Home >

Mashonaland Central >

The rise of the Mutapa State and the early arrival of the Portuguese c.1450 - c.1480

The rise of the Mutapa State and the early arrival of the Portuguese c.1450 - c.1480

The first limitation in writing any article on the Mutapa state is the absence of original and contemporary sources other than those of the Portuguese whose presence began off the East African coast in the last decade of the 15th Century and who encountered the Mutapa state at the peak of its influence in the 16th – 17th Centuries. Their accounts obviously carry a Eurocentric bias; many were written by the Jesuits such as Father João dos Santos[i] and Father Francisco Monclaro[ii] religious figures who had an obvious bias against both ‘Moors’ and traditional religious beliefs. There is a vast body of Portuguese historical documents available mostly written in Portuguese and probably for this reason there are many inconsistences even in scholarly articles which include statements of supposed events which don’t quite make sense.

Fortunately, there are many professional archaeologists, anthropologists and local historians in Zimbabwe today who are carrying out solid archaeological research and filling in the gaps and these are often complimented by traditional accounts of their history recalled in the oral history of Zimbabweans. Their oral accounts often contain myths accounting for their origins and for the changes in the rulers; but they also include details of their migrations to the present and are useful sources of historical information.

Introduction

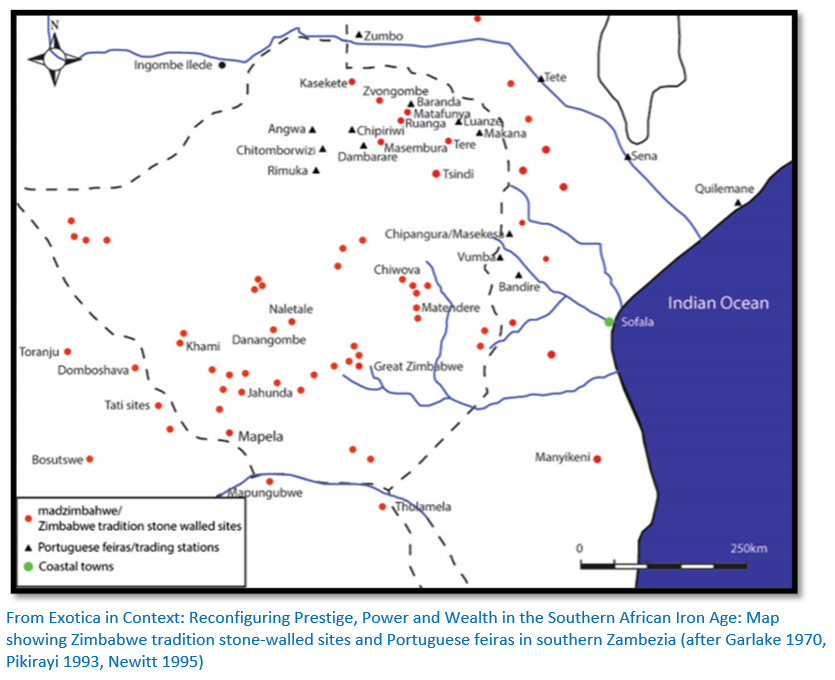

Innocent Pikirayi argues a shift in the gold trade from the southern to the northern regions of the Zimbabwe plateau, increased competition for trading resources and the need to build a local political power base resulted in Great Zimbabwe losing its dominance to competitor regions – Khami in the south-west, and Mutapa, in the north of present-day Zimbabwe.[iii]

Additional factors may include overpopulation, overgrazing of the land by large cattle herds and deforestation, leading to food shortages, which were exacerbated to crisis point by a series of droughts. This resulted in a decline with the previously lucrative coastal trade on the Swahili Coast at Sofala with the reduction in gold outputs recorded by the Portuguese factors. Possibly these factors contributed to the gradual decline of Great Zimbabwe.

Gilbert Pwiti put this traditional argument extremely succinctly: “Essentially, external trade brings in new wealth which falls under the control of a small group of people who then use it as a springboard to power. Economic power equates to political power and as the wealth increases, so does the power and the numbers of people and presumably, the size of territory under those who hold power. This has been how the argument has also been presented for southern Africa and the archaeological evidence would also seem consistent with this sort of explanation. It cannot indeed be denied that there was a relationship between trade and the transition to statehood.”[iv]

Peter Garlake in relation to the development of Great Zimbabwe more or less reversed his earlier thinking in favour of local factors[v] and believed that the growth of the Great Zimbabwe state and its economy was largely a result of the growth of local wealth in the form of large cattle herds.[vi] For Garlake therefore, the Zimbabwe state development and survival were best explained in terms of the domestic economy and external trade was dismissed as peripheral.

More recent work by Stan Mudenge (1988) focused on the creation of the Mutapa state in present-day Zimbabwe discussing its probable origins, the economic organisation and political and religious organisation of the state.[vii]

Pre-Zimbabwe Culture; a very brief summary

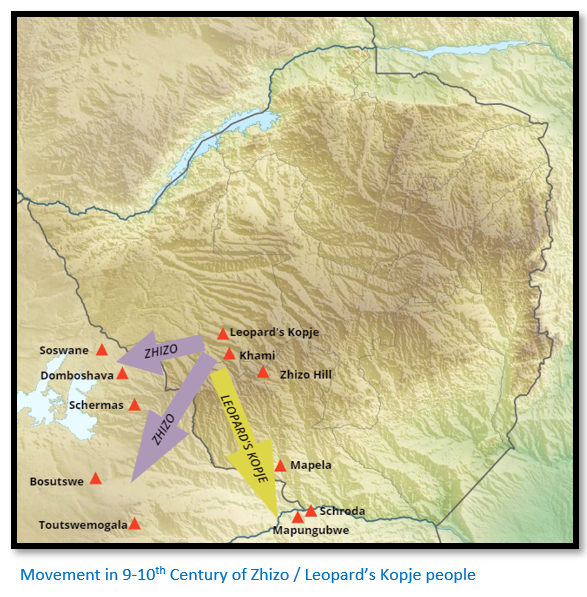

Pirikayi writes that Zhizo people lived in small villages, keeping livestock and cultivation millet and sorghum in the vicinity of Khami and the Shashe-Limpopo basin. By the 9-10th Centuries they moved westwards into the Kalahari peripheries and their place was occupied by Leopard’s Kopje communities whose origins are still not understood but are identified as the first Shona (Karanga) speakers in the region.

Mining, smelting and increased farming and trading resulted in a growing social complexity that resulted in an increasingly hierarchical and wealthier society which resulted in a new form of political development – the chiefdom.[viii]

Over time this political centralization led to the Zimbabwe Culture.

The Zimbabwe Culture summarised

Pikirayi identifies the most distinguishing features as:

- Dry-stone residences known as dzimbahwe’s and referred to as palaces by Main and Huffman with free-standing stone walls laid-out in systematic fashion

- Graphite burnished pottery

- Settlement patterns that separated the elite rulers from commoners

Pikirayi[ix] dates Zimbabwe Culture from the 11th to the late 19th Centuries and divides it up into three main cultural periods:

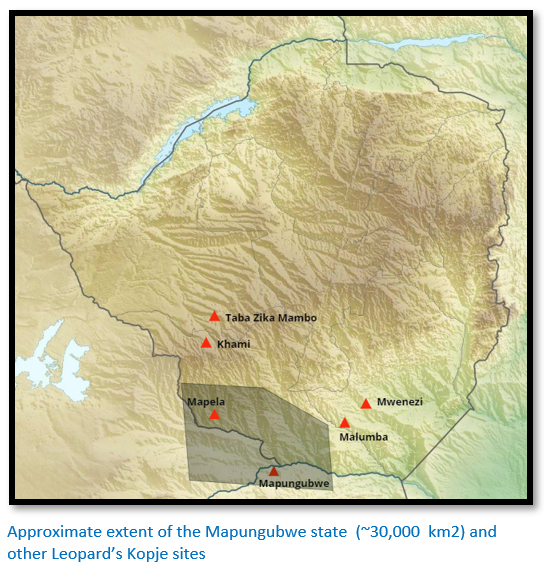

- Mapungubwe phase – which marks its earliest emergence from c. 1040 – 1270 in the dry mopane woodlands of the Shashe-Limpopo basin

- Great Zimbabwe phase – dating from c. 1270 – 1550 in the wetter Brachystegia-dominated miombo of the south-central Mashonaland highveld

- Decline of the Great Zimbabwe phase – which split into two regions:

(i)The northern plateau of Mashonaland south of the Zambesi river which evolved into the Mutapa state from c. 1450 – 1900

(ii)Torwa state based around Khami from c. 1450 – 1650, that was replaced by a Rozvi-Changamire state from c. 1680 – 1830

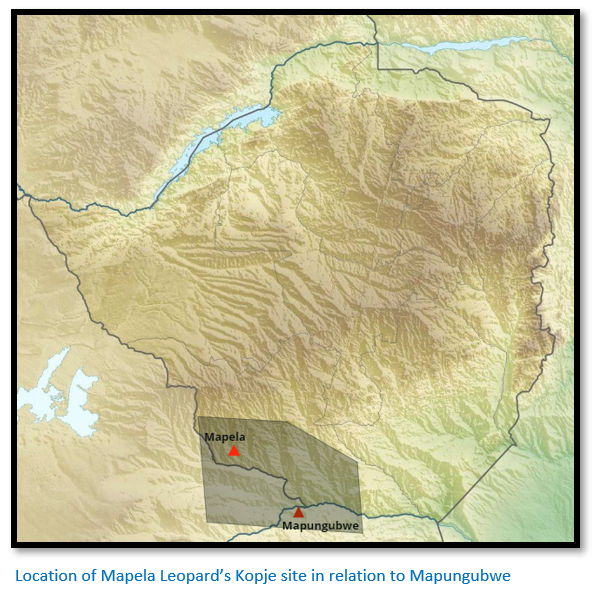

Mapela in south west Zimbabwe even pre-dates Mapungubwe

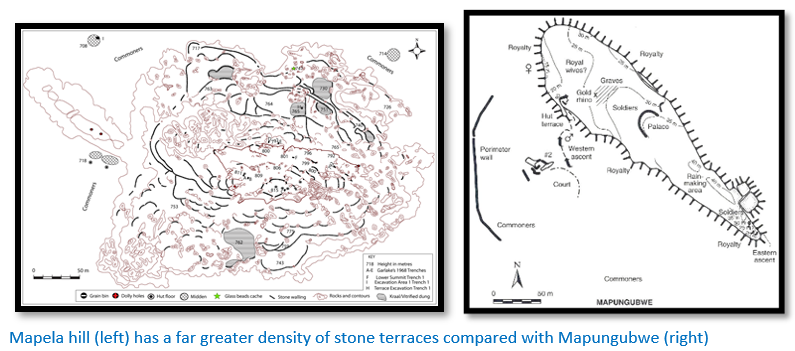

Zimbabwean archaeologists[x] have conducted excavations at Mapela Hill which:

- revealed massive stone-walled terraces supporting high-status residences whose initial construction date from the 11th Century CE, almost two hundred years earlier than Mapungubwe

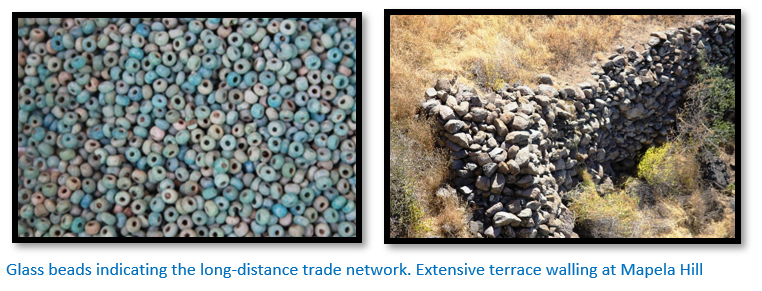

- The Mapela terraces and hilltop contain solid dhaka floors associated with elite housing and K2 pottery and glass beads

- With hilltop and flat area occupation since the 11th century CE, Mapela exhibits evidence of class distinction and sacred leadership earlier than K2 and Mapungubwe, the supposed origins of the Zimbabwe Culture.

On the basis of this freshly revealed archaeological evidence that the ruling élite lived inside dry stone-walled enclosures or on top of walled terraces and that commoners lived at the base of the hill with earlier dates from Mapela indicate that Mapungubwe can no longer be regarded as the only and original source of the Zimbabwe Culture.

Peter Garlake carried out test excavations on top of the heavily terraced Leopard's Kopje site of Mapela Hill and based on the known knowledge at the time concluded that from the solid dhaka houses, abundant glass beads and evidence of social distinction, that it was a capital of an independent Leopard's Kopje state, but he severely underestimated Mapela’s size.

The authors write: “Based on the available chronological and spatial data, it was assumed and widely accepted that Great Zimbabwe was the cradle of the Zimbabwe culture. Although archaeologists at the time recognised the broad similarities between glass beads and ceramics from Leopard's Kopje sites and those of Periods II and III at Great Zimbabwe, little attention was paid to the possibility that the Zimbabwe culture evolved out of the Leopards' Kopje and was therefore more important than was acknowledged at the time.”[xi]

They continue: “Based on cultural precedence, Mapungubwe became the origin of the Zimbabwe culture. In accounting for the rise of the Zimbabwe culture, Huffman speculated that the shift in power from K2 (Leopard's Kopje Phase I) to Mapungubwe (Leopard's Kopje Phase II/Early Zimbabwe culture) was concomitant with an ideological shift which crystallised sacred leadership and class distinction on Mapungubwe Hill in the early to mid-13th Century CE. Because Mapungubwe was thought to be the only Leopard's Kopje site with evidence of class distinction…”

The paper states that archaeologists tended to concentrate their efforts on the more important sites of Mapungubwe, Khami and Great Zimbabwe, but in fact many of the lesser sites including Mapela and Malumba belonging to the Leopard's Kopje Phase I (Mambo/K2) in south-western Zimbabwe possessed stone walling, dhaka floors and participated in long-distance trade – features of the Zimbabwe Culture in the early second millennium.

They conclude that the fieldwork mapping and excavations at the site to establish its spatial extent and the density of stone walling, as well as collecting samples for dating indicate that Mapela is easily the largest known Leopard's Kopje site in southern Africa. “Mapela flourished between CE1055 and CE1400 and therefore pre- and post-dates the generally accepted dates for the flourishing of Mapungubwe (CE1220–1300)”[xii]

Pikirayi classifies Mapela as the only known level 4 settlement[xiii] – presumably he means in this south-west region of Zimbabwe, but this may change as further work is carried out on the chronologically overlapping sites with Leopard’s Kopje Phases I and II pottery revealed in the region. Malumba may be an obvious candidate further to the east, but there at least twenty-five sites as far north as Ntaba Zika Mambo and extending west into present-day Botswana.

The importance of Mapungubwe

The environment here is semi-arid to arid and the best guarantee against crop failure were cattle. The large number of cattle figurines found by archaeologists in the vicinity of Mapungubwe attest to the important role they played in the local economy. Cattle owners became powerful members of the community, the wealth of their owner could easily be calculated by the number he owned and gave rise to an emerging elite who had a more elevated status compared to farmers and commoners.[xiv]

The most striking feature of the state as outlined by Main and Huffman is the location of the ruler’s residence on the summit of Mapungubwe hill itself. Previously a rain-making site and thus known as a sacred place, the site was appropriated by the ruler from about 1250 who had become the rain-maker himself and made it his royal house.

Archaeological excavations in the 1930’s showed that for the first time the royal house had been built on a platform built behind a stone retaining wall with even stone coursing and that the outline of the ruler’s dwelling: “was clearly designed to separate the leader from his family and followers, providing early evidence for ritual seclusion of a sacred leader.”[xv]

Going on they explain that sacred leadership in an African context “refers to the mystical relationship between the leader, his ancestors, the land and God. The king would appeal to God, through his ancestors, to make it rain – to ensure the fertility of the land and of his people. Rainfall thus depended on the ruler’s relationship with God, and a ruler’s power was based in part on the claim that his ancestors could intercede directly with God. The position of sacred leader was thus not hereditary as people believed that the ancestors appointed, or at least approved, sacred leaders.”

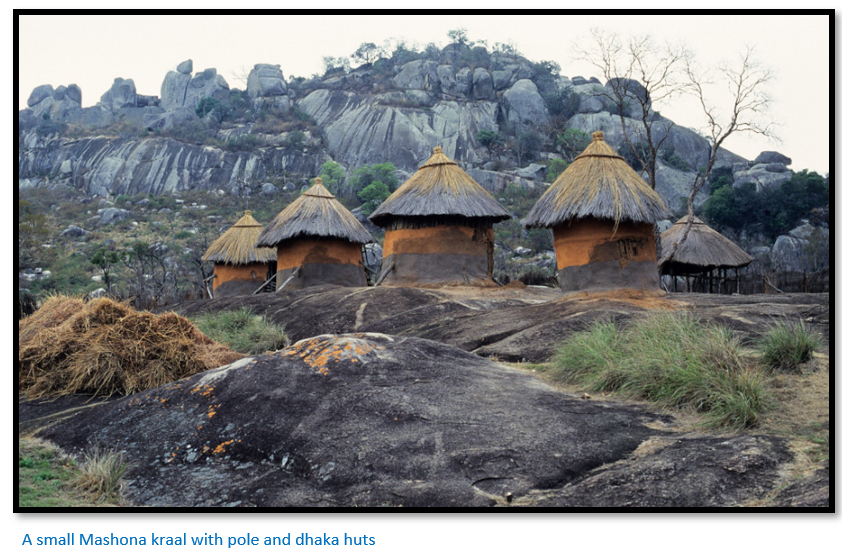

Understanding this concept underpins the African worldview and why the construction of so many dry-stone buildings took place within present-day Zimbabwe and surrounding territories. Another innovation were new types of houses with thick dhaka walls and hardened floors made with a clay and powdered granite known as ‘Zimbabwe cement.’ This type of construction entailed a great deal more effort and was a privilege of the ruling class. Pole and dhaka huts, grain bins and cattle kraals were built for commoners on the lower slopes and this pattern of settlement would gradually extend outwards from Mapungubwe.

The most important change was not so much the new building styles, but in the traditional link between land, rain and the ancestors being taken from the traditional rainmakers and assumed by the rulers at Mapungubwe. At the same time: “A key feature of this transition was the transformation of a society based on rank, in which status was determined by one’s relationship to the reigning chief, to one based on class, in which social position, by virtue of birth, gave access to power, prestige and basic resources unavailable to commoners.”[xvi]

Although it is accepted as being Southern Africa’s first state with a possible population at Mapungubwe of 3,000 to 5,000[xvii] and more than 120 village sites, identified by the same distinctive pottery in the Shashe-Limpopo basin, Mapungubwe seems to have flourished as a capital between 1075 – 1220[xviii] and after this period seems to have come to an abrupt end. Main and Huffman appear to attribute a later date to the demise of Mapungubwe, but this and the reasons for its decline will be discussed in a later article.

Although sited in South Africa, Mapungubwe should be identified as belonging to the Zimbabwe Culture as a level 5 settlement with a paramount Chief at its head.

Reasons for the rise of the Zimbabwe Culture

It’s still difficult to account for the emergence of the Zimbabwe Culture; possibly through a mix of growing wealth in cattle herds resulting in permanent settlements increasing in size and number which grew into a more complex economic and political structures and in parallel an emerging elite with an elevated status over the mass of commoners. Terracing and stone walling were built with solid dhaka bases and walls on suitable hill sites to provide the ruling elite with seclusion and privacy as they undertook ritual rainmaking activities. Beads, ivory, gold, pottery and imported ceramics and conus shells have been found in their middens.

Increasing wealth along with more complex hierarchal social organisation and a widened worldview brought about by increasing long-distance trade networks probably all played a part in creating an increasingly complex society. Dry-stone walling was also an initial feature of the Zimbabwe Culture.

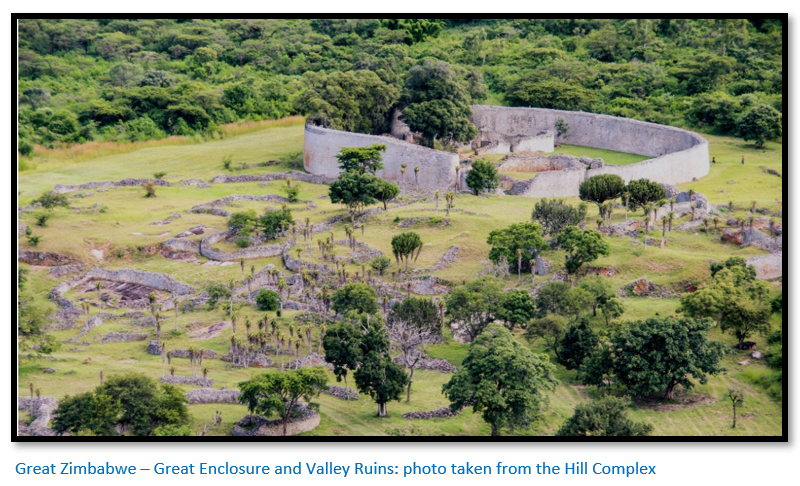

Great Zimbabwe

For a detailed description of Great Zimbabwe see the article Great Zimbabwe, a UNESCO World Heritage Cultural Site under Masvingo province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Originally settled by small-scale farmers who lived at nearby Gumanye Hill, Chivowa Hill and the Great Zimbabwe sites who kept cattle and made the same clay figurines seen at Mapungubwe and other Leopard’s kopje sites. This phase significantly predates any stone building tradition when it was primarily a rainmaking site.[xix]

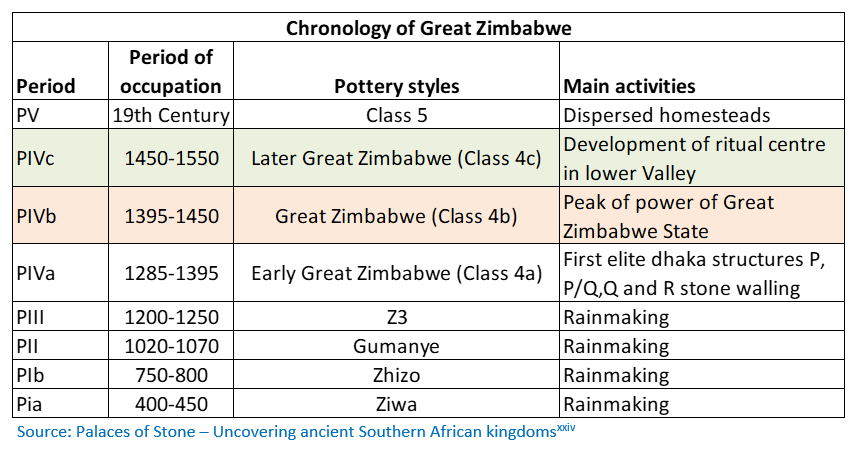

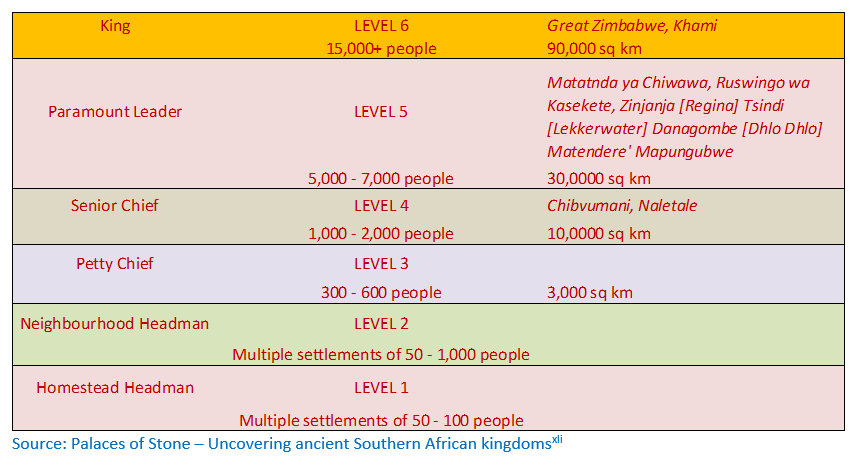

From the table below it can be seen that Great Zimbabwe existed as a rainmaking site from about 400 to 1250 when it appears to have supplanted Mapungubwe and following on from that place the Hill Complex on the summit of Zimbabwe Hill housed the ruling elite as the summit signalled the ruler’s position as sacred leader.[xx] “He was secluded from the commoners, living in privacy and isolation behind palace walls.” Again, as at Mapungubwe, the hilltop served as the most senior court for settling disputes between paramount leaders of level 5 [See table below] and here lived court officials and close members of the ruling family, the ritual sister and the King’s brother. Lesser royalty had their homes on the terraces built further down the hill and in the Valley Ruins where the ruler’s wives, children and their servants lived. Commoners would be living on the edges of the Great Zimbabwe complex.

Pikirayi writes: “The society at Great Zimbabwe was hierarchical in that the elite controlled agriculture, regulated external trade, and organized the lifeway of its people in general”[xxi] and also: “One must understand that Great Zimbabwe was more than an oversized African village. It was a town, a central African one, but a metropolis nonetheless. It was composed of many parts - elite residences, ritual centers, public forums, and presumably markets, as well as the houses of the commoners and artisans. It covered a broad area, [720 hectares] housing a large, vital population within a complex of massively walled structures. At its fluorescence it was one of the largest cities in Sub-Saharan Africa.”[xxii]

Estimates of the number of people living at Great Zimbabwe range from 11,000 to 18,000.[xxiii] Great Zimbabwe’s final decline as capital of the state came about 1450 and although the ruling elite may have left, the archaeological evidence in the dhaka structures makes it clear that commoners continued to live at the site for probably another century. (Periods PIVb and PIVc below)

Time sequence from the archaeological evidence

Mike Main and Tom Huffman give the above table sequencing the last 1,500 years of Great Zimbabwe with time periods linked with the pottery styles and major activities at the site.[xxv]

For the first 800 years the site was used for rainmaking ceremonies with nobody living on the hill at the time.

Main and Huffman believe that it was likely that initially Great Zimbabwe was an outpost of Mapungubwe and that its establishment would have taken place with the ruler’s approval.

From 1285 people displaying the political and religious ideology of the Zimbabwe Culture began to settle at the site – this period corresponds with the decline of the Mapungubwe state in the Shashe-Limpopo basin. A new ruler’s influence at Great Zimbabwe may have grown to such an extent that they established a new state and took control of the regional trade network linking the internal ruler’s palaces and the Swahili coast trade.

Whilst they also believe there may have been some succession with the ruling family from Mapungubwe moving to Great Zimbabwe, they do not think there was a mass movement of the general population. “Its decline and eventual abandonment were precipitated by a combination of events that included challenging climatic conditions and shifts in the regional gold trade. As Mapungubwe suffered, the leadership at Great Zimbabwe prospered.”[xxvi]

It maybe that Great Zimbabwe’s location on the southeast edge of the middleveld, between the highveld and the lowveld, was part of the reason for its location as a rain-making site for over 800 years. The higher rainfall meant that it was, to some extent, shielded from the droughts suffered by settlers in the Shashe-Limpopo basin and enjoyed greater crop yields as well as being good cattle country. Its position 200 kms nearer the coast than Mapungubwe may have given Great Zimbabwe an additional advantage in controlling the trade network from the copper and goldfields of present-day Zimbabwe and Botswana with the Swahili coast outlets at Sofala and Chibuene.

From about 1285 there are the remains of substantial dhaka hut structures along with the remains of pottery of the same type as found at Mapungubwe. For 150 years Great Zimbabwe thrived as the capital of the state….but around 1450 as at Mapungubwe, so eventually there is decline at Great Zimbabwe.

Period PIVb (1395 – 1450) from the table above marks Great Zimbabwe at the peak of its power as capital of the Great Zimbabwe state. Period PIVc (1450 – 1550) indicates the period when its political leaders moved north and founded the Mutapa state.

At the same time it appears that some of the sacred leaders moved to the site of Khami, west of present-day Bulawayo and established the Torwa state which flourished between c. 1450 – 1680 and its successor, the Rozvi state founded by Changamire Dombo c. 1680 – 1830.

By the time the Portuguese arrived on the Mashonaland plateau early in the 16th Century [See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] Great Zimbabwe had been largely abandoned.

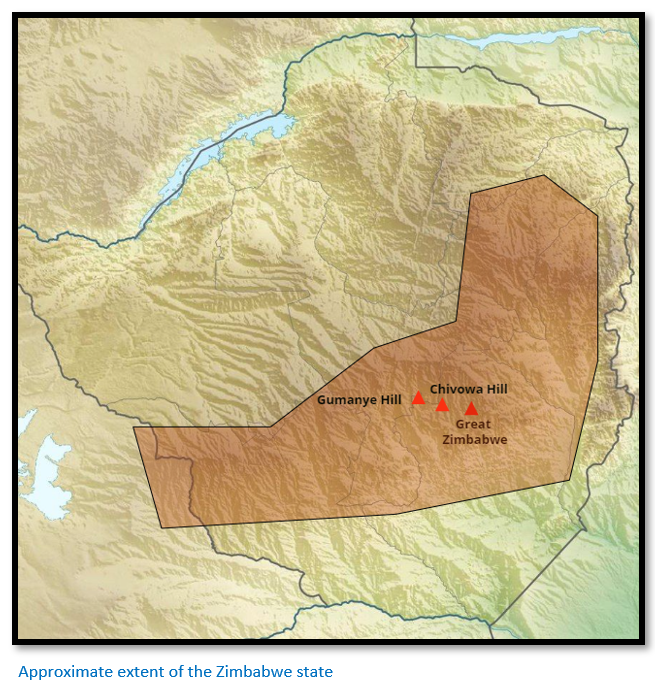

Effective area of the Great Zimbabwe state

Pikirayi states that the rulers of the south-central plateau: “probably exercised control as far east as the Sabi-Odzi basin and as far west as the Tuli river” although he acknowledges that there are dry-stone dzimbahwe beyond these borders whose status is still under debate.[xxvii]

Trade and Great Zimbabwe

Pikirayi suggests that although Great Zimbabwe was involved in the long-distance trade – finds of imported beads, ceramics, iron gongs testify to this, it may have be that Great Zimbabwe was not so much involved in trading, which was done through smaller, outlying dzimbahwe as in its regulation. Gold and copper mining were seasonal activities, but generally trade was: “but one variable in a complex mix of environmental, commercial and social opportunities that gave rise to the unique qualities of the Zimbabwe Culture.”[xxviii]

However by the mid-15th Century Great Zimbabwe had lost its ability to regulate trade between the plateau and the Swahili coast and at the same time commerce may have shifted from the Save route to the Portuguese settlements at Sena and Tete that grew in importance and the Zambesi Valley became the chief trade highway – a factor which favoured the northern political elites.

Possibly also in addition the potential agricultural land around Great Zimbabwe became subject to environmental deterioration: “the area could not sustain a heavy population without seriously eroding its agricultural and grazing potential.”[xxix

The rise of the Mutapa State

It appears that as Great Zimbabwe slowly declined in the 15th Century there was a gradual migration of those political elites described above to the west around Khami[xxx] generally referred to as Torwa or Guruuswa and called Butua by the Portuguese and also to the north and the plateau of northern Mashonaland which led to the establishment of smaller capitals of the Mutapa State. However they took with them the same cultural and the same spatial and walling traditions as at Great Zimbabwe.

Although the exact relationship between Great Zimbabwe and the Mutapa state is not known the archaeological evidence of the similarity of their locally-made pottery, weapons, agricultural tools and metal-working technology indicates a common source. For example, Zvongombe appears to have become settled about 1450.[xxxi] Main and Huffman name Matanda ye Chiwawa as the likely first Mutapa capital (NMMZ No 125/126) They state it is on the northern edge of the escarpment overlooking the Zambesi Valley rather than in the Dande area itself within the Valley which is referenced in the next chapter. No doubt further research will reveal more details.

Pikirayi notes that although the ‘elite’ stone-walled palaces of Great Zimbabwe, Khami, Danangombe (formerly Dhlo Dhlo) Nhandare (Naletale) and Matendere were not being built in the Dande region, a new form of socio-political complexity emerged within the villages of this region. He refers to the numerous ‘non-monumental urbanism which sprang up’ even as the urbanism of Great Zimbabwe declined.

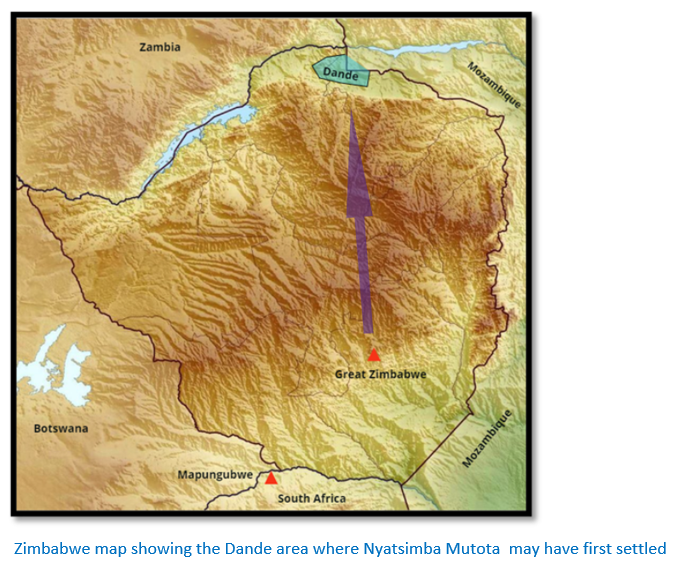

Evolution of the Mutapa State to the north of the Zambesi Escarpment

According to oral traditions from Guruve collected by Abraham in the 1950 – 60’s, Chibatamatosi the father of Nyatsimba Mutota sent Nyakatondo the messenger from Great Zimbabwe to the north of the Zambesi escarpment to look for salt deposits. The messenger brought back salt samples and told stories of the large elephant herds which convinced the ruler that they should move to the Dande area. Pikirayi believes: “it is inconceivable for people to migrate solely because of a shortage of salt, since it could be more conveniently obtained through established trading networks.”[xxxii]

Abraham's early work based on oral traditions attempted a history of the origins of the Mutapa state, its extent and a genealogy of the successive rulers. His work and conclusions, around the identity of the Mutota founder figure of the state and the link between the decline of the Zimbabwe state and rise of the Mutapa state have been questioned by other historians, including D.N. Beach. Beach thought they were a myth and argued that the Mutapa state came about before the fall of Great Zimbabwe.

Pikirayi reminds us that Great Zimbabwe was subject to drought, famine, locust swarms and disease; others have added deforestation and the movement of the Zimbabwe Culture may well have been brought about by a combination of adverse environmental factors that the movement to the northern plateau was how local people adapted to them.[xxxiii]

The movement to the Dande area in north-eastern Zimbabwe may well have involved just the ruling elite rather than the general population as the oral traditions say Nyatsimba Mutota then led his followers into the region and built a capital a ‘dzimbahwe’ on the slope of Chitako hill near the Utete River (NMMZ No 124)

Another oral tradition is that Nyatsimba Mutota broke away from Great Zimbabwe after going to war with either his brother or cousin over control of the Kingdom.

Some oral traditions speak of a ‘great army’ and even Wikipedia implies territorial expansion was achieved through military efforts, but in view of the scattered settlements identified by Gilbert Pwiti and cited below, this seems unlikely, and the process was probably more of a gradual peaceful cultural assimilation into the Zimbabwe Culture.

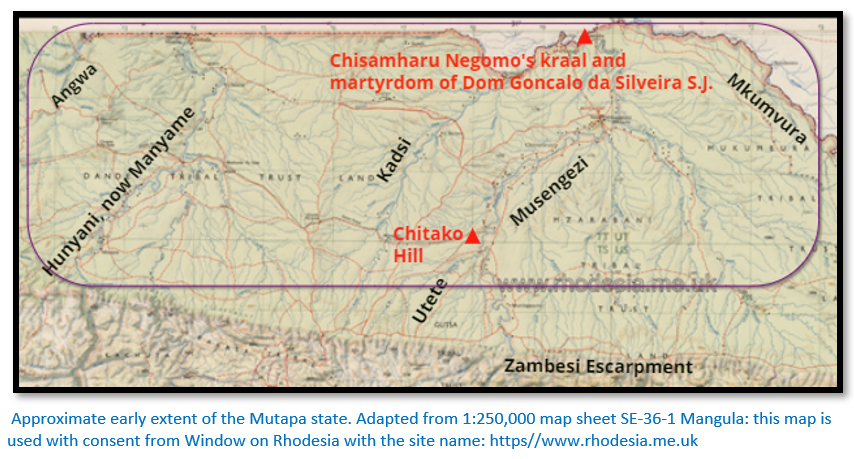

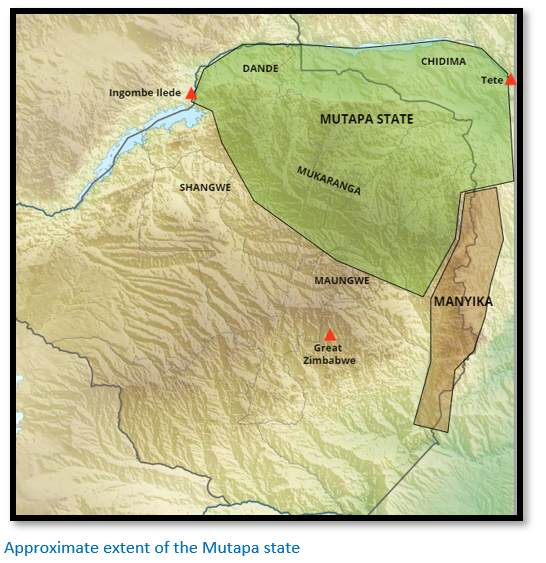

Mutota formed an alliance with the Tavara High Priest, Dzivaguru. On his death, his son, Nyanhenhwe Matope took over and ruled with his half-sister Nyamhitawho, who occupied the district of Handa and is often referred to as Nyamhita Nehanda.[xxxiv] Mudenge writes that Matope was the chief architect behind the expansion of the emerging Mutapa state gradually expanding it through a succession of alliances to reach from the Angwa and Manyame Rivers in the west, north to the Zambesi and west to the Musengezi and Mkumvura rivers with the Zambezi escarpment as the southern boundary.[xxxv]

Matope the first Mwene?

Mudenge quotes Pacheco in his account Uma Viagem as stating that Matope was the first to be called Muanamotapua (Munhumutapa) as the word meant “child captured in war” because his mother was a war captive.[xxxvi] But Abraham writes that Mwene Mutapa means “master of the ravaged lands” and was first used to describe Mutota, not his son Matope.[xxxvii]

Mudenge goes on to say that linguistically Mwene Mutapa would have been preferred by Tavara subjects and Munhumutapa would have been favoured by Karanga (Shona) speakers.

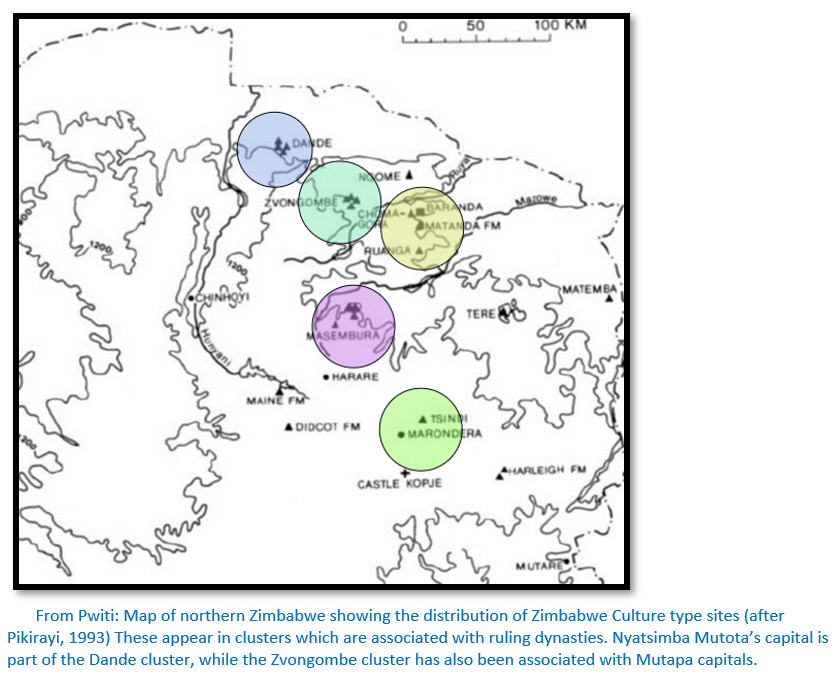

The rectangle on the map below marks the approximate extent of this early Mutapa territory.

The archaeologist Gilbert Pwiti found that scattered farming communities with characteristic pottery (usually termed Gokomere-Ziwa) had existed since circa 600 C.E. in this hot, arid region populated by large numbers of wild animals; subsistence farming was only possible along the riverbanks and livestock may have been limited as they were threatened by tsetse-fly. They may have existed alongside late Stone Age forager bands who moved between areas at times of natural harvest and who supplemented their diet with wild produce and game.

The larger rivers such as the Angwa, Manyama and Musengezi have a perennial flow, but the Kadsi and Utete rivers would be seasonal. These conditions probably led to archaeologists in the past neglecting the farming communities that existed here in the Zambesi Valley, but now contemporary archaeologists are correcting this situation.[xxxviii]

Sample survey areas revealed a wide range of village sites, some identified as Musengezi tradition by their characteristic locally-made pottery, others of the Zimbabwe Culture tradition whose pottery is usually burnished with graphite. An early iron-age site at Kadzi was excavated to provide further dates and other cultural information that revealed two periods of occupation: “an earlier occupation dating to the 5th Century AD and a later occupation dating to the 11th Century.”

The spatial distribution of the sites suggest they were self-sufficient with the majority of Zimbabwe Culture sites found at the foot of the Zambesi escarpment and usually within one kilometre of water. 28 sites were not identified as either Zimbabwe Culture or Musengezi tradition from the pottery remains which Pwiti believes may suggest they are from a later period. The location of these settlement sites seems to have been based on the availability of good soils for the growing of their staple sorghum and millet crops and the availability of year round drinking water from nearby watercourses.[xxxix]

Many of the customs, culture and language of Great Zimbabwe were retained in this embryonic state, whose population represents the northern expansion from Great Zimbabwe with their cultural traditions including their god ‘Mwari’ and the use of spirit mediums (Mhondoro’s) to communicate with the spirits of their ancestors. Senior spirit mediums included Dzivaguru in the north east, Nehanda in the central area and Chaminuka in the west.

Pwiti poses the question as to whether the Zimbabwe Culture settlement sites were those of autonomous or semi-autonomous chiefdoms or whether they represented shifting capitals of the Mutapa state. But in any case, it is from these expanding populations that the Mutapa state seems to have gradually emerged. Pwiti emphasizes that while there is a cultural connection between the earlier Great Zimbabwe and later settlement sites in north-eastern Zimbabwe, this is not to say that one state directly succeeded the other.

A regional trade network existed even in these early times

These earliest farmers were iron-users and produced pottery – they also were familiar with copper which was one of the inter-regional trade products along with glass beads from coastal centres and ivory hunted in the interior. Bark matting and spindle whirls suggest the local manufacture of cloth.

What the Zimbabwe Culture means

Main and Huffman argue strongly that a distinctive feature of the Zimbabwe Culture was a series of administrative levels, with each office bearer being a member of the ruling elite and often closely related to the royal line, such as brothers, uncles and sons being given these rankings. “The state was structured to support a governing class led by a sacred leader.

This leader was the primary channel for communication with God and his position was expressed through ubiquitous public and private rituals. His primary responsibilities centred on securing fertility of the land and the people, and defence through his court system and his army, should that be necessary.”[xl]

The hierarchy of political levels (i.e. rank) in Zimbabwe Culture

Portuguese records and Shona ethnography provide the evidence that up to very recent times that disputes between single homesteads to those between towns were settled at a men’s court. The judge or adjudicator in each level of dispute would be from the next higher hierarchal level.

Source: Palaces of Stone – Uncovering ancient Southern African kingdoms[xli]

Thus a dispute between members of a settlement would be judged by the Homestead Headman (Level 1) but a dispute between two homesteads would be judged by the Neighbourhood Headman (Level 2) between two different chiefdoms by a Senior Chief (level 4) with “each administrative level being the apex of a pyramid of lower courts.”

Each centre of importance would have a dry-stone building (stone palace) that housed the local leader who represented the Mutapa state’s authority.

A number of Portuguese accounts speak of the allegiance of all the provincial rulers being tested when messengers arrived from the Mwene with orders for all fires to be extinguished and then relit with coals from the Mwene. Those who refused to do so were considered to be rebelling against the Mutapa state’s authority and likely to be punished.

The political importance of land

In addition to settling disputes the hierarchy of political levels (explained in the table above) in Zimbabwe Culture was also important in the distribution of land usage. Title to land was dispensed by traditional leaders which effectively centralised authority from the simplest of homesteads into the hands of headman, chiefs and finally the King.[xlii] Pirikayi believes: “this traditional pattern of land and resource management, needed in the dodgy circumstances of drought-prone plateau environments, laid the groundwork for the emergence of social complexity in Zambezia. The different environments did not in themselves create complex stratified societies, but the social mechanisms required to support stable societies on the plateau did offer the opportunity for some descent groups to exalt themselves, using their control of important assets to gain ascendency for themselves and their clients.”

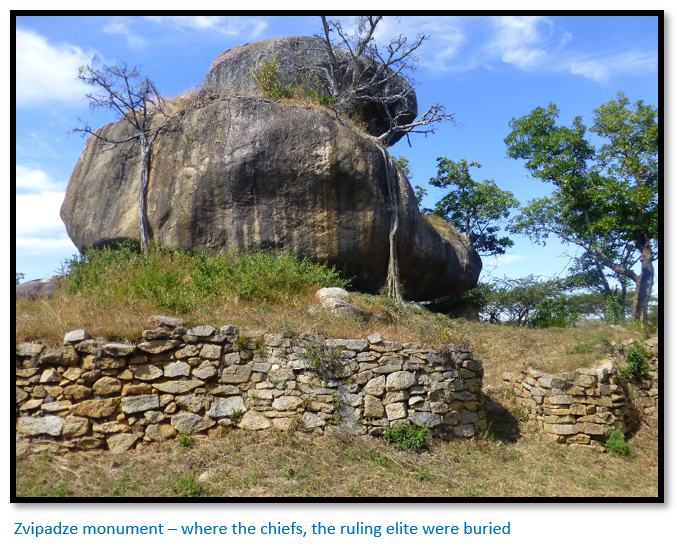

Zvongombe – a Zimbabwe Culture settlement

A number of articles refer to Nyatsimba Mutota establishing the first capital at Zvongombe[xliii] which the National Monuments of Zimbabwe website[xliv] lists as national monument No. 81 of ‘Zimbabwe Ruin’ type and situated 10 kms east of present-day Centenary.[xlv] Zvongombe is south of the Zambesi Escarpment and may be related to the Matanda ye Chiwawa referred to earlier.

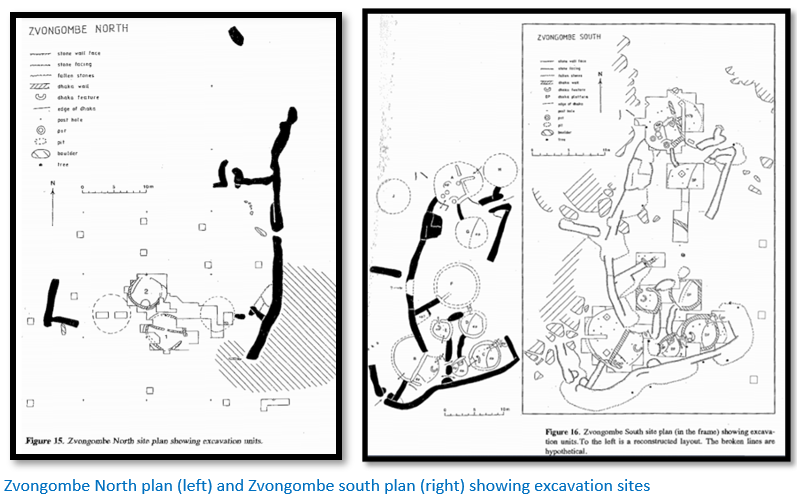

The Q-type walling at Zvongombe confirms though that it represented an example of the dry-stone buildings which are such a feature of the Zimbabwe Culture, and which do not appear north of the Zambesi escarpment. Pwiti’s archaeological research at the Zvongombe site tried to establish a link to the settlement sites to the north as well as links to the original Zimbabwe Culture established further south at Mapungubwe.

There are two stone enclosures on Zvongombe hill which has some exposed bare granite and boulders on the crest. The site is on a saddle which rises to a rocky knoll at its northern end. A survey of the hill has shown no significant archaeological remains on the surface, though this could have been obscured by grass and fallen leaves.

The Zvongombe North plan of the stone walls is of a rectangular enclosure of which only the eastern wall measuring 40 m is complete and has a plain entrance with curved ends in the middle. The southern end of the wall is 1.5 to 2.6 m high. The southern side of the enclosure was blocked by pole and dhaka huts.

Pwiti’s general impression from the depth of deposits and absence of any archaeological evidence was that the North enclosure was not occupied very extensively, or for any great length of time.[xlvi]

The stone walls of Zvongombe South are roughly rectangular in plan with an extension to the southwest, an outside radial wall to the west where the ground is rocky and uneven and some 10 m to the west drops sharply in a low cliff with shallow rock shelters below it. To the north the ground slopes down gently for 25 m to a pair of slightly overhanging boulders which guard the top of the steep slope down to the saddle and Zvongombe North.

The most interesting aspect of the excavations was eight pole and dhaka hut remains within the walls, with a further two huts at the north end. Pwiti states the site stratigraphy was more complex than that of Zvongombe North, showing evidence of much longer occupation and the features themselves were more complex.

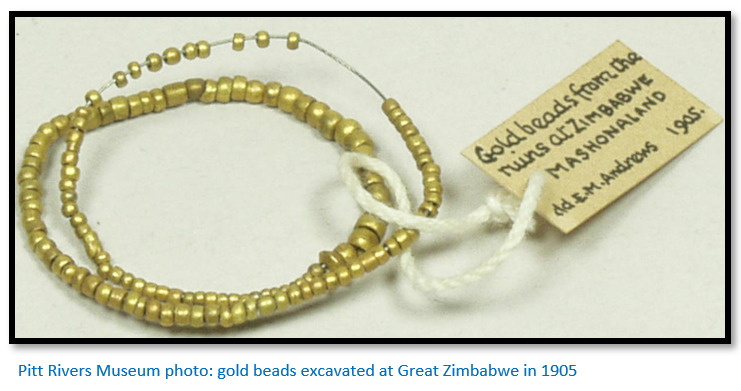

Apart from graphite burnished pots falling within the Zimbabwe Culture tradition, Zvongombe South excavations yielded arrow and spear heads, a gold bead and hoe.[xlvii]

Zvongombe compared with Nhunguza – both Zimbabwe Culture sites

Pwiti believes the only other Zimbabwe Culture site in northern Mashonaland sufficiently investigated to provide comparisons is Nhunguza northeast of Harare, excavated by Garlake in 1973. The Nhunguza site is of comparable size and has a radiocarbon date of AD 1580 +/-100 and like Zvongombe forms part of a group of ruins, having Chisvingo 1.5 km to the east and Garaubikirwe 5 km to the southeast. The radiocarbon dates from table 19 of Pwiti’s article vary from AD 1331 -1445 at Zvongombe south and AD 540 – 670 at Zvongombe north although the latter has just one sample.

At Nhunguza, Garlake identified eight houses within the enclosure with probably seven further houses immediately adjacent to it. Garlake identified four of the internal houses as 'sleeping huts', three other houses were probably 'living huts' and the eighth house, 8.20 m diameter with three rooms, was interpreted as a ceremonial house in which the ruler would have given audience. The position of this, forming part of the enclosure periphery, is comparable to Houses A and B at Zvongombe South but with different internal Features.

Pwiti believes the number of residents at Nhunguza and Zvongombe South would have been similar, although Zvongombe North would increase the number of residents for the site as a whole. However, the presence of three other neighbouring stone enclosures, supports the importance of the Zvongombe complex as a northern centre of Zimbabwe Culture.

Common threads between the Great Zimbabwe tradition in northern Zimbabwe and the early Mutapa state

Pwiti, like many archaeologists before him including Summers, Garlake, Huffman, Soper and Chipunza has attempted to link the two cultures through their dry-stone walling, locally-made pottery-types and domestic hut construction. It has been observed the sites have a tendency to cluster in fairly tight groups, with groups or single sites rather evenly spaced at intervals of 60 to 100 km.

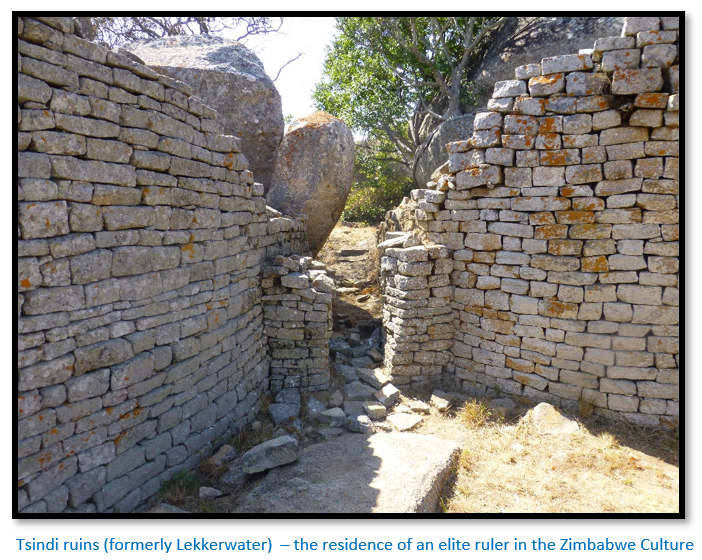

Pikirayi recognises Zimbabwe Culture sites on the northern Mashonaland plateau ranging: “from Harare in the south to the foot of the Zambezi escarpment in the north and from the upper sections of the Mazowe and Ruya in the west to the lower Ruenya Valley in the east.”[xlviii] Some of the sites he identifies include stone enclosures in the upper Mazowe, in Centenary at Zvongombe Hill, Tsindi Hill, Masembura and others at Ngome, Chikaniso, Ruanga, Chomagora and Matanda in the Mt Darwin area.

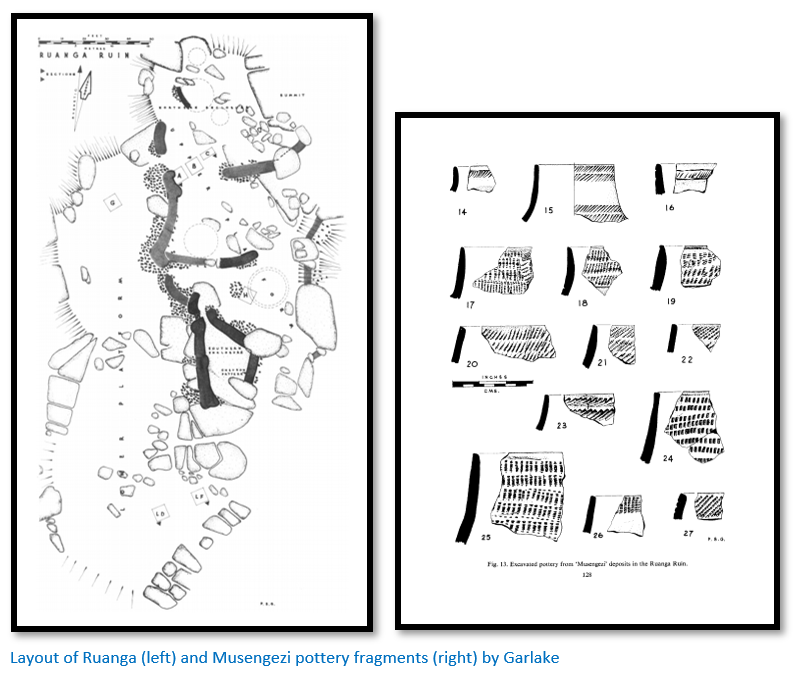

Ruanga – another Zimbabwe Culture settlement on the Mashona plateau

Ruanga is located on a small hilltop in the Umfurudzi Park and has good views in every direction. The site is composed of a lower platform and an upper platform. The upper platform is divided into four enclosures with short lengths of ‘type P’ dry-stone walling between granite boulders, the eastern wall has a length of chevron patterning and sections are built above a steep drop-off. The southern enclosure has ‘type Q’ better-quality dry-stone walling according to Garlake, the bare rock base is exposed and there were two upright stone monoliths in the centre of the wall. The limited areas in the enclosures restricted the total number of huts to eight according to Garlake, thick dhaka remains were present and the base of what may have been a grain hut with a stone base. There are three separate entrances from the lower platform where commoners probably assembled.

The excavations revealed that two separate groups inhabited Ruanga at different times. The earliest were represented by Musengezi pottery deposits as in the diagram above and found with the earliest huts on the lower platform. The later group is represented by the same pottery found at Nhunguza and Great Zimbabwe (i.e. polished smooth with graphite) with the bulk of these potsherds found on the upper platform. The layout and finds at Ruanga strongly suggest that a Zimbabwe Culture community established itself amongst mainly Musengezi farmers. Figurines of cattle and stylised humans were found similar to those found at Great Zimbabwe. Upper platform finds included - imported glass beads and pierced shell disks along with gold, copper and iron beads and iron ‘bracelet’ wire.

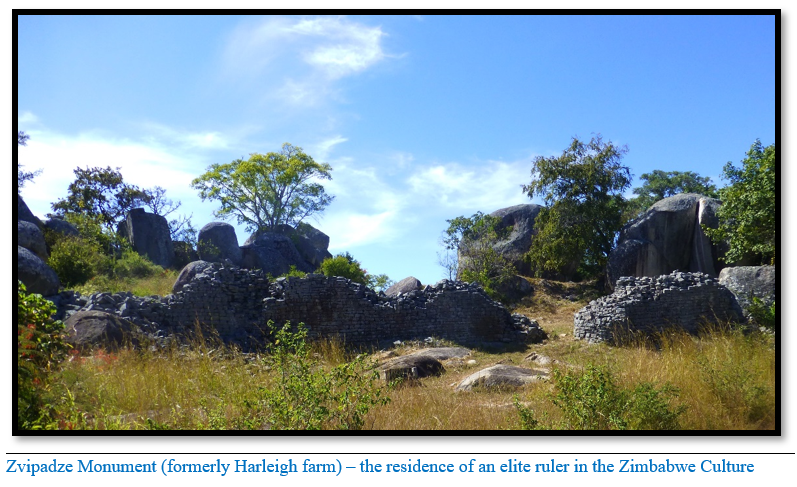

Peter Garlake described the Zimbabwe Culture in 1972

Garlake compared the Ruanga elite rulers living amongst local communities with the excavations at Great Zimbabwe, Tsindi formerly Lekkerwater and Zvipadze formerly Harleigh Farm and concluded they all belonged to the Zimbabwe Culture. He writes: “the evidence is seen to indicate a single, continuous, evolving occupation of Zimbabwe by one cultural group between about the early thirteenth and mid-fifteenth centuries: an extension of political power from [Great] Zimbabwe into northern Mashonaland during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, with which both the Nhunguza and Ruanga ruins can be associated; the abandonment of [Great] Zimbabwe in the mid-fifteenth century, coinciding with the rise of the Mwene Mutapa kingdom in the extreme north of Mashonaland; a decline of building in stone throughout Mashonaland shortly afterwards and the rise of a second state, in southwest Matabeleland in the seventeenth century, which was responsible for the Khami ruins and other ruins in similar styles. All the ruins are seen as the power and manifestation of the power and authority of a small ruling group that lived in them, sustained by the labour and production of a much larger population. The results of the Nhunguza and Ruanga excavations can be seen to fit into and amplify this framework.”[xlix]

“…Huts associated with the stone walls at Nhunguza and Ruanga, with their thick walls of solid daga are built identical with the dwellings at [Great] Zimbabwe Ruins built during Periods III and IV.”[l]

Later in the same article Garlake adds: “The stratigraphy of Nhunguza, the shallowness of the deposits and the absence of any evidence that any hut had been altered, added to or rebuilt, suggest that the enclosure was not occupied for any length of time, probably no longer than a generation. The proximity of Chisvingo and the Yellow Jacket ruin to the Nhunguza ruin suggest that the three ruins lie in the nuclear area of a polity and that they may have been built and occupied by successive generations of a ruling group. This may have been no more than a minor provincial chieftaincy, for the ruins are not large and the Nhunguza ruin had yielded few exotic finds.”[li]

The relationship between the Musengezi and Zimbabwe groups at the Ruanga Ruin

Garlake writes: “It is apparent from the finds that two separate groups lived on the site of Ruanga. The Musengezi people built only flimsy huts. They had metal tools or weapons, but few personal adornments of gold, copper, iron or glass were found. Their pottery differs from Zimbabwe pottery in finish, decoration, vessel shape and rim shape and includes a wide range of vessel types. Figurines were found only in Musengezi deposits.

In contrast the Zimbabwe people at Ruanga built stone walls enclosing huts with thick walls of solid daga embellished with mouldings. They wore gold, copper and iron ornaments and seem to have had much readier access to imported beads. Their pottery had little or no resemblance to Musengezi wares and was limited to a very small range of vessels. These differences are sufficiently wide-ranging and extreme to demonstrate that the two groups were sharply culturally distinct and shared little more than a basic Iron-Age economy and technology. They differ to a degree that suggests that they belonged to two unrelated population groups or tribes that just had little or no previous contact with one another…

The stratigraphy of the site makes it clear that the Musengezi people were the first occupants: the earlier midden contained predominantly Musengezi pottery and was sealed by a series of deposits of the [Great] Zimbabwe type…

It is possible that the area of Nhunguza had also been earlier inhabited by people of the Musengezi people, for the small collection of sherds from the top of the natural subsoil of this site were all ungraphited and included a bowl decorated with a bead impression.

There is no possibility that the Zimbabwe group were influenced culturally by the Musengezi people: buildings, pottery, metalwork, adornments and beads are all sharply distinct and there are no transitional forms.”[lii]

Other Historians and Archaeologists views

Beach recognised a gradual movement of Karanga dynasties northwards to introduce the Zimbabwe Culture into northern Mashonaland, but not necessarily as part of an expanding Zimbabwe state. From one of these dynasties, he believed the Mutapa state then emerged.

Pwiti suggests the various dynasties, perhaps recognising the potential in the trading and other economic opportunities, may have banded together for the fuller exploitation of the resources and opportunities and from these a ruling Mutapa state may have emerged.

If the Great Zimbabwe state was declining in the middle of the 15th Century then radiocarbon dates from Zvongombe from the early part of the 15th Century and later for Kasekete (NMMZ No 80) seem to indicate an embryonic Mutapa state was already in the making. Dates from other Zimbabwe Culture sites in northern Zimbabwe range from the l4th to 16th Centuries.

There appears to have been an initial expansion of the Zimbabwe Culture northwards at some stage in the early part of the 15th century, or even earlier which can be seen as elite rulers moving from Great Zimbabwe into the Dande area of the Zambesi Valley as evidenced by the cultural links and later resulting in the establishment of the Mutapa state.

Then at a later date, sites like Zvongombe and the valley cluster, dating from the 15th Century onwards, would represent the shifting capitals of an established Mutapa state, an idea suggested by Beach and Sinclair. Contemporary and later Portuguese documents clearly show that the Mutapa state was already established and Great Zimbabwe was no longer the major centre it had been.

Abraham and Huffman’s oral traditions then tie-up with the later Zambezi valley cluster of stone buildings with the Mutapa state and Pikirayi's more recent archaeological work in the Mount Darwin area at Baranda Farm. By the 16th Century, northern Zimbabwe was the centre of major external trading activities which are associated with the Mutapa state and can be associated with state power (Pikirayi 1993).

How did the people of the Zambesi Valley become dominated by the Zimbabwe Culture?

Pwiti admits that the extensive archaeological work he and his team carried out amongst the local Musengezi people of the Zambesi Valley does not reveal if they came under the control of the Zimbabwe Culture. However, he says there is no archaeological evidence of military conquest. None of the dry-stone buildings are particularly defensive in design. The only weapons found were used in hunting, so military conquest can be ruled out in the formation of the Mutapa state. Nor was the movement into the Dande area a response to political or military pressure in the area of Great Zimbabwe. At a later date the Mutapa state did have armies as the Portuguese records testify.

A hierarchy of political levels probably existed before the arrival of the Zimbabwe Culture

Pwiti suggests that a three-tiered hierarchy may have already existed within Musengezi settlements with small hamlets of less than 400 m2 that reported to a higher level settlement of one hectare in size. Four of five of these were in turn ruled by an administrative centre with Mbagazewa given as an example. This would have made assimilation with people from the Zimbabwe Culture an easier process.

Number of known sites

Main and Huffman write that a significant number of dzimbahwe’s (stone palaces) are found throughout southern Africa, By 1994, as reported by archaeologist Lorraine Swan, the National Archaeological Survey of Zimbabwe had listed 189 ‘dzimbahwe’ sites and eighty-three Khami sites…Peter Garlake mentions a further 100 sites…an additional 50 sites have subsequently been described…bringing the number of known sites in Zimbabwe to approximately 422, with a further 113 Zimbabwe Culture walled sites in Botswana, 27 in South Africa and a further 4 in Mozambique. A total of 566 known sites.

Clearly some of these were built before and after the period covered in this article and include the Mutapa state as well as other states but give an indication of the total number of dry-stone buildings that have been constructed in the region. [See also the article Zimbabwe’s dry-stone buildings; an article on their extent and meaning under Masvingo province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The terms Mwenemutapa and Momomotapa

The title Mwenemutapa is often translated as ‘Lord of the plundered lands’ but this seems at odds with the archaeological record which does not indicate any military force or coercion was behind the gradual assimilation of cultures.

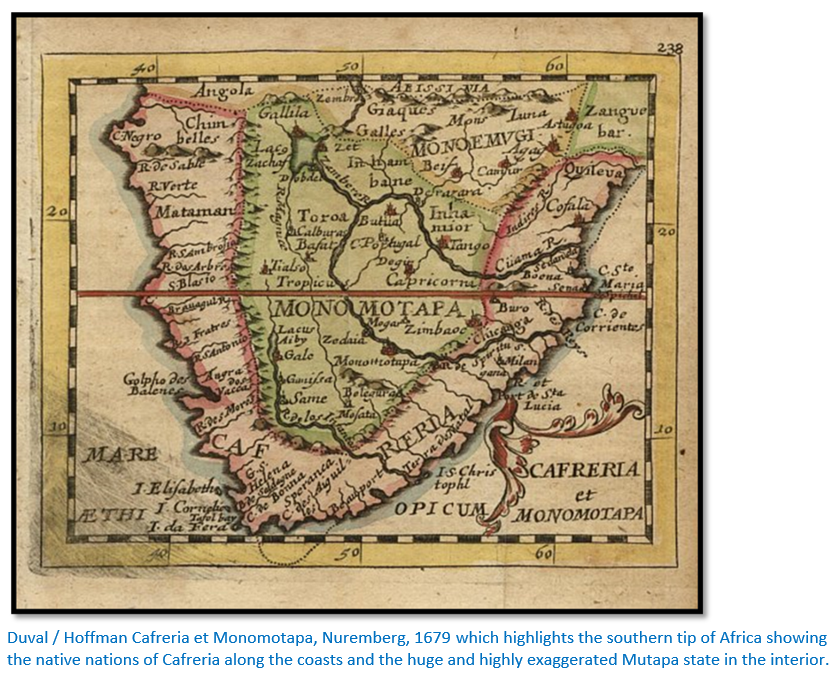

Other translations say the title Mwenemutapa derived from a combination of two words Mwene meaning King or Lord, and Mutapa meaning land.[liii] Over time the monarch's royal title was applied by the Portuguese to the kingdom as a whole and used to denote the kingdom's territory on maps from the period.

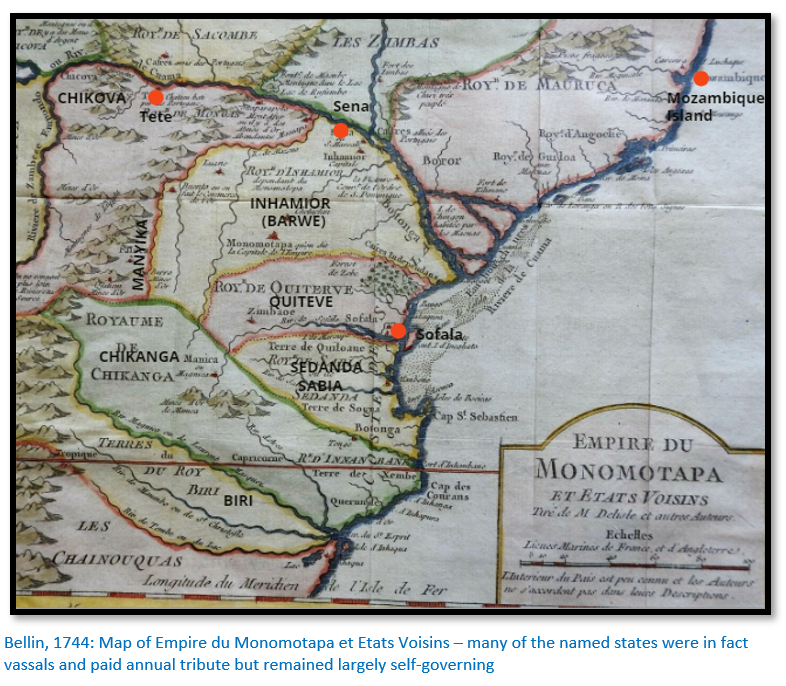

The extent of the Mutapa state

Amongst the first Portuguese descriptions was a letter written by Diogo de Alcacova to Sebastião I in 1506 a year after the Portuguese established a permanent presence at Sofala who says: “The kingdom, sir, in which there is the gold that comes to Sofala, is called Vacalanga [present-day Karanga] and it is a very large kingdom…Sofala itself belongs to this kingdom, if not all the land along the shore. The name of the king is Menamotapam, and of the kingdom Vacalanga.”[liv]

Alcacova also wrote that Vacalanga, which in the local languages is the plural form of Mocalanga, or Mokaranga, was the kingdom of Monomotapa.[lv]

Main and Huffman state: “that during the whole of the Zimbabwe Cultural period (1250 – 1840) highly organised states (levels 5 and 6) at one time or another covered an area the size of France.”[lvi] Wikipedia states France covers 643,807 km². As Zimbabwe covers 390,757 km², this area would include a large portion of Mozambique and part of Botswana.

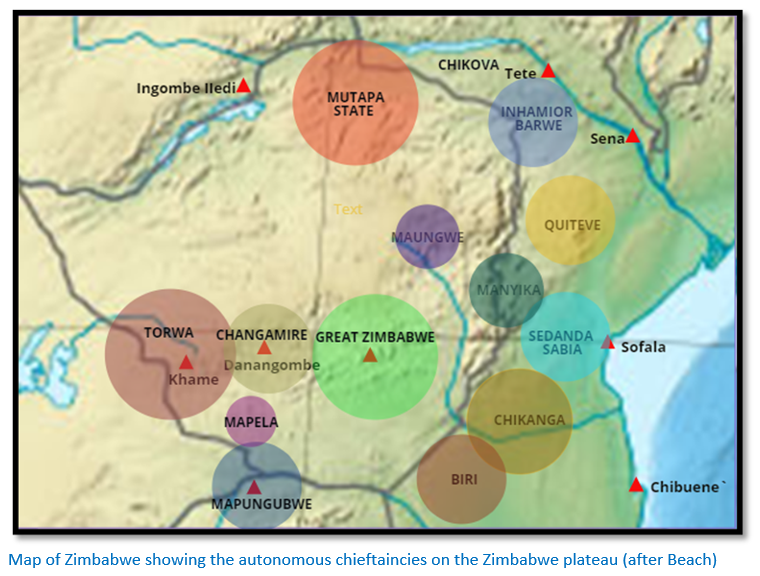

They are clearly referring to the group of states comprising Mapungubwe, Great Zimbabwe, Mutapa, Torwa, as well as all the vassal states of Inhamior, Quiteve, Sabia Chikanga and Manyika. Later they refer to the Mutapa state having authority over 30,000 km² - an area encompassing the Zambesi Valley and northern plateau of Mashonaland probably as far south as Harare and at times the vassal states to the east referred to above.[lvii]

Stan Mudenge’s maps of the Mutapa State show a similar area in size to the above map but should be viewed with caution as much of what he describes as Mutapa state were in reality vassals who paid annual tribute but were largely autonomous in governing their own affairs.[lviii] His maps almost convey the belief that the Mutapa state extended from the East African coast around the Zambesi river delta to the Makgadikgadi salt pans in present-day Botswana. It’s not possible that the Mutapa state in the 16th Century could have administered such an area.

The inhabitants of the Mutapa state and present-day Zimbabwe

Mudenge defines the Karanga as the historical name of the Shona-speaking people who live in present-day north and central Zimbabwe and central Mozambique and the historical cattle-owning people of central and north-eastern Shona dynasties that migrated from Great Zimbabwe and founded the Mutapa state. Karanga is derived from the term Mocaranga which according to Portuguese documents is how the people described themselves. Some of the quotes below fall into a later period then is covered in this article but are included for completeness and are all from Gai Roufe’s article.

The Karanga states in the 16th and 17th Centuries comprised the Mutapa state (Monomotapa) with their vassal states including Quiteve (Kiteve) Manyika, Sabia (or Sedanda) and the Chikanga.

The Dominican friar João de Barros wrote: “This Kingdom of the Manamotapa is situated in the lands called Mocaranga…In the past these lands were all part of the empire of the Manamotapa and are now divided into four kingdoms; the kingdom that the Manamotapa has today, the kingdom of the Quiteve, the kingdom of the Sedanda and the kingdom of the Chicanga.”[lix]

Elsewhere in the same source de Barros writes: “The Manamotapa and all his vassals are Mocarangas, the name they have because they live in the lands of Mocaranga and because they speak the language called Mocaranga.”

In the 1630’s Antonio Bocarro writes: “From Sena to the south, twenty walking days, is the Mocaranga, which is the kingdom of the Manamotapa…In addition to all these kingdoms, there is another kingdom, bigger and more principal, which is the Mocaranga, where the Manamotapa lives with his court.”[lx] Elsewhere he includes the kingdom of the Chicangaas and Sena town.

Pedro Barretto de Rezende, secretary to the viceroy of India, wrote in 1634 that: “The empire of Manamotapa is named Mocranga (sic)…The kingdoms that are subject to this empire are that of Quiteve, which borders Sofala…that of Manica, that of Baro and that of Batonga…the kingdom of Maungo, that of Bire and that of Boaca…”[lxi]

Perhaps the accumulation of large-scale cattle herds and knowledge of the external trade were the means by which the Zimbabwe Culture gained ascendancy in the Zambesi Valley?

Pwiti suggests these two factors may have played a part. The archaeological evidence shown by pottery finds indicates the Musengezi and Zimbabwe Cultures lived in the same areas, but apart from each other. He suggests that the Zimbabwe Culture did not seek to dominate the Musengezi Culture; initially they remained culturally distinct but interacted peacefully.

In the same way in a political context the emerging rulers from the Zimbabwe Culture would have made allies of the Musengezi chiefs, rather than seek to destroy them. However, knowledge of the external trade and management of large-scale cattle herding would have allowed the Zimbabwe Culture to become dominant in an emerging Mutapa state.

Main and Huffman write that the domestic economy throughout the period was based on agriculture (e.g. sorghum and millet cereals) and pastoralism…the fact that the Zimbabwe plateau is free of tsetse fly because of the cold winters facilitated the growth of large cattle herds that were usually kept in far-flung cattle posts and not at the population centres.

Cattle formed a critical part of the political economy because they were a store of wealth determining an individual’s status, the number of wives and children they could afford and the lobola[lxii] they could pay. Additionally, they argue that commoners within Zimbabwe Culture period owned few livestock and had to borrow cattle from the ruling elite when it came to marriage and were thus bound into a cycle of dependency.[lxiii]

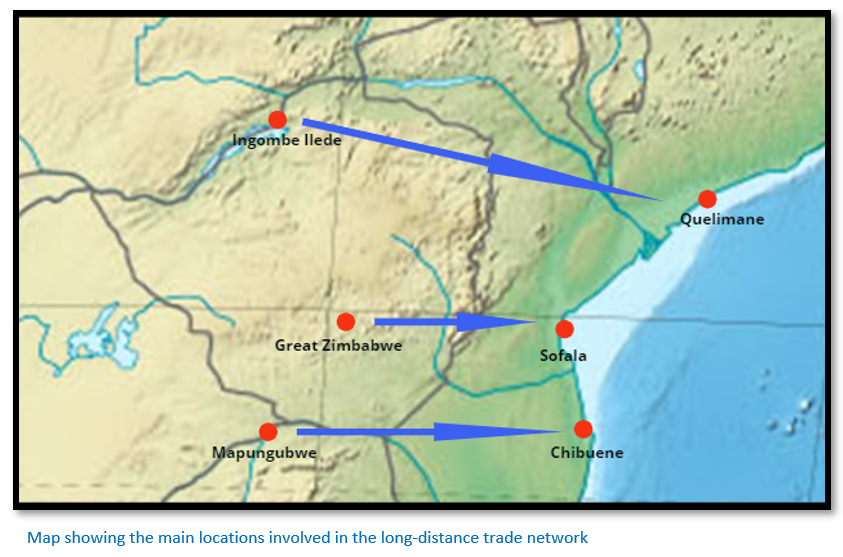

The long-distance trade between the Mutapa state and the Swahili coast

Main and Huffman write that there is plenty of evidence pointing to the existence of a trade network even prior to the establishment of Mapungubwe at K2, the Leopard’s Kopje capital and predecessor which lasted from about 1000 to 1220.[lxiv] Archaeological excavations have uncovered large quantities of imported glass beads from south or south east Asia which must have been obtained from Swahili traders on the east coast, most likely at Chibuene.

We know that Mapungubwe was also connected by trade with the east coast and that gold from south western Zimbabwe and eastern Botswana was traded with the same Swahili traders through Chibuene and the Bazaruto archipelago.

Great Zimbabwe is geographically nearer to the coast than Mapungubwe and the network probably used the Save river to access the coast at Sofala, the local hub of the gold trade which started as a small trading post in the 10th Century[lxv] and by the late 13th Century when trade with Great Zimbabwe was flourishing came under the control of the Kilwa Sultanate. Another route for the gold trade of the interior was via the Buzi river to present-day Manicaland.

Great Zimbabwe’s location gave it an additional advantage in controlling the trade network from the copper and goldfields of present-day Zimbabwe and Botswana with the Swahili coast outlets.

Ingombe Ilede featured in the 16th Century regional trade networks when glass beads, shell beads, cowrie shells and cloth were imported and copper crosses from Katanga and the Copperbelt along with ivory, slaves, salt and gold were exported. Recent dating of cloth from the burial sites gives dates of mid-15th Century to mid-17th Century (i.e. contemporary with the Mutapa state) and the burials showed some persons of high status from their burial goods and others without grave goods probably belonged to commoners. All of which fits into the Zimbabwe Culture – a future article will reference Ingombe Ilede for this reason.

Amongst the items exported from the Mutapa State were ivory and gold, copper and animal hides such as leopard.

Items imported on behalf of the elites were Persian and Chinese ceramics, cloth, glass and ceramic beads and glass objects, items of cutlery and manufactured wares such as hawk bells, bracelets, iron gongs and coins.

Buildings of dry-stone walling cease to play a significant role in the Mutapa state

Pikirayi believes that residences for the elite ruling class were no longer being built using well-coursed dry-stone walls on the northern plateau after 1550. However, the populations of non-stone-walled towns grew much larger.

He cites Baranda Farm near Mount Darwin (Mt Fura) where an extensive site survey was carried out that revealed imported ceramics and locally manufactured pottery of Zimbabwe Culture origin as seen in rolled rims, graphite burnishing and red ochre.[lxvi]

He quotes Joao dos Santos, who worked as a missionary at Tete in the Zambezi valley from 1585 to 1595, and whose account is mostly borrowed from earlier Swahili traders and is clear that royal palaces were no longer built in stone. He noted instead that “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass” (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 7, p. 275) and adds: "The dwelling in which the Monomotapa resides is very large and is composed of many houses surrounded by a great wooden fence, within which there are three dwellings, one for his own person, one for the queen, and another for his servants who wait upon him within doors. There are three doors opening upon a great courtyard, one for the service of the queen, beyond which no man may pass, but only women, another for his kitchen, only entered by his cooks." (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 3, pp. 356-7)

Such settlements could incorporate an area over a ‘league’ (about 5 kms) in circumference with houses constructed within a stone throw of each other (Mudenge 1988, p. 78) and populated by tens of thousands of inhabitants (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 3, p. 208) Centres of this size clearly demanded the new ‘form of socio-political complexity’ that has already been mentioned.

The economic basis behind the development and survival of the Mutapa state

Although the subject of much research, particularly from Portuguese records, Pwiti feels the economy is best covered by Mudenge.

Most of the economic production was in the fields of livestock herding, mining, participation in long distance trade and agriculture. They are each evidenced by:

- faunal remains

- finished metal products such as hoes and axes used for clearing lands, spears and arrows for hunting as well as iron slag from mining activities

- Imported goods (mainly glass beads and ceramics)

- Agricultural remains are rare, but well documented by the Portuguese

We see from Pikirayi’s research at Baranda Farm site that external trade was important to the Mutapa state, but agricultural production and livestock herding came first. Fr. Monclaro wrote that when the Momomotapa wanted gold he sent a cow to those of his people who are to dig and it is divided among them according to their labour and the number of days they are required to work (Monclaro 1569) Thus cattle rearing clearly supports trade, which in tum supported the political subsystem.

In addition, the people besides producing for themselves, produced for the state as well. Tribute was collected through actual agricultural produce or through the supply of agricultural labour. Mudenge writes that one day out of each month, different parts of the state offered labour to the royal fields, the zwzde.

Many historians in the past have argued about the importance of the long distance trade network, but today most historians believe the Mutapa state was not sustained by participation in long distance trade alone, but by the integration of the various strands of economic production outlined above.

External trade and the early Mutapa state

In 1505 ships captained by Pêro d’Anaia arrived at Sofala, which until then had been a Swahili Muslim trading post, with the express aim of establishing a secure foothold, the first fortification built by Portugal, on the coast of East Africa. Named Forte de São Caetano de Sofala its function was to monopolize the gold traffic coming from the interior, from the Mutapa state.

The Karanga people had enjoyed a flourishing trade with the Swahili Arabs at Sofala from at least the 10th Century and probably before that from Mapungubwe in the Limpopo river Valley. Although the exact numbers of Swahili trading in Mashonaland is difficult to assess, they were trading in gold and ivory for many centuries prior to the Portuguese arrival.[lxvii]

When the Portuguese first arrived at Sofala in 1505 they expected rich pickings. The first clerk of Sofala fortress, Diogo de Alcacova in 1506 reported that at its’ peak over a million meticais[lxviii] of gold per year was traded by the Swahili traders at Sofala annually. But Portuguese hopes were quickly dashed as the trading results in 1506 showed just 8,176 meticais of gold and much of it came from Portuguese raids on the Swahili trading posts. For the period 1506 to 1518 in the five years for which records survive, a total of only 54,887 meticais of gold are recorded. [See the article Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century? under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Within the first two years of establishing Sofala the Portuguese realised that the gold trade had shifted north, and the Swahili traders were now exporting their gold and ivory down the Cuama (Zambezi) river and using Angoche as their trading post and not the Sofala trade routes. Often however their reports stated that tribal wars were interrupting the trade. They needed to explore and gather information on the gold trade of the interior themselves and break free of relying on the few remaining Swahili traders at Sofala.

Antonio Fernandes undertook two journeys into present-day Zimbabwe in 1511-12 which are described in the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com with his reports dictated to the clerk Gaspar Veloso in early 1516. They dealt mainly with the chiefs he encountered, the gold mines of the interior and the trade fairs “Sembaza fairs” organised by the Mutapa state at which Swahili Arab merchants played a significant part.

In 1516 Antonio Fernandes made a third journey into the interior up the Zambesi (Cuama) river and provided further information of where to go and obtain gold in present-day Zimbabwe. Sena and Tete on the Zambesi came under Portuguese influence and control in 1530 and 1531 respectively. The 1530’s saw a marked shift in Portuguese trading activities from the south at Sofala to the north along the Zambezi river. From these towns they established feiras which will be the subject of a later article.

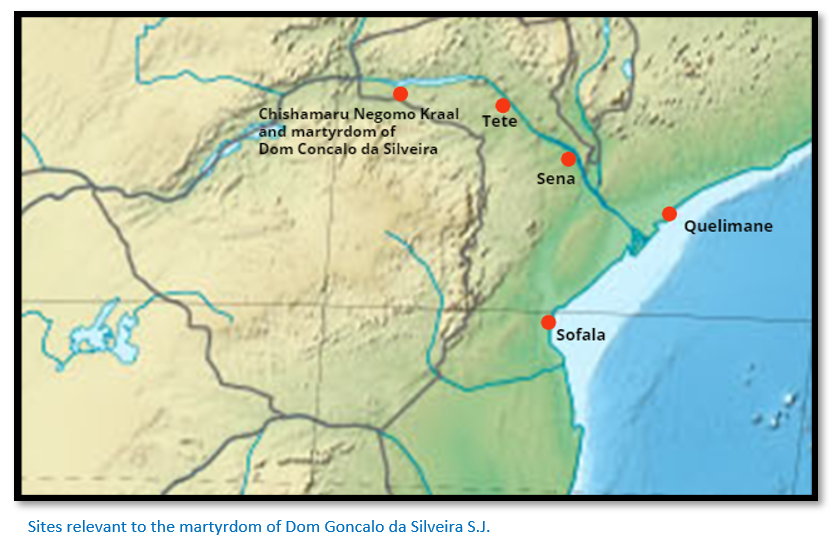

The Portuguese have hopes of converting the Mwene to Catholicism

Father Goncalo da Silveira travelled as the head of a Jesuit mission with Friars Andre Fernandes and Luiz Froes to the Mutapa state in 1560. A detailed map of their journey up the Mazowe river and west through northern Mashonaland to the kraal of the young Chisamharu Negomo on the upper Musengezi river is in the article the 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.co.

Chisamharu Negomo had only become Chief the same year succeeding his father Chivere Nyasoro but was already being threatened by a pretender called Sachiteve Chipute, who no longer had a claim to be ruler, but saw an opportunity existed. Chisamharu probably hoped his welcome to this muzungu Mhondoro/Nganga[lxix] would be reciprocated with strong Portuguese support against his rival.

Chirenje quotes Charles Boxer: “Whatever motives had originally inspired the Portuguese voyages of discovery after the capture of Ceuta (in 1415) Christians and spices were what they chiefly hoped to find when they actually reached India. This close association between God and Mammon formed the hallmark of the empire founded by the Portuguese in the East, and, for that matter, in Africa and in Brazil as well.”[lxx]

Stan Mudenge[lxxi] says the Swahili Muslim merchants and Portuguese traders on the lower Zambezi at the time enjoyed an easy-going relationship. Silveira writes of some Portuguese as being “corrupted by the infernal sect of Mohamed and even mixed with the pestilential Jews.” Silveira saw Muslims and Islam as enemies of his faith and his country. Once converted to Christianity the ruler would favour the Portuguese traders and expel or reduce the number of Muslims permitted in his territory.

At Sofala and Quelimane, Sena and Tete the Portuguese had the numbers to control the trade network, but inland in the sixteenth century the Swahili merchants outnumbered the Portuguese and dominated the gold trading network. However, with the Mwene and his councillors converted to Christianity then the tables would be turned on the Muslims and Mudenge describes Silveira in this sense as “a one-man army.”

However, it was not only the Swahili Arab merchants who felt threatened by Silveira. True to form Silveira had probably also alienated the traditional spiritual leaders of the Shona – Mhondoro and Ngangas, who would have been described as frauds and agents of the Devil by him. Equally some of the officials at court, the mbokorume, who had refused to be baptised, would be feeling threatened by the influence Silveira held over Chisamharu.

As we know, Silveira was martyred on the night of 15 March 1561. The killers rushed his hut once he was asleep and killed him in the traditional way a muroyi or sorcerer was killed, and his body thrown into the Musengezi river.

The Mutapa state at the time of the 1571 Portuguese military expedition up the Zambesi river

Father Monclaro accompanied Francisco Barreto on his military expedition leaving Lisbon in April 1569 and his report supplies all of the detail.[lxxii] A detailed account is included in the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The ‘unjust’ death of Father Goncalo da Silveira “whom the Monomotapa caused to be executed, being thereto persuaded and bribed by the Moors of those parts” was the professed reason for the military expedition, although the real reason were the “favourable reports of the abundant riches of the realms of Monomotapa.” The title bestowed on Barreto was Conqueror of the Mines. Father Monclaros’ opinion of the Swahili Arabs is made very clear: “There are some half-caste Moors among them, and the whole of the coast is infested by this infernal race.”

The expedition was diverted on a failed quest to conquer the Comoros Islands and only in November 1572 did they leave Mozambique Island for the Zambesi (Cuama) river reaching Sena where there was a small Portuguese garrison at Fort St. Marcel. “When we arrived there the land began at once to yield what it has, namely much sickness. During the time we remained there, which was nearly a year, more than a hundred persons died, and this before we advanced into the country; and the greater number of the people fell sick. Ruy Nunes Barreto [the brother of Francisco Barreto] fell ill of poison, which was given him by the Moors, of which he died, for it is their custom to administer it, and thus to continue secretly killing our people.”

The Swahili Arabs are suspected of poisoning the Portuguese at Sena and are killed

“…When we came to Sena there were on this river in different places about twenty turbaned Moors, men of position and rich, who traded with our people at the station of Sena, where the vessel came. This was a small town of straw huts, in a thicket along the river, and here the Portuguese come to trade with the natives of the country and the Moors…”

Many of the cattle and horses that arrived died shortly after. The Swahili Arabs are accused of poisoning them: “…At this time the horses arrived from India… they bribed the Moorish grooms who had charge of them to admit some Moors to give them poison in the mornings, which they agreed to, and the bribe was about ten cruzados…”

“…But at last, when he became aware of their treachery, Francisco Barreto immediately sent his captains and their men to arrest the Moors, who lived in houses apart from the town and on the other side of the river, at a distance of one or two leagues, which the soldiers did very willingly, for besides being revenged on the Moors, most of the gold which they had fell to their share, of which more than fifteen thousand miticals went to the king…

…They arrested seventeen of the principal men, among whom was the sheik and one of the plotters of the death of Father Dom Goncalo. Those were condemned and put to death by strange inventions. Some were impaled alive; some were tied to the tops of trees, forcibly brought together, and then set free, by which means they were torn asunder; others were opened up the back with hatchets; some were killed by mortars, in order to strike terror into the natives; and others were delivered to the soldiers, who wreaked their wrath upon them with arquebusses.”

Probably the real culprit was lantana camara, a noxious weed commonly found in Southern Africa. The toxic property in lantana camara is a triterpenoid, which is extremely toxic to livestock and humans.

The Mongas (Samungazi) are beaten with superior weapons, but other factors make the Portuguese withdraw to Sena

The Portuguese travelled upriver, probably as far as the Mazoe river where they fought, and their reports say, inflicted heavy casualties on the Mongas. However, they suffered so many sick from malaria and dysentery and their supply lines were so stretched and so little food available locally, they were forced to retreat back to Sena.

The Portuguese abandoned their goal of reaching the Mutapa state territory but send ambassadors and receive his ambassadors.

Monclaro writes:…”Francisco Barreto sent an embassy and rich presents to the Monomotapa by a Portuguese inhabitant[lxxiii] of Sena, who had already been at his court, which they call Zimbaoe, distant two hundred and fifty leagues from Sena, where are the mines of Masapa from which they often come to trade in Sena. The ambassador set out, and died on the way, being drowned in the river in a canoe. The message sent by him was that we had arrived, and that the governor wished to treat with his highness of matters of importance and of great advantage to himself and all his people, on behalf of the most great, high, and mighty Dom Sebastião, king of Portugal and of the sea, and of India, his master, and to that end he sent to him to treat of peace and friendship, and that the men he had with him were to clear the briars from the roads and open them for the commerce of our people with his lands…”

How we received the Ambassador of the Monomotapa.

The Monomotapa’s ambassador arrived, with two hundred followers and twelve of the Monomotapa’s officers including his general and captain of the gates of the kingdom.

“…The embassy declared that the Monomotapa wished to be a friend of the king of Portugal and desired nothing else but that the briars should be cleared from the road, and that he would rejoice to have trade and commerce with us. Francisco Barreto mentioned the three essential points of his instructions. First that the Moors should be expelled from the country. Secondly that he should receive the fathers and keep the faith. Thirdly that he should give [to the king of Portugal] many of the gold-mines which were in his kingdom…”

Sickness forces the Portuguese to withdraw

Francisco Barreto went to Mozambique Island and on his return to Sena: “…found some soldiers on the bank of the river, about fifty in all, with the four banners, but no captains or officers, and they themselves in such a state that they could hardly stand. Passing by the hospital we saw the sick seated in the huts, looking more like dead men than living beings, but rejoiced at our coming.”

After two weeks back at Sena, Barreto himself fell sick and died and was buried in the Chapel of St. Marcel on 9 July 1593 and succeeded by Vasco Fernandes as governor. Of the 650 men who had started with Barreto, only 180 still remained alive at Sena, and after leaving a small garrison at Fort St. Marcal, the remainder left for Mozambique Island.

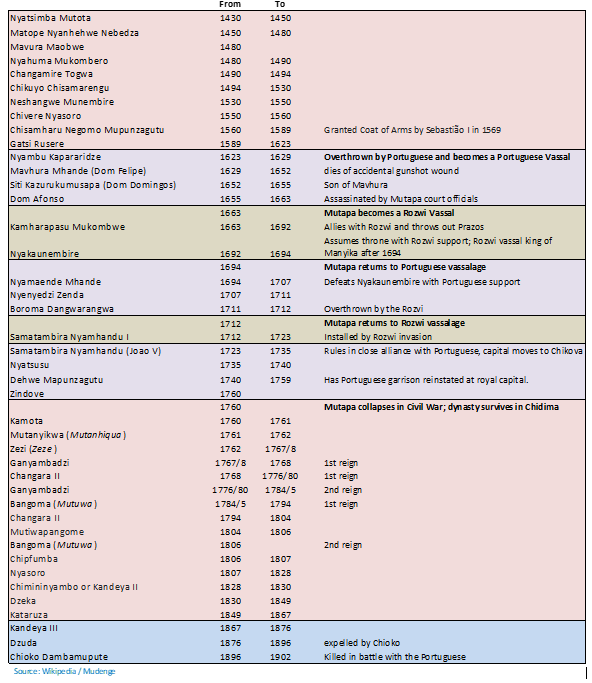

Rulers of the Mutapa state

The Mutapa State

Some important conclusions can be drawn from the historical record:

- Chisamharu Negomo was the acknowledged Mwene of the Mutapa state in 1561 although his mother was assisting him as regent and his hold on power was still tenuous

- The Mutapa capital was at his kraal on the upper Musengezi river and thus still in the Dande region of the Zambesi river Valley

- The Portuguese officially acknowledge the existence of the Mutapa state by 1569. They send ambassadors to the Mwenemutapa and receive his ambassadors at Sena.

- Wikipedia states: “The empire had reached its full extent by the year 1480 a mere 50 years following its creation.” This seems unlikely given the Portuguese accounts concerning the sixteen year old Chisamharu Negomo still living on the upper Musengezi river and the killing of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. in 1561.

- The Portuguese histories written by João de Barros and Father João dos Santos were based largely upon Swahili traders accounts – there had been few Portuguese explorers such as Antonio Fernandes - therefore they are mostly second -hand accounts. This article used the account written by Father Monclaros who actually travelled on Francisco Barreto’s military expedition, but on this occasion the Portuguese never travelled beyond the lower reaches of the Mazoe river, so much of the descriptions of the Mutapa state itself are from word of mouth accounts and were not verified.

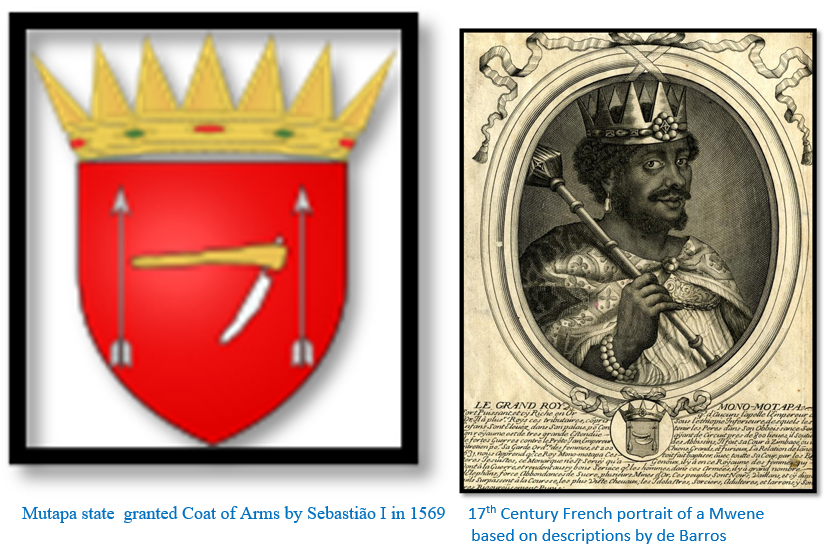

- The Portuguese Crown gave official recognition of the Mutapa state when Sebastião I granted a Coat of Arms to Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu in 1569

- It was in the Portuguese interest to exaggerate and magnify the Mwene’s hold over the territory of the Mutapa State. First they only had one person to negotiate treaties with in a region which was extremely remote and difficult to penetrate for Europeans. Secondly the Mutapa state’s reputation for the richness of its mines rather grew with the telling and it was in the interests of those who reported to the Portuguese Crown, particularly the Jesuits, to exaggerate its wealth.

(8) The idea that the Mutapa state constituted a formally administered ‘empire’, however, was exaggerated in European minds and is now rather discredited, and the maximum territorial area of the Mutapa state has been the subject of disagreement (Randles 1975; Beach 1980; Mudenge 1988) Unquestionably the Mutapa state did wield influence over a considerable area of present-day northern Zimbabwe and at times into present-day Mozambique through its vassal states of Inhamior (Barwe) Quiteve (Kiteve) Manyika, Sabia (or Sedanda) and Chikanga.

Hence the Coats of Arms and royal portraits to ensure that the Mutapa state was accorded the same royal privileges as any other European royal house.

The baptism of King Siti of Mutapa by workshop of Tomasz Muszyński, 1683, Dominican Monastery in Lublin. The baptism of Siti Kazurukamusapa was celebrated by João de Mello on 4 August 1652, the feast day of St Dominic but in a very different setting from that portrayed by the artist.

(9) Mudenge writes that the Mutapa state probably originates in small Karanga groups that came from Great Zimbabwe bring their culture of sacred leader with them and slowly integrating with the people of the Dande region. This theory is reinforced by Pikirayi who believes a core of Karanga integrated with the Tonga and Mbara people from the Dande and across the Zambesi at Ingombe Ilede who were less cohesive.

Over time a coalition of different peoples became united and as the wealth of their herds grew began to be administered in much the same way as that of the Great Zimbabwe state, i.e. that a small ruling elite ruled over a much larger number of commoners.

(10) The decorative walling and symbolism so prominently displayed at Great Zimbabwe and at other capitals such as Khami, Danangombe, Zinjanja and Naletale is much less obvious in the Mutapa state, but the evidence of sacred leadership and that the rulers were: “secluded from the commoners, living in privacy and isolation behind palace walls” is evident – although on a smaller scale, at Zvongombe, Nhunguza and Ruanda where Q-type walling also exists.

References

D. P. Abraham. The early political history of the kingdom of Mwene Mutapa (850-1589). In Historians in Tropical Africa: proceedings of the Leverhulme Intercollegiate Conference,

September 1960, Stakes, E.(ed.), 61--92. Salisbury: University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

Zimbabwe Culture before Mapungubwe: New Evidence from Mapela Hill, South-Western Zimbabwe. Shadreck Chirikure, Munyaradzi Manyanga, A. Mark Pollard, Foreman Bandama, Godfrey Mahachi, Innocent Pikirayi. 31 October 2014. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0111224

J. Mutero Chirenje. Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560 – 1572: the interplay between evangelism and trade. The International Journal of African Historical Studies

Vol. 6, No. 1 (1973), pp. 36-48

P.S. Garlake. Excavations at the Nhunguza and Ruanga Ruins in Northern Mashonaland. The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol. 27, No. 107/108 (Dec 1972), pp. 107-142

Mike Main and Tom Huffman. Palaces of Stone – Uncovering ancient southern African Kingdoms. Struik Travel and Heritage of Penguin Random House South Africa, 2021

Abigail Moffett and Shadreck Chirikure. December 2016. Exotica in Context: Reconfiguring Prestige, Power and Wealth in the Southern African Iron Age. Journal of World History 29(4):337-382: DOI:10.1007/s10963-016-9099-7

National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (www.nmmz.co.zw)