Home >

Mashonaland East >

Fort Harding, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm Police Camp

Fort Harding, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm Police Camp

Why Visit?:

The Goromonzi area with Chiefs Seke, Chikwakwa and Kunzwe, together with Chief Mashingombi to the south west near the Mupfure (formerly the Umfuli) River formed the heartland of the Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga. Kaguvi, the prominent spirit medium who had married a woman of Gondo’s kraal and stayed for long periods at Gondo’s kraal, just a kilometre north of Chief Chikwakwa. Kaguvi provided the moral and spiritual backbone of the resistance supported by Nehanda in the Mazowe / Amandas area.

This small area played a central role and the way the action played out in the area is typical of the Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga in Mashonaland generally.

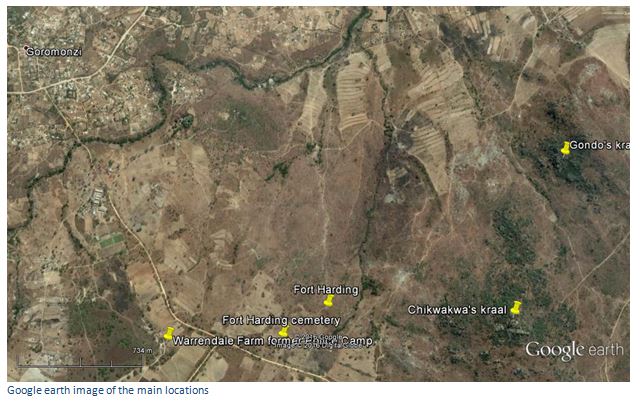

Most of the places that played a part in this small piece of nearly forgotten history can be easily viewed within a small area as seen below on the Google Earth snapshot of Fort Harding, the cemetery, Chief Chikwakwa and Headman Gondo’s kraals and Warrendale Farm Police Camp.

How to get here:

(1) For Fort Harding cemetery take the Mutare Road (A3) from Harare. Directions are from Ruwa / Chiremba Road junction: 5.2KM turn left onto the Goromonzi Road; this has good tar as far as Goromonzi. 11.4 KM pass turnoff for Mashonganyika kraal; 17.3 KM turn right onto Eton Road just after the Goromonzi Police station. 17.8 KM turn right onto a gravel road, 18.3 KM cross the drift, 18.6 KM pass tobacco barns, 19.7 KM pass turn off to the right, then immediately afterwards, turn left onto the track taking the right fork along the edge of a field. 20.2 KM park at the junction where another track joins from the gravel road. The cemeteries are in the trees to the right of the road.

(2) Fort Harding follow the same well-defined track around the end of the field bearing left of a farm house and following the track in a north east direction for 350 metres. Fort Harding is on a small knoll a few metres to the right-hand side of the track.

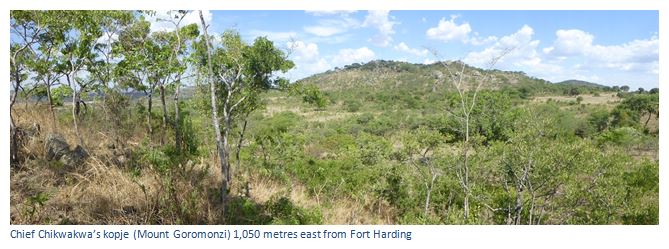

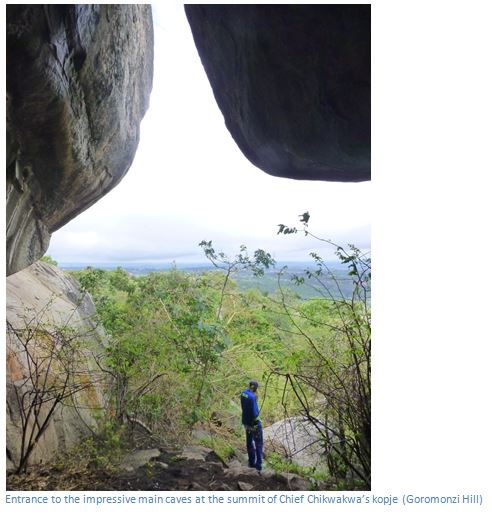

(3) Chikwakwa’s kraal is 1,050 metres east of Fort Harding. The main caves face north east and are below the summit of the kopje facing Gondo’s kraal to the north.

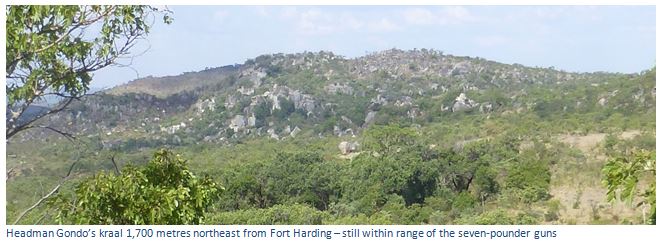

(4) Gondo’s kraal is north is 1 KM north from Chikwakwa’s kraal and 1.7 KM from Fort Harding in a north east direction.

(5) Warrendale Farm Police Camp is on the same untarred road as Fort Harding; turn right onto a track 1.63 KM from the Eton Road turnoff and then 200 metres along this track.

GPS reference for Fort Harding: 17⁰52′09.31″S 31⁰23′48.07″E

GPS reference for Fort Harding cemetery: 17⁰52′14.94″S 31⁰23′38.91″E

GPS reference for Chikwakwa’s kraal: 17⁰52′11.06″S 31⁰24′25.22″E

GPS reference for Gondo’s kraal: 17⁰51′40.26″S 31⁰24′37.82″E

GPS reference for Warrendale Police Camp: 17⁰52′15.17″S 31⁰23′15.95″E

In Mashonaland the Uprising / First Chimurenga which broke out in June some three months after the Matabele Uprising / Umvukela caught the Europeans completely by surprise. Four companies of Mounted Infantry (380 troops) who arrived in Cape Town in mid-May to help in Matabeland were diverted to Beira by sea, travelled 270 kilometres by rail to Chimoio, reaching Umtali (now Mutare) on 19th July 1896 and then travelled the remaining 260 kilometres to Salisbury (now Harare) by ox-wagon and on horseback. The strategy used by Carrington in Matabeland of building forts to hold rebel ground was not used in Mashonaland by their commander Lieut. Col. E.A.H. Alderson, who preferred rapid strikes against Mashona strongholds by strong patrols that would then withdraw. Partly because of this strategy, the Mashona Rebellion / First Chimurenga dragged on through the rainy season of 1896 and only ended in October 1897.

The 1896 Uprising in the Goromonzi / Enterprise area

This article concentrates on the area from the Chinamora Communal lands around Domboshava and Makumbe Mission to the north east of Harare, through Chishawasha to the Enterprise valley and down to Goromonzi and across the Mutare Road, to the Seke and Manyame (formerly Hunyani) River in the south and to Marondera in the east.

Europeans present in the Goromonzi district

At this time, the Mutare (formerly Umtali ) Road was the main supply route into the country from Beira; the Beira Railway contract had been signed in August 1895, but the two foot narrow gauge railway had only reached Macequece (now Manica) and only reached Umtali in February 1898. Along this road were a few isolated stores and farms; the Ballyhooley Hotel on the Ruwa River, Law’s store ten kilometres further on and after the present-day Goromonzi turnoff, Graham and White’s store near Bromley and White’s Farm, south west of Old Marondera (Ruzawi School today) The only concentrations of Europeans were the Jesuit missionaries at Chishawasha and scattered prospectors and miners on the Enterprise gold field.

Chieftainships

The paramount Chiefs were Seke, Chikwakwa and Kunzwe; their kraals were built on granite kopjes chosen because they could be of defended against Ndebele raiders and these men were the backbone of the Mashona uprising.

Seke’s main kraal under Headman Daramombe was at Cheshumba where the Manyame River (formerly the Hunyani) was joined by the Musitkwe River; Headman Simbanoota’s kraal was on a small tributary of the Ruwa River, south of the current Mutare Road and Headman Chiremba was near the present Cleveland dam and Headman Besa in the current Coronation Park area.

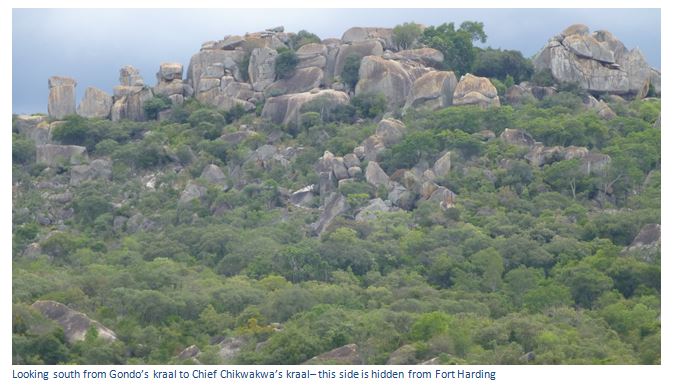

Chief Chikwakwa was four kilometres south east of present day Goromonzi on the western side of the kopje; his Headman Gondo lived a kilometre north in another kopje and Headman Mashonganyika was six kilometres south west of Chikwakwa and closer to the Mutare Road (A3) All their kraals had been built with an eye to defence from Matabele raiders close to prominent granite kopjes.

Chief Chikwakwa’s brother Kahiya lived near Mashona Kop fourteen kilometres to the north and Chief Kunzwe lived about eight kilometres east of Chikwakwa’s kraal on the west bank of the Nyagui River close to Shanguri Hill.

The spirit mediums played a very significant role and Kaguvi, the Shona Mhondoro, or spirit medium, had lived at Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal; indeed had married a woman of Headman Gondo’s kraal and a daughter of Chief Mashingombi, whose kraal on the Mupfure River (formerly Umfuli) lay between Beatrice and Hartley Hill. This became the hot bed of the Mashonaland Uprising. Mkwati, who had escaped arrest at Intaba Zika Mambo, also found his way to Chief Mashingombi's kraal, and this area was also the home of the Chaminuka oracle. The spirit mediums, as well as driving out the Europeans, sought to re-establish the powerful Rozwi Rule, an accomplishment that would have, perhaps, unified the Shona.

Mashona Uprising

The stage was set for a bloody uprising and on 15 June 1896, at Chief Mashingombi’s kraal, Native Commissioner Moony was killed and two prospectors, Stunt and Shell were captured and thrown to the crocodiles in the Mupfure River (formerly Umfuli) The following day, murders took place at Beatrice Mine and on the 17th Joseph Norton's Porta Farm was attacked and his entire family was murdered along with three employees. The Hartley Hill laager was attacked on the 18th June by warriors from Mashingombi's Kraal. The same night the African Christian martyr, Bernard Mizeki, considered a “sell out” was also killed. Nesbitt’s ‘Mazoe Patrol' reached the laager at Alice Mine on the 20th June and rescued the survivors, but Herbert Eyre and Trooper Arthur Young of the MMP were murdered on 21 June in Mvurwi (formerly Umvukwes) Across to the east, Chief Makoni launched attacks on the Headlands laager, which was abandoned, the occupants making their way to Umtali (now Mutare) More farm murders took place in the Marondera and Charter district, mostly of farmers who had settled in the area.

On the 19th June the Native Commissioner Alexander Campbell rode out to warn Europeans in the Goromonzi district of the uprising and reached the Ballyhooley Hotel on the Ruwa River before riding onto his younger brother George’s farm near Mashonganyika’s kraal where he had a friendly meeting with Chief Chikwakwa.

An hour later, on returning to his brother’s farm, he saw his brother George struck down and killed by Headmen Gondo and Mashonganyika, and only just escaped by horse with Charles Stevens, his companion. A.J. Dickinson, a tailor and A.T. Tucker, the barman at Ballyhooley, H. Law of Law’s store and J.D. Beyer, a local farmer were all killed as they approached Campbell’s farm. Dr Orton, a chemist and his wife were ambushed, but abandoned their cart and escaped by horse aided by a local cattle inspector, Manning and three loyal Africans.

At Graham and Whites’ store near Bromley, a passing traveller, Lieut. Bremner of the 20th Hussars was killed and White left grievously wounded. He was rescued by an African Catholic catechist, Muletto who tried to take him to the Wesleyan Mission (now Waddilove Institute) but was waylaid by the same force and White, Muletto and two African children killed.

In the Enterprise gold field, J.D. Briscoe and four African workmen were murdered; two others were thrown down a mine shaft, but survived to give evidence later. White’s partner, H. Graham, a transport rider called Milton and another European and two Indians were killed near Law’s store.

Some 118 civilian casualties were killed in attacks that took place on isolated mining camps and farms running in a broad crescent from Hartley in the West, north to Mazoe and east to Makoni's area. By the end of the day on the 20th June the country outside Salisbury (now Harare) was abandoned, except for Chishawasha Mission where the Jesuit missionaries, joined by miners and prospectors from the Enterprise gold field, were just about to leave for Salisbury when Father Biehler arrived with ammunition and a small detachment of BSA Police. They fortified the mission house and resisted several direct attacks for five days before abandoning the mission and leaving for Salisbury (now Harare) On the 29th June, the eight Jesuits returned with ten European and ten African Police to find the mission unharmed and Chishawasha became the only Police post east of Salisbury.

List of European Civilian and Military Casualties during the Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga | |||||||||

Civilians | Local Forces | Imperial Troops | Total | ||||||

Deaths | Wounded | Deaths | Wounded | Deaths | Wounded | Deaths | Wounded | ||

Killed in Action |

|

| 9 |

| 5 |

| 14 | 0 | |

Died of wounds |

|

| 3 |

| 2 |

| 5 | 0 | |

Reported murdered | 114 |

| 3 |

| 1 |

| 118 | 0 | |

Accidentally killed | 1 |

| 3 |

|

|

| 4 | 0 | |

115 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 141 | 0 | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

Wounded in action |

|

|

| 41 |

| 18 | 0 | 59 | |

Accidentally wounded |

|

|

| 2 |

|

| 0 | 2 | |

Other wounded |

| 8 |

| 1 |

|

| 0 | 9 | |

Other died | 2 |

| 6 |

| 1 |

| 9 | 0 | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||

117 | 8 | 24 | 44 | 9 | 18 | 150 | 70 | ||

Mashona tactics

The Mashona warriors retired to their kopje strongholds, initiating little offensive action and confidently expected the Europeans to withdraw completely from the country. Clearly, the campaign was well-organised and co-ordinated, but lacked the conventional military strategies of the Ndebele.

European tactics

Initially, the European population followed the example of Bulawayo and went into laagers established at Forts Salisbury (Harare) and Charter and later at Umtali (Mutare) Fort Victoria (Masvingo) and even Melsetter (Chimanimani) A strategy of initially rescuing settlers in the outlining areas, followed by mounted patrols burning Mashona kraals, capturing livestock and collecting grain was followed. Usually the kraals were found deserted with the true strongholds within neighbouring caves where the defenders had an advantage by never showing themselves and shooting at the attackers as they climbed into the kopjes.

Capt. Taylor’s Natal Troop burnt down Headman Chiremba and Besa’s kraals and Capt. J.F. Taylor’s Patrol killed Headman Chiremba near Chishawasha.

On 25th June two Mounted Infantry companies under the command of Col. E.A.H Alderson of the Royal West Kent Regiment had arrived in Beira, originally destined for Matabeleland. These companies were diverted to the Mashonaland crisis where they pursued a 'commando' styled mounted campaign against rebel Mashona strongholds, relieving them of their grain and cattle and burning down the kraals.

Alderson's first major offensive, with two companies of Mounted Infantry, was against Makoni's Kraal on 3 August; he established Fort Haynes in the process. Makoni was only captured on 4 September, during a second raid, tried by Court Martial, and summarily executed by firing squad, an act which was not without its controversy. A major skirmish took place at Headman Simbanoota's Kraal between 8 – 14th September, but Alderson’s forces were beaten off, and another against Chief Mashingombi's kraal on the Mupfure on 5 October, but the stronghold was not taken. These were followed by offensives against Chiefs Mapondera, Gatsi, Chikwakwa and Tandi's Kraals during the ensuing month.

Alderson was much criticised because no 'thorough punishment' had been inflicted on the rebels; those responsible for brutal murders had not been arrested, nor had the rebel chiefs, except for Makoni, been brought to justice.

By November, the rains were about to break and the military situation was unchanged. In Matabeland, the rebellion, or Umvukela had come to an end with the indabas between Rhodes and the Matabele Indunas. Rhodes and Earl Grey, the Administrator, came to Salisbury (now Harare) to arrange the withdrawal of Imperial Forces to Beira after their five month campaign. During this time the Mounted Forces had relieved the towns, freed them of fear of further attack and restored the road links between the towns, including bringing supplies from Beira. The effects of the rinderpest were still being felt and the railway from the south only reached Bulawayo in November 1897.

The first detachment of the new BSA Police force, 180 strong, arrived in Salisbury on 10th December 1896 and Lt. Col. F.R.W.E. de Moleyns and Sir Richard Martin took over from Alderson two days later; by this date the Mounted Infantry were already travelling to Beira. From then on all military operations in Mashonaland were carried out by the BSA Police and the 7th Hussars who stayed on until the 7th October 1897.

Preliminary events to the attack on Chikwakwa’s kraal

Maj. C.W. Jenner had burnt the deserted huts of Chief Chikwakwa in August, but he and his tribe had escaped into the nearby fortified kopje. On 16th November Campbell and Jenner with a force of nearly 400 camped nearby his kopje stronghold and attempted to persuade him to surrender. Chief Chikwakwa remained behind his defences shouting down to Campbell and Jenner at the foot of the kopje for two days without success and the same happened at Chief Kunzwe’s kraal east on the Nyagui River. Another unsuccessful attempt was made between Father Biehler and Earl Grey’s private secretary, H. Howard with Daramombe, Seke’s Headman, at Cheshumba.

With the failure of the talks, Maj. Jenner proposed building a fort and although his advice was not acted upon for three months, a BSA Police post under Lieut. Harding was set up at the Ballyhooley Hotel site, near the Ruwa River.

By the end of 1896, the authorities had at last recognised the importance of the spirit mediums to the Mashona cause. Lord Earl Grey wrote to his wife, “Kaguvi is the witch-doctor who is preventing the Mashona from surrendering.” Whilst a Native commissioner in the Salisbury (now Harare) wrote, “If we capture Kaguvi, the war is over”. From then on the military began to exert increasing pressure on the areas where Kaguvi and Mkwati had set up their headquarters.

Kaguvi decided to leave his base at Chief Mashingombi's kraal and forewarned by the Jesuits, Lieut. Harding went to headman Cheshumba and offered £100 reward for Kaguvi’s capture. On 10th January, Kaguvi’s wives passed through headman Chiremba’s kraal and stolen cattle were driven through Headman Simbanoota’s kraal. Three days later, Harding and twenty-five BSA Police burnt the kraal down. On 18th January Kaguvi reached Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal and settled in at Headman Gondo’s kraal, a kilometre north.

On 25th January, Earl Grey, H.M. Taberer and Maj. A.V. Gosling had fruitless talks with Chief Seke and finally realised that he was just obeying instructions from Kaguvi. They returned at dawn to Headman Cheshumba’s kraal and dynamited the caves. Then after a day’s rest, the force of seventy Europeans and thirty African BSA Police moved to Chief Chikwakwa’s, set up camp and started building a fort opposite the kopje, to be named Fort Harding, after its first commander.

In his book Far Bugles Colin Harding gives very little actual detail of events…he tends to focus on the individuals. In this case, Father Biehler from Chishawasha Mission and Hubert Howard who accompanied him. He describes his first visit to Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal and being spotted by the sentinels posted on the top of the kopje and hearing their alarm calls long before they arrived, the sentinels soon being joined by armed tribesmen. They halted and dismounted in the open, being under the impression that Chief Chikwakwa was inclined to discuss peace. But nothing happened, so after some hours Father Biehler, Howard and Harding left their horses and revolvers behind and walked up a footpath towards the kraal. Harding suggested to their native interpreter that he precede them with a white handkerchief, which he refused to do, saying it was his task to talk and not to fight!

Some three hundred metres from the base of the kopje, the small party halted and called to the tribesmen to come and talk peace and pointed to the armed troopers they had left behind them. The reply was that they could not be heard and to come closer, which they did; whereupon a party of armed tribesmen came down the hill and halted one hundred and fifty metres away. The Chief was asked to leave his men and come forward to talk but would not as he was afraid he would be captured and taken to Salisbury. Messengers came forward armed with assegais, but not guns and Harding, as the BSA Company representative, told them that if they surrendered their arms and any persons suspected of carrying murder, they would be permitted to return to normal life and the fighting would stop. They talked for hours, all the time the messengers getting closer and closer and gradually less suspicious. Eventually the messengers said they would take the message to the Chief; but that is the end of Harding’s account of Chief Chikwakwa. In his defence it must be said that Colin Harding wrote his book in 1932; thirty-six years after the event and perhaps he no longer had no wish to recount the details.

Fort Harding – attacks on Chikwakwa / Gondo / Mashonganyika

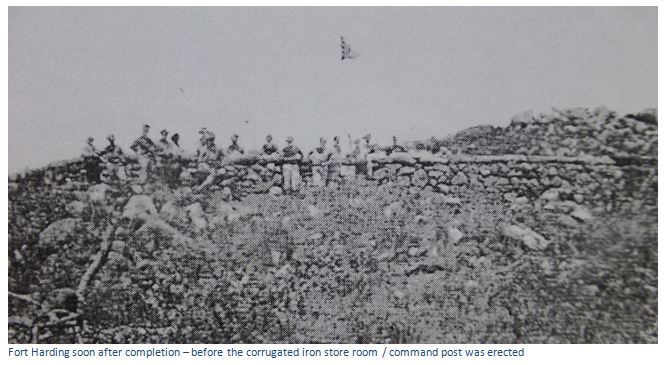

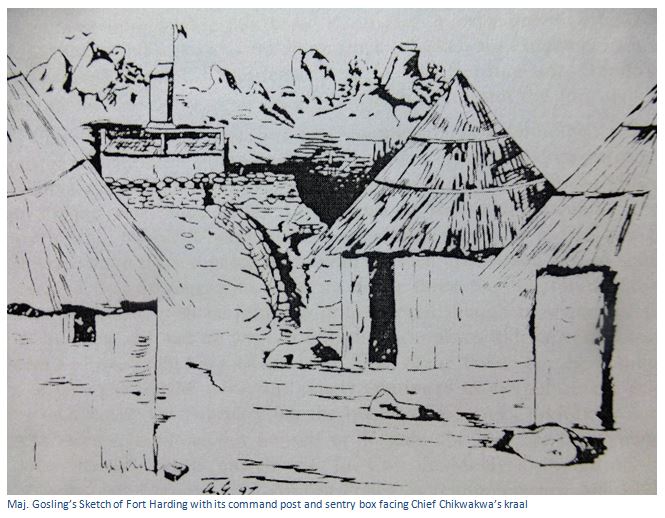

The fort was a rough square about 15 metres (50 feet) across, made of low walls of piled granite topped with sandbags. It is on a small knoll about 1,050 metres (1,150 yards) west from Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal with steep sides leading down to a stream and has excellent views of both Chikwakwa’s and Gondo’s kraals. Initially with just a single tent, later a strange corrugated iron store room / command post with a thatched verandah and sentry box on the roof facing the kopje was added in the centre of the fort. From its south side, a short road was cleared for the transport of guns and ammunition into the fort and thatched pole and dhaka huts erected for the garrison.

The fort was completed on 30th January 1897, a hand-made Union Jack was hoisted and the scene photographed by E.C. Tyndale- Bristow. Lieut. Harding was left with twenty European and twenty African BSA Police and two seven-pounder guns. The Native Commissioner of Mtoko (Mutoko) arranged a five day truce with Chief Chikwakwa to discuss peace with his people, although his Headman Gondo refused to take part and continued to strengthen his kopje’s defences. When the truce expired on 4th February, Chikwakwa said his “young men” had rejected the peace terms.

On 7th February, Lt.-Col. De Moleyns arrived with thirty BSA Police reinforcements, but Chief Chikwakwa’s men continued jeering at the African Police. On 10th February, Capt. J.J. Roach arrived with an additional forty men and a third seven-pounder gun Shelling commenced on both Chikwakwa’s and Gondo’s kraals from Fort Harding with little result as the Mashona were well protected by the boulders in both kopjes. An additional twenty-five BSA Police reinforcements arrived.

On 16th February at dawn Lieut. Harding led an attack of twenty-nine Europeans and sixty-five Africans on Gondo’s kraal supported by fire from the seven-pounder guns and .303 Maxim gun from Fort Harding. Although the sheer cliffs of Gondo’s kraal look very formidable, there is rising ground almost to their base and the night approach would have been easier than climbing the slopes of Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal. Headman Gondo’s kopje were quickly taken, his cave surrounded and then dynamited and a Police post established which commanded the easiest route to Chief Chikwakwa’s main caves. These tactics also had the advantage that a Maxim gun could fire from the captured position and support the BSA Police force that rushed and successfully captured Chief Chikwakwa’s main caves without loss. A week later, Maj. Gosling attacked Headman Mashonganyika’s to the south west of Fort Harding, but did not capture the kraal.

Despite this success, all the leaders of the Mashona rebellion escaped. The spirit medium Kaguvi went north to Swiswa, on the edge of the Chinamora communal lands, whilst Chikwakwa sought refuge with Kunzwe east on the Nyagui River, Gondo and Zhante were at Tafuna Hill, near modern day Shamva.

The aftermath

After this the district was quiet for five months. Maj. Gosling led patrols through Chinamora and Makumbe Mission area, while Lieut. Harding did the same in the Murewa area and in a sharp action on 19th March at Domborembudzi on the Nyagui River; Zhante’s four sons were killed.

On June 19th Maj. Gosling returned to Fort Harding, presumably when he sketched the curious corrugated iron command post with thatched verandah topped by a sentry box facing the kopjes. He was accompanied by a formidable force of one hundred sixty European and one hundred African BSA Police and three seven-pounders and took Headman Mashonganyika’s stronghold to the south west of Fort Harding, dynamiting the caves so that only Mashonganyika’s son Wampe escaped alive. Tpr. Close was killed in this action.

The same day Kunzwe’s kraal to the east on the Nyagui River was stormed. Four African Police and Sgt. W.M. Robinson were killed in the attack, whilst Tprs. S.H. Bennison and G. Irwin died of their wounds.

Fort Harding today

As indicated on the Google earth image above, Fort Harding is 320 metres to the northeast of the cemetery and the track to the Fort goes past the cemetery and leads around the edge of a ploughed field, then in a north easterly direction and to within 20 metres of the fort from where there are faint signs of the track that has been cleared directly up to the fort giving access for the seven-pounder guns and ox-wagons.

The fort is built on a small, natural knoll with steep descents on all sides, except to the south where the thatched pole and dhaka huts for the troopers and mess room were built on the level ground. The steepest descent is on the side facing to the east and Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal which leads down to a stream. The walls are pretty much destroyed with rocks scattered down the steep slopes. The top of the knoll has been levelled off and from Google Earth you can see there the track leading close by the fort. Across the southern entrance to the fort, the cemented remains of the old National Monument plaque can still be found attached to a rock.

Another rock on the track looked like it might have been chipped by an ox-wagon wheel, or a seven-pounder gun.

Both Chikwakwa’s and Gondo’s kraals are easily observed from Fort Harding. The distance from Fort Harding to Chikwakwa’s kraal it is 1,050 metres. We know the BSA Police had three seven-pounders for the assault and Gondo’s kraal, the furthest away, is 1,700 metres. Those seven-pounders, at least the mountain gun version, had a range of 2,700 metres, so both kraals were within range.

Although the distances do not tie up with Peter Garlake’s; he says the fort is 600 metres (500 yards) from Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal, we measured 1,050 metres (1,150 yards) and Garlake says the cemetery is 180 metres, we measured 320 metres; I am confident we have located the same place.

Although we looked for the detritus of a garrison, including rusted food tins and Martini-Henry cartridge cases, nothing much was found, except pieces of dhaka hut base, thick bottle glass and the base of a Gilbey’s gin bottle. The walls of Fort Harding look as though they may have been deliberately destroyed with the stones rolled down its slopes.

Fort Harding was only occupied for eighteen months from 30th January 1897 until the middle of 1898; the Police post at Kunzwe’s kraal was also abandoned in the middle of 1898 and they were replaced by Fort Enterprise, to the north of Chikwakwa’s and near his brother Kahiya’s kraal at Mashona Kop.

Fort Harding cemetery

This is three hundred and twenty metres southwest of Fort Harding.

There are three distinct cemeteries:

(1) The European BSA Police are within a stone walled enclosure containing six graves, but only two have iron memorial crosses, without any name details. Garlake thought the crosses were for Tprs. C. Davids and H. White, but does not say why. He also says Goromonzi Police accounts also record the burial of H. Standing in 1901, but there are no further details. The cemetery is very overgrown with trees; the first two graves on the west side have been outlined with bricks, the other four in the row with small stones which are still just visible. The last two of these photos show that the low stone wall that surrounds the cemetery is still in good condition.

Bennison | Sydney H. | 416 | Tpr | BSAP | KIA | 22 June 1897 | Died from wounds received on 19 June 1897 during the storming of the stronghold at Kunzwe’s kraal. Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Brady | John Charles | 53 | Tpr | BSAP | KIA | 23 February 1897 | Killed at Chininyika's kraal. Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Close | John | 424 | Tpr | BSAP | KIA | 19 June 1897 | Killed at Mashonganyika's kraal during the attack on 19 June 1897. Also recorded as Closs. Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Davids | Charles | 190 | Tpr | BSAP | DOAS | 23 April 1897 | Died of fever at Fort Harding (Chikwakwa). Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Hales | A.J. | 444 | Tpr | BSAP | DOAS | 5 December 1897 | Died of fever at Kunzwe’s. Place of burial not known, but the obvious place is Fort Harding, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Irwin | George | 519 | Tpr | BSAP | KIA | 22 June 1897 | Died from wounds received on 19 June 1897 during the storming of the stronghold at Kunzwe’s kraal. Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Robinson | William Miller | 492 | Sgt | BSAP | KIA | 19 June 1897 | Killed at Kunzwe’s kraal. Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

White | Harry | 174 | Tpr | BSAP | DOAS | 23 April 1897 | Died of fever at Fort Harding (Chikwakwa). Buried at Fort Harding cemetery, 2.5 kilometres south east of Goromonzi Police station. |

Although there is the space within the boundary wall for two rows of six graves each, we only managed to positively identify six graves in a single row. Seven of the eight victims of fighting, or disease, died within the period February to June 1897; only Trooper Hales died later in December 1897. It would appear likely that all eight victims were buried together at Fort Harding, but the lack of indications for two of the graves remains a puzzle. The two remaining iron crosses are of the type typically used in the Harare main cemetery at this time and are more ornate than those put in place by the Pioneers and Early Settlers Society, however unfortunately they lack any details of the person who is buried in the grave.

(2) The graves of the four African BSA Police are adjacent to the walled enclosure and were formerly surrounded by a hedge. They were killed in action at the assault on Kunzwe’s kraal, but their names are not known. The wooden name plaques were frequently eaten by termites, or burnt in veld fires.

(3) The third is a small family burial ground a few metres to the north of the 1896 cemetery with five burials. Only one has a memorial plaque to William Frederick Ervine, died 23rd September 1959.

In marked contrast to the Fort, the cemetery is in good condition, as being sandwiched between the farm road and the track to Fort Harding has meant bush fires have not caused any damage.

Finally Peace

On 12th July, Headman Cheshumba’s kraal was destroyed; on 14th August Kaguvi’s kraal near Swiswa was attacked, but again he fled prior to the attack.

On 2nd September, de Moleyns, Gosling, Harding, Armstrong and Campbell met with the paramount Chiefs Mangwendi, Kunzwe, Seke, Ruseki and Chikwakwa and concluded peace terms. Native Commissioner Campbell went back to Fort Harding and from September to November 1897 arms were handed in and details taken of those who wished to surrender.

The trial of Zhante, commander of Chief Chikwakwa’s warriors, Headmen Gondo and Mashonganyika was held in Harare. Mashonganyika and his sons Wampe and Rusere were found guilty of the murder of Tucker, Law and G. Campbell and executed, as was Kaguvi, the spirit medium. Zhante and Gondo were imprisoned for eight years for the attempted murder of Native Commissioner A. Campbell; Chief Chikwakwa was found not guilty and chief Kunzwe was never tried.

Warrendale Farm former Police Camp

Because of health problems from malaria, the Police post moved at the end of 1900 from Fort Enterprise on Mashona Kop / Neptune Farms to Warrendale Farm near Goromonzi on the west side of the road leading to Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal. All that remains are the outlines of eight rectangular brick buildings behind a stone gun emplacement.

George Milburn who worked in Arcturus tells of a sporting day at the Police Camp at Warrendale in 1924 at which they had tennis, shooting and fishing competitions. Based on site at the time was the Native Commissioner was Maj. R.C. Nesbitt (1867-1956) who won the Victoria Cross for his Mazowe Patrol efforts in rescuing those at the Alice Mine during the 1896 Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga.

Warrendale Farm Police Camp was occupied from early 1901 to at least 1924 before the Police station moved to the present day site at Goromonzi village.

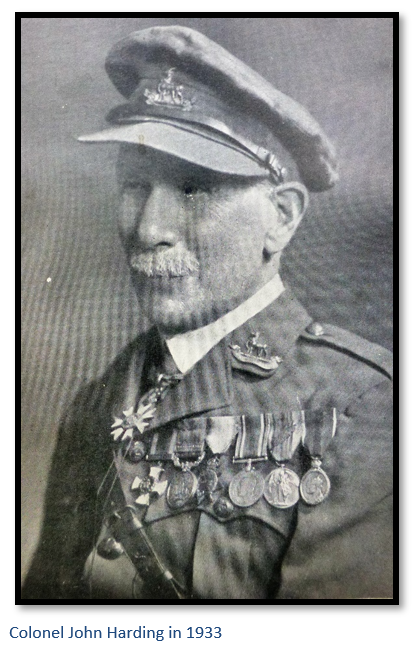

What happened to Lieut. Colin Harding?

Colin Harding was the son of a gentleman farmer from Montacute, Somerset, but found that when his father died that he was not well off; so armed only with a good public school education and a good riding ability, he left England in 1894.

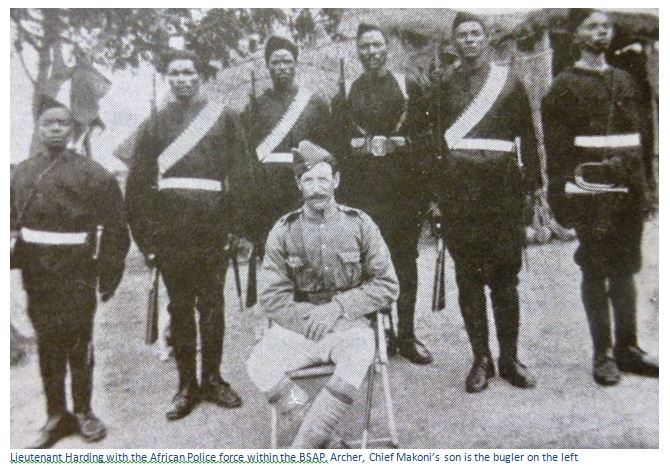

From the Cape he reached Bulawayo, where his first job was as a pit-sawyer’s mate, cutting timber! He then became a brick-layer, before becoming chief clerk in a Bulawayo Solicitor’s office. Finding life dull, he then went gold prospecting with a friend and at the start of the Mashona Uprising / First Chimurenga, he joined the Umtali Volunteers and was quickly promoted from Sergeant to Lieutenant and then Inspector commanding the African Police force within the BSAP.

Lieut. Col. E.A.H. Alderson in his book With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896 gives an account of the attack on Simbanoota’s kraal in which he says curiously: “the worst part was that, having got into the middle of it, we could not in common decency leave ‘til it was over” but goes on to say that “Colin Harding particularly distinguished himself and paid no more attention to the Mashona bullets than if they were snowballs.” In the same book in Chapter XI, Captain Sir Horace W. McMahon, BART., D.S.O. says in clearing the granite range in the Mazowe valley [to the east of the Mazowe Dam] : “The Salisbury Rifles and Zulus on the right with Harding and Ashe, both most valuable officers, whose coolness and daring on every occasion it would be hard to beat, came in for most of the fighting, and drove the enemy back from one position to another, until a determined stand was made in Chidamba’s kraal.”

Harding was a galloper at the relief of the Hartley Fort in October 1896 and gets many plaudits from Lieut. Col. Alderson when at Mashingombi's Kraal after some volleys were fired into a cave by the Mounted Infantry, a child’s voice was heard crying. Harding asked leave to go in, although it meant certain death if the Mashona were still within, but in he went and came out with a little, but perfectly blind, Mashona child in his arms. Again, Harding as a galloper accompanied the Mounted Infantry and Rhodesia Horse and Salisbury Rifles on the Sinoia (now Chinhoyi) and Ayrshire Mine Patrol.

Clearly Harding played a very active and distinguished part in these 1896 events and Lieut. Col. Alderson records he dined with Harding several times before they left Salisbury (now Harare) for Umtali (now Mutare) where the Mounted Infantry sold their horses to the BSA Company due to the rinderpest regulations and walked to Massi-Kessi (now Macequece) before catching the railway down to Beira.

As a Major, Colin Harding was first commander of the embryonic Barotse Native Police force from August 1900 to April 1901. Together with Capt. Carden, he selected a site for a new fort at Monze to replace the old fort which was at an unhealthy site, Chief Monze providing the labour force for the fort’s buildings and ramparts under the supervision of Harding’s deputy, Sergeant Macaulay. Monze is in the southern province of Zambia, located 190 kilometres south of the capital Lusaka on the Great North Road, and is on the route to Livingstone and Victoria Falls.

On his return from an 8 week trek to Bulawayo, Major Harding records that he was treated to a variety of delicacies procured as a surprise by his NCO's, including pigeons, various fowl, milk and meat, from which were produced pies, omelettes and other delicacies. Major Harding then set off with Trooper Lucas and fifteen of the new recruits, taking tribute from Chief Monze for King Lewanika, to Lealui, near Mongu.

On his way to Lealui, Major Harding met his brother William Hallett Harding at Nanzeela mission. William had been acting as Colin’s secretary and had also been commissioned to update and prepare maps for the administration and the Royal Geographic Society. Short of staff, Major Harding gave his brother the command of running Fort Monze and its patrol area.

During the time his brother was away, William Harding visited the copper mines north of the Kafue River and N'kala before returning to Fort Monze on 5th November 1900 and then journeying to Victoria Falls for a survey team meeting. On his return he showed the symptoms of having black-water fever and died Monze at on 11th April 1901.

As soon as he received news of his brother’s death, Major Harding headed back for Fort Monze, where soon after his arrival, Cpl. Franklin also died of black-water fever.

Name | Name, Rank & Unit | Attested | Age | Date of Death |

Alfred William Welch | 636 Trooper B.S.A.P. | 16/03/1989 | 32 years | 4th January 1899 |

Montague George S. Hare | 595 Corporal B.S.A.P. | 26/01/1897 | 32 years | 3rd July 1899 |

Josiah Norris | 348 Troop Sergt Major B.S.A.P. | 01/11/1896 | 30 years | 1st December 1899 |

(Albert)Ernest Rice | 780 Trooper B.S.A.P. | 21/08/1897 | 23 years | 14th February 1900 |

William Hallett Harding | Officer Commanding B.S.A.P. | n/a | 34 years | 11th April 1901 |

Benjamin Chas Franklin | 786 Corporal B.S.A.P. | 29/09/1897 | 28 years | 30th April 1901 |

These deaths from black-water fever led to the temporary closure of Fort Monze, owing to the shortage of officers, before the fort was decommissioned in 1903, the memorial there today being erected in 1904. The location of the cemetery is about 0.6 Km from the Fort Monument.

In 1902, Major Harding escorted King Lewanika of Barotseland to London for the coronation of King Edward VII. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society.

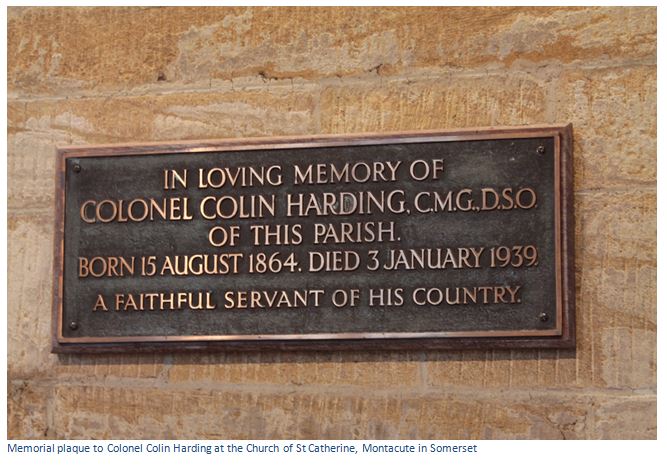

As a Colonel, Colin Harding served in World War I as a Battalion Commander helping to raise the 2nd King Edward’s Horse. When they moved into the trenches at Festubert in the spring of 1915, he was a Major and second-in-command. After a period in the trenches at Messines, he was offered the command of the 2nd Birmingham battalion. He served finally as Provincial commissioner in the Gold Coast Colony from 1918 – 1922. According to an obituary in the Glasgow Herald dated 5 January 1939, he died in a London Nursing Home aged 75 and is buried at Montacute in Somerset. He authored three books including:

Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall. 1933

Frontier Patrols: A History of the British South Africa Police and other Rhodesian Forces. G. Bell and Sons 1937

In Remotest Barotseland. Hurst and Blackett Limited, London. 1904

Above is Colonel John Harding’s memorial plaque at Montacute where he was born and is buried; it seems very modest for a man who was a fine soldier and colonial administrator.

In his book Far Bugles published in 1933 when Harding was 69 his descriptions of the fighting in Mashonaland are diffident and restrained and clearly do not reflect the very real dangers to which he was often exposed. He does not refer to Fort Harding at all; in his book he refers to it as Fort Chiquaqua, but only in passing and in reference to “a lad named Hardwick” who I refer to in my article on Devils Pass. There is a short article on Alfred Arkell Hardwick and his photo in the website www.zimfieldguide.com under Manicaland Province entitled Traveller’s tales from the Devil’s Pass. Before his young life was cut short in an air accident, Hardwick lived a full and adventurous life. Harding writes: “I have seen Hardwick clambering over a stockade far ahead of everyone else, and then with a captured Mashona gun much older than himself, return dirty and glorious to dream of fleeing Mashonas, in his service blanket under the starry canopy.”

Alfred Hardwick later wrote a book describing his travels in West Africa in which the dedication reads: “To Colonel John Harding C.M.G., of the British South Africa Police, to whose kind encouragement when in command of Fort Chiquaqua, Mashonaland, the author owes his later efforts to gain Colonial experience, this work is dedicated.”

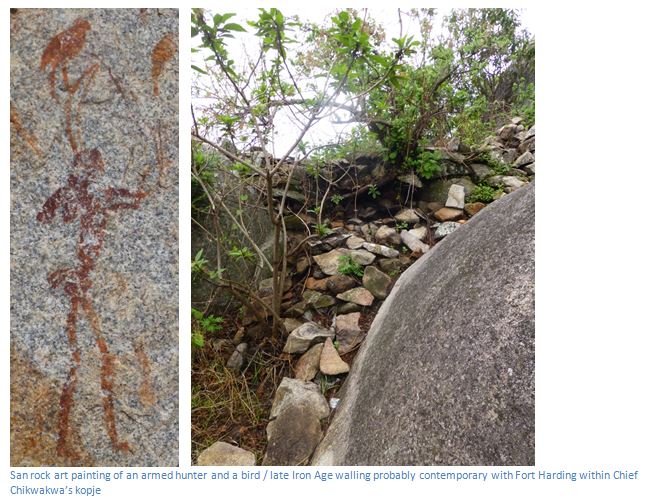

Chief Chikwakwa’s kraal today

Chikwakwa’s fortified kopje is directly east and 60 metres (200 feet) higher than the fort and in a nearby gulley within a stone walled enclosure Maj. Jenner negotiated with Chief Chikwakwa. Beyond are many small caves protected by hastily built stone walling, although the main caves are northeast immediately below the summit and not visible from the fort. Peter Garlake found pottery and rusted tins of non-military type in the main caves which were most likely looted from Law’s store, about fifteen kilometres away. We found numerous old Shona pottery fragments where the kraals were located on the plateau facing Fort Harding and within the main caves. Unfortunately, much rubbish is now being discarded by Apostolic Church members who make fires and camp out in the caves for extended periods.

There are many short sections of late Iron Age dry-stone walling structures which have been built in defensible positions between the boulders and leading up to the main caves.

Directly after taking Headman Gondo’s kraal at dawn on 16th February 1897; Chief Chikwakwa’s main caves were rushed by Lieut. Harding and his force of BSA Police supported by a Maxim gun. The approach they took is in the photo below.

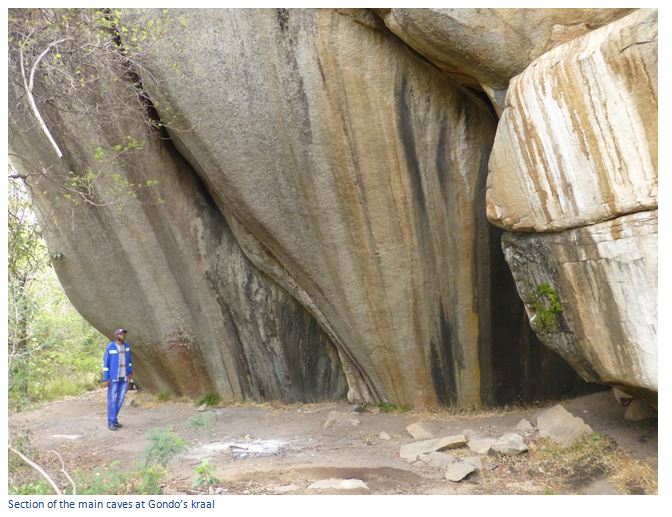

Headman Gondo’s kraal today

The kopje shows of the same attempts at fortification with sections of dry-stone walling at defensible points and intensive habitation with much old broken pottery; signs of an iron-age furnace site were also found with sections of furnace pipe, or tuyeres.

My thanks to Headman Musonza of Goromonzi Growth Point for permission to visit Chikwakwa (Goromonzi Mountain) and Gondo’s kraals and to his son, Duke Musonza, who very kindly guided me; they are both keen conservationists and anxious to halt the tree felling in this very spiritual area.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. The Mashona Rebellion East of Salisbury. Rhodesiana Publication No. 14 July 1966. P1-11

K. McIntosh and L. Norton. Echoes of Enterprise. Enterprise Farmers Association.

E.A.H. Alderson. With the Mounted Infantry and the M.F.F. 1896. Books of Rhodesia. 1971

www.monze.com for information on Col. C. Harding in Zambia

Gordon Rendell for the photo of Col. Harding's memorial at St. Catherine's Church, Montacute

C. Harding. Far Bugles. Simpkin Marshall Ltd, London. 1932

When to visit:

All year around

Fee:

Not applicable

Category:

Province: