Chikupo Rock Art Shelter – the Central Cave

Peter Garlake states the Chikupo caves contain probably the greatest number of paintings remaining on any site in Zimbabwe, many in excellent condition.

Fairly easy to access from Harare, perhaps 90 minutes journey on good to fair road. 4WD not required, although high clearance is advised for driving in the Communal lands.

The descriptions of the sites follows Peter Garlake in his outstanding book: The Painted Caves; an Introduction to the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe, the best of the available guides and the only one before or since that is original in its thoughts and ideas.

Jørn Støvring in his book called New Approach to Cave Art in Zimbabwe; Glimpse into the Mentality History of the Ancient San in the period from 10 000 BC to 600 AD is to be congratulated for his attempt to create a new understanding of the rock art concentrating on Mashonaland and is to be commended for assisting in creating a database of over 3,000 high quality photographs.

It appears that the collaboration with National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe (NMMZ) was a productive one. Rockart research on this subject in Zimbabwe does not appear to have received much attention – no doubt due to the low priority given to this period, Zimbabwe’s continuing economic malaise and lack of funding and the political priorities of the various Directors of the NMMZ. Hopefully, all these shortcomings will be addressed in the future through further collaborations such as this one.

Leave Harare on the Borrowdale Road, distances are from Borrowdale police station. 13.4 KM the road crosses a grid and enters the Chinamora Communal Lands. 16.3KM pass the signpost to Domboshava National Monument. 26.6 KM pass the signpost to Ngomakurira National monument. 30.0 KM leave the tar road and turn left onto the dirt road. 34.8 KM pass Chinamora School primary / secondary school, 39.4 KM pass Jingo School, 43.1 KM turn right at T-junction. 51.0 KM turn right at Chisiga store for Masembura School: 52.3 KM pass Masembura School turnoff. Do not take the right fork. Pass the large granite dome on your right. Chikupo is the large low hill ahead on the right; 56.5 KM turn right onto the track and park at the foot of the hill. I suggest you ask a local person to guide you the last few hundred metres. The Borrowdale road to the Chinamora Communal Lands is a good tar road. The next 17 KM of tar road is much repaired with numerous potholes. The dirt road to site is quite passable in 2WD as long as caution is taken where the road gets eroded in the rains. Journey takes about one and a half hours.

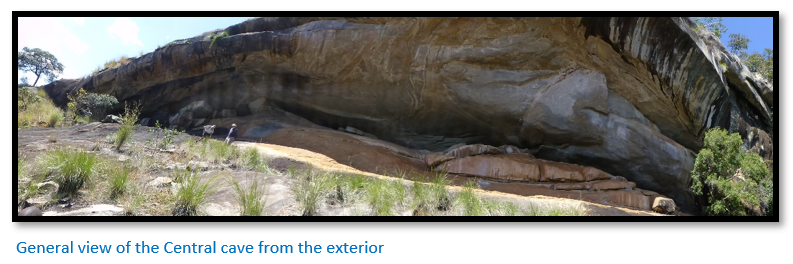

The Chikupo caves are facing you on the east side of the hill and are reached by taking the path and then turning right up a short, scree slope. There are three caves within close proximity. The Southern and Central caves are easily reached, but the Northern cave has a slippery exterior rock face and is most easily climbed at the western end. The Western cave is out of sight of the three caves and is best reached by scrambling over the neck of the bare granite hill. Once passed, the cave is visible above you. Alternatively walk west around the base of the hill and climb. The paintings are in the higher of the two caves. If you run out of time, I suggest you omit the Western cave.

The three adjoining caves at Chikupo Mountain:

Southern and Central cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′42.55″S 31⁰17′21.18″E

Northern cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′40.48″S 31⁰17′25.78″E

and another across the valley:

Western Cave GPS reference: 17⁰26′41.83″S 31⁰17′17.30″E

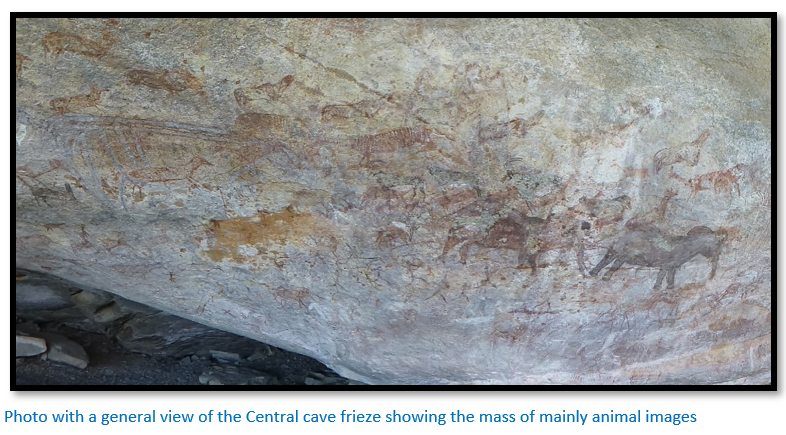

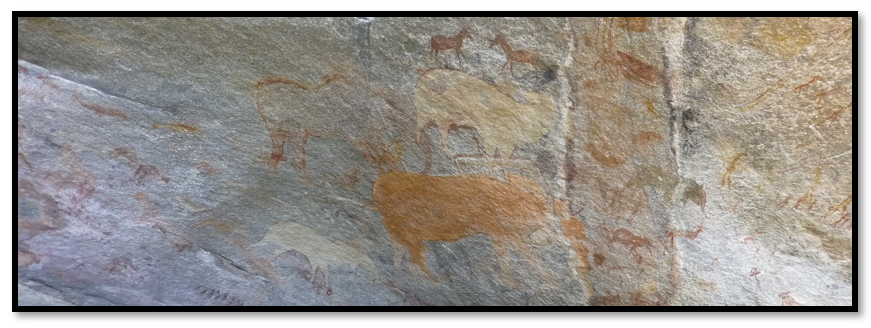

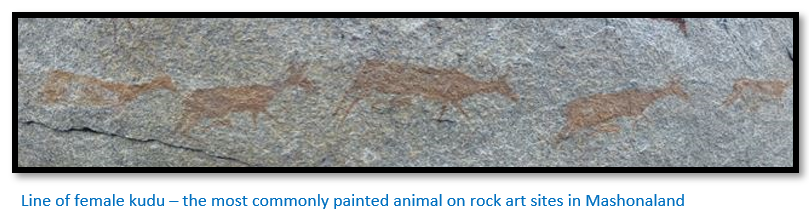

The Central cave to the west has a long line of animals painted across it with over 30 images including kudu, buffalo, roan, sable and warthogs. Their variety and abundance, rather than their quality, is unusual.

This small segment of the line shows some kudu does with young.

In the centre of the cave roof is a small obese male figure, in characteristic frontal posture, with arms raised and legs apart. He has a tulip penis, rattles on his shoulders and lines coming from his upper arms. These lines do not appear as losses of blood, sweat or bodily fluids as the figure does not appear distressed or engaged in activities likely to result in such losses. The best explanation is that they represent the release of various forms of spiritual energy or potency, in the way that the San believe their individual potency, n/um, is released from their bodies through dancing and trance.

The obese figures like the one above, are often found in pairs, male or female, with legs bent and spread-eagled and arms raised. Limbs and head have normal proportions, but the stomach is grossly extended, often they look like tortoises. They may have elaborate rattles or crescent objects, the rattles indicating they are dance participants. They are usually naked and without equipment; but their heads and headdresses take various forms. In Mutoko, they have short muzzles, antennae and bobbed hair, in Marondera they have long animal ears and long pointed muzzles. Females may have double-lines zigzagging from between their legs and small figures may crouch or climb up and down on these lines. In the historic literature, these figures were referred to as “mother goddess”; an assumption based on European prehistoric cave art.

From what we know of dance, trance, potency and its release, these obese figures are dancers with unusual concentrations of potency, or n/um, within their stomachs which is becoming active and expanding. The release of this potency is represented by the streams that emerge from the chests and genitals of these figures.

There are at least four ovals objects in this section. The one below has white dots in the upper left-hand segment. The meaning behind these ovals is covered in more detail in the article on Zombepata under Mashonaland Central on the website www.zimfieldguide.com They appear in almost every frieze across the country varying in size from a few centimetres to a metre or more. Within each oval is usually a field of white stippling, like tiny arrowheads or dots, as appear below. These may enter the oval through a single opening. The oval maybe attached to people, as in Diana’s Vow, or appear in association with animals, or trees. See the article Diana’s Vow under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

They are not realistic representations of actual objects such as clouds, boulders, hills, fields, landscapes, huts, grain bins, xylophones, quivers, seedpods, bird’s nests, bees’ nests, or honeycombs. Rather, they represent a single concept of great power and significance to the artists; this source of spiritual energy is known by the San as n/um. This idea seems to have been central to the beliefs and spiritual life of all San groups and developed a long time ago.

N/um is released through communal dancing and its use and control are essentially communal acts within San Society. Connected ovals express the potency of the entire group through dance and explain why it is such a dominant and widespread motif in their art. Together with the obese figures, ovals represent a single coherent system of imagery representing the central ideals and beliefs of San society concerning personal potency and its release.

On the roof towards the rear, on the right is an ostrich with five chicks.

Nearby is another trance scene. Eleven figures, outlined in white, standing, sitting and lying, have extraordinarily attenuated bodies and limbs. Long meandering lines issue from mouths, chests or hands. Two hold birds, one a crescent, some have shoulder bags. The lines represent a release of potency, and the attenuation of the bodies represents a characteristic sensation induced by trance. The figures on the right are on all fours; this signifies they are in a deep level of trance. On the right are five bichrome figures edged in white led by a therianthrope with large ears, the others are crouched, crawling and recumbent. This scene probably is an attempt to portray the supernatural inhabitants of the spirit world, the gauwasi, seen by the artist whilst in trance.

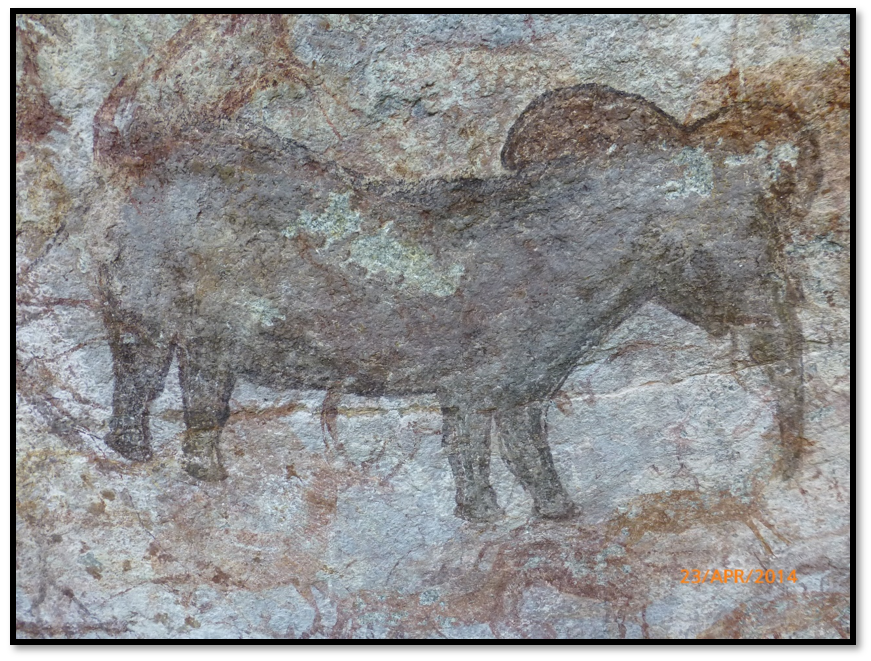

At the front of the cave, high at the southern end is a large elephant, drawn in an unnatural style, its body filled in with a few rough brushstrokes. Two large hippos are crudely painted in a thick cream pigment. Superimposed on one hippo is a beautiful kudu cow with white outline and details and a line of six warthogs.

Garlake describes the above drawn on the ceiling as ‘two very tortoise-like obese figures.’ They are probably portrayals of human dancers with unusual concentrations of potency, or n/um, within their stomachs which is becoming active and expanding. Through their dance and by hyperventilating they are going into trance and will soon enter the spirit world.

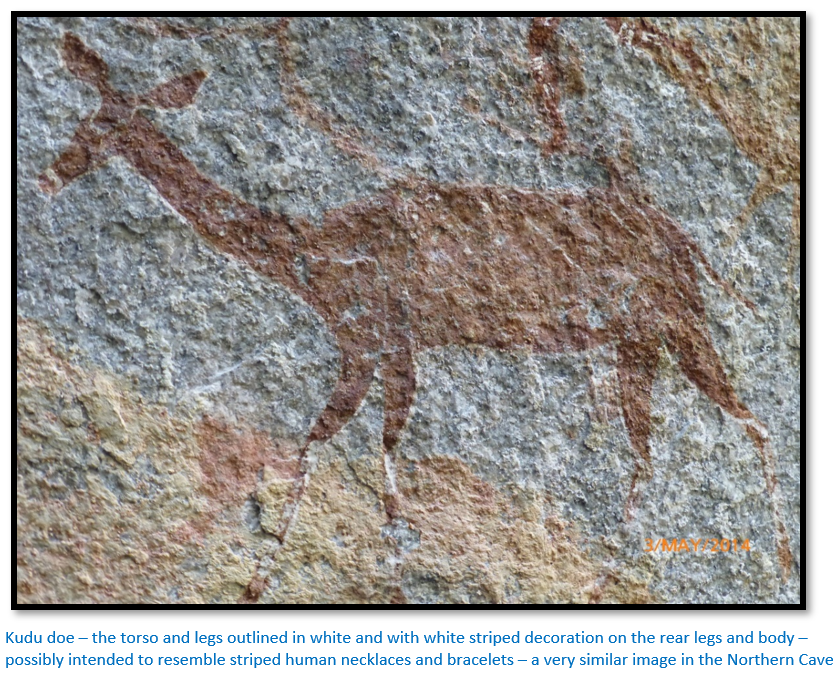

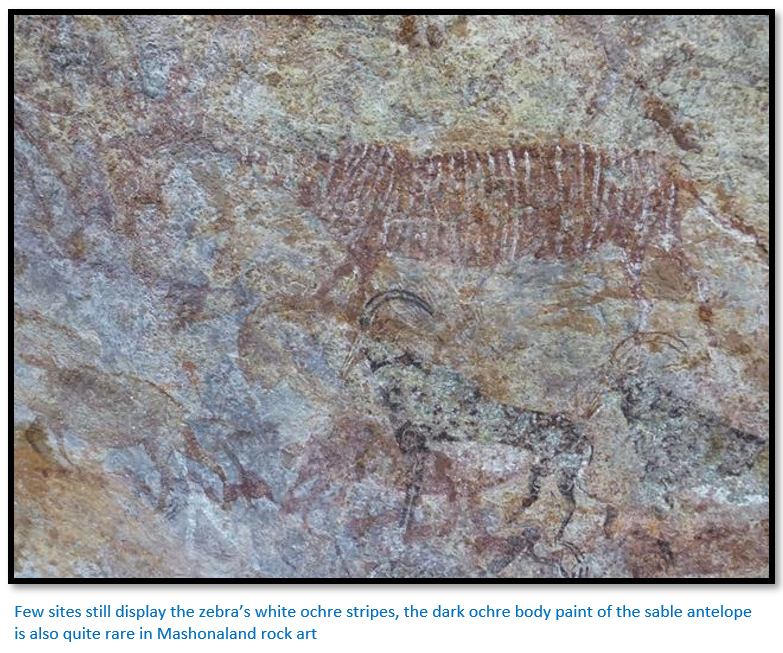

On the vertical projecting curve of the cave wall are two small elephants, left of them what were once five very fine, dark sables with white body markings and white bellies, now much faded with a kudu covered in fine white stripes above them. Garlake believes they have been ‘pecked’ i.e. the black paint has been chipped away deliberately at a later date for medicinal or ceremonial purposes.

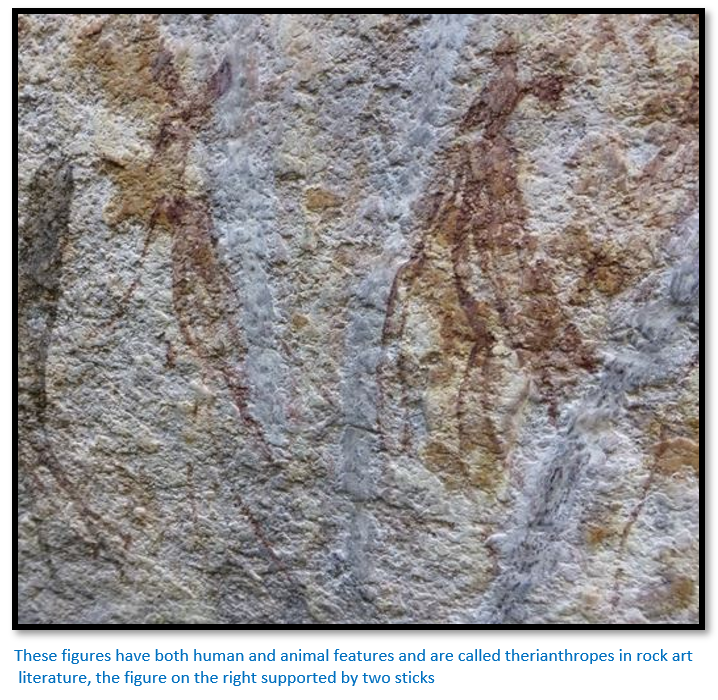

In the only scene of its type in these caves, a line of at least five small therianthropes ( a dancer in trance who gains the animal features from which he / she derives their potency) with long snouts, large ears, long thin delicate limbs and wearing capes with some supported on sticks are painted. Thick white clay lines, probably drawn with a finger run vertically through them.

I have already discussed communal dancing in San society which may induce trance and the release of potency, or n/um. Animal dances are important to the San, but in performing, animal masks and skins are not used. At most, the dancers may wear a skin cap with ears attached and paint their bodies. So, the figures below are not depictions of San in animal costume.

They are best interpreted as creatures with animal attributes that exist in the supernatural, or trance world of the artists. They commonly have human bodies, arms and feet, but their limbs are extremely long, thin, and stick-like and may end in hooves. Often, they have long tails, pointed muzzles, and the ears of an antelope. They walk upright and are naked, although they may wear capes on their shoulders.

They may represent the gauwasi, the ghosts, and spirits of the dead who inhabit the supernatural world of the gods.

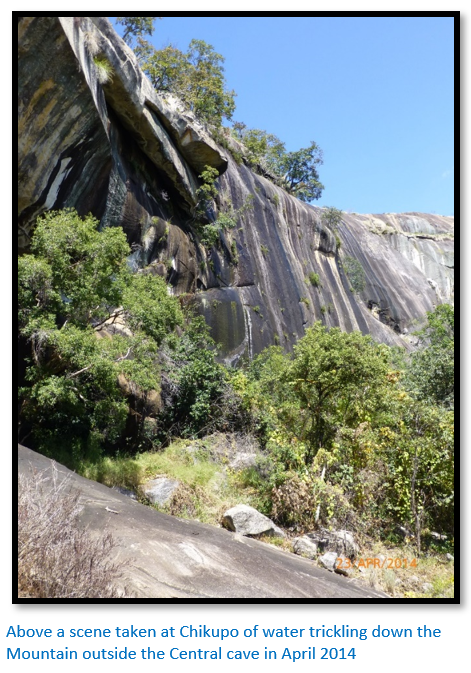

Jørn Støvring in his book called New Approach to Cave Art in Zimbabwe; Glimpse into the Mentality History of the Ancient San in the period from 10 000 BC to 600 AD believes the above image represents waterfalls streaming off the mountain in what he calls the ‘humid period.’ This interpretation itself should not be dismissed but seems to me a bit conjectural and designed to fit the underlying narrative – we have seen various interpretations throughout the history of rockart study and attempts to fit the paintings into different painting periods – but few are based on the San vision of their world.

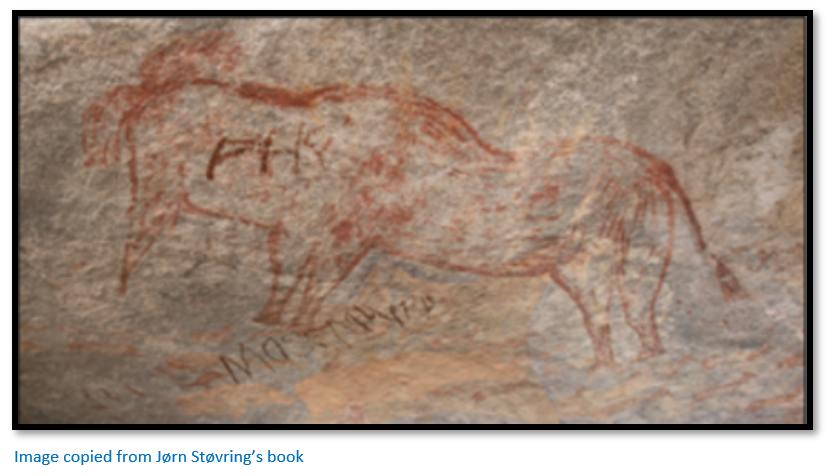

On page 24 of his book Jørn Støvring has an image he calls ‘the radiating jackal’ which shows a yellow image which predates the ‘humid period’ behind a red figure […of a rather crudely drawn elephant] and goes on to say: “The authors of the red image left their signature outside in the form of a swastika. The swastika can be dated post-second world war and the painters must have been Caucasian. Both point to the short-lived colonial regime declaring a unilateral declaration of independence from Britain (1965 - 1980). The intention was to degrade local culture, even though the San are not related to the Bantu. They managed partly to destroy a significant early San image painted in yellow.”

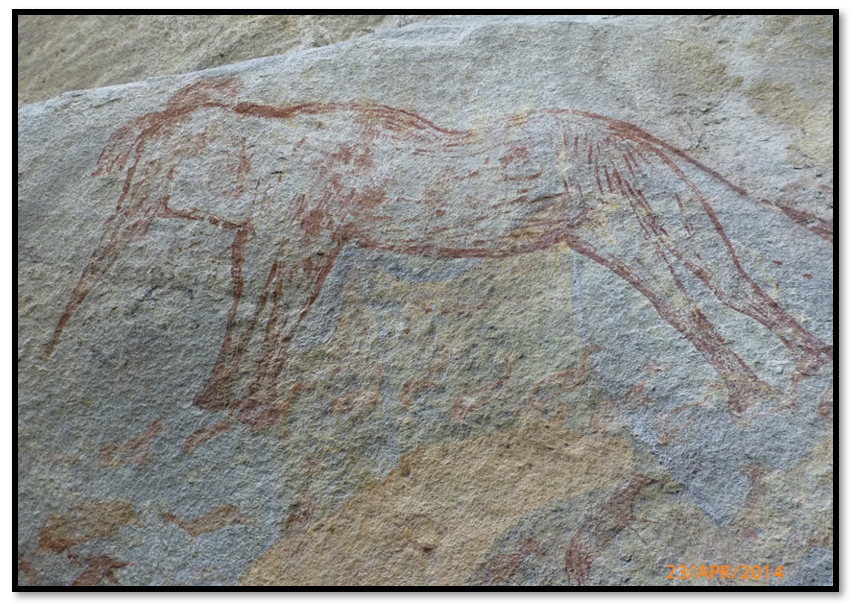

Above is a rather clearer image of the same elephant I took in 2014. Perhaps I am mistaken, but Jørn Støvring seems to be suggesting that the red image of the elephant was painted post 1965 after Rhodesia declared Independence. Is this really conceivable as the elephant is painted in a red ochre which has been produced from natural earth ingredients and matches exactly with nearby San images?...I think it is extremely unlikely that graffiti artists would go to these lengths.

There are superimposed painted images often obliterating underlying images in all of the Chikupo caves. Did Jørn Støvring come to his rather radical conclusion based on the rather poorly rendered image of the elephant? If so, below is another image of a rather poorly proportioned elephant from the same Central cave. San images are often, but not always perfectly proportioned when painted.

Note the graffiti on and below Jørn Støvring’s image above is not on my photograph taken in 2014 and to say the swastika is related to the San elephant image is really a leap too far!

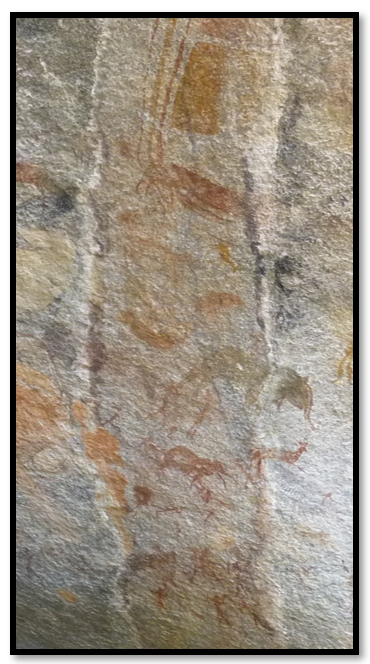

Jørn Støvring has a page (P27) called ‘The Clash’ which apparently illustrates the transition from the pre to the post-humid period and the images used in the example are shown above and are from the Central cave. [I have put my remarks in brackets and in italics] The text reads: This man-size composition is situated at the extreme right in the Southern Cave. On top two antelopes face off each other. [They have characteristic features of zebra without stripes] Three animals in red, orange, and yellow gallop towards a boundary. [The animals are all elephants and there are four all facing to the right; the top one painted in yellow ochre, the next down in outline only, the next down in orange ochre, the last in pale yellow]

Parts of the heads get to the other side. [Presumably Jørn means to the other side of the first white line which marks the water flow, and which has a second white line – they indicate where mineral salts have leached from the granite? When this image is enlarged, the original trunk of the top elephant and the trunk of the orange ochre elephant can be faintly seen where they have been washed out by the water flow]

Nonetheless, a new head is seen holding back from the boundary. [No…what may look like ‘new heads’ when the image is enlarged can be seen to be the original ears of the elephants]

There are white sediments created from water running down the rock during the long Humid Period. [No, this is simply water seepage from the roof of the cave which has percolated through the granite rock along fault lines during the last two millennials] They run in between the two heads and are also visible on the right side. Parts of the white sediment line down was later overpainted, but the white line is still visible. [No, there is no painted white line; this is mineral salts that have been leached from the granite in a natural process] There are in fact two lines of white sediments with an around 40 cm area in-between. [correct]

As can be seen from a slightly enlarged version of my 2014 photo, numerous other images have faded under the water flow; on the right-hand side the red outline of a small elephant image is intact outside the white sediment line, but faded within, the same with the kudu doe directly underneath.

References

Peter Garlake. The Painted Caves, an introduction to the Prehistoric Rock Art of Zimbabwe. Modus Publications. 1987

Peter Garlake. The Hunter’s Vision, the Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe Publishing House. 1995

Thomas N. Huffman. The Trance Hypothesis and the Rock Art of Zimbabwe. South African Archaeological Society. Goodwin Ser. 4. 1983

Rupert Isaacson. The Healing Land. Geographical 73.7; 7 (2001): 53

Richard Katz. Boiling energy: community healing among the Kalahari Kung. Cambridge, Mass. Harvard University Press. 1982

J. David Lewis Williams. Believing and Seeing. Academic Press. 1981

Lorna Marshall. The Medicine Dance of the !Kung Bushmen. Journal of the International African Institute 39: 347-381. 1969

Martin D. Prendergast. Early Iron Age furnaces at Surtic Farm, near Mazowe, Zimbabwe. SAAB Bulletin 38: 31-32. 1983

Jørn Støvring. New Approach to Cave Art in Zimbabwe; Glimpse into the Mentality History of the Ancient San in the period from 10 000 BC to 600 AD. 2021