Sharing and family unity

By Lamech Mhondoro

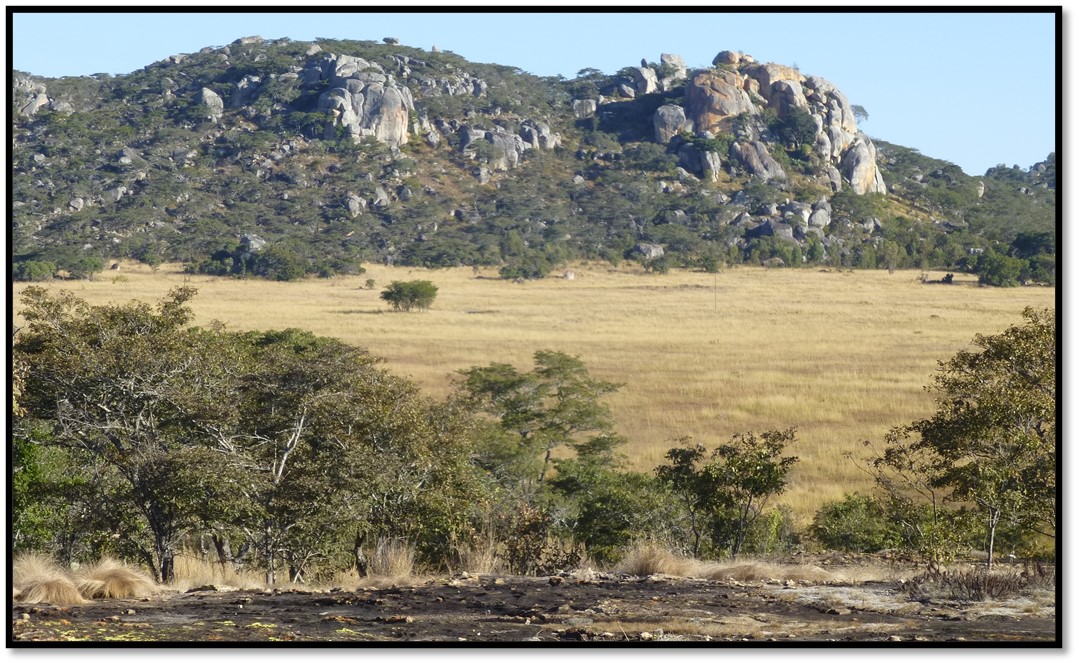

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

In Shona society there are few individuals who can go their own way because hardly any person is free from the control of and dependence on relatives.

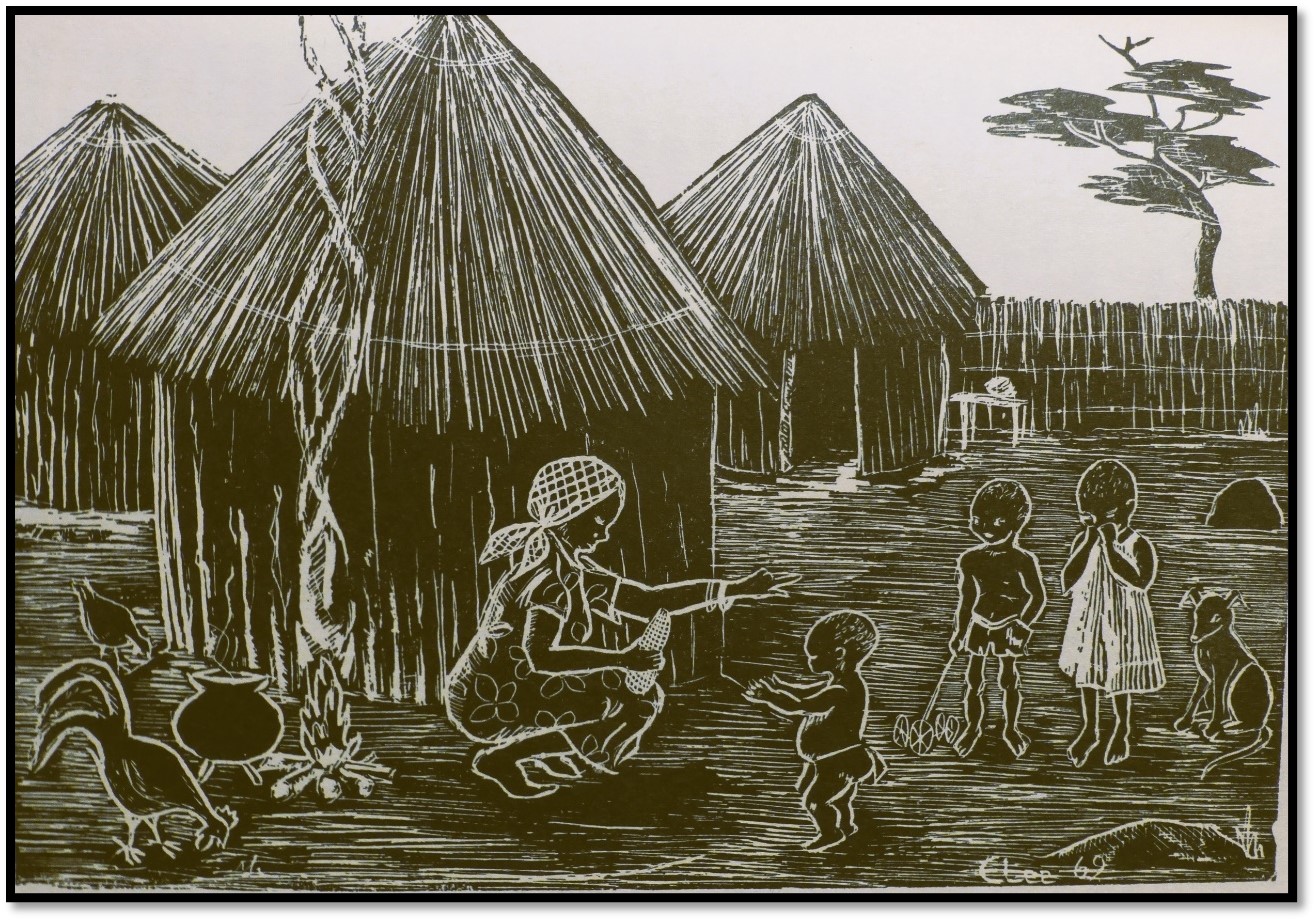

From a very early age a Shona child is taught to share all that he has with his brother, sister or cousin. A mother may give a boiled Mealie-cob, a piece of boiled pumpkin or some other food to her young son and tell him to give half of it to his brother. If the child refuses, the mother punishes him. She does the same thing several times until the youngster learns to share. This habit may become so strong that he finds it difficult to eat anything without giving half of it to a relative. When he gets something to eat, he looks for his brother or sister or he eats half and leaves the other half for them.

From the age of four, Shona children are given their food in groups, usually with their cousins. As they grow up they continue eating in groups according to age. They share the same plate, all eating with their hands. Each person is careful that he does not take more than his fair share.

When a man is married and has a family, he still keeps this spirit of sharing. When his wife brews beer, the first people to be called are the closest relatives. The eldest amongst these, (usually the eldest brother) is given charge of the beer. He is responsible for giving it to the other guests. He also makes sure that a few pots of beer are left over for the family to enjoy when all the guests are gone.

During the ploughing season, all members of a Shona family make sure that the field of each member is ploughed. If one has no oxen or plough, the others supply him with what he lacks. If that fails, then they choose a particular day when they all go to his field with their oxen and ploughs to do the ploughing. If a family member is away working in town, one of his brothers is given charge of this man's family. The brother sees to it that the ploughing is done properly. He has almost the same power over his brother’s family as his brother has.

In most Shona families a girl is under the control of her aunt and uncle. They are more responsible for her behaviour than are her own parents. It is the duty of these two, specially the aunt to make sure that the girl grows up to be a good wife. When she does anything wrong or disgraceful, her father does not take action against her. He reports the matter to the aunt and uncle, and they usually scold her and advise her.

When a girl finds a boyfriend, she introduces him to her aunt who will decide if the boy is a worthy gentleman. Although it seldom happens, the aunt can stop her niece’s love with any boy if she is convinced that he will not make a good husband.

At the time of marriage, the uncles on both sides agreed on the details of the marriage, including roora. At the wedding reception is their responsibility to make sure all the guests are well fed.

A Shona man’s sense of duty towards his brother family is so strongly stressed that, when the brother dies, he customarily honours his obligation to take over the wife and children. However, this has met with opposition from the churches as it often results in polygamy.

Another important feature of family unity is a son’s duty towards his parents. According to Shona thinking anyone who abandons his parents is not fit to live. In foreign societies a son can send his parents to a home for the aged, but in Shona society one of the sons, usually the last-born is given the responsibility of looking after his aged parents. This does not mean that the other sons do not help him. On the contrary, they do all they can to help their youngest brother look after the parents. For a Shona man to send his parents to a retirement home would be to bring shame on the whole family.

There is such a strong connexion between the members of a Shona family that each person is very proud to be called by the family name instead of his own first name. A true Shona will not hold a beer party, conduct a marriage or do anything special without the knowledge of his relatives. Furthermore, he will not permit his brother's family or his parents to starve while he lives.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974