Home >

Mashonaland Central >

How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State

How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State

Background

Much of the material quoted below is sourced from the comprehensive articles by Ana Roque called Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean Under Portuguese Rule and also The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade – both articles are a great source of useful information.

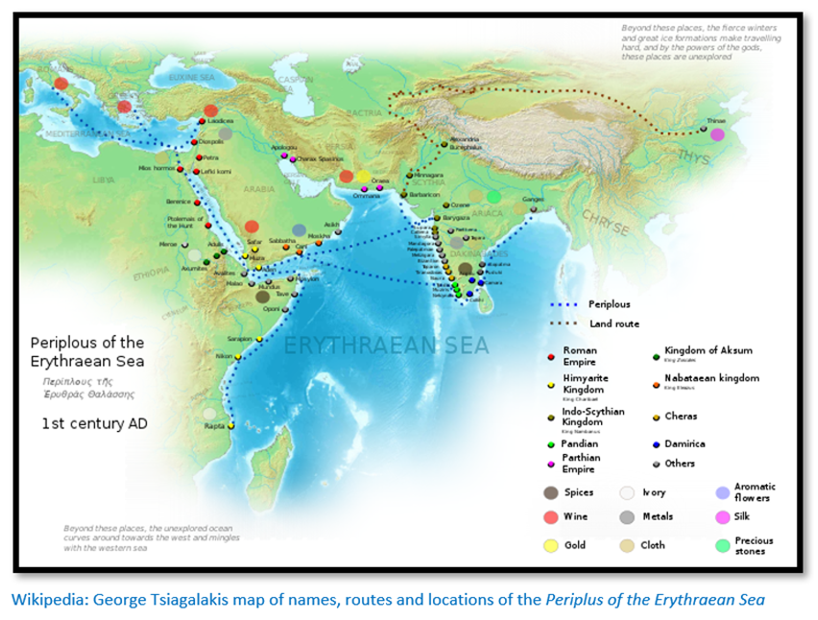

When Bartolomeu Dias rounded the southern tip of Africa in 1488, the Portuguese had found the sea route to the Indian Ocean. At this time Arabs and Persians controlled the Indian Ocean trade. Triangular trade routes existed between the Red Sea and Persian Gulf, the west coast of India and East Africa. Along the East African coast a chain of small Muslim trade ports reached from Mogadishu in the north to Sofala in the south.

The Portuguese plan to dominate the gold trade with their sea power

They believed that they could by force of arms dominate the Sofala trade network and obtain the gold mined by the Mutapa State and its vassals, but they were quickly forced to change their strategies when confronted by the reality of an already existing and well-organised commercial trading network controlled by Swahili merchants.

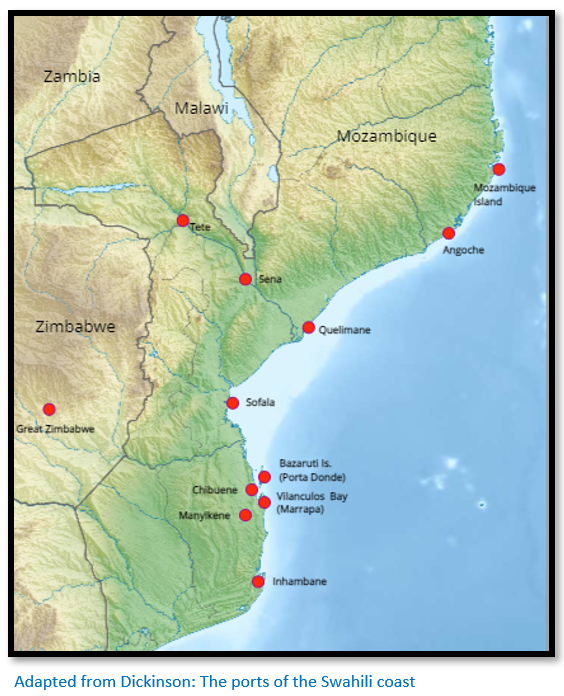

Long before the Portuguese arrived at Sofala, an important commercial network of Swahili settlements existed on the Mozambique coast from Bazaruto up the Swahili coast. From the coastal settlements a network of paths spread inland into the African interior usually following geographical features such as rivers and supported by groups of traders who relied on inter-personal relationships and kinship ties for support. African trade goods, including gold, were exported from these ports to the northern Swahili towns and through them to the Indian Ocean where they were exchanged for cotton, beads, spices and other Indian goods.[i]

This trade underpinned the prosperity of the northern coastal settlements and smaller ports such as Sofala, Quelimane, Angoche and Mozambique Island.

When the Portuguese under Vasco da Gama rounded the Cape of Good Hope and sailed up the east coast of Africa they knew almost nothing about the region and the Indian Ocean commercial network. Their knowledge of the Atlantic and the west coast of Africa which had been gained incrementally would be of no help on the east coast of Africa and the Indian Ocean. “Operating throughout the Indian Ocean and in articulation with the inland African trade routes by way of the coastal settlements, this network bustled to luxury and basic goods…”[ii]

For a general introduction to the region read the article Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century? under Mashonaland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

The Muslim influence predominates on the east coast

According to Arab oral tradition different Islamic groups first came to Africa with Muslim refugees fleeing conflict in the Arab peninsula. In 639, seven years after the death of the prophet Mohammed the Muslim Arab General, Amr ibn al-Asi invaded North Africa (the Maghreb) reducing the Christians to pockets in Egypt, Nubia and Ethiopia.

In contrast to North Africa, East Africa was never subject to one wide, sweeping Muslim takeover. Islam came to the East African coast in many waves and at different times. There is no single date in the records, but it is thought that Islam had taken root by the 8th century. The first Muslims came from different directions:

- Most obviously from the Arab peninsula, which at one point is separated by less than eighty kilometres of sea from the Horn of Africa.

- Egypt, where Islam first came to North Africa.

- Somalia, where the port of Zeila became very important in the 10th century in response to the political centre of the Muslim world moving from Mecca to Baghdad.

- Persia, there is a tradition that the first Muslims came from Shiraz in Persia (present-day Iran) They are known as the Shirazi’s.

"Then came Sultan Ali bin Selimani the Shirazi, that is, the Persian. He came with his ships and brought his goods and his children. One child was called Fatima, the daughter of Sultan Ali: we do not know the names of the other children. They came with Musa bin Amrani the Beduin; they disembarked at Kilwa, that is to say, they went to the headman of the country, the Elder Mrimba, and asked for a place in which to settle at Kisiwani. This they obtained. And they gave Mrimba presents of trade goods and beads. Sultan Ali married Mrimba's daughter. He lived on good terms with the people."[iii]

Undoubtedly there was early contact and dialogue between peoples on the East African coast and the peoples of the East - Arabia, Persia, India and even China, going back long before the Muslim religion became established. What is clear, is that once Muslim people arrived from the Persian Gulf and Oman they intermarried with the people of the coast very early on, forming a new kind of coastal society, the Swahili, with their own architecture, style of dressing and music. As Islam’s importance grew with the expanding commercial network it became a modernising influence in Africa, imposing a consistent order among different Bantu societies, strengthening powers of government and breaking down ethnic loyalties. Unlike Christianity, Islam tolerated traditional values, allowing a man to have more than one wife. For many, this made conversion to Islam easier and less upsetting than conversion to Christianity.

From the early centuries of its existence, Islam in Africa gained power by securing trade routes into gold-producing areas in Sub-Saharan Africa, including present-day Zimbabwe.

Muslim outsiders did not arrive on the Coast with the main aim of converting people; they came as traders, with influence. As in North Africa, trade was a powerful strand in the conversion of East African coastal settlements to Islam. East Africa offered gold, ivory and slaves and later on very fine woven cotton. In return, traders from the East and Persian Gulf brought textiles, spices, porcelain and other finished goods.

Most trade was seaborne

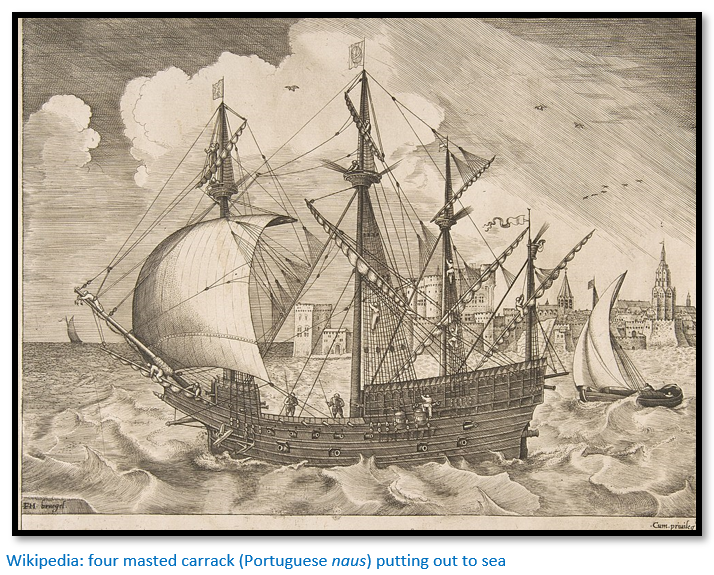

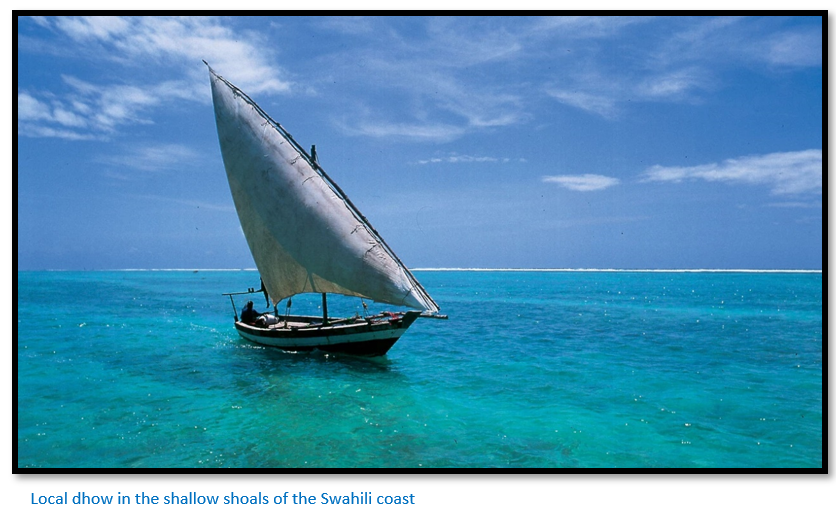

Navigation up and down the East Africa coast depended on the monsoon winds and trade goods moved by small dhows with most of the settlements having sandy beaches up which the dhows would land; there are few natural harbours suitable for the ocean-going Portuguese naus (carracks) that needed to be large enough to be stable in heavy seas and for a large cargo and the provisions needed for very long voyages.

The dominance of the Kilwa Sultanate beginning from the 10th Century

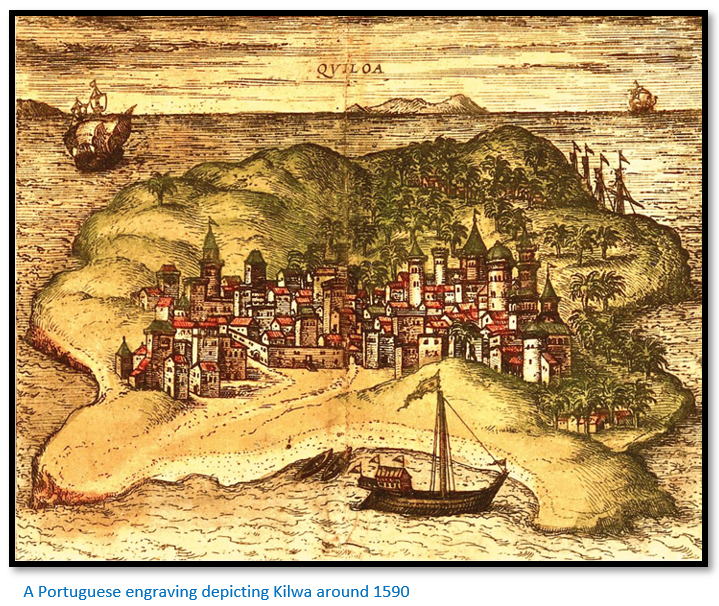

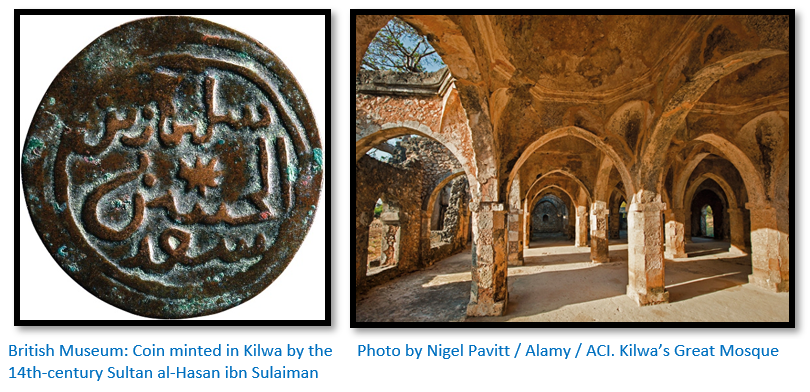

By the 14th century Kilwa was the most powerful kingdom along the coast - situated on an island some 680 kms north of Mozambique Island. During its heyday, Kilwa was the foremost port in a string of coastal trading cities that formed along what became known as the Swahili Coast. Swahili is derived from an Arabic word meaning “coastal dweller” and became the name for the regional language.[iv]

Kilwa Kisiwani Island was settled from the 4th Century and by the 8th Century when the first mosque on Kilwa was built, a Swahili culture began to take shape and united the African coast from Somalia in the north to Mozambique in the south. As Muslim traders began to flow in and out of the region, small-time Swahili traders started to see possibilities for more ambitious trade operations.

In total at least 20,000 Swahili Coast coins are known. The five groups are as follows: Shanga silver, Tanzanian-type silver, Kilwa copper, Zanzibar copper, and Kilwa gold. By far the largest number of coins, approximately 13,000, are of Kilwa copper type.[v]

Gold from Sofala was the basis for Kilwa’s prosperity

Suleiman Hassan, the ninth successor of Ali (and 12th ruler of Kilwa, c. 1178–1195) wrested control of the southerly city of Sofala from the Mogadishans. Sofala was the principal transhipment centre for the gold and ivory trade with Great Zimbabwe and later the Mutapa State in the interior. Possessing Sofala brought a windfall of gold revenues to the Kilwa Sultans that allowed them to finance their expansion and extend their powers all along the East African coast.[vi]

Flowing out of the interior of Southern Africa and present-day Zimbabwe, gold had been traditionally traded out of the port of Sofala since the 10th Century, located in today’s Mozambique. Kilwa started to extend its influence to control Sofala, but also the Bazaruto Archipelago as its southern outpost until the entire East African gold trade came under Kilwan control. This regional trade network between the Mutapa State in the interior and the East coast of Africa, India and Asia brought prosperity to the small southern ports, Sofala or Mozambique long before the Portuguese arrival.[vii]

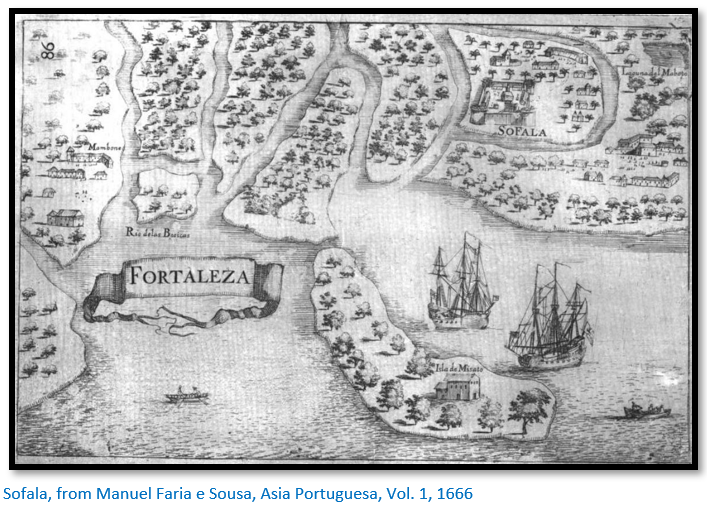

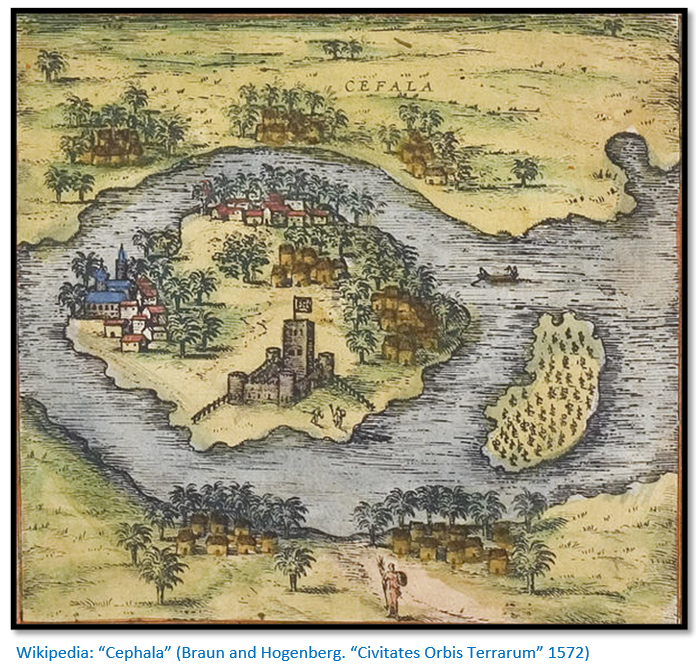

Sofala may have comprised a number of small ports

At the time the Portuguese arrived the gold traffic from the interior was controlled at Sofala by Muslim traders under the rule of Sheik Isuf who had just declared his independence from the Kilwa Sultanate. Alcacova states in 1506 that Sheik Isuf’s traders numbered about 800 and lived side by side with the local native community.

Ana Roque writes that Sofala, reported by Al ’Masudi in 943 as the main port for the export of the gold mined on the Zimbabwean plateau, was most probably not one port, but a complex of small ports around Sofala Bay and Muringari as the locals readjusted the port’s position to the constant changes of the coastline and of the Harbour’s sandbar.[viii]

Goods traded by Swahili merchants

African goods included gold, ivory, timber, pearls, seed pearls, ambergris, tortoise shells, animal skins and slaves that were exported to India and the other countries bordering the Indian Ocean where they were exchanged for Indian textiles, glass beads, ceramics and spices that were sent back to the southern ports and, through them, to the interior African kingdoms.[ix]

Cereals such as sorghum, pearl millet, finger millet, teff and African rice, cattle, salt, pottery, iron tools such as hoes, animal skins, herbal medicines and local cotton textiles were traded at local and regional markets.

Most of these ports were still operating in the early 16th Century, such as Angoche, Mozambique Island, Quelimane or Sofala, although others like Chibuene had fallen into disuse. At all these places the Portuguese arrivals noticed the Muslim traders speaking both Arabic and the local Karanga languages, confirming the regional importance of a mixed community of Arabs and Africans known as Swahili.

By integrating into the local community through marriage and keeping their ties to other Muslim communities up and down the coast these traders handled the bulk of the external seaborne trade as well as the internal commercial trade and became influential and prosperous. At Sofala Antonio Fernandes, between 1512 to 1516 (1516 ) saw how the Swahili traders were an integral part of the local, regional and intercontinental trade network and the same pattern was repeated at all the east coast settlement.

The Portuguese have little knowledge of local conditions when they arrive

Very little was known by the Portuguese when they first sailed to the Indian Ocean and dropped anchor off Mozambique Island. Although surprised by the settlement of pole and dhaka huts thatched with palm leaf, they were afterwards amazed by the local dhows and by the skilled navigation of the pilots and sailors and above all by the wealth of the local chiefs and how they were integrated in the interregional commercial network.

Vasco da Gama’s first reports to Lisbon emphasised the important commercial role of the east coast of Africa, local people had long tradition of trading with Muslim merchants who were integrated into their communities. Larger ships came from India with cloth, glass beads and spices which were off-loaded onto smaller dhows that sailed south down the coast from Mombasa, Malindi and Kilwa to the smaller ports where they were exchanged for gold, ivory, pearls and seed pearls.[xi]

From their little knowledge the Portuguese form an Africa strategy

Based on their knowledge of the above trade and vague information of trade at Sofala of gold mined in the African interior they made their plans. This was to impose their rule in the region using the superior firepower on their naus so that they controlled the Indian Ocean and through Sofala – the focal point of the gold trade – to gain access to the gold mines of the interior and to oust the Muslims from their position of power.

The Portuguese believed their plan to control the commercial network in the Indian Ocean required establishing a permanent military presence at Sofala and Mozambique Island with sufficient military resources to make the Kilwa Sultanate subordinate to their rule as well as establishing strategic alliances with local rulers such as Malindi. Port cities, such as Zanzibar, which did not welcome the Portuguese presence would be forced to submit and pay tribute.

The ultimate goal was a monopoly of the spice trade from Asia

Dominating the east coast of Africa was not the Portuguese Crown’s final objective but subduing the power of the Swahili traders ‘the Moors’ and forcing them to pay taxes and fees (cartazes) in order to trade was important to establish a trading monopoly. Dominating the spice trade between the Far East and Europe was the ultimate goal and breaking the monopoly of the silk road. Their interest in the Mutapa State’s gold mines was simply as a source of revenue to purchase spices – India would not accept the commodities that Europe had to offer – they wanted gold bullion.

Mutapa gold and a Portuguese port of call were required to achieve their plan

Portuguese naus often required repairs after rounding the Cape of Good Hope and they certainly needed victualling with fresh food and supplies and to give the ship’s crews time for rest and recovery. Sofala as a factory-fortress and Mozambique Island as a port of call appeared to both be essential components of their plan.

It is interesting that the Portuguese felt that their initial reception at Sofala was hostile enough to warrant the construction of a fortress with a garrison of soldiers and royal officials.[xii]

But Portuguese plans are frustrated

Ana Roque writes that the Portuguese plans were frustrated by a number of factors despite Pêro de Anaia (part of the 7th Armada) in 1505 being granted permission by sheikh Isuf to establish a factory-fortress (Fort São Caetano) at Sofala. Dickinson writes: “Pero d’Anaia raised a mangrove-pole fort on a sand spit commanding the entrance to the Sofala river.”[xiii] The wood was later replaced by stone brought from Portugal as ballast in the holds of the Portuguese naus. This seemed the only place where it seemed possible to control the entrance to the lagoon with a clear field of fire all around, although the site had no fresh water or firewood.

Other unexpected frustrations included:

- Muslim kinship relationships with local communities were difficult to replace with new trading relationships

- Many of the small ports on the Swahili coast were in decline in the early 16th Century including Sofala through diminished trade brought about by succession quarrels in the Mutapa State and their vassals (Quiteve, Manyika) asserting their independence and controlling the routes to Sofala which restricted the gold trade

- Sofala was subject to marine erosion and silting up of the harbour as was the Buzi river connection with the interior

- The decline of Great Zimbabwe and the rise of the Mutapa State on the northern Mashonaland plateau amongst the most prolific goldfields meant the old trade routes to Sofala became less preferred as the Zambesi river gave easier access to the Swahili trading settlements at Tete and Sena

- The gold and ivory trade of the rising Torwa State, south west of Great Zimbabwe and based at Khame and the coast at Chibuene, Marrapa and Ponta Dondo at Bazaruto Island grew steadily bypassing the Portuguese at Sofala.

They try military force to impose their rule

The immediate Muslim response was to resist the Portuguese response. The Portuguese believed that their right to control the Indian Ocean was indisputable and they were quite prepared to enforce their presence with violence.

In 1505 Francisco de Almeida brought his fleet into Kilwa harbour and landed some 500 Portuguese soldiers to drive Emir Ibrahim out of the city before installing a rival as a Portuguese vassal.

Other military measures taken by the Portuguese at the same time included the sacking of Mombasa in 1505 under the orders of de Almeida, the Tristan da Cunha campaigns on Madagascar’s northwest coast in 1506 and the sacking of Oge carried out by Tristan da Cunha, Afonso de Albuquerque and João da Nova.

In 1505 Fort São Caetano at Sofala was attacked by local natives under their leader Makonde with assegais, clubs, bows and arrows, including incendiary arrows. Part of the wooden palisade was destroyed before they were beaten back by the garrison using their arquebuses and breech loading swivel guns.

The attack showed the inadequacy of the existing wooden palisaded stronghold. With the death of Pero de Anaia in 1506, the overseer Manuel Fernandes was elected captain, and in the following year began the construction of Fort São Caetano with stone masonry from Portugal and lime from Quiloa, an island near Dar-es-Salam.

The supply of gold is more fluid than first understood

When the supply of gold begins to dwindle the Portuguese understand better the former connection Sofala had as a trading-station with the Kilwa Sultanate and which has now been cut and the importance of the Muslim kinship relationships with local communities on the Swahili coast and the interior which continues to thrive. They had believed that once they captured Sofala they would have a monopoly of the gold trade.

But the internal succession struggles within the Mutapa State had reduced the supply of gold at Sofala to almost nothing.

In addition, the range of trade commodities the Portuguese had to offer was not proving popular with the gold sellers who preferred the Indian cloths and glass beads offered by the “Moors.” They needed to co-operate better with the local Swahili communities and get a better understanding of the trade.

Also, it soon becomes apparent that the bulk of the gold trade was now reaching the coast at Swahili ports north of Sofala of Quelimane and Angoche via the Zambesi valley. The Mutapa State was still powerful enough to control the mines and the supply of gold and the Swahili trading settlements of Tete and Sena and coastal ports of Quelimane and Angoche were becoming the new Sofala’s.

An experiment of trade alliances with local Swahili merchants

Roque writes: “As early as November 1506, the first results of this readjustment were reported by Manuel Fernandes, the local Feitor. Hoping to reduce business that the trading post was unable to control and benefit from the local influence of the Muslim community, Fernandes, strongly committed himself to forming a group of ‘friendly Moors and subjects of the King.’ They would act as intermediaries between the trading post and the hinterland kingdoms in favour of Portuguese interests. The initiative had little success but his successors were still keen on preserving and even strengthening this link. They asked the “Moors” to serve officially as mediators in negotiations and included them in Portuguese embassies sent to local kingdoms and chieftaincies.”[xiv]

The value of Sofala declines in Portuguese eyes

With a better and first-hand understanding of the situation, in October 1505, Captain d’Anaia wrote to the Viceroy Francisco de Almeida asking him to inform king Manuel I that Sofala was unhealthy for men who were dying from malaria and entailed high maintenance costs and they would be better off building a fortress on Mozambique Island. In addition, he advocated bi-annual visits to Sofala to purchase gold rather than a permanent presence and thus adopting the same system as the Swahili traders.[xv]

Within a year, the Viceroy de Almeida had suggested the factory move from Sofala to Kilwa and a base should be created on Mozambique Island. The amount of gold being traded at Sofala was very small and did not justify the expense of the garrison and the sandbar across the harbour mouth had built up so that the Portuguese naus could no longer enter safely.[xvi]

They realise to survive they must build good relationships with local communities

By the 1550’s the Portuguese had built up a good knowledge of the area between the Buzi and Save rivers and begun trading with local communities for food supplies and built up good relationships with local chiefs and forged local commercial partnerships and were integrated into the local trade networks.

Despite complaining to the king about the poor conditions at Sofala, the increasingly ruinous state of Fort São Caetano, poor facilities to store goods and the difficulties of trade and obtaining gold, many of those at Sofala began to trade on their own account. For this they can be hardly blamed…salaries, supplies and fresh soldiers never arrived on time thanks to the hazardous sea voyage and the garrison was often left to survive on their own from the hardships and disease.

To get supplies of provisions for the garrison it was necessary to get access to local distribution networks, mostly dominated by “Moors” who acted in collusion with Sofala chiefs. This allowed them to gradually develop personal relationships with the most important chiefs in the Sofala region and resulted in joint ventures especially at an individual level and the subsequent acceptance of many Portuguese into the local communities with the result that as early as the first quarter of the 16th Century there were Portuguese living in the inland region.[xvii] Roque states some even lived in the courts of local chiefs such as the Kingdom of Quiteve, a sometime vassal of the Mutapa State.

However the drying up of the gold supply through Sofala meant that it was destined to become a place of exile for criminals and convicts and Mocambique Island became the centre of Portuguese commercial activities.

Criminals and convicts exiled to Sofala often left to live within the African communities

Fr. Monclaro writes that they often ran away from Sofala and went to live among the local indigenous population and married local women and were sometimes supplemented by survivors of shipwrecks who chose to live in the backcountry and often, though acting on their own, became the main mediators of Portuguese trade in the region.

Roque quotes contemporary writers…in 1520 Sachiteve Ynhamunda had the support of Portuguese outlaws (Silveira, 1518) that one of his daughters was married to a Portuguese (Anonym, 1530) and that António Fernandes after his journeys through the Mutapa State between 1511 and 1515 was representative of the King of Portugal in the Quiteve court between April 1517 and March 1518 along with Francisco da Cunha and João Escudeiro, a ward of Manuel Goes, in Sofala since 1505 (Almada, 1516)[xviii]

Roque states their influence cannot be over-emphasised: “Irrespective of the offence leading to their exile, these men were good explorers, adventurers, interpreters and diplomats. Acting on their own or as representatives of the Portuguese authorities, they were mainly responsible for the first reconnaissance of the African hinterland…”

Once settled into local communities with their own families, some of these Afro-Portuguese went on to take over leadership and control of the main sectors of economic life of the region. Roque quotes: “António Rodrigues, an exiled native of Sofala [in the 16th Century] settled in the south with homes in both the Bazaruto islands and on the mainland near the “rivers of Monemone.” From these two places he controlled the production, distribution and marketing of goods and foodstuffs and the shipbuilding and boat charter business. He was also the only locally recognised authority for issuing travel permits for people and goods in the area. Although he had been expelled from Sofala as an outlaw, the trading post’s authorities regularly found themselves in need of his services and apparently no one could travel safely in the region without his permission or assistance (Naufrigio da Nau São Thomé…, 1589)

Roque writes that António Rodrigues was just one of the many Afro-Portuguese who would continue to play a key role in the regional economy and maintain good relations with the local chiefs.

A “shadow empire” is created in Mozambique

Roque suggests these Portuguese living within local communities: “operating outside areas under formal Portuguese administrative control, took on the dual roles of actor/individual and actor/vehicle for Portugal’s political and economic interests…”

In effect they created a “shadow empire” that acted in parallel with the official representatives of the Portuguese crown operating from the settlements at Sofala and Mozambique Island and later Sena and Tete. They brought trade from these settlements to local chiefs in the interior, although much of the focus was on smuggling goods. Through their efforts local people learnt some Portuguese and the traders learnt rudimentary Karanga, but the overall effect was to make the Portuguese language a sort of lingua franca for trading purposes throughout Mozambique in the 16th century.

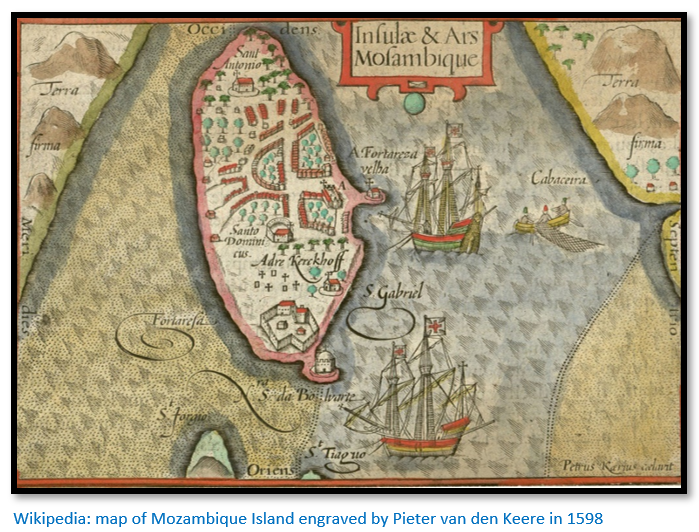

Portuguese activities gradually shift to Mozambique Island

Between 1507-8 the Torre de S. Gabriel (later referred to as Torre Velha) was built to house the storerooms of a trading station and factor’s residence on Mozambique Island and in a short time Mozambique Island became officially, the most important Portuguese trading station and port of call of the Carreira da Índia (annual voyage between Lisboa and Goa) in the Indian Ocean.

Apart from the factory and warehouses, the Chapel of Nossa Senhora de Baluarte, located on the eastern tip of the island, is considered to be the oldest European building in the southern hemisphere.[xix] The fortress of São Sebastião and a hospital were built in the 16th Century, a customs house controlled the commercial traffic and the island became the starting point for the departure and arrival of every Portuguese ship sailing along the African coast and between Africa and India. Boats would be repaired, sails and masts replaced, food and water replenished and sick sailors cared for in the hospital.

The Captain of the fortress of Sao Sebastiao had a monopoly of the trade in Indian goods, but it was common practice for both residents of the island and Portuguese sailors to carry out a clandestine trade in ivory and gold and to smuggle goods along the coast and to the islands. Ships were often forced to stay for months to careen their hulls on the beach or wait for the monsoon winds and in that time some profitable private trading might be carried out.[xx]

Mozambique Island never became a shipbuilding and repair site to rival the port, shipyard and arsenal at Goa which had an unrivalled supply of timber and skilled Indian manpower. Most of the repairs had to be carried out by the sailors themselves with their own tools while anchored in the safety of the harbour.[xxi]

The Island also suffered from tropical and subtropical cyclones between November and April - the manamocaias – that left behind them a trail of destruction and could drive ships ashore to be wrecked. They made navigating large ships in the region a hazardous task; Vasco da Gama had noted in 1498 that the local dhows were small without covered decks, the planking sewn tight with strong ropes without nails and with matting palm sails. Smaller and more manoeuvrable than the Portuguese naus, dhows were much more appropriate for entering the river mouths and small sheltered bays of the coast. The largest traditional Swahili sailing vessel is the jahazi, which measures up to 20 metres long and whose large billowing sails are a characteristic sight off the east coast. With a capacity of about a hundred passengers, the jahazi is mainly used for transporting cargo and passengers in open water.[xxii]

Fr. de Monclaro in 1573 noted that dhows were much safer in shoals and sandy bars; they often had forks in the bow to uphold the vessel at low tide like a cripple leaning on crutches and they sailed so near the wind that they seem to go against it. The Portuguese quickly opted to using these traditional boats along the coast with their experienced sailors and pilots.[xxiii]

The Sofala gold trade never meets Portuguese expectations

Very quickly the garrison stationed at Sofala realised the gold from the interior would not be arriving in the expected quantities due to the succession quarrels and civil wars blocking the trade routes from Manyika to the coast and also the shift of the trading routes to the Zambesi Valley and the Angoche coast.

From the second quarter of the 16th Century it was very clear to the Portuguese that the trade routes had shifted to the Zambesi Valley and that Sofala was becoming a backwater in the trade network. Individual Portuguese traders and sertanejos (backwoodsmen) made their way on foot living alongside Swahili traders and even took up service as interpreters and political advisors in the interior. One sertanejo, António Fernandes, travelled as an official Portuguese ambassador throughout much of the Mutapa between 1512 and 1516. [See the article Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 – 12 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

The fortress captain and factor both left Sofala and moved their headquarters to Mozambique in the 1550’s. At the same time the Portuguese Crown ceased in their attempts to administer the trade monopolies directly and instead leased the monopoly rights to the captains.[xxiv]

Sofala was left to its own devices with a small, neglected and fever-stricken garrison, Fort Sao Caetano became increasingly ruinous and neglected. Salaries arrived late, if at all, and many in the garrison began trading for themselves and in co-operation with local chiefs.

The Portuguese establish a permanent presence at Sena and Tete

The Portuguese now shifted their strategy of capturing the Mutapa State gold trade from its focus on Sofala to establishing a permanent presence at the Swahili fairs at Sena and Tete in the Zambesi Valley by the 1550’s. This gives them much closer access to the gold mines of the Mutapa State. In addition the progressive fortification and build-up of Mozambique Island between 1522 - 1583 clearly shows their intention to have an easier and faster access to the gold trading network.[xxv]

This shift was reinforced by the Portuguese at Mozambique Island becoming directly immersed in the local trade along with Swahili traders in using the local dhows for coastwise shipping between Mozambique Island, the Quirimbas Archipelago and the Swahili Islands of Pate, Mafia and Zanzibar in the north and Madagascar in the south. In fact, from the second half of the 16th Century the local administration headed up by a captain traded on their own account and not for the Portuguese Crown.

Conclusion

It cannot be said that the Portuguese achieved their strategic objective of controlling the gold trade with the establishment of a permanent base at Sofala. Little trade was carried out and the gold mines of the Mutapa State were largely out of reach, although some gold from Manyika was traded.

In order to access the gold mined from the Mutapa State they were forced by the 1550’s to move to the Zambesi Valley. Initially they cooperated with the Swahili traders who had proved much more adept in adapting to the changing trade network. The Mutapa State and its vassals were constantly engaged in succession struggles that resulted in frequent interruptions to their commercial activities.

The Portuguese had to adapt Muslim ways of conducting business by sometimes marrying local women and building friendship and kinship relationships that enabled them to become part of the local commercial networks.[xxvi]

The next article will deal with the Portuguese feiras that were established close to the goldfields of the Mutapa State on the northern plateau of Mashonaland in present-day Zimbabwe.

Appendix 1

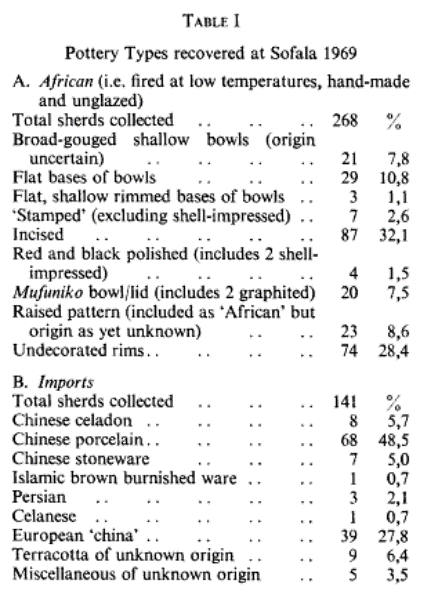

In 1970 R.W. Dickinson (see reference details) conducted a short excavation at Sofala and dug trenches and carried out some ground searches for exposed pottery on the nearby beaches and creeks and their finds are summarised below.

In addition 92 beads were recovered, all from drawn and snapped cane glass. The predominant colour was Indian red (61%) dark blue (18%) with smaller quantities of turquoise, light blue, light green, yellow, black and white.

References

R.W. Dickinson. The Archaeology of the Sofala coast. The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol. 30, No. 119/120 (Dec. 1975), pp. 84-104

Maria J.N. Maura. 7 September 2020. National Geographic: https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2020/09/this-abandoned-east-african-city-once-controlled-the-medieval-gold-trade

Newitt, M. (2008). Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of Colonial Port City. In L. M. Brockey (Ed.), Portuguese Colonial Cities in the Early Modern Word (pp. 105-128). Farnham, Burlington: Ashgate

Newitt, M. A short History of Mozambique. Hurst and Company, London 2017

John Perkins. The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments. https://journals.openedition.org/afriques/1769?lang=en

Ana C. Roque. Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean Under Portuguese Rule. History Research, ISSN 2159-550X March 2013, Vol. 3, No. 3, 188-204

Ana C. Roque. The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade

Notes

[i] The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade

[ii] Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean Under Portuguese Rule

[iii] G. S. P. Freeman-Grenville: The East African Coast. Select Documents from the first to the earlier nineteenth century. Clarendon Press, Oxford University Press 1962

[iv] this-abandoned-east-african-city-once-controlled-the-medieval-gold-trade

[v] The Indian Ocean and Swahili Coast coins, international networks and local developments

[vi] Wikipedia: Kilwa Sultanate

[vii] Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean under Portuguese Rule

[viii] Ibid

[ix] Ibid

[x] Ibid

[xi] Ibid

[xii] The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade

[xiii] The Archaeology of the Sofala coast

[xiv] The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade

[xv] No letter has been found, but the Sofala clerk Gaspar Correira states it was sent

[xvi] In 1519 the factor at Sofala wrote to the King that boats were being forced to unload their cargoes in Quiloane Island

[xvii] The Sofala Coast (Mozambique) in the 16th Century: between the African trade routes and Indian Ocean trade

[xviii] Ibid

[xx] Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean under Portuguese Rule

[xxi] Mozambique Island: The Rise and Decline of Colonial Port City

[xxii] P. Briggs. Dhows of the Swahili Coast. http://www.zanzibar-travel-guide.com/bradt_guide.asp?bradt=1904

[xxiii] Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean under Portuguese Rule

[xxiv] A short History of Mozambique, P29

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] Mozambique Ports in the 16th Century: Trade Routes, Changes, and Knowledge in the Indian Ocean under Portuguese Rule

When to visit:

n/a

Fee:

n/a

Category:

Province: