Pieter Lourens van der Byl’s grave at Mona Farm

Some of the details below are taken from J.W. Bousfield’s lecture to the Mashonaland Branch of the History Society in September 1989. In describing the lecture, Vivienne Sommerville described exploring the delightful old buildings of the Mona Farm homestead in peaceful surrounds and enjoying the unexpected bonus of a scrumptious tea provided by their hosts, Gordon and Caroline Taylor.

What changes the ensuing 26 years have brought! The homestead and garden now neglected and unkempt, the once prosperous farm lying neglected and disused; the former staff now probably jobless and living on food aid and the owners long gone.

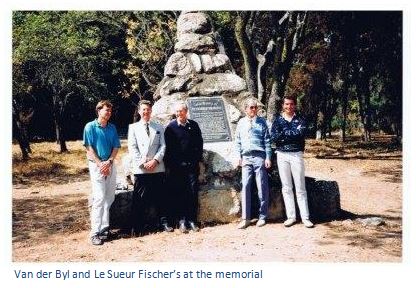

Van der Byl’s grave is reached through an avenue of blue gum trees, each of a different species. The grave is in stone with a plaque inset extolling his virtues and erected in remembrance by his affectionate brother and son.

An early experiment that went wrong; the trekkers were obliged to wait two years before being granted land, and this requirement was soon withdrawn.

From Headlands take the A3 towards Rusape. 10.2 KM pass the Baddeley Road turnoff on the left, 23.8 KM as the A3 takes a right-hand bend and opposite farm buildings, turn right off the tar onto an untarred road going back Headlands way, a group of rondavels are 400 metres ahead on the same side of the road, 24.8 KM cross the railway line and turn right at the road intersection. 26.4 KM turn right into Mona Farm, 26.7 KM reach the farmhouse.

From Rusape directions are from the A3 National road / A14 Nyanga road. Heading north toward Harare, pass a group of rondavels, 10.3 KM turn left onto an untarred road, 11.4 KM cross the railway line and turn right at the road intersection, 13.0 KM turn right into Mona Farm.

NOTE: in July 2016 Mona Farm was involved as part of the internal squabbles of the ruling party succession. The previous occupant, a high ruling party official, had been thrown off this just one of his many jambanja’d farms and someone else was claiming ownership. I met with a group of 20 people who were within the tobacco shed area and claiming ownership; but they were probably just foot soldiers for some party official and seemed to be doing nothing economically useful. Their behaviour was slightly menacing and I would not recommend visiting this site at the current time.

GPS ref for A3 turnoff: 18⁰26′35.49″S 32⁰08′05.54″E

GPS ref for Mona Farm: 18⁰25′17.32″S 32⁰07′38.34″E

The van der Byl trek of 1891 was sponsored as part of the policy to unite Boers and British in the common task of colonising to the north of the Limpopo River, although as John Bousfield says it is difficult to imagine a less well prepared or naïve group, and was in response to an advertisement in the Cape Times in June 1891 seeking: “men of good parentage, a knowledge of riding and shooting and practically acquainted with agriculture.”

Pieter Lourens van der Byl was an MP in the Cape Colony and agreed to lead the trek. The men selected from the Stellenbosch and Eerste River area of the Cape Colony included Pieter Lourens van der Byl, Myburgh, Weir Faure, Jones, H. Burmester, G. Burmester, McEwan, McHugh, Solomon Wagner, Stegman, Moodie, van Niekerk, Brown, Gilbey, Thomson, Voss, Wright, Steenveld, Paul van der Byl, Hugh Williams and William Fischer. Richard Fischer had run away from home aged 19, and was working as an assistant to an auctioneer in Johannesburg and joined the trek there.

Cecil John Rhodes sponsored and financed this agricultural trek; when they reached Mashonaland they were to be settled on 12,000 acres and would be under the control of van der Byl for two years and if they proved themselves they would each be allocated 3,000 acres, be paid 2 shillings a day and fed for 6 months.

They were required to bring: a stretcher bed, blankets, kettle, grid iron, 1 pan, tin mugs, cups, enamel plates, 3 knives, 3 forks, 3 spoons, tobacco, matches, 6 trousers, 2 jackets, 12 shirts, (6 flannel, 6 cotton), 4 pairs of boots, 2 pairs of veldskoens, 2 pairs of garters, 12 socks, 2 felt hats, 1 straw hat, musical, instruments, 2 caps, 3 bars of soap needles, pins, needles, thread, buttons, linen and cloth for patching, vegetable seeds, books, camp chair. Cricket and football were to encouraged and pet dogs allowed.

By the end of June 1891 preparations were complete and the trek party was made up as follows: 1 leader, 23 white men, 4 Cape boys, 6 Africans, 80 Oxen, 5 ox-wagons, 9 Mules and 2 snow white horses, which both died in the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) A brass band and many dignitaries gave them a great send off from Cape Town on the first leg of their journey by train to Vryburg.

Hugh Williams account, re-written from his diaries by Rob Burrett, gives the fullest details of the journey: “Everyone is healthy, but the Chief is more patriarchal than ever. His men are in high spirits. No body of men within recent years have received such a cordial send-off from Cape Town as we did in June as we left the Cape of Good Hope for the land of Better Hope!”

They travelled by ox- wagon via Johannesburg and then through Bechuanaland, where they lost a cricket match to the Bechuanaland Border police, the journey being described by Williams as uneventful and boring: “we sleep in the wagon, walk with the wagon, think with the wagon and the echo of its rumbling wheels is ever in our ears.” They crossed a very full and muddy Limpopo River in full flood and arrived at Fort Tuli in August and Williams said: “Fort Tuli is on the threshold whence we see the promised land of the rising sun. The camp is rather barren and stony, provisions are scarce and expensive.”

After crossing the Runde and Tokwe Rivers, they arrived at Fort Victoria (now Masvingo) on 15th October which Williams described as: “a country of swamps and fever. There is a small store, but you can get nothing you want – no sugar, salt, or meal. They are all on their way and can be expected any day! But beer you can have aplenty and the quantities consumed on the premises would astonish many a drinker of stronger drink.” They played games of cricket at every BSA police outpost that had sufficient members for a team, but it appears without winning any games!

They initially settled at Inyatsitzi, north of Fort Victoria, but were quickly moved on by Jameson to the Headlands / Rusape area, where the BSA wished them to be a stabilizing factor near the kraal of Chief Chingaira Makoni. Little is known about the trek from Fort Victoria to Fort Charter other than they must have travelled down the old Selous Road through Marandellas and Macheke to Headlands and then on to Mona Farm where they arrived on the 11th November 1891 and set up their settlement on the banks of the Matinidza, a tributary of the Chimbe River.

They named the area Laurencedale, an Anglicisation of Pieter Lourens van der Byl middle name and awaited Rhodes arrival for authority to settle the area claiming they would “build a formidable community, with a church, local board and brass band.” With Rhodes’ arrival they: “hoisted the Union Jack and waited. At 3 o’clock a Cape cart drawn by mules arrived on the horizon. On the front were two drivers and on the back seat were the Prime Minister and his brave supporter Mr de Waal. As they jogged along they looked more like two jolly farmers than heads of Government.”

De Vaal in his book With Rhodes in Mashonaland barely mentions the meeting, merely writing: “it was in the district in which this kraal (Marandella’s) stands that Mr Lourens van der Byl with twenty-five young Cape Colonists shortly afterwards settled, naming the place Laurensdale.” De Vaal must have known Pieter Lourens van der Byl as they had both been MP’s in the Cape Parliament, instead he devotes almost a page to how they struggled to fit a wheel to their ox-wagon without a jack and then how Frank Johnson challenged him to dive to the bottom of a pool for a sovereign, but never paid his bet when de Vaal won!

Thirty three huts were built at Laurensdale, but there was a shortage of tools and seed, no livestock and very little in the way of cohesion within the community. Malaria and blackwater fever took their toll and within five months disaster struck in March 1892 when van der Byl became ill and then died, aged 61 years.

As the funeral cortège was approaching the grave, a tremendous lightning bolt followed a clap of thunder caused the pall bearers to drop his coffin. In 1899 after the 1896-7 Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga, a substantial monument was erected at van der Byl’s grave with the following memorial plaque:

“To the memory of Pieter Lourens van der Byl formerly of WELMOED, EERSTE RIVIER, CAPE COLONY. Born 18 April 1831. Died 30 March 1892.

He was a warm friend, a trusted companion and the most unselfish of men ever ready to devote his time and trouble to the services of others. A true South African and firmly attached to all the traditions of the race from which he sprang. He was at the same time a British Citizen in the largest and best sense of the word and devoted the last years of his life to the task of extending by peaceful settlement the boundary of civilization in that South Africa which he loved so well.

Erected in affection and remembrance by his brother Adrian and son Gerard.”

Leaderless and suffering from disease, the impetus was lost and most of the initial members of the trek dispersed. The van der Byl trekkers seemed to have dispersed for three reasons:

1. Loss of their leader and the serious malaria in the area.

2. Rhodes and Jameson were concerned at the cost of the whole enterprise and ordered an inquiry which found; “not more than three out of the twenty do any work at all and ordered those who had not moved away to divide up the wagons and farming equipment and take up farming on their own account.”

3. Later settlers were granted 3,000 acres on arrival and did not have to wait the two year period.

An area of land between the Macheke river and the Chimbe river, either side of the old Selous Road was pegged by the Survey Dept., (plan DG630) and called the Laurencedale Block, including a special block for Lourens van der Byl, which he called Helenvale Estate, bounding the Macheke River end, and a further grant for Settlement which became Mona Farm in 1894.

In-between were 26 farms, numbered but not named. Willoughby’s Mining and Ranching Co. acquired these farms in 1901. They made no use of the Laurencedale block which they sold off and it is recorded that H.C. Fischer bought No. 1 for £1,526 and No. 2 for £1,231, while W.F. Fischer bought No. 5 for £2,563 in 1952.

The Fischer brothers took up land on Fischer’s Farm about 20 kilometres west of Laurencedale paying a quitrent of£6 4s per annum. They survived the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga of 1896, although Richard had to run from his farm to the adjoining Eden Dale / Headlands Farm, the site of the Headlands laager, which was south of the present day Headlands. Richard finally left Fischer’s Farm because of malaria and was granted Coldstream Farm, west of and adjoining Headlands, by the B.S.A. Company in 1911. After the rebellion, William moved to Nedziwa, which appears to have been in the Chimanimani area.

Wakefield Farm south west of Fischer’s Farm was acquired in 1916 for two blankets and a bottle of whisky. The Fischer brothers, Rijk and Chris, started farming here in 1922.

The above farms are all marked on the 1:250,000 map.

Hugh Williams stayed and established a postal agency in 1896 on Mona Farm, although the building no longer remains. His letters and diary preserved in the National Archives are the most valuable source of information about the settlement and were transcribed by Rob Burrett.

Rob Burrett in a Heritage article, The Selous Road, Ballyhooley Hotel, and the Ruwa and Goromonzi Districts describes why Laurencedale became important. The rainy season after the Pioneer Column arrived in September 1890 was a particularly heavy one and all the major rivers including the Umzingwane, Nuanetsi, Runde and Tokwe became impassable to crossing by ox-wagons for months on end. The best route appeared to be to Beira through Portuguese East Africa.

The initial route from Salisbury to old Umtali was made by the BSA Police through the important Shona Chiefdoms including Chikwakwa (near Goromonzi) Mangwende (Tsindi ruins north east of Marondera) Makoni (north east of Rusape) to the Penhalonga valley and then onto Massi Kessi (Macequece and now Manica)

However this route meandered along native footpaths and did not follow the watershed which was easier for ox-wagons and carts and in 1891 F.C. Selous was given the task of finding a more direct and easier route by the BSA Company. The result became known as the Selous Road and followed the main watershed lessening the number of rivers that needed to be crossed at drifts and avoiding marshy areas. This became the main route until the railway linked New Umtali (now Mutare) and Salisbury (now Harare) in late 1899.

The first official transport contractor was the Salisbury Transport Company which used ox-drawn Cape carts, but many private transport contractors began to also use the route and the three main stops for changing the ox spans became Ruzawi Drift (Old Marandellas) Laurencedale and Odzi Drift. Mules soon replaced oxen and the Zeederberg Coaches provided a much faster service, but required more frequent changes than oxen. Rob Burrett’s interesting article is recommended as further reading on this subject.

Harry Craufuird Thompson was in Manicaland just after Old Umtali had been abandoned for new Umtali in October 1897 and wrote his book Rhodesia and its Government. He walked from Old Mutare with one of the Fischer brothers and nine native carriers, he doesn’t say if it was Richard or William, staying the first night with Mr Caulfield, the Clergyman in Church House as the hotel was full. The next day they left late in the afternoon following the Nyanga road to the Odzani River, where they had supper, before taking a native path and walking in the moonlight to the Odzi River. Fischer told him that the lions had become so ravenous on account of the rinderpest killing all the game that a horse had been killed a day or two before by lions on the main road…this news made him nervous and jumpy at every rustle in the grass.

They waded through the Odzi River, and camped on the other side, making a roaring fire to keep the lions away and sleeping in blankets with a rifle between them. They met old Chief Rukui at his kraal, Thompson noting how the people clapped their hands in respect to the Chief and shared some beer with the Chief in a gourd calabash. After walking all day they camped near Chief Chaganguru, who walked across to meet them and where they bartered oofoo, a ground meal made from rapoko, the staple grain of the Mashona for three pence worth of salt. Thompson says the same amount of oofoo in Umtali would have cost two shillings.

That night they camped by a mountain stream, at a place called Nia Tandi, (possibly the Nyamatanda River?) building a scherm, or barrier of thorn branches to keep out lions. They left before sunrise and after a mile climbing up a steep granite rise (the Shena Hills in the south of the Makoni Communal Lands?) where he says they could see Chief Chingaira Makoni’s demolished kraal in the distance and the Devil’s Pass through which the Salisbury road ran. They reached the Fischer Farm in time for breakfast and had a warm welcome from Fischer’s brother who had been down with an attack of malaria.

During the Mashona Rebellion the Fischer brothers had gone into the laager at Old Mutare, but quickly returned to their farm despite being warned against it, as they felt they were on good terms with their staff. However they did not return to their previous homestead, but built a fort between two huge boulders which they felt they could defend against any attack. Their fort had clay mud between the thatch and the rafters to make it fire-proof and their room was on top of a boulder reached only by ladder which they drew up after them. The main disadvantage of the site was that the nearest spring for water was 800 metres away.

Thompson says the nearest police station was nearly 25 kilometres away and it was men like these that Rhodes wanted as settlers. Thompson describes them as Americans, although actually they are from the Cape, and says they were doing well on the farm. In 1896 they grew oats which were sold as horse fodder to the troops and now they were growing maize and tobacco. He tried their tobacco, but found it too strong. They had experimented with the castor oil plant, tomatoes and granadillas, but found vegetables were all eaten by the insects.

The Fischer brothers told Thompson that farming did not really make a profit; they did better trading with the local Africans and buying maize and oofoo to sell in Old Umtali. There had been locust swarms and the rinderpest, which had killed the cattle, made farming difficult. Thompson believed the country was well suited to cattle as before the rinderpest there had been over half a million of them. Although not critical of the Fischer’s, he was critical of most farmers, who he says are not farmers at all, they are simply men who have taken to farming and expect with little or no knowledge to make sufficient profits in a few years to enable them to go back to England!

He described the Fischer’s farm as being on a well-watered plain, over 1,500 meters high and not particularly well suited for agriculture, but good for cattle. He says in Old Mutare he had met Mr Fotheringham [see the “Rhodes Nyanga Estate” article on the website www.zimfieldguide.com] who had just sold his Nyanga farms to Rhodes and was on his way back to Australia having been well paid for them. Fotheringham seemed pleased to be leaving as conditions were very hard and says he met very few who wanted to stay permanently; almost everyone was anxious to make a little money and clear out!

In the kopje behind the Fischer’s original homestead was a stone-walled and fortified kraal. The walls ran between massive boulders with the stones in fitting closely without mortar. The Chief’s hut was on top of a rock only reached by ladder.

A few kilometres away on the road to Nyanga is the kraal belonging to a locally famous witch doctor (now called tribal healers) called Chirimba. Chirimba told Thompson that he had heard that there was a white-man in the country who had no hair on his face, so he presumed he was a white witch-doctor!

A shortage of labour meant there was nobody to carry Thompson’s luggage and he walked to Le Sapi (Rusape?) store to see if he could obtain carriers. The store-keeper there lent him one carrier and told him to call at the farm of Frank Xigubu, the Zulu brought into Mashonaland by Bishop Knight-Bruce. From there he walked onto Chief Chingaira Makoni’s and came across an African carrying a rifle, now strictly forbidden with the Mashona Rebellion, or First Chimurenga recently over. The man explained that the Native Commissioner had given him permission to carry a rifle for protection as Makoni’s son was keen to take revenge on those that had sided with the Europeans.

Acknowledgements

J.W. Bousfield. Heritage Journal No.10 1991. Pages 102-104

Hugh Williams’ Diaries in the National Archives were transcribed by Rob Burrett

Peter Fischer who let me use his photographs and the article on his website: www.fischweb.net/trek.htm

R.S. Burrett. The Selous Road, Ballyhooley Hotel, and the Ruwa and Goromonzi District. Heritage of Zimbabwe No. 17, 1998. Pages 108 - 120

S.P. Olivier. Many Treks made Rhodesia. H.B. Timmins 1957.

H. C. Thomson, Rhodesia and Its Government. Smith, Elder & Co. 1898

D.C. de Vaal. With Rhodes in Mashonaland. Books of Rhodesia No. 36, Bulawayo 1974