An analysis of Roora

By Jaison Andifasi

These stories of Shona Customs were first published in 1970 and were amongst the best essays received in a nationwide essay competition on Shona culture and tradition. Their authors ranged from a 15 year-old schoolboy to a university student and they came from Sakubva in Mutare to Berejena Mission near Masvingo.

Although more than 50 years have passed since the essays were written and many aspects of Shona customs have changed, it is hoped that the stories will give insight into what many parents and grandparents of the present generation learnt from their own relations in the 1960’s.

Mambo Press, originally established by the Catholic Church at Gweru, publishes a wide selection of books in many subjects and for a wide audience.

Roora is of vital importance because it is an outward manifestation of a young man's love for his fiancée and it is a safeguard against groundless divorce. Roora is also the gratitude that is expressed by the son-in-law to his parents-in-law for the good care and upbringing of the one who is now his wife.

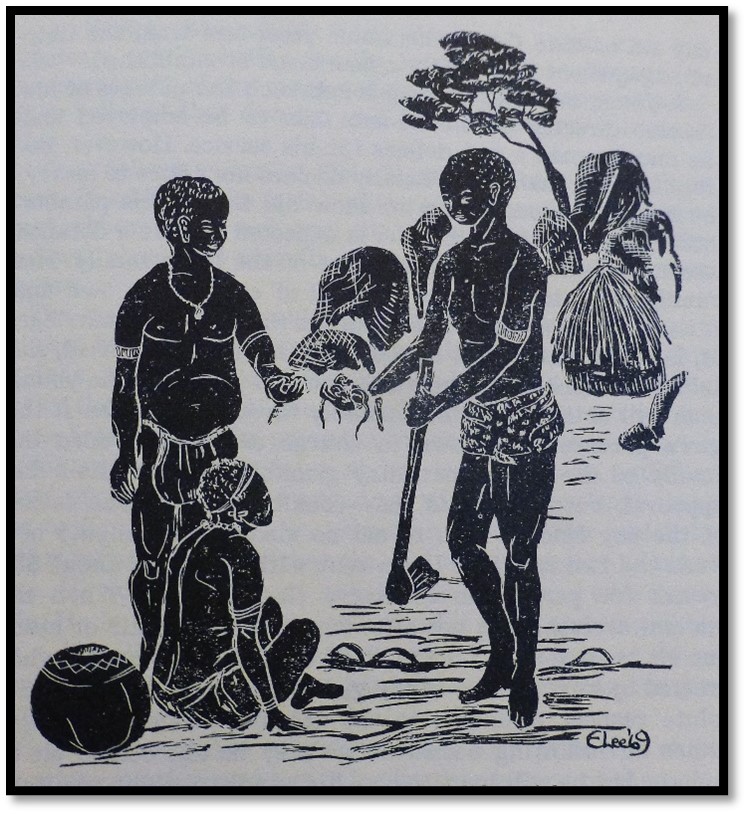

Long ago, roora was very simple indeed. After a young man had come to terms with a young woman of his liking, he would proceed to set traps to catch mice. If he was fortunate and caught three or four mice, he would quickly go to the mother of the girl, present her with the mice and asked for the daughter. The mother, who was usually happy with the gift, presented the matter to the father without responding to the proposal. If the father did not object, the young man was allowed to go away with their daughter as his wife.

Also, in those bygone days, any man fit to marry might marry ‘in advance.’ This was done by carrying a dry log of firewood to a home where a baby girl had been born. This piece of wood was offered to the mother. She would either receive it or refuse it. If she accepted, then the infant was pledged to become the wife of this man when she grew up. This transaction was usually carried out between a poor family and a rich man who wanted more than one wife. The Shona word for this is kuzvarirwa which means ‘to be born for someone.’

When the tribes became more settled and people started cultivating crops and rearing cattle, the manner of paying roora changed. The son-in-law was expected to give five goats and a few bushels of corn to the parents of his fiancée. If he could not afford this, he would have to find at least two goats and then work for his father-in-law for a certain period. Usually this young man would work in the fields of his father-in-law for two or three years before he was given his wife. Most men who married in this way built their homes near their in-laws. This is called kugarira in the Karanga dialect.

It was not unusual to find two families exchanging daughters. No roora would be paid because the two roora cancelled each other. This is referred to as matenganagudo.

Today, many young men and women will laugh and scoff when they hear that three or four mice, or even a piece of firewood served his roora in days gone by. The picture has changed so rapidly that steps had to be taken to reduce roora charges. To appreciate the seriousness of roora today we need to follow the whole procedure from the time of engagement to the time a new home is established.

A young man can no longer approach the parents of his fiancée directly. A middleman has to be employed and he may be paid a few dollars for his service. However before a young man can officially declared his desire to marry, he has to ask permission to show his fiancée his parent’s home. On her return, the girl is expected to give a detailed account of the wealth and nature of the boy’s family. Her family want to know the number of cattle they own and if there are few, they will discourage the intended marriage. If however, the report is good and the girl is satisfied, she tells her fiancée to pay roora as soon as possible.

The young man will notify his father, usually through an uncle. If the girl’s parents are known to charge exorbitantly roora the family of the young man may grumble to show their disapproval, but in the end they usually consent. The father of the boy finds a man to act as mediator (munyai) between the two families. He is sent with the sum of about $30 to ask for permission to marry (kukumbira) When the munyai arrives he is not allowed to sit on a chair or stool but sit cross-legged on the floor and clap his hands when greeted by any member of the girl’s family. At this time, absolute respect is shown to the family. When the munyai comes on following occasions he may be allowed to sit on a chair, but he will have to clap his hands to show respect.

Most of the money he has brought he puts into a plate. The parents of the girl give him this plate when they have been informed that some young man somewhere is interested in their daughter. The girl is asked to take any amount she wants from the plate. She will use this money to buy clothes for herself and her grandmother. The remainder is taken back by the munyai. The munyai will also be asked to pay a dollar or two for the father to open his mouth. This is called vhuramuromo. The father who speaks is not the real father of the girl, but the younger brother of the father, or in his absence, the elder brother. He proceeds to enumerate what must be paid for roora. The munyai may interrupt to ask for reductions if the charges seem excessive.

Roora usually consists of cattle, rusambo, and clothing. About eight head of cattle is asked. This includes a cow or heifer for the bride's mother. This is an essential part of the roora and no one may tamper with it. It is believed that disaster will follow if anyone mistreats this cow.

Then follows rusambo. This is usually about $50, paid in cash. In addition, the father of the girl may ask for an overcoat, shoes and a hat and the girl’s mother may ask for a dress, shoes and utensils. These things are referred to as majasi.

The munyai carries this news to the young man's family so that they may prepare and send these things. When this is done, both families brew beer and prepare feasts. They invite the members of the other family to come and see the home from which the partner of their child comes.

The young wife remains at her in-law’s home until her days’ of pregnancy are advanced when her husband takes her to her home. He also brings an ox or a cow which he will slaughter to show that the girl was unspoiled by other men. He roast the meat and leaves it for the wife’s parents. He is not allowed to eat any of it without being liable for a fine. When the work is completed, the husband leaves the pregnant wife with her parents until after she has given birth to her first child.

The consummation of roora occurs only after the child, the young mother and her elder brother return to the home of the child’s father. Beer is the main dish at the feast which lasts all day.

This process of paying roora is accepted today, but some parents take advantage of it and demand suits for the father, expensive clothes for the mother and compensation for what has been spent on clothing and educating the daughter. These are some of the reasons roora has become a topic for heated debates.

The high amount of roora is in some cases the reason for elopements. A man does not like to lose the girl he loves because he cannot meet the demands of roora. In other cases, he may be told to wait until he has found a certain amount. Fearing that his fiancée may be attracted elsewhere, he resorts to eloping.

The couple made penniless through exorbitant roora charges have a poor start in life. The wife may not see that it was her parents who made them poor. When a man marries and is asked to pay for a human being a price he is never paid for anything else, he may forget that he is married a partner; rather he may think he is bought a slave. Some men tell their wives that they bought them and therefore they should be submissive and obedient.

The poor woman tempted to break her marriage may not do so for two reasons. Firstly, her parents may have spent their roora and be unable to return it to the son-in-law. Secondly, the parents may refuse their daughter entrance into their home telling her that it was her wrong choice and that she has to suffer the consequences. If there were no roora they may perhaps accept her back readily.

Many young people feel that roora has now taken a turn for the worse. But the old men are of another opinion. They maintain that roora should persist. They still remember why it was established and they are aware of the gains made from roora. Today roora may fail to fulfil the very task for which it was created because some fathers just want a lot of money. The reign of noble roora has come to an end and time will show if it will continue to be a safeguard in Shona society.

Reference

Clive and Peggy Kileff (Editors) E. Lee (illustrations) Shona Customs. Mambo Press in association with the Rhodesia Literature Bureau, Gwelo, 1974