Chikupo Rock Art Shelter – the Western Cave

Peter Garlake states the Chikupo caves contain probably the greatest number of paintings remaining on any site in Zimbabwe, many in excellent condition.

Fairly easy to access from Harare, perhaps 90 minutes journey on good to fair road. 4WD not required, although high clearance is advised for driving in the Communal lands.

The descriptions of the sites follows Peter Garlake in his outstanding book: The Painted Caves; an Introduction to the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe, the best of the available guides and the only one before or since that is original in its thoughts and ideas.

Jørn Støvring in his book called New Approach to Cave Art in Zimbabwe; Glimpse into the Mentality History of the Ancient San in the period from 10 000 BC to 600 AD is to be congratulated for his attempt to create a new understanding of the rock art concentrating on Mashonaland and is to be commended for assisting in creating a database of over 3,000 high quality photographs.

It appears that the collaboration with National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) was a productive one. Rockart research on this subject in Zimbabwe does not appear to have received much attention – no doubt due to the low priority given to this period, Zimbabwe’s continuing economic malaise and lack of funding and the political priorities of the various Directors of the NMMZ. Hopefully, all these shortcomings will be addressed in the future through further collaborations such as this one.

Leave Harare on the Borrowdale Road, distances are from Borrowdale police station. 13.4 KM the road crosses a grid and enters the Chinamora Communal Lands. 16.3KM pass the signpost to Domboshava National Monument. 26.6 KM pass the signpost to Ngomakurira National monument. 30.0 KM leave the tar road and turn left onto the dirt road. 34.8 KM pass Chinamora School primary / secondary school, 39.4 KM pass Jingo School, 43.1 KM turn right at T-junction. 51.0 KM turn right at Chisiga store for Masembura School: 52.3 KM pass Masembura School turnoff. Do not take the right fork. Pass the large granite dome on your right. Chikupo is the large low hill ahead on the right; 56.5 KM turn right onto the track and park at the foot of the hill. I suggest you ask a local person to guide you the last few hundred metres. The Borrowdale road to the Chinamora Communal Lands is a good tar road. The next 17 KM of tar road is much repaired with numerous potholes. The dirt road to site is quite passable in 2WD as long as caution is taken where the road gets eroded in the rains. Journey takes about one and a half hours.

The Chikupo caves are facing you on the east side of the hill and are reached by taking the path and then turning right up a short, scree slope. There are three caves within close proximity. The Southern and Central caves are easily reached, but the Northern cave has a slippery exterior rock face and is most easily climbed at the western end. The Western cave is out of sight of the three caves and is best reached by scrambling over the neck of the bare granite hill. Once passed, the cave is visible above you. Alternatively walk west around the base of the hill and climb. The paintings are in the higher of the two caves. If you run out of time, I suggest you omit the Western cave.

The three adjoining caves at Chikupo Mountain:

Southern and Central cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′42.55″S 31⁰17′21.18″E

Northern cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′40.48″S 31⁰17′25.78″E

and another across the valley:

Western Cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′41.83″S 31⁰17′17.30″E

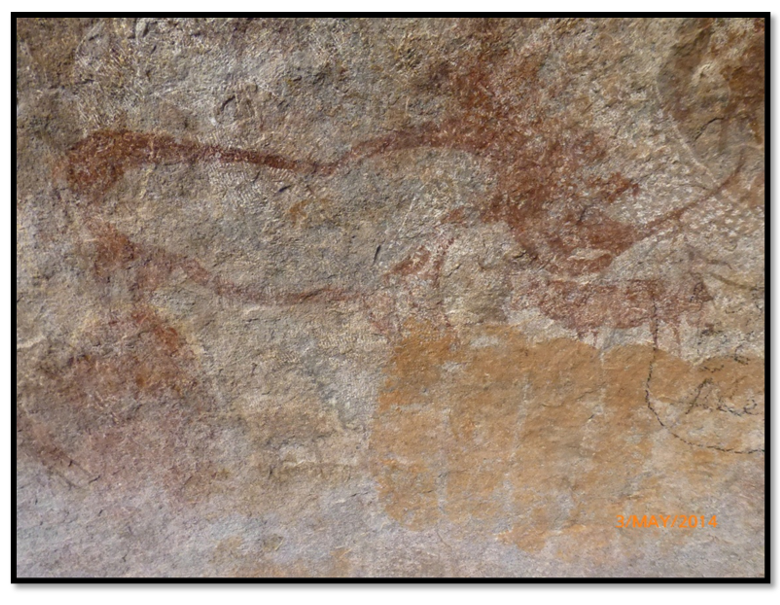

The Western cave also has a mass of paintings, but most are now rather faded and indistinct. The floor of the cave is covered in lumps of dhaka and rocks that appear to have been transported into the cave, some look as they have been used as grinding stones or querns.

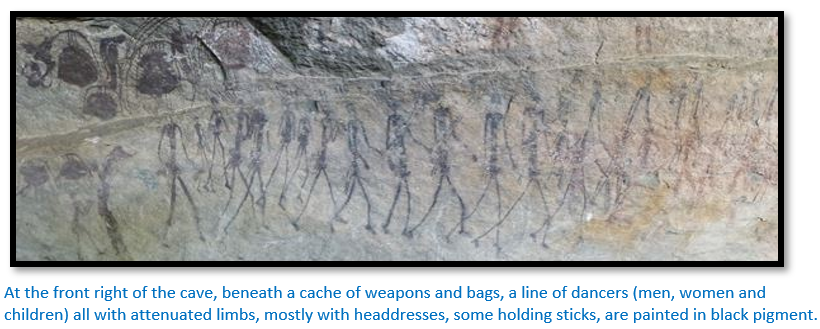

At the front right of the cave, beneath a cache of weapons and bags, a line of dancers (men, women and children) all with attenuated limbs, mostly with headdresses, some holding sticks, are painted in black pigment.

Peter Garlake describes a line of 29 men, in black, with long thin legs and large feet, some divided to form two toes. They wear aprons or tails and have tufts above their aprons. Their hair is long and on end. Three are armed. Some carry switches or rattles. Behind them are their weapons and bags, hanging from branches, on one of which a warthog head is impaled. This may well be a dance, the near absence of weapons; the tufts worn on the buttocks, the location near a camp, the rattles, the uniform rhythmic postures are all suggestive of this. The eighth figure in the line from the left holds his arms rigidly in front of him, suggestive of dancing and the start of a trance ceremony.

On the far left and separate from the line, a male in an elaborate headdress faces outwards towards a woman who appears to be offering him some object. Above the frieze two women painted in white face each other – Garlake states they confront each other.

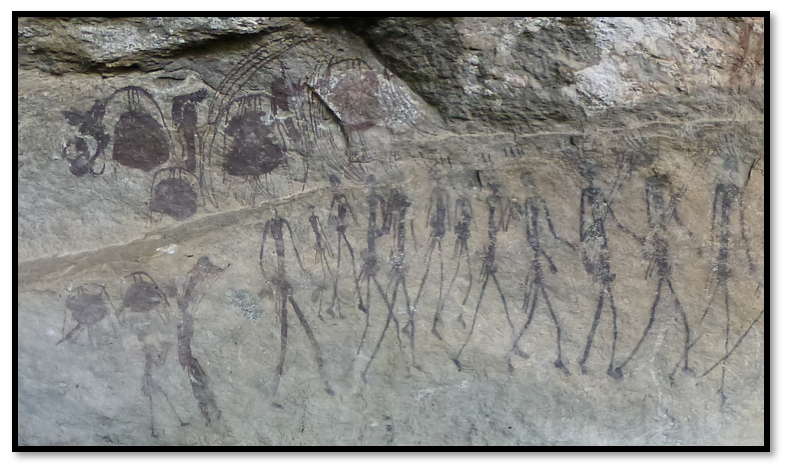

Section of the above described scene

At the time I visited, the day was very overcast and with the lower light levels it was difficult to discern some of the images.

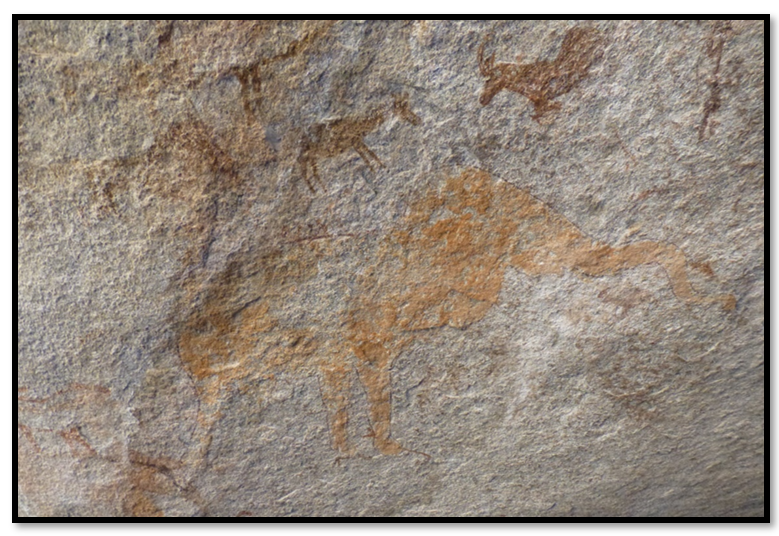

The roof is dominated by a large faded yellow ochre elephant which has been outlined in red, around are characteristic kudu in red ochre, small antelope, buffalo, sable and zebra.

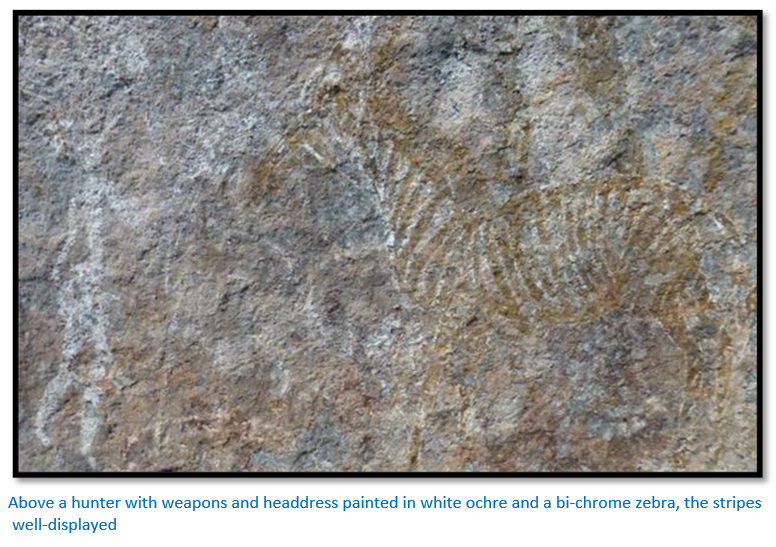

Above a hunter with weapons and headdress painted in white ochre and a bi-chrome zebra, the stripes well-displayed

On the left wall there appears to be an outline of an elephant enclosing a mass of animals – including kudu and some beautifully drawn, small, bichrome buck, as well as buffalo, rhino, bush pig, sable and zebra, a few painted in black paint and outlined in white.

The photo shows a crowded scene of small animal paintings that have been over-painted by some later crude clay images of animals and humans.

There are a number of characteristic oval forms in red or yellow ochre outlined in white and with white caps. These are San symbols reflecting the presence, control and release of potency, although often the white paint has faded entirely away. In the above photo, a field of white dots enclosed with white lines can be seen streaming away from the oval. Often they enter the oval through a narrow through a single narrow entry point – for this reason they were often described as bee hives in the past. However, here they flow outwards from the entire width of the oval and over the head of a rhino…the rhino’s body in outline, its head filled-in with red ochre. There appears to be a large figure of a hunter with shoulder bag painted in white on top of the rhino, but the image has faded significantly.

The ovals seem to convey a concept of potency to the San referred to as n/um. During a communal trance dance the n/um becomes activated and causes a pricking sensation within the dancers stomach. When active the San believe the n/um overflows, ‘boils over’ and is released up the spine of the dancer. The pricking sensation: like ‘thorns, ‘arrows pressing the flesh’ or ‘bee stings’ is conceptualised as the white dots above the oval.

An image of what appears to be a zebra painted in black and outlined in white with white vertical lines representing its mane. Underneath two crudely drawn humans painted white and crouched over, apparently in trance.

On the rear roof are some large-faded antelope (>60cm) and a hippo. Towards the floor of the cave is a therianthrope painted as a crouched figure with antelope ears, baboon tail, hooves, human legs and torso and tulip penis.

A herd of sable, the lower two animals drawn smaller, perhaps an early attempt to draw in perspective (?) the muzzles left unpainted to indicate the white sable markings – their sable body shape is not as accurate as usual in San rock art.

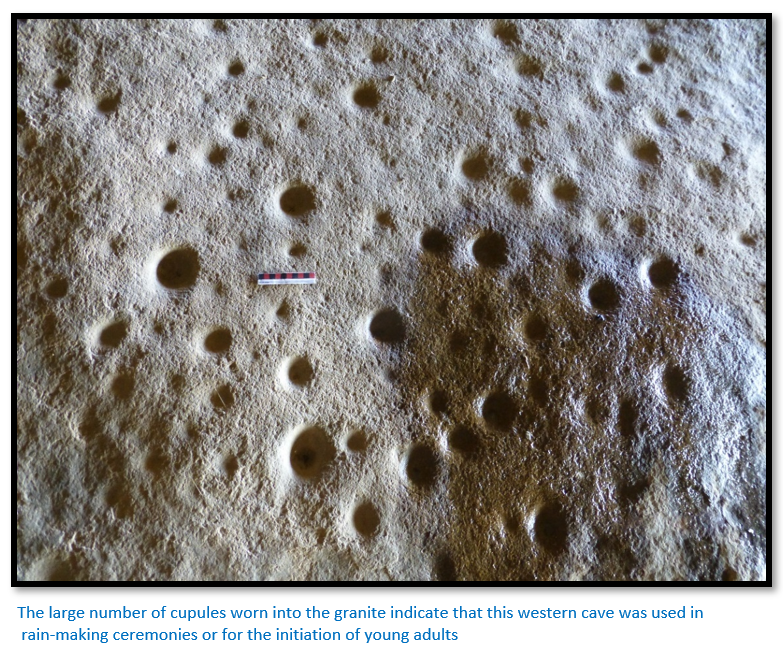

The large amount of pottery and dhaka and numerous cupules (small round holes) worn into the granite may indicate that this cave was used in comparatively recent times for rain-making or initiation ceremonies.

The large number of cupules worn into the granite indicate that this western cave was used in rain-making ceremonies or for the initiation of young adults

In 2014 there was also evidence of fire-making within the cave which will quickly destroy the rock art images, as has happened at Makumbe cave, the article is under Harare on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

References

Peter Garlake. The Painted Caves, an introduction to the Prehistoric Rock Art of Zimbabwe. Modus Publications. 1987

Peter Garlake. The Hunter’s Vision, the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1995

Thomas N. Huffman. The Trance Hypothesis and the Rock Art of Zimbabwe. South African Archaeological Society. Goodwin Ser. 4. 1983

Rupert Isaacson. The Healing Land. Geographical 73.7; 7 (2001): 53

Richard Katz. Boiling energy: community healing among the Kalahari Kung. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press. 1982

J. David Lewis Williams. Believing and Seeing. Academic Press. 1981

Lorna Marshall. The Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen. Journal of the International African Institute 39: 347-381. 1969

Martin D. Prendergast. Early Iron Age furnaces at Surtic Farm, near Mazowe, Zimbabwe. SAAB Bulletin 38: 31-32. 1983

Jørn Støvring. New Approach to Cave Art in Zimbabwe; Glimpse into the Mentality History of the Ancient San in the period from 10 000 BC to 600 AD. 2021