Home >

Mashonaland Central >

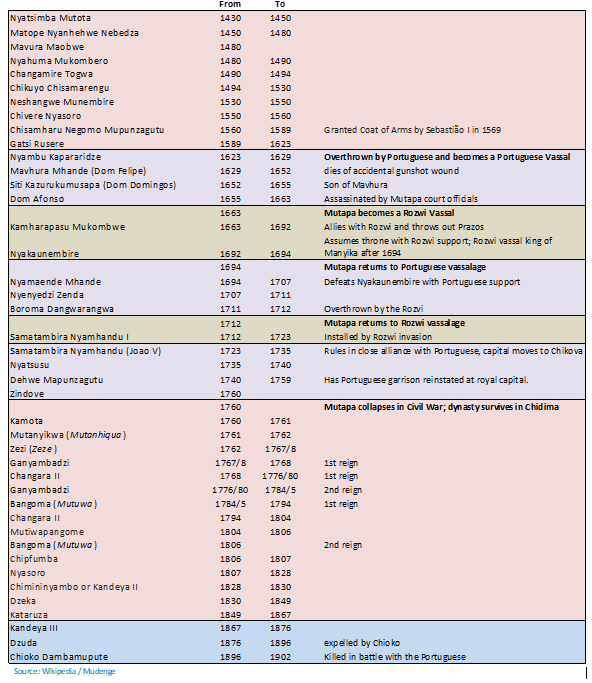

The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623

The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623

Introduction

The article The Rise of the Mutapa State and the early arrival of the Portuguese c.1450 – c.1480 discussed the early emergence of the Mutapa State. Although the exact relationship between Great Zimbabwe and the Mutapa state is still unclear, it appears from the archaeological evidence that Great Zimbabwe’s dominance gradually waned in the 15th Century to competitor regions – Khami in the south-west, and Mutapa, in the north of present-day Zimbabwe.

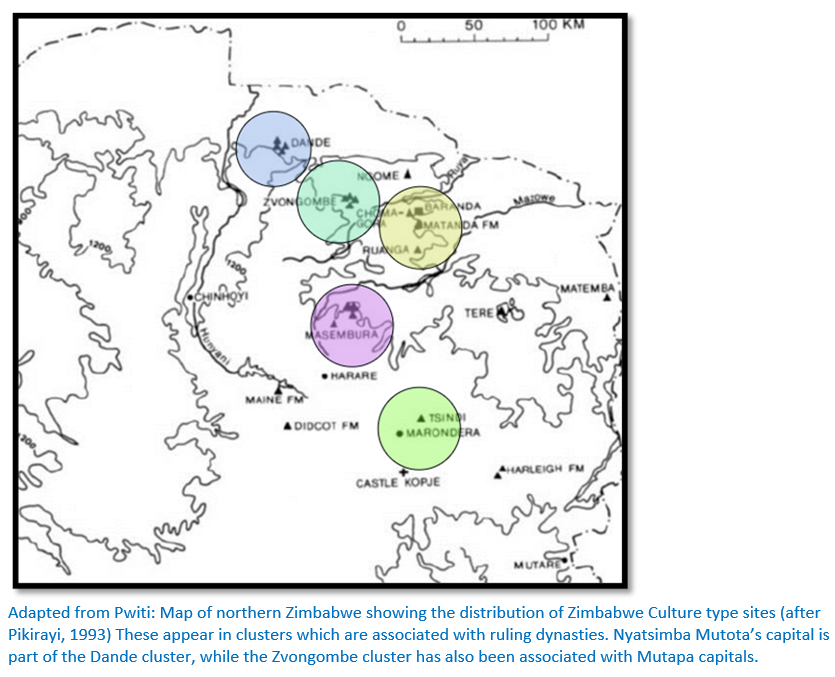

Both Innocent Pikirayi and Gilbert Pwiti believe the movement of the Zimbabwe Culture to the Dande area in north-eastern Zimbabwe may well have involved just the ruling Karanga elite rather an exodus by the general population. The archaeological work by Pwiti also indicates that local populations in the Dande area were slowly and peacefully assimilated with the newcomers, rather than being conquered as asserted by some authors, including Abraham using rather shaky oral traditions.[i] Mudenge writes that peaceful assimilation is less dramatic, but more complex and probably more believable. Archaeological digs in the Zambesi Valley by Pwiti failed to disclose any evidence of conquest by military forces which would have revealed burnt villages and signs of a hurried departure by the vanquished.

Pwiti explains how the Zimbabwe Culture linked to Great Zimbabwe spread to the Mashonaland plateau of present-day north-eastern Zimbabwe in the form of dry-stone buildings, graphite-burnished pottery and spindle-whorls for spinning and weaving, weapons, agricultural tools and metal-working technology.

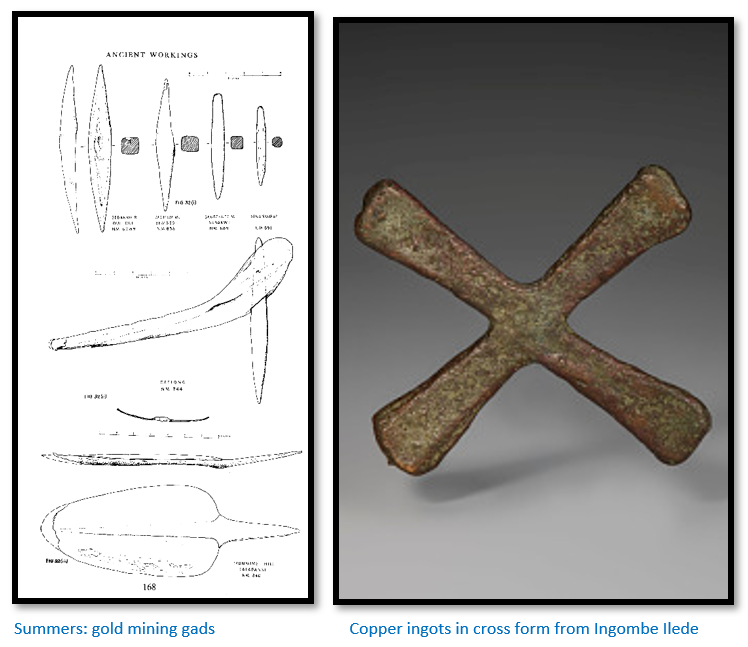

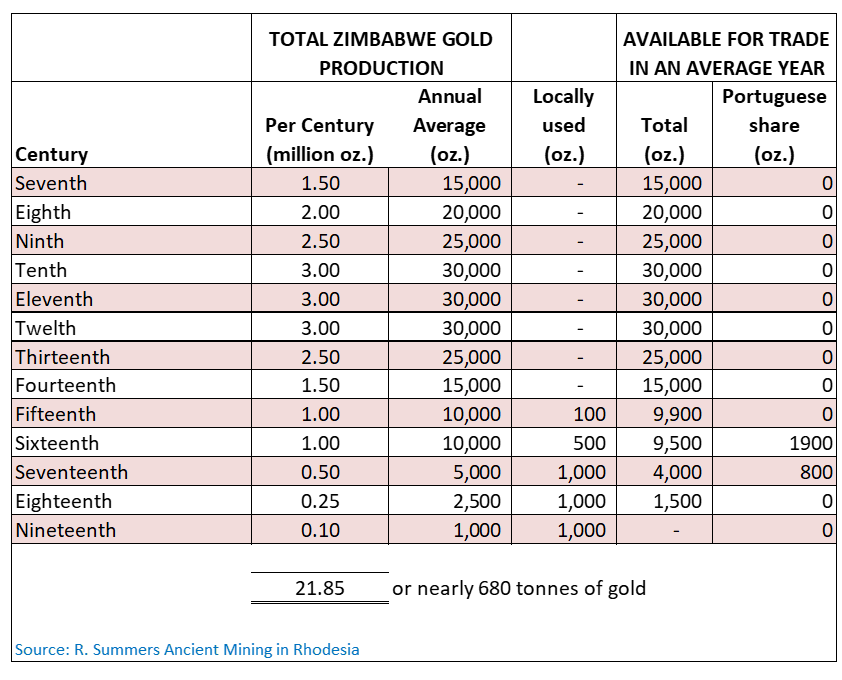

Clearly the northern plateau of Mashonaland had a fertile climate and soil for agriculture and cattle rearing and the greenstone belts were already known to be gold-bearing. Also the long-distance trade was gradually pivoting northwards from the coastal ports towards interior trade centres such Ingombe Ilede that were being accessed from Quelimane and the Zambesi river – the preferred route by the middle 16th Century.

The Mutapa state experienced constant flux throughout the 16 / 17th Centuries

Initially the Karanga rulers of the Mutapa state maintained their influence through marriage between powerful families, working together with the spirit mediums and gaining control over rain-making ceremonies. Elaborate court procedures helped bind senior advisers to the Mutapa, but a major weakness lay in the uncertainty of succession of rulers.

The Portuguese became increasingly active in the plateau of northern Mashonaland during the 17th Century and established a permanent presence at their feiras where they traded for gold and obtained land concessions from the Karanga rulers. Disputed succession within the Mutapa state allowed them to wield significant influence and support the candidates that were positively disposed towards them.

What do we mean by the Zimbabwe Culture?

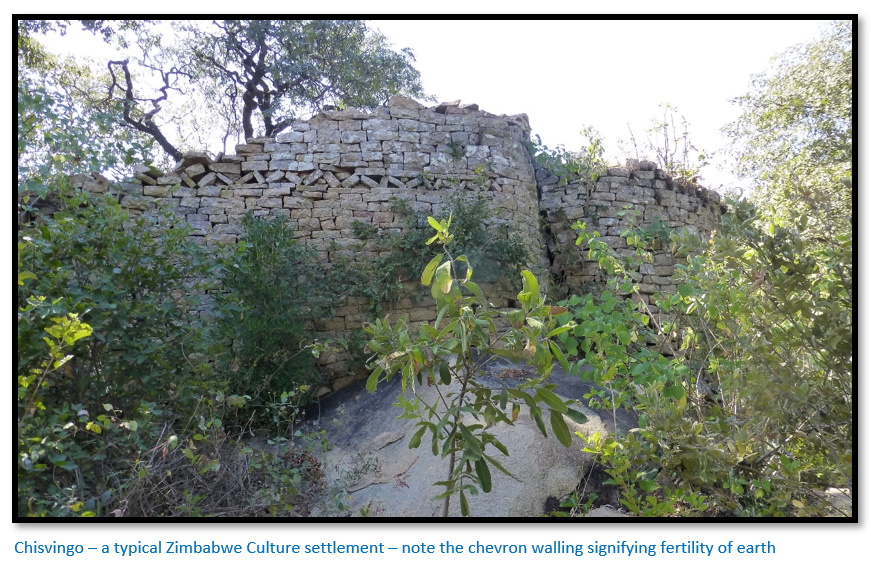

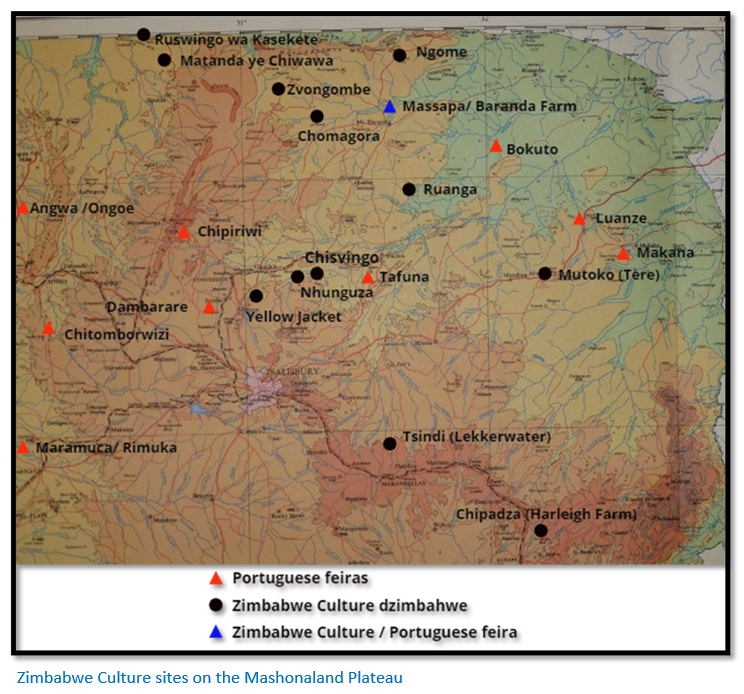

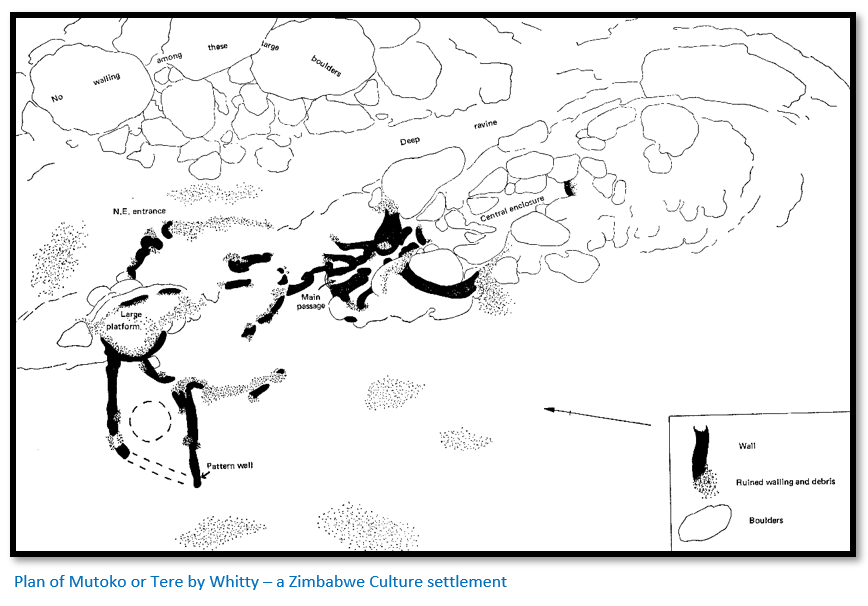

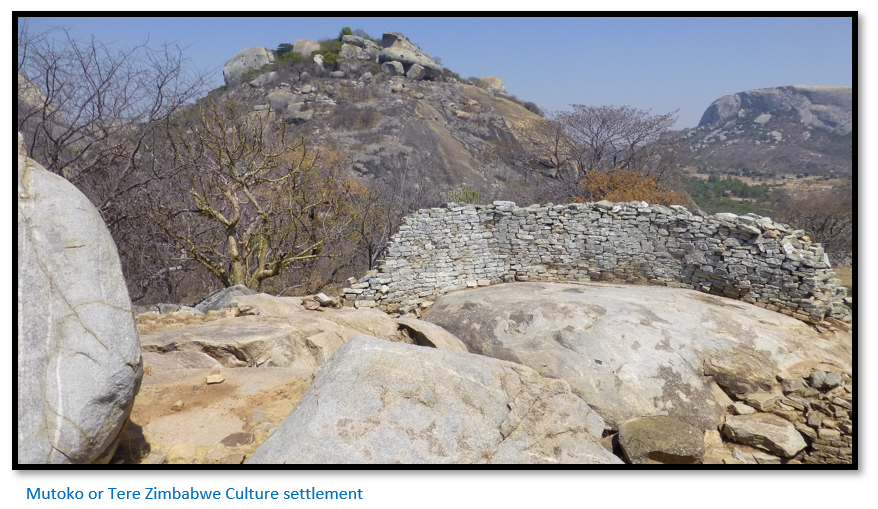

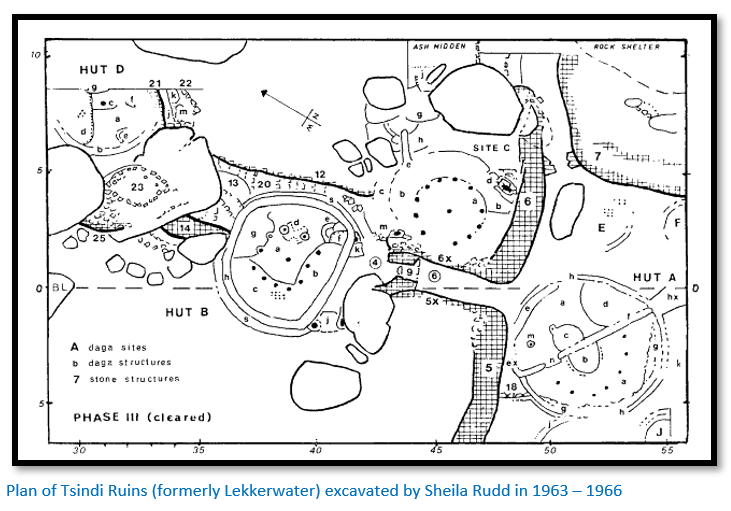

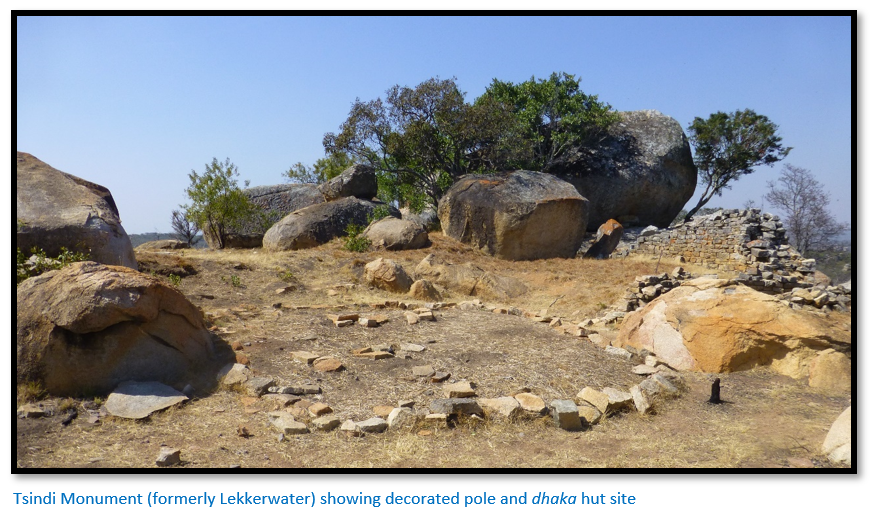

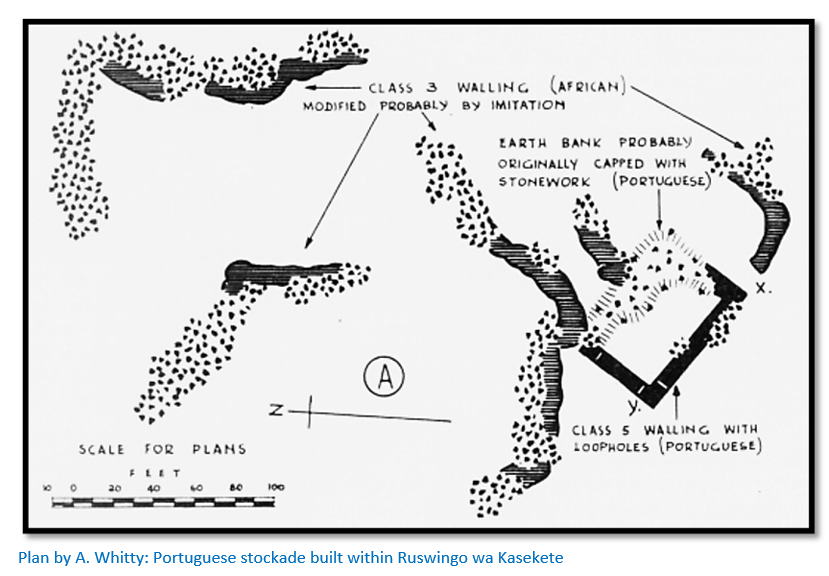

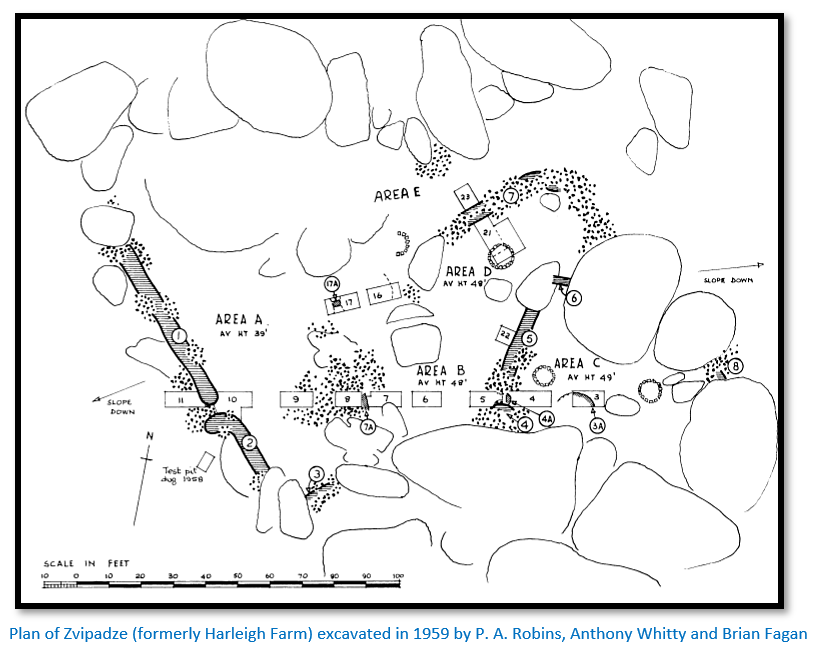

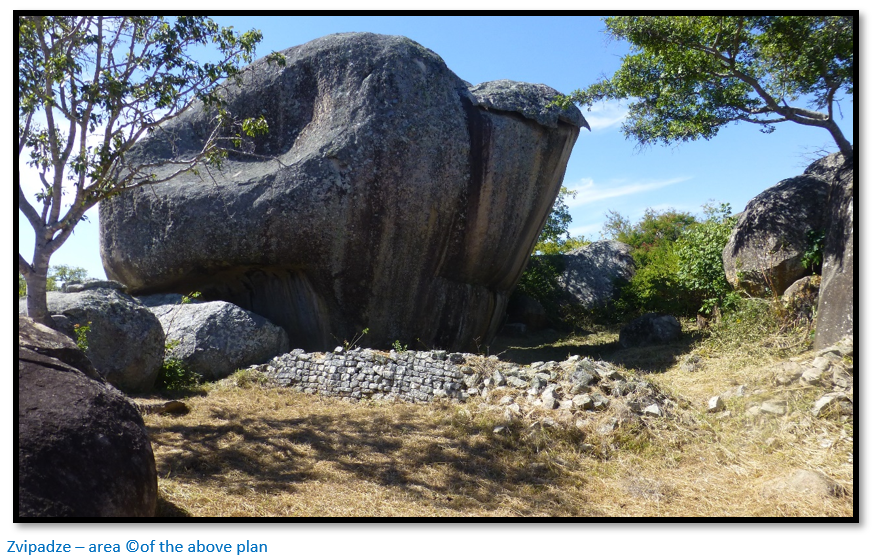

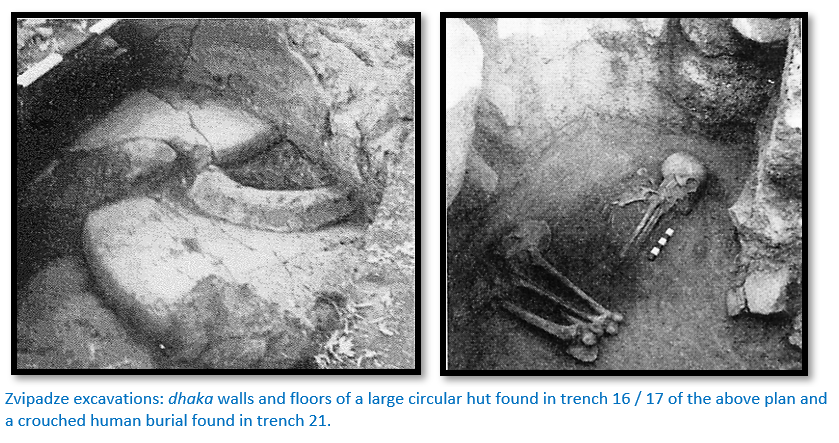

Already described in the article on The rise of the Mutapa state and the early arrival of the Portuguese c.1450-c.1480 are the architectural dry-stone buildings of the Great Zimbabwe Culture that occur singly or in clusters on the northern Mashonaland plateau. Early examples described in the same article include Zvongombe, Nhunguza and Ruanga, to the east Tere (or Mutoko) and further south at Tsindi (formerly Lekkerwater) and Zvipadze (formerly Harleigh Farm)

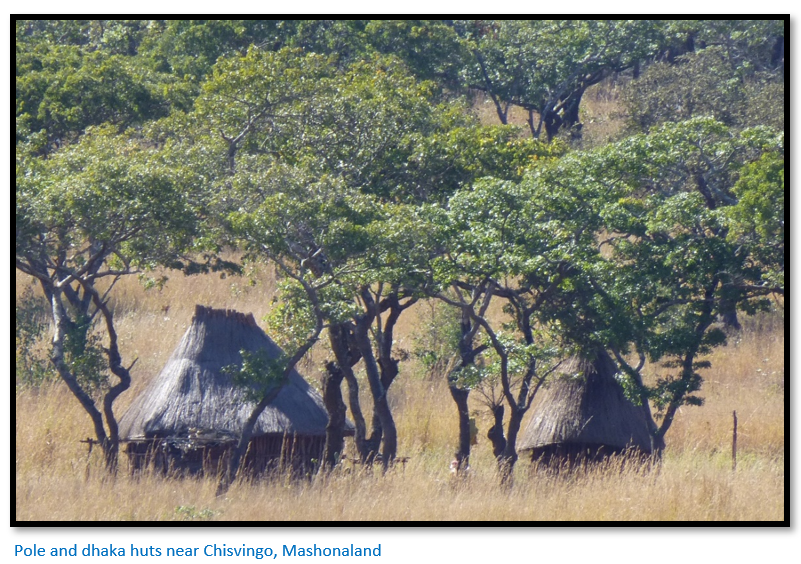

They all represent provincial centres or courts of the elite rulers in the Great Zimbabwe Culture but as time went by the dry-stone walling of their capitals was replaced by pole and dhaka huts such as were surveyed by Innocent Pikirayi at Massapa or Baranda Farm close to Mt Darwin.

The new centres became market towns at which the Swahili and Portuguese traders and their vashambadzi conducted trade with the local communities. Baranda Farm close to the gold-mining areas of upper Mazowe river and Tafuna Hill expanded in size to over a kilometre wide during the 16 – 17th Centuries and served as a regional market place where imported glass beads, glassware and ceramics from Asia was traded for gold, ivory, and skins. No dry-stone walling was found, but plenty of graphite burnished pottery with a clear connection to the Zimbabwe Culture.[ii]

Adapted from Pwiti: Map of northern Zimbabwe showing the distribution of Zimbabwe Culture type sites (after Pikirayi, 1993) These appear in clusters which are associated with ruling dynasties. Nyatsimba Mutota’s capital is part of the Dande cluster, while the Zvongombe cluster has also been associated with Mutapa capitals.

The same article describes what Pikirayi identifies in his book The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States as its most distinguishing features:

- Dry-stone residences known as dzimbahwe’s and referred to as palaces by Main and Huffman with free-standing stone walls laid-out in systematic fashion

- Graphite burnished pottery

- Settlement patterns that separated the elite rulers from commoners.

Main and Huffman point out that Zimbabwe Culture encompasses far more than building construction and that it represented a new social phenomena that included:

- Class distinction between commoners and a new ruling elite that involved sacred leadership that included the ruler taking on the responsibility of rain control[iii]

- The ritual seclusion of the ruler is evident in the architectural layout of all the dzimbahwe and retained in the expression ‘the crocodile does not leave its pool’ a motif that is displayed in the symbolic patterns found in the dry-stone walling.

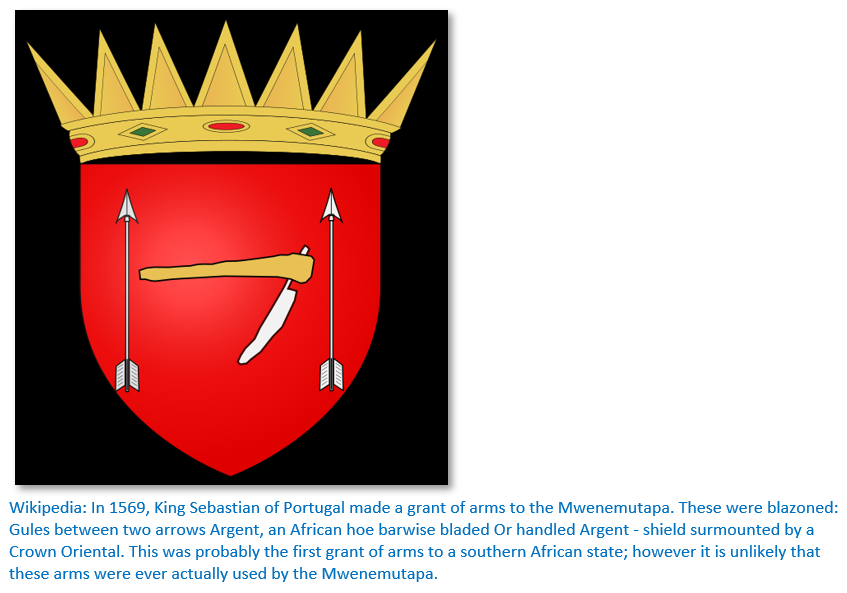

- The rulers duties included providing bounty from the earth – i.e. ensuring the food crops of sorghum and millet provided for the population and control of the rain – the African hoe on the Mutapa grant of arms given by Sebastian I acknowledges this royal duty. Also to provide justice and defend the people symbolised by the golden arrows that flank the hoe.

Pikirayi[iv] dates Zimbabwe Culture from the 11th to the late 19th Centuries and divides it up into three main cultural periods:

- Mapungubwe phase – which marks its earliest emergence from c. 1040 – 1270 in the dry mopane woodlands of the Shashe-Limpopo basin

- Great Zimbabwe phase – dating from c. 1270 – 1550 in the wetter Brachystegia-dominated miombo of the south-central Mashonaland highveld

- Decline of the Great Zimbabwe phase – which split into two regions:

(i)The northern plateau of Mashonaland south of the Zambesi river which evolved into the Mutapa state from c. 1450 – 1900

(ii)Torwa state based around Khami from c. 1450 – 1650, that was replaced by a Rozvi-Changamire state from c. 1680 – 1830

Main and Huffman in their book Palaces of Stone: Uncovering ancient southern African kingdoms further identify the elite ruler’s residence usually on the summit of a hill. Often this may previously have been a rain-making site and thus is known as a sacred place, before being appropriated by the ruler as a royal house.

Archaeological excavations have shown that for the first time the royal houses within the Zimbabwe Culture tradition were built on a platform built behind a stone retaining wall with even stone coursing and that the outline of the ruler’s dwelling: “was clearly designed to separate the leader from his family and followers, providing early evidence for ritual seclusion of a sacred leader.”[v]

Going on they explain that sacred leadership in an African context “refers to the mystical relationship between the leader, his ancestors, the land and God. The king would appeal to God, through his ancestors, to make it rain – to ensure the fertility of the land and of his people. Rainfall thus depended on the ruler’s relationship with God, and a ruler’s power was based in part on the claim that his ancestors could intercede directly with God. The position of sacred leader was thus not hereditary as people believed that the ancestors appointed, or at least approved, sacred leaders.”

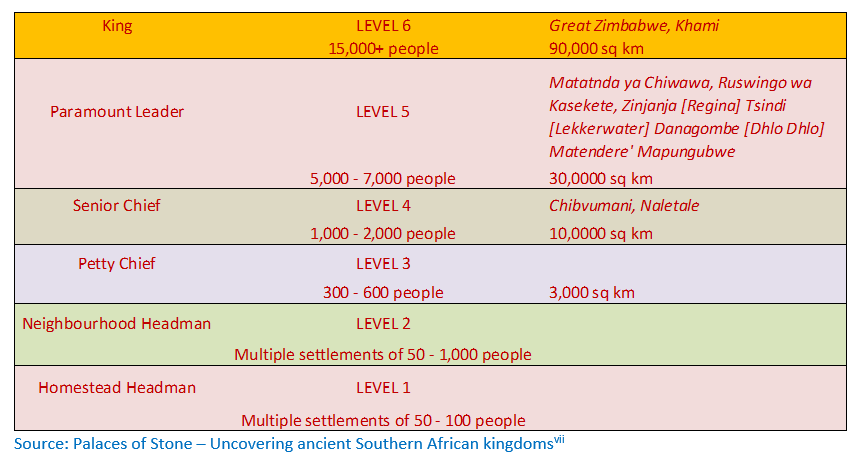

The hierarchy of political levels (i.e. rank) in Zimbabwe Culture

Main and Huffman state that ethnographical research: “allows us to identify six political levels, correlated with settlement size, that functioned as ‘administrative nodes’ within a state – a scheme that applied to all Zimbabwe Culture areas.”[vi]

State capitals administered large areas up to 90,000 sq. kms which in turn were broken into smaller provincial capitals which in turn administered smaller settlements down to individual kraals. The status of each settlement was determined by its population size and economic importance, but the main centres are characterised by palaces with their dry-stone walling that were surrounded by the commoners homes who formed the backbone of the domestic economy based on agriculture (growing sorghum and millet) and pastoralism (raising herds of cattle and small stock)

Portuguese records and Shona ethnography provide the evidence that up to very recent times the administration of disputes between single homesteads to those between towns were settled at a men’s court. The judge or adjudicator in each level of dispute would be from the next higher hierarchal level.

Thus a dispute between members of a settlement would be judged by the Homestead Headman (Level 1) but a dispute between two homesteads would be judged by the Neighbourhood Headman (Level 2) between two different chiefdoms by a Senior Chief (level 4) with “each administrative level being the apex of a pyramid of lower courts.”

Each centre of importance would have a dry-stone building (stone palace) that housed the local leader who represented the Mutapa state’s authority.

Swahili traders from Angoche may have used the Zambesi valley prior to the Sofala route

The Swahili traders who came from the Angoche Sultanate may originally have traded for ivory and gold with the Tonga and Tavara people in the Zambesi valley from as early as the 10th Century and possibly used this route down to Great Zimbabwe instead of the traditional Sofala route even before the coming of the Portuguese.

The Karanga newcomers from Great Zimbabwe may have assimilated with the Tonga and Tavara through marriage and economic ties and gradually extended their cultural influence to dominate the indigenous groups which “marriage, kinship systems and economic ties reinforced and consolidated.”[viii]

Nyahuma Mukombero (1480 – 1490) expands the Mutapa state

The article The rise of the Mutapa State and the early arrival of the Portuguese established that Matope, son of Mutota, came to dominate the Tavara and Tonga people in the Dande, Chidima and Mutavara regions. The extent of his domination is unknown; it may be they simply sent gifts to acknowledge his role as either ally or master.

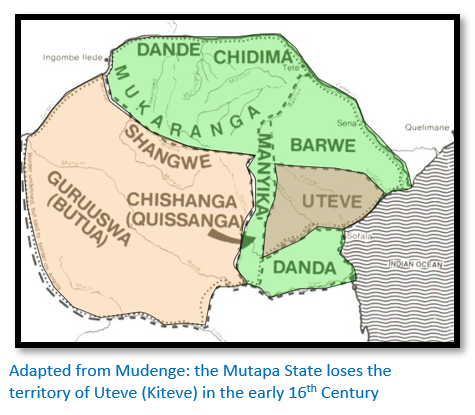

After Matope the state expanded to include Uteve and Manyika, but who actually was responsible for its expansion is unclear. The Wikipedia entry states: “the empire had reached its full extent by the year 1480 a mere 50 years following its creation.” However there is no evidence or explanations as to how this was achieved so remarkably quickly and the statement appears on shaky grounds.

Mudenge quotes Diogo de Alcacova who wrote in 1506, some years after the events, that Changamire Togwa (Torwa) as chief justice or a governor of Guruuswa (Butua) was much favoured by Nyahuma Mukombero and became so wealthy that the Mutapa became jealous and perhaps fearful of his growing influence.

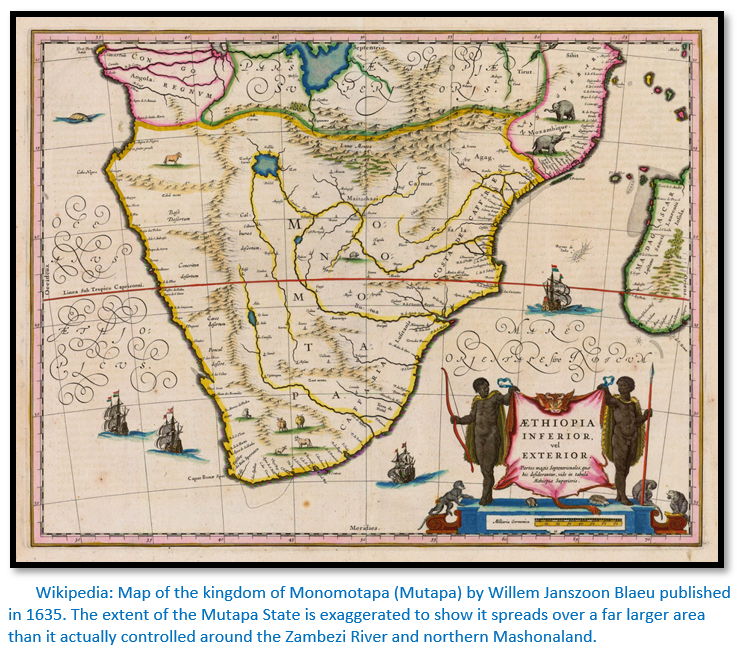

The effective extent of the Mutapa state

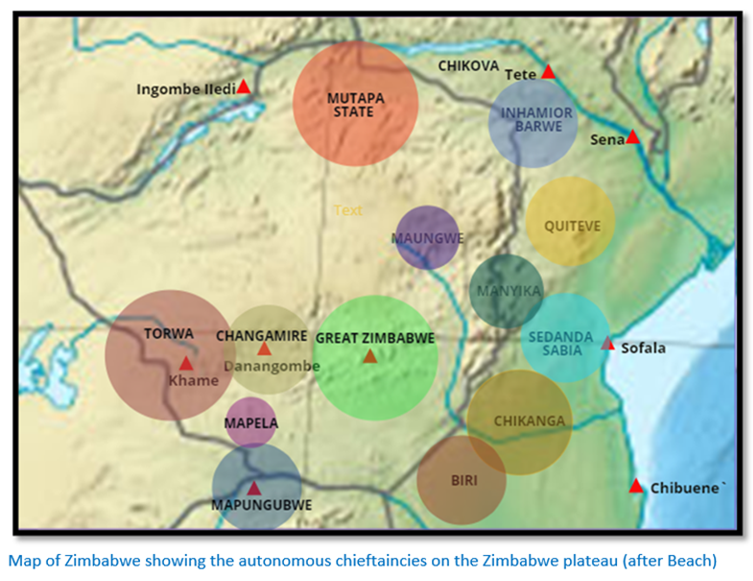

However it is highly unlikely the Mutapa state ever wielded an effective rule over an area as indicated above. There were Karanga settlements as far south as Manyikeni dating from the 14th Century, close to the Swahili coastal port of Chibuene in the furthest south of Danda. In Botswana there are smaller Dzimbahwe built in the 15th Century near the goldfields of the Tati valley (Nkuke and Bluejacket) on the edge of Sowa (Sua) pan and on the eastern edge of the Makgadikgadi region (Toranju, Tlapana and Khama) Other Karanga settlements were established on the Mozambican coastal plain in the regions of Inhamior (Barue) Quiteve (Uteve) Sedanda (Danda) Chikanga, Manyika and Biri.

All these regions enjoyed the cohesion of sharing the Karanga language from their ruling elite who had migrated away from the centre and introduced their Zimbabwe Culture into the areas they now settled and ruled. Although they may have claimed their origins from the region named as Mukaranga above, that did not make them part of a unified and interconnected Mutapa state. What Pikirayi states in relation to the Great Zimbabwe state applies equally to the Mutapa state: “On the face of it, it is difficult to conceive that rulers based at Great Zimbabwe exerted much control over independent-minded local rulers on the Mozambican coast, some 300 kilometres away.”[ix] In relation to the eastern spread of the Zimbabwe Culture he writes: “It is also imaginable that prosperous Leopard’s Kopje chiefs, living in an environment well-endowed with good pasture for their cattle, with gold, copper and salt at hand, imitated the power and prestige of their successful eastern counterparts with whom they probably had commercial ties.”[x] The unsettled events in the centuries that followed proved how impossible this task proved to be.

Nyahuma Mukombero (1480 – 1490) continued

Mukombero offered the Changamire a trial by ordeal through a poisoned cup. Changamire refused the challenge and sent a reply to the Mutapa saying he would rather die fighting in war than by poison. Mukombero then sought a peaceful solution by sending cattle and gold but insisted Changamire drink the poisoned cup. Changamire decided to fight and entered Mukombero’s zimbabwe which had: “houses…which were of stone and clay and very large” where he killed Mukombero and 21 of his 22 sons and declared himself the new Mutapa. The eldest son, Chikuyo Chisamarengu, then 16 years old, managed to escape.

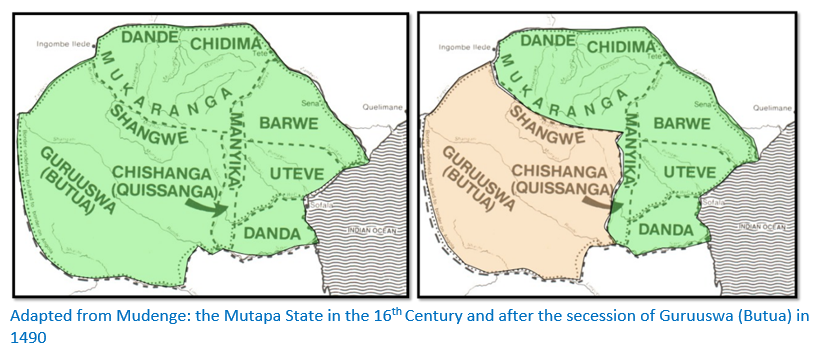

Changamire Togwa (1490 – 1494) Rozvi Secession from the Mutapa state c.1490

Changamire Togwa then ruled in peace for four years during which time he led the Rozvi secession of Guruuswa (Butua) from the Mutapa state. In 1494 he was killed by Chikuyo Chisamarengu in a battle said to have lasted three and a half days.

The territory of Guruuswa (Butua) with its capital centred around Khami would never again be part of the Mutapa state, if in fact, it ever was. The founders of the Torwa state may have had the same origins in c. 1450 as those of the Mutapa state and shared the same Zimbabwe Culture, but there is little historical evidence they were subjects of the Mutapa state. As Pikirayi succinctly puts it: “Breakaway tendencies on the periphery of centralized polities are commonly associated with the collapse of large territorial confederations (Tainter 1988) The basic proposition may be stated simply: feudal states lose effectiveness in direct relation to their territorial extent. Chiefdoms and customary states require constant flows of benefit. As the hegemony grows, those on the peripheries of the circulation of benefit feel left out. Their attention and their allegiances wander to ambitious individuals closer to home, who are in a position to fulfil the social contract.”[xi]

Chikuyo Chisamarengu (1494 – 1530)

Chikuyo re-established control over Barue, Uteve and Dande, but not Guruuswa (Butua) which was loyal to Changamire’s sons. The highlands of Manyika was then unconquered, but the intermittent warfare that continued between Chikuyo and the sons of Changamire resulted in a great decline in the gold trade with the coast.

Manyika was finally conquered by Chikanga, a son of Makombe, the ruler of Barue and loyal vassal of Chikuyo and from 1506 – 1515 the lands from the Indian Ocean coast to Manyika, Barue and Mukaranga in the west were at peace and the gold trade with Sofala re-established.

At the same time Sachiteve Bandahuma, an ally of Changamire became increasingly independent of Chikuyo and sent his son Nyamunda to conquer Madanda, or Danda which he ruled by the time of his father’s death in 1515. In that year João Vaz de Almada, the Captain at Sofala received an ambassador from: “a local lord whom they call Ynhamunda (Nyamunda) and who has risen against the king of Benemotapa (Munhumutapa) and who is a man feared by all the neighbourhood.” [xii] Nyamunda was described as ‘evil,’ a ‘cur’ and ‘very cruel and a tyrant…feared beyond belief.’

Nyamunda’s desire to conquer ‘all the lands around the rivers’ as far as Sofala and Manyika and his claims to the Mutapa throne brought him into conflict with Mutapa Chikuyo.

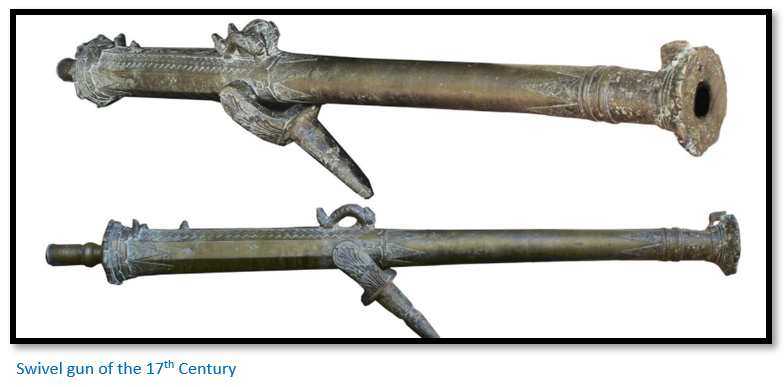

António da Silveira wrote that their struggle was: “for no other reason than to see who shall wed the fortress (Sofala) and have it on his side” because without the goods obtained from trade with Sofala, Chikuyo “cannot get men, or wage war against” Nyamunda. Mudenge writes that Nyamunda had been impressed by the way Portuguese cannons had beaten the Sofala Muslims and the attack on Angoche in 1511 and one of the first presents he asked for was a bombard. Very likely Nyamunda hoped to control Manyika and the route to the gold regions of northern Mashonaland and thus favour the Sofala-based Swahili at the expense of those from Angoche.

The Portuguese fail to grasp the internal politics of the interior and trade at Sofala declines

The Portuguese did everything they could to open a direct trade route with the Mutapa. In 1505 they received his envoys and exchanged presents.

In 1511-12 they sent Antonio Fernandes, a degradado, into the interior in a series of journeys to get information on the Mutapa state and its gold trading system. [See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Although Nyamunda sent presents of gold to the Portuguese at Sofala, he became irritated when the Portuguese envoys sent to him fell sick and refused to acknowledge their presents which included one bombard and sent them back requesting four bombards and soldiers who could operate them.

When it appeared this would not happen, António da Silveira writes that he made certain the Portuguese did not know the routes into the interior and prevented them from trading by robbing and killing Chikuyo’s men who travelled to Sofala and confiscated their gold. The ban on trading gold even affected those coming from Butua who were not at war with him. It seems that Nyamunda’s real intention was to win over the Portuguese as allies in his fight with Chikuyo, when this did not happen, he lost interest in them.

By 1528 Nyamunda controlled access to Sofala which led Dom Lopo d ’Almeida to conclude that: “while Ynhamunda (Nyamunda) is alive, Your Highness cannot gain profit from Sofala” so long as the Portuguese continued to maintain contact with the Mutapa state.

Mudenge points out that historians have explained the decline of the Sofala trade as resulting from Portuguese inefficiency, or high-handed treatment of local people and even a plot by the Swahili traders to favour Angoche at the expense of Sofala. It appears that Nyamunda and his conflict with the Mutapa state may have caused this decline in the gold trade, but this was also reinforced by the Portuguese harassing the Muslims at Angoche.

Internal strife continues in the Mutapa state

In addition to his quarrels with Nyamunda on the coast and the rulers of Butua in the west, Mwene Chikuyo faced other revolts, including one from the captain-general of his army. Gaspar Veloso, the clerk at Sofala who wrote Antonio Fernandes reports in 1512 said: “the king of Butua (Guruuswa)…is as great as the king of Menomotapa and is always at war with him” and later that the king of Ynhoqua was then also at war with Chikuyo.

Neshangwe Munembire (1530 – 1550)

Mudenge writes that in Neshangwe Munembire’s reign (1530 – 1550) Nyamunda continued, as he has with Chikuyo, to frustrate the new Mutapa’s efforts to establish good relations with the Portuguese at Sofala and after supplying Nyamunda with arms and powder their neutrality must have appeared suspect, but finally Portuguese relations with the Mutapa state grew closer.[xiii]

In 1542 Mutapa Munembire sent an ambassador to Sofala saying that in the previous few years Uteve had been closed to them, but hostilities had come to an end. The ambassador asked if the Sofala captain would send his own ambassador to stay at Mutapa Munembire’s dzimbahwe as a sign of Portugal’s good faith and when this was done they would reopen the Sofala trade route. Ambassador Fernão de Proença was sent from Sofala, but very little more is known about his mission.

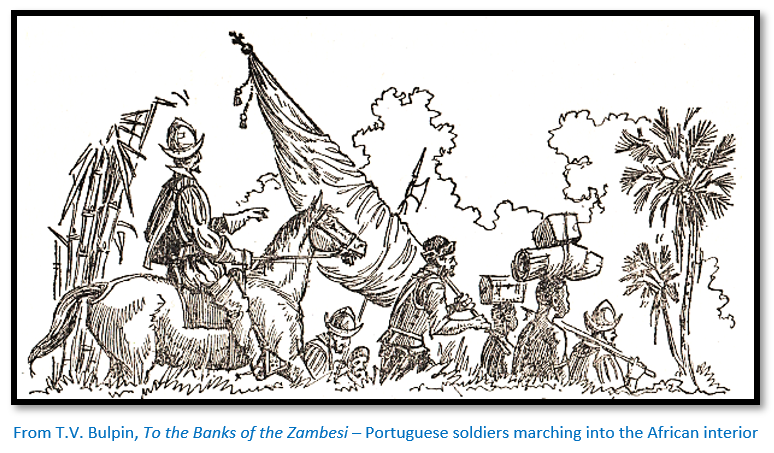

The Portuguese take control of the Zambesi valley from the Swahili traders at Angoche

Father Monclaro who accompanied Francisco Barreto claims Gaspar da Viega was the first Portuguese to use the route up the Zambesi river (called the Cuama on early maps) Between 1530 – 1540 they replaced Muslim bazaars along the river with settlements at Quelimane, Sena and Tete. Initially, Muslims were tolerated by the Portuguese, but in 1572 they were suspected of attempting to poison Francisco Barreto’s horses and men and expelled from the Portuguese settlements [See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

With the establishment of these settlements on the Zambesi river the Portuguese were much closer to the Mutapa state or Mwenemutapa (From the Shona: Mwene we Mutapa)

The Portuguese fight the Tonga in the Tete area

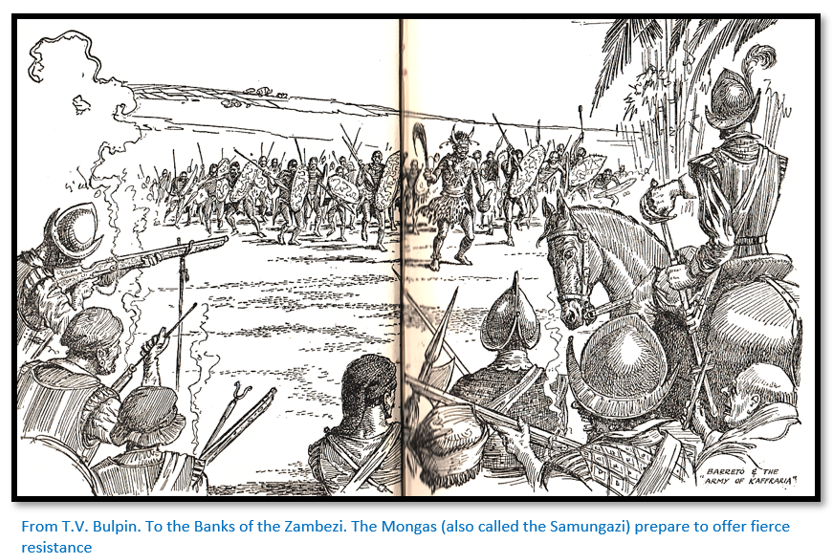

It appears the Mutapa did not rule the area east of the present-day Ruenya river as Fr. Monclaro writes that from about 1550 the Tonga, he calls them the Mongas or Samungazi, controlled a large territory along and south of the Zambesi river. The Tonga had originally been subjects of the Mutapa state, but successfully rebelled until defeated by Francisco Barreto in his 1572 military expedition. Mudenge calls this area Hondosaka which was a major trade route from the Zambesi river into the Mukaranga (northern Mashonaland)

The Portuguese control the Sofala and Angoche trade routes

With Sena and Tete firmly in their hands, control was firmly in Portuguese hands and even the Swahili traders used Portuguese ships to move their trade goods. The Portuguese captain at Mozambique Island had a monopoly of the lower Zambesi and his boats took the trade goods to Sofala and Sena where they were sold to the Portuguese and Swahili merchants at those places. In 1572 there were said to be 20 Portuguese coexisting happily with the Swahili. Monclaros wrote: ”all, Christians and Moors, went about so much mixed together as if they belonged to the same sect and as the Moors were not always evil, those to whom they wanted to give life, they did give it on account of the profit to be derived from the merchandise.”

Diogo Do Couto in Decadas da Asia writes of a : “village of friendly Moors” near Sena in 1571 where: “those Moors, owing to their intercourse with the Portuguese and whom they had, for the most part, grown up together, spoke and wrote our language well.”

Trade with the interior

At Sena Couto wrote the Portuguese merchants initially traded with both Swahili traders and indigenous natives and what was not sold here went to the feiras at Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) Bukuto, Makaha, Massapa, Chipangura (Massikessi) and elsewhere. The merchants at Sena and Tete either travelled into the interior accompanied by as many as 100 – 200 African attendants (vashambadzi) or sent their trade goods with their attendants to the feiras. Couto wrote that: ”up til now not one (of the attendants) has been known to have played any mean trick on his master or have stayed behind in the backlands with his master’s property.”

Typically each, carried on his head a mutoro weighing two corjas, or nearly 25kgs of cloth. They also carried beads strung on macuti threads called mitis. At the feiras they had agents who traded on the merchants behalf. Most Portuguese merchants or their agents sold at the feiras: “at fixed dates.” Only Swahili merchants and African agents sold outside the feiras at inland markets or villages where they often gave goods on credit to the villagers: “and by thus trusting them they oblige them to dig (for gold), and they (the villagers) are so trustworthy that they keep their word.”

Cooperation is replaced by mistrust with the arrival of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J

There is much evidence that Christians, Muslims and African traders initially co-operated in their trading. However the arrival of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. at the dzimbahwe of Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu in late December 1570 ushered in a new era of fear and mistrust. Chisamharu Negomo was a young man of 16 years who had only become Mutapa the same year succeeding his father Chivere Nyasoro and was already being threatened by a pretender called Sachiteve Chipute, who no longer had a claim to be ruler, but saw an opportunity existed. He probably hoped his welcome to this muzungu Mhondoro / Nganga would be reciprocated with strong Portuguese support against his rival.

But Silveira belonged to the Society of Jesus, who saw themselves as soldiers of Christ and looked at the Muslims at Chisamharu Negomo’s court as enemies of the faith and was totally intolerant of their presence in striking contrast to the easy-going relationship of Muslims and Portuguese at the Tete and Sena settlements. Silveira’s mission was to convert the Mutapa and his followers who would then favour Portuguese traders and expel the Swahili traders.

Mudenge says the ultimate aim was for Christians (i.e. the Portuguese) to dominate trade in the Zambesi valley and Silveira was: “more or less a one-man army of invasion on behalf of Portugal and Rome.”[xiv] [The story of Silveira’s martyrdom on the banks of the Musengezi river on 15 March 1561 is told in the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

See the article Chisvingo Monument under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

Consequences of the death of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J

The Mutapa, Chisamharu Negomo, soon realised that Silveira’s death on his orders would have consequences. Portuguese traders warned him the Portuguese would seek vengeance and he should expect God to punish him. He was remorseful and claimed he had been misled by the Swahili traders at his court who were threatened by Silveira’s influence. Two of the four were put to death, the others escaped.

Silveira’s death did not result in an immediate split between Portuguese and Swahili traders but Mudenge states that the gospel of Christianity: “challenged the Shona social and political structures” and threatened those at the Mutapa’s court, although at the time they checked the threat. But Francisco Barreto’s military expedition accompanied by additional missionaries resulted in Fr. Silveira’s influence in the Mutapa state being greater after his death than during his lifetime.

Fr. Silveira’s death used as a pretext for invasion

The Portuguese king Manuel I had requested a legal commission to investigate the murder of Fr. Silveira and whether it justified war on the Mutapa state. In 1509 the Mesa da Conscencia delivered its opinion which was that the king of Portugal might justly make war on Mutapa Negomo on the grounds that the chief had murdered Silveira, robbed Portuguese citizens of their property and allowed the Swahili Arabs to reside in Mashonaland.

Their conclusions: “having seen and examined these documents and reports of many persons, from which it is proved that the emperors of Monomotapa frequently command their innocent subjects to be killed or robbed and are guilty of many other wrongs and tyrannies for slight causes; and that they ordered several Portuguese, peaceably engaged in trading, to be killed and robbed, and that one of these emperors ordered the Father Dom Goncalo to be put to death,” was this warranted reprisal.[xv]

The effective extent of the Mutapa State

Often flatteringly referred to as an Empire, this definition implies a powerful sovereign or central government which appears absent in a detailed examination of the Mutapa state or confederacy.

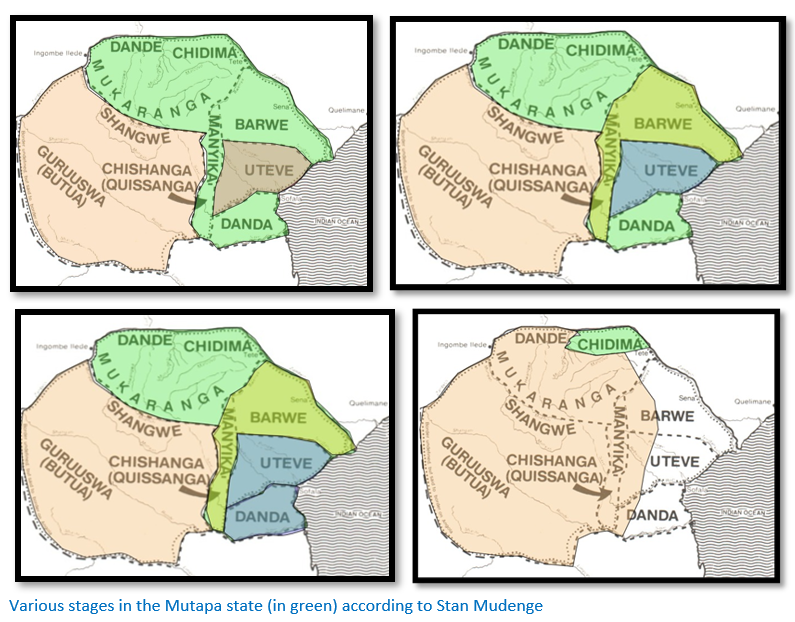

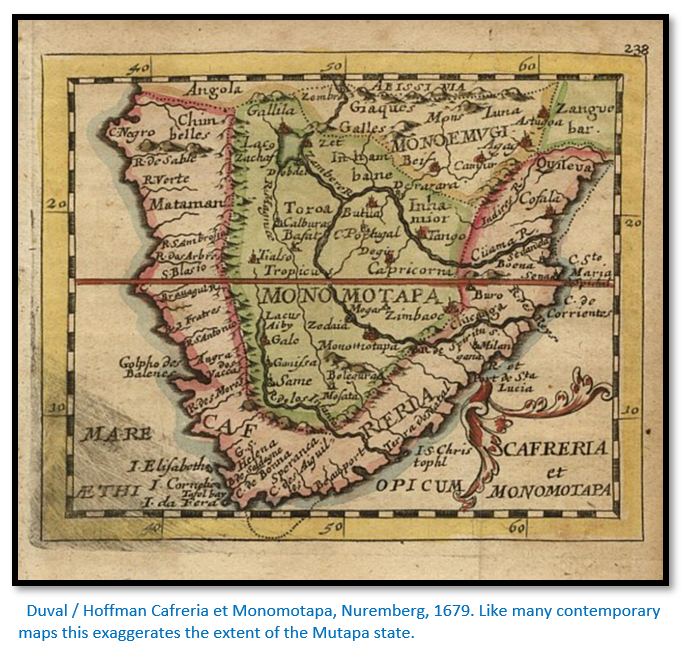

Stan Mudenge states the territory extended initially in the fifteenth century stretched from the Indian Ocean along the Zambesi river as far west as the edge of the Kalahari desert and as far south as the Save and Limpopo rivers and east back to the coast as outlined in his earlier maps. This area of approximately 240,000 sq. miles (620,000 sq. kms) seems unfeasibly large for even a loose confederacy of vassalages and there is no evidence of any military conquest covering this entire area. A large and sophisticated network of political alliances would be necessary to hold a territory of this magnitude together and again there is no evidence to support its existence. Mudenge may have had his own political agenda for exaggerating the area of the Mutapa state much as the Portuguese scribes exaggerated its power and influence in the 16th / 17th Centuries to make their own reports more important.

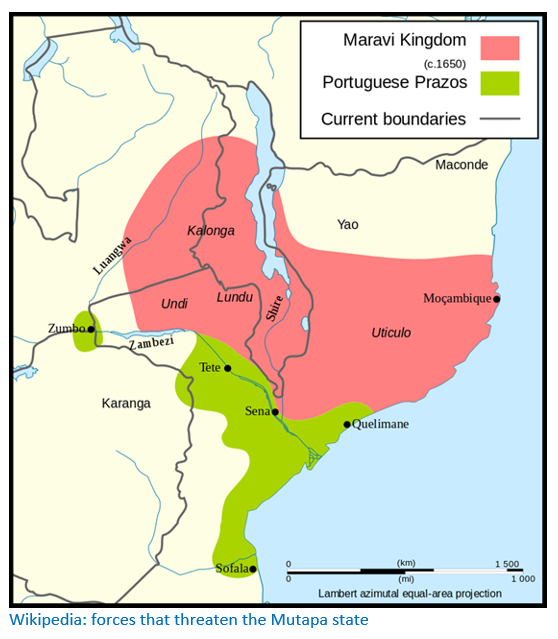

Mudenge states that from the 15th Century the Mutapa state began to contract beginning with the loss of the richest province of Guruuswa (known as Butua to the Portuguese) and by the beginning of the 17th Century it had lost the important coastal province of Uteve (Quiteve) Portuguese descriptions of these eastern Karanga provinces particularly in Quiteve between the Pungwe and Buzi rivers and in Danda between the Buzi and Save rivers report the civil wars between them last into the late 1620’s.

Pikirayi writes the gold trade between the interior and the coast was particularly profitable before the Portuguese switched to using the Zambesi river and its interruption had a particularly adverse effect on the Mutapa state and its vassals in the interior.[xvi] However, the effects of Portuguese intervention in the 16th Century in the politics and economics of the Mutapa state do not appear to have been so significant.

By the mid-17th Century Barue and Manyika were gone as were the Mutiara (Madziva) rulers in Maungwe who were replaced by the Makoni dynasty. Between the 16 – 17th Centuries most of the south of the Zambesi east of Chidima were appropriated as prazos by the Portuguese.

In the last decade of the 17th Century most of the remaining Mutapa state was overrun by the Rozvi. In the first half of the 18th Century only Dande and parts of Chidima in the Zambesi valley remained, but in the second half even Dande was lost, so that only Chidima, south of the Zambesi and around Tete remained.

The Mutapa state needs to be viewed as ever-changing and Mudenge makes the point that many of the generalisations that are made may be valid in one century, but invalid in the next. For example, it may be valid to state that in the 15th Century it was an empire, by the early sixteenth century it is probably more accurate to call it a paramountcy (i.e. a supreme power or authority) held together by a system of vassalage and reduced to a chiefdom by the late nineteenth century.

Historians need to be sceptical of many Portuguese reports to the king of Portugal that are often exaggerated; the Jesuit Fathers needed to emphasise the rich commercial prospects of the Mutapa State as large amounts of resources in supplies and men were being invested by the Kingdom of Portugal that was anticipating the venture being a commercial success.

It is more probable that the area of effective control of the Mutapa state is much smaller than the old declarations of a vast “empire.” The boundaries appear to have run from the Tsatse River, north of Concession down to the Mazoe, then down the Mazoe-Ruenya to the Zambezi River in the east. In the west from the Zambesi to the Manyame (Hunyani) Dande and Shinje rivers, then along the Umvukwes / Mvurwi range of mountains to the Tsatse River’s source.

The Mutapa state was probably centered on the Mashonaland plateau and a wide area of the Zambesi valley lowlands. The plateau segment would be most important economically because most of it received more than 30 inches (76 cms) of rain per year, much more than the dry Zambesi valley and, on the whole, the soils are more fertile.

The Mutapa capital

The Mutapa’s court was called dzimbahwe (Portuguese zimbaoe) meaning ‘large house of stone.’ In the 15th and early 16th Centuries the Mutapa may have surrounded their courts in stone, but subsequently they are built of pole and dhaka (mud) with grass thatched roofs. The capitals were not at one fixed place; each Mutapa was free to choose a new location and often this might be dictated by a loss of grazing or absence of firewood at the old location. So although the socio-political culture of Great Zimbabwe continued with the ruler secluded from the common people, the elite dry-stone walled enclosures disappeared and were replaced by large villages made from local materials. Joao dos Santos noted: “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass.”

For example, Nyatsimba Mutota established his court on the western bank of the Utete River, a tributary of the Musengezi river, near a hill called Chitako-Changonya where he is believed to be buried.

However, his successor Matope Nyanhehwe Nebedza moved his court from the Utete to the Biri River, on the other side of the present-day Mozambique border, perhaps because it was more territorially central.

In time as its territory grew the Mutapa capital very likely moved to a more central location on the northern Mashonaland plateau and may have been situated at or near the Zvongombe complex in the upper Ruya valley. Several sites may have been used at different times by the Mutapas and as the best agricultural land, as well as many gold fields are situated within this area and references from Portuguese accounts indicate until at least the 18th Century the Mutapa capital was in the area of the upper Ruya and Mazowe valleys at Massapa feira / Baranda Farm.

Pikirayi believes the demands of the Mutapa courts for food, firewood and land: “placed excessive demands on the productivity of the savannah environments, leading to the abandonment of more than one court and resettlement in another area.” However the process of the court moving created social stress which in turn: “created shifts in the centres of political power.”[xvii] The court system required demands for labour with the rulers being rewarded with gifts and benefits, but as a court left for more fertile territory, the abandoned group lost the source of their wealth.

Early Portuguese Accounts from the early 16th Century describe the Mutapa’s buildings of Stone

Much research has been based on Portuguese written records dating from 1506 C.E.

In 1506, a Portuguese clerk based at Sofala on the coast of Mozambique wrote a letter mentioning a city "...called Zimbany...which is big and where the king always lives ....”He mentions the houses of the king were "of stone and clay and very large and on one level..." (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 1, pp. 62-8)

Portuguese Gaspar Veloso, about the journeys made by António Fernandes into the Zimbabwe plateau interior where kings always resided in royal places "... made of stone without mortar..." (Silva Rego and Baxter 1962-1975 vol. 3, p. 183)

Duarte Barbosa mentions the town of ‘Benametapa’ as the usual residence of the king, who lived “...in a very large place, whence the merchants take to Sofala gold which they give to the Moors without weighing for coloured cloths and beads which among them are most valued..." (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 1, pp. 95-6).

They describe the capitals of the Mambo’s as “…of stone and clay and very large….” or composed of “…many houses of wood and straw.”

In one of the towns, the residence of the king is described as “…a very large place, whence the merchants take to Sofala gold which they give to the Moors without weighing for coloured cloths and beads which among them are most valued…” (Theal, 1898-1903, vol. 1, 95-6)

From the reign of Neshangwe Munembire (1530 – 1550) the Mutapa’s palaces were not built of stone

Innocent Pikirayi[xviii] states that in the 16th Century Mutapa royal palaces were no longer constructed using stone. The custom of dry-stone building in the tradition of Great Zimbabwe ceased and even when Silveira met the newly installed sixteen year old Mambo Chisamharu Negomo as his kraal on the upper Musengezi river in December 1560 they were living in a kraal of pole and dhaka huts and no mention is made by the Portuguese writers of stone-walled palaces. [See the article The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Even later, Joao dos Santos, who worked as a missionary in Tete in the Zambezi valley from 1585 to 1595, and whose account is mostly borrowed from earlier Swahili traders, is also clear that royal palaces were no longer built in stone. He noted instead that “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass” (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 7, p. 275)

Antonio Bocarro who continued the ‘Decades of Asia' begun by Joao de Barros and Diogo do Couto adds: "The dwelling in which the Monomotapa resides is very large and is composed of many houses surrounded by a great wooden fence, within which there are three dwellings, one for his own person, one for the queen, and another for his servants who wait upon him within doors. There are three doors opening upon a great courtyard, one for the service of the queen, beyond which no man may pass, but only women, another for his kitchen, only entered by his cooks." (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 3, pp. 356-7)

Pirikayi confirms this trend of “State residences in the Mutapa state built using well-coursed stone gradually became smaller, although non stone-walled towns continued to grow in size…Stone walling survived in this and much of northern Zimbabwe in the form of fortified settlements and these cannot be described as urban.”[xix]

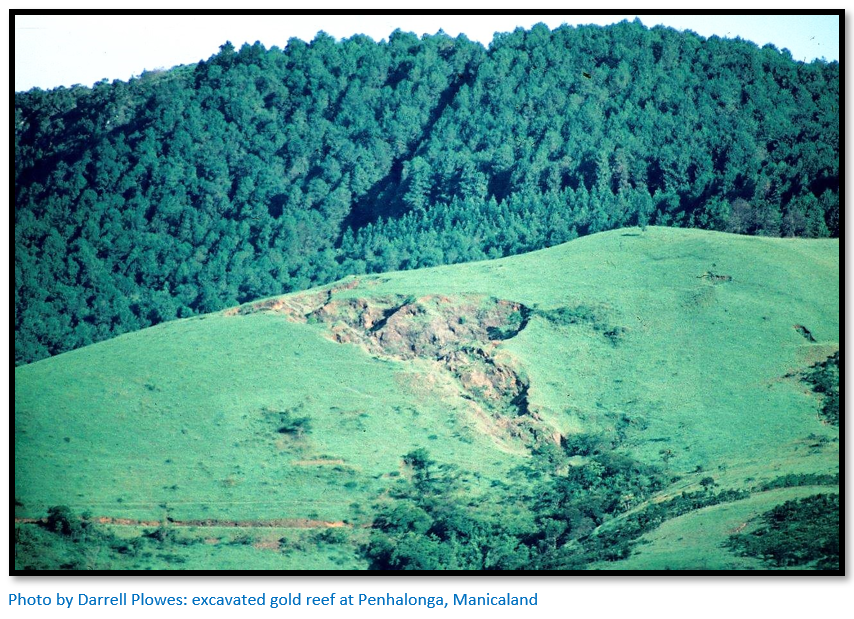

Pikirayi names Baranda Farm, close to, or at, the Portuguese feira of Massapa, 8 kms east of present-day Mt Darwin (or Mt Fura) in northern Mashonaland as a good example.[xx] Archaeological excavations have revealed that the building site covers around 15 hectares, although commercial activities may have covered a much larger area, and the dwellings are exclusively pole and dhaka huts. Baranda Farm / Massapa was sited close to the gold-mining areas of the Mazowe River, Tafuna Hill and Ruya river.[xxi]

Here developed a thriving gold and ivory trade between initially Swahili Arabs from the 10th Century with the coastal cities of East Africa and the Persian Gulf and India. The Jesuit fathers were extremely antagonistic towards the Muslim religion and the killing of the Portuguese priest Father Goncalo da Silveira in 1561 fuelled Portuguese demands for the expulsion of all Moors from the Mutapa’s court.[xxii] [See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

In the 16th and 17th Centuries the trade came to be dominated by the Portuguese. Gold primarily, but ivory and hides (especially leopard) were also exchanged for cotton goods, glass beads and Chinese and other ceramics including stoneware, earthernware and porcelain from Asia and Europe.

Pikirayi’s surveys found imported glass beads, Persian and Far Eastern ceramics and glassware. Also much locally produced pottery from the last phase of the Great Zimbabwe occupation suggesting this was a Zimbabwe Culture community engaged with trade with the Indian Ocean.[xxiii] So important was this trading centre that the Portuguese appointed a permanent resident as the Captain of the Gates who supervised the traders living in Mukaranga and acted as the Portuguese ambassador.

The increasing importance of the trade network becomes the reason for the Mutapa capital moving from north to south of the Zambesi escarpment.

Pikirayi believes that Baranda Farm/ Massapa: “could also be a Mutapa capital, as the same written accounts also mention the existence of such a centre there before moving northwards across the Ruya River.”[xxiv]

Prior to the development of a formal trade network Pikirayi believes the trade in gold was carried out within the physical area of the royal courts. When the Portuguese ousted the Swahili Arab network and established a permanent and semi-permanent presence at their feiras the gold markets sometimes became an extension of the royal settlements, Baranda Farm / Massapa feira being such an example.

The establishment of gold markets that became designated trading centres meant that the royal palaces also gravitated to them so that the Mutapa’s could regulate and control the prices of commodities such as gold and cotton goods.

However, feiras become centres of regional power on the plateau of northern Mashonaland

Pikirayi believes the feiras were located in close proximity to the goldfields, but also that the: “regional location of the trading centres, particularly those in the eastern half of northern Zimbabwe, shows some regularity in terms of spacing.”

He believes that with trade being dominated by the Portuguese from the late 16th Century to the 17th Century their feiras became: “competing centres of economic and to some extent, political power” and this: “… challenged the traditional social formation in the region, that which controlled access to productive resources and specific territory and depended on agricultural production to support the subsistence needs of local population.” Agriculture was to some extent sacrificed in favour of gold as trading gold was a better potential source of wealth.

Long-term intentions of the Portuguese

From the beginning when the Portuguese started their Fort Sao Caetano at Sofala in 1505 their motivation was about trade and their intentions towards the Mutapa state were clear. They sought to conquer the Mutapa state and own the gold mines and dominate the ivory trade. They had seen the wealth that gold and silver had brought to the Spanish from their mines in Latin America and in order to dominate the spices trade of the east, they needed to offer gold bullion.

Initially they believed they could oust the Sofala merchants and dominate the gold and ivory trade, but when this proved problematic with the supply routes from Manyika being disrupted by unmanageable vassals and the Swahili traders easily outmaneuvered them and began using other routes from Quelimane and Angoche, they sought to penetrate the northern Mashonaland plateau themselves and conduct the gold trade at their feiras.

The martyrdom of Silveira in March 1561 and Portuguese understanding of the close relationship between politics and religion in the Mutapa state provided a useful justification for an invasion of the Mutapa state, but their early efforts were frustrated by:

- Francisco Barreto’s military expedition of 1569 being thwarted by the Tonga (Samungazi) resisting his advance on the Mazowe / Ruenya rivers and then disease and supply shortages forcing the force to return to Sena in 1572 without ever penetrating the Mutapa state

- Although the Portuguese had small trading settlements at Sena and Tete the Zambesi valley formed a formidable natural barrier which was difficult and dangerous for non-indigenous people to cross

- The Mutapa’s ambassadors possessed formidable negotiating skills and managed to fend off and mislead the Portuguese with largely empty promises for a considerable period of time.

Chivere Nyasoro (1550 – 1560) the Mutapa political / economic system is weakened by the Portuguese presence

Pikirayi believes the entire Mutapa political system was undermined by Portuguese interference and intriguing. In addition, the Mutapa monopoly on potential sources of wealth loosened as the trade network became more widespread with other chiefs and headmen participating in trade for their own benefit rather than the ruling elite’s benefit. The accumulation of individual wealth from gold trading: “in the region transformed Mutapa society and political power.”

Innocent Pikirayi adds that the effect of gold-mining: “was to exert excessive demands on the local population, which had to mine more gold, we are told, thereby investing more time in the activity at the expense of agriculture. This shift in productive and accumulation patterns also undermined the Mutapa political system as it meant reduced tributary inflows to the royal palaces.”[xxv]

There is little doubt that the civil wars and disputes with vassal states were precipitated and hastened by the arrival of the Portuguese who constantly interfered with the succession process within the Mutapa state. This weakening of the central power in the Mutapa state prepared the way for the Rozvi invasions when they saw an opportunity to overcome their rivals.

Succession disputes further weakened the Mutapa state

Local Budya people believe this settlement was built by Makate and his people in the 16th Century. Makate was said to be a powerful magic worker who used his charms to defeat his enemies. Another chief from the Zambesi valley, Nehoreka coveted this area, but was defeated. Nehoreka used his sister to spy on Makate and steal his charms. Without his charms Makate was easily defeated and withdrew into a nearby mountain Ruware RwaMakate where a hoe became stuck in the tunnel mouth into which they disappeared. Local people call the monument Tere RaMakate (Makate’s former stronghold)

Dr H.A. Wieschoff carried out the earliest scientific excavation as a member of the Frobenius expedition in 1929, but his report is brief and apparently he did a considerable amount of damage to the walling. He found some gold foil and a gold amulet, Chinese celadon ware, perhaps the result of trading with the Portuguese at Luanze. The same imported ware, from the fourteenth century, has been found at Great Zimbabwe. Also iron arrowheads and knives, copper bracelets and wound copper wire and graphite-burnished pottery, all of which is exhibited at the Interpretive Centre on site. [See the article Mutoko (or Tere) Monument under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Oral history relates that when a Mutapa died a natural death one of his chief ministers, the Nevinga, immediately took over as regent for three days, or until a successor was chosen, after which the Nevinga was expected to commit suicide.[xxvi]

Then wrapped in a cow-hide the dead Mutapa was placed on a wood trestle table in an airtight hut sealed with mud. They were called masanzas by the Portuguese who wrote: “thus hanging all the humidity of their bodies falls into vases placed underneath and when all has dropped from them and they shrink and dry up…[they are] to be taken down and buried, and with the fat and moisture in the vases, they say he [the succeeding Mutapa] makes ointments from which he anoints himself in order to enjoy long life…and also to be proof against receiving harm from sorcerers. Others say that with this moisture he makes charms.”[xxvii]

The chief wife and others lived in the area as guardians until their death when successors would be appointed. The future mhondoro (spirit medium) would also come to live at the masanza and might take the wives of the dead Mutapa as his wives.

Parallel to these rites, a successor would be identified. Dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental states: “the prince who succeeds to the throne is generally one of the eldest sons of the former king and his chief wives who are legitimate, and when they have not sufficient prudence to govern, the second or third son succeeds.”

However, Mudenge states that the Portuguese were aware that male sons were not always chosen and that oral tradition states that one brother succeeded another until they all had succeeded and then succession reverts to the son of the first brother in the previous generation.[xxviii] In fact, he states that of the 46 Mutapa successions, there were probably only 6 father-son successions.

Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu (1560 – 1589)

Chivere Nyasoro (1550 – 1560) was succeeded by his son Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu (1560 – 1589) which was specially negotiated as he was not the eldest son. Then Gatsi Rusere (1589 – 1623) was succeeded by his son Nyambo Kapararidze (1623 – 1629) but only after his uncle Mavhura Mhande claimed to be the Mutapa which led to civil strife and Portuguese intervention. Mavura Mhande (1629 – 1652) then became the Mutapa and was succeeded by his son Siti Kazurukamusapa (1652 – 1663) Between 1692 to 1902, there is probably only one case of a son succeeding his father – Kandeya III succeeded his father Kataruza in 1868.

Very often the succession was determined by force or by powerful allies – the Portuguese or later the Rozvi rulers. This became a major weakness for the Mutapa state and succession wars probably contributed more than any other factor to its downfall.

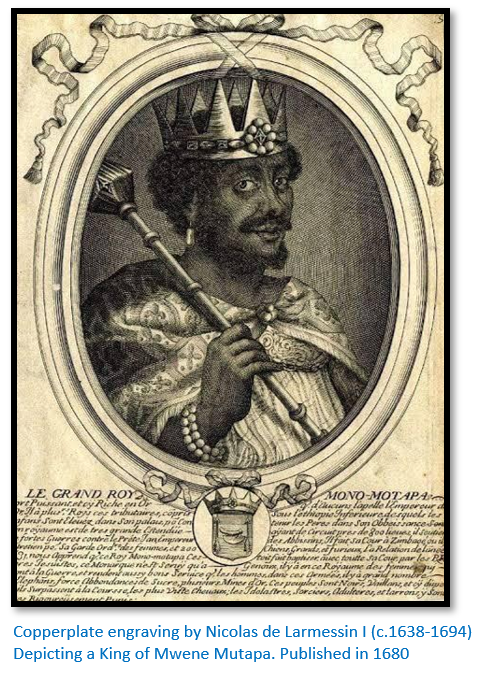

Royal regalia

Portuguese sources claim: “The said king [Mutapa] uses two insignia, one being a small hoe with an ivory point [handle] which he always wears in his girdle to show his subjects that they should cultivate and profit by the land, so that they may live in peace on what they obtain from it, without taking another’s property; the other consists of two assegai’s, showing that with one the king administers justice and with the other defends his people.”[xxix]

The Mutapa’s chief ministers / officers

Routine matters of state at court were dealt with by the Council (Dare) made up of the immediate advisers of the Mutapa, personally chosen on his succession, either members from specified families where demanded by custom, or on account of merit or friendship. These might include:

Nengomasha – governor of the provinces

Mukomohasha – captain-general of the armies

Ambuya – chief major-domo / steward

Nyandovo – chief musician

Nyarukawo – captain of the advance guard in war

Mbokorume – the Mutapa’s right-hand man

Nehonho – chief door-keeper

Mangwende – chief wizard (Nganga)

Netambe – the Mutapa’s herbalist

Nengomasha

In the 16th – 17th Centuries the Nengomasha appears to have been the first minister at court, but in later periods they seem to have lost their rank as the second most powerful notable in the state and the role remained prestigious but confined to a ritualistic role of guardian of the royal graves. Their former function was divided between two persons, the Nevanje or successor to the ruling Mutapa and the Nevinga, or chief minister. The Nevanje could be a brother, a son or a brother’s son of the ruling Mutapa and the post of Nevinga seems to have disappeared in the 19th Century.

Mukomohasha and Nyarukawo

The Mukomohasha is described as captain of the armies of the Mutapa, but in the 16th Century was also known as the ‘general and captain of the gates of the Kingdom.’ This was because Hondosaka in the east was the outer province which anyone coming from Tete had to pass through first before entering the inner parts of the state, in effect a border province. Later the Portuguese trader in charge of the feira at Massapa would be given the honorary title of ‘captain of the gates.’

Rezende in the Estado da India wrote: “this emperor {Mutapa) is in the habit of appointing a captain-general who is the second person, after himself, and he's called Macomoana (Mukomohasha) to reside in the lands of Botonga, at a place called Condessaca (Hondosaka)…the negroes of these parts…publicly assisted Caprasine (Kapararidze) in his wars.”

Mufenge states that the Mutapa state did not have a standing army so during peacetime the chief function of the Mukomohasha and Nyarukawo was to advise the Mutapa on military affairs.

Ambuya

The third office was that of chief steward and it was his duty to name the chief wife of the Mutapa known as Mazvarira (Mazarire)

In the 18th Century the chief steward was known as Nenzou (owner or keeper of the elephants) It was his duty to receive all the presents brought to the court, he was also in charge of the fazenda (trade goods) i.e. cloth and beads used as salaries for the Portuguese garrison at the Mutapa court which was paid by the Portuguese. The Nenzou was in charge of the Mutapa’s ivory and acted as the royal treasurer in charge of court finances.

Nyandovo and Nehonho

These two important posts were held by different persons. The chief musician was in charge of a large troupe of court musicians. The chief doorkeeper had keepers of the gates who were part of his usual entourage. Nobody could see the Mutapa without passing through the gates and explaining their business to the doorkeepers.

Mbokorume

Often the son-in-law or brother-in-law of the Mutapa and as his right-hand man a position of great confidence with absolute loyalty expected.

Mangwende and Netambe

These religico-magico roles were always represented at court with the Mangwende as the chief Nganga or diviner. Netambe was the chief herbalist and keeper of the royal spells and unguents and took a major role in the burial rites of dead Mutapas. Many of the persons originally filling these roles came from the Tonga / Sena area in the Zambesi valley until the Mutapa state moved east into Chidima where there was a stronger Tavara influence.

Mudenge asks whether each of the above officials who were all titled ‘kings’ in the 17th Century resided at court, or in their kingdoms? Antonio Bocarro describes their kingdoms and goes on to say: “Besides all these there is also a larger and principal kingdom, which is that of Mokaranga, where the Monomotapa resides with his court and most of these lords or their sons, of whom the Monomotapa makes use” so it appears they were resident at the Mutapa’s court as he goes on to say that when the Mutapa yawned, sighed, coughed or spat the officials would praise him saying: “thou art the lion, the leopard, the elephant, thou the invincible one, the mighty one, the immortal one” and clapped their hands.

Mudenge also discusses in detail the Mutapa’s other followers including bodyguards, musicians, dancers and jesters, pages, valets and cooks, and the royal wives (P99 – 110) which I have omitted.

Fr. Monclaro’s description of the system of rulers

Although, I have already said something of this barbarous people, I think it well to devote a chapter in itself to their customs and principal affairs, according to what I have seen myself or learned upon trustworthy information. The greater part of this Kaffraria is governed by fumos and petty rulers, and though it has powerful kings whom it obeys, it has nevertheless these fumos and headmen by whom the people are governed.

The fumos near Sena are Kaffirs, natives of the country, and very often the lowest are elected to this dignity. Most of them are forced against their will to accept the office, for when one has cows, millet, or naqueny which he can give them and spend, they elect him fumo, and his dignity lasts as long as he has anything to spend. When they have eaten up his property, they cast him out of the office, and pre-eminence is the most that they give him.

When an outsider has to speak to these fumos, he can only do so through others, and the word is passed through three or four before it reaches the fumo, even though he understands it. All are on mats in his presence, and he alone is seated on a quite which is a sort of small three-legged stool, and before they speak to him they clap their hands a little. They have great ceremonies among themselves, and no council is held without the fumo, who is often kept rather for ceremony than for any substantial obedience shown to him. The sons of these fumos are held in honour among them, though few care for a dignity which entails such loss, but they are forced to take it by those who bestow it on them.

Father Manuel Barretto noted that the Mutapa state had wards (matunhu) with: “their own names and limits, which are called moganos, and these territories... had their own fumos or petty kaffir kings.” So even in the 16th Century wards were divided into clearly marked villages each under a village head.

Vassal States

It is clear from Portuguese accounts that in the Mutapa state some territory was under the direct control of the Mutapa himself, but much territory was under the control of sub-rulers who enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy but were obliged to pay annual tribute to the Mutapa ruler in the form of cattle, gold, iron and copper as an expression of political loyalty. In the same way some sub-rulers under the Mutapa himself were obliged to visit the court and pay homage; other sub-rulers were within the state structure but had more sovereignty and did not visit the court. Vassal rulers who defaulted risked severe penalties, for example, being forced to drink poison as a test of their loyalty.

Oral tradition and contemporary Portuguese accounts name the more important territories as the Lower Zambezi Tonga country, Barue (Inhamior) Manyika, Uteve (Quiteve) and Dande (Sedanda) Chikanga and Biri were at various times vassal states of the Mutapa. Mutapa rulers as well as the Portuguese accounts naturally tended to exaggerate both the power and the boundaries of the Mutapa state. For example, sovereignty is frequently claimed over the Torwa state (Butua) in the southwest of the plateau, but this seems unlikely because of the distances and that no conflict is reported between them in the late 15th / early 16th Centuries.

Over these is the Monomotapa, who is like a king, both in the obedience rendered to him and in the mode of succession, because his eldest son inherits. He is very powerful and has many leagues of territory and kings and great lords for his vassals. Of these, one is the fumo Pango, who also governs as a king, and they say that he can bring more than seventy thousand men into the field.

He has also for vassal the king of Butoa, where they say there is a great quantity of gold, and his territory is situated in the direction of the Cape. Many cattle come to us from this kingdom, and it is said that they are very plentiful there.

The king of Manyika is also his vassal. He is less powerful in land, his kingdom extending only twenty or thirty leagues. It is full of mountain ranges, and therefore very strong and difficult of conquest, even by the forces of the Monomotapa. They say that it contains much gold and when the country is at peace the Portuguese go and trade there, both from Sofala and from Sena. There is a great scarcity of provisions in the country. The Kaffirs there make much use of poison: the king is half a Moor and half a wizard, and they have learned its use from those wicked people.

The Mongazes are also vassals of the Monomotapa and pay tribute to him. There are also many other lords in the interior who are subject to him, of whom I had no special information.

Religion

Mudenge quotes Alpers: “the key integrative factor in the Shona political system was religion. As Mambo, the Mwene Mutapa was the ultimate religious authority in his kingdom, for he alone could communicate with the spirits of his ancestors.”

Damião de Goes who wrote Gloriosa Memoria in the 16th Century states the Shona: “do not make or worship idols, but believe in one God, the creator of all things, whom they adore and to whom they pray.”

But Fr. Monclaro states the Shona were: “lacking all manner of worship and knowledge of God” but concedes later: “some give to God the name of Mulungo, but all this in much confusion, darkness and obscurity.”

Later his clear prejudices are evident: “These are the customs of the Kaffirs. Their sorceries are many, and of many kinds, by which the devil deceives them, and if they have any form of worship it is rendered to the devil by these spells. These people are very unfit for baptism, and even those who are brought up amongst us and made Christians leave us every day and return to their own people, for they value their own customs very highly; and, as I have said, they easily turn Christian and easily leave Christianity, because they do not understand the meaning of it.”

In the 17th Century Manuel Faria e Sousa claimed the Shona: “have no religion, nor idols, but acknowledge one only God. They believe their kings go to heaven and call them Muzimos and call upon them in time of need as we on the saints.” Bocarro repeats much the same: “they know that there is a God in heaven. They believe that their kings go to heaven and when they are there they call them Muzimos and ask them for whatever they require.”

In the 18th Century the Descripção do Império Monomotapa recorded: “the emperor and all the other people of the empire have the knowledge that there is one God to whom they give the name of Muzimo [Mudzimu] but they neither called them by name nor do they call on him in times of need and affliction. They worship all their dead emperors and it is these who are their Gods, some with more reverence than others.”

Mudenge states two elements of Shona religion stand out, the first being a belief in one God; the second is the veneration of ancestral spirits, or Mudzimu.[xxx] The Portuguese writers say more on ancestor veneration when they describe royal Mhondoro cults. Pachero says the first Mutapa Mhondoro was Matope, known by the name Nebedza who announced before he died that his spirit was immortal and after his death it would enter a lion or Mhondoro to enable him to work among and guide his people forever. Portuguese writers confirm Nebedza was the most senior of all the royal Mutapa Mhondoro.

Mudenge writes in detail about the royal Mutapa mhondoro cult and the Dzivaguru-Karuva cults that are not two separate religions, but separate ways for the Shona to approach God. The royal Mhondoro were particularly important within the Mutapa royal lineage and their Korekore (Karanga) followers while the Dzivaguru-Karuva cult is associated with the Tavara / Tonga who come from the north-east of present-day Zimbabwe.

Religion was an important factor revolving around the ritual consultation of spirits and royal ancestors who were consulted at shrines through spirit mediums, but it was by no means the only reason for welding the Mutapa state together. The spirit mediums also helped preserve the oral history by remembering the names and deeds of past Mutapas.

Military Forces

The Mutapa state survived in one form or another for about 500 years threatened by the Maravi peoples, as well as Portuguese prazo-holders and the breakaway kingdoms of Uteve (Quiteve) and Guruuswa, (Butua) so they had forces at their disposal, but the various figures quoted are contradictory and confusing.

The Mutapa state never had a standing army throughout the history of the state. The army came from the peasant farmers who volunteered whenever there was an emergency, but before declaring war the Mutapa convened a council of war (Dare reHondo) and messengers would be sent to the districts to summon the council members.

After the decision had been made to go to war, the Mutapa would appoint a relative to accompany the Mukomohasha and Nyarukawo as his representative. An announcement of a declaration of war was done by beating the war drums as in every chiefs’ district there was a special drum beaten to summon the people, sometimes a horn was blown, or a gun fired. Criers would be sent to tell the people to assemble.

The forces would be assembled in regiments from 200 – 1,000 strong and each under a field commander. Fr. Monclaro says each regiment had its own banner / badge representing various figures like oxen, elephants and other beasts, all being big and made of straw and covered with cloth: “by these badges are known their captains and rulers with their men in war.”

Fr. Monclaro says that in battle they favoured fighting in an open field, used no ambushes: “nor did they resort to cunningly hidden snares, or attack by night, but rather at dawn.” First they sent out scouts marimbirimbi, for reconnaissance work. The remaining forces were divided into the murumo, literally the mouth, which was made up of the two flanks or ‘horns’ of the vanguard whose role was to envelop the enemy. The main body of fighters were the guru (guro) literally the ‘big one.’

Their weapons were mainly bows and arrows, assegais, clubs (svimbo) shields and battle-axes. Before going into battle the warriors were doctored by the diviners (Nganga) Before the battle, in order to bolster their own morale and intimidate the enemy, they chanted war songs, beat drums and blew horns. Their numbers are said to vary from 100,000 (Fr. Monclaro) to 300,000 (Fr. Luis Frois) warriors. It’s quite possible that the Portuguese sources exaggerated the numbers to add to their victories or explain their defeats. As previously noted, the Mutapa did not have a standing army, but theoretically every man in the state could be mobilised.

Battles because of their close-combat fighting with battle-axes were often short and furious. Fr. Monclaro declares: “their sieges of any place are of short duration, three days at the most, it is said, because the land is so lacking in food…”

The time of year was also important and whether it was the dry or rainy season. Warriors were also cultivators and knew if they did not cultivate or harvest their gardens they would be in trouble the following season from famine.

Mudenge attributes the gradual break-up of the Mutapa state to political failures around succession and not to the lack of effective military structures and forces.

Foreign relations

The Mutapa’s ambassadors were called nhume and later mutumwa and mwanamukati. It appears that ambassadors would be chosen and sent on specific missions and were often chosen from court officials.

Dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental says the arrival of an ambassador at a Portuguese settlement was quite a spectacle: “First come, in front, certain drummers and players of other instruments, together with certain dancers, all singing and playing as they march, deafening the surrounding country with their harsh and discordant voices, their heads ornamented with cock’s tail feathers. After them come the other kaffirs in single file, and after them the four mutumes in their proper order, he who represents the king coming last.”

Ambassadors might have some discretionary powers to negotiate on some issues, however major issues would need to be referred back to the Mutapa’s court.

Ambassadors carried special royal staffs or mibhadha as symbols of their office as a kind of laissez passer which gave them the king’s authority and meant they would not be harmed.

Portuguese ambassadors were exempt from some of the Mutapa court formalities: “[Portuguese] ambassadors who come to speak to him [the Mutapa] shall enter his Zimbaoe shod [in shoes] and covered, with their arms in their belts, as they speak to the king of Portugal and he shall give them a chair on which to seat themselves without clapping their hands, and other Portuguese shall speak to him in the manner of ambassadors and shall be given a kaross to sit upon.”

The main criteria for the ambassador’s post was knowledge of local customs and language for which consuls or agents were appointed. In the late 16th Century this role was symbolised in the office of the captain of Massapa or ‘Captain of the Gates.’ Although an officer of the Mutapa’s administration Dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental says he: “also receives from the viceroys of India power to act as judge and chief of all the Portuguese who frequent these kingdoms, and as such he gives judgment in all cases affecting Portuguese that are brought into court in these parts. The captain of Massapa in this office serves as agent in all matters between the Portuguese and Monomotapa.”

Portuguese garrison at the Mutapa’s court

During the 17th to early 19th centuries a Portuguese garrison was, from time to time, stationed at the Mutapa court. In theory to protect the Mutapa, but in practice too small and ineffectual to do that, but it did serve as a Portuguese listening post. The instructions to the captain-major in charge included: “the said captain major should take greater care to make himself the master of all the intelligence related to the interests of this state [Mutapa] and it’s commerce; advising, without delay, him who happens to govern these Rivers, of all and every movement of the said emperor, or of his decisions, as well as of his allies or enemies and whether the traders of Zumbo ought to pass through the territory of the same emperor on their way to that fiera.”

The captain-major was not to make any troop movement without first clearing it with the Mutapa to avoid any misunderstandings. In all his dealings with the Mutapa the captain major had to show great subservience: “As soon as the said captain major enters the Zimbaoe of Emperor Monomotapa with the due ceremonies and salutations [he should show] as much deference, attentions and submissions as are due to the legitimate sovereign whom he goes to serve…He should declare to him that he goes there sent by the Most High, Most Powerful, the Sovereign and Most Faithful King of Portugal to provide him with a guard as was the practise with past Emperors as a sign of our friendship and good alliance which we wish to have with him and for which that garrison is sent over there to be always at his disposal.”

The original garrison had 25 soldiers, a captain, lieutenant and sergeant until the governorship of Francisco de Mello de Castro when it increased to 33 soldiers with an added captain, lieutenant, sergeant, chaplain and interpreter. After the death of Mutapa Dehwe Mapunzagutu in 1759 either there was no garrison, or it was much reduced.

It’s clear the Portuguese garrison could never serve any military function to the Mutapa, it’s real purpose was as a Portuguese listening post providing a guard of honour to the Mutapa.

The Mutapa’s were diplomatically competent

Although the Mutapa state did not seem to have a minister of foreign relations, his ambassadors had the necessary competence and skill to negotiate with the Portuguese and surrounding states as shown by the way Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu

handled Francisco Barreto’s attempted invasion of the Mutapa state [See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Justice

We have Fr. Monclaros’ probably biased views: “There is no method or form of justice among them. They who have most are most powerful with princes whom they can bribe, and these order people to be stabbed with assegais and killed according to their will, because as they lack any form of worship or knowledge of God they lack everything else. Portuguese who have been there have related to me that they have been often chosen as judges in quarrels which had arisen among them, and even though they gave sentence against one, he who was condemned was quite satisfied, because he thought they had acted according to reason and justice, and this did not prevent him from choosing them as judges again in any other difference he might have.”

Clothing

Fr. Monclaro says: “Generally, they are all dressed in pieces of cotton cloth, but are poorly covered. These cloths are made on the other side of the river [Zambesi], and are woven on low looms, very slowly. I saw some at work near Sena. These cloths are called machiras and are about two varnas and a half long and one and a half wide. They gird these machiras round their bodies and cross them over the breast, and the rest of the body is uncovered.

They wear horns in their hair by way of finery, which are made of their own locks strangely twisted. These horns are in general use in all Kaffraria, and they shelter the head very well. They make one in the middle of the head, to which their hair is gathered up in very good order. They first cause their hair to grow long, by fastening pieces of copper or pewter to the ends of the locks, that the weight may stretch them, and thus they go with their heads covered with these little weights. When it has grown long, they take up some hair in the middle to make the largest horn, and fasten it with a kind of grass, braiding it in very neatly for a space and bringing it to a point where they leave a tuft unbraided. When this is done they make other little horns in good order, and these are very curious.

The women wear upon their arms and legs many bracelets of copper drawn very fine, and gold is also drawn very fine, and then made into bracelets. The Monomotapa sent eight of these to Francisco Barreto, as I will relate further on.”

Marriage and Family

Fr. Monclaro writes: “They have many wives, and the higher their rank the greater number they have. They say the Monomotapa has more than three thousand, and besides those at his court he has a great number on a farm, where they dig, sow, and do everything with their own hands, like the Galagas of Spain. He goes there and spends as much time with them as he likes, and once when he returned with a headache they say he ordered more than four hundred to be put to death, asserting that they had cast spells upon him. Among these wives there is always one who is the principal, and whose sons inherit. They are very credulous, variable, and inconstant. It happened while I was there that the king of the Manyikas died, and many of his wives killed themselves, saying that they must go and serve him in the other world. This I heard only from a negro who partakes a good deal of the Moor, and thus it came about that these women killed themselves with the pretext of a future life, for most of the Kaffirs think they have nothing to do but live and die, though some of them call God Mulungo, but confusedly and in darkness and obscurity…

…The method of marriage is to agree with the wife’s father and give him a certain quantity of goods, for the wives bring nothing to their husband, but the latter buys them from their fathers in the manner aforesaid. If they are vexed with them, they very easily repudiate them, and when they send them back the cloths they gave for them are also restored. They have no set words or form of marriage beyond taking possession of the wife and giving the cloth to the father, and thus with the consent of the father and the girl the marriage is completed, which signs seem sufficient to make it valid and natural.”

Food

The general food in Kaffraria is a paste of millet badly ground or pounded in their mortars, which are like the large mortars I have sometimes seen in Lisbon along the river and seaport. from their flour, which is beans crushed, they make cakes which they cook round the fire every time they eat, at dinner and supper, because when cold it is like metal, and cannot be touched. Of this flour they make a round mass as large as a man’s head, which they call enjunda, and bring it to the table; and many prefer it to the millet cake. They have also a large quantity of palm-oil, which is a penance to those who are not accustomed to its use. The wine is also from the palm and resembles mastic.

They eat the hens cut open along the back, without plucking or disembowelling them, and thus opened they place them on embers, and eat them without doing more than clean the ashes off the feathers. They roast sheep whole, skin and all, and eat them in this way, and capons in the same manner, of which there are many, and they are very good. There are but few fruits, and the best are some which resemble plums; they have no stone, but only small kernels or little seeds. They are called sangomas, are much better than those of India, and are very abundant in the thickets. They drink wine made of millet, or more generally of nacqueny, a vegetable resembling mustard.

The economic base of the Mutapa state

Mudenge believes these were in probable order of importance:

- Agriculture (sorghum and millet)

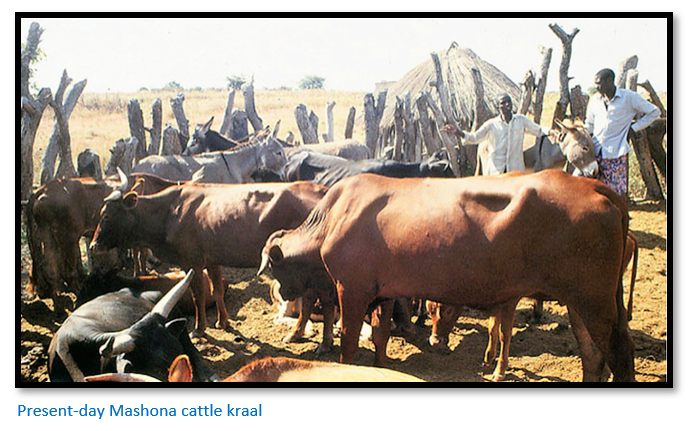

- Pastoral activities (cattle and small stock)

- Mining (gold, copper, iron)

- Hunting (ivory and hides, especially leopard)

- Trade (Swahili and later Portuguese traders)

- Tribute, taxation, presents

- Small-scale crafts and industries (pottery, basket weaving, cloth manufacture)

Agriculture and pastoralism

This was the dominant economic activity throughout the whole period of the Mutapa state and it could not have existed without them, and cattle were the most important. However it is not well-covered in the Portuguese accounts because this was not an area of great interest to them.

In the 17th Century Antonio Bocarro noted that the people: “will not exert themselves to seek gold unless they are constrained by necessity for want of clothes or provisions, which are not wanting in the land, for it abounds with them, namely millet, some rice, many vegetables, large and small cattle and many hens. The land abounds with rivers of good water and the greater number of the kaffirs are inclined to agricultural and pastoral pursuits, in which their riches consist.”

Cattle were the most convenient way that distant vassal rulers could pay tribute or give presents to the Mutapa, and his herds appear to have grown very large indeed. Usually they were kept away from the capital, the system under which a person keeps another’s cattle is called kuronzera in Shona. The keeper had the right to use those cattle but could not dispose of them without the Mutapa’s permission.

De Barros writes that people local to the Mutapa’s dzimbahwe paid their tribute through labour with: “a system of service instead of tribute, which is that all the officers and servants of his court and the captains of the soldiers, each with his men, must serve him in the cultivation of his fields or other work seven days in every thirty.”

This probably resulted in a significant surplus of sorghum (mapfunde) and rapoko, commonly known as African finger millet (rukweza) or bulrush millet (mhunga) that was stored at the royal court and would feed its large population.