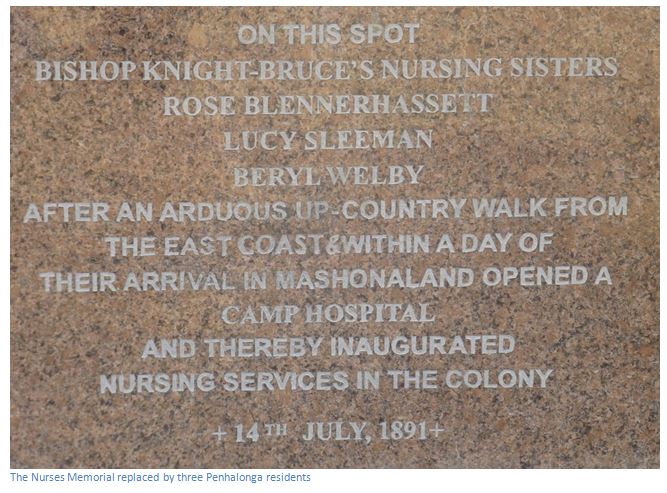

Nurses Memorial

Louis Bolze, the Publisher of the Books of Rhodesia facsimile edition of the book Adventures in Mashonaland says in his introduction: "Manicaland was very much an untamed country…in embarking on this hazardous undertaking these three young ladies could have had no motive other than the highest ideals of service. Having promised Bishop Knight-Bruce their assistance in setting up a mission hospital in Mashonaland – two of them without financial recompense – neither fever swamps, wild animals and rugged terrain, nor yet the Charter Company’s reluctance to admit women into a yet unsettled Mashonaland, deflected them from their purpose."

A Pioneer Nurses Memorial Garden or Garden of Remembrance was created on Sabi Ophir Hill at Penhalonga centred around a memorial seat and bronze plaque erected under a great fig tree (no longer there) known as the Indaba Tree at the place where the three nurses began their hospital in 1891. The seat was erected in 1941 by the Rezende Mine to mark the 50th anniversary of the nurses’ journey from Beira.

From Harare pass the A15 turn-off from the A3 main Harare to Mutare Road, 2.4 KM turn left before Christmas Pass at the petrol station on road signposted for Penhalonga, 7.2 KM continue past the Fairbridge Road going to the left, 8.1 KM turn right onto a gravel road going between residential homes, 8.2 KM bear right following the gravel road up the hill, 8.7 KM stay on the main gravel road ignoring side roads; pass along avenue of Jacaranda trees, 8.85 KM the road bends to the left following the contours of the hill 8.9 KM arrive at Nurses Memorial car park.

GPS reference: 18⁰53′12.15″S 32⁰39′32.63″E

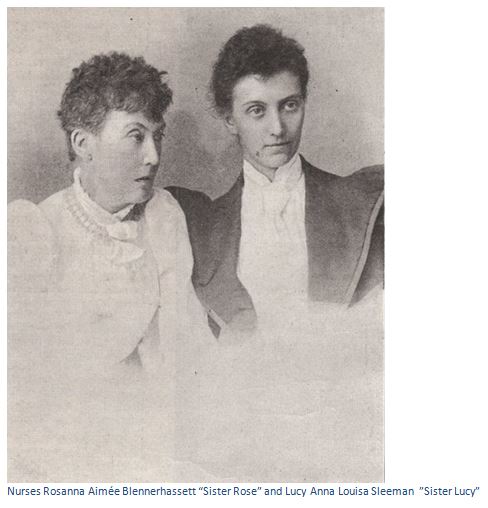

What follows is a shortened description of the journey from Beira to Penhalonga in 1891 by Rosanna “Rose” Aimée Blennerhassett (1843-1907) “Sister Aimée” Lucy Anna Louisa Sleeman (1865-1907) “Sister Lucy” and Bertha Anne Welby (1861-1941) “Sister Beryl” who were the first three trained nurses in Zimbabwe.

16th April 1891 Beryl Welby, Lucy Sleeman, and Rose Blennerhasset leave Cape Town in the Roslyn Castle for the Pungwe River and Mashonaland to begin nursing services there at the request of Bishop Knight-Bruce.

22nd April reach Durban. The Bishop says travel via the Pungwe River is impossible, but then he meets a man just returned who has taken 4 months by road due to the worst rainy season in years. They meet Frank Johnson who tells them they will have to spend 10 days on the Pungwe River in an open lighter, crowded with white men and natives; that there is no accommodation for women and the swampy nature of the river banks made it impossible to pitch a tent.

18th May leave Durban in the Tyrian, crowded with men, some going up as traders, all more or less as prospectors hoping to strike it rich.

23rd May reach Inhambane where the natives have never seen European women before. They are followed by forty or fifty wherever they went, evidently criticising freely – and probably, not always favourably!

26th May reached Beira, a long flat reach of sand with a few tents and two iron shanties and that’s all. As there is no transport to Umtali, or accommodation in Beira, the three nursing sisters stay on the Tyrian as it slowly steams to Mozambique island, then Quilimane and then returns.

13th June disembark onto the Shark, a small steam-launch, get lost in a fog before getting stuck on a sand-bank and then getting under way up the Pungwe River. Our first sight of hippopotamus and we are relieved to see they do not crunch up boats for amusement! Filled with horror by the monstrous crocodiles, the Pungwe River literally swarms with them and “out of such evil, glittering eyes might lost spirits and condemned souls look forth.” At Nevez Fereira, a Portuguese encampment where the soldiers beat their drums and level their rifles at us, we are obliged to stop and explain ourselves.

14th June reach Mpanda's. It would be difficult to give an idea of the dirt and squalor of this place. The camp is pitched on a mud bank between the Pungwe River and a stagnant creek. We got the tent the Bishop had left ready for us; it had been used meanwhile for some sick men, but another hut was run up for them. Dr. Todd asked us this morning to help with the sick, of whom he has taken charge, Dr. Wilson, the Company's doctor, being seriously ill with fever. Yesterday morning two natives were found dead. We found twenty-eight in two very dirty miserable sheds. All were very ill, some in great danger. We began to clean out the sheds ourselves, when a European sent two of his natives to do it. We fed the native patients every three hours to-day, and I hope we shall lose none. Dr. Todd's kindness to the natives is delightful to see.

June 15th couldn't sleep last night because of the lions roaring about half a mile from camp, where they were devouring a bullock. The rats were troublesome, they are enormous and run over us at night, often dropping on our heads from the roof of the tent; but they are not as fierce as English rats, their snouts are less sharp, they are more like gigantic field-mice. We went to-day to see the so-called road, which is merely a rude track along which the grass has been burnt. A runner brought letters from the Bishop, who gave advice for getting carriers to carry us up in 'machilas,' in the Portuguese fashion. It is, we are told, a walk of 225 kilometres (140 miles) we are anxious to get on.

June 29th, most of the Europeans at 'Mpanda's have the fever. Some working-men spent everything at Mpanda's, unable to get on, and at last turned back with no money and with shattered health. Mpanda's is crammed with stores of all kinds; the owners of them can't get on. To-day the Bishop's man, Wilkins, came back from a kraal about fifty miles away, and brought us twenty-eight natives, sixteen able-bodied and seven almost children. We have given up all idea of 'machilas,' as we want to try and take provisions up, and each 'machila' requires four natives. We hope to be ready to leave to-morrow. There is no change in the camp, and it is very difficult to get money to pay the natives. They only understand two coins--a rupee and 'umpoundo,' which is £1. They would rather have a rupee, value 1 shilling 8 pence, than 5 shillings.

1st July, we are away from Mpanda's at last! We planned to encamp last night about four miles from Mpanda's, and begin our walk in earnest to-day. Our departure was delayed in many ways, the natives being very tiresome, rushing back to the canteen to drink, refusing to start, so that it was getting dark as we filed after the long line of carriers down to a point where we were to cross the Pungwe River. One little canoe, dug out of a tree, was there to meet us, and a strange little shrivelled old man paddled us over. We sat on the edges of the canoe, there being no seats, or sticks across, and the boat was too narrow to admit of our sitting at the bottom of it. We were in mortal terror, afraid to breathe, for a sudden movement would easily upset such a canoe, and the river, as we know, swarms with crocodiles. It was a great relief to be on terra firma again, and to watch the natives and the loads coming over. We had now arrived at the kraal where we were to spend the night. It was already dark, and we proceeded to hunt up the bundle containing candles, and lanterns, but it was not to be found. To our horror we discovered that the boy who carried this special load had not come on; he had got tipsy, and remained “somewhere.” There was hardly any wood to be had, but we made as good a fire as we could, and took the difficulties gaily. It was hopeless to try and pitch a tent in such darkness and confusion, so we rolled ourselves in our blankets and slept by the camp fire. We could hear lions roaring in the distance, and the weird cry of the hyena.

2nd July walking on narrow paths and exchanging beads for large pots of native beer for their carriers at each kraal, where inevitably the whole population turns out to see their first white women. The inhabitants prefer beads, or limbo to money. We cross the Pungwe River again, each on the shoulders of two carriers, the others shouting and beating the water to frighten away the crocodiles. The walk was very trying; there was no water for nearly twelve miles; the soil was loose, sandy, and for every step forward we seemed to slide two back. Late in the afternoon we reached a shelter built of grass, where we decided on spending the night. During the night the lions came down to drink at the swampy pool in front of the shelter, and they made a terrific noise. The earth seems to shake with their roaring and we do not even have the slenderest door, or mat, to shut them out of their hut.

3rd July we arrived in Sarmento, to-day. We are now forty-five miles from Mpanda’s. To-day's walk was uneventful. The path crossed a green park-like country, with good-sized trees dotted about, and clumps of palm trees. We saw an immense quantity of game, antelopes, and buffaloes. The natives became much excited; they flung down their loads and rushed after the buffaloes with their assegais. They killed one, and then followed us into Sarmento with huge lumps of gory flesh bound on their loads, and covered with blood. Sarmento is beautifully situated on a sort of plateau terrace, with the river dashing over rocks below, and woods all round. But the village is dirty beyond belief.

7th July in the woods, rain pouring, and great trouble with our carriers. At the first halt, a few hours from Sarmento, they refused to go any further. The 'Inkoos,' or chief, a very picturesque person, with his wool plaited into at least a hundred little tails, went off and hid in the woods. Towards evening he returned, and asked for blankets for all his men, pointing to ours, as if inclined to take them. Dr. Glanville sent him away, and he and his men retired in great ill-humour. The next morning after long persuasion, they were induced to take it up again and go on with us on condition of receiving extra blankets at Massi-Kessi. The next two days are wet and miserable, hours of walking through grass ten feet high. Hyenas made the nights hideous, their shriek more like the wail of a lost soul than a mere earthly sound.

10th July had breakfast at Mandingo’s, a deserted Portuguese camp. Natives poured in from neighbouring kraals. The women made us presents of meal. Wherever we go the natives display great curiosity about us, watching us whilst we eat, and often following us to some distance. We met a native with letters, and found one for us from the Bishop, who supposes us to be at Mpanda's. Finally arrive at Chimoio, a large kraal and Portuguese station.

11th July awake to find all our carriers, except four Portuguese natives, fled in the night. It was wet and dismal, and at first we were almost in despair; seventy miles from Umtali, surrounded by our stores and no means of taking them with us! But after a short discussion, we three decided on pushing on with Dr. Glanville and three natives. We took only a change of things with us, the smallest possible amount of food, and we left most of our blankets behind. Our few men went splendidly, and we got over the ground very well indeed. We met a camp of white men going the same way that all turned out to stare at us, saying it was wonderful we had got so far, but shaking their heads at our idea of reaching Umtali. We continued on, getting through difficult swamps, sometimes sinking above our waists in mud, but got through safely.

12th July we reach Massi-Kessi, a red earth fort, standing on a small hill, but with the walls battered down and a large V.R. over the entrance. The Commandant of the fort was extremely civil, considering the treatment he had received and sent one of his messengers to Umtali (i.e. Fort hill) eighteen miles away to warn the Bishop of our arrival.

14th July, at last, Umtali! Yesterday was a day of misfortune, for on leaving Massi-Kessi, we found that the boys had lost their way, and were not even sure of the direction of Umtali. When we halted, they went to explore the neighbourhood; but we must have gone far out of our way, for we walked rapidly since 6.30am, halting only once for half an hour, and we did not reach this place till 5pm. We climbed bare slippery hillsides; the heat was intense, and we could find no water till late in the afternoon. We had nothing to eat, the provisions having come to an end the day before. However, we had a small quantity of Bovril, which we drank when we found a stream. We almost despaired of reaching Umtali, and it was with a feeling of intense relief that we suddenly saw the police flag afar off. The Bishop met us at a river below his camp; he had only got our letter an hour or two before we arrived. He gave us up his hut and made us as comfortable as possible. I feel very ill and fear I have got the fever.

August 15th 1891, we have now been at Umtali a month, and are still at Sabi Ophir camp, the guests of Mr. Campion. The Bishop has gone to his Mission farm, a place about three miles from here, very picturesquely situated. The Mission-house will be on the top of a craggy mount commanding a beautiful view of the valley. I have had a rather bad attack of fever; Sister Beryl a slight one; and the Bishop has had some very sharp ones. The Company are building our hospital huts about half a mile from the camp; the doctor's house is alone on a bare hillside. We are still without luggage of any kind, excepting what we brought up with us, merely a change each. A man, who contracts to manage transport, took our things and most of the Bishop's stores away from Mpanda's on the 6th of July, with waggons and eighty oxen. We hear that all the oxen are dead and the waggons stuck on the road.

24th August, today we heard with surprise and regret of the death of Dr. Glanville. He was apparently a very strong, healthy man, but towards the end of our walk up from Chimoio appeared to suffer from exhaustion and would not take any medicine. He left Umtali for Fort Salisbury, and died by the roadside a few miles from his destination. The erratic post arrived to-day with the first English letters we have had since we left Natal. They were dated May 1891. The mail-bags come in different ways. Sometimes they dangle from a native's assegai, sometimes they go by waggon at the rate of a very few miles a day, sometimes they tear down by runners. You may get a letter dated July before you receive one dated May.

26th September their first patient is admitted.

25th October, we walked over to the new township, which is rushing on (i.e. Fort Hill) The temporary hospital is up; we are to have five huts with a covered way between, and a kitchen with two pantry places. Then there is to be another covered way to the two hospital wards, one for civilians, holding fifteen beds, and one for the police, holding five beds; close to these is the dispensary.

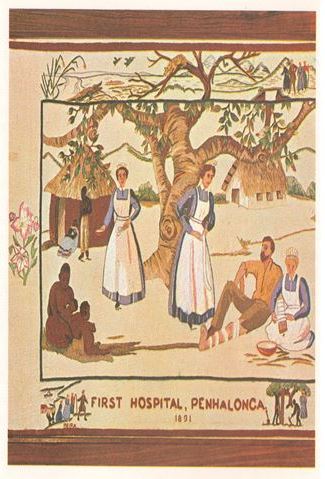

The panel from the National Tapestry, embroided by the Penhalonga Women's Institute celebrating the First Hospital, Penhalonga in 1891. The top border portrays the nurses crossing the swamps of the Pungwe River on the journey from Beira.

As Oliver Ransford says in the text there is scarcely an account of the early days of Umtali (now Mutare) which does not pay tribute to the three nursing sisters who tended to the sick, mainly from malaria fever, from July 1891 to May 1893. Although their account above descibes the hospital buildings, it does not say the furnishings consisted of two or three iron spoons, two tin mugs, a few jars of meat extract and a packet of maize flour.

The local police force of about 200 men gave the sisters a table, chairs, candlesticks and a bath and some rough pallet beds were constructed. Their first patient was admitted on 26th September 1891; two weeks later Cecil Rhodes visited the hospital and at once wrote out a cheque for £200 to buy medical comforts.

A new hospital capable of holding 30 patients was made in December 1891 and their the sisters worked until the end of their two-year appointment in May 1893.

The original plaque was dedicated in 1941 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the nurses' arrival and the memorial garden was planted.

In 2014 when we visited the monument there was no signage and nobody at the Police Station, or at the Post Office, seemed to know anything about the site of the Nurses Memorial. Earlier the same year, three Penhalonga residents replaced the marble plaque that had been smashed in the chaos that followed the land invasions of 2000 with the one you see today to ensure that the site should not lose its historical relevance.

Acknowledgements

R. Blennerhassett and L. Sleeman. Adventures in Mashonaland. Rhodesiana Reprint library Volume 8. 1969

O. Ransford. Rhodesian Tapestry, A History of Needlework. Books of Rhodesia. 1971.