew luxuriantly. Near the ground - all over the veldt - was growing the large, rose pink African Lily. [Flame lily - Gloriosa superba] We counted sixteen buds and flowers branching off from one stem. A few of these flowers would be costly in London and large cities. Here flowers flourish in lavish profusion, where no eye sees them…

The Sunday at Mount Zonga proved to be a day of delay and disaster. One of the Cape boys cut his leg deeply on the rusty iron step of the wagon. We took him to the river, washed it well and dressed it with boracic lint. Soon after our start the new wheel caught fire as we rushed with unaccustomed velocity down a spruit. It was too small, and another had to be procured and fixed. This was obtained, I fancy, from an out-spanned and deserted wagon on the veldt. The oxen which had brought it thus far lay rotting on the surrounding veldt - victims of rinderpest. This had become quite a familiar sight upon the road.

Next it was discovered that some of the donkeys had strayed. This necessitated a wait while they were hunted up. The Manica Trading Company’s (MTC) wagons now joined us for mutual protection and that they might share the privilege of our military escort. After sunset we all made a final start and formed a long procession consisting of eleven wagons and one hundred and forty-four mules.

Fort Haynes

Owing to the many interruptions to our day’s march we had to outspan at a very dangerous spot near old Fort Haynes. A night watch was set. Next morning early, we passed the enclosure where Captain Haynes and others of the troops are buried. It is shaded by a tree and has a large wooden cross at the head of the graves. Captain Haynes was shot in the first engagement with Makoni, under Colonel Alderson. We were not able to visit the graves as our outspan was too far away; but we could see them quite plainly from the road. [See the article Fort Haynes and the fight at Chief Chingaira Makoni’s kraal under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

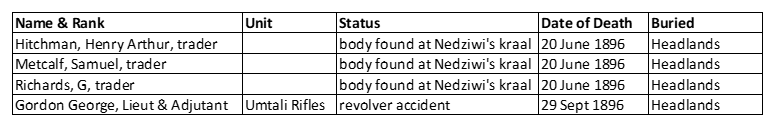

Truly this way to Salisbury has become a ‘Via Dolorosa’[xxvii] so many sad spots with graves of murdered men and those who have fallen in warfare with the natives as well as looted stores and homesteads are passed on the way to Salisbury.

Rusape

At Lesapi [Rusape] we got news of a fight at Mashimgombi’s kraal, where several men were reported killed and wounded but we got no particulars as to names. [See the article Chief Chinengundu Mashayamombe’s stronghold, Fort Martin and Cemetery under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

We crossed the Lesapi river over a wide natural granite bridge. Here the water flows for a long distance underground…next day we met a large convoy of waggons from Salisbury. There was a number of people and several ladies who were leaving before the coming rains.

The Orton’s lucky escape

With these travellers were Mr and Mrs Orton of Ballyhooley. They were amongst first sufferers in the Mashona rising and had the most marvellous escape from the natives. They were living at Ballyhooley, about 18 miles from Salisbury. No rumours had reached them, and they were quite unsuspicious of danger. At the time they were attacked they were several miles from home and off the Umtali road. Without a moment's warning the place seemed to be alive with about three hundred savage-looking natives, well-armed and evidently meaning mischief. They rushed towards them yelling and gesticulating, making assegai feints at stabbing as they ran. They had but one available horse. Mr Orton placed his wife upon it saying: “ride to Salisbury for your life.” She rode through the spot which looked least dangerous, while he and the two men who had been with them dropped into the long grass, hiding as best they might.[xxviii]

Mrs Orton arrived at the laager in Salisbury which had just been formed. She was exhausted and distressed having suffered much from exposure to the cold of the night, almost breathless with terror and apprehensive over husband's fate. Mr Orton, to the surprise of all arrived later. He had crawled under cover of the grass and reeds to the river; he crept stealthily into the stream, keeping his head only above water, hidden in the tall rushes, till night. In the darkness, with the utmost caution, he made his way to Salisbury.[xxix]

Makalakas kopjes

Some thrilling tales were told us as we chatted round our fire and dispensed tea to our visitors before the respective convoys started in diverse directions. We made a long evening trek and reached Makalakas kopjes where we had to outspan the wagons - only six now, for the MTC wagons had gone on - were pulled up into a laager, the mules and donkeys inside. It was well known that thousands of Mashonas were hidden in the kopjes round about. Mr Mathers and the conductor supped at our fire that night for company. A suppressed feeling of excitement and expectation reigned. We resolved not to give play to our imagination. Every precaution against surprise from the enemy was taken. Nothing more could be done to ensure our safety. One thing the transport rider had promised to do. He would shoot us both if we were surrounded by natives and all hope of escape was over.

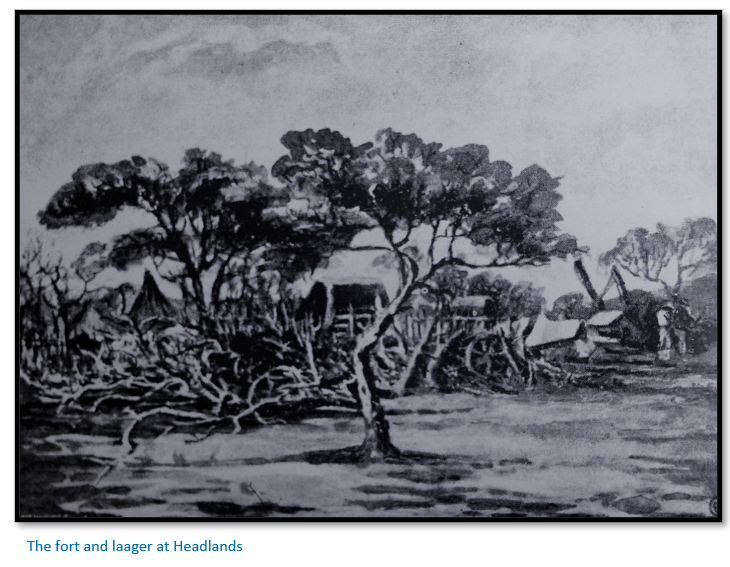

Headlands

Days passed in our slow progress. Tuesday brought us to Headlands. Lieutenant Lyle of the Umtali volunteers was in charge of the fort established there. A laager surrounded it. While I sketched under the mimosa trees, beneath which the tents were pitched, Lyle gave me an account of the escape he with his wife and family had made from the Mashonas. He had been settled only a short time in the country, in a district not far from Headlands. A messenger was sent to them to come into laager in Salisbury as the Mashonas were rising.

They made preparations to start at once with the wagon and some of their provisions. Before they were ready an army of natives, fully armed, attacked them, firing from the neighbouring kopje. They forsook the wagon, which the native stopped to loot and fled from them in a mule cart, leaving everything that they had prepared for their journey.

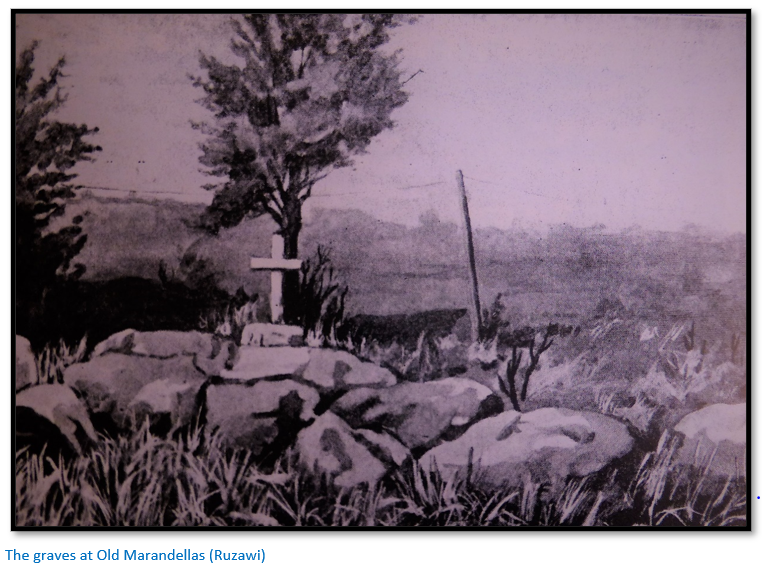

We went later to visit the graves of three young men who were murdered by Mashonas in June. They lie in a neat stone enclosure:

We met a very large convoy of wagons from Salisbury. They were drawn by ox teams. This was now quite a rare sight for oxen had become very scarce, rinderpest had made such fearful havoc amongst them. The long, picturesque procession passed us on the hill. Tented wagons with eighteen or twenty bullocks drawing each and led by a voorlooper - men on horseback, women and children under the tents or walking up the hill. There was much greeting of friends, shouting of men, barking of dogs and cracking of whips, as we met, passed and parted, each train wending its way to the silence and solitude of the African veldt.

We reached the vastness and desolation of the great Black Vlei. It was very dark. The sun had long set. The moon had not yet risen…we passed a somewhat sleepless night and I for one was glad to hear ‘Runari’[xxx] our servant, knock on a wagon and say in his sweet treble voice: “Picannin Missis café.”

Macheke

Wednesday morning, we spent an hour or two at a place called Machekes…there is a beautiful river there and as we strayed away from the encampment, we picked bunches of the beautiful African primrose…We breakfasted and trekked on to Botha’s kopjes for midday rest.

Elsa then has a long passage describing how she and Miss Cramer went for a bathe in a nearby river. They noticed a bush fire in the distance but paid no attention. Soon flames were raging around them and jumped the river on a natural bridge of stones and grass and was soon burning fiercely on the other bank. The only way the nurses could stay away from the scorching heat and overpowering smoke was to stay in the water. At last, the fire moved on and burnt itself out at the road.

Marandellas

The next halting place of interest was [Old] Marandellas where in the neighbouring districts there had been much fighting and trouble with the natives. [The original coaching inn and site of Old Marandellas is now the site of Ruzawi school. The small administrative centre moved 6 kms north in 1898 when the railway line was constructed] A few miles before we reached it, we left our wagon, to walk in the cool of the evening. Ours happened to be the last in the train. We slipped out without getting the driver to stop, so he did not know we were on the road. The transport rider also was in front, riding in advance to Marandellas. Our wagon with the rest, started off with a great pace and to our consternation, turned the curve of the road and was out of sight and alas! out of hearing also soon after.

The day faded, night rapidly descended. It grew dark and we were alone…Then we ran till we were breathless, but to no purpose… Rushing wildly on like hunted deer, we turned a corner, saw a glimmering light, and heard a faint murmur of voices. Our wagons were halting on the road. We soon gained them and found a company of officers and mounted men holding parley with our conductor. They had ridden out from Marandellas and bought us very sad news.

There had been a fight at Gatzi’s kraal. Major Evans had been shot through the heart and it was instantaneous…he had been married only a few days when ordered out on active service. Lieutenants Morris and Leigh-Lye were both wounded in the leg at Manyerbeera’s kraal. In the case of the former the femoral artery was severed, and death occurred from exhaustion following up on loss of blood.

Details of both these men and other casualties are included in the article Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga 1896-7 graves at Old Marandellas (Ruzawi Cemetery) under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

End of the Journey

Early next day we left Marandellas and as we neared Salisbury, in passing some dangerous kopjes, shots rang out. We had to lie down in our wagon for safety. Some of us thought hunters might be shooting game, but in Salisbury it was reported that the natives had fired on our convoy, as well as upon a gentleman who had ridden out from the town.[xxxi] Our last outspan was about eight miles from the end of our journey. There we expected to stay till evening. The wagon in which Major Watts had sent dynamite to Gatzi’s kraal came along as we finished breakfast. We climbed to the top and proceeded on the way, in the company of loaded guns and other weapons of warfare. Thus, we made our entry into Salisbury some hours before the rest of the convoy.

References

E. Goodwin Green. Raiders and Rebels in South Africa. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1976

The ’96 Rebellions: The BSA Company Reports on the Native Disturbances in Rhodesia, 1896-97. Books of Rhodesia, Bulawayo 1975

Notes

[i] W.D. Gale wrote One Man’s Vision; the story of Rhodesia, The Rhodesian Press: The History of the Rhodesian Printing and Publishing Company Ltd, Zambesi Sunrise: How Civilization came to Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

[ii] Raiders and Rebels, P3

[iii] Ibid, P13

[iv] Ibid, P17

[v] Ibid, 24

[vi] Wikipedia; Braamfontein explosion

[vii] Raiders and Rebels, P40

[viii] Ibid, P45

[ix] Ibid, P57

[x] Ibid, P65

[xi] stream beds

[xii] Raiders and Rebels, P68

[xiii] Ibid, P72

[xiv] “Old Umtali” Mission is located at the second site of Umtali (now Mutare) the first being at Fort Hill at Penhalonga, founded in 1891. The town and all its inhabitants were relocated approximately 10 miles southeast in 1896 to a location more convenient for the railroad line then being built from Beira. This was less expensive than bringing the line through the Nyamashiri mountain range (Christmas Pass).

[xv] Raiders and Rebels, P83

[xvi] The donkeys Powder and Pills were given by Sydney Fort to the first nurses at Fort Hill, Miss Lucy Sleeman and Miss Rose Blennerhassett.

[xvii] Henry Melville Taberer (7 October 1870 – 5 June 1932) was Chief Native Commissioner in Mashonaland in 1895.

[xviii] Raiders and Rebels, P92

[xix] Elsa was not to know the Native Commissioner Hulley had ridden to Chief Mutasa’s kraal at Bingaguru alone and persuaded the Chief not to follow Chief Makoni’s example…thus there was no uprising in Manicaland.

[xx] Lt-Col. Robert Beal was in command of the relief column that went from Salisbury to Bulawayo at the outbreak of the Matabele Uprising

[xxi] Ibid, P105

[xxii] Ibid, P112

[xxiii] Mealie meal porridge or sadza

[xxiv] The Zimbabwe Tree Society website says this is probably an anglicised variant of the Kalanga “muguzhe”

[xxv] Elsa calls it Fort Wood

[xxvi] Raiders and Rebels, P121

[xxvii] Wikipedia: Latin for "Sorrowful Way", often translated "Way of Suffering"; is a processional route in the Old City of Jerusalem, believed to be the path that Jesus walked on the way to his crucifixion.

[xxviii] The ’96 Rebellions reports Arthur Smith and August Thomas Tucker the barman at Ballyhooley both killed between 18 – 20 June 1896 near Ballyhooley

[xxix] Raiders and Rebels, P126

[xxx] In Shona meaning ‘telegraph wire’

[xxxi] probably in the vicinity of the rocks on the eastern edge of Msasa industrial Estate at the old Rhodia fertiliser plant]

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: