Home >

Mashonaland Central >

The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland

The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland

Introduction

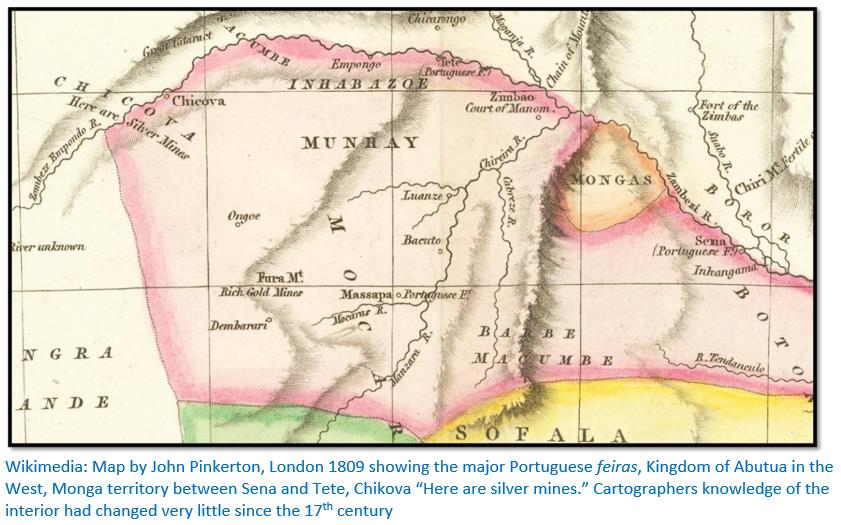

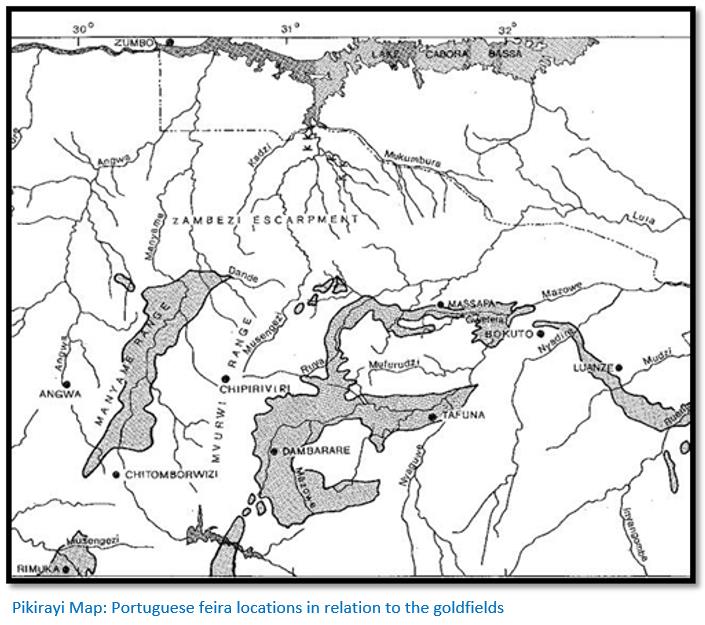

This article does not attempt to describe in any detail all the feiras that were established in present-day Zimbabwe. The bigger and better known feiras have separate articles on this website under the provinces according to their location and these will be referred to. Instead it attempts to give a broad outline of the extent of Portuguese settlements in the 16 – 17th centuries and a general description. There are a number of excellent sources of material including good photographs by Chris Dunbar in his articles on the website www.colonialvoyage.com – this website has a very comprehensive selection of articles on the Portuguese colonial period around the world. Henk Ellert’s Rivers of Gold (if you can get a copy) and Stan Mudenge’s A Political History of Munhumutapa c1400-1902 - both are excellent sources of information. Peter Garlake excavated at Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) and Maramuca (Rimuka) and Innocent Pikirayi and the Archaeological Unit of the University of Zimbabwe has carried out surveys and excavations at Massapa with a number of interesting and informative articles by Pikirayi and his highly regarded book The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States.

External trade prior to the Portuguese

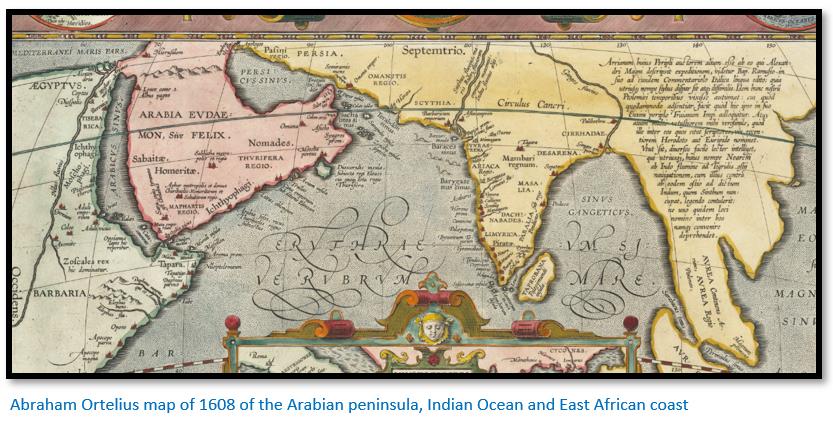

The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea is an eyewitness account of ancient travel in India and Africa through the Red Sea written by an unknown Greek-speaking Egyptian author in the 1st century. In this detailed account, the routes are described with their ports and descriptions of local people and their major imports and exports. The ports and goods being traded are also described by Ptolemy in his Geography in the 2nd century. Born in Baghdad, Abu al-Husayn al-Mas'udi travelled extensively in the East and then moved westward in 916 or 917, sailing to Oman and thence to East Africa. On the coastline of what is now Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique, Persian, and Arab merchants had been conducting trade for many years and muruj al-dhahab (Meadows of Gold) is among the first written accounts of sub-Saharan Africa.

Swahili merchants travelled inland from Sofala and also directly up the Zambesi river from about the tenth century onward. Arab writers of the 10th and 11th Centuries, which deal with the export of gold and ivory from Sofala, clearly demonstrate the existence of commerce between traders from the Manica area and elsewhere in the interior with the Swahili traders at the Coast. However it is difficult to assess how many were engaged in the gold trade, but clearly some were permanently resident at the principal gold fairs and at the Mutapa’s court and had traded for gold and ivory for at least six centuries before the arrival of the Portuguese.

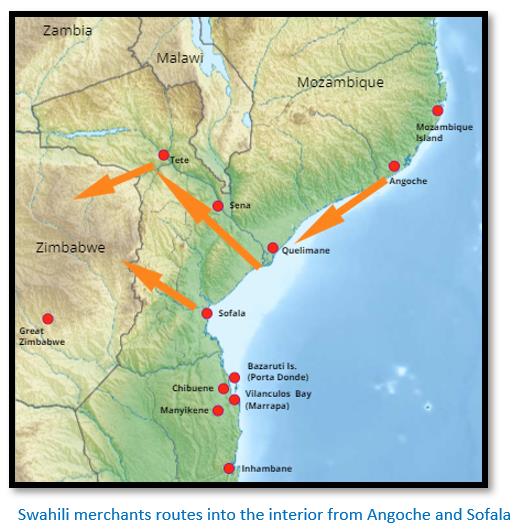

Swahili merchants accessed the interior from two routes:

(1) From Angoche traders sailed via Quelimane to the Zambesi river and then walked the Luenya and Mazowe rivers to reach Mokaranga or continued onto Ingombe Ilede or later in the 17th century at the Hwangwa river fiera. The Swahili traders at Angoche had split from the Sultanate of Kilwa to establish a new Sultanate that was independent of Kilwa

(2) From Sofala they travelled up the Buzi river and travelled into and through Manyika. These Swahili traders remained loyal to the Sultanate of Kilwa.

In the larger villages Swahili and African traders set up bazaars (markets) where they bartered with each other. Itinerant Swahili traders would have travelled to inland villages selling their trade goods – mostly beads and cloth for gold and ivory. Others appointed local agents, vashambadzi, to make the journeys into the interior. De Barros shows that he knows the Swahili traders visited the villages as he writes: “the Moors who carry on the trade among them make use of artifice to arouse their cupidity, for they cover them and their wives with clothes, beads, and trinkets, with which they are delighted, and after they have thus pleased them, they give them all these things on credit, telling him to go and dig for gold and if they return in a certain time, they can pay for all.”[i]

Mudenge goes on to say that the Mutapa state “must have given the peace and security in which the gold and ivory trade could be carried out… in return for security provided by [Mutapa] Mutota these traders could use their trade networks to put in a word or two about the new rising star from the north east of [present-day] Zimbabwe. Through presents, tolls and taxes, they increased his coffers. To the Angoche-based Moslems, the rise of the Mutapa state along the Zambezi must have been a positive development to be nurtured in their struggle with the Sofala-based Kilwa - affiliated Moslems. In this way, external trade and its existing connexions may have assisted in the expansion of the Mutapa empire.”[ii]

Why was Portuguese exploration of the interior important?

When the Portuguese first permanently resided at Sofala in 1505 they expected rich pickings. The first clerk of Sofala fortress, Diogo de Alcacova in 1506 reported that at its peak over a million meticais[iii] of gold was traded by the Swahili traders at Sofala annually. But their hopes were quickly dashed as the trading results in 1506 showed just 8,176 meticais of gold and much of it came from Portuguese raids on the Swahili trading posts. For the period 1506 to 1518 in the five years for which records survive, a total of only 54,887 meticais of gold are recorded.

Within the first two years of establishing Sofala the Portuguese realised that the gold trade had shifted north, and the Swahili traders were now exporting their gold and ivory down the Cuama (Zambezi) river and using Angoche as their trading post and not the Sofala trade routes. Often however their reports stated that tribal wars were interrupting the trade. They needed to explore and gather information on the gold trade of the interior themselves and break free of relying on the few Swahili compliant traders at Sofala. António de Saldanha during his three year term from 1509 to 1512 as captain-major of Sofala and Mozambique Island began to use the degredado’s at Sofala fortress as explorers.

The Portuguese needed to know where the gold was sourced, who controlled its collection and trade, to establish where the king of Mutapa state lived, the routes used for transporting gold and ivory to the coast, if food supplies were available and the goods that were used for its purchase.

However from 1506 to 1560 the Portuguese on the coast relied almost entirely upon second-hand evidence brought by African or local Muslim traders from the interior[iv]

The exception was Antonio Fernandes[v] who we see effectively paved the way for further Portuguese exploration of the interior and development of the feiras by travelling successfully through the lands of Quiteve, Mokaranga and the eastern edge of Abutua in his two journeys by foot in 1511-12 and a third in 1513-14. However his journeys to the Mutapa state provided little information but the names of the Chiefs, the availability of gold and supplies and those contacts that the Portuguese needed in order to take over the gold trade from the Swahili traders.

The Portuguese disrupt the Swahili trade routes, but do not stop their gold trade

Father Monclaro writes that Gaspar de Viega[vi] who uncovered the Swahili merchants’ routes up the Zambesi river during the reign of Mutapa Neshangwe Munembire (1530 – 1550) The Portuguese made it policy to displace the Angoche-based Swahili traders from this route. Between the 1530’s and 1540’s[vii] they replaced the Moslem bazaars along the Zambesi with their own markets and established settlements at Quelimane, Sena and Tete in order to have better access to the northern Mashonaland Plateau and the Mutapa state.

Portuguese feiras in the 16th – 17th centuries from historical records

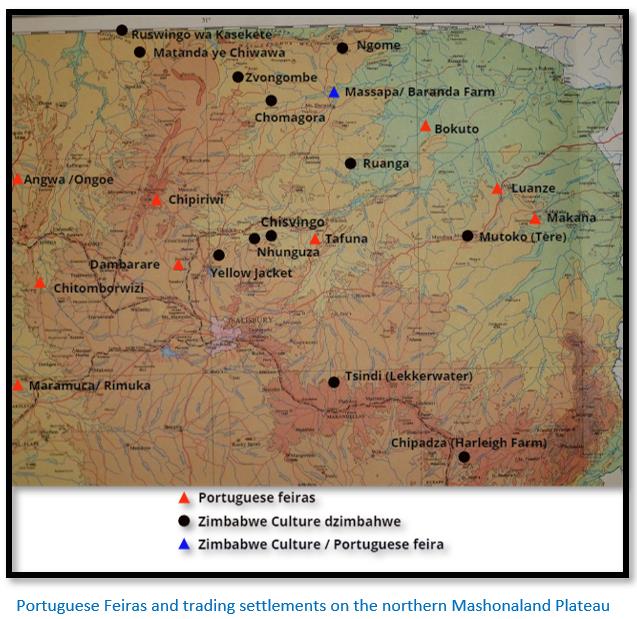

Ellert states the feiras: “were pivotal in the spread of Portuguese influence in eastern and central Mashonaland during the 16th and 17th centuries.”[viii] He quotes from Diogo do Couto who accompanied the disastrous 1570 Francisco Barreto military expedition.[ix] “They are three in number [Luanze, Bocuto and Massapa] the trading fairs where the Portuguese go trading their cloth and beads for gold.”

By 1667 Manuel Barreto would write: “In Mokaranga, as the empire of Monomotapa is called, there are several minor captains, such as the captains of Dambarare, Ongoe, Luanzi and Chipiriviri, with their chief captain, who resides at zimbaoe or at the court of the emperor, with a garrison.”

At each feira a Portuguese trader was put in charge by the Captain at Mozambique Island. He was given the honorary title of captain-major, but was unpaid, his chief return being that he had the privilege of selling his trade goods before the others. But he did exercise authority over the other traders in the name of the Captain at Mozambique Island. However only the ‘Captain of the Gates’ at Massapa feira was an officer of the Mutapas.

The ‘Captain of the Gates’ was in charge of all the Portuguese in the Mutapa state and he was the Mutapa’s adviser on any Portuguese affairs. His most important role was that: “he acts here also as factor of Monomotapa to receive all the duties paid to him by the merchants, both Christians and Moors, which are one piece of cloth in every twenty brought into these lands to be sold.”[x]

Travelling to the Northern Mashonaland Plateau in the 17th century

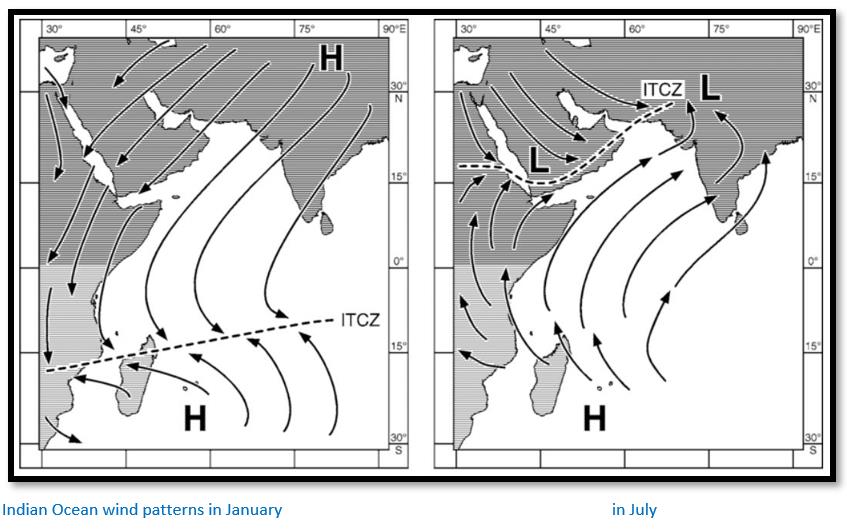

Henk Ellert in his book Rivers of Gold tells the story of how Father António Gomes[xi] a Jesuit priest, caught a ship sailing from Goa, India – it was late to catch the prevailing winds blowing from the Indian sub-continent to Africa – and after a voyage lasting months, due to the unfavourable winds and bad weather, reached Madagascar before arriving at Mozambique Island, then a Portuguese possession.

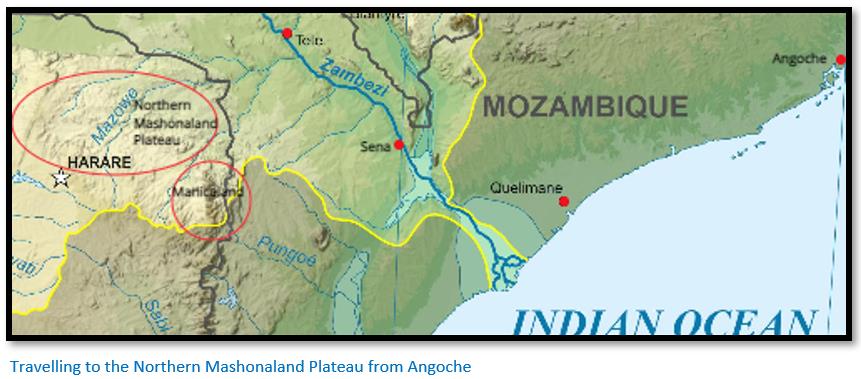

After a short stay at Mozambique he caught a smaller coastal boat, probably a Swahili dhow, south to Angoche and then Quelimane. From here he travelled overland to Luabo, a small settlement on the east bank of the Zambesi river, approximately 50 km from its outlet to the Indian Ocean. From Luabo the Zambesi river is navigable by almadias,[xii] river craft with a sail, to his next destination at Sena.

In the late 1620’s Sena was the Portuguese administrative base for the Rivers of Cuama.[xiii] It had a fort – Fort St. Marcel, cathedral, hospital, Dominican and Jesuit churches and the residences of the traders and their families who traded with the interior.

From Sena the Zambesi river is navigable by river craft for 150 km as far as the Lupata gorge which has to be portaged around and is then navigable again for 25 km to Massangano.

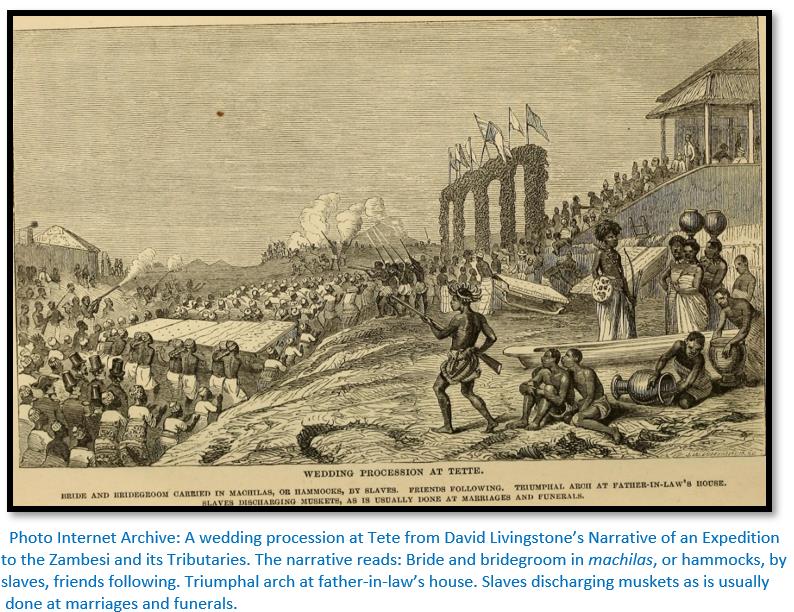

At Massangano was a small settlement or aringa (a Portuguese term for a stockade made of wooden stakes that serves as a defensive wall) on the west bank of the Zambesi river. Massangano is 5 km south of the confluence of the Mazowe-Luenha[xiv] rivers, the normal transit route into the goldfields of the northern Mashonaland Plateau, although most traders would probably have initially continued onto Tete, another 40 km the only substantial Portuguese settlement in these parts.

Here if they were Tete-based traders they would probably have families with local women and their children. These children called mwamamuzingo, often accompanied their father’s trading caravans into the interior escorted by vashambadzi – African itinerant traders or slaves acting as agents for the Portuguese merchants.[xv]

Couto in Da Asia states the trading caravan might comprise two to five hundred individuals and the journey into the interior inevitably began at Massangano, just below the Mazowe-Luenya confluence with the Zambesi river. The Massangano aringa, was occupied at least since 1667 when Manuel Barreto noted a Portuguese trader, Manuel Pires de Pinho, had a fortified settlement here. David Livingstone described it when his Zambesi expedition passed by in 1856. He described it “as a stockade menacing the whole commerce of the rivers in a situation where the guns of a vessel would have full play on it, but it is a formidable affair for those who have only muskets.”[xvi] This aringa was occupied continuously until the late 1880’s when the last of the prazo-holders[xvii] at this place, Bonga was defeated, and the Massangano aringa finally destroyed.

Stan Mudenge[xviii] states each individual in the caravan would carry a bundle of cloth wrapped in a wild palm-tree mat with one mutoro or two corjas (40 pieces of cloth) and the journey now continued along footpaths on the banks of the Luenya for 75 km until its confluence with the Mazowe river was reached and the route took a more south easterly direction. Not only did these rivers provide a route, but during the winter (May – October) when there is little rain, they still provided water from pools. Father Filipe de Assumpção estimated the journey from Tete to the feira at Massapa took between 12 – 14 days with those taking part walking from the early hours of the morning until midday when it became too hot and a halt was called, food cooked and camp made for the night.

David Beach[xix] asserts that Hondosaka was between the lower Ruya and Mazowe rivers and its ruler was the original ‘Captain of the Gates’ for the Mutapa state. All foreigners were required to pass through Hondosaka before entering Mokaranga. But in the late 16th century this changed and the post was nominated by the Governor of Mozambique Island from amongst the traders resident in the Mutapa state.

Walking was arduous, the Mopane tree is characteristic in the hot, dry, low-lying areas, 200 to 1,150 metres (660 to 3,770 ft) of much of this region and favours shallow and not well-drained alluvial soils where the temperatures can reach 40°C. In the wet season (November – March) the humidity was oppressive, at all times their were biting insects and the ever-constant threat of malaria. Wild animals, elephant and lion, presented a constant danger.

Henk Ellert quotes Diogo do Couto in his Décadas (a history of the Portuguese in India, Asia, and southeast Africa) continued by him after Joao de Barros describing the trading caravans walking from Tete to the feiras of the interior.[xx] “There are some merchants who have a hundred or even two hundred captive blacks of their own whom they order to go trading for them…each of these blacks carries on his head a small, oblong, well-tied bundle, which they call mutoro, which bears two corjas, that is forty blue cloths, cheap material about seven or eight corvados (four to five metres in length) and a little over one corvado in breadth… striped clothes…greatly prized by the blacks and they part them into pieces, in which they wrap themselves, this being the finest apparel in the world for them. The traders also carry small beads made of clay, some green, blue and yellow, these making up the necklaces that the blacks wear around their necks.”[xxi]

The dates of the arrival of each caravan would be agreed in advance so that local people with gold and ivory would know when to come and barter and was commonly in the early dry season i.e. May to June, after the rains and when the activity directed at alluvial and reef mining was at its height.

Later in the 18th and 19th centuries Tete traders also followed the Zambesi westwards to Zumbo at the confluence of the Luangwa river. This settlement traded with the Rozvi from Abutua, the Dande and Chidima regions.

Typical trade goods sold at a feira

Ellert lists the items stocked by Joao Juliao ds Silva for the Bandire feira including:

zuartes blue Nankin cloth

dotins white cotton cloth

chales rough calico

capotim two lengths of cloth

missangas beads

chadares cloth sheets

aguardente a fiery alcoholic spirit

cabaia wide-sleeved tunic of red fabric

lencois handkerchiefs from Diu, red or striped

roupas clothes

calaim oriental tin

In return for the above the most lucrative trade was in gold and ivory. The villagers would gather when they heard the Portuguese traders or their vashambadzi were arriving bringing with them porcupine quills filled with gold-dust and sealed with bees-wax.

Portuguese method of trading

Most of the Portuguese traders waited for the Mutapa’s subjects to bring their gold to their feiras or trading settlements where they had their store houses (churro) and stock-in-trade and where they would barter a deal. Others preferred to send out vashambadzi (agents) from Sena or Tete in April to June when alluvial and reef mining was at its peak and these bartered trade goods for gold at local population centres. Dos Santos wrote that the Portuguese traders at Sena and Tete: “have houses called churros where they store their merchandise and from which they sell it and send it to be sold throughout all the country.”[xxii]

Tolls and tariffs were paid for the privilege of trading

Payment of tolls and tariffs were paid by traders not just to the Mutapa at Massapa, but by traders to every chief through whose land they travelled. Some traders entered Mokaranga through Manyika without going through Massapa, but for security reasons most Portuguese traders did travel through Massapa.

Any Portuguese who visited the Mutapa zimbaoe was expected to present a gift. João de Barros states: “no person speaks to the king or to his wife without offering a present. The Portuguese take him cloth, the kaffirs a cow or goat, or some pieces of cloth. And when they are so poor that they have nothing to offer him, they take him a sack of earth in acknowledgement of their vassalage, or a bundle of straw to thatch his houses.”

The Mutapas levied a tax called the curva or kuruva[xxiii]

This tax was pre-Portuguese and paid by Swahili traders from the earliest days of the Mutapa state in return for being allowed to trade for gold. The practice came to be continued by the Portuguese traders in the 16th – 17th Century even after they had ousted the Moslems from Mokaranga. The curva was not paid by individual traders, but by the new Captain at Mozambique Island who on their appointment every three years sent 3,000 cruzados in cloth and beads as curva to the Mutapa, although the amounts do vary between the various historical accounts.

Mudenge writes that before 1771 an annual curva was paid that consisted of 15½ corjas (310 pieces of cloth weighing 182½ kg as well as, every three years, a gift of two sombreros, one chair, a cushion, a carpet and one jug and basin. From 1771, the annual cloth payment was increased to 20 corjas weighing 235 kg.[xxiv] Individual traders paid their own tariffs on top of the curva.

If the curva was not paid, there were consequences. Dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental writes the Mutapa: “commands an empata [mupeto] of all the merchandise throughout his lands and seizes all that is found, as this is what they call an empata and in this way he liberally pays himself what is due and takes satisfaction for the affront he has received…in these empata which he orders he confiscates many thousands of cruzados from the merchants without any restitution being made of them.”

As Mudenge writes, this was no idle threat and at least two empata are recorded in the 17th century.

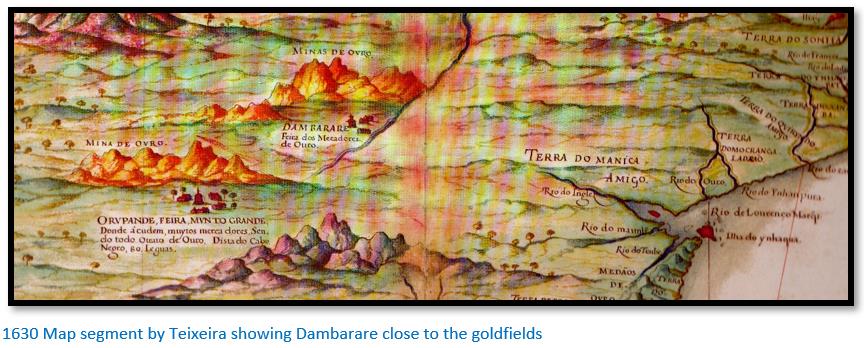

The known Portuguese Feiras

In the 16th and early 17th century Massapa was the most important of the feiras on the northern Mashonaland Plateau of Mokaranga, but in the second half of the 17th century Dambarare became the most important centre for gold trading.

After 1695, following the Rozvi invasions under Changamire Dombo none of the feiras operated, except on a temporary basis as at Angwa (Ongoe) and in Manyika where they were closed between 1695 to about 1719 and then re-opened.

In 1769 after Mutapa Changara signed a treaty of friendship with the Portuguese that granted Portuguese traders and their vashambadzi freedom of movement in those areas under his control, he also agreed to the Portuguese trading in the goldfields around the old feiras such as Dambarare and to pay tribute. Because of a decline in the trade at Zumbo the Portuguese under Joao Moreira Perreira sent vashambadzi to explore the prospects of re-opening the old feiras. They found them all deserted because: “the plagues, wars and famine have wiped out their inhabitants” and even where they found small populations, the people: “lived almost the whole year on fruits, roots, honey and meat of wild animals.” The cost of re-establishing the old feiras of Mokaranga was considered prohibitive and when trade at Zumbo picked up again, the project was forgotten.[xxv]

Common features

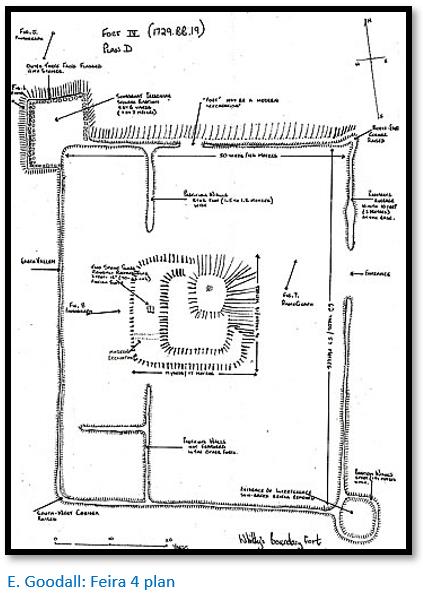

Almost all the feiras excavated by Garlake (Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) Maramuca (Rimuka) and the trading settlements examined at Angwa (Ongoe) by Goodall exhibit the same construction features of a central mound that housed the store rooms / living rooms surrounded by a rectangular earth embankment.

Bastions have been added to the corners at the Angwa settlements and at the middle of the enclosure walls at Luanze and Maramuca. Clearly these were added after the original buildings had been constructed. The Portuguese records say that the feiras were reinforced in the 1680’s in anticipation of an attack by the Rozvi under Changamire Dombo – that attack is recorded in 1693 at Dambarare.

The location and layouts of the feiras show they were never laid-out with defence in mind as they are sited on low, level and easily accessible ground overlooked by hills and make no use of any natural defensive features in the vicinity, while the very long enclosure walls would have required a large garrison for a proper defence. The embankment walls are designed to provide some security, but are not adequate for defence, and any ditches were too shallow other than to provide drainage. Pedro Barretto de Rezende[xxvi] described Luanze in 1634: “The fort of Luanze before mentioned, where the Portuguese hold a market is in the lands of Mocaranga, forty leagues from Tete. It is only a palisade of stakes, filled up inside with earth, allowing those within to fight under cover. The stakes are of such a nature that when they have been two or three months in the ground they take root and become trees which last many years.”

The siting of the earthworks at Dambarare and Luanze would not have provided any complimentary support and were clearly designed for trading purposes, which the merchants did separately and independently. Construction at all sites was similar with sun-dried bricks being used, so-called ‘Kimberley bricks’ made from local clays and cemented with local mortar.

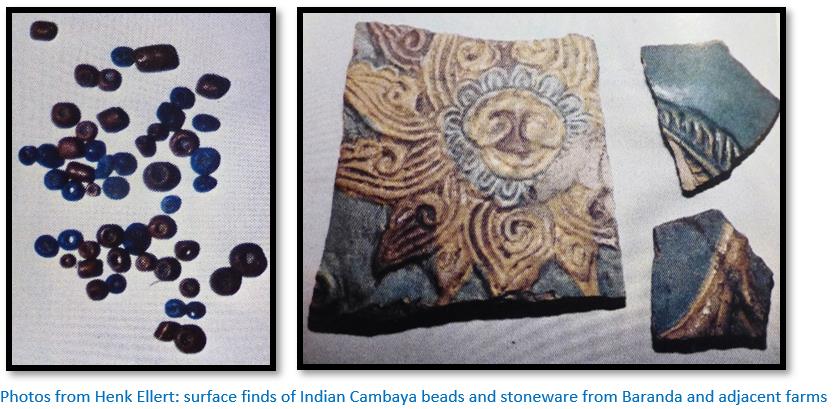

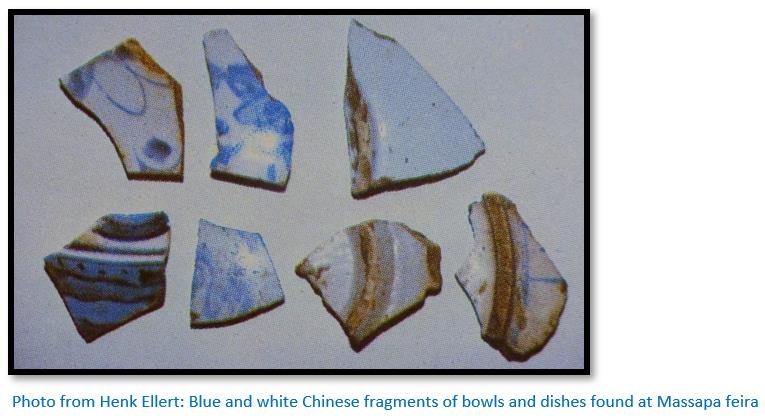

Evidence of trade items was found at all the sites in the form of imported ceramics and shell and glass beads, the principle items of trade with imported cloth, although obviously the last would not have survived. These provide firm evidence of dating from the 17th century as does contemporary documentary evidence by many Portuguese administrators and historians. Father Joao dos Santos who was present in 1587, writes in 1609[xxvii] that at the feiras of Massapa, Luanze and Manzove[xxviii]: “the residents of Sena and Tete have houses called churros, where they store their merchandise and from which they sell it and send it to be sold throughout the country.”

All of the feiras were sited within or at the edge of known local gold fields to facilitate trade in that commodity. Pre-European alluvial and mining gold production often took place in the vicinity as at the Angwa river and Maramuca where Garlake reports there was ‘ancient workings’ within one hundred metres.

ANGWA (ONGOE)

See article under Mashonaland West on this website

Six feiras are mentioned in the literature of which Elizabeth Goodall in 1945 visited and drew plans for four that were on the west (Feira 1 and 2) and east (Feira 3 and 4) banks of the Angwa river.[xxix] As far as I know, the remaining two reported feiras have never been visited by archaeologists.

The Angwa river area has been the subject of extensive alluvial mining both by artisanal miners and by Chinese mining companies in recent years using diggers and trucks. It is quite likely that all the four feiras visited by Mrs Goodall have been subjected to large-scale fossicking that has caused serious environmental damage.

All four feiras are characterised by a central mound which appear to be the store rooms and living quarters of the feiras that were probably surrounded by a covered verandah and were constructed of ‘Kimberley bricks’ sun-dried and made from locally obtained clay. The Angwa (Ongoe) feiras, Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) and Maramuca (Rimuka) buildings were constructed in a very similar way. They are each surrounded by a rectangular enclosure with a low earth bank that has probably reduced with time.

Mrs Quarrie told Mrs Goodall that she had fossicked at feira 2 in the 1920’s and reported recovering a lot of blue and white imported ceramics, now lost.

Feira 3 was the largest and most impressive site that Mrs Goodall inspected in 1945. The inner measurements of the rectangular enclosure are approximately 100 yards long (91 metres) by 82 yards wide (75 metres) Outside the earth wall 3 – 5 feet high (1 – 1.5 metres) was a ditch.

In the south – east corner is a circular sunken bastion with a diameter of 9 - 10 feet (2.7 to 3 metres)

Mrs Goodall found a shard of glazed earthenware, part of the round bottom of a large jar. Her guide, Mr Martin, had found a similar piece many years before.

Feira 4 is similar in layout, with an irregular bastion in the north west corner measuring 8 x 8 yards (7 x 7 metres) with three of the outer faces flagged with stones. A similar bastion at the south east corner was mostly destroyed.

There appears to be no evidence in Portuguese historical documents of when the Angwa feiras were established, but in 1684 João de Sigueira was sent by Caetano de Melo de Castro[xxx] to reinforce the feiras on the Angwa river in anticipation of an attack by the Rozvi under Changamire Dombo and the bastions were most probably added to feiras 2, 3 and 4 at this time.

Most of the few dozen Portuguese traders and their families left for the safety of Tete leaving the so-called Canarins at the feiras. The Canarins were Konkani people from Goa and were recruited because they were Christian Indians. Ellert states that they built good trade relations with the Africans and some had experience at gold mining from India, so that gold production actually increased at Angwa and Chitomborwizi.[xxxi]

There was no evidence that the Angwa feiras were destroyed by the Rozvi army of Changamire Dombo, so it is likely that the Portuguese fled when the rumours of the Rozvi defeat of the Portuguese at Maungwe reached them and the Canarins followed them when they heard that the combined Rozvi / Mutapa army had sacked Dambarare in 1693.

DAMBARARE

See article under Mashonaland Central on this website

For many years in terms of gold trading activity this feira was probably the most dominant on the northern Mashonaland Plateau, although Massapa because it was situated at the Mutapa’s zimbaoe was more politically important.

An outline of the four feiras and church are shown in the Dambarare article showing it was dispersed over a fairly large area – a common practice with Portuguese traders who wished for some privacy but wanted to be within visual contact of each other. What was most likely the fort on the banks of the Marodzi (or Murowodzi) river was flooded by the Jumbo Mine dam.

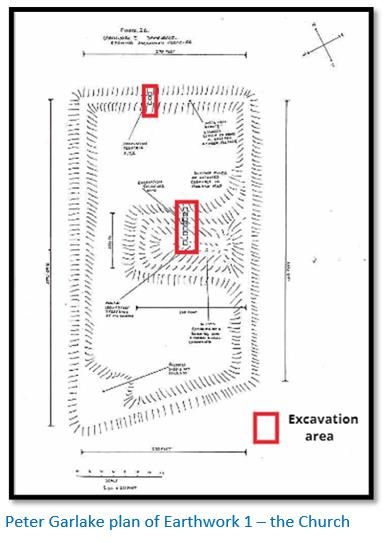

Peter Garlake excavated the church site[xxxii] at Dambarare in 1969 that revealed thirty-one burials alongside the walls and beneath the floors of the building. Ten men were buried within the church and some of their personal possessions and items of dress were preserved and these are described in the article.

The remainder of the burials were immediately outside the church, including three Portuguese men and eighteen women and children, some heavily adorned with copper and bronze bracelets and anklets. One had a girdle of shell and glass beads and hanging from this was a rosary of small carved ivory beads and attached to them, a tiny, heavily worn bronze medal.

Garlake[xxxiii] thought there was nothing intrinsically remarkable in these relics, their craftsmanship is ordinary and the medallions at least were clearly mass produced to stereo typed designs. The silver and gold adornments were of no higher quality and have a high copper content. Their interest lies only in their rarity and in the link they provide and the light they shed on the earliest European settlement of Zimbabwe.

The excavations revealed a first church had been constructed of red bricks and later a floor was laid over the red rubble layer and the graves and a second major building was erected using larger and thinner sun-dried bricks ‘Kimberley bricks’ that are mainly sandy in texture and of various colours: buff, grey, yellow and chocolate.

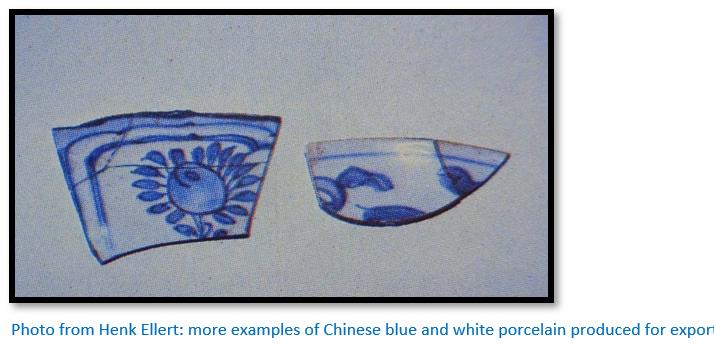

Both indigenous pottery and 3,182 sherds of imported ceramics, mostly Chinese Wanli period, were found by Mrs Goodall in 1944-45. Also over fifteen thousand shell and glass beads from the burials. Also copper or bronze bangles, bracelets, anklets or necklaces from the adult indigenous burials.

During the `670’s the amount of gold traded at Dambarare declined due to political instability on the northern Mashonaland Plateau, civil wars amongst competing Mutapa factions and natural disasters including locust swarms, drought and disease which led to a seriously reduced population. Local resentment at Portuguese interference in the Mutapa state grew and Francisco da Valle was appointed as Captain of Dambarare in June 1684 with specific instructions to strengthen the defences against attack. It appears that two small artillery pieces were delivered, but the defences were undoubtably weakened by the Portuguese traders and their mwanamuzungo (mixed marriage offspring) leaving for the safety of Tete.

There was no archaeological evidence of the damage caused by the Rozvi army of Changamire Dombo and his ally, the Mutapa Nyakaunembire in November 1693, when, as described by Antonio de Conceição, he killed the inhabitants before they could reach the safety of the fort, desecrated the church, disinterred some burials and had the priests flayed alive. Most of the Portuguese had already fled to Tete, but all the few remaining traders and their families and vashambadzi and Canarins (Konkani people from Goa who were recruited because they were Christian Indians) were killed.

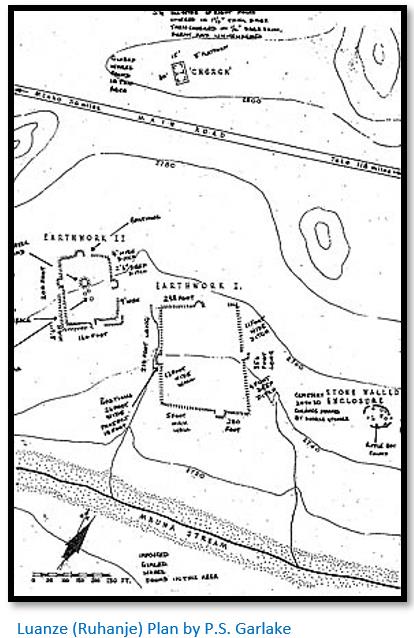

LUANZE (RUHANJE)

See article under Mashonaland East on this website

The location of Luanze was described by Diogo de Couto[xxxiv] c.1610: “There are three markets where the Portuguese go to trade for gold and sell their merchandise . . . the first is called Luanhé and it is about thirty five leagues from Tete to the south. It is between two rivers which when they unite are called Nausovo, and the said place is ten leagues from each of these rivers.”[xxxv]

Pedro Barreto de Rezende wrote in 1634: “The Fort of Luanze, where the Portuguese hold a market, is in the lands of Mocaranga, forty leagues from Tete.....this fort has a church, served by a Dominican friar who administrates the sacraments to the Christians who dwell there or pass through…The site of this fort inside is like a large terrace, being a hundred fathoms (brassas) in circumference, where the captain resides, who is elected by the captain of Mocambique, and with him the Portuguese and Christians who may be trading in these parts.”

At Mtoko there is a small, but useful museum built to house some of the artefacts un-earthed at the Luanze feira.

The main features at Luanze are the two rectangular earthwork enclosures and the church.

Earthwork 2 has the central mound also seen at the Angwa feiras where the storerooms and residences of the Portuguese were located. The same rectangular enclosures can be seen outlined by earth banks. There are also the remains of pole and dhaka buildings outside the enclosures.

The Church is sited on the northern side of the A2 national road. Not much is still visible, but lumps of dhaka with pole imprints can be seen.

A short distance east of the larger enclosure is a small cemetery with 25 graves marked with headstones and a little further on a stone walled enclosure that may have been constructed at a later date; both are marked on the above plan.

Garlake saw many similar characteristics between Luanze (Ruhanje) and Maramuca (Rimuka) and both sites yielded glazed Chinese wares of the seventeenth century and identical types of beads traded by the Portuguese.

The feira was located in 1964 when a prospector named N.J. Van Wyk found quantities of glass beads in the small stream below the earthworks and reported his finds to the Queen Victoria Museum. Garlake was then sent to investigate by the Historical Monuments Commission.

MARAMUCA (RIMUKA)

See article under Mashonaland East on this website

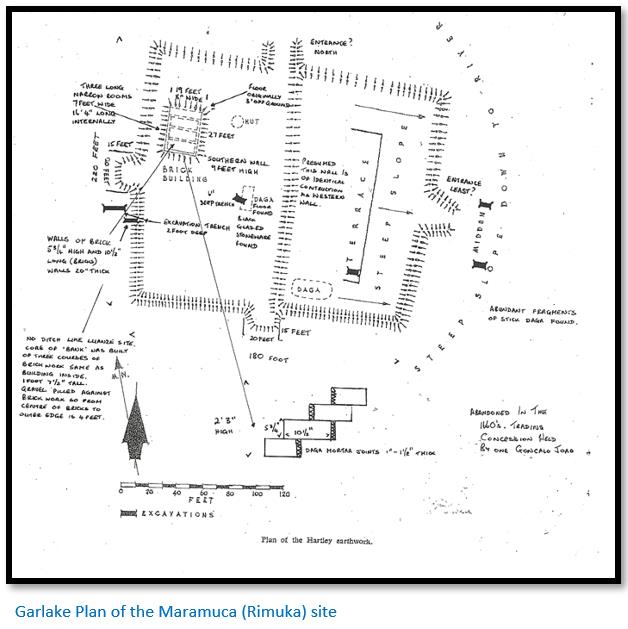

Manoel Barretto describes Maramuca in 1667 as: “Maramuca is the name of a great district of the kingdom of upper Mocaranga . . . This kingdom is the richest in gold known.” As can be seen from the map by Innocent Pirikayi above, Maramuca is well south and west of Chitomborwizi and in the land of Abutua under Rozvi control.

Maramuca is reached via Chegutu and then Chakari, the site of Dalny Mine, that had produced 2.44 million ounces (69.2 tonnes) of gold up to 2006. It is located on the summit of a small kopje on the west bank near an old bend on the Suri Suri River, the site has by now in all likelihood been destroyed by fossicking and illegal mining. Fortunately it was excavated by the extremely competent Peter Garlake before its destruction.[xxxvi]

In theory, like the sites on the Angwa river, Maramuca is not a feira at all. According to the Portuguese, a feira is only recognised as such when a document, Regimento, establishes it through the appointment of a Captain or similar officially-appointed officer. So the trading establishments on the Angwa River and Maramuca would not have been regarded as feiras until the Captain of Mozambique Island appointed or recognised the first Portuguese Captain. However Maramuca was definitely a trading settlement where local people traded gold for the cloth and beads that the Portuguese kept as stock.

A Portuguese trader Gonçalo Joao gained the right to trade in this area in the 1660’s on the eastern edge of the lower Umfuli Gold belt and he probably caused the enclosure walls and store rooms and trader residence to be constructed. However at the same Mutapa Kamharapasu Mukombwe gave the same rights to trade in the area to António Roiz de Lima and a Mwanamuzungo priest, Fr. Simão Gomes, both very rich traders at Sena. In response to him trading within their monopoly area, António Roiz de Lima and Fr Simão Gomes began to encourage the local chiefs around Maramuca to rise up against Gonçalo João by sending them arms and men. Joao was unprepared for this assault and because he had no defences, his feira was attacked and pillaged around 1680.

The site bears a very close resemblance to the earthworks at Luanze (Ruhanje) with straight banks enclosing a rectangle orientated precisely north, 220 foot (67 m’s) wide and 180 foot (55 m’s) long, with bastions 20 foot (6.1 m’s) wide projecting 15 foot (4.6 m’s) from the centre of each wall. The steep eastern slope of the kopje summit necessitate a further wall across the centre of the site with an artificial terrace retained by a revetment wall of massive quartz boulders extending east of it, doubtless to provide a level building base.

The most important structure on the site is a rectangular brick building close to the western bastion, the top of whose southern wall stands today some 9 foot (2.7 m’s) above natural ground level. This building was externally 19 foot 8 inches (6 m’s) wide and probably 27 feet (8.2 m’s) long, divided into a series of three long, narrow rooms, each 7 foot (2.1 m’s) wide and 16 foot 4 inches (4.9 m’s) long internally, probably very similar to those under the central mounds at the Angwa feiras.

Walls were built of sun–dried brick of a highly calcareous, pale grey, very fine sandy loam, probably derived from antheaps on the Suri Suri alluvium. The bricks are 5¾ inches (15 cm’s) high and 10½ inches (26.5 cm’s) long and the wall 20 inches (51 cm’s) thick, with the dhaka mortar of the joints 1 - 1½ inches (2.5 – 4 cm’s) thick, giving four courses to 2 foot 3 inches (69 cm’s)

Garlake’s excavation inwards to the centre of the enclosure wall revealed that the wall was not an earth bank as anticipated, but that its core was built of three courses of brickwork of identical size and fabric to the main building, giving a total height of only 1 foot 7½ inches (50 cm’s). Against this core, gravel and soil was piled: this construction is identical to that found by Garlake when he excavated the enclosure wall around the church at Dambarare.

Chunks of dhaka outside the enclosure walls indicate that further dwellings were situated outside the enclosure walls.

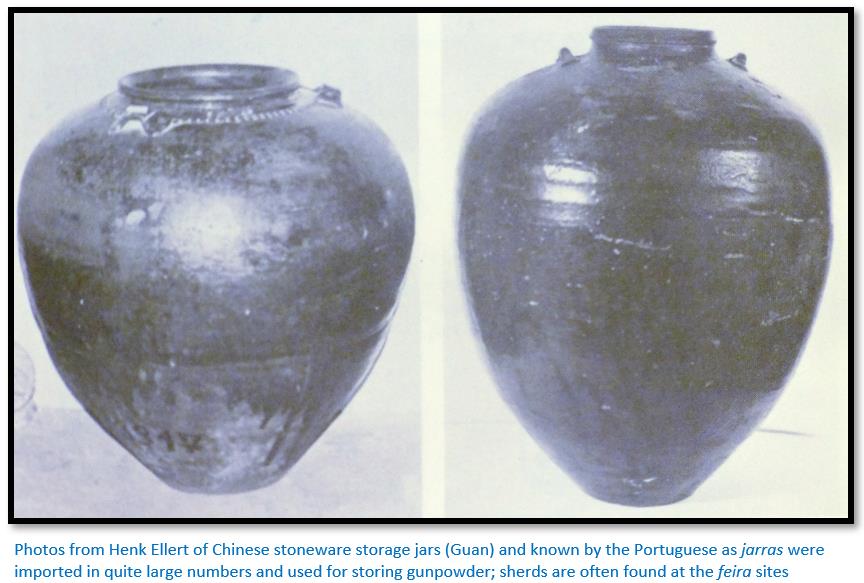

The only imported ceramics found was parts of a 17th century Chinese black glazed storage jar that were found at three different areas of the site.[xxxvii] Few sherds of local ware were recovered from the Maramuca site, just a few rim sherds similar to those recovered at the Luanze feira, a bowl with constricted opening and a shouldered pot with outward bevelled rim. A few of the usual trade beads were also found.

MASSAPA (BARANDA FARM)

See article under Mashonaland Central on this website

Massapa is described by Diogo do Couto as a settlement with a Dominican church dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary and situated near the wooded Mount Fura in an area rich in gold. Francisco de Sousa in the 1609 Oriente Conquistado describes the nearby Mocaras (Mukaradzi) river where the local people panned for gold in April to October when the summer rains have finished and water levels are lower.

Innocent Pikirayi and the Archaeological Unit of the University of Zimbabwe have conducted extensive surveys, fieldwork and excavation at the site of Baranda and adjacent farms and Pikirayi has authored numerous scientific articles discussing the findings and their relationship with the Mutapa state.

These numerous surface and excavation finds of beads, imported Chinese and Portuguese porcelain and stoneware – detailed in the article on Massapa feira, show conclusive evidence of a complex of trading settlements over at least four square kilometres and an extensive Afro-Portuguese trade.[xxxviii]

There are no physical structures visible at Baranda Farm. However the presence of pole-impressed dhaka remains points to the Portuguese descriptions of the buildings: “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass” being correct. Centuries of agricultural ploughing have left the site stripped of any visible historical remains.

Other possible Feiras about which less is known

Some of the places mentioned by writers such as Fr Monclaro who was relying on second-hand accounts of Mokaranga for details of where trading took place may well have been mis-spellings and mis-pronunciations of the same places including Arouva, Chevide or Chibide, Chipondo, Dioa, Carangua, Quicina, Macarara and Botare.[xxxix] These may have been Swahili bazaars that were operating prior to the arrival of the Portuguese or simply trading settlements operated by lone Portuguese traders.

ARUANGWA

The location is not known but was one of the eastern trading settlements dominated by Chipangura that also included Masekesa, Matuka, Mutare and Vumba.

BANDIRE

This was located to the west of the Chimanimani mountains and in the valley between the Musapa and Rebvuwe rivers, although Mudenge suggests it may have been between Sofala and Manyika in Quiteve.[xlii] Prior to the establishment of the feira this may have been known as Nyakouee…Antonio Fernandes[xliii] called it Ynhacouce.[xliv] Its ruler according to Fernandes was: “the captain-major of the king of Menomotapa [who]…has great lands and in his lands they have fairs on Mondays which they call Sembaza fairs where the moors sell all their merchandise; the kaffirs also gather there from all the lands and thus they have quantities of supplies: it is said that the fair is as big as that of the Vertudes.”[xlv]

BOCUTO or BOKUTO

The precise location of this feira is still not known although Ellert states Chinese blue and white ceramics have been found near the confluence of the Gwetera and Hoza rivers in the Umfurudzi Park.[xlvi]

Bocuto definitely existed as a feira and there are a number of references. Apart from the Diogo do Couto quote above it was said: “it stands between another two small branches of the river which also come to join together into a big one, and the fair is some two leagues (10 kilometres) from the nearest banks of either and is 40 leagues (200 kilometres) from Tete to this place, and 13 leagues (65 kilometres) from Luanze as the crow flies.”

Another quote states: “the third fort shall be at a place named Bocuto, where there is also a feira, along the river Manzovo (Mazowe) where it is met by another river called Inhadire (Nyadiri) which is 40 leagues from Tete and 10 leagues from Masapa.”[xlvii]

Much artisanal gold panning takes place on these rivers (Gwetera, Mazoe and Nyadiri) even today during the dry season of May to October.

CHIPANGURA

This feira in present-day Mozambique was located in the area of Macequece (Masekesa in Shona) less than 20 km across the Manicaland border at present-day Manica. Manuel Galvão da Silva reported that the garrison consisted of a square stone and clay construction whose only function was to provide an enclosure for the church, built also from stone and mud under a thatched roof.[xlviii] The garrison comprised of Portuguese, mwanamuzungo[xlix] and African soldiers was under the command of a Capitão Mor and the feira had a resident Dominican priest. Chipangura dominated the eastern feiras in the 16th and 17th centuries.

The traders lived scattered around the feira because there was fierce rivalry between them and they also wanted to avoid inquiry from the Capitão Mor. The region was known for its fine gold and Ellert writes that the general secrecy around the gold trade was noted in 1634 when Vides y Albarado and Francisco Figueiredo de Almeida made an inspection tour of the gold mines of Manicaland and the Revue Valley when the Capitão Mor was Antonio Coloco. His presence indicated that an official Regimento had been issued establishing the site as an official feira.[l]

Bhila states the Manyika people brought gold, agricultural produce and metalwork to the feira in exchange for cloth and beads and that the population of mwanamuzungo and vashambadzi peaked in April and May when the rains ceased and local people were panning the rivers for alluvial gold. He states that the town’s status as a trading settlement continued even after the Rozvi invasions when the Portuguese had fled.

Ellert suggests that the modern fort in the town that was captured by the British South Africa Company under Forbes on 19 November 1890[li] may have been sited on a much older site as Engineer Pires de Carvalho who examined the fort in 1946 found much older Portuguese faience ware and imported ceramics.[lii]

CHIPIRIVIRI

This was apparently a chuambos in Mokaranga. Rezende in Estado da India states a chuambos was: “Only a palisade of stakes, filled up inside with earth, allowing those within to fight undercover. The stakes are of such a nature that when they've been two or three months in the ground, they take root and become trees, which last many years.”

No Regimento appears to have been issued in respect of Chipiriviri, or a Captain or similar officer appointed, so it would not have had feira status and been recognised simply as a trading settlement that individual Portuguese traders used as a base.

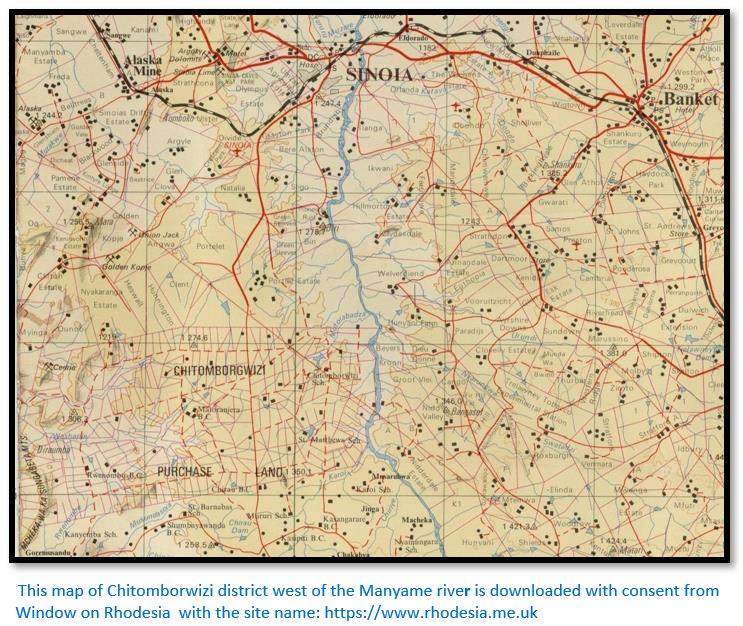

CHITOMBORWIZI

This feira is referred to by several Portuguese historians. Father Filipe de Assumpção in 1698 refers to it as Quitamboroizi. Antonio de Conceição stated that Chitomborwizi was located near the headwaters of the Angwa river, but it has not been positively located.

Copper was extensively mined at the present-day site of Alaska Mine by pre-European miners. Summers states the workings were 1,700 x 150 x 70 ft deep (518 x 46 x 21 metres) Hyper-inflation and poor economic policy resulted in its shut-down in 2000, although the Chinese were said to be investing in a smelting, flotation and electrolysis plant in 2021 but many of these investment projects have not gone beyond press articles.

Summers states Golden Kopje pre-European gold output was between 10,000 – 50,000 oz (283 – 1,417 kg)[liii]

The area is still named Chitomborwizi as the map below shows.

No traces of a feira have been found at Zviringohwe hills, Ellert thinks the site may have been visited by Portuguese traders or their vashambadzi for seasonal trade only, although Mudenge states it had a chuambos. Chitomborwizi was said to be three days travel from Dambarare feira and that the residents in the 1680’s were the so-called Canarins who were Konkani people from Goa and were recruited because they were Christian Indians. Ellert states that they built good trade relations with the Africans and some had experience at gold mining from India, so that gold production actually increased at Angwa and Chitomborwizi, but that they conducted gold trading in great secrecy so as not to alert the Rozvi Changamire in Abutua to the west.

HWANGWA

Another trading settlement whose location is not known, but on the Zambesi river, possibly near Ingombe Ilede and used by Swahili traders. It is possible that Hwangwa is the same location as Urupande. Mudenge states it was in the land of the Mombara (Mambara) people and copper was traded between the Moslems, the Karanga of the northern Mashonaland Plateau – probably mined at sites such as Alaska Mine and the Angwa Valley.[xl]

When Gatsi Rusere declared war (mupeto) on the Portuguese for not paying the customary kuruva (tribute) much Portuguese property was seized and some traders and their vashambadzi killed. Among them was Diogo Simoes Madeira, whose property at Hwangwa / Urupande was seized, but whose life was spared.

In the 1630’s during the reign of Mavhura Mhande the Portuguese are said to have built a chuambos at Hwangwa. It was: ”only a palisade of stakes, filled up inside with earth, allowing those within to fight undercover. The stakes are of such a nature that when they have been two or three months in the ground they take root and become trees which last many years.”[xli]

By 1679 the vashambadzi of Goncalo Joao – who established and then lost Maramuca (Rimuka) - were the last to leave Hwangwa which was then abandoned.

MAKAHA

The site of Makaha is reached by dirt road from Mutoko. The nearby Ruenya river has been known as a productive source of alluvial gold for a long time and much artisanal mining has taken place down to the Ruenya river. Karl Mauch in 1871-2 named it the Kaiser Wilhelm goldfield[liv] and the two most prominent peaks Mt Bismarck and Mt Molke. Carl Peters in 1899-1900 also skirted the edge of the Makaha goldfields but was disappointed by its prospects although he recognised that gold working had taken place.[lv]

In Monuments of Rhodesia listed by the 1953 Rhodesian Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments and Relics a ‘Makaha fort’ is listed as No 69 and described as: “an old Fort situated on Lawley's Concession to the left of the road leading to the Ruenya river about 3 miles before striking the river. The building was obliterated many years ago but the north and east sides were still clearly defined. The fort consists of a rectangular enclosure measuring 40 yards by 40 yards bounded by a stone and mud wall about 5 feet in height. This was loopholed. At the corner on the eastern side are two bastions.”

Surveys and very limited excavation work failed to provide any further evidence of a Portuguese presence. The claim to it being Portuguese is based on separate reports by Mr Paré in 1945 to Mrs Goodall in her report on the Angwa (Ongoe) feiras[lvi] when he said he had seen “similar forts near Mt. Darwin and Makaha” and by “Mr. McGregor, of the Geological Survey, has seen one fort at Makaha; he says it is exactly similar to Plan ‘D’ of No 4 Fort, in the Angwa valley.”

Chris Dunbar in his article on the site[lvii] writes that he discussed the Makaha site with a staff member from National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) and others “and all agreed that this site was not actually Portuguese or at least there was very little evidence to show that it was settled by the Portuguese.”

MANZOVO

This was apparently another chuambos in Mokaranga, probably near the Mazowe river from which the name is derived and like Chipiriviri no Regimento appears to have been issued in respect of Manzovo, or a Captain or similar officially-appointed officer appointed, so it would not have had feira status and been recognised simply as a trading settlement. It is mentioned by Couto in Da Asia and may have been a mining area where trading took place. There is a possibility that Manzovo (i.e. Mazowe) and Matafuna which is also close to the Mazowe river, are one and the same.

MATAFUNA

Even today the area around Tafuna Hill in the Shamva district undergoes extensive artisanal mining. Summers states that many large pre-European workings were sited on sulphur impregnated reefs, in particular the Shamva Mine itself carried very large ‘ancient workings.’

Under Area 4 for Shamva most of the gold mines he lists had recorded ‘ancient workings.’

Meyer of the Geological Survey recorded that Matafuna was close to the Alliance Mine on the lower north west slopes of Tafuna Hill. The Alliance Mine itself had 30 shafts to a maximum depth of 98 ft (30 metres) and extensive underground stopes, some 8 ft (2.4 metres) high. The reef measured 17 dwt (26 grams) and some of the remaining pillars measured 27 dwt (42 grams)

Many rivers that flow through gold bearing areas are tributaries of the Mazowe river which flows east to the north of Tafuna Hill and has provided alluvial gold for many millennia. They include the Murowodzi, Tateguru, Inyauri, the Pote that flows to the west of Tafuna Hill, Inyagui, Gwetera, Mukaradzi and Nyadiri. The region as a whole was an important source of gold with a number of feiras located for trading for the alluvial and reef gold including Dambarare, Matafuna, Bocuto and Massapa. Indeed, extensive artisanal gold panning and mining continues to this day.

Mudenge notes that a chuambos was situated here. It was: “built of stakes like the rest and has within it a church served by friars of St Dominic.”[lviii] Matafuna was probably a trading centre, but not a feira.

MATUCA

Theal writes that João da Costa was the principal trader at Matuca in 1535-6 when Vides y Albarado inspected the gold mines in the region.[lix] Mudenge states it was defended by a chuambos. Like the mining experts who accompanied Homem into Manicaland in 1574-5 he recommended that the Portuguese should continue to let the local artisanal miners pan the rivers, rather than try and recover it themselves.[lx] Although it should be noted that Homem’s expedition only reached Quiteve, Manyika and Chikova, but not Mokaranga and the Mutapa state.

Matuca is another trading settlement whose exact site has not been established, but Ellert believes was situated in the Mukahanana Hills on the headwaters of the Odzi river, or on the Mutare river. Father Gaspar de Macedo visited the settlement in 1633 and preached at the Chapel of St Dominic, he also reported that local pre-European miners found enough gold to exchange for considerable quantities of cloth. In more recent times Ann Kritzinger has authored many articles on gold mining in Manicaland[lxi] where artisanal gold mining continues to be carried out.

Early prospectors and members of the Geological Survey reported the river gravels had been extensively mined leaving terraces, craters and gravel dumps.

All the trading settlements and feiras were abandoned before the Rozvi invasions of 1693-4.

MAUNGWE

The territory of Maungwe was between Manyika and the Mutapa state but Portuguese knowledge of this area from their documents is extremely scanty.[lxii]

VUMBA

Another feira about which little is known but part of the eastern feiras in Manyika.

ZUMBO

It is most certain that Zumbo was used by Swahili traders long before the Portuguese arrived on the east coast of Africa. The evidence points to the Zambesi river being used as a trade route from as early as the 8th century as imported exotic items have been found in graves excavated at Ingombe Ilede some distance up the Zambezi river. Beads, ceramics, cloth and cowrie shells were exchanged for copper and malachite from Katanga, gold from the northern Mashonaland Plateau and rhino horns and ivory from present-day Zambia.

After disrupting the Swahili traders from Angoche by blocking their passage up the Zambesi river the Portuguese tried to take over and monopolise trade with the interior from their settlements at Sena and Tete.

Zumbo was proceeded by a trading settlement dating from c.1540 on an island in the Zambesi river called Chitakatira in the 1720’s. It was settled by the so-called Canarins who were Konkani people from Goa and were recruited by the Portuguese because they were Christian Indians. Ellert states that they built good trade relations with the local Africans and traded in gold and ivory; small communities of Canarins in the 17th century were also at Angwa and Chitomborwizi on the northern Mashonaland Plateau. Eventually they moved to a healthier site – present-day Zumbo, on the eastern bank of the Luangwa river where it joins the Zambesi in the far west of Mozambique.

Zumbo’s importance grew after the Rozvi invasions of the northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland in 1693-4 when the Portuguese trading settlements and feiras were abandoned. The trade in ivory was particularly important. Early European maps rather exaggerate the importance of Zumbo but indicate an active Portuguese presence.

Ellert writes that in 1726 Father Pedro da Santissima Trinidade was installed as vicar and given title to land at Zumbo and had a Chapel and residence built “with the cross in his hand and virtue in his soul, and also like St. Francis Xavier, with a host of remedies for the ills both of the body and the spirit, he made an enormous number of converts whom he raised from a state of barbarism ... he rapidly became famous for his piety and virtues.”

Although he treated the surrounding district as his personal fiefdom for the next 25 years controlling 1,600 slaves and monopolised the gold and copper trade and slaves, he taught local people many European farming skills. During the serious famine of 1743 - 44, he organised much relief work for the people and acquired the status of a cultural hero among the local population. In fact he was held in such high esteem that even after his death in 1751 he was remembered as a mudzimu or ancestral spirit.[lxiii]

Between 1730 – 1760 were the most prosperous times for Zumbo. Extensive gardens were laid out along the banks of the Zambesi river where orchards of mangoes, bananas, papaya were grown for the benefit of local people. The vashambadzi (agents of the Portuguese traders) travelled widely and bartered beads, cloth, Chinese porcelains, muzzle-loaders, gunpowder and lead for gold and ivory.

In 1754 the Portuguese were driven out of Zumbo and took refuge in Feira on the western side of the Luangwa river where Jose Pedro Diner was appointed commandant. He fortified the perimeter of the settlement with a massive stone wall, traces of which still exist. However, he did not fortify the river frontage, thinking that an attack would not come from the river, but when it did, the Nsenga destroyed the town. Diner was jailed for incompetence and replaced by da Souza.

By 1763 there were 200 Portuguese families living in Zumbo who were led by Francisco Pereira, nicknamed “The Terror” for his brutality. In 1766 Antonio Pinto de Miranda authored a report on Zumbo and its inhabitants who were called Zumbeiros and all of whom were from Goa.[lxiv]

In 1804 Zumbo was captured and destroyed by Chief Mburuma IV and in 1836 the same happened again. “Easter Sunday of 1836 is perhaps the blackest day of all in the history of this small colony which had already passed through so many vicissitudes. From the few trustworthy data now available it appears that nearly all the inhabitants of Zumbo, including the Commandant had crossed the river to Feira, and were the guests of Father Joao. During their absence, Captain Alexandre da Corta, who had quarrelled with the resident official and refused to accompany the party to Feira, betrayed the town and opened the gates of Zumbo to Chief Zeka who with his warriors, entered without firing a shot. The first intimation that the people of Zumbo had of his treachery was when they saw flames leaping out of their new convent and church. The few residents who remained behind were foully murdered, the stores were ransacked, and before this impi left, the town was, for the second time practically razed to the ground. After this calamity, the inhabitants of Zumbo appear to have lost heart, for they did not attempt to rebuild the township; some went to Feira, others left for the coast.”

In 1861 Captain Major Manuel Pacheco was sent by the Portuguese Governor to re-open Zumbo. He rebuilt the Commandant’s house and a few stores were opened by traders, but the place never regained its former size. An attempt was made to reoccupy Feira, but the town was harassed by Mburuma VI and his people and the traders retreated to Zumbo.

F.C. Selous visited Zumbo and was escorted by Senhor Gourinho around the ruins where only the solid walls of the two hundred year old church were still standing.

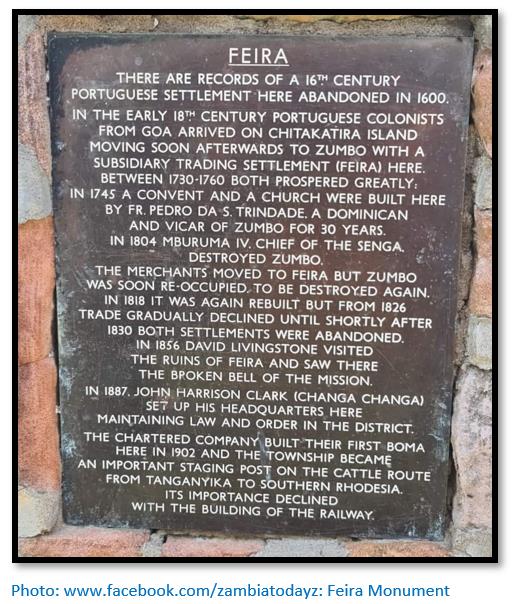

FEIRA (present-day Luangwa)

In the late 1750’s a new Portuguese trading settlement was started on the western bank of the Luangwa in present-day Zambia, but like Zumbo is on the northern bank of the Zambesi in present-day Zambia.

In 1754 the Portuguese were driven out of Zumbo and took refuge in Feira on the western side of the Luangwa river where Jose Pedro Diner was appointed commandant. He fortified the perimeter of the settlement with a massive stone wall, traces of which still exist. However, he did not fortify the river frontage, thinking that an attack would not come from the river, but when it did, the Nsenga destroyed the town. Diner was jailed for incompetence and replaced by da Souza.

By 1818 Mburuma IV was driven out of Feira by the Portuguese who re-built the town and in 1827 Captain Jose Manuel Monteiro was in charge of Feira. In 1830 Mburuma IV was killed during a night attack on Feira, following which a peace agreement was negotiated with Mburuma V by Brother Pedro.

In 1836 Feira was evacuated by Ensign Jose de Sequeira after further attacks by local Nsenga when Zumbo and Feira were again overrun and destroyed. Ellert writes that in the mid-19th century the Portuguese through their Afro-Portuguese Chikunda allies operated an important trading depot at Kasoko, approximately 6 miles (9 km) upstream from the present-day Chirundu border post. They also traded up the Luangwa river.

David Livingstone visited Feira on his epic coast to coast journey from Luanda to Mozambique in 1856 finding the place deserted and in ruins; in 1864 Feira was finally abandoned by the Portuguese.

Feira remained in ruins until the arrival in 1887 of Harrison Clark, or ‘Changa Changa’ as he was known to the local people. Born in the Cape Province of South Africa, he fled north to escape justice after an incident involving the death of an African. There were still some Portuguese at Zumbo, but it had become little more than a base for slave trading and elephant hunting by Afro-Portuguese Chikundas who terrorised the area. Clark raised his own militia from the local people and soon restored order, suppressing the slave trading and inter-tribal warfare and negotiated several treaties highly favourable to himself with various chiefs.

References

D.N. Beach. Documents and African Society on the Zimbabwean Plateau before 1890. Paideuma, vol. 33, Frobenius Institute, 1987

H.H.K. Bhila: Trade and politics in a Shona Kingdom: the Manyika and their Portuguese and African neighbours, 1575–1902. Longman, 1982

C. Dunbar. /www.colonialvoyage.com

H. Ellert. Rivers of Gold. Mambo Press, Gweru, 1993

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa c.1400-1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1988

I. de Almeida Nepomuceno. Guerra da Massangano Luísa de Goengue e o Bonga - interações sociais e poder feminino no vale do Zambeze (1867-1889) Sao Paulo, 2019 for photos of the aringa at Massangano

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969

Notes

[i] A Political History of Munhumutapa, P44

[ii] Ibid, P45

[iii] Monclaro, , “Relação da Viagem” in Theal, RSEA P395

[iv] Documents and African Society on the Zimbabwean Plateau before 1890

[v] See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[vi] Monclaro, , “Relação da Viagem” in Theal, RSEA P395

[vii] A Political History of Munhumutapa, P55

[viii] Rivers of Gold, P41

[ix] See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[x] A Political History of Munhumutapa, P181

[xi] Based on the book Journey which Father António Gomes made to the Empire of Manomotapa edited and translated by Malyn Newitt, OUP Oxford, 2021

[xii] Lexico.com states Portuguese almadia from Arabic al-maʿdiya from al-maʿdiya ferry and ʿadā to cross.

[xiii] The Cuama was the local name for a Swahili outpost – present day Luabo close to where the Zambesi rivers enters the Indian Ocean and on maps from the early 1500’s the Zambezi River became known as the 'Cuama River'.

[xiv] The Luenha is called the Ruenya river in Zimbabwe

[xv] S.I.G. Mudenge has a good Glossary of local terms in his book, xi - xx

[xvi] D. Livingstone. Missionary Travels and Researches in South Africa, London, 1857. P655).

[xvii] Prazo were a system of landholding introduced by the Portuguese on the Zambezi river. They date from the early 17th century and although later modified at intervals they divided the land along the Zambesi into estates that were leased for three generations passing down the female line. The lease conditions included the obligation to marry a Portuguese, the duty of collecting the head-tax (mussoco) and administering the area, providing military support for the government and paying a quitrent annually to the government. Prazos have been compared to the feudal system in Europe with many of the same characteristics. (M.D.D. Newitt and P.S. Garlake)

[xviii] A political History of Monomotapa, P180

[xix] D.N. Beach. The Mutapa Dynasty: A Comparison of Documentary and Traditional Evidence. History in Africa Vol. 3 (1976)

[xx] Rivers of Gold, P95

[xxi] Ibid, P95

[xxii] A political History of Monomotapa, P184

[xxiii] Ibid, P198. Mudenge writes that Kuruva is the Shona word for paying tax or tribute and the word curva is probably derived from it

[xxiv] Ibid, P183

[xxv] Ibid, P317

[xxvi] Theal II, P416-7

[xxvii] Theal, VII P270

[xxviii] Manzove is a clear reference to the Mazowe river

[xxix] A Preliminary Report on Four Portuguese Forts in the Angwa Valley. Unpublished report Queen Victoria Museum, Salisbury, Rhodesia 1946 by E. Goodall

[xxx] At the time Caetano de Melo de Castro was Captain-General of Sena, Sofala and Mozambique Island. He was later appointed a Governor-General in Brazil and from 1702-7 was Governor and Viceroy of Portuguese India

[xxxi] Rivers of Gold, P29

[xxxii] P.S. Garlake. Some Early Portuguese Relics from Dambarare, Rhodesia. Historical Monuments Commission, Salisbury

[xxxiii] Peter Garlake. Excavations At The Seventeenth Century Portuguese Site Of Dambarare, Rhodesia. Historical Monuments Commission, Salisbury, 1969

[xxxiv] Theal VI, P368

[xxxv] The rivers described are most probably the Nyadire and Ruenya that both join the Mazowe river

[xxxvi] P. S. Garlake. Seventeenth Century Portuguese Earthworks in Rhodesia at Maramuca, Hartley. Historical Monuments Commission, Rhodesia

[xxxvii] These large storage jars were often used by the Portuguese for keeping gunpowder dry

[xxxviii] Rivers of Gold, P55

[xxxix] A Political History of Munhumutapa, P222

[xl] Ibid, P43

[xli] Ibid, P267

[xlii] Ibid, P114

[xliii] See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xliv] As translated by the Sofala clerk Gaspar Veloso

[xlv] A political History of Monomotapa, P44

[xlvi] See the article Umfurudzi Park under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xlvii] Both quotes from Rivers of Gold, P50

[xlviii] Trade and Politics in a Shona Kingdom, P79

[xlix] Offspring of Portuguese / African marriages and relationships

[l] Trade and Politics in a Shona Kingdom, P79

[li] See the article How Mutare and Manicaland were annexed from the Portuguese under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[lii] Rivers of Gold, P73

[liii] One of the first serious attempts at working the deposits was in 1908 by M.R.M. Syndicate (Morris, Robbie, McMurdon). Their mine (the Montrose) consisted of a quarry 70 metres by 10 metres and a few exploratory adits into Zviringohwe hill. In 1914 milling plant was moved from the Ayrshire Mine and by 1915 under C. Digby-Jones, consisted of 55 stamps and 3 tube mills. However the pay shoots formed lenses or pods and stoping the ore proved exceedingly difficult especially since periodic cave-ins were causing ore dilution and in July 1917 the mine closed with a 1908-1922 gold output of 70,011 oz (1,985 kg)

[liv] See the article Karl Mauch, explorer and geologist and the man who claimed to be the first European to visit Great Zimbabwe under Masvingo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[lv] See the article Carl Peters and The Eldorado of the Ancients under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguid.com

[lvi] E. Goodall. A Preliminary Report on Four Portuguese Forts in the Angwa Valley. Queen Victoria Museum, Salisbury, Rhodesia 1946

[lviii] G.M. Theal. History and Ethnography of Africa south of the Zambesi, Vol II, P417

[lix] Ibid, Vol II, P412

[lx] See the article Vasco Fernandes Homem and the search for the Mutapa state’s fabled gold mines 1574-5 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[lxi] Ann Kritzinger. For example: Gold-mining Landscapes of Nyanga

[lxii] Documents and African Society on the Zimbabwean Plateau before 1890, P133

[lxiii] Rivers of Gold, P76-7

[lxiv] Ibid, P79

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: