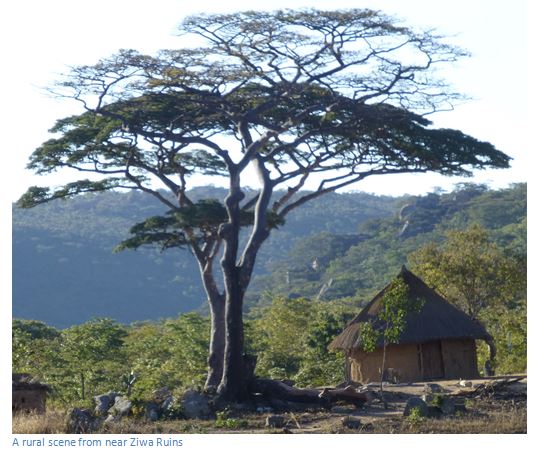

Ziwa Ruins and Site Museum (formerly Van Niekerk Ruins)

- The Stone Age hunter-gatherer communities that lived here from 350,000 to 2,000 years ago were succeeded by herding and farming communities around 200 AD who gradually built the village communities whose remains we see today. They were accomplished potters and skilled at making iron implements using charcoal fuelled furnaces.

- Around 1500 AD these communities were superseded by a new community, called the Nyanga tradition that arrived through the lower Zambezi Valley and may have been of Tonga origin. Their agriculture necessitated terracing the hill slopes and valleys for cultivation and building the stone-lined pit structures which we see today. The extensive areas they cleared and terraced over 8,000 square kilometres may have been the result of their population increasing and the fact that they were prevented from enlarging their land area by stronger groups which surrounded the them.

- The archaeological remains here include: terracing, enclosures including pit enclosures, hill-forts, furnace sites and grinding places.

- The first-rate Ziwa Site Museum is well-designed and provides informative insight and background; the staff are knowledgeable and welcoming.

From Rhodes Nyanga Hotel: Drive 1.6 KM to the main road (A14) turn right and head for Nyanga Town: 4.3 KM continue past the Troutbeck turnoff on your right, 7.4 KM continue past the intersection to Nyanga town, 9.2 KM continue past the Hospital, 11.7 KM tar road changes to untarred road, 14.8 KM turn left at Ziwa Fort and Nyahokwe Village sign, 17.82 KM turn right at sign post, 18.44 KM cross Nyarerwe River Bridge, 21.35 KM turn right at sign post, 25.65 KM keep to road on the right hand side, 27.00 KM Mount Ziwa prominent on the right, 29.42 KM turn right at sign for Ziwa Site Museum, 30.6 KM reach Site Museum. A high clearance vehicle is recommended as the Nyarerwe River Bridge has been washed away and the road detours through the river bed.

GPS reference: 18°08'10.13″S 32°38'15.50″E

On Google Maps from an eye altitude of 1.7KM the enclosure circles and terracing are clearly visible around the Site Museum and stretching to the north.

The Ziwa Ruins (National Monument No. 53), was formerly named van Niekerk Ruins after Major Pompey van Niekerk, who in 1905 guided Dr. Randall-MacIver the first trained archaeologist to inspect them, are only a small portion of land 40 square kilometres in extent in the centre of the ruin area. Even within this area, only a tiny, though representative, portion has been opened up around the Site Museum.

The original farm was owned by Friedriek Bernhard, who developed an interest in the prehistory of this area and in 1946 ceded the farms 3,337 hectares, which include the Ziwa and Nyahokwe sites, to the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe.

Dominated by the 1,744 metre high Ziwa Mountain the Site Museum provides exhibits of pottery, weapons, metal work and beads, and a comprehensive summary, of the many Nyanga cultural phases. The exhibits, all of local origin, range through the Stone Age, the Ziwa culture, the Upper and Lowlands Nyanga cultures themselves to late nineteenth century Shona. There are displays of the crude, chipped stone tools of the "Sangoan period" of the Early Stone Age, followed by the smaller; more varied, and finely made stone weapons and tools of the succeeding Middle and Late Stone Ages.

Late Stone Age San hunter-gatherers left painted rock art sites in the granite shelters in the area.

They were succeeded by early Iron-Age communities who probably crossed the Zambezi about 200 AD. They built the village complexes and kept livestock, probably sheep and goats, but not cattle. Their industries include iron-smelting in furnaces using charcoal and native iron-ore and also pottery, called Ziwa ware which have distinctive comb stamped rims and necks and is generally dated 200 AD to 800 AD.

From 1500 AD to 1800 AD they were succeeded by a Tonga group from the Zambezi Valley, referred to usually as the Nyanga tradition and divided into an earlier Upland Culture embracing Nyanga National Park (called Type 8A by R. Summers) and a later Lowland Culture represented by Mount Ziwa and Nyahokwe (Type 8B) The Nyanga tradition culture built these permanent settlements and terraced the hill slopes for agriculture and built the pit structures to safeguard their livestock. In the seventeenth century, as the Nyanga Uplands became infertile and the climate deteriorated sufficiently to cause crops to fail, people moved westwards and established the Nyanga Lowlands settlements. Here it seems that every stone over hundreds of square kilometre has been moved and used as walling. Though the quality of stone building may be unexceptional, the sheer quantity of labour required is inspirational.

It is often presumed that a huge population must have been involved in the construction of the Lowland terraces and buildings, but Roger Summers thinks this is by no means certain, as without fertilizer the soils quickly lose their fertility and so the farmers would have to move to new land. Under this shifting agriculture Summers thinks the rocky slopes of almost every hill or kopje would have been cleared and encircled by stone built terraces in a comparatively short time.

The four distinct prehistoric Iron Age cultures that have superseded one another within Nyanga each has its own distinctive area which is named after it.

| Ruin type | Period | Examples |

|

|

|

|

1 | Ziwa | 200 to 800 AD | Ziwa and Nyahokwe village |

2 | Zimbabwe | 1600 AD | Zvipadze Ruin (formerly Harleigh farm) |

3 | Nyanga Uplands | 1500 to 1700 AD | Chawomera, Nyangwe, pit structures, water furrows |

4 | Nyanga Lowlands | 1700 to 1800 AD | Ziwa and Nyahokwe (formerly van Niekerk ruins) |

Exotic theories of ancient Semitic origin were proposed by the early explorers Dr. Heinrich Schlichter in 1897 and Dr. Carl Peters in 1900, followed by R. N. Hall, who believed that they were of Arab origin from the eleventh or twelfth centuries. Modern archaeological studies of the beads, pottery, bone and metal work makes it quite clear that none of the ruins have any exotic influence, or of great antiquity.

Vistors should take the guided tour from the Ziwa Site Museum which starts with the nearest enclosure (there are 100+) where the circles of several huts can be traced and their method of construction clearly seen. Flat slabs were set on end in the ground and further slabs laid across them to form a horizontal platform clear of the ground. This was then thickly plastered with daga to form the hut floor. The collapsed remains of several such floors can be seen. Grain stores today are constructed in a similar way and the smaller circles in this enclosure probably served a similar purpose. Examination of the outer enclosure wall shows that it was not a single continuous circle, but built as a series of separate adjoining arcs, often adapted to the curve of a hut. The huts were therefore sometimes built before the wall. These enclosures are not therefore primarily defensive but simply protective shelters from the penetrating winds and rain of the Nyanga winter.

The enclosures housed individual family units with their livestock protected in the central pit structure, its lintelled doorway entrance, some with locking beams, sealed during the hours of darkness, exactly the same principle as the pit structures in the Nyanga Uplands, except that these Lowland pit structures are not set into the side of the hill, but rest on solid rock.

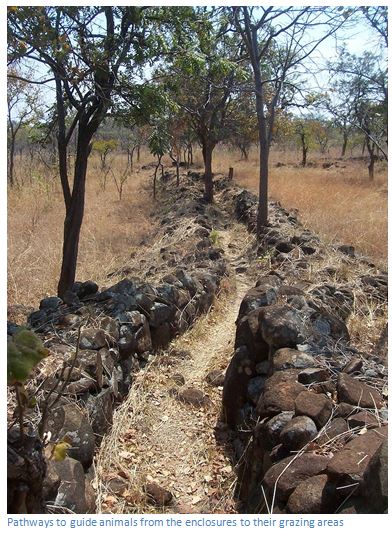

Evidence of grinding places, or quern stones, shows the essentially agricultural nature of these communities, the main purpose of building all these walls was to clear the ground for agriculture, but at the same time they marked out individual family fields and provided walled pathways to protect their crops from animals as they moved from the pit structures to where they grazed in the day. In addition placing stones along the physical contours prevented soil erosion. The walls were constructed by filling the space between two free standing walls with a rubble infill of smaller stones and the builders used large natural boulders in situ to save time and labour.

The photo above shows a large flat stone that is lifted off the ground and was used as a natural rock gong by hammering it with the round stone shown. The archaeological evidence suggests that the community grew from 1700 AD until it increased beyond the land’s carrying capacity and with the soil fertility diminishing the people gradually abandoned the area about 1800 AD.

Summers concludes the buildings here are a later and improved development on those of the Uplands. To give some idea of their scale he states that if the Ziwa to Nyahokwe area is considered as one “unit”, at least fifteen further units have been identified in the area west of Nyanga from aerial photographs.

The Site Museum is an admirable example of what can be achieved through a collaborative effort in 1990 between The National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe who provided the exhibitions and staff and NORAD, the Norwegian Agency for Development who provided the funding. Ziwa is currently under consideration for a UNESCO World Heritage listing.

Visitors are well-advised to take the excellent and informative guided tour for an additional $1 per person. Helpful advice and information from the Curator and staff on site make it a very worthwhile trip.

Acknowledgements

P.S. Garlake. A Guide to the Antiquities of Inyanga. Published by the Commission for the Preservation of Natural and Historical Monuments and Relics in 1972

R. Summers. Ancient Ruins and Vanished Civilisations of Southern Africa. T.V. Bulpin. Cape Town 1971