Macheke Rock Paintings

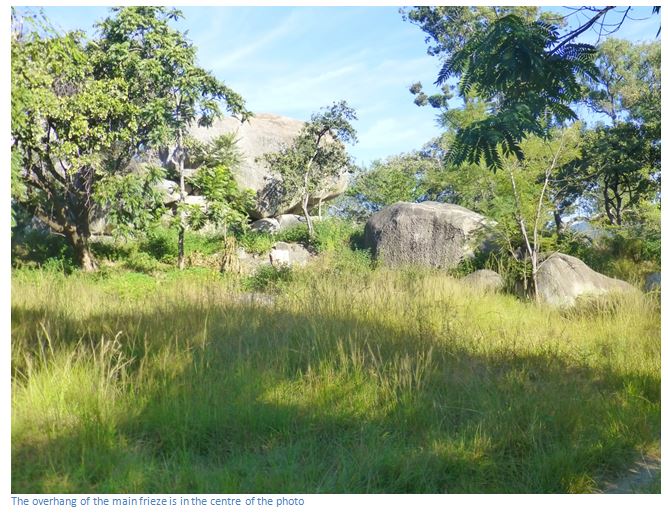

- Easily accessible just behind the Macheke Railway station.

- The main frieze in on the north side of the granite outcrop, but there is another high up on the southern side which features mainly kudu images.

From Marondera take the A3 towards Mutare. At 31.2 KM reach Macheke and turn left towards the railway station. The rock paintings are 200 metres from the A3 national Road on the north side of the large granite boulder on the left of the road and behind the railway station.

| GPS reference: 18⁰08′38.87″S 31⁰50′29.39″E |

In a 2014 newspaper article Cathy Buckle visited these rock paintings to show them to a foreign guest, but makes no mention of the paintings she saw, because she was so embarrassed as the rock art site had become a public toilet strewn with tissue paper, human faeces and garbage. She says the urge to abandon seeing the paintings was almost overwhelming and says it is hard to believe that this is happening in the same Zimbabwe that was recently awarded the 2013 “World’s most preferred cultural destination”.

I suppose with no public toilets for the numerous bus passengers and just 200 metres from the A3 national road, we should not be too surprised; but on my visit in 2016 things do seem to have improved. The local Council has put up a small sign which is labelled “Rock Paintings” and points down a path to the site.

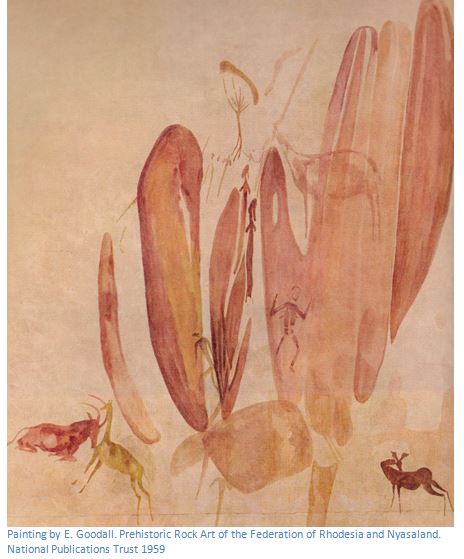

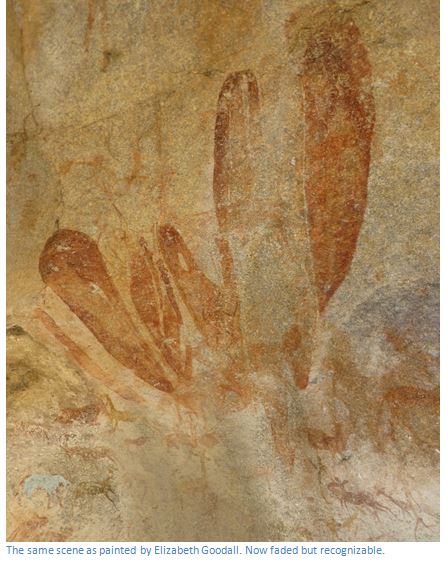

Two very widespread images occur in the rock art of this country which is seen in this otherwise unexceptional frieze. The first image is the formling, or ovoid which forms the centrepiece of Elizabeth Goodall’s painting and the photo above. They have been interpreted in the past as representations of kopjes, or mbiras and xylophones, or bee hives.

First some background. The !Kung, the living descendants of the original San hunter gatherers who painted these rock art scenes did not visit a doctor when they were sick, nor did they attend church for spiritual guidance, nor did they have a community centre to bring them all together. To the !Kung these aspects of life were not divided; the living world and the spirit world were all interconnected and came together in the healing, or trance dance which was their foremost method of healing sickness, injury and disease.

They believed that sickness and injury and distress were caused by the spirits of their dead relatives; the gauwasi, who live with the Gods in the sky and become lonely and shot “arrows of sickness” into their living relatives. There was no separation between the spiritual world of the Gods and our earth, so life became a battleground between the !Kung who want their relatives to stay with them and the gauwasi who wanted them to join them in the spiritual world.

The above formling, or ovoid represents N/um to the San painters; a substance that exists in every human in their stomach, but only becomes activated during a healing, or trance dance when several groups of these nomadic hunter gatherers would gather together. The killing of an antelope might be the trigger event as the large amounts of meat would need to be eaten quickly.

The trance dance starts slowly with dancers being predominately male and the women singing and clapping around a fire. After many hours of singing and dancing which might involve hyper-ventilation, the spiritual energy, or N/um of some of the dancers would become activated. The San describe the N/um in their stomach as becoming heated and rising up their spine. This heightened form of energy would lead to the trancers feeling that their limbs were becoming elongated and they would go into trance, a state they described as !kia. In this state they entered the spirit world and pleaded with the Gods to spare their relative from the gauwasi.

The formling, or ovoid shape was a !Kung symbol for N/um; there are estimated to number in several thousands in the Zimbabwe region and they would have been instantly understood by San hunter gatherers. Beneath the above formling appears a line of dancers too faint to photograph, but which would have reinforced the metaphor for their San audience.

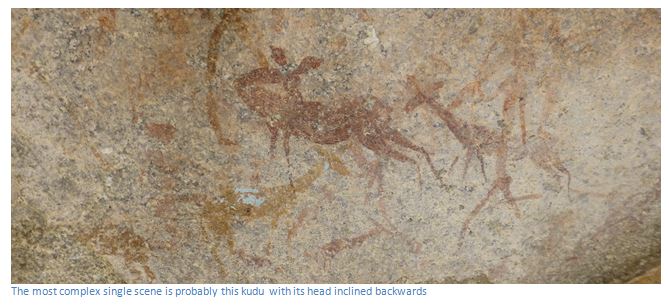

The other widespread image which predominates in this country and Limpopo province of South Africa is the kudu antelope. In South Africa, San paintings of eland dominate in the Lesotho / Drakensberg mountains and the gemsbok in the Kalahari and there is a mass of oral evidence concerning their myth and ritual taken down by early historians. Unfortunately there is none in Zimbabwe because the San hunter gatherers were already gone; but clearly the kudu in the Zimbabwe region was the centre of the same mythology and the kudu represented a potent animal and of special significance.

The only survey of numbers of animals in the Trelawney / Darwendale area revealed that 65% of the animal paintings were of kudu. In addition, research by Edward Eastwood and Cathelijne Cnoops in the Shashi confluence area of Zimbabwe / Botswana and South Africa showed that:

(1) Kudu were more frequently painted in polychrome (i.e. two or three colours) than other animals,

(2) Kudu images were more detailed with body stripes, outlining in white paint and accurate twisted horns,

(3) Kudu images are often larger than other animals,

(4) Kudu images are more frequently found in complex painted scenes than other animals.

Although an animal count was not taken at the Macheke site, it is clear that the Kudu predominates, followed by three or four images of sable.

The Macheke rock art paintings do not seem to have faded much in the intervening +/- 55 years when it was copied by Elizabeth Goodall and there appears to be no human damage to it.

Acknowledgements

Cathy Buckle. Let's work on our Cultural Treasures. Daily News. 11 June 2014

C.K. Cooke, J. Desmond Clark, E. Goodall, Edited by R. Summers. Prehistoric Rock Art of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. National Publications Trust 1959

P.S. Garlake. The Painted Caves, An introduction to the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Modus 1987

E.E. Eastwood and C. Cnoops. Capturing the Spoor; towards explaining Kudu in San rock art of the Limpopo – Shashi Confluence Area. South African Archaeological Bulletin No. 54, 1999 Page 107-119

M.R. Tucker and R.C. Baird. The Trelawney / Darwendale Rock Art Survey. Zimbabwe Prehistory. No. 19; December 1983. Pages 26-58

D.J. Lewis-Williams, and T.A. Dowson. Images of Power: understanding San rock art. Southern Book Publishers. 1999.