The Old and the New

By Alois Maveneka

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

Since the coming of the white men into this country, the indigenous people have undergone rapid change. That change has been greatest where contact with the white man was most extensive, as in towns. It has been slowest where contact was limited, as in the Sabi [Save] and Zambezi river valleys.

Change is essentially a continuous motion from one state of being to another. We know that the people of this country had a different way of life before 1890. Today, 80 years later we find some who have become so westernised that it could be said that only skin colour differentiates them from Europeans. On the other hand, there are others who still live basically the life that was led by everyone before 1890. But the majority of the people, both in the towns and in the country, are at various stages of changing to the modern way of life.

It is useful to compare the African who is high on the ladder of change with the one who is still leading a traditional way of life so that we may see clearly what kinds of changes are occurring.

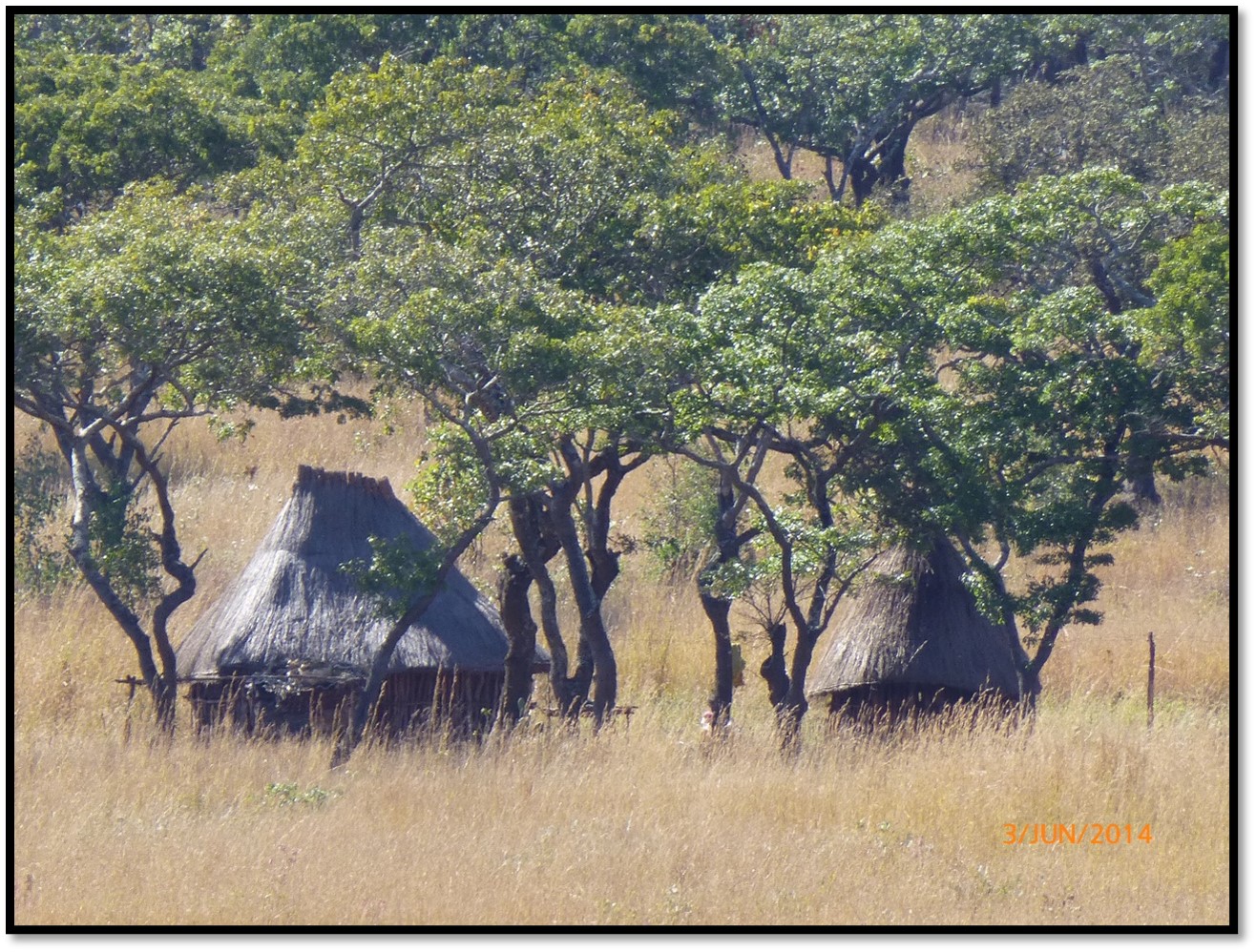

In the traditional kraal each family lived in huts. Wooden poles of about the same length and thickness were stuck into the ground close together, leaving a small opening for the doorway. This structure was plastered with mud. The roof was made of thatch. In most cases, the huts were round and small, but the problem of space shortage was solved by having many such huts: one for the kitchen, others for granaries and another for general storage purposes. There were also a number of sleeping huts, one for the parents and others for the boys and girls of the family.

In the hut used as a kitchen there was a fireplace in the middle of the floor with three stones on which to rest the earthenware cooking pots. Around this fireplace the family sat in the evening for warmth while the mother was cooking. Along the wall of the hut was an earthen bench on which pots were neatly arranged one on top of another, beginning with the biggest ones at the bottom and ending with the smallest ones at the top. Also on this platform wooden plates and various utensils were kept. Cooking sticks and ladles were usually suspended between two forked sticks fastened to the wall. Another bench, usually lower and narrower than the one just mentioned, started at the entrance and continued around the wall. This was where the men sat when having meals or just resting. At the junction of the wall and roof, hoes and axes were stuck into the thatched grass by their handles. To keep the floor smart, the mother smeared it regularly with cow dung which left it with a greenish colour.

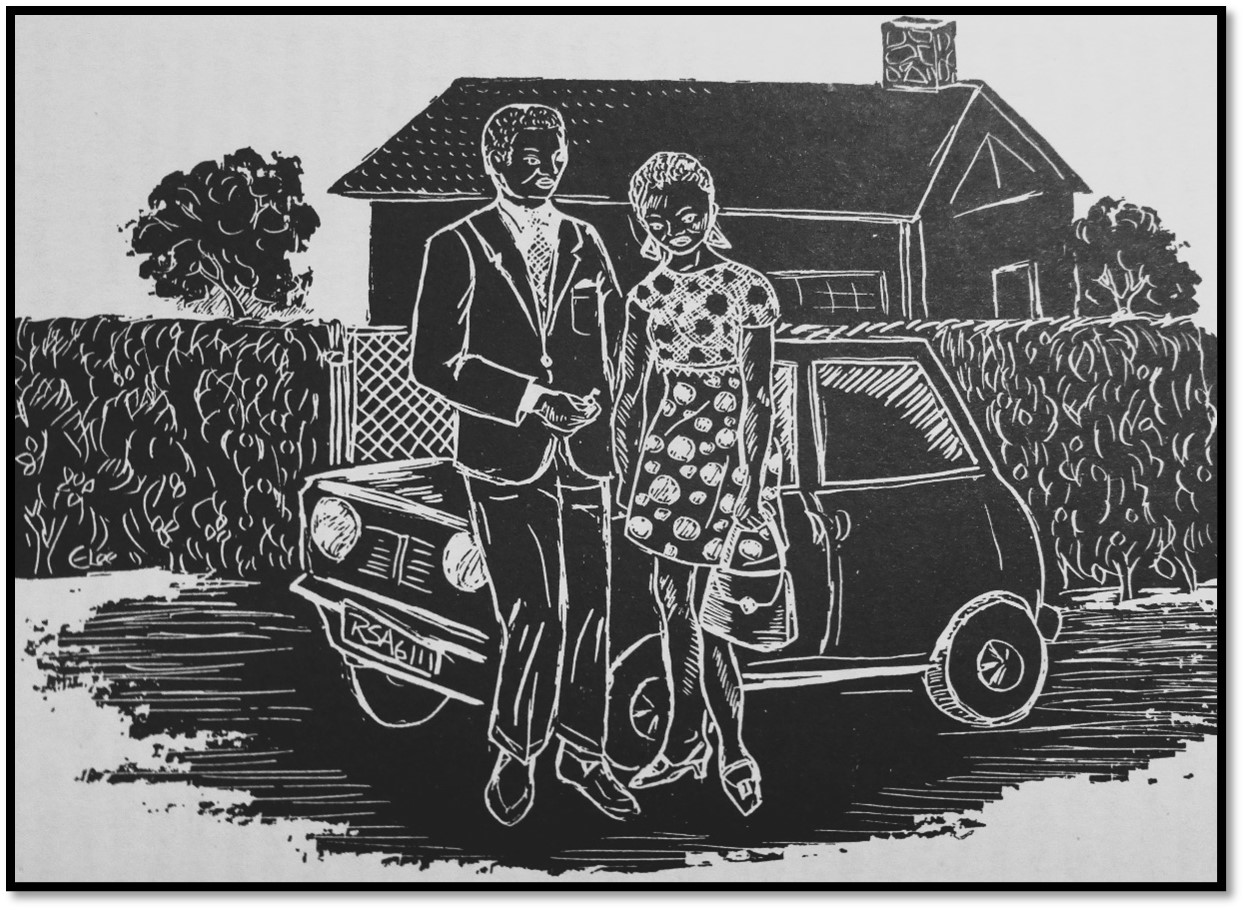

Today we find many fathers who have taken their families to live in a house in a township or location. This father may own or rent a modern house with several rooms The house may be equipped with modern furniture, cheap or expensive according to the father’s means.

The wife of such a man has in her kitchen a stove which uses either electricity, coal or wood. Her utensils are made of metal and china. She keeps her cups and plates in the cupboard while she stores food in the pantry. With a water tap right in the house, she has a great advantage over her counterpart in the hut who has to go a long way to fetch a pot of water. The parents of such a family, if not the children, also have beds to sleep in. They use pillows, cotton sheets and woollen blankets. To wash themselves they have only to go into the next room, whereas the people of the old way of life had to go a long way to the river. Without soap and cosmetics is difficult for our forefathers to compare in smartness to those who use these chemicals and oils. Instead of sitting on an earthen bench in the kitchen and taking meals with a simple floor for a table, this family has a dining room in which to eat comfortably on a table. They may have a sitting room in which to relax listening to the radiogram or perhaps watching television.

Although I have talked of huts as things of the past, we all know that in the kraal today, they still exist. At the same time there are others who are putting up modern houses for themselves in these same kraals side by side, with the traditional huts.

Long ago clothing consisted of two animal skins, one in front and one behind. The skins worn by men were usually smaller than those worn by women. Nothing covered the trunks of those men while the women wore another piece of skin tied over the shoulders to cover their breasts. Their skins were rubbed with sand to clean them an, these d softened with fat such as the cream from milk. Small children used to run around naked except for a cord, made from the bark of certain trees, which was tied around their waists.

Today the modern family goes about in western dress, which has numerous advantages over traditional skin clothing. It can be washed, it can be made to fit weather conditions and is capable of having many designs, which makes those who put it on look smarter. No one today admires people who wear animal skins. Instead, they are regarded as poor, backward and unfortunate beings.

Traditionally, cattle with the main position of almost every family marking its social standing in the community. They were looked after in common and the pastures were common property. In the morning all the livestock would be brought together and entrusted to the members of one family to look after the animals for two or three days. Families took turns herding the cattle. Boys and young men usually did this job. For the boys this period of herding was the roughest time in their lives. They would leave for the pastures early in the morning, having eaten a breakfast specially prepared for them. Unless they carried food along, they spent the whole day without eating anything except wild fruit. In the pastures with bodies clothed only in skins these herd boys were subjected to the summer’s heat, the winter’s cold and the seasonal rains. This life was hardest in the rain because the animals move rapidly around putting their backs to the wind and the rain which makes it difficult to control them. If they wandered into someone's field and ate the crop, the young herd boys would be sure to get a good beating from their parents and might even spend the night looking for the stray cattle.

Perhaps there has been no great change in the manner of pasturing, but today we appreciate the fact that herdsmen are better protected from the weather. Their feet need no longer be filled with thorns because shoes can be used for protection and raincoats can be worn for greater comfort on rainy days. The difficulty of herding is also greatly minimised for farmers who keep their animals behind fences.

The life of herding was also one of fighting. The older boys enjoyed strengthening the younger ones into men by making them fight each other. This could be tough for the weaker boys because, if they refused to fight or surrendered too easily, they would be beaten up by the onlookers. And, of course, anyone who reported these cruelties to their parents would be taught a good lesson the next time he came herding. This rough herding life was supposed to be kept secret among the boys. But parents were not ignorant of such things since they too had passes that way as children.

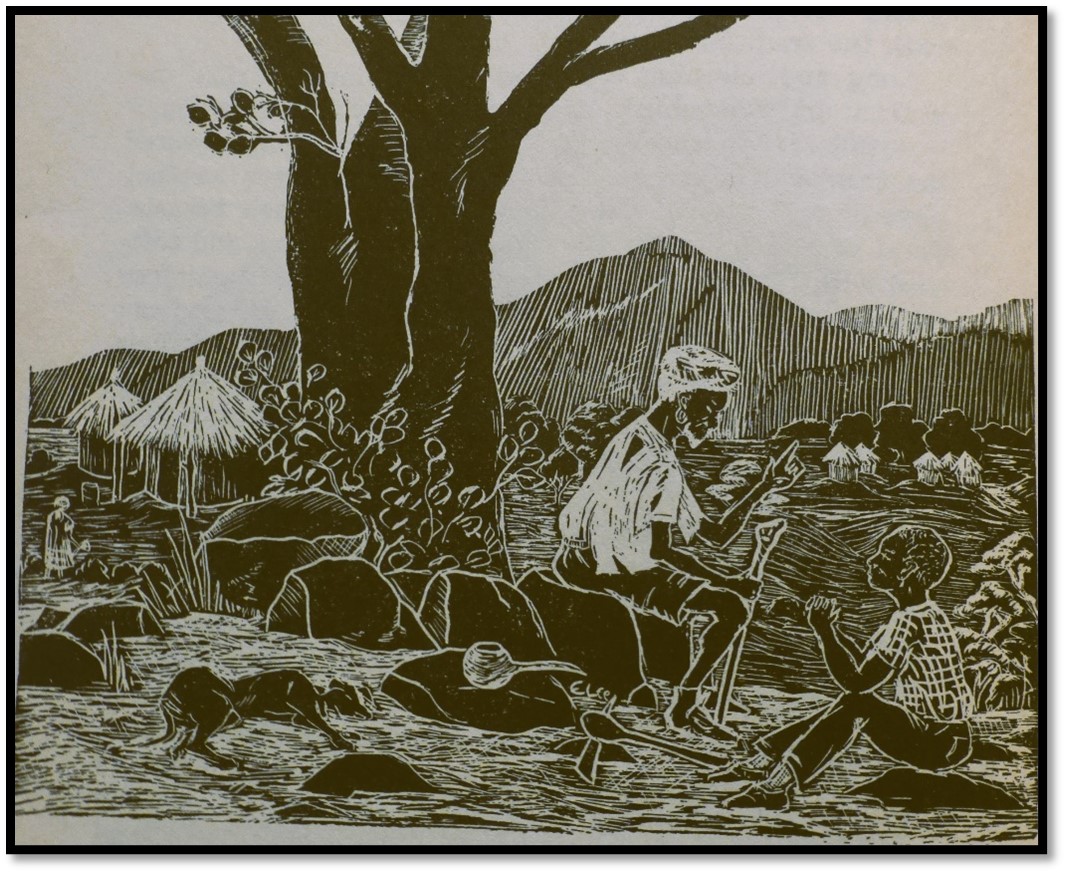

Besides herding, the youth spent their time looking for wild fruit, trapping birds and mice, and playing games. They moulded cattle from clay and made them fight. They also played hide-and-seek while bigger boys played such games as tsoro. Swimming and hunting with dogs were other recreations. Men spent their leisure time sitting at the dare. This was a place under a tree or bush, surrounded with branches for protection. There the men talked business or just chattered. Men ate their meals together. Drinking beer, drumming, singing and dancing were also recognised ways of spending the happy moments of the community.

Today boys had no time for the pasture for they must go to school. Neither can they go after wild fruit and play games because homework is waiting for them or parents need their help. Modern games fascinate boys more than the old ones and instead of making cattle from clay they make toy cars from wire. We also find the radiogram replacing the drum. Western music is what appeals to the modern youth’s ear and going to the cinema is regarded as a necessity by town dwellers. Beerhalls in the townships have taken the place of traditional beer parties with the advantage that beer is always available in the bar, whereas in the kraal there would be times when there was no beer.

Long ago, the place for girls was in the home with the mother. As small children, they helped the mother in little ways, going with her to draw water with small earthenware pots. While the mother carried a big one, the daughter would practise with the smaller one. While the mother carried a heavy bundle of firewood on her head, the little girls would also carry small bundles. Women thus developed a capacity for carrying goods on their heads while a baby was tied to the back. Thus their hands were free to carry yet other things.

For recreation, girls used to make dolls from maize cobs. Older girls play games like nhodo where pebbles are taken in and out of a small hole while another pebble is thrown up and caught before it falls to the ground.

Like their brothers, girls have also become students and their time has to be divided between school and home. They too want modern games and manufactured dolls instead of the home made ones. Older girls now spend part of their spare time making themselves appear more beautiful.

Preparing the two main meals of the day, lunch and supper, was the work of the traditional mother. The time for eating meals varied according to the season and the menu. So, for instance, lunch would tend to be early during the rainy season where people would be going out to the fields while supper would be delayed because it was eating after the day's work was finished.

Modern foods like tea, bread, butter, jam, citrus fruits, guavas and mangoes were absent from the people’s diet. As a result, breakfast for the family of old was very different from today. Children were fed on the cold food left over from the previous night or some kind of porridge prepared for them in the morning. When the crops were right, there was a greater variety of foods such as green mealies, groundnuts, monkey nuts and pumpkins, which were all cooked and watermelons and sugar cane which were eaten uncooked.

Traditional subsistence farming made people totally dependent on the land and the weather. Today the man who has entered the money economy is able to vary his diet throughout the year without waiting for the rainy season to provide fresh food.

The modern mother in town does not spend long hours in the fields because in town there are none. Her husband is employed so she does not have to depend on farming for the family’s livelihood. It is usual that she keeps a small garden for fresh vegetables and flowers. She does not have to spend half the afternoon looking for firewood in the forest for she can buy it right at her door from vendors. Instead of spending her free time sitting around a beer pot with neighbours, she may spend it repairing the family’s clothes or crocheting.

Another point to examine is the extent to which the relationships between people has changed. The traditional home of the Shona was the musha, what is called kraal in English. It is made up of a number of families, usually related to each other and grouped together under a headman. In these small communities mutual help was characteristic. Under the chairmanship of the headman, the fathers of families in the kraal met to discuss matters of common interest and to settle small disputes. Larger issues, such as murder, were referred to the chief who was the supreme ruler of a larger area made up of many kraals. All that people had to know in order to live was in the hands of the wise chiefs and elders of the community; their authority was accepted. Wisdom was associated with age, while ignorance went with youth. The laws fitted both the time and the circumstances of the people, but at present, youth coming out of schools find the old ways outdated.

It is natural for chiefs to think in terms of their respective districts, but the younger generation discuss international affairs. Formerly all the chief’s subjects lived in his district but today people are leaving their districts to seek fortune in towns, mines and large agricultural enterprises like the Lowveld project. Some of these people have no intention of returning to the district again except to visit relatives. Others are settling in neighbouring countries.

Marriage, which frequently took place between people from the same kraal or neighbouring kraals, now commonly occurs between people from different corners of the country. It is now easy for a lad from Hwange to marry a girl from Masvingo or a girl from Bulawayo to marry a man from Malawi who was working in Zimbabwe. This modern state of affairs makes it difficult for chiefs and headmen to exercise such power as they formerly had.

Members of the same family may be scattered in different places. The father might be working in town while the mother is at the kraal with the young children; the older children are away at boarding schools. This hampers parental control over the children. When the children come home, it is difficult for parents to do much because their children ‘belong to the new world.’ The children argue that they come from school, where they learn much that the parents do not know and therefore they consider their parents old fashioned.

Modern means of transportation like bicycles, buses, cars, trains, etc, make travel faster and easier, but they also contribute to the confusion.

In the kraal, mutual help was the rule. By brewing beer and inviting others, a family received help in preparing the ground for seeds, weeding and harvesting. Also work such as threshing maize thatching huts and gathering firewood could be done together. Anyone who did not go to such beer parties would have no one coming to his aid when he needed help. Even if he did not drink, he had to go and help. Now, however, in the townships the law forbids brewing beer and when anything needs to be done, an expert is called.

Crimes were fewer in traditional society because misbehaviour, besides being severely punished, strained the whole family in a way it does not today. People would not talk of how badly some man or woman acted, but of how badly the man from Mr Gudo’s family acted. Therefore, one had to be aware not only of his name, but also that of his family. Also, if a person stole, he stole from a relative, because almost everyone in the kraal was a relative and the ancestors would punish one who stole from relatives. And even more tangible deterrent was the shame of using a stolen hoe when its owner was just in the next field.

In the townships neighbours are often strangers from different parts of the country; a man does not mind if he acts badly. If he steals from someone in town, he will not disgrace his name for no relative will be likely to know of the deed. The spirits will not punish him because his victim is a stranger, and he reasons that his wage is unjustly low, so what else can he do if he wants to live.

Superstition, as history testifies, is a characteristic common to all people at some stage of development. Among our forefathers, it was widespread. Suffering, such as sickness and death was regarded as sent to man by evil spirits, or as punishment for wrong-doing sent by the ancestors.

Witchcraft could also be the cause of such maladies. Droughts, too, were supposed to be caused by spiritual powers. Although it was held that there is Mwari, the one God, he was remote and not concerned with the activities of men. Lower spirit, especially those of deceased ancestors, played a greater part in bringing blessings and curses to men.

For those who have left the old ways of thought, much of the superstition is gone. They now believe that they are physical and natural causes which explain sickness and death and that much suffering and premature death can be averted by living under hygienic conditions and going to the hospital in the event of illness. Droughts are now understood to be the result of natural laws. Accidents and chance occurrences are now recognised as such and no appeal is made to the spiritual world for explanations.

Similarly, we find thar those who are changing to modern ways in material things are doing so in religion as well. Some people find the truths of the old religion are confused and crowded by superstitions, and they join one or another of the Christian denominations, depending on who comes to preach to them first. Here change is not yet complete because many converts do not mind being Christians as long as everything goes well. But the moment trouble arrives they turn to the traditional ways of dealing with misfortunes.

The African people in this country have an open mind towards modernisation. They see that their traditional way of life lacks much of the West enjoys, especially in the fields of science and technology. What getting in the fence? By accepting and using these benefits of Western civilization, they see that they are no way harming or destroying themselves; instead they are fortifying their race. Adjustment of the old ways to fit the present is one of the prerequisites for survival both for the individual and for the community. Aware also that the European benefits from the achievements of other civilizations, the Shona need not be ashamed of assimilating new ideas and practices; they are doing what has always been done throughout history.

It is also acknowledged that everything traditional should not be changed to make way for the modern, nor should everything modern be accepted as good or superior. It is wrong to reason that everything traditional is bad and must be rejected, that everything new is good, and should be accepted.

It is usually true that old people are more conservative than young people and that they stubbornly cling to their old ways with a strong aversion to anything new. Among the Shona there are old men and women who value the traditional life, guarding it jealously and refusing to part with it. They look upon change as evil which breaks the stamina of the people leaving them physically and spiritually weak.

The African is often asked by Europeans why he leaves his windowless hut to go after European houses; why he prefers the white man's food and dress; why he leaves his drums in favour of the radiogram. These questions are answered by history. Some people believe that because it took Europe 2000 years to develop to the present, it will necessarily take Africa as long or longer to do the same. We can disprove this theory by pointing facts. We might also point out the supposing the theory were held, then even after 2000 years, Africa would still not have caught up because in the meantime Europe would have gone ahead another 2000 years. This leads to conclusion that the difference could never be resolved. This conclusion can never be accepted by serious minds, but it is still employed when emotion has blocked men’s reason.

Rate of change vary according to the degree of contact between Africans and Europeans and depending on which aspect of life is being considered. It is also true that a person may be modern in some ways, and traditional in others. Africans in Zimbabwe have been undergoing rapid change for nearly eighty years and will continue do so at ever quickening page.

Most people are not hostile to change; they realise that their civilization lacks much of what the Western world possesses. They acknowledges this fact realising that Europeans too assimilated idea and discoveries of other civilizations such as Egypt and Mesopotamia.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974