The decline of the Mutapa state c.1623 – c.1902

The cultural, political and military decline of the Mutapa state had probably begun from the 1590’s exacerbated by increasingly frequent civil wars and the Maravi invasions. The Maravi succeeded in reaching the goldfields of the upper Ruya river and by 1601 were close to the Mutapa’s capital. Although they were eventually pushed back, the decision by Gatsi Rusere to execute his own general (Nengomasha) was a fatal mistake that led to civil war within the state and his eventual capitulation to the Portuguese. See the period under Gatsi Rusere’s rule under the article the Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623 under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

As the grip of the centralised state weakened so the power of the vassals and the Portuguese increased proportionately. At the same time the Rozvi state broke away and began building its own power base, the Portuguese were in the ascendancy and able to interfere in the succession of the Mutapa, supporting their own nominees in favour of the real claimants.

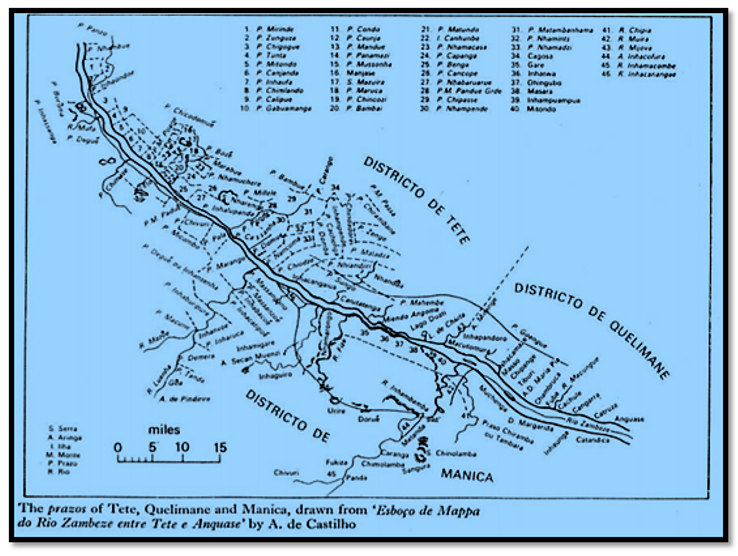

As the power of the Mutapa’s waned, they had increasingly to rely on Portuguese military and commercial support who exploited the rivalries between competing vassals. Gatsi Rusere was unable to collect the traditional kuruva - the cloth traditionally paid to the Mutapa by each new Portuguese Captain at Mozambique. At the same time land was being lost to the gradual advance of the prazo-holders around Tete.

By 1630 under Mavura Mhande the Mutapa state itself was effectively a Portuguese vassal.

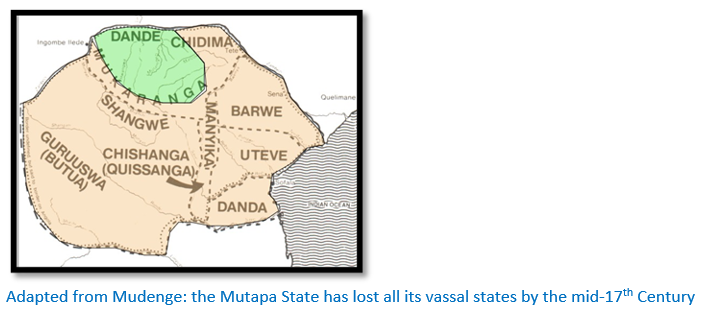

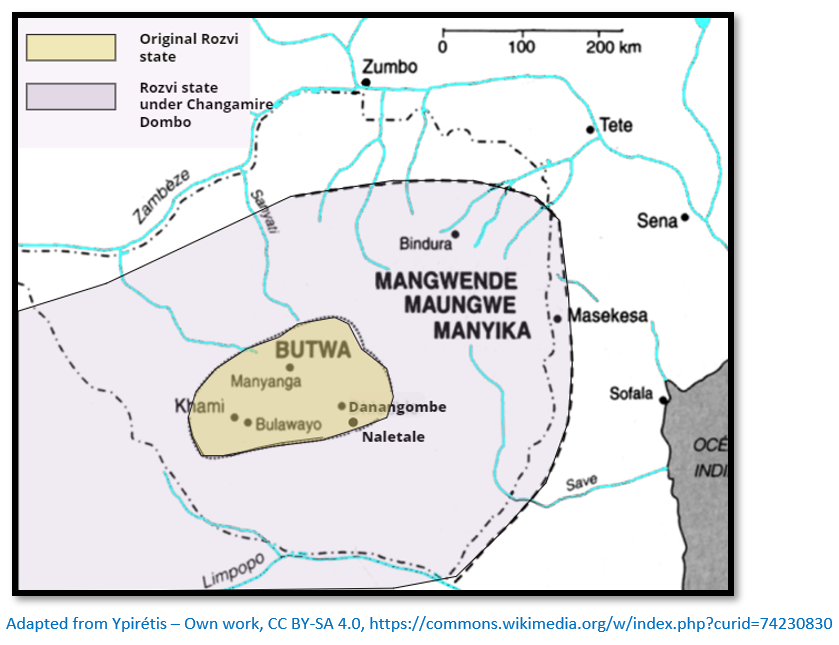

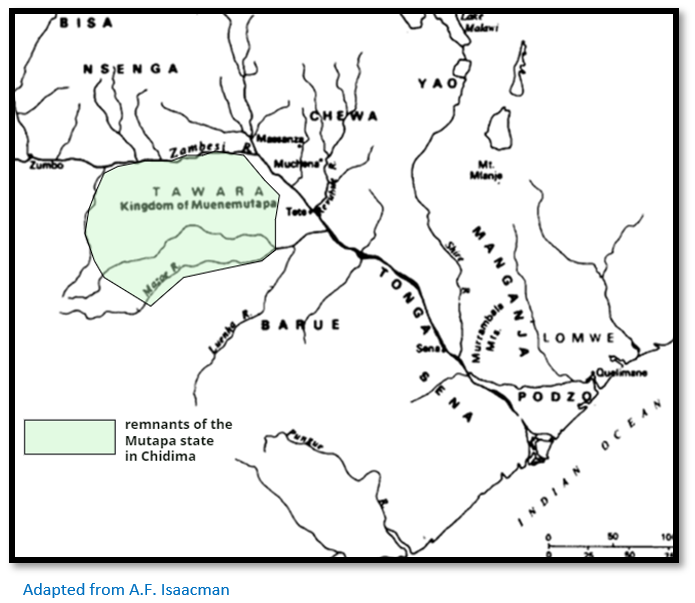

Stanley Mudenge the author of A Political History of the Munhumutapa c1400-1902 quotes the Oliver and Fage[i] summary: “the Changamire’s…in a campaign lasting from 1693-5 finally drove the Monomotapa and their Portuguese overlords off the plateau…and left the 18th Century Monomotapa to rule a tiny remnant of their former territories in the valley between Tete and Zumbo as puny puppets of the Portuguese.”

Mudenge does not accept this view wholeheartedly saying:

- The Mutapa state was not totally ejected from the Mashonaland plateau

- They were not always the puny puppets of the Portuguese, at times remaining “robustly independent” despite the endless succession struggles and civil wars and managing at times to hold off the prazo-holders and even forcing the Portuguese traders and settlers to plead for help from the Rozvi.

The Mutapa political / economic system is weakened by the Portuguese presence

Innocent Pikirayi believes the entire Mutapa political system was undermined by Portuguese interference and intriguing following their first permanent community within the Mutapa state from c.1540. Their long-term intentions were never in doubt as they sought to weaken the Mutapa state in order to gain possession of the gold mines. See the article Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa) under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

In addition, the Mutapa monopoly on potential sources of wealth loosened as the trade network became more widespread with other chiefs and headmen participating in trade for their own benefit rather than the ruling elite’s benefit. The accumulation of individual wealth from gold trading: “in the region transformed Mutapa society and political power.”

Portuguese mercantile capital was to exert excessive demands on the local population, which had to mine more gold, we are told, thereby investing more time in the activity at the expense of agriculture. This shift in productive and accumulation patterns also undermined the Mutapa political system as it meant reduced tributary inflows to the royal palaces.

The Zimbabwe culture continues but not the dry-stone buildings associated with Great Zimbabwe

After c.1550 the tradition of dry-stone building as at Great Zimbabwe came to an end and pole and dhaka settlements, sometimes of considerable size, became surrounded in wooden stockades. Innocent Pikirayi[ii] quotes Joao dos Santos, who worked as a missionary at Tete from 1585 to 1595 and who mostly quotes from earlier Swahili traders, as saying that royal palaces were no longer built with stone. He noted instead that “....even the king's palaces are built of wood covered with clay and thatched with grass” (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 7, P275) and adds: "The dwelling in which the Monomotapa resides is very large and is composed of many houses surrounded by a great wooden fence, within which there are three dwellings, one for his own person, one for the queen, and another for his servants who wait upon him within doors. There are three doors opening upon a great courtyard, one for the service of the queen, beyond which no man may pass, but only women, another for his kitchen, only entered by his cooks." (Theal 1898-1903 vol. 3, P356-7)

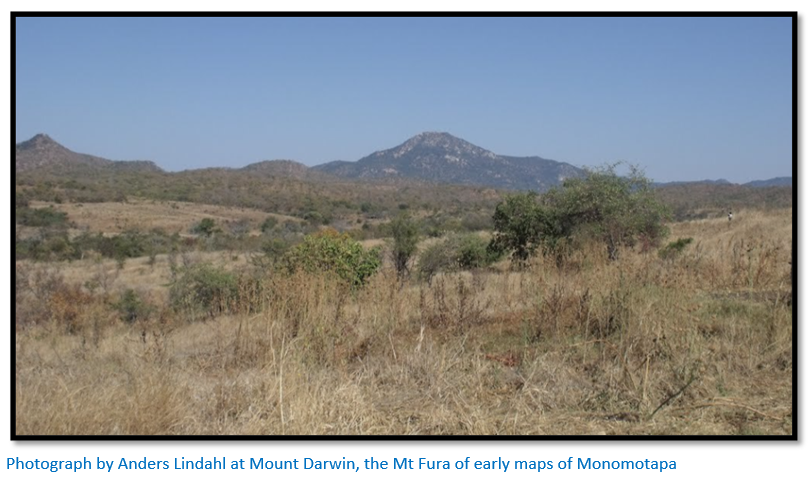

Innocent Pikirayi reminds us that there are over 300 dry-stone building complexes in Zimbabwe, but the tradition of building them as palaces; the dzimbahwe of the ruling elite came to an end quite early in the Mutapa state. The University of Zimbabwe carried out an archaeological survey and test excavations at Baranda Farm, which was close to the Portuguese feira at Massapa near Mt Fura, present-day Mt Darwin.

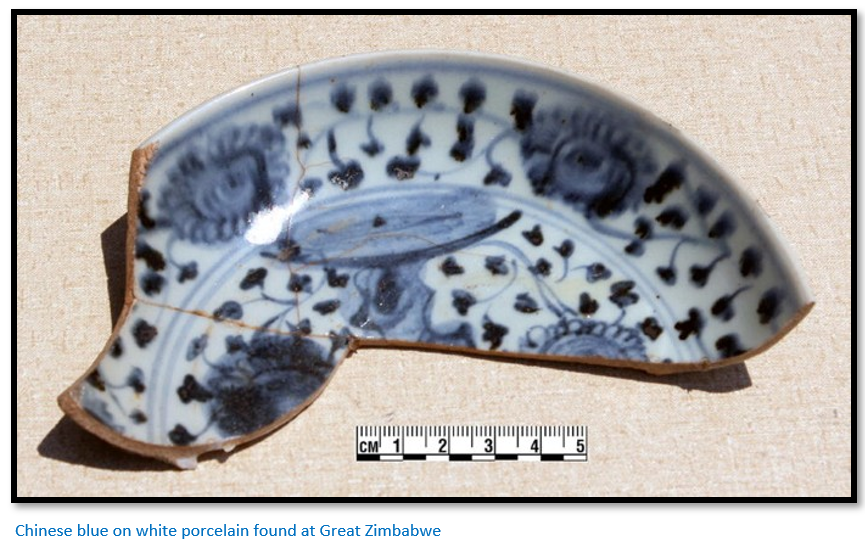

The material remains found scattered over more than 180 hectares at Baranda Farm included Zimbabwe culture graphite burnished pottery and imported stoneware, earthernware and porcelain, metalware, gold processing remains and glass beads. Pikirayi concludes that a densely populated community settlement existed at the site displaying levels of socio-political complexity identified with the Zimbabwe culture.[iii]

At Great Zimbabwe the gold trade was conducted from within the confines of the royal court, but within the later Mutapa state in the 16th Century the Portuguese conducted trade from their feiras which became the new focus of commercial activities and later on even centres of political power. Pikirayi maintains their interference in court politics and the succession disputes of the ruling elite undermined the Mutapa political system.

Succession disputes often escalated into violent struggles

Succession has already been discussed in the article on The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623. By appointing their own family members as regional governors of vassal states, whenever a Mutapa died the whole state administration became unstable. Their successor had to then balance the difficulties of appeasing their own loyal court followers and those powerful males appointed by the previous Mutapa as governors who might be their brother or uncle. A frequent result was civil wars between the king and those governors who were not keen to relinquish their power.

But in addition to interference into each other’s succession politics, conflict between the Mutapa state and its vassals could occur over tribute payments, border disputes, competition over the control of long-distance trade routes and vassal states asserting their influence whenever they detected weakness from the centre. Usually such conflict reflected clashes of the ruling elite interests and did not trickle down to the common people who continued to interact across borders with each other.

The Mutapa’s lost control of the trade network and were forced to negotiate new trading arrangements with the Portuguese merchants from Sena and Tete and even those broke down in the violence of the 17th Century.

Portuguese written accounts also mention the existence of the Massapa trading centre as part of a regional network of centres called feiras and frequented by Portuguese and other traders from the early 16th Century and by a resident local population part of the Mutapa state before it moved northwards across the Ruya River.

The extent of the Mutapa state

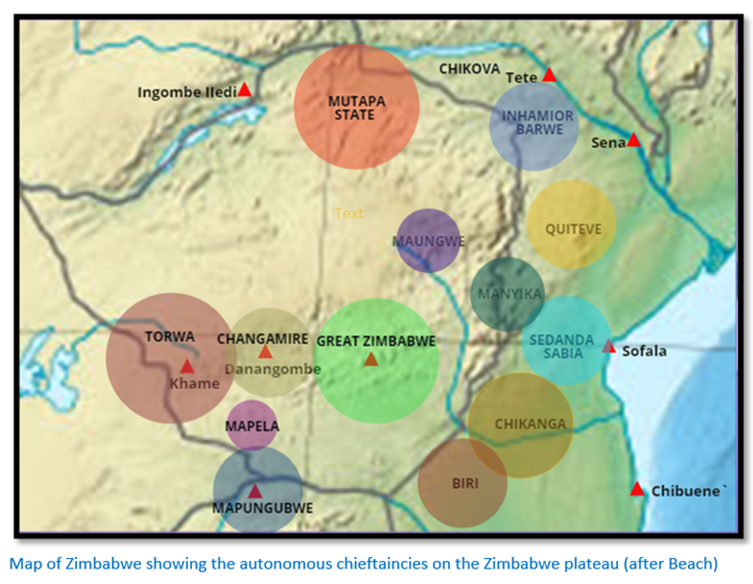

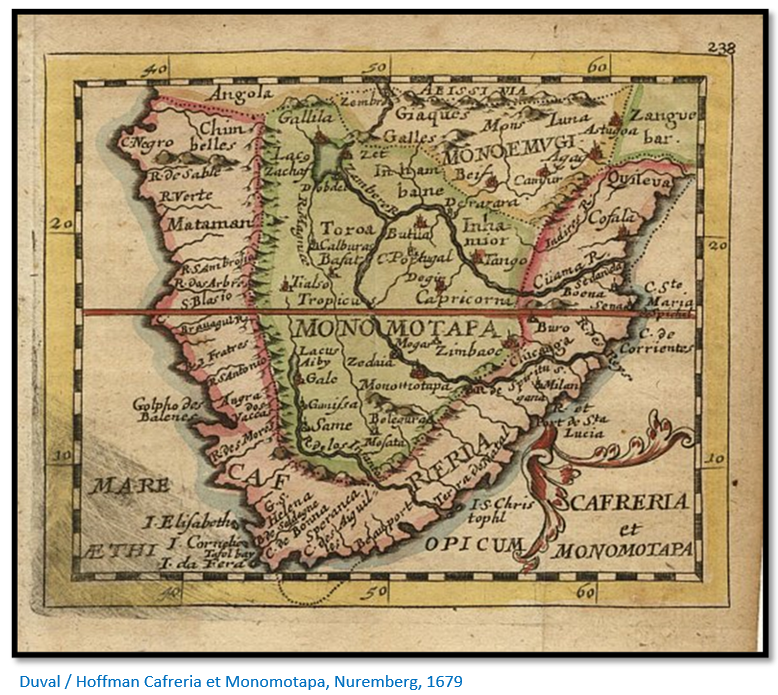

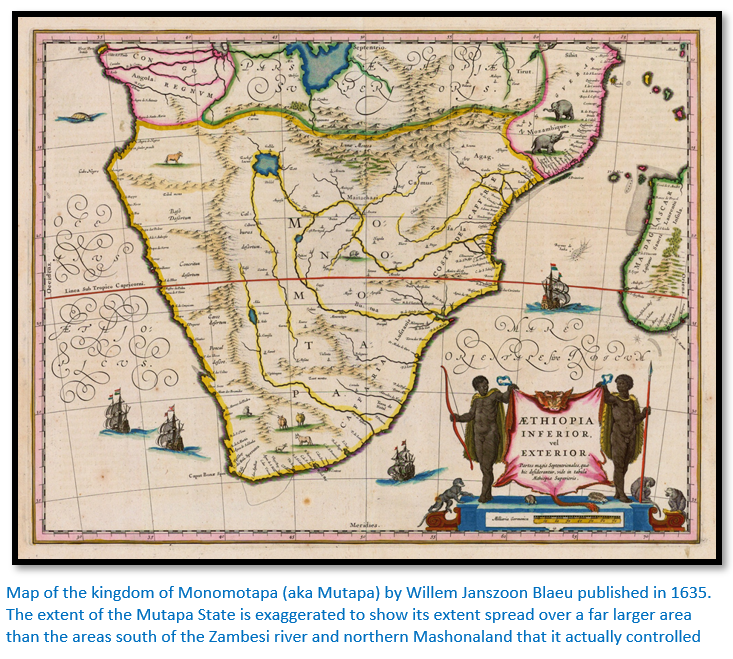

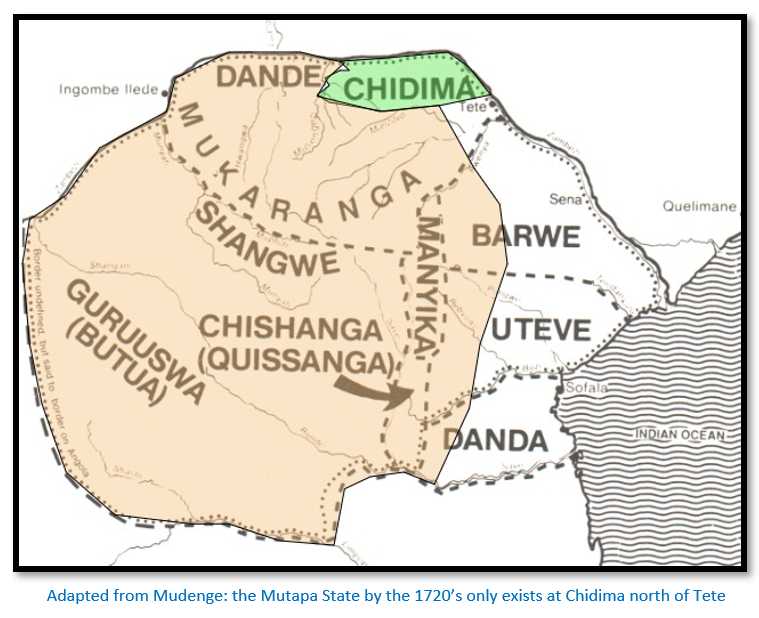

As explained in the article The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623 the Mutapa rulers and the Portuguese tended to exaggerate both their power and the boundaries of their state. It is unlikely that the Mutapa state ever ruled over the Torwa state (Butua or Guruuswa) in the southwest of the plateau. Outside the area of Mukaranga, Dande and Chidima oral traditions and contemporary Portuguese documents mention that Chikova, Barwe (Inhamior) Manyika (Chikanga) Quiteve, Sedanda and Biri were at various times vassals to the Mutapa state.

Contemporary Portuguese maps portrayed these vassals as part of a vast empire; in reality it is much smaller than this and was made up of the northern plateau of Mashonaland and a wide area of the Zambesi Valley to the west (Dande) and to the east Chidima / Chikova but contemporary descriptions state the empire stretched: “between the Lake Ro and the Ethiopick Sea, together with the mountains of the moon, Cluverius reckons to be four hundred Dutch miles: and the Breadth, between the Head-Fountain of Nilus and the Cape of Good Hope, three hundred Dutch miles. For all the little Kingdoms, from the river Magnice [Zambesi] to the Cape of Good Hope are said to acknowledge the Prince of Monomotapa for their supreme Lord. But the whole compass of this country is accounted by many but seven hundred and thirty-five French miles.”[iv]

Even Wikipedia states the Mutapa state in the 16th Century encompassed 700,000 sq. kms – an area that includes all of present-day Zimbabwe extending through Mozambique to the Indian Ocean and the eastern region of Botswana; but in reality it lacked the administrative capacity and means to govern such a large area. Present day boundaries are a product of 19th Century colonialism. In the Mutapa state territorial boundaries were usually defined by natural features clearly such as rivers or mountains. Bourdillon noted, the boundaries of pre-colonial African states were: “usually defined by natural features such as hills and rivers well known to its inhabitants, but precise agreement over these boundaries are not always shared with inhabitants of neighbouring chiefdoms. The country within the boundaries of a long established chiefdom usually has a traditional name apart from the dynastic title of the chief who rules over it, and the people distinguish themselves from their neighbours by using the name of their chiefdom…”[v]

Virtanen wrote much the same: “In traditional Shona cosmology land is intimately associated with the history of the chiefdom, with the ruling chief and with ancestral spirits who lived on the land.”[vi]

Commonality of language

The Mutapa state enjoyed the advantage of a common language, Karanga that was used by all the people between the Zambezi and the Limpopo Rivers although differing dialect clusters developed for the Korekore in the north, Karanga in the south, Zezuru in the centre, Kalanga in the south-west, Manyika in the east and extended as far as Mozambique to include the Barwe and Ndau as far down the coast as Inhambane. To the west Karanga was spoken as far as the Shoshong Hills and to the south by the Venda people. This language came to be known in colonial times as Shona.[vii]

This state of affairs continued for many centuries until the Nguni invasions of the 19th Century.

Political and Administrative Control in the Zimbabwe Culture

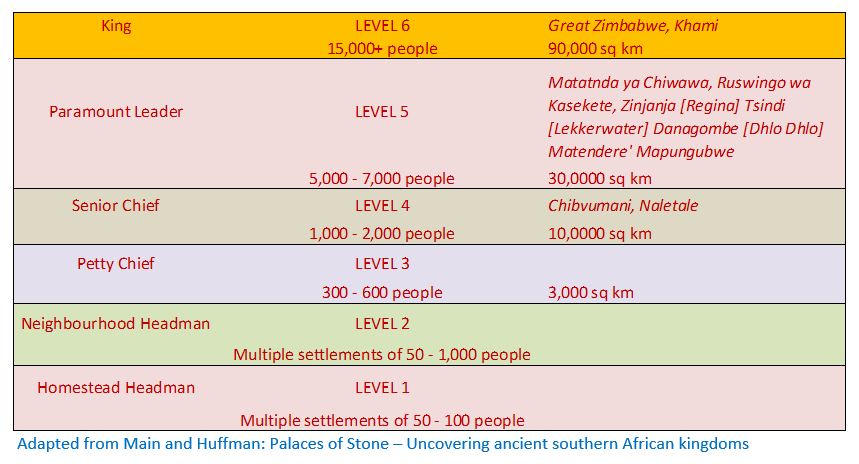

Main and Huffman argue that political levels were based on a hierarchy of courts and that every settlement from the smallest to the largest capital had a men’s court where affairs were discussed and disputes settled.[viii]

They say with the connected relationship between wealth and political power, the hierarchal levels in the table below were tied up with settlement and territorial size. Level 1 homestead included between 50 – 100 people, a neighbourhood headman (Level 2) had jurisdiction over 50 – 1,000 people, a petty chief (level 3) with a settlement of 300 – 600 people, a senior chief (level 4) with between 1,000 – 2,000 people, while a paramount leader (level 5) had between 5,000 to 7,000 people.

A number of early travellers noted that in pre-colonial times African polities were sub-divided into administrative units or wards, whose boundaries were clearly defined, each under a ward head. Fr Manuel Barretto noted in the 1560’s that the Mutapa state had wards (matunhu) with: “their own names and limits, which are called moganos, and these territories... had their own fumos or petty Kaffir kings.” Wards were divided into clearly marked villages each under a village head. In the Mutasa chiefdom of Manyika, a new village was opened up by the ward head after consulting the chief. During the ceremony to establish a new village, the ward head symbolically marked the limits of the new village by erecting a wooden peg in the ground (kudzika bango)[ix]

Nyambu Kapararidze (1623 – 1629)

Sometime in 1623 / 1624 Gatsi Rusere died and was succeeded by his son Nyambu Kapararidze who inherited a much diminished Mutapa state, now comprising just Mukaranga, as Barwe and Manyika had asserted their independence. However, there were others who believed they had a more rightful entitlement to succeed as the Mutapa state ruler in the Shona system of succession including:

- Gatsi Rusere’s sons including Nyambu Kapararidze, Dom Filippe and Dom Diogo,

- his uncle Mavhura Mhande, the senior son of Mutapa Chisamharu Negomo Mupunzagutu

There were other outsiders in contention who believed they were entitled, such as Karonga Muzura of the Maravi. In 1624 Muzura was attacking Sena and Tete to overthrow the Portuguese and then rule the Mutapa state. The Portuguese too, were well aware of these rivalries and ready to exploit any weakness in the remaining Mutapa state. Dom Diogo was particularly favoured by them as he spoke and could write Portuguese.

Little is known of the period 1624 – 27 from Gatsi Rusere’s death to Nyambu Kapararidze proclaiming himself as ruler. Clearly a state of semi-civil war existed.

Nyambu Kapararidze (1627 – 1628)

It is not entirely clear why Mutapa Kapararidze triggered a war against the Portuguese. Perhaps because the new Portuguese captain at Mozambique Island in 1627, Nuno Alvares Pereira, who led the 1619 expedition to the alleged silver mines of Chikova, delayed payment of the kuruva. In response Kapararidze had Jeronimo de Barros, the ambassador who in 1628 brought the kuruva killed and ordered a mupeto, the seizure of all their possessions, against all the Portuguese in the Mutapa state.

Others say that Kapararidze replaced all his father’s former advisers with new ministers who influenced him in this way. However, there may be another reason. The normal practice with the kuruva was for the captain of Mozambique Island to send a message to the Mutapa saying he should send his ambassador to Tete to receive the presents. Their own envoy would then accompany the kuruva back to the Mutapa’s dzimbahwe. A serious breach of protocol may have occurred by Jeronimo de Barros not seeking the Mutapa’s authority first and also robbed the Mutapa of the boca (mouth) presents which would have been brought with the invitation for the Mutapa to collect the kuruva from Tete.

Another reason maybe that Kapararidze’s uncle, Mavhura Mhande developed a special relationship with the Portuguese Dominican friars and Fr Luiz de Espirito Santo befriended Mavhura giving him the name of Dom Filippe and converted him to Christianity. Kapararidze believed this posed a threat to the Mutapa throne and: “was enraged and was searching for some means of vengeance.” Mavhura Mhande had been one of the claimants to the Mutapa throne in 1624.

Fortunately, André Fereira, ‘the captain of the gates’ heard of the killing of Jeronimo de Barros before he was ordered to attend the Mutapa’s court and managed to escape in the night to the safety of the Portuguese garrison at the chuamba at Massapa. From there he sent word to all the Portuguese traders in Mukaranga to retire on the feiras at Ruhanje (Luanze) Dambarare and Chipiriviri and to arm themselves. They defended those places until reinforcements arrived from Tete, although Fr Lucas de Santa Catherina suggests the Dominican friars’ prayers provided “protection of Heaven” and saved them from being massacred.

Portuguese retribution is swift

When news of the mupeto and the killing of Jeronimo de Barros reached Tete and Sena Manoel Gomes Soros was appointed captain-major of the force to attack Kapararidze and African levies were recruited from Tete and Sena with the help of the Dominicans, especially Fr Luiz.

Once this force reached the feira at Ruhanje (Luanze) they declared Mavhura the rightful Mutapa and placed themselves under his command. The force of 15 – 30,000 African levies and 250 Portuguese marched from Ruhanje to Massapa without any resistance, but at Massapa in 1628 they met Kapararidze’s army numbering 100,000 warriors.

On their first encounter, Kapararidze’s army quickly disengaged, but in May 1629 they met again and fought and Kapararidze’s army suffered heavy losses. Fr Gomes left a descriptive account: “at the Monomotapa court a lot of spoil was found, silk, blankets, rich tents, gold coins of all kinds and besides, a lot of gold. The king fled and with only a few of his men he wanted to fight our army. Some of them came forward first with the tails of some animals with medicines to blind the Portuguese and their people; [then] there also followed [others] with a big copper kettle drum covered with rich silk cloth and lion skin skins and filled with various revolting things, [like] the hands and feet of a human body, fingertips, ears of tigers and lions, etc. and the Africans believed that when Angoma, as they call it, were touched, all our people would fall flat on the ground. Our kaffirs were so afraid of this that instead of [being] black they looked white. Two Portuguese went to stop that nonsense and they came so near those were the medicines that [when] they were a shot’s distance from them, they fired so hard that they threw them [the others] on the ground. [But] notwithstanding the great commotion [that followed] the Angoma was still to be conquered, it was carried on the stand by twelve men who had been especially charged with that. The kaffirs, on seeing they were in trouble, gave the signal to advance by playing the Angoma and a great yelling could be heard from the enemy camp. It sounded like the Day of Judgement… The Portuguese in front started shooting their guns and hit the Angoma and as it was important to finish with it, they rushed up to it.”

The downfall of Massapa from the 1630’s

Pikirayi says the above events in the 1630’s led to Massapa beginning to lose its importance in conjunction with a breakdown of order in the Mutapa state that had been fuelled by the Portuguese meddling in its politics.[x] Its final downfall would however be at the hands of the Rozvi ruler Changamire Dombo who attacked and destroyed the Portuguese feira at Dambarare and Massapa in November / December 1693.

Mavhura Mhande (Dom Felipe) (1629 – 1652) replaces Kapararidze, but as a Portuguese vassal

Following their victory the Mavhura forces entered the dzimbahwe where a victory mass was celebrated and a church dedicated to Our Lady of the Rosary. Although there was some division amongst the Portuguese about whether Mavhura or Dom Filippe, the son of Gatsi Rusere should be appointed Mutapa, in the end Mavhura was declared the Mutapa in May 1629. However, he was required to sign a treaty of vassalage to the Portuguese crown. Although Nyambu Kapararidze has been displaced as ruler, he always remained a threat.

The ’capitulations’ in the 1629 Treaty

In the treaty of vassalage of 24 May 1829 Mavhura:

- Agrees that that he received his throne in the name of the King of Portugal whose authority he acknowledges

- Agrees to all the Dominicans converting his subjects and to treat converts with great respect

- Agrees to expel all Muslims from his territory within one year – any still remaining may be killed and their property confiscated by the Portuguese

- Agrees to allow Portuguese ambassadors, contrary to local custom, to enter his dzimbahwe in full armour and they may speak to the Mutapa seated from a chair without clapping their hands

- Agrees that Portuguese citizens at his dzimbahwe will be given a kaross to sit on rather than a chair

- Agrees to show great respect to the captain at Massapa who will in future live at the Mutapa’s dzimbahwe rather than at Massapa

- Agrees to consult the captain on any matters of war and peace and allow the captain to be present at any time without bringing a present

- Agrees that certain lands will be granted to the captain

- Agrees to allow Portuguese traders or their vashambadzi to travel freely within his territory without paying tolls to the Mutapa, or his vassal rulers

- Agrees to grant land containing gold and as many gold-mines as possible within his lands and disclose their locations to Portuguese traders

- Agrees to search for the silver mines of Chikova and reveal their location to the captain

- Agrees to pay three pastas (1.28kgs) of gold every three years to the captain of Mozambique Island. (i.e. now the Mutapa will pay kuruva to the Portuguese)

- Agrees to allow the lands at Tete to be annexed to the Portuguese crown

In acknowledgement of these pledges, the Portuguese administration sent clothes, a canopy, a high-backed chair and stool, all in red velvet with gold fringes to Mutapa Mavura plus a sword and cape, crown and silver sceptre.

Conversion of the Mutapa

After eight months of teaching by Fr. Luiz, Mavhura and his wife and some of the senior court were baptised with Mavhura given the name of Dom Filipe and his wife Dona Giovanna. One of the sons of Kapararidze was sent to Lisbon, baptised Dom Miguel and educated at Goa where he became a priest and died sometime after 1670.

Only token recognition of the ’capitulations’ listed above was given by Mavhura; but in reality the continued threat from Kapararidze made him a Portuguese ally.

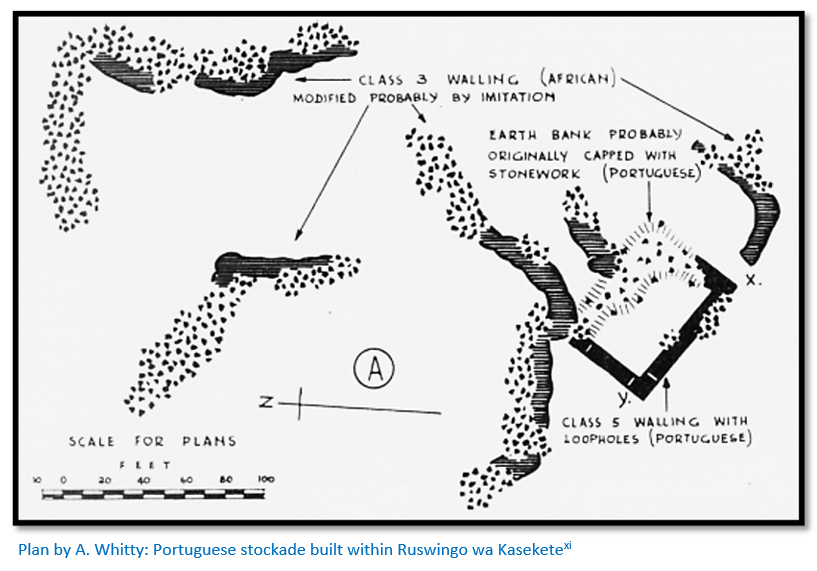

Ruswingo wa Kasekete lies below the Zambesi escarpment. The stockade was built by the Portuguese in 1631 for Mavhura Mhande for his personal protection so the complex is probably his palace.[xii]

1631 – the Mavhura / Portuguese alliance suffers its worst military disaster

Kapararidze had suffered defeat but plotted his comeback. Mavhura’s efforts to expel the Muslims from the Mutapa state drove them to become allies with Kapararidze. In 1631 a Kapararidze / Muslim alliance fought a battle with Mavhura Mhande’s army – reported by Sousa in Asia Portuguesa – having over 6,000 casualties of which 300 – 400 were Portuguese which he attributes to rivalries in the Portuguese chain of command. Axelson states this would make it the worst military disaster the Portuguese suffered in south-east Africa.

The Dominican friars including Luiz de Espirito Santo are killed

Mavhura escaped the battlefield, but Fathers Joao da Trindade and Luiz de Espirito Santo were captured. Trindade was wounded and then killed. Kapararidze believed Santo had played a big part in his misfortunes and told him to pay homage zumbaya (zvambayira) by crawling on his stomach. Santo refused and declared his loyalty to Mavhura, the Portuguese crown and Christianity and compared Kapararidze to Lucifer.

Kapararidze became tired of being harangued and ordered the friar to be put to death.

The interim rule of Kapararidze as Mutapa

Kapararidze tried to persuade Mavhura to surrender and avoid further bloodshed, but Mavhura refused. Kapararidze used the resentment that had been built up against the Portuguese plus strong-arm tactics to stir local people to revolt and this forced the Portuguese to take refuge in the settlements of Tete and Sena and their feiras.

The new captain at Mozambique Island Diogo de Sousa de Menezes began a military campaign at Quelimane and pacified the lands as far as Sena.

His forces then invaded Manyika where he killed the ruling Chikanga and put another in his place who agreed to become a Portuguese vassal and a Christian, pay a kuruva and acknowledge the Mutapa state’s dominance.

Menezes then recruited many warriors from the Maravi country north of the Zambesi and turned them on Kapararidze. In the first engagement according to Fr Lucas de Santa Catharina in Historia de S. Domingo Mavhura had a vision and the story of the cross is said to have seen inspired his army onto victory.

Kapararidze then formed a new army and challenged Mavhura. This time Mavhura’s force was joined by Menezes force fresh from Manyika which included Portuguese musketeers.

Kapararidze went confidently into the second battle, but his army took many casualties and many of their women, cattle, arms and supplies were captured. Kapararidze fled north across the Zambesi and found refuge in Maravi country, but despite the heavy defeat and loss of power from June 1632 he remained a constant threat until as late as 1652.

Portuguese influence is dominant in the period 1632 to 1684

Mudenge writes that the Portuguese in this period did not govern the Mutapa state, but they held the balance of power. The presence of Kapararidze as a threatening rebel allowed the Portuguese to play a pivotal role in the Mutapa state.[xiii] He says that the situation allowed the Portuguese to exploit the situation to their full advantage and the civil wars that preceded 1632 had consequences from which the Mutapa state never really recovered.

The Portuguese crown refused to pay any kuruva saying that by the 1629 Treaty Mavhura became a vassal of the Portuguese crown and that it was inappropriate that the Portuguese king should pay tribute to his vassal. Instead they allowed Mavhura to import cloth worth 3 – 4,000 meticals without paying duty, although it appears he never did.

The 1629 Treaty also cut away a number of tariffs that traders had to pay to the Mutapa previously. One of the duties of the ‘captain of the gates’ had been to collect a tariff of 5 percent on all trade cloth on behalf of the Mutapa…this tariff on traders was now abolished and meant the Mutapa could no longer reward his vassals.

Mutapa Mavhura’s conversion to Christianity loses him support amongst the populace

The fact that Mavhura converted to Christianity led to a general increase in the number of churches and missionaries within the state. By 1631 the feiras at Ruhanje, Dambarare and Massapa all had churches and resident Dominican friars and there was even a church at Mavhura’s dzimbahwe. Further churches were said to be at Matafuna and Chipiriviri and in Manyika there were churches with friars at Vumba, Chipangura and Matuka.

The friars state that women and children were easier to convert than men; women because it raised their status by insisting on monogamy. However Mudenge writes that Mhondoro and Dzivagura cults were opposed to Mavhura and his Christian ideals, the friars stating: “these Mocarangas are so attached to their rites” and that Christianity never really posed a serious threat to local beliefs. The Dominican friars role in the Mutapa succession and in court politics was of much greater significance.

The growth of the prazo system posed a significant threat to the Mutapa state

The 1629 Treaty meant that Mutapa Mavhura gave up his authority over the land around Tete and by 1634 the captains at Tete and Sena could call upon 8,000 and 30,000 warriors at each. It is known that the prazo-system extended along both banks of the Zambezi, along the Mazowe and Ruenya and into Manica…see the map below…although Mudenge claims that that the Portuguese prazo system extended into the Mutapa state as far as their trading post at Maramuca, near present-day Chegutu.

However, he offers no evidence of this and no other authors, as far as I know, have made the same claim. He goes on to say the presence of these prazo-holders within the Mutapa state undermined both the authority of the Mutapa and the Portuguese crown; their indiscipline and lack of co-operation making the political system unstable.[xiv]

He goes further and states the prazo-holders killed and harmed Mutapa subjects: “almost at will” and these activities “risked rousing the Mutapa subjects into revolt and reduced gold-mining activities as people abandoned gold-producing lands out of fear”[xv] However no sources are quoted, and no evidence produced. There is no denying the prazo-holders in the Zambesi valley acted poorly, but no sources claim the same happened within Mukaranga.

Violence becomes more extreme with the introduction of firearms

In 1505 the Portuguese King, Manuel I instructed Francisco De Almeida, a captain major at Sofala, not to sell arms to the Arabs [or presumably anyone] ostensibly to give Portuguese nationals in the interior an added advantage.[xvi]

But Portuguese trade in the interior led to the introduction of firearms which not only increased armed conflicts but made them deadlier in the Mutapa state. Flintlock guns were traded for gold, ivory and agricultural produce and this changed the nature of warfare in the region where formerly the bow and arrow and spears had previously been the main weapons and were much less deadly and destructive.

The Portuguese try to exploit their increasingly important role in the Mutapa state

In 1633 the viceroy Conde de Linhares wrote a glowing report on the wealth of the region and said that just 500 soldiers and 2,000 Portuguese families were needed to exploit the famed gold and silver mines of Mukaranga, Quiteve (Uteve) Manyika, Guruuswa (Butua) and Chikova.

A new effort was made to discover the silver-mines of Chikova. On 8 January 1636 Francisco Figueredo de Almeida (assayer) and Dom Andres de Vides y Albarado (administrator) left Tete arriving at Chikova on 28 January with their Portuguese and African followers. Antonio de Castilho had been sent to Mutapa Mavhura in advance to collect guides but returned without any. A soldier, familiar with the route, Diogo Velho, was sent to Mavhura to request a guide a soon as possible.

Velho returned with a court official who on his arrival pointed out a hill where he said silver was to be found. The Portuguese dug approximately four metres without encountering the metal and on being questioned further the court official pointed out three more locations on the same hill. No silver was found at these places, and not surprisingly, the court official took off from Chikova back to Mavhura’s dzimbahwe.

On being scolded and questioned the court official said he knew of no more locations where silver might be found, but had an uncle, Mavareka, who knew. Both individuals were escorted down to Chikova to show the mines to Almeida. After three visits to the hill, no mines were located, Mavareka saying he needed to be in a trance state for the spirits to show him the mines in his dreams. Almeida called the expedition off as a fruitless exercise.

Mavhura continues to feel threatened by the rebel Kapararidze

In 1635 Mavhura told the Portuguese that Kapararidze was threatening to bring his army from the north across the Zambesi river and again in 1643 there were new threats that Kapararidze had spies on the south bank preparing the way for his army into Mukaranga.

On both occasions the Portuguese response was to send 40 soldiers to Mavhura’s dzimbahwe to garrison a fort and act as his personal bodyguard. The cost of the fort was paid for by using funds which formerly were paid for the boca (‘mouth’) and the kuruva with Filippe III (1605 – 1665) reporting its function being: “to maintain the Monomotapa in submission to my authority, and…also to serve to shield and defend him from his enemies.”

In 1643 the merchants at Sena agreed voluntarily that each trader entering Mukaranga should pay one bretangil of cloth for every four carjas of cloth (i.e. 1/80th) brought into the territory to support the Portuguese garrison. When in 1646 the Portuguese crown suggested the merchants pay one carja for every four carjas of cloth (i.e. ¼th) they imported, it was greeted with much scepticism.

In 1644 Mavhura signed another treaty of vassalage with Sisnando Dias Bayao for the Portuguese crown and agreed to pay an annual kuruva of an ivory tusk.

Mavhura dies from an accidental gunshot wound in 1652

On 25 May 1652 Mavhura died from a gunshot wound. We have seen that under the Shona succession system he was not a ‘usurper’ being the brother of Gatsi Rusere and with more right to the Mutapa title than Gatsi’s son Kapararidze.

However because of the threat from Kapararidze he was forced to rely on Portuguese protection and his conversion to Christianity alienated him from his own people.

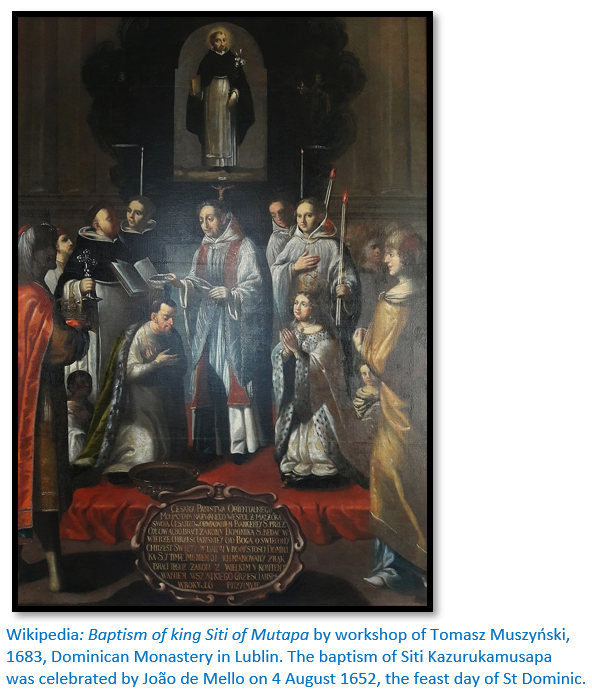

The new Mutapa Siti Kazurukumusapa (1652- 1655)

Contrary to Shona succession rules, Mavhura is succeeded by his son, then just 13 years old. Although brought up a Christian, Siti had not been baptised so as not to antagonise the traditional Shona religious authorities.

On his father’s death, the Dominican friars led by Fr Ignacio de St Thomas, the vicar at Mavhura’s zimbabwe had rushed to the kraal where Siti was living some distance from the court. Because they were wary of Kapararidze’s plans, Fr João de Mello, Siti’s personal tutor and counsellor, went to Dambarare, the chief trading centre at this time to ensure the succession to the Mutapa throne would be successful.

The Father returned to the dzimbahwe, that was in Dande at this time and on 4 August 1652 Siti along with the major court officials were baptised, Siti as Dom Domingo as this was the saint’s feast day. Siti himself described the event: “on this day we issued from our palace with great pomp, accompanied by all the nobles, the soldiers of the garrison and by the aforesaid religious who walked on each side of our person. [We were] richly decorated and prepared with great magnificence…this baptism was celebrated with great rejoicing, especially by those of our court, who with musical instruments and festive dancers gave incredible signs of joy.”

The event was celebrated in Portugal as a great victory: “in the convent of Saint Dominic at Lisbon, the chief house of the province, the event was celebrated with the highest Catholic demonstrations, the blessed sacrament being exposed, with solemn high mass, at which King Joao IV of happy memory assisted with all his court, favouring the religious of that house on that day with singular marks of His majesty and greatness.”

Siti’s reign was short as he died in 1655.

Dom Afonso (1655 – 1663)

Siti’s successor was Dom Afonso, his uncle and the brother of Mavhura following the traditional succession line. It is clear that the Dominicans helped in the succession as Afonso asked that the chaplain at the dzimbahwe, Fr Marcello be rewarded and that the Dominicans should be favoured by the Portuguese crown.

Dom Afonso appears to have given Antonio Roiz de Lima and other Portuguese traders land rights around the feira of Dambarare. These traders built up a powerful army and declared themselves independent of the Mutapa and then declared war on Dom Afonso. When the two armies faced each other, his own courtiers turned on Dom Afonso and assassinated him. Barretto in Informação writes: “the encozes, who are the lords or chief kaffirs of that kingdom, killed the poor king (a thing unprecedented among the kaffirs) for fear of the Portuguese and came and subjected themselves to them that they might make whom they chose king.”

The new Mutapa, Kamharapasu Mukombwe (1663 – 1692)

Mukombwe was a younger son of Mutapa Mavhura and succeeded with the approval and probably the support of the trader Antonio Roiz de Lima. Although Mukombwe was said to be ‘sufficiently feared’ even by the Portuguese traders, land granted to the Portuguese seems to have become an issue as it did with his predecessor, Dom Afonso.

Mukombwe gave the lands at Maramuka (Maramuca) to a trader Gonçalo João but also gave a trade monopoly to the same lands to Antonio Roiz de Lima and a mulatto priest, Fr Simao Gomes. The last two began encouraging local chiefs at Maramuka who lost their lands to Gonçalo João to rise up against him and even sent them arms and men. [See the article Maramuca, a Portuguese Feira dating from 1660 – 1680 under Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

Gonçalo João was taken by surprise and defeated losing men and property. Barretto writes: “the comedy of it was, that after doing him this good turn they accused Gonçalo João of having stood up Maramuca with war and caused them the loss of many pastas. The matter was tried before the tribunal of Dambarari (sic) which was worthy of them and Gonçalo João was condemned to lose all he possessed.”

Mukombwe made a number of appeals to the governor at Mozambique Island for the return of the lands around Dambarare saying the chiefs and people were too frightened to work the gold-mines. The governor, Antonio de Mello e Castro sent Francisco Pires Ribeiro to sort out the problem, but he backtracked saying if those traders were: “deprived of their lands and vassals [they] would be scattered and powerless and of no service” to the Portuguese crown.

By the 1670’s reports of “distrust and other suspicions” were being made about Mukombwe as he had managed to bring some of the rebellious Tonga under his control and even the rulers of Barwe and Manyika acknowledged they were his vassals.

Mukombwe in a letter dated 8 June 1679 to Afonso VI complained his Dominican chaplains were only present at his dzimbahwe for three months in the year, the rest they spent at the gold-fields. He explained that life had been hard for everyone south of the Zambesi; smallpox, measles and plague had much reduced the population, fields were being left unharvested and there were few left to work the gold-mines. Trade was so poor the feiras at Hwangwa and Dambarare had been abandoned. Axelson estimates the numbers of Portuguese in the Mutapa state may have been reduced to only fifty.

Relations between Mukombwe and the Portuguese remained troubled; he constantly threatened rebellion, the gold trade remained subdued and he was living like a true Shona, observing traditional rites and never going to church or saying confession.

The Mutapa state is becoming fatally weakened

By the 1680’s other outside forces were threatening both the rule of Mutapa Mukombwe, and the Portuguese. The civil wars that began with Gatsi Rusere and Matuzianye and which continued between Mavhura and Kapararidze assisted the Portuguese to exploit the weaknesses, but also fatally undermined the political system of the Mutapa state.

Defections from the Mutapa state continued throughout the period. In the late 15th Century Butwa (Guruuswa) broke away (if indeed it can ever be considered to have been controlled) followed by the vassal state of Quiteve (Uteve) in the 16th Century, as did Maungwe.[xvii] The vassal states Barwe and Manyika[xviii] broke away in the 17th Century, followed by Dande in the 18th Century leaving only the Chidima province in the 19th Century.

Conclusions to be drawn

The diversion of resources from agriculture may have weakened the Mutapa state

It is possible that too much emphasis on gold-mining driven by Portuguese demand for the metal undermined the Mutapa state by diverting labour resources away from agriculture which was the fundamental economic basis of their economy. This may have reduced the inflows of tribute from vassal states to the Mutapa’s dzimbahwe. The Portuguese were no longer paying the kuruva and the loss of taxes levied on Portuguese traders meant a weakened Mutapa political system.

The Portuguese king Sebastian is warned about trying to take control of the Mutapa state

Fr Monclaro wrote in 1569: “Your Majesty may draw a revenue from this country by leasing the river, the profit of which will increase greatly from the trade in squares of calico, which is now beginning, gold will be current as it has ever been in large quantities, and orders may be given to regulate the commerce. For this purpose, I say it should be leased, because the officials now draw all the profit; but if the trade is not carried on by Your Majesty, but by a lessee, something will be saved, and not so little but that the whole of this government may yield in gold, ivory, ambergris, which is found on the coast of Sofala, at Cape Correntes, and Inhambane, and the seed pearls which are also found there, more than a hundred thousand cruzados, without any expense to the exchequer. To endeavour to conquer these territories is to waste money and Portuguese, and as it is impossible to attend to so many things none of them are properly mastered and executed. He who would have all loses all. Omne regnum in se divisum, &c.”[xix]

The Mutapa’s lost control of the trade network and were forced to negotiate new trading arrangements with the Portuguese merchants from Sena and Tete and even those broke down in the violence of the 17th Century.

Portuguese written accounts mention the existence of the Massapa trading centre as part of a regional network of centres called feiras and frequented by Portuguese and other traders from the early 16th Century.

Last days of the Mutapa State on the northern Mashonaland plateau

The first Rozvi Changamire invasions in 1694 seriously weakened the Portuguese within the Mutapa state and brought all their trade to a halt. A second Rozvi Changamire invasion in 1702 seriously destabilised the Mutapa state which was forced to move from the northern Mashonaland plateau to the Zambesi lowlands. The northern Mashonaland plateau region became depopulated and was lost to Mutapa control. Further wars followed in the period 1735 to 1804 which led to a more general population decrease and a waning of Mutapa power and influence.

In the 19th Century the prazo-holders and their Chikunda mercenary armies claimed as much land as they could along both banks of the Zambesi Valley and inland they overwhelmed the Mutapa and their allies and pushed them into remote areas east of the present Zimbabwe / Mozambique border despite some limited success in hit and run tactics and a guerrilla war. The violence of the prazo-holders and their Chikunda armies against the remnants of the Mutapa state was a persistent feature of this period and by the end of the 19th Century the Mutapa state barely existed.

The rise of the Rozvi 1684 – 1760; Battle of Maungwe (Mahungwe)

The Rozvi rise is linked to the “wily and cunning Changamire Dombo” who began his attack on the Portuguese in June 1684 at the battle for Maungwe in the Manyika region of the Mutapa state. The battle continued all day with the Rozvi’s bows and arrows against the Portuguese with their arquebuses fighting alongside their local auxiliaries. Fr Antonio Conceicao in his Tratado wrote: “a proud enemy who dared to measure his bows against our muskets.” Several times the garrison was nearly overrun, but the longer range of the arquebus inflicted heavy casualties on Dombo’s forces.

Dombo ordered the women accompanying his force to cut as much firewood as they could and when night fell the fighting ceased. The Portuguese came out of their fort and decided to camp in the battlefield until the following day. At 1am the Portuguese found themselves surrounded by a wall of fire fed by the cut firewood, their local auxiliaries fled in disarray and the Portuguese forces then withdrew. Fr Conceicao again: “he was so wily and cunning that after being defeated by our arms, he vanquished us with his stratagems.”

Since his army was much weakened from the previous days’ fighting Dombo did not pursue the Portuguese and their auxiliaries and they collected what they could from the battlefield. In the meantime the Mutapa had sent an army to: “the lands of Butua where this black man [Dombo] called himself king.” Dombo wreaked havoc in Mukaranga before returning to Butua and destroying Mutapa Mukombwe’s army and Fr Conceicao writes that Portugal’s African auxiliaries trembled: “only at the mention of his [Dumbo’s] name.”

Changamire Dombo consolidates his position in Butua

In 1684 great efforts were made by the Portuguese to strengthen the defences of their feira at Manyika, but no attack came from Dombo. In 1685 the governor Caetano de Mello de Castro was writing to the viceroy that Dombo continued to pose a threat, but events show that no further attacks on the Portuguese were made until 1693.

Mutapa Mukombwe dies in 1692

Mukombwe was succeeded by his brother, Nyakaunembire, but the Portuguese had groomed Nyamaende Mhande (Dom Pedro) a son of Mukombwe, as his successor. As a practising Christian, he was the perfect choice for the Portuguese and they looked on Nyakaunembire as illegitimate, although in the Shona tradition the succession was correct.

In the face of Portugal’s threats and with his dzimbahwe located between the feiras of Dambarare, Chitomborwizi and Massapa, Nyakaunembire appealed to Dombo for help. Changamire Dombo was only to keen to assist in vanquishing the Portuguese and to ensure that Nyakaunembire would be dependent on the Rozvi to cling to his throne.

The Rozvi attack Dambarare and extend their hold on the Mutapa state capturing the gold-fields from Butwa (Butua) to Manyika

In November 1693 for the second time Changamire Dombo’s forces swept eastwards onto the Mashonaland plateau with the Portuguese in their sights. The feira at Dambarare was designed for trade, not defence and only 60 people were present, all being civilians. For defence they grouped together at the house of Antonio Rebello, the richest trader, but all were quickly overwhelmed and killed with some allegedly taken prisoner. All the buildings, including the churches were destroyed. Apparently the two Dominicans had their skins flayed and displayed at the head of Dombo’s army to strike terror into his enemies. The bodies of dead Portuguese were disinterred from the cemetery and made into medicine to make the Rozvi soldiers invincible.

The Portuguese and Indian traders at Chitomborwizi and Hwangwa fled to Nyakaunembire’s dzimbahwe where they heard that the captain-major of the garrison, Manoel Pires Saro, planned to murder the Mutapa for his treachery. But the required reinforcements did not arrive, so the Portuguese and their followers fled to the safety of Tete and Sena. The now abandoned feiras at Massapa, Matafuna and Ruhanje were destroyed by Changamire Dombo’s forces. The Mutapa state, including Manyika were now firmly under Rozvi dominance.

Nyamaende Mhande (1694 – 1697) seizes his chance and overthrows Nyakaunembire

At Tete and Sena there was much confusion and panic amongst the people and calls to the viceroy at Mozambique Island for additional soldiers and supplies. Nyamaende Mhande saw an opportunity to regain the Mutapa throne and left Manyika with his brother Chirimbe and came to Tete to unite with the Portuguese forces under Manoel Pires Saro.

The Portuguese forces were unable to unite with Mhande whose forces then had to defend themselves against hostile Samungazi Tonga around Chambo…Fr Monclaro called them the Mongas. Mhande allied himself with the widow of a prazo-holder, Francisco Pinheiro de Faria and defeated Nyakaunembire’s court official who came to claim the widow’s lands.

Mhande learnt from his captives that Nyakaunembire had fallen out with Changamire Dombo and would no longer come to his rescue, so he advanced on Mukaranga basing himself at Mt. Chiquiziri which lay between the destroyed site at Dambarare and Nyakaunembire’s dzimbahwe. With news of Mhande’s success, the Portuguese sent reinforcements under Francisco Machando Tavares to join Mhande.

At this news Nyakaunembire fled to Changamire Dombo who was engaged in taking Manyika and was not prepared to be distracted by the Mutapa’s troubles. In 1695 Dombo destroyed the Portuguese trade fair at Massikessi (Macequece) and defeated the ruling Chikanga in Manyika and replaced him with his own puppet. Mudenge states the new ruler came from outside Manyika and his name was Nyamubvambire, which is rather similar to Nyakaunembire. If so the deposed Mutapa then became the ruler of Manyika.

Changamire Dombo now completely controlled all the gold-producing territory from Butwa (Butua) to Manyika.

Mhande’s reign came to an end in 1697 with his death. The Portuguese records show nothing notable except that the myth of the silver mines at Chikova crops up again. When news of their ‘rediscovery’ came to Portuguese ears, they demanded ownership which was given, but the chiefs of Chikova refused to divulge their whereabouts.[xx]

Mutapa Chirimbe (1697 – 1702 and 1703 – 1711)

Mhande was succeeded by his brother Chirimbe , although the Portuguese once again had a preferred candidate – his son, Mapeza (Mapeze) or Fr Constantino do Rosario as they wished the silver mines grant to be re-confirmed.

Mapeza had been baptised at Tete in 1699 and studied at Goa for the priesthood and then exiled to Macau for some religious misdemeanour, but after petitioning King John V in 1709 returned to Goa.

In 1702 Chirimbe was ousted by Samutumbu Nyamhandu[xxi] with the help of the Rozvi Changamire, but in the next year Chirimbe became Mutapa again with Portuguese help and who provided for his security by establishing a small garrison at his dzimbahwe to protect him.

Chirimbe’s reign continued to be troubled. In 1708 Samutumbu Nyamhandu took possession of some of the prazos near Tete after his daughter was kidnapped by the Portuguese. During the struggles António Simoes Leitao, the general of the Rivers of Sena, was killed. His successor, Rafael Alvares da Silva brought peace by sending gifts to Chirimbe that were then distributed to his vassals.

Mutapa Chirimbe died about 1711.

Mutapa Boroma Dangwarangwa (1711 – 1712)

Boroma was Chirimbe’s brother and inherited the title in the customary Shona succession, but once again the Portuguese chose to consider him a usurper and decided to install Mhande’s son, Mapeza or Fr Constantino do Rosario. Constantino knew that his uncle had a greater right to succeed than himself and turned down the offer saying as a Dominican he had abandoned all worldly interests.

Mutapa Boroma proved friendly to the Portuguese but was killed the year after his succession by Samutumbu Nyamhandu with the help of the Rozvi Changamire. The Portuguese had been unable to support him because the governor at Sena, Jacome de Marais Sarmento had embarked on a military expedition to Quiteve (Uteve) to punish Sachiteve Sakakate (Sacacate) who had shown open support for the Rozvi Mambo.

Samutumbu Nyamhandu (1712 – 1718)

The lands of Mukaranga were so devastated by the Rozvi invasions that Samutumbu was reluctant to be installed as Mutapa but was forced to accept by the Rozvi Changamire who left one of his captains at the dzimbahwe to ensure Samutumbu toed the Rozvi line. Thus the Mutapa was induced to become a Rozvi puppet.

Samutumbu was not permitted to sign any peace treaties or trade with the Portuguese or attack any of the vassal kingdoms without the authority of the Rozvi Changamire and was reduced to the status of Rozvi vassal. However he communicated with the Portuguese in secret and when he finally invited the Portuguese to man a garrison of troops at his hondor, then at Nyapende, the Rozvi threatened, but did not punish him.

Although Samutumbu had been educated at Tete, he resisted efforts by the Portuguese to re-enter Mutapa as he had not taken full control of the state and feared his vassals would rebel against him and ally with the Rozvi. The Governor at Mozambique Island plotted to replace him and take back control although the captain of his garrison, captain Bartholomew Alvares advised his superiors the plan was suicidal.

The Portuguese launched a secret military mission from Tete, but Samutumbu was informed and laid a successful ambush during which Alvares was killed. In addition to Portuguese treachery, the Mutapa state suffered a devastating smallpox epidemic and then a devastating drought in 1714 which caused widespread famine.

Samutumbu’s reign lasted until 1718; he appears to have accepted baptism and largely mended fences with the Portuguese as the viceroy writes: “I regret that your highness has not experienced from all my vessels the consideration that I commanded them to give you” and assured Samutumbu that the new Portuguese garrison would be absolutely loyal to him and defend him against any usurpers.

Mutapa history after 1719 – 1750 is one of internal struggle

After Samutumbu’s death the Portuguese versions of events do not always agree. Mudenge opts for the viceroy’s version of events since he was closer to events happening on the ground. In 1719 Francisco de Mello de Castro writes to the Lt. Governor of Mozambique Island Antonio Cardim Froes: “as the nomination of a king Monomotapa is necessary, let it be made with due circumspection, seeing that the prince having the most right is crowned, if he be not a declared enemy, as thus God will bless the election. The same care must be exercised in preventing private persons from taking part in these elections…A king Monomotapa capable of governing his empire and his prince Inhapando [Nyamhandu] has justice on his side and from the circumstances which you report to me I presume he has been crowned.”

Once again the Portuguese were interfering in the Mutapa succession and opposed to Joao Nyamhandu succeeding his father but Mudenge does not give details of their preferred candidate for the Mutapa throne.

Mutapas Zinyemba and Nyatsutsu (1718 – 1723)

Mudenge says it was a troubled time in the Mutapa state and the Mutapas ruled for very short periods. The Rozvi decided they could not maintain control of the shifting politics of the Mutapa state and left for their original power base in Guruuswa (Butua) in the west.

The Mutapa state is expelled from the Mashonaland plateau and is confined to the Dande / Chidima area near Tete in present-day Mozambique

Moving his dzimbahwe to the region of Chidima establishes a boundary between the region under Portuguese influence and the region controlled by the Rozvi. This boundary survived until the 19th Century and formed the basis for the boundary commission in 1891 establishing the present-day border between Mozambique and Zimbabwe.[xxii]

The Rozvi forbade individual Portuguese from entering Mashonaland again, but they did permit the ancient trade fair at Massi-Kessi (Macequece) to continue and at the newer fair at Zumbo near the Zambesi / Luangwa river confluence.

At this time the Mutapa state is politically unstable leading to a rapid succession of rulers and characterised by numerous civil wars fought between the various contenders for the throne. Pikirayi writes that: “the emergence of smaller, semi-independent polities controlled by one or another of these houses demonstrates the lack of a strong central authority. The state was no longer able to defend itself from these petty chiefdoms, which grabbed parts of the plateau not allocated to others during the time of Mutapa [Kamharapasu]

Mukombwe in the middle to late seventeenth century.”[xxiii]

The Mutapa state capital is constantly on the move

Pirikayi writes: “Traditional histories suggest that beginning in the eighteenth century the state capital gradually moved from the [Mashonaland] plateau toward the Zambesi valley. The capital once located on Bare Hill in the upper Ruya, was moved to Tsokoto across the Mazowe, then to the Nyamhende river (connected to Mutapa Joao [Samatambira] Nyamhandu I and dated to 1719) in the Zambezi lowlands and finally to a hill near Tete (possibly Songo) In 1723 Nyamhandu relocated his capital to the Mavangwe Mountain near Chikova.”[xxiv]

Pikirayi states these capitals did not have the large populations of (say) the dzimbahwe at Baranda Farm (Massapa) Those resident now only consisted of court officials, royal wives and a garrison of about 500 nyai (young fighters)which might increase in threatening times. He writes: “They resisted and sometimes threatened the prazos and managed to repossess some lost land.”

Samatambira Nyamhandu (Joao V) (1723 – 1743)

In 1723 Samatambira moved his dzimbahwe to the Mavangor (Mavange) hills at Chikova north of Tete in present-day Mozambique. Portuguese records say his reign, in contrast to the previous five years, were peaceful. Fr Simao Santa Thomas visited the Mutapa at his new capital and said he was received: “with great honours and demonstrations of joy” giving the father the seat of honour whilst the Mutapa took a more lowly one leading Fr Thomas to remark: “such veneration in a king of the kaffir race shown to one prelate of the church is much to be admired.”

After visiting the churches at Zumbo and Mixonga Fr Thomas returned to Samatambira’s dzimbahwe. At Zumbo he met Portuguese traders who told him their children and relatives had been taken prisoner by Changamire Dombo in November 1693 and they were probably still living without receiving the sacraments. Fr Thomas asked Samatambira if he would correct the situation by handing over the old feiras at Dambarare, Massapa, Ruhanje back to the Portuguese, but the region would first need to be pacified so they could live without fear.

Samatambira discussed the proposal with his council, and they agreed to the request and asked for three bares of cloth to pacify the chiefs around the feiras and two barrels of gunpowder to arm his warriors. The captain of Mocambique Island, Antonio Barboza Leal, was happy to agree as the re-opening of the feiras would stimulate trade. The captain agreed to levy the traders at Sena and Tete for the cloth and gunpowder as the proposal was in their interest. However, everybody had different ideas as to which feiras should be opened first and nothing further came of the proposal.

Traders from Tete did go to re-establish the feiras in 1737-8 and 1743-4, but the returns were low and after Samatambira’s death some of the traders were attacked and robbed and the feiras were abandoned once again.

Mutapa Karidza (Kariza) (1743 – 1744)

Karidza was the blind son of Boroma Dangwarangwa (1711 – 1712) He was quickly challenged by Chikoka, the father of the future Mutapa Ganyambadzi. Karidza managed to escape across the Zambesi river into Maravi country where he lived as a refugee.

Chikoka (1744)

Almost nothing is known about his short reign

Kabwe (1744)

Again, almost nothing is known about his reign as Mutapa, except that he was violently removed by Debwe II, son of Samatambira Nyamhandu (Joao V) (1723 – 1743)

Debwe II (1745)

According to oral tradition he unleashed such violence that its effects were still being felt in the 1760’s. The 1743 / 4 troubles were so devastating that Francisco de Mello de Castro states the Portuguese asked the Rozvi for help.

Debwe Mupunzagutu (1746 – 1760)

Debwe II on his death was succeeded by his brother Mupunzagutu. Mudenge writes that he was addicted to marijuana and enjoyed playing his mbira. Peace was restored after Mupunzagutu declared himself an ally of Portugal. The captain appointed to man the garrison at Mupunzagutu’s dzimbahwe, Manoel Dassa de Castelbranco, fell out with the Mutapa and in July 1757 had to be given instructions on political behaviour. They included:

- To do everything in his power to ensure Mupunzagutu’s court officials did not brief him against the Portuguese

- Ensure the Portuguese soldiers at the dzimbahwe behaved well

- Any leave taken by the Portuguese soldiers had to be taken at Tete

- Any political information from the Mutapa’s court should be sent quickly to the governor

- He was to apologise for the kuruva being less than customary.

However by November 1757, with a few months of his instructions, the captain was in prison for having murdered the factor and having misspent the cloth that was meant for the soldier’s salaries. Castelbranco was succeeded as captain by José Antonio Brabo and then Coronel Dionizio de Mallo de Castro who wrote that the period was lawless with many Portuguese traders being robbed by the Mutapa’s vassals.

In 1760 Mupunzagutu was assassinated at his dzimbahwe by his brother Zindove (Zindabe)

Zindove (1760 – 1761)

Little is known about this period except that civil war raged once again and the remnants of the Mutapa state divided into two, Dande and Chidima. Dande split off, whilst Chidima was ruled by the descendants of Mutapa Boroma Dangwarangwa (1711 – 1712) and Mutapa Samutumbu Nyamhandu (1712 – 1718) who continued their fight for succession.

Mutapa State is forced to Chidima followed by years of succession and the end of the Mutapa state 1761 – 1917

This was the beginning of a new civil war with Zindove’s reign contested by his brother Kamota (Camota) and with his defeat Zindove was forced to flee to Dande to seek reinforcements. Instead, Derere, king of Dande had him killed.

As the Mutapa state was no longer in present-day Zimbabwe, this article concludes with its final years and demise. Portuguese records are sparse too as Chidima was just a transit area between the fiera at Zumbo to the west of Chidima which was re-opened in 1820 and the settlement at Tete.

Pikirayi states the area still ruled by the Mutasa state experienced serious droughts in the 1920’s and managed to survive the Mfecane of the 1830’s. The Ngoni under Zwangendaba settled at Satwa, south of the Mazowe river in 1833 until they moved on and crossed the Zambesi river in 1835. In the interim period they fought prazo holders and other Ngoni groups led by Nxaba and Maseko, but also the Mutapa’s nyai forces who forced them into retreat.[xxv]

Kataruza (1843 – 1867)

Kataruza succeeded Dzeka,[xxvi] preventing Dzeka’s favourite son Muzongo from claiming the ruler’s title. David Livingstone met Kataruza and described him as “a chief of no great power…having about a hundred wives.” Despite this both Livingstone and the Portuguese paid a levy of cloth (sometimes 25% of their goods) to obtain passage through Chidima.

Mudenge described the Mutapa state in Chidima as being divided into many small chiefdoms, each ruled by a chief whom Kataruza called ‘son’ but each was to all intents and purposes an independent ruler. Most elephants in Chidima had been killed, so there was little ivory to trade and transit levies were the main source of trade goods. However even those were threatened when one of Kataruza’s sons seized a Tete traders’ goods and refused to return them. The Portuguese sent a military force that killed the son and his followers and for a time refused to pay any levy.

Kataruza died in 1867 and is remembered as being reliable and loyal by the Portuguese.

Kandeya II (1867 – 1876)

Kataruza died in 1867 and was succeeded by his son Kandeya II. The mhondoro Nyanhehwe (Nebedza) advised him to sever the relatively good relationship that had existed between Kataruza and the Portuguese and ally with Bonga of Massangano. The Portuguese reacted to the news by sending a force of 50 soldiers and numerous native auxiliaries and in their first encounter killed the mhondoro Nyanhehwe which caused Kandeya’s forces to flee. In the follow-up operations on the Kangure river, a tributary of the Monzovo river, Kandeya’s heir Canguencue (Kangwekwe) was also killed. The land from Kangure to Tete was confiscated by the Portuguese (thus shrinking the Mutapa state still further) and turned into prazos (Debwe and Boroma) with Kandeya left the remaining parts. He died or may have been expelled by Dzuda in 1876.

Pikirayi writes that Nxaba’s Ngoni and Mzilikazi’s amaNdebele mounted military missions as far as Zumbo on the Zambesi and were held off by the Mutapa forces.[xxvii] However as the threat of a takeover of Portuguese territory grew by British interests through the British South Africa Company, the Portuguese built up their military power in the Zambesi Valley. The prazo-holders and their Chikunda mercenary armies began the final assault on the remnants of the Mutapa state.[xxviii]

Dzuda (1876 – 1896)

Dzuda may have been one of Dzeka’s sons. For a time Dzuda’s forces bullied the Zumbo traders between Tete and Kachombo. By 1881 he was in dispute over land under Portuguese control. To strengthen his forces he allied with Nyamizinga of Massangano. In 1884 the prazo-holder of Debwe, Ignacio de Jesus Xavier (Karizimamba) and the Portuguese commander at Tete Firmino Luis Germano attacked Dzuda, the remaining lands of Chidima were annexed to the Portuguese and Dzuda fled into exile, living in a remote region between the Zambesi and Mazowe rivers east of the present-day Zimbabwe border. In 1887 Joachim Carlos Paiva d’Andrade visited him at his kraal near the Chissica river.

Between the start of Dzuda’s rule in 1876 and 1884 the Portuguese prazo-holders continued to encroach and divide up what remained of the Mutapa state south of the Zambesi river. Plans to occupy the northern half of the Zimbabwean plateau were only stopped by the arrival of the Pioneer Column at Fort Salisbury on 13 September 1890 and the subsequent movement of traders and miners into the upper Mazoe valley.

Chioka Dambamupute (1896 – 1902)

Mudenge writes that sometime in the 1890’s Dzuda was expelled by Chioka, a brother of Kandeya II. Chioko tried to unite an anti-Portuguese force with support from mhondoro Nyanhehwe including chiefs Boroma, Gosa and Changara and kept in touch with the resistance fighter Mapondera.

In 1897 they attacked the Portuguese prazo-holders at Debwe in the Tete area and the rebellion spread when he was joined by Makombe of Barwe and fighters from Massangano and effectively managed to eliminate the Portuguese from the entire frontier region.[xxix]

Many spirit-mediums supported the uprising which spread into the Mutoko, Mt Darwin and north Manzovo in present-day Zimbabwe as Chief Mapondera was made commander of his forces. For more than a decade Mapondera and his forces battled the Portuguese and Rhodesian forces whilst protecting the rural peasantry against exploitative company officials and abusive administrators and by 1901 the Tete district had been liberated from the Portuguese. [For an account of actions against Chief Mapondera see the article The story of a Trooper’s experiences in the Imperial Yeomanry and Rhodesia Field Force during the second Boer War 1899 – 1902 under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

This period is characterised by great violence

The Portuguese prazo-holders were forced to recruit a Chikunda mercenary army, less than 3% of the 20,000 force being Portuguese, to regain control of the Zambesi valley. Armed with modern rifles and artillery they outgunned and outnumbered the Barue and their allies, who were militarily weak and forced to resort to hit and run tactics.

However in 1902 Chioko was killed assisting the Barue in their fight with the Portuguese and with his death the Mutapa state came to an end.[xxx]

The spirit of rebellion continued in the Zambesi valley and in 1917 three separate forces campaigned to drive the Portuguese out of Zumbo, Tete and Sena. To identify the separate ethnic groups they wore red bark cloth around their foreheads and used secret passwords. From March 1917 they scored some remarkable triumphs with much of the territories, except for the towns, effectively occupied by the rebels.[xxxi]

However as in 1902, superior firepower and a mercenary army overwhelmed the rebels combined with a scorched-earth policy to drive the remaining rebels into mountain strongholds from where they carried out hit and run attacks, but by 1920 the few survivors were forced to flee into Zimbabwe.

Kamanika

Chioko’s heir, Kamanika was never able to put together the broad-based alliance against the Portuguese that his father managed. Kamanika was captured and imprisoned by the Portuguese. His ally, Makombe Hanga, the last Makombe (or king) of the Barue or Barwe in central Mozambique, fled to Southern Rhodesia and agreed not to take part in any future political activities.

Without political leadership in the Barue and Tete districts resistance to the Portuguese ceased and they came under the administration of the Companhia de Mocambique and the Companhia de Zambezia.

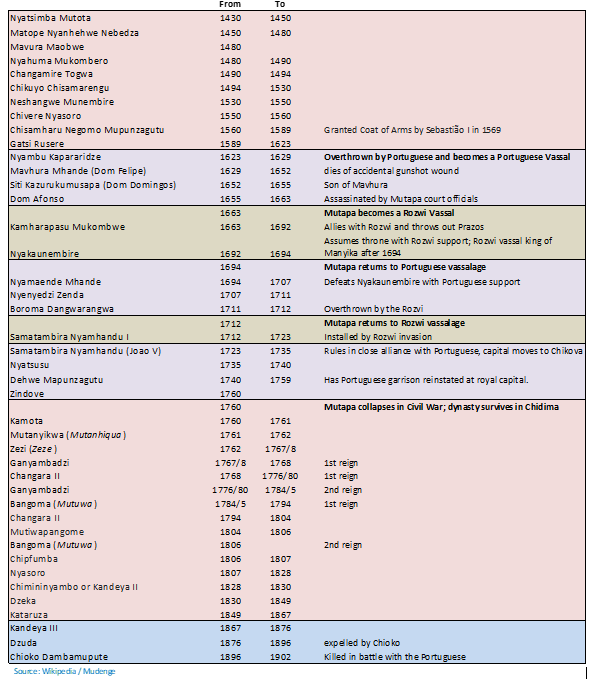

Rulers of the Mutapa State

References

D. P. Abraham. The early political history of the kingdom of Mwene Mutapa (850-1589). In Historians in Tropical Africa: proceedings of the Leverhulme Intercollegiate Conference,

September 1960, Stakes, E.(ed.), 61--92. Salisbury: University College of Rhodesia and Nyasaland

J. Mutero Chirenje. Portuguese Priests and Soldiers in Zimbabwe, 1560-1572: The Interplay between Evangelism and Trade. The International Journal of African Historical Studies

Vol. 6, No. 1 (1973) P36

A.F. Isaacman. The tradition of Resistance in Mozambique. Africa Today

Vol. 22, No. 3, Jul-Sep,1975), P37

M. Main and T.S. Huffman. Palaces of Stone: uncovering ancient southern African kingdoms. Penguin Random House South Africa, 2021

S.I. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House, 1988

Abigail Moffett and Shadreck Chirikure. December 2016. Exotica in Context: Reconfiguring Prestige, Power and Wealth in the Southern African Iron Age. Journal of Worl Prehistory 29(4):337-382

National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (www.nmmz.co.zw)

Innocent Pikirayi. The post Great Zimbabwe city: towns, palaces, villages and functional specialization in the Mutapa State, northern Zimbabwe, 1500-1900 AD

Innocent Pikirayi. The Zimbabwe Culture: Origins and Decline of Southern Zambezian States. Altamira Press, 2001

Gilbert Pwiti. Settlement and subsistence of prehistoric farming communities in the mid-Zambezi Valley, Northern Zimbabwe. South African Archaeological Bulletin 51: 3-6, 1996

Gilbert Pwiti. Continuity and Change: An archaeological study of farming communities in northern Zimbabwe AD 500-1700.

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and vanished civilisations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin, Cape Town 1971

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia. 1969.

Father Monclaro Account of the Journey made by Fathers of the Company of Jesus with Francisco Barreto in the conquest of Monomotapa in the year 1569 in G.M. Theal. History and Ethnography of Africa South of the Zambesi, from the Settlement of the Portuguese at Sofala in September 1505 to the Conquest of the Cape Colony by the British in September 1795 in Vol 3. Pages 202-253.

Notes

[i] Oliver R.A. and Fage J.D. A Short History of Africa. Harmondsworth, Penguin, 1964

[ii] The post Great Zimbabwe city: towns, palaces, villages and functional specialization in the Mutapa State, northern Zimbabwe, 1500-1900 AD

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Olfert Dapper in ‘Nether Ethiopia – the Empire of Monomotapa’ in John Ogilvy, ed., Africa (London 1670) P597

[v] Bourdillon, The Shona peoples: An ethnography of the contemporary Shona, with special reference to their religion, Gweru: Mambo Press, 1998

[vi] P. Virtanen, ‘Land of the ancestors: Semiotics, history and space in Chimanimani, Mozambique’, in Social and Cultural Geography, Volume 6, Number 3, 2005, p.365.

[vii] M.F.C. Bourdillon, The Shona peoples: An ethnography of the contemporary Shona, with special reference to their religion, Gweru: Mambo Press, 1998

[viii] Palaces of Stone, Uncovering ancient southern African kingdoms, P114

[ix] J.F. Holleman, ‘Some Shona tribes in Southern Rhodesia’, in E. Colson and M. Gluckman (eds.) Seven tribes in British Central Africa, London: Oxford University Press, 1951, p.364

[x] The Zimbabwe Culture, P179

[xi] Whitty. A Classification of Prehistoric Stone Buildings in Mashonaland, Southern Rhodesia.

The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol. 14, No. 54 (June 1959), pp. 57-71

[xii] T.N. Huffman. Expressive Space in the Zimbabwe Culture. Man New Series, Vol. 19, No. 4 (Dec 1984), pp. 593-612 by Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland

[xiii] Mudenge, P263

[xiv] Ibid, P266

[xv] Ibid, P270-1

[xvi] “Instructions to the Captain-Major D. Francisco De Almeida” 5 March 1505 Documentos, III, P201

[xvii] In 1684 the Rozvi conquered the Mutwira (Madziva) rulers in Maungwe and replaced them with

the Makoni dynasty

[xviii] In 1699 the Chikanga dynasty in Manyika was conquered and replaced by a Rozvi dynasty,

later known as Mutasa

[xix] Fr Monclaro, “Account of the Journey…etc”

[xx] Commercial deposits of silver have never been found

[xxi] I am not aware of the family relationship of Samutumbu Nyamhandu

[xxii] M. Newitt. A Short History of Mozambique, P36

[xxiii] The Zimbabwe Culture, P192

[xxiv] The Zimbabwe Culture, P193

[xxv] Ibid

[xxvi] Dzeka had succeeded Kandeya I sometime in the 1830’s i.e. during the Mfecane and the violence and chaos of the period had a further negative impact on the Mutapa state

[xxvii] The Zimbabwe Culture, P194

[xxviii] Ibid

[xxix] This began a tradition of Resistance in Mozambique,

[xxx] Mudenge states 1902, Wikipedia states Chioko was killed in 1917

[xxxi] Ibid