Home >

Mashonaland Central >

Massapa (Baranda Farm) – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site in Mashonaland Central

Massapa (Baranda Farm) – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site in Mashonaland Central

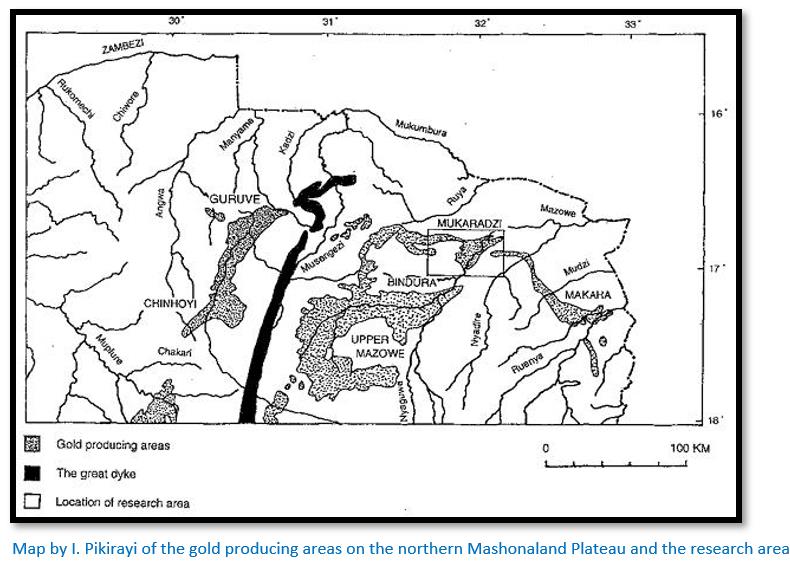

Innocent Pikirayi states that the feiras and other trading settlements established in the late 16th and first half of the 17th centuries were the main contact points between the Portuguese and the local south eastern African communities in the Zambesi Valley and the northern Mashonaland Plateau, gold and ivory being the main commercial interests for the Portuguese.

However the Massapa feira was different to all the other feiras as not only was it located close to the gold-bearing regions at the Mukaradzi river but it was also located at or near to the Mutapa royal court or zimbaoe. This made the Portuguese frequent visitors to Mutapa royal courts, where, during the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, they tried to influence the political and economic course of events.[i]

Portuguese references to the Mutapa’s royal court

Portuguese accounts of the Mutapa state capitals as zimbaoe describe many of the events and rituals of the royal court, but understandably are rather vague on their locations as no maps existed. The earliest reference to a royal capital appears in a 1506 letter from Sofala in which a clerk mentions a city: “called Zimbany…which is big and where the king always lives” where the houses are made: “of stone and clay and very large and on one level.”

Duarte Barbosa[ii] a Portuguese writer and officer from Portuguese India (between 1500 and 1516) sailed on Ferdinand Magellan's voyage of circumnavigation of the world in 1519 – 21 and left an account of the countries bordering the Indian Ocean and their occupants, saying

in reference to the Swahili gold trade that Zimbaoche was 15 – 20 days travel inland: “in which are many houses of wood and straw, which is of heathens. In which the king of Benametapa frequently resides and from it to Benametapa is 6 days journey, which road goes from Sofala inland towards the Cape of Good Hope. In this same town of Benametapa is the usual residence of the king, in a very large place, whence the merchants take the Sofala gold which they give to the Moors without weighing for coloured cloths and beads which among them are most valued.”[iii]

A c.1631 document from the Archives of Propaganda, Rome describes a zimbaoe as “a royal city of Monomotapa, very near the above named Mazapa [Massapa] It is said to be a large city. There is no church, but there are many Christians, who are refugees compelled to live there.”[iv]

João dos Santos in Ethiopia Oriental writes there was a church in the late 16th century: “This Monomotapa [Gatsi Rusere] admitted our religious into his kingdom and gave them leave to build churches and establish Christianity there, as they at present do, and they have also built three churches in the principal places of his kingdom, in Masapa, Luanze and Bocuto, where many Portuguese reside.”[v]

More detailed Portuguese accounts of Massapa

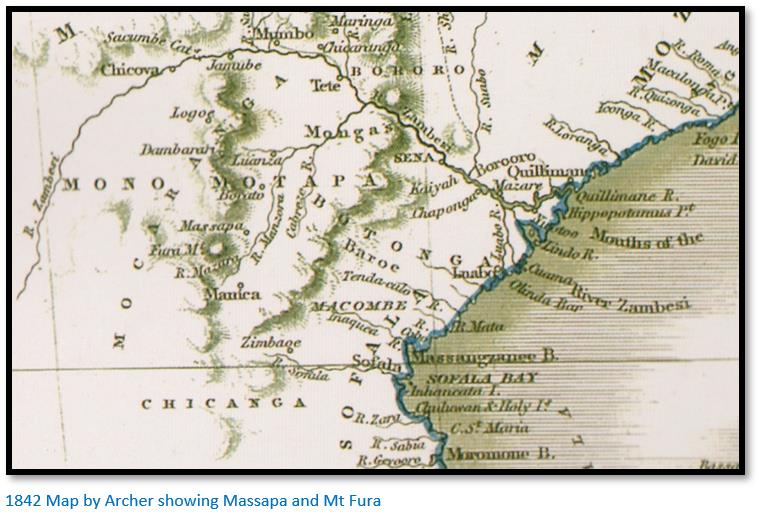

Diogo de Couto in Da Asia writes: “Massapa is the third market, which is reached by travelling along the river Masouvo [Mazowe] and is fifty leagues from Tete. This market is very extensive and very rich.”[vi]

João dos Santos states Massapa is located close to Mount Fura (Mount Darwin) “Close to the town of Massapa is a very high and grand mountain called Fura from which there is a view of Monomotapa.”[vii]

After the mid-16th century it is apparent that Mutapa royal palaces on the northern Mashonaland Plateau were no longer being constructed using dry-stone walling. João dos Santos, who was a missionary in Tete in the Zambezi valley from 1585 to 1595 observed that “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass.”[viii]

António Bocarro (1594 - 1642) was a Portuguese historian and geographer and continued the Decades of Asia begun by João de Barros and Diogo do Couto and gives a more detailed description of the Mutapa’s court: “the dwelling in which the Monomotapa resides is very large and is composed of many houses surrounded by a great wooden fence, within which there are three dwellings, one for his own person, one for the queen and another for his servants who wait upon him within doors. There are three doors opening upon a great courtyard, one for the service of the queen, beyond which no man may pass, but only women, another for his kitchen, only entered by his cooks.”[ix]

Francisco de Sousa wrote that Massapa was a league in circumference (>6,000 metres) with the houses built within a stone’s throw of each other and that the Mutapa and his family lived within nine compounds. He does not state the size of the population, only that it was very large.

Antonio Bocarro adds that Massapa is located: “four leagues from the Manzovo river, fifty leagues from Tete and ten leagues from Bokuto. It is the principal and largest of all the markets in Mukaranga.”[x]

Diogo de Couto adds the richest mines were located close to Massapa in an area called Fura.[xi]

There are many references to the different Mutapa capitals that shifted often with each succession as natural resources such as timber or water eventually became short. Clearly there was no way these early historians could provide more geographical detail on the locations of these zimbaoe other than referring to nearby physical features such as rivers or mountains and it should be remembered that most of these accounts were from second-hand sources.

Portuguese Feiras on the northern Mashonaland Plateau

By the late 16th century the Portugues had established feiras at a number of locations including Dambarare,[xii] Luanze (Ruhanje)[xiii] Makaha, Bokuto and Massapa.[xiv]

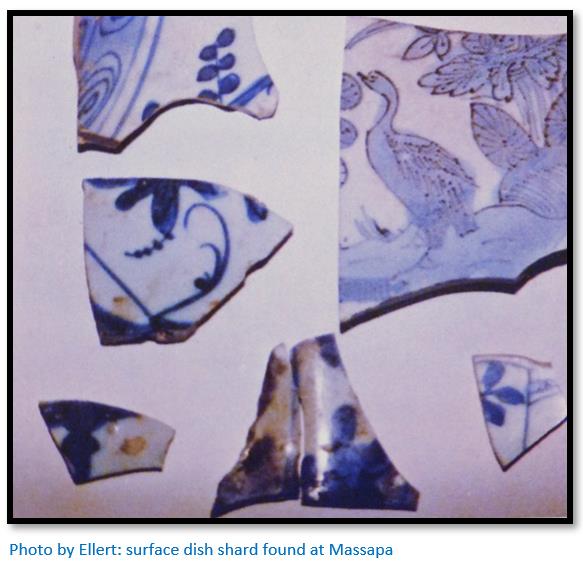

The feiras of Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) and the trading settlement of Maramuca (Rimuka) were excavated by Peter Garlake; the trading settlements at Angwa (Ongoe) were surveyed by Elizabeth Goodall. They were all characterised by rectangular earthworks that surrounded a central storehouse / residence and all revealed surface sherds of imported Chinese, Persian or Portuguese ceramics and Indian glass trade beads indicating a previous Portuguese presence.

Of the trading conducted within the Mutapa state João dos Santos writes: “After merchandise has left Tete by land…it is carried over a great part of the kingdom of Monomotapa to three villages situated in this Mocaranga, at some distance from each other, which they call fairs. They are Massapa, Luanze and Manzovo, in which places the residents of Sena and Tete have houses called churros where they store their merchandise and from which they sell it and send it to be sold throughout the country. The principal of these market places is Massapa, where a Portuguese captain always resided, who is elected by the Portuguese of these rivers, the appointment being confirmed by Monomotapa…”[xv]

Massapa feira

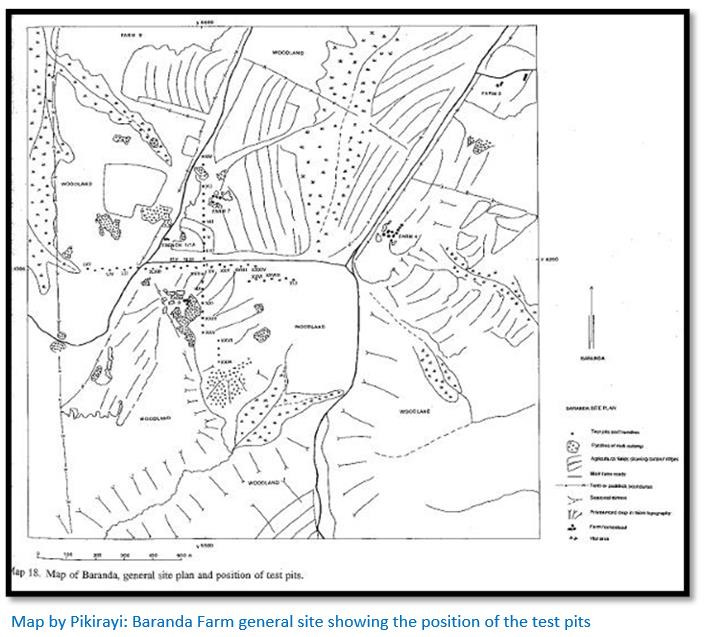

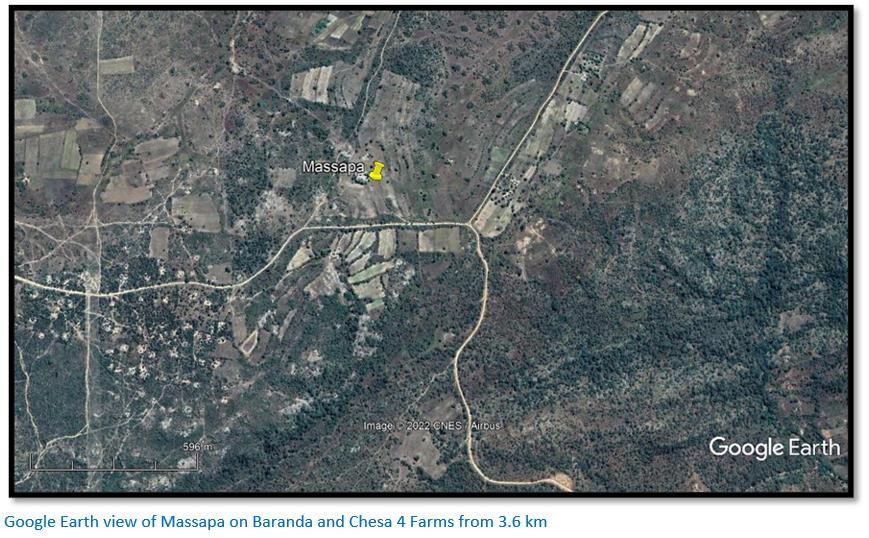

At Baranda Farm and Chesa Farm 4 approximately 8 km east of Mount Darwin town is the site of the former Mutapa royal capital. Innocent Pikirayi estimates the zimbaoe was over a kilometre in diameter. The site surveyed by Pikirayi measures 1,200 × 1500 metres, covering an approximate area of 180 hectares, spilling over into adjacent farms.[xvi]

There are no physical structures visible at Baranda Farm. However the presence of pole-impressed dhaka points to the Portuguese descriptions of the buildings: “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass” being correct. Centuries of agricultural ploughing have left the site stripped of any visible historical remains as Pikirayi’s photo below shows.

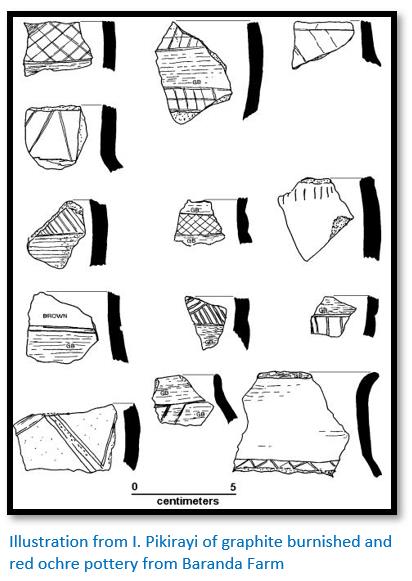

Much local pottery has been found as well as imported ceramics and glass trade beads. Pikirayi states the locally manufactured pottery: “resembles that from the last phase of the Great Zimbabwe occupation, suggesting a Great Zimbabwe Culture community based in the heartland of the Mutapa state, with extensive and lucrative trading contacts with the Indian Ocean trade. Their prosperity was based, in part, on the gold-rich Mukaradzi river Valley.”[xvii]

The gold trade is clearly key to the location of the Mutapa zimbaoe at Baranda Farm site. Pikirayi writes: “The settlement of Baranda was geared towards gold processing for export as seen from the ceramic crucibles and metalworking found on the site.”[xviii]

Satellite sites within a 5-km radius of Baranda

Pikirayi believes that these sites within a close distance of Baranda Farm would have served as satellite settlements to the Mutapa’s royal court providing additional and supporting functions to the main settlement. Their presence is indicated by similar local and imported pottery.

The Portuguese presence at Massapa

The Massapa feira appears to have been located at the zimbaoe on Baranda Farm and that this was the Mutapa royal capital at the core of the state in what the 17th century historians and cartographers called Mukaranga.

The Massapa feira being integrated into the Mutapa royal court became politically important and the Portuguese appointed the ‘Captain of the Gates’ to coordinate their activities. He would have been a Portuguese soldier or a trader of great influence and would have been appointed to this position by the Governor of Mozambique Island. He had control over all Portuguese traders who lived and travelled in Mukaranga.

Antonio Bocarro declares: “There also resides at Massapa a Portuguese Captain who is called the Captain of the Gates, asked for by the Monomotapa, and appointed by the traders by the order of the Captain of Mozambique. Through this Captain the Monomotapa treats of all that he thinks proper or that transpires between his people and the Portuguese and messages are sent through him. He is called the Captain of the Gates because no one can go inland from Massapa or confer with the king without his licence.”[xix]

Archaeological finds from Baranda Farm

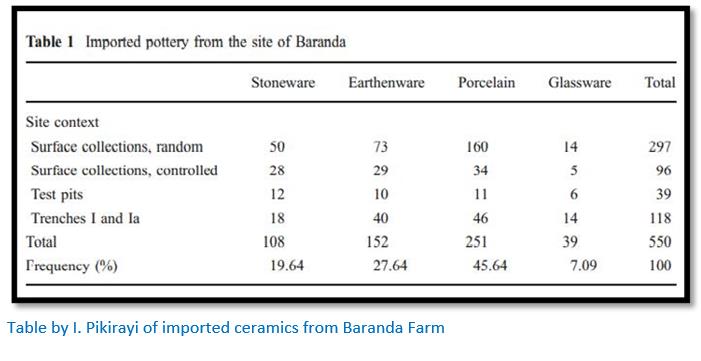

Surface collections, test and trench excavations were carried out under controlled conditions by the Archaeological Unit of the University of Zimbabwe at Baranda Farm and a substantial amount of imported pottery, which included Chinese stoneware, Persian earthenware and Chinese blue on white porcelain was uncovered as the table below shows:

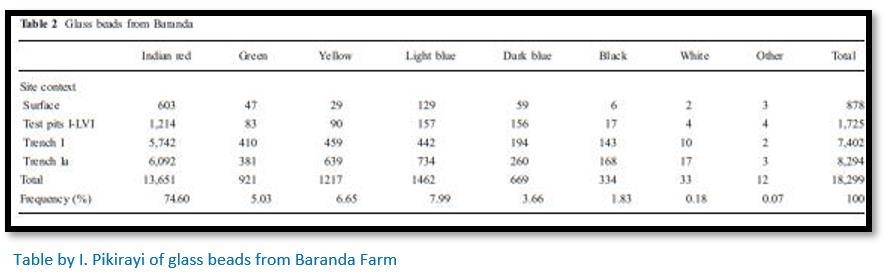

Over 18,000 glass trade beads from the Indian sub-continent in shades of red, green, yellow, light and dark blue, black, white and brown were found all dating to the 16 – 17th centuries pointing to a substantial international trade.

Pikirayi writes that the pottery from the Baranda Farm site: “has clear affinities with that of the Zimbabwe Culture, as seen from the use of rolled rims, graphite burnishing and red ochre. A significant development in the assemblage was the manufacture of bowls, not very common at Great Zimbabwe and other earlier sites.”[xx]

It needs to be emphasised that the graphite-burnished pottery confirms the carryover of the Great Zimbabwe Culture.

Other finds at Baranda Farm

The excavations carried out by Pikirayi and his colleagues from the Archaeological Unit of the University of Zimbabwe found, in addition to the pottery and beads, copper wire, iron implements, lumps of slag, grinding equipment, ceramic crucibles, pebbles and spindle whorls, as well as the bones of wild and domestic animals.

The spindle whirls point to the manufacture of local cloth.

Decline of Massapa feira

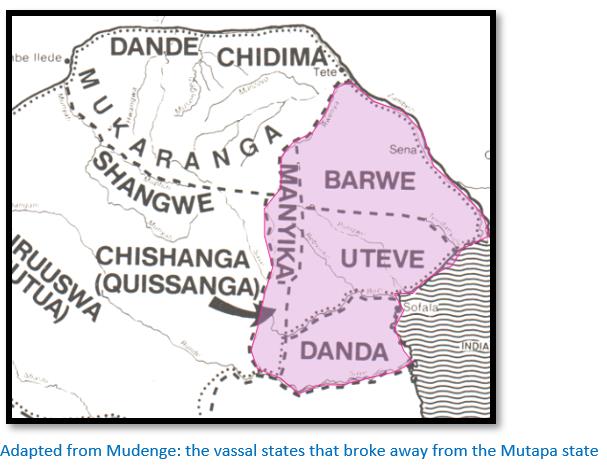

From the 1620’s in a development that parallels the decline of the Mutapa state brought about by the vassal states of Barwe, Quiteve (Uteve) Danda and Manyika rebelling against Mutapa rule and feuds between ruling families jostling for power, Massapa feira began to lose its importance.

Mutapa Gatsi Rusere was greatly angered by Portuguese political scheming and this caused a worsening in Mutapa-Portuguese relations. This was aggravated by Estêvão Ataíde, the General of the Mines of Monomotapa failing to pay the curva (kuruva) in 1610. Instead he sent a trader named Diogo Carvalho to question Gatsi Rusere about the Chicova silver mines using future payment of the curva as an inducement.

Whilst staying at Massapa, Carvalho supervised the building of an earth stockade, called a chuamba that was: ”only a palisade of stakes, filled up inside with earth, allowing those within to fight undercover. The stakes are of such a nature that when they have been two or three months in the ground they take root and become trees which last many years.”

However Carvalho foolishly allowed himself to get embroiled in local politics that resulted in the killing of some of the Mutapa’s supporters. In retaliation Gatsi Rusere declared an empata against the Portuguese seizing their goods and forcing the traders to leave for the safety of Tete. The Mutapa sent an army against Portuguese at Chikova who were searching for the silver mines.

Estêvão Ataíde was recalled to Mozambique Island in 1613 and accused of neglect of duty and incompetence and replaced by Diogo Simões Madeira. Madeira quickly proposed a peace treaty and the curva was paid bringing a temporary peace.

In 1619 Nuno Alvares Pereira was appointed General of the Mines of Monomotapa but proved no better than his predecessors in improving Mutapa-Portuguese relations. Once again the curva was not paid until 1628, yet Portuguese traders continued to trade despite this breach of agreement.

With the death of Gatsi Rusere in 1624, these rebels took control of Massapa, killing the Portuguese representative (Captain of the Gates) stationed there. Following the death of Gatsi Rusere in 1623 his son Nyambu Kapararidze succeeded as Mutapa. However increasing civil war and lawlessness created poor conditions for trading and the Massapa feira seems to have declined as a trading centre.

On 17 November 1628, Mutapa Nyambu Kapararidze (1623 – 1629) killed Pereira’s emissary, Jeronimo de Barros, in a rage because the curva (kuruva) – the tribute and customary payment had not been paid. The Captain of the Gates, Andre Fernandes, who had escorted the emissary, defended himself until nightfall and then managed to flee from the Mutapa’s zimbaoe to the Massapa stockade, during a torrential rainstorm.[xxi] Father Louis writing to his provincial in 1630 stated that the Mutapa’s zimbaoe was a night’s journey away from Massapa.

At the stockade Fernandes rallied his garrison and defended themselves against the Mutapa’s forces for seven days. Once again Portuguese traders fled for the safety of Tete. Pereira was suspended to be replaced by Diogo de Souza de Menezes who launched a military campaign against Mutapa Kapararidze. In a second battle near the Luanze feira many of the Kapararidze’s forces switched sides for his rival Mutapa Mavhura Mhande who was installed as the new Mutapa. Civil war continued but by 1632 Kapararidze had fled into exile north of the Zambesi.

The decline in the importance of Massapa in the 1630’s continued as the Mutapa state experienced civil war leading to a breakdown in control accelerated by conflict with Portuguese estate (prazo) holders in the Zambesi valley and their Chikunda proxy armies. In the 1680’s the Portuguese attempted to fortify their feiras with bastions in anticipation of an attack by the Rozvi. The civil unrest and disease caused many deaths and local people left causing serious depopulation within the former gold-producing regions.

The potential of conflict drove many of the Portuguese traders to leave for the relative safety of Tete and Sena leaving the so-called Canarins at the feiras and trading settlements. The Canarins were Konkani people from Goa and were recruited because they were Christian Indians. Ellert states that they built good trade relations with the Africans and some had experience at gold mining from India, so that gold production actually increased at Angwa and Chitomborwizi.[xxii]

But their attempts at defence were in vain and Changamire Dombo unleashed his army in a devastating attack on Dambarare feira and then on the Massapa feira in 1693 which he found largely abandoned.

Loopholed dry-stone structures on Mt Fura (previously Mount Darwin)

The political insecurity brought about by Portuguese interference in the Mutapa state resulted in civil war from 1600 – 1610 between rebels and the ruling Mutapa Gatsi Rusere. For their own and security and to reassure Gatsi Rusere of their support the Portuguese built a fort near Massapa to defend a small garrison.

Either one of the dry-stone walled and loop-holed forts on the south bank of the Mukaradzi river (3 km south of Baranda Farm) or on the north-eastern flank of Mt Fura itself (6 km south-south-west of Baranda Farm) is probably where the Captain of the Gates and his small Portuguese garrison resided. Both would have had a direct line of sight with the royal capital to their north.

Mount Fura is believed to be where the Mutapa Gatsi Rusere (1589 – 1623) is buried and the hill is a shrine for many local people.

Two roughly built stone enclosures with loopholes on Chenguruve hill, about a kilometre to the southwest, attest to the violent episode during the seventeenth century, which might have resulted in the decline of the Massapa feira.

Eric Axelson in the 1950’s conducted surveys in the Mount Fura region and drew attention to the existence of the dry-stone enclosures, which he believed, because of the loopholes, pointed to a Portuguese origin. Further surveys by Pikirayi and the Archaeological Unit of the University of Zimbabwe have recorded over 100 similar stone structures with irregular, semi-circular or oval outlines.[xxiii]

Radiocarbon dating of sample sites would indicate late 16th to early 17th century occupation. Pikirayi believes they belong to a different architectural tradition from the Mutapa state.

The surveys conducted by Pikirayi and by the Archaeology Unit of the University of Zimbabwe identified 19 loopholed structures on Mount Fura itself.[xxiv]

The rock material itself makes the neat wall building associated with Great Zimbabwe Culture impossible, the wall faces are always rough and no coursing is possible.

Pikirayi writes that loopholes are a consistent feature of the enclosures wherever they are sufficiently well-built and preserved. They are commonly 20 cm square and framed with small slabs and often within a metre or two of any entrance.

Pikirayi believes that the loop-holed structures are associated with the wars of the late 16th / early 17th century. They may have been used as fortifications but their locations on Mount Fura and the difficult access make them unlikely to have served as a Mutapa capital. They were built during a period of conflict and not for any prestige purposes. Pikirayi also believes they were not built by the Mutapa state and that it is more likely they were constructed during the civil wars by people from outside the Mutapa state.[xxv]

References

H. Ellert. Rivers of Gold. Mambo Press, Gweru, 1993

S.I.G. Mudenge. A political History of Munhumutapa c1400 -1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1988

I. Pikirayi. The Zimbabwe Culture, Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States. AltaMira Press, 2001

I. Pikirayi. Palaces, Feiras and Prazos: An Historical Archaeological Perspective of African–Portuguese Contact in Northern Zimbabwe. African Archaeological Review 26(3): September 2009

I. Pikirayi. Archaeological Identity of the Mutapa State. Societas Archaeologica Upsaliensis. Uppsala 1993

Notes

[i] Palaces, Feiras and Prazos, P164

[ii] His Book of Duarte Barbosa is one of the earliest examples of Portuguese travel literature.

[iii] Theal : History and Ethnography of Africa south of the Zambesi, Vol 1, P95-96

[iv] Ibid, Vol 2, P439

[v] Ibid, Vol 7 P288

[vi] Ibid, Vol 6, P369

[vii] Ibid, Vol 7, P275

[viii] Ibid, Vol 7, P275

[ix] Ibid, Vol 3, P356-7

[x] Ibid, Vol 3, P354

[xi] Ibid, Vol 6, P366

[xii] See the article Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xiii] See the article Luanze Earthworks and Church under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xiv] See the article The Portuguese Feiras and trading settlements of the 16th – 17th century on the Northern Mashonaland Plateau and Manicaland under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

[xv] Theal : History and Ethnography of Africa south of the Zambesi, Vol 7, P270-3

[xvi] Palaces, Feiras and Prazos, P170

[xvii] The Zimbabwe Culture, P177

[xviii] Palaces, Feiras and Prazos, P172

[xix] Theal : History and Ethnography of Africa south of the Zambesi, Vol 3, P354

[xx] The Zimbabwe Culture, P172

[xxi] Theal : History and Ethnography of Africa south of the Zambesi, Vol 2, P427-8

[xxii] Rivers of Gold, P29

[xxiii] Palaces, Feiras and Prazos, P175

[xxiv] Archaeological Identity of the Mutapa State, P179

[xxv] Archaeological Identity of the Mutapa State, P119

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: