Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site

The Portuguese explorer Pêro da Covilhã first visited Sofala in 1489 and by 1505 they were given permission to establish a factory and fortress with the express purpose of exploiting the gold resources that were being brought from the interior. On his first voyage, Vasco da Gama had spent March 1498 at Mozambique Island and been given information on the gold trade at Sofala before his small fleet of four ships sailed up the east coast of Africa and from Malindi, with a Muslim pilot, reached Calicut on the south west coast of India in May 1498.

The Second Armada was to be headed by the Portuguese nobleman Pedro Álvares Cabral and comprised thirteen either carracks (naus) or caravels with fifteen hundred men. Ten ships were destined for Calicut in India, while the two ships captained by the Dias brothers were destined for Sofala in East Africa and the supply ship was destined to be scuttled and burnt along the way.[i] Bartolomeu Dias lost his ship at the Cape and Diogo Dias became separated at the Cape, eventually sailing the east coast of Africa. Sancho de Tovar met the blind Sheik Yusuf of Sofala and in return for the cheap Portuguese manufactures of trinkets, mirrors and glass beads received a string of gold beads worth one thousand Cruzados – confirming the wealth of the interior.[ii]

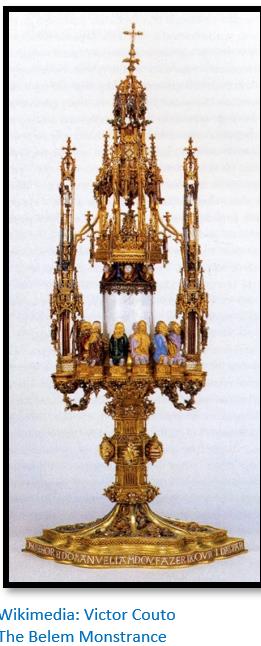

Da Gama set off on his second voyage, the 4th India Armada, in February 1502 and stopped at Sofala before extracting a considerable amount of gold from the Sultanate of Kilwa as a sign of vassalage to the crown of Portugal. This gold was traded through Sofala and was likely mined either at the Manica goldfields, or those on the northern Mashonaland Plateau. The gold was brought back by Da Gama and presented to King Manuel I who commissioned the goldsmith-poet Gil Vicente to make the Belem Monstrance (Portuguese:Custódia de Belém)[iii]

The Sofala gold trade has been discussed in a number of articles on this website including the following under Mashonaland West:

- How Portuguese trade developed in Mozambique during the 16th/17th Centuries prior to the establishment of the feiras in the Mutapa State

- Why did Portugal establish bases on the East African Coast, now Mozambique in the early sixteenth Century?

During the late sixteenth century and the seventeenth century the Portuguese made agreements with the ruling Mutapa’s that led to the establishment of permanent Portuguese settlements and trading fairs ‘feiras’ on the northern Mashonaland Plateau. These are discussed in the following articles:

(3) The rise of the Mutapa State and the early arrival of the Portuguese c.1450 - c.1480

(4) The Mutapa (Mwenemutapa, Monomotapa) State in its heyday c.1480 – c.1623

(5) The decline of the Mutapa state c.1623 – c.1902

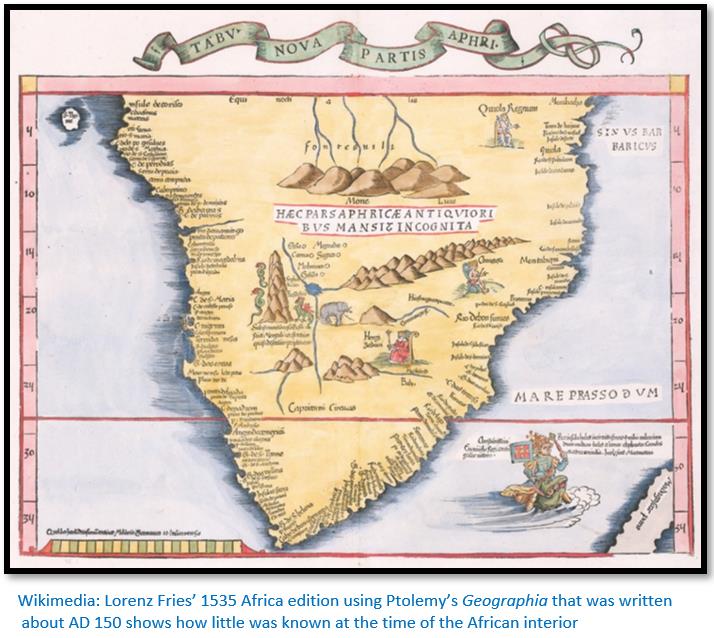

Portuguese knowledge of the sources of gold was initially very limited and their exploration confined to the coastal belt until Portuguese missionaries and explorers travelled into the interior and sent back reports or, as in the case of Antonio Fernandes, dictated reports upon his return. Articles discussing these aspects on the website include:

(6) Antonio Fernandes, probably the first European traveller to Zimbabwe in 1511 - 12

(7) The 1561 martyrdom of Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J.

(8) Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569 to conquer the gold mines of Mwenemutapa (Monomotapa)

(9) Vasco Fernandes Homem and the search for the Mutapa state’s fabled gold mines 1574-5

Articles that include specific Portuguese sites include under Mashonaland East:

(10) Luanze Earthworks and Church

And under Mashonaland West:

(11) Maramuca, a Portuguese Feira dating from 1660 – 1680

(12) Angwa (Ongoe) – Afro-Portuguese Feira sites in Mashonaland West

And this article under Mashonaland Central

(13) Dambarare – an Afro-Portuguese Feira site

Exploration of the interior for the sources of the Sofala gold

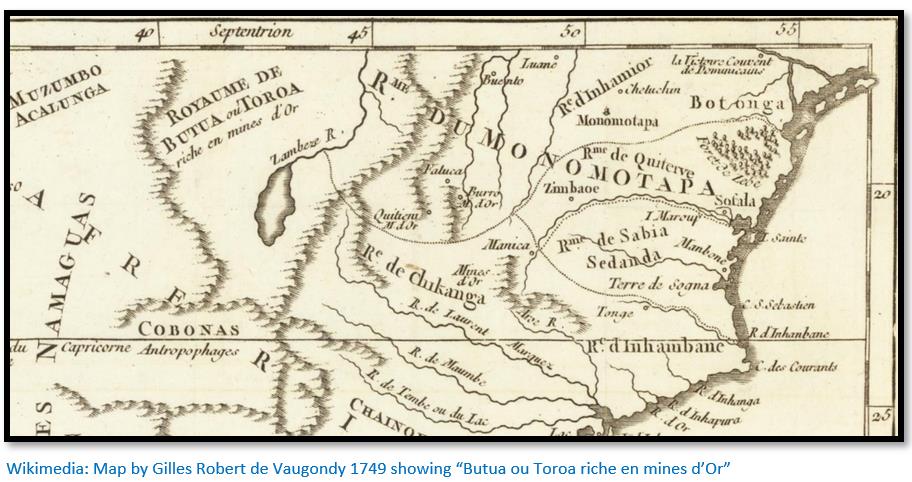

Official expeditions were sent into the interior, such as those undertaken by Antonio Fernandes in 1511-12 and 1513-14 through present-day Manicaland, Mashonaland and into the western goldfields of Abutua in the Midlands. His journeys took him along the wandering paths that connected the small villages in Quiteve, Mocaranga and Abutua and to the trading settlements where Swahili merchants and local Africans had traded gold for centuries.

In 1551 João de Barros wrote in his Decades of Asia a history of the Portuguese in India, Asia and southeast Africa, that the Portuguese were aware of alluvial gold in the Ruenya, Revue, Mutare, Nyadiri, Mazowe, Manyame and Angwa rivers showing that they were familiar with the geography of the northern Mashonaland Plateau. In the 1620’s Father Julio Cesar accompanied the Portuguese ambassador Gaspar Bocarro to the Mutapa Gatsi Rusere’s zimbaoe at Chiromwe. By the time of Gatsi’s death in 1623 – 4, the Portuguese had established settlements - feiras - at Urupande (Hwangwa) and Dambarare.[iv]

Their settlements encouraged “numerous private and unofficial excursions by Portuguese deserters, degredado’s and traders.”[v] Many of these married and or lived in the Portuguese settlements at Tete and Sena and whose children were called mwamamuzingo (i.e. Shona for son of the Portuguese) They spoke the local African language and being part of the local African communities, understood local customs, and often also spoke Portuguese.[vi]

Commerce was accompanied by the Catholic mission for converts

At each of the major feiras the Jesuits established a church with a resident priest, archaeological evidence of churches has been found at Luanze (Ruhanje) and Dambarare. Jesuit Fathers accompanied Francisco Barreto’s military expedition up the Zambesi river in 1569; indeed, Father Francisco de Monclaro authored the report that I have used as the basis for the article. Despite the martyrdom of Father Dom Gonçalo da Silveira, S.J. in 1561 at the zimbaoe of the Mutapa, Chisamharu Negomo, on the Msengezi river they were keen to convert African souls and the place to begin their mission was at the Mutapa’s court.

Their teachings and conversions were a serious threat to the N’angas and svikiros who attended the Mutapa’s court and the Catholic priests were likened by them to muroyi or evil wizards. However despite this, many of the Mutapa’s sons were educated by the church and received christian names.

The unsuccessful Barreto mission to avenge the martyrdom of Father Dom Gonçalo da Silveira

Francisco Barreto’s mission to reach the Mutapa state in 1571 resulted in complete failure despite some limited success on the battlefield against chief Samungazi who led a large Tonga army. The heat and humidity of the Zambesi valley combined with the effect of malaria and dysentery and absence of supplies constantly weakened Barreto’s soldiers and eventually forced them into a shambolic retreat back to Sena.

Vasco Fernandes Homem succeeded Barreto and after refitting the Portuguese forces at Mozambique Island sailed for Sofala in 1574. Despite encountering resistance from chief Sachiteve, Homem managed to capture and hold hostage some of the chief’s family and succeeded in reaching present-day Manicaland by following the Buzi river. Here he was welcomed by the Chikanga and allowed to inspect the fabled gold mines of the region. His engineer, Agostino Sotomayor concluded that that the mines would require capital, men and equipment to be exploited and that local people were better equipped to carry out alluvial panning in the Revue, Ruenya and Mutare rivers. Once again, the Portuguese retreated back to the coast, but at least it was not the ignominious defeat they had suffered in the Zambesi Valley.

Increasingly individual Portuguese traders and their mwamamuzingo travel to the northern Mashonaland Plateau

Despite the Mutapa’s clever use of his vassals and delaying tactics to impose military defeats on the Portuguese expeditions, increasing numbers of traders and their agents, the vashambadzi based themselves at Sofala, Sena and Tete and began intensifying trading visits to the gold producing regions. In the end, Mutapa Negomo Chirisamhuru recognised the inevitable and allowed them to trade and travel freely to the goldfields, providing the customary tribute, the kuruva, was paid.

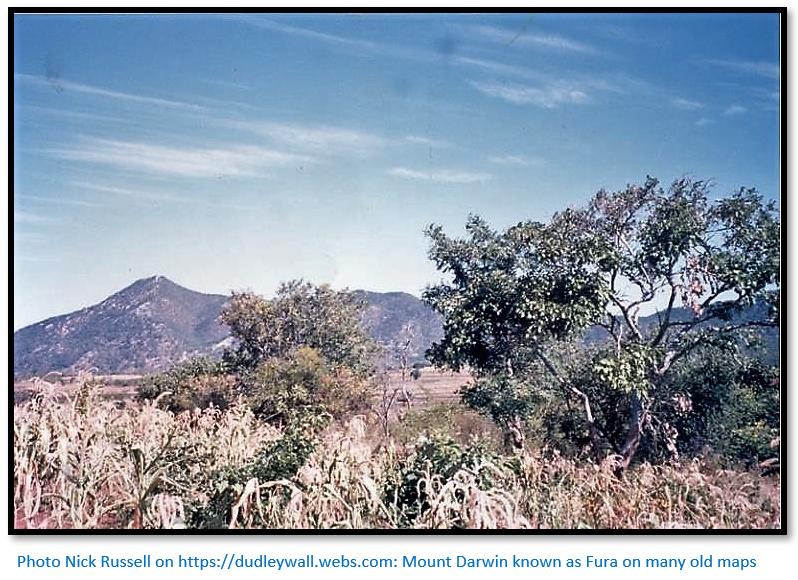

Gradually the customary market places that had long been used by Swahili merchants were selected by official Regimento as feiras and Captains appointed to regulate affairs, liaise with local chiefs and ensure the appropriate taxes were paid by traders. Ellert believes Massapa, known to the Swahili as Aufur, near Mount Darwin was perhaps the oldest and most important of the Portuguese feiras[vii] – although only surveys and limited archaeological work has been carried out at the site and there is little evidence to substantiate this.

Archaeology of the Portuguese feira sites

The late Peter Garlake excavated at many of the located feira sites on the northern Mashonaland Plateau including Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) Massapa and Maramuca (Rimuka)[viii] Elizabeth Goodall carried out a survey of the Portuguese trading settlements on the Angwa river (Ongoe) and in more recent times Innocent Pirikayi has carried out surveys of the Massapa site on Baranda Farm, near Mount Darwin town in northern Mashonaland.

Dambarare – the principal Afro-Portuguese trading site in the 17th Century

The excavations at Dambarare were led by Peter Garlake of the Historical Monuments Commission in 1967 and the results published in 1969 under the title Excavations At The Seventeenth Century Portuguese Site Of Dambarare, Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) Most of the material for this article is based entirely on this report, supplemented by material from Henrik Ellert’s excellent book Rivers of Gold.

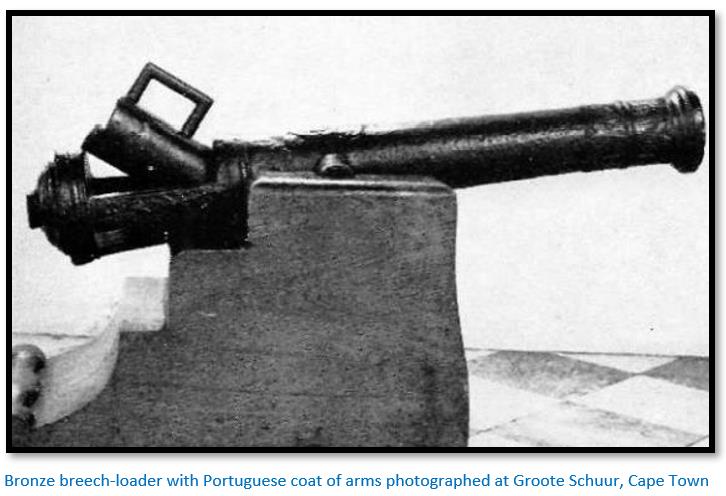

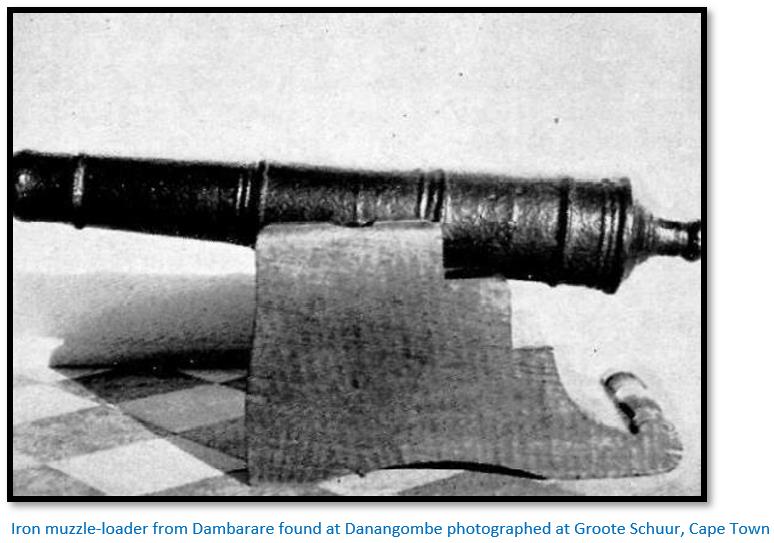

In 1684, when Caetano de Melo de Castro was Governor of Mozambique, Dambarare was chosen to become the centre for the reassertion of Portuguese influence, with the establishment of a garrison and the erection of a new fort. There were plans to reinforce the garrison with bronze artillery pieces, but only two small guns were delivered. These are very probably the two small cannon, a bronze breech-loader with the Portuguese coat of arms and an iron muzzle-loader found at Danangombe (formerly Dhlo-Dhlo) along with a considerable quantity of silver ecclesiastical items[ix] used by the Jesuits and brought here after the sacking of Dambarare as Rozvi loot.

"The feira of Dambarare was acclaimed the best of all the feiras in the Rivers of Sena, where almost all the rich influential merchants of Sena traded and thence scattered to other places such as Chitomborwizi, Rimuka, Luanze and Matafuna. Dambarare was the headquarters, second only to the administrative headquarters of the Captain of the Gates at Masapa."[x]

Dambarare as quoted in some of the Portuguese records

Garlake states that in 1631 Dambarare was listed as a fair with a church served by a Jesuit priest,[xi] one of the earliest mentions of the site by name.[xii]

In 1634 Pedro Barreto de Rezende in the Do Estado da India, states “Farther in the lands of Mocaranga (than the fort of Luanze) is the fort of Ambarare where there is a market. In this part they dig for gold, and there are gold mines.”[xiii]

In 1635, Diogo de Sousa de Menezes, a former Captain of Mozambique, speaks of the alluvial gold in “the river Manzovo[xiv]….which runs from Dambarare, and reaches the river Ruenya”

By 1667 Manoel Barreto wrote: “Dambarari is a noble settlement and good sized town in the heart of Mokaranga and has grown to be the centre of the conquest, with many rich inhabitants….”, one of the four “principal places where gold is obtained.”[xv]

In the 1680’s the Caetano de Melo de Castro,[xvi] then Captain of Mozambique, appointed Francisco do Valle as the Captain at Dambarare to strengthen the defences in the same way that he appointed João de Sigueira in 1684 to strengthen the Angwa (Ongoe) feira defences by adding bastions.

Writing fourteen years later in 1698 de Almeida y Sousa described Dambarare: “The site of the fort constructed in the time of Caetano de Melo De Castro is on a terrace from which the entire surrounding plain was visible and where there was a most plentiful river, with excellent water flowing the whole year, called the Marauoza, [xvii]a stone’s throw from the fort…”[xviii]

Antonio de Conceição, writing at a later date: “At Dambarare we used to have a fair with its earthworks…but within there was nothing more than the Church with its Vicar and the Captain; the rest lived in the vicinity at some distance from one another…”[xix]

Other early indications of the existence of Dambarare

From the Portuguese contemporary sources quoted above it has long been known that the site of Dambarare must be near the headwaters of the Mazowe river. The archaeologist J.T. Bent visited the upper Mazoe Valley in 1891 after completing investigations at Great Zimbabwe.[xx] He was very aware of the early Portuguese presence along the Mazowe river writing: “Further evidence of this Portuguese enterprise in Rhodesia will doubtless come to light as the Mazoe Valley is more fully explored. In the vicinity of a new mine called the Jumbo, fragments of old Delft pottery have been found, a few of which were shown to me when at Fort Salisbury. Nankin china is also reported from the same district, an indubitable proof of Portuguese presence…”

However since 1923 the site had been ridged, ploughed and cultivated over many years, which had flattened the mound and the presence of very large termite mounds in the immediate vicinity made its recognition still more uncertain; but it was still identified after forty years and it was here that the present excavations were undertaken.

Garlake states that in the vicinity of Dambarare there were the ruins of several old prospectors’ abodes and mixed with the household rubbish of sixty to eighty years ago, fragments of much earlier Chinese porcelain were frequently found.

During 1944 - 1945, Mrs Elizabeth Goodall collected imported ceramics from the surface of the present site and in its immediate vicinity. In 1961 D.P. Abraham,[xxi] working from documentary and traditional sources, also identified an earthwork immediately north of the present site as being an early Portuguese structure.

Garlake writes that amongst the early prospectors in the upper Mazoe Valley was a clear awareness of earlier European occupation. In December 1966 Mr H. Light[xxii] took Garlake to a large mound which, in 1923, he had recognised to be the remnants of a building and near which he had unearthed a human burial.

Site of Dambarare

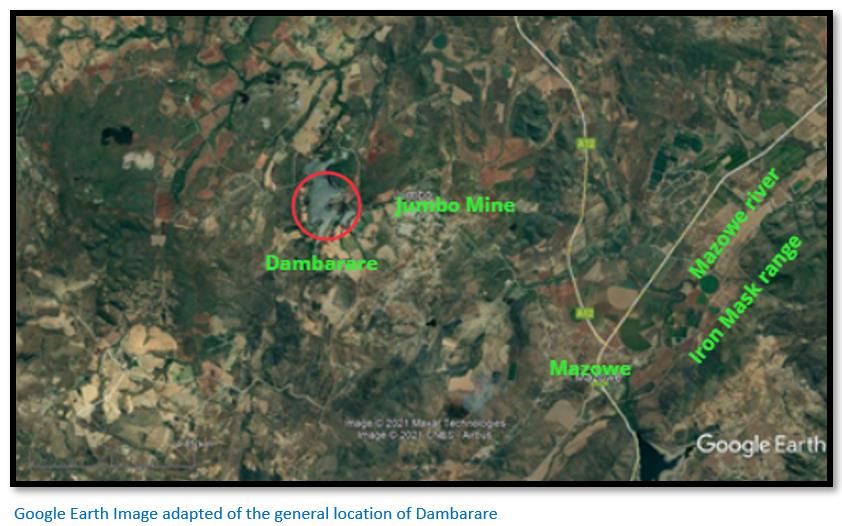

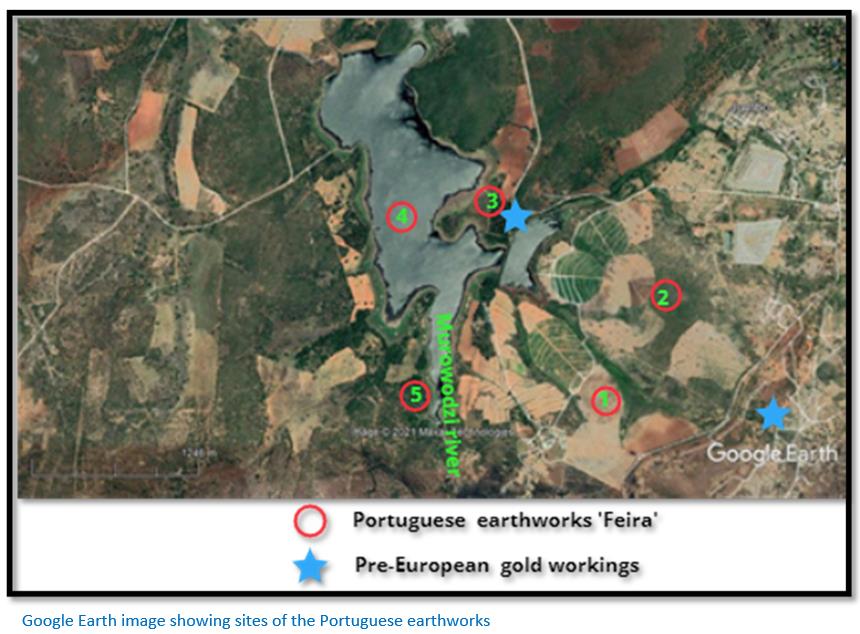

The GPS location for the general site is 17°28´34" S 30°54´02" E and on the banks of the Marodzi (or Murowodzi) river which has been dammed at this point to form the Jumbo Mine dam and the Jumbo Mine itself is just 3 km to the east. The river although small is perennial and like all the rivers in the area drains into the Mazowe river flowing north-east.

Physical description of the Portuguese earthworks

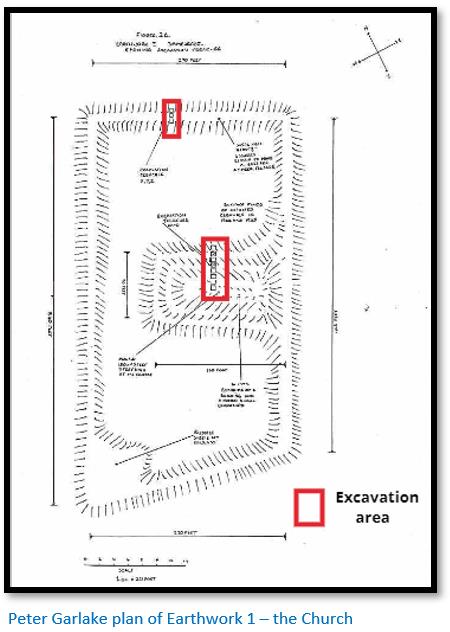

Earthwork 1 as indicated on the Google Earth image below is at the southern end of Jumbo Mine dam and on its eastern bank and is the largest of the four remaining earthworks. It consists of a mound, 180ft (55m) long, 90ft (27m) wide and 7ft (2m) high at its centre, running almost due east-west. The remains of an enclosing bank were visible as a darkening of the ploughed soil north of the mound. An infra-red aerial photograph clearly highlighted the mound and enclosure. The mound itself divides the enclosure, its western end being irregular in shape, indicating minor buildings are present and there is a second, smaller mound in the southern half of the enclosure from the west bank.

The enclosure consists of four straight earth banks, 465ft (142m) on the east, 540ft (165m) on the west and 270 ft (82m) wide.

A cemetery was partially excavated which indicated numerous burials. Within the earthwork surface finds of Chinese and Portuguese ceramics were found.

Earthwork 2 is approximately 1 km to the north east at the edge of cultivated lands on a small, isolated granite kopje and shows traces of earthwork banks forming a rectangle around the summit. It is partly destroyed by a small brick house probably built in the 19th Century.

Earthwork 3 is approximately 1.3 km to the north west and consists of a rectangle of earthwork banks partly faced in stone within which is a large mound. Garlake believed this was the site identified by Abraham in 1961.

Earthwork 4 was almost 1.1 km due west of Earthwork 3 and was described by Garlake: “on level ground immediately above the steep banks of the Marodzi, lies a further well preserved rectangular earthwork, with outworks beyond its north-west corner. Traces of pole and daga huts are visible in the shallow, stony soil of the interior as being but is now covered by the waters of the Jumbo Mine dam.”

Earthwork 4 was probably the garrison for Dambarare as Almeida y Sousa describes it as being located on a terrace which commanded a splendid view of the surrounding countryside which had plentiful water year round and the Murowodzi river just a stone’s throw away from the fort. In 1698 Father Filipe de Assumpção wrote that Dambarare fort, prior to its destruction five years earlier, was built of mud and wooden walls by the Murowodzi river and with a moat. He reported the two small artillery cannon, but there was no garrison at the time he visited and the fort looked neglected.

A possible Earthwork 5 is described where: “the Marodzi river flows in a large bend round the foot of a commanding spur on its western bank. Here, further sherds of Chinese porcelain were recovered among the vestiges of daga floors but no earthworks were recognised.” This is on the western bank of the Jumbo Mine dam less than 1 km west of earthwork 1.

The outline of Jumbo Mine dam on the map drawn by Garlake and the Google Earth image differ – this may be due to the dam wall being raised subsequent to Garlake’s survey.

All the above earthwork sites yielded numerous sherds of seventeenth century Chinese ceramics, and all are closely similar in plan and structure. All, moreover, are visible one from another.

Evidence of local gold working

Garlake writes that the Marodzi river contains small quantities of alluvial gold – the Mazowe river and tributaries have been sources of alluvial gold for many centuries. He states there is evidence of pre-European gold workings[xxiii] in the form of 60ft (18m) shafts immediately below Earthwork 4 which still contained gold reef averaging 74.5 dwt.[xxiv]

He describes further pre-European gold workings 1.5 km south east of earthwork 1: “with very regularly cut galleries with arched roofs, quite uncharacteristic of “ancient” mining techniques. These may well have been excavated under Portuguese direction. They do not appear, however, to have struck a gold reef; iron ore may have been extracted.” These are National Monument No 45 “Jumbo ancient workings” to the east of the road from Jumbo Mine but are, in all likelihood, now destroyed by artisanal miners.

Roger Summers under Area 6 - Jumbo Mine[xxv] lists 41 pre-European workings in this small area, many of which already had open stopes and shafts when the claims were registered. 7 of these mines produced between 5,000 – 10,000 oz (142 – 284 kgs) of gold between 1890 and 1960.

Evidence of an earlier excavation at Earthwork 1

Evidence was seen during the excavation that a trench 6ft (1.8m) deep and averaging 2ft. (0.6m) wide had been dug running east-west across a section of the site and then filled in immediately after it was dug. Garlake believed it was the work of a late 19th Century or later prospector or treasure hunter attracted by the obvious age or alien origin of the mound. Fortunately, little damage was done, for the main burial levels were not reached.

The Historical Monuments Commission excavation carried out at Earthwork 1

The excavation of the central mound of the largest earthwork was conducted for two weeks by the History Department of the University College of Rhodesia and throughout September and October 1967 (i.e. a period of eleven weeks) by the 1967 Ranche House School of Archaeology and volunteers.

A line of trenches, each 6ft by 6ft (1.8m) separated by 2ft (0.6m) intervals was laid across the width of the site through the centre of the central mound. Further trenches of the same size were cut through the northern earth bank.

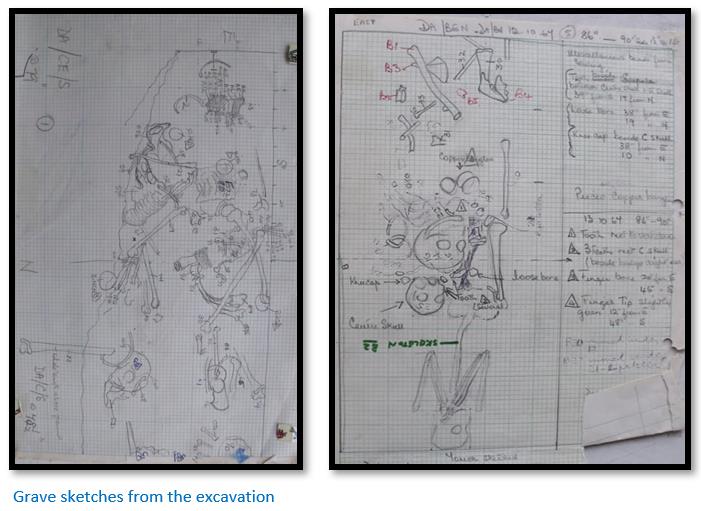

Each soil stratum was excavated separately where possible in 4in (10cm) horizontal spits and any finds or bones photographed before removal. All skeletons were drawn and photographed before removal; only one burial was removed en bloc. All deposits were sieved to ensure no beads and other material were missed.

The excavation revealed the building under the mound was originally built of red bricks and although levelled to the ground, there was no evidence that its destruction was violent or accidental through fire, etc. It appeared from the evidence that eight burials took place soon after the destruction of the first buildings.

Renewed building activity then began and a floor was laid over the red rubble layer and the graves and a second major building was erected using larger and thinner sun-dried bricks that are mainly sandy in texture and of various colours: buff, grey, yellow and chocolate. Further alterations and additions to the main building were later carried out to the building with thicker floors being added and additions to the building before it was finally abandoned.

Trenches dug into the northern enclosure wall revealed a trench 2ft. 8in. (0.85m) wide and extending 2ft. 3in. (0.7m) below the present ground level with a course of bricks, identical to those used in the walls of the building, laid in a grey-clay mortar across the entire base of the trench. These were covered by a 6in. (0.15m) layer of mottled red and grey clay. A further course of bricks were laid and covered in turn by a further layer of clay, reaching to within 3in. of the present surface. The alternate brick and clay courses represent the foundations of the outer wall.

Garlake believed these probably formed the base of a timber fence and core of a small earth bank but they cannot have been of any height as there is no sign of any building debris in the proximity.

Garlake’s excavations detected no signs of violent destruction and the evidence showed the building disintegrated through natural processes. Large fragments of fallen brickwork marked the most rapid stage of the collapse of the building as the main walls fractured and collapsed. After disintegration proceeded more slowly during which the site was completely unoccupied.

Readers who wish further details of the excavation methodology should read the original article Excavations At The Seventeenth Century Portuguese Site Of Dambarare, Rhodesia.

Construction material used in the building of Earthwork 1

The bricks of the underlying buildings were dark red clay with quartzite and grey clay inclusions. There were no red bricks used in the second building which was constructed of larger and thinner sun-dried bricks, predominantly sandy in texture and of various colours: buff, grey, yellow and chocolate. The buff bricks formed about 50% of the bricks used, grey bricks 35%, yellow 10% and chocolate 5% and all were sun-dried.

Soils of colours matching the various bricks can be seen within a quarter of a mile (400m) of the building. The bricks were set in a chocolate brown clay mortar. Large quantities of mortar were also used to compensate not only for the irregular sizes and breakages of the bricks but also for the bad positioning of many bricks which were frequently laid at an angle to the general line of the wall.

The main wall was 2ft. 11in. (90cm) i.e. one and half brick lengths, thick. The gap in the centre of the wall was filled with a brick rubble packing and large quantities of mortar.

Garlake states the quality of the fabric and construction of the walls was poor. However this was compensated by the size of the bricks and the thickness of the walls, which were quite capable of standing for a considerable length and height unsupported by cross walls and of carrying a roof of large span.

The foundations of the north-south wall of the main building consisted of three courses of brickwork, 3ft. 10½in. (116cm) i.e. two brick lengths thick, the bond following that of the superstructure. The foundations of the east-west wall were not thickened and appear to have been only two courses deep. This wall, however, rested on the earlier red brick wall, whereas the north-south wall ran across clays and grave fills.

The finished surface of the walls consisted of a clay mortar ½ in. thick, covered in a fine, pure white wash.

The floors were all of thin, pure coloured clay, some ½ in. to 1in. (1.27 - 2.5cm) thick, laid directly over natural silt, clay, gravel or brick rubble; in some cases sealing the grave shafts. In places the floors were renewed up to nine times, with clays of black, brown, red, grey and white colour, each no more than 1/8in. (0.32cm) thick.

There was no trace of stone or woodwork in the buildings – though none of the roof structure survives and was presumably made of timber. Several iron nails were found in occupation deposits outside the building and are contemporary with its erection.

Garlake concludes that both the earlier and later buildings at Earthwork 1 were Churches

From the scale of building and the continuous association of burials with the structures, Garlake believes it is safe to assume that both buildings were churches.

The first building with red brick walls had a subsidiary building with walls 7ft. 3in. (2.2m) apart and the area between them is almost entirely filled by a single grave. These walls run east-south-east to west-north-west at an angle of 10° to the line of the later church.

The burials

Thirty-one burials were excavated, though not all the bones of every skeleton were recovered. Burials took place throughout the history of the site and can be divided into four stratigraphic and temporal groups:

- Those that took place before the erection or early in the occupation of the first church (five burials)

- Those interred immediately beneath the floors of the first church (seventeen burials)

- Those interred after the demolition of the first church and before the erection of the second (seven burials)

- Two skeletons lying in and on the occupation level associated with the last church.

From the burials it appears that the Portuguese inhabitants, exclusively adult males, many of whom had barely reached maturity, were usually buried within the church.

The African burials, interred outside but in close proximity to the church, were almost certainly people of considerable economic and social status, who may well have belonged to the ruling group. Although they had abandoned indigenous burial customs and been buried as Christians, their ornaments are those worn by contemporary indigenous inhabitants. One young girl wore metal anklets on each leg reaching between 4 and 4¼lb (1.8 – 1.9kg) Similar ornaments in burials have been found at Khami, Danangombe (Dhlo Dhlo) Great Zimbabwe: Randall-Maclver, 1906; Chibvumani, Matendere, Great Zimbabwe: Caton-Thompson, 1931; Khami; Robinson, 1959.

The undisturbed skeletons lie extended full length with their arms crossed on the chest or their hands clasped at the waist or, in two cases, clasped against the head. They clearly follow Christian and not indigenous African practice as all orientated almost exactly east-west. Twenty-one of the bodies had their heads to the west, four had their heads to the east (the bones of the remaining six skeletons were scattered)

The burials were extremely crowded but organised as seventeen undisturbed or partially disturbed adult burials (from all strata) had either heads or toes within 6in. (15cm) of the west face of the line of the trenches and extended east. Only six adult burials departed from this.

The grave depths varied very little from a maximum of 3ft. 6in. (107cm) to a minimum of 2ft. 9in. (84cm) They all had sloping sides, all but one being some 1ft. 10in. wide at the centre and narrower at the ends, very little larger than the body they contained and no coffins were used. The bodies of the indigenous females were wrapped in cotton shrouds, traces of which were preserved wherever they were in contact with copper.

All the bodies were buried in individual graves, with the possible exception of the bodies in the large grave between the walls of the first church where a male and a female may have been buried together. The burials were not marked by headstones most being sealed under the floors. Twelve of the graves had been disturbed or destroyed by later burials, in five burials the later body was laid immediately on top of an earlier burial and five other burials were completed destroyed by three later burials. In each case the bones were scattered haphazardly over the later body.

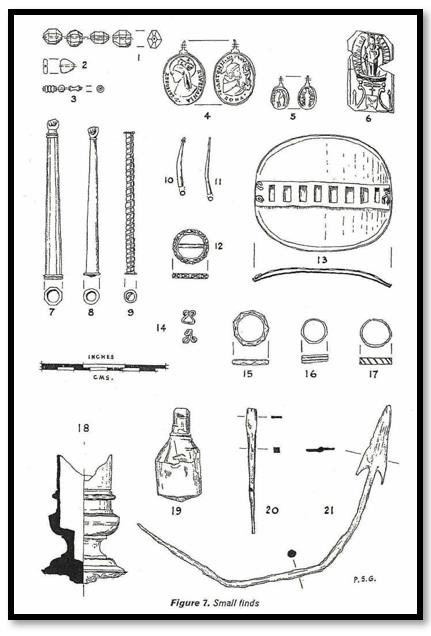

Of the thirty-one burials excavated, fifteen were within the church, of which nine were identified as males and five wore gold rings and bronze and silver medallions, aiguillettes, pins or buckles.

The other fourteen burials were outside the church, five were females, five were males, there were three infants and one unidentified. Only one male had grave outside the church had grave goods, a simple decorated tablet of clay.

Garlake believed some social and possibly religious distinction was visible in the burials. The men were buried within the church in the normal Christian manner with grave goods. He suspected that men, women, children of a lower status were buried outside the church and the fact that all but one of the bodies buried outside the church had their arms uncrossed may indicate they were possibly catechumens (i.e. receiving instruction in preparation for Christian baptism or confirmation) rather than communicants.

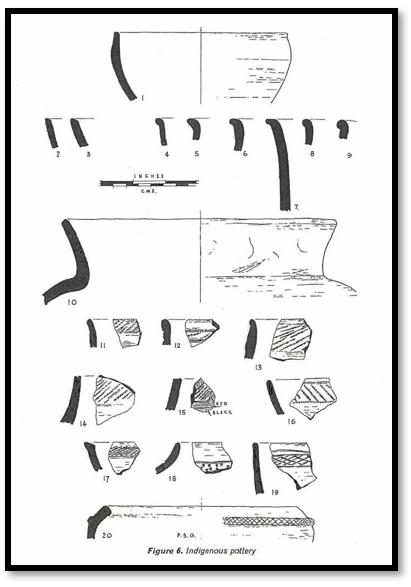

Indigenous Pottery

655 sherds of indigenous pottery were recovered. Practically all were very fragmentary and the information they yielded disappointing; 50% of the sherds were brown or buff, 18% grey or dark grey, 14% jet-black and 10% a well-fired red; the remaining 8% were graphited.

Garlake thought the significance of the surface finds was questionable. 43% of the excavated sherds come from the original ground surface, 35% from the fill of graves, the remaining 22% were scattered sparsely but uniformly throughout the deposits: in wall fabrics (4%) wall debris (14%) or topsoil (3%) and not a single sherd rested on or associated with any floor.

Garlake, who also excavated Luanze, a contemporary Portuguese trading post in north-eastern Mashonaland, thought the pottery from both sites was very similar. Both sites were characterised by simple vessel forms, simple or slightly beaded rims, poor firing and infrequent use of burnishing or graphite burnishing. There was little pottery decoration, but where it occurred, comb-stamping was the dominant motif and the general appearance of the indigenous pottery from Dambarare and Luanze, in burnishing, fabric, rim forms and rarity of decoration, compared with Shona pottery of the recent past.

Cloth

Cloth imported from India would have been a major Portuguese import item for trade along with beads but decayed quickly. Ellert states that it is nearly all manufactured in the Cambaya region of Gujarati province in western India. From Cambaya the cloth was sent to the ports of Diu and Goa. Bertangil Vermelho, a red heavy cotton cloth, was a popular trade item in Africa.

Imported ceramics

As stated above, Mrs Goodall in 1944-45 collected from this site what is the biggest collection of imported sherds of the Portuguese period in the country. A representative selection of these sherds was examined by J.S. Kirkman and correlated with his finds from Portuguese levels at Fort Jesus, Mombasa.

The complete collection of 3,182 sherds was classified as follows:

(1) Porcelain, blue and white glaze. Chinese, Wanli period of the Ming dynasty, late sixteenth to early seventeenth century (Luanze, Class 1). Flat dishes, decorated in panels, are a feature of both the Dambarare and Luanze assemblages. 44%

(2) Porcelain: blue and white glaze. Chinese, Transitional period, mid-seventeenth century. 6%

(3) Porcelain: interior blue and white glaze, exterior chocolate glaze. Chinese, K’ang Hsi period, late seventeenth to early eighteenth century. 3.5%

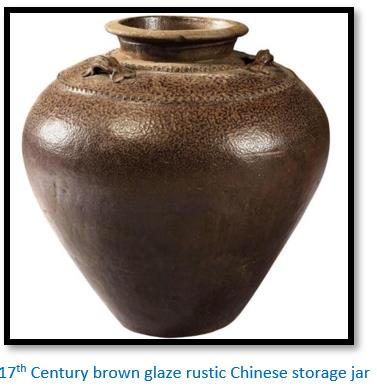

(4) Stoneware, thick grey body: exterior black, brown, mustard or olive glaze; interior black or olive glaze, brown wash or unglazed. Chinese storage jars, sixteenth to seventeenth centuries. 21.5%

(5) Stoneware, very thick grey body; unglazed or poor, mottled, black to olive partial glaze. Chinese storage jars, late seventeenth century. 1.5%

(6) Stoneware; exterior green to yellow glazed, with trailed floral decoration; interior black glaze, brown wash or unglazed. Chinese storage jars, seventeenth century (Luanze, Class 2). 1.5%

(7) Earthenware, white, grey or pink body; white glaze with designs in bright blue or blue outlined in black design. Persian imitations of Chinese porcelain, late seventeenth century. 4.5%

(8) Earthenware, thick buff body; exterior poor partial white glaze; interior white glaze with designs in turquoise; probably Persian, late seventeenth century. 0.5%

(9) Earthenware, thick, pale buff body; exterior transparent purple, turquoise or green glaze; interior clear glaze or unglazed. Persian Jars, seventeenth or eighteenth centuries. 1%

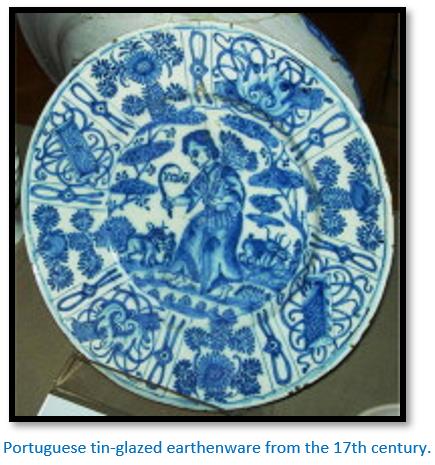

(10) Earthenware, white body; bright blue and white glaze. Portuguese imitation of Chinese porcelain, middle to late seventeenth century (Luanze, Class 8) 8.5%

(11) Earthenware, white body; purple, blue and white glaze. Portuguese, middle to late seventeenth century. 1%

(12) Earthenware, white body; plain white glaze. Portuguese, middle to late seventeenth century. 3%

(13) Terracotta, thick body; poor yellow-green to olive glaze. Probably European, seventeenth century. (Luanze, Classes 4 and 5) 1%

(14) Terracotta; unglazed or poor clear to brown glaze to interior only. Probably European, seventeenth century (Luanze, Class 3) 1.5%

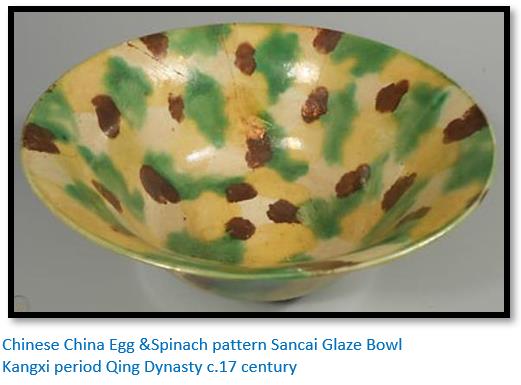

(15) Miscellaneous: Chinese “egg and spinach” porcelain; terracotta’s with exterior grey-blue and black mottled glazes; orange glazed and Blanc de Chine porcelains; Chinese olive glazed earthenware with white trailed decoration. All late seventeenth century. 1%

Of the imported ceramics, 79% originate from China, 6% from Persia and 15% from Europe. 44% of the ceramics were manufactured in the late 16 – early 17th Century, 18.5% in the middle 17th Century, 11% in the late 17th Century and 26.5% are of types manufactured at least throughout the 17th Century.

The stratified imported ceramics are typical of a 17th Century Portuguese site, closely comparable to the assemblages from Luanze (Garlake, 1967) and the earlier 17th Century Portuguese levels at Fort Jesus, Mombasa (J.S. Kirkman, pers. comm.) Kirkman divided the ceramics from the excavations of the Portuguese deposits at Fort Jesus, Mombasa, into two periods, 1593 - c.1632 and c.1632 - 1698 (Kirkman, 1967)

The first period contains late Ming and Transitional Chinese porcelains and blue and white Portuguese earthenware’s – all found at Dambarare; but only a few ceramics were found of the second period. The Dambarare ceramics indicate they were imported after 1632, but not as late as 1698.

The commoner glazed ceramics and trade beads imported by the Portuguese during the seventeenth century that occur at Dambarare are closely related to finds from Khami and Danangombe (Dhlo Dhlo)

Glass and Shell Beads

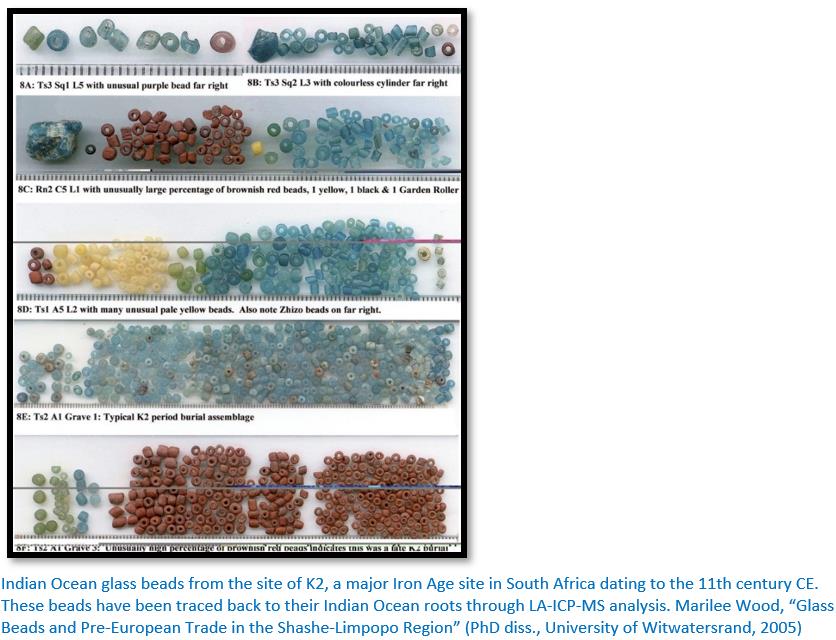

Group 1 Beads are small discs from 3-6mm in diameter with a constant bore diameter of 1.7mm. When strung, thirty-six beads cover 3cm.

Group 2 Beads are reheated glass canes: opaque oblates and cylinders from 2-4mm in diameter and 1.5-4mm in length. The colours tend to be dull and the shapes irregular. No bead in this group shows a patina. These beads are the normal 17th Century Portuguese trade beads and are identical to excavated beads from Luanze, Great Zimbabwe, or later

Khami series.

Group 3 Beads are reheated glass canes: small oblates, 2.5-3mm in diameter and 1.5mm long, transparent or translucent in colour. They are smaller and much more regular in shape than the beads of Group 2. The colours are bright and pure, light blue and a plum so dark as to appear black completely domination the assemblage. Decay makes the beads porous with a thick white patina completely obscuring the original colour. They were obtained from pre-Portuguese East African traders of the 12th – 15th Centuries and found at Mapela, Great Zimbabwe and Mapungubwe.

Group 4 Beads are a miscellany

- Glass beads, moulded to form hexagonal prisms 8-10mm across and 10mm long, tabular heart-shaped beads, moulded in translucent green glass, 7mm long, 9mm wide and 2mm thick, bored vertically through the centre and tiny oblates, of opaque Indian red or transparent plum glass, identical in colour and fabric to the beads of these types in Group 3 but so small, 1mm in diameter and 0.5mm long, as to be barely visible to the naked eye.

- Coral beads, pale pink in colour, frequently with a blotchy white patina; they are either spherical in shape, 5-7mm in diameter, or barrel-shaped cylinders, 2.5mm in diameter and 4-5mm in length.

- Ivory beads, both spheres, 4mm in diameter and segmented cylinders, 5mm in diameter and 8mm long formed a “rosary” hanging from a bead girdle in a burial.

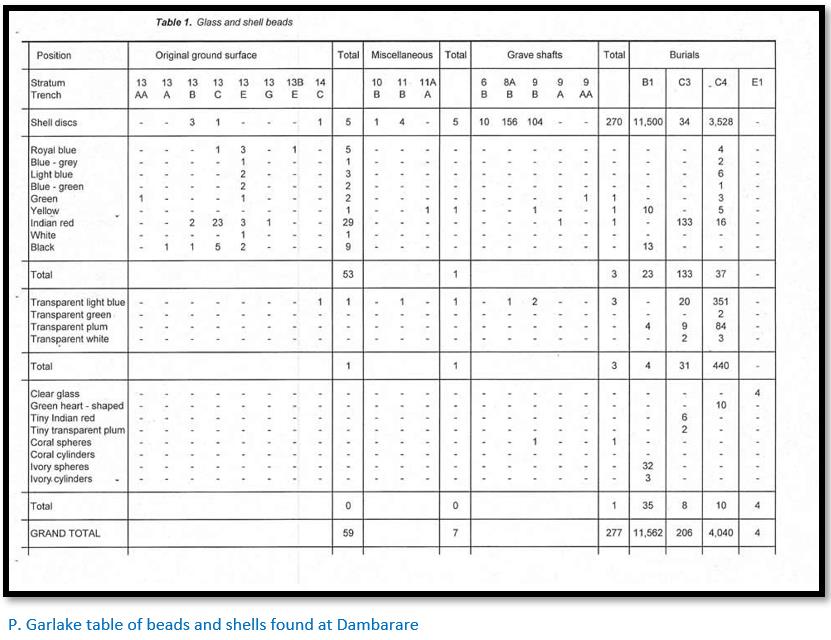

The table below shows in stratum 13 the original ground surface of the site, the normal bead losses or discards of the occupants of the site before it assumed any specialised function or importance. The vast majority of finds were shell beads found within the burials and the numbers of trade beads were comparatively small.

Glass and shell beads were worn by two females (B1 and C4) by a male (E1) and by one infant (C3) The intact strings and portions of strings of beads show how the beads were arranged with shell beads formed the major component of the strings with rare spacers of glass, coral or metal. The pelvic girdle of Burial B1 consisted of twelve strings of shell beads broken by four small groups of glass beads and four single glass beads as spacers.

The male, Burial E1, wore a single strand necklace of copper beads with four large, moulded glass beads placed together at the front. Burial C3, an infant, appears to have worn a necklace of transparent light blue and minute Indian red and plum beads and also a single compact group, 1in square, of Indian red trade beads, sewn to a cap or threaded in the hair.

Bead values in the 16 – 17th Centuries

Garlake writes that due to the unpopularity of Portuguese imported beads, caracoes (“snail stone beads”) became the main item of local barter at Sofala between 1516 - 1518. Being locally manufactured, they were exempt from the Royal monopoly over the bead trade and in volume, over seven times more of these beads were traded than all forms of imported beads. The caracoes correspond to the shell discs in the above table. They sold at a price of one mitical of gold for one faraçola[xxvi] (varies between 8.3kg – 10.4kg) of beads.

The normal Portuguese trade beads, contas meudas (“small beads”) in black, green, blue and yellow – cost 24 - 30 miticals of gold per faraçola

The greatest demand was for contas de Cambaya (“Cambay beads”) which were made in red and black and worth 40 - 75 miticals of gold per faraçola

The smaller the beads the greater the demand and the higher the cost. A variety of European beads of coral, crystal, pewter, jet, amber and blue Venetian glass, all larger than those described, were also imported. They formed only a small proportion of the stock, were not priced and proved impossible to trade.

In an excellent article on beads found at Khubu la Dintša in Botswana[xxvii] Carla Klehm outlines the importance of beads in the Indian Ocean trade network: “Portuguese merchants became involved in this Indian Ocean trade in the 15th century CE and quickly noted the high trade value placed on glass beads. And their African trade partners were specific about their point of origin: only glass beads originating from the Indian Ocean were considered proper currency. European glass beads were considered unacceptable. Therefore, Portuguese traders would travel all the way to ports in India in order to obtain beads for African trade.”

Carla Klehm notes that George McCall Theal, translated many Portuguese documents and gives some examples of references to Indian Ocean glass beads:

1513: The merchants take to Sofala gold which they give to the Moors without weighing for coloured cloths and beads which among them are much valued, which beads come from Cambaya.

1554: Among them was one of whom the rest seemed to make the most account … he was distinguished from them by wearing a few beads red in colour, round, and about the same size as coriander seeds, which we rejoiced to see, it seeming to us that these beads being in his possession proved that we were near some river frequented by trading vessels, for they are only made in the kingdom of Cambaya and are brought by the hands of our people to this coast.

Klehm writes: “These Portuguese traders describe how glass beads played a large role in the exchange of African trade goods, especially gold. Noted in multiple accounts was the port of Cambay (present day Khambat) in southwest India, one of several centres for glass bead manufacturing.”

Metal Beads and Bangles

Copper or bronze bangles, bracelets, anklets or necklaces were worn by all the adult indigenous burials excavated, four women and a man, but were not found on any other body.

Copper or bronze wire, with a square or rectangular cross-section 0.2-0.5mm thick, was wound to form coils from 1-3.5mm in diameter, occasionally in the examples, over a fibre core. Most frequently the coils were 2-2.5mm. in larger diameter with from 14-20 coils per person.

A thicker wire, 1.2mm wide with a semi-circular cross-section, was used to make bangles, wound in a coil 3mm in diameter with seven or eight turns to 1cm. The bangles were from 58-62mm in diameter. The curved face of the wire was always turned towards the outer perimeter of the bangle. Such bangles are common, burial C4 wore at least 45.

Copper or bronze beads were most commonly formed by clipping a short length of wire over a fibre core, leaving the ends butt-jointed. They vary from 1-2mm in width, from paper thinness to 1mm thick and from 2-4mm in diameter. The larger beads were commonly used to form bracelets, the beads being clipped firmly and continuously over a fibre core, always with the butt ends facing inwards and the curved face of the wire outwards so that the bracelets look very like the wire bangles just described. Such bracelets, of which nineteen were found, contain from 80 to 126 beads. In five instances, these beads were clipped over lengths of coiled wire, at regular intervals, usually 5mm apart, so form more ornate bracelets, each with some 45 beads. Groups of from 12 to 36 of these beads also occur together, strung with shell beads.

Cast copper or bronze beads were much rarer. Bi-cones, 2mm wide and 3.5mm in diameter, were strung at 4mm intervals on coiled wire cores in eight bracelets. In one such bracelet, three strands of coiled wire are twisted together to form the core of the bracelet.

The arms of one burial (C4) were adorned with 45 bangles interspersed with at least 104 coils of wire, the metalwork on each arm weighting 1lb (454 gm) Burial B4 wore 36 bangles and bracelets of various types, interspersed with at least 68 coils of wire, the metalwork on each arm weighing between 1lb and 1¼lb (454 – 567 gm) Necklaces were not worn by any female. The one male (E1), however, wore a necklace of small copper beads with four large clear glass beads at the front, and coiled wire bangles on the right arm, below the right knee and at the left ankle. The female burials B1 and C4 wore a great number of wire ankles. From 80 to at least 112 coils of wire (Class A) encased the legs for up to 23cm. from ankle to mid-calf, the weight of anklets on each leg reaching between 4 and 4¼lb (1.8 – 1.9 kg)

Metal Ornaments

At least ten Portuguese men were buried at various times within the church itself. Almost everything except the bones had perished, but on six bodies copper, bronze, silver and gold metal ornaments have survived.

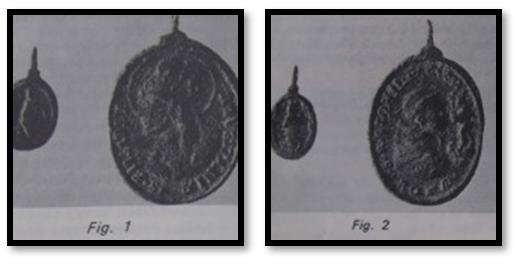

Around the neck of one man was a gilded bronze medallion. On one side is the profile of a female head wearing a crown and encircled by a halo with the inscription S. ELISABET R. LUSITANIA. On the other side is the bust of a cloaked, tonsured and haloed man in profile contemplating a figure of the Christ Child standing on a pedestal. (Fig 1) Another has the inscription S. ANTONII.-V with ROMA (Fig 2) These represent Elizabeth, 1271-1330. The medallion must have been struck after Elizabeth’s canonisation in 1625 and the abandonment of Dambarare in 1693.

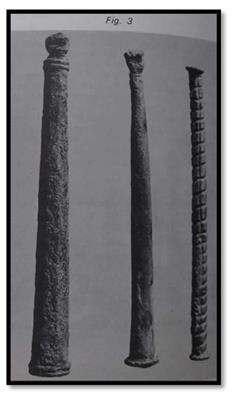

Resting on the pelvis of the same body was a hollow, tapered, cylindrical bronze rod with eight facets, with a small clenched right fist at its tip. (Fig 3 left) The interior is partly filled with red wax. This is an aiguillette – an item of 17th century male dress which formed the ornamental end of a cord tying together portions of armour, or doublets and hose. Also found on this body was a gold ring, found on the little finger of the left hand, decorated with two horizontal grooves.

Aiguillettes were found at the hips of the other two men. One of silver, is grooved spirally round its entire surface with four vertical flutes and has a beaded rim at each end (Fig 3 right) It contains a small bar across the interior of one end for the attachment of the cord. The other is again a tapered cylinder of bronze with a clenched fist at its tip and red wax in the interior. (Fig 3 centre) In the latter burial, the plain bronze casing of what was presumably a bone or wood pin, lay close to the aiguillette. It forms a hollow, tapered cylinder, 35mm long and 2.5mm wide at the base.

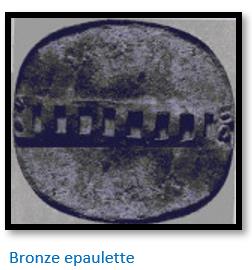

A fourth man had at his waist a small silver buckle engraved with a series of ten Maltese crosses or four leafed rosettes within oval frames. A bronze epaulette rested near his left shoulder: this is a thin, copper plate curved to the shape of the shoulder with a latticed strip on the outer face, through which a strap, 10 mm wide, almost the same as that of the buckle, was presumably laced. He also had a tiny copper pin at his chin and the silver casing of a further pin, 29 mm long and 3 mm wide at its base with a tiny ball decorating the tip was found on his breast. Two further bodies were found wearing gold finger rings: one a plain circle, the other bearing nine diamond shaped facets round its exterior face.

Immediately outside the church, women and children were buried. The women were heavily adorned with copper and bronze bracelets and anklets. One also wore a splendid girdle of shell and glass beads and hanging from this was a rosary of small carved ivory beads and attached to them, a tiny, heavily worn bronze medal. It bears on one side a full length female figure, possibly with a halo, standing beside an unidentified object and an inscription which appears to read G. EATIS. The other side bears a barely distinguishable figure standing on a crescent moon, surrounded by rays and probably crowned, presumably representing the assumption of the Virgin.

A young female burial wore five copper rings, all 17mm in diameter, one of which is unevenly facetted and another fluted. Two of these have the ends simply butted. A male burial wore a copper ring, 4mm wide and 18mm in diameter, crudely engraved with a series of oblique lines and the ends butt-jointed, on the fourth digit of the right hand.

Clay tablet

In the same area just outside the church, three Portuguese men had also been buried. There was nothing with them except a rectangular tablet of fine clay found beside the right upper arm of one man. This bears an impression of the Virgin in glory, crowned, holding the Christ Child and standing on a crescent moon and clouds. Below is an armorial shield, apparently bearing only a single crescent, surmounted by a three armed cross – the lowest arm of which is considerably shorter than the others – and supported by two brackets which also support the clouds. The interpretation of the symbolism or the armorial bearing is unknown. This tablet must have been contained in a pouch or bound to the wearer’s arm for there is no means of attachment on the tablet itself.

Garlake’s observations

Peter Garlake observed that there was little intrinsically remarkable about these objects. Their craftsmanship was ordinary and the designs have little individuality or artistic merit. The religious medallions were clearly mass produced to stereotypes designs. The copper rings were particularly poorly made while the silver and gold rings and adornments all have a high copper content.

The Portuguese trading settlements were partially excavated by Garlake at Dambarare, Luanze (Ruhanje) and Maramuca (Rimuka) The Dambarare excavations were limited to the single building, believed to be the church and burials, and only 2% of the site was excavated.

Dambarare was constructed along similar lines to Luanze and enclosed by straight brick walls so low that they must have formed only the cores of earth banks or foundations for timber palisades. In several cases a ditch was also cut outside the walls and at Luanze and Maramuca there are bastions at the centre of each outer wall.

Portuguese construction methods were used for all the major buildings – though some subsidiary buildings were of pole and dhaka. The large sun-dried bricks - identical to those used at Maramuca (Rimuka) - were made from clay in the immediate area, the floors and mortar were also clay. The actual standards of craftsmanship were mediocre – with great variation in the quality of the bricks and they were often poorly laid. However Garlake concluded despite this, their scale is impressive.

There were insufficient garrisons at the settlements to make an effective defence and most of the earthworks are sited on level open ground and none are sufficiently close together to give mutual support. Military defence was thus clearly, at least before the late 17th Century considered of minor importance.

The Portuguese settlements probably hosted small permanent populations

Both the documentary evidence and on-site evidence suggest that each of the four earthworks at Dambarare (sites 2 – 5) represented a separate trading or mining concern with the church serving a communal function. Probably during the dry season the small populations were supplemented by large trading caravans that came overland from Tete and Sena. The sherds of Chinese, Persian and European ceramics securely date this occupation to the seventeenth century and leave no doubt that the first occupiers were either Portuguese or their relatives and their close family.

Destruction of Dambarare by Changamire Dombo in 1693

Though the building excavated is clearly the church of Dambarare, there was no archaeological evidence of the damage caused by the Rozvi army of Changamire Dombo and his ally, the Mutapa Nyakaunembire in November 1693, when, as described by Antonio de Conceição, he killed the inhabitants before they could reach the safety of the fort, desecrated the church, disinterred some burials and had the priests flayed alive. Most of the Portuguese had already fled to Tete, but all the few remaining traders and their families and vashambadzi and Canarins (Konkani people from Goa who were recruited because they were Christian Indians) were killed.

Garlake thought such evidence may still appear with further excavations. However, it is not certain that Changamire fired or demolished the building and these are the only actions that would definitely leave their trace in the archaeological record. The scattered and badly decayed bones of Burial AW1 (at the base of a deposit formed at the final abandonment of the site) may have been disinterred at this time.

Garlake suggests that Earthwork 4 on the banks of the Marodzi River, and now under Jumbo Mine dam, is more likely to have been the fort of the settlement, as it appears to be better defensively sited and to have a defensive outwork. De Almeida y Sousa states that the fort was “a stone’s throw” from the river, but there was little sign of any buildings within it when examined by Garlake.

In the early 18th Century Dambarare may have been occupied again by Goan Indians, but it never returned to its former importance and by the 19th Century its location had been forgotten.

Occupation periods for Dambarare

There is clear stratigraphic evidence in the Dambarare excavations of two distinct periods.

The first period from 1631 - 1675 was marked by a steady evolution of the structures and continuous burials, culminating in the erection of the first church (the red brick building: strata 13 to 8) The great majority of the imports recovered belong to the first half of the seventeenth century.

During the second period 1684 – 1693 the first church was demolished and a considerable number of burials took place after its demolition (strata 7 and 6). Thereafter, during a comparatively short period, considerable, if intermittent, building work took place. The church was entirely rebuilt and a series of minor alterations and additions were made to it (strata 5 and 4) before its final destruction in 1693.

Garlake speculates that Dambarare may have been depopulated by disease and almost entirely abandoned between 1675 and 1684.

References

C.K. Cooke. Dhlo-Dhlo Ruins: The Missing Relics. Rhodesiana Publication No 22, July 1970

C. Dunbar. Dambarare: a Portuguese Settlement, Market (Feira) and Fort in Zimbabwe. https://www.colonialvoyage.com/dambarare-portuguese-settlement-market-fe...

H. Ellert. Rivers of Gold. Mambo Press, Gweru, 1993

Peter Garlake. Excavations At The Seventeenth Century Portuguese Site Of Dambarare, Rhodesia. Historical Monuments Commission, Salisbury, 1969

Peter Garlake. Some Early Portuguese Relics from Dambarare, Rhodesia. Historical Monuments Commission, Salisbury, 1969

C. Klehm. Trade Tales and Tiny Trails: Glass Beads in the Kalahari Desert. http://theappendix.net/issues/2014/1/trade-tales-and-tiny-trails-glass-b...

S.I.G. Mudenge. A Political History of Munhumutapa c.1400-1902. Zimbabwe Publishing House, Harare, 1988

R. Summers. Ancient Mining in Rhodesia. Trustees of the National Museums of Rhodesia, 1969.

Notes

[ii] Sancho de Tovar figures significantly in the Portuguese presence at Sofala. His ship became stranded at Sofala and was then set on fire to prevent its falling into the hands of the Swahilis. Upon his return to Lisbon, he was appointed in charge of Sofala and its surrounding region by Manuel I, a duty that he only took up after his return to Africa in 1515. He significantly improved and expanded the Portuguese fortress of São Caetano which `Pêro de Anaia had begun in 1505 and organized a number of exploratory missions into the interior of present-day Mozambique and met an emissaries of the Mutapa state.

[iii] Wikipedia: The Belem Monstrance is dated 1506 and attributed to the Portuguese goldsmith and playwright Gil Vicente, a commission by King Manuel I for the Royal Chapel, and later left in the King's will to the Jerónimos Monastery in Belém, at the time an outskirt of Lisbon, whence it derives its name. It is currently part of the collection of the National Museum of Ancient Art, in Lisbon.

Crafted in late Gothic style, it was fashioned of "1,500 mithqals of gold" weighing over 6 kgs brought from Vasco da Gama's second trip to India in 1502 as a tribute from the Sultan of Kilwa (in present-day Tanzania), a sign of vassalage to the crown of Portugal.

The base is inscribed:

O. MVITO. ALTO. PRICIPE. E. PODEROSO. SEHOR. REI. DÕ. MANVEL. I. A. MDOV. FAZER. DO OVRO. I. DAS. PARIAS. DE. QILVA. AQVABOV. E. CCCCCVI.

("The Most High Prince and Powerful Lord, King Dom Manuel I, ordered this to be made from the gold of the tributes from Kilwa. It was completed in 1506.")

[iv] Mudenge, P244

[v] Ellert, P9

[vi] Ibid, P9

[vii] Ibid, P11

[viii] The first two are National Monuments Numbers 151, 111. Massapa does not appear to be listed on the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) website

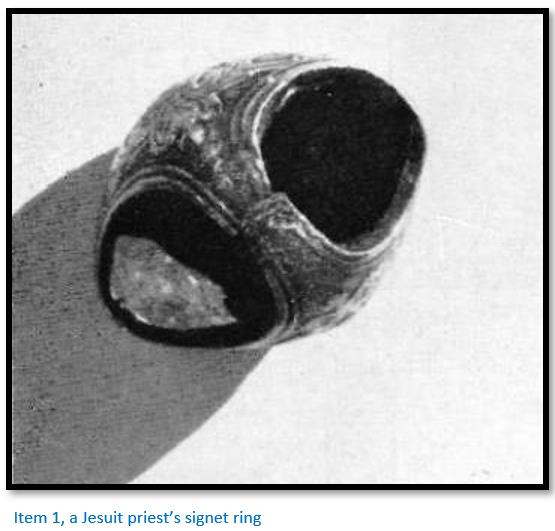

[ix] C.K. Cooke, a well-known historian authored an article in Rhodesiana Publication No 22, July 1970 called Dhlo Dhlo ruins: the Missing Relics. In 1895 Neal and Johnson whilst working for the Ancient Ruins Company found the items below that are listed in Hall and Neal’s book Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia (1902) P146-7. They included:

87 Two cannons: one bronze breech-loader, one iron muzzle-loader both with the Portuguese coat of arms (Rt. Hon. C. J. Rhodes)

88. Gold coin or medallion (Last in the possession of Dr Jameson)

97. Section of bronze bowl, size of ordinary washing basin (Captain Rixon)

98. Bronze Egyptian oil lamps

99. Portion of bronze incense censer

100. Portion of bronze key

102. One bell with handle

103. Priest's private seal (Rt. Hon. C.J. Rhodes)

104. Three feet of gold chain, broken; part of priest's regalia, with mass of molten silver attached, probably the cross

108. Section of silver plate embossed with vines, probably Sacrament plate

109. Pieces of silver plate, embossed

Cooke writes: There is an interesting note in a guide to the Rhodesia Museum, by R.N. Hall, of 1911. He states: 'PRIEST'S ALTAR FURNITURE FOUND AT DHLO-DHLO

'Unfortunately, the collection of articles once the possession of a priest of the Jesuit Order at Dhlo-Dhlo, 50 miles east of Bulawayo, discovered by Messrs. Neal and Johnson in 1895, at present in the Museum, appears to have been broken up, and some of the articles lost or mixed with other relics from elsewhere. The original collection consisted of:

(1) A Jesuit priest's signet ring issued by a missionary college in Portugal, believed by experts to have been Evora, with which college several of the Jesuit missionaries, who laboured in what is now Southern Rhodesia from 1505 to 1760, were connected. This ring was in the possession of Mr. C.J. Rhodes.

(2) A small bell of bell metal (crushed), with portion of ebony handle attached.

(3) Portions of a bronze incense censer.

(4) Sections of broken silver-plate, embossed with vines, pronounced to have been a sacrament plate, also sections of silver-plate engraved with "fleur de-lis" design.

(5) Bronze altar lamp (intact in 1902, but since broken)

(6) Portion of a bronze key, and pieces of bronze believed to have been parts of a small box.

(7) Three feet of gold chain, broken, with mass of molten silver attached, most probably a cross, part of a priest's regalia.

(8) Gold medallion, size of a five-shilling piece, embossed on one side with two birds fighting over a heart. (Last in the possession of Dr Jameson)

(9) Captain Rixon, in 1902, had a section of a bronze altar ewer in his possession, and this was found at the spot where the other articles of the priest had been discovered.

(10) In March 1911, Mr. H. Ryan found at about 100 yards from the spot where Messrs. Neal and Johnson made their discoveries, a bronze cup, the handle and spout of which had been broken off, which the Fathers in Bulawayo claim to have been used for holding holy water.

[x] UNESCO General History of Africa 16th to 18th Century (Editor) B.A. Ogot, P679

[xi] The Jesuits were expelled from Mozambique in 1759

[xii] Theal, 1898 II, P438" A Dominican report in 1631 states: “In the Kingdom of Mutapa the religious were in charge of three missions: Masapa, Ruhanje and Dambarare, each of them with one priest or one friar."

[xiii] Theal, 1898, II, P417

[xiv] Clearly a reference to the Mazowe river

[xv] Theal, 1898, III, P482

[xvi] At the time Caetano de Melo de Castro was Captain-General of Sena, Sofala and Mozambique Island. He was later appointed a Governor-General in Brazil and from 1702-7 was Governor and Viceroy of Portuguese India

[xvii] The present-day Murowodzi river

[xviii] Abraham, pers. comm. to Garlake

[xix] Abraham, pers. Comm, to Garlake

[xx] Theodore Bent and his wife made the first detailed examination of Great Zimbabwe which he describes in his book The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland (1892)

[xxi] D.P. Abraham authored many scholarly articles on the presence of the Portuguese in South-East Africa in the 16 – 17th Century

[xxii] The author believes Mr Light may have been working the Alice Mine at Essexvale (now Esigodini) when he was at Falcon College in the 1960’s

[xxiii] Often referred to as ‘ancient workings’

[xxiv] Ferguson, J.C. and Wilson T.H. (1937). The geology of the country around the Jumbo mine. Mazoe District. Salisbury: Geological Survey Office.

[xxv] Ancient Mining in Rhodesia, P41-42

[xxvi] Wikipedia gives Indian weights of faraçola. In Cochin (Kochi) 8.31kg. In Calicut ( Kozhikode) 10.37 kg. In Cannacore (Kannur) 10.28kg

[xxvii] Trade Tales and Tiny Trails: Glass Beads in the Kalahari Desert