Zvipadze Monument (formerly known as Harleigh Farm Ruin)

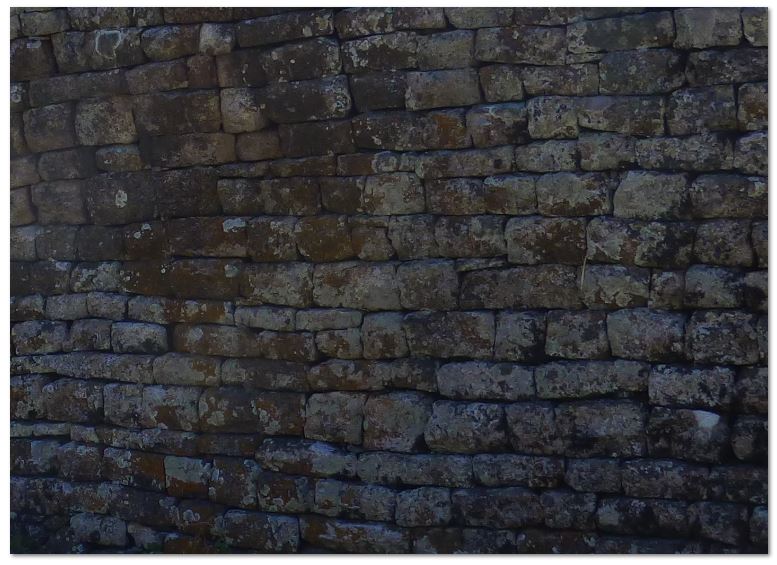

The 1st ruin is a Zimbabwe-type ruin with well-laid dry-stone walling

The 2nd ruin has a very unusual ditch and bank system, which early explorers described as a moat.

They are within 500 metres of each other and provide a diversion of historical interest on the way to Nyanga.

From the intersection of the Harare to Mutare Road (A3) and turnoff to Nyanga (A14): drive along the A14 towards Nyanga, 0.95 KM turn left onto tar road which is signposted: Silver Bow Road / Harleigh Farm ruins 15 KM / Diana’s Vow rock paintings 30 KM. At 14.5 KM turn right at the former Harleigh Farm tobacco barns, but see the guide recommendation below. Follow the farm track 0.5 KM and turn left at the fork passing a number of resettled farmers, 1.7 KM turn left at the intersection, 2.0 KM turn right at the fork. 2.1 KM turn left for the rock paintings which are signposted and 80 metres away. 2.3 KM reach Zvipadze Monument No 1 parking area. The Monument walls are clearly visible 70 metres to the left. To reach Zvipadze monument No 2 follow the farm track another 500 metres.

The road to Harleigh Farm is tar with potholes, but tolerable. The farm track to Zvipadze monument requires high clearance, but not 4WD.

It is recommended that visitors phone the Headman’s son Biggie (0777000331) to check if he can guide them. He is at Harleigh farmhouse. Turn left at the tobacco farms and follow the track to the farmhouse. The local community act as guardians at this monument and keep the all the grass down and clear the parking areas and it is considerate to acknowledge this effort with an appreciation.

HOW TO GET BACK TO THE A14 TO INYANGA

From the car park take the farm track back to the main road, 2.7 KM turn right onto the main road, 16.5 KM pass the Diana’s Vow turnoff to the right; 16.7 KM turn right onto the Constance Road, 29.5 KM turn left onto the A14 for Nyanga. The Constance Road is gravelled and can be bumpy, particularly after the rains.

GPS ref for the nearby rockart site: 18⁰27′04.10″S 32⁰13′41.71″E

GPS ref for Zvipadze Monument No. 1 parking area: 18⁰27′07.32″S 32⁰13′44.85″E

GPS ref for Zvipadze Monument No. 2 parking area: 18⁰27′10.56″S 32⁰14′01.17″E

The San rock art paintings nearby are underneath an overhang that looks like a giant granite mushroom. The paintings at the panel are clear, but the red ochre paint has faded. At the top a mass of stippling, made up of short dashes of red ochre paint, weaves its way across the rock interspersed with images of trees. This is not a representation of a lake, river or grassland, birds or bees, or the wind, or pollen.

Stippling in rock art is much more enigmatic than is supposed and probably indicates n/um (or spiritual energy) which has been activated in trance dance, boiled over and is released from the body during trance. [For a full explanation see the Thetford Game Reserve Rock Art Site article under Mashonaland Central]

The stippling effect and association with trees is quite a common rockart theme in Mashonaland; the paintings at Murehwa Cave, Gambarimwe Cave, Glen Norah East and Bushman Point at Lake Chivero do the same. To reinforce this explanation, a large figure of a man with elongated limbs is below the scene of stippling and below him are a line of at least eleven humans engaged in a trance dance. Some lean forward and appear to be supported by the dance participant in front of them.

There are two Monuments of different date and style.

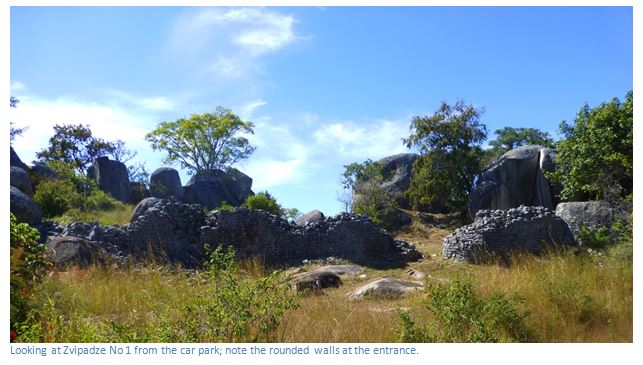

Zvipadze No 1 is visible about 70 metres on a path west from the car park area. This Zimbabwe-type ruin has a massive outer enclosure with well-laid dry-stone walling and a single entrance with rounded corners. The 1959 excavation by P.A. Robins and Anthony Whitty entitled Excavations at Harleigh Farm, near Rusape, Rhodesia 1958-1962 revealed pottery and finely made dhaka hut floors and walls that date to the seventeenth century and are contemporary with Great Zimbabwe. A human skeleton was also recovered from beneath a hut floor. The authors state this Zimbabwe-type ruin is rare in the district – the only two examples being here and another on neighbouring Devonia Farm, about 3 kilometres NNE with a clear line of sight between the two.

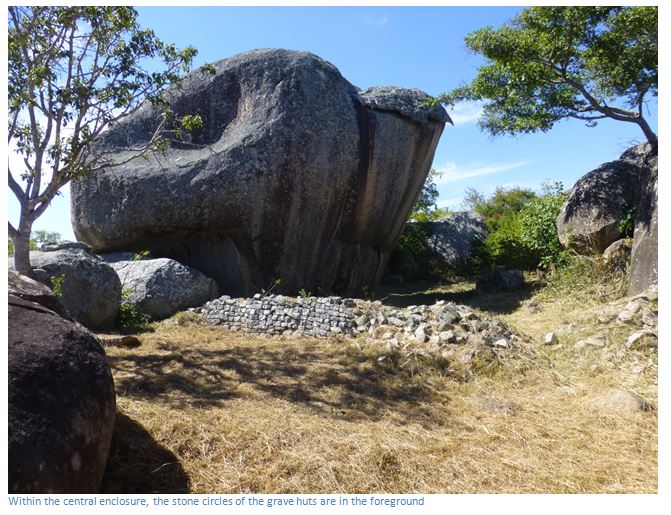

After being initially deserted, the building was then briefly reoccupied. Early European travellers reported that this ruin was held in great respect by neighbouring villagers with Chief Zvipadze being buried within it. His grave and three others originally had thatched huts over the graves, but only stone circles survive today.

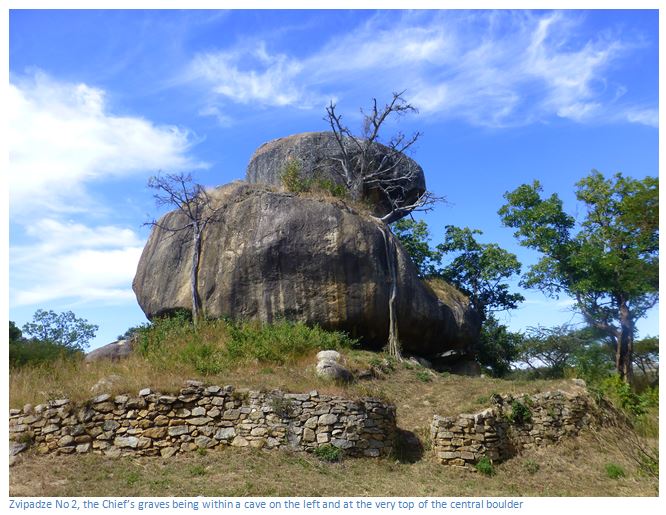

The second ruin is at an isolated kopje 500 metres away. It is in the style of the Nyanga Lowland Culture in its siting and in its building technique; but differs from them in that, very unusually for Zimbabwe, the ruin is surrounded by an elaborate ditch and bank system. The inner bank of the outer ditch originally had a wooden palisade, which have taken root and today form trees. Heaps of stone are often interpreted by visitors as graves, but they are not and may be the result of clearing the land for cultivation.

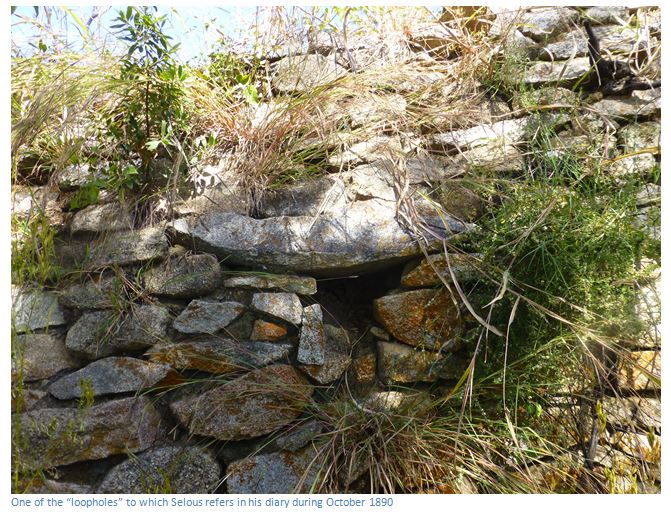

The central rocky outcrop contains many circular hut and grain bases and is encircled by a wall with a lintelled entrance. Several early travellers, including F.C. Selous, described this place as his diary on 19th October 1890 records. “On this day I left Makoni’s and passed some very curious ruins. First, there was a hill on which were built several concentric walls and the stone foundations of round huts, the whole being surrounded by a moat. A little further on there was a small kopje composed of a few large blocks of granite, some of which were piled up in the centre in the form of a tower. The whole of this kopje was enclosed by a very well built wall about two hundred yards in circumference, eight feet in thickness, and ten feet in height. The stones comprising this wall had the appearance of having being cemented together with mud, which is the first time I have ever noticed anything of this kind in south-eastern Africa. Through this wall there were four entrances, apertures about four feet in height and two and a half feet in breadth. These apertures were let into the base of the wall, and were roofed over with large flat slabs of granite. Inside this wall were the foundations of numerous round buildings. These foundations were all very well built of closely-fitted pieces of squared granite, and were about eighteen inches in depth…Besides the four entrances into the stronghold, there were numerous small holes let into the wall, some of which may have served as loopholes through which archers discharged arrows, but others from their position, I judge to have been intended for drains to carry off water.

Selous says it was known as “Chitekete and was the old kraal of Chipunza, or Chipadze, Chief of the Ungwe tribe, who under the same ruling dynasty (Makoni) still live in the area. “

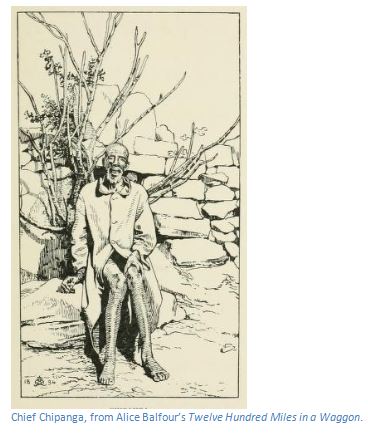

This ruin was also described by R.N. Hall in 1892 and also by Alice Balfour in 1894 in her charming book Twelve Hundred Miles in a Waggon which I quote at length:

On the 23rd we outspanned at the Rusapi, or Lesapi River, near which there are some ruins that Mr Selous told us of and thought that we should like to see. Accordingly we started after breakfast, riding about four miles to Chipanga’s kraal, he being the Chief to whom we were to apply for a guide to take us to Chititeke and Chipadze’s grave, at both of which places there were ruins. The natives are afraid to go to the latter; hence Mr Selous said we were to say we were his friends to induce Chipanga to help us.

The kraal is most picturesquely situated on high rocky ground above the river. We were taken to the further side of it, to where there was a rough semi-circular wall of rock and stones on the brow of the hill and overlooking the numerous huts of the village. Here a number of natives were sitting, to whom Mr Grey spoke, asking for the Chief. Some went to fetch him, and presently from one of the huts emerged a tall thin bent old man, without a single hair on his scalp, but with a thin grey moustache and beard in a circle round his mouth, and wearing for sole garment an old worn out green greatcoat, with brass buttons, reaching well below his knees. Several of the headmen walked with him and round him, clapping their hands gently together as they approached.

He came up slowly and with as much dignity as his tottering steps would allow, and sat down on a stone seat within the semi-circle. Mr G. Grey told the old Chief what he wanted, adding that I was Mr Selous’ friend. The name had a markedly good effect, and after some palaver among themselves, in which the words Chititeke, Chipadze, Zimbabye, etc. came in, Chipanga told a boy, dressed unlike the others, in European costume, (and who, we afterwards found, had been Lady Henry Paulet’s servant for a time) that he was to be our guide to the ruins. The boy evidently wished to avoid so unpleasant a task, and there was a good deal more talk among the natives, and then a long pause, during which no one uttered a word, and we remained spectators of the scene, wondering what the outcome would be, and whether the Chief would be obeyed. Then Chipanga once more addressed the boy, who replied by getting up and signing to us to follow. This we did for about three-quarters of a mile, surrounded by most of the male population of the kraal, particularly the “piccaninnies” of whom there were any number.

At last we came to a circle of trees at the edge of a still traceable ditch enclosing a mass of large granite boulders mixed up with ruined walls. Here we dismounted, and found that there was a flat space of some twenty yards between the ditch and a further line of bank covered with trees; and again inside that was a wall enclosing the granite boulders. [This is Zvipadze No 2]

This wall was of better workmanship than modern native masonry, but nearly as good as the Zimbabye walls. It had low doorways, with stone lintels, the openings being too small to get through without crouching. As we went around we saw a great many other bits of wall, some better, some worse, some apparently loopholes, and most of them built with mortar, in this respect differing from those at Zimbabye, which are pure dry-stone work.

There also seemed to be the remains of some modern huts mixed up with the older buildings. One circular wall, about the circumference of an ordinary hut, but consisting now of only three or four courses of stone, had holes left at intervals all around it, but whether this was the foundation of a hut, or some more important ancient building, was not easy to determine. We did a number of photographs of the ruins, with and without the natives, who viewed our cameras with scarcely any alarm.

Every available scrap of ground within the fortress was planted with tobacco. Evidently there was no fear in the native mind of anything supernatural here. We now asked where Chipadze’s grave was, and were pointed out a group of rocks and trees between two kopjes a little way off to the north-west. We walked thither, preceded by our guide, but not one of the natives except him would come another step with us. The grass was tremendously luxuriant and long and difficult to get through, being high over our heads, and it was not til we came right up to a wall that we realized its presence. [This is Zvipadze No 1]

The masonry of it is almost as perfect as that at Zimbabwe, but the stones (if my recollections are right) are somewhat larger. As at Zimbabwe they are wedge-shaped and beautifully fitted together in even rows without mortar. The wall is not continuous, but fills up gaps between boulders, and within them encloses a space, which at a guess, Mr Grey puts at thirty to fifty yards. The bits of wall vary in size and what I saw (for I did not go around, owing to the difficulty of getting through the jungle of vegetation) was broken down in places, and nowhere finished at the top, so one could not tell how high it may originally have been. The height where I measured it was about 7′6″ and the thickness about 5′6″. There were four graves within the enclosures, one only by itself and three in a group. All had at one time been covered by huts of upright sticks, but not, as is usual, plastered with clay, and with ordinary thatched roofs. They were all in a more or less ruinous condition, only one having any roof left on. This one was in the group of three, and inside it were three stones arranged in a triangle, and with a large grey pot on them just as natives usually arrange stones to support a pot for cooking. Mr Grey saw nothing else of interest, but the place was so overgrown that it would have been difficult to see anything had it been there.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. A Guide to the Antiquities of Inyanga. Published by the Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments and Relics in 1972. Courtesy of ORAFs.

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin. Cape Town 1971

F.C. Selous. Travel and Adventure in South East Africa. Books of Rhodesia 1972.

P.A. Robins and Anthony Whitty. Excavations at Harleigh Farm, near Rusape, Rhodesia 1958-1962. The South African Archaeological Bulletin Vol 21, No 82 (June 1966) Pages 61-80.

A. Balfour. Twelve Hundred Miles in a Waggon. Edward Arnold. 1895