Devil’s Pass and Fort Watts

- The Devil’s Pass is almost unknown to people living in Zimbabwe nowadays.

- The construction on the railway line from Fontesvilla, 56 kilometres from Beira began in September 1892. The 222-mile (355 kilometres) link to Umtali (now Mutare) was built with 2ft 0-inch track gauge using 20lb / yard rail and only completed in February 1898 after immense difficulties had been overcome and many lives lost. On 22nd May 1899, the 3ft 6-inch gauge railway link between Umtali and Salisbury (now Harare) was completed; the Umtali Beira line being converted to the same standard gauge by August 1900.

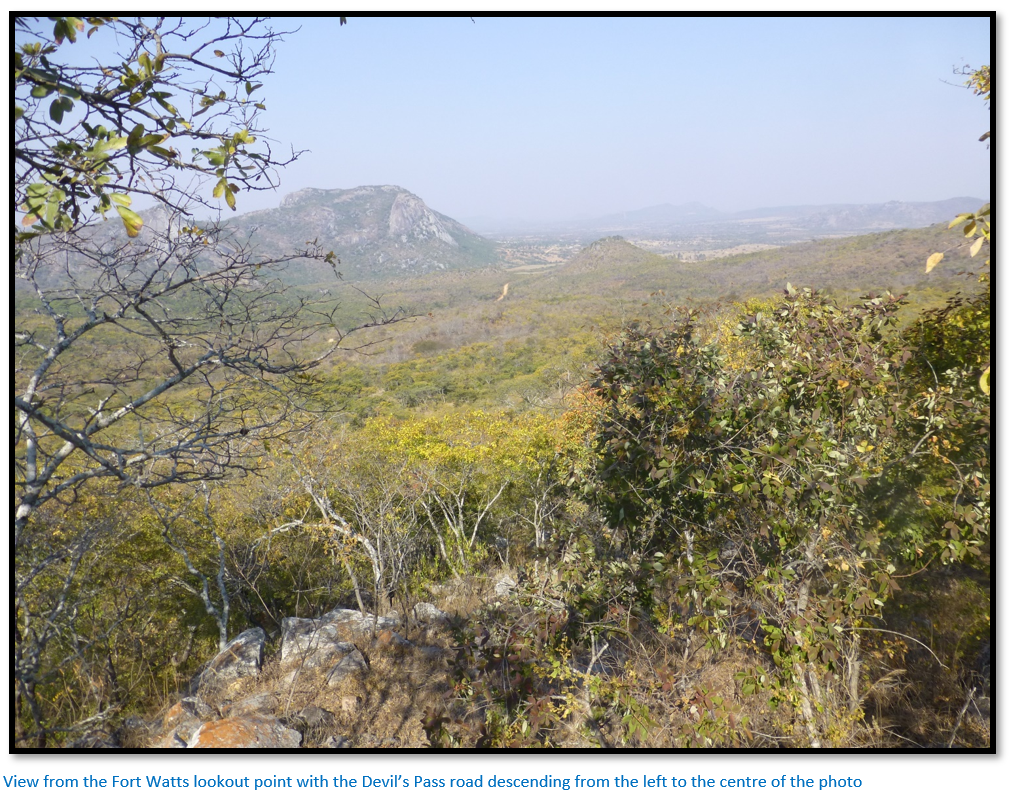

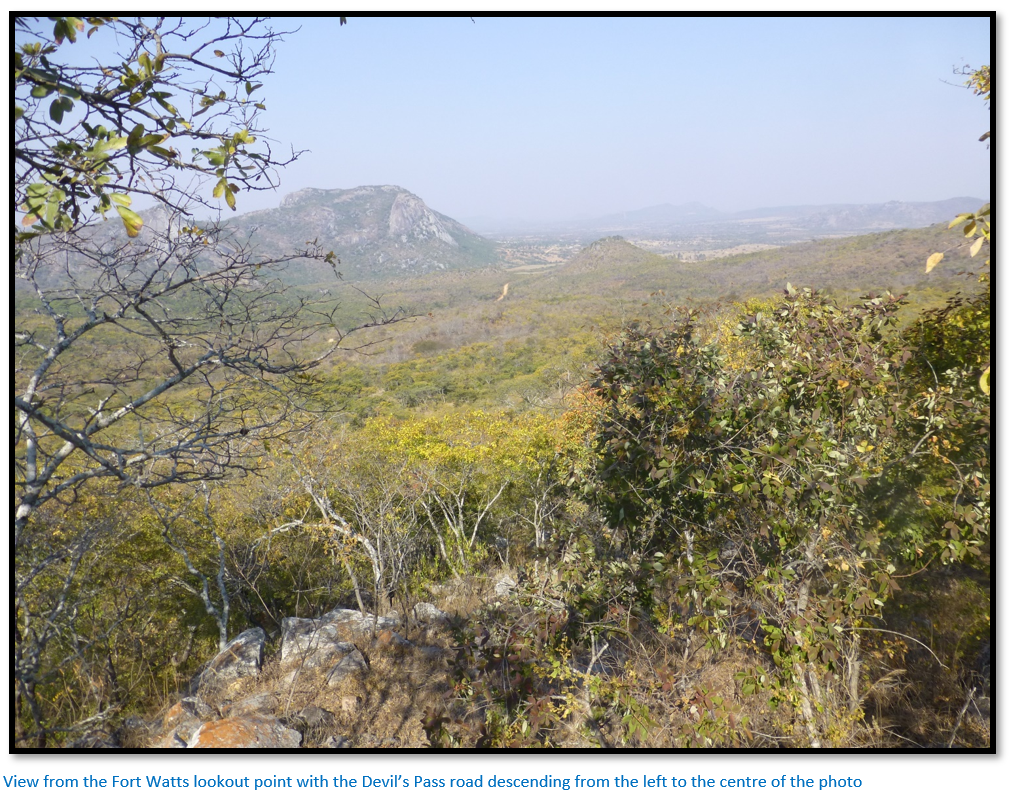

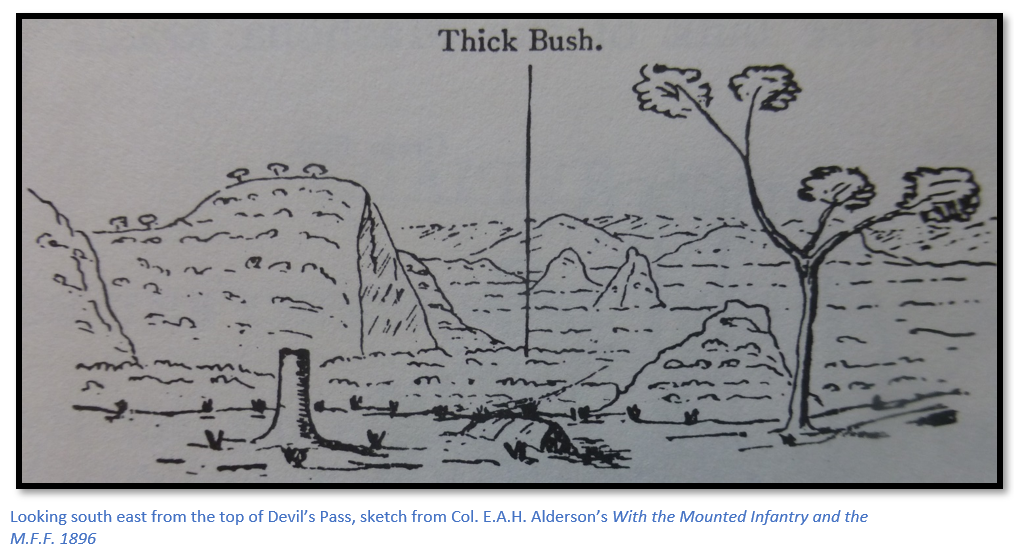

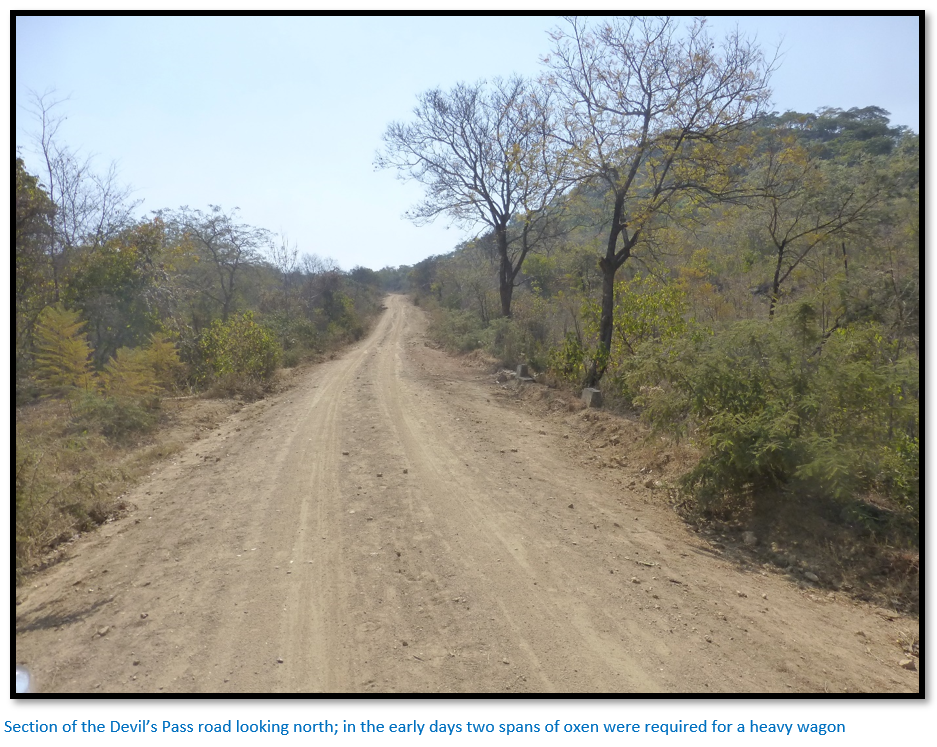

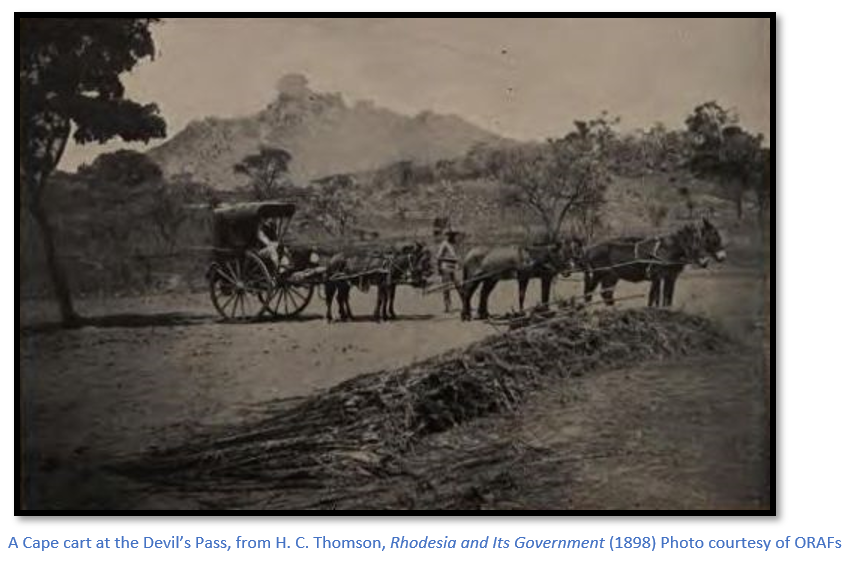

- For the period 1890 to 1899 all traffic between Umtali and Salisbury was by ox-wagon mostly through the Devil’s Pass. The altitude at the highest point of the Pass is 1,446 metres, at its base it is 1,286 metres; so, the oxen had to haul up their wagons 160 metres over a distance of 2.4 KM. This is a formidable gradient for a span of sixteen oxen harnessed in pairs drawing a wagon load of 4 to 5 tons.

- A normal day’s travelling might be 20 KM, but this depended on the rivers and steep inclines that were encountered. At the bottom of the Devil’s Pass one or two teams would be detached from other wagons and each wagon would be double or triple-teamed in order to get to the top of the Pass. This meant that each team of oxen would make two or three trips and needed to be rested when all the wagons were finally up and meant only the 2.4 KM of the Devil’s Pass would be covered in a day. After overnight rain, the trail would be like grease and on these days, there was nothing to do but wait for the road to dry.

- Returning to Umtali down the Devil’s Pass was usually with a lightly-loaded wagon. They had large wood blocks on the rear wheels which were the brakes and were operated by a handle attached to a large turn screw. In addition to the driver and voorlooper, someone had to walk behind the wagon ready to apply the brakes at a moment’s notice to prevent the wagon from rolling over the oxen pulling it. Sometimes twelve of the oxen were moved to the back of the wagon, leaving four to steer the wagon while the remaining twelve held it back, helping the brakes and in the event of a runaway, reduced the number of casualties among the precious oxen.

- The arrival of the railway which followed the watershed to the west was followed by the roads and so the old wagon route through the Devil’s Pass became abandoned and forgotten.

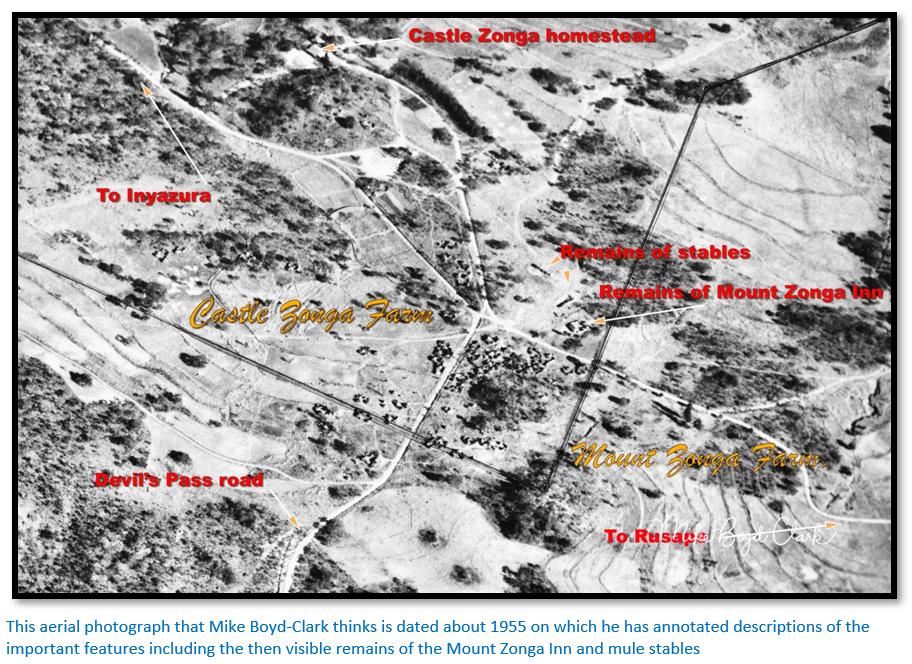

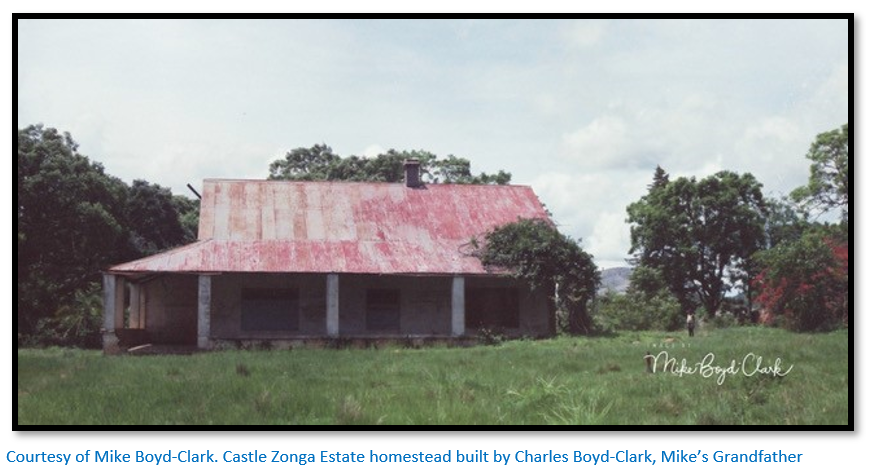

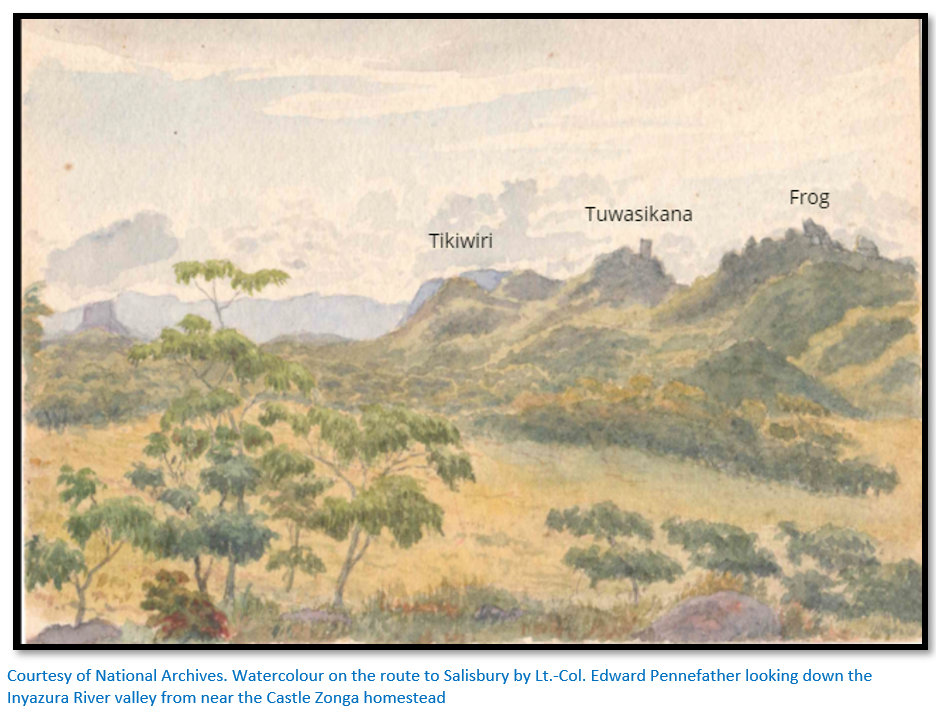

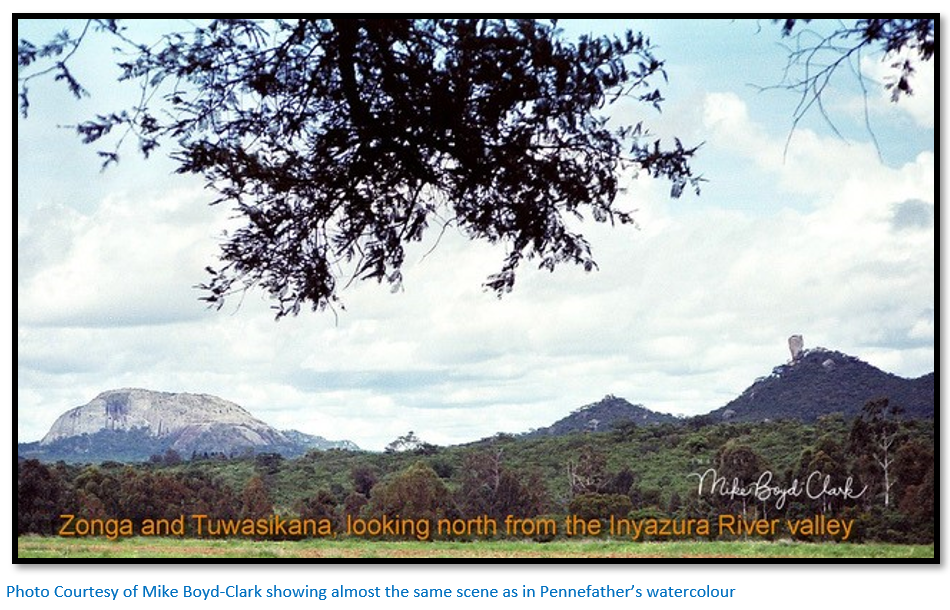

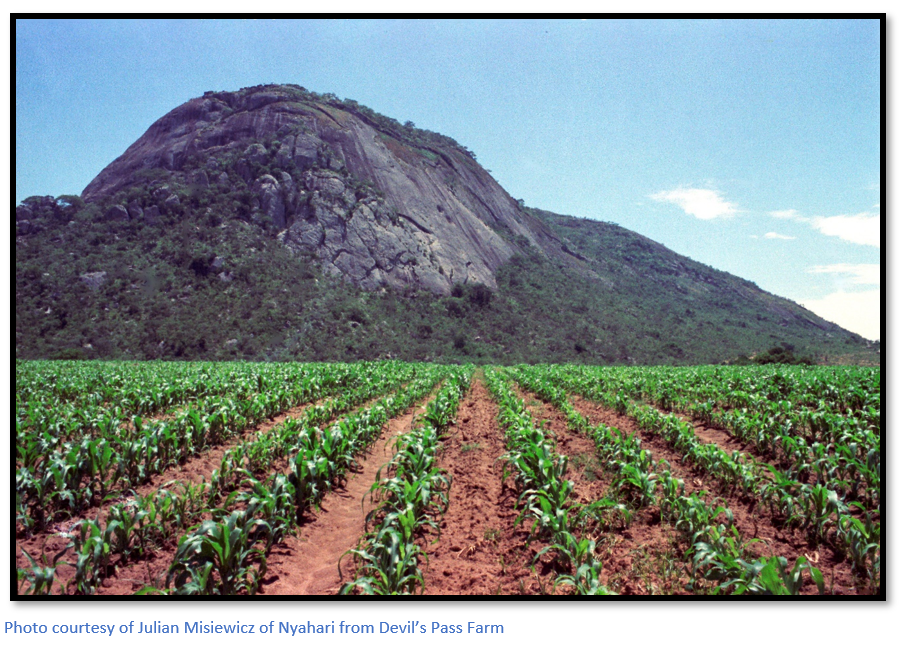

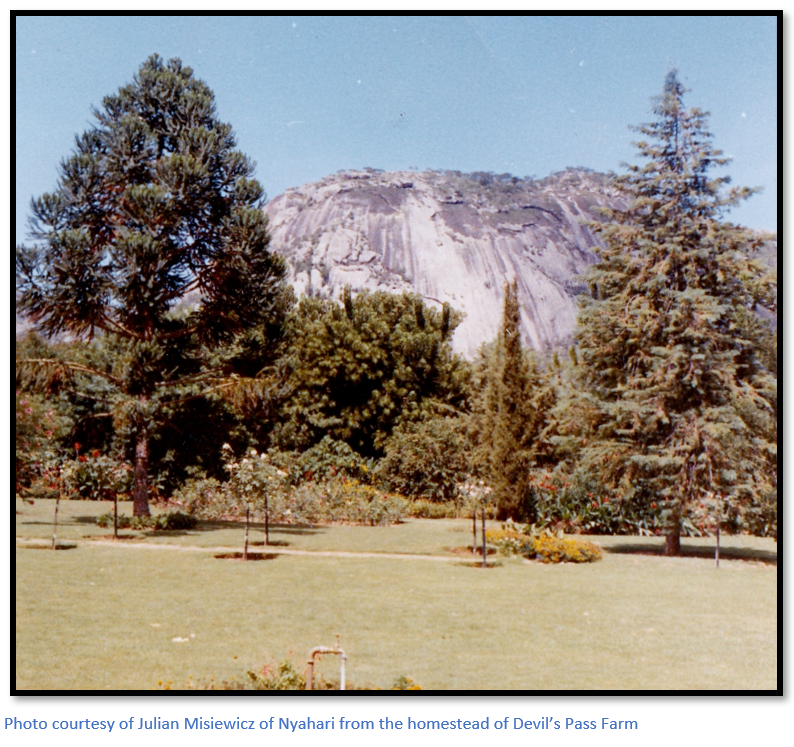

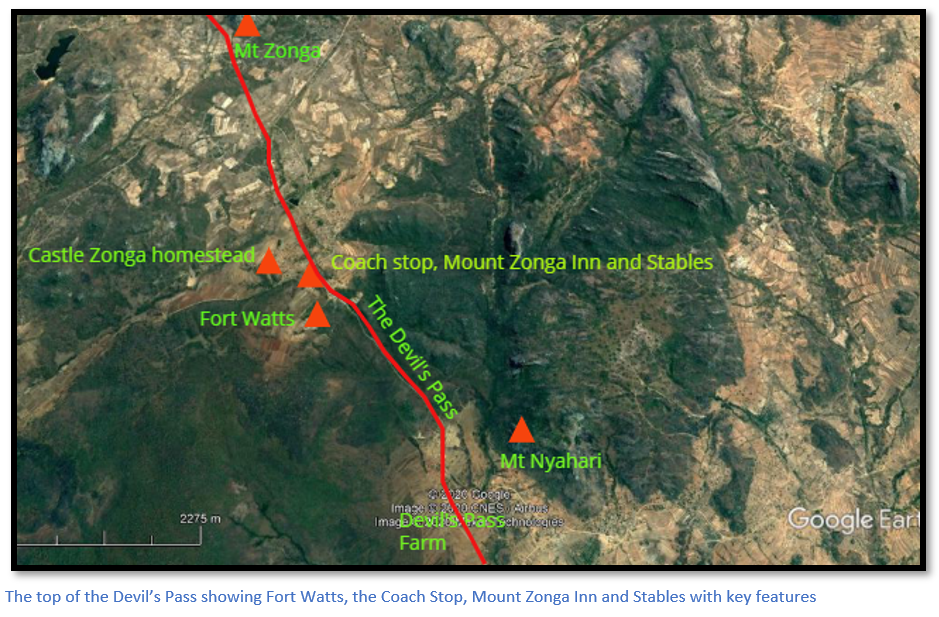

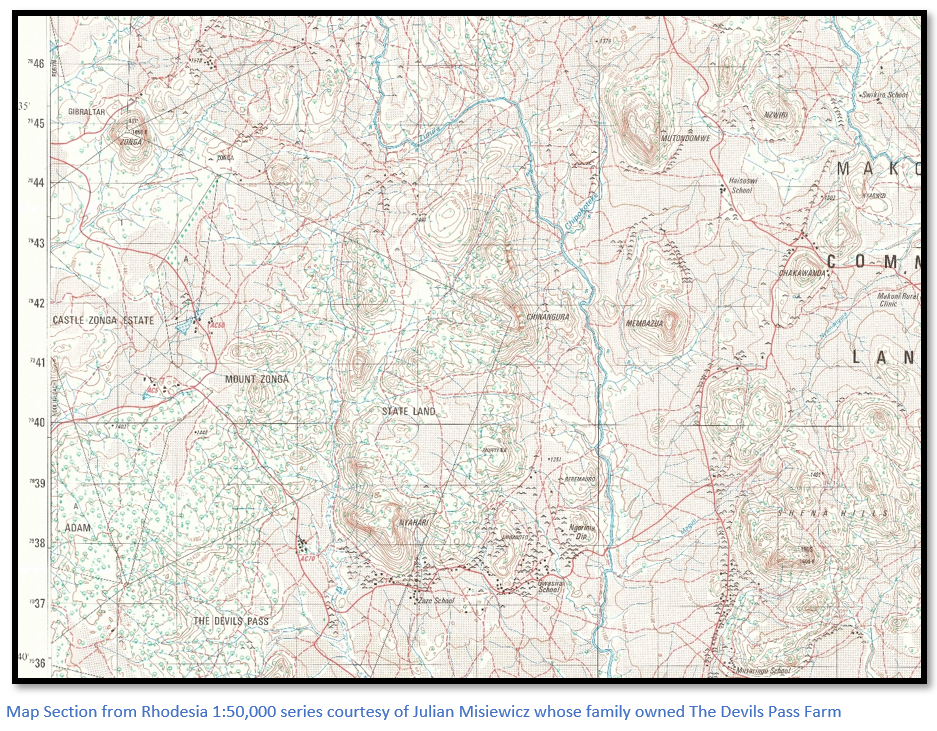

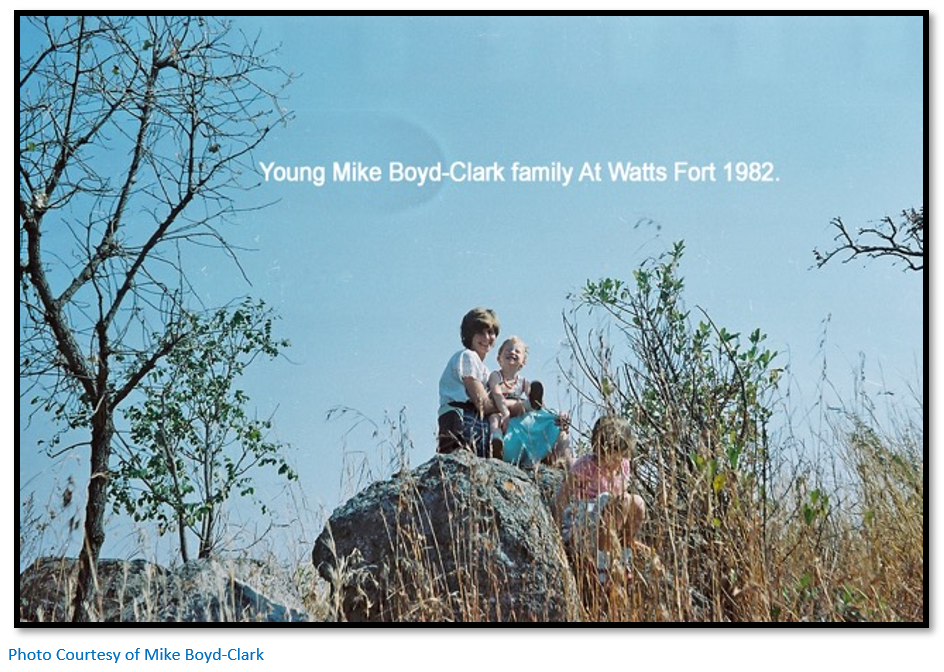

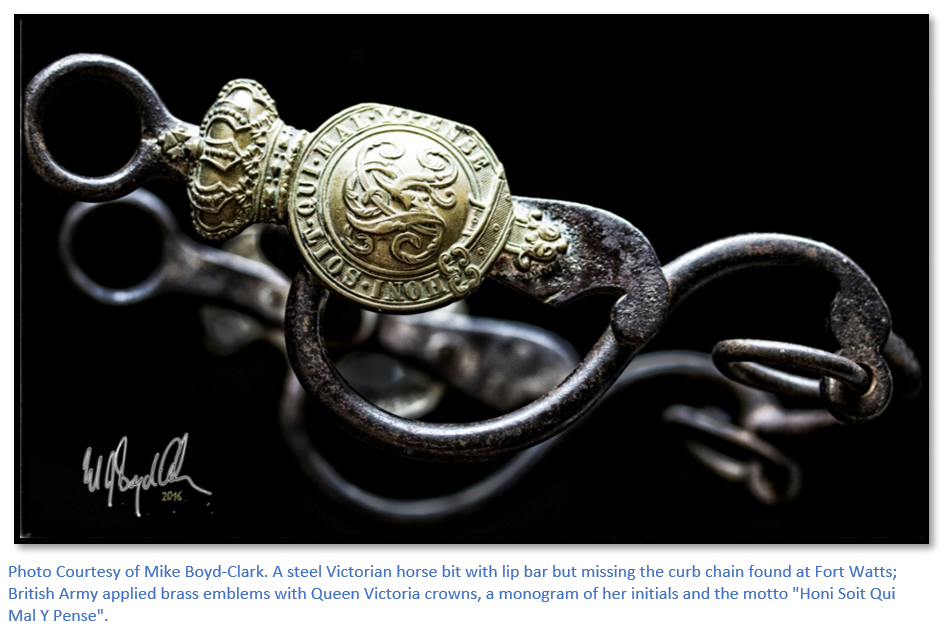

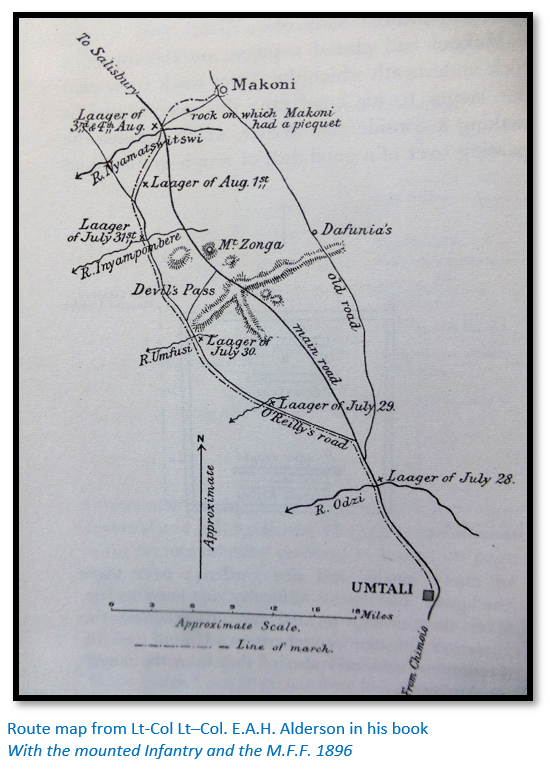

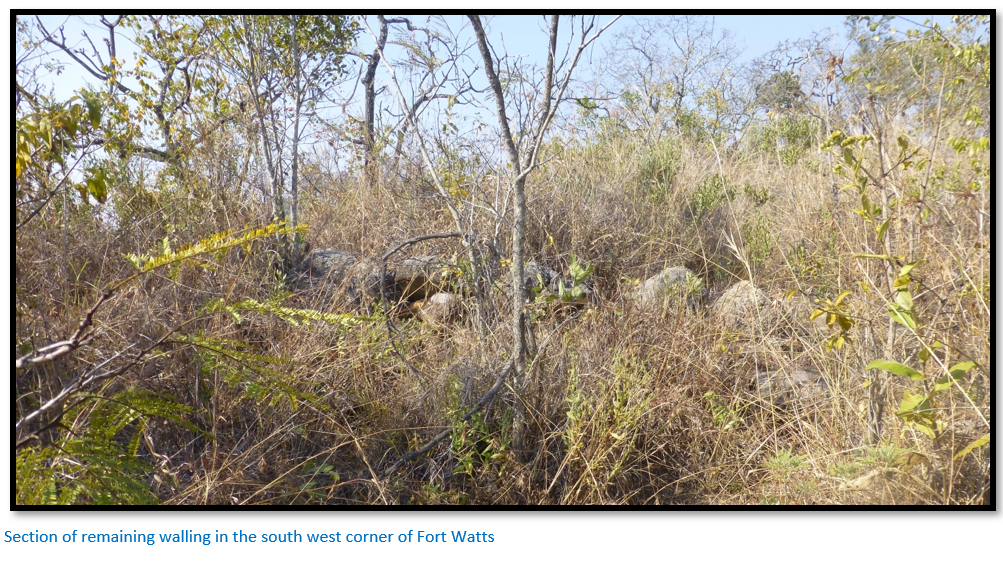

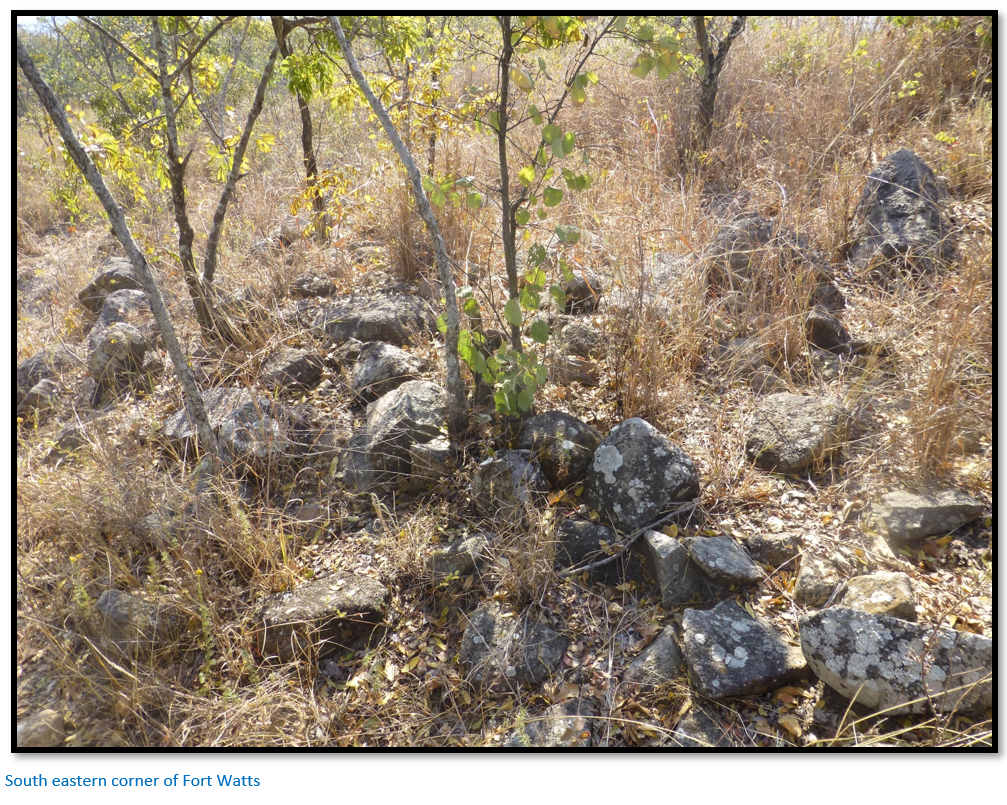

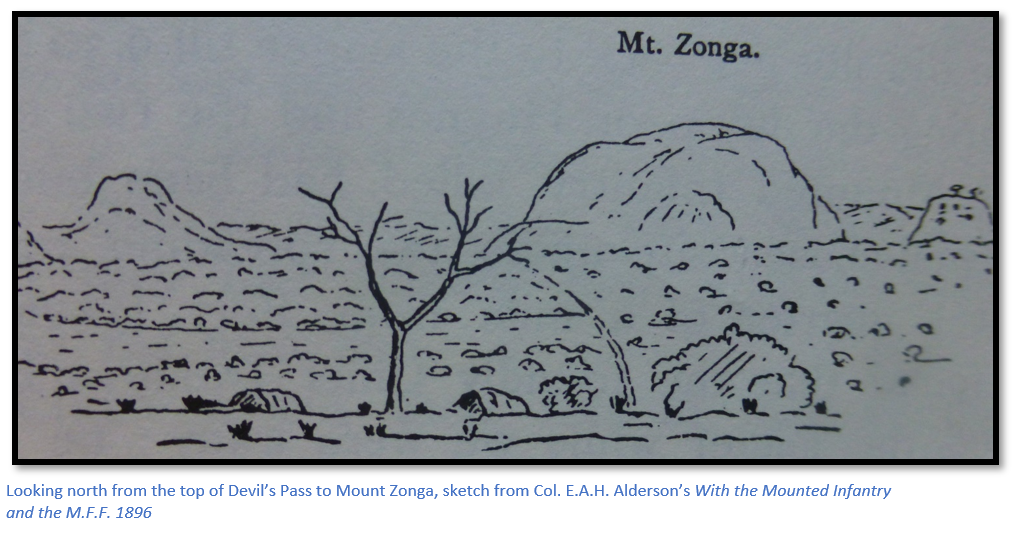

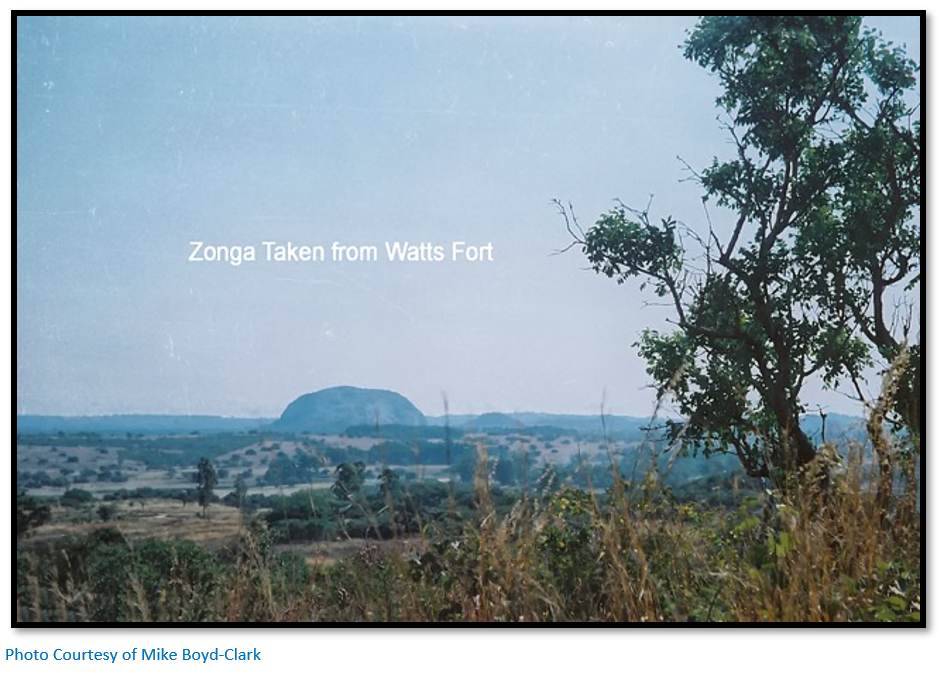

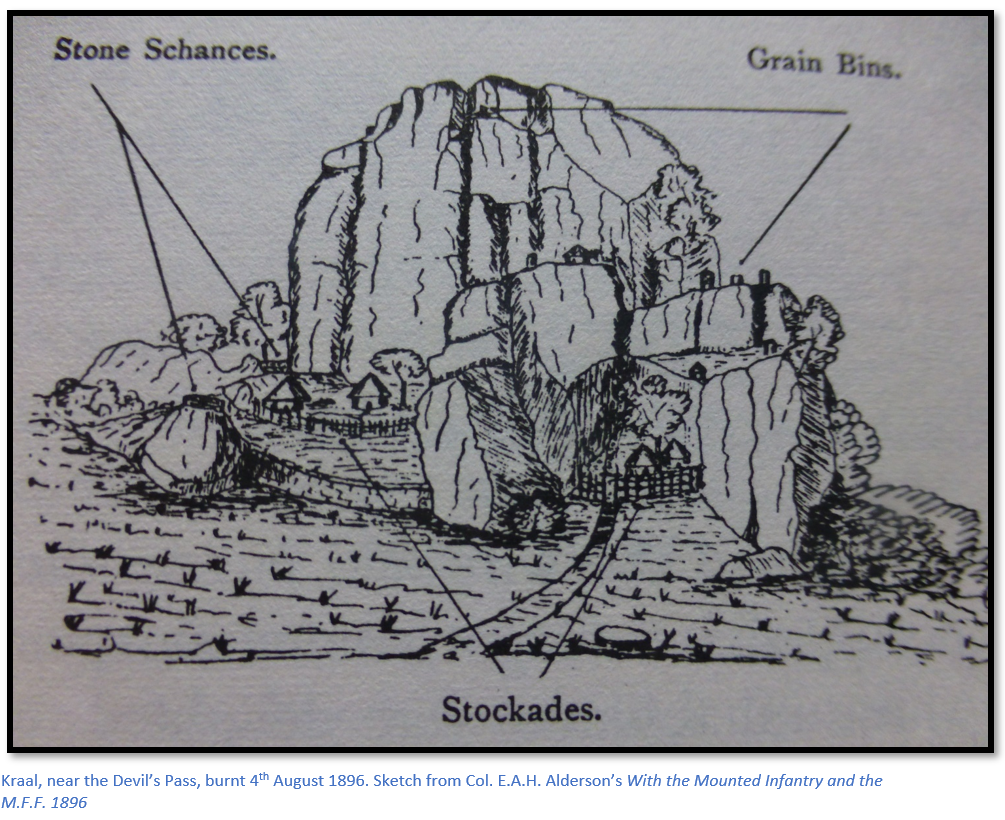

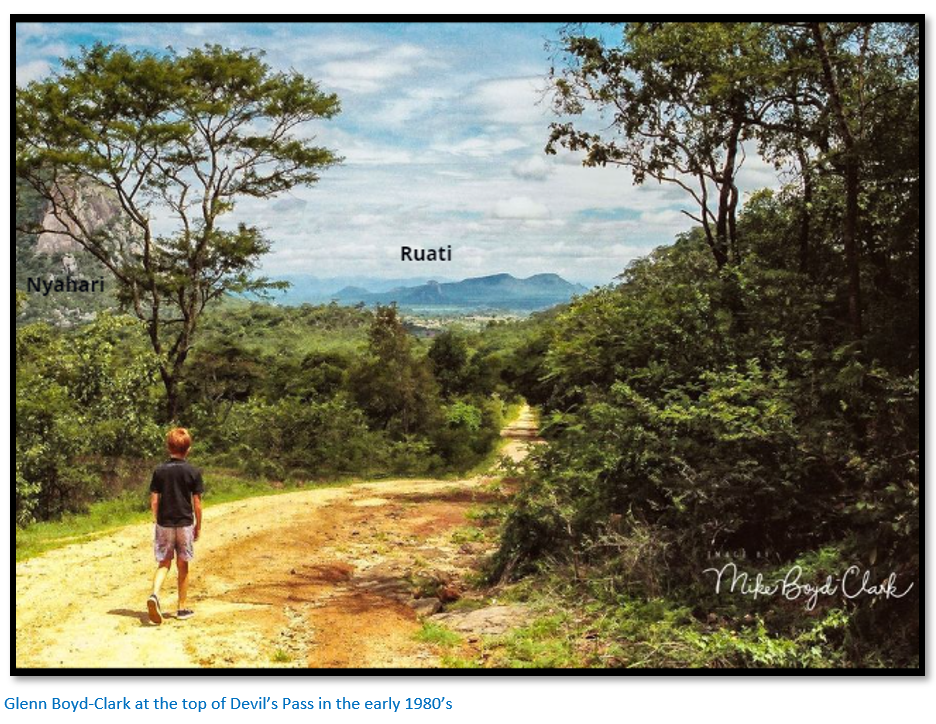

- Fort Watts was built and manned in 1896 by Lt-Colonel Alderson’s Mashonaland Mounted Force and afterwards by the British South Africa Company Police but as far as I know there are no descriptions of the fort and its location has not previously been recorded. Fortunately, Mike Boyd-Clark had good recall and photographs from visiting the site when his family owned Castle Zonga Estate and Julian Misiewicz had childhood memories and photographs from when his family owned Devil’s Pass Farm whose northern boundary was at the base of the Devil’s Pass as can be seen from the 1:50,000 map section which follows. I am very grateful to both for being so generous with their knowledge and photographs.

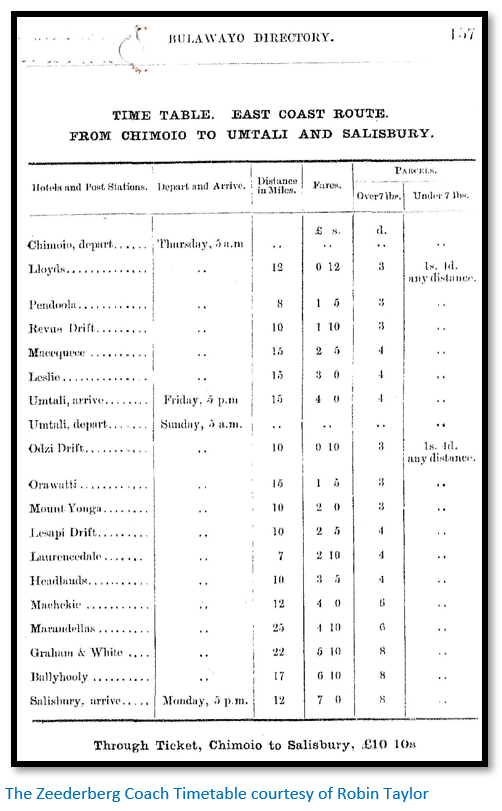

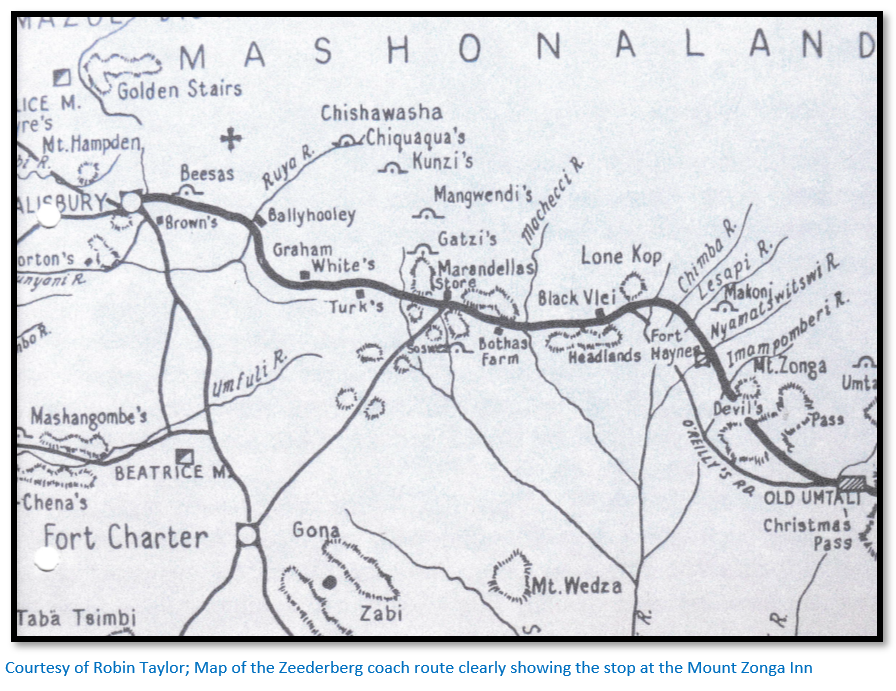

- The Mount Zonga Inn and stables at the head of the Devil’s Pass no longer exist, but I am very grateful to the above two gentlemen for pin-pointing its position so accurately as many travellers in the early days would have dismounted from the Zeederberg Coach at this historic spot and stretched their legs whilst the coach mules were being changed before proceeding on to Salisbury. It was a 36 hour journey from Umtali to Salisbury.

From Rusape take the A14 turnoff to Nyanga. Distances are from the turnoff; 7.5 KM pass on the left the turnoff to St Faith’s Mission, 17.9 KM turn right off the tarred road at the store. 18.2 KM turn right at the intersection heading for Mt Zonga in the distance. 20.5 KM take the left road at the intersection, heading due south, 22.9 KM take the right road at the intersection, now heading south west with Mount Zonga directly ahead. 27.5 KM turn left at the intersection away from Mount Zonga and heading for the Devil’s Pass ahead. 30.1 KM at the intersection turn left into the Devil’s Pass. See directions below for Fort Watts. 32.7 KM emerge from the Devil’s Pass, 33.9 KM continue directly on, 43.1 KM turn left at the intersection, 43.7 KM continue on the main road ignoring turnoffs and heading generally south. 56.1 KM reach intersection and continue on. 60 KM reach intersection and continue south. 66.2 KM reach intersection at Odzi Rapids Farm and continue south. 66.9 KM cross the Chingwandow River; 70.3 KM reach the A3 National Road and turn left for Mutare.

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass road north onto A14 near the business centre: 18⁰32′15.99″S 32⁰16′46.44″E

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass: 18⁰37′52.62″S 32⁰16′39.74″E

GPS ref (approximate) for Coach Stop, Inn and stables: 18⁰37′35.28″S 32⁰16′19.50″E

GPS ref for JB’s grave (approximate): 18⁰37′59.54″S 32⁰16′23.79″E

GPS ref for Fort Watts: 18⁰38′00.24″S 32⁰16′29.69″E

GPS ref for Devil’s Pass road south onto A3 near the Odzi River bridge: 18⁰54′51.08″S 32⁰24′05.22″E

No. of men | Unit | Post | Kilometres from Salisbury |

|

| Salisbury | 0 |

70 | Matabeleland Relief Force | Marandellas No V Fort | 83 |

30 | Umtali Rifles | Headlands No IV Fort | 142 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. | Fort Haynes No III Fort | 176 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. | Devil's Pass (Fort Watts) No II Fort | 197 |

50 | Det. 2 / West Riding Regt. | Umtali No I Fort |

|

70 | Umtali Rifles | Umtali No I Fort | 248 |

30 | Matabeleland Relief Force | Umtali No I Fort |

|

350 |

|

|

|

Miles | Total miles | Kms | Total Kms | |

Umtali | ||||

Odzi Drift | 10 | 10 | 16 | 16 |

Orawatti | 15 | 25 | 24 | 40 |

Mount Zonga | 10 | 35 | 16 | 56 |

Lesapi Drift | 10 | 45 | 16 | 72 |

Laurencedale | 7 | 52 | 11 | 83 |

Headlands | 10 | 62 | 16 | 99 |

Macheke | 12 | 74 | 19 | 118 |

Marandellas | 25 | 99 | 40 | 158 |

Graham and White Store | 22 | 121 | 35 | 194 |

Ballyhooley Hotel | 17 | 138 | 27 | 221 |

Salisbury | 12 | 150 | 19 | 240 |

150 | 240 |