Home >

Mashonaland Central >

Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century?

Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century?

Introduction

A number of historical articles on the Portuguese in Mozambique have been written in both Rhodesiana and Heritage of Zimbabwe – these are listed under references and this website has previously also written articles on this subject.

This article attempts to answer the question of how and why Portugal came to the Swahili coast in the late fifteenth Century.

Portugal’s historic connection with Asia

In the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries Portugal was at the forefront of European overseas seafaring exploration. Their expansion into the Atlantic began with the discovery of the Canary Islands in 1341 off the west coast of Africa.[i] As early as 1317, King Denis of Portugal made an agreement with the Genoese merchant sailor Manuel Pessanha, laying the basis for the Portuguese Navy and the establishment of a powerful Genoese merchant community in Portugal.

Under Prince Henry the Navigator (1394 – 1460) a number of programmes to encourage systematic exploration were undertaken at his orders including:

(1) established a maritime academy at Sagres, on the edge of the Atlantic

(2) encouraged local ship-builders to design boats suitable for open-sea sailing

(3) sent missions south into the Atlantic to probe the African coast

In 1415, the city of Ceuta, opposite Gibraltar on the North African coast, was occupied by the Portuguese in an effort to control navigation of the African coast. Henry, aware of profit possibilities in the Saharan trade routes, invested in sponsoring voyages that, within two decades of exploration, allowed Portuguese ships to bypass the Sahara.

In 1419, two of Henry’s captains, João Gonçalves Zarco and Tristão Vaz Teixeira, were driven by a storm to Madeira, an uninhabited island off the coast of Africa, returning the following year to establish a permanent Portuguese settlement on the islands.

Diogo Silves reached the Azores island of Santa Maria in 1427, and in the following years, Portuguese discovered and settled the rest of the Azores.[ii]

By the time Henry had died in 1460 Portuguese sea-faring mariners had reached Sierra Leone on the West African coast and were trading in gold, slaves, pepper and ivory.

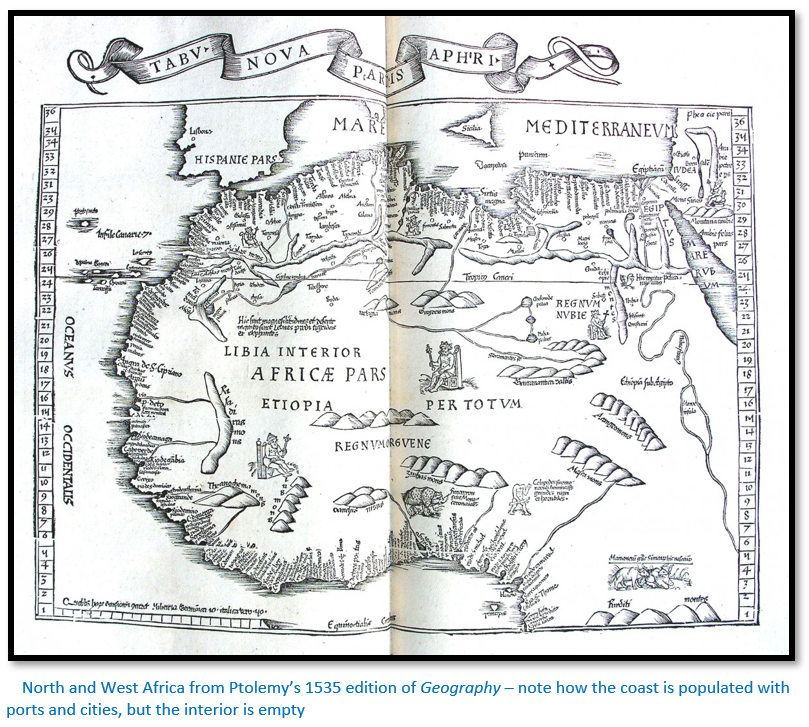

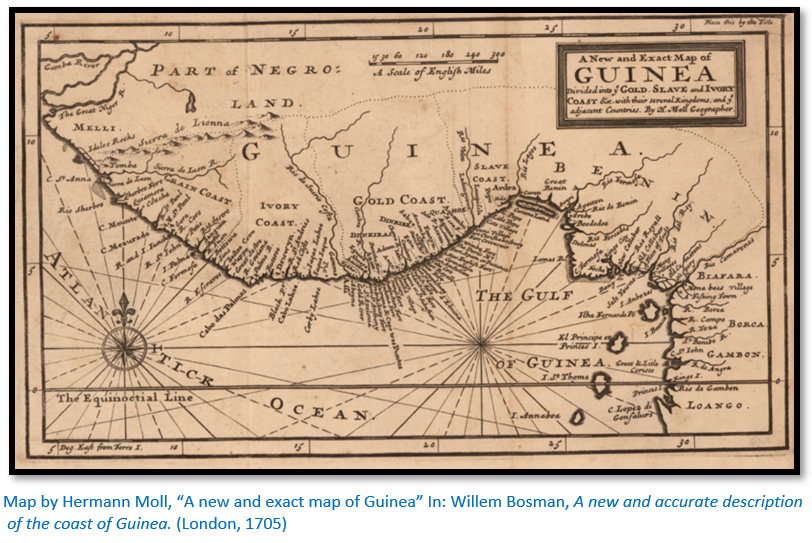

Maps by Ptolemy and Moll’s much later map of 1705 show how well the north and west coasts of Africa had been mapped from the sea. The names of towns are crammed in all along the edge of the coast, but the interior of Africa is almost blank showing how little was known about the interior of the African continent which were decorated with wild animals, mythical kings, and cyclopes.

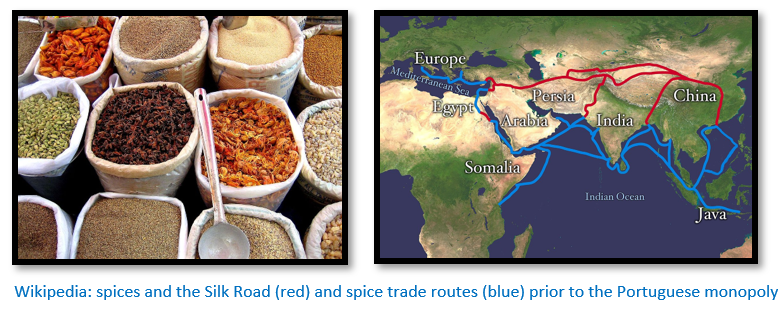

Until the mid-15th century, spices and other luxuries such as the silk trade with the East was achieved through the Silk Road, with the Byzantine Empire and the Italian city states of Venice and Genoa acting as middlemen. Each trader who handled the goods put the price up a bit in order to take their cut and by the time they arrived in Europe they were prohibitively expensive

Marco Polo, born in Venice about 1254 was one of those traders. He travelled east to China along the trade routes to visit the court of Kublai Khan, Emperor of the Mongols, who had conquered China. He stayed in China for seventeen years, serving the Khan and when returning to Italy, he was captured whilst fighting in a war. He told his adventures to another prisoner who wrote them down. His tales of riches in the Orient inspired Europeans like Vasca da Gama and Christopher Columbus to look for a direct sea route with Asia which would reduce the hazards of travelling by land across many countries.

Portugal’s motivation came in 1453 after the fall of Constantinople when the Ottoman Empire took control of the spice trade and levied additional hefty taxes on merchandise bound for the west. Portugal not wanting to be dependent on an expansionist, non-Christian power for the lucrative commerce with the East, set out to find an alternative route by sea around Africa.

Portugal’s ultimate aim was to find a sea route to the riches of India

The Portuguese went on exploring the African coast. The discoveries of Bartolomeu Dias and Vasco da Gama took them round the tip of Africa and into the Indian Ocean.

In 1481 Diogo de Azambuia led an expedition to construct a fortress and trading post called São Jorge da Mina in the Gulf of Guinea. He was probably accompanied by Bartolomeu Dias who may have also participated in Diogo Cão's first expedition (1482-1484) down the African coast to the Congo river.

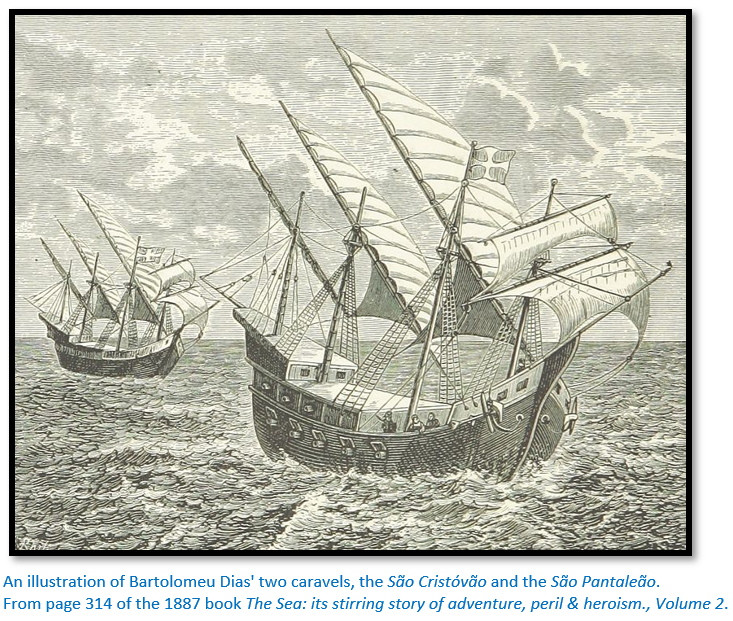

King John II remained determined to continue the effort and in October 1486 he commissioned Dias to lead an expedition in search of a trade route around the southern tip of Africa. Dias was provided with two caravels of about 50 tons each and a square-rigged supply ship captained by his brother Diogo and recruited some of the leading pilots of the day, including Pêro de Alenquer and João de Santiago, who had previously sailed with Cão.

Bartolomeu Dias rounds the Cape of Good Hope

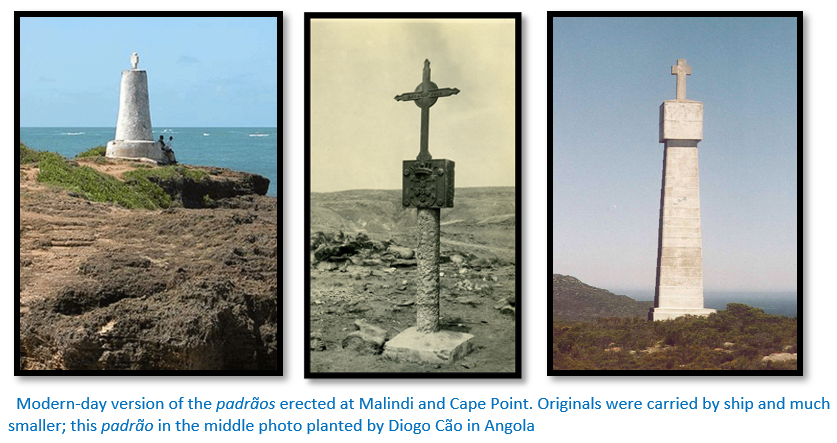

The three ships left Lisbon in July 1487. Like his predecessor, Cão, Dias carried a set of padrãos, carved stone pillars to be used to mark his progress at important landfalls. Also onboard were six Africans who had been kidnapped by Cão and taught Portuguese. They were to be dropped off at points along the African coast so they could testify to the grandeur of the Portuguese kingdom and make inquiries into the possible whereabouts of the Kingdom of Prester John.[iii]

After making slow progress along the Namibian coast, the two ships turned southwest away from land to find more favourable winds and their course traced a broad arc around the tip of Africa and on 4 February 1488, after 30 days on the open ocean, they entered what would eventually become known as Mossel Bay…they had rounded the southern tip of Africa and what Dias named the “Cape of Storms” (Cabo das Tormentas) It was later renamed as "Cape of Good Hope" (Cabo da Boa Esperança) by John II of Portugal who was optimistic about the commercial prospects of a sea route to India and the East.

The ships continued to the northeast reaching their furthest point on 12 March 1488, when they anchored at kwaaihoek, near the mouth of the Boesmans river and here Bartolomeu Dias erected the Padrão de São Gregório, his first padrãos, or stone cross on 12 March 1488.[iv] By then, the crew had become increasingly restive and urged Dias to turn around. Supplies were low, the ships were storm-battered, and the officers wanted to return to Portugal. Although Dias wished to continue, he agreed to turn back and it was on the return voyage that they actually saw the Cape of Good Hope, in May 1488.

Portugal’s exploration continues to find a sea route to Asia

Following the return of Dias, the Portuguese took a decade-long break from Indian Ocean exploration. Only in 1497 was another voyage commissioned by Manuel I and Dias helped in the design and construction of the São Gabriel the flagship and its sister ships the São Rafael, the Bérrio, and the supply ship São Miguel which were used by Vasco da Gama to sail around the Cape of Good Hope and then onto India.

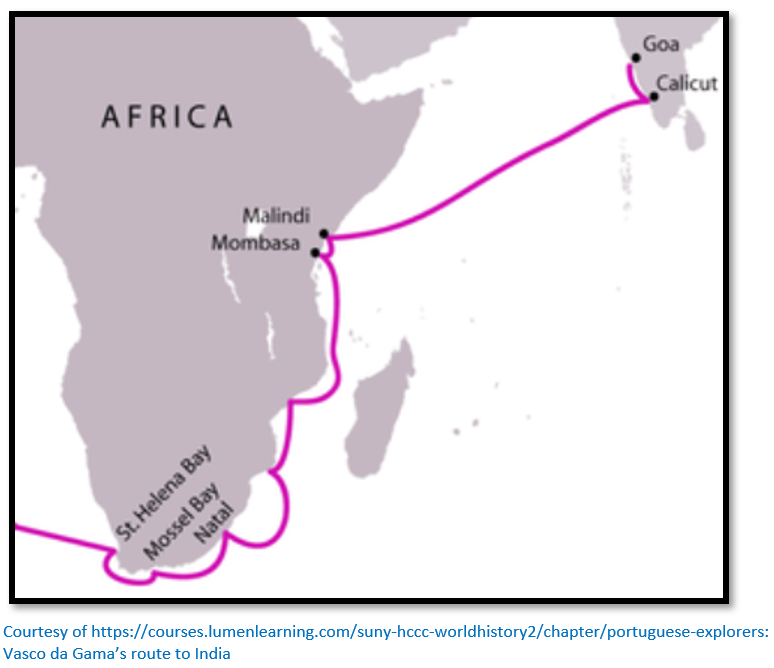

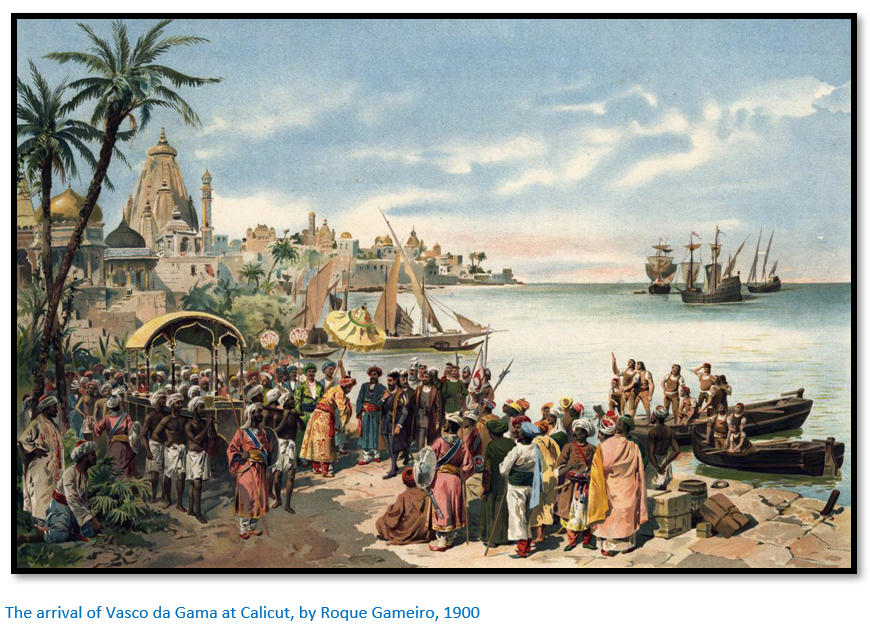

The Portuguese goal of finding a sea route to Asia was finally achieved by Vasco da Gama, who reached Calicut in Western India in 1498, becoming the first European to reach India. Dias himself only sailed as far as the Cape Verde Islands.

The second voyage to India was dispatched in 1500 under Pedro Álvares Cabral with Dias as one of the captains. In following the winds to the south-west, they became the first Europeans to reach Brazil on 22 April 1500, before continuing east across the South Atlantic Ocean. Dias perished near the Cape of Good Hope that he had presciently named Cape of Storms. Four ships, including Dias's, encountered a huge storm off the Cape of Good Hope and he drowned on 29 May 1500.[v] The remaining ships sailed up the East African coast to pick up a local Swahili pilot[vi] at Malindi before crossing the Indian Ocean and reaching Calicut.

What was the purpose of Portugal’s exploration?

This was to gain a monopoly of the spice trade in the Indian Ocean. Taking advantage of the rivalries between Hindus against Muslims, the Portuguese established forts and trading posts between 1500 and 1510 including at Goa, Ormuz, Malacca, Kochi, the Maluku Islands, Macau and Nagasaki. Guarding its trade from both European and Asian competitors, Portugal dominated not only the trade between Asia and Europe, but also much of the trade between different regions of Asia, such as India, Indonesia, China and Japan.

Over time Portuguese mariners pushed further east. In 1511, Albuquerque sailed to Malacca in Malaysia, the most important eastern point in the trade network and Malacca became the strategic base for Portuguese trade expansion with China and Southeast Asia. They also dominated much of the southern Persian Gulf for the next hundred years.

However, the further expansion of Portugal’s trading empire is not the purpose of this article which concentrates on Mozambique, although the above provides the historical background.

The spices that were considered so desirable included cinnamon, cassia, cardamom, ginger, black pepper, cloves, nutmeg and turmeric.

The Swahili coast

The narrow strip of land that stretches along the eastern edge of Africa from Somalia in the north to Mozambique in the south is described as the Swahili coast. Even today, Swahili is the lingua franca of East Africa.

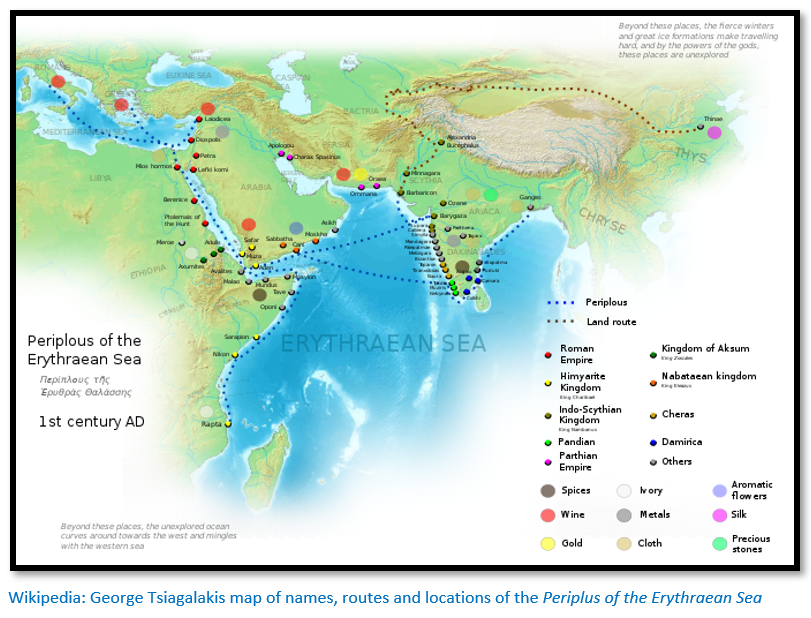

From earliest times dhows have used the seasonally alternating Indian Ocean monsoon winds for sea voyages up and down the coast. One of the first written records of the Swahili coast was a Greek merchant’s guide from the first century describing sailing voyages on the Red Sea and the coast of East Africa called the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. It describes the wealth of ivory, rhino horn, tortoise shell, and palm oil that was traded in each of these East African city-states.

The original inhabitants of the Swahili coast were Bantu-speaking Africans, who moved from the interior of Africa and spread up and down the coast, trading with each other and the people of the interior and eventually people from outside Africa.

Commercial trade started in the eighth century when Arab Muslim traders came and settled on the coast and were followed in the twelfth century by Persians —known as the Shirazi.

On Rhapta, the southernmost named African port, the Periplus informs us that: “Two runs beyond this island [Menuthias = Zanzibar?] comes the very last port of trade on the coast of Azania, called Rhapta ["sewn"], a name derived from the aforementioned sewn boats, where there are great quantities of ivory and tortoise shell.” [vii]

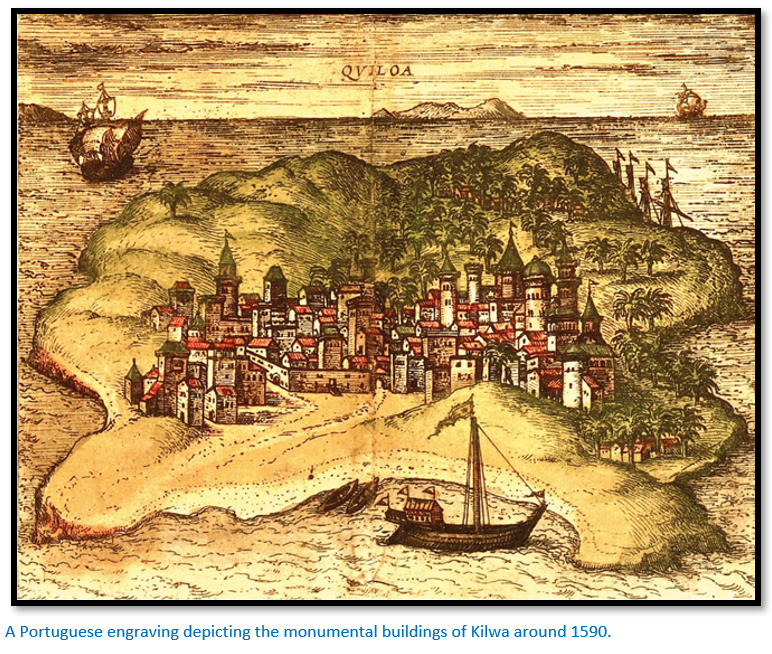

Kilwa on the Swahili coast reached its highpoint in the eleventh to fifteenth centuries

The Swahili coast comprised a number of city-states that traded across the Indian Ocean. The city-states were independent sultanates, although they shared a common language (Swahili) and religion (Islam) They traded across the Indian Ocean for items such as pottery, silks and glassware.[viii]

The major city-state and trading centre in the southern section of the Swahili coast and a major archaeological site today, is Kilwa, located on an island off the southern coast of Tanzania. Its ruins today include a large stone mosque and the Great Palace, which was at the time the largest stone building in Africa south of the Sahara Desert. The grounds of the Great Palace (Husuni Kubwa) occupied a large area and included a swimming pool and around a hundred rooms. The Portuguese added a prison-fort.

The well-known Moroccan traveller Ibn Battuta visited Kilwa and refers to this important town in 1331, as did the Portuguese chronicler João de Barros, who described Kilwa in his work, Décadas da Ásia ("Decades of Asia") the ‘‘Kilwa chronicle’’, a vernacular Swahili document about the history of the town (de Barros 1552)

The Portuguese chronicler Gaspar Correia in the early sixteenth century described Kilwa as a large city encircled by walls: “Within these there are perhaps 12,000 inhabitants. The country all round is very luxurious with many trees and gardens of all sorts of vegetables, citrons, lemons, and the best sweet oranges that were ever seen.”

The palace and a great mosque, built partly of coral stone, were built from the wealth of the gold trade of East Africa that flowed through this tiny island. Kilwa’s merchants kept a trading outpost at Sofala to the south and in present-day Mozambique which traded for gold from present-day Zimbabwe within the interior.

Portugal uses force to subdue Muslim opposition

Kilwa and other important East African towns were conquered in the beginning of the sixteenth century by the Portuguese, together with many other Indian Ocean towns including Ormuz at the entrance of the Persian Gulf and Malacca between the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Portuguese ships and cannon quickly overcame any opposition in the Indian Ocean. Portuguese traders settled along the East African coast in scattered trade settlements and relied on the main towns like Sofala, Mozambique Island, Mombasa, Malindi and others, where the Portuguese had established fortresses, to protect them.

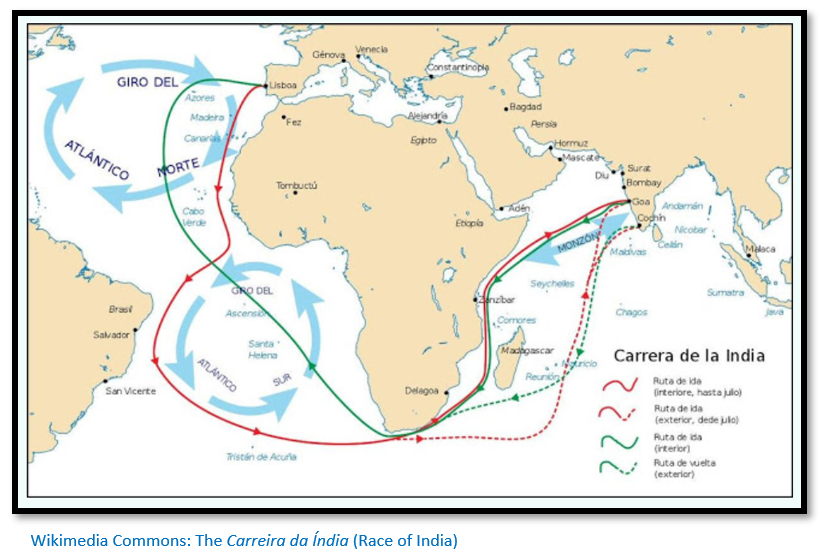

Carreira da Índia (Race of India)

Portugal’s Carreira da Índia (Race of India) linked Lisbon with the Indian ports of Goa, Cochin and Malacca both for the outward and return journey (red and green respectively on the map below) The journey consisted of circumnavigating Africa taking advantage of the Atlantic currents to round the Cape of Good Hope and then those of the Indian Ocean. Here there were two options, the inland one discovered by Pedro Álvares Cabral, parallel to the eastern coast of Africa, or the outer coast, in the open sea, depending on the season of the year, using the monsoon winds.[ix]

The southwest monsoon off the west coast of India, commenced around the beginning of June and virtually closed all harbours in this region from the end of May to the beginning of September. On the other hand, the trading season in India lasted from September to April.

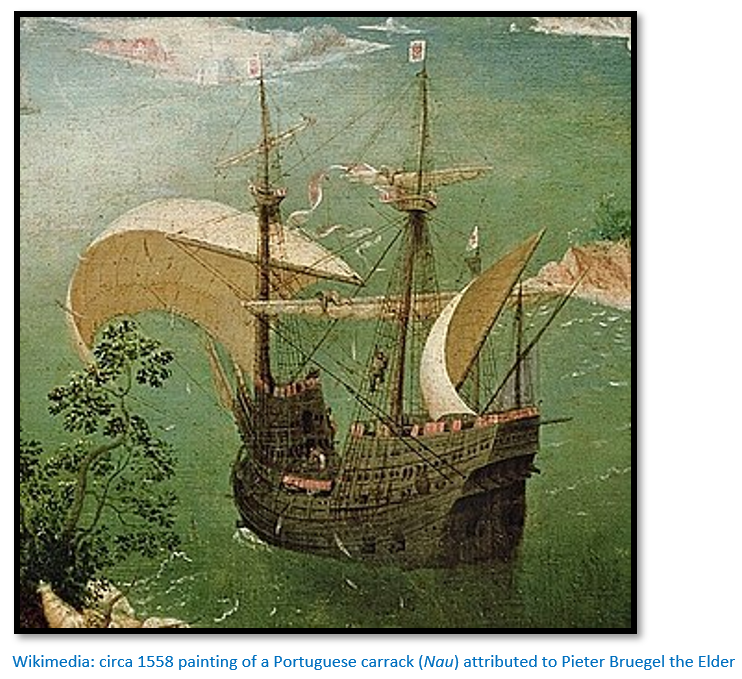

Each leg of the voyage took approximately six months.[x] The Portuguese carracks (Portuguese: Nau) and galleons ships aimed to leave Lisbon before April so as to round the Cape of Good Hope in time to reach the tailwind of the southwest monsoon off the East African coast, north of the equator, which would bring them to Goa in September or October during the trading season. Similarly, they aimed to depart Goa with the northeast monsoon around December to March in order to round the Cape of Good Hope prior to the onset of the May winter season.[xi]

The seasonal monsoon winds blow as far south as 24° south, roughly the vicinity of Inhambane bringing not only rain but linking the ports of the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, India and the Persian Gulf. Between October and March trading dhows would visit the Swahili coast trading for gold, but also exotic skins, turtle shell, ivory, mangrove poles and slaves.[xii]

The Estado da India claims the Indian Ocean for Portugal

The origins of the Estado da India which encompassed all Portuguese Crown possessions east of the Cape of Good Hope can be traced back to the inaugural voyage of Vasco da Gama from Lisbon to Calicut in 1497–1498. After some delay, the Portuguese Crown created a governorship for India in 1505, with its seat at Cochin, later transferred to Goa, to oversee all their commercial, military, administrative, and other possessions along the shores of East Africa and Maritime Asia. Portuguese trading posts (feiras) forts and fortified towns across the region resulted from conquest or more frequently, from negotiated agreements with local rulers, on whose cooperation the Portuguese generally relied.[xiii]

Malyn Newitt writes that Estado da India was: “a wholly new concept in international law and practice as the Portuguese declared the sea, rather than any land, to be the sovereign realm of the Portuguese Crown. It was to be defended by a series of strategically sited bases which would be garrisoned and where ships could be repaired and provisioned. Ships belonging to all merchants crossing the ocean would have to seek the permission of the Portuguese and pay duties on their merchandise. To overcome their uncompetitive position in eastern markets the Portuguese Crown decided to declare the trade in certain commodities to be Crown monopolies and they attempted to enforce these monopolies by a system of cartazes or passes which merchants would have to acquire to trade in the King of Portugal's dominions.”[xiv]

The Portuguese Indian Armadas (Armadas da Índia) and their voyages

These were the fleets of ships, organized by the crown of the Kingdom of Portugal and dispatched on an annual basis from Portugal to India, principally to Portuguese Goa and Malacca. Between 1497 and 1650, there were 1,033 ship departures at Lisbon for the Carreira da Índia ("India Run")[xv]

The critical stage was ensuring the armada reached East Africa on time as ships that failed to reach Mozambique Island on the East African coast by late August might be stuck until next Spring for the monsoon winds to make the Indian Ocean crossing. Then they would have to wait in India until the Winter to begin their return…any delay could end up adding an entire extra year to a ship's journey.

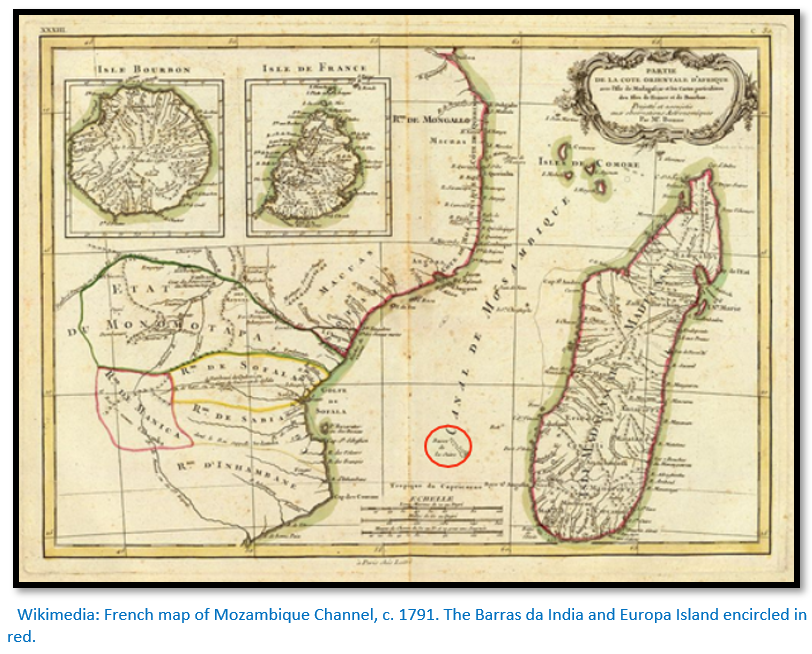

However, for some, the Island of Madagascar opened an alternative route to get to India which gave more flexibility. If an outbound armada passed the Cape of Good Hope before mid-July, then it would follow the old "inner route" – that is, sail into the Mozambique Channel, up the East African coast as far as Malindi and take the south westerly monsoon across the ocean to India. If, however, the armada was late, then it was obliged to sail the "outer route" by sailing east from South Africa, then under the southern tip of Madagascar, before turning north through the Mascarenes islands and across the open ocean to India. The outer route meant skipping the resupply at Mozambique Island, but avoided sailing directly against the post-summer monsoon.[xvi]

The key worry of the return fleets was the fast dangerous waters of the inner Mozambican channel, particularly precarious for heavily loaded and less manoeuvrable ships. Initially the return fleet usually set out from Cochin in December or, 20 January latest; after which all return fleets were obliged to follow the “outer route” which was thought calmer and safer for their precious cargo. But missing Mozambique Island on the return leg meant they had to stop at Mossel Bay or St. Helena for water supplies.

By 1525 all return fleets were ordered to follow the outer route, although this rule was suspended between the 1570’s and 1590’s. From 1615, a new rule was introduced whereby return fleets from Goa were allowed to use the “inner route” but return fleets from Cochin still had to use the “outer route.”

For those interested, Wikipedia lists the Indian Armadas in great detail from 1497 to 1511.[xvii]

The increasing commercial importance of the Swahili coast to Portugal

The coastline of present-day Mozambique became increasingly important for two main reasons:[xviii]

- The Portuguese carracks and galleons that managed to get around the Cape of Good Hope and the treacherous coastline needed a port of call where they could resupply and carry out repairs, land the sick and take on fresh crew after the long sea voyage around West Africa and the South Atlantic Ocean. Mozambique Island, two kilometres offshore and protested by a large and deep anchorage was perfect for the Estado da India to ‘winter’ as their ships were refitted and resupplied.

- Gold was being mined in the hinterland of Sofala and had been traded at the Manica gold market for centuries by Swahili merchants using river-going dhows on the Buzi river (Rio de Sofala in older maps) as access into the interior. The revenues from Sofala's gold trade enabled the Kilwa sultans to expand the Swahili empire all along the East African coast. Portugal needed gold as it provided them with the means to purchase spices in India and Asia. In 1502 Portuguese chronicler Thomé Lopes [xix] identified Sofala as the biblical Ophir and its ancient rulers with the dynasty of the Queen of Sheba. Sofala soon became the centre of Portuguese gold trading and the site of a permanent garrison settlement.

Sailing from the Cape of Good Hope to Mozambique Island

The Cape of Good Hope was one of the most challenging sections on the India Run and many ships were lost. Larger armadas often broke up into smaller squadrons to round the Cape and would re-collect far up the present-day South African coast as they avoided the waters of the contrary Agulhas Current.

Mossel Bay (Agoada de São Brás) was the first watering stop after the Cape, but not always used on the outbound journey as individual ships often charted wide routes around the Cape and sighted the coast again only well after this point. But ships damaged in storms would have to put in for emergency repairs and would trade with local Khoikhoi people that lived in the area for food, although there were also occasional skirmishes. Ships going on the return journey often stopped at Mossel Bay and in early years it was used as a postal station, with messages from the returning armadas for the outward armadas reporting on the latest conditions in India.

By the “inner route” the next obstacle was Cape Correntes at the entrance of the Mozambique Channel with dangerously fast waters, light winds alternating with unpredictably violent gusts and dangerous shoals and rocks. Of all the ships lost on the India run, nearly 30% of them capsized or ran aground around here - more than any other place.[xx]

The ideal passage through the Mozambique Channel was to sail straight north through the middle of the channel, but a difficult task in days of crude navigation instruments. A course too close to the African coast meant a fast counter-current running south and light or non-existent winds and shallow sandbars, the shoals at Cape Correntes having special terrors.

The alternative was to sail east until the island of Madagascar was sighted, then move up the channel as the current here ran north, keeping the coast in sight at all times. The disadvantage was the coral islets, atolls, shoals, protruding rocks and submerged reefs which were particularly hazardous at night or in bad weather.

To avoid either of the last two obstacles the navigators favoured a middle route through the channel between Mozambique and Madagascar using the Bassas da India and the Europa rocks as navigation markers. Although conveniently situated in the middle of the channel, they were not always visible above the waves, so sailors often watched for hovering clusters of seabirds, which colonized these rocks, as an indicator of their location. Unfortunately, this was not a reliable method, and many an India ship ended up crashing on those rocks.

In 1585, 50 survivors from the Portuguese Nau, S. Tiago, which was wrecked at Bassas da India, managed to reach the East African coast after an incredible trip of more than 450 kms in a small batel from the ship. They came ashore near the mouth of the Zambezi river where they met a well-established local Portuguese trader, Francisco Brochado, who gave them assistance. They then sailed in a luzio, a now extinct traditional boat, to get to Mozambique Island, more than 600 kms north of the Zambezi.[xxii]

The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library has an account of the 1585 shipwreck published by Gomes de Brito: “By August 19th, Santiago continued north, approaching the shoals of Bassas da India. On this day the pilot measured the sun and calculated that the shoals approximately seven to eight leagues (38 to 44 kms) to the north. That night the crew assumed they had already passed the shoals during the day when in fact, they were upon the shoals. Santiago struck three times and the bottom of the ship mounted the reefs. Two of the decks were instantly shattered to pieces, while another two decks were thrown, together with the masts and sails, onto the top of the shoals, with the mainmast breaking at the base upon impact. Santiago wrecked with more than 375 people on board…”[xxiii]

If they succeeded sailing up the middle channel, the Portuguese carracks usually saw the African coast again only around the bend of Angoche. If the ships needed urgent repairs they stopped at the Primeiras Islands (off Angoche) which are a long row of uninhabited low coral islets – not much more than mounds above the waves – but they form a channel of calm waters between themselves and the mainland, a useful shelter for troubled ships.

The usual first stop for the Indian Armadas was Mozambique Island with its town and fortress and opportunity to re-supply. With the last previous stop at Cape Verde ships often reached here in poor condition. Food was stale, scurvy and dysentery had often caused the deaths of crews and passengers and the ships themselves badly needed re-caulking and re-painting.

Principal ports and cities of the Swahili coast of East Africa, c. 1500

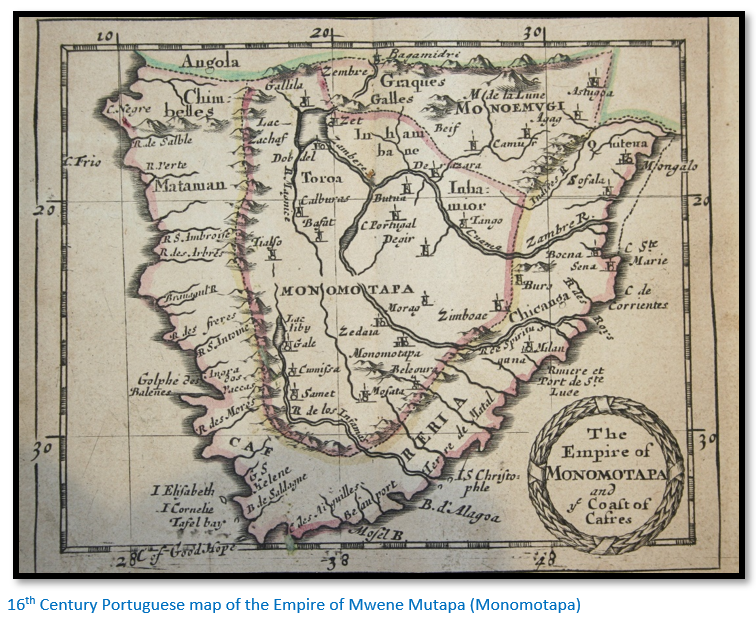

Sofala was the original destination to Portugal, a small Swahili trading settlement and the main outlet of the gold trade of Mwene Mutapa (Monomotapa) Fort São Caetano de Sofala was built in 1505, the first Portuguese fortress on the Swahili coast. But Sofala's harbour was hampered by a long moving sandbank and hazardous shoals, making it quite unsuitable as a stop for the India armadas.

There is more detail on Sofala in the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Mozambique Island was originally an outpost of the Kilwa Sultanate, whose decline was accelerated by the arrival of the Portuguese. In 1507, the 9th Portuguese India Armada seized Mozambique Island and erected a fortress there (Fort São Gabriel, later replaced by Fort of São Sebastião in 1558) and used its spacious and well-sheltered harbour.

The main drawback of Mozambique Island was that it was parched, and infertile, even drinkable water had to be ferried by boat. There were water holes, gardens and coconut palm groves for timber on the mainland at Cabaceira inlet, but the Bantu inhabitants of the region were generally hostile to both the Swahili and the Portuguese, often making the collection of supplies difficult.

The Portuguese ship’s factors in Mozambique had to ship in supplies by dhow from other sites on the East African coast to Mozambique Island before each India Armada's scheduled arrival along with African goods that could be taken onboard and sold in Indian markets – notably gold, ivory, copper, pearls and coral.

Sailing conditions were not always perfect, even at Mozambique Island. In 1698, before proceeding to Mombasa, Santo Antonio de Tanna was trapped here by a hurricane, causing extensive damage to the ship including the breakup of the main mast. Strong hurricanes, locally called monomocaias, are a frequent cyclical occurrence along the coast of Mozambique and can cause severe damage to vessels.

Portugal’s relations with local Swahili communities quickly deteriorated

Sofala provides a typical example. The Swahili had been well-established at Sofala for a long time, although when the Portuguese arrived Sheikh Isuf of Sofala was refusing to recognise the current ruler at Kilwa. The minister Emir Ibrahim had murdered the legitimate sultan al-Fudail of Kilwa and seized power for himself. To the Sheik the Portuguese, with their powerful ships, seemed to provide a strong ally to help him shake off Kilwa’s illegitimate claims and he agreed to a commercial and alliance treaty with the Kingdom of Portugal.

In 1505 Pêro de Anaia (part of the 7th Armada) was granted permission by Sheikh Isuf to erect a factory and fortress near his village. Initially the Portuguese tried to work through the local ruler but their attempts to force local Swahili merchants to give them a monopoly on the gold trade soon created considerable tensions. In the end the Swahili merchants found new trade routes into the interior and over the centuries the Portuguese raised local families and began to adapt to the trading patterns which were already established.

Even on Mozambique Island the Portuguese and Muslim communities found it difficult to live together and the Sheik removed himself and most of the local population to the mainland. However, a system of co-existence was established with local Muslim networks working with Portuguese agents who often married local women and had families. In this way the ivory trade developed and also necessities such as food, pottery, timber and household items were purchased in local communities and then moved along the coast by dhow to Mozambique Island and Sofala.

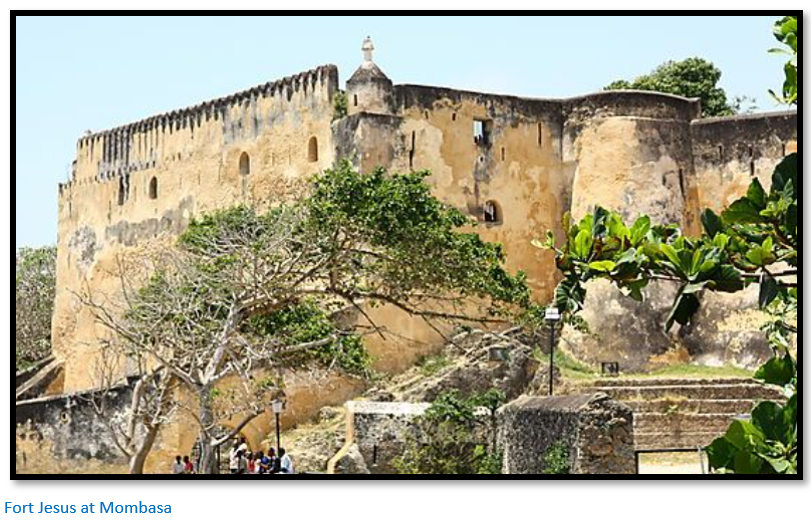

All the other Swahili cities up the coast, with the exception of Malindi, refused to accept any commercial relations with Portugal. The Portuguese came to believe they were actively undermining their efforts which led to raids and fighting. Angoche was raided in 1513, Querimba and Mombasa attacked in 1522 and 1524.[xxiv] In the 1580’s the arrival of Turkish galley’s led to a revolt by local Muslim people against Portugal’s rule which the Portuguese tried to counter by building the fortress of Fort Jesus (Forte Jesus de Mombaça) located on Mombasa Island between 1593 – 1596.

The Dutch in 1607 and 1608 made determined efforts to capture Mozambique Island. However, the Portuguese withstood the sieges, and the Dutch made no further challenges to Portugal on the Swahili coast.

In 1631 the Sultan expelled the Portuguese from Mombasa and the whole of the northern coast rose against them. The Omani’s led a series of revolts against Portuguese rule, raiding Mozambique Island in 1670 and in 1697 Omani Arabs sieged the Portuguese Fort Jesus at Mombasa. A fleet consisting of two frigates and two galliots, under the command of General Luis de Mello Sampaio was sent to relieve the garrison, but failed and the fort fell in 1698, resulting also in the loss of one of the frigates, Santo Antonio de Tanna, which was wrecked and sank in Mombasa harbour. Portugal’s rule on the northern coast had come to an end.

Newitt explains that Indian merchants were much more successful at integrating themselves into local Muslim communities. By the end of the seventeenth century, they were to be found in all the trading towns and markets both on the coast and in the interior. In the early eighteenth Century it was Indian merchants, not Portuguese who were commercially active and established settlements at Zumbo[xxv] on the Zambesi river and Inhambane on the coast.[xxvi]

The administrative organisation in Mozambique undergoes changes

Initially in the sixteenth century the northern region was governed by the Captain of the Coast at Malindi with the southern region under the Captain of Mozambique and Sofala. However, as Muslim opposition mounted the northern region became virtually redundant and in the south the administrative centre moved from Sofala to Mozambique Island in the 1550’s.

At first fortress captains were salaried royal officials in charge of the garrisons and ships, with factors appointed to administer the crown monopolies over ivory and gold. But by the seventeenth century the captaincy would be granted to a loyal royal servant who paid a large amount (40,000 cruzados) for the privilege. Maintenance of the forts and garrisons was then his responsibility, he appointed the captains at Sena and Tete and he personally held the royal monopolies to import cloth for sale and to buy ivory and gold from the interior.[xxvii]

Newitt believes the captain’s monopoly may have forced Swahili merchants to look for new trade routes away from their former settlements and to coastal regions not dominated by the Portuguese. However, the captain’s did not impede trade into the interior, and he believed that interference in the internal affairs of Mwene Mutapa (Monomotapa) was more often directed by Dominican missionaries.

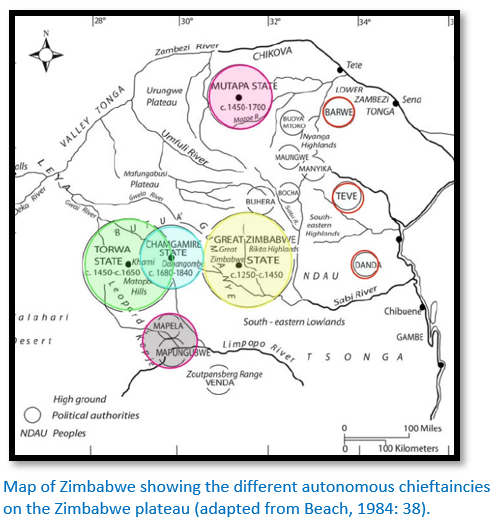

The Portuguese and the Monomotapa Empire

This article will deal briefly with the region south of the Zambezi river from the Sabi river to the northern plateau of present-day Mashonaland and parts of the Zambesi valley known as Chedima and Dande, now mostly in present-day Mozambique, because of its importance for the gold trade. In the fifteenth century a number of Karanga states dominated this region who recognised the overall authority of the Mwene Mutapa (Monomotapa)

The confederacy of Karanga states included:

Dande and Mukaranga (northern plateau of Mashonaland)

Barwe or Barue (lower Zambesi Valley and present-day Zimbabwe border)

Manyika (present-day border of Zimbabwe / Mozambique)

Uteve (inland of Sofala)

Butua or Butwa (southwest Zimbabwe around present-day Bulawayo)

The main attraction to the Portuguese were the gold fairs which had initially attracted Swahili merchants from the coast and the Portuguese through Sofala and later from the settlements on the Zambesi river at Sena and Tete. Cotton textiles, beads, metalware, porcelain and firearms were traded for gold.

Gold was obtained in the dry season by panning for alluvial gold from the rivers and mining for reef gold. The Portuguese came to believe there were large mines in the region which could be exploited and mined directly by themselves. This led to Francisco Barreto’s attempt to capture the mines between 1569 – 1575, although the expedition was dressed up as seeking revenge for the murder of the priest Goncalo da Silveira by the young Monomotapa Chisamharu Nagomo - plotted by the Swahili merchants on upper Musengezi river who feared that once converted to Christianity the ruler would favour the Portuguese traders and expel or reduce the number of Muslims permitted in his territory. [See the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Gradually the Portuguese integrated themselves establishing a permanent presence at some of the gold fairs (Luanze, Dambarare, Maramuca) and sending in trading caravans under trusted servants and family members to the other gold fairs. [See the articles Luanze Earthworks and Church under Mashonaland East and Maramuca, a Portuguese Feira dating from 1660 – 1680 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] The Mwene Mutapa ruling house was weakened by succession disputes and the Portuguese, encouraged by the Dominican missionaries, actively connived to support rival rulers and weaken the ruling elites.

At the end of the seventeenth century the existing Torwa State based around Khami was in 1683 overcome by the Rozvi and their ruler Changamire Dombo. Changamire and his son Kambgun Dombo defeated the Mwene Mutapa and drove the Portuguese off the central plateau and completely overturned the political landscape bringing the whole of present-day Zimbabwe under their control.

From the beginning of the eighteenth Century the Mwene Mutapa state was reduced to relative insignificance including only Dande and Chedima and the Portuguese retained only a nominal presence at the Manyika fair. The Rozvi economy was based on cattle herds but the gold trade continued and although individual Portuguese were not allowed into their territories they allowed them to trade at the Manyika fair and at a new fair established at Zumbo on the Luangwa / Zambesi confluence.[xxviii]

References

Malyn Newitt. A Short History of Mozambique. Hurst and Co, London

St John’s College, Cambridge. www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/library_exhibitions/schoolresources/exploratio...

Wikipedia: Portuguese Exploration. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portuguese_discoveries

M.J. Noai. 3 September 2020. National Geographic: This abandoned East African city once controlled the medieval gold trade.

27 May 2019. Carreira da Índia, the Portuguese version of Tornaviaje. https://citaclio.blogspot.com/2019/05/carreira-da-india-la-version-portu...

Z. Biederman. The Portuguese Estado da Índia (Empire in Asia) https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.01...

R.W. Dickinson. Sofala: Gateway to the Gold of Monomotapa. Rhodesiana No 19, December 1968

R.W. Dickinson. Sofala and the South East African Iron Age. Rhodesiana No 22, July 1970

R.W. Dickinson. Angoche and the Sofala Shoal. Rhodesiana No 34, March 1976

V.L. Bosazza. Muslim or Arabic navigations on the East Coast of Africa. Rhodesiana No 35, September 1976

R.W. Dickinson. The Explorations of the Portuguese and the spread of Portuguese Influence. Rhodesiana No 39, September 1978

J. Waters. A disappointing outpost of the Portuguese Empire: Sofala revisited. Heritage of Zimbabwe No 27, 2008

R.T. Duarte. Maritime History in Mozambique and East Africa: The Urgent Need for the Proper Study and Preservation of Endangered Underwater Cultural Heritage. J Mari Arch DOI 10.1007/s11457-012-9089-6

The Nautical Archaeology Digital Library. https://shiplib.org/index.php/shipwrecks/iberian-shipwrecks/portuguese-india-route/santiago-1585/

Beach DN (1984) Zimbabwe before 1900. Gweru: Mambo Press.

Notes

[iv] Wikipedia: remnants of the cross were rediscovered in 1938 by Prof. E. Axelson and transferred to the University of the Witswatersrand in Johannesburg. A replica cross has been erected on the spot.

[v] Wikipedia: tradition says that Dias originally named it the Cape of Storms (Cabo das Tormentas) and King John II later renamed it the Cape of Good Hope (Cabo da Boa Esperança) because it represented the opening of a route to the east.

[vi] Swahili, Arabs and Indians were known to be skilled sailors and a local pilot guided the Portuguese navigator Vasco da Gama from Malindi to India

[vii] Recent research by the Tanzanian archaeologist Felix A. Chami has uncovered extensive remains of Roman trade items near the mouth of the Rufiji river and the nearby Mafia Island, and makes a strong case that the ancient port of Rhapta was situated on the banks of the Rufiji River just south of Dar es Salaam. Wikipedia

[x] Wikipedia: Portuguese India Armadas

[xii] A Short History of Mozambique, P7

[xiii] The Portuguese Estado da Índia

[xiv] A Short History of Mozambique, P23

[xv] Wikipedia: Portuguese India Armadas

[xvi] Ibid

[xvii] Wikipedia: Portuguese India Armadas

[xviii] A Short History of Mozambique, P25

[xix] Thomé Lopes was a escrivão (captain's clerk) aboard an ship that was part of a Portuguese squadron of five ships under the overall command of Estêvão da Gama (a cousin of Vasco da Gama) which left Libon on 1 April 1502 intending to catch up and join the 4th Portuguese India Armada of Admiral Vasco da Gama, which had left a few months earlier in February 1502. They met up on 21 August 1502 at Angediva Island, off the Malabar Coast of India.

[xx] Guinote, P.J.A. (1999) "Ascensão e Declínio da Carreira da Índia", Vasco da Gama e a Índia, Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1999, vol. II, pp. 7–39.

[xxii] Maritime History in Mozambique and East Africa

[xxiv] A Short History of Mozambique, P26

[xxv] Known for the trade in ivory, slaves, gold, copper and malachite from present-day Zambia

[xxvi] A Short History of Mozambique, P28

[xxvii] Ibid P29-30

[xxviii] Ibid P36

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: