Dan Judson and the Africa Transcontinental Telegraph Co

In the article on the Mazowe Patrol, under Mashonaland Central, I have noted that Dan Judson, the Inspector of Telegraphs, was the real organiser behind the relief of the Alice Mine laager and their subsequent rescue during the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga. However, Inspector Randolph Nesbitt, then in the Mashonaland Mounted Police (MMP) before it amalgamated with the Matabeleland force to form the British South Africa Police, was given the Victoria Cross, awarded for gallantry to British armed forces in the presence of the enemy, as sub-Inspectors, Inspectors and Chief Inspectors in the MMP were considered commissioned officers and Nesbitt had the equivalent military rank of Captain.

Dan Judson although a Lieutenant in the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers, was considered to be part of the local militia and could not be considered for the Victoria Cross. The George Cross which recognises civilian gallantry; "acts of the greatest heroism or of the most conspicuous courage in circumstnces of extreme danger" was only awarded from 24 September 1940.

Judge Vintcent, the Administrator, tried his best to win recognition for Judson’s role and wrote: “I desire to bring to the notice of the Board the very excellent services Mr Dan Judson rendered during our troubles in the early period of the Rebellion. I must confess that I am surprised to see the absence of Judson’s name amongst the persons specifically mentioned in Sir Frederick Carrington’s report to the War Office.” He outlined many of the duties Judson had performed and which are detailed below in the text and ended: “I trust that the Board will be able to bring to the notice of the proper authorities the meritorious and useful services rendered by Judson.” But Lord Carrington, who arrived in Bulawayo on 3 June 1896, put Nesbitt forward as the only military candidate in this episode. The mistake, in my opinion, was in giving one man the Victoria Cross instead of the BSA Company striking a medal for all the men and three women that took part in the Mazoe Patrol.

Early life

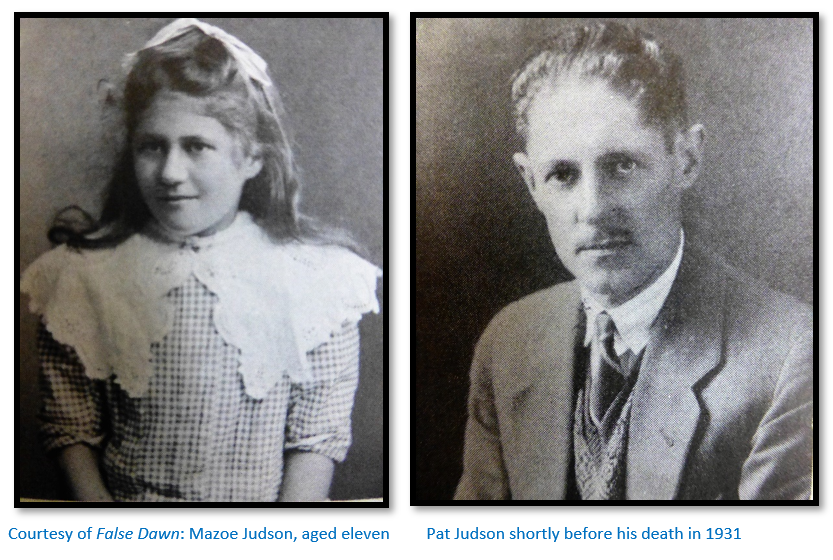

Dan Judson was born in Melrose, South Australia on 9 August 1864; but when he was ten years old the family came to live in Cape Town. Soon afterwards his father left his mother, who had to struggle to bring up the family of three sons and one daughter on her own; survivors of the ten children born to her. For this reason, Dan left school at fifteen years and joined the Post Office continuing his studies at night school where he learned Pitman’s shorthand. Although he could not read music and played entirely by ear, he joined the Cape Town Drum and Fife Band and also a local orchestra as a violinist.

1882 - a year’s adventure at the Barberton goldfields

In 1882 he resigned from the Post Office after hearing of the gold rush at Barberton in the Eastern Transvaal, now Mpumalanga, but for all his effort he only managed to save a gold nugget which was made into a brooch for Maynie, his future wife, on her seventeenth birthday. After the year’s absence, he was taken back by the Post Office because he had been such a quick and accurate telegraph operator.

1885 – joins the Warren Expedition to Bechuanaland (now Botswana)

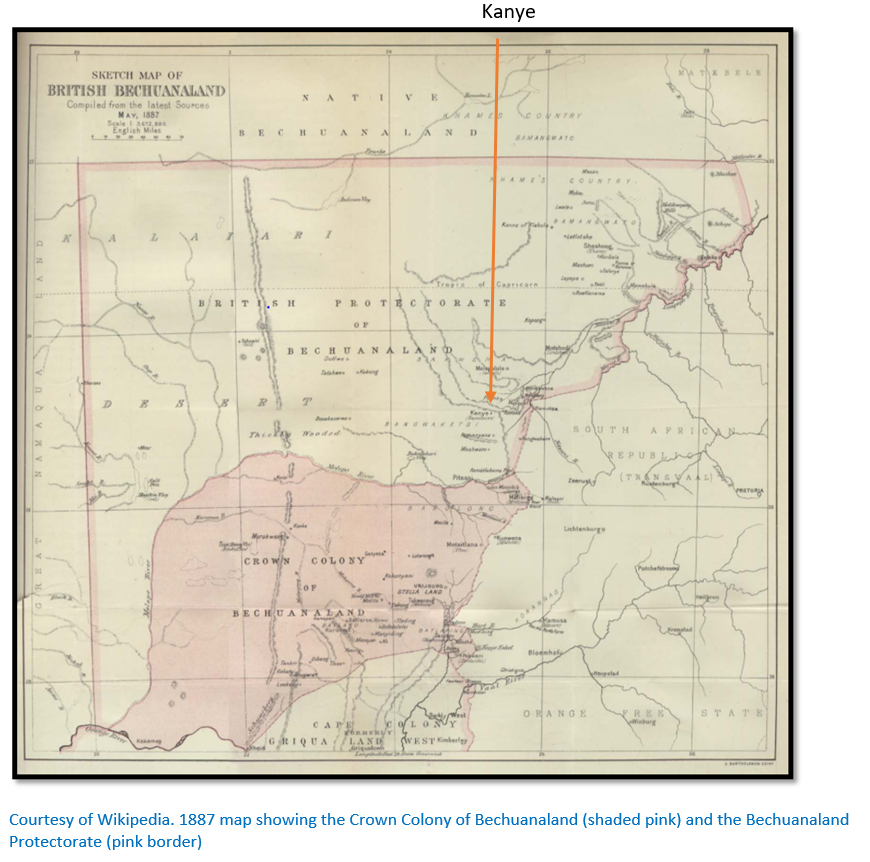

In early 1884, not yet twenty years old, Dan decided to join the Warren Expedition into Bechuanaland. Major-General Charles Warren headed up a military expedition of four thousand Imperial and local troops to claim British sovereignty because of threatened territorial incursions from the Transvaal, Germany and the Boer freebooter states of Stellaland and Goshen that were stealing cattle and land from the local Tswana tribes. Despite Paul Kruger, President of the South African Republic, promising at Modder River to maintain order in Bechuanaland, Warren marched into Bechuanaland where he dissolved the republics of Stellaland and Goshen and proclaimed Bechuanaland a British Protectorate, thus easing Rhodes’ fear that the route to Zambesia, now Zimbabwe and Zambia, would be blocked.

The Telegraph Office blocked his application to join Carrington’s Horse as a bugler, so he applied to the 4th Pioneers and this application was also blocked. To satisfy his ambitions, he was offered a new position at a station on the Orange River near Hopetown. Hopetown had been a quiet farming area until the Eureka and the Star of Africa, both exceptional diamonds, were discovered between 1867 and 1869. When he arrived on 8 January 1885 he wrote in his diary: “I shudder at the thought that I have to spend six months in such a beastly hole.” By 31 March he wrote: “I am bored almost to death with the life I am leading at this place and I think I shall join the military telegraphs.”

Soon after he wrote to Captain Joliffe of the military telegraphs saying he had passed the medical, been in charge of five different telegraph offices, could send thirty-five words a minute and receive thirty words a minute (by sound) After much to-ing and fro-ing he was told he was told he should report to Barkley West as a telegraphist. On 10 May 1885 he arrived at Barkly West: “Wouldn’t say I enjoyed the journey, rather too dusty and a little too much sameness, with no scenery to interest a fellow...I was taken on the strength and am to do duty in the military office here until Captain Joliffe leaves for the front, when I shall go forward with him.”

A few days later he arrived at Kanye in Bechuanaland.

Bechuanaland was annexed by Britain on 31 March 1885 without a shot being fired and Dan arrived as the Bechuanaland Field Force was being gradually disbanded. He was offered a commission in the Royal Engineers but turned it down without the necessary private income to be an officer in the British Army: he was permitted to re-join the Telegraph Office because he was such a valuable telegraphist but lost some years of seniority.

Dan Judson as telegraphist at Blignault’s Pont in the old Transvaal Republic

The first conferences between Loch and President Kruger, President of the South African Republic, also attended by Rhodes at Blignault’s Pont was prompted by Louis Adendorf, who claimed he had obtained a permit from Chief Chibi, who exercised control of territory south of the present-day Masvingo (then Victoria - the town only became Fort Victoria in 1927) and Adendorf wanted to establish a Boer Republic in the country. On 24 June 1891 Adendorf and a group of armed Afrikaners had tried to cross the Limpopo River, but were stopped by Jameson and the British South Africa Company police who said they could only do so if they accepted the authority of the British South Africa Company.

Dan was in the middle of transmitting a telegraph for the Cape Times reporter when suddenly the hut shook and moved a few inches. He rushed outside to find his horse, which he had tied to a hut pole, pulling the cord so much it threatened to strangle itself: “as soon as he was sufficiently recovered to stand-up, I adjusted the rope with a double knot and knee-haltered him.” With the conference continuing, he was hard at it all day: “nothing to eat all day, Telegraph Inspector and Police Inspector both promised faithfully to send something by the orderlies, but of course thought no more about it.”

“At 5pm the Inspector turns up with a batch of messages, amounting in all to over two thousand words and asks me to get them off sharp as he wanted to break office and reach Warrenton, north of Barkly West, that night.” It was nearly midnight when Dan and the Inspector reached Fouché’s Pont in drizzling rain and found the pont was on the other side of the river, moored for the night. They shouted until they were hoarse, but to no effect until Dan found an old dinghy, half full of water, and rowed across the river which was running high and managed to persuade Fouché to fetch their horses. Landing was the worst part. “The horses could get no foothold and repeatedly fell to their knees and haunches, at one time being within an ace of toppling themselves and the cart into the river” but they finally managed to reach Warrenton at 2am.

Dan Judson as telegraphist on the High Commissioner’s tour of Bechuanaland

Dan was special telegraphist to Sir Henry Loch and Lord Elphinstone, two influential members of the Cape Parliament, Venter and de Waal and Rhodes on their journey through Bechuanaland to visit Lobengula, the amaNdebele King at Bulawayo. Near Gaberones (now Gaborone) a gathering of chiefs was addressed and Dan had to tap the wire two kilometres distant and send a message with a battery box as seat and two remaining boxes as a table. However, Loch was warned repeatedly that Lobengula’s ‘young bloods’ were restless and looking for trouble and the party did not get to see Lobengula (for more detail on this see the article on Rhodes’ first journey into Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

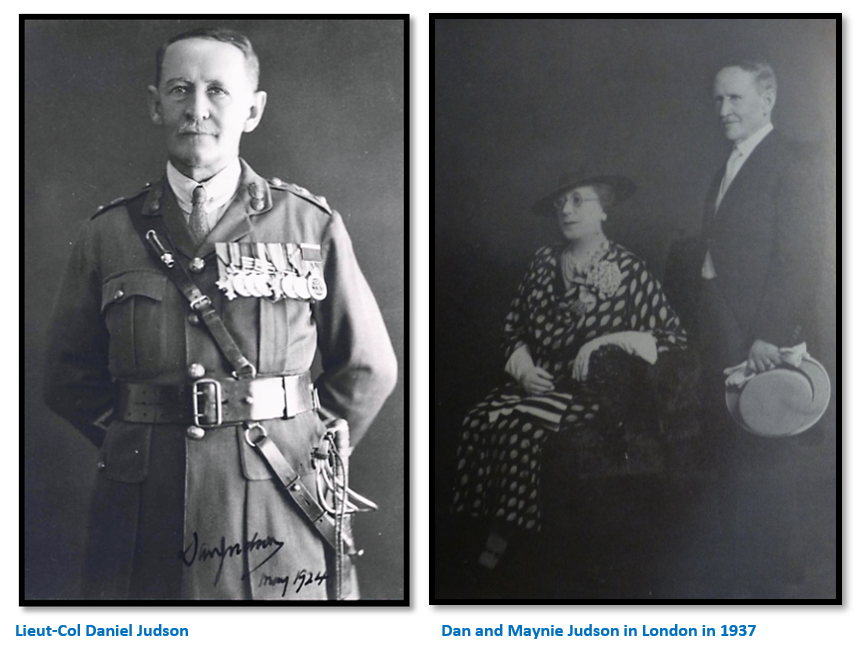

Marriage to Maynie

Early in 1892 Dan was transferred to Colesburg in the Cape Colony and in October married his childhood sweetheart, Wilhelmina (Maynie) Freestone Eckhard when she turned seventeen. On their honeymoon they visited the big Exhibition at Kimberley, where they never forgot the music of the Blue Viennese Band from Germany. Dan was Postmaster at Colesburg, a quiet Dutch village for three months before being transferred to Kimberley.

Transfer to Rhodesia

In 1893 Rhodes was looking for a first-class man to reconstruct, reorganise and take charge in Mashonaland and Sir James Sivewright, the General Manager of the Cape Telegraph, recommended Dan, now twenty-nine years old. One of Dan’s first acts when arriving in Salisbury was to join the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers where he was gazetted a Lieutenant. The British South Africa Company had been maintaining a police force of six hundred and fifty men in October 1891 at a cost of £150,000 per annum; by December Dr Jameson, the Administrator had reduced the number to one hundred and fifty men to be replaced by the volunteers of the Rhodesia Horse in Bulawayo and Salisbury.

The development of the Railway and Telegraph systems

The British South Africa Company (BSAC) was a commercial speculation founded on the hope that the Mashonaland goldfields would provide the seed capital for commercial development in central Africa, initially south of the Zambesi River, but eventually extending into modern day Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Development of the railway and telegraph systems were an integral part of that objective and only when the British Government were satisfied that the BSAC had sufficient capital was the Royal Charter granted on 29 October 1889.

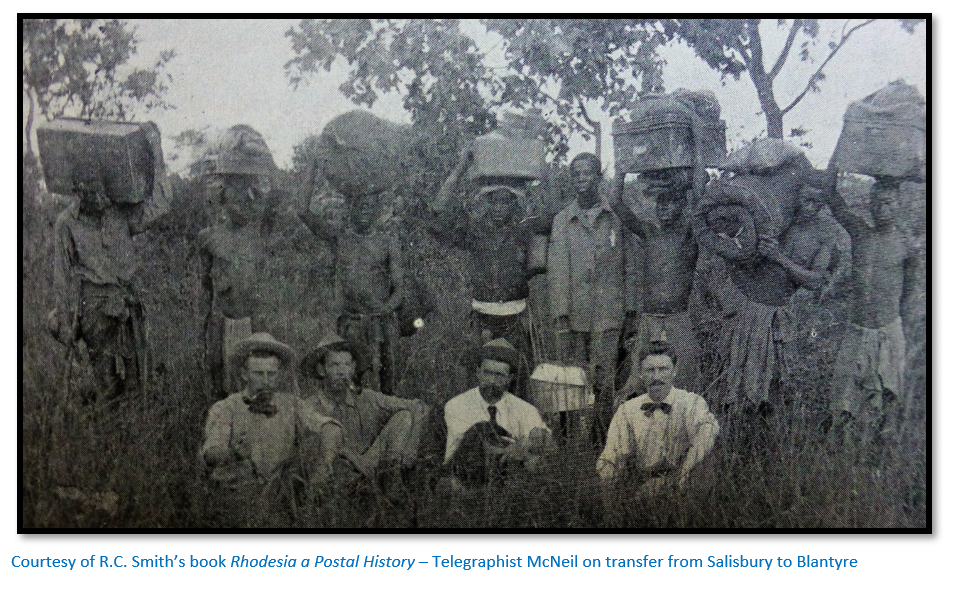

The telegraph system was extended northwards from Mafeking simultaneously with the railway under the day-to-day direction of Lt-Col William Standford, also of the Cape Telegraph, and initially the telegraphists were all lent from the Cape Telegraph…hence Dan Judson’s involvement. Mafeking, the terminal station in British Bechuanaland, was operated by British officials and from Ramoutsa to Macloutsie the telegraph offices were run by members of the Bechuanaland Border Police (BPP) These telegraphists were paid a monthly allowance of four pounds by the BSAC.

Telegraph costs between BSAC offices were 6d. per word prior to March 1892; thereafter 3d. per word with a minimum of 2s 6d. An additional charge was levied for other destinations, so telegrams to the Cape, Natal, Orange Free State and Transvaal incurred an additional charge of 1s. for the first ten words and 6d. per word thereafter. Press messages were generally at a quarter of the normal rate. In return for £1,000 per annum, the British Government had use of the telegraph line between the BSAC offices in Matabeleland and Mashonaland.

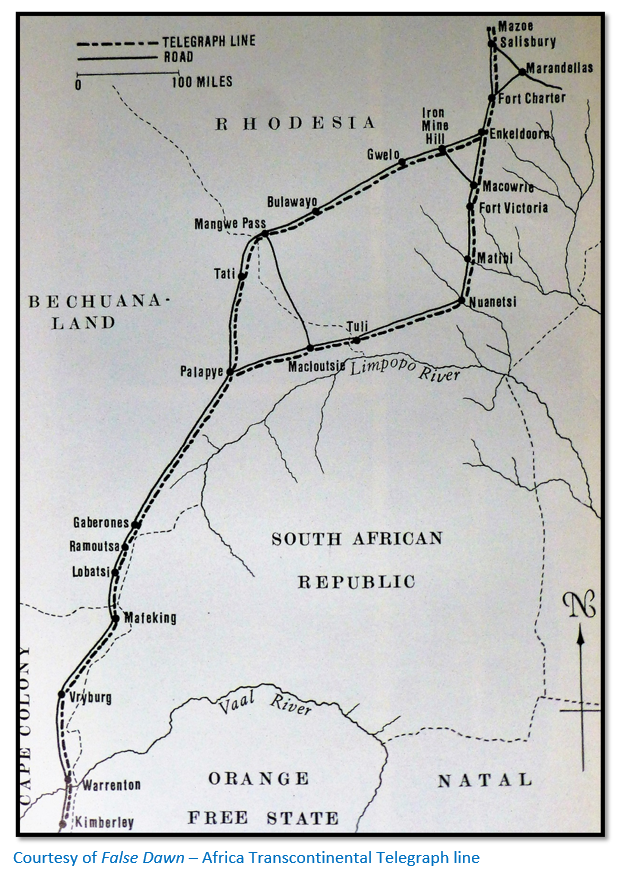

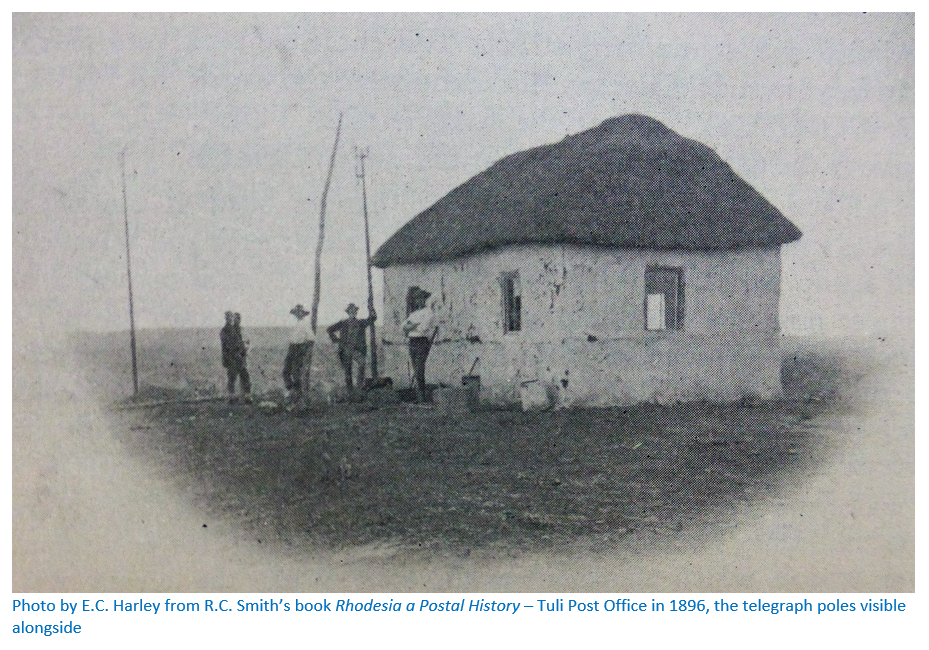

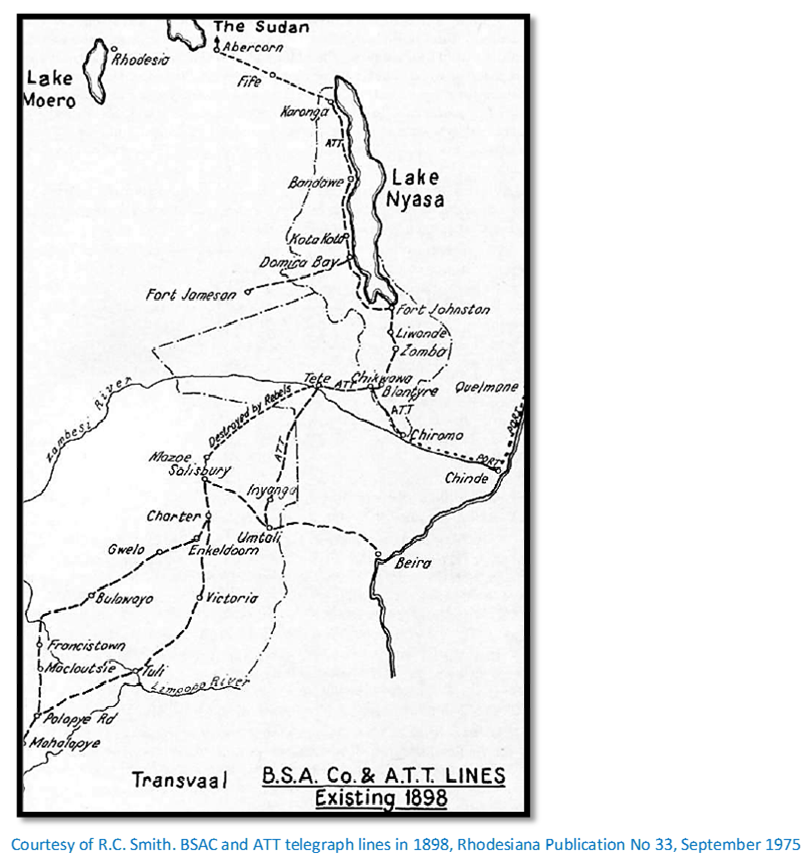

The first Telegraph line

The telegraph line to Rhodesia was started in 1890 from Mafeking to Palapye (three hundred and ninety kilometres) and completed by October 1890; Tuli telegraph office opened in 28 May 1891; Victoria by year-end and Salisbury was connected on 16 February 1892. Soon afterwards it was extended to Mazoe where a lot of prospecting had taken place and where the events outlined in the Mazoe Patrol article took place.

The telegraph line followed approximately the route taken by the Pioneer Column and passed through Ramoutsa (now Ramotswa) Gaberones (now Gaborone) Palla, Mochudi’s, Palapye or Khama’s, Macloutsie (headquarters of the Bechuanaland Border Police or BBP) Tuli, Matibi’s, Nuanetsi, Victoria (now Masvingo) Fort Charter and Salisbury. Telegraphists were stationed at each of the above; the Cape Colony transmitting offices were at Mafeking and Kimberley.

Iron poles were used as far as Matibi’s kraal on the Lundi (now Runde) River: then wooden poles carried the line, made of No 6 gauge iron wire, to Salisbury. However wood poles, although cheaper and quicker to erect, were susceptible to elephant and buffalo damage and destruction from veldt fires and white ants. in the early days maintenance was carried out by the telegraphists themselves with their task often complicated by swollen rivers which were difficult and dangerous to cross.

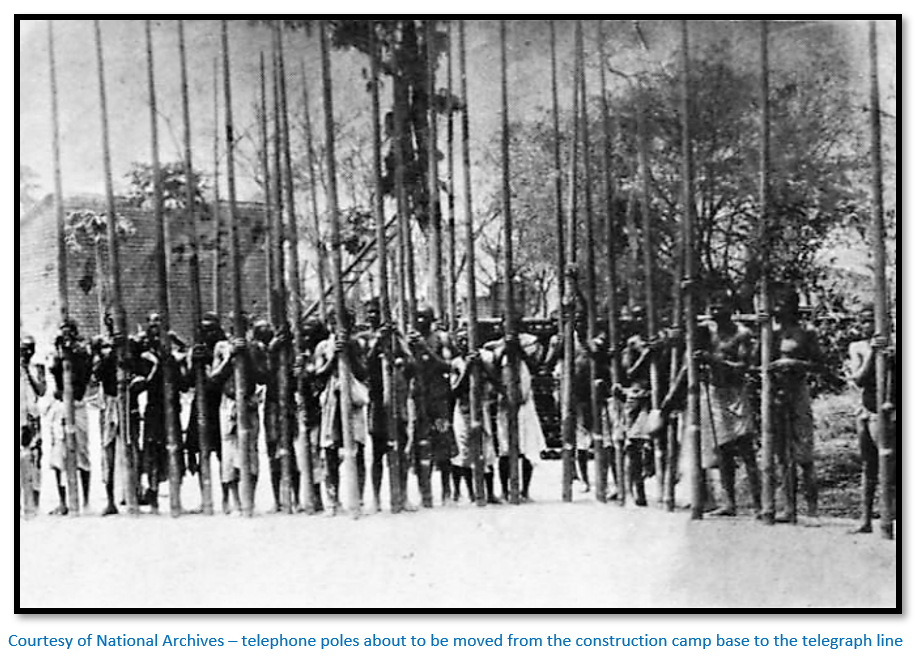

The telegraph line in Bechuanaland (now Botswana) followed roughly the path of the present-day railway line before it branched off at Palapye to Macloutsie and then on to Tuli. Construction of the line progressed at about five kilometres a day and was carried out by two hundred and fifty men, mostly supplied by Chief Khama. Once they entered Mashonaland however, they insisted on being armed; most carried old muskets that were generally loaded and at full cock, slung over their shoulders together with picks, spade and axes.

In May 1893 the telegraph line at Nuanetsi River was cut and several hundred metres of copper wire stolen; the wire was useful in making bangles and snares for trapping game. The theft was traced back to tribesmen under Mashona Chief Gomalla and the BSAP were sent to fine the men. Chief Gomalla handed over cattle, which he said were his, but in fact had been left in his safe-keeping by King Lobengula. He then sent word to Lobengula saying that white men had stolen the cattle. This started a train of events which contributed to the onset of the 1893 Matabele War.

Robert Cherer Smith says the original Selous road used by the Pioneer Column from Tuli to Victoria in July to September 1890 was virtually abandoned and by 1895 there was no accommodation along its three hundred and fifty kilometre length. In July 1896 linesman MacGregor was sent out to make repairs and nothing was heard from him for twenty-eight days. A BSAP patrol sent out to search found him walking towards Tuli; his horse having been mauled by lions.

All communication in the early days was via Victoria, but in 1893 during the Matabele War a light field telegraph line was constructed from Palapye to Tati and then via Mangwe to the Bulawayo office which was opened on 9 July 1894 and this quickly became the favoured route.

As soon as the line reached Bulawayo an extension was begun to Charter via Gwelo to enable direct links between Bulawayo and Salisbury and this opened in January 1895; Dan Judson’s part in this project is detailed below. After initially deciding to close down the Tuli to Victoria telegraph link, this decision was reversed and proved correct as during the 1896 Rebellion or First Umvukela, the Bulawayo to Salisbury link was often cut and the line via Tuli was the only way the two centres could communicate.

The telegraph line was cut during the 1896 -7 Mashona Uprising or First Chimurenga between Salisbury and Umtali under the initiative of Chief Mangwende and his son Mchemwa. [see the articles on the graves at Old Marandellas (Ruzawi Cemetery) and the Bernard Mizeki Shrine under Mashonaland East on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] A patrol under Capt. Hon. C.J. White made repairs before meeting up with Lt-Col. Alderson and his Mounted Infantry.

Not shown on the telegraph map above is the Salisbury – Chimoio telegraph line operated by the Beira and Mashonaland Railway Company and the Beira Railway Company connection from Chimoio to Beira which opened on 18 September 1894.

After the troubles of 1896 – 7, telegraph lines were extended greatly within the next ten years. Salisbury connected with Bulawayo, Umtali (now Mutare) Enkeldoorn (now Chivhu) Macloutsie in Botswana (via Victoria and Tuli) Mazoe (now Mazowe) and Ayrshire. Bulawayo connected with Wankie (now Hwange) Ramathlabana in Botswana and Gwanda. Gwelo (now Gweru) connected with Enkeldoorn, Selukwe (now Shurugwi) and Sebakwe. Umtali connected with Melsetter (now Chimanimani) Tete in Mocambique, Blantyre in Malawi, Zomba, Karonga and Abercorn. Palapye connected with Macloutsie.

By agreement between the Cape Colony, The British Bechuanaland Administration and the BSAC all operations from 1 August in Rhodesia came under BSAC control, as did lines and offices in the Bechuanaland Protectorate. In the early days telegraph revenue far exceeded postal revenue as mail deliveries could be unreliable and take weeks and months to reach their destination. From 1 January 1903 the telegraph rate was reduced from 2s. to 1s. per twelve words for internal telegrams and from 2s. 6d. for ten words to 2s. for twelve words for destinations in South Africa. Official telegrams on Government service were transmitted at half the normal rate, but telegrams for the Imperial and South African Government, BSAC, the Railway Companies, Mail Coach (Zeederberg) and railway contractors (Pauling and Company) were free of charge.

Macloutsie became the most important telegraph post where traffic from Bulawayo via Mangwe and Salisbury via Tuli converged. There were a staff of six Morse operators stationed at Macloutsie and they were all kept busy.

By 1902 nearly nine thousand five hundred kilometres of telegraph line had been constructed by the BSAC.

Dan Judson appointment as Inspector of Telegraphs in October 1893

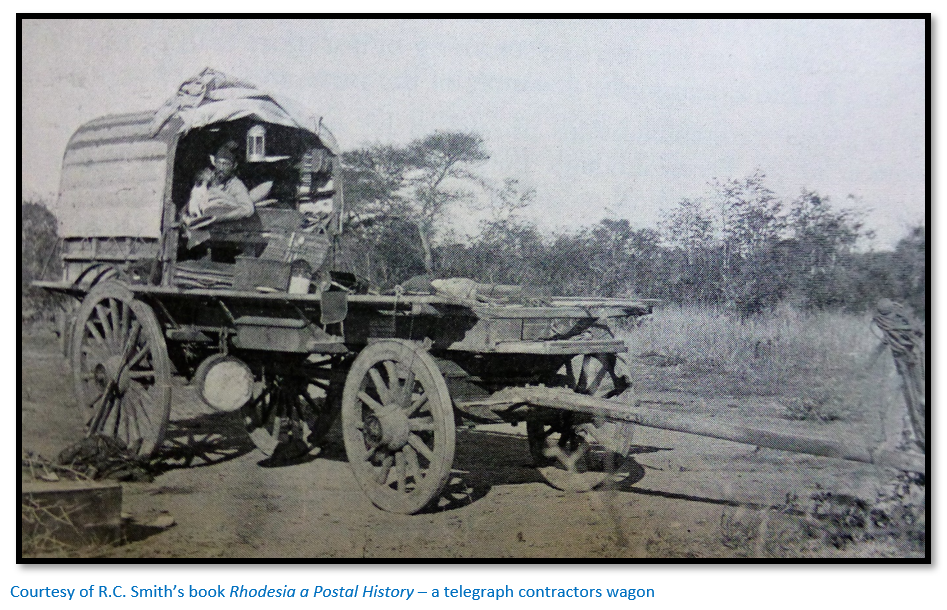

At the time of Dan’s appointment, AHF Duncan was Surveyor-General with responsibility for postal affairs but had little time to travel and inspect the telegraph offices and so Dan was appointed to reconstruct, reorganize and take charge of telegraphs in Mashonaland. His kit was carried in a two-wheeled Scotch cart and he rode on horseback so that when the telegraph line deviated from the track, he could easily follow it. He slept in a patrol tent and in the rainy season was often wet. At the Tati River, a subsidiary of the Shashe River which flows past Tuli, he had a lucky escape when after waiting for two days for the river to subside, he stripped off and swam across and was only saved by the men on the other side forming a human chain and pulling him into the riverbank.

The mystery of Dr Jameson’s mail at Charter

On one of his first trips outside Salisbury Dan was asked by Dr Jameson to investigate why his copy of the weekly Times often arrived out of sequence. The Fort Charter Post Office was a dhaka and thatch hut, completely bare of furniture. The postal agent was Sgt Galt and when the post cart turned up everyone congregated at the hut eagerly hoping for letters.

Sgt Galt tipped the mail bag on the floor and squatted whilst he sorted and Dan noticed that occasional papers were put aside. When everyone had their mail, Dan noticed that Galt kept those put aside and asked him what he was going to do with them. Galt said that in one of the huts was a young fellow who had been on a wagon when the wheel had hit a tree stump and he’d been thrown out and runover by the wagon.

He had been lying injured in a hut for months quite alone except when brought meals. During the days he managed to sleep, but the nights were interminable and he said he would have gone mad if not for a little field-mouse which he had managed to tame with water and bread crusts.

The post cart arrived at Charter every Tuesday at 7am and left at 4pm for Salisbury and so to relieve the poor fellow’s boredom Galt carefully unwrapped Dr Jameson’s newspapers, including the Illustrated London News, the Graphic and the Times and gave them to the invalid warning him to clean his hands and leave no prints! Before the post cart left, the newspapers were slipped back into their wrappers and returned to the mailbag for their onward journey. This routine had gone on for four months and the Times was sometimes delayed because it took longer to read.

Dan saw the humour in the situation but warned Galt of Dr Jameson’s suspicions and subsequent papers all arrived on time!

Collecting Maynie Judson from Beira

When the 1893 / 94 rainy season was over, Dan sent for Maynie in Cape Town and told her to catch a steamer to Beira where he would meet her. He took the coach from Salisbury to Old Umtali (now the Methodist Mission – see the article under Matabeleland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) where he bought a donkey cart, four donkeys, harness for £26 10 shillings. The cart was strongly made of deal wood with two rows of seats and stout wheels but had no brakes or any covering.

He prepared for an early start, but it was the Whitsun weekend and the locals at Old Umtali were having a gymkhana meeting on the holiday and insisted, despite Dan’s protests, that he officiate as the starter. However, knowing that they would probably hide his donkeys and cart if he protested too much, he agreed to be at the start at 9am, although he had no intention of keeping his word. At dawn he crept away and once away got up speed to be well away before they learnt he had gone!

At Chimoio, one hundred and twelve kilometres away. he left the driver and cart and walked along native footpaths through the Amatongas Forest; classic tropical forest made up of huge trees festooned with creepers and complete with swamps, malaria, tsetse-fly and wild animals. Unexpectedly he came across a camp laid out in a large clearing and in a mess-tent found food and drink, so he helped himself and left a note to his unknown host. Years later he learnt the camp belonged to Jesser Coope [Coope appears in the articles on Hubert Hervey and Battle of Tshingengoma or Sikombo’s stronghold under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] who was road-making and was not at all pleased with Dan helping himself!

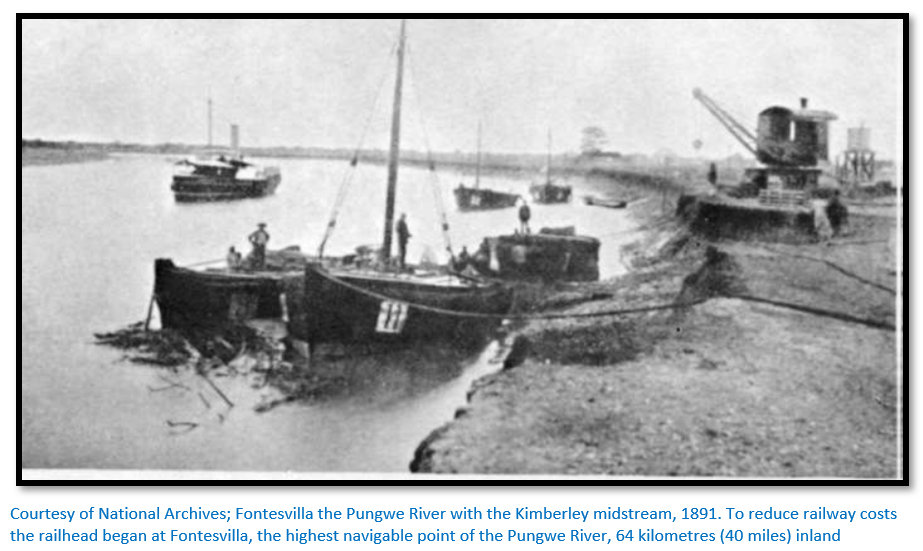

His feet soon blistered, but eventually he struck the line of rail and reached a construction camp where he had to wait two days before managing to get a lift on the narrow-gauge construction train down to Fontesvilla. When he reached Fontesvilla, he found he had just missed the paddle-steamer Agnes which would only return on the rising tide the next day. His hut, an old store, was crawling with huge rats that ate the candle stuck into a bottle by his bed, so he got up, dressed and walked about until dawn. He was worried about Maynie, but as they chugged down the Pungwe River at his request the Captain shouted: “is Mrs Judson on board?” to be told: “No, she is waiting at Beira.”

Maynie had a fun trip along the coast to Beira as she could sing and play the piano and was always in demand in the saloon after dinner. Also on the ship were Mr and Mrs Norton, their child and governess Miss Fairweather who were also travelling to Salisbury [they were all killed on 17 June 1896 along with Harry Gravenor at the start of the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga – Norton was named after them]

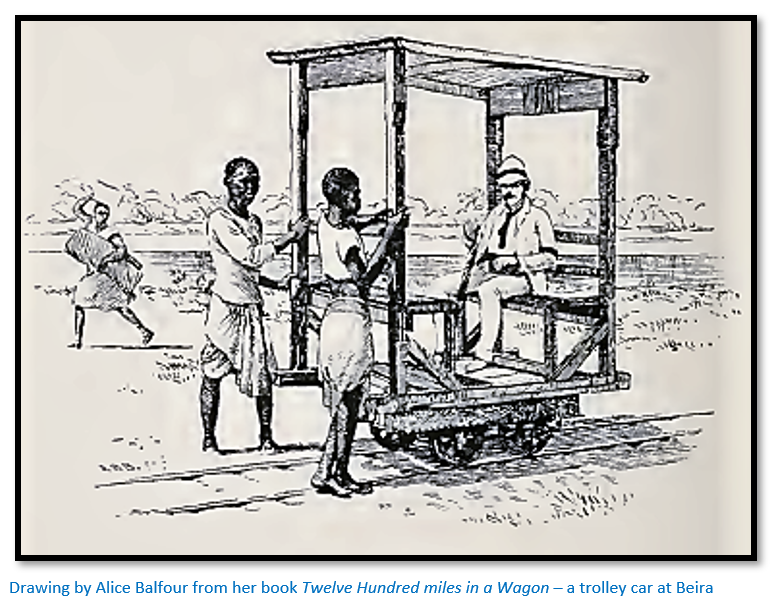

Maynie describes her destination: “Beira in May 1894 seemed to me one long street with buildings of all shapes and sizes on either side and the street a river of sand about a foot deep. You could not possibly walk. Down the middle ran a narrow trolley-line on boards and most of the inhabitants had their own trolley with two natives to push. When it was not wanted, the trolley was lifted off the rails.”

The return journey by paddle-boat and steam locomotive

As soon as Dan arrived at Beira, Maynie embarked and they returned up the Pungwe River as there was no landing-stage at the time and the Agnes ran the risk of being stranded on a sandbank as the tide retreated. At Fontesvilla their quarters were improved over those Dan had been given the previous night but was still crude: “Everything made of bamboo; chairs, tables, beds, walls, roof, the latter covered with palm leaves – airy, clean, but most uncomfortable. After sunset, a thick mist rose from the ground…it was very dark, musty and really horrible.”

They caught the train; the wood-fired locomotive was only just able to drag a few goods wagons along the 2 ft 6 inch gauge line with one of the wagons equipped with an iron garden seat for the privileged and whisky cases for everyone else. They were kept busy all the time looking for sparks which constantly flew from the locomotive and threatened to set their clothes on fire. The journey from Fontesvilla to the one hundred fifty six kilometre peg at the railhead (ninety-seven miles) took the whole day as the locomotive derailed twice and needed to be hauled back onto the track.

At one point a pride of lions refused to move off the track until the driver released a cloud of steam and then they moved slowly off into the grass. Often steeper gradients brought the locomotive to a halt; half the load would be taken off the goods wagons and left beside the track and the other half was moved along the track until the train reached a level stretch. Then that load would be removed and the locomotive reversed back to collect what had been left behind.

Passengers carried their own food and the train stopped at each construction camp where they were the object of great attention by the construction workers. Alerted by telegraph if there were women aboard the train, the young engineers would clean up and wear jackets to welcome the train. At one stop, the construction engineers prepared a tea complete with a cake! When the cake was cut, they discovered the cook had forgotten to add sugar which was added onto each piece!

Journey by cart to Old Umtali

At the railhead Dan was in luck…a Trans-Continent wagon was leaving with telegraph poles for the Umtali – Salisbury line and Captain Roach, the Manager, [Commander of C Troop of the Pioneer Column] was glad to come to help. Maynie recalled: “The three of us had to make ourselves as comfortable as we could in this half-tented wagon, sitting on iron poles. We packed as much grass as we could to make the floor level, but it was hard going and the dust and heat were unbearable. We were one whole day and night on that wagon.”

At Chimoio Dan’s donkey cart was waiting. The Portuguese commandant invited them to breakfast with his wife, an elegant woman in a pale grey gown with a tiny grey monkey on her shoulder! Tea was served in a bamboo summerhouse and consisted of porridge, eggs, black pudding, olives, blancmange, bottled fruit and preserves and wine!

The donkey cart only just managed to have space for Dan and the driver, Maynie and Ruby Wentworth who was going up to Salisbury to marry Boscowan-Wright, the Crown Prosecutor and a friend of Dan’s. The only luggage that could be carried by the women was a change of underclothes, washed wherever they could, a spare dress and pair of shoes, although Ruby also brought along her wedding dress in a band-box. The remainder of their baggage came behind by ox-wagon.

The grass either side of the track was nearly three metres high (twelve feet) and as the country was infested by lions, they planned to stay at wayside stores that were not far apart and where they were greeted warmly by the storekeepers. “They would never allow us to pay for anything…they said it was an event and an honour to entertain white women…Once when we were all seated enjoying a good meal, I noticed one of the men glance at his partner in a worried way. The latter got up hurriedly and went into the kitchen. In a few moments we heard the tearing of linen and soon afterwards the native boy came in and laid a folded piece of unbleached calico at each plate. They had forgotten the table napkins!”

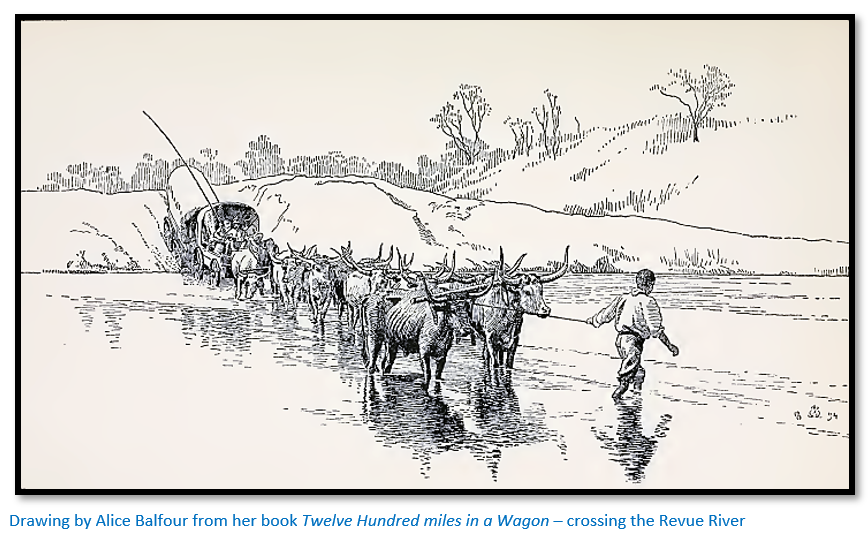

At the Revue River Dan slept on the floor of the hut between the two women as the flimsy door of their hut was only fastened with a piece of string and they could hear the roaring of lions. The primitive beds were made by driving four forked poles into the ground and laying on them two long poles over which sacking was stretched. Although the storekeeper gave them a dozen blankets from the store the women were frozen and with teeth chattering and bone cold, quietly made their beds on the floor in company with Dan.

The next part of the journey was all hills and valleys, rivers and marshes so Dan did some work on the cart before leaving. The storekeeper warned them of crocodiles before they left; Maynie wrote: “The banks were not high, but sharp. We went in with a tremendous bump and to our horror heard the boards at our feet cracking. We quickly grabbed our possessions from the floor and piled them on our laps. Dan jumped into the river and told the driver to go on carefully, but another ‘crack’ and two of the floor boards gave way, fortunately not under the seats. We were told to take off our shoes and stockings, pile everything on the seats and lower ourselves through the cart into the river and walk out like that. Ruby carried her band-box on her head. While the cart was dragged up the opposite bank, we crawled on to the front seat.” They then had to wade back to the far bank, the women “holding their skirts and petticoats above their knees and they made as much noise as they could, splashing and shouting to frighten away crocodiles.” After repairing the cart, next day they made a safe passage across the Revue River.

At the top of Christmas Pass on their way down to Old Umtali, Dan stopped to take a photo of the view and the driver turned the cart upside down with the wheels still turning and all their baggage scattered and the two women pitched onto the ground, both fortunately unhurt. A tot of brandy revived them both and they decided to spend the night at the small wayside store on the future site of the Christmas Pass Hotel. The storekeeper, a young man, was suffering from malaria, went to bed; the only food available was a tin of salmon and dry biscuits.

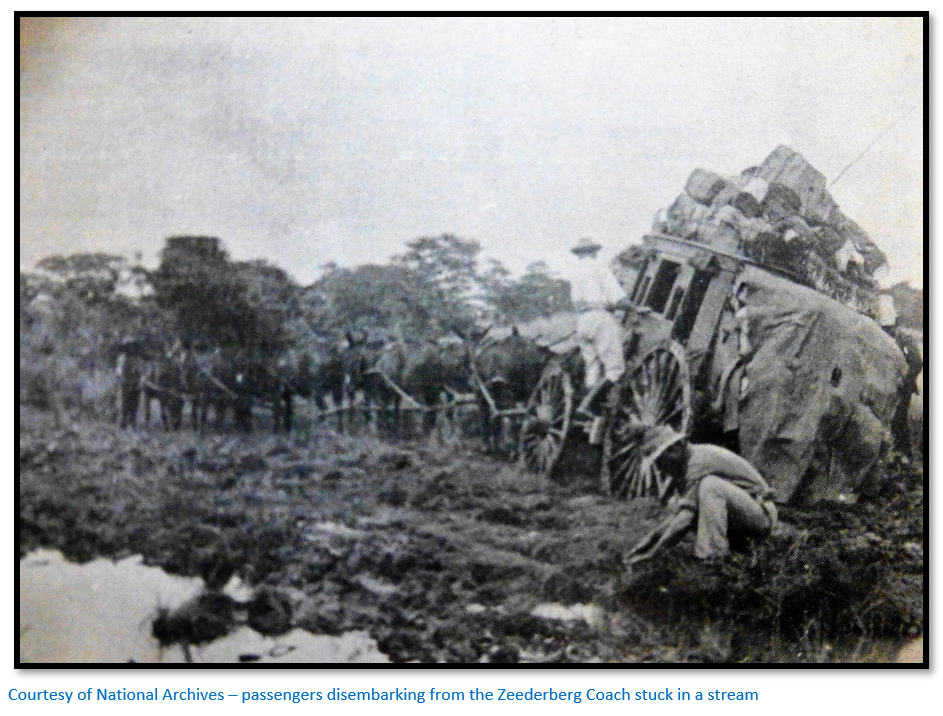

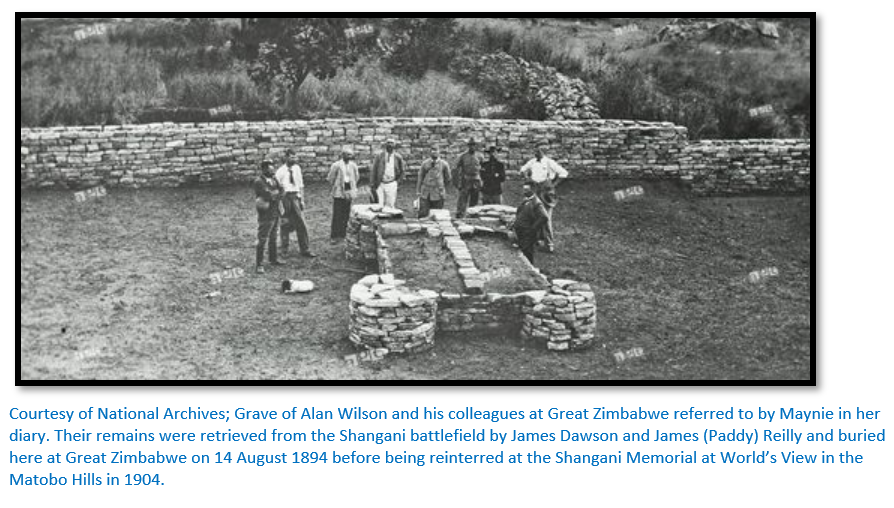

Next morning they left and, on their way, told other storekeepers of the young man’s illness before reaching Old Umtali and selling the donkeys and cart for £30 and catching the Zeederberg coach back to Salisbury. The coach was pulled by mules but loaded to capacity and needed to be completely unloaded to escape when it stuck in a patch of black vlei. The journey took all day and night; Maynie and Stuart Meikle both suffering from an attack of malaria and the coach arrived at Salisbury at 8am. Maynie was in bed for a fortnight nursed by Mrs Greenfield [widow of Captain Harry Greenfield killed at the Shangani River with Major Alan Wilson and his Patrol on 4 December 1893]

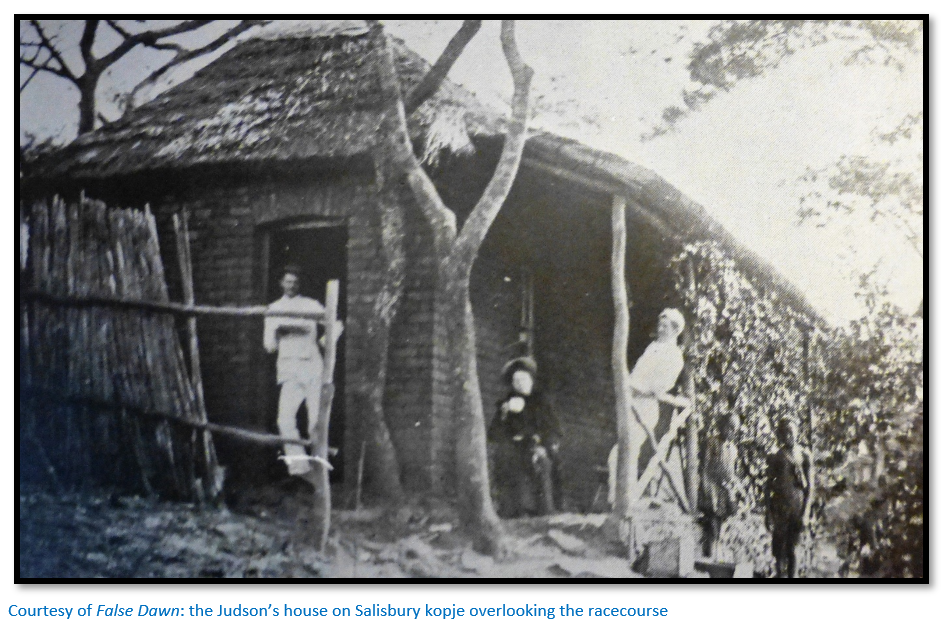

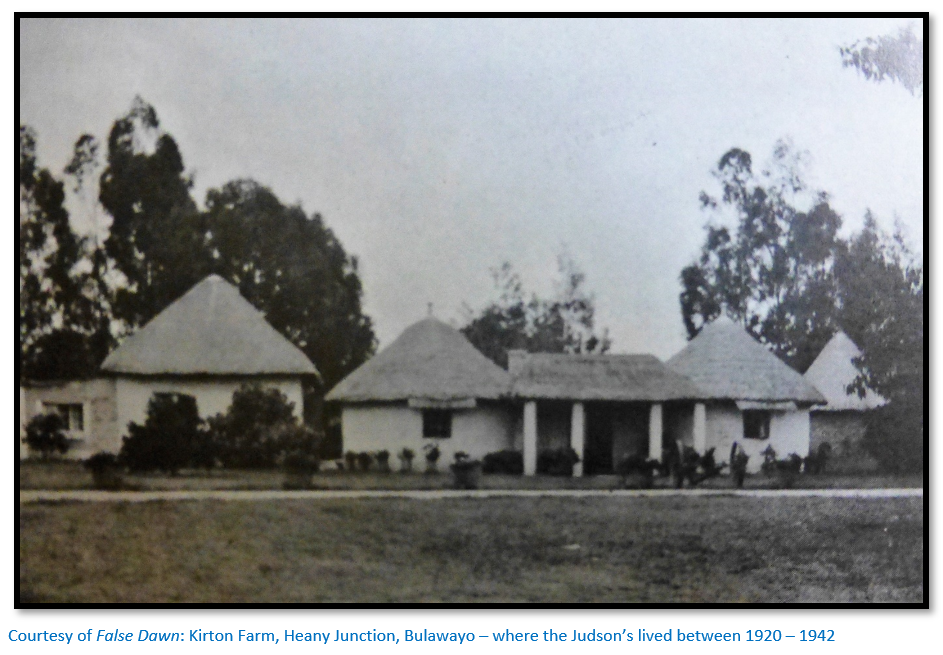

The Judson’s home

Tom Judson, Dan’s brother, who arrived at Salisbury in 1892 had built a large one-roomed brick home on the western side of the kopje facing the racecourse which he loaned to the young couple although both he and Dan lived in the mess next door whilst Mrs Greenfield nursed Maynie. As soon as Maynie was well, they moved into the two-bedroomed mess whose thatched roof made narrow veranda’s at the back and front. Outside was the kitchen with a cracked stove which was patched with mud every few days to retain heat.

Furniture was bought at the Saturday sales at the Market Square and included a large dining table and six chairs, a bed and dressing table described as “an abomination of cheap stuff made especially for the colonies, but you could see yourself in the mirror and the drawers did pull out and it did not warp as most furniture did.” Most importantly, Dan managed to hire a piano from Homan, a Salisbury merchant and agent for the important South African firm of Julius Weil.

At first Maynie thought living in Salisbury was comparatively cheap. Mutton, actually goat, was 6d and beef 8d a lb. All cattle were native bred and delicious eating. All vegetables were supplied by the Indians and Chinese who had gardens on the Makabusi (now Mukuvisi) River. “Everything was plentiful and cheap and brought to your door in donkey carts. The stores could provide you with anything you wanted in a tin and the quality was excellent. The bright yellow Danish butter in large orange-coloured tins with that lovely nutty flavour we can never get now will long be remembered. Whisky was 4s 6d a bottle and other drinks on the same scale.”

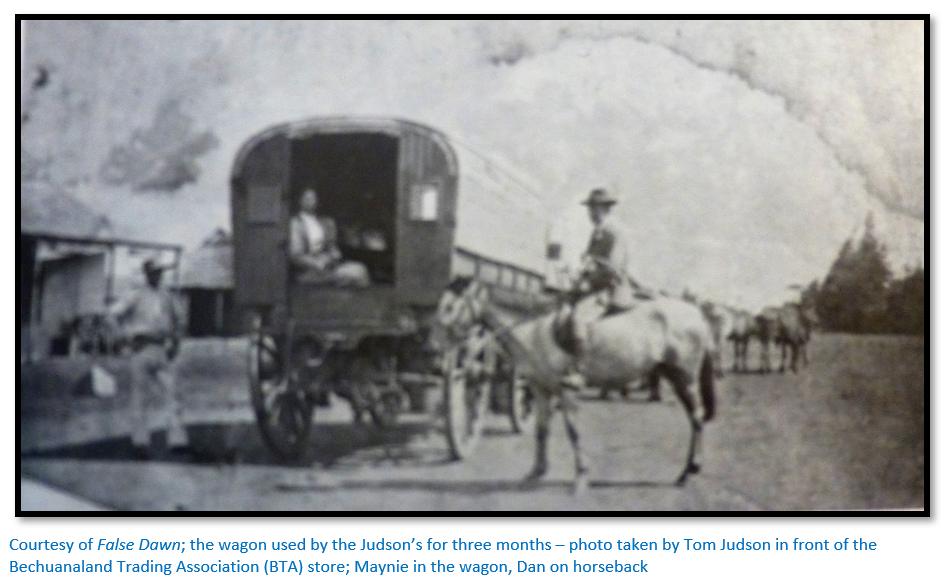

The kopje side was better provided than the Causeway side of Salisbury. Maynie says there were butchers, bakers, general dealers, large trading stores, one of which was the Bechuanaland Trading Association (BTA) and agents of every sort. There was a lending library, a photographic store and several newspapers.

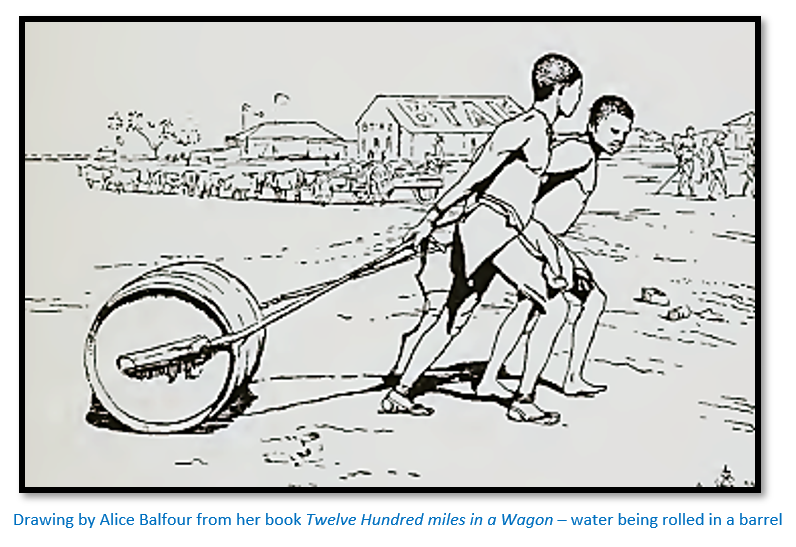

The greatest difficulty was water which was brought from the Makabusi River in large wooden barrels and rolled by natives. This water had to stand so the mud sank to the bottom and then was strained through muslin cloth to get rid of the grass and insects before it was boiled and put in a water-cooler hung from a tree.

Bathrooms were never built due the water shortage. A high back hip-bath was brought into the bedroom and into it was poured a paraffin tin of hot water with a tin of cold placed beside the bath. The bather would pour cold water into the bath to the required temperature, then lower themselves in and sit there.

An inspection of the telegraph line to Victoria and the new line to Bulawayo

In November 1894 the Postmaster-General at Cape Town instructed Dan to make a personal inspection of the telegraph line from Salisbury to Victoria and to establish why there was a delay in linking Bulawayo with Charter. Native Commissioner Coole had taken on the contract for supplying wooden poles and a telegraph employee was responsible for erecting them, but the contract was slow and this second telegraph line connecting Salisbury to Bulawayo and the south was required urgently.

The Judson’s spend three months in a wagon

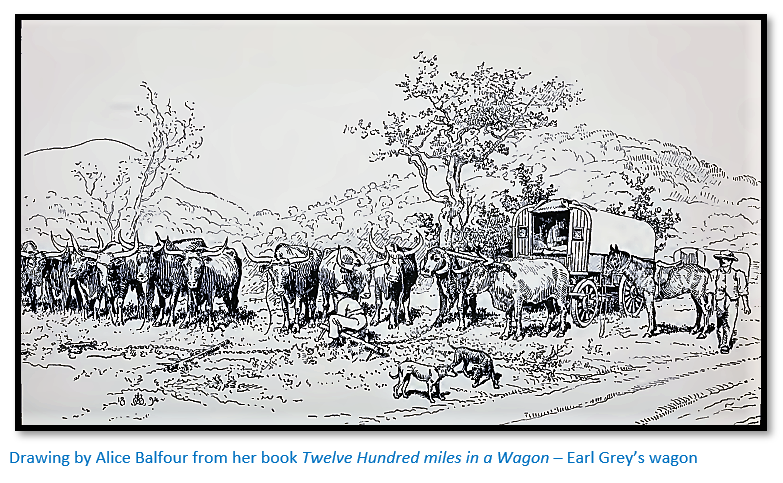

The large tented wagon the Judson’s used for their three month trip had been brought into the country by the Earl and Countess Grey and auctioned in Salisbury when they left. The Grey’s and Alice Balfour had left the wagon at Chimoio; the last stop because thereafter was tsetse-fly country deadly to oxen. Jesser Coope had arranged for their belongings to be taken to the railhead at the ninety mile peg by carriers and Alice Balfour travelled in a machilla, or hammock. This was exactly the reverse of the Judson’s journey from Beira and Jesser Coope had been Dan’s unasked host on his own journey down!

They left Salisbury on 5 November 1894 stopping at the BTA store for Tom Judson to take the photo below of their outfit. Maynie wrote: “At first I got knocked about a great deal, not being used to the peculiarities of a wagon on springs. I tried sitting on a little camp stool on the floor of the wagon…I had to clutch hold of anything in reach to keep myself from being landed on the opposite seat...We got to the six-mile spruit at 5pm and took out our stools and small iron table. The boy laid the table and we had tea about seven. The scenery is simply lovely, thickly wooded and lovely grass.”

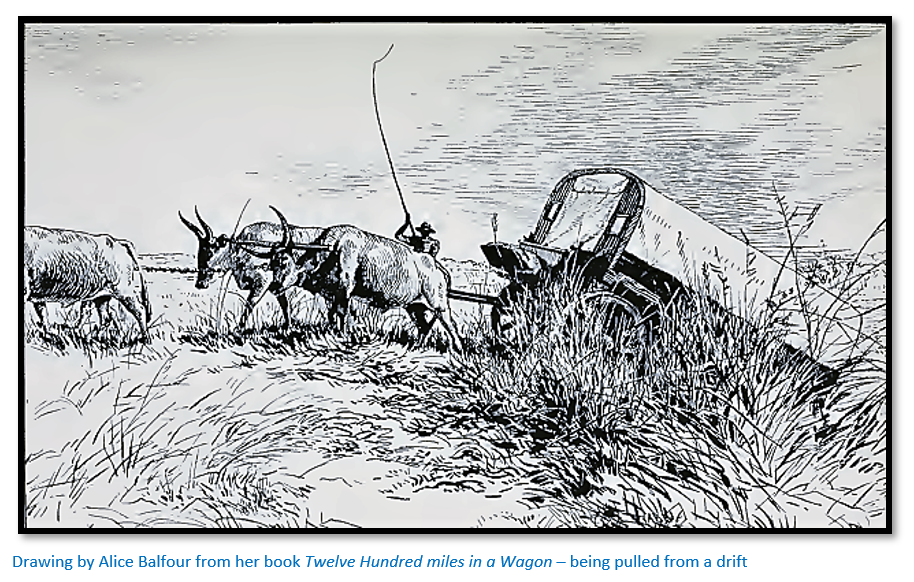

All went well until they reached the Hunyani River (now the Manyame) Here the banks were very steep and though they managed to get down safely, the wagon stuck on the way up the other side for some time because of huge stones.

The wagon itself was unusually luxurious; lined with green baize and with brown Holland pockets attached to the walls. The lockers in which they kept stores, clothes and tools on each side of the wagon had cushions that made comfortable seats. At the wagon rear were steps that lead up to the only door which had narrow windows on either side. The steps were hinged and when not in use were turned back under the wagon and held in place by hooks. In the front, behind the driver’s seat, were two sliding windows, beneath a spring bed which was screened off with a curtain on a brass rod; folding chairs and a table were stored beneath the bed.

All the large household items, cooking pots, tools, water-carriers and spare riems were slung under the wagon along with a crate of hens.

The driver’s personal belongings were stored in a big locker which made up his seat. Their driver was an Afrikaner, Franz, an expert at his job and good with oxen, who seldom used his whip and was always cheerful.

Lion’s spruit was aptly named and the horse and oxen were kept close to the wagon overnight. They usually trekked at dawn, stopped at 8am for breakfast and trekked until noon, rested and then trekked from 2pm to 4pm when they outspanned for the night.

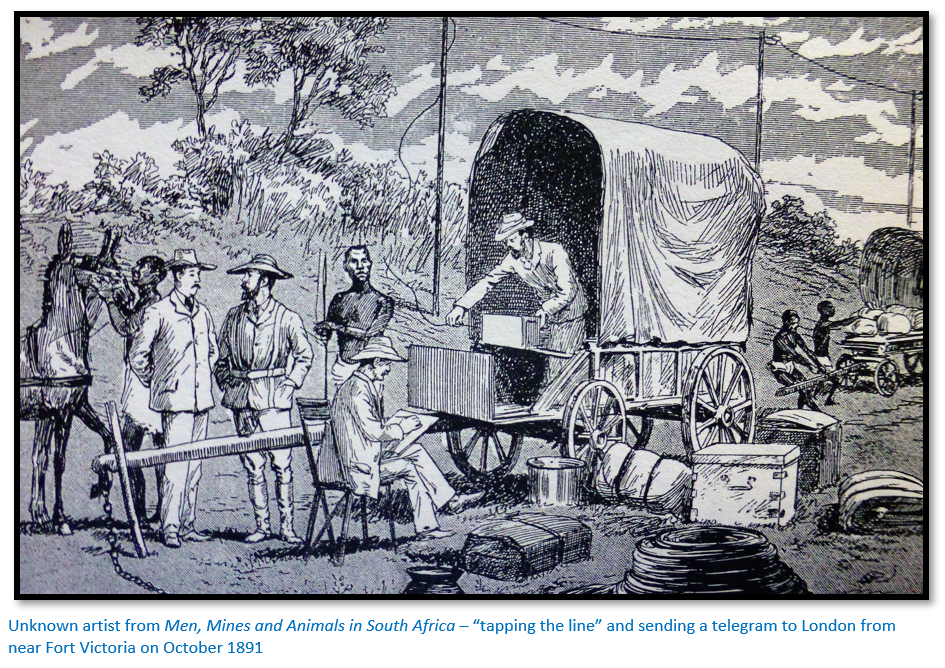

Dan rode on horseback so he could follow the telegraph line when it left the road. They relied on wayside stores for meal, flour, sugar, tea, coffee and rice. If stores were unavailable, Dan tapped the wire and they were brought down by the next coach along with mail and newspapers. Fresh eggs and chickens could be traded with local Mashona for cloth and beads.

They reach Charter

The journey to Charter took five days; on 10 November only three people were present; Carey the telegraphist, a storekeeper and a policeman of the Mashonaland Mounted Police [MMP – the BSA Police only being formed on 29 December 1896] Next night was spent at Homans Store and Wayside Inn on the headwaters of the Umniati River where Dan found plenty of fallen poles which had to be replaced.

Dan’s notebook records each pole that needed replacing and why. Some were erected in an ant nest, others had dry rot, some were charred by veldt fires, others were buried too shallow and shook with every gust of wind, some were too close to river banks and sometimes they were out of line. Broken insulators need replacing and branches of trees needed cutting away. Often transport wagons deviated from the road and knocked down telegraph poles and dragged the wire with them until it broke. Where a pole was on the roadside, semi-circular ditches were dug around them.

After Charter they were no longer able to get supplies and mail on the coach from Salisbury as since the 1893 Matabele War the coach branched off at Charter and went through Gwelo to Bulawayo and this had become the main route into the country. Those who followed the old Pioneer Column route up through Victoria caught a local coach from Victoria which left the old road at Macowrie [or Makowrie’s] and joined the Bulawayo road not far from Thaba Insimbe, the Iron Mine Hill.

On 21 November as the telegraph line was three kilometres from the road, Maynie did not see Dan all day, but she did meet up with the Victoria linesman, Histon, who arrived with a wagon carrying thirty iron poles and they camped at Macowrie. Here NC Coole who had the contract for supplying wood poles for the telegraph line owned a “very superior store” where Maynie bought fresh milk.

For the rest of the trip to Victoria it rained heavily and the wagon leaked badly even though they stretched waterproof sheets across the roof: “every blessed thing was wet, boots, stockings, clothes.”

Victoria in 1894

They arrived at Victoria: “Coming to this place one can see nothing but iron roofs, then you dip down into a hollow and up again. The hospital stands out very prominently; it is thatched and looks nice and cool. Victoria is a larger place than I thought. It stands on a rise between two rivers, one is the Imshagashi [Shagashe River] and it is almost surrounded by kopjes which look very pretty in the distance. There were only about four stores, a butcher, a baker, but no barbers, shoemakers or drapers. There was a good tennis court and “there were about ten fellows playing there yesterday afternoon and one lady...I am told that eight months ago there were about five hundred people here and now there are just about forty. I wonder why?” [most had left since the 1893 Matabele War for Bulawayo or Gwelo]

There were two churches; one Roman Catholic with Fr. Joseph Ronchi, S.J. and the English Church where Maynie was thrilled to play the harmonium. They stayed for a week, gave a small dinner party and visited Great Zimbabwe on 5 December. It was one year and a few days since Alan Wilson and his men were killed at the Shangani River [see the article under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] and Maynie commented: “If ever I was disappointed and disgusted with anything in my life, it was with that grave. There is a good square of ground enclosed with barbed wire, through which we had to creep. At the right-hand side is a huge grave covered with red-clay soil and big stones all round it, and that is all there is to remind us of all those fine, brave men.”

The journey continues

They left Victoria on 8 December for Thaba Insimbe (Iron Mine Hill) to establish what was delaying the completion of the Gwelo-Charter telegraph line. At Macowrie Dan tapped the wire and requested Histon leave ten iron poles at Charter. The road they took was that cut by the Victoria Column in the Matabele War a year before but was now very overgrown and travel was slow. They reached The Junction and Homan’s store where the roads from Gwelo, Victoria and Charter met and trekked on to Thaba Insimbe seven kilometres away where they outspanned and met NC Coole.

Coole explained that of the three thousand eight poles he had laid, seventy had been condemned by Squires, the inspecting officer, and Pearson had condemned three hundred and fifty-nine. Coole said he had erected two thousand poles before any had been inspected on-site…Pearson said his orders were to inspect them as they left Coole’s yard, not on-site.

Dan and Coole rode on to Coole’s camp and found that in fifteen kilometres at least half the poles were too short and did not meet Transcontinental specifications, although he conceded they were better than those erected on the Salisbury-Victoria telegraph line.

The Junction

Wednesday seemed to be the day when the coaches from Bulawayo, Salisbury and Victoria converged. The Salisbury coach was due at 3pm, but although Maynie waited, it did not arrive all afternoon, neither did the Bulawayo coach due at 10pm. Both arrived next morning, the Salisbury coach at 7am, the Bulawayo coach at 6am: “with a tremendous load, eight passengers and full up with luggage, and I could have sat down and cried when I saw there wasn’t a blessed thing for us.”

Christmas Day, 1894 and back to Charter

Christmas Day dawned cool and cloudy, benches of poles were made for either side of the table with the two camp chairs at its head and foot. A sheet did as table cloth and the decorations were wild flowers, coloured leaves and greenery with crackers, almonds, sweets, nuts and raisins on the table. Cooking in the open had been difficult, but the menu consisted of: “jugged hare, roast fowl, roast beef, vegetables, French beans, stewed green peas and asparagus, beetroot salad, plum-pudding, brandy sauce, jam tart, custard, preserved peaches, sandwich cake, coffee, wine, beer and minerals. The only failure was the jelly which would not jell and the only contretemps was when one of the guests poured custard over his asparagus, thinking it was sauce and was too polite to leave it….There were four prospectors and two storekeepers and each, as asked, brought his own knife and fork.”

Dan condemned seven hundred and twenty-two poles between this camp and Charter and thirty-one out of forty-two at Charter. He was told to return as the line was in such bad condition.

They took the road to Charter and with no further telegraph poles to inspect were back in four days arriving on New Year’s Eve.

Charter

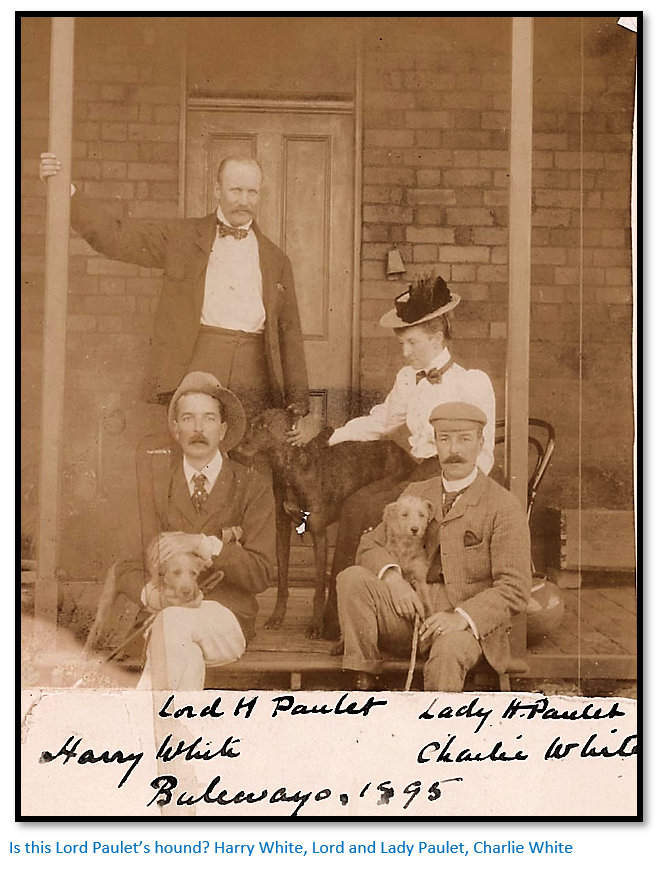

But after two weeks at Charter, Maynie was bored. It was just like Mark Twain’s sea voyage diary: “Got up, washed, went to bed.” They lost three cows which died of “something or other” and left on 14 January 1895 taking with them “a hound for Lord Paulet, an awful beast.”

Adventure on the return home

At their first outspan less than ten kilometres from Charter on Erdington Farm Dan received a note from the farmer named Jarvis for help to hunt a leopard [Maynie calls it a tiger] Dan lent Jarvis his shot-gun loaded with ‘loopers’ [solid bullets fired from a smooth-bore] and kept for himself a Martini-Henry. They set out, Dan mounted and Jervis on foot and were just thinking of returning when the leopard charged at Dan: “My horse swerved with such rapidity that I lost my left stirrup and very nearly came to the ground…the mare bounded off, with the leopard in pursuit, for about thirty metres…I was momentarily expecting to hear the discharge from my companion’s gun as the animal had passed him at close quarters and I had shouted: ‘For God’s sake, shoot.’ Unfortunately, he was unable to see vertical lines in the rifle sights, and any others showed dimly, so the leopard flashing past would not have been seen by him at all.

When the leopard gave up the chase it turned furiously on Jarvis, who fired and wounded it in the leg with one barrel, but unfortunately was unable to use the other. He therefore swung the gun and struck the leopard a blow which broke the gun in pieces, and the man and beast went down together, Jarvis with a grip on the animal’s throat. I rushed up and aimed a bullet in its shoulder and another through the head – and none too soon, as Jarvis had all his work to do to hold on and was bleeding profusely from numerous scratches and a nasty bite in his hand.”

Maynie wrote: “I saw Dan, accompanied by a very battered looking man, appear out of the bush and four natives carrying the dead leopard slung on poles…we at once set to and washed his wounds, but we had only permanganate and there was no time to try anything better locally. I tore up an old sheet and we used Vaseline freely and bound up his wounds as well as we knew; we knew nothing about treating for shock…fortunately, the mail coach passed that evening and he was put on board and sent to hospital.”

When they arrived at the Umfuli River [now the Mupfure] where Zeederberg had a post station for changing mules they heard a lion had been terrorising the animals at night. Franz their driver and Dan decided to sit up and wait for the lion. It was a moonless night and the fire lit up the nearby cattle kraal and Maynie sat with them as, with loaded rifles, they sat facing down the road.

At 11pm Maynie brought out some food and a bottle of good strong tea. Unfortunately the young servant had brought the tobacco tin and not the tea tin and Dan gulped down a strong infusion of Boer tobacco. He wrote: “I only discovered the mistake after I had gulped down some of the vile beverage; the result being a strong desire to hang myself across the disselboom with complete disregard for lions, tigers, wolves or anything in creation.”

Dan went to bed with a splitting headache, but was woken at 1am by Franz: “It was just 1am and as my head was aching furiously and further sleep out of the question, I made my way out into the kraal and took up my position in a dark corner close to where on a strip of white sand I had placed the remains of the cow as bait for the lion…about an hour went by without any interruption…suddenly an old ox started sniffing and gave a snort. As the post-boy had previously mentioned that one particular ox always gave the alarm, I was on the alert. After a few minutes some of the cattle started a lowing kind of moaning bellow and some young calves, evidently affected by the prevailing terror, crept up against me; one putting its head right between my legs. A faint booing noise came from down the river and I knew the visitor was coming.”

But at that moment shots were heard in the distance and then five wagons arrived near their camp making a great deal of noise which drove the beast away.

The next night Franz made a seat in a tree and as Dan prepared to go up onto his platform, Maynie said she wanted to join him: “At first he would not hear of it, but I said I wanted to go and I went.” They took two blankets, pillows, a lantern, strong tea, meat and bread. She wrote: “Well, we got the boys to put thorn bushes round the tree to prevent anything getting under us and they put an ox-skin and a piece of meat in a place where we could easily watch. Then they took the ladder away, so we were left perched up this tree. It was then 8pm and Dan had hardly settled down then he fell asleep…I let him sleep for an hour while I was straining my eyes to see something that wasn’t there. At about 10pm we were disgusted to hear wagons coming in; we were almost certain that after all that row a lion wouldn’t come near.

About midnight everything quietened down and we could hear the oxen and cows puffing as if they were frightened…we only spoke in soft whispers as everything was as still as death and sometimes, we wouldn’t say a word for half an hour. All of a sudden, we heard something behind us breaking a twig. I called to Dan in an awestruck whisper ‘what’s that?’ and ‘hush’ was all the answer I got. All was quiet again and soon after we heard it closer by. We could hear then that the animal was crunching dry bones. The night was terribly calm and still; all you could hear was the ‘crunch, crunch’ and quiet again.

At 3am Dan suddenly lent forward and whispered right up against my ear; ‘I see two eyes looking this way. Hold on, I’m going to shoot.’ The report was deafening and shattering. I felt as if I’d been flung out into mid-air. Before I could gather my wits, there rang out the most blood-curdling groans and howls.” Fortunately the other wagons inspanned and they knew that the noise and yelling at the oxen would prevent any animal from approaching, so Dan shouted to the boys to bring the ladder. When Maynie reached the ground she saw Dan with lighted lantern bending over the animal. To her great disappointment it was not a lion, but a ‘wolf’ – an enormous hyena.

The telegraph line connects with Bulawayo

Dan having settled the pole-laying dispute, the line between Charter and Bulawayo was quickly erected and from 7 February 1895 was transmitting telegraphic messages. There were then two lines south from Charter; one to Victoria and on to Palapye. Squires took the line through Mangwe Pass to Macloutsie where the two lines met making it the transmitting station to the south.

Back in Salisbury again

After their three month trek, Maynie was cured of adventure. They settled into two rooms attached to the Post Office with verandas back and front and empty ground facing Manica Road (now Robert Mugabe Road) which they converted into a croquet lawn. The greatest difficulty was that there was no kitchen and Percy Inskipp encouraged Maynie to see the Administrator, Dr Jameson. This she did and a wood-and-iron kitchen was built for them, Maynie recalling: “That was the only time I met the famous little man, and all I can remember are his piercing dark eyes and sense of humour. He seemed on the edge of laughter all the time.”

They liked their rooms; the main drawback being the proximity to the Post Office as Dan would hear the telegraph instrument clicking after working hours and feel compelled to check on it. After six months they had to move and found themselves again on the western side of the kopje facing the racecourse with: “A wide veranda; you walked into a passage, a sitting room on the right and bathroom to the left. Then through an archway into fairly large dining room and leading out of that was a good-sized spare room and at the back you walked into a kitchen and pantry. By now we had collected quite a lot of furniture of sorts and were very comfortable.”

Extension of the telegraph to Tete

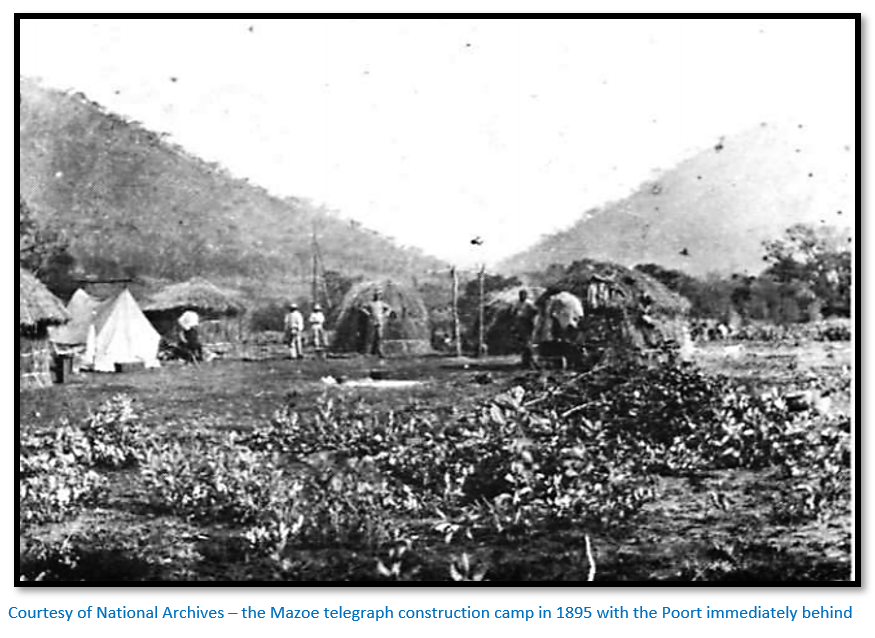

On 23 September 1895 Dan began erecting telegraph poles to Mazoe, and late that evening after setting batteries and their instruments, exchanged signals with Salisbury. The telegraph hut was constructed of branches and grass, as were their beds, and at a late hour they went to sleep. About 4am they were woken by piteous neighs and loud growls…Dan seized his rifle and rushed out, but their two horses and a mule were gone.

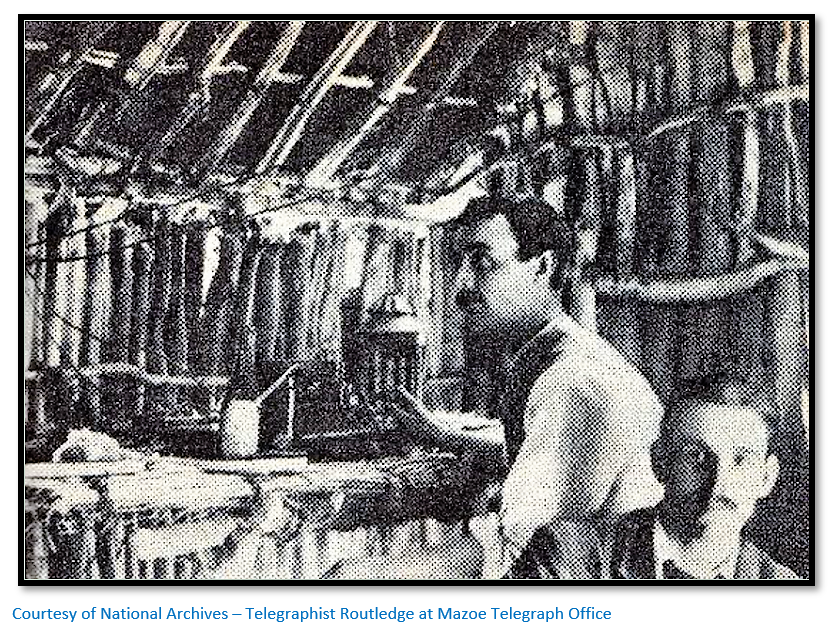

Next morning after following the horses spoor for five hundred metres they found the half-eaten remains of their best horse and some distance later they found the remaining horse and mule still alive but with claw marks down their flanks. Later that morning the Mining Commissioner James Dickenson and his wife, the only European woman in the district, arrived along with the Mazoe telegraphist from Salisbury and the telegraph office was declared open. Also present was Captain Roach, the contractor, in whose wagon Maynie and Dan had travelled from the railhead to Chimoio in May of the previous year.

Events of 1896

Dan’s diary begins on 2 January: “Line down between Gaberones and Mafeking. Right at 3pm. News through of Dr Jameson having crossed into Transvaal with one thousand men bound for Johannesburg.

3 January: 9pm news through of Dr Jameson’s engagement with the Boers resulting in loss of one officer and nine men of Jameson’s forces. Found acting Administrator (Judge Vintcent who had taken Jameson’s place) at Morris’s and informed him. He and Fox came to the office, but no further news.

4 January: News through of Jameson’s surrender to Boers with loss of eighty men killed. Line open until late.

5 January: line closed at 3am. Open again at 9am till noon, but no further news.”

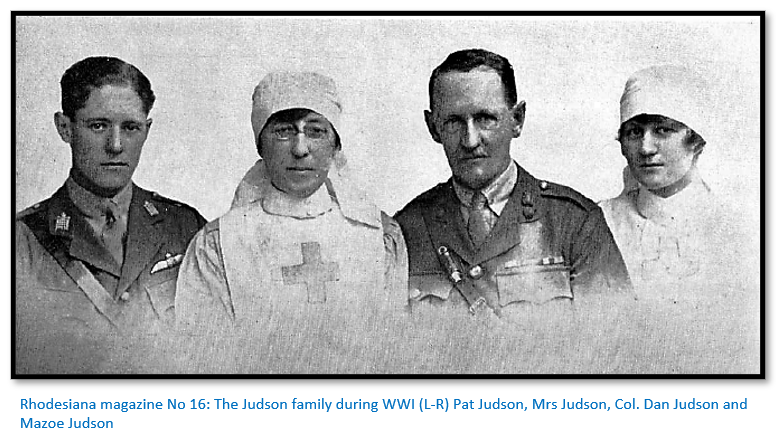

On 10 February their first child was born and christened on Sunday 8 March at their home as Edith Mazoe Judson.

It was just over two years since the 1893 Matabele campaign, in which time Matabeleland, Mashonaland and Bechuanaland had suffered from drought, locust plague and finally rinderpest. [Wikipedia quotes studies stating over five million cattle were killed south of the Zambezi River, as well as sheep and goats and wild populations of wildebeest, buffalo and giraffe]

In late March 1896 the Matabele Uprising, or First Umvukela began with the widespread killing of European prospectors and miners, farmers and transport-riders.

Gwelo laager

Dan was at Gwelo and his diary records the events:

25 March: “Fresh news of native rising which is believed to be serious. All whites in outlying districts ordered into Gwelo (now Gweru) Gwelo troops of Rhodesian Horse called out. 6pm: young Napier rode in from Shangani, says natives killed O’Reilly [T. O’Reilly death is confirmed in the Reports] and are massing in thousands near Shangani. Twenty men, women and children laagered there. 8pm: Rifles and ammunition served out. Self was appointed Intelligence Officer. Ordered Selukwe telegraphist to close office and come into Gwelo with apparatus. Found laager around Court House. Mounted patrol and picquet to be sent at midnight. Only anxiety felt is fact we have only two thousand rounds of ammunition and forty rifles.

26 March: Everyone in laager last night and sentries posted. Mr Driver (ANC) went out to Police camp last night in order to disarm his boys, said he would be back early, has not turned up yet. Lt Chawner and two men have gone to look for him. A patrol of six men and a mule wagon left at 5:30am to relief of the Shangani laager. Capt Gibbs with twelve men and two maxims left Salisbury for Gwelo at 11pm last night.

9:30am: Telegraphist at Iron Mine Hill informs me that everyone is coming into Gwelo. Instruct him close office and come in, bringing instruments and valuables with him.

6pm: Selukwe contingent arrived (about seventy) with about ten wagons, also women and children. The combined laagers make a fine sight. On top of one of the wagons, heavily laden with household items, were perched two pretty little children, seemingly quite enjoying the excitement.

27 March: Shangani people arrived this morning, in all twenty including women and children and one wounded man. Report that all the stores are looted and nineteen whites killed and missing. Amongst killed are two women and two children, in fact one whole family. [in fact, thirty-two men, four women and nine children; forty-five in all were killed in the district] Captain Gibbs with the two Maxims passed Charter this morning. Am leaving with patrol this evening to meet Maxims at Iron Mine Hill.

Dan arrived at the Iron Mine Hill at 6am the next morning; he found that the store and the telegraph office had been broken into and items stolen. Some of his men took alcohol from the store and only stopped drinking when Dan threatened to report them. As Captain Gibbs and his party had not arrived, Dan rode towards Blinkwater, meeting a wagonette of evacuees from that place. They spent the night at Blinkwater and early next morning met Captains Gibbs and Tennant and ten Salisbury men with the Maxims.

At Iron Mine Hill Dan tapped the line to Gwelo and learnt there had been fighting in the Matoppos and at Maven’s, thirty kilometres from Gwelo. Two bodies had been found within ten kilometres of Gwelo; the situation was serious.

Captain Gibbs assumed command at Gwelo and infuriated everyone by having a test alarm at 4:40am next morning. Dan wrote: “Great excitement of course, and various weak points were discovered which will be rectified today…most of the buildings in the vicinity of the laager were demolished and laager re-formed, being now triangular in shape instead of square…Napier’s store at Shangani looted and body of white man found near it.”

1 April: “on testing at 9am found Bulawayo line disconnected. Tested to end of loop, perfectly clear. Informed Captain Gibbs of my willingness to go out in search of the fault with small patrol but owing to scarcity of horses he cannot arrange patrol until tomorrow.”

2 April: “I left laager this morning with patrol for Shangani, object being to endeavour to repair the telegraph line. Patrol under command of Capt. Hurrell, other officers being Lieut Fletcher and myself., rest of patrol consisted of sergeant and twenty-four troopers, all picked men. After three or four halts we off-saddled at dusk about four kilometres from the famous Shangani River. Here we spent the night, taking every precaution against surprise. A few miles ahead we could see the glare of a large fire in the hills and the members of the patrol who had previously resided in the Shangani district gave it as their opinion that the Shangani store and hotel had been fired.

The night was uneventful and at 3:30am we were up and standing to our horses, waiting for the first streak of dawn to make a move onwards. This was necessary as it was essential that the telegraph line be closely followed. Away in the kopjes to the south-west we saw signals flash up out of the darkness and knew that our presence was known. At 4:30am we were on the move and an hour later crossed the river at the telegraph line and then cut across to the store which is situated on the Shangani battlefield.

We were not surprised to find the whole place – store, hotel and outbuildings – a smoking ruin. The scene was a harrowing one. The walls were standing, although here and there great gaps showed where they had either fallen or been pushed in. The heavy poles of the scherm (stockade) which had been pulled out and flung on the flames, were still burning thickly and the ashes all glowing hot, showing that the place had only been fired on the previous evening.

In the roadway, a few feet away, was lying the naked body of a white man, a well-built fellow, with fair hair and moustache. He presented a horrible spectacle. His legs were ripped up and there were numerous assegai wounds on the body, from one of which entrails were protruding. The Shangani men with us could not identify the body but supposed it to be one of the cattle inspectors. The assumption is that he arrived at the store, found it was deserted and was then surprised by a party of Matabele lying in wait for passing travellers. [possibly Wienand or Wren, both listed as cattle inspectors and killed at Shangani]

A dozen dead pigs, big and small, were lying about covered with assegai wounds and at least twenty fowls similarly treated were scattered here and there. Circling around over the smoking debris was a flock of pigeons searching vainly for their home. The veldt was strewn with bottles of all kinds of liquor; whisky, brandy, claret, port, lime juice, etc. Some intact, but in most cases the ground was wet with the contents of those which had been thrown about and smashed. In and about the flames could be seem all sorts of tinned provisions, and as we had decided to go on further and were running short on food, I collected a few uninjured tins of bully beef.

A number of fowls were running about so we knocked one over the head and put it, feathers and all, into the hot ashes. Vedettes (mounted sentries) of course were posted and we breakfasted. The close proximity of the dead man did not affect our appetites. The horses, closely knee-haltered and guarded, grazed close at hand.

At the conclusion of a hasty meal we picked up the body of the murdered man on a sheet of galvanised iron and were carrying it off for burial when two of the vedettes came galloping in and gave the alarm. A strong body of natives was advancing in single file about one kilometre off, their evident intention being to block Shangani drift.

The body was regretfully placed on the ground and we hurriedly saddled up. In a few minutes we were making for the drift, which we crossed safely, being then in fairly open ground. We cut off into the veldt at right angles, and after going a short distance sent scouts out to reconnoitre. The enemy, however, lay low and contented himself with driving a very fine herd of cattle to a glade a kilometre distant; but the snare was too obvious and Capt. Hurrell decided he was not in want of beef just then. We moved about the vicinity of the Shangani for about an hour, and as it was plainly perceptible that the enemy was in force it was decided to retreat. We arrived at Gwelo at 9:30pm, much to the relief of the O.C. who was becoming anxious concerning our safety.”

5 April: Mashonaland route restored. Church parade at 9:30am. Rev. Griffiths preached a short but stirring sermon. Laager life getting very monotonous.

6 April: Two Cape boys carrying despatches from Mr Duncan at Bulawayo arrived. Owing to sensational telegrams, impression at Bulawayo was that Gwelo had been sacked by the enemy. The boys report wire cut and about a mile of poles down between Shangani and Tokwe Rivers.

7 April: This afternoon everything quiet in and around laager. Self-suffering from diarrhoea.

8 April: Nothing fresh, still ill.

9 April: News in from Bulawayo that Gifford’s party had engagement near Shiloh with enemy, repulsing them with heavy loss. Our casualties were Gifford and three others wounded and Troopers Mackenzie and Reynolds killed. Further news from Bulawayo that Capt. MacFarlane, who went with Maxim and sixty men to relieve Gifford, reports Gifford had further engagements with enemy. Enemy however, attacked position five times in two days. Capt. Lumsden and Lieut. Hulbert seriously wounded and Trooper Herman crushed by falling horse. Gwelo vedettes saw column of smoke about Shangani and afterwards heard distant report. Supposition is that Eagle Mine, Tokwe which had heavily stored dynamite and detonators, has been fired by natives and proved somewhat of a surprise packet.

11 April: O.C. proclaimed holiday from fatigues to allow of a cricket match between Gwelo and Selukwe. Former won easily: score being Gwelo eighty and four wickets, Selukwe twenty-seven. Distafler of telegraph staff bowled remarkably well, taking six wickets for ten runs. The match was played close to the laager, the pitch being the main street which is now almost open ground.

The three hotels and most of the buildings have been destroyed by the military authorities. I did not see the conclusion of the match as, about 5pm, some news having come to hand, I was busy writing it up when Capt Tennant came in to get his spurs and informed me that the vedettes, on a hill about a kilometre from the laager, had sighted a body of about forty natives, eight kilometres to the northwest.

A mounted patrol of twenty-five men was to leave at once to try to intercept them. Anything for a relief to the general monotony, so down with pen and paper and five minutes later I was one of the party which cantered smartly away from the laager. Greeted by a cheer from the cricketers.

This patrol was unsuccessful. They found nothing but a pair of ammunition boots and it was dark when they returned to the laager. Next morning, Sunday 12 April church parade was held at 7am, but there was no sermon and “owing to scarcity of books the singing was dismally feeble.”

Dan noted: ”We are now cut off from communicating with the Cape via the Mashonaland route which has been intercepted between Victoria and Tuli. The Gwelo – Bulawayo section, of course, is not yet repaired.”

13 April: “Had a bonfire in centre of the laager…a very good improvised concert. It could not be kept up for long however as ‘lights-out’ sounded at 9pm and the strictest military discipline is observed. Several have already been fined £2 for showing a light during the night.”

There was a false alarm that night. Dan always had his kit ready so he could reach his clothes and equipment in the dark. That night it was very cold and he was tightly rolled up in his blankets, his boots on the floor, rifle leaning against the wall, his hat close, his coat, all that he removed, was his pillow. He was awakened by someone treading on his stomach and the cry of: “Turn out the guard” and from somebody else: “My God! They are on us!” He was up in an instant and reached for his boots, but only found a size eleven, when he took a size six. At the same time his neighbour was cursing he could not get his foot into a size six! They exchanged and Dan having got one boot on the wrong foot could not find the other. Having banged his head against a pole, he rushed out minus his coat and one boot to find everyone ready to start: “blazing but nothing to blaze at” and after ten minutes shivering in the cold the “disperse” was sounded.

Explaining the event Dan wrote: “It appears that one of the picquets challenged a brace of donkeys in the orthodox manner and for the regulation number of times. Receiving no reply and magnifying the said donkeys into an impi of Matabele, he discharged his rifle at them and bolted for the laager. This action was contagious and the remainder of the picquets were at his heels. The barbed wire entanglements, forgotten in the excitement of the moment, retarded them somewhat, not to mention considerable renting of trousers and shedding of blood, but they all got in in record time, only to be sent out again after a severe admonishment by Capt. Gibbs.”

14 April: Mashonaland line still down. Latest news received from Bulawayo was that Capt. Brand’s patrol of one hundred men had returned to Bulawayo, having had a severe engagement with the enemy, our casualties being six killed, seventeen wounded and thirteen horses killed.

15 April: Mashonaland line now restored. We hear that forts are to be opened at Figtree and Mangwe Pass.

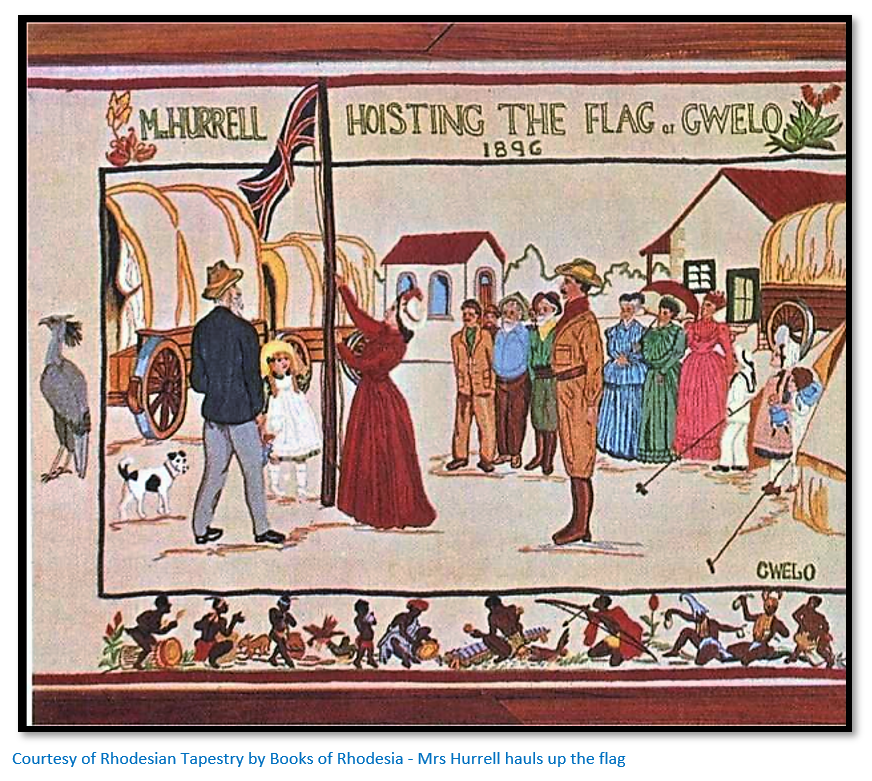

17 April was the birthday of the first Gwelo baby, Davy Hurrell and Dan wrote: “The sergeants opened their mess and celebrated the occasion by a very enjoyable smoking concert in the evening, at which Mrs Fife-Scott and Mrs Hurrell charmed everyone with their sweet singing.”

The next day: “a rough flagstaff was erected in the laager and a general parade ordered at 1pm, in the presence of which Mrs Hurrell pulled a cord and the brave old Union Jack was unfurled to the stirring notes of the general salute.”

20 April: “News received this afternoon of an attack in Bulawayo. All Maxims in action, Matabele repulsed with heavy loss. Influenza bad in camp, fifty being sufferers, nights very cold. Rinderpest carrying off cattle rapidly, ninety-six found dead in kraal this morning.”

27 April: “Scouts sent out to Shangani, left at 10am. Sergeant Taylor and four others. For days and days past I have been suggesting that Shangani should be one of the first places to be visited by scouts, but Capt. Gibbs has been strangely lax in this respect, and although we have fifty horses and two hundred mules, we are absolutely ignorant of what is taking place around us. I have repeatedly offered to go with one man to Shangani to repair the line, but the O.C. will not allow it and now he has sent out these scouts without informing me or asking me to take the opportunity of attempting to repair the lines.”

Fair comment as Dan was in charge of the telegraph with a responsibility to keep it open. When the scouts returned, they reported all was quiet at Shangani, but next day they learned the nearest post-stable from Gwelo had been burnt down.

29 April: “Salisbury column [led by Capt, then Lt.-Col Robert Beal – a relief column of one hundred fifty men from Salisbury] now at Iron Mine Hill”

30 April: “Salisbury column ten miles from Iron Mine Hill at 10am. Report natives in front of them.”

1 May: “Capts Tennant and Hurrell, Lieuts Jarvis and Judson left at 5pm to meet Salisbury column. At 8:45pm saw laager lights in the distance. On approaching to within one thousand metres heard a rifle shot and then the alarm. Managed to get in all right. Seems one of the natives had fired rifle accidently.”

2 May: “Column arrives at Police Camp, three kilometres northeast of Gwelo at 4:15pm.”

Rhodes arrived with the Salisbury column and the Dominican sisters Patrick and Amica who had come to open a hospital. At Enkeldoorn (now Chivhu) they found seventy men and one hundred and twenty women and children huddled together in the laager; eighty were ill and the sisters did what they could to help organise sanitary arrangements.

3 May: “Some trouble re command, Capts Gibbs and Beal refusing to serve under each other.”

4 May: “Decided to amalgamate columns. Mr Rhodes to be Colonel and Commander-in-Chief, Capt Gibbs military adviser, Capt Beal promoted to Lt-Col. in command of troops, Capt Hurrell promoted to Major for Gwelo section, Capt Hoste promoted to Major for Salisbury section, Capt Tennant promoted to Major of Artillery.”

Soon after a patrol of one hundred and fifty Gwelo men and one hundred twenty Salisbury men, including Dan, left for Maven’s kraal north of Gwelo. An engagement took place, but there were no casualties. The bodies of Harbord and Walsh were located and buried; Rev. Pelly conducted the service. [Both deaths are confirmed in the Reports – H.M. Harbord was then reburied near his store in the cemetery at Fort Ingwenya – see the article under Midlands on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

On 15 May, Lt-Col. Plumer arrived with eight hundred men of the Matabeleland Relief Force and Dan was given permission to return to Salisbury the same day. However, he only managed to leave Gwelo at 3am on 7 July.

Maynie wrote in her diary: “The journey was full of excitement and danger. He travelled by night when he could and never off-saddled during the day. Just sat under a tree and ate and drank what he happened to have, the reins in his hands and his rifle against his knee, keeping a sharp look-out for the enemy. Once he was horrified to see two natives emerge from the bush some distance away with assegais and shields and he knew that meant they were on the warpath. There was not a second to lose. He told me that he never knew how he did it. He was in the saddle and tearing away before the natives realised what had happened. Every moment he expected an assegai to whizz after him, but nothing happened.” This hazardous journey took him two days.

On 9 June Maynie wrote: “Dan arrived at 6pm last evening, looking awful, thin as a skeleton, all shrivelled up by the sun. He is the first man who has come through alone since the rising. His hands are sore and festered.”

The Mashona uprising or First Chimurenga then began (for details read the Mazoe Patrol article on www.zimfieldguide.com under Mashonaland Central)

However, in July 1896 the Mashona Rebellion (First Chimurenga) was far from over, indeed resistance continued into the following year and local forces with reinforcements from Bulawayo required the assistance of Lt. Col Alderson and the Mounted Infantry to go onto the offensive. The ’96 Rebellion Reports contain many accounts of the small patrols that rode out into the remote districts to ascertain if residents were still alive.

Life for the residents of Salisbury, including the Judson’s was difficult and there were a number of rumours of attacks on the town, all of which proved false alarms. Food was short and rationed, although some tea, coffee, rice and sugar could be bought at Deary’s Store for 8d a ration; bread cost 2/6d a lb. The Indian and Chinese communities could not grow vegetables in their market gardens and the lack of milk and fresh fruit made it difficult for Maynie Judson to feed their young daughter, Mazoe.

Judson’s duties as Inspector of Telegraphs

This article does not include the June 1896 events at Mazoe. [For details of Dan Judson’s heroic exploits see the article on the Mazoe Patrol under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com]

On 22 July 1896 Dan and a companion inspected the telegraph line as far as the Hunyani (now Manyame) River. The following day the Defence Committee decided that residents could leave the Salisbury laager and return to their homes in the neighbourhood and the Judson’s were about to return to their home on the west slope of the Salisbury kopje when Dan was ordered to inspect the telegraph line to Charter again.

The telegraph line to Charter was still very primitive; a single wire from Salisbury carried on wooden poles. At Charter there were two single lines; one down the old Pioneer Column route to Fort Charter (now Masvingo) and Tuli and another going via Gwelo (now Gweru) down to Bulawayo. The telegraph lines then converged at Macloutsie and continued as a single line down to Mafeking, at this time the railhead.

The laagers at Charter, Victoria and Gwelo were not only important for keeping the local inhabitants safe, they were vital for connecting Salisbury with the world and each centre had telegraphists and troops and local force who had to patrol the telegraph line and mend it. At the time there were almost daily cuts to the line and the telegraphists were required to repair it constantly. The authorities also wanted a telegraph office opened at Enkeldoorn (now Chivhu)

For some time Judge Joseph Vintcent, the Administrator of the country, had been aware that the section of line around Charter had not been repaired properly; so on 27 July Dan was sent down with Lieut. G.S. Fitt, forty Europeans and eighty-two Mashona with three ox-wagons and a Scotch cart. He was to make repairs to the telegraph line and assess the situation at Charter. After crossing six-mile spruit they reached the Hunyani district the following morning and were having breakfast when they met up with Capt. White’s Patrol returning from rescuing those besieged at Fort Hill [see the article Fort Hill and the Cemetery at Hartley Hills in Mashonaland West on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] One of those wounded was Sidney Arnott who had been a member of the Mazoe Patrol and he returned in the same wagonette belonging to Judge Vintcent that had carried the women and wounded from Mazoe.

This account continues from Hylda Richard’s book False Dawn which contains accounts from the diaries of Dan and Maynie Judson as well as Lieut. Fitt who was second in command of the party.

Dan and his party continued on through Cactus spruit and Telegraph spruit and on testing the line established there was a break further south. At the Umfuli River (now Mupfure) they found the line had been cut and after repairing it, informed Captain Jack Brabant, in charge at Charter, that they were on their way.

Unexpected difficulties with Captain Brabant at Charter

Early next day they met two messengers on their way to Salisbury with despatches; they had been instructed to repair the line fault as well, but as it happened to be five miles away from the road, it seems unlikely they would have come across it! Dan’s party were having breakfast at Tigersfontein when Captain Jack Brabant, Arthur Strickland and others from Charter met up with them. Lieut Fitt wrote in his diary: “From Captain Brabant’s account, the Charter men seem to be a cut-throat lot in their treatment of natives, treating both friendly and rebel natives alike” before they continued on to Charter: “Everyone arrived in good health, but provisions were running out and it was chiefly to replenish these that we came here.”

Jack Brabant had entered the country in 1890 and had been appointed Native Commissioner for Victoria and had been given the rank of Captain in the Rhodesia Horse Volunteers. He had returned from six months leave in April 1896 and on 17 June had become the officer commanding Fort Charter. A later report declared: “On July 13 Captain White and Judge Vintcent expressed concern about Captain Brabant’s conduct and on the same day Colonel Beal reported that Captain Brabant had wantonly executed two African policemen bearing passes signed by Native Commissioner Taylor. Captain Dan Judson, on his arrival at Fort Charter on August 1, reported that Captain Brabant had threatened to shoot two friendly chiefs, and on the 3rd he made serious charges that resulted in the latter’s removal from his command.”

Lieut Fitt’s diary continues: “Charter people say they are short of all foodstuffs so cannot give us any, so before getting back to Salisbury we must forage for ourselves, as meal and mealies are our most pressing wants.” Clearly, he was not aware of Dan’s other task; assessing the situation at Charter.

That evening Alfred Drew, the Native Commissioner at Victoria arrived at Charter having left two hundred and forty of his forces at Shawe’s Store at Altona Farm thirty-five kilometres away to the south on the headwaters of the Sebakwe River where Henry Grant had been killed on 18 June 1896 [this is not far from where James Burton who features in the Mazoe Patrol article worked at Homans Store and Wayside Inn on the headwaters of the Umniati River] and where Dan was planning to go next day to collect grain. However later the same evening, three of Drew’s force arrived to say there had been a fight at Shawe’s Store; a man had been killed and two wounded. Drew left at 2am next morning followed later by Captain Brabant and twenty mounted men.